1. Introduction

Traditional elastomer materials have found application in many areas of industrial and social life and significantly improved the quality of human life. Due to the increasing demand for polymers and rubber based products, and due to the fact that polymers origin from petroleum based sources, there has been an increasing concern arising from negative impact of these materials on the environment. The lack of degradability, safety and health problems, as well as accumulation of polymer waste in the surrounding has led the awareness towards production of sustainable and ecofriendly material alternatives [

1].

On the way for production of greener and more sustainable polymer products is the utilization of natural macromolecules as fillers or components in polymers matrices. Starch, lignin or cellulose represent favorable raw materials for fabrication of multifunctional, biodegradable polymers [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Lignin is the second most abundant bioorganic material on earth after cellulose. It exhibits amorphous, highly branched aromatic structure consisting of guaiacyl, syringyl and p-hydroxyphenyl units. In addition, it contains several functional groups, methoxyl, carboxyl, aliphatic or phenolic hydroxyls [

6,

7]. Lignin exhibits impressive properties, including high mechanical stability, good physical-mechanical characteristics, adhesive, antioxidant, anti-UV or antimicrobial properties [

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, it has high thermal stability and diverse possible modifications. Despite that, only 2 % of industrially obtained lignin is commercially utilized to produce value added products. High availability, environmental friendliness, biodegradability, and reinforcing capability make it a suitable candidate as a filler or component for rubber compounds to form novel green composite materials. Though, due to its polar nature and formation of strong intramolecular interactions between the macromolecular chains, its compatibility and adhesion with non-polar polymers is usually weak. Therefore, the incorporation of lignin in its original, unmodified form into polymer compounds is usually connected with deterioration of physical-mechanical and utility properties of the final materials.

To improve the properties of lignin based rubber composites, the combination of the biopolymer with traditional fillers used in rubber technologies has been performed [

13,

14,

15]. Bahl et. al. in its study [

16] investigated hybrid fillers based on carbon black and lignin on viscoelastic dissipation and physical-mechanical properties of rubber compounds based on styrene-butadiene rubber. The results revealed that the tensile strength of the composite with hybrid filler in lignin to carbon black ratio 10 to 90 (30 phr) was close to that of the equivalent composite filled only with carbon black (30 phr). The study demonstrated the formation of

∏ -

∏ interactions between both fillers, and the process subdues the networking of carbon black by filling the space between carbon black particles and formation of lignin coating layer. The experimental work performed by Yu et al. [

17] demonstrated that composite containing 30 phr of silica and 20 phr of lignin in hybrid filler was found to have the optimal overall physical-mechanical characteristics. Simultaneously, this composite possessed low rolling resistance and high wet grip properties, which seems to be very promising for green tyre technology.

Another approach for improvement the utility properties of the rubber products is the modification of the biopolymer to enhance the adhesion on the interfacial region between lignin and the rubber matrix. Ferruti at al. [

18] performed methacrylation of lignin through mechanochemistry, resulting in an additional functionalization for phenolic and aliphatic hydroxyl groups. The modified lignin was coprecipitated with natural rubber latex and tested as a reinforcing agent in model sidewall and tread compounds. It was revealed that modified lignin was covalently bonded to rubber chains during curing process. This resulted in higher compatibilization, dispersion, and stiffness when compared to the composite filled with unmodified lignin. Shorey at al. [

19] used a novel silylation reaction to modify kraft lignin to increase its hydrophobicity and subsequent dispersion in natural rubber. The incorporation of 5 wt.% modified lignin into natural rubber matrix resulted in over 44 % increase of tensile strength. The increase in elastic moduli and Payne effect intensity was observed at higher biopolymer content. Hait with his collective [

20] introduced “in-situ surface modification of lignin utilizing a thermo-chemo-mechanical approach” during which they incorporated kraft lignin and surface modifier, (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane into rubber compounds. The resulting composite demonstrated significant improvement in tensile strength (around 15 MPa) when compared to the gum vulcanizate (1-2 MPa). Simultaneously, the composite showed a higher degree of reinforcement than a passenger car tyre model compound comprised of silica and coupling agent - polysulfide based silane at a similar filler loading. Sekar et al. [

21] investigated hydrothermally treated lignin as a potential functional filler for butadiene and styrene butadiene rubber compounds. Bis(triethoxysilylpropyl)tetrasulfide silane was used as a coupling agent for “in situ” surface compatibilization of lignin and for improvement of adhesion between the filler and the rubber matrix. The results showed that modified lignin exhibited semi-reinforcing behavior. Aini et al. [

22] in their work used hydroxymethylation to improve the adhesion between lignin and natural rubber/polybutadiene rubber based compounds. It was shown that hydroxymethylation resulted in much higher compatibility on the filler-rubber interface and subsequent improvement in mechanical properties (tensile properties, compression set, and hardness) of composites.

The various modification techniques to improve dispersion of lignin in rubber matrices and compatibility between both components have been described in several other studies, too [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The results have demonstrated very promising prospects and pointed out to high application potential of lignin into rubber compounds. Though, a lot of modification procedures are time consuming and require extra expenses. Sometimes it is worth using a simple solution to improve homogeneity and compatibility between the components of rubber blends, mainly for those fabricated in industrial scale. To improve adhesion and homogeneity between the rubber and the biopolymer in the current work, four low molecular weight polar plasticizers were used, namely 1,4-butanediol, ethylene glycol and two types of glycerol (with 99% purity and in form of 86% water solution). Those plasticizers are highly available and cost effective. They have been chosen due to their polarity, as calcium lignosulfonate and NBR are polar materials. It is well known that low molecular weight hydrophilic substances are suitable plasticizers for polar based rubber formulations. The main aim of using the plasticizers was to improve the dispersion of the biopolymer within the rubber matrix and to enhance the compatibility between both components.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber NBR, type SKN 3345 (acrylonitrile content 31-35 %) was supplied from Sibur International, Russia. Calcium lignosulfonate (Borrement CA120) provided by Borregaard Deutschland GmbH, Germany was used as a biopolymer component and was dosed to the rubber compounds in constant amount – 50 phr. The average molecular weight of lignosulfonate was 24 000 g.mol-1. In addition to carbon (46.63 wt.%), lignosulfonte consisted of hydrogen (5.35 wt.%), sulfur (5.62 wt.%), and nitrogen (0.14 wt.%). The amount of hydroxyl groups was equal to 1.56 wt.%. 1,4-butanediol (99%), ethylene glycol (99%), glycerol (99%) glycerol in form of 86% water solution (glycerol 86%) were applied into rubber formulations as plasticizers in concentration scale ranging from 5 to 30 phr. All plasticizers were delivered from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Sulfur based curing system consisting of 3 phr zinc oxide and 2 phr stearic acid (Slovlak, Košeca, Slovakia) as activators, 1.5 phr accelerator N-cyclohexyl-2-benzothiazole sulfenamide CBS (Duslo, Šaľa, Slovakia) and 3 phr sulfur (Siarkopol, Tarnobrzeg, Poland) was used for cross-linking of rubber compounds.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation and Curing of Rubber Compounds

The rubber formulations were fabricated by using a laboratory kneading machine Brabender (Brabender GmbH & Co. KG, Duisburg, Germany) in two mixing steps at a temperature 90 °C and 55 rpm. The fabrication process is summarized in

Table 1. After each step, the compounds were homogenized and sheeted in a two-roll mill.

The curing process was performed at 170 ºC and pressure of 15 MPa in a hydraulic press Fontijne (Fontijne, Vlaardingen, Holland) following the optimum cure times. After curing, thin sheets with dimensions 15 x 15 cm and thickness 2 mm were obtained.

2.2.2. Determination of Curing Characteristics

Curing characteristics were determined from corresponding curing isotherms, which were investigated in an oscillatory rheometer MDR 2000 (Alpha Technologies, Akron, Ohio, USA).

The investigated curing parameters were:

ML - minimum torque (dN.m)

MH - maximum torque (dN.m)

∆M (dN.m) - torque difference, the difference between MH and ML

tc90 (min) - optimum curing time

ts1 (min) - scorch time

R (dN.m.min

-1) – curing rate, defined as:

Mc90 (dN.m) – torque at tc90

Ms1 (dN.m) – torque at ts1

2.2.3. Determination of Cross-Link Density

The cross-link density

ν was determined based on equilibrium swelling of vulcanizates in xylene. The weighted dried samples were placed into xylene in which they swelled within time. The weight of samples was measured every hour until the equilibrium swelling was reached. During the measurement, the solvent diffuses into rubber and disrupts physical interactions between the chain segments. The result is the determination of chemical cross-link density, i.e. the concentration of chemical cross-links within the rubber matrix. The experiments were carried out at a laboratory temperature and swelling time was equal to 30 hours. The Flory-Rehner equation modified by Krause [

28] was then used to calculate the cross-link density based upon the equilibrium swelling state.

2.2.4. Rheological Measurements

Dynamic complex viscosity was investigated using RPA 2000 (Alpha Technologies, Akron, Ohio, USA). The samples were analyzed under strain amplitude from 0.15 to 700 % at a constant frequency of 0.2 Hz and temperature 90 ºC.

2.2.5. Investigation of Physical-Mechanical Characteristics

Zwick Roell/Z 2.5 appliance (Zwick GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany) was used to evaluate tensile properties of vulcanizates. The tests were performed in accordance with the valid technical standards and the cross-head speed of the measuring device was set up to 500 mm.min-1. Dumbbell-shaped test samples (width 6.4 mm, length 80 mm, thickness 2 mm) were used for measurements. The hardness was measured by using durometer and was expressed in Shore A.

2.2.6. Microscopic Analysis

The surface morphology and microstructure were observed using scanning electron microscope JEOL JSM-7500F (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The samples were first cooled down in liquid nitrogen under glass transition temperature and then fractured into small fragments with surface area of 3 x 2 mm. The fractured surface was covered with a thin layer of gold and put into the microscope. The source of electrons is cold cathode UHV field emission gun, the accelerate voltage ranges from 0.1 kV to 30 kV and the resolution is 1.0 nm at 15 kV and 1.4 nm at 1 kV. SEM images are captured by CCD-Camera EDS (Oxford INCA X-ACT).

2.2.7. Blooming Test

To observe the blooming of plasticizers, small samples with dimensions 1 x 1 cm were washed with ethanol, dried and weighted one day after curing process. Subsequently, the samples were hung on the hook and placed in the oven at 70 °C. The samples were taken out of the oven, washed with ethanol and weighed after 2, 5 and 24 hours. The blooming was calculated as the specific weight loss of the samples related to the surface of the test specimens.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Curing Process and Cross-Link Density

