1. Introduction

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are an emerging class of photovoltaic solar cells, in which materials known as perovskites are used as an active absorption layer. These materials have a unique crystal structure of the form ABX₃, where the A-site is occupied by larger cations, which can be organic molecules such as formamidinium or inorganic ions such as Cs [

1]. The B-site is typically filled with a metal cation, such as lead or tin, while the X-site is filled with a halide ion such as iodine. This distinctive crystal arrangement gives perovskites their remarkable electronic and optical properties, such as high light absorption, fast charge-carrier mobility, and adjustable band gaps. Thus far, PSCs have shown outstanding improvement in their power conversion efficiency, with some laboratory prototypes even outperforming traditional silicon-based solar cells. Furthermore, their high efficiency presents a unique opportunity for large-scale and cost-effective manufacturing.

There is a wide range of PSCs based on different perovskite materials. Lead-based perovskite solar cells have been the most promising, achieving power conversion efficiency (PCE) of up to more than 25 % in a laboratory environment [

2]. In fact, they are still an active area of research and have been showing improvement in various aspects in numerous computational and experimental studies (see Refs. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] and references therein). For instance, the recent study of Ref. [

3] investigated formamidinium lead iodide-based PSC using GPVDM software and obtained an improved PCE of 27.49%, which was also significantly higher than the PCE of the lead-free formamidinium tin iodide PSC that was also explored in the same study. Ref. [

4] studied the CsPbX3-based perovskite solar cells using density functional theory (DFT) and SCAPS-1D (Solar Cell Capacitance Simulator) software and found CsPbIBr2 having the best balance between stability and band-gap, and yielding the maximum PCE of 16.53 %. In the same vein, Ref. [

5] investigated HTM (hole transport material) free CsPbI3/CsSnI3 heterojunction solar cells, using the SCAPS-1D simulation tool, and achieved the PCE of up to 19.99%. Similarly, in the work of Ref. [

6], the thickness optimization engineering of the electron transport, hole transport, and perovskite layers of MAPbI3-based PSC was performed using the SCAPS-1D simulation package. The study revealed the necessity to increase the layer thickness by 50 to 100%, and the improvement of the PCE by 1.5%, achieving the PCE of 22.10 %. Furthermore, in the study of Ref. [

7], the CsPbI3, FAPbI3, MAPbI3, and FAMAPbI3 PSCs were analyzed and optimized using SCAPS-1D and results yielded the highest PCE of 26.35 % observed on the FAMAPbI

3 -based perovskite solar cell. In the same interest, Ref. [

8] conducted a numerical study on the CsPb.625Zn.375IBr

2-based perovskite solar cells by optimizing the density of charge carriers, the density of defects, and thicknesses of the electron transport layer (ETL), hole transport layer (HTL), active absorption layer. This yielded a PCE of 21.05 % for the optimized structure. Furthermore, Ref. [

9] performed a computational study of various perovskite solar cells, offering a detailed investigation of the impact of critical properties, such as band gap, electron affinity, layer thickness, absorption, recombination rate, band alignment, and defects, on the performance, and thus, achieving the highest PCE of 22.05% for the FAPbI

3-based device. Ref. [

10], investigated the effect of incorporating an interfacial layer of BiI

3 in MAPbI

3 and MAGeI

3-based perovskite solar cells and improved the PCE from 19.28 to 20.30% for MAPbI

3 PSC.

Even though lead-based PSCs are such a highly promising improvement in the photovoltaic industry, they have tremendous drawbacks. In particular, lead is a very toxic element that poses health risks to the manufacturers and consumers of lead-based perovskite solar cells. Thus, a lot of computational and experimental research is currently devoted to the development and optimization of lead-free perovskite solar cells [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. One of such lead-free PSCs is the KSnI

3-based device which is the subject of interest in the present study. This has recently attracted enormous interest, globally, due to its promising PCE, as well as the thermal and mechanical stability of KSnI

3 perovskite material, making it ideal for usage as the active absorption layer in various PSC configurations [

23]. In particular, Ref. [

23] studied the structural, mechanical, and optical properties of KSnI

3 using DFT, demonstrating its mechanical and thermal stability, and investigated its potential usage as the active absorption layer in perovskite solar cells using SCAPS-1D, and obtained the highest PCE of 9.776 % on the FTO/TiO

2/KSnI

3/Spiro-OMeTAD/W device. In the study of Ref. [

24], the impact of organic charge transport layers was explored, and critical parameters such as dopant density, thickness, and defect density were optimized, yielding the highest PCE of 10.83 % for FTO/C

60/KSnI

3/PTAA/C structure. In the same vein, the theoretical study of Ref. [

25] investigated the impact of metal phthalocyanines charge transport layers on KSnI

3-based perovskite solar cells and obtained the optimized FTO/F

16CuPc/KSnI

3/CuPc/C architecture with PCE of 11.91 %. Another computational study was done by Ref. [

26] using SCAPS-1D, exploring the effect of charge transport materials on the KSnI

3-based PSC, and achieved the PCE of 9.28 % on the FTO/ZnOS/KSnI

3/NiO/C configuration. Furthermore, the computational study of Ref. [

27] made significant progress on the optimization of KSnI

3 perovskite solar cells by achieving the PCE of 20.99 % for the FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/CuI/Au configuration, through the optimization of the hole transport layer, electron transport layer, anode material, defect and dopant densities. In the same interest, the very recent work Ref. [

28] studied KSnI

3 PSCs perovskite solar cells by optimization charge transport layers and incorporating the buffer layer, and obtained the highest PCE of 22.78 %, for the optimized FTO/SnO

2/3C–SiC/KSnI

3/NiO/C structure, which is currently the highest performance ever achieved on KSnI

3-based PSCs. On the other hand, the recent computational optimization studies of Refs. [

29,

30,

31] recently achieved the PCE of 31 % for CsSnI

3-based PSCs, 27 % and 31.62 % for CsSnBr

3-based PSCs when using rGO and WSe

2 transport layers, which have never been investigated on KSnI

3-based PSCs. Thus, there is still hope that the PCE of KSnI

3-based PSCs can still be significantly improved using carefully chosen and optimized HTL and ETL materials.

In this work, we performed a computational optimization of FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se using the state-of-the-art SCAPS-1D simulation tool. Our choice of Al-ZnO, LiTiO

2, ZnO, SnO

2, and rGO was driven by their high charge mobility, strong thermal stability except for the case of ZnO, excellent conductivity, and optimal band alignment with KSnI

3 [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Furthermore, rGO is known for having low trap states in the absorption layer/hole transport layer interface [

36]. In particular, we optimized the aforementioned structures by varying the thickness of each layer, and the dopant density of ETLs, KSnI

3, and rGO layers. This interestingly yielded tremendous improvement in the performance of KSnI

3-based perovskite solar cells. This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides the details of the computational methods used in this study.

Section 3 presents our results and their comparison with the literature, while section 4 contains the conclusions.

3. Results

The optimization strategy followed in this study is two-fold. We started by optimizing the FTO/AlZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se structure, by varying the thickness and dopant density of each layer in this structure. In this optimized structure we substituted AlZnO with other ETLs, namely LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2, of which we also optimized the thickness and donor dopant density to obtain optimized FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se. The optimization of the aforementioned parameters was done as a result of the reasons discussed below.

The main function of the HTL in a perovskite solar cell is to effectively prevent the migration of electrons from the perovskite layer (PL) to the HTL, and allow the transmission of holes from the PL to the HTL and the anode [

40]. However, if the thickness of the HTL is higher than the optimal thickness, the hole will have long paths to migrate within the HTL. As a result, the recombination probability will increase and the performance of the PSC will be poor. Similarly, if the HTL is thinner than its optimal thickness, the HTL will not be effective in extracting holes from the PL. Hence, the optimization of the HTL thickness is very crucial for improving the PCE of the perovskite solar cell. Similarly, the key function of the ETL is to extract electrons from the PL and transport them to the cathode. Its thickness also plays a vital role in the device's performance. For instance, it may yield low efficiency in charge collection if it is too thin, while it may decrease conductivity if it is too thick [

41]. Furthermore, the major roles of a perovskite layer in a PSC are the attenuation of the solar spectrum within the visible-light energy range, and the generation of electron-hole pairs through the photovoltaic process. The thickness of the PL highly affects its performance. For instance, if the PL is too thick it will not have sufficient volume to absorb light and thus, yield a low density of excitons. On the other hand, if it is too thick, it reduces the performance of the PSC since the recombination rate increases with the increase in the PL thickness [

31]. Therefore, it is very critical that the thickness of PL is optimized to achieve the highest possible performance of the PSC.

Similarly, the acceptor dopant density of the HTL, donor dopant density of the ETL, and acceptor dopant density of the active perovskite absorber layer play very crucial roles in the performance of perovskite solar cells. In particular, the separation of electron-hole pairs in PSC devices improves with the enhancement in the electric field that exists at the interface between the ETL and absorber layer, and at the interface between the HTL and absorber layer. The electric field strength increases with the increase in the donor dopant density of the ETL and acceptor dopant density of the HTL, and this improves the performance of the device [

42]. Even the electric field within the PL depends on the dopant density of the PL, and this electric is also responsible for the reduction of recombinations within the PL [

42]. However, if the dopant density is too high, it results in Coulomb traps which increase the likelihood of charge recombination. Thus, finding the optimal dopant densities of the ETL, HTL, and PL is very crucial for every PSC device.

