Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fabrication and curing

2.2.2. Determination of Curing Characteristics

2.2.3. Determination of Cross-Link Density

2.2.4. Investigation of Physical-Mechanical Characteristics

2.2.5. Microscopic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

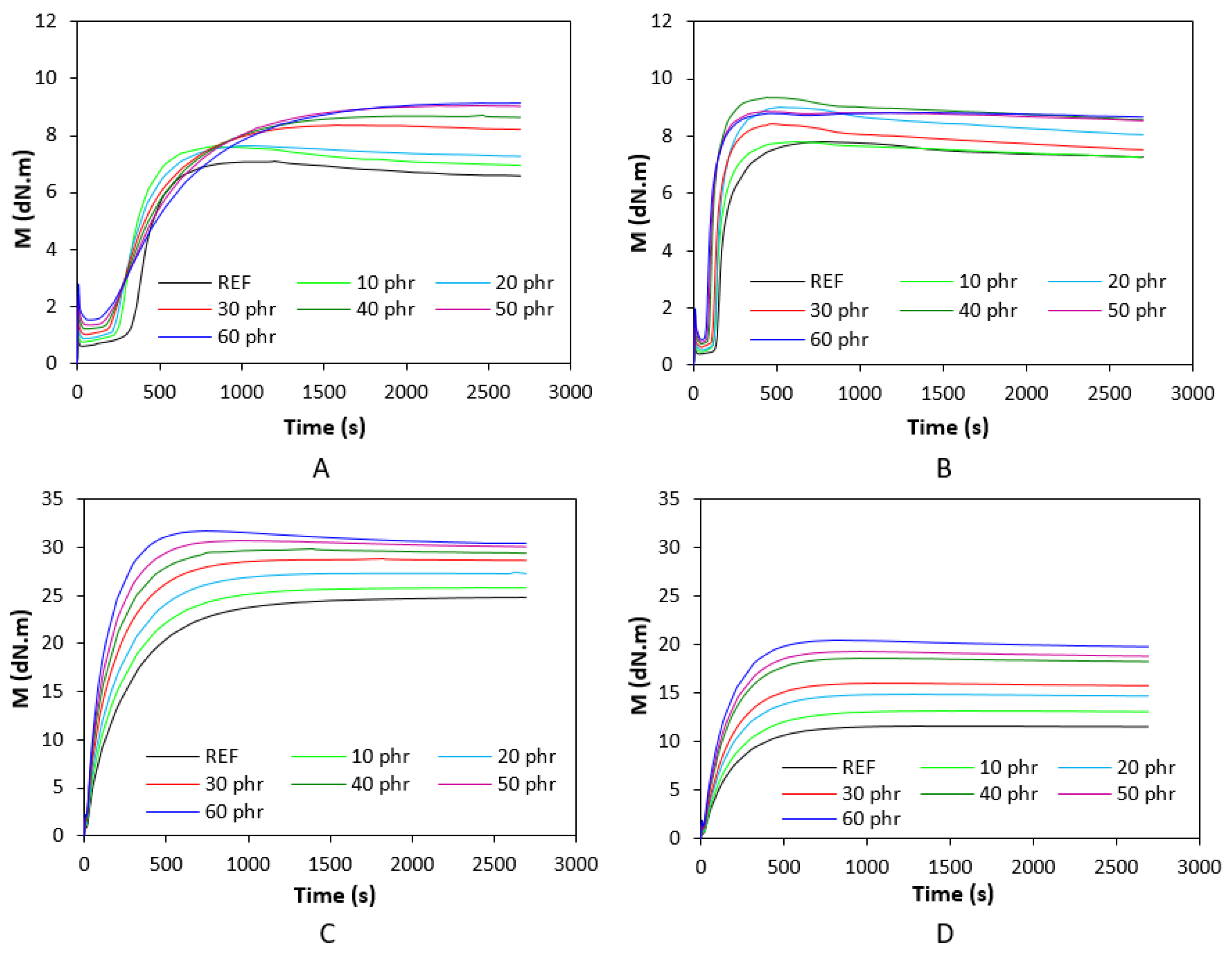

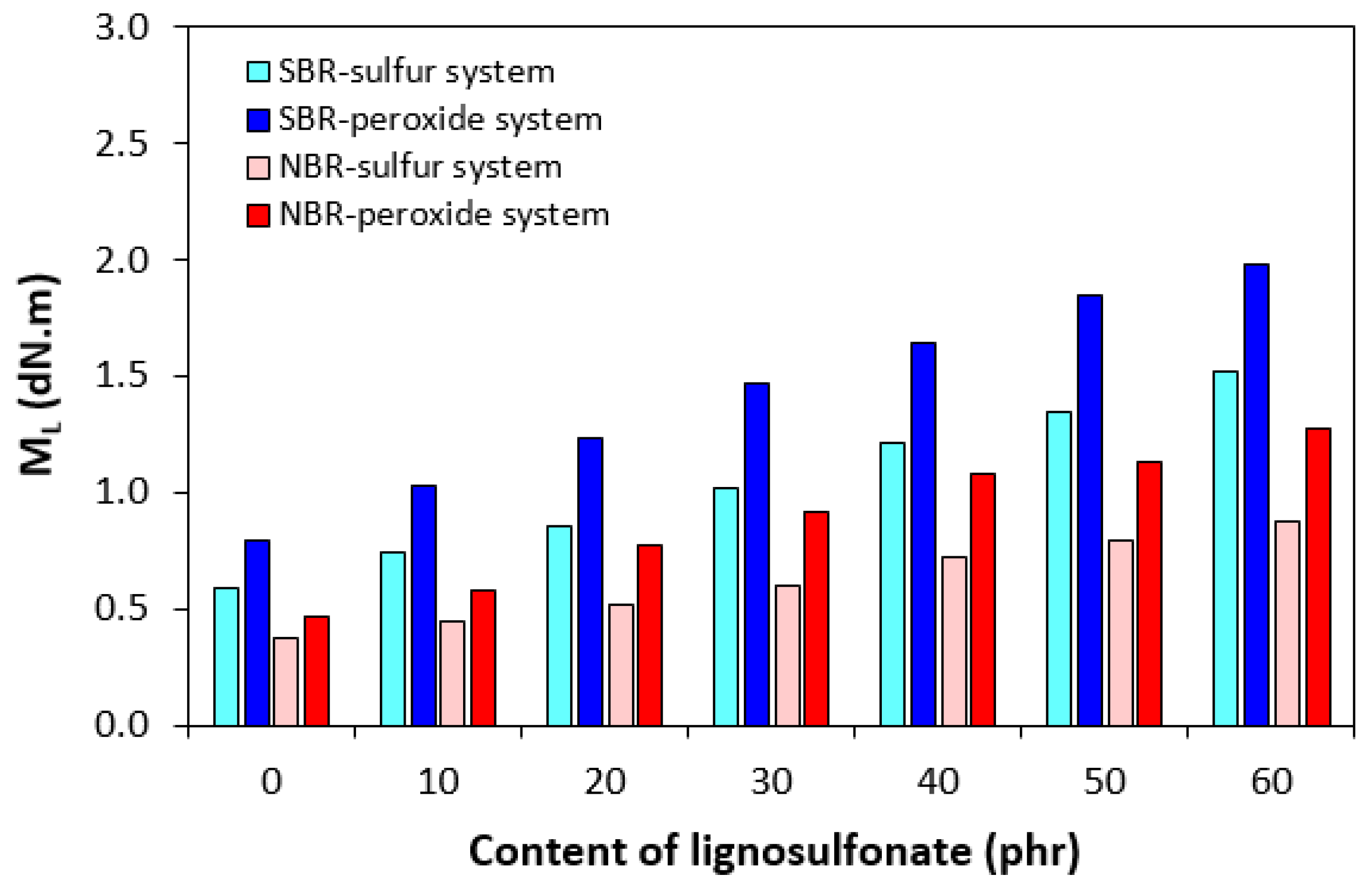

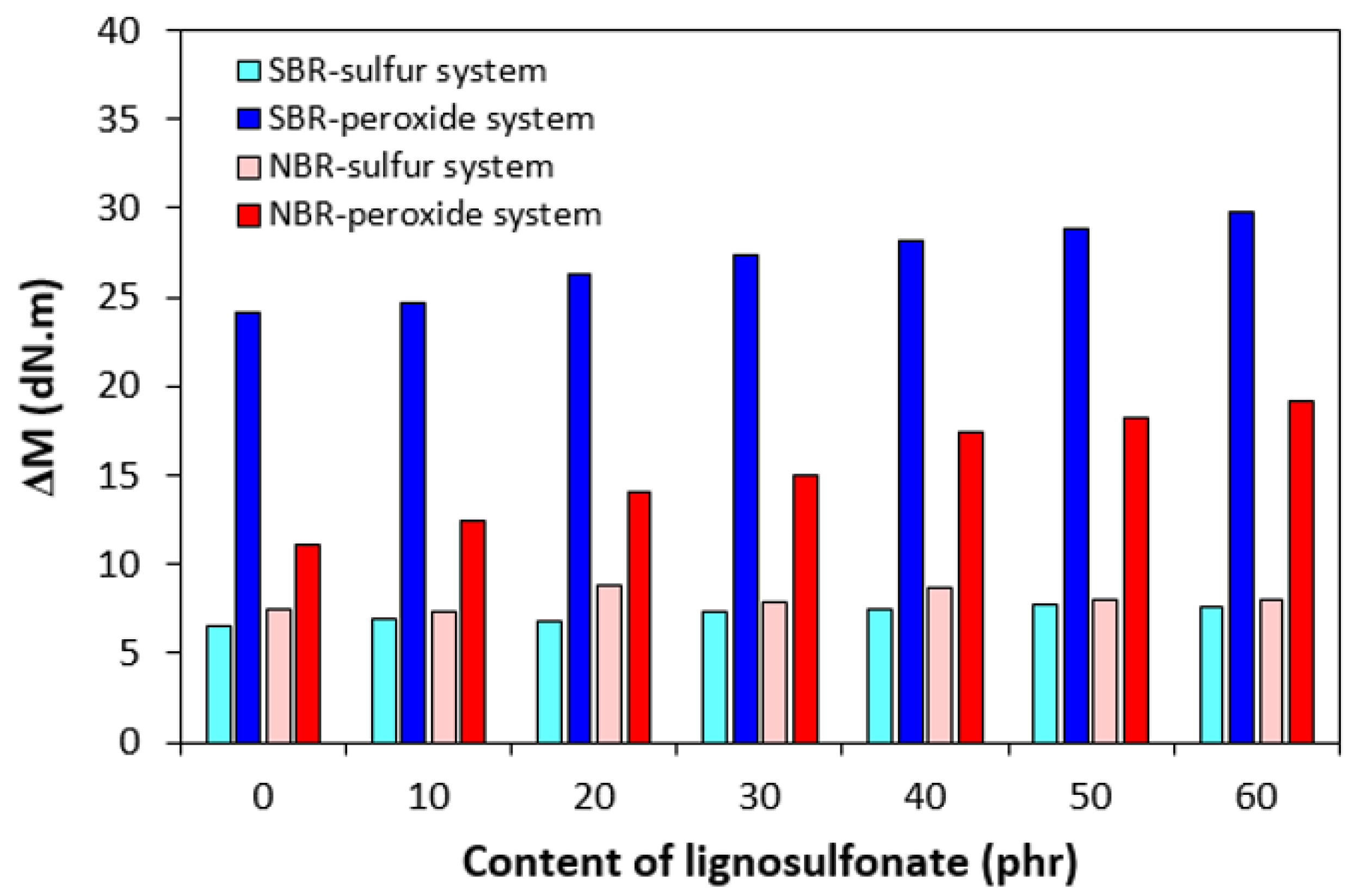

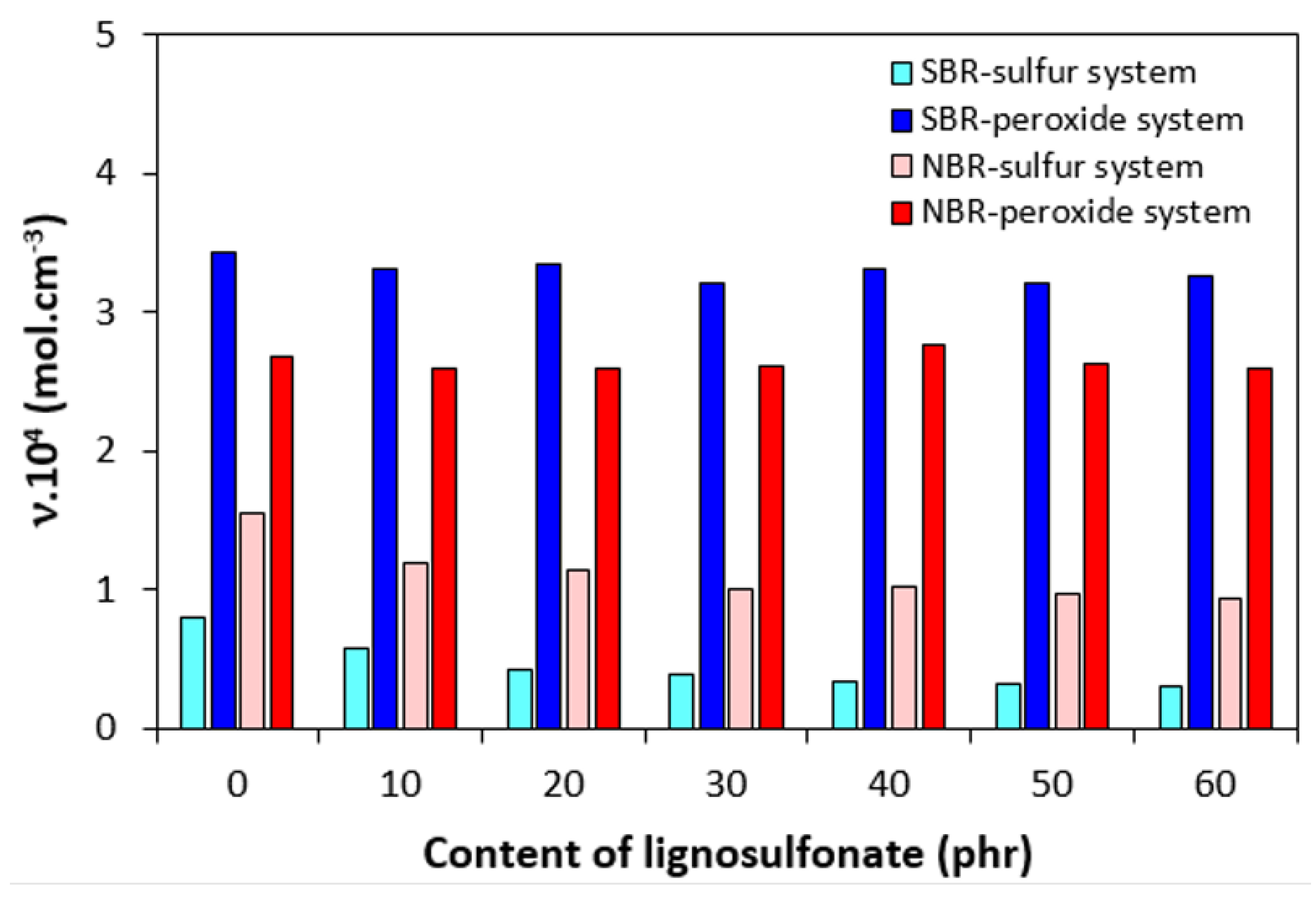

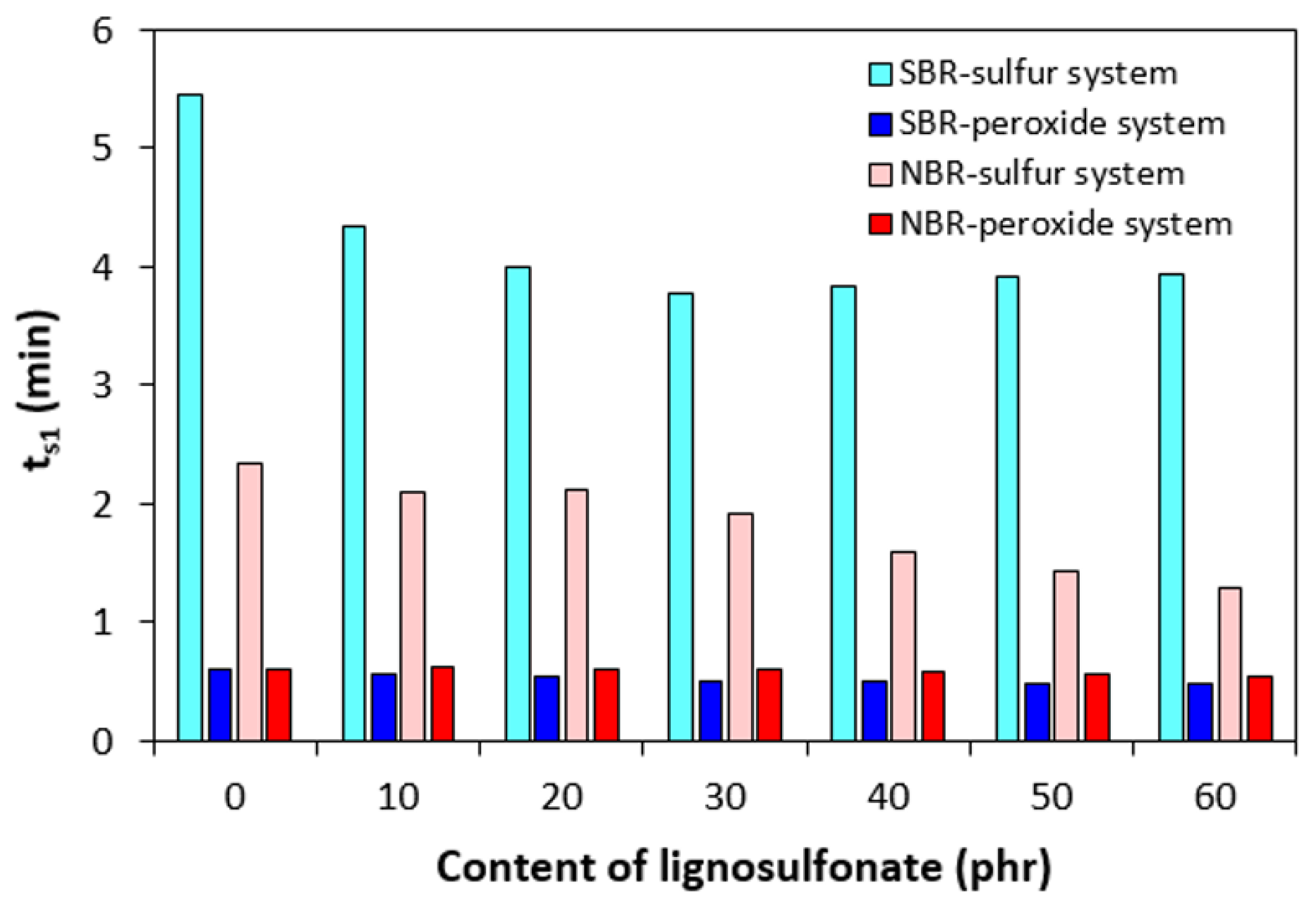

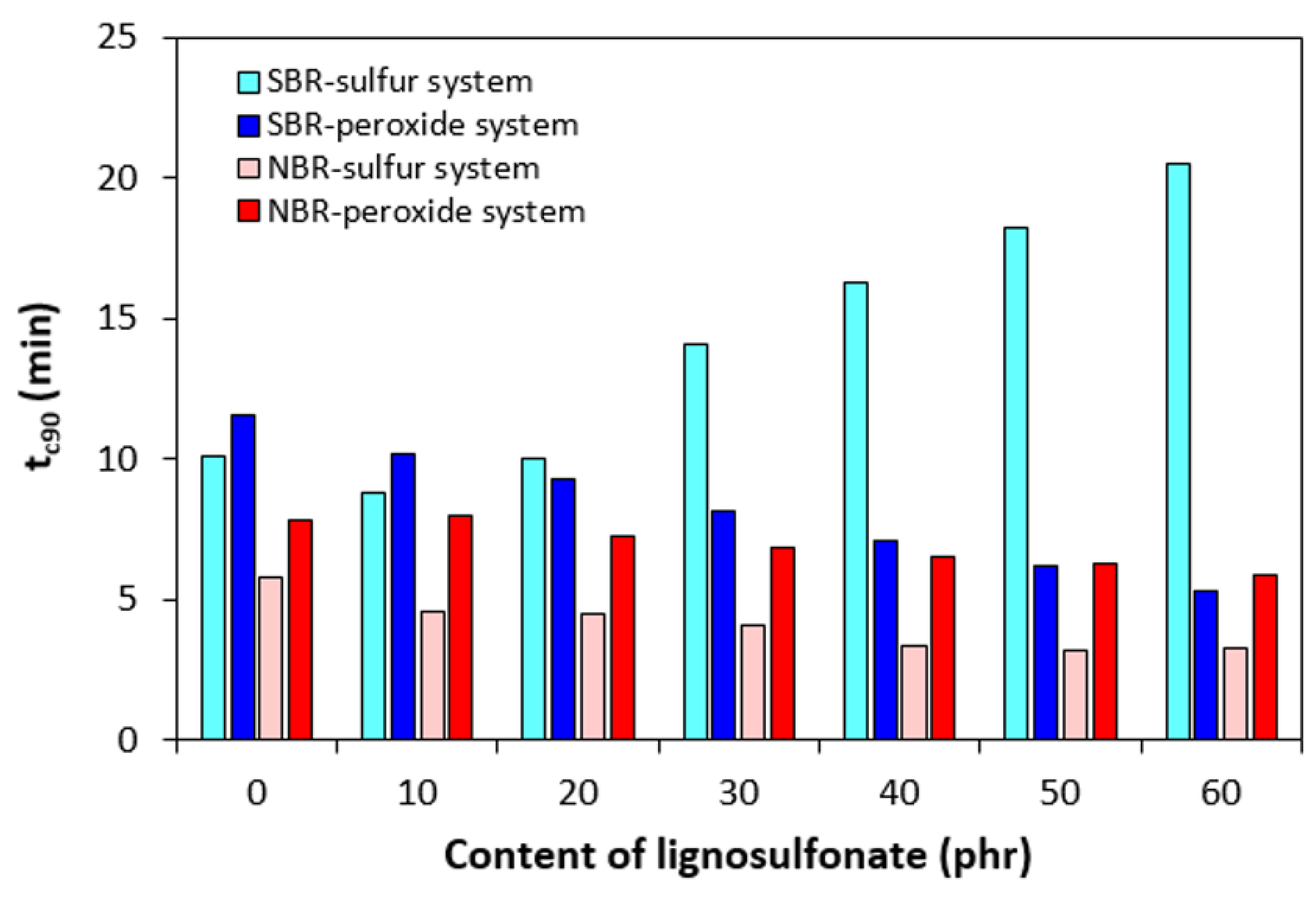

