1. Introduction

Breast milk, unique source of energy and nutrients for newborns, not only provides optimal nutrition, but also promotes the immune system, metabolic growth, and cognitive development. In addition to maternal immune factors and appetite-regulating hormones, breast milk contains bioactive components that are thought to support the development of a healthy infant gut microbiome [

1,

2,

3].

Breastfeeding provides bacterial content for a potentially beneficial microbiome. In studies conducted via culture-based analysis methods, it was determined that breast milk from healthy women contains 103-105 ml of viable bacteria and more than 207 bacterial genera [

4]. The Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Propionibacterium phyla, which are the most abundant in the breast milk microbiota, have been identified as the core genera [

5]. Geographic location, body mass index, mode of delivery, lactation time, and methods of milk collection affect both the diversity and composition of the breast milk microbiota [

6]. However, Fitzstevens et al. [

7] determined that Streptococcus and Staphylococcus can be universally dominant in breast milk, without considering differences in geographical location or analytical methods.

The exact origin of the bacteria in the breast milk microbiota is not known. However, the formation time of these bacteria coincides with the perinatal period, which starts in the third trimester of pregnancy and continues during lactation [

8,

9]. The maternal skin microbiota, oral microbiota of the newborn during suction, or maternal gut microbiota formed by the maternal intestinal-breast pathway are proposed to be the source of bacteria in the breast milk microbiota [

10,

11]. Moreover, commensal bacteria were detected in the breast tissue, suggesting that these bacteria colonize in the milk ducts in the presence of bacteria unique to the breast tissue [

9,

12].

The microbial composition of the human gut, where bacteria are abundant, mainly includes essential anaerobes. Four main bacterial phyla, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria generate the vast majority of bacteria in the human gut. Among this phylum, Bacteriodetes and Firmicutes are the two most dominant bacterial phyla, whereas the Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia phyla are less concentrated in the human gut microbiota [

13,

14].

The postpartum period is one of the most significant and unique processes in human life, where microbial colonization of the fetus begins and changes. The maternal gut microbiota and breastfeeding have crucial influences on infant health and development. However, some studies have evaluated the gut microbial composition during the postpartum period and in breast milk during the lactation period, and most of these studies are prone to alterations in bacterial profiles and diversity among stages [

15,

16]. Therefore, we aimed to identify the microbial composition and diversity of maternal fecal samples from postpartum and mature breast milk of healthy women

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

We recruited 20 healthy breastfeeding women at Gülhane Education and Research Hospital between April 2018 and July 2018. The inclusion criteria were a single live birth, age 19–35 years, a normal gut frequency, and term delivery. The exclusion criteria were chronic diseases (thyroid and parathyroid disease, type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic bone or kidney disease), polycystic ovary syndrome, infectious disease, alcohol consumption, smoking, abnormal liver function, mastitis during lactation, having chemotherapy, antibiotics, and the use of probiotics.

We conducted all procedures following the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical committee of the Non-Interventional Clinical Researches Ethics Board of Hacettepe University approved this study complies with ethical principles with code GO 18/218-12. We obtained written informed consent from all volunteered breastfeeding women.

This study was recorded in the US National Library of Medicine with the registration number NCT04072627.

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements and Sociodemographic Attributes

We collected demographic and clinical information such as age, parity, and breastfeeding duration from the women. Additionally, we measured the weight and height of the breastfeeding women. We calculated the postpartum body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg)/height (m2) and evaluated it on the basis of the World Health Organization classification [

17]. We collected fecal samples (15 g) from women on the 15th postpartum day into a sterile stool container with a lid and kept them in a special box with a temperature at 4°C for 30 minutes. We divided the fecal samples into two pieces by a sterile stool spoon in the laboratory and then stored them in a -80°C freezer until DNA extraction.

Additionally, we collected breast milk samples from healthy women at 16. days postpartum between March and August 2018. Before we started collecting the breast milk samples, we wore sterile gloves and cleaned the nipples and areolas of the women with chlorhexidine wipes to eliminate contamination from skin bacteria in the samples. We discarded the first few drops (approximately 1 ml) of breast milk to prevent chlorhexidine contamination and collected the milk samples (20 ml) in a sterile tube by manual expression from both nipples. We kept the samples in a special box at 4°C for one hour and stored them afterwards in a -80°C freezer until DNA extraction.

2.3. DNA Extraction

We extracted total DNA from 1.5 ml of each breast milk sample via the EurX GeneMATRIX Tissue and Bacterial DNA Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (EURx, Gdansk, Poland). For the extraction protocol, 1.5 ml of each breast milk sample was transferred to a 2.0 ml microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 5000 rpm at 4°C for 20 minutes. We carefully removed the fat rim using a sterile swab, and the resulting supernatant was stored for future analysis. We washed the pellet in 200 μL of lysis buffer, mixed it thoroughly by vortexing, and incubated it at 70°C for 10 min. Then, we added 200 μL of 96% ethanol and mixed it thoroughly by vortexing. We centrifuged the suspension at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 1 min. We transferred the whole lysate to the spin column, placed it in the collection tube, and centrifuged it at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 1 min. We removed the spin column, discarded the flow through, and placed the spin column in the collection tube. We performed the next steps in the analysis involving washing samples with wash TX1, TX2, elution buffer, and centrifugation according to the manufacturer’s application procedure. Consequently, we obtained good quality genomic DNA with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0, as measured on a NanoDrop 2000c. We used a Qubit 4 fluorometer with a Qubit 1X dsDNA HS Assay Kit to measure the amount of double-stranded intact DNA accurately. We ensured that all the isolated DNA samples had a concentration of at least 25 ng/μL and then stored them at -20°C for further analysis.