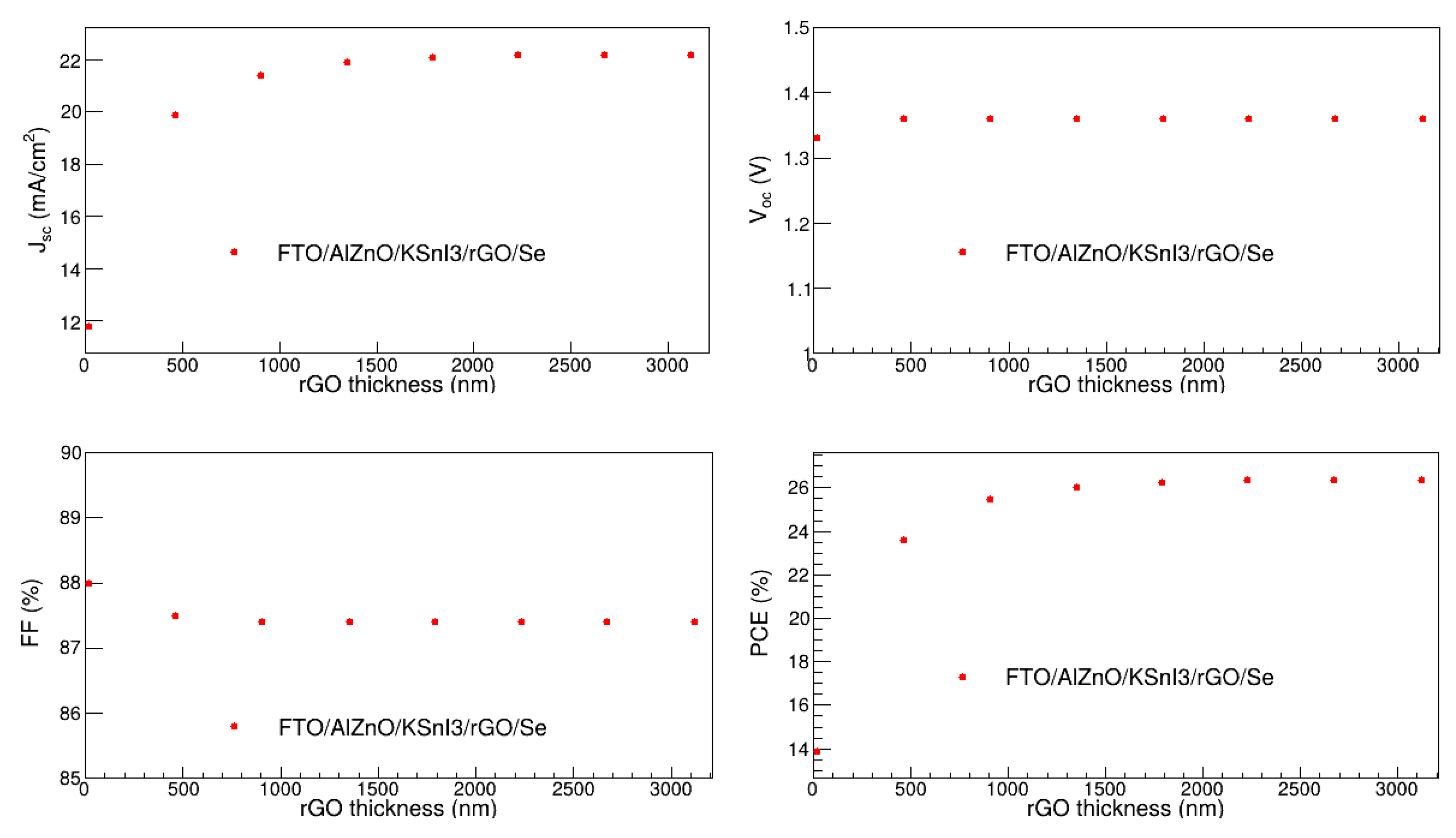

3.1. Optimization of the Hole Transport Layer Thickness

In this work, we optimized the thickness of rGO HTL by varying it from 20 nm to 4000 nm and assessed its impact on the open circuit voltage (V

oc), short-circuit current (J

sc), fill-factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE). The rest of the parameters were kept constant at their initial values shown in

Table 1. The results are depicted in

Figure 4. We observe that the J

sc increases fast as the rGO thickness increases towards 1000 nm, and thereafter remains relatively constant. On the other hand, V

oc is relatively constant. In particular, J

sc ranges from 11.823 to 22.182 mA/cm

2, while V

oc ranges from 1.334 to 1.361 V. On the other hand, FF somewhat decreases as the rGO thickness approaches 500 nm, beyond which it is practically constant. The PCE shows a similar trend as J

sc. Quantitatively, FF ranges between 87.99 % and 87.39 %, while PCE is in the range of 13.88 to 26.38 %. The trends observed on the performance metrics are similar to the recent results of Refs. [

42,

43,

44]. The increase in the V

oc and PCE is attributed to the enhancement in hole extraction from the perovskite layer and transportation to the anode as the HTL thickness increases. The reduction in FF with the increase in HTL thickness may be due to the lateral resistance in the junction between HTL and the active absorption layer. The highest PCE is observed at 2670 nm. Thus, 2670 nm was deemed the optimal thickness of the rGO layer.

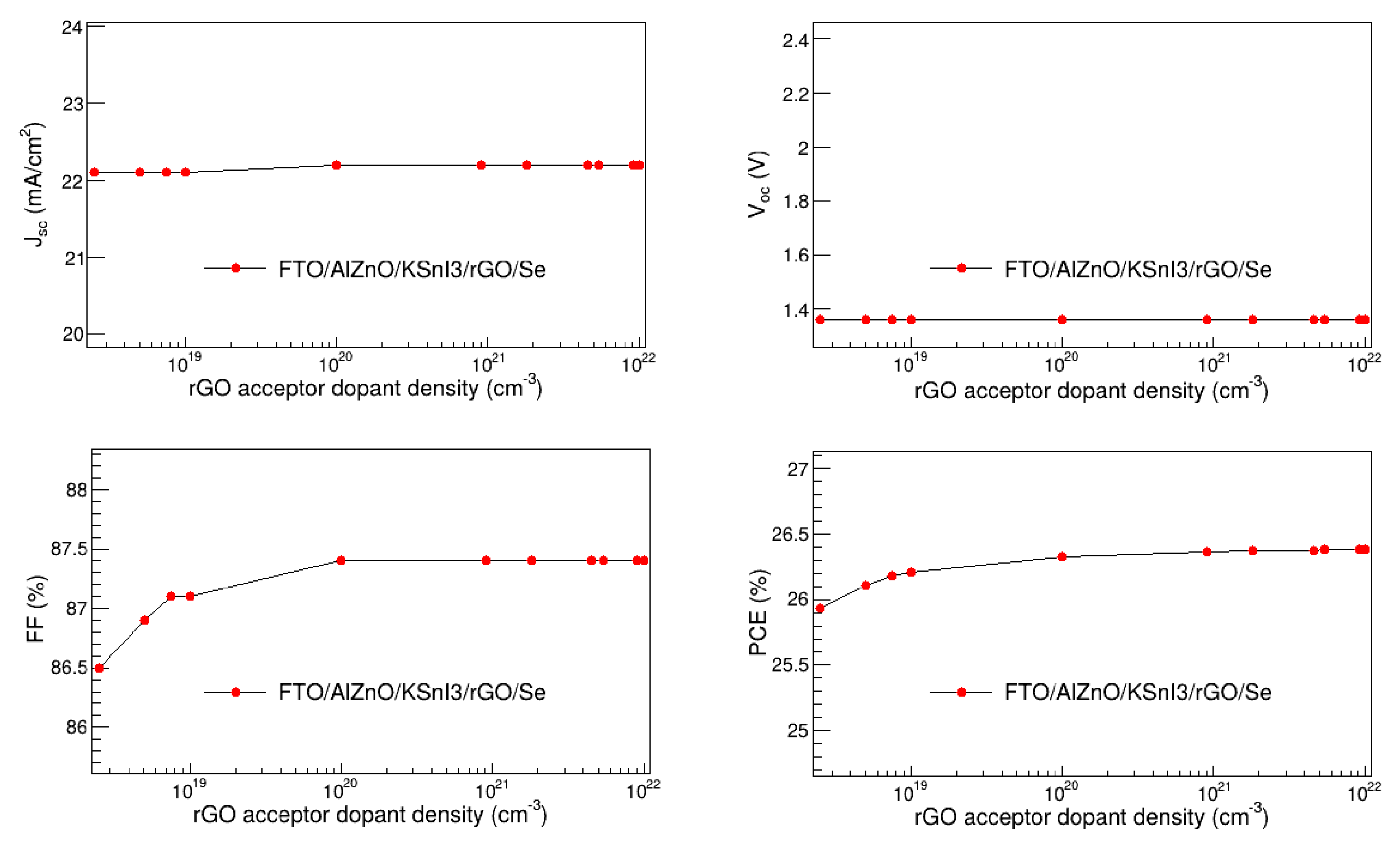

3.2. Optimization of the Hole Transport Layer Dopant Density

In this study, the acceptor dopant density of rGO was optimized by varying it between 2.5x10

18 cm

-3 and 10

22 cm

-3, and examined the dependence of V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE on HTL acceptor dopant density, as shown in

Figure 5. The thickness of this HTL was fixed at its optimal value of 2670 nm obtained in section 3.1, while the rest of the parameters were fixed at their values shown in table 1. The results show that J

sc and V

oc do not change with the change in the acceptor dopant density of the rGO HTL. In contrast, FF and PCE somewhat increase as the acceptor dopant density rises towards 10

20 cm

-3 and 10

19 cm

-3, respectively, and thereafter remain constant. The notable increase in FF and PCE is due to the enhancement in the exciton separation as the result of the increase in electric field strength at the HTL/absorber interface [

46]. In particular, J

sc is in the range of 22.17 to 22.26 mA/cm

2, and V

oc is 1.36 V. On the other hand, FF and PCE are in the ranges of 86.51 to 87.38 %, and 25.93 to 26.38 %, respectively. This highest PCE of 26.38 % is observed at the acceptor dopant density of 5.45x10

21 cm

-3. As a result, 5.45x10

21 cm

-3 was considered the optimal acceptor dopant density of rGO.

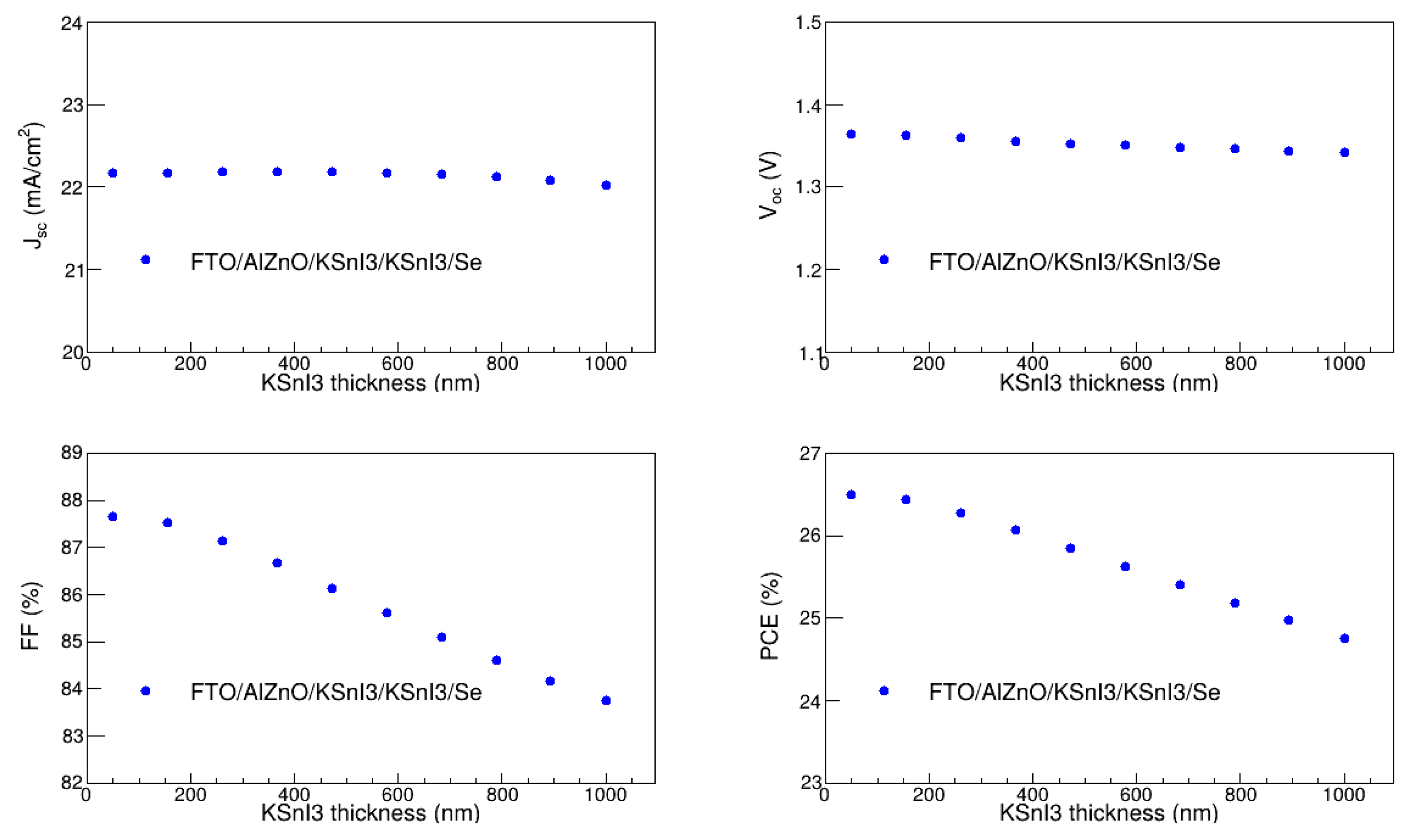

3.3. Optimization of Perovskite Layer Thickness

In the present study, we optimized the thickness of the KSnI

3 active absorption layer by varying it from 50 nm to 1000 nm, and kept the thickness and acceptor dopant density of the HTL at their optimal values obtained in sections 3.1 and 3.2, while the rest of the parameters were kept at their respective values provided in

