1. Introduction

The quest to unify the fundamental forces of nature represents one of the most enduring challenges in modern physics. Among these forces, gravity and electromagnetism (EM) govern the structure and behavior of the universe across its vastest scales—from the dynamics of galaxies to the binding of atoms. Despite operating in profoundly different regimes, Newton’s law of universal gravitation and Coulomb’s law of electrostatics share a striking and fundamental similarity: both are inverse-square laws, where the force between two bodies diminishes proportionally to the square of the distance between them [

1,

2]. This structural parallel has long intrigued physicists, fueling speculation that these forces may be interconnected or manifestations of a deeper, unified principle [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Newton’s law describes the attractive force between two masses and is indispensable for understanding cosmic phenomena—galaxy formation, planetary orbits, and the large-scale structure of the universe. Yet, at atomic and subatomic scales, its influence becomes negligible. For elementary particles like electrons and protons, gravity is overwhelmingly overpowered by the electromagnetic force [

7]. In contrast, Coulomb’s law governs the force between electric charges, which can be either attractive or repulsive. This force is the cornerstone of atomic structure, chemical bonding, and all electromagnetic phenomena, dominating the microscopic world. The profound disconnect between these two theories—a classical, geometric description of gravity and a quantum field theory of electromagnetism—lies at the heart of theoretical physics [

8,

9,

10]. The Standard Model successfully unifies the electromagnetic force with the strong and weak nuclear forces, but incorporating gravity remains its greatest failure. This challenge has spurred extensive efforts towards a theory of quantum gravity. Within this endeavor, a pivotal question emerges: could the clear mathematical similarity between Newton’s and Coulomb’s laws point to a hidden symmetry or a common origin? Newton described force in terms of mass, while Coulomb expressed it in terms of charge. Could these seemingly distinct properties be two facets of a more fundamental concept?

In this paper, we propose that Newton’s gravitational force and Coulomb’s electrostatic force are expressions of a single underlying interaction, applied to different properties—mass and charge, respectively. We argue that the key to this unification lies in the Planck scale, the regime where the strengths of all fundamental forces are theorized to converge. In

Section 2, we dissect the mathematical similarity between the two force laws and demonstrate that Coulomb’s constant (

Ke) can be elegantly expressed in Planck units, revealing a numerator identical to that of the gravitational constant (

G)—namely, ℏ

c (

mplpc2). This suggests a common architectural foundation. Building on this,

Section 3 derives a unified electro-gravity equation. This derivation not only combines both forces into a single framework but also introduces key dimensionless parameters: the electron-gravitational coupling constant (

αGe) and the proton-gravitational coupling constant (

αGp). These constants arise naturally from the framework and precisely quantify the notorious weakness of gravity compared to electromagnetism.

Section 4 explores the broader implications of this Planck-scale symmetry for understanding fundamental forces, its potential to bridge classical and quantum descriptions, and outlines pathways for future experimental validation. Finally,

Section 5 concludes by synthesizing our findings and considering their significance for the overarching quest to unify the fundamental forces. This work moves beyond mere dimensional analysis to reveal a latent scaling symmetry in nature, offering a minimalist and testable pathway toward unification that requires no new dimensions or particles, only a reinterpretation of the constants that already define our universe.

2. The Similarity Between Coulomb’s and Newton’s Equations

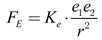

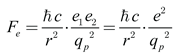

Coulomb’s law is a fundamental electrostatic principle that describes the force between charged particles. It lays the foundation for understanding interactions between attractive or repulsive charges. This law is crucial not only for classical physics but also in fields such as electromagnetism, chemistry, and materials science. Coulomb’s law expresses the force

FE between two electrons

e1 and

e2 as [

11,

12]:

where

Ke is Coulomb’s constant, approximately 8.99×10

9 N⋅m

2/C, and

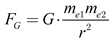

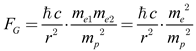

r is the distance between electrons in meters. Interestingly, it is similar to Newton’s law of gravity [

13]:

where

FG is the magnitude of Newton’s gravitational force,

G is the gravitational constant, approximately 6.674×10

−11 m

3/kg⋅s

2,

me1, and

me2 are the masses of an electron

e1 and

e2 in kilograms with values 9.1×10

−31 kg and 1.602×10

−19 C, respectively. Comparing equations (1) and (2) reveals a similar pattern and the inverse-square relationship. From (1), we can find that Coulomb’s constant

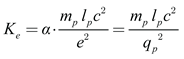

Ke is given by [

14]

where

me =

me1 =

me2,

e =

e1 =

e2, and

re represents classical radius of electron valued at 2.82×10

−15 meters. Upon revisiting equations (3), we find that

mere =

α⋅

mplp [

15]. Hence, we can show Coulomb’s constant in terms of

where

mp and

lp represent Planck’s mass and length, with values 2.176×10

−8 kg and 1.616×10

−35 meters, respectively.

