1. Introduction

The Science Shop (SS) model represents one of the most relevant public engagement tools in the context of research. It facilitates the co-creation of collaborative research projects based on the concerns and needs expressed by Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) (Gresle et al. 2021). Science Shops (SSs) involve students, researchers and other relevant stakeholders creating synergies between community needs and research development. It represents one model of community-based participatory research that aims to establish productive, mutually beneficial collaboration between community organizations and research institutions. It was first established by universities in the Netherlands in the 1970s, and from its beginning, the aim of such partnerships is to strengthen the efforts and resources and combine surrounding knowledge, lived experience and action to translate the research findings into practice. Moreover, it represents a set of research methods in health or social sciences that seek to transform the scientific enterprise by engaging communities in the research process where “Decision making power” is shared among partners in all aspects of the research process, the doing, interpreting and acting on science (Balazs et Morello-Frosch 2013).

One of the main pillars of CBPR is ethics, being even more relevant in the context of projects that address medical research, answering specific demands on health. Generally, researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct particularly when involving humans(Barrow, Brannan, et Khandhar 2022). This includes privacy, respect, anonymity, transparency, and voluntary consent. However, CBPR requires a more inclusive approach, emphasizing the reciprocity and equity in sharing roles as well as decision making and ownership between researchers and community partners (Jamshidi et al. 2014). In addition, Bradbury and Reason mentioned five characteristics of action research which are emergent developmental form, human flourishing, practical issues, participationand democracy, and knowledge in action and emphasized their importance for the validity andquality of action research (Reason 2006).

As an EU-H2020 project, InSPIRES brought together practitioners and experts from across (Spain, Netherlands, France, Hungary and Italy) and beyond Europe (Tunisia, Bolivia) to co-design, jointly pilot, implement and roll out innovative models for SSs. One of the outcomes of the project is to nurture the debate about the place and role of society in science, encouraging the systematic and ethical involvement of civil society actors and their societal concerns in the research and innovation processes.

In this study, our main goal was to identify and analyse ethical issues and challenges faced during SS projects research process from co-creation to implementation and results dissemination based on InSPIRES experience in different settings and thematic areas. We also reported examples of solutions, discussed with the research team, that were found to overcome ethical obstacles in the context of each research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pilot Projects‘s Selection

Eight pilot projects from the InSPIRES consortium’s Science Shops (SSs) were selected for qualitative assessment. The selection process involved choosing the most challenging projects (one per SS) in collaboration with SS coordinators.

2.2. Qualitative Analysis Approach

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with SS coordinators, academic project investigators, and representatives from CSOs with a focuson ethical practices, challenges, and solutions in CBPR.

The Interview questions were developed based on a literature review of CBPR ethics, covering topics like CSO inclusivity, ethical literacy, stigma, confidentiality, data sharing, and results dissemination.

A total of eight interviews, lasting one to two hours each, were conducted and interviews were recorded with participant consent, transcribed, and coded.

In total, 20 participants (academic investigators and CSO representatives) were interviewed.

Thematic analysis typically follows six steps as described by Braun and colleagues (Braun et Clarke 2006). Analysis combined inductive (data-driven) and deductive (theory-driven) approaches.

3. Results

In the current study, we used a qualitative method to assess ethical practices and challenges encountered during SS projects implementation in the frame of InSPIRES project SSs. Results are structured according to the mainly address ethical requirement of CBPR.

