Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction–Collected Data

- -

- -

- -

- -

2. Results and Discussion

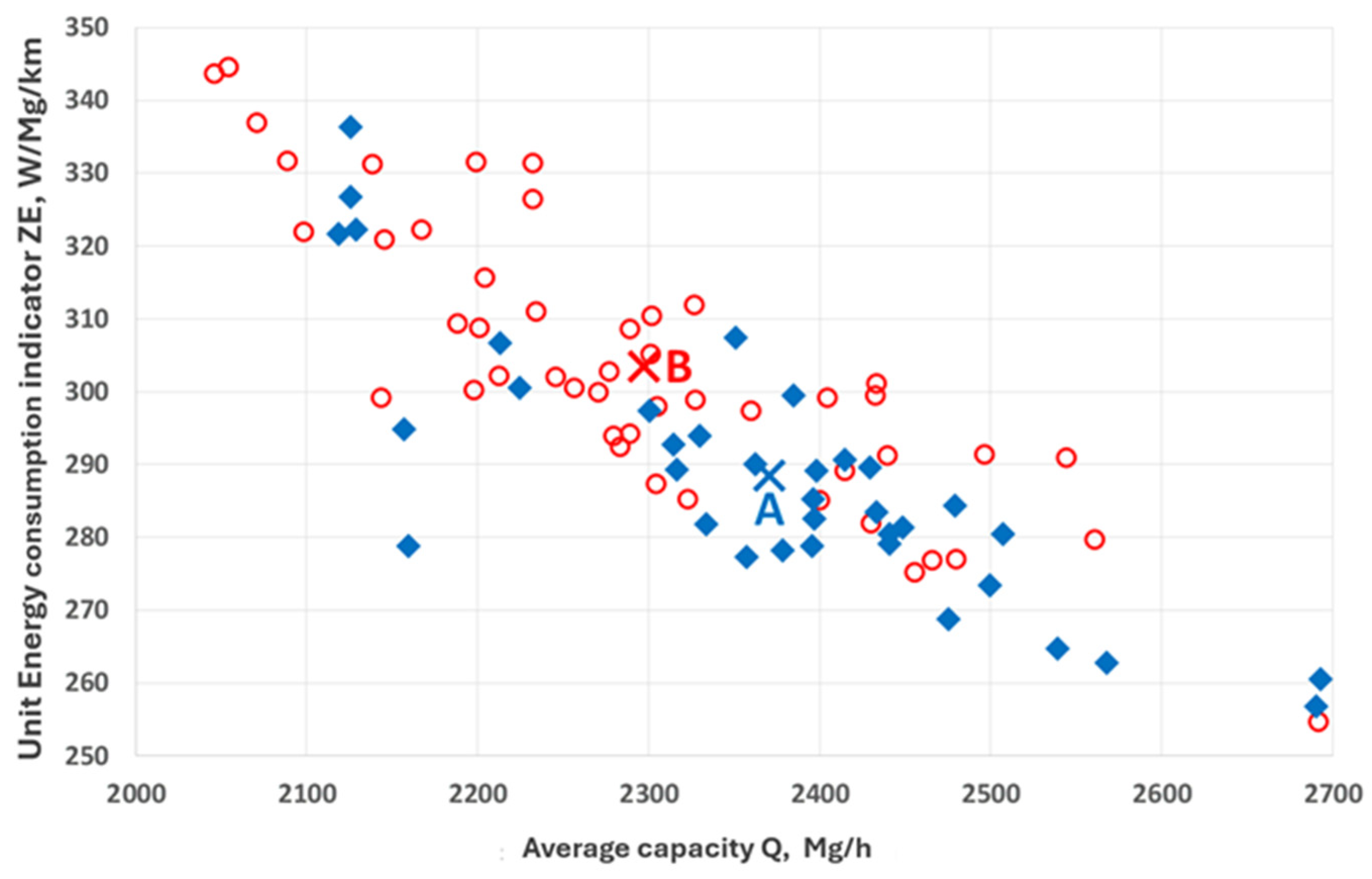

2.1. Comparison of the Average Monthly Capacities of the Tested Conveyors

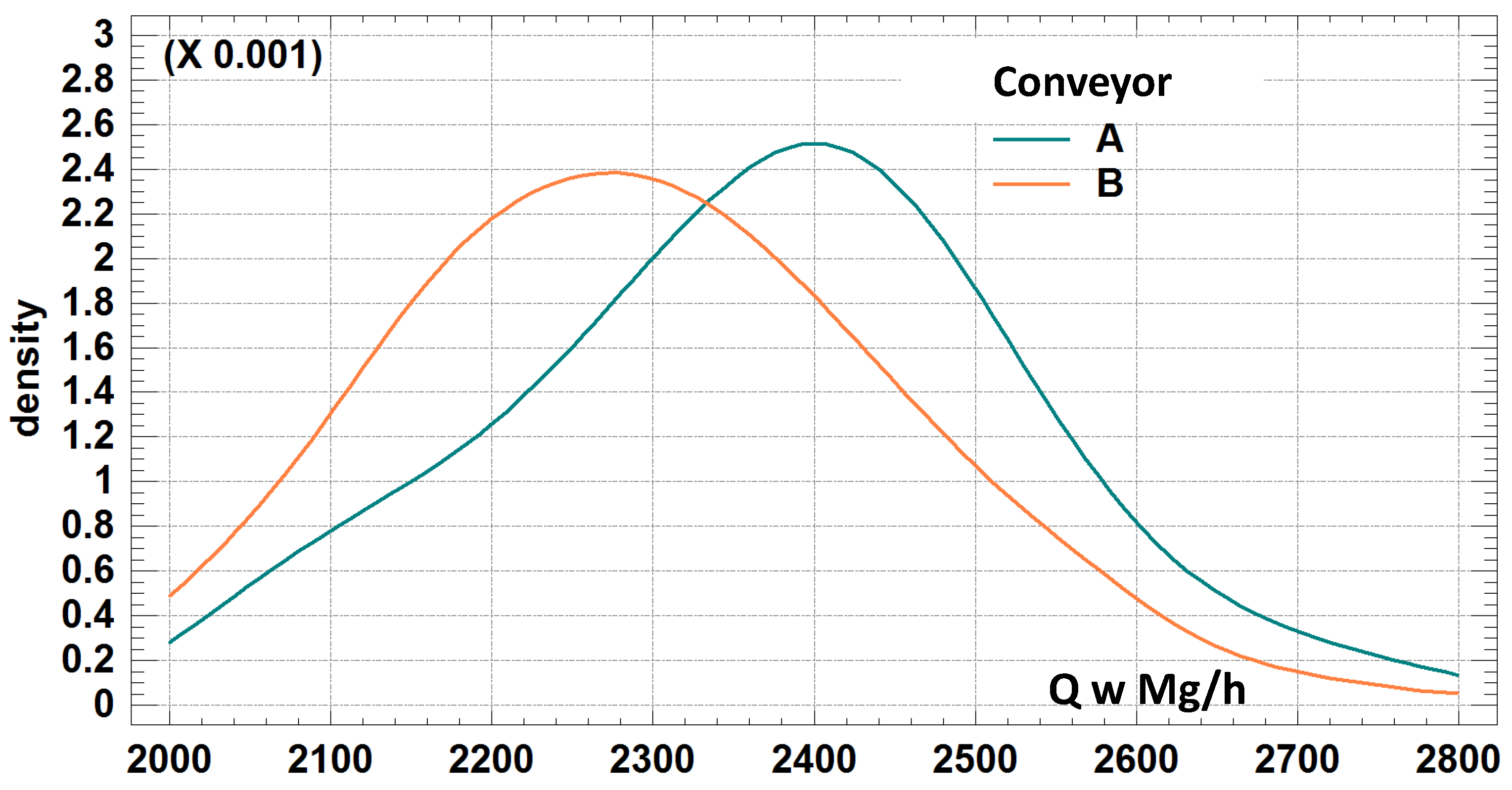

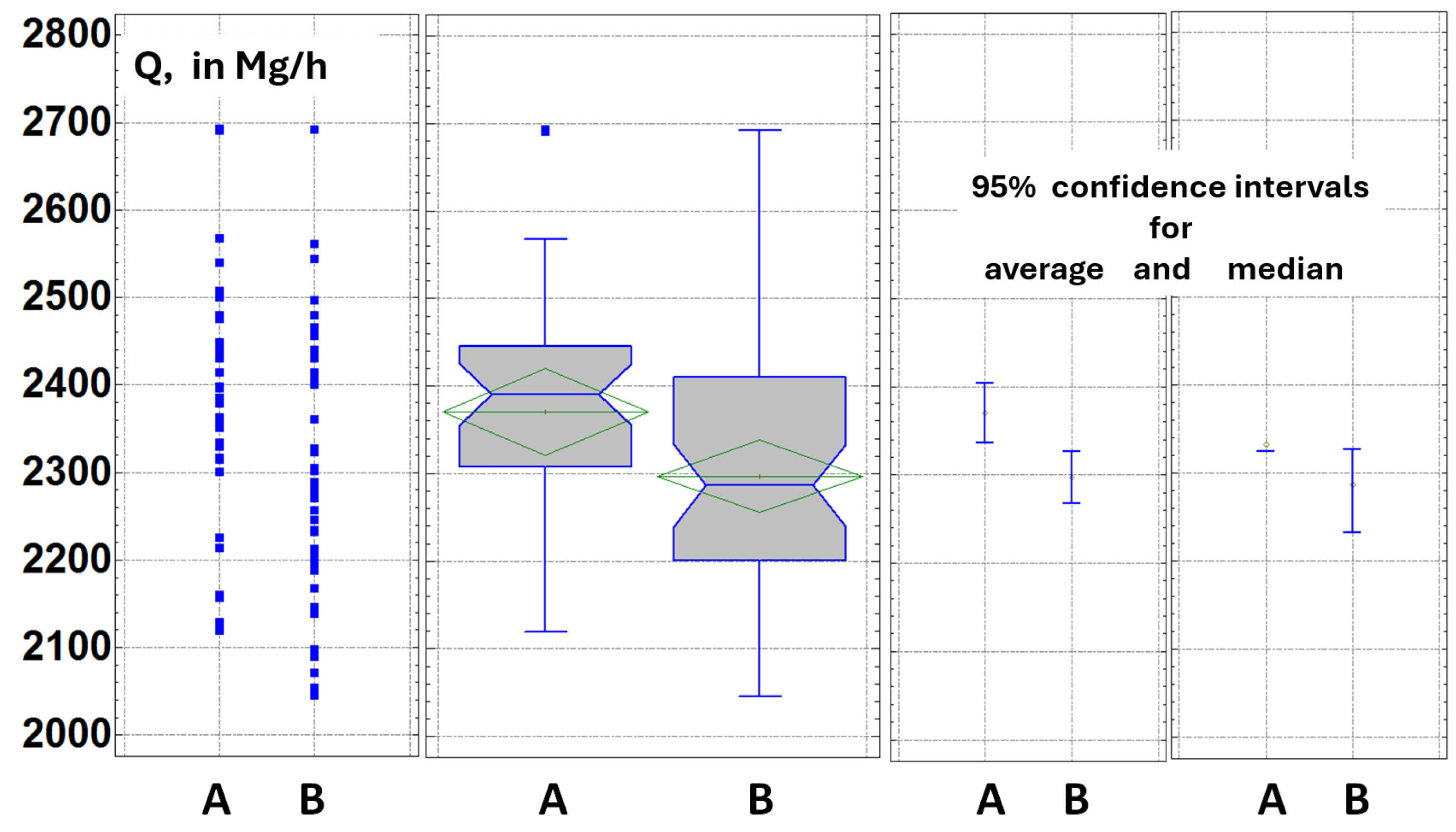

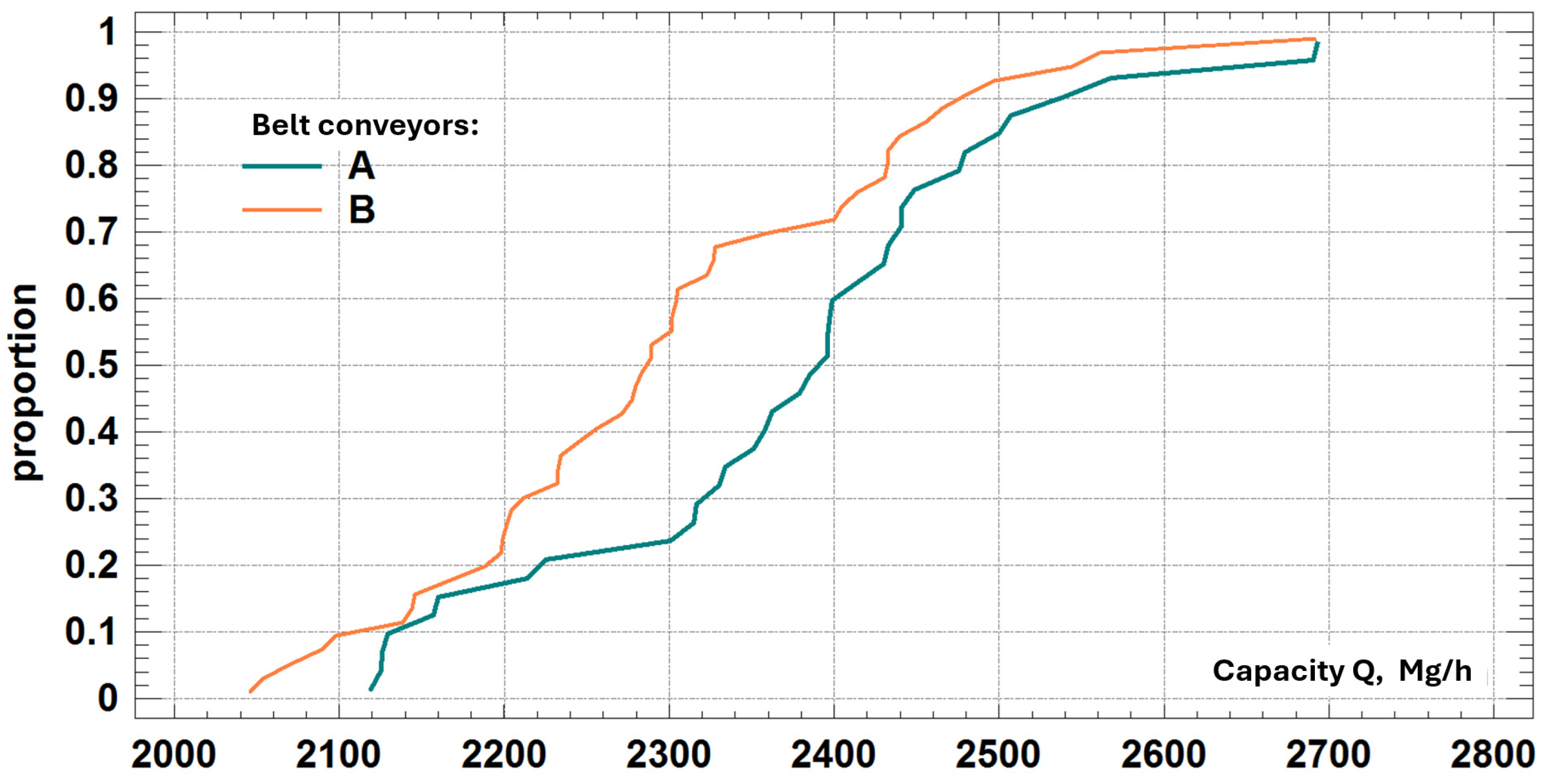

2.2. Statistical Analysis of Conveyor Capacities

| Descriptive Statistics | Conveyor A | Conveyor B | Absolute Difference | Relative Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Measurements | 36 | 48 | 12 | 33.33 |

| Mean in Mg/h | 2,370.56 | 2,296.89 | -73.67 | -3.11 |

| Median in Mg/h | 2390.60 | 2,286.37 | -104.23 | -4.36 |

| Geometric Mean in Mg/h | 2,366.14 | 2,292.63 | -73.51 | -3.11 |

| Harmonic Mean in Mg/h | 2,361.69 | 2,288.42 | -73.27 | -3.10 |

| Standard Deviation in Mg/h | 146.62 | 142.20 | -4.42 | -3.02 |

| Coefficient of Variation | 6.19% | 6.19% | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Standard Error in Mg/h | 24.437 | 20.525 | -3.912 | -16.01 |

