Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

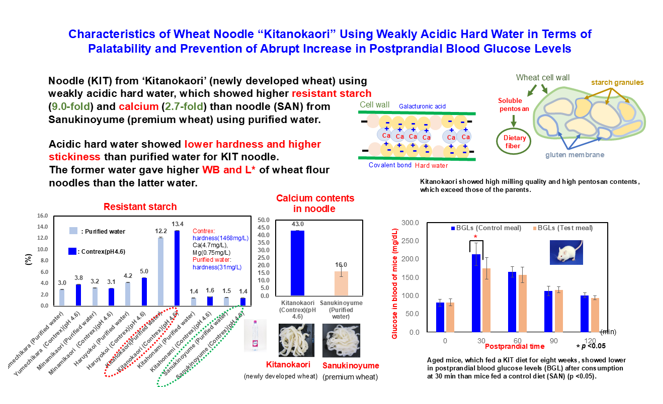

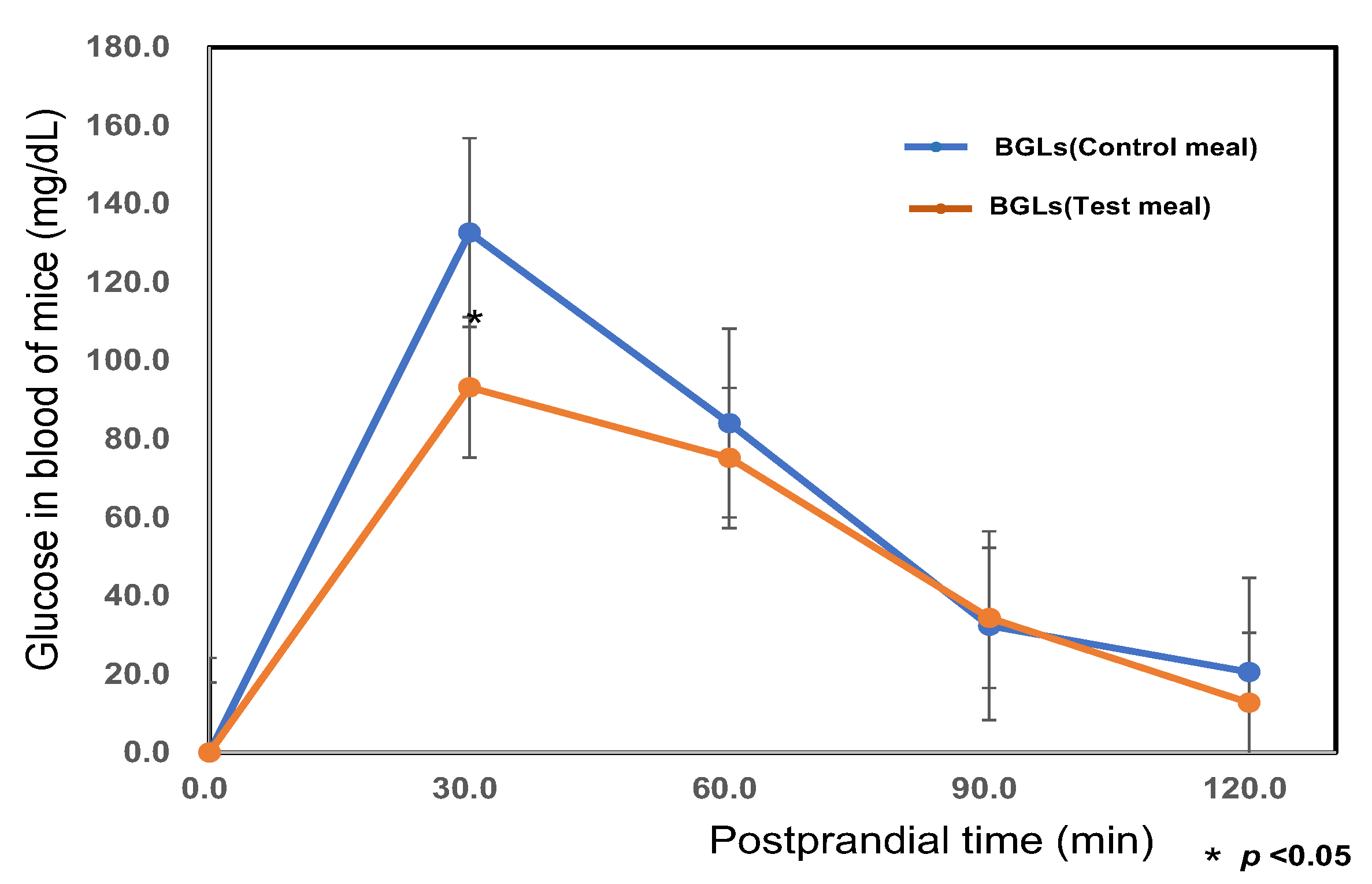

Type-2 diabetes and osteoporosis are very serious diseases all over the world. We prepared noodle (KIT) from ‘Kitanokaori’ (newly developed wheat) using weakly acidic hard water, which showed higher amount of resistant starch (9.0-fold) and calcium (2.7-fold) than noodle (SAN) from Sanukinoyume (premium wheat) using purified water. Furthermore, aged mice, which were fed a KIT diet for eight weeks, showed lower postprandial blood glucose levels (BGL) at 30 min after consumption than mice fed a control diet (SAN) (p <0.05). Additionally, whiteness (WB) and brightness (L*) of wheat noodles using weakly acidic hard water showed higher values than ones using purified water. The texture of KIT noodle using weakly acidic hard water showed little textural differences with one by purified water. The KIT noodle using weakly acidic hard water would be acceptable in terms of palatability and bio-functionality in terms of delaying digestion.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Measurement of the Moisture Contents of 6 Kinds of Wheat Flour

2.3. Analysis of Phosphorus Contents of 6 Kinds of Wheat Flour

2.4. Preparation of Wheat Starch

2.5. Iodine Absorption Spectrum

2.6. Pasting Properties

2.7. Preparation of Wheat Noodles

2.8. Measurement of Physical Properties of Various Boiled Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water or Purified Water

2.9. Measurement of Color Difference of Various Boiled Flour Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water or Purified Water

2.10. Analysis of Calcium Contents and Dietary Fiber of Various Boiled Flour Noodles

2.11. Noodle-Making for Feed

2.12. Animal Feed Test and Diets

2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phosphorus Contents of 6 Kinds of Wheat Flour