3.1. Inclusivity of Community and CSOs

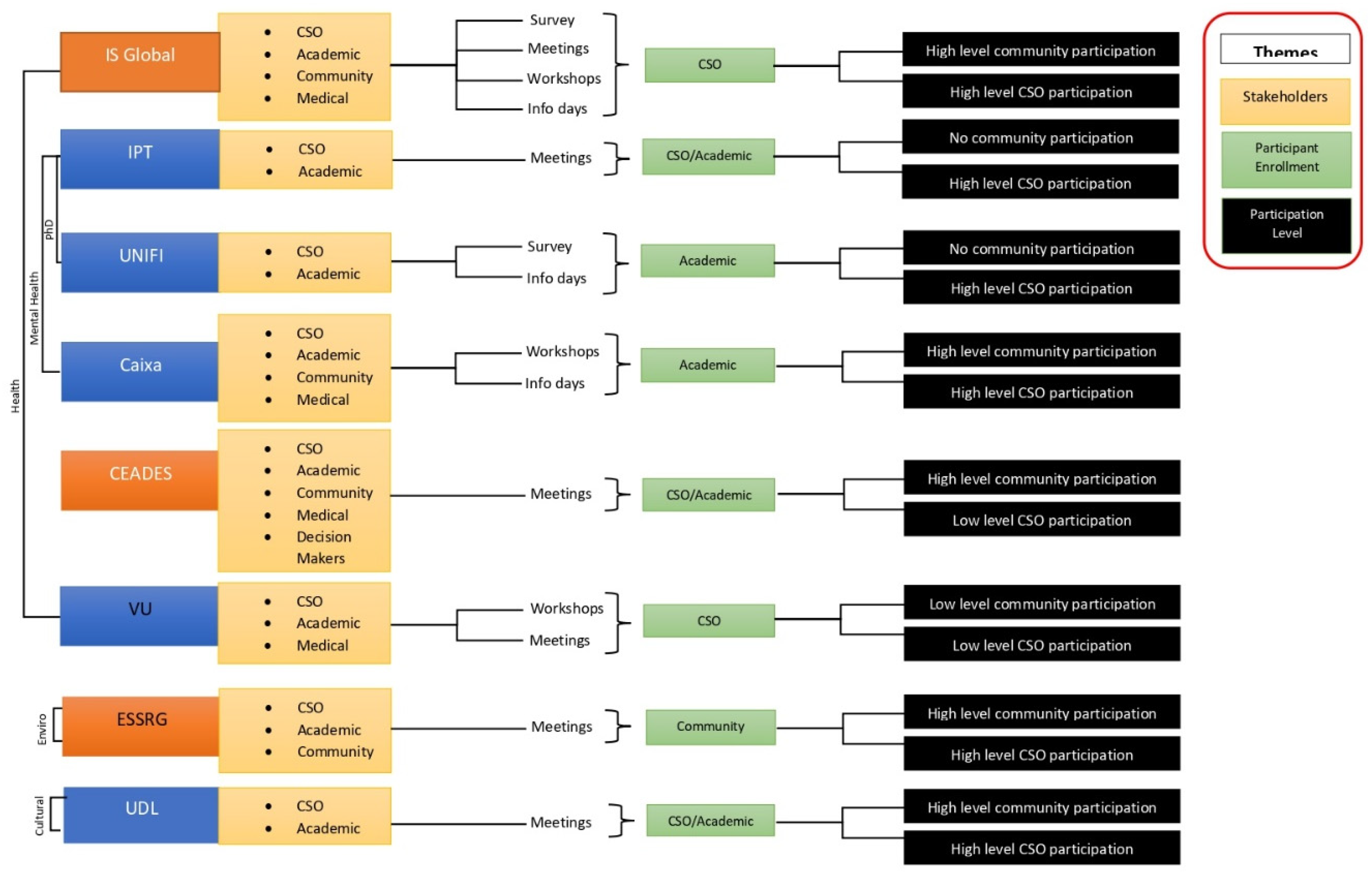

As shown in the flow chart (

Figure 1), the eight interviewed institutions were categorized according to their research area. ISGlobal, IPT, UNIFI, Caixa, VU and CEADES were all mental health or health-related projects. ESSRG was the only SS working on environmental projects and UDL worked on social projects.

Regarding the emergence of scientific questions, five out of eight projects’ research questions emerged from academic teams and for the remaining projects the research questions emerged from the CSO partners. The type of involved stakeholders was identified in each project. The five main stakeholders’ types identified were CSOs, academic institutions, patient’s communities, medical staff, and decision makers. Projects led by academic institutions had more variability in the types of stakeholders involved than those led by CSOs. Our results showed that five projects involved a high level of patient’s community participation whereas six projects had high level of CSOs participation. We observed, from interviews, that projects where CSOs or both CSOs and academic institutions have been in charge of participant enrolment and attainment of informed consent, have been shown to have high levels of community participation and involvement. On the contrary, when academic is the sole partner in charge of participant enrolment, the community and CSOs involvement level was low.

Concerning ethical considerations made by the institution at the start of the project, six institutions indicated that the ethical considerations identified influenced the design of their project and the remaining institutions did not adjust their project design based on the ethical considerations made. Taking this into consideration, we were able to make conclusions about the level of involvement of CSOs and community participants. This was defined as high, moderate, low, or no participation from these stakeholder group types (Figure1).

Community involvement in the research process was low in the majority of projects because the community was not involved in the project design, research question development, etc.