Table 1. The variation of V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE with PL thickness is depicted in

Figure 6. We observe that J

sc and V

oc do not significantly change as the KSnI

3 layer thickness increases. On the other hand, the FF, and PCE are decreasing functions of PL thickness in the entire 50 nm to 1000 nm region. In particular, J

sc, V

oc, FF, and PCE range from 22.02 mA/cm

2 to 22.18 mA/cm

2, 1.34 V to 1.36 V, 87.65 % to 83.75 %, and 26.50% to 24.76%, respectively. Clearly, the performance of the PL deteriorates with the increase in its thickness. This is due to the increase in recombination rate with the increase in the perovskite layer thickness [

31,

47]. Thus, the optimal thickness of the PL was considered to be 50 nm, at which the highest PCE is observed.

3.4. Optimization of Perovskite Layer Acceptor Dopant Density

We optimized the acceptor dopant density of the perovskite layer by varying it from 10

19 cm

-3 to 10

22 cm

-3 and examined the dependence of the V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE on the dopant density. During this process, the thickness and dopant density of the HTL were at their optimal values obtained in sections 3.1 and 3.2, the thickness of the PL was fixed at its optimal value obtained in section 3.3, and the rest of the parameters were kept at their respective values provided in table 1.

Figure 7 presents V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE as a function of the acceptor dopant density of the PL. It was observed that J

sc decreases with the increase in dopant density, and it ranges between 14.40 mA/cm

2 and 22.16 mA/cm

2. In contrast, V

oc increases slowly with the increase in the PL acceptor dopant density. In particular, it ranges from 1.36 V to 1.48 V. This rise in V

oc is the reflection of the increase in built-in potential, resulting from the increase in the acceptor dopant density [

48]. Similarly, the FF rises as the dopant density increases towards 10

21 cm

-3, and thereafter, remains relatively constant. In particular, it is in the range of 84.10 % and 91.10 %. This increase in the FF corresponds to the reduction in the resistivity of the absorption layer [

49]. On the other hand, the PCE slightly rises as the dopant density approaches 10

21 cm

-3, above which it is a decreasing function of the acceptor dopant density. Quantitatively, PCE has the lowest value of 19.45% and the highest value of 27.36 %. The notable reduction in J

sc and PCE with the increase in dopant density may be attributed to the decrease in charge carrier mobility and rise in charge recombination rate [

17,

50,

51]. The highest PCE occurs at the dopant density of 8.33x10

20 cm

-3, which is therefore considered the optimal acceptor dopant density of the PL.

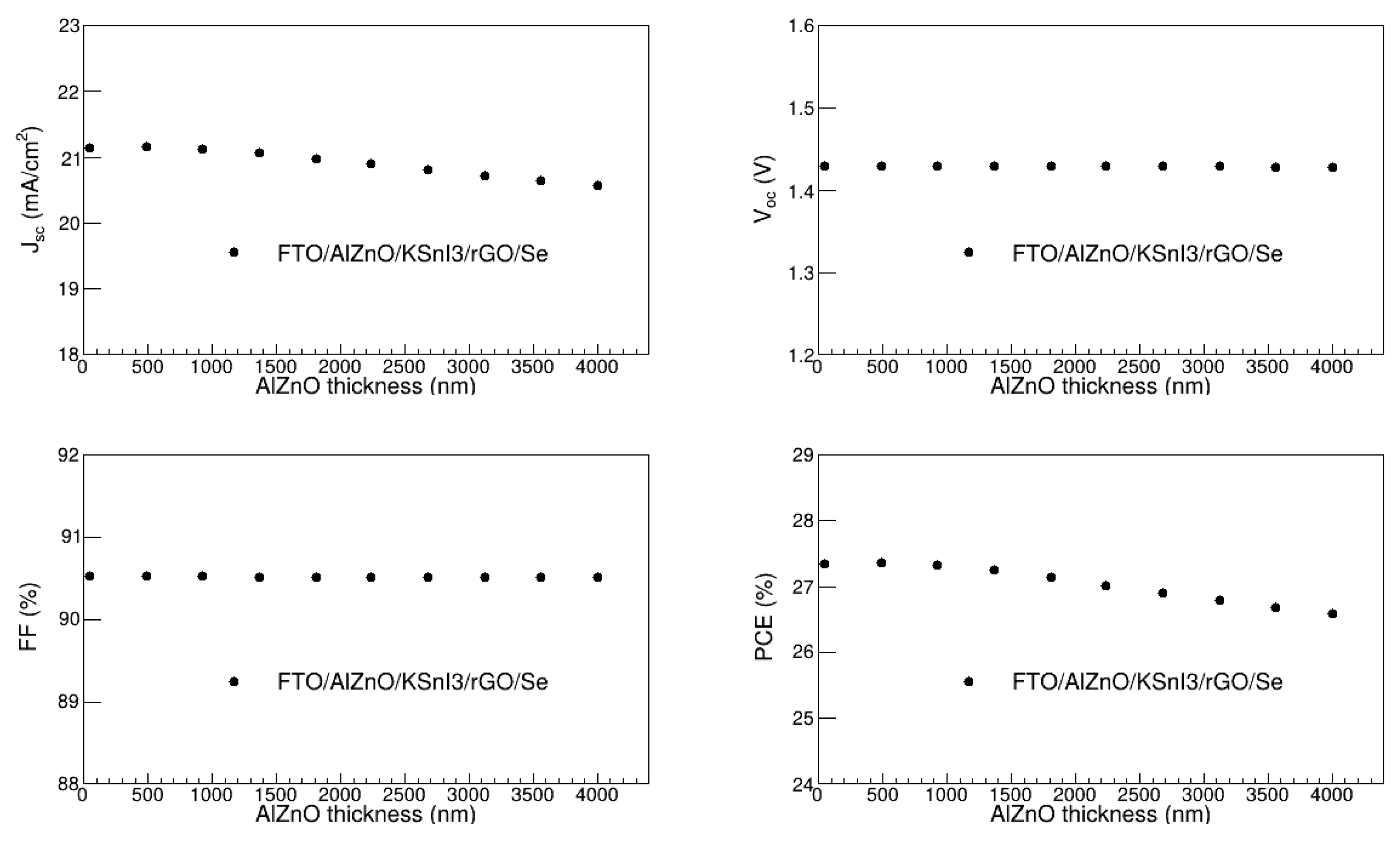

3.5. Optimization of Electron Transport Layer Thickness

In the present study, the thickness of the Al-ZnO electron transport layer was optimized through its variation from 50 nm to 4000 nm. The other parameters were fixed at their optimal values found in sections 3.1 to 3.4, while those that have not been optimized were kept at their initial values shown in table 1. The dependence of V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE on the Al-ZnO thickness is presented in

Figure 8. The J

sc and PCE are relatively constant at thicknesses smaller than 1000 nm, and then slowly decline as the thickness increases. In particular, J

sc is in the range of 20.56 to 21.16 mA/cm

2, while PCE ranges between 26.58 % and 27.37 %. The V

oc and FF on the other hand remain practically stable, at 1.43 V and 90.52 %, in the entire 50 nm to 4000 nm ETL thickness range. Thus, it is clear that the overall performance of the PSC device slightly declines as the Al-ZnO becomes thicker. This observation is consistent with the literature. It could be attributed to the increase in resistance and deterioration in conductivity as a result of the increase in ETL thickness [

30,

47]. The highest PCE is observed at the Al-ZnO thickness of 489 nm, which was, thus, considered the optimal thickness of the Al-ZnO ETL.