3.2. Iodine Absorption Spectrum for the Survey of Wheat Starch Microstructure

3.3. Pasting Properties of 6 Kinds of Wheat Flours in Purified Water or in Weakly Acidic Hard Water with an RVA

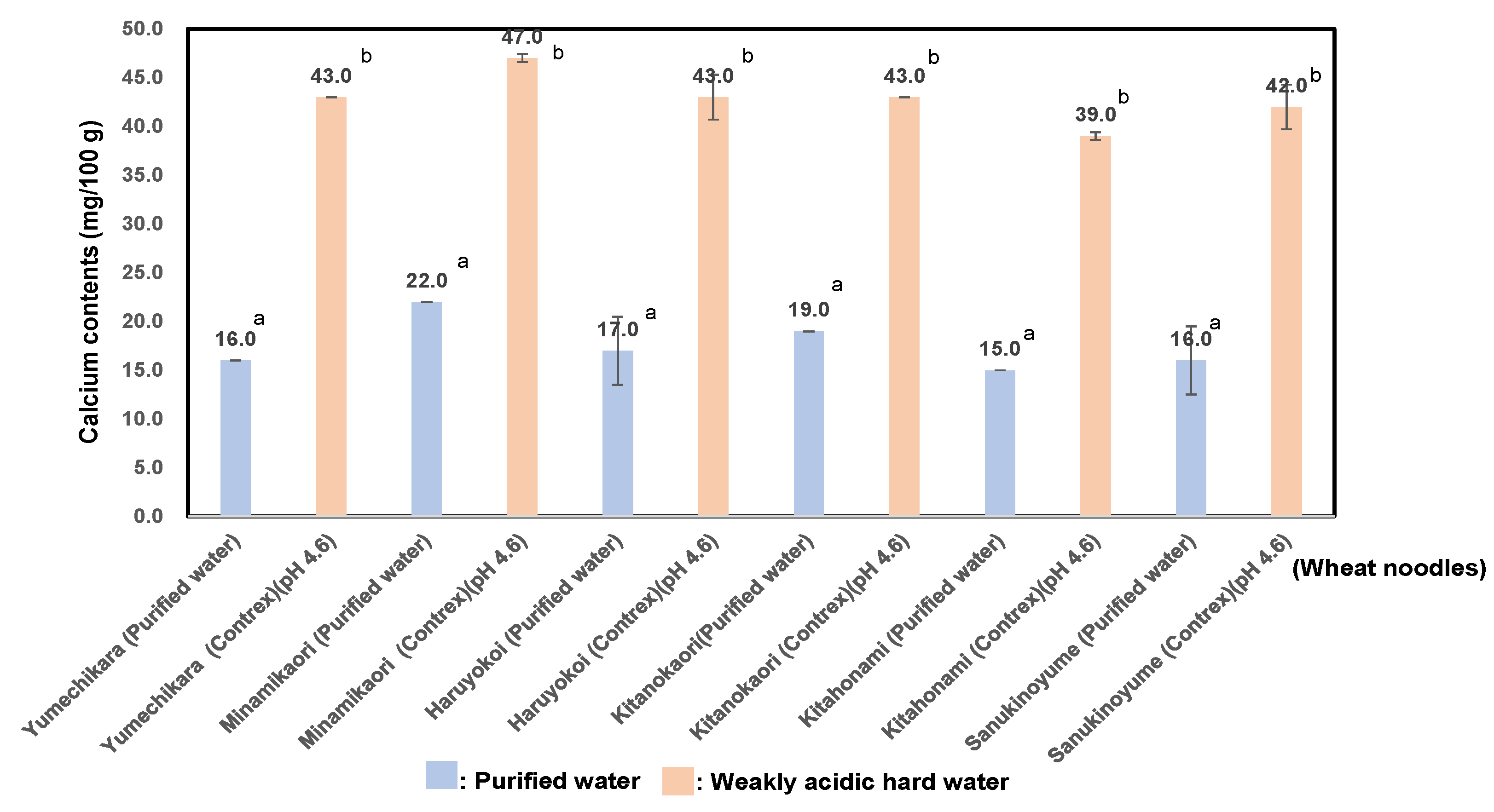

3.4. Calcium Contents in 6 Kinds of Wheat Flour Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water (pH 4.6) or the Purified Water

3.5. Textural Properties of 6 Kinds of Domestic Wheat Flour Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water (pH 4.6) or the Purified Water

3.6. Improvement of the Color of 6 Kinds of Wheat Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water, Contrex (pH 4.6)