2.4. Library Preparations

We amplified the V3 and V4 hypervariable regions [

18] of the 16S rRNA gene for each sample by using the XXX primer pair (forward primer: 5’-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTAC GGGNGGCWGCAG-3’ and reverse primer: 5’-GTCTCGTGGG CTCGGAGATGTGTATAA GAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3’) [

19].

We carried out the PCRs in a total volume of 50 μL, containing 2.5 μL of genomic DNA, 1.5 μM, 5.0 μL of amplicon PCR forward primer, 1.5 μM 5.0 μL of amplicon PCR reverse primer, and 12.5 μL of 2xKAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix. (Roche, Basel Switzerland) and 25.0 μL Invitrogen UltraPure DNase⁄RNase-Free Distilled Water PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The thermal cycling steps in the PCR program were 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 25 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 5 minutes.

After confirming the success of this first PCR through agarose gel electrophoresis, the gel was run at a concentration of 1.5% agarose under the voltage of 100 V for 60 minutes. Then, we purified our PCR products to remove primer dimers and free primers via AMPure XP magnetic beads and an EpiMag HT Magnetic Separator which includes several binding and washing steps. To dilute the PCR products for index binding, a molecular biology grade 1 M pH 8.0 Tris-HCl solution was diluted to 10 mM. We used the Nextera XT index kit and connected two index barcode regions to the 5’ and 3’ ends of each amplicon in the index PCR process to barcode them before sequencing. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to confirm index binding and a second round of PCR with the same procedure was carefully applied.

We carried out normalization and pooling of index-added DNA libraries according to Illumina 16S rRNA metagenomic library preparation instructions by measuring DNA quantity via Qubit 4 and pooling it at equimolar concentrations. The total amount of pooled concentrated library was adjusted to 4 nM, by following the formulas given to each sample to be represented equally after sequencing. To prepare for clustering and sequencing, we denatured the pooled libraries with NaOH solution, diluted them with hybridization buffer and heat denatured them before sequencing. Our final library mixture contained 5.0% of the PhiX library as a control.

2.5. Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

We performed 2*300 bp sequencing of the 16S rRNA amplicons on the Illumina MiSeq platform, through bridge amplification and sequencing by synthesis. We followed the 16S rRNA gene metagenomic protocol and classified the organisms in the V3 and V4 amplicons via the use of a gene database. MiSeq sequencing of human milk and infant fecal samples yielded a total of 20,206,055 reads, with mean read lengths of 460 bp (330–591 bp). We extracted FASTQ-formatted files from the raw data for downstream analysis.

We determined the quality of the reads through FastQC and filtered reads that had Phred scores lower than 20 with the FASTX extension. We performed a quality assessment of the reads with Fastqp and demultiplexed of the reads according to barcodes assigned during library preparation. All the other filtering steps, diversity analysis and taxonomic classification were performed in QIIME2 by using default options [

20].

Reads representing primer sequences on the 5’ end and low quality reads due to Illumina 2*300 bp sequencing chemistry on the 3’ end were extracted to achieve data representing sequence diversity more effectively.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We investigated the normal distribution of the evaluated variables via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We present the values as numbers, percentages, and means ± standard deviations (SDs). We indicated the bacterial counts as the relative abundance of all the phyla in the third trimester and lactation period. First, we calculated the Shannon index to estimate the alpha diversity of each sample and used the Wilcoxon test to compare the samples. We analyzed the data via IBM SPSS version 22.0 and considered p<0.05 to indicate statistical significance. Second, we computed the β diversity distance between samples in QIIME2 on the basis of unweighted UniFrac distance matrices. We further determined factors explaining the variation via PERMANOVA tests with 999 permutations.

We needed 20 women to have a statistical power of 80% and a two-sided significance level of 5% via the PASS (power analysis and sample size) software program to determine a clinically significant difference in bacterial diversity between fecal samples and breast milk samples according to similar methods [

4,

21].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Anthropometric Measurements

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics and anthropometric measurements of the study participants. We evaluated 123 breastfeeding women according to the inclusion criteria. Twenty of these women refused to participate in the study, 22 of whom did not meet the inclusion criteria, and we excluded 81 women due to health problems. Therefore, we included a total of 20 healthy breastfeeding women who met the inclusion criteria. The average age of the women was 24.2 ±2.94 years, and the mean BMI of the women in the postpartum period was 25.4±2.32 kg/m2. Additionally, approximately 75.0% of women had at least a high school degree.