α is the fine-structure constant and

qp is Planck’s charge, with values 0.00729 and 1.875×10

−18 C, respectively. Substituting these values into equation (4.1) yields 8.99×10

9 N⋅m

2/C

2, matching the empirical value of 1/4π

ε0, where the permittivity of free space (

ε0) is valued at 8.85×10

−12 C

2/N⋅m

2.

It should be emphasized that this derivation relies on arguments based on electron rest mass and classical radius. While it does not replace the rigorous QED treatment of Coulomb’s law, its value lies in revealing a hidden Planck-unit structure. The equivalence between Coulomb’s constant expressed in electron terms and its Planck-based representation highlights a structural correspondence that is not apparent in conventional formulations.

3. The Unified Electro-Gravity Force

In this section, we derive a unified equation that integrates Newtonian gravity and Coulomb forces into a single framework, referred to as the unified electro-gravity model [

16,

17,

18,

19]. This model unifies two seemingly distinct forces—gravitational and electrostatic—into a cohesive theory, providing deeper insights into their interplay. This integration is crucial for describing interactions at both microscopic and cosmic scales. Disparities in force magnitudes highlight the importance of key coupling constants, such as the electron-gravitational coupling constant.

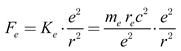

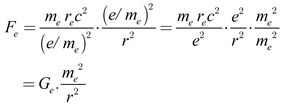

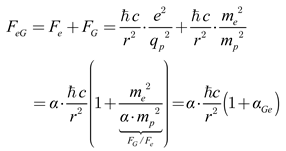

We begin with equations (1) and (3), carefully analyzing them to reformulate the repulsive force. This force can be expressed as an interaction between the masses of electrons, as shown:

From equation (5), it can be rearranged in terms of the charge-to-mass ratio (

e/

me) of an electron expressed as:

Here,

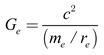

Ge is the effective gravitational coupling, representing the coefficient of the gravitational force between electron masses. It is determined using:

By substituting the electron’s mass and radius into equation (7), we find that

Ge = 2.789×10

32 m

3/kg⋅s

2. Notably, equation (6) has a form strikingly similar to Newton’s gravitational equation, as shown in equation (2). However, the coefficients of the gravitational force differ. Upon careful consideration of equations (5) and (6), we find that both equations yield the same value, which can be compared as follows:

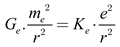

Using equations (8) and (2), we then combine the Coulomb attraction and the Newtonian gravitational force acting on electrons to derive the electro-gravity force (

FeG), expressed as:

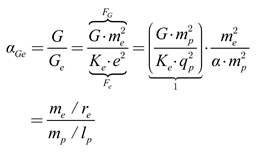

Here,

αGe represents the electron–gravitational coupling constant, defined as the ratio

G/Ge. This dimensionless constant has a value of 2.4×10

−43, which corresponds to the ratio of the gravitational force to the electrostatic force between electrons [

20], expressed as:

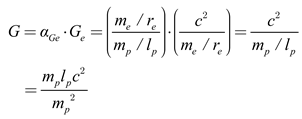

By carefully considering equations (7) and (10), we can demonstrate that the universal gravitational constant is related as expressed in the following equation:

This equation indicates that gravitational interaction propagates at the speed of light, consistent with the prediction of the general theory of relativity. In 2015, the existence of gravitational waves was first confirmed through the groundbreaking detection by LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) [

21].

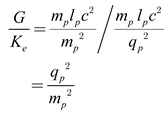

Upon closer inspection of equations (4.1) and (11), we can show that the coupling ratio of the gravitational constant to Coulomb’s constant can therefore be expressed as

From equation (12), we observe that both the gravitational constant G and Coulomb’s constant Ke share an identical numerator, differing only in the denominator. Specifically, gravitational interaction may be expressed in terms of the ratio of the product of mass to the squared Planck mass. In contrast, electrostatic interaction emerges as the ratio of the product of charge to the squared Planck charge.