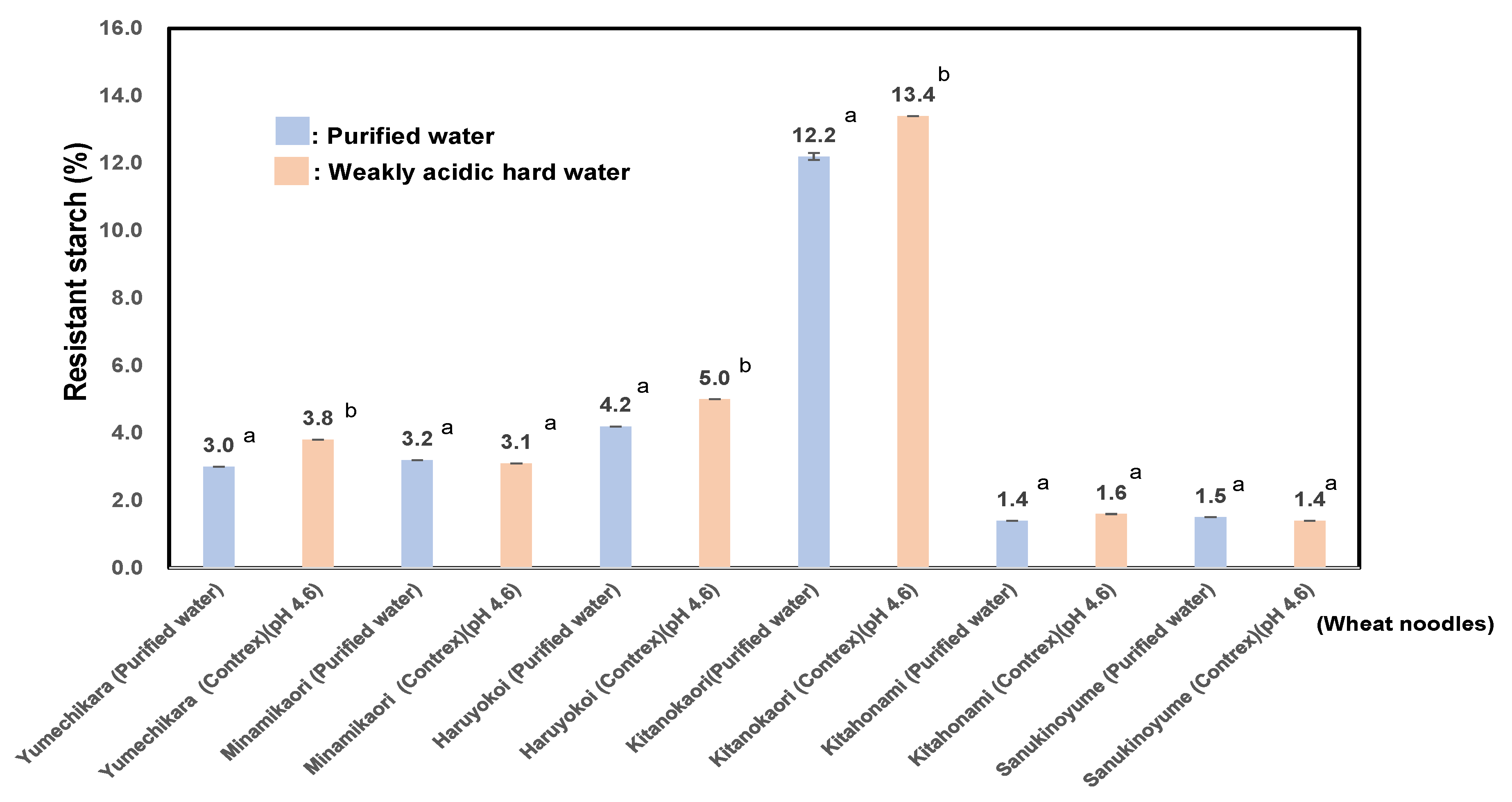

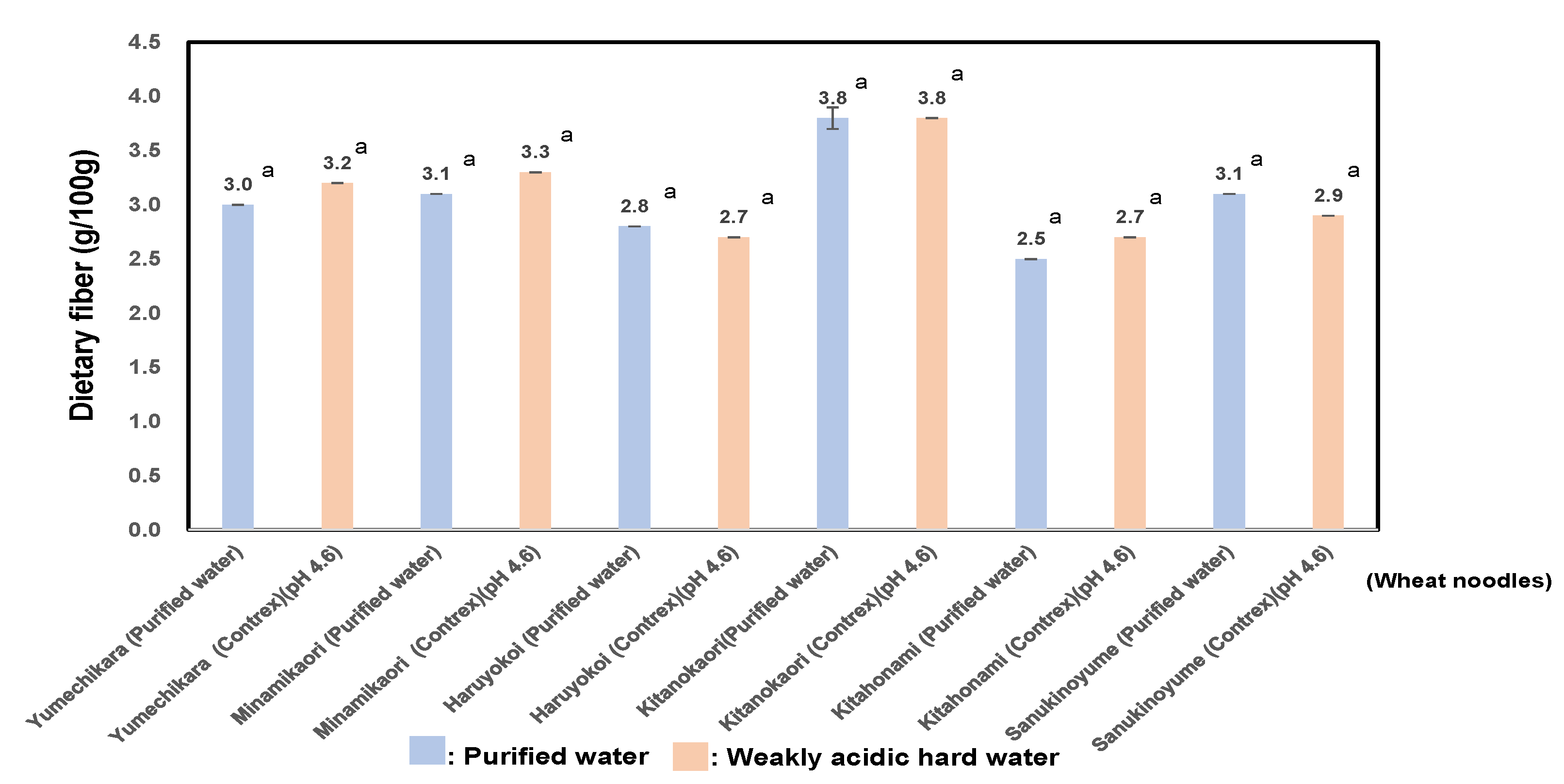

3.7. Measurement of Biofunctional Properties of RS(Resistant Starch) and Dietary Fiber of 6 Kinds of Wheat Flour Noodles Using Weakly Acidic Hard Water or the Purified Water

3.8. Determination of the Initial BGL of Aged Mice Fed with Noodle Flours Kept for 8 Weeks

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Ethical Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- The IDF (International Diabetes Federation) Diabetes Atlas 10th. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/date/en/(accessed on 7 February 2024).

- ADI (Alzheimer’s Disease International) Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer report-2015/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Nakamura, S.; Ikeuchi, T.; Araki, A.; Kasuga, K.; Watanabe, K.; Hirayama, M.; Ito, M.; Ohtsubo, K. Possibility for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus and dementia using three kinds of brown rice blends after high-pressure treatment. Foods. 2022, 11, 818. [CrossRef]

- Tomaru, M.; Takano, H.; Osakabe, N.; Yasuda, A.; Inoue, K.; Yanagisawa, R.; Ohwatari, T.; Uematsu, H. Dietary supplementation with cacao liquor proanthocyanidins prevents elevation of blood glucose levels in diabetic obese mice. Nutrition. 2007. 23, 351-5.

- Kanamoto, Y.; Yamashita, Y.; Nanba, F.; Yoshida, T.; Tsuda, T.; Fukuda, I.; Nakamura-Tsuruta, S.; Ashida, H. A black soybean seed coat extract prevents obesity and glucose intolerance by up-regulating uncoupling proteins and down-regulating inflammatory cytokines in high-fat diet-fed mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8985-93.

