1. Introduction

The global transportation sector is experiencing a profound transformation, driven by the rapid advancement and increasing deployment of autonomous vehicle (AV) technology. Once relegated to the realm of science fiction, AVs are transitioning into a present-day reality, holding the promise of revolutionizing mobility patterns and sustainable urban/rural development [

1,

2,

3]. This technological leap carries immense potential to address critical challenges that plague contemporary transportation systems, including traffic congestion, road accidents, greenhouse gas emissions, and mobility limitations for specific segments of the population [

4,

5], among others by reinforcing intelligent transport systems. Plus, the successful integration of AVs could be specially important in countries which faces accessibility issues in rural and/or isolated environments [

6].

In this vein, the development and deployment of AVs are progressing at an unprecedented pace, boosted by substantial investments from both public and private sectors. Automotive manufacturers, technology companies, and research institutions are actively engaged in developing, testing, and refining various levels of AV technology, ranging from Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) to fully autonomous vehicles capable of navigating complex and dynamic environments without human intervention [

7]. These systems, coupled with multiple advanced sensors and cameras and AI algorithms, empower AVs to detect and respond to potential hazards with greater speed and accuracy than human drivers [

8]. As AV technology matures and its integration into existing transportation systems accelerates, its influence is poised to extend far beyond the realm of transportation, impacting the broader society and economy [

9] by complementing existing public transport networks, reducing reliance on individual car ownership, and promoting more efficient shared mobility solutions.

In Spain, as in other technologically advanced nations, there is growing recognition of the potential of AVs to enhance transportation efficiency, safety, and accessibility. This recognition is further fueled by the understanding that AVs can significantly reduce human error, a leading cause of road crashes. However, while the technical feasibility of AVs is rapidly advancing, their successful deployment and integration into society hinges on a critical factor: acceptance and public trust [

10].

Public Trust: A Cornerstone for AV Deployment

Trust serves as the foundation for human-technology interaction, influencing individuals' willingness to accept, use, and rely on AVs in their daily lives [

11]. Without a sufficient level of public trust, individuals may be reluctant to embrace AVs, even offering tangible potential benefits in terms of safety, convenience, and efficiency [

10], and specially among individuals who may be more hesitant to adopt any emerging technologies.

This underscores the requirement for a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing public opinion and expectations regarding AVs, especially concerning initial trust perceptions and the specific "trust requirements" that individuals hold.

Trust in AVs is a foundational determinant of their adoption shaped by various elements, including perceived safety, reliability, competence, transparency, and control [

12,

13]. These factors are particularly relevant in urban environments, where AVs must seamlessly integrate into multimodal transport systems, ensuring smooth interactions between pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport users.

Perceived safety reflects the extent to which individuals believe that AVs are engineered to operate safely and reliably, minimizing the risk of accidents or harm to passengers and other road users [

14]. Reliability pertains to the consistency and dependability of AV performance, ensuring that AVs function as intended under various driving conditions and traffic scenarios [

15]. Competence refers to the perceived proficiency of AVs in executing driving tasks effectively, efficiently, and safely, reflecting their ability to navigate complex environments and respond appropriately to unexpected events [

16]. Transparency involves the extent to which AV decision-making processes are understandable and explainable to users, fostering a sense of confidence and control and mitigating concerns about algorithmic bias or unintended consequences [

17]. Users want to understand how the AV makes decisions and how it will respond in different situations [

18]. Control reflects the degree to which individuals perceive they can influence or override AV operations, even when operating in autonomous mode, allowing them to maintain a sense of agency and mitigate feelings of helplessness or vulnerability [

19].

Moreover, ethical considerations also play a crucial role: users want to be sure that the AV is programmed to make ethical decisions that align with their values and societal norms [

20]. This includes considerations such as prioritizing safety, minimizing harm, and respecting individual autonomy, but recent research has highlighted the importance of proactively addressing those ethical concerns [

6].

But trust implies a wider approach of a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, social, and contextual factors, including individual characteristics, experience, social norms, cultural values, and the design and communication of AV technology [

10,

21].

This initial trust is directly linked to user's individual "trust requirements", i.e. what minimum standards are required for them to perceive the AV system as worthy of being considered for everyday use. In other words, the need to perceive that the AV is reliable, safe, and capable of handling diverse driving scenarios. But this is a key challenge, given that direct experience with this technology might be absent in most of the population while initial direct experience with AVs plays a crucial role in shaping trust perceptions. Based on that, a stakeholder-centered design process emerges as a relevant mean of exploring initial perceptions [

22].

Factors Influencing Initial Trust in AVs

Positive experiences, such as riding in an AV without encountering safety incidents or malfunctions, can enhance trust levels, whereas negative experiences, such as witnessing an AV behaving erratically or being involved in a near-miss situation, can erode trust [

23]. Given that lack of exposure can impact trust, it has been recently proposed that appropriate testing and early experiences are vital for boosting public trust [

13].

The quality and credibility of information that individuals receive about AVs can significantly impact their trust beliefs. Accurate, transparent, and balanced information about the capabilities, limitations, and safety features of AV technology can foster trust, whereas biased, exaggerated, or misleading information can undermine trust and breed skepticism [

24]. In this regard, [

25] emphasize the necessity of increasing public knowledge about the technology as far as effective communication about AVs is as important as high quality design.

The attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of peers, family members, and influential figures can shape an individual's trust in AVs. If individuals perceive that their social network trusts AVs, they are more likely to adopt a positive attitude toward the technology, whereas if they perceive widespread skepticism or apprehension, they may be less inclined to trust AVs [

26].

Demographic variables such as age, gender, and education level can influence trust in AVs. Younger individuals, males, and those with higher levels of education tend to be more trusting of AVs compared to older individuals, females, and those with lower levels of education, who may feel less familiar with new innovations [

12,

27,

28]. Cultural values also play a significant role in shaping public attitudes toward AVs. Cultural dimensions such as individualism, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance can influence the acceptance and trust of technology.

A variety of emotions can impact user acceptance of AVs. Addressing these emotions through design can enhance adoption. The review by [

29] emphasizes how trust, but also other factors such as anxiety or excitement influence the perception of AVs.

Thus, understanding these factors and how they shape the public’s "trust requirements" is essential for designing AVs that are not only technologically advanced but also ethically responsible and socially acceptable for their subsequent successful integration in dayli operations [

23,

29].