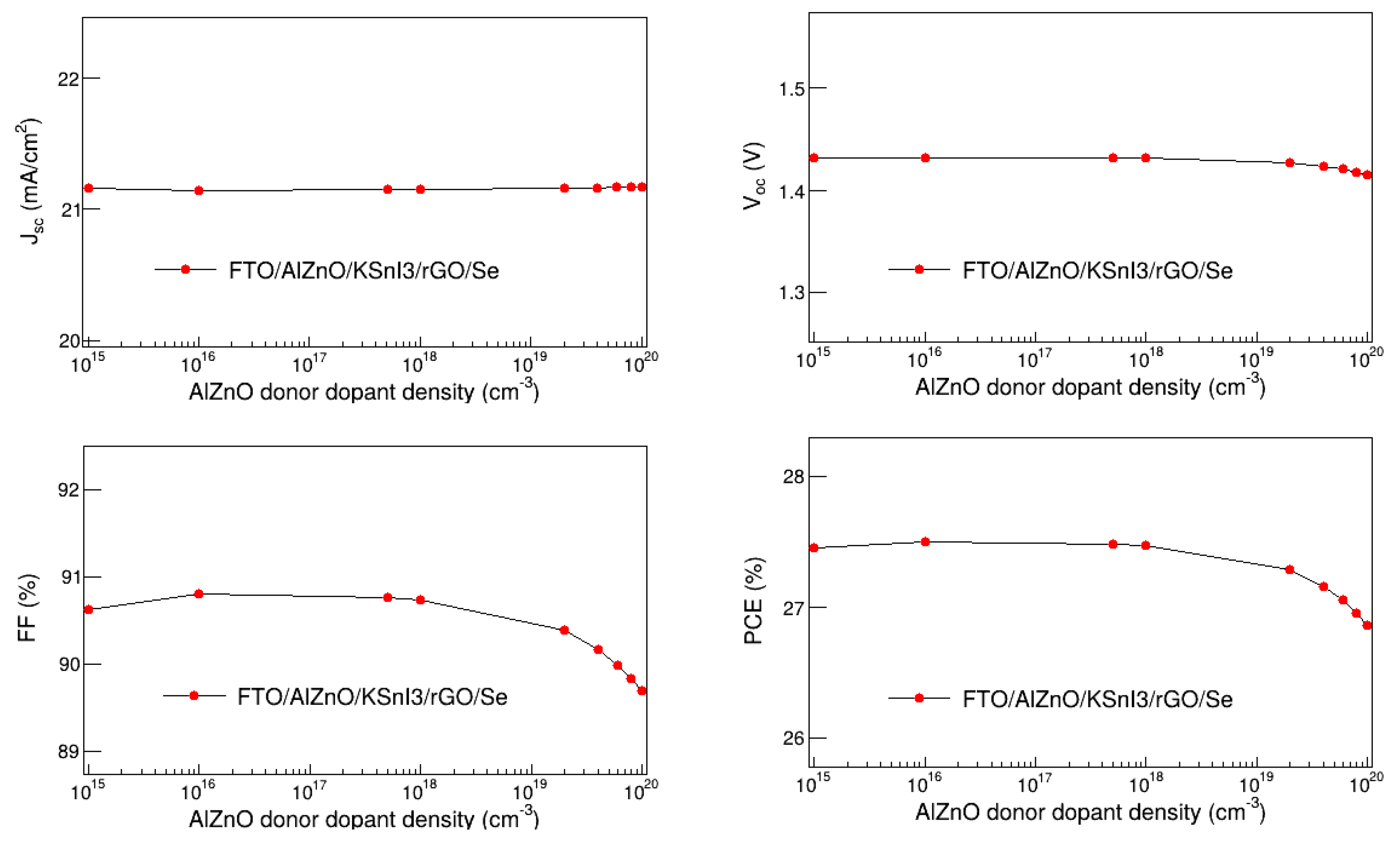

3.6. Optimization of Electron Transport Layer Donor Dopant Density

In this work, we found the optimal donor dopant density of the Al-ZnO electron transport layer by examining how it affects V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE. These performance metrics were assessed in the 10

15 to 10

20 cm

-3 donor dopant density range, as depicted in

Figure 9. The results reveal that J

sc and V

oc are unaffected by the change in donor dopant density of Al-ZnO, and they are in the range of 21.16 to 21.17 mA/cm

2 and 1.41 to 1.43 V, respectively. The FF and PCE are relatively constant donor dopant densities smaller than 10

18 cm

-3, and thereafter slowly decrease with the increase in the donor dopant density. In particular, they are in the range of 89.69 to 90.81%, and 27.50 to 26.86 %, respectively. Thus, the overall performance of the device slightly deteriorates with the increase in the donor dopant density of the Al-ZnO layer, at high dopant densities. This may be due to Coulomb traps which are understood to result from high dopant concentrations and cause a reduction in charge mobility [

52,

53]. The highest value of PCE occurs at the dopant density of 10

15 cm

-3, which was therefore deemed the optimal donor dopant density of the Al-ZnO ETL.

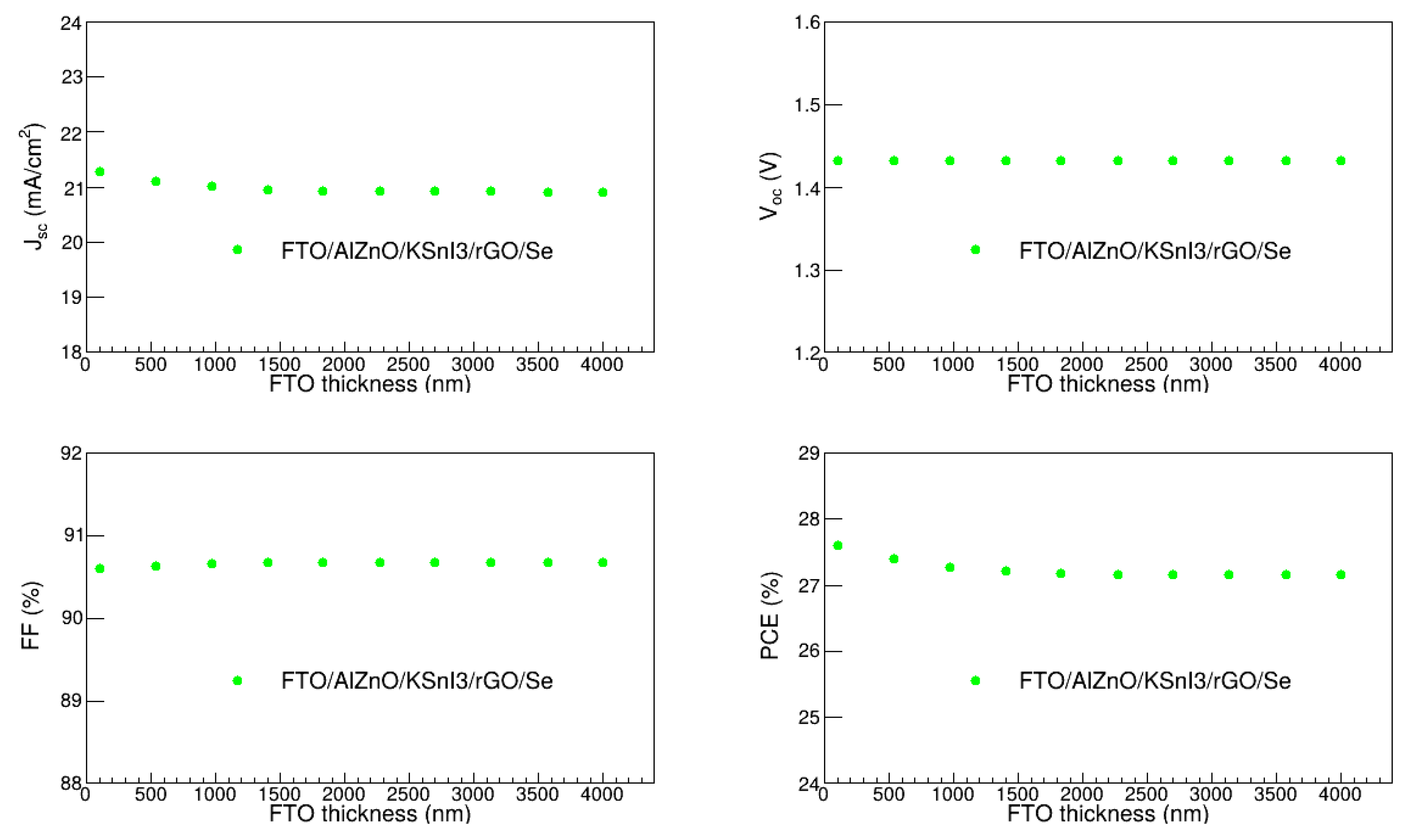

3.7. Optimization of FTO Layer Thickness

We also optimized the thickness of the FTO layer by varying it between 100 nm and 4000 nm, and assessed the impact of this on the V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE, as presented in

Figure 10. The results show the performance metrics do not change much as the thickness increases. The J

sc varies between 20.91 mA/cm

2 and 21.28 mA/cm

2, and V

oc remains 1.43 V. FF ranges from 90.60 to 90.68 %, and PCE ranges from 27.15 to 27.60 %. Thus, the device performance is not highly affected by the FTO thickness. The slight decline in J

sc and PCE at low FTO thickness may be attributed to the increase in series resistance and optical losses which are correlated to the increase in the FTO thickness. The highest PCE occurs at the thickness of 100 nm, which was, therefore, deemed the optimal thickness of the FTO layer.

This is the end of the optimization of the FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se structure. It was used as the framework for optimization of the FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se configurations, as presented in the next sections.

3.8. Substitution of Al-ZnO Electron Transport Layer

In the further analysis, we found the optimal FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se PSC configurations by substituting Al-ZnO with LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2 in the optimized FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se structure. During this process, the thicknesses and dopant densities of rGO, KSnI3, and FTO layers were kept at their optimal values found in the previous sections, while the thicknesses and donor dopant densities of LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2 were varied to assess their impact on Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE.

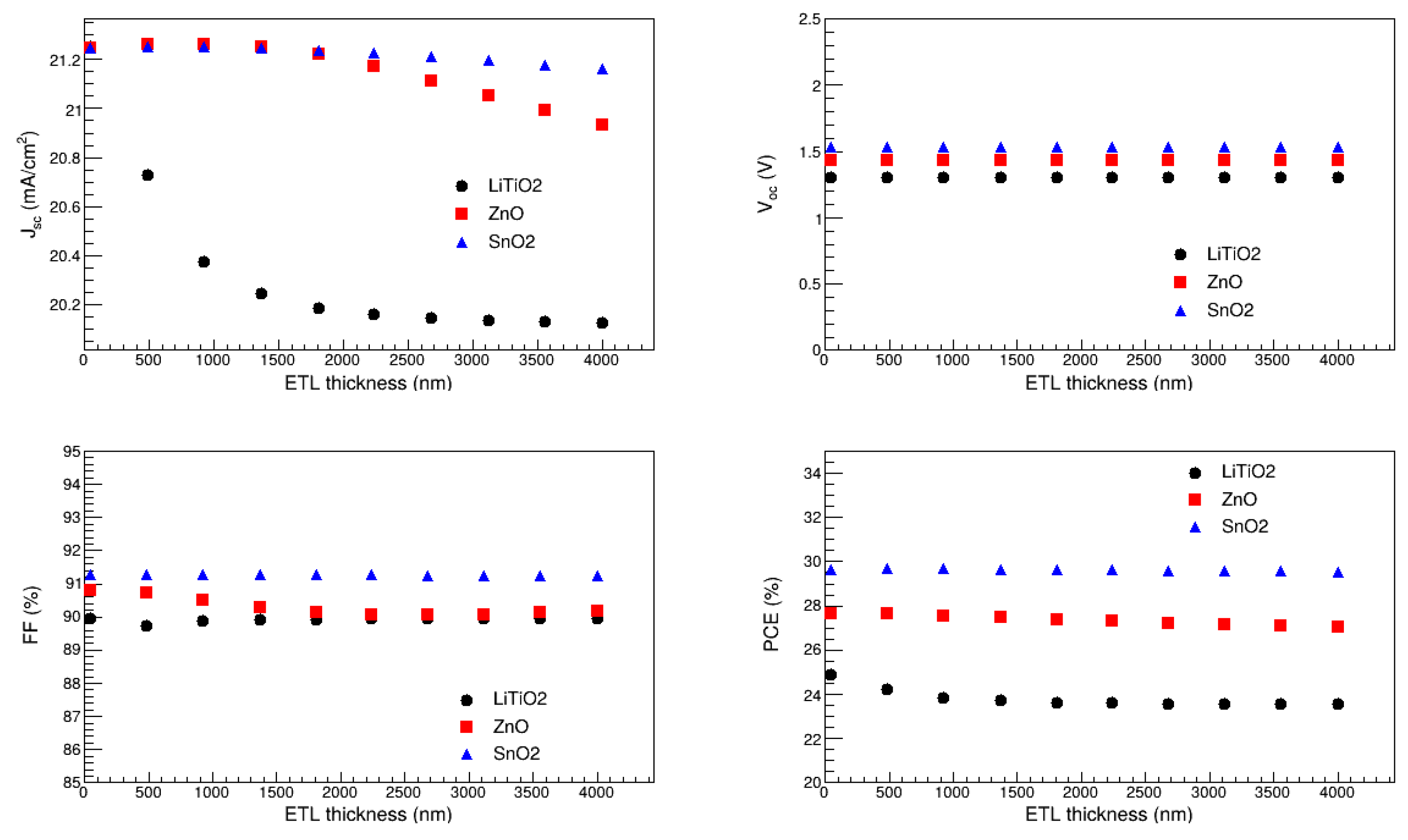

3.8.1. Optimization of LiTiO2, ZnO and SnO2 Thickness

The ETL thicknesses of the FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se perovskite solar cell structures were optimized by varying the thicknesses of LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2 from 100 nm to 4000 nm, and observed the dependence of V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE on the thickness. The results are depicted in

Figure 11. We observe that for ETL = LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2, V

oc is relatively constant in the entire 100 to 4000 nm ETL thickness range. In particular, V

oc is 1.30 V, 1.43 V, and 1.53 V for LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2, respectively. The J

sc corresponding to SnO

2 and ZnO is relatively stable in the whole thicknesses range, while for LiTiO

2 it slightly decreases as the thickness approaches 1500 nm and thereafter remains constant. In particular, J

sc is in the range of 20.13 to 21.25 mA/cm

2, 20.93 to 21.26 mA/cm

2, and 21.16 to 21.25 mA/cm

2 for LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2, respectively.