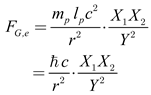

Upon detailed consideration, a unified formulation for the Newtonian and Coulomb forces can be presented as follows:

Here ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, defined as h/2π, and h is Planck’s constant (≈ 6.626×10−34 J⋅s). X1,2 denotes either mass or charge, while Y denotes the corresponding Planck unit (mass or charge). From equation (13), it follows that:

- ○

If the quantities X1 and X2 represent the masses of particles and Y represents the Planck mass, the equation shows the Newtonian law of gravitational force.

- ○

Conversely, if X1 and X2 represent the charges of particles and Y represents the Planck charge, the equation shows Coulomb’s law of electrostatic force.

This compact expression makes explicit that both Newton’s and Coulomb’s laws are projections of the same Planck-based structure. By using the relationship defined in equation (13) for the specific case of two electrons, we can show that the gravitational force and the electrostatic force are

From equations (14.1) – (14.2), this parallel is not a mere dimensional coincidence. Rather, it suggests the presence of a deeper scaling symmetry in nature, whereby different fundamental forces are governed by analogous structural forms, distinguished only by the property upon which they act—mass in the case of gravity, charge in the case of electromagnetism. Such a correspondence resonates with broader unification attempts in physics, where coupling constants are often normalized in Planck units. The structural similarity expressed in equations thus highlights a potential common mathematical substrate underpinning both forces. This could suggest that Newtonian gravity and Coulomb’s law are not independent phenomena, but rather distinct projections of a more fundamental interaction framework. This interpretation offers a simpler and more direct pathway grounded in the Planck scale.

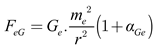

We can rearrange the expression by invoking the relationship of the fine-structure constant, as given in equation (4.2). Consequently, the electro-gravity force (

FeG) can be expressed in terms of Planck’s constant, as shown in the equation

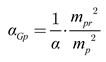

Importantly, this formulation reveals that the gravitational force can be unified with the electromagnetic force through the ratio of Newton’s gravitational force to Coulomb’s electrostatic force (

FG/

Fe). For electrons, this ratio defines the electron–gravitational coupling constant, while for protons it corresponds to the proton–gravitational coupling constant, as expressed in the equation

The latter is valued at 8.1×10

−37 [

22], where

mpr denotes the proton mass. In this unified framework,

αGe and

αGp quantify the relative weakness of gravity compared to electromagnetism, highlighting its negligible contribution at the particle scale.

summarizes the values of fundamental physical constants. Notably, these constants are related to Planck’s constant, implying that all of them are interconnected through the fine-structure constant, a key parameter in quantum electrodynamics that quantifies the strength of electromagnetic interaction. In addition to unifying gravity with electromagnetic force, this also integrates gravity with quantum mechanics.

Table 1.

Summarized the fundamental physical constant.

Table 1.

Summarized the fundamental physical constant.

| Symbol |

Quantity |

Definition |

Value |

Unit |

| Ke |

Coulomb’s constant |

Ke = mplpc2/qp2

|

8.99×109

|

N⋅m2/C2

|

| G |

Gravitational constant |

G = mplpc2/mp2

|

6.674×10−11

|

m3/kg⋅s2

|

|

G/Ke

|

Newton-Coulomb’s constant ratio |

G/Ke = qp2/mp2

|

7.424×10−21

|

C2/kg2

|

| Ge |

Effective gravitational coupling |

Ge = c2/(me/re) |

2.789×1032

|

m3/kg⋅s2

|

| h |

Planck’s constant |

h = 2πmplpc

|

6.626×10−34 |

J⋅s |

| αGe |

Electron-gravitational coupling constant |

αGe = (me/mp)2/α

|

2.4×10−43

|

- |

| αGp |

Proton-gravitational coupling constant |

αGp = (mpr/mp)2/α

|

8.1×10−37

|

- |

| α |

Fine-structure constant |

α = (mere)/(mplp) |

0.00729 |

- |

4. Discussions

The unification of gravity and electromagnetism has long motivated theoretical physics, from the early attempts of Kaluza and Klein to more recent proposals in string theory and loop quantum gravity [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. These approaches typically invoke additional structures—such as higher dimensions, supersymmetry, or quantized spacetime—thus extending the ontology of physics beyond experimentally accessible regimes. In contrast, the electro-gravity framework presented here adopts a minimalist approach. It does not require new particles, fields, or dimensions; instead, it reveals a latent symmetry embedded within fundamental constants when expressed in Planck units. By reformulating Newton’s constant

G and Coulomb’s constant

Ke under the same structural form, the framework interprets the distinction between gravity and electromagnetism not as separate interactions, but as different couplings of the same underlying principle—mass for gravity, charge for electromagnetism.