3.2. Informed Consent, Data Management Security, and Stigma

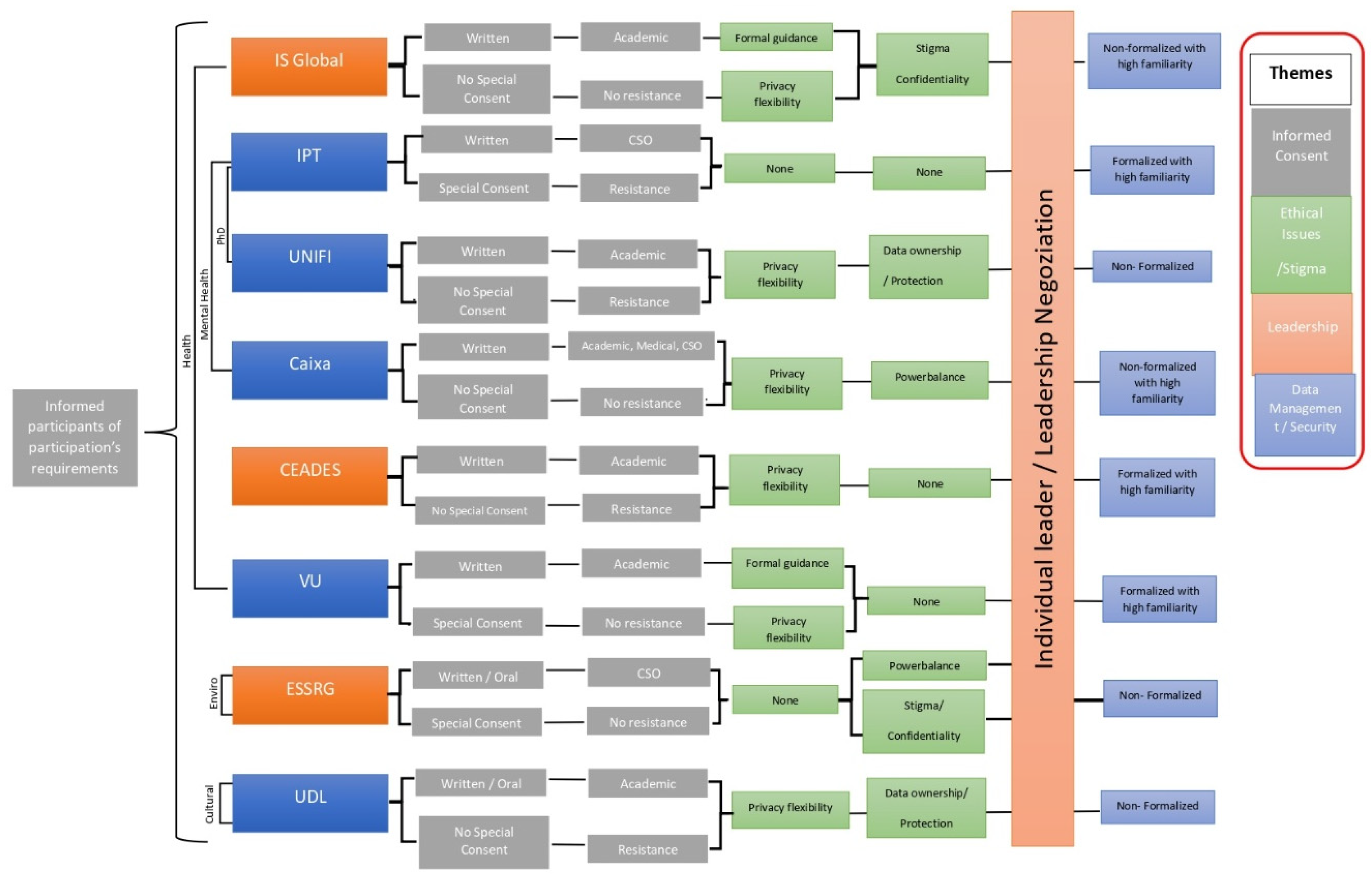

In the current study, written consent from participants was used in almost all the eight selected research projects. The first grey box (

Figure 2) describes the type of used informed consent, the second one specifies if it is an adapted one or not, the third one specifies the profile of the person who was in charge of obtaining this consent and the last one describes the behaviour of the person towards this consent. Our results showed that three of them used special consent forms that were adapted to the type of vulnerable groups involved. For instance, specificity concerned participants less than 18 years-old, participants at high risk of depression and participants with drug addiction. In these three cases, the CSO was in charge of obtaining informed consent from participants while in five remaining projects the consent was obtained by the academic institution team. However, we observed that the responsibility was shared between the academic institution, CSO and medical partner in only one project.

Regarding the consent process, participants’ resistance to consent was observed in four out of the eight projects. Among them, three involved participants with stigmatizing diseases or in “risk situation” (drug addiction, HIV and Chagas disease) and the remaining project involved a conflict of interest where participants felt apprehensive to share fully because the study was facilitated by their direct superiors. Such situation emphasizes the fact that resistance to consent is strongly influenced by vulnerability and stigma risk as well as crucial need to preserve anonymity for vulnerable groups.

In this study, three different types/situation of stigma have been identified among selected projects such as power balance (research investigator has some power on participants) (two projects), anonymity of interviewees (three projects) and no stigma identified (three projects). The last group includes projects with no specific stigma identified and obviously no particular stigma mitigation plan was needed.

As a solution, three major categories of measures have been undertaken by SSs (i) formal guidance regarding stigma for participants with stigmatizing diseases, (ii) privacy insurance for participants facing power unbalance and (iii) flexibility to adapt safe spaces for at-risk participants’ interviews. In fact, six out of the eight projects involved vulnerable participant groups including people with stigmatizing diseases as mentioned above, homeless people, participants under 18 years-old, and people with severe mental health disorders. Hence, in some cases research participants were interviewed at home in order to protect their identity (Chagas disease). In the case of participants with an addiction, interviews were conducted in the CSO space in order to protect them from the police.

Regarding data management policies, the blue boxes in Figure 2 represent the type of data management system used and its formalization status. It also describes the level of familiarity with the data management process. As result, only three out of eight SSs (IPT, CEACES and VU) have formalized a data management plan and a data security system showing an important level of familiarity with such processes and particular attention to the sensitive data protection.