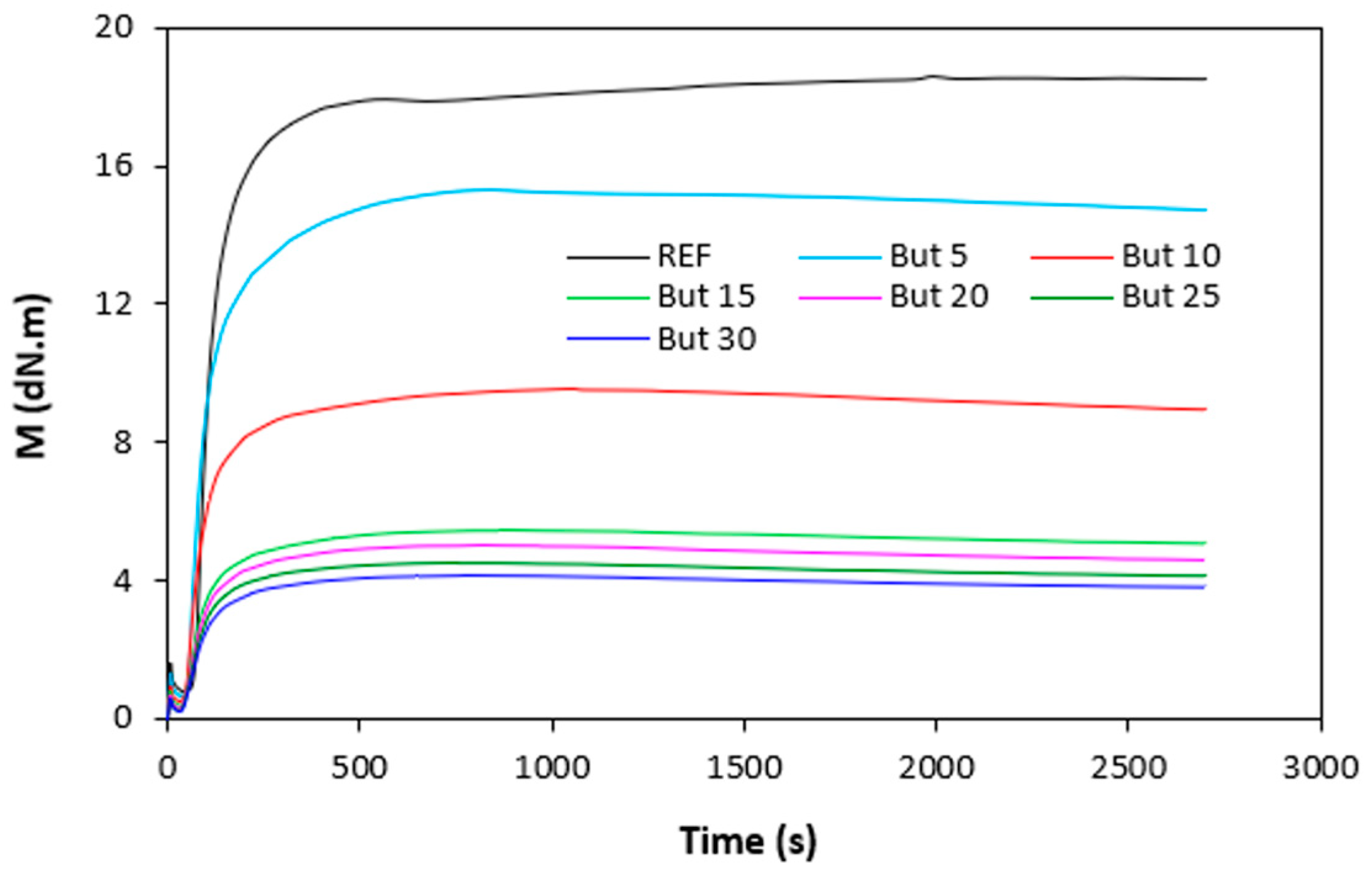

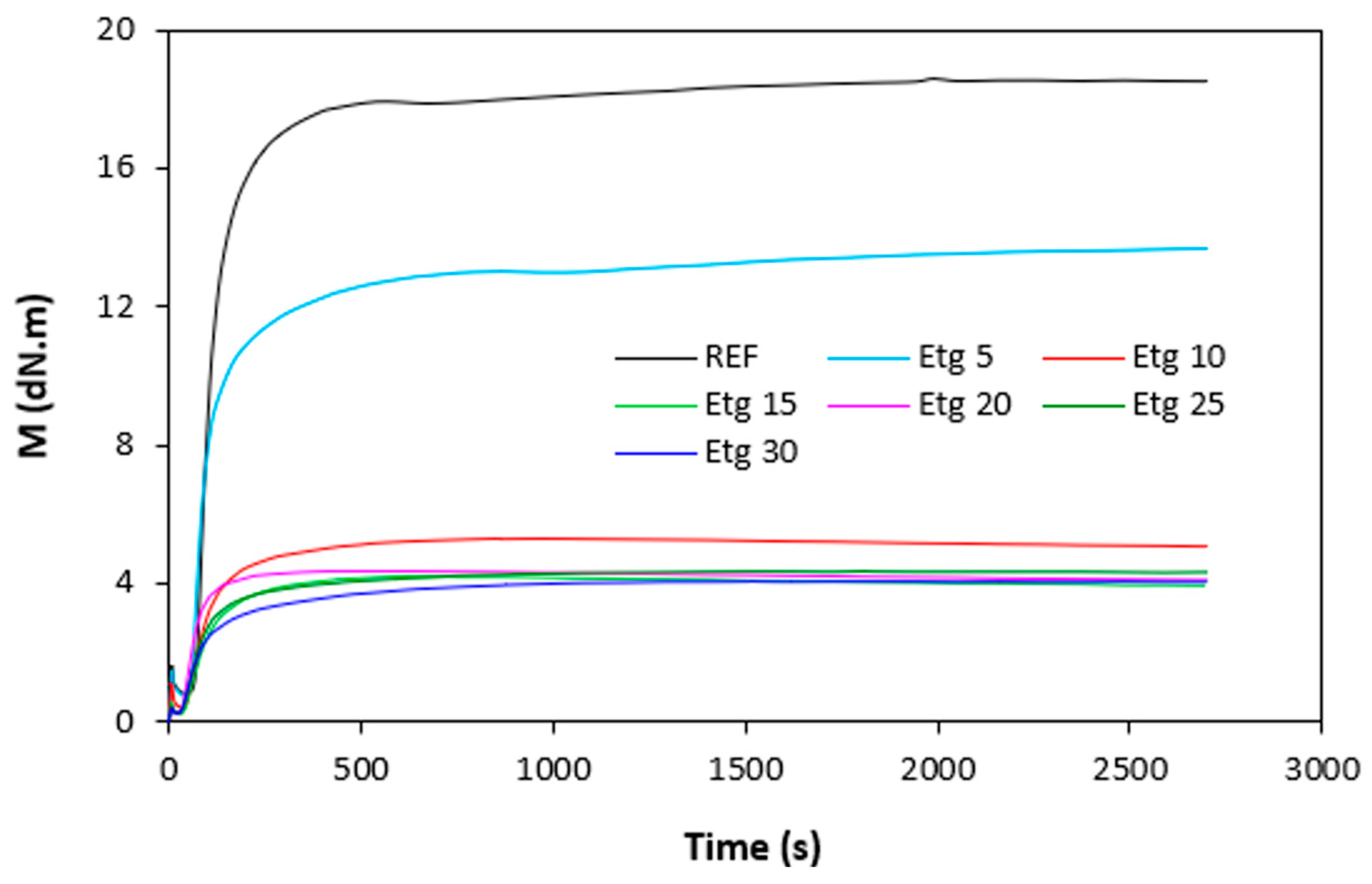

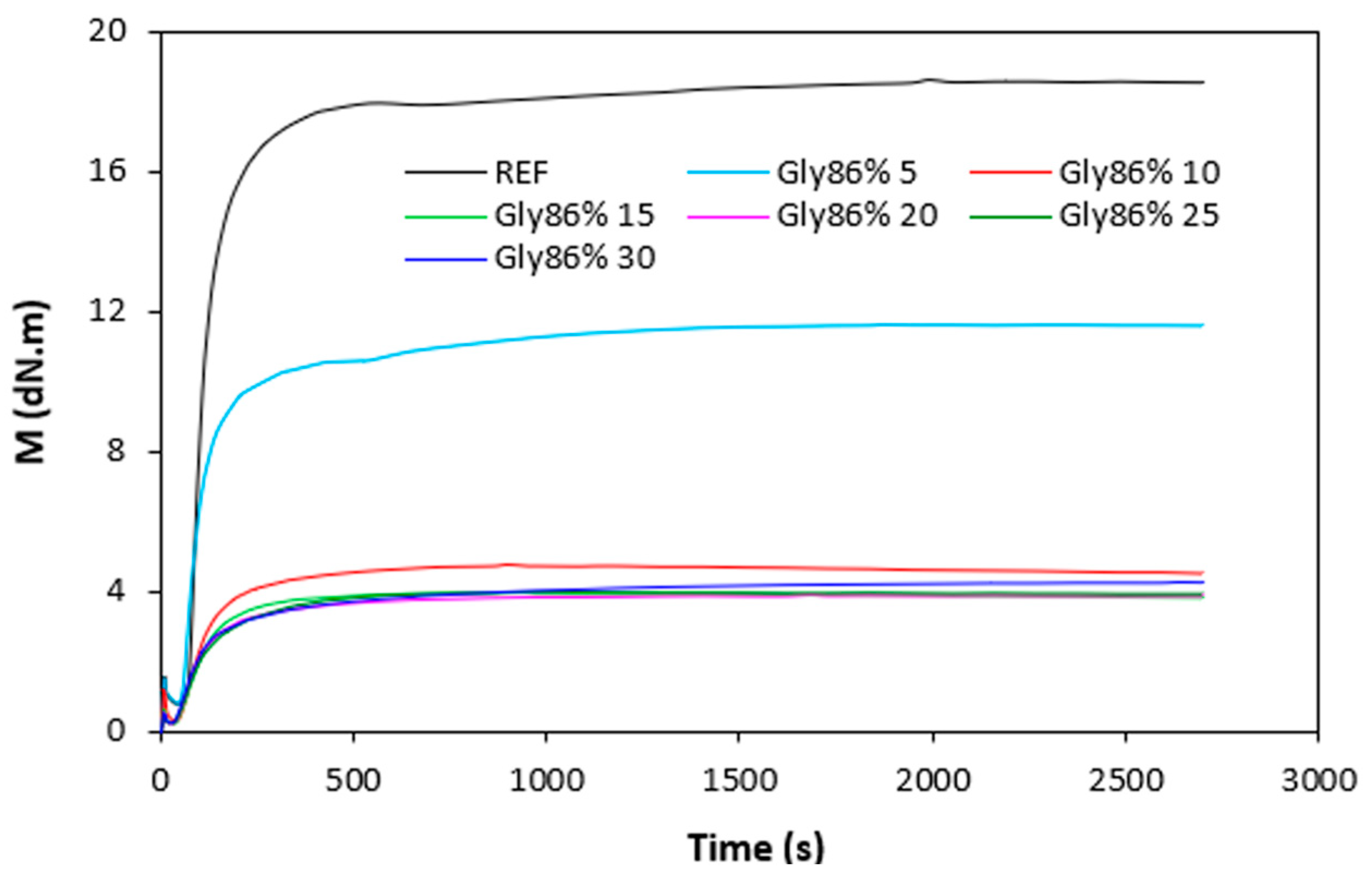

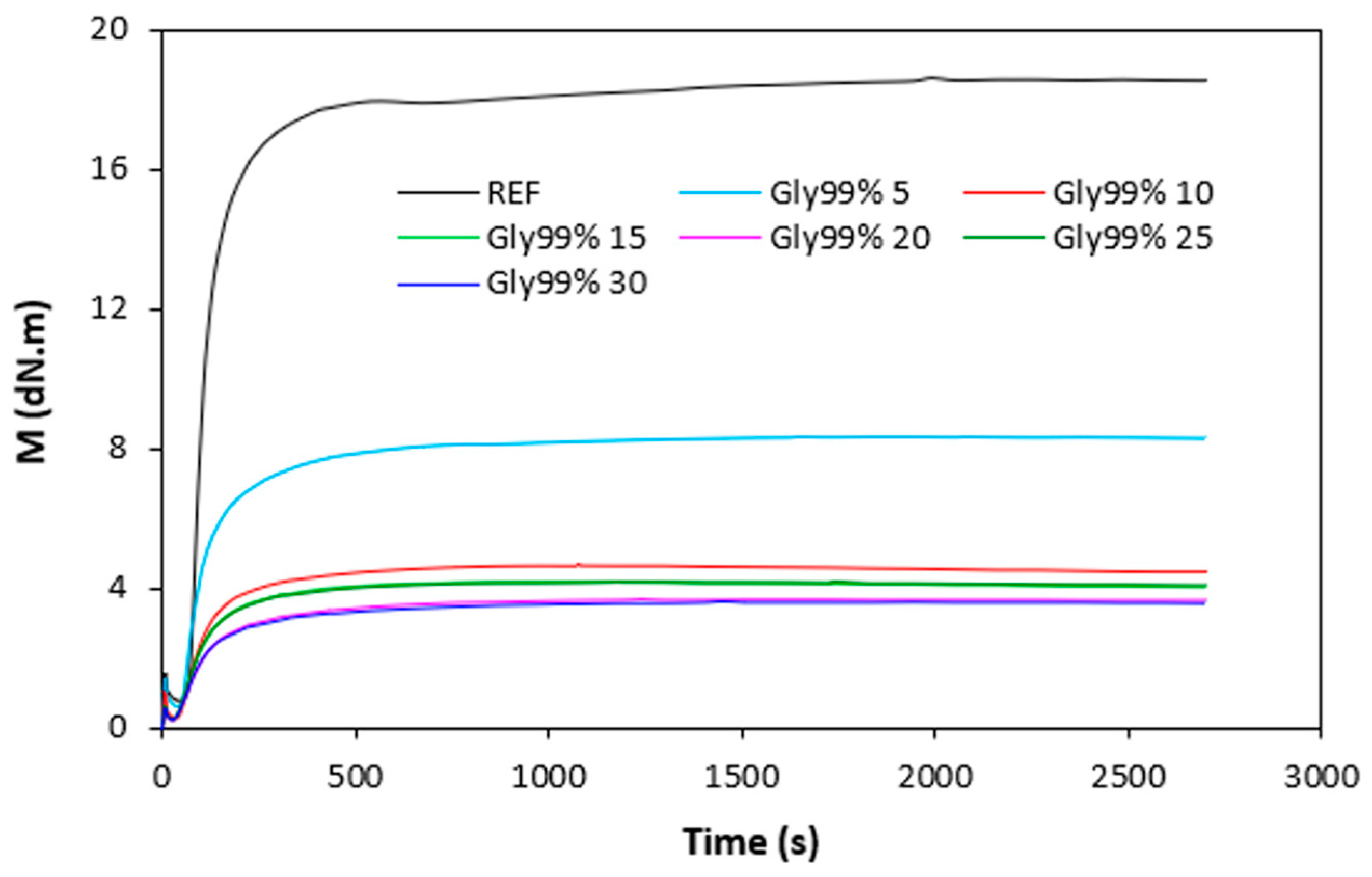

The curing characteristics of rubber compounds were evaluated from the corresponding curing isotherms measured by rheometer MDR 2000 (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). It becomes apparent from them that both, minimum

ML but mainly maximum

MH torque showed significant decreasing trend with increasing amount of plasticizers. The highest

ML and

MH exhibited reference, plasticizer free rubber compound, while the lowest values of both characteristics demonstrated rubber compounds with maximum plasticizers content. The decrease in minimum torque relates to the decrease of the compound viscosity before the curing process started, while the decline in maximum torque refers to the decrease of viscosity and cross-link density of the cured compounds. The decrease in

MH and

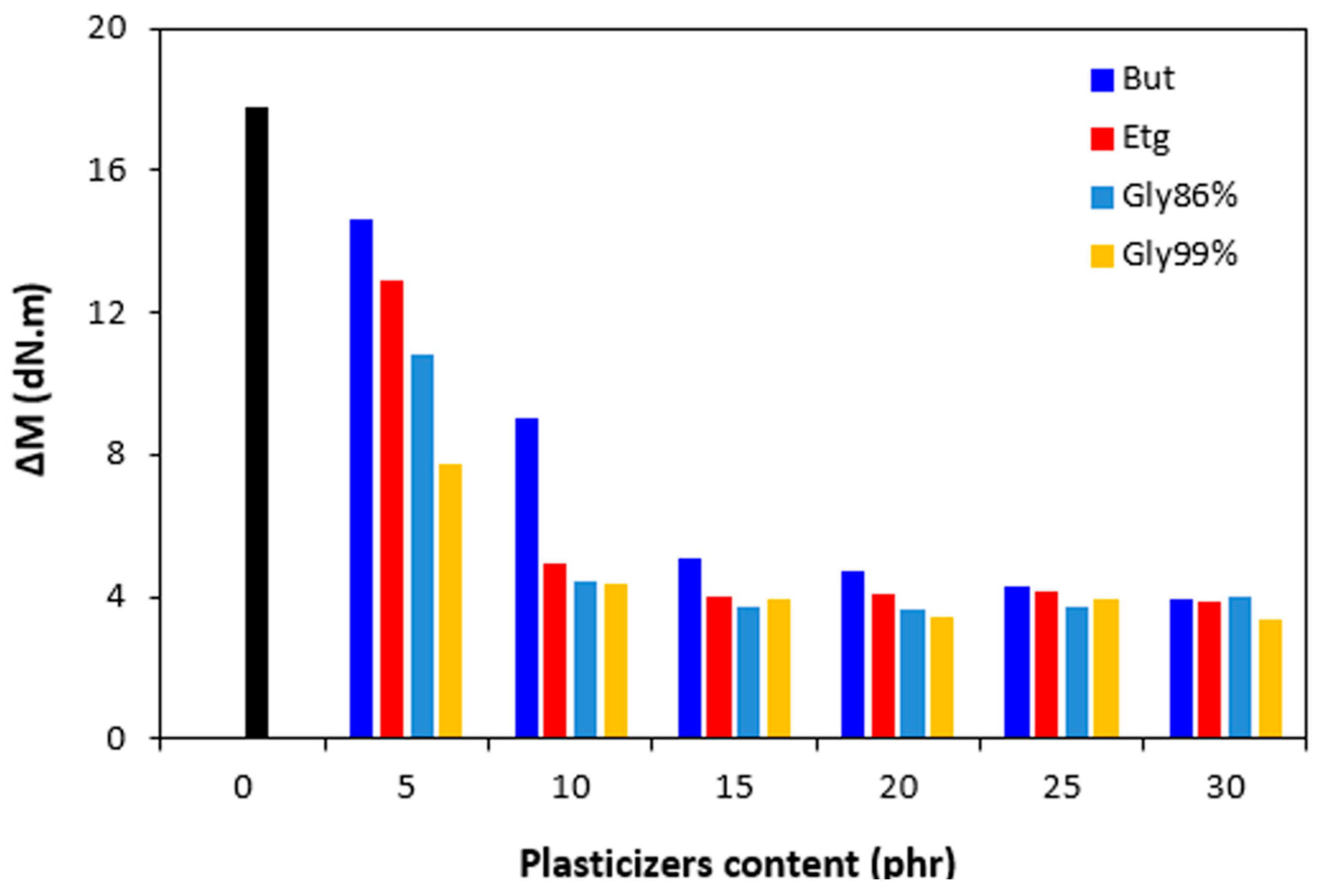

ML was subsequently reflected in the decrease of the torque difference (

∆M =

MH -

ML) as seen in

Figure 5.