- Vestergaard, P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes—a meta-analysis. Osteoporos 1nt. 2007, 18, 427-444. [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Khoo, JC.; Miller, E.; Barnett, J.; Witztum, JL.; Steinberg, D. Low density lipoprotein rich in oleic acid is protected against oxidative modification: implications for dietary prevention of atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990, 87, 3894-3898.

- Nakajima, M.; Cooney, MJ.; Tu, AH.; Chang, KY.; Cao, J.; Ando, A.; An, GJ.; Melia, M.; de Juan, E jr. Normalization of retinal vascular permeability in experimental diabetes with genistein. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001, 42(9), 2110-2114.

- Villegas, R.; Gao, YT.; Dai, Q.; Yang, G.; Cai, H.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Shu, XO. Dietary calcium and magnesium intakes and the risk of type 2 diabetes. The Shanghai women’s health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89, 1-9.

- Liu, S.; Choi, HK.; Ford, E.; Song, Y.; Klevak, A.; Buring, J.; Manson, JE. A prospective study of dairy intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2006, 29(7): 1579-84. [CrossRef]

- Carson, GR.; Edwards, NM. Chapter 4: Criteria of wheat and flour quality. In WHEAT: Chemistry and Technology, Scientific Societies: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009; 97-118.

- Oda, S.; Schofield, JD. Characterisation of friabilin polypeptides. J. Cereal Sci. 1997, 26(1),29-36. [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. Puroindolines: the molecular genetic basis of wheat grain hardness. Plant Mol Biol. 2002, 48(5-6): 633-47. [CrossRef]

- Silano, V.; Pocchiari, F.; Kasarda, DD. Physical characterization of alpha-amylase inhibitors from wheat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973, 317:139. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Murayama, R.; Kodama, T.; Kitamura, I.; Inoue, S. Wheat album with amylase-inhibitory activity suppresses glycemic rise after rice loading in Human subjects. Japan Society of Nutrition and Food Science. 1999, 52(5)285-291.

- Piironen, V.; Lampi, AM.; Ekholm, P. Chapter 7: Micronutrients and phytochemicals in wheat grain. In WHEAT: Chemistry and Technology, Scientific Societies: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009; 179-222.

- Zhao, J.; Na Guo, X.; Zhu, KX. Effect of phytic acid on the appearance of yellow alkaline noodles: Color and dark spots. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 16, 103853. [CrossRef]

- Pittas, AG.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Li, T.; Dam, RM.; Willett, WC. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2006, 29(3): 650-6. [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, C.; Aoe, S. The effects of dietary calcium levels on pancreatic function in KK Mice. J Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci.2018, 71, 75-82.

- Nakamura, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Komata, C.; Katsura, J.; Maruyama, Y.; Ohtsubo, K. Palatability and bio-functionality of chalky grains generated by high-temperature ripening and development of formulae for estimating the degree of damage using a rapid visco analyzer of Japonica unpolished rice. Foods. 2022, 11, 3422. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. and Ohtsubo, K. Effects of hard water boiling on chalky rice in term of texture improvement and Ca fortification. Foods. 2023, 12, 2510. [CrossRef]

- Nagao, S.; Imai, S.; Sato, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Otsubo, H. Quality characteristics of soft wheats and their use in Japan.Ⅰ. Methods of assessing wheat suitability for Japanese products. Cereal Chem. 1976, 53(6), 988-997.

- Toyokawa, H.; Rubenthaler, GL.; Powers, JR.; Schanus, EG. Japanese noodle qualities.Ⅰ. Flour components. 1989, Cereal Chem. 66(5), 382-386.

- Pulliainen, TK; Wallin, HC. Determination of total phosphorus in foods by colorimetric measurement of phosphorus as molybdenum blue after dry-ashing: NMKL interlaboratory study. J AOAC Int. 1994;77(6):1557-61.

- Yamamoto, K.; Sawada, S.; Onogaki, I. Effects of quality and quantity of alkali solution on the properties of rice starch. Denpun Kagaku. 1981, 28, 241-244.

- Juliano, B. O.; Onate, L. M.; Mundo, A. M. A simplified assay for milled rice amylose. Food Technol. 1965, 19, 1006-1011.

- Nakamura, S.; Satoh, H.; Ohtsubo, K. Development of formulae for estimating amylose content, amylopectin chain length distribution, and resistant starch content based on the iodine absorption curve of rice starch. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 79 (3), 443-455.

- Toyoshima H.; Okadome H.; Ohtsubo K.; Suto M.; Horisue N.; Inatsu O.; Narizuka A.; Aizaki M.; Inouchi N.; Fuwa H. Cooperative test on the small-scale rapid method for the gelatinization properties test of rice flours with a rapid visco analyser. Nippon Shokuhin Kogakukaishi 1997, 44, 579-584.

- Nakamura, S.; Katsura, J.; Kato, K.; Ohtsubo, K. Development of formulae for estimating amylose content and resistant starch content based on the pasting properties measured by RVA of Japonica polished rice and starch. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 2, 329-340.

- Li, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kohyama, K.; Hu, Y.; Ohtsubo, K.; Intabon, K.; Satake, T. Quality evaluation of rice noodles made from different rice varieties. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi. 2007, 8(3): 147–154.

- Okadome, H.; Toyoshima, H.; Sudo, M.; Ando, I.; Numaguchi, K.; Ohtsubo, K. Palatability evaluation for Japonica rice grains based on multiple physical measurements of individual cooked rice grain (In Japanese). J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1998, 45,398–407.

- Nakamura, S.; Satoh, H.; Ohtsubo, K. Characteristics of pregelatinized ae mutant rice flours prepared by boiling after preroasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10665-10676.

- Borkowska-Burnecka, J.; Le´sniewicz, A.; Zyrnicki, W. Comparison of pneumatic and ultrasonic nebulizations in inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry–matrix effects and plasma parameters. Spectrochim. Acta B 2006, 61, 579–587.

- Carson, GR.; Edwards, NM. Chapter 4: Criteria of wheat and flour quality. In WHEAT: Chemistry and Technology, Scientific Societies: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009; 193.

- Balint, AF.; Kovacs, G.; Erdei, L.; Sutka, J. Comparison of the Cu, Zn, Fe, Ca and Mg contents of the grains of wild, ancient and cultivated wheat species. Cereal Res. Commun. 2001, 29, 375-382.

- Akman, Z.; Kara, B. Genotypic variations for mineral content at different growth stages in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Cereal Res. Commun. 2003, 31, 459-466.

- Blennow, A.; Nielsen, TH.; Baunsgaard, L.; Mikkelsen, R.; Engelsen, SB. Starch phosphorylation: A new front line in starch research. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 445-450.

- Hizukuri, S.; Takeda, Y.; Matsubayashi, T. The effect of phosphorus in starch granules on raw starch digestion by bacterial alpha-amylase. J. Jap. Soc. Starch Sci. 1979, 26 (2), 112-116.