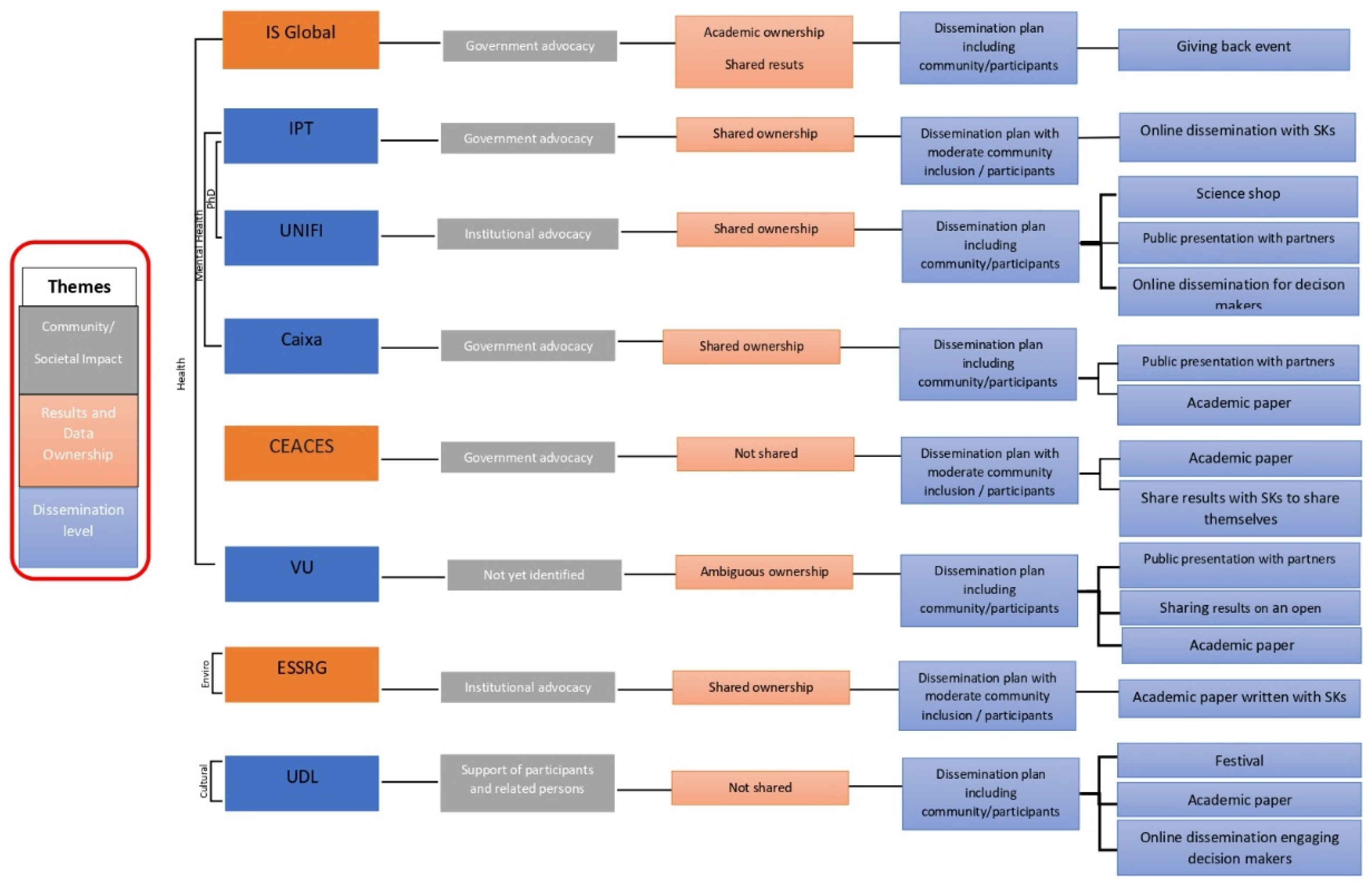

3.3. Results and Data Ownership, Dissemination and Community Impact

Project results dissemination and data ownership have been evaluated regarding the accessibility of data and results by all partners involved in the research. Different levels of ownership have been categorized into three main ownership types. (i) Category with shared ownership between CSO and academic institution (four projects), (ii) no shared ownership (two projects) and (iii) ownership status not officially formalized (ambiguous ownership) (only one project) (

Figure 3).

We assessed the level of inclusiveness of community, participants and other stakeholders in this dissemination process. Three categories have been identified: high, moderate, and low levels of dissemination. High level of dissemination includes projects involving CSOs partners, research participants and other stakeholders such as policy makers (two projects). Moderate level of dissemination involves only CSOs and academics (three projects). Low level of dissemination concerns academic institutions alone typically via research publications (three projects). Hence, the majority of selected projects showed low to moderate levels of data sharing and large results dissemination. In overall, the most important gaps identified for this section were the lack of results public dissemination and results and data sharing between academic, participant communities as well as civil organizations included in the project.

4. Discussion

Our study employed qualitative methods to assess ethical practices and challenges in the implementation of SS projects. The results are categorized according to the ethical requirements of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), highlighting significant insights into community involvement, informed consent, data management, and dissemination of results. We assessed the main ethical issues and challenges faced during CBPR projects implementation and shared lessons learned within the InSPIRES consortium, a project that was implemented in different social-cultural settings, in Europe and abroad. We focused on the main challenges faced starting from co-creation to project implementation and results dissemination based on the InSPIRES SSs projects. An overview on different solutions provided by partners, in order to overcome these challenges, has been performed. All discussed issues will help in giving guidance to researchers, partners and participants when conducting CBPR or CBPAR.