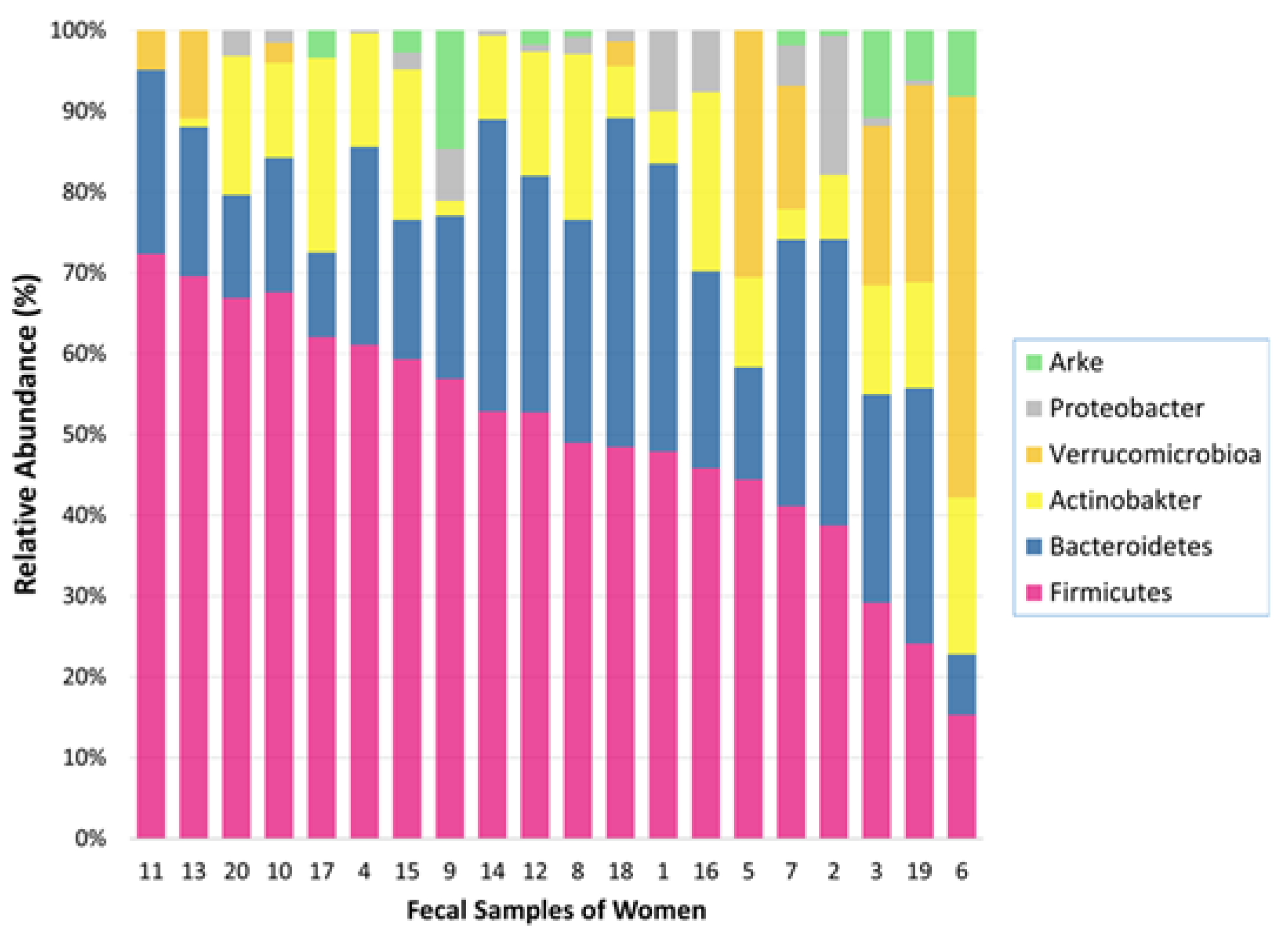

3.2. Microbial Composition of Postpartum Fecal Samples

We classified the OTUs (operational taxonomic units) into taxa and identified a total of 5 phyla, 11 classes, 15 orders, 28 families, 45 genera, and 68 species in the fecal samples of 20 healthy postpartum women. The gut microbiota composition of postpartum women was dominated by the phyla Firmicutes (mean relative abundance: 50.2%) and Bacteroidetes (24.2%) and, to a lesser extent Actinobacteria (11.9%), Verrucomicrobia (8.1%), and Proteobacteria (3.0%) in the fecal samples of women (

Figure 1).

