Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Noodle Dough Culture

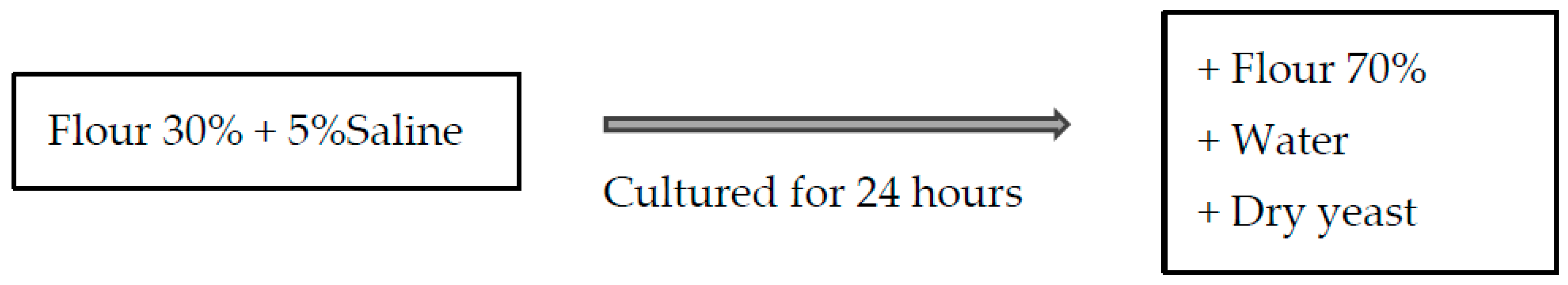

2.3. Wheat Flour Cultured in Saline (Wheat Flour Saline Culture)

2.3. Measurement of Microbial Count

2.4. Bread with a Simple Composition

2.5. Home Bakery

2.6. Statistical Processing

3. Results

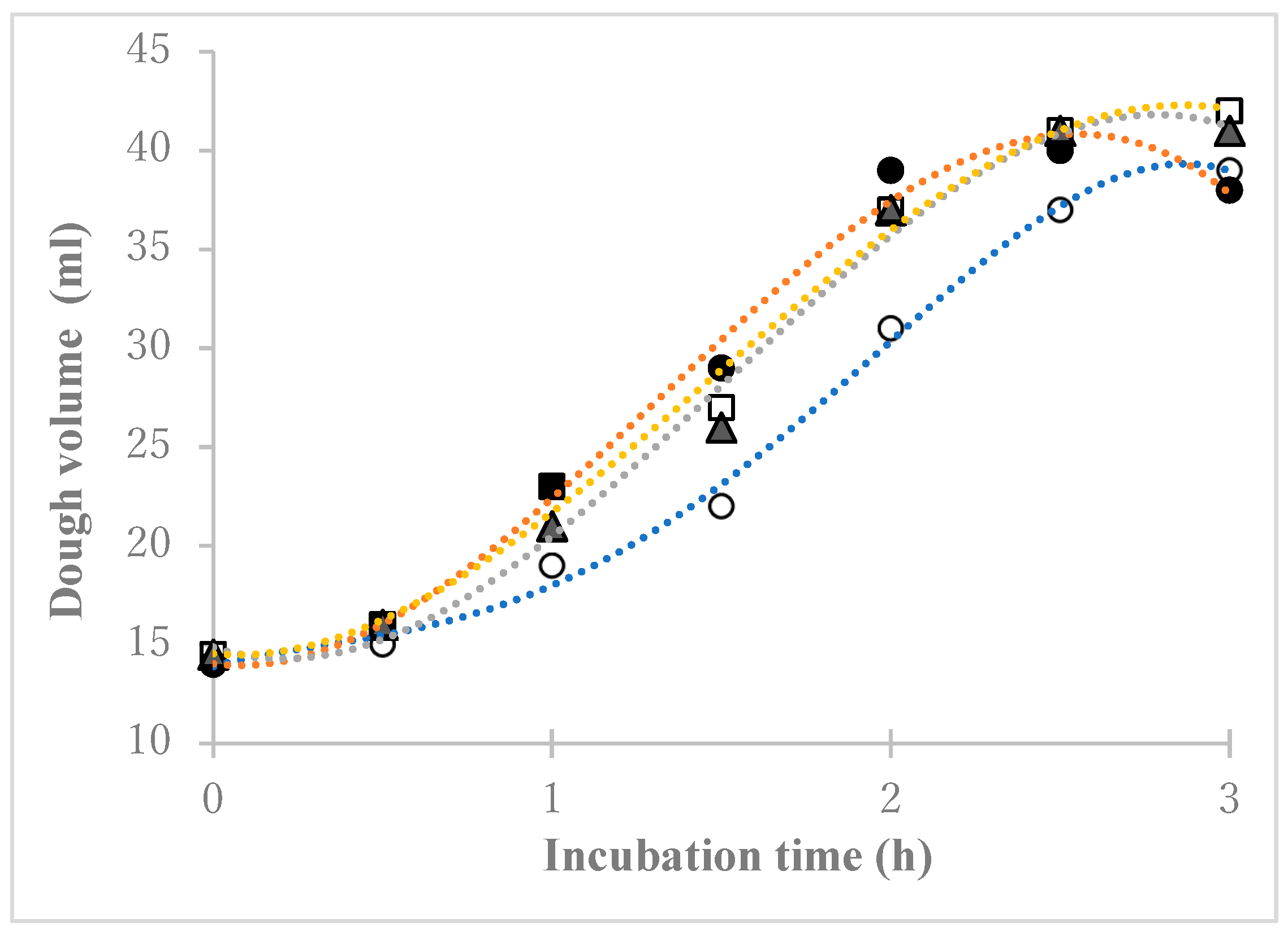

3.1. Wheat Flour Cultured in Saline

3.2. Bread Made Using Wheat Flour Saline Culture

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoshino, S. Science of Bread, 1st ed.; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 149–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y. , Matsumoto, H. Science of Bread-Making Ingredients, 1st ed.; Korin: Tokyo, Japan, 1992; pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Esaki, O. Easy-to-Understand Bread-Making Techniques, 1st ed.; Shibata Bookstore: Tokyo, Japan, 1996; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka, Y. Effect of fermentation conditions on the quality of white bread produced by sponge dough method. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1984, 31, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, A.; Hayakawa, F. Visualization of aroma by component analysis and color evaluation of bread made with commercially available baker's yeast. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 55, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, T.; Kelly, A.; Faveri, J.D.; Martin, D.; Sheppard, J.; Quail, K.; Miskelly, D. Australian wheat for the sponge and dough bread making process. Aust. J. Agri. Res. 2005, 56, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, R.; Yuan, W. Type I sourdough steamed bread made by retarded sponge-dough method. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 126029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovaara, H.; Valjakka, T. The effect of fermentation temperature, flour type, and starter on the properties of sour wheat bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1987, 22, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Ehmann, M.; Hammes, W.P. Modeling of growth of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Candida milleri in response to process parameters of sourdough fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2616–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonson, L.; Salovaara, H.; Korhola, M. Response of wheat sourdough parameters to temperature, NaCl and sucrose variations. Food Microbiol. 2003, 20, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohisa, N.; Sugawara, Y.; Mohri, S. Breads prepared by using a salt-tolerant yeast enrichment culture and dry yeast. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 67, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohisa, N.; Nakamura, K.; Cho, T.; Mohri, S. Bread fermentation seed prepared from Inaniwa udon dough in saline medium. J. Cookery Sci. Jpn. 2022, 55, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Morishima, H.; Seo, Y.; Sagara, Y.; Imou, H. Studies on rheology of white bread (part 2). J. Jap. Soc. Agric. Mach. Food Eng. 1992, 54, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohba, K.; Kawabata, A. Cooking