This interpretation also reframes the weakness of gravity relative to electromagnetism. Rather than an inexplicable disparity in force strengths, the ratio FG/Fe can be understood as a coupling constant that encodes a natural scaling difference with respect to the Planck system. The introduction of the electron- and proton-gravitational coupling constants (αGe and αGp) provides quantitative measures of this relationship, embedding gravitational weakness within the same framework that defines electromagnetic strength through the fine-structure constant.

4.1. Contrast with Existing Theories

Unlike higher-dimensional or emergent gravity approaches, the electro-gravity model offers a strictly algebraic and dimensionless unification. It is closer in spirit to effective field theory methods, where universal scaling relations persist across vastly different energy scales. This places the present proposal as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, quantum gravity programs, offering a phenomenological constraint grounded in known constants.

4.2. Predictive Outlook and Testability

For unification proposals to be scientifically meaningful, they must lead to predictions that can be tested or falsified. The electro-gravity framework makes several predictions and offers potential avenues for experimental and observational validation:

- ○

Precision Tests of α: If gravity contributes suppressed corrections to the fine-structure constant, these might manifest as tiny deviations detectable in atomic clock experiments or hydrogen spectroscopy. Future improvements in frequency metrology could probe this regime.

- ○

Charge-to-Mass Relations in Extreme Astrophysical Systems: The framework implies modified stability conditions for systems where electromagnetic and gravitational interactions are simultaneously extreme, such as neutron stars, magnetars, and charged black holes. Even minute deviations in charge-to-mass balance could alter collapse dynamics, radiation spectra, or magnetic field thresholds. Observations of compact object mergers, especially with simultaneous electromagnetic and gravitational-wave signals, provide a natural testbed.

- ○

Early-Universe Cosmology: In the high-energy conditions of the early universe, a coupling between gravity and electromagnetism could have influenced primordial field evolution. Potential signatures include small corrections to the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropy spectrum or modifications to primordial gravitational wave spectra.

- ○

Scaling Symmetry in Laboratory Experiments: Because the model predicts that both G and Ke share a structural Planck-based numerator (mplpc2), precise laboratory tests of dimensionless ratios involving mass, charge, and length scales may reveal internal consistency—or expose departures. High-precision Cavendish-type experiments, when cross-compared with refined electron charge-to-mass ratio measurements, could test the scaling predictions of equations (11)–(15).

In summary, the electro-gravity framework unifies Newton’s gravitational and Coulomb’s electrostatic laws within a Planck-based structure without introducing speculative new physics. Its main testable feature is the reinterpretation of gravity’s weakness as a coupling ratio, leading to small but potentially measurable corrections in atomic precision experiments, astrophysical systems, and cosmological observations. By framing unification in terms of measurable constants, the framework establishes a pathway from structural analogy toward a falsifiable physical principle.

5. Conclusions

This work was motivated by the profound structural similarity between Newton’s law of gravitation and Coulomb’s law of electrostatics—two inverse-square laws that govern phenomena across vastly different scales. Our analysis demonstrates that this similarity is not coincidental but reflects a deeper unity when expressed in Planck units. By re-deriving Coulomb’s constant (Ke) in terms of electron parameters and showing its structural equivalence to Newton’s gravitational constant (G), we revealed a shared Planck-based numerator (mplpc2 = ℏc), with the distinction arising only in the denominators—Planck charge for electromagnetism, and Planck mass for gravity. This structural symmetry enabled us to formulate a unified electro-gravity interaction, expressed as: FeG = α⋅ℏc(1+αGe)/r2, where αGe ≈ 2.4×10−43 and αGp ≈ 8.1×10−37 serve as precise, dimensionless coupling constants that quantify the relative weakness of gravity compared to electromagnetism. These constants are not ad hoc parameters but emerge naturally from the framework, linking macroscopic gravitation with microscopic electromagnetism in a cohesive structure.

A key strength of this approach is its minimalism: no hidden dimensions, exotic particles, or speculative geometries are required. Instead, the framework relies solely on known constants of nature, revealing a latent scaling symmetry that bridges classical and quantum domains. This perspective reframes gravity’s weakness not as a fundamental mystery but as a scaling consequence embedded within the same structure that defines the fine-structure constant. Most importantly, the electro-gravity framework offers testable predictions. It suggests that suppressed gravitational contributions may leave detectable imprints in precision measurements of the fine-structure constant, in charge-to-mass relations under extreme astrophysical conditions, and in cosmological observables such as the CMB or primordial gravitational wave spectra. Laboratory experiments probing the consistency of Planck-based scaling relations also provide direct avenues for falsification.