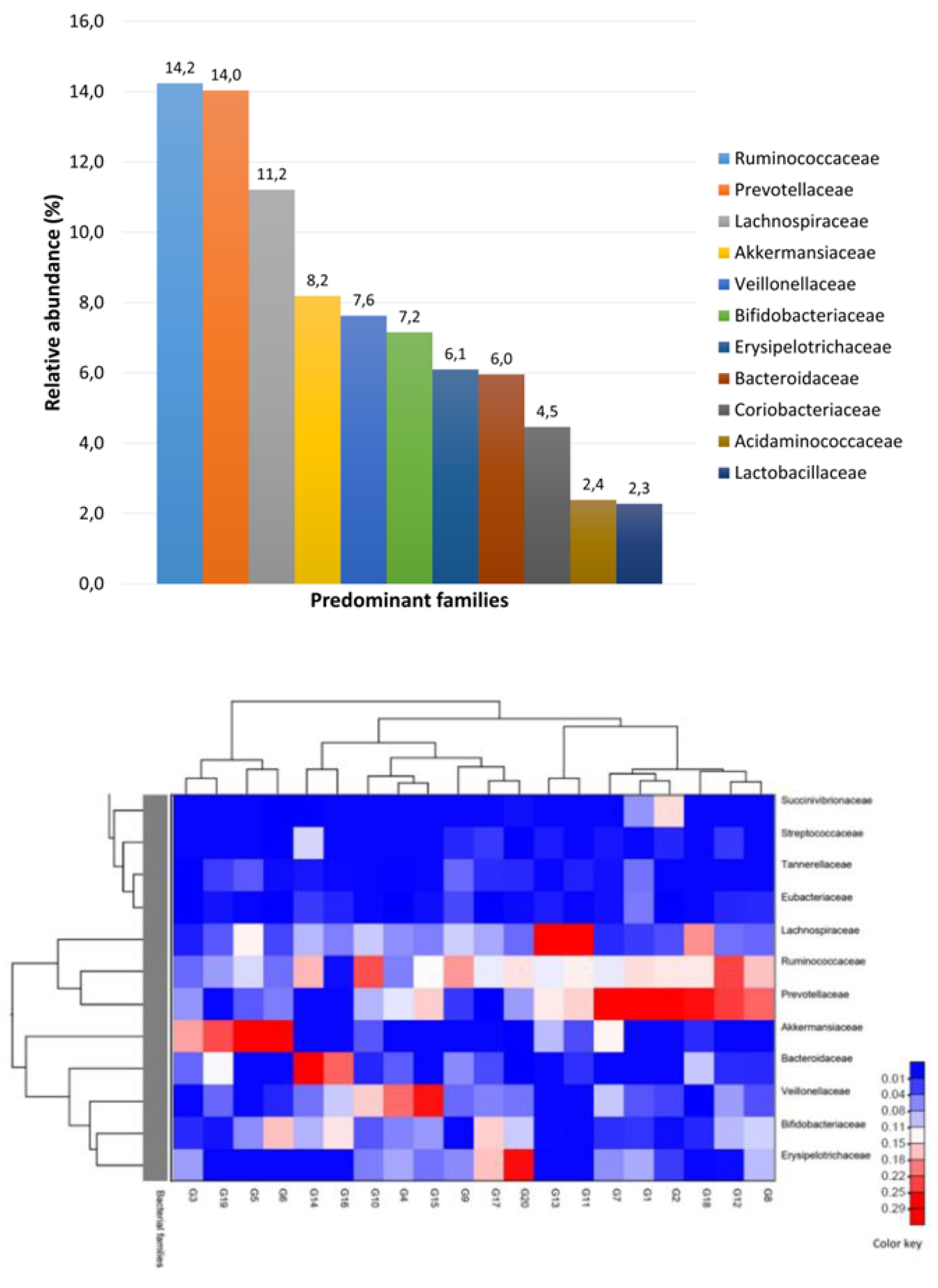

We identified 11 predominant bacterial families (

Figure 2a and 2b) in the fecal samples: Ruminococcaceae (mean relative abundance: 14.2%), Prevotellaceae (14.0%), Lachnospiraceae (11.2%), Akkermansiaceae (8.2%), Veillonellaceae (7.6%), Bifidobacteriaceae (7.2%), Erysipelotrichaceae (6.1%), Bacteroidaceae (6.0%), Coriobacteriaceae (4.5%), Acidaminococcaceae (2.4%), and Lactobacillaceae (2.3%). There were relatively high levels of Prevotella (mean relative abundance: 12.9%), Faecalibacterium (11.1%), and Akkermansia (7.6%) at the genus level. The Firmicutes phylum included bacterial species such as Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Clostridium, Eubacterium, Ruminiclostridium, Blautia, and Coprococcus in the fecal samples. We identified Bacteroides, Mediterranea, Barnesiella, Massiliprevotella, Prevotella, Prevotellamassilia, Alistipes, and Parabacteroides species in the Bacteroidetes phylum, which is the second most abundant phylum in the gut microbiota. Additionally, we detected Parasutterella, Sutterella, Succinivibrio, Escherichia, and Desulfovibrionaceae, which are species in the Proteobacteria phylum, and Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, and Eggerthella, which are species in the Actinobacteria phylum.

