1. Introduction

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) has risen sharply in recent decades, posing a significant public health challenge [

1]. One-fifth of adults in the United States and Europe are affected, with global prevalence estimates ranging from 12.5% to 31.4% [

2]. Alarmingly, in 2020, approximately 3% of children and 5% of adolescents worldwide were also diagnosed with MetS [

3], highlighting the increasing burden of this condition at an early age and the urgent need for MetS prevention.

MetS is a major driver of the global cardiovascular disease crisis, substantially increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. It is characterized by interconnected cardiometabolic abnormalities, including hyperglycemia (insulin resistance), dyslipidemia (reduced serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and elevated triglycerides), and hypertension, often accompanied by abdominal obesity. The diagnosis of MetS requires the presence of at least three of these metabolic abnormalities [

2,

3,

4].

In Taiwan, according to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, MetS-related diseases accounted for 27.4% of all deaths in 2023, based on the top ten leading causes of mortality. These included heart disease (excluding hypertensive diseases) (11.4%), cerebrovascular disease (6.0%), diabetes (5.7%), and hypertensive diseases (4.3%). Notably, this proportion was now comparable to that of malignant neoplasms (25.8%), underscoring the severe public health implications of MetS [

5].

Beyond its impact on chronic disease prevalence and mortality, MetS imposes a substantial economic burden. Global healthcare expenditures and the loss of potential economic productivity related to MetS amount to trillions of dollars [

1]. Currently, there is no single pharmacological treatment for MetS, and its management typically requires multiple medications. However, polypharmacy may lead to adverse effects and decreased patient adherence to medication [

6]. Therefore, developing effective strategies for disease prevention has become a critical research priority. One promising approach is the development of functional foods specifically designed to mitigate the risk of MetS-related diseases.

Numerous studies have widely recognized fruits, vegetables, and other plant-based products as key dietary components for preventing MetS due to their abundance of phytochemicals, also known as natural bioactive compounds. Phytochemicals can be categorized into several classes based on their chemical structure and biological activity, including polyphenols, carotenoids, alkaloids, phytosterols, nitrogen-containing compounds, and organosulfur compounds. These plant-derived compounds exhibit diverse biological activities and provide various health benefits [

6,

7,

8].

Oxidative stress has been strongly associated with the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, including MetS, cancer, atherosclerosis, malaria, Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, neurodegenerative disorders, and preeclampsia [

9]. Phytochemicals serve as potent antioxidants, which may help mitigate inflammation and oxidative stress [

10]. Therefore, these compounds have demonstrated protective effects against various diseases, including obesity, diabetes, renal disorders, and cardiovascular disease [

6,

7]. Consequently, recent research has increasingly emphasized the important role of phytochemicals in mitigating MetS progression, highlighting their long-term beneficial effects in managing this condition [

6,

7,

8]. Among phytochemicals, polyphenols have been the most extensively studied [

6]. They have been reported to play a significant role in preventing the development of MetS by lowering plasma glucose levels, reducing blood pressure and body weight, and improving dyslipidemia [

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, carotenoids have been suggested as important supportive compounds in treating MetS and other metabolic disorders [

13].

Tamarillo, also known as the tree tomato (

Solanum betaceum Cav. or

Cyphomandra betacea Sendt.) [

14,

15], is native to South America and is cultivated in several other regions worldwide for its nutrient-rich fruit [

16]. Tamarillo is a rich source of fiber, vitamin C, potassium, phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, carotenoids, and other phytochemicals while low in fat and sodium [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Moreover, it has a relatively high polyphenol content than other tropical fruits [

16]. Due to its rich nutritional and bioactive composition, tamarillo has been proven to exhibit high antioxidant activity [

17], suggesting its potential as a natural antioxidant with protective effects against metabolic syndrome [

19] and cancer [

20]. Additionally, different parts of the tamarillo plant exhibit variations in phytochemical composition and content [

19]. Furthermore, tamarillo wastes and by-products have also been reported to contain a rich nutritional and bioactive composition [

18]. This indicates tamarillo is abundant in phytochemicals, offering health benefits and potential protection against chronic diseases.

The health benefits of these phytochemicals depend on their purity. Therefore, they have significant applications after extraction, developing functional foods and nutraceuticals [

21]. Moreover, the functionality of these bioactive compounds is influenced not only by their concentrations but also by their bioaccessibility and bioavailability after gastrointestinal digestion [

22]. Understanding the factors that influence the bioavailability of phytochemicals is crucial for evaluating their biological significance and efficacy as functional food ingredients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of extraction solvents and simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the phytochemical composition and bioactivity of different parts of tamarillo. First, the optimal water-to-ethanol ratio for extracting the highest amount of phytochemicals was determined, followed by an assessment of their antioxidant capacity and inhibitory effects on key enzymes associated with MetS, including pancreatic lipase (hyperlipidemia), α-amylase and α-glucosidase (hyperglycemia), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) (hypertension). Finally, a simulated gastrointestinal digestion model was employed to evaluate the impact of digestion on the phytochemical content in different parts of tamarillo and to determine whether digestion influences their enzyme inhibitory activity related to MetS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Farmers in Nantou, Taiwan, donated red tamarillos (S. betaceum Cav.) and harvested 22–24 weeks post-anthesis at an altitude of 1,100–1,200 m above sea level. The fruit trees were five years old. Tamarillo fruits were stored at 4°C to 6°C, and their components were separated within a week. After being washed and drained, the fruits had their stems removed before being cut in half using a knife. The mucilage and seeds in the fruit’s center were scooped out with a small spoon, and the pulp was collected. The mucilage and seed mixture were then separated using fine mesh laundry bags.

2.2. Chemicals

Ethanol and methanol were purchased from Avantor Performance Materials (Radnor, PA, USA). Acetone, acarbose, α-amylase (from porcine pancreas, Type VI-B), α-carotene, α-glucosidase (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae), α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), captopril, chlorogenic acid, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent, gallic acid, hippuric acid, hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL), iron (III) chloride, lipase (from porcine pancreas, Type II), lycopene, orlistat, p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (p-NPG), pancreatin (from porcine pancreas, 4 × USP specifications), pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside, pepsin (from porcine gastric mucosa, 4711 U/mg protein), potassium ferricyanide, porcine bile extract, sodium chloride, starch (from potato), 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), Triton X-100, and ACE (from rabbit lung) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rosmarinic acid and zeaxanthin were purchased from ChromaDex, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA), and β-cryptoxanthin was obtained from Extrasynthese Co. (Genay Cedex, France). Sodium carbonate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and sodium phosphate were obtained from Union Chemical Works Ltd. (Hsinchu City, Taiwan). Ethyl acetate was purchased from Macron Fine Chemicals™ (Avantor, PA, USA), and n-hexane was obtained from Tedia Co. Inc. (Fairfield, OH, USA). Hydrochloric acid was purchased from Showa Chemical Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Dialysis bags (molecular weight cut-off of 10,000 Da) were obtained from Membrane Filtration Products, Inc. (Seguin, TX, USA).