The results also show that FF is practically constant for all ETL materials. Quantitatively, it is in the range of 91.25 to 91.27 % for SnO

2, 90.04 to 90.81 % for ZnO, and 89.72 to 89.95 % for LiTiO

2. Furthermore, PCE shows trends similar to J

sc. It is relatively stable for ZnO, and SnO

2, while for LiTiO

2 it somewhat decreases as the thickness rises towards 1000 nm and thereafter remains unaffected by the thickness. In particular, it ranges from 23.57 to 24.91 % for LiTiO

2, 27.03 to 27.64 % for ZnO, and 29.53 to 29.67 % for SnO

2. Thus, the thickness of ZnO, and SnO

2 does not have a significant impact on the overall performance of FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se devices, while the increase in the thickness of LiTiO

2 slightly reduces the overall performance of the FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se device. The deterioration in the PCE and J

sc, for LiTiO, with the increase in the ETL thickness may result from an increase in series resistance, and the low transmission of light through the ETL layer [

49]. The highest PCE is observed at 50 nm for LiTiO

2 and ZnO, and 489 nm for SnO

2. Thus, these were considered the optimal thicknesses of LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2, in the FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se PSC structures.

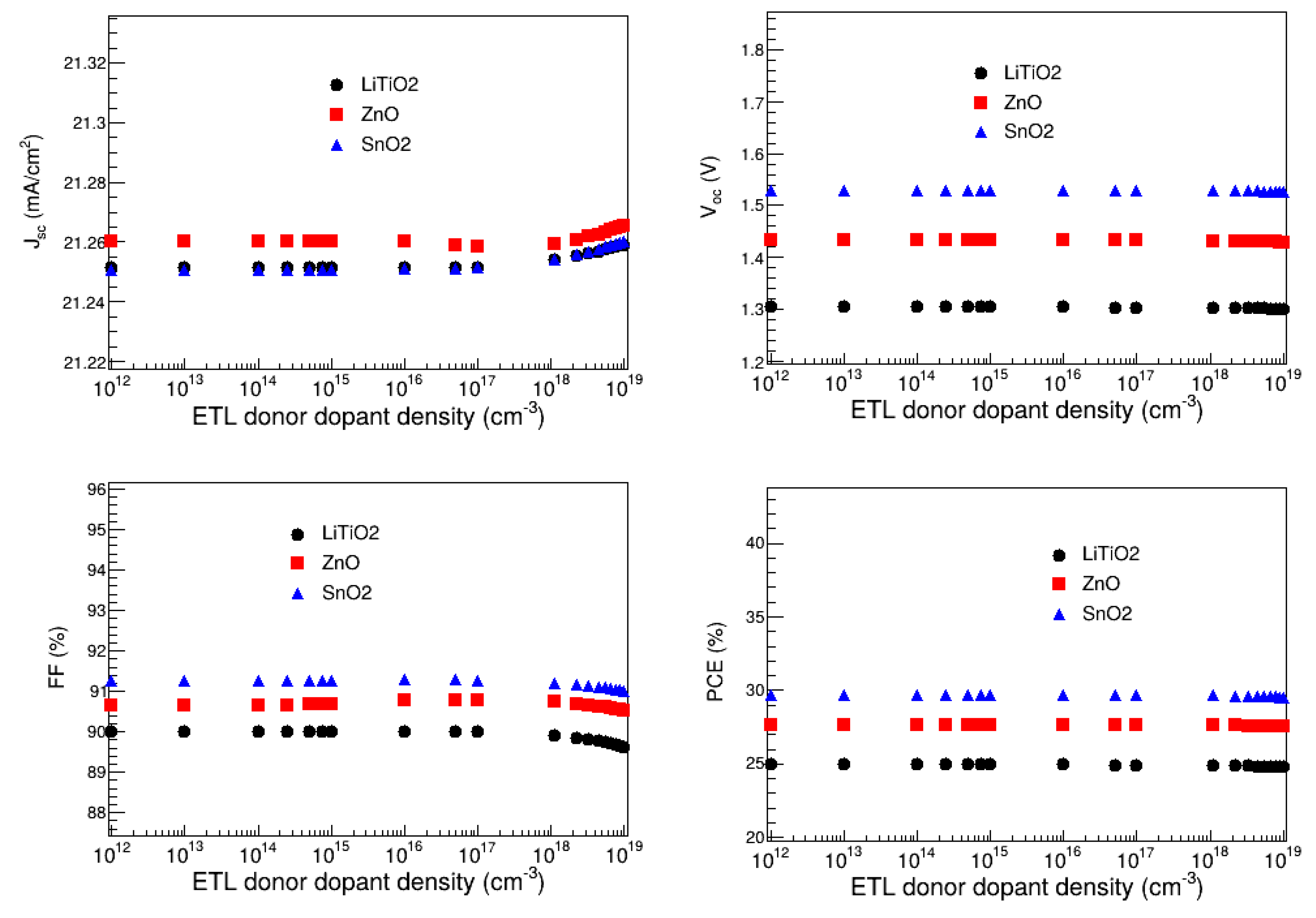

3.8.2. Optimization of LiTiO2, ZnO and SnO2 Donor Dopant Density

The donor dopant density of the LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2 electron transport layers was optimized, by varying it between 10

12 and 10

19 cm

-3, and observing its effect on the J

sc, V

oc, FF, and PCE, while keeping the rest of the parameters at their optimal values found in the previous sections. As depicted in

Figure 12, the results show that J

sc, V

oc, FF, and PCE are not significantly affected by the donor dopant density of LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2. Thus, the donor dopant densities of LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2 do not have a significant impact on the overall performance of the FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se solar cells. These observations are consistent with the recent literature [

43]. In particular, J

sc is in the range of 21.25 to 21.26 mA/cm

2 for LiTiO

2, 21.25 to 21.26 mA/cm

2 for SnO

2, and 21.26 to 21.27 mA/cm

2 for ZnO. V

oc is 1.30 V for LiTiO

2, 1.53 V for SnO

2, and 1.43 V for ZnO. Furthermore, FF is 89.63 to 90.01 % for LiTiO

2, 91.01 to 91.28% for SnO

2, and 90.52 to 90.79 % for ZnO. The PCE, on the other hand, is in the range of 24.77 to 24.94 % for LiTiO

2, 29.67 to 29.53 % for SnO

2, 27.51 to 27.62 % for ZnO. The highest PCEs are observed at the donor dopant densities of 10

12 cm

-3 for LiTiO

2, and 10

16 cm

-3 for SnO

2 and ZnO. Thus, these were deemed the optimal donor dopant densities for ETL = LiTiO

2, ZnO, and SnO

2.

3.9. Optimized Parameters and Performance Metrics

Table 5 presents the optimized parameters of FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se PSC structures. The rest of the parameters remained unchanged as shown in Tables 1.

Table 6 presents the performance metrics of the optimized PSC structures. These correspond to the optimized structural and electronic properties shown in table 3. It is clear that FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se has the highest PCE. Thus, it became our main focus in the rest of the analysis.