| Variance in Mg2/h2 | 21,498.1 | 20,221.2 | -1276.9 | -5.94 |

| Minimum Capacity in Mg/h | 2119.17 | 2045.89 | -73.28 | -3.46 |

| Maximum Capacity in Mg/h | 2693.29 | 2692.01 | -1.28 | -0.05 |

| Range in Mg/h | 574.12 | 646.12 | 72.00 | 12.54 |

| Lower Quartile (Q1) in Mg/h | 2307.98 | 2200.30 | -107.68 | -4.67 |

| Upper Quartile (Q3) in Mg/h | 2445.07 | 2409.83 | -35.24 | -1.44 |

| Interquartile Range in Mg/h | 137.10 | 209.53 | 72.44 | 52.84 |

| Skewness | 0.0178 | 0.4232 | 0.4053 | 2273.16 |

| Kurtosis | -0.0170 | 0.0559 | 0.0729 | -427.76 |

-

Consistent Variation:

- -

- The coefficient of variation was nearly identical (6.19%) for both conveyors despite differences in mean values.

- -

- The maximum capacities were almost the same (~2,693 Mg/h), while the minimum capacity was lower for Conveyor B.

-

Higher Dispersion in Conveyor B:

- -

- The range of fluctuations in Conveyor B’s capacity was 72 Mg/h higher than in Conveyor A (646.12 Mg/h vs. 574.12 Mg/h).

- -

- This wider range may be due to seasonal and operational factors, requiring further investigation.

-

Efficiency Distribution Differences:

- -

- Interquartile and intersextile ranges suggest a more concentrated distribution in Conveyor A, while Conveyor B exhibited greater dispersion at the extremes.

- -

- The kurtosis values suggest that both datasets approximate a normal distribution, though Conveyor A’s slight negative kurtosis (-0.017) contrasts with Conveyor B’s positive kurtosis (0.056).

- -

- Conveyor B exhibited stronger right-side skewness (0.42), indicating higher occurrences of lower-than-average capacities than Conveyor A (skewness = 0.017).

2.1.1. Statistical Significance of Differences in Monthly Average Capacities

- Confidence Intervals for Monthly Average Capacities

- Conveyor A: 2,370.56 ± 49.61 [2,320.95; 2420.17]

- Conveyor B: 2,296.89 ± 41.29 [2,255.59; 2338.18]

- ZE Difference: 73.67 ± 63.21 [10.47; 136.88]

- Student’s t-Test for Mean Comparison

- t-statistic: 2.31884

- P-value: 0.02289

- F-Test for Variance Comparison

- Conveyor A: 146.622 [118.92; 191.26]

- Conveyor B: 142.201 [118.38; 178.18]

- Variance Ratio: 1.0632

- 95% Confidence Interval for Variance Ratio: [0.57575; 2.0211]

- Mann-Whitney (Wilcoxon) Test for Median Comparison

-

Median Capacities:

- -

- Conveyor A: 2,390.6

- -

- Conveyor B: 2,286.37

-

Mean Ranks:

- -

- Conveyor A: 49.6111

- -

- Conveyor B: 37.1667

- W-statistic: 608

- P-value: 0.02092

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Distribution Compatibility

- DN Statistic: 0.3819

- K-S Statistic: 1.7323

- P-value: 0.00049

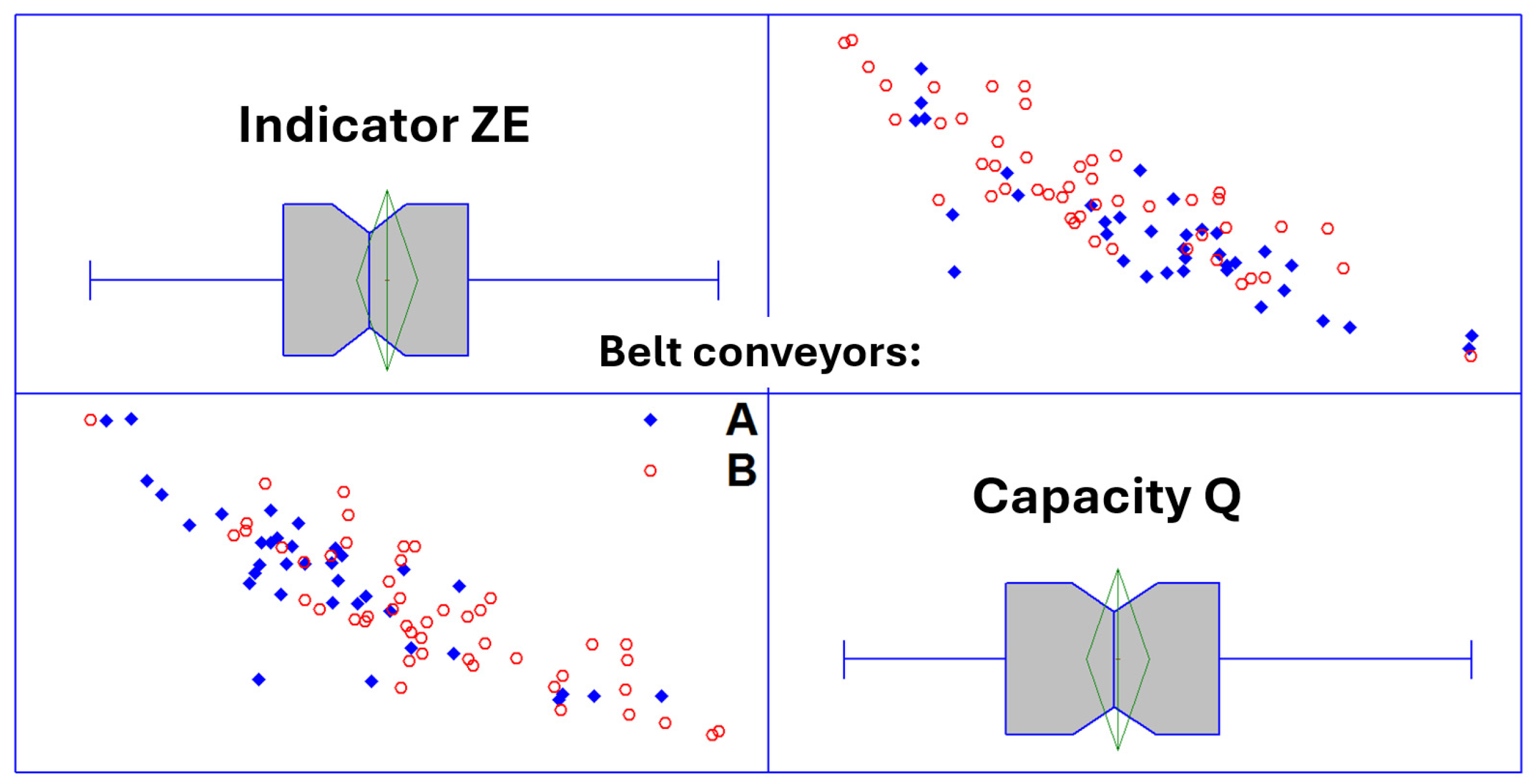

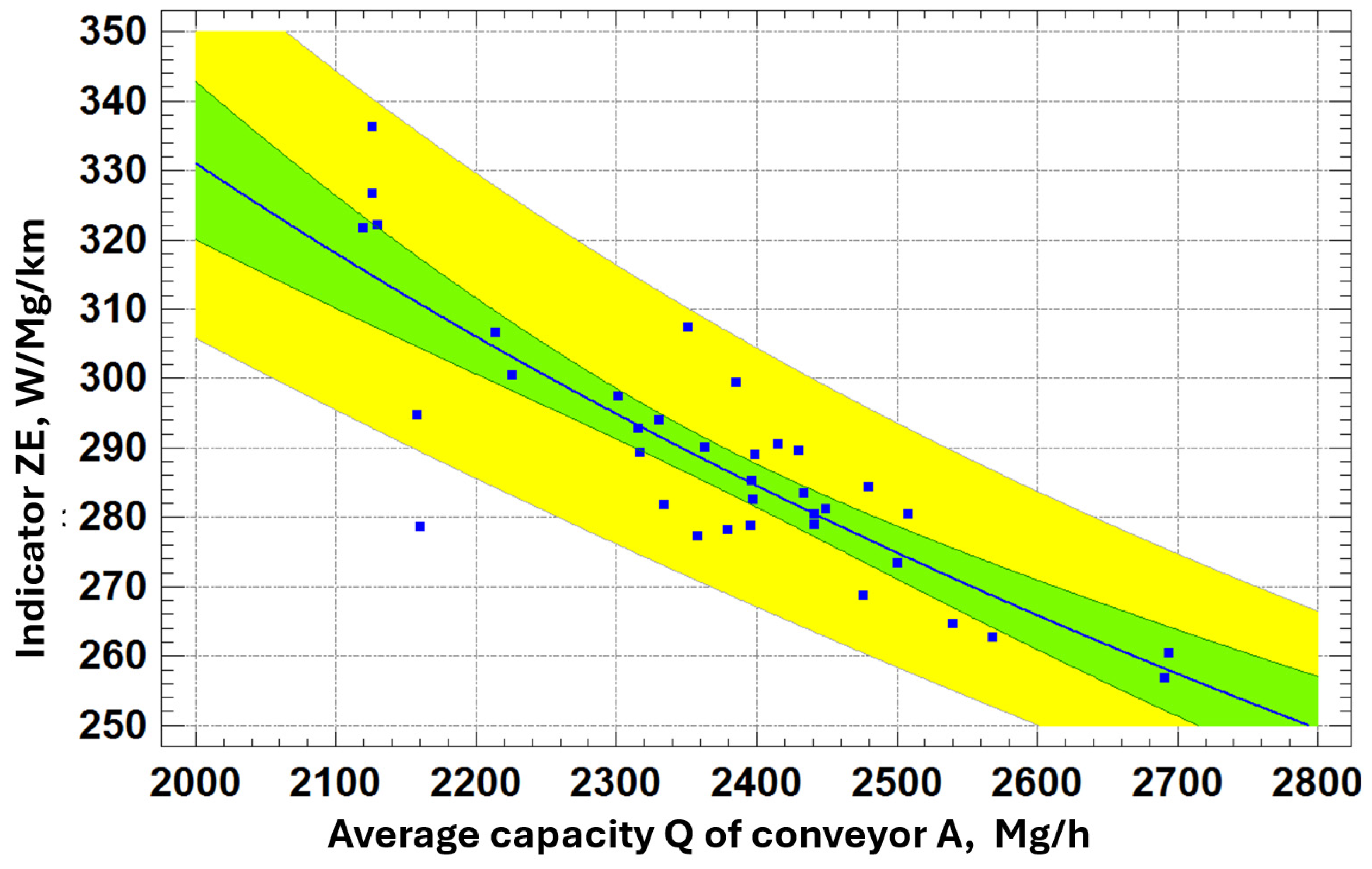

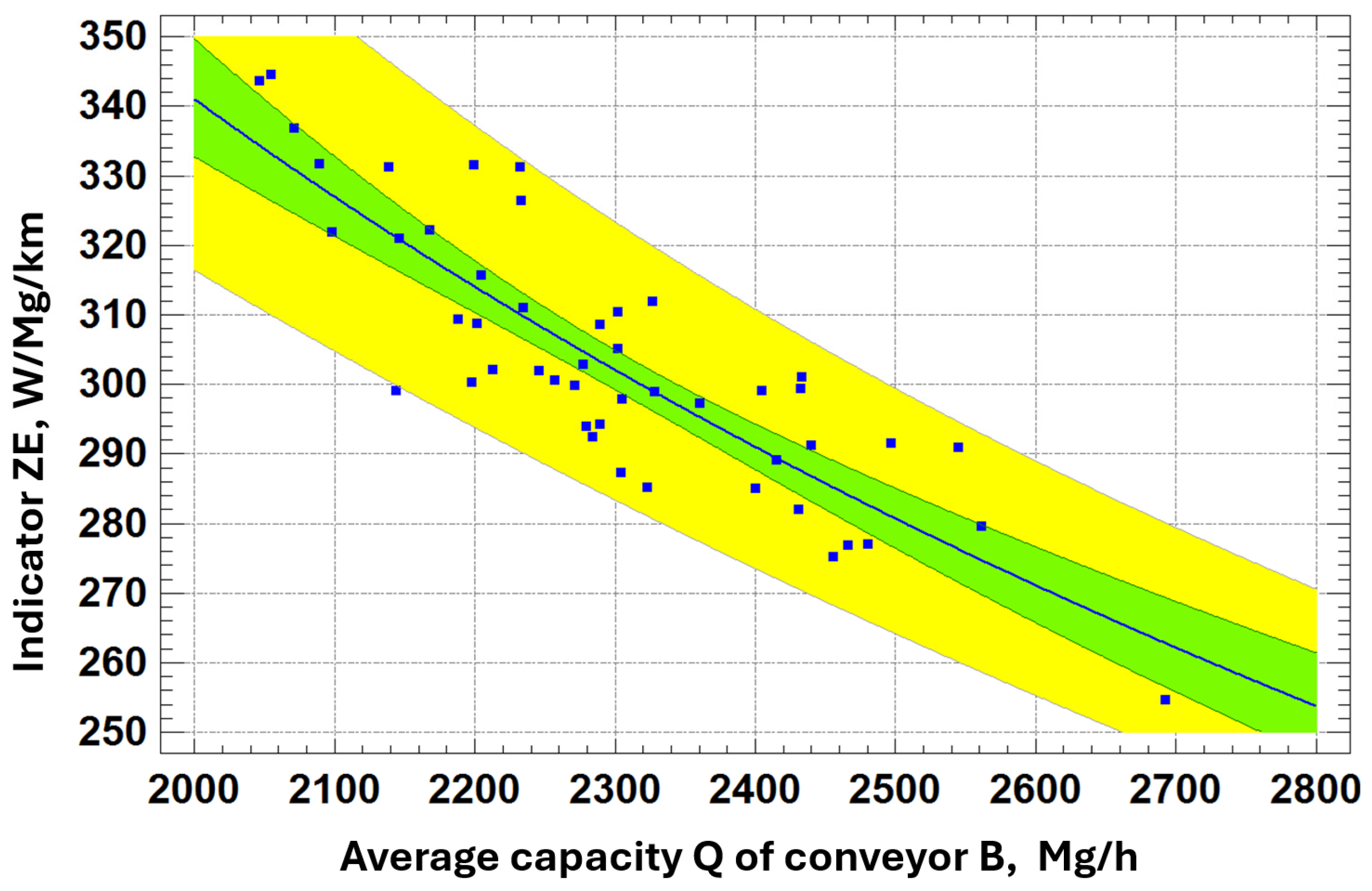

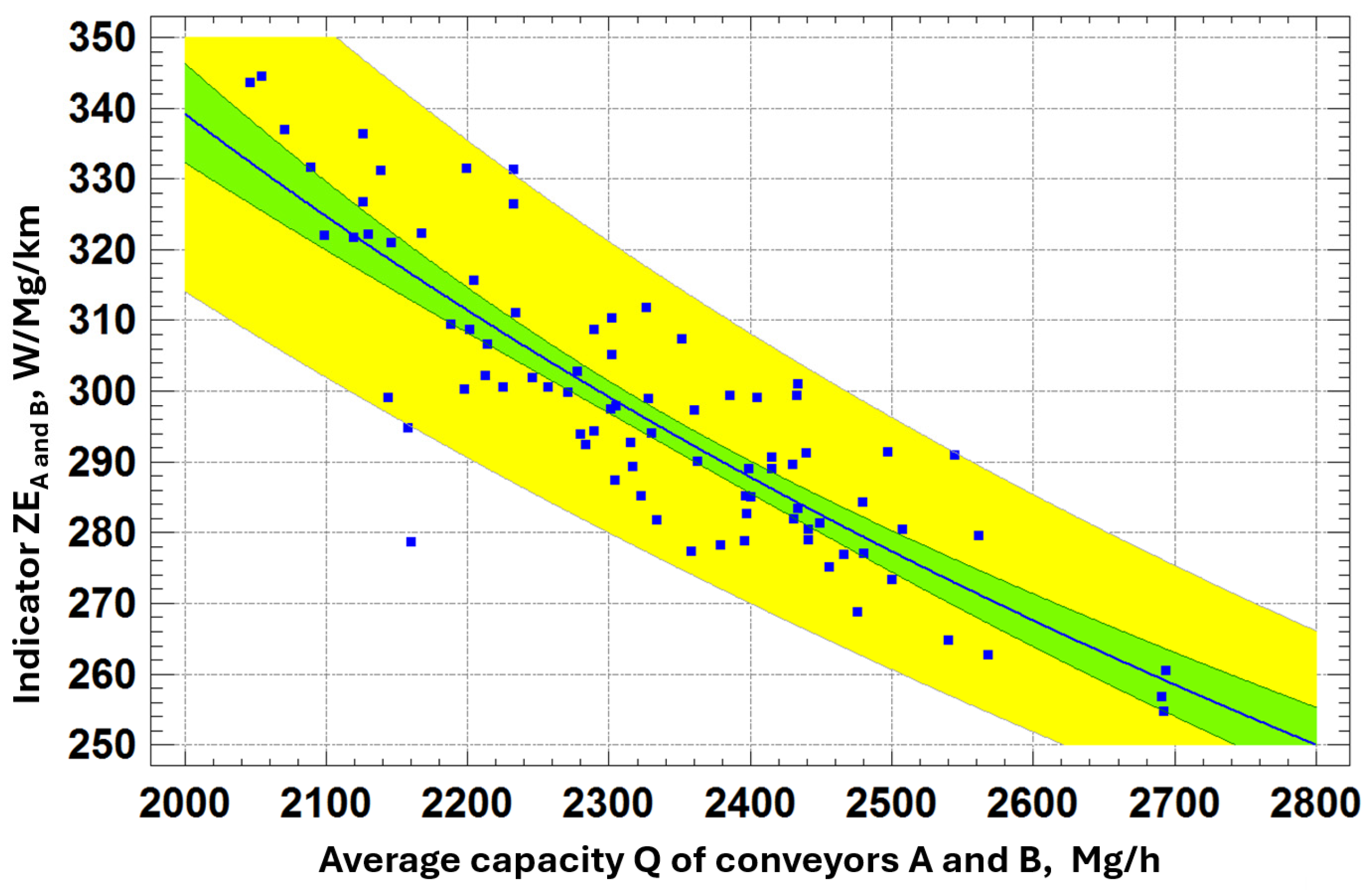

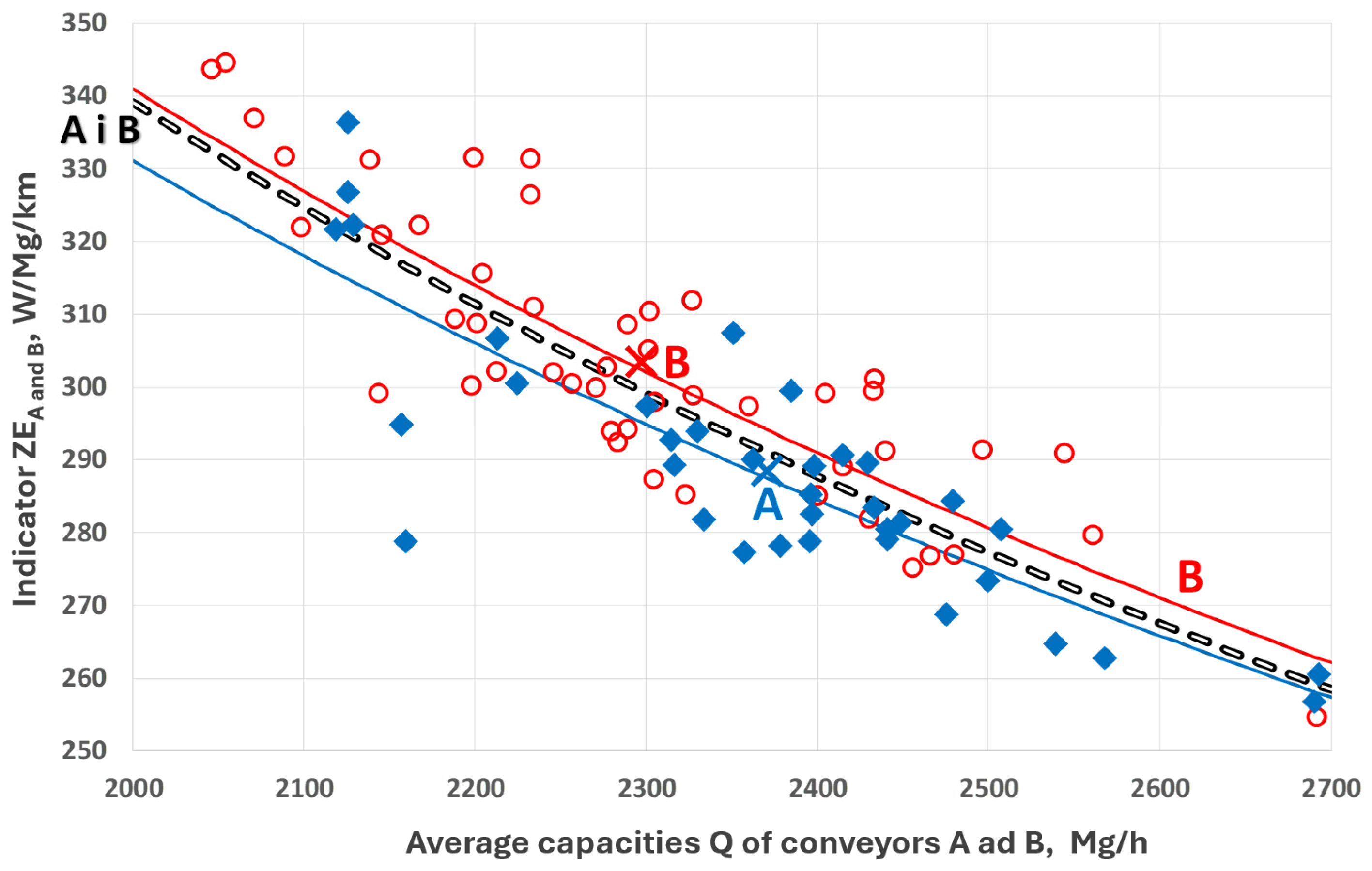

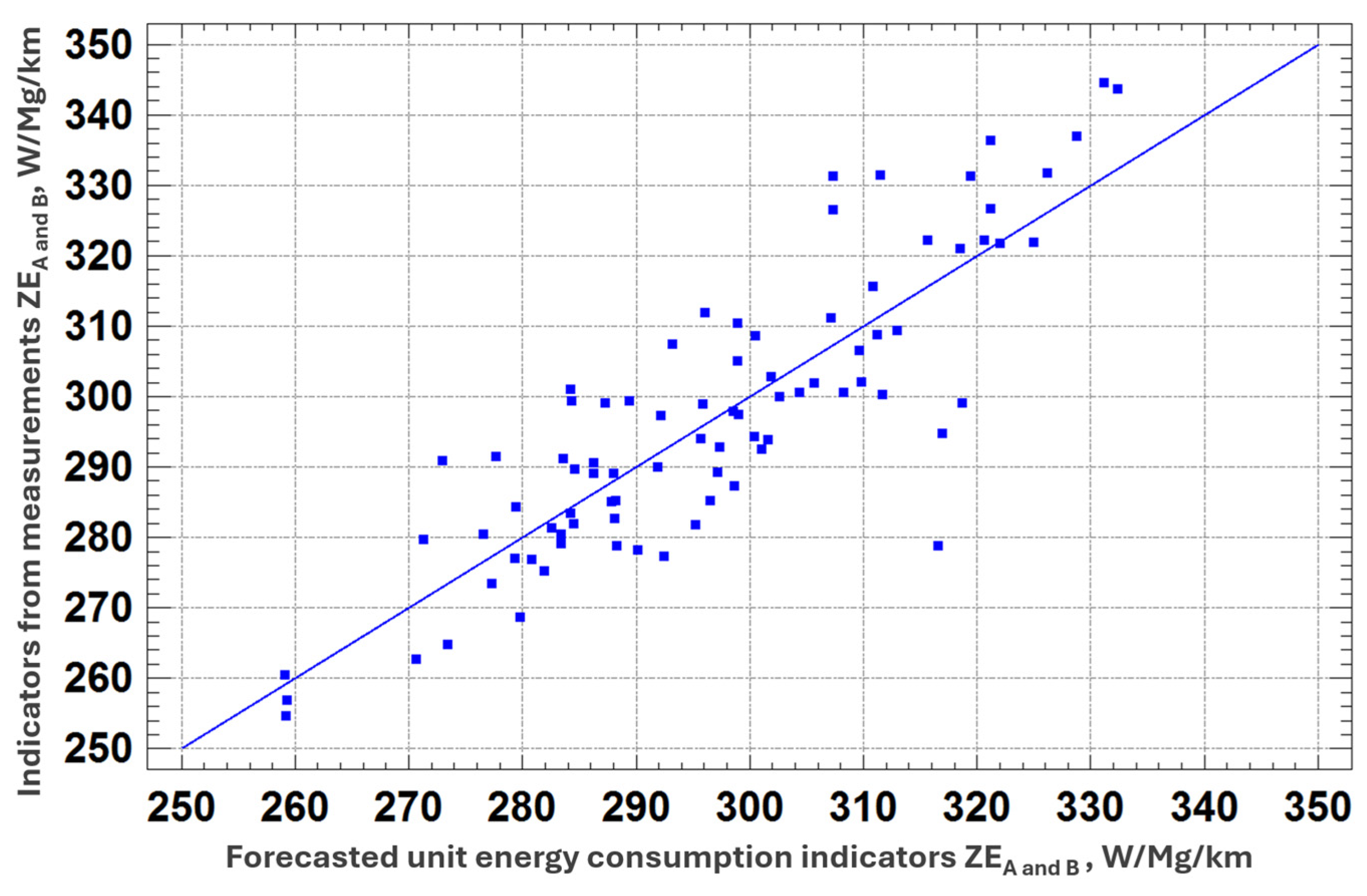

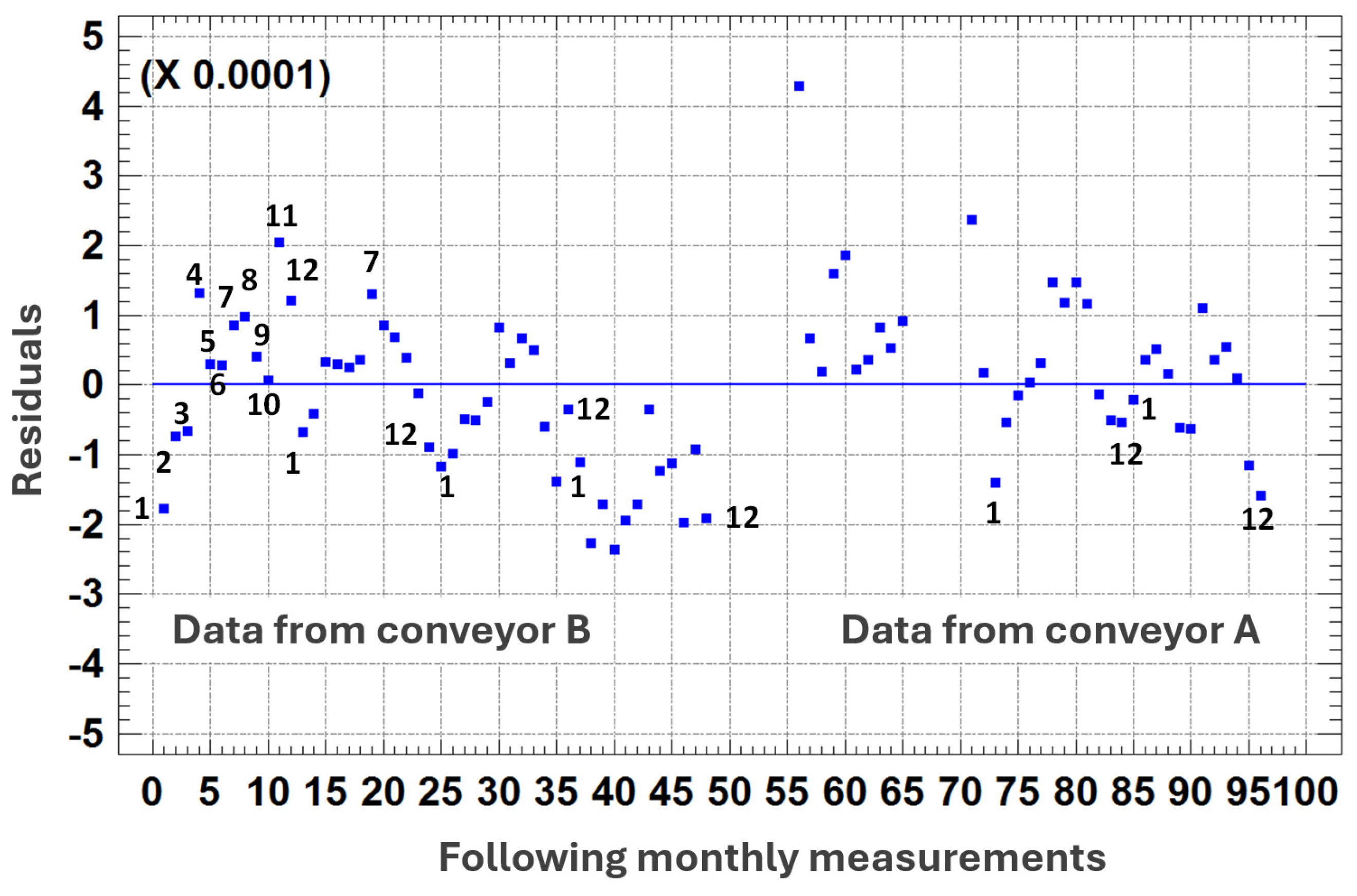

2.3. Regression of the Unit Energy Consumption Indicator ZE Against the Average Capacity of the Conveyor

- Correlation coefficient: 0.854862

- R-squared: 73.0789%

- R-squared (df corrected): 72.2871%

- Standard error of estimation: 0.0000796077

- Mean absolute error: 0.0000882741

- Durbin-Watson statistic: 0.909369 (P = 0.00001)

- Residual autocorrelation Lag 1: 0.335697

| Least squares method | Standard | Statistics | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Error | T | P | |