3.1. Curing Process and Cross-Link Density

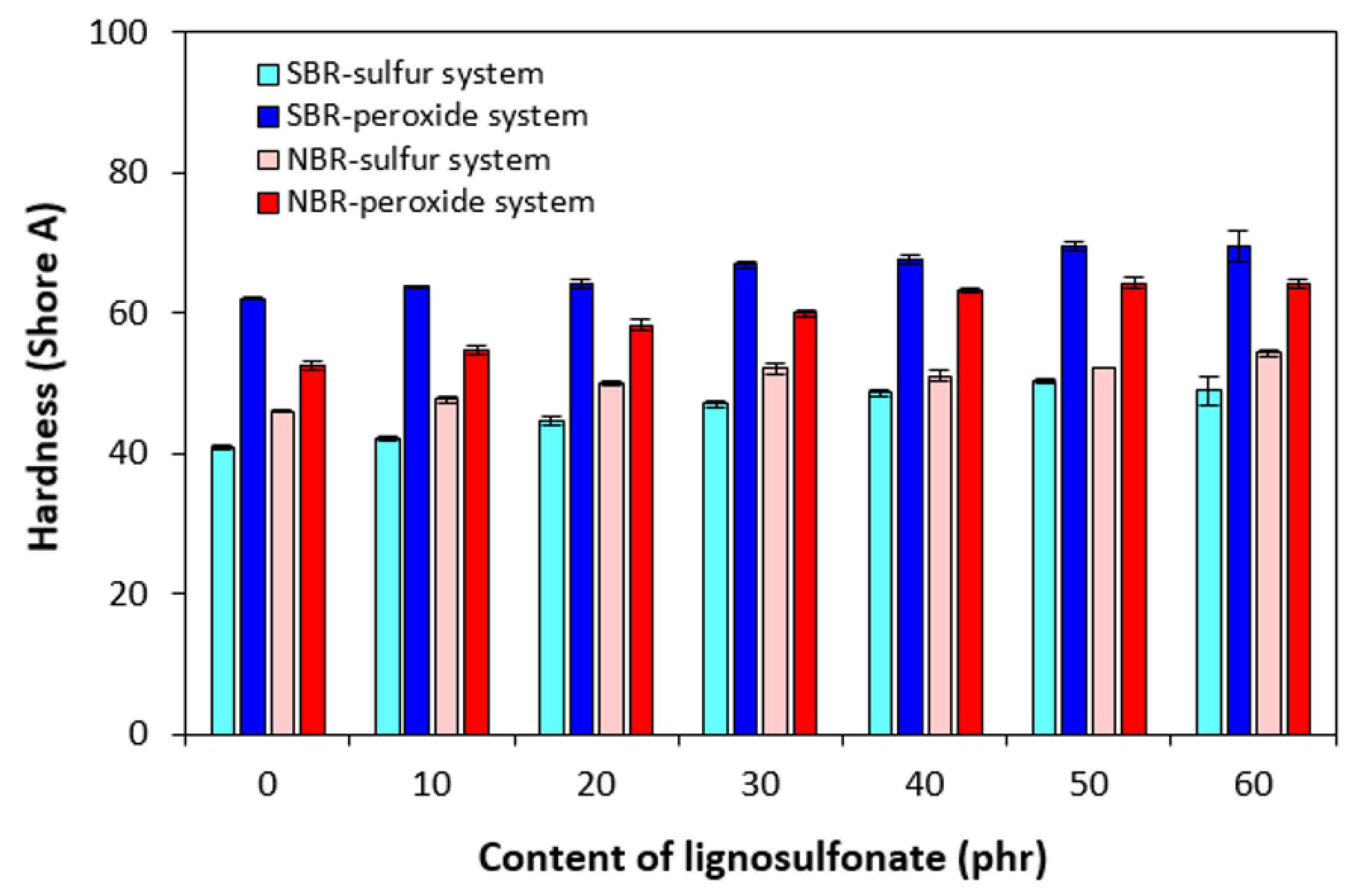

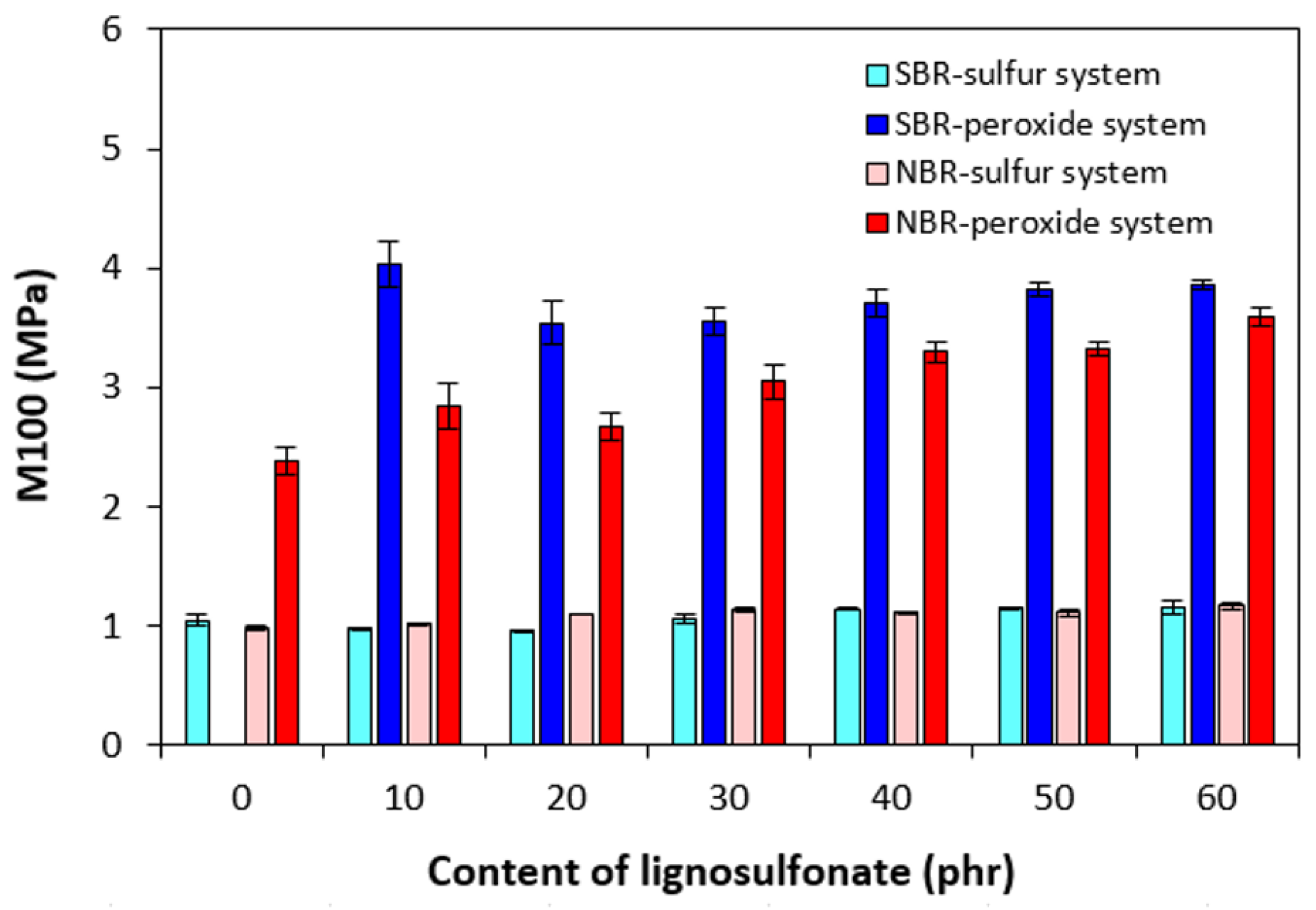

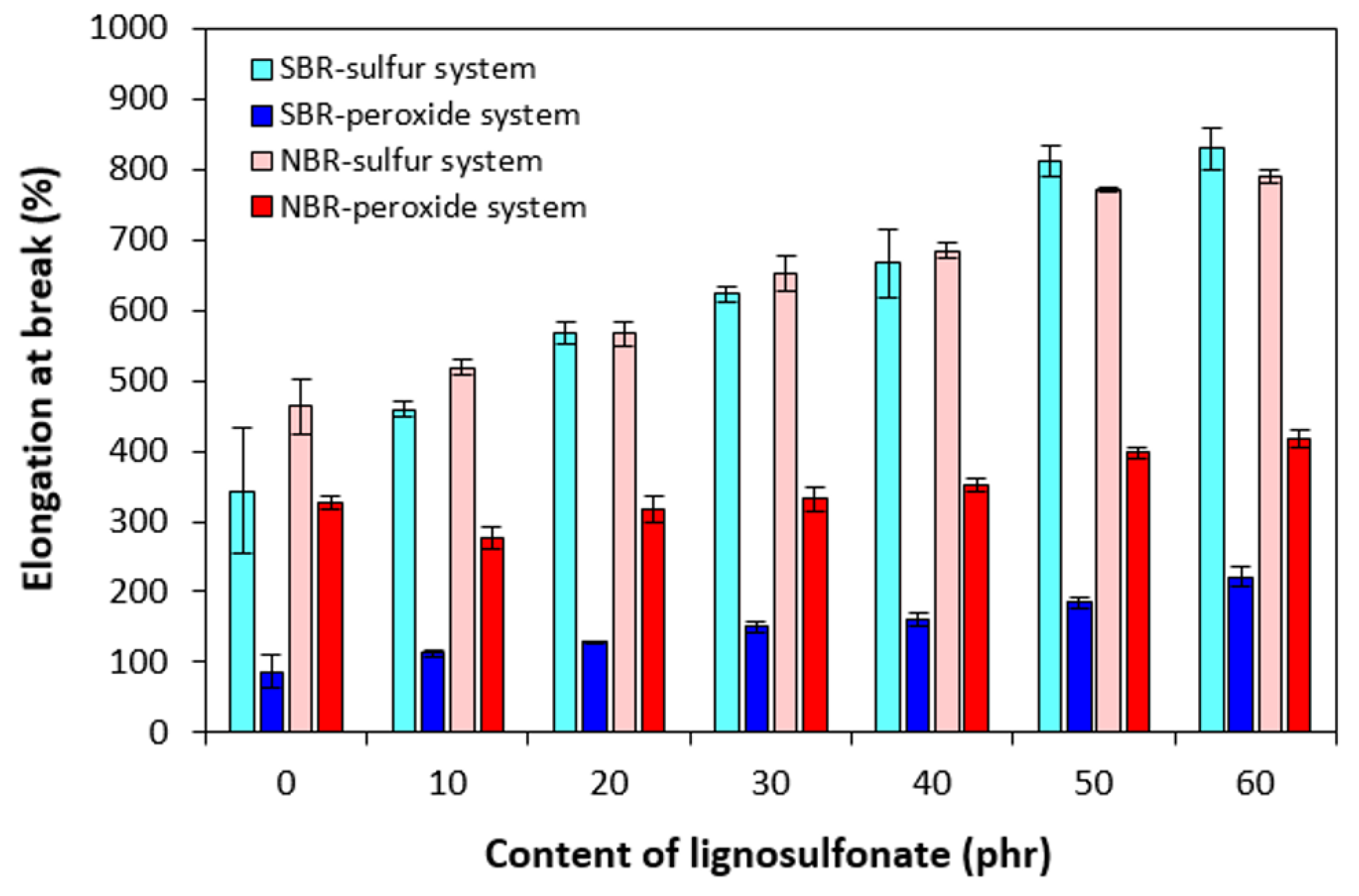

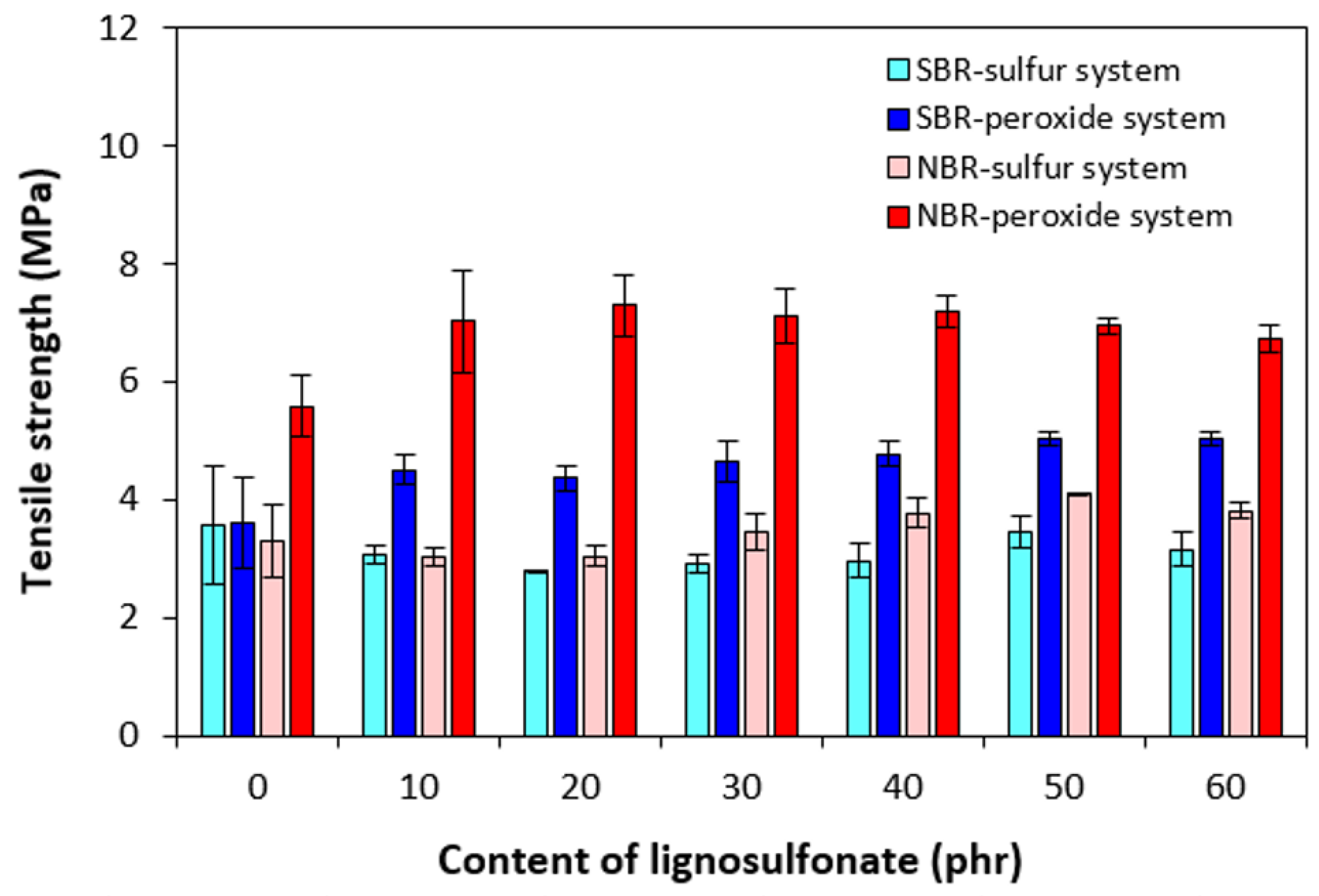

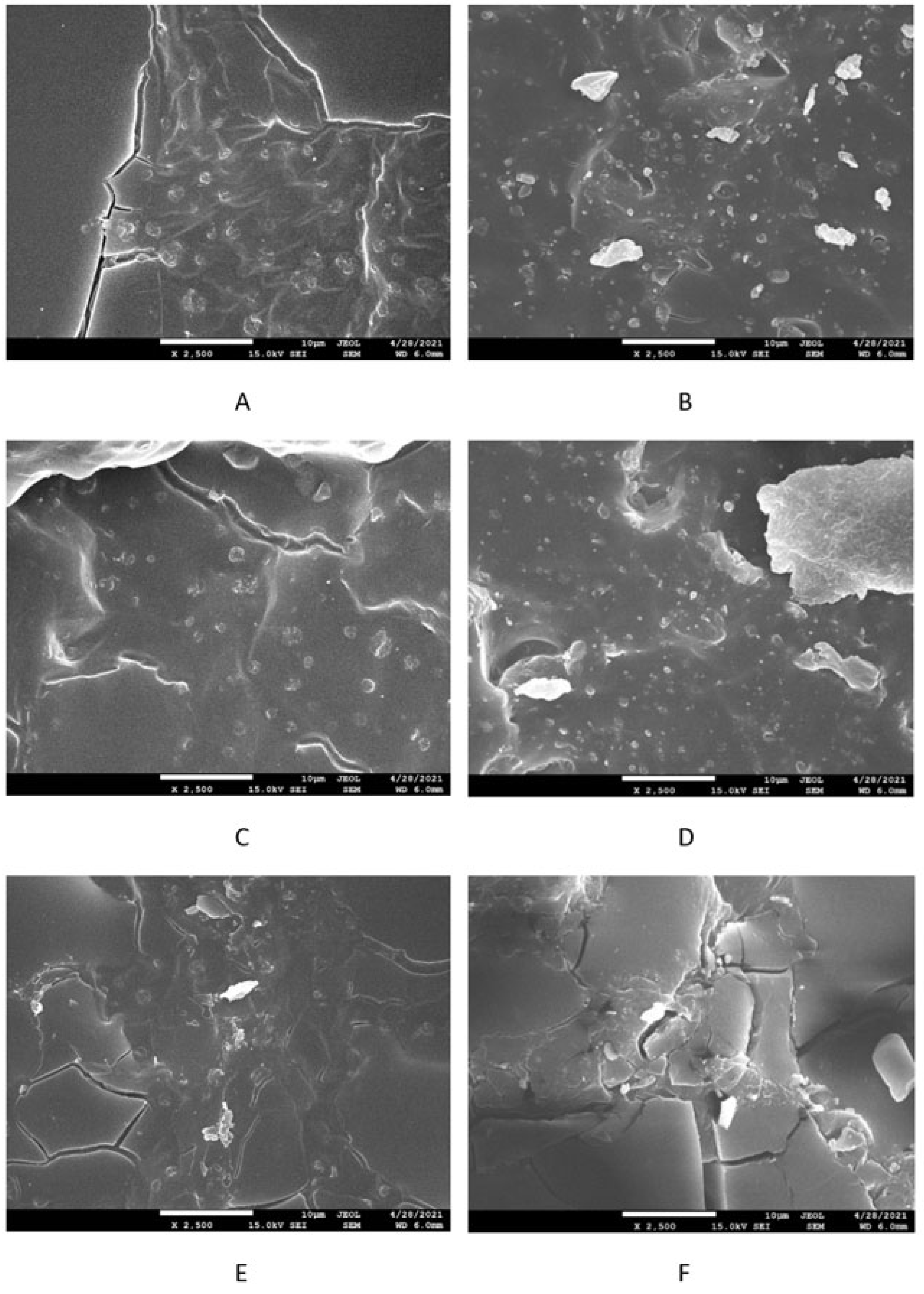