2.3. Sample Preparation and Extraction

The samples were subjected to vacuum freeze-drying using a freeze-dryer (FD-20L-6S, Kingmech Co., Ltd., New Taipei, Taiwan) under the following conditions: a vacuum pressure <0.2 mmHg, a chamber temperature of 25°C, and a condenser temperature of −50°C. Dried samples were ground using a mill (RT-30HS, Rong Tsong Precision Technology Co., Taichung, Taiwan) and passed through a 0.7 mm sieve. The resulting powders were sealed in PET/Al/PE laminated bags and stored at −25°C until further extraction.

The dried samples were extracted using water and ethanol at different concentrations (25%, 50%, 75%, and 95%) at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio in a 75°C water bath shaker (150 rpm) for 30 min. After centrifugation (8000 rpm, 10 min; 8060 ×g) using a centrifuge (Himac CR21G, Hitachi High-Technologies Co. Ltd., Minato-Ku, Tokyo, Japan) and filtration, the remaining residues were re-extracted with the same solvent under identical conditions. The supernatants from both extractions were pooled, concentrated under reduced pressure, and subjected to vacuum freeze-drying using a freeze dryer (N-1000, Rikakikai Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The resulting freeze-dried tamarillo extracts were designated 0E, 25E, 50E, 75E, and 95E.

2.4. Determination of Phytochemicals

2.4.1. Total Phenols

The sample solution preparation was modified based on Vasco et al.’s method (2009) [

23]. Precisely weighed amounts of tamarillo freeze-dried extracts were used: 0.02 g of peel, 0.2 g of pulp and mucilage, 0.06 g of seeds, and 0.1 g of whole fruit. Each sample was mixed with 4 mL of 50% methanol and subjected to ultrasonic shaking for 15 min, followed by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 25°C; 2600 ×g) for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, while the residue was re-extracted with 70% acetone under the same conditions. The two supernatants were combined and diluted to a final volume of 10 mL with deionized water. The determination of total phenols was performed according to the method of Mau et al. (2017) [

24].

2.4.2. Total Anthocyanins

The sample solution preparation was modified using Shao et al.’s method (2014a) [

25]. A precisely weighed 0.3 g of freeze-dried tamarillo extract was placed in a test tube and extracted with 3 mL of methanol containing 1 M HCl using ultrasonic shaking for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 5372 rpm (4000 ×g, 25°C) for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to a separate test tube, and the extraction was repeated four additional times. The five supernatants were combined and diluted to a final volume of 20 mL with methanol containing 1 M HCl for analysis. Total anthocyanins were determined using the method of Mau et al. (2017) [

24].

2.4.3. Total Carotenoids

The preparation and determination of total carotenoids were modified from the method of Knockaert et al. (2012) [

26]. A precisely weighed 0.05 g of freeze-dried tamarillo extract from different parts, and the whole fruit was mixed with 4 mL of hexane: acetone: ethanol (2:1:1, v/v) and 1 mL of 10% KOH. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonic shaking for 15 minutes, followed by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 4°C; 3466 ×g) for 5 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a test tube, and the extraction was repeated four additional times. The five supernatants were combined and diluted to a final volume of 25 mL with the extraction solvent for analysis. The determination of total carotenoids was performed according to Knockaert et al.’s method (2012).

2.4.4. Individual Phytochemicals

The sample preparation and determination of hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives, anthocyanins, and carotenoid content in freeze-dried extracts and digested extracts were performed according to Chen et al.’s method (2024) [

19].

2.5. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. Determination of Scavenging Ability on DPPH

Freeze-dried tamarillo extracts and standard compounds, including ascorbic acid, BHA, and α-tocopherol, were precisely weighed, dissolved in 100% methanol, and diluted to appropriate concentrations. The scavenging ability of the samples against DPPH free radicals was analyzed according to Shimada et al.’s method (1992) [

27], and both the scavenging activity and the median effective concentration (EC

50) required to achieve 50% scavenging were calculated.

2.5.2. Determination of Reducing Power

Freeze-dried tamarillo extracts and standard compounds, including ascorbic acid, BHA, and α-tocopherol, were precisely weighed, dissolved in 100% methanol, and diluted to appropriate concentrations. The reducing power of the samples was analyzed according to Oyaizu et al.’s method (1986) [

28], and both the reducing power and the EC

50 were calculated.

2.6. Inhibitory Effects on Enzyme Activities

2.6.1. Pancreatic Lipase

For the pancreatic lipase inhibition assay, P95E, L95E, M95E, and W95E extracts (0.1 g each) and S75E extract (0.4 g) were weighed into glass test tubes and dissolved in 0.75 mL of 5% DMSO. The mixtures were sonicated for 20 min and then diluted to 5 mL with 5% DMSO, followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm (≈2600 × g) for 15 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatants had stock concentrations of 20 mg/mL for P95E, L95E, M95E, and W95E and 80 mg/mL for S75E. These stock solutions were further diluted with 5% DMSO to obtain a range of concentrations for the enzyme assay. Pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity was measured using a modified protocol based on McDougall et al. (2009) [

29] and Luyen et al. (2013) [

30], with orlistat as the positive control. Percentage inhibition at each sample concentration was recorded, and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was calculated.

2.6.2. α-Amylase

For the α-amylase inhibition assay, P95E, L95E, M95E, and W95E extracts (0.12 g each) and the freeze-dried S75E extract (0.4 g) were weighed into test tubes and dissolved in 1 mL of 5% DMSO. The mixtures were sonicated for 15 min, then diluted to 5 mL with 0.02 M Na₂HPO₄ buffer (pH 6.9, containing 0.006 M NaCl) and centrifuged at 4000 rpm (2600 × g) for 15 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatants had stock concentrations of 24 mg/mL for P95E, L95E, M95E, and W95E and 80 mg/mL for S75E. These stock solutions were further diluted with the same phosphate buffer to yield the required concentrations for the assay. α-Amylase inhibitory activity was measured using a modified method established by Pinto et al. (2010) [

31], with acarbose as the positive control. The percentage inhibition at each concentration was determined, and IC₅₀ values were calculated.