Research Gap and Motivation

Despite the growing body of research around public perception of AVs, factors affecting trust and use of AVs vary depending on the driving context and use case [

21] and several critical gaps persist in the literature. First, there is a relative lack of studies that specifically examine the listed determinants of initial trust and trust requirements in AVs within concrete countries impacted by specific cultural and regulatory contexts, which may influence how the local population perceives and interacts with AV technology. Just as an example, data from 1,205 Spanish drivers of conventional vehicles show that perceived safety and the value attributed to AVs significantly influence the intention of adopting it [

30]. However, previous research on trust in AVs has primarily been conducted in North America and Western Europe [

27,

31], with limited exploration in the European context.

There is a need for more research that investigates the factors influencing initial trust in AVs, particularly among individuals who have limited or no direct experience with this emerging technology. Understanding how individuals form initial trust beliefs about AVs is essential for designing effective communication strategies and user interfaces that promote trust and acceptance and speed-up the real adoption by the whole population.

To address these challenges and opportunities, this paper presents a comprehensive analysis of public opinion and expectations regarding AVs in Spain draw from stakeholders-centered design approach [

22,

32]. The paper is based on a national survey designed to assess initial trust perceptions and trust requirements among a representative national sample of the population.

The ultimate goal of this paper is to provide valuable insights for policymakers, automotive manufacturers, and technology developers seeking to promote the ethical development and effective deployment of AVs. By understanding the factors that influence public opinion and expectations, stakeholders are able to develop strategies to increase market penetration and ensure that AVs are designed to meet the needs of all segments of the population. By addressing these research questions and achieving these objectives, this study will contribute to a better understanding of the complex interplay between technology, society, and trust, and will help to pave the way for a future where AVs can safely and effectively improve the lives of people.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

To investigate public opinion and expectations regarding AVs, a national online survey was conducted through Spanish population. Prior to the survey development, relevant literature was reviewed to identify key factors influencing trust and acceptance of AVs, particularly within the European context. The survey instrument was designed to assess these factors, aligning with the study's objectives.

The final questionnaire comprised three main sections: demographic information, assessment of social perception of AVs, and assessment of trust.

Demographic and Experience Data. The first section collected basic demographic information from participants, including age, gender, and highest level of education completed, and gross income level. Participants were also asked about their driving experience, including whether they held a valid driver's license and the modes of transportation they typically used on a regular workday. Finally, participants were asked about their prior experience with AVs ("Have you ever used an autonomous vehicle?").

Assessment of Social Perception of AVs. This section, based on the study “Social Perception of Autonomous Vehicles” [

33] included questions about the modes of transport that participants use regularly, as well as general opinions and expectations regarding AVs.

- -

Participants' general opinions on AVs were assessed using a single item adapted from a validated scale used in prior research [

33]. Participants were asked: "

What is your opinion about autonomous vehicles?".

- -

Expectations for AVs were evaluated using a ranking task regarding several features, including safety, comfort, environmentally friendly, travel time, cheap accessibility, reliability, and regulation.

Assessment of Trust. This section, adapted from [

25], assessed the participants' initial trust in AVs and trust requirements

- -

Initial Trust in AVs was measured using a four-item scale (∝=0.71). Participants indicated their level of agreement with the following statements using a six-point Likert scale.

- -

Trust Requirements were measured using a ten-item scale, assessing the level of agreement with the importance of various conditions for trusting AVs (∝=0.90). Participants indicated their level of agreement with ten statements starting with “I would trust an autonomous vehicle more if”, rated on a six-point Likert scale.

This set of instruments allowed for a comprehensive assessment of public perceptions and expectations regarding AVs, focusing on the key elements of initial trust and trust requirements.

Participants

To ensure a sufficiently large and representative dataset, 400 participants were involved. This decision was based on prior studies examining AV trust in various national contexts, where sample sizes between 300 and 500 were found to provide robust statistical power [

27]. Given that this study aimed to analyze multiple demographic and attitudinal factors influencing trust in AVs, the sample size ensured adequate subgroup representation while maintaining feasibility within the research constraints.

The sole inclusion criterion was being at least 18 years of age and living in Spain. The analyzed sample presented the following demographic profile: 41.50% were men, with an average age of 39.72 years (SD = 12.98), ranging from 18 to 75 years old. From an educational standpoint, participants were distributed across basic (12%), secondary (42%), and higher education levels (46%), originating from all Spanish autonomous communities (i.e. 17), except for La Rioja and Ceuta. Regarding economic status, gross annual income was heterogeneously distributed: 14.75% earned less than €12,000, 26.50% earned between €12,000 and €20,000, 44.50% earned between €20,000 and €45,000, and 14.25% earned over €45,000. A significant portion (87.75%) of participants held a driver’s license, and 33.25% had some prior experience with autonomous vehicles. When asked about transportation habits on workdays, 53% primarily used a car as the main driver, while 33.25% traveled as passengers. Cycling and walking were the least frequent options.

Statistical Analyses

The collected data were analyzed using R software. The analysis proceeded in two main stages: descriptive statistics and inferential statistics.

Descriptive statistics were computed to characterize the sample and provide an overview of the data. For the demographic and experience data, descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (gender, education level, driver's license possession, prior AV use, typical mode of transport on a workday) and Means and standard deviations for continuous variables (age).

Following the descriptive analysis, inferential statistics were used to examine relationships between demographic and experiential factors and key outcome variables aiming to analyse how key demographic and experiential variables influenced overall perceptions of goodness, probability, and trust. Specifically, the analysis aimed to infer how different groups of people, based on age, gender, education level, gross income, and prior AV use, varied in their opinions and expectations regarding AVs.