MH, ML and

∆M were significantly lowered up to 10 phr of plasticizers, but then there was only a small change with next increase in plasticizers content. There was also recorded very low influence of the type of plasticizer on torques

MH, ML and torque difference

∆M. Though, it seems that the highest

∆M demonstrated vulcanizates with applied 1,4-butanediol, mainly at lower amounts of the plasticizer. The decrease in torque values by application of plasticizers points out to their softening effect on rubber compounds and reduction of the compounds viscosities.

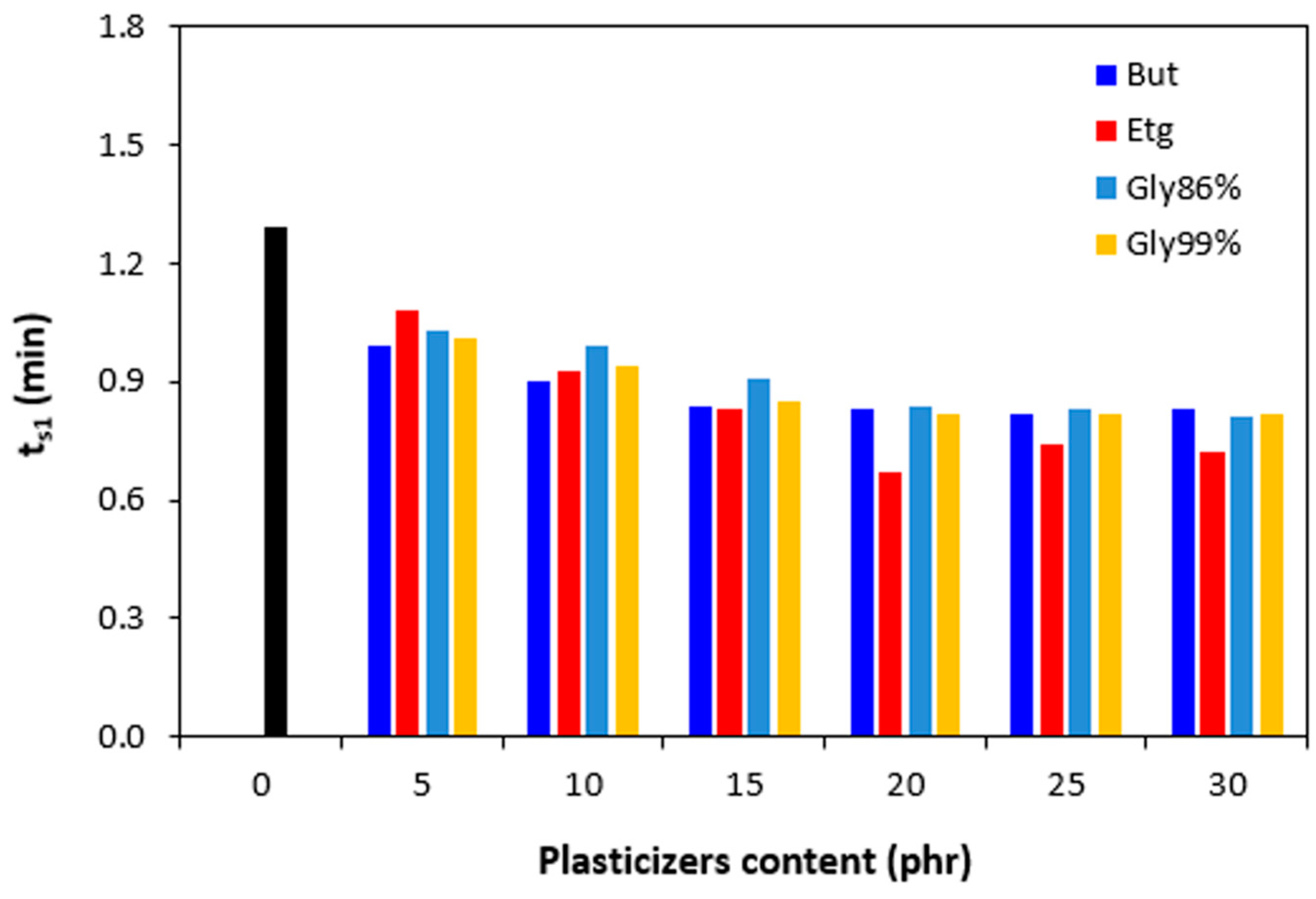

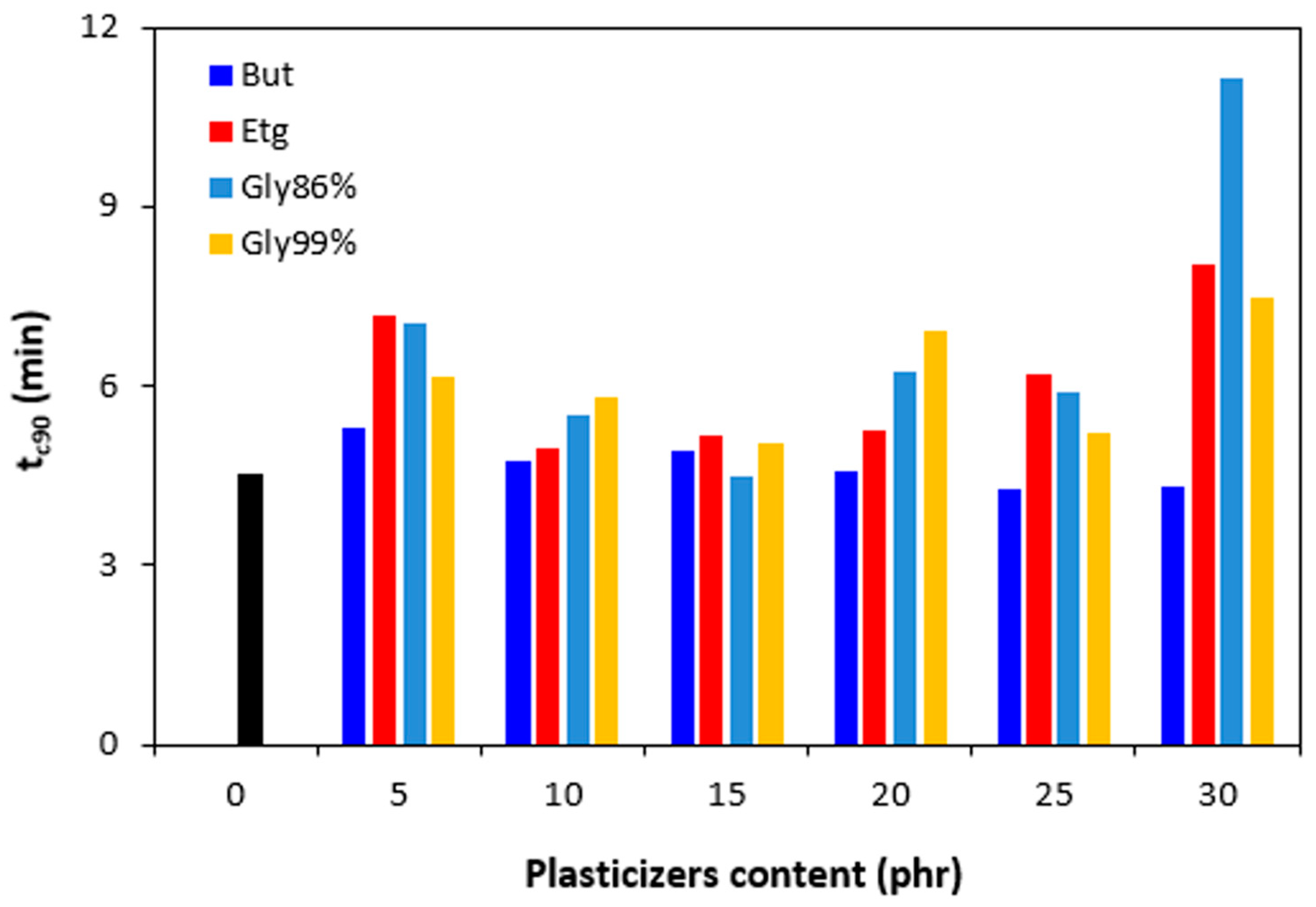

The presence of plasticizers in rubber compounds resulted in a small decrease of scorch time

ts1 (

Figure 6). Seeing that the decrease of scorch time was only few seconds, it can be considered being insignificant. On the other hand, by introduction of 5 phr plasticizers, the optimum cure time

tc90 was prolonged when compared to the reference (

Figure 7). Then, there was observed no clear influence of plasticizers content on optimum cure time. In most cases, the

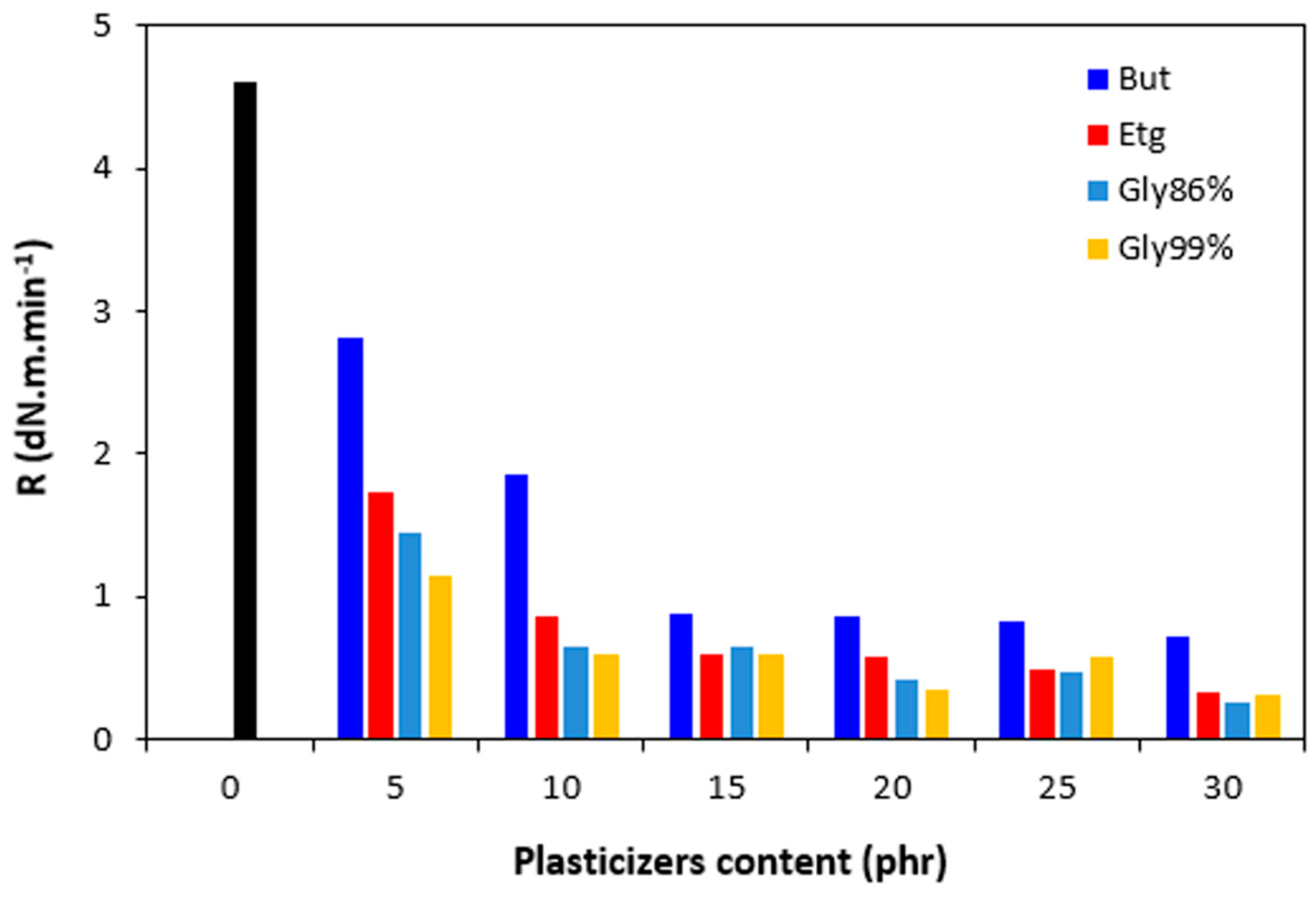

tc90 was significantly prolonged at maximum plasticizers content. The analysis of the curing process kinetics was also observed by evaluation of the cure rate

R. From

Figure 8 it becomes apparent that the highest cure rate demonstrated the reference rubber compound. The higher the amount of plasticizers, the lower the cure rate. When considering the type of the plasticizer, the highest cure rate demonstrated the compounds with 1,4-butanediol. The most significant decrease of cure rate was recorded at low plasticizers content. The higher the amount of plasticizers, the lower the differences in cure rate. A possible explanation for reduction of curing kinetics might be the polarity of plasticizers due to which they can absorb or dilute the additives of curing systems and make them ineffective during the vulcanization process [

29].

