Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

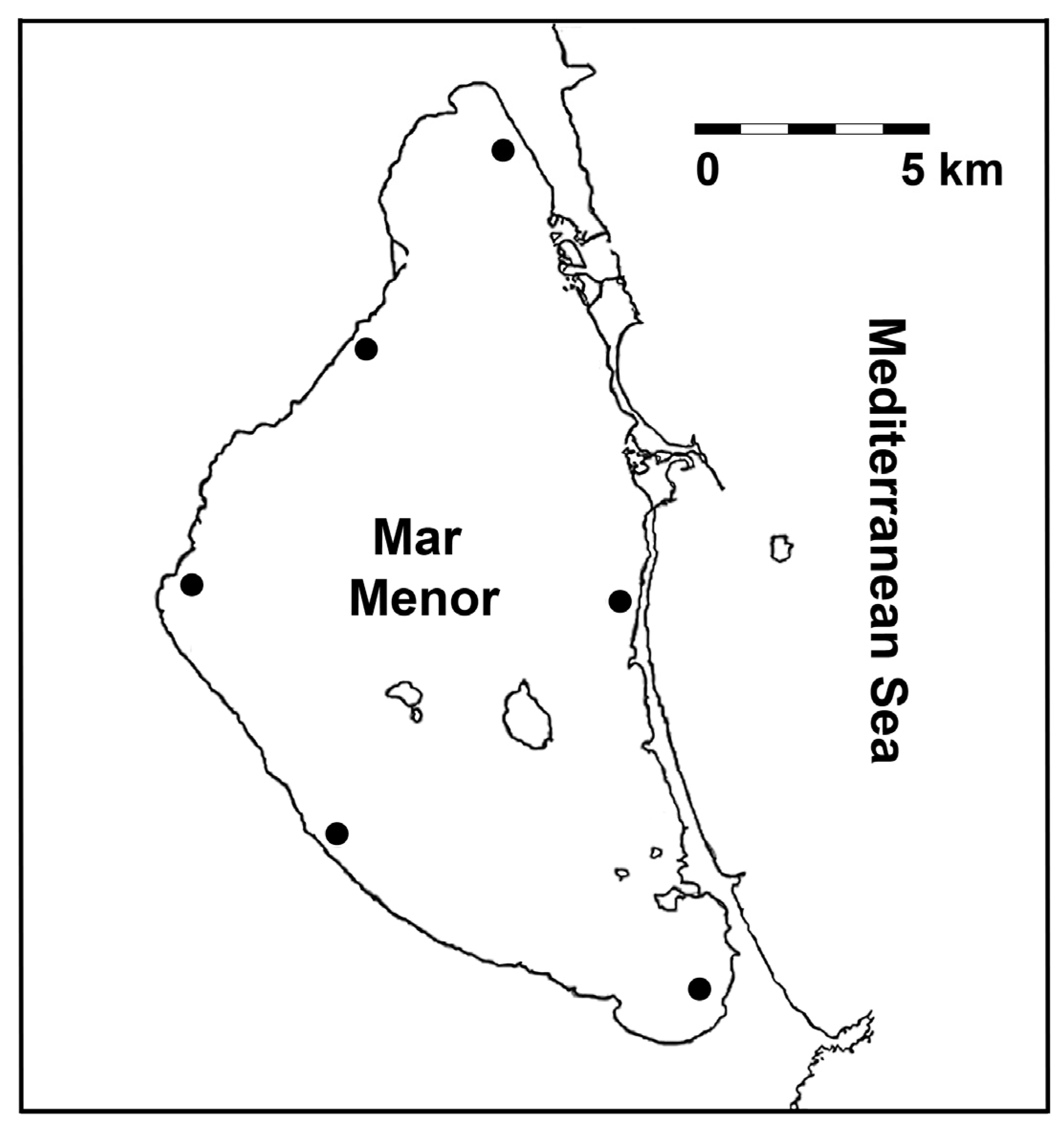

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling

2.3. Morphological Examination

2.4. Parasitological Examination

2.5. Genetic Analyses

2.6. Data Analyses

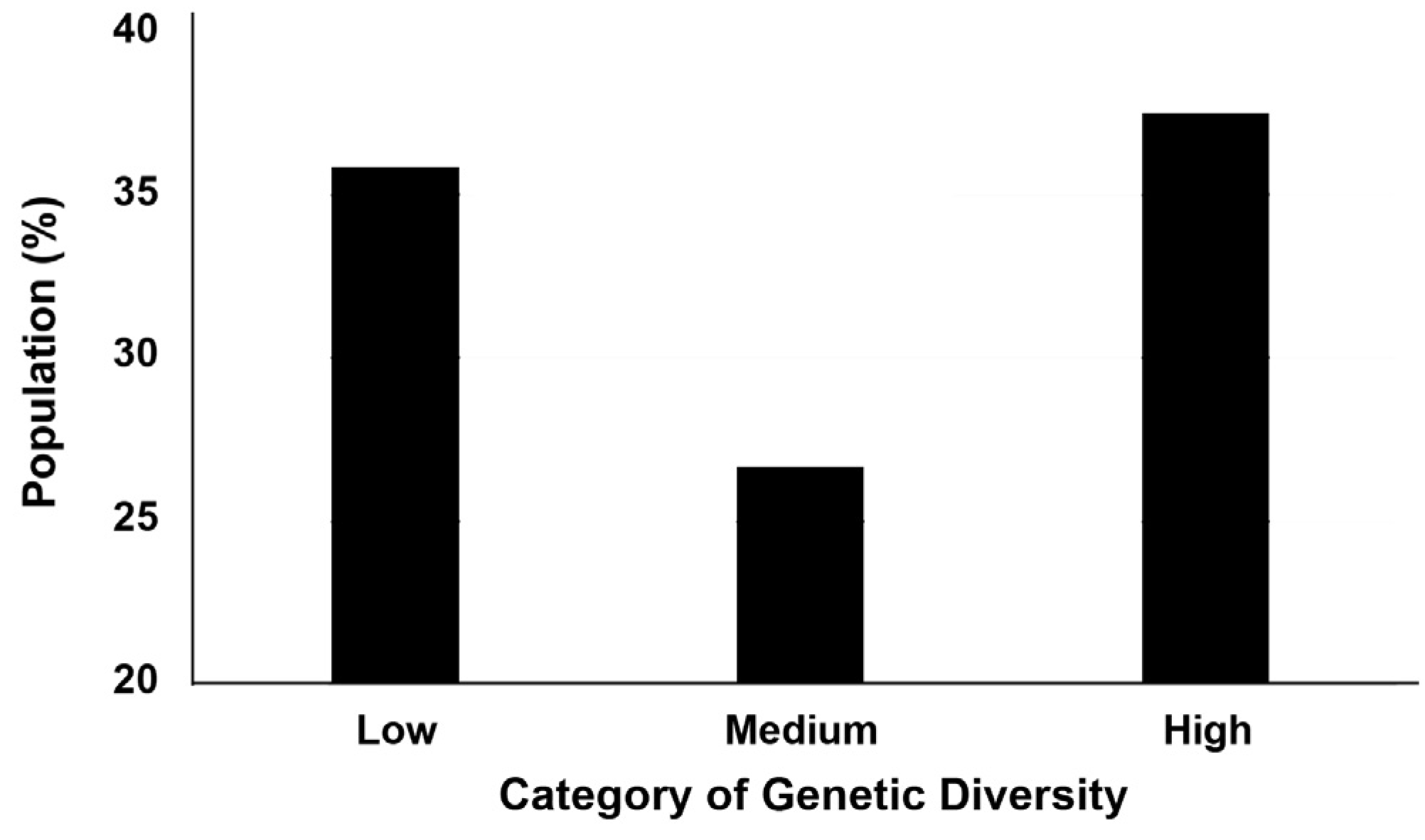

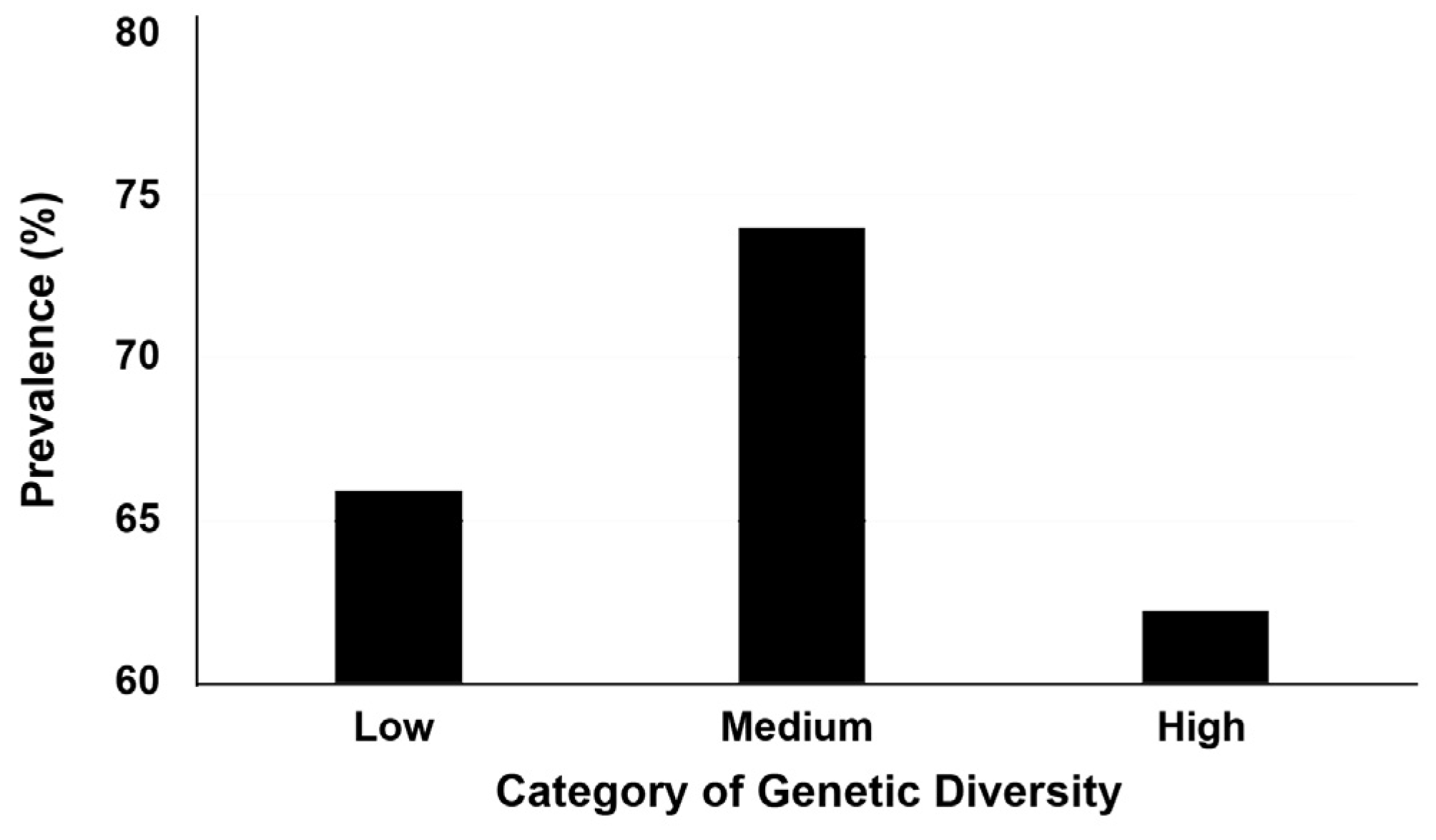

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coen, L.D.; Melanie, J.B. The ecology, evolution, impacts and management of host-parasite interactions of marine molluscs. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 131, 177–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.F. Complex networks of parasites and pollinators: Moving towards a healthy balance. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2022, 377, 20210161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, R.; Eibner, G.J.; Schwensow, N.I.; Pirzer, F.; Paraskevopoulou, S.; Mayer, G.; Corman, V.M.; Drosten, C.; Wilhelm, K.; Heni, A.C.; et al. Immunogenetic-pathogen networks shrink in Tome’s spiny rat, a generalist rodent inhabiting disturbed landscapes. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longshaw, M.; Frear, P.A.; Nunn, A.D.; Cowx, I.G.; Feist, S.W. The influence of parasitism on fish population success. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2010, 17, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutermann, H.; Butler, K.B.; Bennett, N.C. Parasite-mediated mate preferences in a cooperatively breeding rodent. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 838076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriolli, F.S.; Cardoso Neto, J.A; Fine, P.V.A.; Salazar, D.; Figueroa, G.; Torres, D.V.; de Morais, J.W.; Baccaro, F.B. When zombies go vegan: Ophiocordyceps unilateralis hosts are selecting to bite palm leaves before dying? Acta Oecol. 2025, 126, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanellas-Reboredo, M.; Vázquez-Luis, M.; Mourre, B. Tracking a mass mortality outbreak of pen shell Pinna nobilis populations: A collaborative effort of scientists and citizens. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.O.; Fernández, J.C. ; Esch, G; Seed, R. Parasitism: The Diversity and Ecology of Animal Parasites, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.M.; Brown, A.M.; Goede, R.W. A quantitative health assessment index for rapid evaluation of fish conditions in the field. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1993, 122, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krist, A.C.; Jokela, J.; Wiehn, J.; Lively, C.M. Effects of host condition on susceptibility to infection, parasite developmental rate, and parasite transmission in a snail-trematode interaction. J. Evol. Biol. 2004, 17, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschirren, B.; Bischoff, L.L.; Saladin, V.; Richner, H. Host condition and host immunity affect parasite fitness in a bird-ectoparasite system. Funct. Ecol. 2007, 21, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmlund, C.M; Hammer, M. Ecosystem services generated by fish populations. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.H.; Jones, A. Parasitic Worms of Fish, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Ltd: London, UK, 1994; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb, T.H.; Bray, R.A.; Littlewood, D.T.J. The nature and evolution of the association among digeneans, molluscs and fishes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcogliese, D.J. Parasites of the superorganism: Are they indicators of ecosystem health? Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimková, A. Host-specific monogeneans parasitizing freshwater fish: The ecology and evolution of host-parasite associations. Parasite 2024, 31, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrock, M.; Marcogliese, D.J. Free-living endohelminth stages: At the mercy of environmental conditions. Trends Parasitol. 2003, 19, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, K.D. Ecosystem consequences of fish parasites. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Sánchez, A.; Wilber, M.Q.; Canessa, S.; Bacigalupe, L.D.; Muths, E.; Schmidt, B.R.; Cunningham, A.A.; Ozgul, A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Cayuela, H. Why disease ecology needs life-history theory: A host perspective. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, L.J.; Ashby, B. Coevolutionary theory of hosts and parasites. J. Evol. Biol. 2002, 35, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Råberg, L.; Sim, D.; Read, A.F. Disentangling genetic variation for resistance and tolerance to infectious diseases in animals. Science 2007, 318, 812–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.E.; Estensoro, I.