2.6.3. α-Glucosidase

For the α-glucosidase inhibition assay, freeze-dried tamarillo extract (0.125 g) was dissolved in 1 mL of 5% DMSO and sonicated for 15 min. The mixture was diluted to 5 mL with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.9) and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm (2600 × g) for 15 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatant had a stock concentration of 25 mg/mL, which was further diluted with the same PBS to prepare a range of concentrations for the assay. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity was measured using a modified method established by Chiang et al. (2014) [

32], with acarbose as the positive control. Percentage inhibition was measured at each concentration, and IC₅₀ values were calculated.

2.6.4. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE)

For the ACE inhibition assay, freeze-dried tamarillo extract (0.09 g) was dissolved in 1 mL of 5% DMSO and sonicated for 15 min. The mixture was diluted to 5 mL with 300 mM NaCl buffer (pH 8.3) and centrifuged at 4000 rpm (2600 × g) for 15 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatant had an approximate stock concentration of 18 mg/mL, and it was further diluted with the NaCl buffer to obtain various concentrations for the assay. ACE inhibitory activity was measured using a modified method established by Actis-Goretta et al. (2006) [

33], with captopril as the positive control. The percentage inhibition at each concentration was determined, and IC₅₀ values were calculated.

2.7. Simulation of In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion and Analysis of Composition and Bioactivity

2.7.1. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

The in vitro gastrointestinal digestion process was simulated based on the methods established by Bouayed et al. (2011) [

34] and Chiang et al. (2014) [

32], with modifications. Tamarillo extracts underwent simulated gastric and intestinal phases, and the resulting digested samples, including the supernatant, insoluble residue, and dialysate fractions, were collected. These samples were analyzed for their bioactive components, including total phenols, total anthocyanins, and total carotenoids, as well as their inhibitory activity against metabolic syndrome-related enzymes.

In the gastric phase, 200 mg of tamarillo extract was mixed with 50 mL of 0.9% NaCl, 4 mL of 0.1 M HCl, and 4 mL of pepsin solution (20 mg/mL in 0.1 M HCl) in serum bottles. The mixture was incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 1 h (100 rpm), maintaining a pH of 2.0–2.5.

In the intestinal phase, a 15.5 cm dialysis bag (molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa) was pre-soaked in 0.9% NaCl solution, sealed at one end with a clip, and filled with 5.5 mL of NaCl and 5.5 mL of 0.5 M NaHCO₃. After removing air bubbles, the dialysis bag was sealed and immediately immersed in the gastric digest. The mixture was incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 45 min (100 rpm) to simulate the transition from the gastric to the intestinal phase, during which the pH was adjusted to approximately 6.5. Subsequently, 18 mL of a pancreatin and porcine bile extract mixture (2 mg/mL pancreatin, 12 mg/mL bile extract dissolved in 0.1 M NaHCO₃) was added, and digestion continued in the shaking water bath at 37°C for 2 h (100 rpm), with the final pH maintained at 7.0–7.5. After digestion, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 20 min to separate the soluble supernatant and the insoluble precipitate. The collected fractions were stored at −20°C to further analyze bioactive compounds, antioxidant capacity, and enzyme inhibition activity. The fraction diffused into the dialysis bag was considered the serum-available portion, representing compounds that could potentially enter systemic circulation [

35].

2.7.2. Determination of Phytochemicals in Digested Extracts

2.7.2.1. Total Phenols

The sample preparation and determination followed the method described in

Section 2.4.1, with slight modifications in sample weight. The weights of the dialysate samples were 0.07 g for P95E, 0.3 g for L95E and M95E, 0.2 g for S75E, and 0.2 g for W95E. For the intestinal supernatant, the weights were 0.06 g for P95E and 0.4 g for L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E. The weights of the intestinal precipitate were 0.012–0.015 g for P95E, 0.013 g for L95E, 0.011 g for M95E, 1.00–1.22 g for S75E, and 0.011–0.012 g for W95E.

2.7.2.2. Total Anthocyanins

The sample preparation and determination followed the method described in

Section 2.4.2, with adjustments to the sample weight. The weights of the dialysate samples were 0.23 g for P95E, 0.3 g for L95E, S75E, and W95E, and 0.273 g for M95E. For the intestinal supernatant, the weight was 0.3 g for freeze-dried digested samples from all tamarillo parts. The weights of the intestinal precipitate were 0.024 g for P95E, 0.067 g for L95E, 0.055 g for M95E, 0.2 g for S75E, and 0.054 g for W95E.

2.7.2.3. Total Carotenoids

The sample preparation and determination followed the method described in

Section 2.4.3, with modifications in sample weight. The dialysate and intestinal supernatant samples were weighted 0.1 g for freeze-dried digested material from all tamarillo parts. The weights of the intestinal precipitate were 0.022 g for P95E, 0.05 g for L95E, M95E, and S75E, and 0.043 g for W95E.

2.7.3. Inhibitory Effects on Enzyme Activities

The determination followed the method described in

Section 2.6.

2.8. Statistics

Each measurement was performed in triplicate. The variance in the experimental data was analyzed by analysis of variance using the Statistical Analysis System software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Duncan’s multiple range test was used to determine the significance of differences among the means at the 0.05 level.

3. Results and Discussion

This study utilized various ratios of binary extraction solvents (water and ethanol) to extract bioactive compounds from different parts of tamarillo. The extract yield and bioactive compound content were determined. The extraction conditions yielding the highest bioactive compound content were selected for further investigation, including identifying individual bioactive compounds and their antioxidant activity and inhibitory effects on enzymes related to MetS prevention. Furthermore, to evaluate the impact of gastrointestinal digestion on the biochemical composition and bioactivity of the extracts, an in vitro gastrointestinal digestion simulation was conducted. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the potential physiological effects of different tamarillo components after digestion in the human gastrointestinal tract. Ultimately, this study aims to determine the optimal processing methods to maximize the bioavailability of tamarillo as a functional supplement, ensuring its efficacy in preventing MetS.

