1. Introduction

The global shift toward low-carbon and sustainable energy systems has become a critical priority as governments, industries, and communities respond to the dual challenges of climate change and fossil fuel dependency. Thermal Energy Storage (TES) systems have emerged as key enablers of renewable energy integration, providing the flexibility to match intermittent energy generation with variable demand. TES can improve energy efficiency, stabilize grid operations, and enable sector coupling between power, heating, and industrial applications [

1]. Among various TES approaches, Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES) is a novel and increasingly recognized strategy that utilizes abandoned, water-filled mines as large-scale underground thermal reservoirs [

2].

MTES systems are particularly promising in post-mining regions where extensive subsurface infrastructure remains unused. These flooded mines provide naturally insulated environments capable of storing significant volumes of thermal energy with minimal surface disturbance. In contrast to conventional above-ground TES systems that often require substantial land, construction, and material inputs, MTES takes advantage of existing geological voids and hydraulic connectivity within mine networks. This allows for cost-effective, low-carbon heating solutions at the community or district scale [

3]. Importantly, MTES enables

seasonal heat storage—absorbing and storing excess heat during summer or off-peak periods and extracting it in winter when heating demand peaks.

In cold-climate regions such as Canada, seasonal imbalance between heating needs and renewable energy supply presents a significant challenge. Wind and solar power generation are variable and often out of phase with thermal demand. MTES offers a practical pathway to mitigate this mismatch by capturing surplus renewable or waste heat and using it to heat residential, commercial, or industrial buildings during colder months [

4]. Heat extraction is typically achieved via open- or closed-loop well systems connected to heat exchangers and high-efficiency heat pumps.

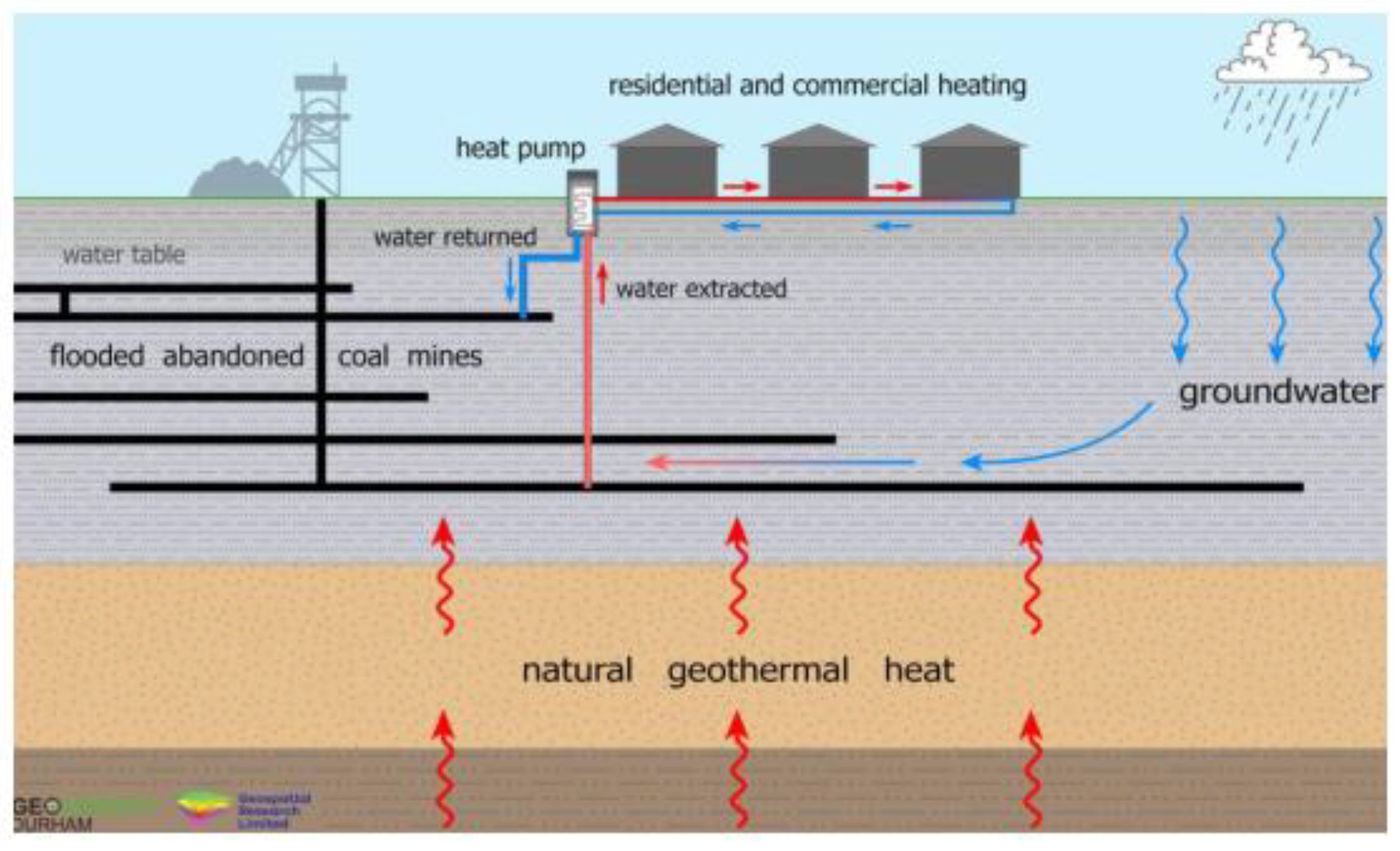

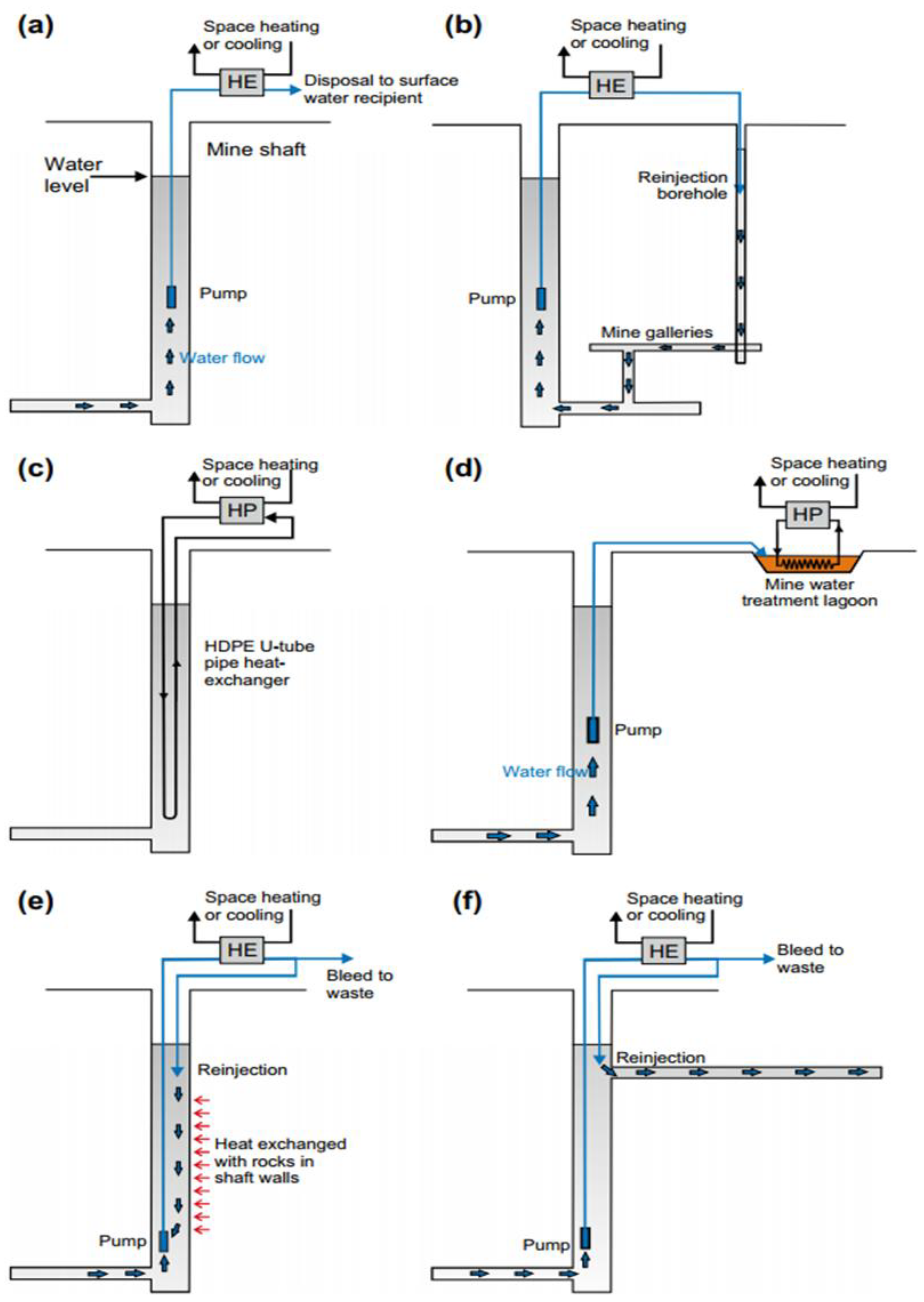

Figure 1 illustrates the basic configuration of a mine water geothermal system, where heated or cooled mine water is circulated between underground reservoirs and surface heat exchange systems.