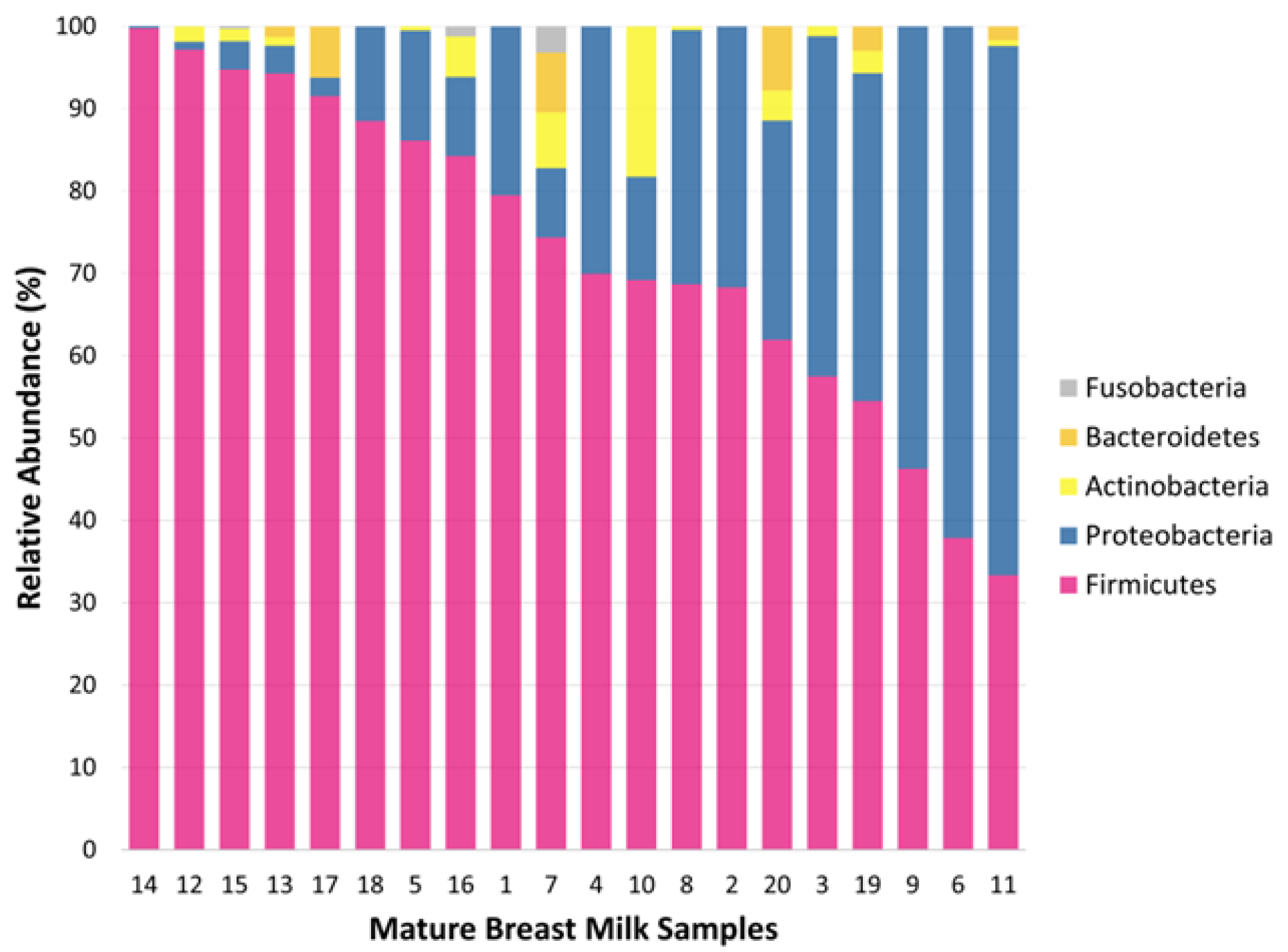

3.3. Microbiota Composition of Mature Breast Milk Samples

Figure 3 displays the phylum level of mature human milk. We identified a total of 5 phyla, 9 classes, 14 orders, 20 families, 21 genera, and 38 species in the mature milk samples of 20 healthy women again on the basis of next-generation sequencing reads representing the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The microbial composition of mature breast milk at the phylum level revealed that Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum (mean relative abundance: 72.8%), followed by Proteobacteria (24.1%). In addition, the phyla Actinobacteria (1.9%), Bacteroidetes (1.1%), and Fusobacteria (0.1%) were found, but they were present in small amounts in the samples from the breast milk microbiota.