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A.; Bartholomew, J.L. Intestinal transcriptomic and histologic profiling reveals tissue repair mechanisms underlying resistance to the parasite Ceratonova shasta. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, J.A. Natural Selection in the Wild, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Coltman, D.W.; Pilkington, J.G.; Smith, J.A.; Pemberton, J.M. Parasite-mediated selection against inbred soay sheep in a free-living island population. Evolution 1999, 53, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zueva, K.J.; Lumme, J.; Veselov, A.E.; Kent, M.P.; Lien, S. Footprints of directional selection in wild Atlantic salmon populations: Evidence for parasite-driven evolution? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, S.; Rey, O.; Berthier, P.; Lek, S.; Loot, G. Evidence of parasite-mediated disruptive selection on genetic diversity in a wild fish population. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 1112–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, S.; Rey, O.; Loot, G. Evidence for host variation in parasite tolerance in a wild fish population. Evol. Ecol. 2010, 24, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in Action; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, H.E.; Couture, J.; Falconer, L.; Krause, G.; Morris, J.A.; Perez, M.; Stentiford, G.D.; Vehviläinen, H.; Halpern, B.S. Mind the gap between ICES nations’ future seafood consumption and aquaculture production. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2001, 78, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H. Genetics and genomics of infectious diseases in key aquaculture species. Biology 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timi, J.T.; Buchmann, K. A century of parasitology in fisheries and aquaculture. J. Helminthol. 2023, 97, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Stauffer, J.R. Aquaculture of animal species: Their eukaryotic parasites and the control of parasitic infections. Biology 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjedrem, T.; Rye, M. Selection response in fish and shellfish: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennish, M.J.; Paerl, H.W. Coastal Lagoons. Critical Habitats of Environmental Change, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, M.; Whitfield, A.K. Challenging paradigms in estuarine ecology and management. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2011, 94, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giari, L.; Castaldelli, G.; Timi, J.T. Ecology and effects of metazoan parasites of fish in transitional waters. Parasitology 2022, 149, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, D.; Cruz, A.; Llinares, C.; Torralva, M.; Lantero, E.; Fletcher, D.H.; Oliva-Paterna, F.J. Fish morphological and parasitological traits as ecological indicator of habitat quality in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2023, 33, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Fernández-Boo, S.; Magalhães, L.; de Montaudouin, X.; Daffe, G.; Poulin, R.; Vera, M. Trematode genetic patterns at host individual and population scales provide insights about infection mechanisms. Parasitology 2023, 150, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjallah, S.; Amor, N.; Montero, F.E.; Repullés-Albelda, A.; Villar-Torres, M.; Nasser Alagaili, A.; Merella, P. Assessment of the genetic diversity of the monogenean gill parasite Lamellodiscus echeneis (Monogenea) infecting wild and cage-reared populations of Sparus aurata (Teleostei) from the Mediterranean Sea. Animals 2024, 14, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITECO. Available online: https://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Oliva-Paterna, F.J.; Andreu, A. , Miñano, P.A.; Verdiell, D.; Egea, A.; De Maya, J.A.; Ruiz-Navarro, A.; García-Alonso, J.; Fernández-Delgado, C.; Torralva, M. Y-O-Y fish species richness in the littoral shallows of the meso-saline coastal lagoon (Mar Menor, Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Gómez, A.; Zamora-López, A.; Guillén-Beltrán, A.; Zamora-Marín, J.M.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Torralva, M.; Oliva-Paterna, F.J. An updated checklist of YOY fish occurrence in the shallow perimetral areas of the Mar Menor (Western Mediterranean Sea). Limnetica 2022, 41, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzoni, M.; Gaglio, M.; Gavioli, A.; Fano, E.A.; Castaldelli, G. Seasonal variation of functional traits in the fish community in a brackish lagoon of the Po River Delta (Northern Italy). Water 2021, 13, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Directive 2014/101/EU of 30 October 2014 amending Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Union-Legislation 2014, 311, 32–35. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/101/oj (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ford, M. 2024. Syngnathus abaster. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T21257A135092980. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T21257A135092980.en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Doadrio, I.; Perea, S.; Garzón-Heydt, P.; González, J.L. Ictiofauna Continental Española. Bases para su Seguimiento (in Spanish); DG Medio Natural y Política Forestal, Ministry of Environment: Madrid, Spain, 2011; p. 612. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, D.; Alcaraz-Hernández, J.D.; Cruz, A.; Lantero, E.; Fletcher, D.H.; García-Berthou, E. Seasonal effects on health status and parasitological traits of an invasive minnow in Iberian Waters. Animals 2024, 14, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näslund, J.; Johnsson, J.I. Environmental enrichment for fish in captive environments: Effects of physical structures and substrates. Fish. Fish. 2016, 17, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.M.; Marcogliese, D.J.; Suski, C.D.; Cooke, S.J. Variation in parasite communities and health indices of juvenile Lepomis gibbosus across a gradient of watershed land-use and habitat quality. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 57, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, D.; Masó, G.; Hinckley, A.; Verdiell-Cubedo, D.; Castillo-García, G.; González-Rojas, A.G.; Black-Barbour, E.N.; Vila-Gispert, A.; García-Berthou, E.; Miranda, R.; et al. Interpopulation variability in dietary traits of invasive bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) across the Iberian Peninsula. Water 2020, 12, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, E.M.; Marshall, S.D.; Uetz, G.W. Estimating fitness: A comparison of body condition indices. Oikos 1996, 77, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Berthou, E. On the misuse of residuals in ecology: Testing regression residuals vs. the analysis of covariance. J. Anim. Ecol. 2001, 70, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Llinares, C.; Martín-Barrio, I.; Castillo-García, G.; Arana, P.; García-Berthou, E.; Fletcher, D.H.; Almeida, D. Comparing morphological, parasitological and genetic traits of an invasive minnow between intermittent and perennial stream reaches. Freshw. Biol. 2022, 67, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.P.; Govett, P. Parasitology and necropsy of fish. Compend. Contin. Educ. Vet. 2009, 31, E12. [Google Scholar]