Several international case studies have successfully demonstrated the technical feasibility and socioeconomic benefits of MTES. The

Springhill Project in Nova Scotia has supplied geothermal heating to municipal and commercial buildings since the 1980s using water from flooded coal mines [

6,

7]. In

the Netherlands, the Heerlen Minewater Project transformed abandoned mines into a district heating and cooling system, pioneering the use of standing column wells and bidirectional thermal flow control to serve multiple buildings with low-carbon heat [

4]. Similarly, in

Bochum, Germany, the HT-MTES project integrates solar thermal collectors and high-temperature heat pumps with repurposed mine shafts to deliver seasonal thermal energy to a district heating network [

8]. In the United Kingdom, pilot systems at Caphouse and Markham Collieries have explored both open- and closed-loop configurations for mine water heat recovery [

9]. These examples illustrate not only the engineering viability of MTES but also its adaptability to diverse climatic, geological, and infrastructural conditions. They also underscore the potential for MTES to support just transitions in coal-dependent regions by revitalizing legacy infrastructure and creating green energy hubs.

Nova Scotia, Canada, presents a unique opportunity for MTES implementation due to its extensive inventory of abandoned coal mines and ambitious climate targets. The province aims to achieve

80% renewable electricity generation by 2030 and phase out coal-fired power [

10]. However, the seasonal and intermittent nature of wind and solar energy resources poses reliability challenges. Simultaneously, heating in Nova Scotia remains heavily reliant on oil, with high per-household energy costs and carbon intensity. MTES offers a compelling alternative by enabling local, secure, and low-carbon heat supply using infrastructure already embedded in the landscape.

This study investigates the feasibility of MTES in Nova Scotia, with a focus on the Sydney Coalfield, a historically significant mining region on Cape Breton Island. The Sydney Coalfield includes over 50 abandoned underground coal mines, collectively estimated to contain more than 190 million cubic metres of mine water [

11,

12,

13]. This research specifically examines the 1B Hydraulic System, a well-documented subsystem within the coalfield that comprises ten interconnected mines holding approximately 76.7 million cubic metres of water [

14]. This volume represents a significant opportunity for high-capacity, seasonal thermal energy storage at the community or district scale.

The study integrates multiple lines of analysis, including geological and hydrogeological assessment, residential and sectoral heating demand estimation, mine water thermal capacity calculation, system design, energy requirements, and economic feasibility. It also compares the Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) for MTES with conventional oil-based heating and individual heat pump systems. Beyond technical feasibility, this work explores the potential for MTES to support regional renewable integration by coupling with wind and solar power, storing excess energy during off-peak periods and releasing it during peak demand. Such integration enhances grid flexibility and aligns with Nova Scotia’s decarbonization strategy.

By situating MTES within both local and international contexts, this study contributes to a growing body of knowledge on underground thermal energy storage and its role in sustainable energy transitions. It builds upon global best practices while addressing the specific geological, climatic, and economic conditions of Nova Scotia. In doing so, it aims to inform future policy, planning, and pilot project development related to thermal energy storage and mine site reuse.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Overview of Thermal Energy Storage Technologies

Thermal Energy Storage (TES) plays an essential role in modern energy systems, enabling the temporary storage of excess thermal energy for later use. By decoupling energy supply from demand, TES systems support grid stability, enhance the flexibility of renewable energy integration, and improve energy system efficiency. Various TES technologies have been developed, including Borehole Thermal Energy Storage (BTES), Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES), and Cavern Thermal Energy Storage (CTES), each with distinct geotechnical and operational characteristics [

1].

Among these, Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES) has gained attention as a regionally scalable and cost-effective solution in areas with a legacy of underground mining. MTES systems utilize flooded or abandoned mine shafts as subsurface reservoirs to store and retrieve heat for district or building-level heating applications. These systems leverage existing infrastructure, reducing land-use conflict and capital costs, while offering long-term storage potential and high spatial capacity [

2]. However, their feasibility is influenced by subsurface conditions, mine layout, hydrogeology, and proximity to heating demand.

2.2. Infrastructure and Operating Principles of MTES

MTES systems generally consist of subsurface mine reservoirs and above-ground infrastructure that includes extraction and reinjection wells, pumps, heat exchangers, insulated distribution piping, and control systems. Heat injection occurs during periods of surplus thermal energy availability (e.g., summer or off-peak hours), with heat stored in mine water and surrounding rock. During colder months, the stored heat is extracted, upgraded by a heat pump, and supplied to end users. The system functions cyclically, absorbing and discharging thermal energy over time.