3.1. The Yield of Extraction

The diverse structures of bioactive compounds, along with their varying polarity and solubility, can complicate the extraction process [

36]. Therefore, the extraction method must be carefully optimized for safety and environmental sustainability. In the food industry, the choice of extraction solvents should ensure high efficiency and comply with safety and sustainability standards, making green extraction solvents a preferred option [

37]. Moreover, a single solvent is often insufficient to efficiently extract all bioactive compounds from plant materials. As a result, binary solvent systems, such as water–organic solvent mixtures, are commonly employed to enhance the extraction of both polar and non-polar compounds, thereby improving overall yield and efficiency [

38].

This study extracted freeze-dried tamarillo powder from different fruit parts using water and ethanol in varying ratios (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% ethanol). As shown in

Table S1, the extraction yield of different tamarillo parts decreased as ethanol concentration increased. When extracted with water alone (0E), peel, pulp, mucilage, seeds, and whole fruit yield 26.72%, 65.16%, 92.86%, 17.81%, and 57.64%, respectively. However, as the ethanol concentration increased to 95% (95E), the extraction yields decreased to 11.21%, 41.17%, 56.49%, 6.67%, and 33.68%, respectively.

3.2. Bioactive Compounds

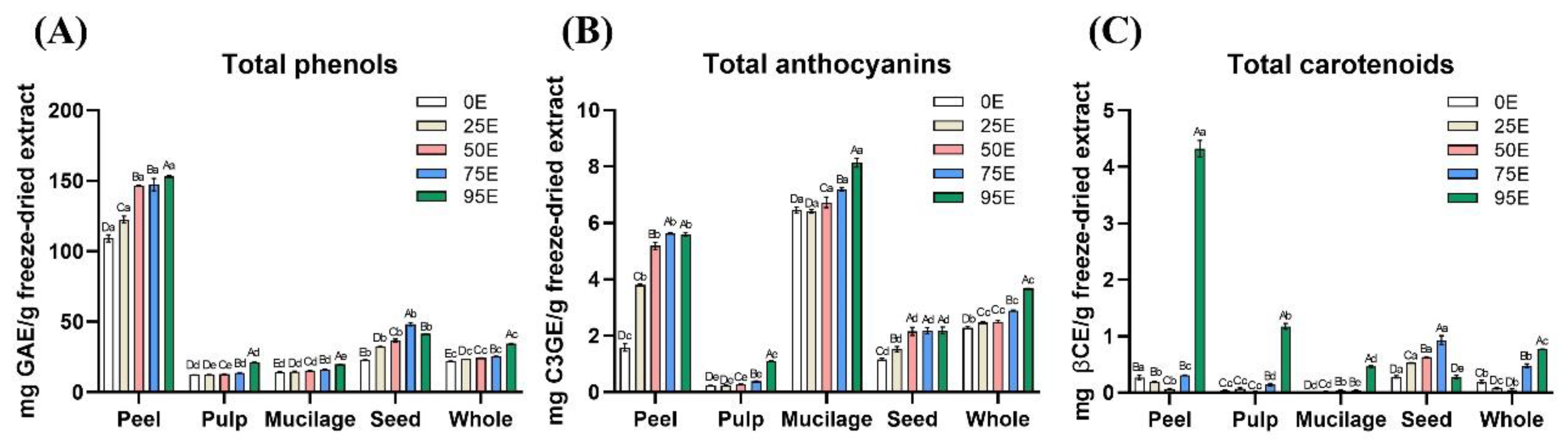

The total phenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids contents in tamarillo extracts from different fruit parts obtained using various water-to-ethanol ratios were analyzed, and the results are presented in

Figure 1. Unlike the extraction yield, which decreased as ethanol concentration increased, the concentrations of these three bioactive compounds exhibited an increasing trend with higher ethanol ratios.

3.2.1. Total Phenols

The total phenols content of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts from different fruit parts is presented in

Figure 1A. Except for seeds, which exhibited the highest total phenols content at 75% ethanol (75E, 48.31 mg GAE/g freeze-dried extract), all other fruit parts showed the highest levels at 95% ethanol (95E). The total phenols content followed the order peel (153.0 mg GAE/g) > whole fruit (34.64) > pulp (21.19) > mucilage (19.85).

3.2.2. Total Anthocyanins

As the ethanol concentration in the extraction solvent increased, the total anthocyanins content in the freeze-dried extracts of different tamarillo parts also increased, with the highest levels generally observed at 95E (

Figure 1B). The total anthocyanins content (mg C3GE/g freeze-dried extract) was of the order: mucilage (8.140) > peel (5.600) > whole fruit (3.674) > seeds (2.195) > pulp (1.110).

3.2.3. Total Carotenoids

As shown in

Figure 1C, the total carotenoid content in freeze-dried tamarillo extracts increased with higher ethanol concentrations, with the highest levels generally observed at 95E, except for seeds, which exhibited the highest content at 75E (0.982 mg βCE/g freeze-dried extract). At 95E, the total carotenoids content (mg βCE/g freeze-dried extract) in different fruit parts was in the descending order of peel (4.324) > pulp (1.174) > whole fruit (0.771) > mucilage (0.466).

3.2.4. Optimal Extraction Conditions

Based on the experimental results, 95% ethanol was the optimal extraction condition for freeze-dried tamarillo peel, pulp, mucilage, and whole fruit, yielding the highest levels of bioactive compounds. In contrast, 75% ethanol was more effective for extracting bioactive compounds from seeds. Therefore, tamarillo extracts obtained using 95% ethanol for peel (P95E), pulp (L95E), mucilage (M95E), and whole fruit (W95E), as well as the extract obtained using 75% ethanol for seeds (S75E), were selected for further analysis to evaluate their antioxidant capacity and enzyme inhibitory effects related to MetS prevention.

