Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Morphological and Habitat Studies

2.2. Molecular analyses

| Taxon | Provenance (herbarium voucher) | Source | ITS | Source | matK |

| Tamarix gallica L. | France: Saintes Maries de la Mer (ABH-57865) |

Villar et al. [49] | MH626294 | − | − |

| Italy: Sardinia | Meimberg et al. [50] | − | − | AF204861 | |

| Myricaria germanica L. | Kazakhstan: Zajsanskaya depression (LE) | Zhang et al. [51] | KJ808607 | − | − |

| China: Unspecified (CPG-11863) |

Chen et al. [52] | − | − | KX526795 | |

| Reaumuria alternifolia (Labill.) Britten1 | Azerbaijan: Caucasus (MW) | Zhang et al. [53] | KJ729627 | − | − |

| Reaumuria songarica (Pall.) Maxim. | China: Xinjiang (M) | Zhang et al. [51] | OQ617495 | − | − |

| China: Xinjiang (TURP) | Song et al. [54] | − | − | MT918094 | |

| Frankenia anneliseae M.B.Crespo & al. | South Africa: Klipfontein (ABH-76891) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183455 | − | − |

| South Africa: Skoverfontein (ABH-83196) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183456 | This paper | PV258653 | |

| South Africa: Klipfontein (ABH-76872) | − | − | This paper | PV258654 | |

| F. boissieri Reut. ex Boiss. | Spain: Huelva, Lepe, El Terrón (ABH-83544) | This paper | PV241633 | This paper | PV258655 |

| Portugal: Algarve, Vale de Parra (ABH-73553) | This paper | PV241634 | − | − | |

| F. cespitosa Lowe | Portugal: Madeira Is., Porto Santo, Morenos (MA-902612) | This paper | PV241635 | − | − |

| F. capitata Webb & Berthel. | Spain: Canary Is., Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Isleta (ABH-83612) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183458 | This paper | PV258656 |

| Spain: Canary Is., Lanzarote, Teguise (ABH-83884) | This paper | PV241636 | − | − | |

| Spain: Canary Is., Lanzarote, Yaiza (ABH-83881) | This paper | PV241637 | This paper | PV258658 | |

| Spain: Canary Is., Lanzarote, Yaiza (ABH-83880) | − | − | This paper | PV258657 | |

| F. composita Pau & Font Quer | Morocco: Al Hoceïma, Cala Iris (ABH-81590) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183459 | This paper | PV258659 |

| Spain: Murcia, El Carmolí (ABH-84195) | This paper | PV241638 | This paper | PV258660 | |

| F. corymbosa Desf. | Spain: Alicante, Santa Pola (ABH-79956) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183462 | This paper | PV258663 |

| Morocco: Nador, Punta Charrana (ABH-54294) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183461 | This paper | PV258662 | |

| Morocco: Al-Hoceïma (ABH-54526) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183460 | − | − | |

| Spain: Murcia, Cabo Cope (ABH-83531) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183463 | This paper | PV258661 | |

| F. dinteri M.Á.Alonso & al., nom. nov. | Namibia: Goageb (ABH-76804) | This paper | PV241642 | This paper | PV258666 |

| South Africa: Onseepkans (ABH-83234) | This paper | PV241639 | This paper | PV258667 | |

| South Africa: Daberas Farm (ABH-83264) | This paper | PV241640 | This paper | PV258665 | |

| South Africa: Augrabies (ABH-83265) | This paper | PV241641 | This paper | PV258664 | |

| F. ericifolia C.Sm. ex DC., nom. cons. prop. | Spain: Canary Isl., Tenerife (ABH-79975) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183464 | This paper | PV258668 |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Tenerife, Güímar (ABH-83613) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183465 | − | − | |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Tenerife, Granadilla de Abona (ABH-83873) | This paper | PV241646 | This paper | PV258669 | |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Tenerife, Malpaso, IA3069 (MA) | This paper | PV241643 | This paper | PV258670 | |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Lanzarote, Caleta del Mojón Blanco (ABH-83889) | This paper | PV241644 | This paper | PV258671 | |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Lanzarote, Risco de Famara (ABH-83893) | This paper | PV241645 | This paper | PV258672 | |