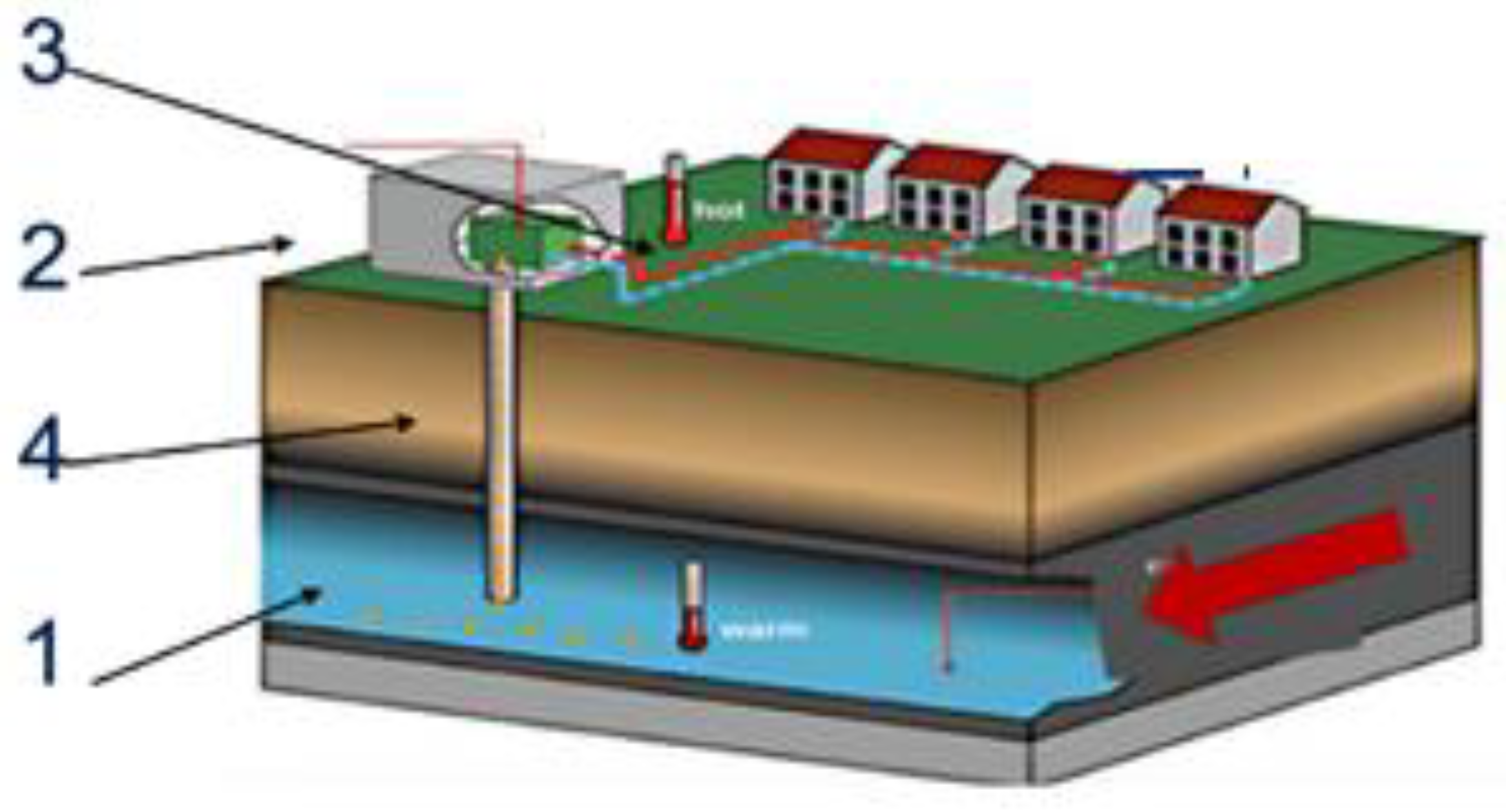

Figure 2 illustrates the working principle of a mine water MTES system, which operates in four interconnected steps. First, warm mine water is pumped from the flooded coal seam to the surface, carrying geothermal heat and, during warmer months, potentially enhanced by solar thermal or industrial waste heat. Second, this heat is transferred via a heat exchanger to a district heating or cooling network. Third, a heat pump raises the temperature to a usable level for buildings or industrial use. Finally, the cooled mine water is reinjected into the mine, where it gradually regains heat from the surrounding rock. This cyclical process enables MTES to function as a seasonal thermal battery, ideal for cold-climate applications.

System performance depends heavily on the efficiency of pumps, heat exchangers, and heat pumps. Heat exchangers are typically either [

16]:

Heat pumps raise the temperature of extracted mine water (typically 12–20 °C) to usable heating levels. System efficiency is usually evaluated using the Coefficient of Performance (COP), defined as the ratio of useful heat output to electrical input. COP values above 3.5 are typically required for economic viability, especially when integrated with district energy networks [

2,

17].

Multiple system configurations are possible depending on local conditions. These include:

Open-loop systems, which extract and discharge mine water (either to the surface or back into the mine);

Closed-loop systems, which use submerged heat exchangers and do not circulate mine water externally;

And standing column systems, which combine extraction and reinjection at different depths within the same shaft.

Figure 3 presents an overview of these main system types and their operational arrangements.

2.3. International Case Studies of MTES Systems

Several international pilot and commercial MTES systems provide valuable insights into the scalability, performance, and technical challenges of implementing MTES in real-world settings.

Springhill, Canada: Located in Nova Scotia, the Springhill Mine Water Geothermal Project is one of the earliest operational MTES systems. Developed in the 1980s, it uses mine water extracted from depths up to 1,350 m, with temperatures reaching up to 26 °C, to provide heating and cooling for industrial and public facilities. The system operates using heat exchangers and a network of 11 heat pumps and has achieved up to 60% heating cost reduction for some users, while significantly lowering GHG emissions [

6,

7].

Heerlen, Netherlands: The Heerlen Minewater Project, launched in 2008, has evolved into an advanced fifth-generation district heating and cooling (5GDHC) system. It uses multiple extraction and reinjection wells to manage thermal flows between interconnected buildings and clusters. The system integrates renewable energy, smart thermal grid controls, and real-time balancing mechanisms to deliver more than 5 GWh of heating and cooling annually, achieving major efficiency gains and CO₂ reductions [

4,

18,

19].

Bochum, Germany: The Bochum HT-MTES system in the Markgraf II shaft is a high-temperature seasonal thermal storage project integrated with solar thermal collectors and a district heating network. Heat is injected into the mine water during summer and extracted in winter using a 500 kW high-temperature heat pump. The system delivers over 13 GWh of heating and cooling annually, and its bidirectional flow, stratified storage, and DTS monitoring represent best practices in advanced MTES design [

20,

21,

22].

These case studies confirm the technical viability of MTES, the potential for integration with local renewable sources, and the need for careful system configuration to prevent thermal short-circuiting, manage water quality, and maintain long-term performance. The experiences from Springhill, Heerlen, and Bochum provide a strong foundation for evaluating MTES potential in post-mining communities like Glace Bay, Nova Scotia.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodology used to evaluate the feasibility and performance of a Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES) system. The approach is structured to allow replication and adaptation for different geographical and geological contexts, with all relevant assumptions, formulas, and references based on standard geothermal engineering principles and existing literature.

2.1. Heating and Cooling Demand Estimation

Heating and cooling demands were calculated using Energy Use Intensity (EUI) values specific to Nova Scotia and adjusted for residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. The demand estimates focus on space heating and cooling, which are the primary loads addressable by MTES systems. EUI represents the total annual energy consumption per unit floor area (in GJ/m²/year) and includes all end uses such as heating, cooling, lighting, and appliances; therefore, sector-specific heating and cooling fractions are applied to isolate the portions relevant to thermal demand. Equations (1) and (2) were used to estimate annual thermal demand based on gross floor area and sector-specific heating and cooling fractions [

23,

24].

Where

is the annual space heating demand,

is the annual space cooling demand

is the fraction of total EUI allocated to space heating, and

is the fraction of total EUI allocated to space cooling

2.2. MTES Capacity Assessment

The thermal storage capacity was determined by calculating the heat stored in both mine water and surrounding rock using Equations (4) and (5) [

25,

26]. Key parameters included: Mine water volume (

), Rock-volume to water-volume ratio (

R), Specific heat capacities of water and rock (

), densities of water and rock (

), and usable temperature change (

∆T).

2.3. Heat Retrieval System Design

Two primary configurations can be employed for heat extraction: open-loop and closed-loop systems [

9,

17]. Design factors such as flow rate (

), fluid density (

), specific heat capacity (

), and temperature difference (across the heat exchanger) (

) were used to calculate heat extraction potential via Equation (5), with the final heat delivered estimated using Equation (6) [

2]. Where

is

, and

is the Coefficient of Performance of the heat pump.

2.4. Electrical Energy Requirements

Annual energy demands were calculated for each subsystem:

Pumping system: Based on flow rate (

), pumping head overcome (frictional losses + elevation difference) (

), and pump efficiency (

), density of water (

), and acceleration due to gravity (9.81m/s2) using [

17]:

Heat exchangers: Estimated using pressure drop and flow characteristics via Equation (8) [

27,

28]:

Where

is the head loss across the heat exchanger system.

Heat pumps: Evaluated using thermal energy output delivered by the heat pump (

) and

via [

25]:

The total annual electrical energy requirement was computed as the sum of all components.

2.5. Cost Analysis and Economic Feasibility

Cost components were divided into:

CAPEX: Including well drilling, heat pump and exchanger installation, distribution infrastructure, and SCADA systems [

17,

29];

OPEX: Including labor, electricity, maintenance, and compliance [

29].

The Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) was calculated using Equation (10), with the Capital Recovery Factor (CRF) derived from Equation (11) [

30]. Where

is the total heat energy delivered annually,

is the discount rate, and

is the system lifespan (years). This metric facilitates economic comparison with conventional heating systems.

3. Results

This section presents the outcomes of applying the MTES design framework to the selected site in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. The calculations are based on the equations introduced in

Section 2, with key technical assumptions drawn from site-specific data and relevant literature.

3.1. Heating and Cooling Demand Estimation

The annual space heating and cooling demand in Glace Bay was estimated using floor area data and Energy Use Intensity (EUI) values for the residential, commercial, and industrial sectors, applying the methodology described in Equations (1) and (2). These equations use gross heated area and sector-specific heating and cooling fractions to isolate the portion of total energy consumption attributable to space conditioning.

For the

residential sector, the total heated area was derived using the 2021 Census housing stock data for Glace Bay [

31] and average unit sizes by dwelling type [

32], resulting in approximately 1.4 million m². An EUI of 0.58 GJ/m²/year was applied based on Nova Scotia-specific benchmarks [

33], and space heating and cooling fractions of 65.5% and 0.6% were used, respectively.

The

commercial and institutional sector was assessed using a conservative estimate of 10 m² per capita, applied to a population of 17,000 [

31], yielding a total area of 170,000 m². An EUI of 1.12 GJ/m²/year was used, with 42.4% for heating and 8.9% for cooling [

34].