3.3. Individual Bioactive Compounds

3.3.1. Hydroxycinnamoyl Derivatives

The chlorogenic acid content (mg/g freeze-dried extract) in the freeze-dried extracts of different tamarillo parts followed the order P95E (74.90) > W95E (9.234) > L95E (5.707) > S75E (1.868) ≈ M95E (1.696) (

Table 1). Similarly, rosmarinic acid content (mg/g freeze-dried extract) was significantly higher in P95E (66.69) than in other parts, followed by W95E (6.697), with the lowest content observed in M95E (0.242). When combining chlorogenic acid and rosmarinic acid, the total hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives content (mg/g freeze-dried extract) was highest in P95E (141.6), followed by W95E (15.93) > L95E (8.934) > S75E (3.412) > M95E (1.938), accounting for 92.55%, 45.99%, 42.16%, 7.06%, and 9.76% of the total phenols content (

Figure 1) in the respective extracts. When recalculated based on extraction yield, the total hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives content (mg/g freeze-dried sample) in P95E, L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E was 15.87, 3.678, 1.094, 0.2146, and 5.365, respectively. Notably, the whole fruit extract (536.5 mg/100 g freeze-dried sample) exhibited a higher total hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives content compared to the Giant Purple cultivar (132.6 ± 0.909 mg/100 g dry weight) and the New Zealand Purple cultivar (421.6 ± 3.082 mg/100 g dry weight) of tamarillo, as reported by Espín et al. (2016) [

39].

3.3.2. Anthocyanins

The individual anthocyanin content in freeze-dried extracts of different tamarillo parts is presented in

Table 1. Among mucilage, seeds, and whole fruit, delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside was the most abundant anthocyanin, with 6.606, 4.179, and 2.186 mg/g freeze-dried extract, respectively. In contrast, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside was predominant in the peel (8.687 mg/g freeze-dried extract), while pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside was most abundant in the mucilage (6.111 mg/g freeze-dried extract). Regarding total anthocyanins content (mg/g freeze-dried extract), mucilage exhibited the highest levels (13.39), followed by peel (10.64) > seeds (7.630) > whole fruit (5.005) > pulp (0.625). Anthocyanins in pulp and seeds may be attributed to residual mucilage. When recalculated based on extraction yield, the total anthocyanins content (mg/g freeze-dried sample) in P95E, L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E was 1.193, 0.257, 7.560, 0.480, and 1.686, respectively. These values were higher than those reported by Espín et al. (2016) [

39] for the purple tamarillo cultivars from Ecuador and New Zealand.

3.3.3. Carotenoids

The carotenoid content in tamarillo extracts is shown in

Table 1. The peel extract contained the highest levels of β-cryptoxanthin (0.928) and β-carotene (0.942). The β-cryptoxanthin was also the predominant carotenoid in all other parts, with concentrations (mg/g freeze-dried extract) following the order L95E (0.240) ≈ W95E (0.238) > M95E (0.085) > S75E (0.061). Additionally, only β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene were detected in M95E, whereas S75E contained β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin. Notably, lycopene and α-carotene were not detected in any extract. The total carotenoid content (mg/g freeze-dried extract) followed the order P95E (1.943) > L95E (0.431) > W95E (0.318) > M95E (0.136) > S75E (0.069). These results align with findings from [

40,

41], which reported that β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene are the primary carotenoids in tamarillo.

3.4. Antioxidation Properties

3.4.1. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Ability

The DPPH radical-scavenging capacity of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts from different fruit parts and whole fruit is presented in

Figure S1A. As the extract concentration increased, the DPPH scavenging activity also increased. At a low concentration (50 μg/mL), the scavenging capacity followed the order P95E (55.24%) > S75E (17.74%) > W95E (14.30%) > L95E (10.09%) > M95E (8.66%). P95E exhibited the highest scavenging activity, exceeding 90% at 100 μg/mL. The EC

50 values (μg extract/mL) for DPPH scavenging activity are presented in

Table 2. The lowest EC

50 value (μg extract/mL), indicating the strongest antioxidant activity, was observed in P95E (45.26), followed by S75E (181.6) > W95E (221.0) > L95E (388.2) ≈ M95E (386.4). When recalculated based on total phenols content, the EC

50 values (μg total phenols/mL) were P95E (9.420) > S75E (10.27) > W95E (12.24) > M95E (14.93) > L95E (15.57). Tamarillo extract showed a strong DPPH radical-scavenging ability compared to standard antioxidants ascorbic acid (15.60 μg/mL), BHA (17.51μg/mL), and α-tocopherol (16.35 μg/mL).

3.4.2. Reducing Power

The reducing power of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts from different fruit parts and whole fruit is presented in

Figure S1B. As the extract concentration increased, the reducing power also increased. At a low concentration (200 μg/mL), the reducing power (absorbance at 700 nm) followed the order P95E (0.873 AU) > W95E (0.179 AU) ≈ S75E (0.175 AU) > M95E (0.119 AU) ≈ L95E (0.117 AU). The EC

50 values for the reducing power assay are presented in

Table 2. The lowest EC

50 value (μg extract/mL), indicating the highest reducing capacity, was observed in P95E (113.3 μg/mL), followed by S75E (597.2 μg/mL) > W95E (618.8 μg/mL) > M95E (938.4 μg/mL) > L95E (956.7 μg/mL). When recalculated based on total phenols content (μg total phenols/mL), the reducing power followed the order P95E (23.58) > S75E (33.77) > W95E (34.27) > M95E (36.26) > L95E (38.37). All extracts' reduced capacity (EC50 value) was significantly stronger than α-tocopherol (118.3 μg/mL). Additionally, P95E, S75E, and W95E exhibited stronger reducing power than BHA (34.98 μg/mL), though all extracts showed lower reducing capacity than ascorbic acid (19.82 μg/mL).

The results of this study demonstrate that tamarillo extracts exhibit strong antioxidant capacity, as evidenced by their DPPH radical-scavenging activity and reducing power. P95E consistently exhibited the highest antioxidant potential among the tested extracts, with the lowest EC

50 values in both assays, followed by S75E and W95E. The strong antioxidant activity of tamarillo extracts can be attributed to their rich bioactive compounds, particularly hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives, anthocyanins, and carotenoids, which are known for their free radical-scavenging and redox properties. Given the well-established link between oxidative stress and inflammation-related diseases [

17,

42], these findings suggest tamarillo extracts may possess anti-inflammatory properties. Moreover, since oxidative stress is a key factor in developing metabolic syndrome, the potent antioxidant activity observed in tamarillo extracts highlights their potential as functional food ingredients for MetS prevention.