- Stoskopf, M.K. Fish Medicine, 2nd ed.; Saunders Ltd.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; p. 882. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, B. Aquatic Parasite Information - A Database on Parasites of Freshwater and Brackish Fish in the United Kingdom. PhD Thesis, Kingston University, London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, D.; Nowak, B.F.; Elliot, D. Guide to the identification of fish protozoan and metazoan parasites in stained tissue sections. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2006, 70, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falaise, P. Les Parasites de Poisson: Agents de Zoonoses (in French). PhD Thesis, University of Toulouse, Toulouse, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, B.; Yasen, M.; Boyko, B. Helminth parasites of black-striped pipefish Syngnathus abaster Risso, 1827 (Actinopterygii: Syngnathidae) from a Black Sea coastal wetland, Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2024, 76, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ondračková, M.; Slováčková, I.; Trichkova, T.; Polačik, M.; Jurajda, P. Shoreline distribution and parasite infection of black-striped pipefish Syngnathus abaster Risso, 1827 in the lower River Danube. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012, 28, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/species/search (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ondračková, M.; Bartáková, V.; Kvach, Y.; Bryjová, A.; Trichkova, T.; Ribeiro, F.; Carassou, L.; Martens, A.; Masson, G.; Zechmeister, T.; Jurajda, P. Parasite infection reflects host genetic diversity among non-native populations of pumpkinseed sunfish in Europe. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2169–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, S.M.; Martinez, I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high-quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucl. Acids. Res. 1997, 25, 4692–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekmann, O.E.; Gouveia, L.; Serrão, E.A.; Van de Vilet, M.S. Highly polymorphic microsatellite markers for the black striped pipefish, Syngnathus abaster. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.G.; Rosenqvist, G.; Berglund, A.; Avise, J.C. The genetic mating system of a sex-role-reversed pipefish (Syngnathus typhle): A molecular inquiry. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1999, 46, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.C.D.; Barry, S.J.E.; Ferguson, H.M.; Müller, P. Power analysis for generalized linear mixed models in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, W.; Wilmer, J.W.; Fullard, K.; Burg, T.M.; Croxall, J.P.; Bloch, D.; Coulson, T. The influence of parental relatedness on reproductive success. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.M.; Ortego, J.; Cordero, P.J. What should we weigh to estimate heterozygosity, alleles or loci? Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 4659–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.R.; Nakagawa, S.; Coltman, D.W.; Slate, J.; Sheldon, B.C. A quantitative review of heterozygosity-fitness correlations in animal populations. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 2746–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, G.C.; Boardman, T.J. The use of percentages and size-specific indices to normalize physiological data for variation in body size: Wasted time, wasted effort? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 1999, 122, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/. (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Rueffler, C.; Van Dooren, T.J.M.; Leimar, O.; Abrams, P.A. Disruptive selection and then what? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A. Host-parasite interactions in some fish species. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 237280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krkosek, M.; Revie, C.W.; Gargan, P.G.; Skilbrei, O.T.; Finstad, B.; Todd, C.D. Impact of parasites on salmon recruitment in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortego, J.; Aparicio, J.M.; Calabuig, G.; Cordero, P.J. Risk of ectoparasitism and genetic diversity in a wild lesser kestrel population. Mol Ecol. 2007, 16, 3712–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.A.; Neff, B.D. Parasite mediated homogenizing selection at the MHC in guppies. Genetica 2010, 138, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, H.S.; Cano, J.M.; Merilä, J. Identifying footprints of directional and balancing selection in marine and freshwater three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) populations. Mol Ecol. 2008, 17, 3565–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, P.W. Balancing selection. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 230–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Fernández, J.; Castejón-Silvo, I.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Terrados, J.; Morales-Nin, B. Feeding ecology of pipefish species inhabiting Mediterranean seagrasses. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2020, 21, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Morkune, R.; Marcos, C.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.; Razinkovas-Baziukas, A. Can an oligotrophic coastal lagoon support high biological productivity? Sources and pathways of primary production. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 153, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert, J. Seasonal plankton dynamics in a Mediterranean hypersaline coastal lagoon: The Mar Menor. J. Plankton Res. 2001, 23, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, S.W.; Longshaw, M. Histopathology of fish parasite infections – importance for populations. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Pellitero, P. Fish immunity and parasite infections: From innate immunity to immunoprophylactic prospects. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 126, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazzon, M.C.; Galindo-Villegas, J.; Pereiro, P.; Estensoro, I.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Gómez-Casado, E.; Novoa, B.; Mulero, V.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Differential modulation of IgT and IgM upon parasitic, bacterial, viral, and dietary challenges in a perciform fish. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, A.S.; Piazzon, M.C.; Barrett, D.; Bartholomew, J.L.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A. To react or not to react: The dilemma of fish immune systems facing Myxozoan Infections. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 734238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, C.; Lenz, T.L. Major histocompatibility complex polymorphism: Dynamics and consequences of parasite-mediated local adaptation in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 2023–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daub, J.T.; Hofer, T.; Cutivet, E.; Dupanloup, I.; Quintana-Murci, L.; Robinson-Rechavi, M.; Excoffier, L. Evidence for polygenic adaptation to pathogens in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1544–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, L.H; Goldberg, M.L.; Fischer, J.A.; Hood, L.; Aquadro, C.F. Genetics: From genes to genomes, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 816. [Google Scholar]