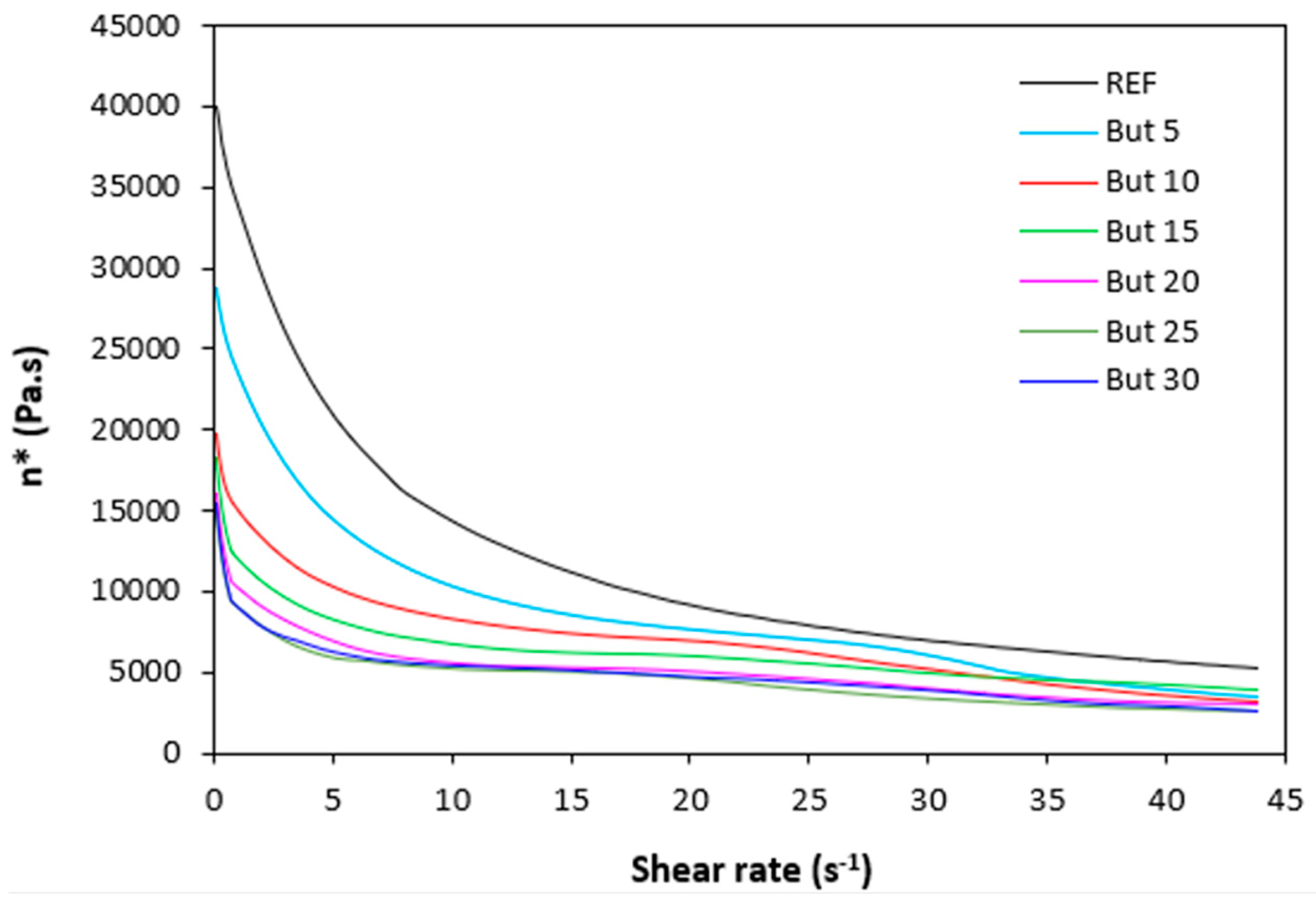

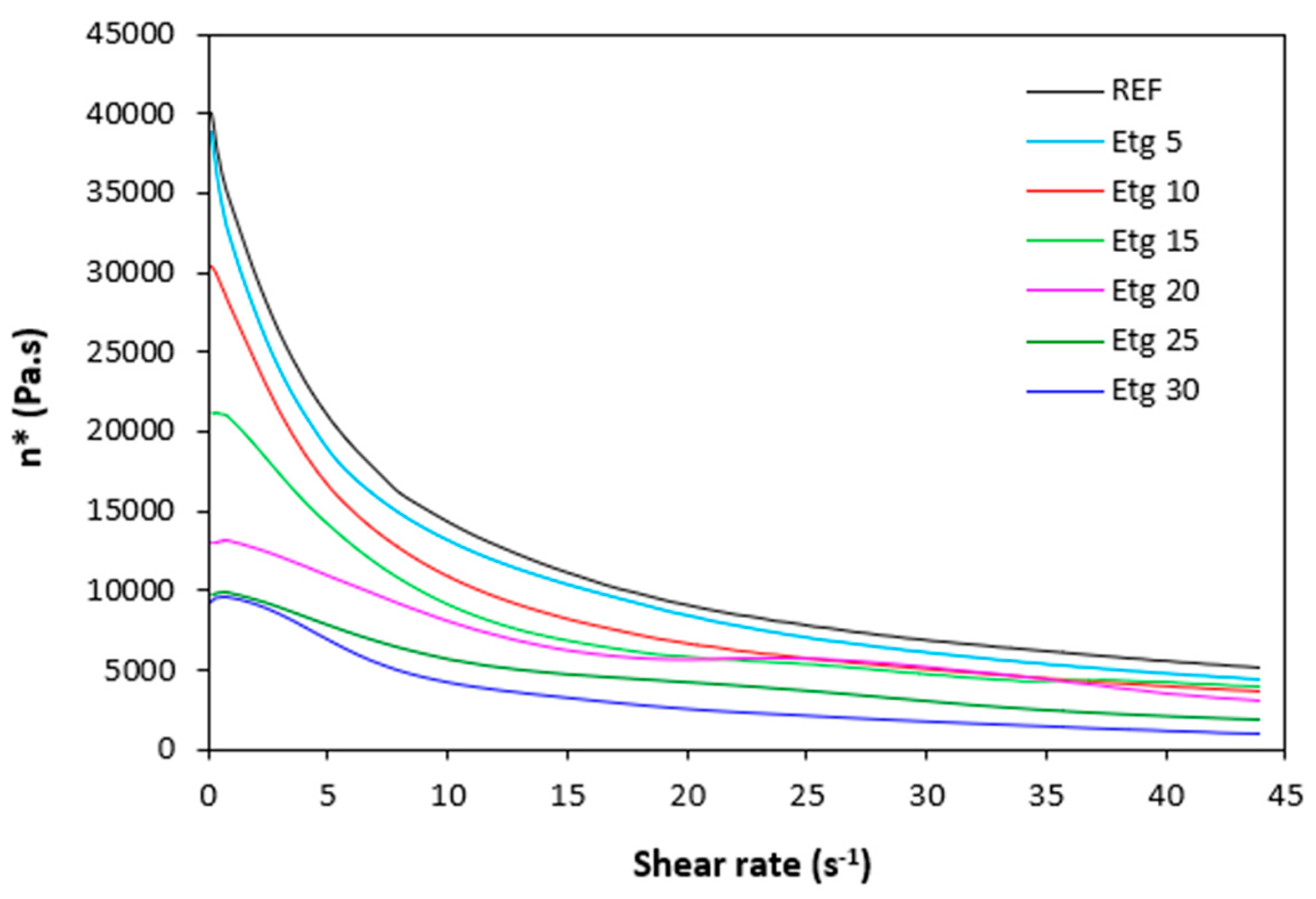

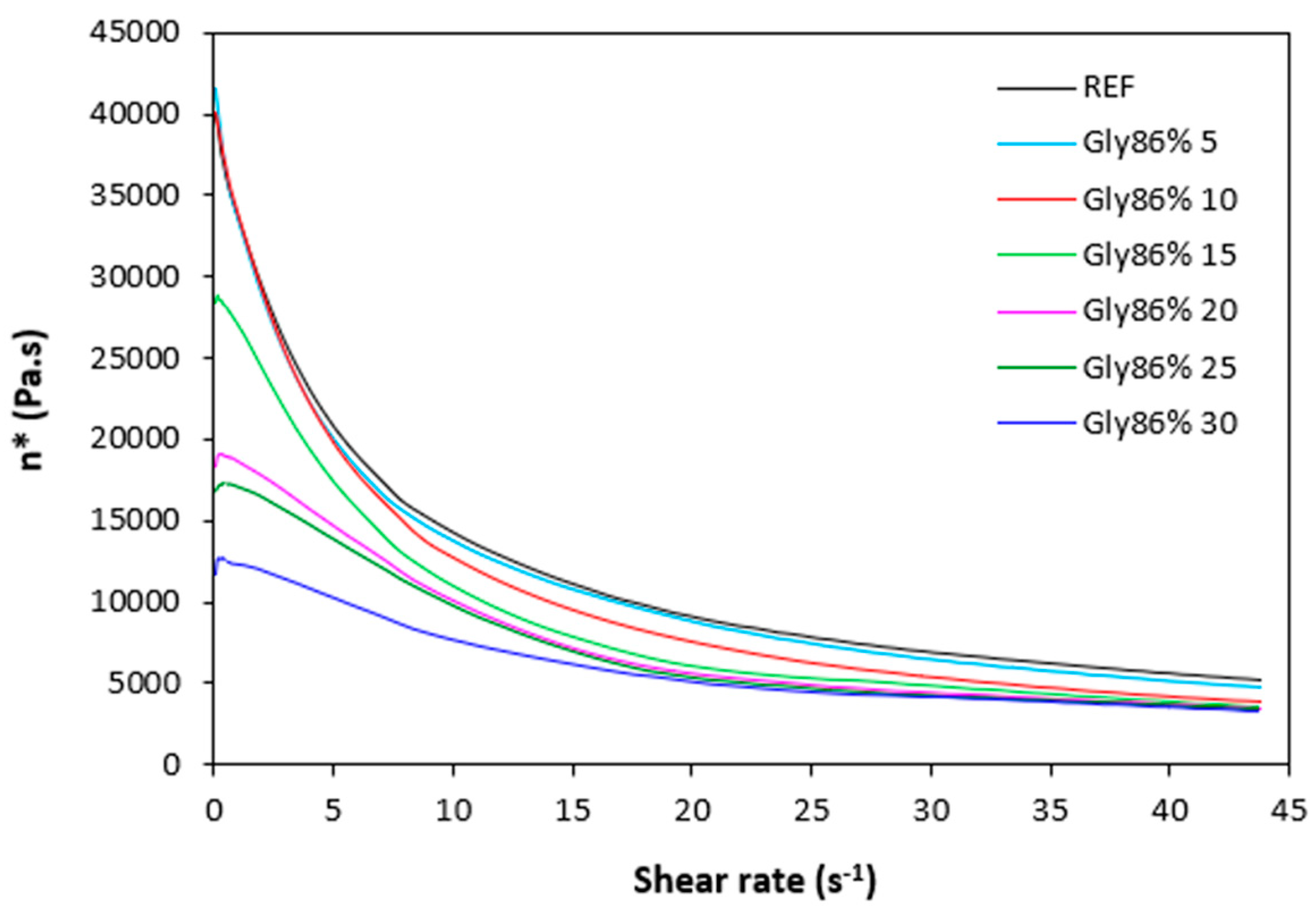

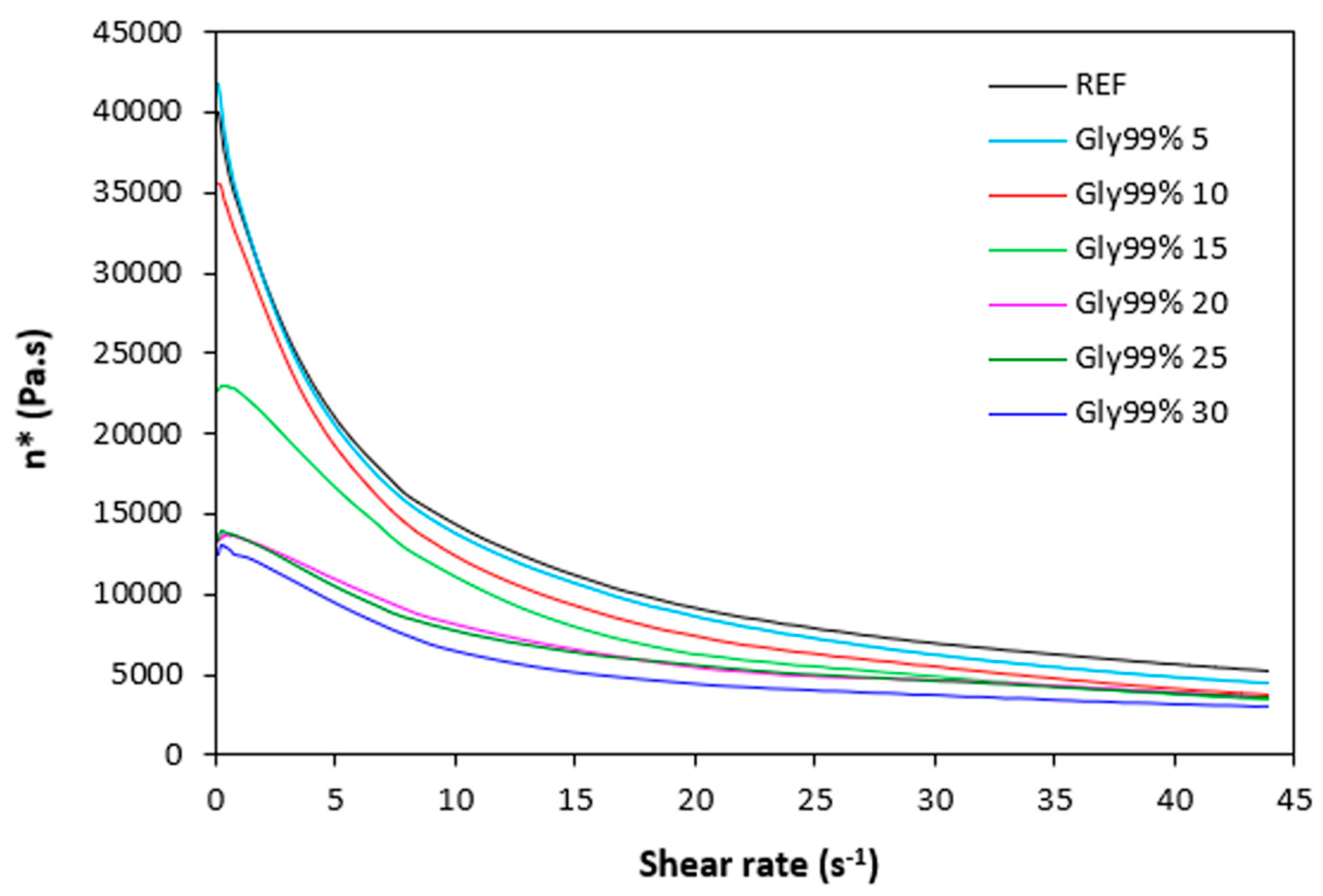

3.2. Rheological Measurement

The dependences of dynamic complex viscosity

η* of rubber compounds on shear rate are depicted in

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. As shown, the highest viscosity in the whole range of shear rate exhibited the reference sample without plasticizer. The application of plasticizers resulted in the decrease of the viscosity. The samples with the highest amount of plasticizers demonstrated the lowest viscosities. The differences in complex viscosities are more prone at lower shear rates. The higher the shear rate, the lower the decrease in viscosities and the lower the differences in viscosities in dependence on plasticizers content. The achieved outputs are in good agreement with experimental data summarized in previous section and clearly demonstrated that the application of plasticizers led to the decrease of the compounds viscosities. Small molecules of plasticizers enter the intermolecular space between the chains and disrupt inter- and intramolecular physical interactions and entanglements. This results in reduction of internal friction and increase of the chain segments mobility. Simultaneously, plasticizers soften calcium lignosulfonate. They enable better dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer within the rubber matrix, which contributes the lowering of the compounds viscosities, too. The effect of each plasticizer on the biopolymer filler with respect to final properties of vulcanizates is more closely discussed in the morphology section.