| Offset | 0.0005512 | 0.00030525 | 1.8057 | 0.0798 | |

| Slope | 0.000001235 | 1.2853 E-7 | 9.6070 | 0.0000 | |

| Variance Analysis | |||||

| Source | Sum of squares | Df | Medium squares | F-statyst. | Value P |

| Model | 0.0000011472 | 1 | 0.0000011472 | 92.30 | 0.0000 |

| The Rest | 4.22607 E-7 | 34 | 1.24296 E-8 | ||

| Together (Corr.) | 0.00000157 | 35 | |||

- Correlation coefficient: 0.86031

- R-squared: 74.012%

- Standard error of estimation: 0.00010734

- Mean absolute error: 0.000089

- Durbin-Watson statistic: 0.58731 (P = 0.0000)

- Residual autocorrelation Lag 1: 0.66312

| Least squares method | Standard | Statistics | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Error | T | P | |

| Offset | 0.00041227 | 0.00025337 | 1.6277 | 0.1105 | |

| Slope | 0.0000012602 | 1.10102 E-7 | 11.446 | 0.0000 | |

| Variance Analysis | |||||

| Source | Sum of squares | Df | Medium squares | F-statyst. | Value P |

| Model | 0.0000015094 | 1 | 0.0000015094 | 131.01 | 0.0000 |

| The Rest | 5.29975 E-7 | 46 | 1.15212 E-8 | ||

| Together (Corr.) | 0.000002039 | 47 | |||

- Correlation coefficient: 0.86312

- R-squared: 74.498%

- Standard error of estimation: 0.00011448

- Mean absolute error: 0.000088274

- Durbin-Watson statistic: 1.0102 (P = 0.0000)

- Residual autocorrelation Lag 1: 0.46853

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soofastaei, A.; Karimpour, E.; Knights, P., & Kizil, M. Energy-efficient loading and hauling operations. Energy efficiency in the minerals industry: best practices and research directions, 2018, 121-146. [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, C. M.; de Castro Neves, T.; Arroyo, C.; & Campos, P. Truck-and-loader versus conveyor belt system: an environmental and economic comparison. In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection-MPES, 2018 (pp. 307-318). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Carter, R. A. Designing Today’s Conveyor Systems for Tomorrow’s Needs. Engineering and Mining Journal, 2023, 224(10), 24-30.