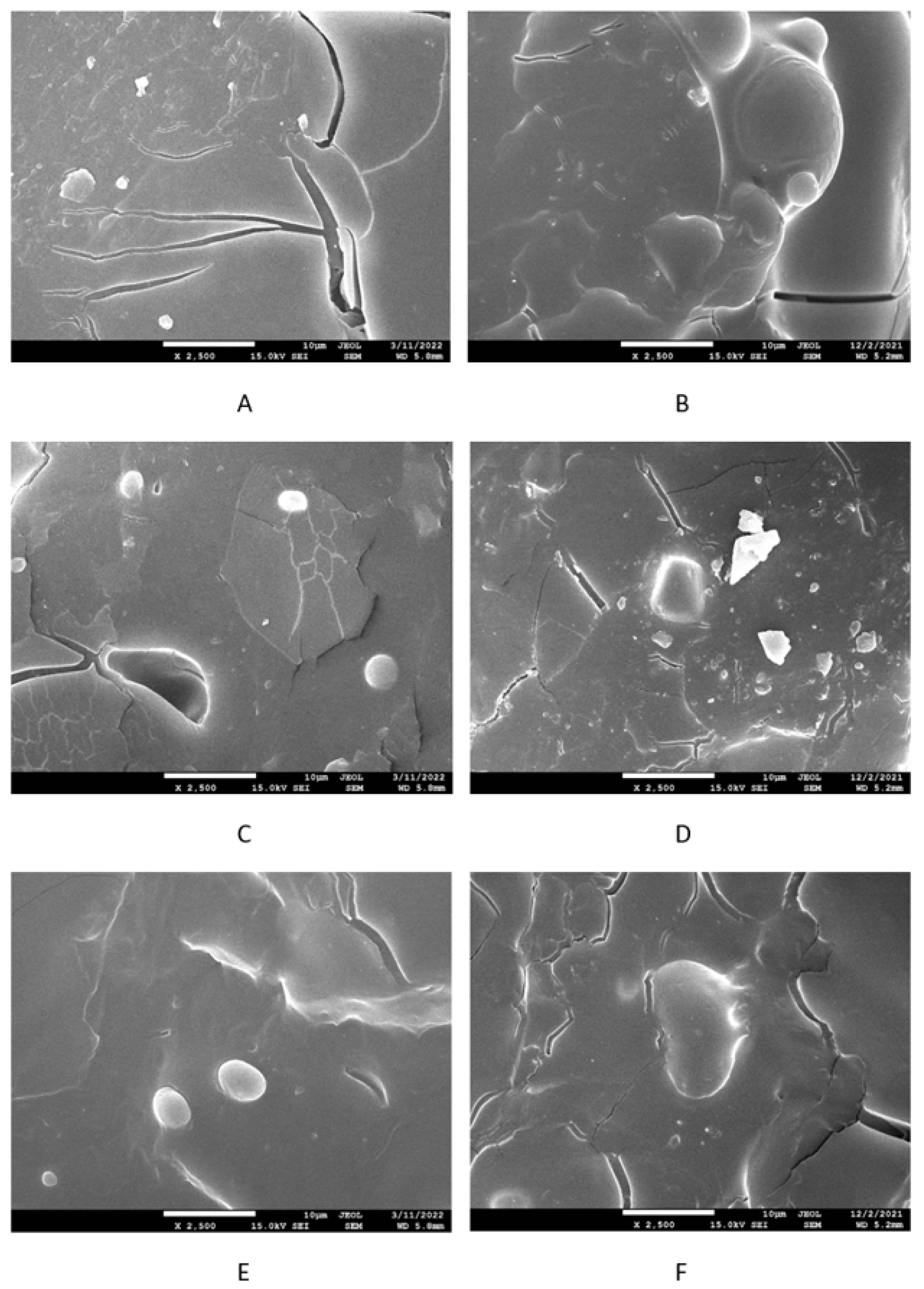

3.2. Physical-Mechanical Properties and Morphology

3.3. Dynamic-Mechanical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Ruwoldt J: A critical review of the physicochemical properties of lignosulfonates: chemical structure and behavior in aqueous solution, at surfaces and interfaces. Surfaces. 2020;3:622-648.

- Hemmilä V, Hosseinpourpia R, Adamopoulos S, Eceiza A: Characterization of wood-based industrial biorefinery lignosulfonates and supercritical water hydrolysis lignin. Waste Biomass Valori. 2020;11:5835-5845. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Gu X, Shi Y: A review on lignin antioxidants: Their sources, isolations, antioxidant.

- activities and various applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;210:716-741.