Science Experiments, 1st ed.; Gakuken Shoin: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, A.; Ito, T.; Imura, S. Good taste produced by traditional baker's yeast and its relation with the bacteria contained in the yeasts. Seibutsu-kogaku Kaishi 2012, 6, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, A.; Ito, K.; Itou, M.; Narushima, N.; Ito, T.; et al. Microbial behavior and changes in food constituents during fermentation of Japanese sourdoughs with different rye and wheat starting materials. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 125, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, A. Fundamental studies on leavening agents for bread making. Fundamental studies on leavening agents for bread making., Kyushu University doctoral dissertation, Fukuoa-city, Japan, 2018; pp. 40–82. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2324/2236295.

- Ohisa, N.; Cho, T.; Komoda, T. Yeast-free bread using Kosakonia cowanii SB isolated from day-one culture of wheat flour. Quest Traditional food, in press.

- Mosquito, S.; Bertani, I.; Licastro, D.; Compant, S.; Myers, M.P.; et al. In planta colonization and role of T6SS in two rice Kosakonia endophytes. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrzik, K.; Brázdová, S.; Krawczyk, K. Novel viruses that lyse plant and human strains of Kosakonia cowanii. Viruses 2021, 13, 1418–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, L.A.A.; Savo Sardaro, M.L.; Duarte, R.T.D.; Mazzon, R.R.; Neviani, M.; Gatti, M.; Lindner, J.D.D. Sourdough bacterial dynamics revealed by metagenomic analysis in Brazil. Food Microbiol. 2020, 85, 103302–103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Do, E. Microorganisms in miso and soy sauce. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Microbiol. 1994–1995, 11, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, T.; Inamori, K.; Uchida, I. Classification and properties of newly isolated halotolerant lactic acid bacteria, J. Brew. Soc. Jpn. 1989, 84, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohisa, N.; Suzuki, N.; Miura, M.; Endo, K.; Fujita, Y. Halotolerant yeast participates in the cavity formation of hand-pulled dry noodles. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 59, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohisa, N.; Hoshi, Y.; Komoda, T. Bread prepared using Hyphopichia burtonii M2 isolated from ‘Inaniwa Udon’, J. Cookery Sci. Jpn. 2019, 52, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microflora1 | Strong A (cfu/g) | Strong B (cfu/g) | Strong C (cfu/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic bacteria | 4.7±2.1 (×108) | 4.5±1.0 (×108) | 2.7±0.4 (×108) |

| Salt tolerant bacteria | 2.6±0.9 (×108) | 4.0±0.2(×108) | 2.6±0.2 (×108) |

| Lactic acid bacteria | 4.6± 0.4 (×105) | 1.1± 0.1(×106) | 3.3± 1.6(×105) |

| Salt-tolerant yeast | <103 | <103 | <103 |

| Flour saline culture | Specific volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|

| Cont. | 2.25 ± 0.07 a |

| Strong A | 2.73 ± 0.12 b |

| Strong B | 3.07 ± 0.07 c |

| Strong C | 3.47 ± 0.10 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).