For the

industrial sector, it was assumed that 12 facilities are active in the region [

35], each with an average heated area of 4,000 m², totaling 48,000 m². The EUI used was 0.8 GJ/m²/year, with 60% allocated to heating and 5% to cooling [

36].

The combined heating and cooling demand for all sectors in Glace Bay is approximately 185 GWh per year. The breakdown is provided in

Table 1.

These demands reflect year-round space conditioning loads, with peak heating required in winter and cooling concentrated in the summer. This seasonality plays a key role in determining the required storage capacity and thermal cycling strategy of the MTES system.

3.2. Thermal Energy Storage Capacity

This study evaluated the thermal energy storage (TES) capacity of two major flooded mines in Glace Bay: Colliery No. 2 and Colliery No. 9, both situated within the 1B Hydraulic System. The total theoretical thermal storage capacity was calculated based on the methodology described in Equations (3) and (4), which estimate the heat retained in both mine water and the surrounding rock mass.

According to historical mine data, Colliery No. 2 contains approximately 17.26 million m³ of flooded mine water, while Colliery No. 9 contains approximately 4.98 million m³ [

14]. A rock-to-water volume ratio (

R) of 3:1 was assumed based on typical mine structures and regional geological conditions. This ratio represents the volume of surrounding rock contributing to heat storage per unit volume of mine water and is critical in determining the role of the rock matrix in long-term thermal retention. Higher R values imply a larger thermal reservoir but may reduce heat transfer rates due to increased thermal resistance. The seasonal temperature differential (

∆T) was assumed to be 12 °C, reflecting the operational temperature swing between heat injection and extraction phases during seasonal cycling. This

∆T represents the usable range for thermal storage while maintaining system efficiency and material integrity.

The thermal properties used for calculations included:

1000 kg/m³,

2500 kg/m³,

4.18 kJ/kg·°C, and

0.84 kJ/kg·°C, all consistent with literature values for comparable MTES systems [

25,

26]. These values are considered reasonable for scoping-level analysis; however, site-specific geological surveys are recommended to refine capacity estimates [

26].

Based on this methodology, the total storage potential for Colliery No. 2 was estimated at 240.46 GWh in water and 362.41 GWh in rock, totaling 602.87 GWh. For Colliery No. 9, the calculated capacity was 69.4 GWh in water and 104.6 GWh in rock, totaling 174.0 GWh.

Assuming an overall system efficiency of 80% to account for losses from pumping, heat exchange, and thermal dissipation, the usable thermal energy output is estimated at 482.29 GWh for Colliery No. 2 and 139.20 GWh for Colliery No. 9. The combined usable capacity of 621.5 GWh significantly exceeds Glace Bay’s estimated annual thermal energy demand of approximately 185 GWh (see

Section 3.1), supporting the feasibility of MTES as a long-duration seasonal storage system with additional capacity for future demand or district expansion.

3.3. Usable Thermal Energy Output

The proposed MTES system for Glace Bay employs a centralized open-loop configuration, drawing mine water from three extraction wells at Colliery No. 2, circulating it through plate heat exchangers, and reinjecting it through two wells at Colliery No. 9. This design leverages the natural elevation difference (~43 m) and hydraulic separation between the collieries to optimize heat transfer and reduce the risk of thermal short-circuiting [

37]. The system layout is based on best practices from established MTES projects in Springhill, Canada, and Heerlen, Netherlands [

6,

9,

17].

A total flow rate of 150 L/s (0.15 m³/s), supported by three extraction wells at 50 L/s each, was selected based on hydrogeological assessments and performance benchmarks from comparable minewater systems in Heerlen and the UK [

4,

9,

17]. This range aligns with sustainable extraction rates (100–200 L/s) identified for Glace Bay based on historical mine dewatering records, including the Neville Street well [

11]. To ensure efficient transport and minimize frictional losses, a 350–400 mm (14–16 inch) HDPE or steel main header is proposed. For individual branches from each well, 200–250 mm (8–10 inch) piping is recommended to accommodate the 50 L/s flow per line. Chemically resistant HDPE or steel is selected for distribution piping, while stainless steel is preferred for suction and internal pump station connections. End-suction centrifugal pumps housed in aboveground pump stations are proposed to provide reliable, high-volume water handling [

38].

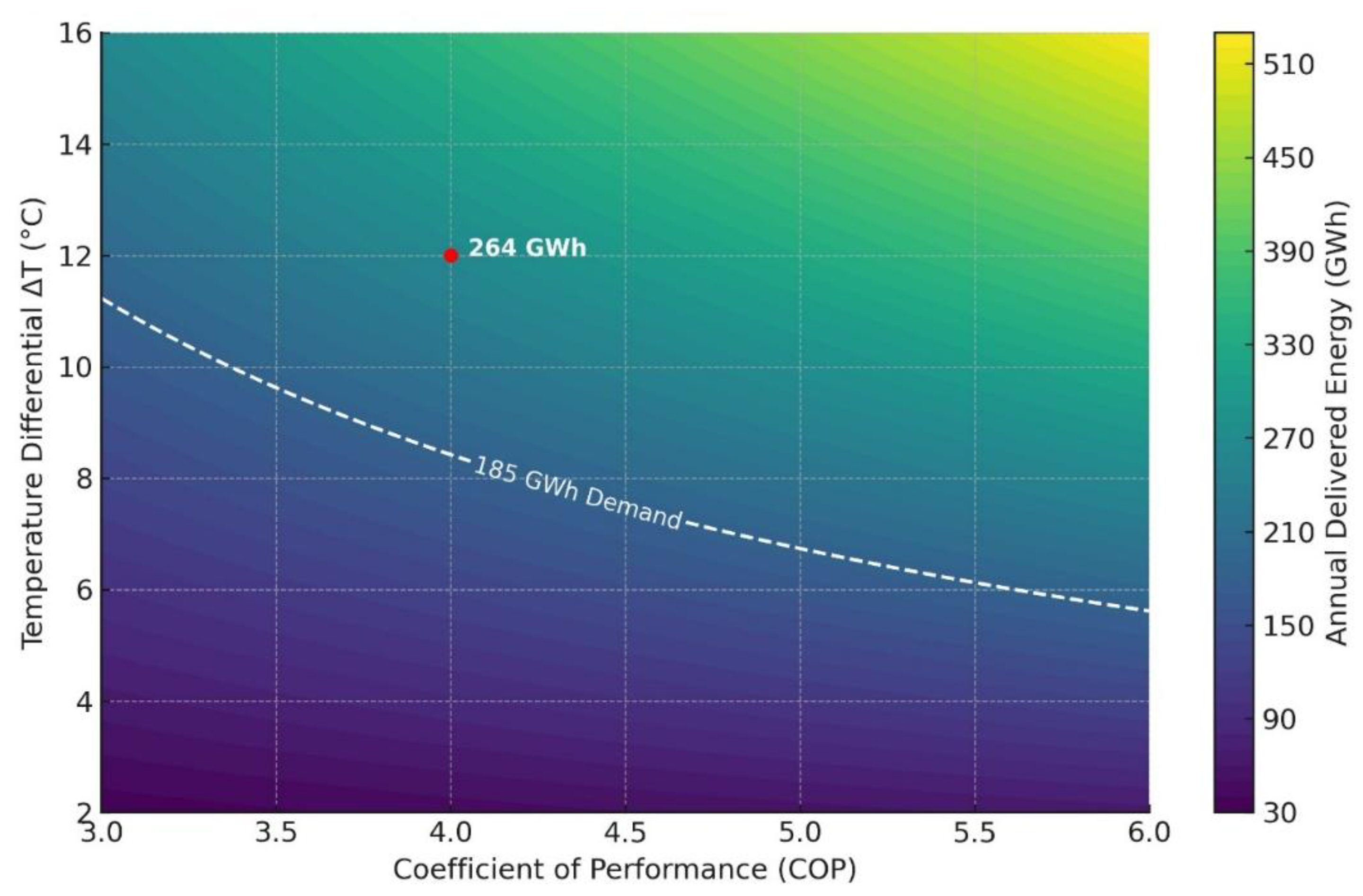

The retrievable heat from the system was calculated using Equation (5), assuming a flow rate () of 0.15 m³/s, a water density () of 1000 kg/m³, a specific heat capacity () of 4.18 kJ/kg·K, and a temperature differential () of 12 °C.