4.1. Inclusivity of Community and CSOs in the Research Process and Ethical Literacy

Our study revealed that inclusivity is a critical factor in the success of SS projects. The categorization of institutions based on their research areas (e.g., mental health, environmental projects) illustrates the diversity of focus within the SS framework. Notably, the emergence of scientific questions varied, with five out of eight projects deriving their questions from academic teams while others stemmed from CSO partners.

This distinction underscores the importance of involving community stakeholders in shaping research agendas (De Weger et al. 2018).

Based on a philosophy of partnership and principles of self-determination, equity, and social justice, CBPR aims to break down barriers between the researcher and the “researched” (Buchanan, Miller, et Wallerstein 2007; Cornwall et Jewkes 1995) by considering that people are able to assess their own needs and to act upon them (Minkler et Wallerstein 2003; Ocloo et al. 2021) and by valuing community partners as equal contributors to the research project in order to improve public health outcomes. Similarly, integrated knowledge translation approach (IKT) has been described by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) as another dynamic and iterative process including synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically based application of knowledge to improve the health system. It takes place within a complex system of interactions between researchers and “knowledge users” varying in terms of level and intensity depending on the research type, results and knowledge users’ needs (

https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html).

The ethical considerations in CBPR are particularly significant, as they ensure that the rights and needs of community members are respected throughout the research process. Addressing ethical challenges, such as informed consent and the involvement of vulnerable populations, is crucial for maintaining integrity in research practices. The findings from projects within the InSPIRES consortium highlight these ethical dimensions, revealing that many projects involve vulnerable groups and face challenges related to consent.

In addition, CBPR has emphasized the importance of creating partnerships with people for research beneficiaries. Nevertheless, taking into consideration the importance of the involvement of the community in research processes, it is clearly established that their involvement requires prerequisites and minimum requirements in terms of scientific knowledge of the investigated topics and a good understanding of their needs and environment (Jull, Giles, et Graham 2017).

Based on our findings, we were able to make conclusions about the level of involvement of CSOs. This was defined as high, moderate, low, or no participation among stakeholder group types as reported by (Elwy et al. 2022). Community involvement in the research process was low in the majority of projects since the community was not involved in the project design, research question development, etc. However, the level of CSOs involvement amongst the different selected projects differed with five of the projects having high levels of involvement and two with low levels of involvement. The main observed role of the CSOs was contribution to participant enrolment and project design due to their familiarity with the particular vulnerable group being studied and they do benefit from their trust. Supporting this statement, it has been reported that in CBPR-oriented initiatives, it is recommended to effectively include ‘‘research participants’’ and communities in the identification, definition of the scientific question and what is the best suitable methodology to answer that question as well as involving them in the interpretation of the emerging results.

In addition, participants or their representatives should be involved in the development and implementation of identified interventions to address public health problems and dissemination of results (Burdine et al. 2010).Though, such effective involvement could be very challenging regarding the participants’ scientificknowledge and research methodology skills levels in particular in populations living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICS) where the literacy rate is relatively low compared to high incomecountries, particularly among rural populations. In addition,the involvement of particular vulnerable groups and minorities in the research process represents a complex and multi-layered process considering gaps observed in health disparities, socio-economic, high level of mistrust regarding their participation in research particularly in developing countries(Bastida et al. 2010). Besides research participants’ low ethical literacy, a similar gap has also been observed among health practitioners in some projects such as nurses and technicians. Surprisingly, some doctors and senior academic researchers also showed such a limitation, highlighting the importance of training on ethical aspects among all the involved partners. Indeed, it has been reported that the increase of use of CBPR warrants the introduction of professional preparation in ethics at the undergraduate and graduate levels in health education and other professions, particularly regarding knowledge, awareness, and skills building (Bastida et al. 2010).

Indeed, such a phenomenon has been observed in the studies performed in Bolivia and Tunisia, whereas SS research projects had limited involvement of communities has been observed.

To overcome this challenge, CBPR based initiativesrecommend the importance that required skills and knowledge is expected to be transferred from researchers to community members in order to strengthen community capacity (Minkler et Wallerstein 2003). In fact, scientific investigators from Tunisia (IPT) and Bolivia (CEADES) together with CSOs scheduled specific info days or specific meetings to increase knowledge level and awareness of involved communities toward studied topics, research goals and needs. Such actions allowed the improvement of participants’ adherence to the projects besides improving the trust relationship between researchers and participants. Considering such initiatives, it has been reported that cultural adaptation must be considered especially when dealing with research skills and results dissemination (Burdine et al. 2010). In addition, effective community involvement to research process might have other constraints and barriers, despite researchers adherence to the CBPR oriented process, such as logistic costs to participants transportation, time and energy needed for participation particularly for women as observed in a project focused on reproductive health outcomes in Brazil (Díaz et Simmons 1999) and kids from most marginalized and vulnerable classes where we can observe differential costs of participation by gender (Yoshihama et Carr 2002).