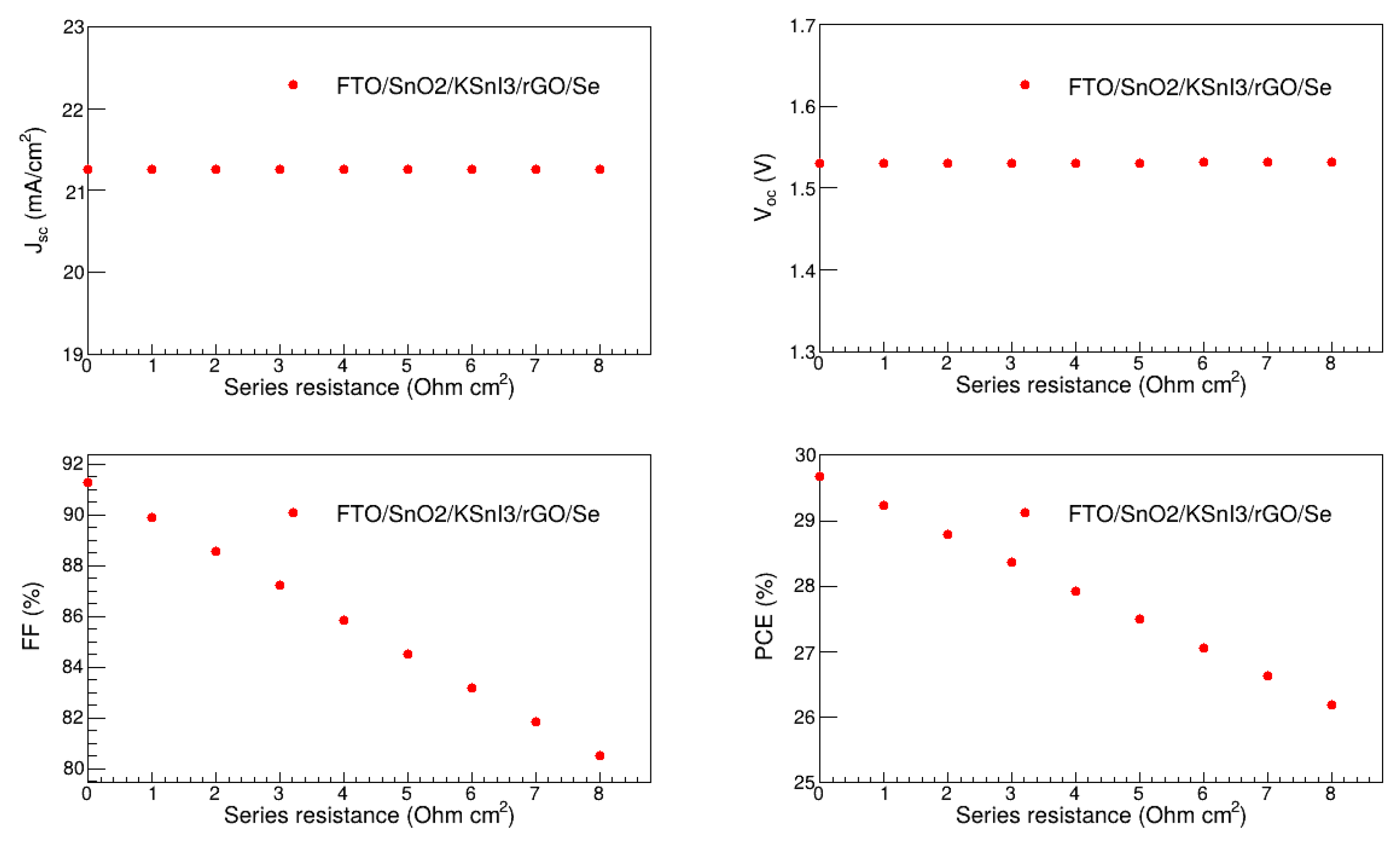

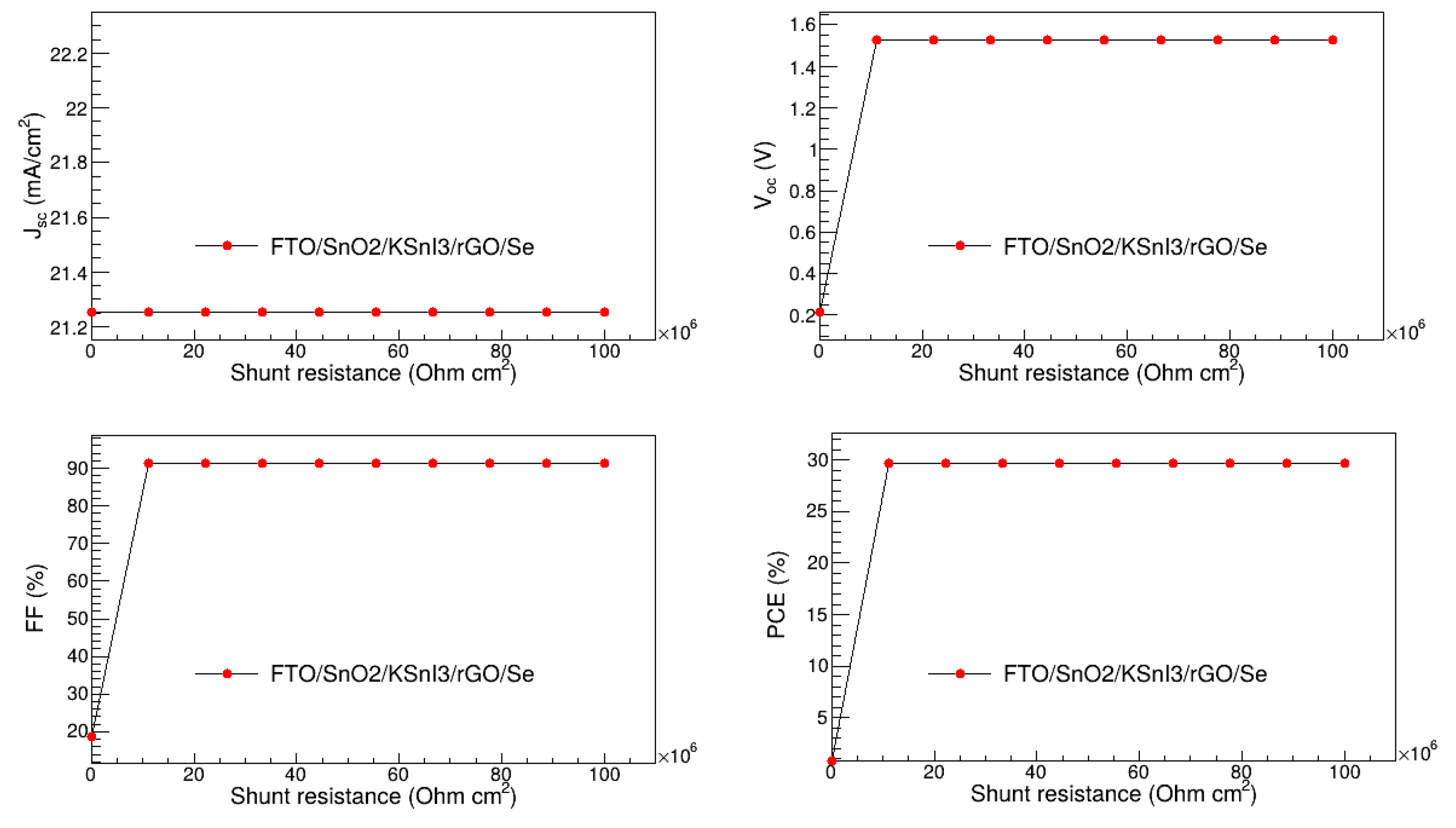

3.10. Effect of Series and Shunt Resistance

Series resistance (R

s) and shunt resistance (R

sh) are some of the crucial parameters that highly affect the performance of perovskite solar cells. Failure to optimize them may result in poor performance of the PSC device. Series resistance is understood to exist at various contact points of the device such as anode, cathode, and interfaces. On the other hand, shunt resistance is a desired property in a PSC and it prevents the flow of undesired shunt current which reduces the net current of the device. In this study, we investigated the effect of the R

s and R

sh on the performance of our highest-performing PSC structure which is FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se. In particular, we varied R

s and R

sh from 0 to 8 Ω cm

2, and 0 to 10

8 Ω cm

2, respectively, while other parameters were kept at the optimal values found in the previous sections. The results are presented in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. We observe that J

sc and V

oc are unaffected by the change in R

s, while FF and PCE are both decreasing functions of R

s. In particular, J

sc and V

oc are 21.25 mA/cm

2 and 1.53 V, respectively, while FF and PCE are in the range of 91.27 to 80.51 % and 29.67 to 26.19 %, respectively. Thus, the overall performance of the FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se device deteriorates with the increase in R

s. These results are similar to other observations in the literature Ref. [

31]. The decline in the FF with an increase in R

s is consistent with the dependence of FF on R

s, given by FF = FF

0(1 – R

s) where FF

0 is the fill factor in the absence of series resistance [

29].

Furthermore, the change in R

sh also does not affect the J

sc, while V

oc, FF, and PCE rapidly rise as the R

sh approaches 10

7 Ω cm

2 above which they remain relatively stable. This is consistent with the observations of Ref. [

29]. Quantitatively, J

sc is 21.25 mA/cm

2 in the whole R

sh region, while V

oc, FF, and PCE are in the range of 0.213 to 1.53 V, 18.74 to 91.27 %, 0.8463 to 29.67 %, respectively. Thus, 10

7 Ω cm

2 was deemed the optimal R

sh for the FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se PSC device.

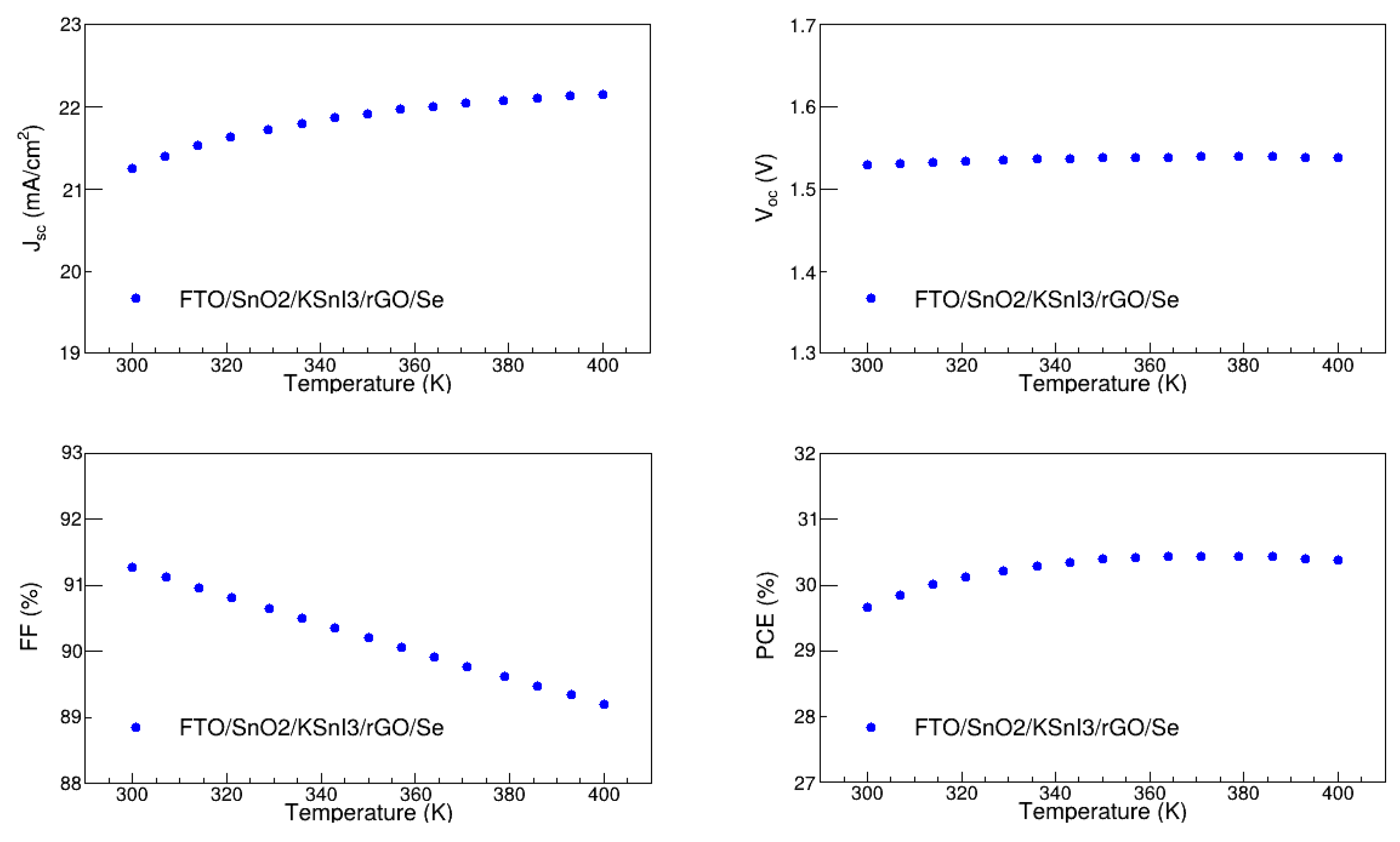

3.11. Effect of Temperature

Temperature is also a critical factor that can highly influence the overall performance of the perovskite solar device. In this study, we examined the effect of the temperature on J

sc, V

oc, FF, and PCE of the FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se configuration by varying the temperature from 300 K to 400 K. The rest of the parameters were fixed at their optimal values found above. The results are shown in

Figure 15, and reveal that V

oc remains constant, while J

sc slowly rises with the increase in temperature. The gradual increase in J

sc corresponds to the reduction in the band gap of the absorption layer, resulting in the enhancement in the generation of electron-hole pairs [

54,

55]. The PCE follows the same increasing trend as J

sc. This is similar to the recent observations of Ref. [

56]. On the other hand, FF decreases with the increase in temperature. This is consistent with the temperature dependence of FF given by [

6].

where nkT/q is the thermal voltage. Quantitatively, J

sc, V

oc, FF, and PCE range from 21.25 to 22.15 mA/cm

2, 1.53 to 1.54 V, 91.27 to 89.20 %, 29.67 to 30.44 %, respectively. The highest PCE is observed at 371 K and this was considered the optimal operation temperature for the FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se PSC structure.