This results in a thermal power output of 7.52 MW. Over a year (8,760 hours), the annual thermal energy extracted is approximately 66 GWh. Applying a heat pump Coefficient of Performance () of 4.0 in Equation (6), the total annual delivered thermal energy is 264 GWh/year. This thermal output exceeds Glace Bay’s estimated annual heating and cooling demand (185 GWh/year) by approximately 43%, providing flexibility for system expansion, peak demand management, and seasonal cycling.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the system demonstrates resilience to variations in operating conditions. Even under suboptimal performance—such as a reduced

ΔT or

COP—the annual thermal output remains sufficient to meet Glace Bay’s current demand. In warmer months, when heating demand is lower, the system can operate in a charging mode by injecting surplus heat—sourced from cooling systems or renewables like solar thermal—into the mine reservoir. This seasonal flexibility enhances overall efficiency and reliability, aligning the system with long-duration energy storage goals.

3.4. Electrical Energy Requirements

The annual electrical energy requirement for operating the proposed MTES system in Glace Bay was estimated by evaluating the major subsystems: pumps, heat exchangers, heat pumps, and auxiliary equipment. These estimates are based on the design specifications, performance benchmarks from similar geothermal systems, and Equations (7), (8) and (9) described earlier.

For pumping, a total flow rate of 150 L/s (0.15 m³/s), where three extraction wells each operate at 50 L/s, and a total dynamic head of 300 m were assumed. This value reflects the depth of Colliery No. 2 (261–263 m) and includes estimated frictional losses ranging from 10 to 100 m, consistent with hydrogeological assessments and historical dewatering records [

39]. Only the extraction wells at Colliery No. 2 were considered in the pumping energy calculations, as reinjection at Colliery No. 9 occurs at a higher elevation and relies primarily on gravitational flow. Assuming a pump efficiency of 80%, the estimated annual pumping energy is approximately 4.83 GWh/year, in line with design standards for geothermal systems [

28], as calculated using Equation (7).

According to Equation (8), the heat exchanger power requirement was estimated based on a pressure drop of 4.5 m, as recommended by ASHRAE Standard 90.1-2013 [

40], and an assumed efficiency of 80%. This results in a minor contribution of approximately 0.073 GWh/year to the total system demand.

For heat pumps, the system is designed to deliver 185 GWh/year of thermal energy to Glace Bay’s residential, commercial, and industrial users. Using a conservative Coefficient of Performance (

COP) of 4—typical for modern water-source heat pumps under standard conditions [

38]—and based on Equation (9), the annual electrical input required is

46.25 GWh/year.

Auxiliary systems, including SCADA, sensors, valves, and communication infrastructure, were estimated to account for 1.5% of the total electricity consumption of the other subsystems. This results in an additional 0.77 GWh/year, based on established benchmarks in geothermal plant design.

In total, the estimated annual electrical energy requirement for operating the MTES system in Glace Bay is approximately 52 GWh/year, including all major subsystems. This figure serves as a critical input for cost evaluation, system optimization, and planning for renewable electricity integration, as discussed in subsequent sections.

3.5. Economic Feasibility and Cost Analysis

A comprehensive economic feasibility analysis is essential for assessing the viability of implementing the MTES system in Glace Bay. This section evaluates both Capital Expenditures (CAPEX) and Operational Expenditures (OPEX), providing a detailed breakdown of system components and ongoing operational costs. To contextualize MTES within the local energy landscape, cost comparisons are also made with conventional oil-based heating and individual residential heat pump systems. All cost estimates, including CAPEX, OPEX, and Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH), are presented exclusive of taxes (e.g., HST) to maintain consistency across alternatives. This approach reflects standard industry practice in early-stage feasibility studies, where taxes often depend on ownership structure and funding mechanisms.

3.5.1. Capital Expenditure (CAPEX)

The estimated capital costs for the proposed MTES system include major infrastructure components such as geothermal wells, heat pumps, heat exchangers, piping networks, and SCADA systems. Cost values were drawn from established benchmarks and converted from USD to CAD using a June 2025 exchange rate of 1 USD = 1.36 CAD.

The five-well configuration—comprising three extraction wells at Colliery No. 2 and two reinjection wells at Colliery No. 9—is based on international practice (e.g., the Heerlen Minewater Project [

4,

9]) and local geological conditions. Drilling costs range from

$49 to

$131 per meter, depending on well depth and casing requirements [

41,

42], with additional costs for 72-hour pump testing [

43], estimated at approximately

$8,300 USD per well [

44].

The heat pump system is designed to deliver 185 GWh/year of thermal energy with a Coefficient of Performance (

COP) of 4, corresponding to a required capacity of 23.6 MW. Installation costs are estimated at

$1,200–

$2,200 per kW based on current market [

45,

46]. Heat exchanger costs are estimated at

$100–

$300 per kW, reflecting similar large-scale systems [

47].

Piping and distribution infrastructure costs are based on a 107 km dual-pipe network, with installed unit costs ranging from

$800 to

$1,200 per meter [

48,

49], inclusive of trenching, insulation, and site restoration. The SCADA and control system is estimated to cost between

$150,000 and

$500,000, depending on system configuration and integration complexity [

50,

51].

Table 2 summarizes the total estimated capital cost:.

3.5.2. Operational and Maintenance Costs (OPEX)

Annual operating costs include labor, electricity, and maintenance. Labor costs were based on a staff of 5–6 with total wages of

$570,000 to

$660,000 CAD/year [

52]. Electricity costs are derived from Nova Scotia Power’s 2024 Large Industrial Tariff [

53], with 52 GWh/year consumption at

$0.10184/kWh and demand charges for 2.6 MW (2,600 kVA) of peak load, totaling approximately

$5.8 million CAD/year.

An industry benchmark of 1% of total capital expenditure is commonly used to estimate annual maintenance costs, ranging from $1.7 to $2.7 million CAD per year.

Table 3 summarizes the estimated annual OPEX.

3.5.3. Levelized Cost of Heat for the Glace Bay MTES System

The Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) was calculated over a 25-year system lifespan using a 5% discount rate. The annual thermal energy output is estimated at 264 GWh (950,400 GJ). Based on Equation (10) and a Capital Recovery Factor (CRF) of 0.07 derived from Equation (11), the LCOH is calculated as follows:

This LCOH range serves as a benchmark for assessing the economic viability of MTES and its alignment with provincial energy policy objectives.

3.5.4. Comparative Cost of Traditional Heating Options in Glace Bay

To evaluate the cost competitiveness of the MTES system, its LCOH is compared to two conventional heating options commonly used in Glace Bay:

Oil Heating Systems: Based on a price of

$1.63 CAD/L and furnace efficiency of 85% [

54,

55], the usable energy is 31.21 MJ/L. The resulting cost per GJ is

$52.23 CAD/GJ.

Residential Heat Pumps: Using Equations (10) and (11), assuming a thermal demand of 72 GJ/year per household, a 20-year system lifespan, and a 5% discount rate, the LCOH was calculated based on a CAPEX of

$12,000–

$20,000 [

56] and an annual OPEX of approximately

$1,440 [

57,

58]. OPEX includes electricity and maintenance: With a seasonal COP of 3.0, each household requires about 6.67 MWh/year (24 GJ) of electricity, costing ~

$1,239/year at the 2025 Nova Scotia rate of

$0.18561/kWh [

57]. Annual maintenance is assumed at

$200 [

58]. The resulting LCOH is:

4. Discussion

This section provides an integrated assessment of the environmental, economic, and technical implications of implementing a Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES) system in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. Drawing from the detailed site-specific findings in

Section 3 and broader renewable energy strategies, the discussion explores the potential benefits, challenges, and future pathways for MTES deployment in post-industrial communities.

4.1. Economic Feasibility and Cost Savings

As established in

Section 3.5, the Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) for Glace Bay’s MTES system ranges from

$21.59 to

$30.74 CAD/GJ, compared to

$52.23 CAD/GJ for oil heating and

$33.33 to

$42.22 CAD/GJ for individual residential heat pumps. This represents a 42%–59% cost reduction compared to oil and 8%–49% savings relative to decentralized heat pumps. International precedents further support this economic advantage. For instance, in Heerlen, the involvement of local energy companies offering financing at relatively low interest rates (6–8%) enabled the delivery of competitively priced thermal energy [

59].