- Morena AG, Bassegoda A, Natan M, Jacobi G, Banin E, Tzanov T: Antibacterial properties and mechanisms of action of sonoenzymatically synthesized lignin-based nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14:37270-37279. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Qiu X, Liu W, Fu F, Yang D: A novel lignin/ZnO hybrid nanocomposite with excellent UV absorption ability and its application in transparent polyurethane coating. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2017;56:11133-11141. [CrossRef]

- Younesi-Kordkheili H, Pizzi A: A comparison among lignin modification methods on the properties of lignin–phenol–formaldehyde resin as wood adhesive. Polymers. 2021;13:3502. [CrossRef]

- Lisý A, Ház A, Nadányi R, Jablonský M, Šurina I: About hydrophobicity of lignin: A review of selected chemical methods for lignin valorisation in biopolymer production. Energies. 2022;15:6213. [CrossRef]

- Sugiarto S, Leow Y, Li Tan C, Wang G, Kai D: How far is Lignin from being a biomedical material? Bioact. Mater. 2022;8:71-94.

- Fabbri F, Bischof S, Mayr S, Gritsch S, Bartolome MJ, Schwaiger N, Guebitz GM, Weiss R: The biomodified lignin patform: A review. Polymers. 2023;15:1694.

- Saadan R, Alaoui CH, Ihammi A, Chigr M, Fatimi A: A brief overview of lignin extraction and isolation processes: From lignocellulosic biomass to added-value biomaterials. Environ Earth Sci Proc. 2024;31:3.

- Alam MM, Greco A, Rajabimashhadi Z, Corcione CE: Efficient and environmentally friendly techniques for extracting lignin from lignocellulose biomass and subsequent uses: A review. Clean Mater. 2024;13:100253. [CrossRef]

- Shorey R, Salaghi A, Fatehi P, Mekonnen TH.: Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: a review. RSC Sustainability. 2024;2:804. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves S, Ferra J, Paiva N, Martins J, Carvalho LH, Magalhães FD.: Lignosulphonates as an alternative to non-renewable binders in wood-based materials. Polymers. 2021;13:4196. [CrossRef]

- Madyaratri EW, Ridho MR, Aristri MA, Lubis MAR, Iswanto AH, Nawawi DS, Antov P, Kristak L, Majlingová A, Fatriasari W.: Recent advances in the development of fire-resistant biocomposites - a review. Polymers. 2022;14:362. [CrossRef]

- Guterman R, Molinari V, Josef E: Ionic liquid lignosulfonate: Dispersant and binder for preparation of biocomposite materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:13044 –13050.

- Breilly D, Fadlallah S, Froidevaux V, Colas A, Allais F: Origin and industrial applications of lignosulfonates with a focus on their use as superplasticizers in concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2021;301:124065.

- Antov P, Mantanis GI, Savov V: Development of wood composites from recycled fibres bonded with magnesium lignosulfonate. Forests. 2020;11:613.

- Mohamad Aini NA, Othman N, Hussin MH, Sahakaro K, Hayeemasae N.: Lignin as alternative reinforcing filler in the rubber industry: A review. Front Mater. 2020;6:329. [CrossRef]

- Thungphotrakul N, Dittanet P, Loykulnunt S, Tanpichai S, Parpainainar P: Synthesis of sodium lignosulfonate from lignin extracted from oil palm empty fruit bunches by acid/ alkaline treatment for reinforcement in natural rubber composites. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2019;526:012022.

- Kruželák J, Džuganová M, Kvasničáková A, Preťo J, Hronkovič J, Hudec I: Influence of plasticizers on cross-linking process, morphology, and properties of lignosulfonate-filled rubber compounds. Polymers. 2025;17:393.

- An D, Cheng S, Jiang C, Duan X, Yang B, Zhang Z, Li J, Liu Y, Wong CP: A novel environmentally friendly boron nitride/lignosulfonate/natural rubber composite with improved thermal conductivity. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8:4801-4809. [CrossRef]

- Džuganová M, Stoček R, Pöschl M, Kruželák J, Kvasničáková A, Hronkovič J, Preťo J: Strategy for reducing rubber wear emissions: The prospect of using calcium lignosulfonate. Express Polym Lett. 2024;18(12):1277-1290. [CrossRef]

- Nardelli F, Calucci L, Carignani E, Borsacchi S, Cettolin M, Arimondi M, Giannini L, Geppi M, Martini F: Influence of sulfur-curing conditions on the dynamics and crosslinking of rubber networks: A time-domain NMR study. Polymers. 2022;14:767. [CrossRef]

- Kaur A, Fefar MM, Griggs T, Akutagawa K, Chen B, Busfield JJC: Recyclable sulfur cured natural rubber with controlled disulfide metathesis. Commun Mater. 2024;5:212.

- Naebpetch W, Junhasavasdikul B, Saetung A, Tulyapitak T, Nithi-Uthai N: Influence of accelerator/sulphur and co-agent/peroxide ratios in mixed vulcanisation systems on cure characteristics, mechanical properties and heat aging resistance of vulcanised SBR. Plast Rubber Compos. 2016;45(10):436–444.

- Shahrampour H, Motavalizadehkakhky A: The Effects of sulfur curing systems (insoluble-rhombic) on physical and thermal properties of the matrix polymeric of styrene butadiene rubber. Pet Chem. 2017;57(8):700-704. [CrossRef]

- Kruželák J, Sýkora R, Hudec I: Sulphur and peroxide vulcanisation of rubber compounds – overview. Chem Pap. 2016;70(12):1533–1555.

- Rodríguez Garraza AL, Mansilla MA, Depaoli EL, Macchi C, Cerveny S, Marzocca AJ, Somoza A: Comparative study of thermal, mechanical and structural properties of polybutadiene rubber isomers vulcanized using peroxide. Polym Test. 2016;52:117-123. [CrossRef]

- Peidayesh H, Nógellová Z, Chodák I: Effects of peroxide and sulfur curing systems on physical and mechanical properties of nitrile rubber composites: A comparative study. Materials. 2024;17:71. [CrossRef]

- Wei BX, Yi XT, Xiong YJ, Wei XJ, Wu YD, Huang YD, He JM, Bai YP: The preparation and characterization of a carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy resin and EPDM composite using the co-curing method. RSC Adv. 2020;10:20588. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya AB, Gopalan AM, Chatterjee T, Vennemann N, Naskar K: Exploring the thermomechanical properties of peroxide/co-agent assisted thermoplastic vulcanizates through temperature scanning stress relaxation measurements. Polym Eng Sci. 2021;61(10):2466-2476. [CrossRef]

- Laing B, De Keyzer J, Seveno D, Van Bael A: Effect of co-agents on adhesion between peroxide cured ethylene–propylene–diene monomer and thermoplastics in two-component injection molding. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(9):48414.

- Hayichelaeh C, Boonkerd K: Enhancement of the properties of carbon-black-filled natural rubber compounds containing soybean oil cured with peroxide through the addition of coagents. Ind Crop Prod. 2022;187:115306. [CrossRef]

- Kruželák J, Kvasničáková, Hložeková K, Hudec I: Influence of dicumyl peroxide and Type I and II co-agents on cross-linking and physical–mechanical properties of rubber compounds based on NBR. Plast Rubber Compos. 2020;49(7):307-320.

- Zhao X, Cornish K, Vodovotz Y: Synergistic mechanisms underlie the peroxide and coagent improvement of natural-rubber-toughened poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) mechanical performance. Polymers. 2019;11(3):565. [CrossRef]

- Kruželák J, Sýkora R, Hudec I: Vulcanization of rubber compounds with peroxide curing systems. Rubber Chem Technol. 2017;90(1):60-88. [CrossRef]

- Kraus G: Swelling of filler-reinforced vulcanizates. J Appl Polym Sci. 1963;7:861-871.

- Hosseini SM, Razzaghi-Kashani M: On the role of nano-silica in the kinetics of peroxide vulcanization of ethylene propylene diene rubber. Polymer. 2017;133:8-19.

- Nikolova S, Mihaylov M, Dishovsky N: Mixed peroxide/sulfur vulcanization of ethylene-propylene terpolymer based on composites. Curing characteristics, curing kinetics and mechanical properties. J Chem Technol Metall. 2022;57(5):881-894.

- Wang H, Zhuang T, Shi X, Van Duin M, Zhao S: Peroxide cross-linking of EPDM using moving die rheometer measurements. II: Effects of the process oils. Rubber Chem Technol. 2018;91(3):561–576.