Due to the substantial number of individual questions in the survey, a composite variable was created to summarize responses related to average score across all questions related to Trust. It was calculated as the sum of individual item scores divided by the total possible score. Higher values on this variable indicate greater agreement related to trust. With this composite variable, statistical analysis was done through the following statistical analyses: Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test for age comparison across 4 groups, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for gender comparison across two groups. Also, the distribution analysis of trust in groups with different education level, income level, driving license possession, and previous experience with AVs was performed, also assessing normality within each group distribution

3. Results

3.1. Expectations Regarding Autonomous Vehicles

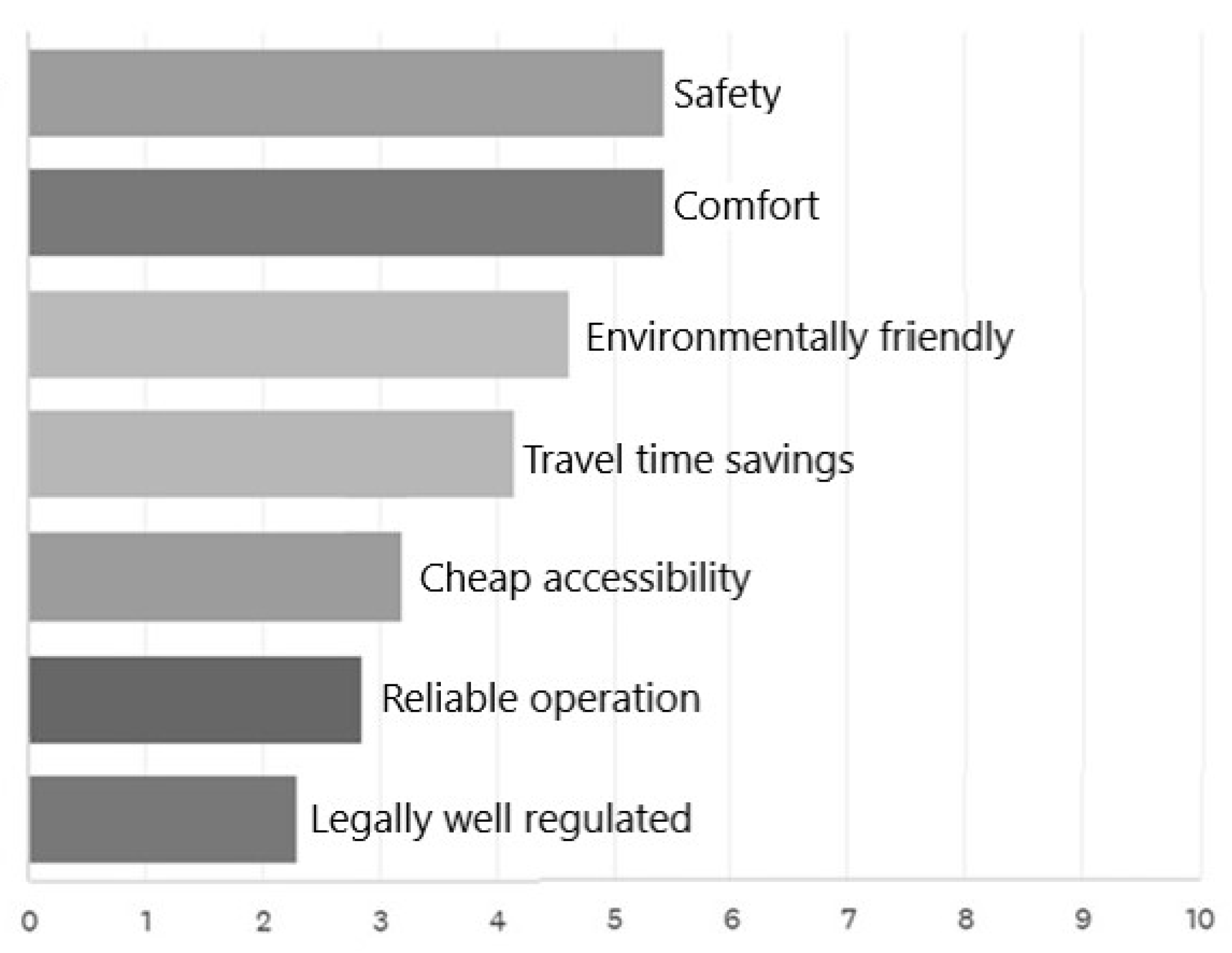

In the first part, the study focused on examining the expectations of the population regarding autonomous vehicles. The results reveal an interesting pattern in the priorities of respondents: the main expectations, in terms of relevance, are concentrated in three fundamental aspects: safety, comfort, and respect for the environment. These factors emerge as the most valued by participants, reflecting a clear concern for the user experience and the ecological impact of this new technology (

Figure 1).

In contrast, aspects that could be considered critical for the effective functioning and adoption of autonomous vehicles appear less relevant. Specifically, the technical reliability of the vehicles and the existence of adequate legal regulations are not positioned among the main concerns of the studied population.

This disparity between expectations centered on the user experience and the lower concern for technical and legal aspects suggests a possible lack of awareness or underestimation of the complexity inherent in the implementation of autonomous driving technologies. These findings raise important considerations for developers and regulators of this technology, highlighting the need to educate the public about the importance of these less visible but crucial aspects for the success and safety of AVs.