The reuse of existing mine voids significantly reduces capital expenditure by eliminating the need for new underground infrastructure. As a locally controlled energy solution, MTES also enhances energy security and protects communities from global fuel price volatility.

4.2. Environmental Benefits and Emissions Reduction

Transitioning from oil-based heating to MTES offers significant environmental benefits, particularly in reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and supporting Nova Scotia’s net-zero targets. Furnace oil currently supplies approximately 30% of space heating in Nova Scotia, especially in colder regions like Cape Breton [

60]. MTES provides a low-carbon alternative by replacing fossil fuel combustion with mine-sourced geothermal energy, further enhanced by the use of centralized district heating powered by renewable electricity.

Case studies demonstrate the emissions reduction potential of MTES systems. In Springhill, Nova Scotia, the adoption of mine water geothermal technology reduced GHG emissions by approximately 370 tonnes per year, representing a 50% decrease compared to conventional oil-based systems [

7]. Similarly, the Heerlen Minewater 2.0 project in the Netherlands achieved a 65% reduction in emissions across over 500,000 m² of conditioned space [

4].

In the context of Glace Bay, emissions reductions were quantified by comparing current oil-based heating with projected MTES system performance:

Current emissions from oil heating: Based on the residential heating and cooling demand of 150 GWh/year (540,000 GJ) and an emission factor of 71.35 kg CO₂e/GJ [

61,

62], the estimated annual GHG emissions are approximately 38,530 tonnes CO₂e.

Emissions from MTES system: Assuming an annual electricity use of 52 GWh (

Section 3.4) and Nova Scotia’s grid intensity of 660 g CO₂e/kWh [

63], the estimated emissions total 34,320 tonnes CO₂e/year. With a projected 50% renewable electricity share, this value decreases to 17,160 tonnes CO₂e/year—equivalent to a 55% reduction. Under full grid decarbonization, emissions from MTES could approach zero.

These findings reinforce the environmental value of MTES systems and demonstrate their capacity to support regional and national decarbonization efforts through large-scale emissions reductions in the heating sector.

4.3. Infrastructure Reuse and Grid Optimization

MTES enhances grid reliability by converting surplus renewable electricity into thermal energy, which can be stored and used during peak demand. This reduces dependence on carbon-intensive backup power and supports Nova Scotia’s low-carbon transition.

With over 1,000 abandoned mine sites and strong wind energy capacity, Nova Scotia is well positioned to repurpose underground infrastructure as thermal reservoirs—avoiding the costs and environmental impacts of new storage development [

64]. Coordinating mine remediation with MTES deployment can further reduce project costs and accelerate regional revitalization.

The Heerlen Minewater Project in the Netherlands demonstrates this potential, having transformed coal mine shafts into a district-scale energy system that provides heating, cooling, and thermal storage [

4,

59].

4.4. Job Creation and Regional Development

Deploying MTES in Nova Scotia offers a pathway for economic revitalization, especially in post-industrial areas like Glace Bay. By repurposing abandoned mine infrastructure, these projects generate local employment across engineering, hydrogeology, drilling, and district energy construction [

65].

In Springhill, mine water heating reduced municipal energy costs and supported job creation [

6,

65]. Similarly, the Gateshead project in the UK demonstrates how MTES can attract investment and stimulate skilled employment while lowering fossil fuel reliance [

66].

MTES also fosters energy self-sufficiency in rural and Indigenous communities by offering a scalable, low-carbon heating solution that reduces energy poverty and keeps energy spending local.

4.5. Technical Challenges and Limitations

Successful MTES implementation in Glace Bay requires addressing site-specific technical and geochemical risks. The 1B Hydraulic System contains pyrite-rich formations, leading to acid mine drainage (AMD), which causes corrosion, scaling, and ochre formation that can foul heat exchangers and reduce efficiency [

6,

11,

17]. Mitigation includes corrosion-resistant materials, filtration, chemical dosing, and regular water quality monitoring.

Another key risk is thermal short-circuiting between Collieries No. 2 and No. 9, which are only 43 m apart. This proximity may result in reinjected water prematurely returning to extraction wells. Hydrogeological modeling, tracer testing, and optimized well spacing are essential to ensure efficient thermal exchange [

4,

17,

37].

Environmental and geotechnical risks include potential contamination of surface and groundwater, thermal disruption of aquifers, and release of hazardous gases like methane during drilling. Changes in subsurface pressure could also destabilize old mine voids, particularly in undocumented or shallow areas [

14,

17,

29]. International examples, such as Dawdon (UK) and Heerlen (Netherlands), demonstrate that these challenges can be managed with real-time monitoring, adaptive design, and robust site characterization [

4,

17].

4.6. Integration with Renewable Energy

MTES systems function best when integrated with renewable energy sources. Nova Scotia’s legislated targets—80% renewable electricity and 5 GW offshore wind capacity by 2030—create strong alignment opportunities [

63]. MTES can absorb surplus power from intermittent sources and convert it into storable thermal energy, enhancing grid flexibility and seasonal energy balancing.

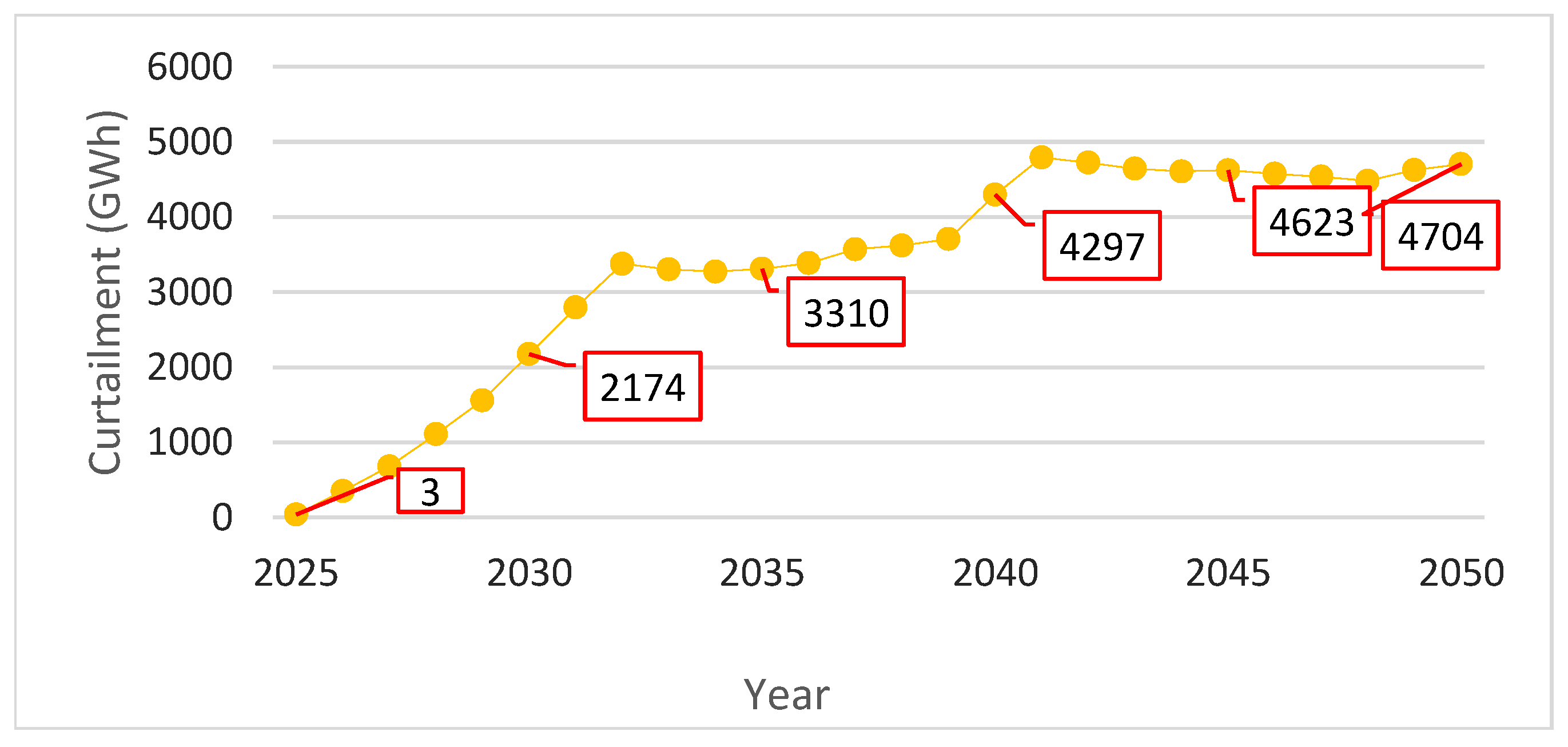

According to Nova Scotia Power’s 2023 Integrated Resource Plan, projected wind and solar curtailment will reach 351 GWh/year by 2025 and 2,175 GWh/year by 2030, highlighting the need for flexible storage systems like MTES [

67] (

Figure 5).