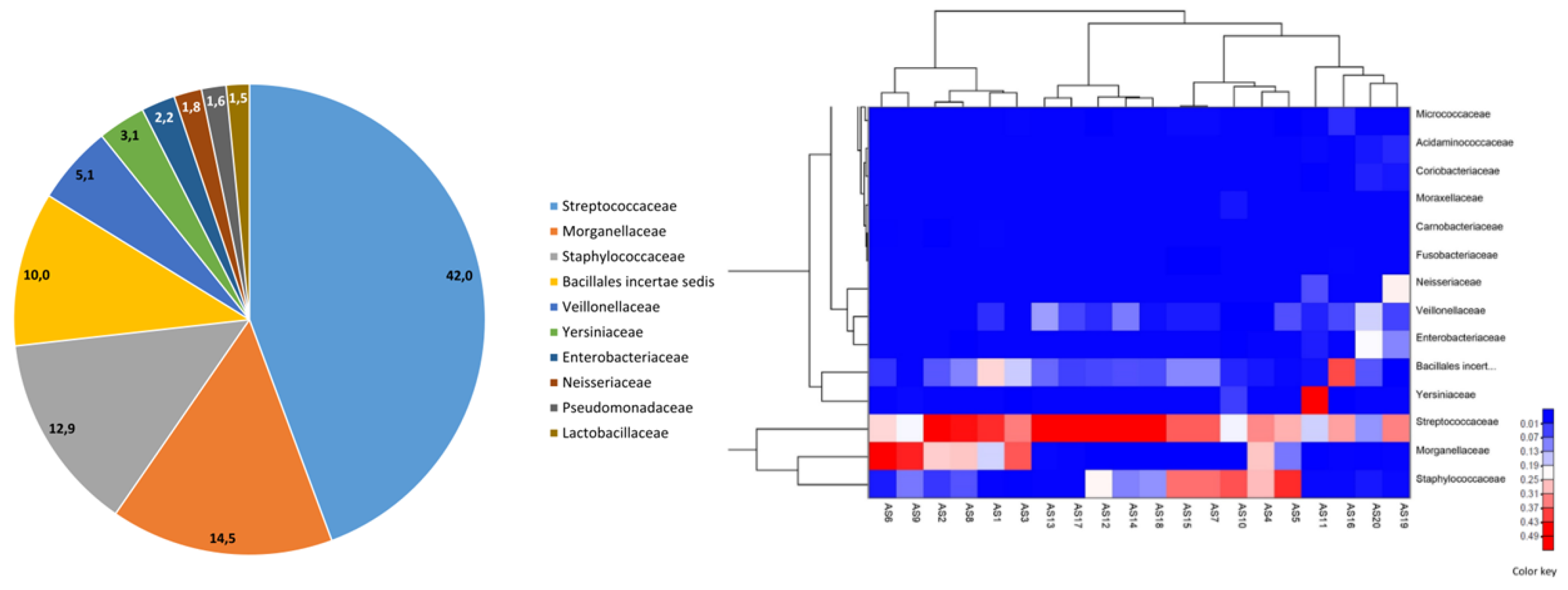

We identified 10 predominant families (

Figure 4a and 4b) in the mature breast milk samples including Streptococcaceae (mean relative abundance: 42.0%), Morganellaceae (14.5%), Staphylococcaceae (12.9%), Bacillales incertae sedis (10.0%), Veillonellaceae (5.1%), Yersiniaceae (3.1%), Enterobacteriaceae (2.2%), Neisseriaceae (1.8%), Pseudomonadaceae (1.6%), and Lactobacillaceae (1.5%). At the genus level, the most abundant taxa in the samples were Streptococcus (mean relative abundance: 2.1%), Proteus (0.7%), and Staphylococcus (0.6%). In the Firmicutes phylum, we determined the presence of eight genera, namely, Incertae sedis, Staphylococcus, Granulicatella, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Blautia, Phascolarctobacterium, and Veillonella, from the highest to the lowest concentrations. Proteobacteria phylum containing the second most abundant genera in the breast milk microbiota included Neisseria, Klebsiella, Proteus, Serratia, Yersinia, Haemophilus, Acinetobacter, and Pseudomonas on the basis of abundance.

3.4. Comparison of the Microbial Composition of the Maternal Fecal and Mature Breast Milk Samples

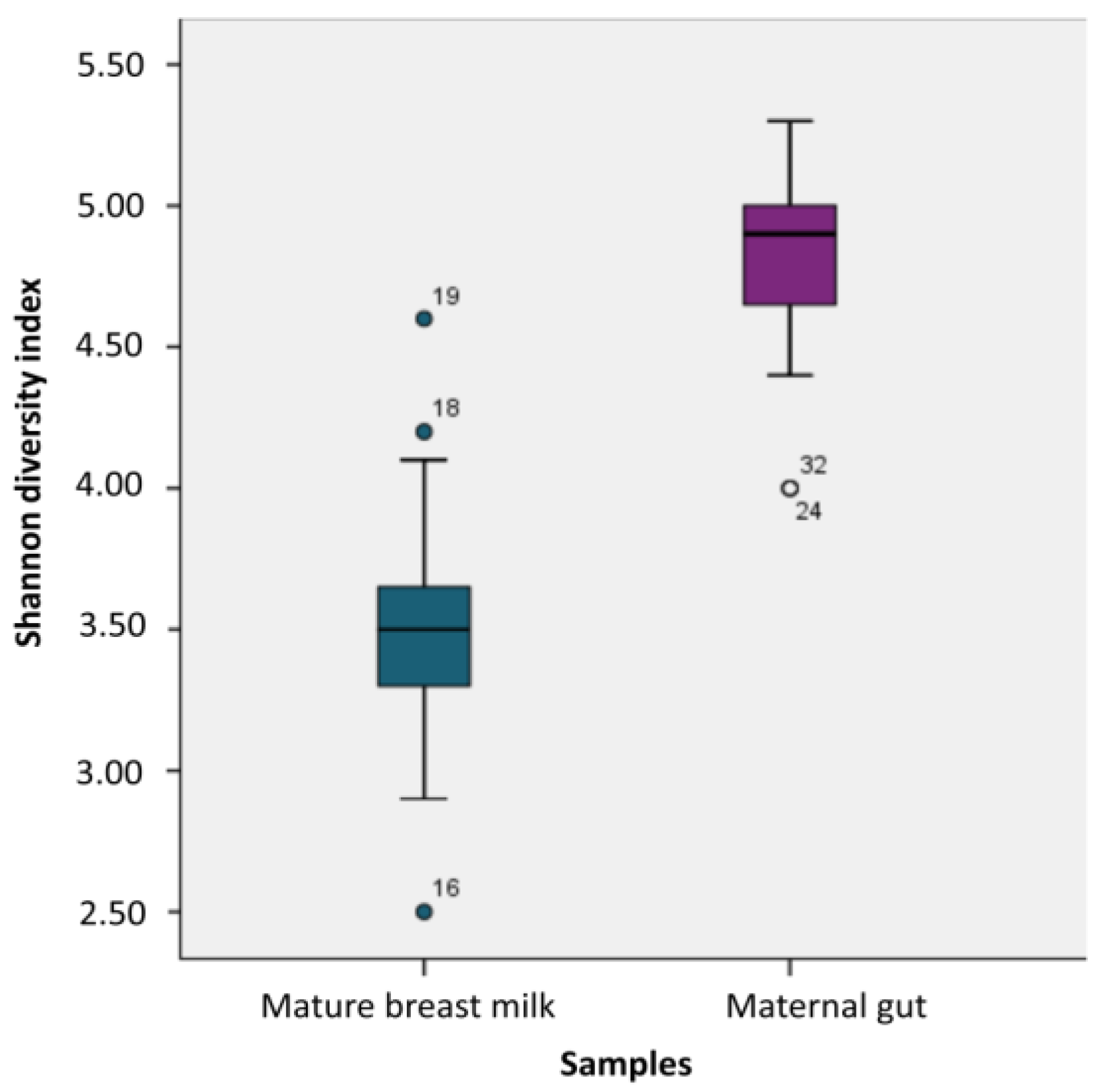

Figure 5 shows that the Shannon index was significantly lower in the breast milk samples than in the fecal samples during the postpartum period (p<0.001). We determined the presence of 5 bacterial phyla in both maternal fecal and mature breast milk samples. The abundances of Firmicutes (mean relative abundance: 72.8% vs. 50.2%, respectively) and Proteobacteria (24.1% vs. 3.0%, respectively) were significantly greater in samples from mature breast milk than in those from the maternal gut (p<0.001). However, there was a significantly higher abundance of Bacteroidetes (mean relative abundance: 24.2% vs. 1.1%, respectively) and Actinobacteria (11.9% vs. 1.9%, respectively) in the maternal fecal samples than in the mature breast milk samples (p<0.001). We used the Shannon index to estimate microbial diversity.