3.2. Trust in Autonomous Vehicles

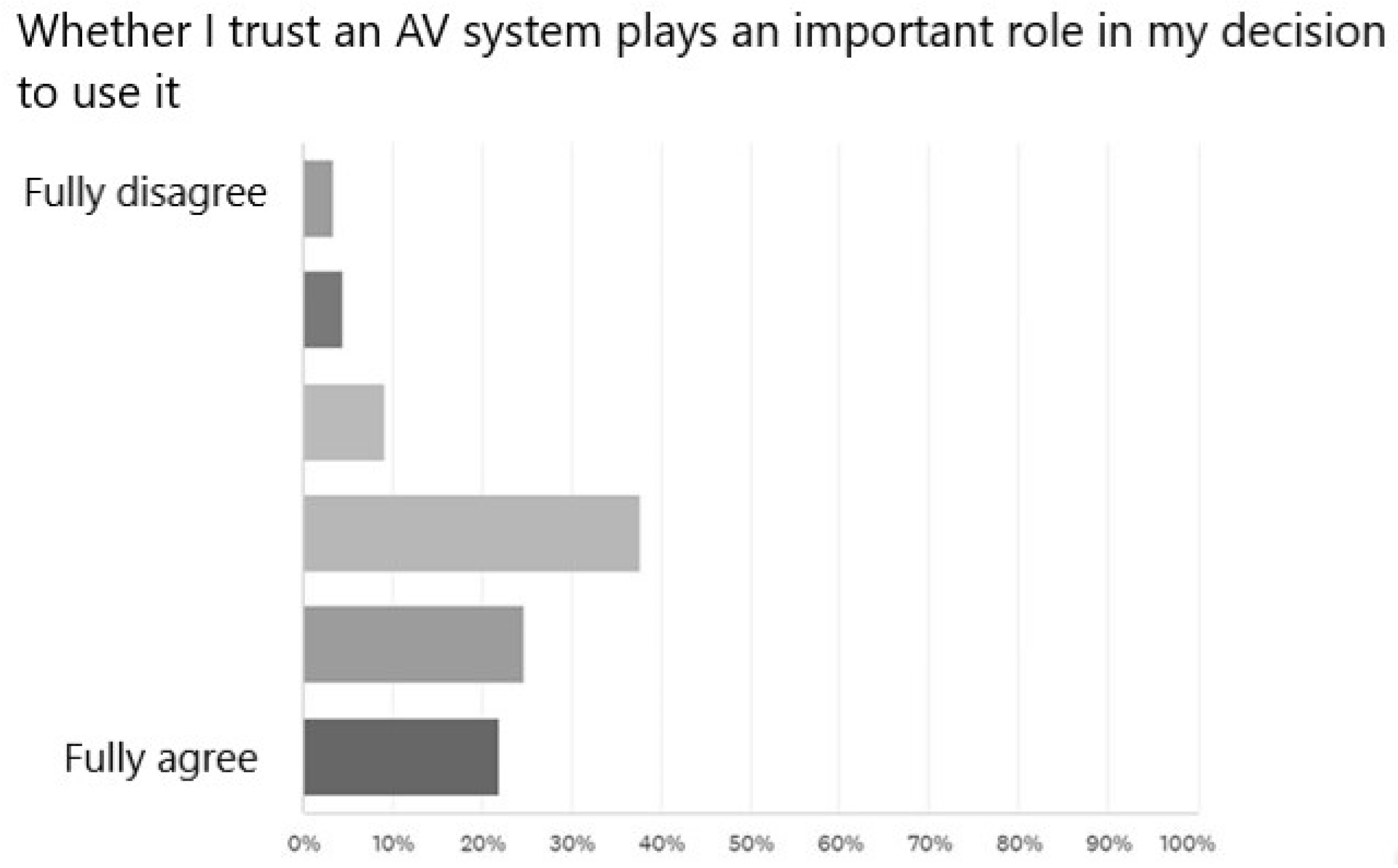

Despite the apparent lower concern for technical and legal aspects, our study reveals a crucial finding regarding trust in AVs (

Figure 2). Upon deeper examination, trust emerges as a decisive factor in the decision to use this technology, as 84.5% of respondents consider trust as a necessary aspect to decide to use AVs. This high percentage underscores the fundamental importance that participants place on feeling safe and confident in the technology before adopting it. This result contrasts with the lower relevance initially ascribed to issues such as technical reliability and legal regulation. It suggests that, although these aspects are not explicitly mentioned as priorities, they underlie the broader notion of trust that users require to accept and use AVs.

The apparent discrepancy between the low priority assigned to technical and legal aspects and the high importance of trust could indicate that users expect these elements to be guaranteed beforehand, considering them as implicit prerequisites for the development of the trust necessary to adopt this technology.

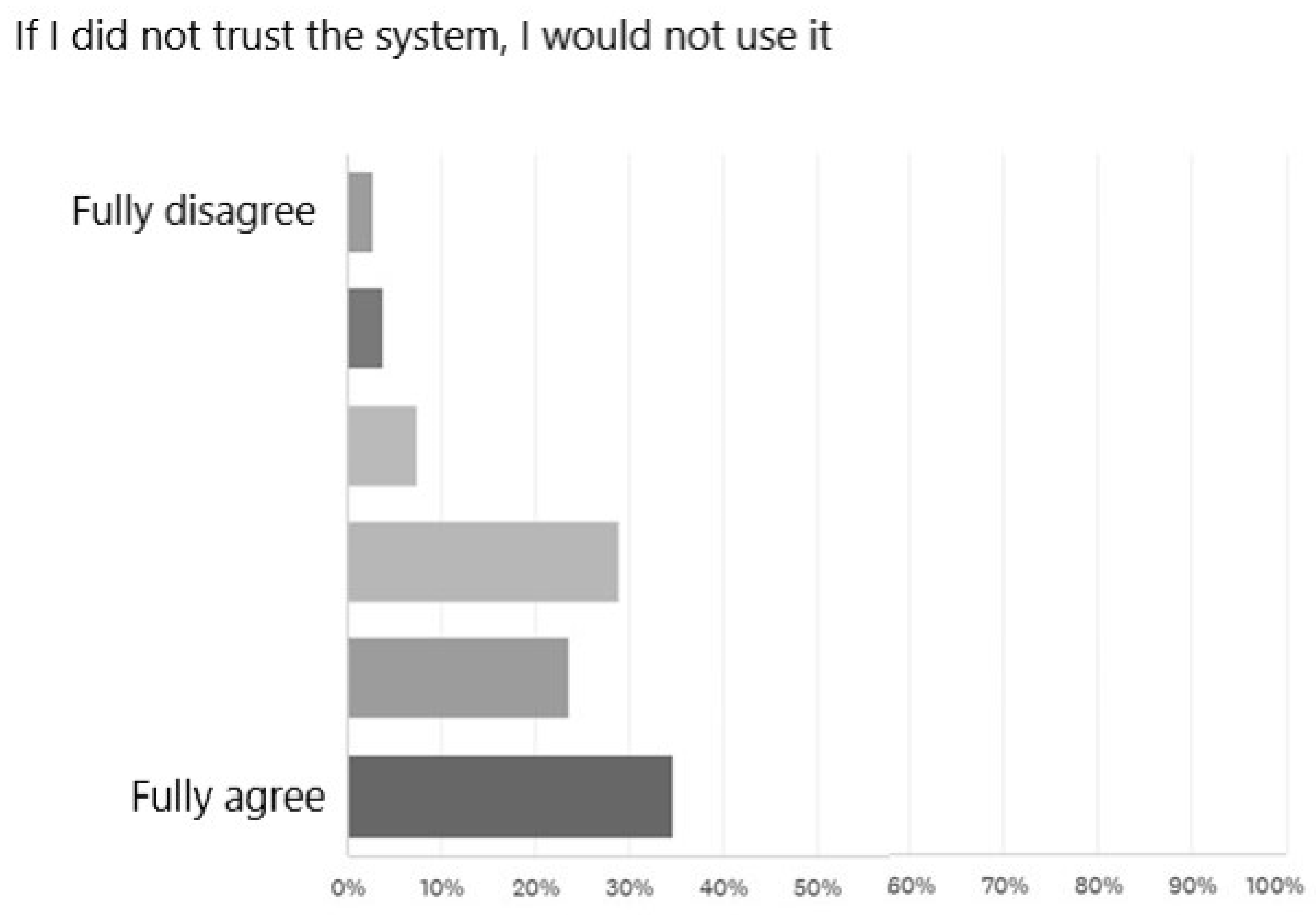

This is supported by the finding that 87.5% of respondents categorically state that they would not use an AV if they did not fully trust its operation (

Figure 3). This data aligns with recent research that underscores trust as a determining factor in the adoption of this technology. For example, according to research commissioned by HPI carried out in UK shows that only 22% of road users would trust a driverless car [

34].