Key renewable energy pathways for MTES integration in Glace Bay include:

Onshore Wind: The Lingan Wind Farm near the Sydney Coalfield generates 36–49 GWh/year [

68], which could meet 37%–50% of Glace Bay’s estimated 52 GWh/year MTES electricity demand (

Section 3.4). However, grid commitments may limit dedicated supply, making further wind expansion essential;

Offshore Wind: The Sydney Bight area has been identified as a key zone for offshore wind development. The 5 GW goal by 2030 could power over 3.7 million households [

69]. Aligning MTES with future offshore capacity would ensure high-COP heat pump operation and utilize forecasted surpluses exceeding 2,000 GWh/year [

67];

Solar Thermal: Seasonal solar thermal integration can further enhance MTES. During low demand months, surplus summer heat can be stored and recovered in winter. The Bochum project in Germany demonstrates how mine voids can serve as seasonal heat reservoirs charged by solar thermal [

8]. Similar applications in Glace Bay—especially at institutional buildings like schools and hospitals—could reduce electric load and improve system efficiency year-round. In addition, solar photovoltaic (PV) could be used to power MTES components such as pumps and control systems.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

This study explored the technical, economic, and environmental feasibility of implementing a Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES) system in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, using flooded mine workings from Collieries No. 2 and No. 9 as underground thermal reservoirs. The results confirm that MTES is a viable and scalable solution for decarbonizing district-scale heating in post-industrial communities, while simultaneously repurposing legacy infrastructure and enhancing local energy resilience.

The estimated total thermal storage capacity of 621 GWh far exceeds Glace Bay’s combined annual heating and cooling demand of approximately 185 GWh, demonstrating strong potential for long-term seasonal storage. The system’s modeled output of 264 GWh/year, supported by high-efficiency heat pumps and a centralized open-loop configuration, confirms the technical capability to meet current and future energy needs. With an annual electricity demand of 52 GWh, MTES systems can be effectively paired with intermittent renewables to absorb excess generation and support grid balancing.

Economically, the system offers a competitive Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) ranging from $21.59 to $30.74 CAD/GJ, resulting in up to 59% savings compared to oil-based heating and up to 49% relative to individual heat pumps. Environmentally, switching to MTES could reduce residential heating emissions by 21,000 to 38,500 tonnes CO₂e annually, depending on the renewable share of Nova Scotia’s electricity grid, thereby supporting the province’s 2030 climate targets and long-term decarbonization.

Future efforts should focus on implementing a pilot-scale project in Glace Bay, prioritizing design optimization, hydrogeological modeling, and corrosion mitigation strategies. Integration with existing and planned wind, solar, and waste heat sources—such as data centers—will be essential for improving system performance and sustainability. Additionally, policy support, funding mechanisms, and the establishment of a regional MTES working group are critical to streamline deployment and replicate this model in other coalfield communities across Nova Scotia.

By advancing MTES, Nova Scotia has the opportunity to lead in sustainable heating innovation while revitalizing post-industrial regions and building a resilient, low-carbon energy future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and L.H.; methodology, S.S.; validation, S.S. and L.H.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S.; resources, L.H.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and L.H.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, L.H.; project administration, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. All sources are publicly available and properly cited within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Nova Scotia Department of Energy (Energy Resource Development Branch), particularly Dr. Trevor Kelly, for his support and provision of resources on Nova Scotia’s mines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAPEX |

Capital Expenditure |

| CO₂e |

Carbon Dioxide Equivalent |

| COP |

Coefficient of Performance |

| GJ |

Gigajoule |

| GWh |

Gigawatt-hour |

| LCOH |

Levelized Cost of Heat |

| MTES |

Mine Thermal Energy Storage |

| OPEX |

Operational Expenditure |

References

- İ. Dinçer and M. A. Rosen, Thermal Energy Storage: Systems and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- D. Banks, An Introduction to Thermogeology: Ground Source Heating and Cooling, John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- M. Bloemendal , "20 million EU Grant for research underground heat storage," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.tudelft.nl/en/2022/citg/20-million-eu-grant-for-research-underground-heat-storage.

- R. Verhoeven, E. Willems, V. Harcouët-Menou, E. D. Boever, L. Hiddes, P. O. ’. Veld and E. Demollin, "Minewater 2.0 project in Heerlen the Netherlands: transformation of a geothermal mine water pilot project into a full scale hybrid sustainable energy infrastructure for heating and cooling," in 8th International Renewable Energy Storage Conference and Exhibition, IRES 2013, 2014.

- Geospatial Research Limited, "Mine-Water Heat," Geospatial Research Limited, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://geospatial-research.com/mine-water-heat/.

- A. M. Jessop, "Geothermal energy from old mines at Springhill, Nova Scotia, Canada," in World Geothermal Congress Proceedings, 1995.

- A. M. Jessop, J. K. Macdonald and S. Roward , "Clean Energy from Abandoned Mines at Springhill, Nova Scotia," Energy Sources, vol. 17, pp. 93-106, 1995. [CrossRef]

- F. Hahn, F. Jagert, G. Bussmann, I. Nardini, R. Bracke, T. Seidel and T. König, "The reuse of the former Markgraf II colliery as a mine thermal energy storage," in European Geothermal Congress 2019, Den Haag, Netherlands, 2019.

- D. Banks, A. Athresh, A. Al-Habaibeh and N. Burnside, "Water from abandoned mines as a heat source: practical experiences of open- and closed-loop strategies, United Kingdom," Sustainable Water Resources Management, vol. 5, p. 29–50, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables, "Nova Scotia’s 2030 Clean Power Plan," Government of Nova Scotia, 2023.

- J. Shea, "The 1B Hydraulic System," in MEND Manitoba Workshop Changes in Acidic Drainage for Operating, Closed or Abandoned Mines, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 2008.

- R. C. Boehner and P. S. Giles, "GEOLOGY OF THE SYDNEY BASIN, CAPE BRETON AND VICTORIA COUNTIES, CAPE BRETON ISLAND, NOVA SCOTIA," Nova Scotia Natural Resources, Halifax, 2008.

- F. E. Baechler, "REGIONAL WATER RESOURCES SYDNEY COALFIELD, NOVA SCOTIA," Province of Nova Scotia, Department of the Environment, Halifax, 1986.

- J. Shea, "MINE WATER MANAGEMENT OF FLOODED COAL MINES IN THE SYDNEY COAL FIELD, NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA," in International Mine Water Conference, Pretoria, 2009.

- West Virginia University, "Geothermal Energy on Abandoned Mine Lands," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scitechpolicy.wvu.edu/science-and-technology-notes-articles/2024/01/08/geothermal-energy-in-abandoned-mine-lands.

- Yousef, "12 DIFFERENT TYPES OF HEAT EXCHANGERS & THEIR APPLICATION [PDF]," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.theengineerspost.com/types-of-heat-exchanger/.

- D. B. Walls, D. Banks, A. J. Boyce and N. M. Burnside , "A Review of the Performance of Minewater Heating and Cooling Systems," energies, vol. 19, no. 14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Banks, "Integration of Cooling into Mine Water Heat Pump Systems," School of Engineering Glasgow University, 2017.

- European Commission, "Case Study- The use of mine water in district heating systems – an example from Heerlen, Netherlands," European Commission, 2024.

- A. J. Kallesøe and T. Vangkilde-Pedersen, "HEATSTORE- Underground Thermal Energy Storage (UTES)– state-of-the-art, example cases and lessons learned," HEATSTORE project report, GEOTHERMICA – ERA NET Cofund Geothermal, 2019.