- Leonida, C. Moving Material More Efficiently. Engineering and Mining Journal, 2023, 224(4), 32-37.

- Bodziony, P.; Patyk, M. The influence of the mining operation environment on the energy consumption and technical availability of truck haulage operations in surface mines. Energies, 2024, 17(11), 2654.

- Krysa, Z.; Bodziony, P.; Patyk, M. Exploitation of Mineral Resources in Conditions of Volatile Energy Prices: Technical and Economic Analysis of Low-Quality Deposits. Energies, 2024, 17(14), 3379.

- Rakhmangulov, A.; Burmistrov, K.; Osintsev, N. Multi-criteria system’s design methodology for selecting open pits dump trucks. Sustainability, 2024, 16(2), 863.

- He, D., Pang, Y., & Lodewijks, G. Green operations of belt conveyors by means of speed control. Applied Energy, 2017, 188, 330-341.

- Bajda, M.; Hardygóra, M.; Marasová, D. Energy efficiency of conveyor belts in raw materials industry. Energies, 2022, 15(9), 3080.

- Szczeszek, P.; Jastrząb, A.; Karkoszka, T.; Prusko, A. Energy and ecological optimization of the belt conveyors’ operation. Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering, 2023, 121(1).

- Mathaba, T., & Xia, X. Optimal and energy efficient operation of conveyor belt systems with downhill conveyors. Energy Efficiency, 2017, 10(2), 405-417.

- Kawalec, W.; Król, R.; Suchorab, N. Regenerative belt conveyor versus haul truck-based transport: Polish open-pit mines facing sustainable development challenges. Sustainability, 2020, 12(21), 9215.

- Naworyta, W.; & Sikora, M. Czy możliwa jest budowa elektrowni szczytowo-pompowej na terenach po wydobyciu węgla brunatnego? Analiza zagrożeń, ograniczeń i korzyści. Analiza zagrożeń, ograniczeń i korzyści. Nowa Energia, 2023, 3. (in Polish).

- Jurdziak, L.; Kawalec, W.; Kasztelewicz, Z.; Parczyk, P. Using RES Surpluses to Remove Overburden from Lignite Mines Can Improve the Nation’s Energy Security. Energies, 2024, 18(1), 104.

- Raj, P. P.; Pochont, N. R.; Teja, K. R.; Kumar, G. D. Solar PV Application in Industrial Conveyor System. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 573, No. 1, p. 012046). IOP Publishing, (2020, October).

- Bajda, M.; Jurdziak, L.; Konieczka, Z. Comparison of electricity consumption by belt conveyors in a brown coal mine: Pt 1, Study of statistical significance of differences and correlations. Górnictwo Odkrywkowe, 2018, 26, 263-274 (in Polish).

- Suchorab, N. Specific energy consumption–the comparison of belt conveyors. Mining Science, 2019, 26, 263-274.

- Kawalec, W.; Suchorab, N.; Konieczna-Fuławka, M.; Król, R. Specific energy consumption of a belt conveyor system in a continuous surface mine. Energies, 2020, 13(19), 5214.

- Bajda, M.; Jurdziak, L.; Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J. Energy-Saving of Conveyor Belts in the Strategy and Reporting of Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives of Producers. In Global Congress on Manufacturing and Management (2021, June), (pp. 402-414). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Köken, E.; Lawal, A. I.; Onifade, M.; Özarslan, A. A comparative study on power calculation methods for conveyor belts in mining industry. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment 2022, 36(1), 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchorab-Matuszewska, N. Data-Driven Research on Belt Conveyors Energy Efficiency Classification. Archives of Mining Sciences, 2024, 375-389.

- Blazej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kawalec, W. Energy saving solutions for belt conveyors in lignite surface mines. Institute of Mining Engineering, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Poland 2015.

- Roumpos, C.; Partsinevelos, P.; Agioutantis, Z.; Makantasis, K.; Vlachou, A. The optimal location of the distribution point of the belt conveyor system in continuous surface mining operations. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory, 2014, 47, 19-27.

- Youssef, G. Development of Conveyor Belts Design for Reducing Energy Consumption in Mining Applications. Ain Shams University, 2016.

- Zhou, S. J.; Zeng, F.; Du, J.; Wu, Q.; Ren, F. Experimental research on the energy consumption laws and its influencing factors of belt conveyor systems. In 2016 13th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), (2016, December), (pp. 395-402).

- Krol, R.; Kawalec, W.; Gladysiewicz, L. An effective belt conveyor for underground ore transportation systems. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, (2017, December), (Vol. 95, No. 4, p. 042047). IOP Publishing.