Table 7 presents the performance metrics of the optimized PSC structures when the optimal R

s, R

sh, and temperature of 0, 10

7 Ω cm

2, and 371 K, respectively, are assumed. These also correspond to the optimized structural and electronic properties shown in table 5.

3.12. Comparison of Results with Literature

Table 8 shows the V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE of the optimized FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/LiTiO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se PSC structures, and V

oc, J

sc, FF, and PCE of all KSnI

3 perovskite solar cells available in the literature. All our investigated PSC configurations are higher than the PCE of 22.78 % which is currently the highest PCE of KSnI

3-based perovskite solar cells. In fact, the highest performing PSC structure, FTO/SnO

2/KSnI

3/rGO/Se, has a PCE of 30.44 % under ideal R

s, R

sh and temperature conditions. This is 7.66 % more efficient than the FTO/SnO

2/3C–SiC/KSnI

3/NiO/C which is the highest-performing PSC known in the literature thus far.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we optimized FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se PSC structures using the SCAPS-1D simulation package. In particular, we optimized the thicknesses and dopant densities of rGO, KSnI3, Al-ZnO, LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2 layers, as well as the thickness of FTO. This yielded the PCE of 27.60 %, 24.94 %, 27.62 %, and 30.44 % for FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se, and FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se, respectively. Thus, the PCE of FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se is 7.66 % higher than the PCE of FTO/SnO2/3C–SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C, which is currently the highest performing KSnI3-based perovskite solar cells in the literature. Thus, we propose FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se as the new highest-performing KSnI3-based PSC. We also call for experimental studies to further verify and improve the proposed configuration. The ideal performance conditions of this newly developed PSC configuration are series resistance of zero, shunt resistance of 107 Ω cm2, and temperature of 371 K. The series resistance of zero is impossible to achieve in real life, but this work shows that it should be minimized as much as possible.

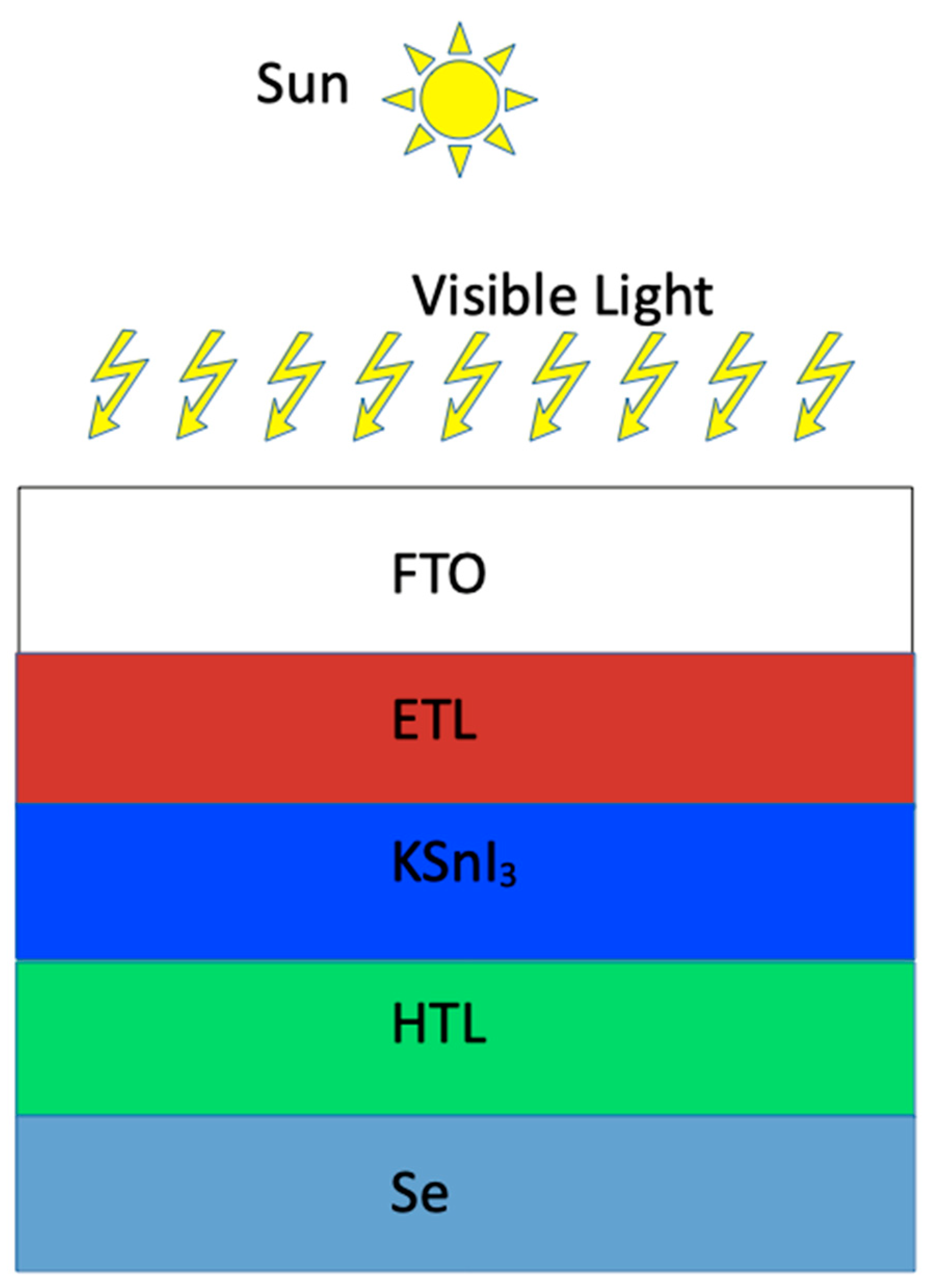

Figure 1.

Schematic layout of FTO/ETL/KSnI3/HTL/Se device.

Figure 1.

Schematic layout of FTO/ETL/KSnI3/HTL/Se device.

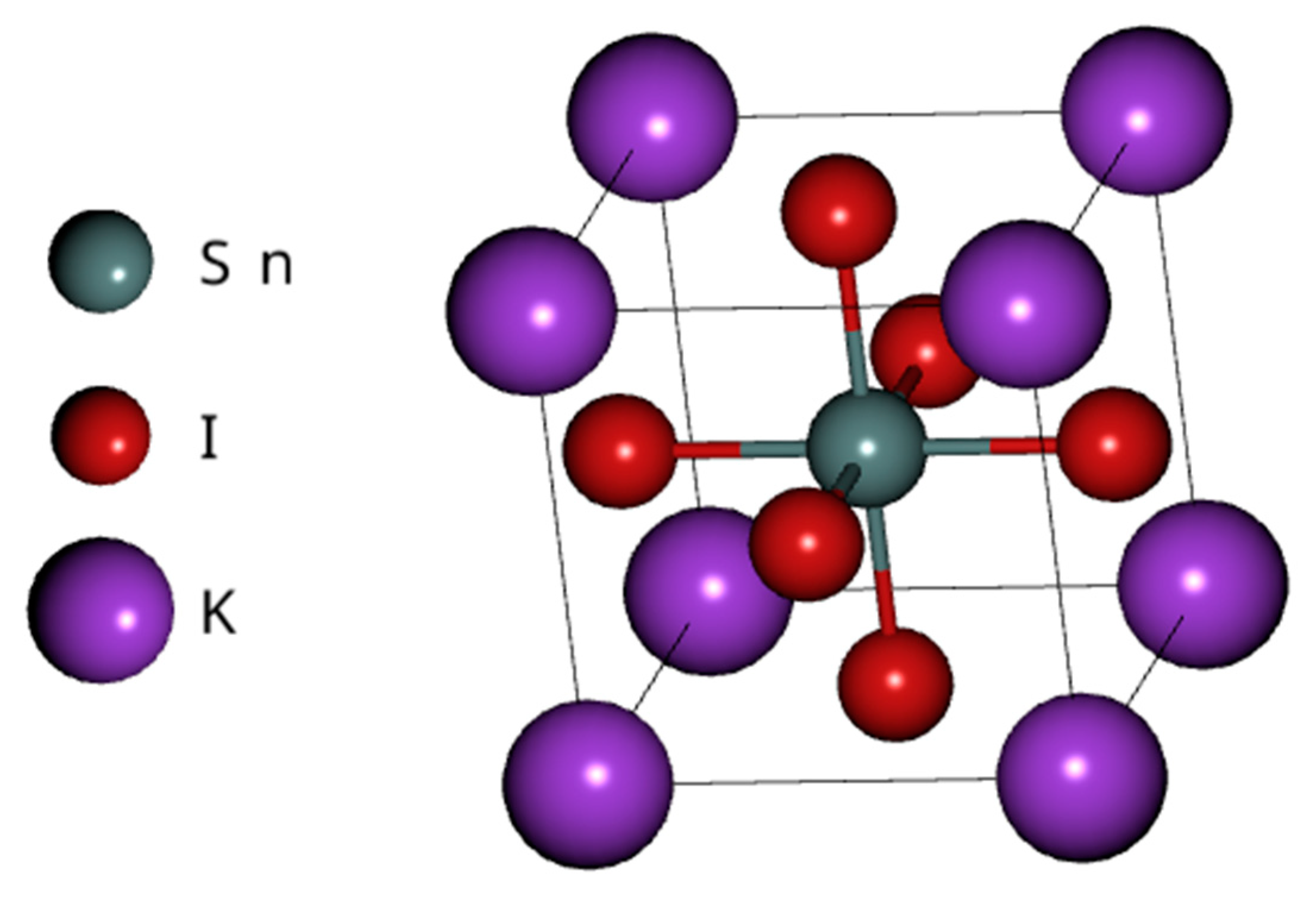

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of the perovskite material KSnI3.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of the perovskite material KSnI3.