Our results showed thatonly in projects where CSOs or both CSOs and academic institutions have been in charge of participant enrolment and attainment of informed consent, have been shown to have high levels of community participation and involvement. Indeed, based on InSPIRES project SSs experience (UDL, IPT, IS Global, UNIFI, ESSRG and Caixa), the role of CSO partner was of great importance in participants’ enrolments and informed consent gathering. This is not surprising since CSOs usually have a strong understanding of community’s needs, fears and vulnerability.

Besides, CSOs have cultivated strong trust relationships with their community members throughout years and have an ease in approach and communication(Lansing et al. 2023) which has significantly facilitated the enrolment process. Supporting this, a recent report pointed out that community participant could refuse to be enrolled in research due to the fear of researchers “non familiar” to them, particularly for women and elderly participants living alone at home. They have indicated that presence of community representative volunteers might make participants feel more secure and hence adhere to the research. They had crucial roles facilitating social actions and negotiations essential for the study implementation as well as resolving any unforeseen problem encountered (Dwarakanathan et al. 2018).Indeed, a similar situation has been experienced by IPT SS project working on hepatitis since interviews to people with drug addiction were conducted in the CSO local, avoiding participants ‘ identification by the local police. Another report has emphasized the importance of involving communities in the research process by acknowledging them as an equal partner in all aspects of the research via continuous consultation and collaboration, ensuring hence the relevance of the research to the community, their priorities and needs. Such synergy will allow researchers to optimize and adapt the research protocol and to have access and optimally utilize community resources (Dwarakanathan et al. 2018).

4.2. Informed Consent, Data Management Security, and Stigma

Resistance to consent was identified as a significant challenge in four projects, particularly among participants with stigmatizing conditions or those in vulnerable situations. This resistance underscores the need for researchers to be sensitive to the social dynamics affecting participant willingness to engage in research. The identification of different types of stigmas (e.g., power imbalances, anonymity concerns) further illustrates the complexities involved in conducting ethical research with vulnerable populations.

However, three SS partners used special consent forms adapted to the vulnerable groups involved, participants under 18 years-old, participants at high risk of depression and drug addiction participants. In these cases, the CSO was in charge of obtaining informed consent from participants. Nevertheless, in the five remaining projects the consent was obtained by the academic institution team. Such adaptation might be necessary in some projects, facing particular challenges during informed consent obtaining process or necessity to gather some sensitive data or biological samples from participants, obligating the investigating team to adapt their documents content or format to the situation. In fact, in some projects investigators faced some resistance to consent from participants to the research for different reasons such as academic team mistrust, fear of being issued by the police (addicted), social judgment and exclusion in case of disclosure of their identity. Other reasons to consent resistance have been reported in the literature such as the lack of a clear benefit for participants from the study results, participants or communities’ members agenda or previous participants unpleasant experiences (Dwarakanathan et al. 2018). Indeed, in some cases and due to both academics and community’s agenda, researchers didn’t take enough time to give full information and convince participants on the impact and benefits of their participation in a given research project or fail to explain in simple language.

Unfortunately, under high pressure and limited resources, it might be very challenging to totally adhere to gold standards for informed consent, leading to participants confusion, expectations mismatch and consequently lack of trust (Čebron et al. 2020).

Fear of stigma represents the most frequently observed reasons to consent to resistance in SS projects particularly in developing countries (Bolivia and Tunisia) where some diseases represent a taboo or could lead to social segregation or exclusion (HIV infection/AIDS, Hepatitis or Chagas disease). An unfavourable economic situation, such as homeless people, represents a source of stigma as well since homelesspeople might feel shame and uncomfortable when being approached and asked for their participation in a research project. Such a challenge has obligated investigators, with CSOs partner collaboration, to reorganize themselves and adapt a safe environment and spaces for participants at risk of stigma. In fact, most strategies and anticipations have worked because the design was made by specialists, so this allowed them to design the project in a better way and use a partner to reach women which has cleared most ethical issues and created a chain of confidence and trust.

Selection and enrolment of vulnerable groups participants via CSOs or community representatives mitigates significant stigma because they typically have all the required support needed to adequately represent vulnerable participants such as safe spaces, codes of conduct, selection criteria for participants, special consent forms and interpreters or qualified medical staff as needed. Overall, it could take several years to build a strong trust relationship between a community and a research institution so it is of crucial importance to maintain such a relationship for mutual benefits as long as possible.

4.3. Results and Data Ownership and Dissemination

In the current work, we have categorized the data and results ownership status into three main ownership types. Four projects pertained to the first category with shared ownership between CSO and the academic partner of all data and results, two projects reported that they didn’t share data with CSO partners and one project had ambiguous ownership status (not clearly defined and formalized). These findings highlight the fact that academics tend to take power over the research process particularly regarding data and results ownership since they consider having the “legitimacy” to own them. This is particularly due to their familiarity with data types, format and analysis as well as results dissemination process (via international publication and academic dissemination events). However, within selected SSs projects involved in this study, some particular patterns have been noted throughout conducted interviews. Most academic partners shared gathered data with their CSO partners particularly when CSOs members have contributed significantly to participants and data enrolment.