4. Discussion

Breast milk is crucial for the optimal growth and development of newborns. Demographic information, genetic factors, maternal lifestyle, and exposure affect the health of newborns by changing the components and microbiota composition of their breast milk [

22]. In the literature, studies have evaluated only the maternal gut microbiota according to gestational period, the breast milk microbiota according to lactation period, or comparisons of the microbiota between breast milk and the infant gut. In this study, we determined the microbiome composition of the maternal gut during postpartum and mature breast milk. Additionally, we compared the bacterial composition of the maternal gut and breast milk at the phylum level.

The maternal microbiome is one of the most crucial contributors to both the health of the mother-infant and the postpartum period. In a prospective study conducted with 47 healthy women, there was a relatively high abundance of Bifidobacterium (6.3%) and Eubacterium during the postpartum period [

16]. Additionally, they revealed that the maternal gut microbiota presented a slightly greater relative abundances of Streptococcus, Clostridium, and Enterococcus. Another study including 78 breastfeeding women reported a relatively high abundance of the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla in fecal samples from women [

23]. We revealed that in this Turkish mother cohort, the most abundant phyla in the maternal samples were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. The profiles of the bacterial families revealed that Ruminocococcaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Lanchnospiraceae were the three most abundant families in the fecal samples of healthy women, which was not consistent with previous findings.

In this study, we found that three phyla, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria, are dominant in mature breast milk. In line with our study, Padilha et al. [

24] reported that Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria were the most abundant phyla in breast milk samples (70.0%, 14.5%, and 14.0%, respectively). In other studies conducted to determine the breast milk microbiota, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes made up the highest proportion of phyla in all samples [

4,

25]. We identified a total of five phyla in the breast milk of healthy women. We determined that Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Proteus were the three most prevalent genera among the breast milk samples. In agreement with our study, Chen et al. [

26] reported that Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were the most abundant bacterial genera in the breast milk samples of healthy women. In a meta-analysis of 12 observational studies, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus were predominant in 6 of them without regard to differences in geographic location or analysis methods [

7]. Ge et al. revealed [

27] that Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria were the most abundant phyla in 20 mature human milk samples. Additionally, human milk is mainly composed mainly of Alcaligenaceae, Staphylococcaceae, Bacillaceae, Streptococcaceae and Gemellaceae at the family level.

Microbial changes during postpartum and early development can be related to metabolic changes [

28]. Therefore, determining the microbial colonization and diversity in the gut microbiota during the postpartum period is crucial [

29]. We found that the microbial diversity of the breast milk samples was significantly lower that of the fecal samples of from the breastfeeding women. The gut microbiota composition of women is altered during the postpartum period, and alpha diversity decreases while beta diversity increases among individuals [

30,

31].

5. Conclusions

We aimed to reveal the composition of the breast milk microbiome and the possible contribution of the gut microbiome to the breast milk microbiome in our study. At the end of this study, Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum in both mature breast milk and maternal gut samples. In this study, we present new information about the definition and especially the comparison of the maternal gut microbiota composition during postpartum and breast milk. Since studies comparing of breast milk and maternal gut microbiota are lacking, we believe that this study is a great preliminary study to understand the unknowns of this complex bacterial diversity. On the other hand, we are conscious of likely limitations in the present study. We collected breast milk samples only once and on the 16th day postpartum. Therefore, we were unable to detect alterations of bacteria during lactation. On the basis of findings of this study, we plan to investigate the effect of the dietary pattern of women during the postpartum period on both maternal and neonatal gut microbiota composition in our next study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.E.İ. and G.S.; methodology, G.E.İ. and G.S.; software, A.D.; validation, G.E.İ. and G.S. and G.E.İ.; formal analysis, G.E.İ; investigation, G.E.İ. and G.S.; resources, G.E.İ., G.S., K.E.K.; data curation, sample analyses, A.D., G.E.İ.; writing—original draft preparation, G.E.İ.; writing—review and editing, G.E.İ., G.S., K.E.K.; supervision, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Turkish Society of Clinical Enteral Parenteral Nutrition (KEPAN, Grant number 2019-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hacettepe Okan University (protocol GO 18/218-12 and 24 October 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| OTU |

Operational taxonomic units |

| PASS |

Power analysis and sample size |

References

- Keikha, M.; Bahreynian, M.; Saleki, M.; Kelishadi, R. Macro- and Micronutrients of Human Milk Composition: Are They Related to Maternal Diet? A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine 2017, 12, 517-527. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Giannì, M.L. Human milk: composition and health benefits. La Pediatria medica e chirurgica : Medical and surgical pediatrics 2017, 39, 155. [CrossRef]