The reasons for this distrust can be multiple. Consumers express significant concerns about safety, highlighting doubts about the ability of autonomous vehicles to handle complex driving situations. Aspects such as the interpretation of unforeseen situations, interaction with human drivers, and ethical dilemmas in decision-making are fundamental in this perception [

35].

The study delved into the specific factors that determine user trust in AVs. The results reveal that this trust is built on several fundamental pillars, including:

Privacy and data protection: Respondents expressed a strong concern for the security of their personal information. "Ensuring that my privacy is fully respected" emerged as a key priority.

Official certification: Trust is significantly reinforced when the vehicle "is certified and approved for use in the market", which underscores the importance of having institutional endorsements.

Control over personal data: Participants highly value "having the ability to decide who can access my data" and "having control over who can share my data with third parties" This reflects a desire for autonomy and transparency in the handling of information.

Technical reliability: The expectation that the vehicle "has a very low error rate, guaranteeing its reliability" is crucial for generating trust.

Despite these factors that could foster trust, a significant level of skepticism persists. 68.75% of participants believe that the decisions taken by AVs could have negative consequences. This data reveals a tension between the recognition of the potential benefits of technology and concern about its possible risks.

This duality in perception underscores the complexity of the challenge faced by developers and regulators of AVs. On one hand, they must address specific concerns about privacy, certification, and reliability. On the other, they need to work on the general perception of safety and reliability of the technology to mitigate fears about possible negative consequences.

As a final aspect, it is interesting to highlight which aspects linked to trust are the ones that seem most feasible to influence, understanding that those issues with a smaller number of people in disagreement (12.25%) indicate aspects where users would be more willing to trust AVs if certain conditions are met.

This suggests key areas where manufacturers and regulators could focus to increase trust and, therefore, the adoption of AVs. Analyzing the data, several lines of work can be identified as main areas:

Certification and data security: 19% of people disagree with trusting AVs if their use is certified and if data security is guaranteed. This suggests that official certification and data protection are crucial aspects.

Privacy: 22% of people disagree with trusting AVs if their privacy is assured, indicating that the protection of personal information is a significant concern.

Research and testing: 22.5% of people disagree with trusting AVs if they have been subjected to research and testing, which highlights the importance of transparency in the development and evaluation of these vehicles.

3.3. Trust by Demographic Group

Analyzing the distribution of the trust variable across the four age groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test, the results suggest that all individuals responded similarly to the trust questions, regardless of age (p=.90). The majority of values for this variable are between 0 and 1, indicating that most people agree that they would only trust autonomous vehicles if the conditions mentioned in the questionnaire are met.

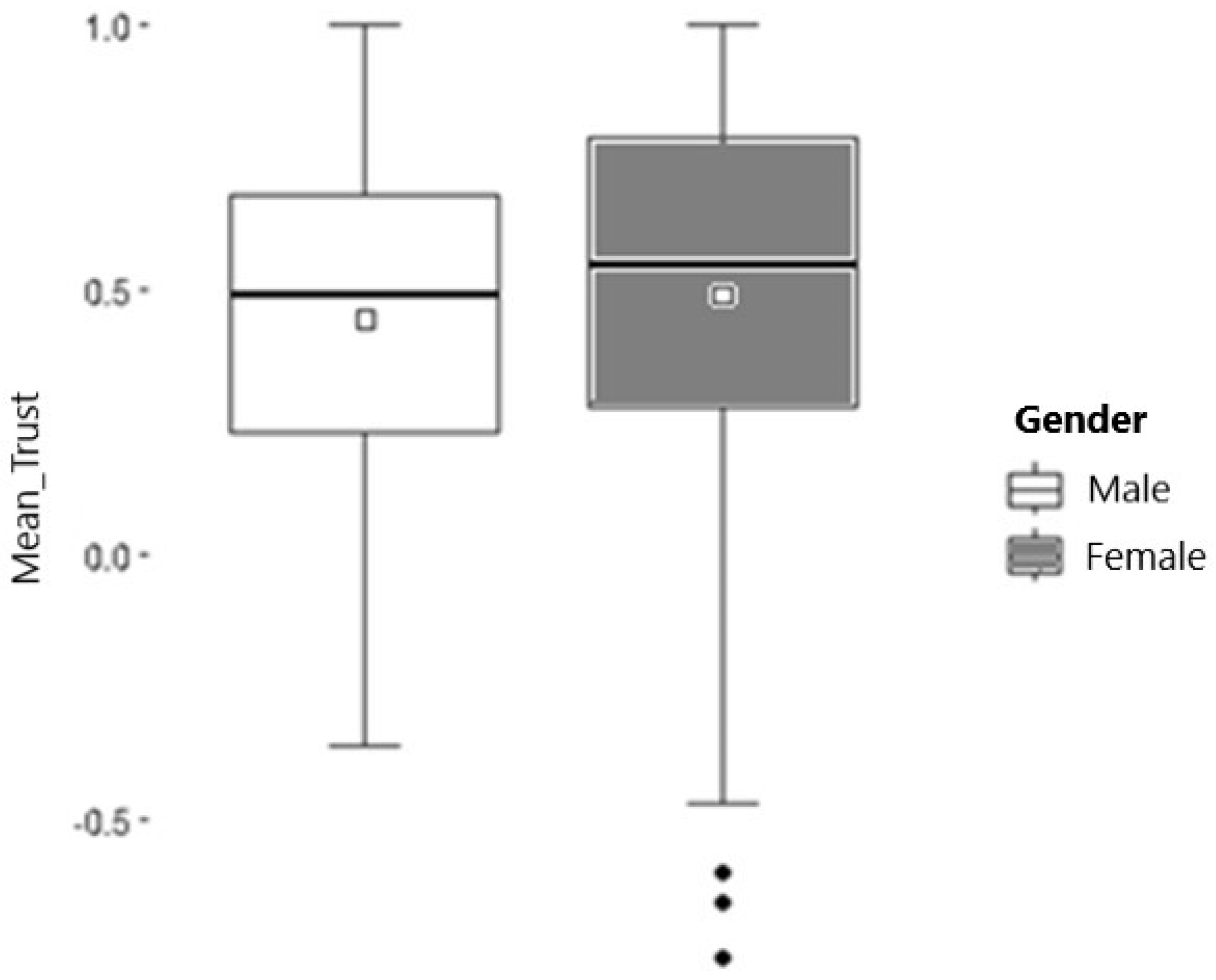

Analyzing the distribution of the trust variable across the two gender groups using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the results suggest that the two gender groups distribute similarly, but with a

p-value of .07 indicating that there is significant difference between the minimum values and the values in the first quartile. In other words, there are women that distrust AVs and are outliers in trust level, and in general women seem to take outlier values (

Figure 4).