3.3. Cross-Link Density and Physical-Mechanical Properties

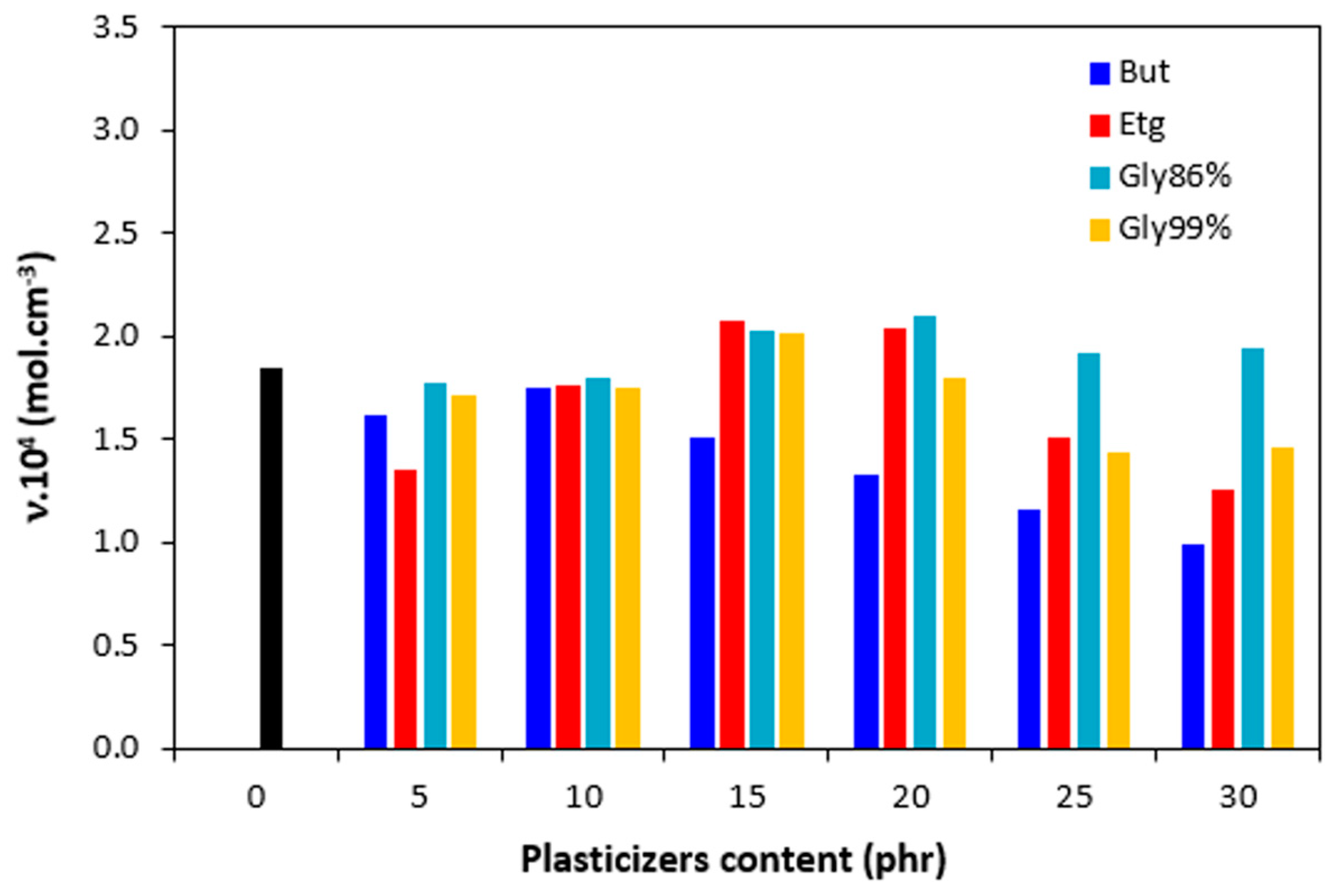

The cross-link density

ν is a very important structural parameter that influences the properties of the vulcanized rubber compounds. The cross-linking degree of vulcanizates in dependence on the type and amount of plasticizer is depicted in

Figure 13. It becomes apparent that the application of 1,4-butanediol resulted in the decrease of the cross-linking degree, which is evident mainly at higher amount of the plasticizer. The influence of other plasticizers on cross-link density was low. It can be stated that the cross-linking degree passed over a slight maximum at 15 and 20 phr of plasticizers and slightly dropped down. The differences in

ν became more evident at higher amount of plasticizers (20 – 30 phr). In that case, the highest cross-link density exhibited the vulcanizates with glycerol 86%.

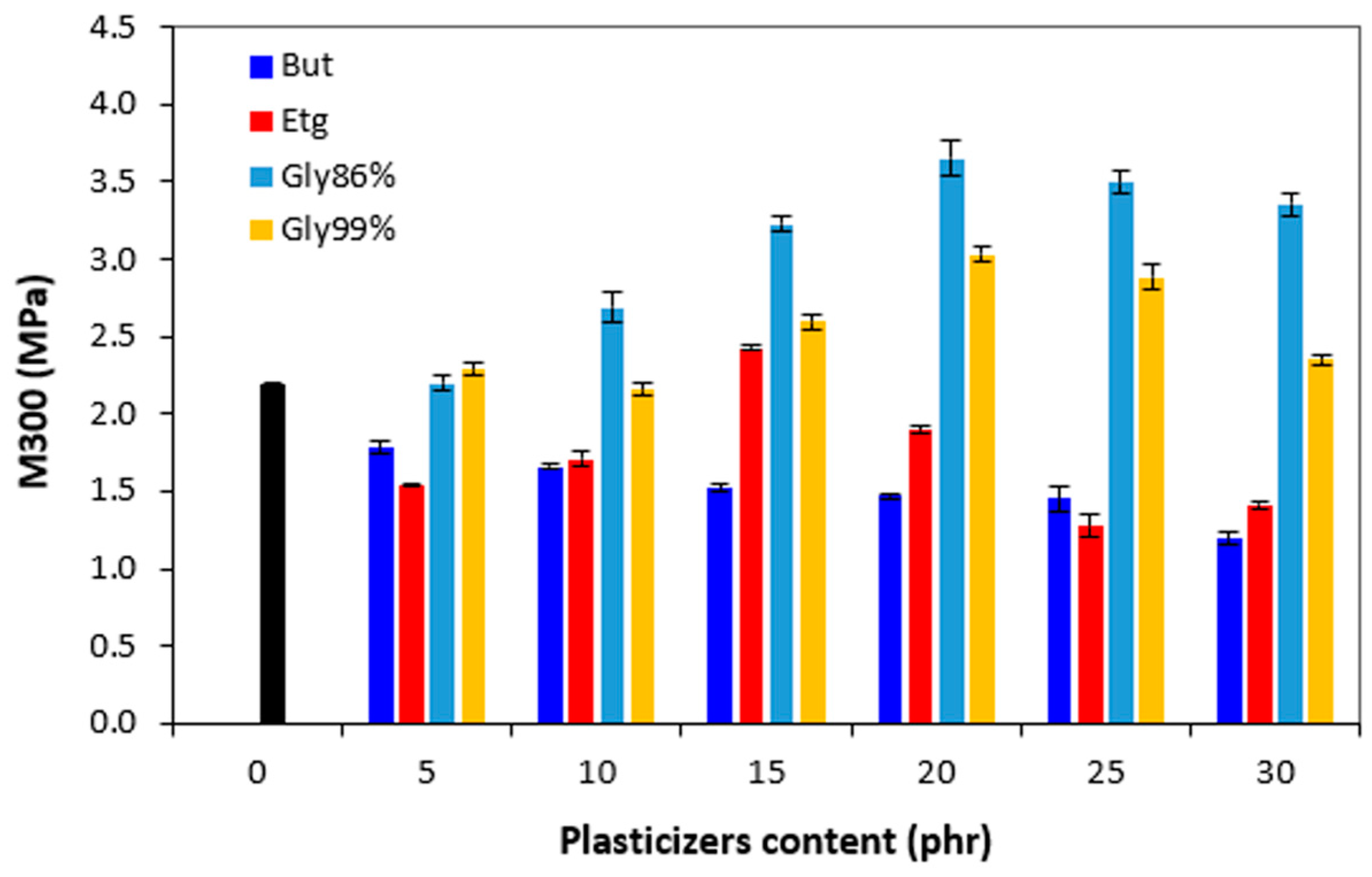

Looking at

Figure 14 one can see a certain correlation between the modulus M300 and cross-link density. As the lowest degree of cross-linking exhibited vulcanizates with applied 1,4-butanediol, these systems were also found to have the lowest modulus. The M300 showed decreasing trend with increasing amount of the plasticizer, again following the trend of the cross-link density. On the other hand, the highest cross-link density of the materials softened with glycerol 86% was reflected in the highest modulus. It becomes interesting that while modulus of vulcanizates with 1,4-butanediol and ethylene glycol decreased when compared to the reference, the opposite tendency was recorded for vulcanizates with both glycerols. The M300 of these vulcanizates passed over a maximum at 15 - 20 phr of plasticizers.

Figure 13.

Influence of plasticizers content on cross-link density υ of vulcanizates.

Figure 13.

Influence of plasticizers content on cross-link density υ of vulcanizates.

Figure 14.

Influence of plasticizers content on modulus M300 of vulcanizates.

Figure 14.

Influence of plasticizers content on modulus M300 of vulcanizates.

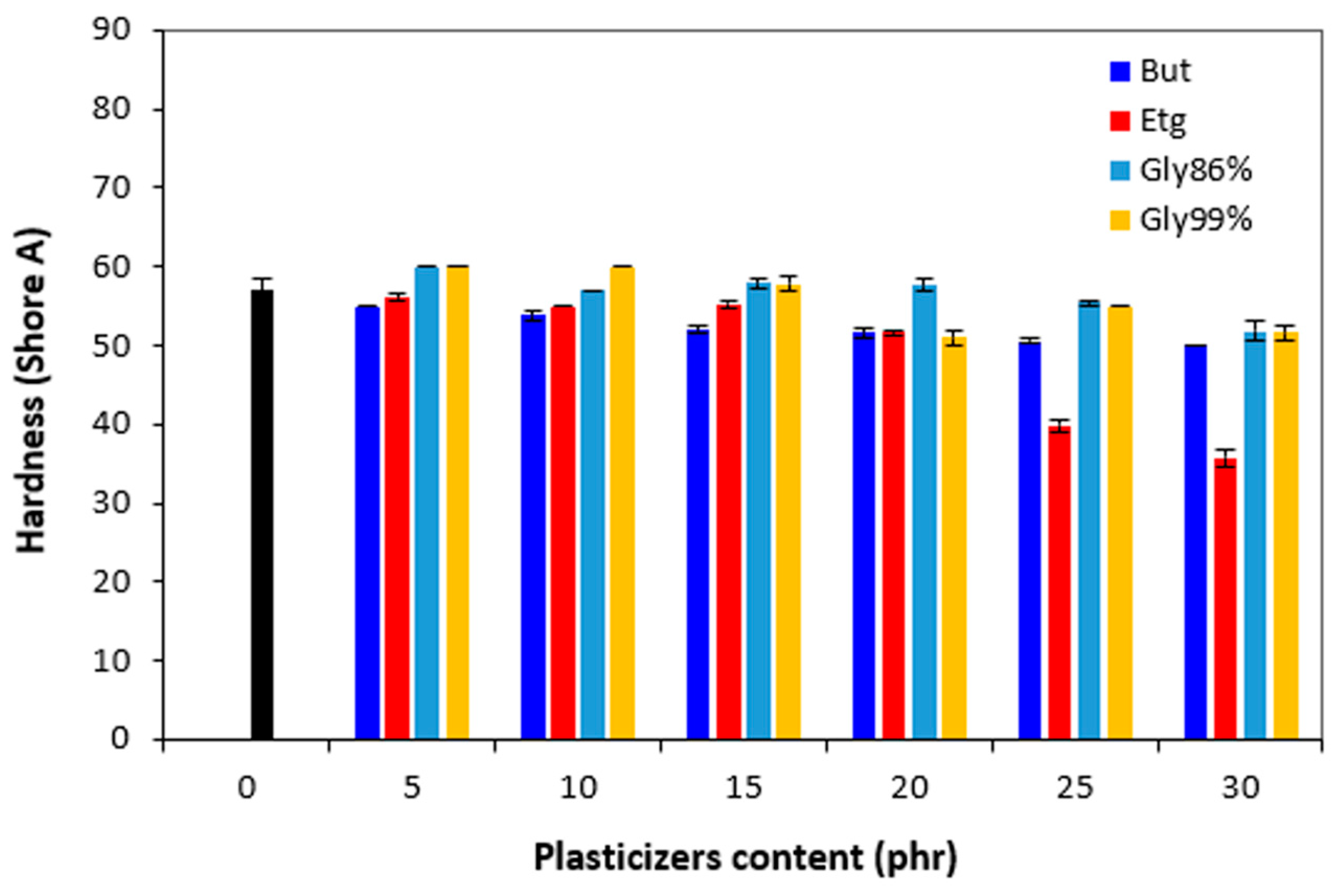

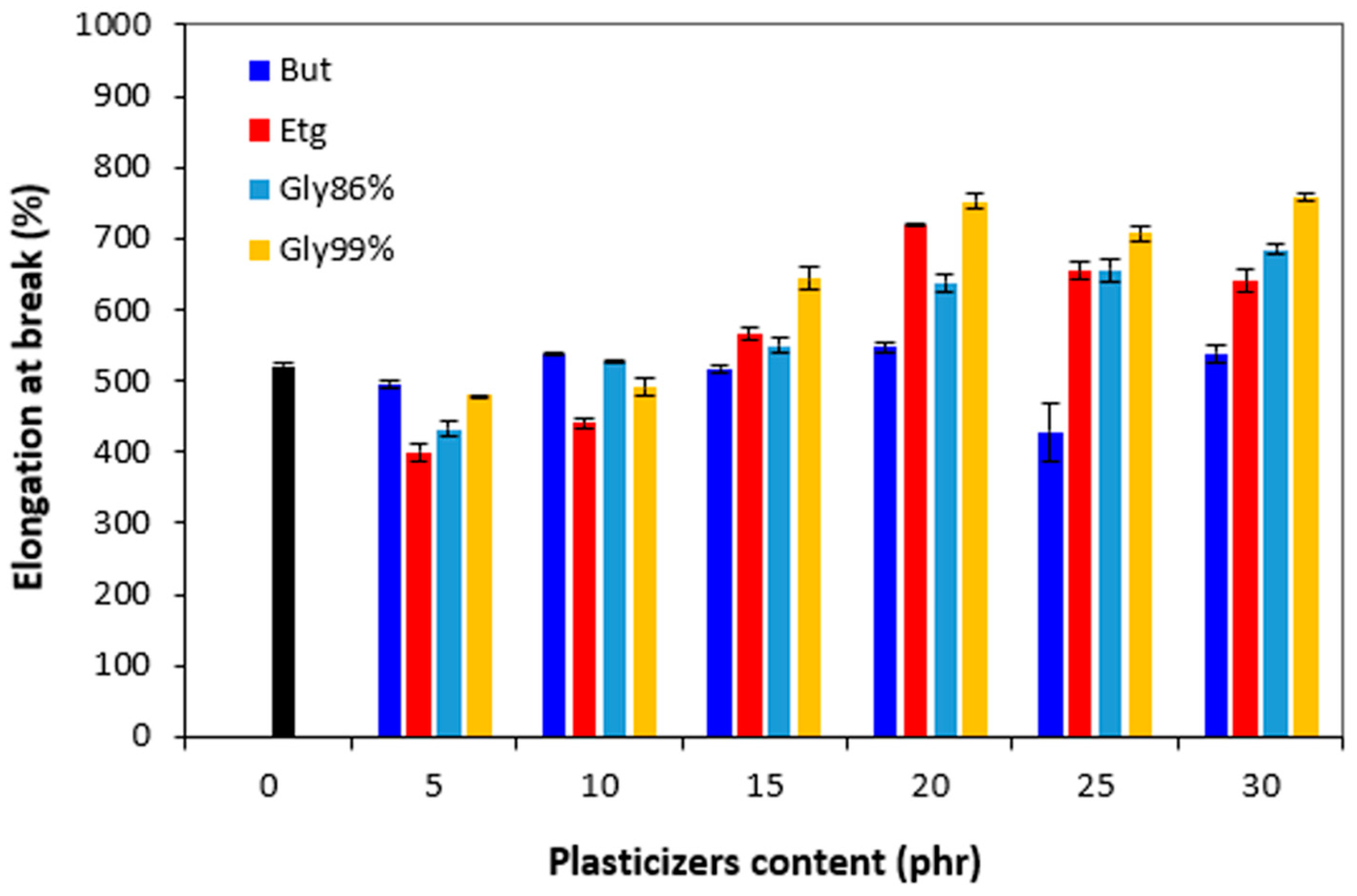

The hardness of vulcanizates did not change very much up to 10 – 15 phr of the plasticizers, then the decline of hardness was recorded at their higher amounts (

Figure 15). Though, the decrease was not very significant. From

Figure 16 it is shown that in comparison with the reference, the elongation at break first slightly decreased by incorporation of 5 phr plasticizers. The elongation at break of vulcanizates with 1,4-butanediol fluctuated only in low range experimental values, almost independently on the amount of the plasticizer and was very similar to that of the reference. The elongation at break of the vulcanizates with applied ethylene glycol and both glycerols showed increasing trend and seemed to reach maximum at 20 phr of plasticizers. The next increase in plasticizers content had no significant influence on the property. The decrease in hardness and the increase in elongation at break can be attributed to the softening effect of plasticizers on rubber compounds, weakening of intramolecular interactions, and thus increasing of rubber chains elasticity and mobility.