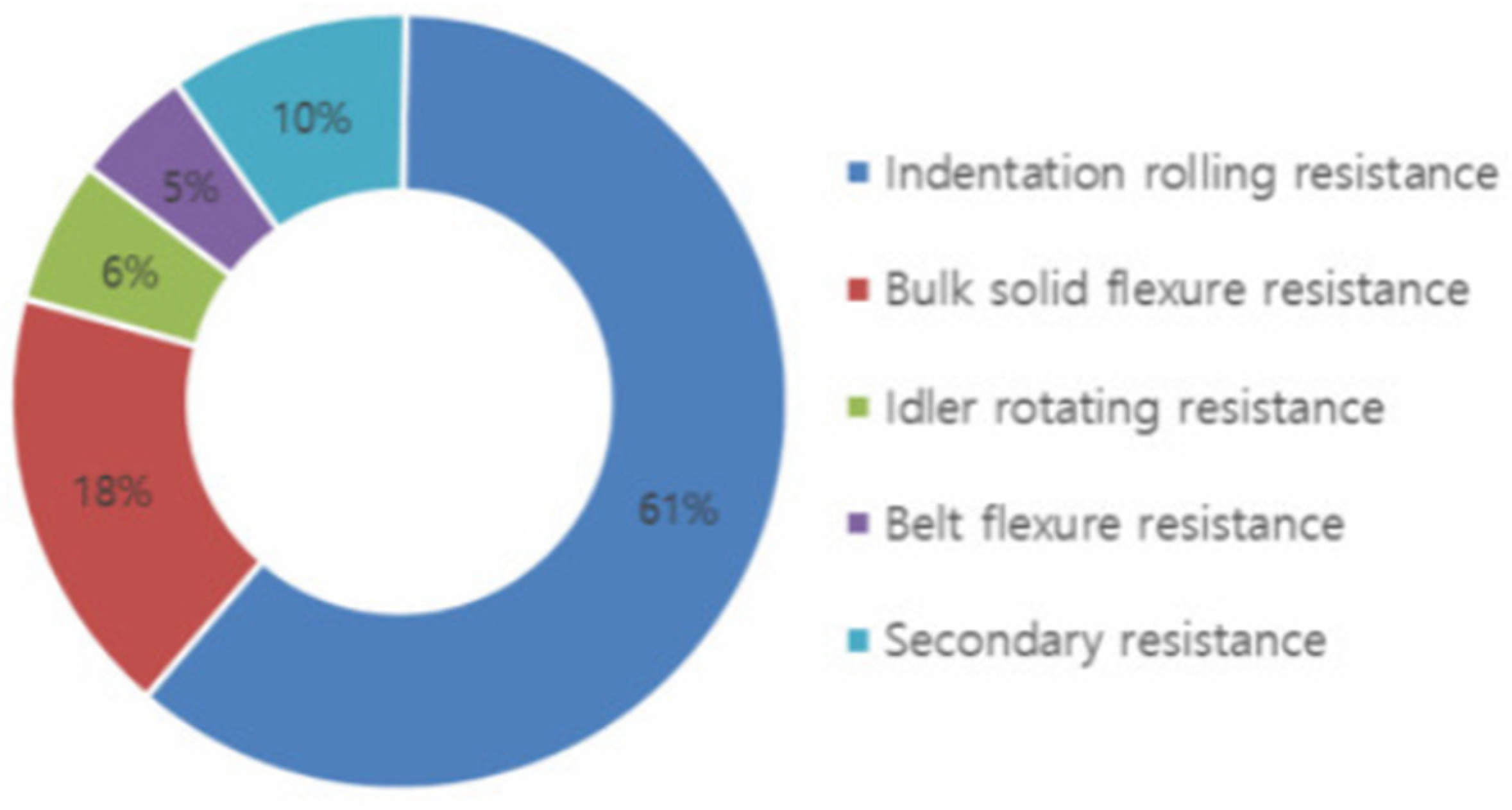

- Munzenberger, P.; Wheeler, C. Laboratory measurement of the indentation rolling resistance of conveyor belts. Measurement, 2016, 94, 909-918.

- Woźniak, D. Laboratory tests of indentation rolling resistance of conveyor belts. Measurement 2020, 150, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos e Santos, L.; Ribeiro Filho, P. R. C. F.; Macêdo, E. N. Indentation rolling resistance in pipe conveyor belts: A review. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, 2021, 43(4), 230.

- Zhou, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yao, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Cao, X. Temperature characteristics of indentation rolling resistance of belt conveyor. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 2023, 37(8), 4125–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Lin, F. Simulation and Experimental Study on Indentation Rolling Resistance of a Belt Conveyor. Machines 2024, 12(11), 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinowski, P.; Kasza, P.; Zarzycki, J. Influence of design parameters of idler bearing units on the energy consumption of a belt conveyor. Sustainability 2021, 13(1), 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinowski, P.; Kasza, P.; Zarzycki, J. Methods of Testing of Roller Rotational Resistance in Aspect of Energy Consumption of a Belt Conveyor. Energies, 2022, 16(1), 26.

- Malakhov, V. A.; Dyachenko, V. Rolling resistance coefficient of belt conveyor rollers as function of operating conditions in mines. Eurasian Mining 2022, 1, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opasiak, T.; Margielewicz, J.; Gąska, D.; Haniszewski, T. Rollers for belt conveyors in terms of rotation resistance and energy efficiency. Transport Problems 2022, 17(2), 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M.; Hardygóra, M. Analysis of the Influence of the Type of Belt on the Energy Consumption of Transport Processes in a Belt Conveyor. Energies, 2021, 14(19), 6180.

- Jena, M. C.; Mishra, S. K.; Moharana, H. S. Experimental investigation on maximizing conveying efficiency of belt conveyors used in series application and estimation of power consumption through statistical analysis. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 2023, 42(3), e14031.

- Wen, L.; Liang, B.; Zhang, L.; Hao, B.; Yang, Z. Research on coal volume detection and energy-saving optimization intelligent control method of belt conveyor based on laser and binocular visual fusion. 2023, IEEE Access.

- Dinolov, O.; Yordanov, R. Tailored Review on the Research in the Electric-Energy Efficiency of Transport Processes (Part 1): Bulk Materials and Fluids. In 2024 9th International Conference on Energy Efficiency and Agricultural Engineering (EE&AE), (2024, June), 1-9.

- Lodewijks, G.; Schott, D. L.; Pang, Y. Energy saving at belt conveyors by speed control. In Proceedings of the Beltcon 16 conference, 2011, 1-10.

- Ji, J.; Miao, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Speed regulation strategy and algorithm for the variable-belt-speed energy-saving control of a belt conveyor based on the material flow rate. Plos one, 2021, 16(2), e0247279.

- Ni, Y.; Chen, L. Research of energy saving control System of Mine belt conveyors. In 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data & Smart City (ICITBS), (2021, March), (pp. 579-581). IEEE Access.

- Jena, M. C.; Mishra, S. K.; Moharana, H. S. Experimental investigation on maximizing conveying efficiency of belt conveyors used in series application and estimation of power consumption through statistical analysis. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 2023, 42(3), e14031.

- Ilic, D.; Wheeler, C. Measurement and simulation of the bulk solid load on a conveyor belt during transportation. Powder Technology, 2017, 307, 190-202.

- Wheeler, C.; Munzenberger, P.; Ausling, D.; Beh, B. Energy efficient belt conveyor design. Tunra Bulk Solids Research Associates, 2018, 27.

- Doroszuk, B.; Krol, R. Analysis of conveyor belt wear caused by material acceleration in transfer stations. Mining Science, 2019, 26, 189-201.

- Doroszuk, B.; Król, R.; Wajs, J. Simple design solution for harsh operating conditions: redesign of conveyor transfer station with reverse engineering and DEM simulations. Energies, 2021, 14(13), 4008.

- Ambriško, Ľ.; Marasová Jr, D.; Klapko, P. Energy Balance of the Dynamic Impact Stressing of Conveyor Belts. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(7), 4104.

| Conveyor construction data | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Length in m | 1012.6 | 1018.5 |

| Belt speed in m/s | 5.24 | 5.24 |

| Theoretical mass capacity in Mg/h | 6400 | 6400 |

| Theoretical volume capacity Mg/h | 8000 | 8000 |

| Number of pulleys in a set | 3 | 3 |

| Idler length in mm | 670 | 670 |

| Idler diameter in mm | 191 | 191 |

| Idler set spacing in m | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| Trough angle | 45 | 45 |

| Belt type | St3150 | St3150 |

| Belt width in mm | 1800 | 1800 |

| Coal bulk density in Mg/m3 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Collected operating data | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Number of monthly measurements | 36* | 48 |

| Total mass transferred in Mg | 42 096 610 | 46 540 032 |

| Total operating time in hours | 17 672.9 | 20 151.84 |

| Total energy consumption in MWh | 12 058.42 | 13 994.02 |

| Average monthly operating time in hours | 490.91 | 419.83 |

| Standard deviation | 60.98 | 91.28 |

| Coefficient of variation in % | 12.42% | 21.74% |

| Minimum | 352.1 | 198.6 |

| Maximum | 629.4 | 584.7 |

| Range of change | 277.3 | 386.1 |

| The average amount of mass transferred in Mg | 1 169 350 | 969 584 |

| Standard deviation | 198 752 | 243 846 |

| Coefficient of variation | 17.00% | 25.15% |

| Minimum | 760 503 | 424 723 |

| Maximum | 1 695 160 | 1 574 020 |

| Range of change | 934 657 | 1 149 297 |

| Average energy consumption in MWh | 334.956 | 291.542 |

| Standard deviation | 43.88 | 62.97 |

| Coefficient of variation | 13.10% | 21.60% |

| Minimum | 212.0 | 140.7 |

| Maximum | 441.6 | 406.5 |

| Range of change | 229.6 | 265.8 |

| Calculated capacities and ZE indicators | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Average efficiency for total values in Mg/h | 2 381.99 | 2 309.47 |

| The degree to which the theoretical capacity was utilized in % | 37.22% | 36.09% |

| Unit indicator ZE for total energy consumption in Wh/Mg/km | 286.45 | 300.69 |

| Average monthly efficiency Q in Mg/h | 2 370.56 | 2 296.89 |

| Standard deviation | 146.622 | 142.201 |

| Coefficient of variation | 6.19% | 6.19% |

| Minimum | 2 119.17 | 2 045.89 |

| Maximum | 2 693.29 | 2 692.01 |

| Range of change | 574.12 | 646.12 |

| ZE indicator in Wh/Mg/km | 288.57 | 303.58 |

| Standard deviation | 18.18 | 19.12 |

| Coefficient of variation | 6.30% | 6.30% |

| Minimum | 256.87 | 254.7 |

| Maximum | 336.35 | 344.57 |

| Range of change | 79.48 | 89.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).