3.5. Enzyme Inhibitory Activity

Hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension are key indicators of MetS. Therefore, this study evaluated the ability of tamarillo extracts from different parts of the fruit to inhibit key enzymes associated with these conditions, including pancreatic lipase (involved in fat digestion and absorption), α-amylase and α-glucosidase (involved in carbohydrate hydrolysis), and ACE (related to blood pressure regulation). Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of tamarillo extracts were compared with commercially available medications to assess their potential in preventing MetS.

3.5.1. Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activity

Pancreatic lipase plays an important role in fat digestion and absorption, and its inhibition has been linked to potential anti-obesity effects [

43]. Polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids have been reported to inhibit pancreatic lipase activity, thereby contributing to weight management [

44,

45,

46]. This study evaluated the pancreatic lipase inhibitory capacity of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts derived from different fruit parts and the whole fruit. Except for the seed extract, all tamarillo extracts exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition of pancreatic lipase, with inhibition increasing as extract concentration increased (

Figure S2). At a low concentration (1 mg/mL), the inhibitory effects of the tamarillo extracts followed the order L95E (56.68%) > M95E (34.57%) > W95E (31.75%) > P95E (6.390%) > S75E (0%). At 3 mg/mL, L95E achieved 90% inhibition, whereas M95E and W95E required a higher concentration of 4 mg/mL to surpass 90% inhibition. In contrast, S75E exhibited no inhibition at 5 mg/mL; even at 20 mg/mL, its inhibition rate remained relatively low at 59.81% (

Figure S2B). The IC

50 values (the concentration required to inhibit 50% of enzyme activity) for tamarillo extracts and orlistat are presented in

Table 3, with inhibitory potency ranking as follows: Orlistat (9.066 ng/mL) > L95E (0.882 mg/mL) > M95E (1.637 mg/mL) > W95E (1.861 mg/mL) > P95E (2.964 mg/mL) > S75E (16.67 mg/mL). These findings indicate that orlistat exhibits significantly higher pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity than tamarillo extracts. However, the consumption of orlistat has been associated with adverse side effects such as fecal incontinence, bloating, and steatorrhea [

47].

3.5.2. α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

α-Amylase and α-glucosidase are key carbohydrate-digesting enzymes associated with postprandial hyperglycemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes. α-Amylase catalyzes the cleavage of α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, breaking down polysaccharides into smaller oligosaccharide fragments, while α-glucosidase further hydrolyzes these oligosaccharides into glucose. Inhibiting these enzymes can slow carbohydrate digestion and absorption, thereby helping to regulate postprandial blood glucose levels [

48,

49,

50]. Additionally, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and carotenoids have been reported to inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities, suggesting their potential role in glycemic control [

51,

52,

53].

The α-amylase inhibitory activity of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts is presented in

Figure S3. The inhibition rate increased with extract concentration, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect. At 1 mg/mL, the α-amylase inhibition of tamarillo extracts followed the order W95E (6.419%) > L95E (5.387%) ≈ M95E (4.954%) > S75E (2.966%) > P95E (1.685%). At 3 mg/mL, L95E exhibited over 90% inhibition of α-amylase activity. For W95E and M95E, the concentrations required to achieve 90% inhibition were 4 mg/mL and 5 mg/mL, respectively. P95E showed a rapid increase in α-amylase inhibition between 5 mg/mL and 6 mg/mL, rising from 27.32% to 89.02% (

Figure S3A). Meanwhile, S75E required 15 mg/mL and 20 mg/mL concentrations to reach inhibition rates of 47.12% and 86.91%, respectively (

Figure S3B). The IC

50 values for tamarillo extracts and acarbose, a commercial α-amylase inhibitor, are shown in

Table 3. The inhibitory potency followed the order acarbose (5.525 μg/mL) > L95E (2.369 mg/mL) > W95E (3.132 mg/mL) > M95E (3.351 mg/mL) > P95E (5.368 mg/mL) > S75E (14.80 mg/mL). These results indicate that acarbose exhibits significantly stronger α-amylase inhibitory activity than tamarillo extracts.

The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts from different fruit parts and the whole fruit is shown in

Figure S4. The inhibitory effect increased with extract concentration, demonstrating a dose-dependent response. At a low concentration (2 mg/mL), the inhibition rates of tamarillo extracts followed the order P95E (61.62%) > S75E (37.48%) > W95E (17.00%) > L95E (2.792%) > M95E (0%). At 10 mg/mL, the inhibition rates for different tamarillo parts were as follows: peel (96.80%) > seeds (75.31%) > whole fruit (72.50%) > pulp (70.35%) > mucilage (57.33%). The IC

50 values (

Table 3), representing the concentration required to inhibit 50% of α-glucosidase activity, followed the order acarbose (91.21 μg/mL) > P95E (1.623 mg/mL) > S75E (3.581 mg/mL) > W95E (5.534 mg/mL) > L95E (6.299 mg/mL) > M95E (8.856 mg/mL).

Acarbose is a commonly prescribed drug for type 2 diabetes that inhibits both α-amylase and α-glucosidase, slowing glucose absorption and reducing postprandial blood sugar spikes. Indeed, the IC

50 values of acarbose for inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase were significantly lower than those of tamarillo extracts, indicating its superior inhibitory potency. However, acarbose consumption has been associated with adverse side effects such as abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, bloating, and hepatotoxicity [

54,

55].

3.5.3. ACE Inhibitory Activity

The renin-angiotensin system regulates blood pressure, cardiac function, and vascular homeostasis. Renin catalyzes the conversion of angiotensinogen into angiotensin I, which is subsequently cleaved by ACE to generate angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor. Inhibiting ACE activity is a well-established strategy for managing hypertension [

56]. Polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids have been reported to contribute to ACE inhibition, demonstrating potential antihypertensive effects [

57,

58,

59].

The ACE inhibitory activity of freeze-dried tamarillo extracts is presented in

Figure S5. The inhibition rate increased with extract concentration, exhibiting a dose-dependent effect. At a low concentration (1 mg/mL), the ACE inhibition rates followed the order P95E (42.73%) ≈ S75E (42.65%) > W95E (26.46%) ≈ M95E (24.58%) > L95E (15.39%). At 6 mg/mL, the inhibition rates increased to P95E (87.12%) > S75E (83.26%) ≈ W95E (81.05%) ≈ M95E (78.47%) ≈ L95E (75.40%). The IC

50 values (

Table 3), representing the concentration required to inhibit 50% of ACE activity, followed the order captopril (0.481 ng/mL) > P95E (1.435 mg/mL) ≈ S75E (1.417 mg/mL) > W95E (3.479 mg/mL) ≈ M95E (3.587 mg/mL) > L95E (4.038 mg/mL).