Similarly to elongation at break, the tensile strength first decreased by application of 5 phr plasticizers (

Figure 17). Subsequently, the increase of the observed characteristics was recorded (with exclusion of the compounds with 1,4-butanediol). The tensile strength of the compound with maximum content of glycerol 86% was almost threefold higher when compared to the reference (the tensile strength increased from 3.7 MPa for the reference up to over 10 MPa for the vulcanizate with 30 phr of glycerol). By application of glycerol 99%, the maximum tensile strength was reached at 20 phr of the plasticizer (again over 10 MPa). Similarly, the maximum tensile strength for vulcanizates plasticized with ethylene glycol was achieved at 20 phr of the plasticizer. When compared to the reference, the application of ethylene glycol resulted in the increase of tensile strength up to over 6 MPa. By contrast, the negative influence of 1,4-butanediol on tensile characteristics was recorded. As shown in

Figure 17, the higher the amount of 1,4-butanediol, the lower the tensile strength. Based upon the achieved results it can be concluded that the presence of plasticizers in rubber formulations (except for 1,4-butanediol) resulted in the increase of tensile characteristics. Though, the enhancement of tensile strength and elongation at break was observed at higher amounts of plasticizers. It also becomes evident that higher tensile strengths were achieved by application of both glycerols.

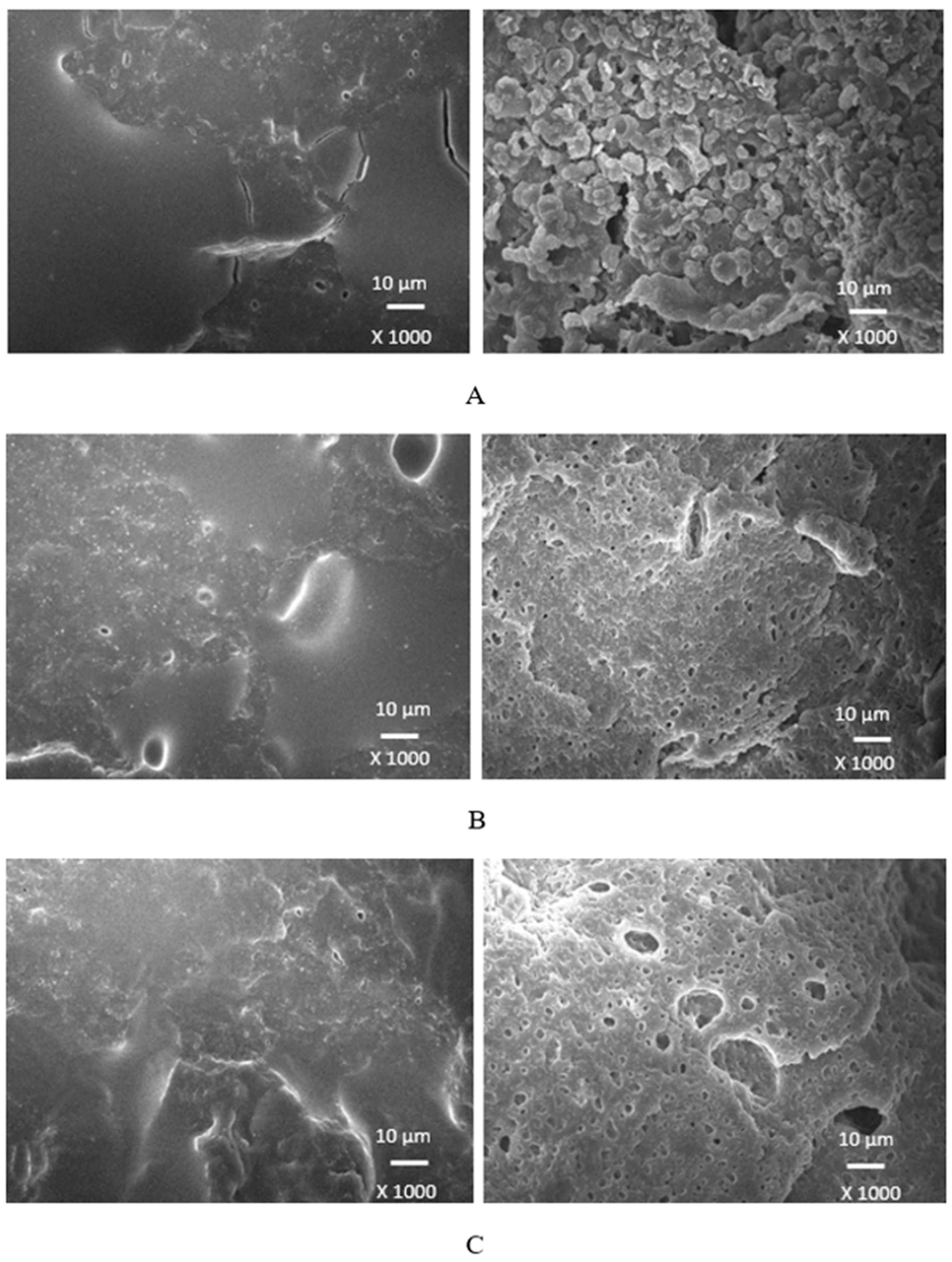

3.4. Morphology

Scanning electron microscopy was employed to analyze the surface structure and morphology of vulcanizates. The samples were first cooled down in liquid nitrogen under the glass transition temperature and then fractured. The uncovered surfaces were subjected to microscopic analysis and SEM images of vulcanizates are presented in

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 on the left side. To better evaluate the dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer within the rubber matrix, SEM analysis was also performed after vulcanizates were washed in boiling water for two hours. As calcium lignosulfonate is water soluble, it was extracted from the surface unveiling the holes and cavities, which were occupied by biopolymer filler before its extraction by hot water. SEM images of the boiling water treated vulcanizates are presented in

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 on the right side. From

Figure 18 it becomes apparent that lignosulfonate tended to form agglomerates in the reference sample. The same statement can also be applied for vulcanizates with lower amounts of plasticizers. The presence of agglomerates suggests that the dispersion of the biopolymer and mutual compatibility between the filler and the rubber on their interfacial region is weak. To that correspond low physical-mechanical properties, mainly weak tensile strength of the reference sample and vulcanizates with lower plasticizers content. The increasing amount of plasticizers resulted in better dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer within the rubber matrix and better adhesion between both components. The structures of the fracture surfaces look smoother and more compact, without any apparent structural defects. The used plasticizers are hydrophilic, low molecular organic molecules that plasticize both the rubber matrix and calcium lignosulfonate. This leads to the decrease of the viscosity of the rubber compounds, as previously confirmed by rheological measurements. The viscosity of the filler and the rubber became closer, which resulted in better dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer. The improvement of compatibility and adhesion on the filler-rubber interface was achieved. The enhancement of dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer within the rubber matrix is clearly observed from SEM images of the vulcanizates washed in boiling water (

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 on the right). It becomes obvious that the sizes of agglomerates were reduced, and lignosulfonate formed smaller and softer domains. The softer domains with lower hardness and rigidity deform much more easily, when compared to stiff filler agglomerates, which act as stress concentrators upon deformation strains. This causes the decrease in mechanical properties of the final rubber materials. On the other hand, small domains with high deformability behave as particles of reinforcing fillers, contributing to the increase in tensile behavior of rubber systems [

30,

31,

32].

When considering the type of plasticizer, it can be deduced that the least homogeneous structure with big filler domains demonstrated vulcanizates with applied 1,4-butanediol

Figure 18. 1,4-butanediol contains two hydroxyl groups situated at the ends of longer hydrocarbon chain, which results in lowest relative polarity from the tested plasticizers. Thus, it can be deduced that it has the lowest influence on the softening of the biopolymer. The achieved outputs confirmed the presumption showing that lignosulfonate formed big agglomerates and weak adhesion on the filler-rubber interface was observed. This caused the decrease in physical-mechanical properties of vulcanizates. Ethylene glycol has also two hydroxyl groups but attached to a shorter hydrocarbon chain. Thus, it exhibits higher relative polarity, and higher plasticizing effect on calcium lignosulfonate. Better dispersion and distribution of the biopolymer was achieved (

Figure 19). SEM analysis as well as the determined values of physical-mechanical properties are following this statement. The most homogeneous and compact structure manifested vulcanizates plasticized with both glycerols (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21). The molecule of glycerol contains three hydroxyl groups, which results in the highest polarity and highest plasticizing effect on the biopolymer. It becomes apparent from SEM images that lignosulfonate formed soft small domains well distributed throughout the rubber matrix. There was also observed very good adhesion and compatibility on filler-rubber interfacial region. The corresponding vulcanizates plasticized with glycerol exhibited the highest tensile characteristics. It can be stated that water present in glycerol has also positive influence on softening of lignosulfonate and contributes to its better dispersion and distribution [

33].