Nevertheless their “sharing process” has not always involved research results. Indeed, discordance over the dissemination and publication of research results represents one of the most common conflicts occurring between academics in the CBPR settings and it is of crucial importance to resolve such disagreements timely in order to maintain research process integrity and sustain partnership (Seifer 2006).

We observed that even if academic partners are aware of the importance of giving feedback to the community, they usually miss involving research participant in data and results interpretation as well as result dissemination planning. Besides, these activities are thought to require specific skills that might be acquired through formal training. Even though community or CSOs partners are not expert in managing databases and statistical analyses, their great knowledge of communities and their needs is of crucial importance to guide academics for more relevant analyses and interpretation of research results (Judd et al. 2005). In addition, validity of the data and the potential implications of the study results should be evaluated and discussed jointly by academic and community representatives (CSOs in this framework) and should be both active in the results dissemination process since they have access to different audience profiles.

As a recommendation, partners must not alter the research results but should prepare and present them together with community representatives that were involved in the research process, and after, share the results to the whole community in a clear, easily understandable, culturally sensitive, useful, and empowering manner. Indeed, when the results are presented jointly by the academic and community partners in easily understood language, the community is more likely to accept the results and work with the partners to develop and implement interventions.

Overall, disagreements are likely to occur when conducting participatory research with numbers of partners with different profiles and different backgrounds. It has been reported that conflict management might be facilitated when the partners have developed a strong trust and respect relationship which must be formalized by written and signed agreement (or Memorandum of Understanding: MOU) from the start of the project which has not been largely formalized among SSs selected projects. Issues and discords should be anticipated and discussed at an early stage in the process and possible solutions agreed.

Adequate planning and a detailed MOU, conflicts may not be avoided, but they are more likely to be resolved in a manner that will facilitate the research process for better community outcomes (Wilkins 2011).

5. Conclusions

Overall, the findings from our study highlight both progress and challenges in implementing ethical practices within SSs projects. While there are notable examples of effective community engagement and ethical considerations, significant barriers remain regarding inclusivity and participation levels among community stakeholders. Addressing these challenges will require ongoing efforts to foster genuine partnerships between researchers and communities, ensuring that all voices are heard and valued throughout the research process.

Conducting CBPR is a complex and dynamic process involving a variety of partners and stakeholders from different background, resulting in high risk of conflicts and disagreement. Our main results pointed several faced issues resulting in several recommendations. One of them is that all partners must agree, from the start, on a well-designed, documented and formalized data and results ownership, interpretation and results dissemination plan (by signing MOU).

Ethical pathway in each intervention should be agreed before starting the project, and the engagement of CSO in ethical procedures would be key for its success. All stakeholders should, also, agree on a data protection approach they will use in order to preserve participants anonymity and mitigates any stigma risk via an adapted approach taking in consideration community particular requirements, resources, level of knowledge and culture. Sharing responsibility and benefits must be agreed and formalized for better research outcomes on communities. A well-designed public results dissemination plan should be considered with communities as well to strengthen a trust and a win-win based relationship.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, M.K, A.SG, S.A, H.BH and MJ.P; methodology, M.K, AS.G, H.BH and I.JM; software, M.K, H.BH I.JM and J.T; validation, S.A, H.BH, MJ.P; formal analysis, M.K, J.T and J.BAH; investigation, M.K, J.T and J.BAH; resources, M.K, J.T and J.BAH and H.BH; data curation, M.K, J.T and J.BAH; writing—original draft preparation, M.K, J.T and J.BAH; writing—review and editing MJ.P, S.A, A.SG and and H.BH; visualization, M.K and J.BAH; supervision, MJ.P and S.A; project administration, A.SG, H.BH and S.M; funding acquisition, MJ.P (InSPIRES consortium). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union in the frame of Horizon 2020 program as members of InSPIRES (

https://www.inspiresproject.com/)“Ingenious Science shops to promote Participatory Innovation, Research and Equity in Science”, grant agreement No 741677.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require any IRB or ethical committee approval since no sample or personal data have been collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consents were obtained from interviewees from each SS for interview records and transcription.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was done thanks to the consistent and effective contribution of all InSPIRES project partners: ISGlobal, Institut Pasteur de Tunis, VU Amsterdam, CEADES, ESSRG, Université de Lyon, University of Florence, Irsi Caixa. Particular thanks go to all SSs coordinators for their precious collaboration and interview coordination.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors have approved the submission of this article in its current version.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSs |

Science Shops |

| CBPR |

Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CSO |

Civil Society Organization |

| IKT |

Integrated Knowledge Translation |

| IPT |

Institut Pasteur de Tunis |

| UDL |

Université de Lion |

| ISGLOBAL |

Barcelona Institute for Global Health |

| UNIFI |

University of Florence |

| CEADES |

Ciencia y Estudios Aplicados para el Desarrollo en Salud y Medio Ambiente |

| VU |

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam |

| LMICS |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| InSPIRES |

Ingenious Science shops to promote Participatory Innovation, Research and Equity in Science |

References

- Balazs, Carolina L., et Rachel Morello-Frosch. 2013. « The Three Rs: How Community-Based Participatory Research Strengthens the Rigor, Relevance, and Reach of Science ». Environmental Justice 6(1):9-16. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, Jennifer M., Grace D. Brannan, et Paras B. Khandhar. 2022. « Research Ethic ».