- R. Verhoeven and F. Hahn, "Mine Thermal Energy Storage (MTES), 2nd European Underground Energy Storage Workshop," Fraunhofer Institution for Energy Infrastructures and Geothermal IEG, Paris, 2023.

- A. Passamonti, F. Hahn, F. Strozyk, P. Bombarda and R. Bracke, "Development of a pilot site for high temperature heat pumps, with high temperature mine thermal energy storage as heat source," in European Geothermal Congress 2022, Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- W. B. Loo, "www.omnicalculator.com/," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.omnicalculator.com/everyday-life/eui.

- K. Anderson, "What is Energy Use Intensity (EUI)?," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://greenly.earth/en-gb/blog/company-guide/what-is-energy-use-intensity-eui.

- A. Al-Habaibeh, A. P. Athresh and K. Parker, "Performance analysis of using mine water from an abandoned coal mine for heating of buildings using an open loop based single shaft GSHP system," Applied Energy, pp. 393-402, 2018. [CrossRef]

- The Engineering ToolBox, "Storing Thermal Heat," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/sensible-heat-storage-d_1217.html.

- Corrosionpedia, "Head Loss," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.corrosionpedia.com/definition/625/head-loss.

- ASHRAE, "Principles of Heating, Ventilating, and Air Conditioning, Ninth Edition," ASHRAE, 2021.

- M. Preene and P. Younger, "Can you take the heat? – Geothermal energy in mining," Mining Technology, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 107-118, 2014. [CrossRef]

- W. Short, D. J. Packey and T. Holt , "A Manual for the Economic Evaluation of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Technologies," National Renewable Energy Laboratory(NREL), 1995.

- Statistics Canada, "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population for Glace Bay," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&DGUIDlist=2021S05100318&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1,4&HEADERlist=0.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Table 2.5 – Average Dwelling Size by Dwelling Type (m2)," 2015. [Online]. Available: https://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/showTable.cfm?juris=CA&page=1&rn=9§or=AAA&type=SHCMA&year=2015.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Residential Sector, Nova Scotia, Table 2: Secondary Energy Use and GHG Emissions by End-Use," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/showTable.cfm?juris=ns&page=0&rn=2§or=res&type=CP&year=2021.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Commercial/Institutional Sector - Atlantic- Secondary Energy Use and GHG Emission," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/showTable.cfm?type=CP§or=com&juris=atl&year=2022&rn=2&page=0.

- Dun & Bradstreet , "Manufacturing Companies In Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada," Dun & Bradstreet business directory, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.dnb.com/business-directory/company-information.manufacturing.ca.nova_scotia.glace_bay.html.

- Energy Star, "Canadian Energy Use Intensity by Property Type," Canadian National Median Values, 2023.

- J. MacSween, C. Raman, R. Kaliaperumal, K. Oaks and M. Mkandawire, "Modeling Potential Impact of Geothermal Energy Extraction from the 1B Hydraulic System of the Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia," in Reliable Mine Water Technology, Golden, Colorado, USA, 2013.

- IEA-ETSAP ; IRENA;, "Heat Pumps- Technology Brief," International Energy Agency (IEA), 2013.

- G. W. Ellerbrok, "The Louis Frost Notes 1685 to 1962, Dominion No. 2 Colliery," 1998. [Online]. Available: https://www.mininghistory.ns.ca/lfrost/lfdn2.htm.

- N. Hall, "Water Side Economizers Part 9: Heat Exchanger Pressure Drop," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.deppmann.com/blog/monday-morning-minutes/water-side-economizers-part-9-heat-exchanger-pressure-drop/.

- H. Robbins, "Cost To Drill A Well [Pricing Per Foot & Cost By State]," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://upgradedhome.com/cost-to-drill-a-well/.

- T. Grupa, "Well Drilling Cost," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://homeguide.com/costs/well-drilling-cost.

- Government of British Columbia, "Guide to Conducting Pumping Tests," 2020.

- Thompson Pump & Irrigation, "Domestic Well Testing: Flow & Purity Tests," Thompson Pump & Irrigation, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.thompsonpumpandirrigation.com/home/eu2jc7l28psicdnz9ljyf149cwdy3z-g4lw6-jalmh-485xg-s7ja2.

- Dunsky Energy Consulting, "The Economic Value of Ground Source Heat Pumps for Building Sector Decarbonization-Review of a recent analysis estimating the costs of electrification in Canada," Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Institute of Canada (HRAI), 2020.

- S. Noel, "Geothermal heat pump cost," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://homeguide.com/costs/geothermal-heat-pump-cost.

- Thunder Said Energy, "Waste heat recovery: heat exchanger costs?," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://thundersaidenergy.com/downloads/waste-heat-recovery-the-economics/.

- T. Nussbaumer and S. Thalmann, "Influence of system design on heat distribution costs in district heating," Energy, vol. 101, p. 496e505, 2016. [CrossRef]

- nPro Energy, "Economic calculation for districts with heat network," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.npro.energy/main/en/help/economic-calculation.

- A. Erickson, "What Price Should You Expect for SCADA Systems and Maintenance?," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.dpstele.com/blog/scada-price-maintenance-cost.php.

- C. Antal and T. Maghiar, "AUTOMATIC CONTROL AND DATA ACQUISITION (SCADA) FOR GEOTHERMAL SYSTEMS," in European Summer School on Geothermal Energy Applications, 2001.

- Job Bank, "Wages in Nova Scotia," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/wagereport/location/ns.

- NS Power, "Tariff 2024," Nova Scotia Power, 2024.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Weekly Average Retail Prices for Furnace Oil in 2025," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www2.nrcan.gc.ca/eneene/sources/pripri/prices_bycity_e.cfm?productID=7&locationID=39&locationID=40&frequency=W&priceYear=2025&Redisplay=.

- Canada Energy Regulator, "Energy conversion tables," 2016. [Online]. Available: https://apps.cer-rec.gc.ca/Conversion/conversion-tables.aspx?GoCTemplateCulture=en-CA#2-2.

- S. Bernath, "Heat Pump Price Guide: How Much You’ll Pay for a New Heat Pump Installed in Canada," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.furnaceprices.ca/heat-pumps/heat-pump-prices/.

- NS Power, "Changes to Power Rates," Feb 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nspower.ca/about-us/regulations/changes-to-power-rates.

- Airtek, "What's The Average Heat Pump Maintenance Cost In Canada?," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://airtekshop.com/blogs/all/average-heat-pump-maintenance-cost-in-canada/.

- E. Roijen and P. O. ‘t Veld, "The Minewaterproject Heerlen - low exergy heating and cooling in practice," in PALENC AIVC 2007, Crete island, Greece, 2007.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Residential Sector, Nova Scotia, Table 21: Heating System Stock by Building Type and Heating System Type," Natural Resources Canada, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/showTable.cfm?type=CP§or=res&juris=ns&year=2022&rn=21&page=0.

- ECCC, "NATIONAL INVENTORY REPORT 1990 –2021: GREENHOUSE GAS SOURCES AND SINKS IN CANADA," Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2023.

- IPCC, "IPCC AR5 – Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis," Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2013.

- Canada Energy Regulator, "Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Nova Scotia," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-nova-scotia.html.

- E. W. Hennick, "Remediation of Abandoned Mine Openings, April 2020 to March 2021," Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables, 2021.

- E. P. Louie , "Writing a Community Guidebook for Evaluating Low-Grade Geothermal Energy from Flooded Underground Mines for Heating and Cooling Buildings," Michigan Technological University, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Coal Authority, "GATESHEAD DISTRICT ENERGY SCHEME," Coal Authority, 2023.

- NS Power, "NS Power's 2022/23 Evergreen IRP Modeling Results," Nova Scotia Power, 2023.

- Membertou Geomatics Consultants , "Lingan 10 MW Wind Farm Project Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study," Government of Nova Scotia, 2009.

- NSNRR, "Nova Scotia Offshore Wind Roadmap," The Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables, 2023.

- Statistics Canada, "Table 1- Profile of energy use by commercial and institutional buildings, all provinces, 2019," Statistics Canada, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220805/t001c-eng.htm.

- UNEP, "DISTRICT ENERGY IN CITIES Unlocking the full potential of energy efficiency and renewable energ," UNEP(United Nation Environmental Programme), 2015.

- Natural Resources Canada, "Heating and Cooling With a Heat Pump," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/energy-efficiency/energy-star/heating-cooling-heat-pump.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).