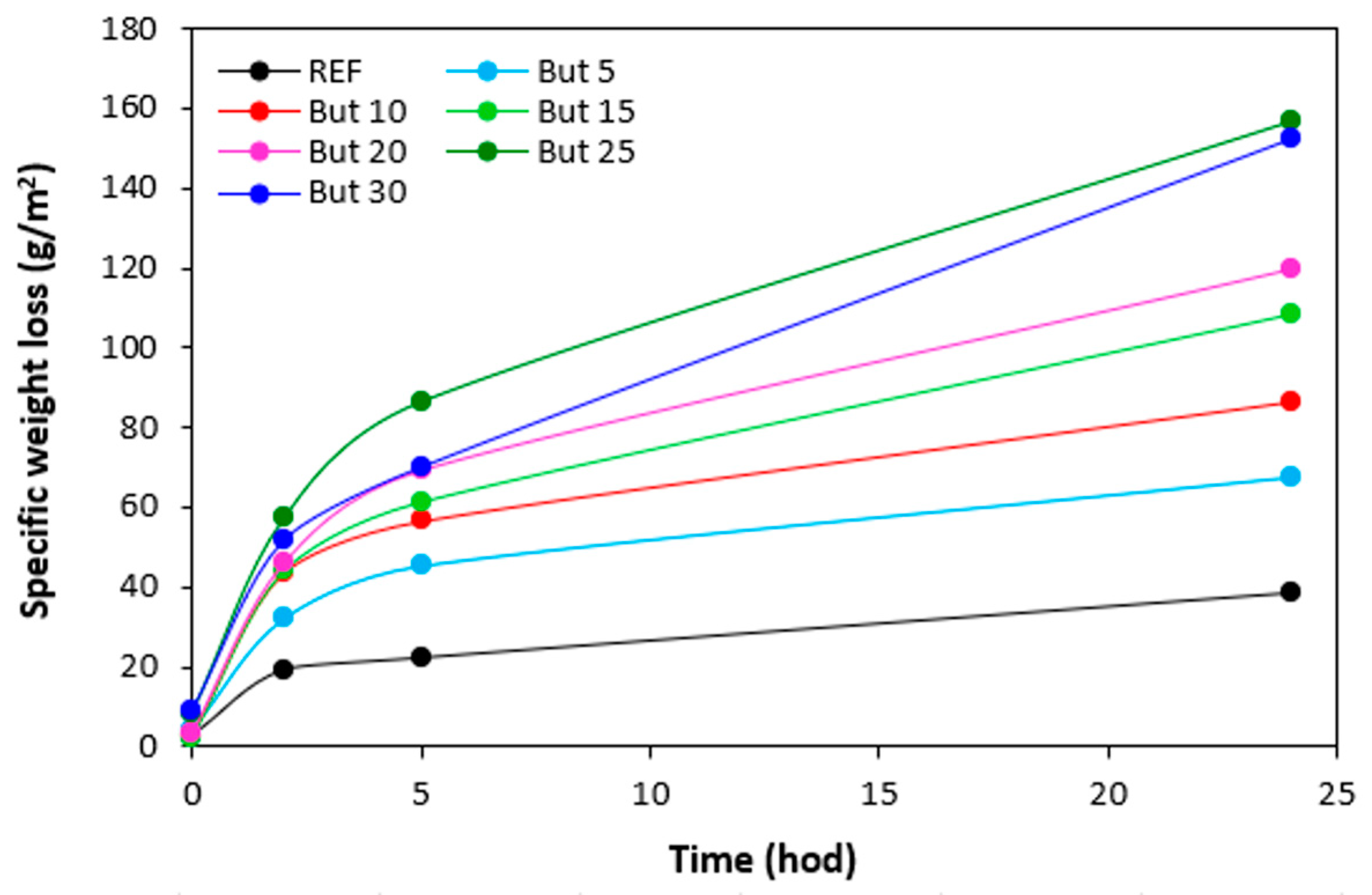

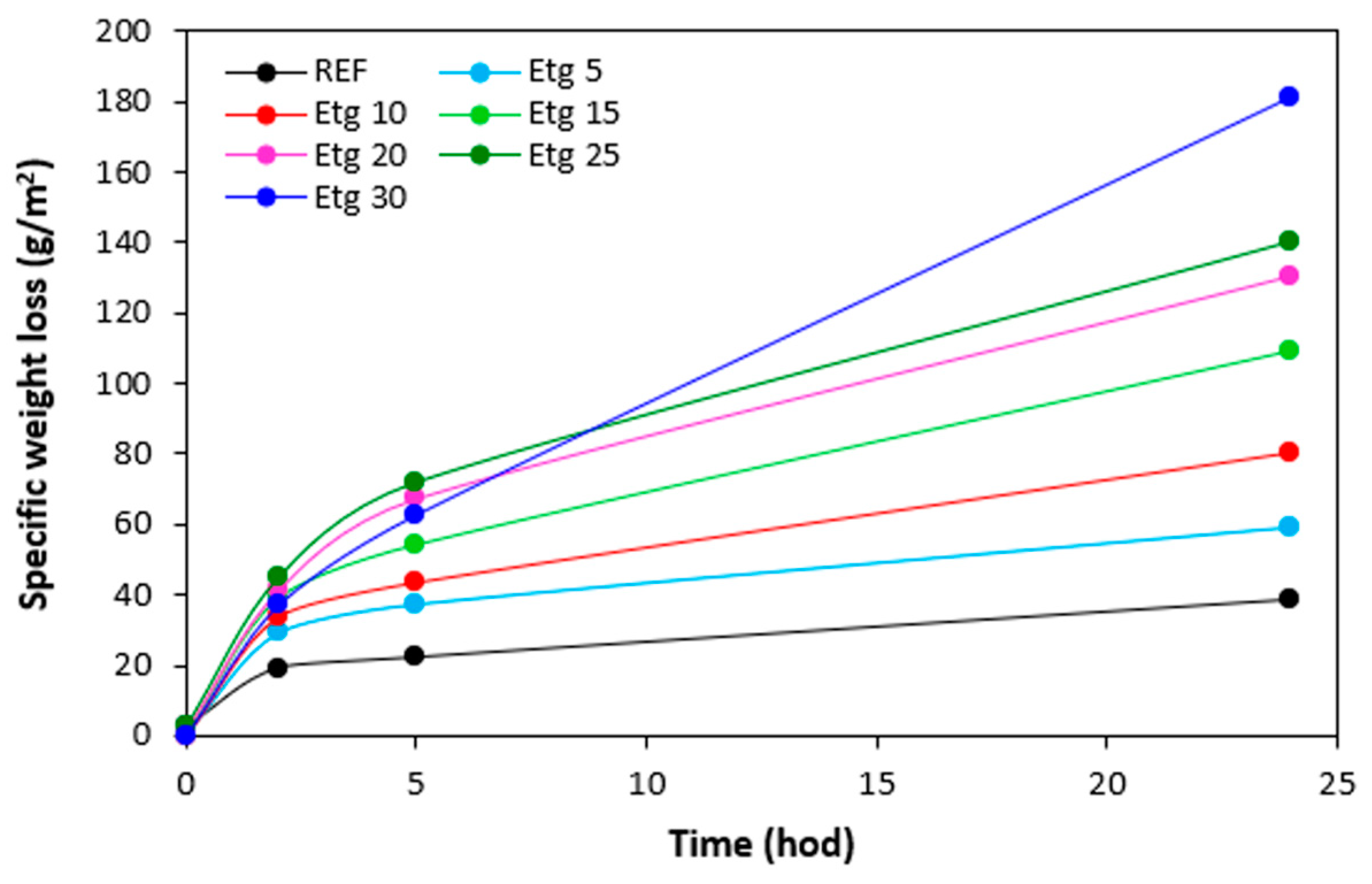

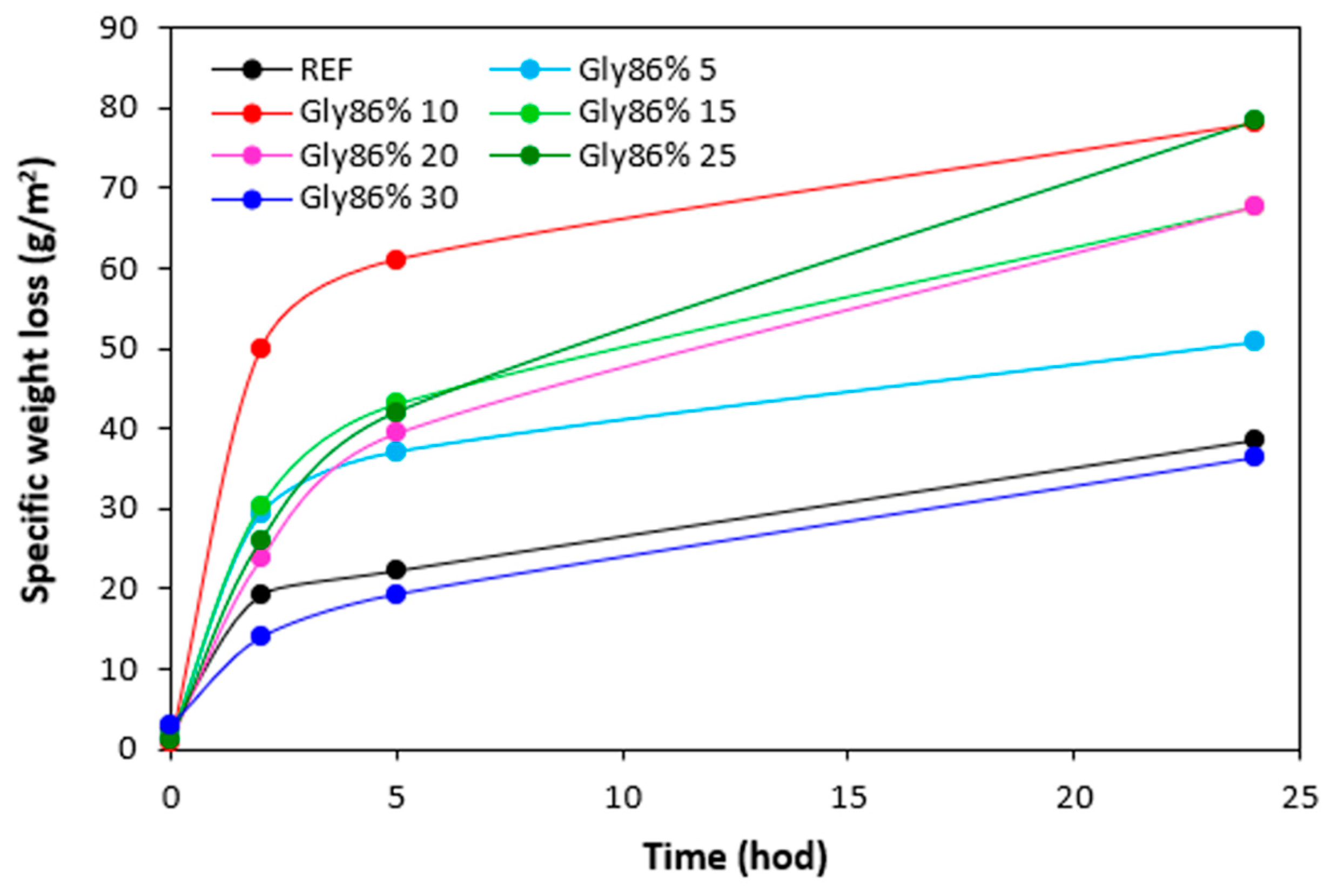

3.5. Blooming of Plasticizers

The formulated rubber compounds are usually multicomponent systems, containing low molecular substances, such as curing systems additives, antidegradants, waxes, plasticizers, and other compounding additives. Some of these substances often migrate to the rubber surface and form a very thin layer on the vulcanizates. This phenomenon is called blooming. With respect to the requirements to the properties of the final products, blooming can be desired, but also negative effect. For example, wax blooming is used to protect rubber articles against ozone attack by formation of thin coherent layer acting as a physical barrier [

34]. Blooming can also be undesired, for example, the migration of ingredients sometimes causes surface tackiness, reduces aesthetic appearance, or gives rise to poor rubber to rubber or rubber to metal adhesion [

35]. Also, health and environmental aspects must be considered when blooming of some additives.

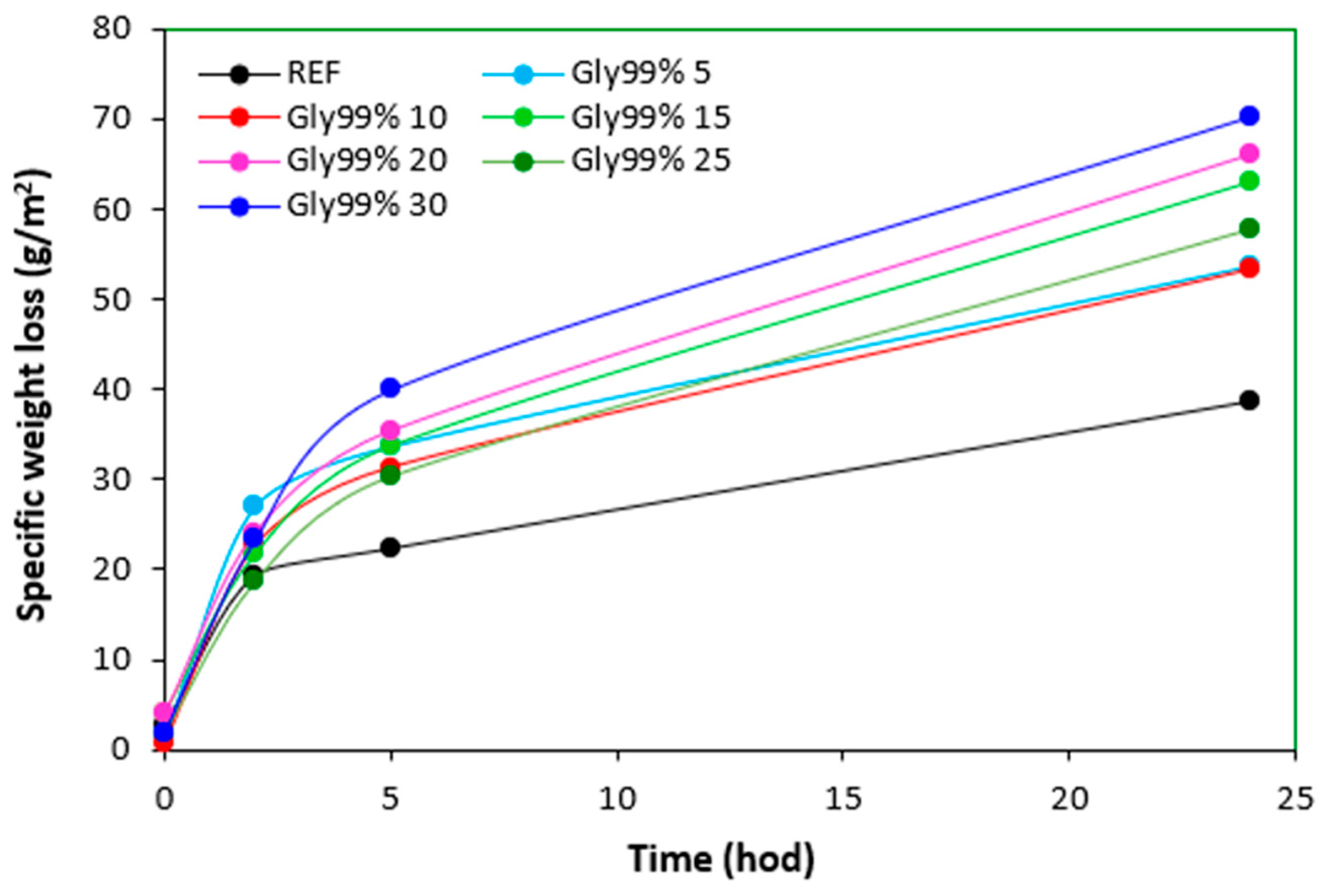

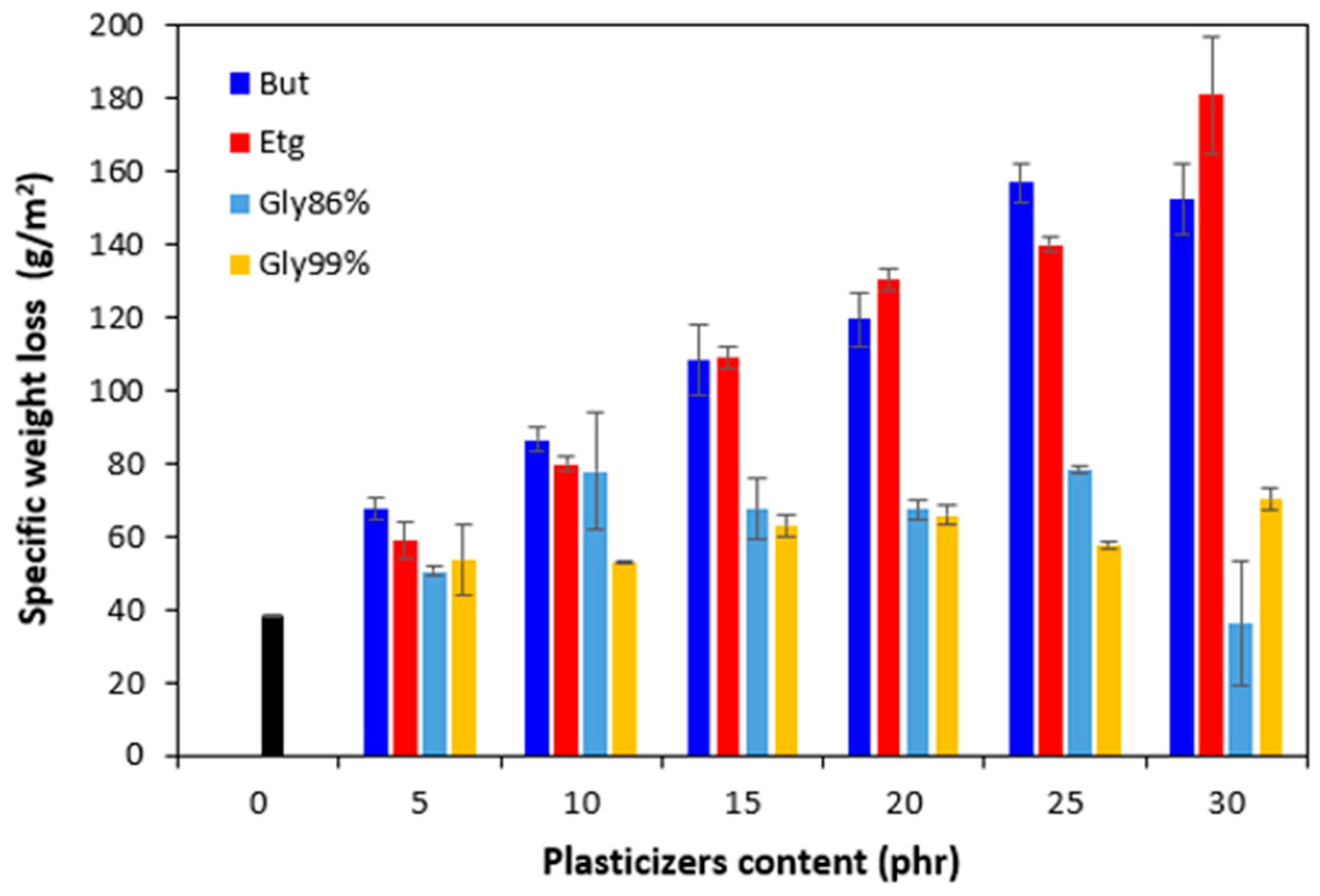

The specific weight loss of the samples with all tested plasticizers after being exposed to 70 °C in dependence on time are graphically illustrated in

Figure 22,

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25, while the specific weight loss in dependence on the type and amount of plasticizers after 24 hours is presented in

Figure 26. It becomes apparent from

Figure 26 that the lowest specific weight loss exhibited the reference sample without plasticizer. At an initial stage, the weight loss of the reference sample might be attributed to the loss the biopolymer, which was not well bound to the surface and was wiped out with ethanol. Then, as seen in

Figure 22, there was no other significant change in specific weight loss of the reference in dependence on time. Though, some increase can still be caused by wiping out of calcium lignosulfonate from surface layer. The higher the amount of 1,4-butanediol and ethylene glycol in rubber formulations, the higher the specific weight loss, whereas the type of the plasticizer played no crucial role. The specific weight loss of the samples with lower amounts of both glycerols was also higher when compared to the reference and was very similar to that recorded for vulcanizates with lower amounts of 1,4-butanediol and ethylene glycol. But then, there was no other significant change in specific weight loss with the next increase of glycerols content. The specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with higher amount of glycerols was comparable to the samples with lower glycerol amounts and much lower when compared to equivalent vulcanizates with 1,4-butanediol and ethylene glycol.