Captopril, a widely used antihypertensive drug, effectively inhibits ACE activity. As evidenced by the results, the IC

50 value of captopril was significantly lower than those of tamarillo extracts, indicating its superior inhibitory potency. However, the use of captopril has been associated with adverse side effects, including chronic cough, taste disturbances, and skin rashes [

60].

These findings suggest that freeze-dried tamarillo extracts have the potential for anti-obesity effects and the prevention of type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Although their inhibitory effects were not as strong as those of pharmaceutical drugs, concerns remain regarding the side effects associated with drug use. Consequently, there is growing interest in natural, food-based alternatives for inhibiting enzymes related to MetS, positioning tamarillo extracts as promising functional ingredients for its prevention.

3.6. Bioactive Compounds After Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Based on the findings of this study, tamarillo extracts are rich in bioactive compounds and exhibit strong inhibitory activity against enzymes associated with MetS. However, upon ingestion, these bioactive compounds undergo gastrointestinal digestion, during which they may be modified or degraded by digestive enzymes [

61]. Therefore, understanding the effects of simulated digestion on these compounds' bioactivity, bioaccessibility, and bioavailability is essential for further research, particularly in developing strategies to enhance their stability and functionality [

62]. This knowledge can also support the development of targeted delivery techniques, facilitating the formulation of functional ingredients and determining effective dosages [

63]. In this study, freeze-dried tamarillo extracts were subjected to simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion to evaluate changes in the content and bioactivity of bioactive compounds before and after digestion. Following the digestion simulation, the supernatant was collected as the soluble fraction, while the precipitate represented the insoluble portion. The dialysate inside the dialysis bag was also collected for analysis, as this fraction represents the compounds that have entered the bloodstream. This fraction is crucial, as it defines the bioavailability of the compounds, indicating their potential to exert physiological functions [

64,

65].

3.6.1. Total Polyphenols

The total phenols content (mg GAE/200 mg freeze-dried extract) of tamarillo extracts before and after simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion is presented in

Table 4. Among the intestinal supernatants (soluble fraction), P95E exhibited the highest total phenols content (34.32), followed by S75E (11.87) > W95E (10.28) > L95E (7.188) ≈ M95E (7.113). Notably, the total phenols content in the soluble fraction was significantly increased compared to the non-digested extracts. In contrast, the intestinal precipitate (insoluble fraction) showed a marked decrease in total phenols content relative to the non-digested extracts, with S75E having the highest content at 1.541 mg GAE, representing only 15.95% of its pre-digestion level. Similar observations have been reported in the literature. For instance, He et al. (2017) found that the total phenols content increased after digestion in 22 types of fruit juices [

66], while Hwang et al. (2023) noted that cherry tomatoes maintained their phenols content during gastric digestion but experienced a significant reduction following intestinal digestion [

67]. These findings underscore the sensitivity of phenolic compounds to the gastrointestinal environment. Phenolic compounds are highly responsive to pH changes; they tend to remain stable under mildly acidic conditions, such as those in the stomach but are prone to degradation in the more alkaline conditions of the small intestine [

68]. This degradation may be further influenced by interactions between hydrolyzed polyphenols and proteins and the conversion of certain polyphenols into their respective breakdown products during intestinal digestion [

69,

70]. The study results indicate that the total phenols content in the dialysate significantly decreased after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. The total phenols content (mg GAE/200 mg freeze-dried extract) in the dialysate for P95E, L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E was 3.168, 0.793, 0.746, 1.146, and 1.025, respectively. During the dialysis phase, only 10.36–18.79% of the total phenolic compounds could pass through the dialysis membrane, suggesting that only a small fraction of polyphenols can reach the bloodstream. The permeability of polyphenols through the dialysis membrane depends on several factors, including molecular size, degree of polymerization, and the presence of sugar moieties. Generally, monomeric or glycosylated derivatives are more likely to pass through the membrane than their polymerized counterparts [

71]. These findings highlight the potential challenges in the bioavailability of polyphenols and underscore the importance of further research into strategies for enhancing their absorption and physiological effectiveness.

3.6.2. Total Anthocyanins

The health benefits of anthocyanins depend highly on their bioavailability after digestion, which is influenced by their source, dosage, and the experimental model. Numerous studies on anthocyanin-rich food consumption have demonstrated that only a small fraction of ingested anthocyanins are absorbed intact into the bloodstream or excreted in the urine [

72]. After oral ingestion, anthocyanins remain stable in the stomach's acidic environment (pH 1.5–5.0), where some may be absorbed. However, upon entering the intestine, exposure to higher pH levels (pH 5.6–7.9), enzymatic activity, and gut microbiota metabolism contribute to their extensive degradation, further limiting their absorption into the bloodstream [

72,

73]. As a result, a substantial portion of anthocyanins is lost during digestion, significantly reducing their bioavailability. Our findings (

Table 4) further confirm the significant decline in total anthocyanin content after digestion. In the intestinal supernatant, detectable levels of total anthocyanins were observed only in P95E and M95E, with concentrations of 0.589 mg C3GE/200 mg freeze-dried extract, and 1.406 mg C3GE/200 mg freeze-dried extract, corresponding to 52.59% and 86.36% of their pre-digestion content, respectively. However, no anthocyanins were retained in the intestinal precipitate, indicating their complete degradation or solubilization during digestion. Additionally, anthocyanin permeability through the dialysis membrane, which simulates potential absorption into the bloodstream, was detected in P95E, L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E, with concentrations of 0.176, 0.021, 0.267, 0.063, and 0.068 mg C3GE/200 mg freeze-dried extract, respectively. This suggests that only 9.25% to 16.40% of the anthocyanins were potentially bioavailable for systemic circulation. Similarly, Yamazaki et al. reported that only 10–20% of anthocyanins are actively transported into the bloodstream through gastric epithelial cells, primarily in the form of their metabolites [

74]. These findings highlight the substantial loss of anthocyanins during digestion and their limited bioavailability, emphasizing the need for strategies to enhance their stability and absorption.