- Lessen, R.; Kavanagh, K. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: promoting and supporting breastfeeding. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2015, 115, 444-449. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Curley, D.; O’Callaghan, T.F.; O’Shea, C.A.; Dempsey, E.M.; O’Toole, P.W.; Ross, R.P.; Ryan, C.A.; Stanton, C. The Composition of Human Milk and Infant Faecal Microbiota Over the First Three Months of Life: A Pilot Study. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 40597. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, E.; de Andrés, J.; Manrique, M.; Pareja-Tobes, P.; Tobes, R.; Martínez-Blanch, J.F.; Codoñer, F.M.; Ramón, D.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J.M. Metagenomic Analysis of Milk of Healthy and Mastitis-Suffering Women. Journal of human lactation : official journal of International Lactation Consultant Association 2015, 31, 406-415. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Breast milk microbiota: A complex microbiome with multiple impacts and conditioning factors. The Journal of infection 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fitzstevens, J.L.; Smith, K.C.; Hagadorn, J.I.; Caimano, M.J.; Matson, A.P.; Brownell, E.A. Systematic Review of the Human Milk Microbiota. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2017, 32, 354-364. [CrossRef]

- Jost, T.; Lacroix, C.; Braegger, C.P.; Rochat, F.; Chassard, C. Vertical mother-neonate transfer of maternal gut bacteria via breastfeeding. Environmental microbiology 2014, 16, 2891-2904. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M. The origin of human milk bacteria: is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation? Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 2014, 5, 779-784. [CrossRef]

- Jost, T.; Lacroix, C.; Braegger, C.; Chassard, C. Impact of human milk bacteria and oligosaccharides on neonatal gut microbiota establishment and gut health. Nutrition reviews 2015, 73, 426-437. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Palmer, D.J.; Geddes, D.; Lai, C.T.; Stinson, L. Human Milk Microbiome and Microbiome-Related Products: Potential Modulators of Infant Growth. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, C.; Cummins, J.; Brackstone, M.; Macklaim, J.M.; Gloor, G.B.; Baban, C.K.; Scott, L.; O’Hanlon, D.M.; Burton, J.P.; Francis, K.P.; et al. Microbiota of human breast tissue. Applied and environmental microbiology 2014, 80, 3007-3014. [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Henderson, W.A.; Graf, J.; McGrath, J.M. Early Life Experience and Gut Microbiome: The Brain-Gut-Microbiota Signaling System. Advances in neonatal care : official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses 2015, 15, 314-323; quiz E311-312. [CrossRef]

- Castanys-Muñoz, E.; Martin, M.J.; Vazquez, E. Building a Beneficial Microbiome from Birth. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 2016, 7, 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C. The development of human gut microbiota fermentation capacity during the first year of life. Microb Biotechnol 2022, 15, 2865-2874. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Yang, H. Distribution characteristics of intestinal microbiota during pregnancy and postpartum in healthy women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022, 35, 2915-2922. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health topics: Body mass index - BMI Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi (accessed on 07.05).

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. The ISME journal 2012, 6, 1621-1624. [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, e1. [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 852-857. [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare, S.V.; Patangia, D.V.; Mongad, D.S.; Bora, A.; Bavdekar, A.R.; Shouche, Y.S. Gut microbial diversity during pregnancy and early infancy: an exploratory study in the Indian population. FEMS microbiology letters 2020, 367. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.E.; Ryan, C.A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Breast Milk, a Source of Beneficial Microbes and Associated Benefits for Infant Health. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Butts, C.A.; Paturi, G.; Blatchford, P.; Bentley-Hewitt, K.L.; Hedderley, D.I.; Martell, S.; Dinnan, H.; Eady, S.L.; Wallace, A.J.; Glyn-Jones, S.; et al. Microbiota Composition of Breast Milk from Women of Different Ethnicity from the Manawatu-Wanganui Region of New Zealand. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Padilha, M.; Danneskiold-Samsøe, N.B.; Brejnrod, A.; Hoffmann, C.; Cabral, V.P.; Iaucci, J.M.; Sales, C.H.; Fisberg, R.M.; Cortez, R.V.; Brix, S.; et al. The Human Milk Microbiota is Modulated by Maternal Diet. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, C.; Angelini, M.; Gloor, G.B.; Reid, G. Human milk microbiota profiles in relation to birthing method, gestation and infant gender. Microbiome 2016, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Lin, Y.L.; Huang, M.S. Profiles of commensal and opportunistic bacteria in human milk from healthy donors in Taiwan. Journal of food and drug analysis 2018, 26, 1235-1244. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, J.; Shi, M. Human milk microbiota and oligosaccharides in colostrum and mature milk: comparison and correlation. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1512700. [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.; Skov, T.H.; Bahl, M.I.; Roager, H.M.; Christensen, L.B.; Ejlerskov, K.T.; Mølgaard, C.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Licht, T.R. Establishment of intestinal microbiota during early life: a longitudinal, explorative study of a large cohort of Danish infants. Applied and environmental microbiology 2014, 80, 2889-2900. [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare, S.V.; Patangia, D.V.V.; Patil, R.H.; Shouche, Y.S.; Patil, N.P. Factors influencing the gut microbiome in children: from infancy to childhood. Journal of biosciences 2019, 44.

- Mesa, M.D.; Loureiro, B.; Iglesia, I.; Fernandez Gonzalez, S.; Llurba Olivé, E.; García Algar, O.; Solana, M.J.; Cabero Perez, M.J.; Sainz, T.; Martinez, L.; et al. The Evolving Microbiome from Pregnancy to Early Infancy: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Weerasuriya, W.; Saunders, J.E.; Markel, L.; Ho, T.T.B.; Xu, K.; Lemas, D.J.; Groer, M.W.; Louis-Jacques, A.F. Maternal gut microbiota in the postpartum Period: A Systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2023, 285, 130-147. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).