- George B, Alex R: Stable free radical assisted scorch control in peroxide vulcanization of EPDM. Rubber Sci. 2013;27(1):135–145.

- Kruželák J, Kvasničáková A, Hudec I: Peroxide curing systems applied for cross-linking of rubber compounds based on SBR. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res. 2020;3:120-128. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhou T, Liu Y, Zhang A, Yuan C, Zhang W: Cross-linking process of cis-polybutadiene rubber with peroxides studied by two-dimensional infrared correlation spectroscopy: a detailed tracking. RSC Adv. 2015;5:10231-10242. [CrossRef]

- Valentín JL, Posadas P, Fernández-Torres A, Malmierca MA, González L, Chassé W, Saalwächter K: Inhomogeneities and chain dynamics in diene rubbers vulcanized with different cure systems. Macromolecules. 2010;43:4210–4222. [CrossRef]

- González L, Rodríguez A, Marcos-Fernández A, Valentín JL, Fernández-Torres A: Effect of network heterogeneities on the physical properties of nitrile rubbers cured with dicumyl peroxide. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103(5):3377-3382. [CrossRef]

- Charoeythornkhajhornchai P, Samthong Ch, Somwangthanaroj A: Influence of sulfenamide accelerators on cure kinetics and properties of natural rubber foam. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017;134:44822.

- Ghosh J, Ghorai S, Jalan AK, Roy M, De D: Manifestation of accelerator type and vulcanization system on the properties of silica-reinforced SBR/devulcanize SBR blend vulcanizates. Adv Polym Technol. 2018;37:2636–2650. [CrossRef]

- Lian Q, Li Y, Li K, Cheng J, Zhang J: Insights into the vulcanization mechanism through a simple and facile approach to the sulfur cleavage behavior. Macromolecules. 2017;50(3):803–810. [CrossRef]

- Nikolova S, Mihaylov M, Dishovsky N: Mixed peroxide/sulfur vulcanization of ethylene-propylene terpolymer based composites. Curing characteristics, curing kinetics and mechanical properties. J Chem Technol Metall. 2022;57(5):881-894.

- Strohmeier L, Balasooriya W, Schrittesser B, van Duin M, Schlögl S: Hybrid in situ reinforcement of EPDM rubber compounds based on phenolic novolac resin and ionic coagent. Appl Sci. 2022;12:2432. [CrossRef]

- Siaw C, Baharulrazi N, Che Man SH, Othman N: Effect of zinc dimethacrylate concentrations on properties of emulsion styrene butadiene rubber/butadiene rubber blends. Plast Rubber Compos. 2023;52(6):315-329. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Yuan Z, Ye L: Facile construction of enhanced multiple interfacial interactions in EPDM/zinc dimethacrylate (ZDMA) rubber composites: Highly reinforcing effect and improvement mechanism of sealing resilience. Compos A: Appl Sci. 2019;126:105580. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Gu N, Hu S, Jin R, Zhang J.: Preparation and properties of zinc-diacrylate-modified montmorillonite/rubber nanocomposite. Appl Mech Mater. 2012;182-183:47-51. [CrossRef]

- Henning SK, Costin R.: Fundamentals of curing elastomers with peroxides and coagents. Rubber World. 2006;233:28-35.

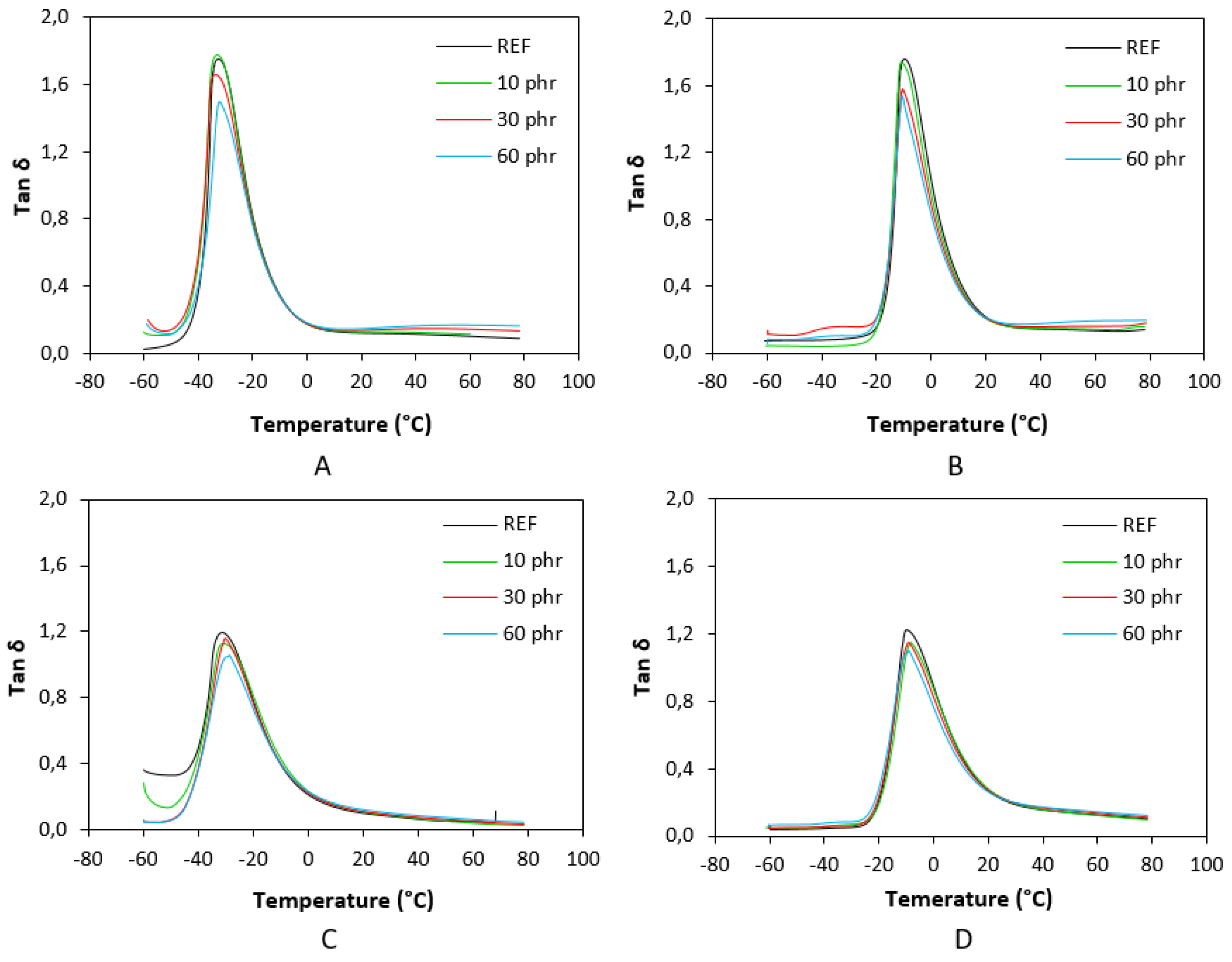

| Lignosulfonate (phr) | Tg (°C) |

tan δ (-50 °C) |

tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (50 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -32.4 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| 10 | -33.0 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| 30 | -33.6 | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| 60 | -32.4 | 0.12 | 0.77 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Lignosulfonate (phr) | Tg (°C) |

tan δ (-50 °C) |

tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (50 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -31.3 | 0.33 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| 10 | -30.7 | 0.14 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| 30 | -30.4 | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| 60 | -28.9 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Lignosulfonate (phr) | Tg (°C) |

tan δ (-50 °C) |

tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (50 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -9.8 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 1.03 | 0.21 | 0.13 |

| 10 | -10.9 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| 30 | -10.7 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.88 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| 60 | -10.7 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| Lignosulfonate (phr) | Tg (°C) |

tan δ (-50 °C) |

tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (50 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -10.1 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| 10 | -8.2 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.14 |

| 30 | -8.9 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.83 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

| 60 | -8.9 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).