3.6.3. Total Carotenoids

The total carotenoid content of tamarillo extracts before and after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion simulation is presented in

Table 4. In the intestinal supernatant, P95E exhibited the highest carotenoid content (0.435 mg βCE/200 mg freeze-dried extract), retaining 50.29% of its pre-digestion level, whereas S75E had the lowest content (0.038 mg βCE/200 mg freeze-dried extract), retaining only 20.43%. In the intestinal precipitate, the carotenoid content across different tamarillo extracts ranged from 0.003 to 0.067 mg βCE/200 mg freeze-dried extract, accounting for only 1.95–7.75% of the initial amount. Furthermore, only 9.36–17.53% of the total carotenoids from P95E, L95E, M95E, S75E, and W95E could pass through the dialysis membrane, which simulates potential absorption into the bloodstream. The concentrations detected in the dialysate were 0.081, 0.024, 0.016, 0.020, and 0.027 mg βCE/200 mg freeze-dried extract. These findings indicate that only a small fraction of carotenoids is bioavailable after digestion. Carotenoids are extremely sensitive to various environmental factors, including light exposure, oxidation, and pH fluctuations. Acidic conditions, in particular, significantly accelerate their decomposition, whereas degradation tends to be lower at pH values ranging from 6.0 to 7.0 [

67]. Therefore, the acidic environment of gastric juice may influence the stability and subsequent uptake of β-carotene [

75]. These results align with our findings, demonstrating a significant decline in total carotenoid content following digestion simulation and confirming that only a limited portion of carotenoids is available for systemic circulation.

3.7. Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Dialysate After Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Phytochemicals are susceptible to chemical degradation when exposed to environmental factors such as pH fluctuations, heat, light, oxygen, and prooxidants [

76]. Similarly, polyphenols from different plant sources or types exhibit varying compositional and bioactivity changes after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. These variations are influenced by multiple factors, including the inherent chemical structures of phytochemicals and the food matrix, which collectively impact their stability and bioavailability [

77,

78]. Hwang and Kim (2023) reported a significant reduction in total polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and antioxidant capacity in cherry tomatoes after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion [

67]. However, other studies have shown that despite digestion, certain plant infusions still retained their antioxidant potential and the ability to inhibit α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE, suggesting their potential antidiabetic and antihypertensive effects [

77].

The IC

50 values for inhibiting pancreatic lipase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE in the dialysis phase of in vitro digested tamarillo extracts are presented in

Table 5. The results indicate a significant increase in IC

50 values across all enzyme assays, suggesting that digestion reduces the biochemical activity of tamarillo extracts. A comparison of different fruit parts revealed varying degrees of increase in IC

50 values after digestion. P95E exhibited the highest increase (approximately 8.2–9.0 times), followed by S75E and W95E (6.5–6.9 times and 5.8–6.4 times, respectively). L95E and M95E showed the lowest increase (approximately 4.9–5.2 and 4.9–5.3 times, respectively). These findings suggest that the resistance of tamarillo extracts to digestive degradation varies among different fruit parts. The pulp and mucilage retained the highest biochemical activity, whereas the peel exhibited the lowest retention. Nevertheless, all extracts retained some degree of inhibition against pancreatic lipase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE, which are key enzymes involved in obesity, hyperglycemia, and hypertension. These results highlight the potential of tamarillo extracts as functional ingredients, as they retain partial effectiveness in preventing metabolic syndrome even after digestion.

This study initially optimized the extraction conditions for different tamarillo fruit parts using a water-ethanol solvent mixture, revealing that the extracts were rich in polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids. These bioactive compounds exhibited strong antioxidant activity and significant inhibitory effects on pancreatic lipase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE, suggesting that tamarillo may offer potential benefits in preventing obesity, hyperglycemia and hypertension, thereby contributing to the prevention of MetS.

Our findings align with previous studies indicating that total polyphenols, anthocyanins, carotenoids, and biochemical activities in plants are affected by digestion to varying degrees. This study specifically analyzed the soluble, insoluble, and dialysis phases post-digestion. While most tamarillo extracts exhibited reduced total polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids after digestion, the soluble phase contained a higher total polyphenols content than the undigested extracts, suggesting improved polyphenols solubility during digestion.

Since the dialysis phase represents bioavailable compounds capable of entering the bloodstream, we further evaluated its ability to inhibit pancreatic lipase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE. The results showed that the IC50 values for these enzymes were significantly higher than those of the undigested extracts, indicating that digestion and absorption reduce overall biochemical activity. Nevertheless, the extracts retained some inhibitory effects on these key enzymes associated with MetS, suggesting they still hold potential for MetS prevention.

This study underscores the importance of considering the effects of gastrointestinal digestion and systemic absorption on the bioactivity of plant-derived compounds. Food processing technologies such as microencapsulation should be explored to enhance their bioavailability and stability. These strategies could improve the functional efficacy of tamarillo extracts as potential dietary supplements or functional foods for metabolic syndrome prevention.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated tamarillo extracts' phytochemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and enzyme inhibitory effects, assessing the impact of different extraction solvents and simulated gastrointestinal digestion. The results demonstrated that ethanol concentration significantly influenced the extraction efficiency of bioactive compounds, with 95% ethanol yielding the highest levels of polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids in most fruit parts. Tamarillo extracts exhibited strong antioxidant activity and notable inhibitory effects against key metabolic syndrome-related enzymes, including pancreatic lipase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and ACE. However, simulated gastrointestinal digestion reduced phytochemical content and enzyme inhibitory activity, although some bioactivity remained in the dialysate fraction, indicating potential bioavailability. This result could serve as a reference for subsequent animal or human trials on tamarillo extracts. These findings highlight the functional potential of tamarillo as a natural source of bioactive compounds for MetS prevention. Future research should focus on enhancing the stability and bioavailability of tamarillo phytochemicals, such as through encapsulation technologies or food matrix integration, to maximize their health benefits in functional food applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.C. and S.D.L.; Data curation, S.Y.C., Q.F.Z., H.S.S, and S.D.L.; Formal analysis, S.Y.C., Q.F.Z., H.S.S, and S.D.L.; Funding acquisition, S.D.L.; Investigation, S.Y.C., Q.F.Z. and S.D.L; Methodology, S.Y.C., Q.F.Z., H.S.S, and S.D.L.; Project administration, S.D.L.; Supervision, S.D.L.; Visualization, S.Y.C.; Writing - original draft, S.Y.C.; Writing - review & editing, S.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.