- Spiering, A.E.; de Vries, T.J. Why females do better: The X chromosomal TLR7 gene-dose effect in COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 756262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakova, T.A.; Kornyychuk, Y.M.; Pronkina, N.V. Checklist of Syngnathidae parasites in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Inland Water Biol. 2023, 16, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornyychuk, Y.; Anufriieva, E.; Shadrin, N. Diversity of parasitic animals in hypersaline waters: A review. Diversity 2023, 15, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, S.A.; Overstreet, R.M. Digeneans as enemies of fishes. In Fish Diseases, 1st ed.; Eiras, J., Segner, H., Wahli, T., Kapoor, B.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 817–976. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós-Celdrán, P.; Robledano-Aymerich, F.; Carreño, M.F.; Martínez-López, J. Spatiotemporal assessment of littoral waterbirds for establishing ecological indicators of Mediterranean coastal lagoons. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Franzoi, P.; Malavasi, S.; Riccato, F.; Torricelli, P.; Mainardi, D. Use of shallow water habitats by fish assemblages in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Estuar. Coas. Shelf Sci. 2006, 66, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, D.; Blight, L.K.; Caldwell, I.R.; Vincent, A.C.J. The importance of seahorses and pipefishes in the diet of marine animals. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries 2011, 21, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, I. The role of parasites in fish-bird interactions: A behavioural ecological perspective. In Interactions between Fish and Birds: Implications for Management, 1st ed.; Cowx, I.G., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S. Parasite loss or parasite gain? Story of Contracaecum nematodes in antipodean waters. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2019, 4, e00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.A.; Brassil, C.E.; Hall, S.R.; Tessier, A.J.; Cáceres, C.E.; Conner, J.K. Parasite-mediated disruptive selection in a natural Daphnia population. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, K.M.; Kalbe, M.; Kurtz, J.; Reusch, T.B.H.; Milinski, M. Parasite selection for immunogenetic optimality. Science 2003, 301, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| locus (GenBank ID) | Primers 5’–3’ | Size | NA | Core Motif | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabas1 (GQ168557) | F-FAM: GGCATGTATCAAACGAATGTCCTC | 147–451 | 28 | (ATCT)32 | [64] |