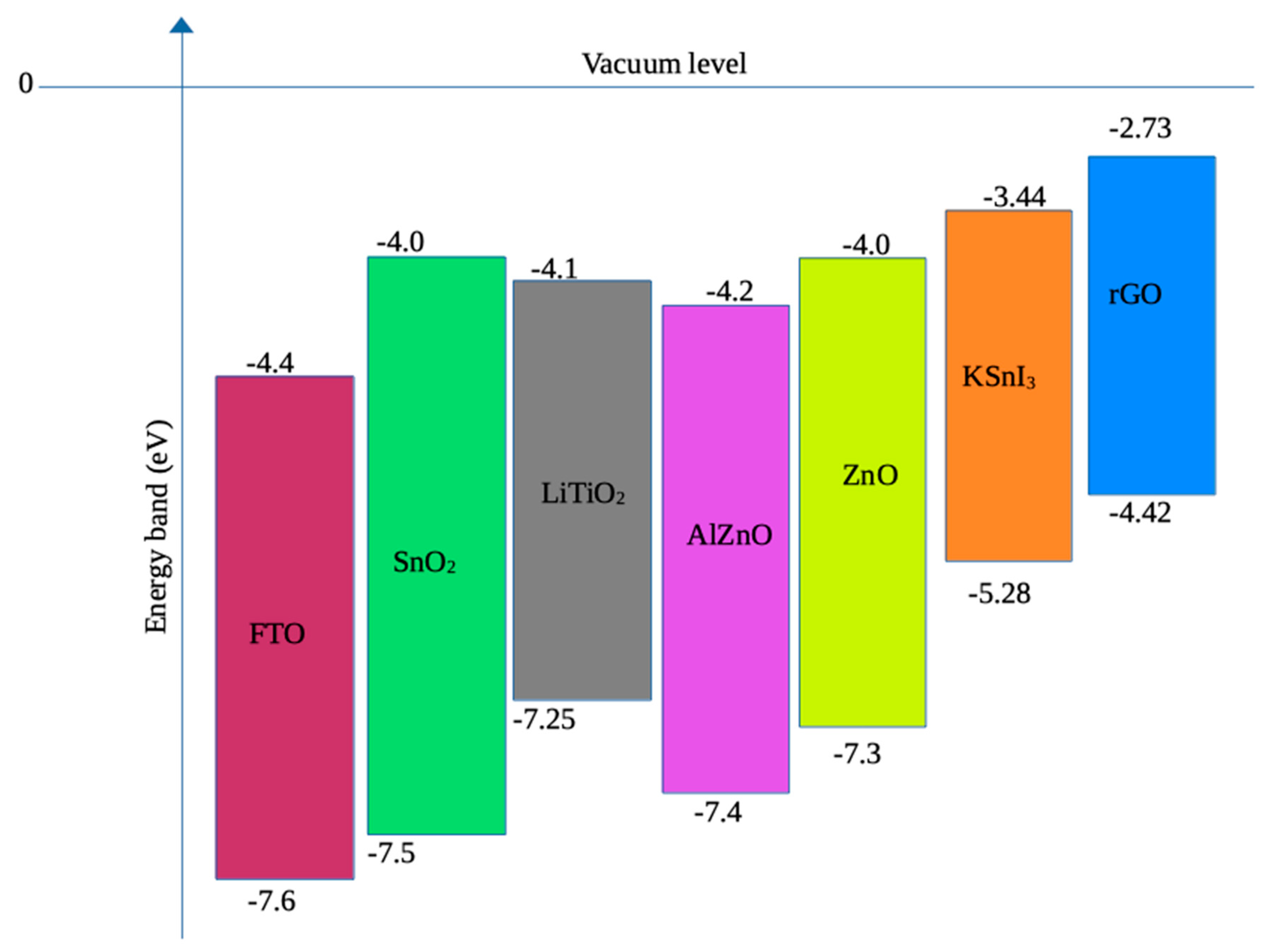

Figure 3.

Energy band diagram of FTO, ETLs, HTL, and KSnI3.

Figure 3.

Energy band diagram of FTO, ETLs, HTL, and KSnI3.

Figure 4.

Dependence of Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE on rGO thickness.

Figure 4.

Dependence of Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE on rGO thickness.

Figure 5.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of rGO dopant density.

Figure 5.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of rGO dopant density.

Figure 6.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of PL thickness.

Figure 6.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of PL thickness.

Figure 7.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of PL acceptor dopant density.

Figure 7.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of PL acceptor dopant density.

Figure 8.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of Al-ZnO thickness.

Figure 8.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of Al-ZnO thickness.

Figure 9.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of Al-ZnO dopant density.

Figure 9.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of Al-ZnO dopant density.

Figure 10.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of FTO thickness.

Figure 10.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of FTO thickness.

Figure 11.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of the thicknesses of LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2.

Figure 11.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of the thicknesses of LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2.

Figure 12.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of the dopant density of LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2.

Figure 12.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of the dopant density of LiTiO2, ZnO, and SnO2.

Figure 13.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of series resistance.

Figure 13.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of series resistance.

Figure 14.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of shunt resistance.

Figure 14.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of shunt resistance.

Figure 15.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of temperature.

Figure 15.

Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE as a function of temperature.

Table 1.

Properties of the KSnI

3, ETL, HTL, and FTO used in the simulations before optimization [

28,

29,

30].

Table 1.

Properties of the KSnI

3, ETL, HTL, and FTO used in the simulations before optimization [

28,

29,

30].

| parameters |

FTO |

Al-ZnO |

LiTiO2

|

ZnO |

SnO2

|

KSnI3

|

rGO |

| Thickness (nm) |

400 |

400 |

400 |

400 |

400 |

400 |

400 |

| Eg (eV) |

3.5 |

3.1 |

3.15 |

3.28 |

3.5 |

1.84 |

1.69 |

| χ (eV) |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3.9 |

3.44 |

3.56 |

| εr

|

9 |

9 |

13.6 |

9 |

9 |

10.4 |

13.3 |

| Nc (cm-3) |

2.02x1018

|

2x1018

|

3x1020

|

2x1018

|

2.2x1018

|

2.2x1018

|

1018

|

| Nv (cm-3) |

1.8x1019

|

1.8x1019

|

2x1020

|

1.8x1019

|

1.8x1019

|

1.8x1019

|

1.8x1019

|

| Vth,n (cm s-1) |

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

| Vth,h (cm s-1) |

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

| μn (cm2/V/s) |

2x101

|

13.84 |

30 |

43 |

200 |

21.28 |

2.6x101

|

| μp (cm2/V/s) |

1x10-1

|

25 |

0.01 |

25 |

80 |

19.46 |

1.23x102

|

| NA (cm-3) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1x1016

|

1022

|

| ND (cm-3) |

2x1019

|

1.02x1019

|

2x1017

|

2.9x1015

|

1x1017

|

1x1015

|

0 |

| Nt (cm-3) |

1015

|

1015

|

1014

|

1015

|

1015

|

1015

|

1014

|

Table 2.

Interface defect input parameters [

28,

29].

Table 2.

Interface defect input parameters [

28,

29].

| Interface |

HTL/KSnI3

|

ETL/KSnI3

|

| Defect type |

Neutral |

Neutral |

| Energetic distribution |

Single |

Single |

| Capture cross-section for electrons (cm-2) |

10-19

|

10-19

|

| Capture cross-section for holes (cm-2) |

10-19

|

10-19

|

| Reference for defect energy level |

Above VB maximum |

Above VB maximum |

| Energy with respect to reference (eV) |

0.6 |

0.6 |

| Total density (cm-3) |

1x1010

|

1x1010

|

Table 3.

Properties used in the benchmark simulation of FTO/SnO

2/3C-SiC/KSnI

3/NiO/C PSC [

28] .

Table 3.

Properties used in the benchmark simulation of FTO/SnO

2/3C-SiC/KSnI

3/NiO/C PSC [

28] .

| parameters |

FTO |

SnO2

|

3C-SiC |

KSnI3

|

NiO |

| Thickness (nm) |

500 |

25 |

20 |

1500 |

20 |

| Eg (eV) |

3.2 |

3.5 |

2.36 |

1.84 |

3.8 |

| χ (eV) |

4 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

3.44 |

1.4 |

| εr

|

9 |

9 |

9.72 |

10.4 |

10.7 |

| Nc (cm-3) |

2.2x1018

|

2.2x1018

|

1.553x1019

|

2.2x1018

|

2.5x1019

|

| Nv (cm-3) |

1.8x1018

|

1.8x1019

|

1.163x1019

|

1.8x1019

|

2.8x1019

|

| Vth,n (cm s-1) |

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

| Vth,h (cm s-1) |

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

107

|

| μn (cm2/V/s) |

2x101

|

200 |

900 |

21.28 |

12 |

| μp (cm2/V/s) |

1x101

|

80 |

40 |

19.46 |

28 |

| NA (cm-3) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1x1016

|

1x1019

|

| ND (cm-3) |

2x1019

|

1x1020

|

1x1020

|

1x1015

|

0 |

| Nt (cm-3) |

1014

|

1015

|

1014

|

1014

|

1015

|

Table 4.

Benchmark results for the FTO/SnO2/3C-SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C configuration.

Table 4.

Benchmark results for the FTO/SnO2/3C-SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C configuration.

| PSC structure |

Voc (V) |

Jsc (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) |

PCE (%) |

Reference |

| FTO/SnO2/3C-SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C |

1.399 |

17.72 |

89.99 |

22.31 |

This work |

| FTO/SnO2/3C-SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C |

1.392 |

18.27 |

89.57 |

22.78 |

Ref. [28] |

Table 5.

Optimized parameters of FTO, ETLs, HTL, and KSnI3 for the four optimized PSC structures.

Table 5.

Optimized parameters of FTO, ETLs, HTL, and KSnI3 for the four optimized PSC structures.

| parameters |

FTO |

Al-ZnO |

LiTiO2

|

ZnO |

SnO2

|

KSnI3

|

rGO |

| Thickness (nm) |

100 |

489 |

50 |

489 |

489 |

50 |

2670 |

| NA (cm-3) |

|

|

|

|

|

8.33x1020

|

5.45x1021

|

| ND (cm-3) |

|

1015

|

1012

|

1016

|

1016

|

|

|

Table 6.

The Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of the optimized PSC configurations.

Table 6.

The Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of the optimized PSC configurations.

| PSC structure |

Voc (V) |

Jsc (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) |

PCE (%) |

| FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

1.44 |

21.28 |

90.15 |

27.60 |

| FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

1.30 |

21.25 |

90.01 |

24.94 |

| FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

1.43 |

21.26 |

90.70 |

27.62 |

| FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

1.53 |

21.25 |

91.27 |

29.67 |

Table 7.

The Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of the optimized FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se when optimal Rs, Rsh, and temperature are assumed.

Table 7.

The Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of the optimized FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se when optimal Rs, Rsh, and temperature are assumed.

| PSC structure |

Voc (V) |

Jsc (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) |

PCE (%) |

| FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

1.54 |

22.04 |

89.76 |

30.44 |

Table 8.

Performance metrics of the optimized PSC structures and literature.

Table 8.

Performance metrics of the optimized PSC structures and literature.

| PSC structure |

PCE (%) |

Reference |

| FTO/Al-ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

27.16 |

This work |

| FTO/LiTiO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

24.94 |

This work |

| FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

27.62 |

This work |

| FTO/SnO2/KSnI3/rGO/Se |

30.44 |

This work |

| FTO/TiO2/KSnI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/W |

9.776 |

[23] |

| FTO/C60/KSnI3/PTAA/C |

10.83 |

[24] |

| FTO/TiO2/KSnBr3/Cu2O/Au |

8.05 |

[39] |

| FTO/F16CuPc/KSnI3/CuPc/C |

11.91 |

[25] |

| FTO/ZnOS/KSnI3/NiO/C |

9.28 |

[26] |

| FTO/ZnO/KSnI3/CuI/Au |

20.99 |

[27] |

| FTO/SnO2/3C–SiC/KSnI3/NiO/C |

22.78 |

[28] |