- Zeng, M.; Morris, CF.; Batey, IL.; Wrigley, CW. Sources of variation for starch gelatinization, pasting, and gelation properties in wheat. Cereal Chem. 1997,74, 63.

- Medcalf, DG.; Gilles, KA. Wheat starches 1. Comparison of physicochemical properties. Cereal Chem. 1965, 42, 558-568.

- Inouchi, N.; Hibiu, H.; Horibata T.; Fuwa, H.; Itami, T. Structure and properties of endosperm starches from cultivated rice of Asia and other countries. J.Appl. Glycoscience. 2005, 52, 239-246.

- Hirano, H.; Sano, Y. Enhancement of Wx gene expression and the accumulation of amylose in response to cool temperature during seed development in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998, 39, 807-812.

- Yamamori, M.; Fufita, S.; Hayakawa, K.; Matsuki, J.; Yasui, T. Genetic elimination of a starch granule protein, SGP-1, of wheat generates an altered starch with apparent high amylose. T. Heor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 21-29.

- Takeda, Y.; Hizukuri, S.; Juliano, B. O. Structures of rice amylopectins with low and high affinities for iodine. Carbohydr. Res. 1987, 168, 79-88.

- Duffus, CM.; Murdoch, SM. Variation in starch granule size distribution and amylose content during wheat endosperm development. Cereal Chem. 1979, 56(5), 427-429.

- Regina, A.; Bird, A., Topping, D.; Bowden, S.; Freeman, J.; Barsby, T.; Kosar-Hashemi, B.; Li, Z.; Rahman, S.; Morell, M. High-amylose wheat generated by RNA interference improves indices of large-bowel health in rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 3546-3551.

- Igarashi, T.; Yanagihara, T.; Kanda, H.; Kawamoto, K.; Masaki, K. Development of new eating quality evaluation method based on iodine adsorption multispectral analysis of rice flour. J. Crop Sci. 2009, 78, 66–73.

- Nakamura S, Yamaguchi H, Benitani Y and Ohtsubo K. Development of a novel formula for estimating the amylose content of starch using Japonica milled rice flours based on the iodine absorption curve. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84(11), 2347–2359. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Morris, CF.; Batey, IL.; Wrigley, CW. Sources of variation for starch gelatinization, pasting, and gelation properties in wheat. Cereal Chem. 1997, 74, 63.

- Nakamura, S.; Katsura, J.; Maruyama, Y.; Ohtsubo, K. Relationship between fatty acid composition and starch properties of 30 japonica rice cultivars. Cereal Chem. 2018, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Hizukuri, S. Location of phosphate groups in potato amylopectin. Carbohydrate Research. 1982, 102, 321-327.

- Wren, J. J.; Merryfield, D. S. Firmly-bound’ lysolecithin of wheat starch. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1970, 21, 254.

- Fujino, Y. Complex Lipid in Food. Food Hyg. Saf. Sci. 1972, 13 (4), 257-271.

- Kim, H. O.; Hill, R. D. Physical characteristics of wheat starch granule gelatinization in the presence of cyclohepta-amylose. Cereal Chemistry. 1984, 61(5), 432-435.

- Lin Jane, J. Current understanding on starch granule structures. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2006, 53. 205-213.

- Kaneko, K.; Ota, K.; Sumino, T.; Maeda, Y. Effect of anions on binding between calcium and pectic substance. J. Nutr. Sci.Vitaminol.1989, 42 (5), 391-395.

- Kainuma, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Suzuki, S.; Takaya, K.; Fuwa, H. Studies on structure and physico-chemical properties of starch. Part Ⅳ. Structural, chemical and rheological properties of air classified small-and large granule potato starch. J. Jap. Soc. Starch Sci. 1978, 25 (1) 3-11.

- Kainuma, K.; Miyamoto, S.; Yoshioka, S.; Suzuki, S. Studies on structure and physico-chemical properties of starch. J. Jap. Soc. Starch Sci. 1976, 23 (1) 59-66.

- Nakamura, S.; Satoh, Ayaka.; Aizawa, M.; Ohtsubo, K. Characteristics of physicochemical properties of chalky grains of Japonica rice generated by high temperature during ripening. Foods. 2022, 11,97. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Katsura, J.; Maruyama, Y.; Ohtsubo, K. Evaluation of hardness and retrogradation of cooked rice based on its pasting properties using a novel RVA testing. Foods. 2021, 10, 987. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Katsura, J.; Suda, A.; Maruyama, Y. Ohtsubo, K. Effects of binding between Ca in hard water and phosphorus in amylopectin on the qualities of boiled rice and rice noodles prepared by soaking and boiling in hard water. Foods. 2024, 13, 2094. [CrossRef]

- Carson, GR.; Edwards, NM. Chapter 4: Criteria of wheat and flour quality. In WHEAT: Chemistry and Technology, Scientific Societies: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009; 195.

- Yanaka, M.; Takata, K.; Funatsuki, W.; Ishikawa, N.; Takahashi, T. Effects of the composition of glutenin subunits controlled by the Glu-A1 and Glu-D1and protein content on the noodle quality in Japanese soft wheat. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 2017, 86(2), 169-176.

- Toyokawa, H.; Rubenthaler, GL.; Powers, JR.; Schanus, EG. Japanese noodle qualities. Ⅰ. Flour components. Cereal Chem. 1989, 66, 382-386.

- Oda, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Yamauchi, Y.; Yokohama, Y. A method of flour quality assessment for Japanese noodles. Cereal Chem. 1980, 57, 253-254.

- Crosbie, GB.; Lambe, WJ.; Tsutsui, H.; Gilmour, RF. Further evaluation of the flour swelling volume test for identifying wheats potentially suitable for Japanese noodles. J. Cereal Sci. 1992, 15, 271-280.

- Crosbie, GB. The relationship between starch swelling properties, paste viscosity and boiled noodle quality in wheat flours. J. Cereal Sci. 1991, 13, 145-150.

- Noda, T. The preparation and food applications of divalent cation-substituted potato starch. J. Biorheol. 2021, 35(1) 2-9. doi.10.17106/jbr.35.2.

- Noda, T.; Takigawa, S.; Matsuura-Endo, C.; Ishiguro, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Jinno, M. Properties of Calcium-fortified potato starch prepared by immersion in natural mineral water and its food application. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2015, 62. 159-164.

- KeeBaik, B.; Czuchajowska, Z.; Pomeranz, Y. Discoloration of dough for oriental noodles. Cereal Chem. 1995, 72(2), 198-205.

- Paznocht, L.; Kotikova, Z.; Orsak, M.; Lachman, J. Carotenoid changes of colored-grain wheat flours during bun-making. Food Chem. 2019, 277(30)725-734.