In conclusion, this paper advances a pragmatic, structurally grounded step toward unification. By situating Newton’s gravity and Coulomb’s electrostatics within a single Planck-based architecture, it provides a coherent lens through which to interpret their relationship and a roadmap for experimental validation. While preliminary, the framework lays the foundation for a testable and phenomenological pathway to unification, bridging general relativity and quantum electrodynamics without reliance on speculative constructs. Future work should focus on deriving quantitative constraints from existing data—atomic clocks, binary pulsar timing, and cosmological surveys—to place empirical bounds on the proposed coupling constants. Even null results would be scientifically valuable, as they would calibrate the limits of structural unification frameworks based solely on Planck-scale symmetries.

Acknowledgment

The author sincerely thanks Dr. Øyvind Alv Liberg for his invaluable insights, thoughtful review, and helpful discussions, comments, and advice.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Newton’s Principia, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (Translated by Andrew Motte). New York, 1846.

- G Spavieri et., al. , Physical implications of Coulomb’s Law. Metrologia 2004, 41, S159–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa D Abdullahi, (2023), Coulomb’s Law in Electrostatic, Gravitational and Inertial Forces and Emission of Radiation. Journal of Physics & Optics Sciences. SRC/JPSOS/214. /. [CrossRef]

- Pilot, C. , Q-Theory: A Connection between Newton’s Law and Coulomb’s Law?, Journal of High Energy Physics. Gravitation and Cosmology 2021, 7, 632–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, J.C. A Possible Unification of Newton’s and Coulomb’s Forces. Physics Letters A 2018, 382, 3307–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward T. H., Wu. , Gravitational Waves, Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, and Coulomb’s Law of Electrical Forces Interpreted by Particle Radiation and Interaction Theory Based on Yangton & Yington Theory. American Journal of Modern Physics 2016, 5, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P. , The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Addison-Wesley, 1964.

- Weinberg, S. , (1995), The Quantum Theory of Fields—Foundations (Vol. I). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Dirac, P. A. M. , “The Quantum Theory of the Electron,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 1928.

- Ordin S., V. , (2019), Newtons Coulomb Laws, Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: A, Physics and Space Science, vol 19:1, ver 1.0.

- Roopkom, I., et. al., (2025), A New Theoretical Framework for Unification: The Surprising Link Between Newton’s Gravity and Coulomb’s Law., Preprints.org., 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Roopkom, I., et. al., A New Perspective on Time and Gravity. Journal of High Energy Physics. Gravitation and Cosmology 2024, 10, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, M.E. , On the Structure of Electrons and Other Charged Leptons. Journal of High Energy Physics, Gravitation and Cosmology 2017, 3, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopkom, I., et. al., (2024), A New Perspective on the Fine-Structure Constant: Insights from the π/γ Ratio and Electron Dynamics., Preprints.org., 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Fritz C., J. 1: (2023), The Unification of Coulomb’s Electrostatic Law with Newton’s Gravitational Law: A Generalized Model, Journal of Biosensors & Bioelectronics, vol 14, 2023; :1. [CrossRef]

- Das, N.K. , A New Unified Electro-Gravity Theory for the Electron, and the Fundamental Origin of the Fine Structure Constant and the Casimir Effect. Journal of High Energy Physics, Gravitation and Cosmology 2021, 7, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, D. , Electronegativity: a basic link between electricity and gravity. Speculations in Science and Technology 1997, 20, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misheck, K. Laws of Gravity and Electrostatics Reduce Elementary Particles to Only Two – Positron and Negatron. Journal of Nuclear and Particle Physics 2021, 11, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutke, A. , From Newton to universal Planck natural units–disentangling the constants of nature. Journal of Physics Communications 2023, 7, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. , Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 061102–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, A. Classical Approach to a Unified Theory. International Journal of Scientific Engineering and Research (IJSER) 2021, 9, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, J.M. , Wesson, P.S. Kaluza-Klein gravity. Physics Reports 1997, 283, 303–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T. , et al. Modified Gravity and Cosmology. Physics Reports 2012, 513, 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damour, T. and Polyakov, A.M. String theory and gravity. General Relativity and Gravitation 1994, 26, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beibei Chen. The String Theory: Past and Present. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 658, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A. and Bianchi E. A short review of loop quantum gravity. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 042001. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4.1)

(4.1)

(4.2)

(4.2)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

(10)

(10)

(11)

(11)

(12)

(12)

(13)

(13)

(14.1)

(14.1)

(14.2)

(14.2)

(15)

(15)

(16)

(16)