- Bastida, Elena M., Tung-Sung Tseng, Corliss McKeever, et Leonard Jack. 2010. « Ethics and Community-Based Participatory Research: Perspectives From the Field ». Health Promotion Practice 11(1):16-20. [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, et Victoria Clarke. 2006. « Using thematic analysis in psychology ». Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2):77-101. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, David Ross, Franklin G. Miller, et Nina Wallerstein. 2007. « Ethical Issues in Community-Based Participatory Research: Balancing Rigorous Research With Community Participation in Community Intervention Studies ». Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 1(2):153-60.

- Burdine, James N., Kenneth McLeroy, Craig Blakely, Monica L. Wendel, et Michael R. J. Felix. 2010. « Community-Based Participatory Research and Community Health Development ». The Journal of Primary Prevention 31(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Čebron, Urška, Calum Honeyman, Meklit Berhane, Vinod Patel, Dominique Martin, et Mark McGurk. 2020. « Barriers to Obtaining Informed Consent on Shortterm Surgical Missions ». Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open 8(5):e2823. [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, Andrea, et Rachel Jewkes. 1995. « What Is Participatory Research? » Social Science & Medicine 41(12):1667-76. [CrossRef]

- De Weger, E., N. Van Vooren, K. G. Luijkx, C. A. Baan, et H. W. Drewes. 2018. « Achieving Successful Community Engagement: A Rapid Realist Review ». BMC Health Services Research 18(1):285. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, Margarita, et Ruth Simmons. 1999. « When is Research Participatory? Reflections on a Reproductive Health Project in Brazil ». Journal of Women’s Health 8(2):175-84. [CrossRef]

- Dwarakanathan, Vignesh, Alok Kumar, Baridalyne Nongkynrih, Shashi Kant, et SanjeevKumar Gupta. 2018. « Challenges in the Conduct of Community-Based Research ». The National Medical Journal of India 31(6):366. [CrossRef]

- Elwy, A. Rani, Elizabeth M. Maguire, Bo Kim, et Gavin S. West. 2022. « Involving Stakeholders as Communication Partners in Research Dissemination Efforts ». Journal of General Internal Medicine 37(1):123-27. [CrossRef]

- Gresle, Anne-Sophie, Eduardo Urias, Rosario Scandurra, Bálint Balázs, Irene Jimeno, Leonardo de la Torre Ávila, et Maria Jesus Pinazo. 2021. « Citizen-Driven Participatory Research Conducted through Knowledge Intermediary Units. A Thematic Synthesis of the Literature on “Science Shops” ». Journal of Science Communication 20(5):A02. [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, Ensiyeh, Esmaeil Khedmati Morasae, Khandan Shahandeh, Reza Majdzadeh, Elham Seydali, Kiarash Aramesh, et Nina Loori Abknar. 2014. « Ethical Considerations of Community-based Participatory Research: Contextual Underpinnings for Developing Countries ». International Journal of Preventive Medicine 5(10):1328-36.

- Judd, Nancy L., Christina H. Drew, Chetana Acharya, Todd A. Mitchell, Jamie L. Donatuto, Gary W. Burns, Thomas M. Burbacher, Elaine M. Faustman, et null null. 2005. « Framing Scientific Analyses for Risk Management of Environmental Hazards by Communities: Case Studies with Seafood Safety Issues ». Environmental Health Perspectives 113(11):1502-8. [CrossRef]

- Jull, Janet, Audrey Giles, et Ian D. Graham. 2017. « Community-Based Participatory Research and Integrated Knowledge Translation: Advancing the Co-Creation of Knowledge ». Implementation Science 12(1):150. [CrossRef]

- Lansing, Amy E., Natalie J. Romero, Elizabeth Siantz, Vivianne Silva, Kimberly Center, Danielle Casteel, et Todd Gilmer. 2023. « Building trust: Leadership reflections on community empowerment and engagement in a large urban initiative ». BMC Public Health 23(1):1252. [CrossRef]

- Minkler, Meredith, et Nina Wallerstein. 2003. « Part one: Introduction to community-based participatory research ». Community-based participatory research for health 5-24.

- Ocloo, Josephine, Sara Garfield, Bryony Dean Franklin, et Shoba Dawson. 2021. « Exploring the Theory, Barriers and Enablers for Patient and Public Involvement across Health, Social Care and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review of Reviews ». Health Research Policy and Systems 19(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Reason, Peter. 2006. « Choice and Quality in Action Research Practice ». Journal of Management Inquiry 15(2):187-203. [CrossRef]

- Seifer, Sarena D. 2006. « Building and Sustaining Community-Institutional Partnerships for Prevention Research: Findings from a National Collaborative ». Journal of Urban Health 83(6):989-1003. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, Consuelo H. 2011. « Communicating Results of Community-Based Participatory Research ». The Virtual Mentor: VM 13(2):81-85. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihama, Mieko, et E. Summerson Carr. 2002. « Community Participation Reconsidered ». Journal of Community Practice 10(4):85-103. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).