| R: TTTGCGAAACAGTGTATGACTATACTT | |||||

| Sabas2 (GQ168558) | F-ATTO565: CAGGTTGTTGACCATTTGAGTGT | 170–262 | 11 | (TC)33 | [64] |

| R: CGAATATGATTATGTGAGTCCTAAGGC | |||||

| Sabas3 (GQ168559) | F: TTCCCCCTAGGACCAATAAAGTATCT | 149–279 | 21 | (ATCT)37 | [64] |

| R-Bodipy530: TGAGAGTGGTTGCCTCCAGC | |||||

| Sabas4 (GQ168560) | F: CAAAATGCAAGTGATCCTGTGTAGG | 207–298 | 27 | (TCTA) 38 | [64] |

| R-ATTO550: TGGTGTGGTGGAACTGAATGACG | |||||

| Sabas5 (GQ168561) | F: CATTGAAACTGCATTGATTTTATGATT | 249–360 | 29 | (ATCT)44 | [64] |

| R-FAM: AGGGGGTTGTAAGTCTTTGTG | |||||

| Sabas6 (GQ168562) | F-ATTO565: TCGTGTTCCGGGACGCACATGG | 244–451 | 35 | (AGAT)4CTAT(ATCT)31 | [64] |

| R: ATGTCCGAGGTCAAACACGGCGA | |||||

| Sabas7 (GQ168563) | F-Bodipy530: CGATGTGCGAGACCTGTTGCG | 184–322 | 24 | (GATA)33 | [64] |

| R: AAAGAGGCGGAGCTTGTGTAAGGA | |||||

| Sabas8 (GQ168564) | F: FAM-TATGTGTGCCCTGCGACTGGTTGR: CAGGAGATAAGGGAGCGTTTATAGCGG | 187–522 | 31 | (TAGA)42 | [64] |

| Sabas9 (GQ168565) | F: TGATTTGGAATGACACGGGTGGTTTG | 200–276 | 17 | (ATAG)33 | [64] |

| R-FAM: TCGTTTTGTGTGCACCGAGTGTT | |||||

| typh16 (–) | F-ATTO565: CAGGACACGCTGGAAAGAC | 223–307 | 20 | (GATG)15 | [65] |

| R: GCAACACCTTGAAGAGGAAAGT |

| S. abaster | Low | Medium | High | F2,356 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC (mg) | 411.5 ± 200.90 | 314.1 ± 190.85 | 402.5 ± 211.62 | 2.36 | 0.095 |

| HAI (points) | 24.2 ± 13.16 | a 35.3 ± 14.07 | 25.4 ± 15.55 | 4.95 | 0.008 |

| Parasite (Taxon) | Parasite (Family/Genus/Species) | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciliophora | Trichodina partidisci | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Cestoda | Proteocephalus sp. | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Monogenea | Gyrodactylus sp. | 2.2 | 0.6 | 2.9 |

| Digenea | Cryptocotyle concava | 1.5 | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| Cyathocotylidae | 3.8 | 7.3 | 4.4 | |

| Diplostomum sp. | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.5 | |

| Echinochasmus perfoliatus | – | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Podocotyle atherinae | 2.7 | 3.9 | 2.5 | |

| Timoniella imbutiformis | 0.9 | 1.7 | – | |

| Nematoda | Contracaecum microcephalum | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Acanthocephala | Paracanthocephaloides incrassatus | – | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Pomphorhynchus laevis | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |

| Crustacea | Ergasilus ponticus | 2.9 | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| S. abaster | Low | Medium | High | F2,236 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA (number of specimens) | 17.7 ± 8.68 | 22.9 ± 9.37 | 18.5 ± 8.36 | 2.59 | 0.077 |

| LCI (range: 1–3 host species) | 1.57 ± 0.685 | a 1.99 ± 0.701 | 1.56 ± 0.806 | 3.92 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).