Considering education level, results suggest that this variable only follows a normal distribution if limited to people with basic education. It also suggest that people with basic education tend to trust AVs less (x̅=0.34) if conditions from the questionnaire are not met.

Analyzing the distribution of the trust variable across the four income groups, results suggest that trust has a normal distribution among participants with a lower income level (p=.55). People with low income tend to trust AVs less (x̅=0.39).

Analyzing the distribution of the trust variable by driver's license possession, the results suggest that people without a driving licence tend to trust AVs less. however, it can also be seen that there were participants with a driving license that also presented low levels of trust.

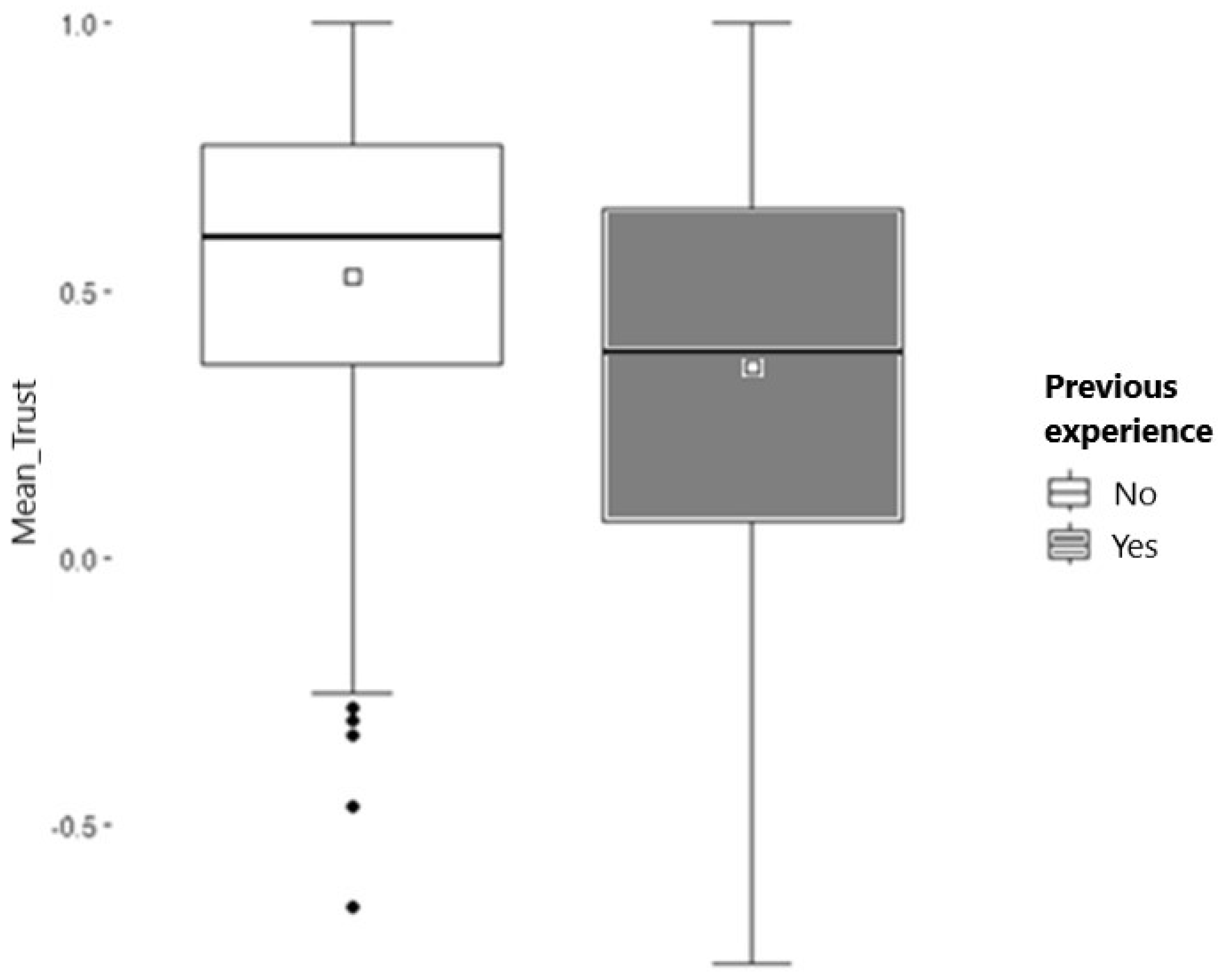

Finally, regarding previous experience with AVs, results showed that trust did not followed a normal distribition in either group, which also indicated disparaties (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The developed study reveals a complex panorama in relation to AVs. The results show a clear dichotomy between the enthusiasm for the potential benefits of this technology and significant apprehensions about its implementation and use. This research not only highlights the main expectations of users but also underscores the crucial importance of trust as a determining factor in the adoption of AVs.

This dichotomy highlights the need for a thorough understanding of the public's perception of Avs consdiering factors such as cultural values and existing infrastructure which can significantly influence adoption rates.

Expectations

Users prioritize aspects such as safety, comfort, and respect for the environment. However, critical issues such as technical reliability and adequate legal regulation are perceived as less relevant, which could reflect a lack of understanding about the technical and regulatory challenges facing this technology. As highlighted in the introduction, AVs are expected to improve the environment and increase safety on the roads [

6]. So it would be logical that these factors were high in users expectations.

This apparent contradiction warrants attention from both industry stakeholders and regulatory bodies. On one hand, there is a need to develop effective educational campaigns to address this knowledge gap. Informative initiatives could highlight the critical role of regulation in ensuring AV safety, security, and ethical operation.