- Hou, G. Oriental noodles. Adv. Food Nutr. 2001, 43, 141-193.

- Ito, M.; Ohta, K.; Nishio, Z.; Tabiki, T.; Hashimoto, N.; Funatsuki, W.; Miura, H.; Yamauchi, H. Quality evaluation of yellow alkaline noodles made from the KItanokaori wheat cultivar. Food Sci Technol. Res. 2007, 13(3), 253-260.

- Sajilate, MG.; Singhal RS.; Kulkarni, PR. Resistant starch: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2006, 5, 1-17.

- Nagahata, Y.; Kobayashi, I.; Goto, M.; Nakaura, Y.; Inouchi, N. The formation of resistant starch during acid hydrolysis of high-amylose corn starch. J. Appl. Glycosci.2013, 60, 123-130.

- Shimada, R.; Yoshimura, M. Effect of resistant starch type 4 from different starch sources on the physical properties and palatability of bread. J Biorheol. 2021, 35(1), 10-17.

- Tabiki, T.; Takata, K.; Nishio, Z.; Kuwabara, T.; Ozeki, S.; Tabaya, S.; Iriki, N.; Yamauchi, H.; Ichinose, Y. “Kitanokaori”: A new winter wheat variety. Res. Bull. Nalt. Agric. Res. Cent. For Hokkaido Reg. 2006, 185, 1-12.

- Rouau, X.; Moreau, D. Modification of some physicochemical properties of wheat flour pentosans by an enzyme complex recommended for baking. Cereal Chem. 1993, 70(6), 626-632.

- Michniewicz, J.; Biliaderis, GG.; Bushuk, W. Effect of added pentosans on some properties of wheat bread. Food Res Technol. 2001, 212, 374-376.

- Hashimoto, S.; Hino, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kai, T. Isolation and characterization of pentosans from some species of wheat flour. Bulletin of Nakamura Gakuen University. 1999, 31, 157-162.

- Shogren, MD.; Hashimoto, S.; Pomeranz, Y. Cereal pentosans: Their estimation and significance. Ⅱ. Pentosans and breadmaking characteristics of hard red winter wheat flours. Cereal Chem. 1987, 64(1), 35-38.

- Shibuya, N. and Misaki, A. Structure of hemicellulose isolated from rice endosperm cell wall: Mode of linkages and sequences in xyloglucan, β-glucan and arabinoxylan. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1978, 42 (12), 2267-2274.

- Ogata, M.; Iwasaki, N.; Uchigata, Y. Osteoporosis as a complication of diabetes. Society of Tokyo Women’s Medical University. 2017, an extra edition No.2. E142-147. [CrossRef]

- Farlay, D.; Armas, LAG.; Gineys, E.; Akhter, MP.; Recker, RR.; Boivin, G. Nonenzymatic glycation and degree of mineralization are higher in bone from fractured patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Bone Miner Res. 31. 2016, 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Oei, L.; Zillikens, M C.; Dehghan, A.; Buitendijk, GHS.; Castano-Betancourt, MC.; Estrada, K.; Stolk, L.; Oei, EHG.; Meurs, JBJ.; Janssen, JAMJL.; Hofman, A.; Leeuwen, JPTM.; Witteman, JCM.; Pols, HAP.; Uitterlinden, AG.; Klaver, CCW/; Franco, OH.; Rivadeneira, F. High bone mineral density and fracture risk in type 2 diabetes as skeletal comolications of inadequate glucose control: the Rotterdam Study. Diabetes Care. 2013, 36(6):1619-28. Pub Med. [CrossRef]

| Phosphorus | |

|---|---|

| contents | |

| (mg/100g) | |

| Yumechikara | 132.0 ± 2.6 a |

| Minaminokaori | 109.0 ± 1.5 c |

| Haruyokoi | 126.0 ± 3.2 b |

| Kitanokaori | 127.0 ± 3.0 b |

| Kitahonami | 92.0 ± 2.1 d |

| Sanukinoyume | 75.0 ± 1.8 e |

| Cultivars | AAC | λmax | Aλmax | λmax/ | Fb3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | Aλmax | (DP≧37)(%) | |||

| Yumechikara | 25.6 ± 0.5 c | 598.0 ± 2.8 a | 0.440 ± 0.003 c | 1359.1 ± 2.3 a | 18.9 ± 0.1 b |

| Minamnoikaori | 28.0 ± 0.6 a | 601.0 ± 2.8 a | 0.469 ± 0.004 a | 1282.8 ± 3.6 d | 20.2 ± 0.2 a |

| Haruyokoi | 27.2 ± 0.1 b | 599.0 ± 1.4 a | 0.461 ± 0.001 a | 1300.8 ± 5.1 c | 19.8 ± 0.0 a |

| Kitanokaori | 25.9 ± 0.3 c | 600.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.441 ± 0.004 c | 1360.6 ± 13.1 a | 18.9 ± 0.2 b |

| Kitahonami | 26.7 ± 0.3 b | 601.5 ± 0.7 a | 0.450 ± 0.005 b | 1338.2 ± 16.3 b | 19.3 ± 0.2 b |

| Sanukinoyume | 26.6 ± 0.7 b | 600.0 ± 2.8 a | 0.450 ± 0.006 b | 1333.4 ± 10.5 b | 19.3 ± 0.3 b |

| Max. vis | Mini. vis | BD | Fin. vis | SB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cP) | (cP) | (cP) | (cP) | (cP) | |

| Yumechikara (Purified water) | 2868.0 ± 25.5 a | 1263.5 ± 10.6 a | 1604.5 ± 14.8 b | 2609.5 ± 7.8 a | - 258.5 ± 17.7 a |

| Yumechikara (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 3165.0 ± 227.7 a | 1206.5 ± 46.0 b | 1958.5 ± 181.7 a | 2528.0 ± 113.1a | - 637.0 ± 114.6 b |

| Minamikaori (Purified water) | 1781.5 ± 36.1 b | 844.5 ± 26.2 a | 937.0 ± 9.9 a | 1991.0 ± 62.2 b | - 209.5 ± 26.2 a |

| Minamikaori (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 2098.0 ± 4.2 a | 1173.0 ± 5.7 b | 925.0 ± 9.9 a | 2369.0 ± 5.7 a | - 271.0 ± 1.4 b |

| Haruyokoi (Purified water) | 3139.0 ± 7.1 b | 1304.0 ± 17.0 a | 1835.0 ± 9.9 b | 2662.0 ± 25.5 a | - 477.0 ± 18.4 a |

| Haruyokoi (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 3230.5 ± 2.1 a | 1181.5 ± 13.4 b | 2049.0 ± 15.6 a | 2486.5 ± 16.3 b | - 744.0 ± 18.4 b |

| Kitanokaori (Purified water) | 2772.0 ± 38.2 b | 1214.5 ± 10.6 a | 1557.5 ± 27.6 b | 2589.5 ±23.3 a | - 182.5 ± 14.8 a |