The reason for different specific weight loss of vulcanizates can be again attributed to the structure of plasticizers. 1,4-butanediol and ethylene glycol are less polar due to lower amount of hydroxyl groups. On the other hand, glycerol exhibits higher polarity and thus higher affinity with the biopolymer. Higher amount of hydroxyl groups increases the efficiency of hydrogen bonds formation between glycerol and calcium lignosulfonate. Glycerol is more physically adsorbed on the biopolymer, and thus it shows lower blooming effect.

4. Conclusion

Calcium lignosulfonate filled rubber compounds were plasticized with polar low molecular weight organic substances. The results revealed that the application of plasticizers resulted in the decrease of the curing kinetics and reduction of minimum and maximum torque as well as torque difference. This pointed out to the softening effect of plasticizers on rubber compounds and reduction of the compounds viscosities, which was clearly confirmed from rheological measurements. The reduction of internal friction between the chain segments and increase in the chains elasticity and mobility led to the decrease of hardness and increase of elongation at break. Simultaneously, plasticizers exhibited softening effect on lignosulfonate. It can be stated that the higher the polarity of the plasticizer, the higher the softening effect. SEM analysis revealed that the lowest plasticizing effect on calcium lignosulfonate exhibited 1,4-butanediol, because of its lowest polarity. On the other hand, the most homogeneous structure demonstrated vulcanizates with applied glycerols having the highest polarity. This suggests that glycerol shows the highest plasticizing effect on lignosulfonate. Soften lignofulfonate formed small, soft filler like domains well distributed within the rubber matrix. Good compatibility on the filler-rubber interface was observed. The outlined facts are responsible for enhancement in the tensile characteristics of the corresponding vulcanizates. A remarkable three-fold increase in tensile strength was recorded for vulcanizates plasticized with higher amount of glycerols when compared to the reference. The highest polarity and highest amount of hydroxyl groups in glycerol structure enabled the highest physical adhesion with the biopolymer. As a result, glycerol showed the lowest blooming effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ján Kruželák; Methodology, Ján Hronkovič and Ivan Hudec; Software, Jozef Preťo; Validation, Ján Hronkovič; Investigation, Michaela Džuganová and Andrea Kvasničáková; Resources, Andrea Kvasničáková; Data curation, Jozef Preťo; Writing – review & editing, Ján Kruželák.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-19-0091 and APVV-22-0011.

References

- Shorey R, Salaghi A, Fatehi P, Mekonnen TH.: Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: a review. RSC Sustainability. 2024;2:804. [CrossRef]

- Jantachum P, Phinyocheep P.: Compatibilization of cellulose nanocrystal-reinforced natural rubber nanocomposite by modified natural rubber. Polymers. 2024;16:363. [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Baranowska A, Maciejewska M, Duda P.: The potential application of starch and walnut shells as biofillers for natural rubber (NR) composites. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7968. [CrossRef]

- Carpenedo GA, Guerra NB, Giovanela M, De Paoli MA, da Silva Crespo J.: Evaluation of lignin as stabilizer in vulcanized natural rubber formulations. Polímeros. 2022;32(3): e2022036. [CrossRef]

- Fazeli M, Mukherjee S, Baniasadi H, Abidnejad R, Mujtaba M, Lipponen J, Seppälä J, Rojas OJ.: Lignin beyond the status quo: recent and emerging composite applications. Green Chem. 2024;26:593. [CrossRef]

- Antonino LD, Gouveia JR, de Sousa Júnior RR, GES Garcia, Gobbo LC, Tavares LB, dos Santos DJ.: Reactivity of aliphatic and phenolic hydroxyl groups in kraft lignin towards 4,4' MDI. Molecules. 2021;26:2131.

- Intapun J, Rungruang T, Suchat S, Cherdchim B, Hiziroglu S.: The characteristics of natural rubber composites with Klason lignin as a green reinforcing filler: Thermal Stability, mechanical and dynamical properties. Polymers. 2021;13:1109.

- Lu X, Gu X, Shi Y.: A review on lignin antioxidants: Their sources, isolations, antioxidant activities and various applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;210:716-741.

- Vasile C, Baican M.: Lignins as promising renewable biopolymers and bioactive compounds for high-performance materials. Polymers. 2023;15:3177. [CrossRef]

- Sugiarto S, Leow Y, Li Tan C, Wang G, Kai D.: How far is Lignin from being a biomedical material? Bioact Mater. 2022;8:71-94.

- Libretti C, Correa LS, Meier MAR.: From waste to resource: advancements in sustainable lignin modification. Green Chem. 2024;26:4358. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Meng Y, Cheng Z, Li B.: Research progress and prospect of stimuli-responsive lignin functional materials. Polymers. 2023;15:3372. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Li J, Lu T, Han X, Yan Z, Zhao S, Wang H.: Comparative study on the synergistic reinforcement of lignin between carbon black/lignin and silica/lignin hybrid filled natural rubber composites. Ind Crop Prod. 2022;187:115378. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Aini NA, Othman N, Hazwan Hussin M, Sahakaro K, Hayeemasae N.: Efficiency of interaction between hybrid fillers carbon black/lignin with various rubber-based compatibilizer, epoxidized natural rubber, and liquid butadiene rubber in NR/BR composites: Mechanical, flexibility and dynamical properties. Ind Crop Prod. 2022;185:115167.

- Mardiyati Y, Fauza AN, Rachman OA, Steven S, Santosa SP.: A silica–lignin hybrid filler in a natural rubber foam composite as a green oil spill absorbent. Polymers. 2022;14:2930. [CrossRef]

- Bahl K, Miyoshi T, C Jana S.: Hybrid fillers of lignin and carbon black for lowering of viscoelastic loss in rubber compounds. Polymer. 2014;55:3825-38235. [CrossRef]

- Yu P, He H, Jia Y, Tian S, Chen J, Jia D, Luo Y.: A comprehensive study on lignin as a green alternative of silica in natural rubber composites. Polym Test. 2016;54:176-185. [CrossRef]

- Ferruti F, Carnevale M, Giannini L, Guerra S, Tadiello L, Orlandi M, Zoia L.: Mechanochemical methacrylation of lignin for biobased reinforcing filler in rubber compounds. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024;12:14028-14037. [CrossRef]

- Shorey R, Salaghi A, Fatehi P, Mekonnen TH.: Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: a review. RSC Sustainability. 2024;2:804. [CrossRef]

- Hait S, Kumar L, Ijaradar J, Ghosh AK, De D, Chanda J, Ghosh P, Gupta SD, Mukhopadhyay R, Wießner S, Heinrich G, Das A.: Unlocking the potential of lignin: Towards a sustainable solution for tire rubber compound reinforcement. J Clean Prod. 2024;470:143274. [CrossRef]

- Sekar P, Noordermeer JWM, Anyszka R, Gojzewski H, Podschun J, Blume A.: Hydrothermally treated lignin as a sustainable biobased filler for rubber compounds. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2023;5:2501-2512. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Aini NA, Othman N, Hazwan Hussin M, Sahakaro K, Hayeemasae N.: Hydroxymethylation-modified lignin and its effectiveness as a filler in rubber composites. Processes. 2019;7:315. [CrossRef]

- Komisarz K, Majka TM, Pielichowski K.: Chemical and physical modification of lignin for green polymeric composite materials. Materials. 2023;16:16. [CrossRef]

- Hait S, De D, Ghosh P, Chanda J, Mukhopadhyay R, Dasgupta S, Sallat A, Al Aiti M, Stöckelhuber KW, Wießner S, Heinrich G, Das A.: Understanding the coupling effect between lignin and polybutadiene elastomer. J Compos Sci. 2021;5:15. [CrossRef]

- Frigerio P, Zoia L, Orlandi M, Hanel T, Castellani L.: Application of sulphur-free lignins as a filler for elastomers: Effect of hexamethylenetetramine treatment. Bioresources. 2014;9(1):1387-1400. [CrossRef]

- Roy K, Debnath SC, Potiyaraj P.: A review on recent trends and future prospects of lignin based green rubber composites. J Polym Environ. 2020;28:367-387. [CrossRef]

- Taher MA, Wang X, Hasan KMF, Miah MR, Zhu J, Chen J.: Lignin modification for enhanced performance of polymer composites. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2023;6(12):5169–5192. [CrossRef]

- Kraus G.: Swelling of filler-reinforced vulcanizates. J Appl Polym Sci. 1963;7(3):861-871. [CrossRef]

- Kruželák J, Hložeková K, Kvasničáková A, Džuganová M, Chodák I, Hudec I.: Application of plasticizer glycerol in lignosulfonate-filled rubber compounds based on SBR and NBR. Materials. 2023;16:635. [CrossRef]

- Kruželák J, Hložeková K, Kvasničáková A, Džuganová M, Hronkovič J, Preťo J, Hudec I.: Calcium-lignosulfonate-filled rubber compounds based on NBR with enhanced physical–mechanical characteristics. Polymers. 2022;14:5356. [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska M, Krzywania-Kaliszewska A, Zaborski M.: Ionic liquids applied to improve the dispersion of calcium oxide nanoparticles in the hydrogenated acrylonitrile-butadiene elastomer. Am J Mater Sci., 2013;3(4):63-69.

- Kruželák J, Sýkora R, Hudec I.: Vulcanization of rubber compounds with peroxide curing systems. Rubber Chem Tech. 2017;90(1):60-88. [CrossRef]

- Bouajila J, Dole P, Joly C, Limare A.: Some laws of a lignin plasticization. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;102(2): 1445–1451. [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa-Coque R, Álvarez-García S, Martín-Martínez JM.: Effect of temperature on the extent of migration of low molecular weight moieties to rubber surface. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2011;31(1):20-28. [CrossRef]

- Yasin UQ, Zawawi EZE, Adnan N, Tahir H, Kamarun D.: Blooming of compounding ingredients in natural rubber compounds under different peroxide loading. Int J Recent Technol Eng. 2019;8(4):7027-7031. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with 1,4-butanediol.

Figure 1.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with 1,4-butanediol.

Figure 2.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with ethylene glycol.

Figure 2.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with ethylene glycol.

Figure 3.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 86%.

Figure 3.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 86%.

Figure 4.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 99%.

Figure 4.

Vulcanization isotherms of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 99%.

Figure 5.

Influence of plasticizers content on torque difference ΔM of rubber compounds.

Figure 5.

Influence of plasticizers content on torque difference ΔM of rubber compounds.

Figure 6.

Influence of plasticizers content on scorch time ts1 of rubber compounds.

Figure 6.

Influence of plasticizers content on scorch time ts1 of rubber compounds.

Figure 7.

Influence of plasticizers content on optimum cure time tc90 of rubber compounds.

Figure 7.

Influence of plasticizers content on optimum cure time tc90 of rubber compounds.

Figure 8.

Influence of plasticizers content on cure rate R of rubber compounds.

Figure 8.

Influence of plasticizers content on cure rate R of rubber compounds.

Figure 9.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with 1,4-butanediol in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 9.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with 1,4-butanediol in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 10.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with ethylene glycol in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 10.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with ethylene glycol in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 11.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 86% in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 11.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 86% in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 12.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 99% in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 12.

Dynamic complex viscosity η* of rubber compounds plasticized with glycerol 99% in dependence on shear rate.

Figure 15.

Influence of plasticizers content on hardness of vulcanizates.

Figure 15.

Influence of plasticizers content on hardness of vulcanizates.

Figure 16.

Influence of plasticizers content on elongation at break of vulcanizates.

Figure 16.

Influence of plasticizers content on elongation at break of vulcanizates.

Figure 17.

Influence of plasticizers content on tensile strength of vulcanizates.

Figure 17.

Influence of plasticizers content on tensile strength of vulcanizates.

Figure 18.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied 1,4-butanediol: (A) reference plasticizer free vulcanizate, (B) vulcanizate with 10 phr of 1,4-butanediol, (C) vulcanizate with 20 phr of 1,4-butanediol, (D) vulcanizate with 30 phr of 1,4-butanediol.

Figure 18.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied 1,4-butanediol: (A) reference plasticizer free vulcanizate, (B) vulcanizate with 10 phr of 1,4-butanediol, (C) vulcanizate with 20 phr of 1,4-butanediol, (D) vulcanizate with 30 phr of 1,4-butanediol.

Figure 19.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied ethylene glycol: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of ethylene glycol, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of ethylene glycol, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of ethylene glycol.

Figure 19.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied ethylene glycol: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of ethylene glycol, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of ethylene glycol, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of ethylene glycol.

Figure 20.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied glycerol86%: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of glycerol86%, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of glycerol86%, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of glycerol86%.

Figure 20.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied glycerol86%: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of glycerol86%, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of glycerol86%, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of glycerol86%.

Figure 21.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied glycerol99%: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of glycerol99%, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of glycerol99%, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of glycerol99%.

Figure 21.

SEM images of vulcanizates with applied glycerol99%: (A) vulcanizate with 10 phr of glycerol99%, (B) vulcanizate with 20 phr of glycerol99%, (C) vulcanizate with 30 phr of glycerol99%.

Figure 22.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with 1,4-butanediol in dependence on time.

Figure 22.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with 1,4-butanediol in dependence on time.

Figure 23.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with ethylene glycol in dependence on time.

Figure 23.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with ethylene glycol in dependence on time.

Figure 24.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with glycerol 86% in dependence on time.

Figure 24.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with glycerol 86% in dependence on time.

Figure 25.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with glycerol 99% in dependence on time.

Figure 25.

Specific weight loss of vulcanizates plasticized with glycerol 99% in dependence on time.

Figure 26.

Influence of plasticizers content on specific weight loss of vulcanizates after 24 hours.

Figure 26.

Influence of plasticizers content on specific weight loss of vulcanizates after 24 hours.

| Mixing step. |

Mixing time |

Mixing material |

Mixing conditions |

| 1. Step |

1 min |

Rubber |

90 °C, 55 rpm |

| 1 min |

ZnO + stearic acid |

90 °C, 55 rpm |

| 4 min |

Filler + plasticizer |

90 °C, 55 rpm |

| |

Cooling and homogenization of the compounds |

| 2. Step |

4 min |

Sulfur + CBS |

90 °C, 55 rpm |

| |

Cooling and homogenization of the compounds |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).