Trust as a Key Factor

Trust is positioned as a decisive element for the adoption of autonomous vehicles. 84.5% of respondents consider trust essential to use them, while 87.5% state that they would not use them if they did not fully trust their operation. This reflects the fact that initial trust perceptions are a critical concern, as indicated by [

23].

The elements that generate trust include: Guarantees of privacy and control over personal data, official certification for use and low error rate that ensures reliability. However, as noted previously, these dimensions of trust are influenced by a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, social, and contextual factors.

The main areas that represent opportunities to increase trust and, potentially, the adoption of AVs indicate that manufacturers and regulators should focus on: 1) establishing rigorous and transparent certification systems, 2) implementing robust data security and privacy measures, 3) conducting and communicating extensive research and testing, and 4) providing users with control over their personal data.

In this regard, it has been previously highlighted how some authors noted that initial trust in AV design and deployment will also require a stakeholder-centered design process being of great importance for companies such as automotive manufacturers, technology companies, and research institutions.

From all that is stated, it becomes clear that the results and conclusions reinforce the paramount importance of transparency, security, and reliability in the AV ecosystem. By prioritizing these elements, stakeholders can work to build trust among potential users and contribute to the successful integration of AVs into society.

By comparing these findings with previous studies from other countries, we aim to contextualize the role of cultural and regulatory differences in AV trust. Former research has shown that trust in AVs is strongly linked to governmental regulation and public involvement in decision-making processes [

36,

37], while emerging evidence suggests a stronger emphasis on ethical considerations and privacy concerns [

38].

Concerns About Autonomous Decisions

A considerable percentage, 68.75% of participants fear that the decisions made by these vehicles could have negative consequences. This finding is important because highlights the need for transparency in algorithms and decision-making processes. The design of AI driven applications is of paramount importanceto facilizate user-experience. Therefore, more detailed research needs to be done on ethics and their influence in consumer decision-making. This could be addressed by increasing education and communication to users about (anticipatory) ethical considerations, building trust on the AVs [

39].

5. Conclusions

The perception of reliability is closely linked to the existence of a robust regulatory framework. This implies that governments must prioritize the development of clear laws and certification mechanisms to ensure safety and privacy. Additionally, regulatory efforts should align with broader smart mobility strategies, ensuring that AVs integrate seamlessly into existing public transport infrastructures and urban mobility networks.

There is a gap between public expectations and technical knowledge about autonomous vehicles. Educational campaigns, for example integrating AV education into broader sustainable mobility initiatives, could help to mitigate unfounded concerns and encourage informed adoption.

Concern for negative consequences highlights the importance of integrating ethical principles in the design of these systems. This includes ensuring fair decisions in critical situations and avoiding biases in algorithms as far as society must start considering ethical and moral values in their decisions [

6], but also how AV deployment will impact accessibility, spatial equity, and transit-oriented development.

Given the widespread skepticism, it is likely that the integration of autonomous vehicles will be progressive, coexisting with conventional vehicles for a long period. This will require strategies to manage this transition. Cities must therefore develop adaptive urban policies that facilitate a gradual shift toward intelligent transport systems, ensuring AVs complement rather than compete with public transit.

In the specific context of Spain, the government is actively working to modernize infrastructure to support the deployment of AVs [

6]. Thus, it is of especial importance that future research analyses the impact of these public efforts towards better communications and public expectaitons. Moreover, understanding AV adoption within the broader framework of sustainable urban mobility can help policymakers design interventions that maximize the benefits of AVs while maintaining efficient, accessible, and environmentally friendly public transportation systems.

In summary, although expectations toward autonomous vehicles are high in terms of comfort and sustainability, trust emerges as a central challenge that must be addressed through regulation, certification, and public education. Addressing these aspects could significantly increase consumer trust in autonomous vehicles, which in turn could translate into a greater willingness to purchase and use them.

This discussion must be considered in the context of the survey limits. For example, even if the platform employed by the survery facilitates representation across the entire Spanish territory, it is possible that those regions with lesser access to new technologies may not be fully represented. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the survey limits our ability to infer causal relationships or to capture changes in perceptions over time. Moreover, all data was derived from self-reporting measures, and the results might present biases inherent to this method.

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to track how public attitudes toward AVs evolve with increased exposure and real-world experience. Furthermore, qualitative research methods, such as focus groups and in-depth interviews, can provide richer insights into the nuanced factors that influence trust and acceptance, addressing potential biases. Additionally, more focused research needs to be done about privacy concerns, as data on specific concerns among the spanish population and their level of awarenes is still scarce, also highlighted by others studies [

40].

Finally, a particularly concerning finding was that individuals without prior experience with AVs expressed greater trust in the technology than those with experience. This presents a significant challenge, as early adopters, who often drive technological advancement and adoption, appear to be less convinced of the current state of AV technology. Consequently, additional research is needed to understand the reasons underlying this skepticism among experienced users and to identify strategies to ensure experienced users become advocates rather than detractors [

24]. This aspect is particularly relevant for the transition to smart mobility solutions, as early adopters often play a crucial role in shaping public narratives around new transportation technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and J.P.; methodology, I.P.; formal analysis and data curation, I.P; investigation, J.P. and I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, J.P.; visualization, I.P.; supervision, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the Centre for Technological Development and Innovation E.P.E. (CDTI), under the European Union's Recovery and Resilience Mechanism (RRM). Grant number CER-20231011, recognised as a CERVERA Network of Excellence.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any time. By completing the survey, participants provided their implicit consent to participate in the research.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed in this study is stored in a public repository [10.5281/zenodo.14967567]. For other inquiries regarding the dataset, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable contribution of Sofía Díez, external data science professional who provided expert input in advanced statistical methodologies and data management to enhance the rigor and depth of our findings. While not directly involved in the design or conceptualization of the research, her technical expertise and support was instrumental in ensuring the robustness of the data treatment processes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADAS |

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| AVs |

Autonomous Vehicles |

References

- Junaid, M.; Ferretti, M.; Marinelli, G. Innovation and Sustainable Solutions for Mobility in Rural Areas: A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Delfa, A.; Han, Z. Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narisetty, V. S. C. P.; Maddineni, T. Revolutionizing mobility: The latest advancements in autonomous vehicle technology. arXiv 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.20688 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Han, Z.; Ruan, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, H.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, J. Active Collision-Avoidance Control Based on Emergency Decisions and Planning for Vehicle–Pedestrian Interaction Scenarios. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Autonomous vehicle implementation predictions: Implications for transport planning. Victoria Transport Policy Institute 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lanuza García, A. Vehículo autónomo y conectado: casos de uso, pronósticos de adopción y adaptación de la infraestructura. Rev. Digit. Cedex 2023, 202, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Patel, R. An Exploratory Analysis of Crashes Involving Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Transportation & Development, 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784484883.030 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Penmetsa, P.; Adanu, E. K.; Wood, D.; Wang, T.; Jones, S. L. Perceptions and expectations of autonomous vehicles – A snapshot of vulnerable road user opinion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 143, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L. D. Sustainable mobility: A vision of our transport future. Nature 2013, 497, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K. A.; Bashir, M. Trust in Automation: Integrating Empirical Evidence on Factors That Influence Trust. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kim, M.-Y. Promoting Sustainable Transportation: How People Trust and Accept Autonomous Vehicles—Focusing on the Different Levels of Collaboration Between Human Drivers and Artificial Intelligence—An Empirical Study with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling and Multi-Group Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, S.; Sisiopiku, V. P.; Mason, J. R.; Yang, W.; Hwangbo, S.-W.; McKinney, B.; Li, Y. Experience of drivers of all age groups in accepting autonomous vehicle technology. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 28, 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboucha, C. J.; Ishaq, R.; Shiftan, Y. User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 78, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shladover, S. E. Opportunities, Challenges, and Uncertainties in Urban Road Transport Automation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, R.; Riley, V. Humans and Automation: Use, Misuse, Disuse, Abuse. Hum. Factors 1997, 39, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, K. J.; Fischer, J. E.; Clark, J. R.; Bodenmann, A.; Galvez Trigo, M. J.; Brito, M. P.; Ramchurn, S. D. Trustworthy UAV Relationships: Applying the Schema Action World Taxonomy to UAVs and UAV Swarm Operations. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 39, 4042–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzindolet, M. T.; Peterson, S. A.; Pomranky, R. A.; Pierce, L. G.; Beck, H. P. The role of trust in automation reliance. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 58, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D.; See, K. A. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1518/hfes.46.1.50_30 (accessed on 16 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D.; Moray, N. Trust, control strategies and allocation of function in human-machine systems. Ergonomics 1992, 35, 1243–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, S.; Smids, J. The Ethics of Accident-Algorithms for Self-Driving Cars: an Applied Trolley Problem? Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2016, 19, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.; Forster, Y.; Hergeth, S.; Kraus, J.; Payre, W.; Wintersberger, P.; Martens, M. Trust in automated vehicles: constructs, psychological processes, and assessment. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1279271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandsart, D.; Cornet, H.; Gkemou, M. Stakeholders’ Engagement in Shared Automated Mobility: A Comparative Review of Three SHOW Approaches. In Shared Mobility Revolution; Cornet, H., Gkemou, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, K. E.; Chen, J. Y. C.; Szalma, J. L.; Hancock, P. A. A Meta-Analysis of Factors Influencing the Development of Trust in Automation: Implications for Understanding Autonomy in Future Systems. Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benk, M.; Kerstan, S.; von Wangenheim, F. Twenty-four years of empirical research on trust in AI: a bibliometric review of trends, overlooked issues, and future directions. AI Soc. 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-02059-y (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hick, S.; Biermann, H.; Ziefle, M. How deep is your trust? A comparative user requirements’ analysis of automation in medical and mobility technologies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Md Nordin, S.; bin Bahruddin, M. A.; Ali, M. How trust can drive forward the user acceptance to the technology? In-vehicle technology for autonomous vehicle. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Ji, Y. G. Investigating the importance of trust on adopting an autonomous vehicle. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2015, 31, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lécureux, B.; Bonnet, A.; Manout, O.; Berrada, J.; Bouzouina, L. Acceptance of Shared Autonomous Vehicles: A Literature Review of stated choice experiments. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2738–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, G.; Tan, R. Review and Perspectives on Human Emotion for Connected Automated Vehicles. Automot. Innov. 2024, 7, 4–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro, L.; Useche, S. A.; Alonso, F.; Lijarcio, I.; Bosó-Seguí, P.; Martí-Belda, A. Perceived safety and attributed value as predictors of the intention to use autonomous vehicles: A national study with Spanish drivers. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberger, C.; Spörrle, M.; Welpe, I. M. Not fearless, but self-enhanced: The effects of anxiety on the willingness to use autonomous cars depend on individual levels of self-enhancement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 116, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboz, A.; Mourtzouchou, A.; Grosso, M.; Kolarova, V.; Cordera, R.; Nägele, S.; Alonso Raposo, M.; Krause, J.; Garus, A.; Eisenmann, C.; dell'Olio, L.; Alonso, B.; Ciuffo, B. Exploring the acceptance of connected and automated vehicles: Focus group discussions with experts and non-experts in transport. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizsik, N.; Sipos, T. Social Perception of Autonomous Vehicles. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2023, 51, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HPI. Driverless Cars Research UK: Shifting Public Attitudes Towards Autonomous Vehicles. Available online: https://www.hpi.co.uk/content/motoring-news/driverless-cars-research-uk/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Rhim, J.; Lee, J. H.; Chen, M.; Lim, A. A Deeper Look at Autonomous Vehicle Ethics: An Integrative Ethical Decision-Making Framework to Explain Moral Pluralism. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 632394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordhoff, S.; de Winter, J. C. F.; Kyriakidis, M.; van Arem, B.; Happee, R. Acceptance of driverless vehicles: Results from a large cross-national questionnaire study. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, H.; Lee, C.; Brady, S.; Fitzgerald, C.; Mehler, B.; Reimer, B.; Coughlin, J. F. Autonomous vehicles and alternatives to driving: Trust, preferences, and effects of age. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 96th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 8–12 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaf, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Javed, A. R.; Saba, I.; Krichen, M.; Majeed, S.; Raza, A. Connected and Automated Vehicles: Infrastructure, Applications, Security, Critical Challenges, and Future Aspects. Technologies 2023, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghzare, S.; Campos, J. L.; Bak, K.; Mihailidis, A. Older adults' acceptance of fully automated vehicles: Effects of exposure, driving style, age, and driving conditions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIS International Research. ¿Cuáles son las preocupaciones de los consumidores sobre los coches autónomos? Available online: https://www.sisinternational.com/es/pericia/industrias/investigacion-de-mercado-automotriz/cuales-son-las-preocupaciones-de-los-consumidores-sobre-los-coches-autonomos/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).