| Kitanokaori (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 3091.0 ± 26.9 a | 1115.0 ± 7.1 b | 1976.0 ± 19.8 a | 2513.5 ± 13.4 b | - 577.5 ± 13.4 b |

| Kitahonami (Purified water) | 3177.0 ± 19.8 b | 1381.5 ± 4.9 a | 1795.5 ± 14.8 b | 2834.5 ± 6.4 a | - 342.5 ± 13.4 a |

| Kitahonami (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 3642.5 ± 244.0 a | 1386.5 ± 47.4 a | 2256.0 ± 196.6 a | 2856.0 ± 93.3 a | - 786.5 ± 150.6 b |

| Sanukinoyume (Purified water) | 4068.0 ± 9.9 b | 1580.5 ± 19.1 a | 2487.5 ± 9.2 b | 3163.0 ± 32.5 a | - 905.0 ± 22.6 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 4107.0 ± 1.4 a | 868.8 ± 0.4 b | 2706.0 ± 14.1 a | 2905.5 ± 2.1 b | - 1201.5 ± 3.5 b |

| Pt | Cons | Set/Cons | Max/Min | Max/Fin | |

| (℃) | (℃) | ||||

| Yumechikara (Purified water) | 50.5 ± 0.3 b | 1346.0 ± 2.8 a | - 0.19 ± 0.01 a | 2.27 ± 0.00 b | 1.10 ± 0.01 b |

| Yumechikara (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 59.7 ± 0.5 a | 1321.5 ± 67.2 a | - 0.48 ± 0.06 b | 2.62 ± 0.09 a | 1.25 ± 0.03 a |

| Minamikaori (Purified water) | 53.5 ± 4.7 a | 1146.5 ± 36.1 b | - 0.18 ± 0.02 a | 2.11 ± 0.02 a | 0.89 ± 0.01 a |

| Minamikaori (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 59.5 ± 0.6 a | 1196.0 ± 11.3 a | - 0.23 ± 0.00 b | 1.79 ± 0.01 b | 0.89 ± 0.00 a |

| Haruyokoi (Purified water) | 50.7 ± 0.0 b | 1358.0 ± 8.5 a | - 0.35 ± 0.02 a | 2.41 ± 0.03 b | 1.18 ± 0.01 b |

| Haruyokoi (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 59.5 ± 0.3 a | 1305.0 ± 2.8 b | - 0.57 ± 0.02 b | 2.73 ± 0.03 a | 1.30 ± 0.01 a |

| Kitanokaori (Purified water) | 55.7 ± 0.1 a | 1375.0 ± 12.7 a | - 0.13 ± 0.01 a | 2.28 ± 0.01 b | 1.07 ± 0.01 b |

| Kitanokaori (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 58.0 ± 1.3 b | 1398.5 ± 6.4 a | - 0.41 ± 0.01 b | 2.77 ± 0.01 a | 1.23 ± 0.00 a |

| Kitahonami (Purified water) | 51.2 ± 0.9 b | 1453.0 ± 1.4 a | - 0.24 ± 0.01 a | 2.30 ± 0.01 b | 1.12 ± 0.00 b |

| Kitahonami (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 59.7 ± 0.6 a | 1469.5 ± 46.0 a | - 0.53 ± 0.09 b | 2.63 ± 0.09 a | 1.27 ± 0.04 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Purified water) | 50.2 ± 0.0 b | 1582.5 ± 13.4 a | - 0.57 ± 0.02 a | 2.57 ± 0.02 b | 1.29 ± 0.01 b |

| Sanukinoyume (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 59.4 ± 0.6 a | 1504.5 ± 10.6 b | - 0.80 ± 0.00b | 2.93 ± 0.03 a | 1.41 ± 0.00 a |

| DF | RS | P | Ca | Tende | Pliab | Tough | Britt | Hard | Max.vis | Mini.vis | BD | Fin.vis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary fiber | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| RS | 0.82 ** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| P | 0.38 | 0.58 * | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Ca | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Tenderness | -0.14 | -0.38 | -0.78 ** | -0.35 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Pliability | -0.51 | -0.71 ** | -0.39 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Toughness | 0.02 | -0.32 | -0.57 | -0.32 | 0.91 ** | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Brittleness | -0.30 | -0.19 | -0.37 | 0.18 | -0.06 | 0.01 | -0.28 | 1.00 | |||||

| Hardness | 0.18 | -0.04 | 0.44 | 0.04 | -0.24 | 0.29 | 0.13 | -0.69* | 1.00 | ||||

| Max.vis | -0.30 | -0.23 | -0.52 | 0.04 | 0.57 | -0.25 | 0.39 | 0.39 | -0.63* | 1.00 | |||

| Mini.vis | -0.35 | -0.39 | -0.57 | -0.20 | 0.66 * | -0.21 | 0.46 | 0.37 | -0.66* | 0.85 ** | 1.00 | ||

| BD | -0.27 | -0.16 | -0.46 | 0.12 | 0.50 | -0.25 | 0.34 | 0.37 | -0.57 | 0.98 ** | 0.74 ** | 1.00 | |

| Fin.vis | -0.29 | -0.29 | -0.60 * | -0.20 | 0.69 * | -0.27 | 0.48 | 0.40 | -0.72** | 0.90 ** | 0.98 ** | 0.81 ** | 1.00 |

| SB | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.41 | -0.21 | -0.42 | 0.22 | -0.29 | -0.34 | 0.50 | -0.96 ** | -0.66 * | -0.99 ** | -0.74 ** |

| Pt | 0.19 | -0.17 | -0.06 | 0.76 ** | -0.28 | 0.24 | -0.23 | 0.29 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.09 | 0.07 | -0.14 |

| Cons | -0.18 | -0.13 | -0.59 * | -0.19 | 0.69 * | -0.33 | 0.47 | 0.42 | -0.75** | 0.92 ** | 0.89 ** | 0.87 ** | 0.96 ** |

| Set/cons | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.32 | -0.22 | -0.34 | 0.26 | -0.22 | -0.33 | 0.48 | -0.94 ** | -0.63* | -0.98 ** | -0.70 * |

| Max/Min | -0.11 | 0.09 | -0.19 | 0.30 | 0.20 | -0.29 | 0.11 | 0.27 | -0.39 | 0.80 ** | 0.37 | 0.89 ** | 0.49 |

| Max/Fin | -0.26 | -0.09 | -0.29 | 0.24 | 0.32 | -0.28 | 0.20 | 0.32 | -0.49 | 0.93 ** | 0.62 * | 0.97 ** | 0.69 * |

| AAC | -0.31 | -0.36 | -0.26 | 0.10 | -0.15 | 0.56 | -0.15 | -0.06 | 0.24 | -0.45 | -0.32 | -0.46 | -0.40 |

| λmax | -0.11 | -0.14 | -0.60 * | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.30 | -0.06 | 0.47 | -0.42 | -0.13 | 0.00 | -0.17 | 0.02 |

| Aλmax | -0.32 | -0.36 | -0.17 | 0.10 | -0.19 | 0.56 | -0.15 | -0.15 | 0.34 | -0.46 | -0.35 | -0.46 | -0.44 |

| λmax/Aλmax | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.13 | -0.10 | 0.21 | -0.55 | 0.15 | 0.19 | -0.38 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Fb3 | -0.32 | -0.36 | -0.17 | 0.10 | -0.19 | 0.56 | -0.15 | -0.15 | 0.34 | -0.46 | -0.35 | -0.46 | -0.44 |

| SB | Pt | Cons | Set/cons | Max/Min | Max/Fin | AAC | λmax | Aλmax | λmax/Aλmax | Fb3 | |||

| SB | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Pt | -0.15 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Cons | -0.80 ** | -0.21 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Set/cons | 0.99 ** | -0.16 | -0.76 ** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Max/Min | -0.93 ** | 0.13 | 0.63 * | -0.94 ** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Max/Fin | -0.99 ** | 0.16 | 0.75 ** | -1.00** | 0.95 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| AAC | 0.42 | 0.17 | -0.49 | 0.46 | -0.47 | -0.47 | 1.00 | ||||||

| λmax | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.29 | -0.28 | -0.30 | 0.53 | 1.00 | |||||

| Aλmax | 0.42 | 0.18 | -0.54 | 0.45 | -0.46 | -0.46 | 0.99 ** | 0.39 | 1.00 | ||||

| λmax/Aλmax | -0.40 | -0.18 | 0.55 | -0.42 | 0.44 | 0.44 | -0.97 ** | -0.32 | -1.00 ** | 1.00 | |||

| Fb3 | 0.42 | 0.18 | -0.54 | 0.45 | -0.46 | -0.46 | 0.99 ** | 0.39 | 1.00 | -1.00 ** | 1.00 |

| Tenderness | Pliability | Toughness | Brittleness | Hardness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N/cm2) | (N/cm2) | (N/cm2) | |||

| Yumechikara (Purified water) | 910.9 ± 142.7 a | 1.02 ± 0.11 a | 357.2 ± 61.4 a | 1.75 ± 0.17 a | 17.33 ± 2.52 a |

| Yumechikara (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 691.6 ± 108.4 b | 0.99 ± 0.01 a | 268.6 ±49.1 b | 1.73 ± 0.07 a | 16.67 ± 0.58 a |

| Minamikaori (Purified water) | 762.7 ± 48.4 a | 1.12 ± 0.02 a | 304.8 ± 2.8 a | 1.53 ± 0.03 a | 19.33 ± 1.15 a |

| Minamikaori (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 744.0 ± 63.7 a | 1.06 ± 0.06 a | 266.3 ± 63.4 a | 1.79 ± 0.28 a | 16.33 ± 3.51 a |

| Haruyokoi (Purified water) | 611.4 ± 62.9 a | 1.00 ± 0.04 a | 184.3 ± 18.9 b | 2.05 ± 0.06 a | 13.33 ± 0.58 a |

| Haruyokoi (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 675.7 ± 58.1 a | 0.97 ± 0.04 a | 268.2 ± 37.6 a | 1.76 ± 0.16 a | 16.67 ± 1.53 a |

| Kitanokaori (Purified water) | 841.1 ± 218.8 a | 0.92 ± 0.06 a | 302.0 ± 117.9 a | 2.09 ± 0.41 a | 14.00 ± 3.61 a |

| Kitanokaori (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 714.6 ± 91.8 a | 0.91 ± 0.02 a | 229.7 ± 26.8 a | 2.15 ± 0.19 a | 13.00 ± 2.00 a |

| Kitahonami (Purified water) | 1106.4 ± 457.0 a | 1.04 ± 0.03 a | 289.5 ± 149.6 a | 2.42 ± 0.67 a | 11.33 ± 3.51 a |

| Kitahonami (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 727.8 ± 447.8 b | 1.02 ± 0.06 a | 212.9 ± 146.9 b | 5.35 ± 4.70 a | 10.67 ± 7.51 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Purified water) | 1530.8 ± 329.3 a | 0.96 ± 0.03 a | 539.1 ± 181.2 a | 1.94 ± 0.31 a | 14.00 ± 3.00 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Contrex) (pH 4.6) | 1250.5 ± 638.0 a | 1.10 ± 0.10 a | 392.2 ± 226.1 b | 2.37 ± 1.05 a | 13.33 ± 6.11 a |

| WB | ΔE(ab) | a* | b* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yumechikara (Purified water) | 19.6 ± 2.0 b | 42.0 ± 2.0 a | -1.1 ± 0.1 a | 13.2 ± 0.7 a |

| Yumechikara (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 24.5 ± 3.2 a | 37.2 ± 2.9 b | -1.4 ± 0.3 a | 12.8 ± 0.8 b |

| Minamikaori (Purified water) | 17.3 ± 1.1 b | 44.3 ± 1.2 a | -1.2 ± 0.0 a | 14.5 ± 0.3 a |

| Minamikaori (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 21.3 ± 0.9 a | 40.1 ± 1.0 b | -1.2 ± 0.0 a | 13.8 ± 0.2 b |

| Haruyokoi (Purified water) | 21.4 ± 1.2 a | 40.4 ± 0.1 a | -1.3 ± 0.0 a | 12.1 ± 0.2 a |

| Haruyokoi (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 22.3 ± 1.0 a | 39.6 ± 0.1 a | -1.1 ± 0.0 a | 11.6 ± 0.1 b |

| Kitanokaori(Purified water) | 22.2 ± 0.0 a | 39.1 ± 0.0 a | -1.3 ± 0.1 a | 14.1 ± 0.3 a |

| Kitanokaori (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 22.3 ± 0.1 a | 38.0 ± 0.1 b | -1.4 ± 0.1 a | 14.7 ± 0.8 a |

| Kitahonami (Purified water) | 21.5 ± 1.5 b | 40.8 ± 2.1 a | -2.1 ± 0.1 a | 10.6 ± 1.8 a |

| Kitahonami (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 26.2 ± 1.0 a | 36.1 ± 0.7 b | -2.0 ± 0.1 a | 10.8 ± 0.8 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Purified water) | 24.2 ± 1.7 b | 34.7 ± 1.4 a | -2.3 ± 0.1 a | 13.6 ± 0.3 a |

| Sanukinoyume (Contrex)(pH 4.6) | 29.8 ± 1.6 a | 33.0 ± 1.2 b | -2.5 ± 0.0 a | 11.3 ± 0.3 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).