| F. fruticosa J.C.Mannig & Helme | South Africa: Moedverloren (ABH-76898) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183466 | − | − |

| F. hirsuta L. | Italy: Puglia, Bari (ABH-84234) | This paper | PV241648 | This paper | PV258673 |

| Cyprus: Akamas (MA-526424) | This paper | PV241647 | − | − | |

| F. ifniensis Caball. | Morocco: Sidi Ifni to Oued Noun (MA-758515) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183468 | This paper | PV258674 |

| Morocco: El Farsia (MA-712824) | This paper | PV241649 | − | − | |

| Morocco: Gelmim (MA-902279) | This paper | PV241650 | − | − | |

| F. laevis L. | Libya: Cyrenaica, Jbel Akhdar (MA-826355) | This paper | PV241652 | − | − |

| France: Aude, Étang de La Palme (ABH-70584) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183469 | This paper | PV258676 | |

| Spain: Mallorca, Conejera (ABH-57810) | This paper | PV241651 | This paper | PV258675 | |

| F. nummularia M.B.Crespo & al. | South Africa: Kookfontein River (ABH-83290) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183471 | − | − |

| South Africa: Tankwa Karoo (ABH-83295) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183472 | This paper | PV258677 | |

| F. pseudoericifolia Rivas Mart. & al. | Portugal: Cape Verde, São Antão (MA-0906845) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183473 | − | − |

| F. pulverulenta L. | South Africa: Redelinghuis (ABH-77205) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183474 | − | − |

| South Africa: Skoverfontein (ABH-83195) | This paper | PV241657 | − | − | |

| Spain: Teruel, Alcañiz (ABH-73564) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183475 | − | − | |

| Spain: Alicante, Cabo de las Huertas (ABH-74763) | This paper | PV241653 | This paper | PV258678 | |

| Spain: Albacete, Fuentealbilla (ABH-40820) | This paper | PV241654 | − | − | |

| Morocco: Melga-el-Ouidane (ABH-59986) | This paper | PV241655 | This paper | PV258679 | |

| Spain: Canary Isl., Tenerife, Puerto de la Cruz (ABH-79974) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183477 | This paper | PV258680 | |

| Italy: Puglia, Torre Spechiola (ABH-84244) | This paper | PV241656 | This paper | PV258681 | |

| Spain: Alicante, Cabo de las Huertas (ABH-41853) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183476 | − | − | |

| F. repens (P.J.Bergius) Fourc. | South Africa: S of Hondeklipbaai (ABH-76862) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183479 | − | − |

| South Africa: Velddrift (ABH-76849) | − | − | This paper | PV258682 | |

| South Africa: S of Groenrivier (ABH-76868) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183478 | This paper | PV258683 | |

| F. sahariensis M.Á.Alonso & al., nom. nov. | Morocco: Guelmim to Tan Tan (MA-786164) | This paper | PV241658 | This paper | PV258684 |

| Morocco: Sidi Ifni (MA-913227) | This paper | PV241659 | This paper | PV258685 | |

| F. salsuginea Adıgüzel & Aytaç2 | Turkyie: Tuz Gölii, salty lagoon (ABH-45933) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183467 | This paper | PV258687 |

| Turkyie: Dörtyol (MA-561567) | This paper | PV241660 | This paper | PV258686 | |

| F. thymifolia Desf. | Algeria: Bougtob, Chott Cherguí (ABH-59344) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183481 | This paper | PV258688 |

| Spain: Zaragoza: Bujaraloz (ABH-75454) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183480 | This paper | PV258689 | |

| F. velutina Brouss. ex DC. | Morocco: Essaouira (ABH-79929) | Crespo et al. [12] | OR183482 | This paper | PV258690 |

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic treatment and description of new taxa

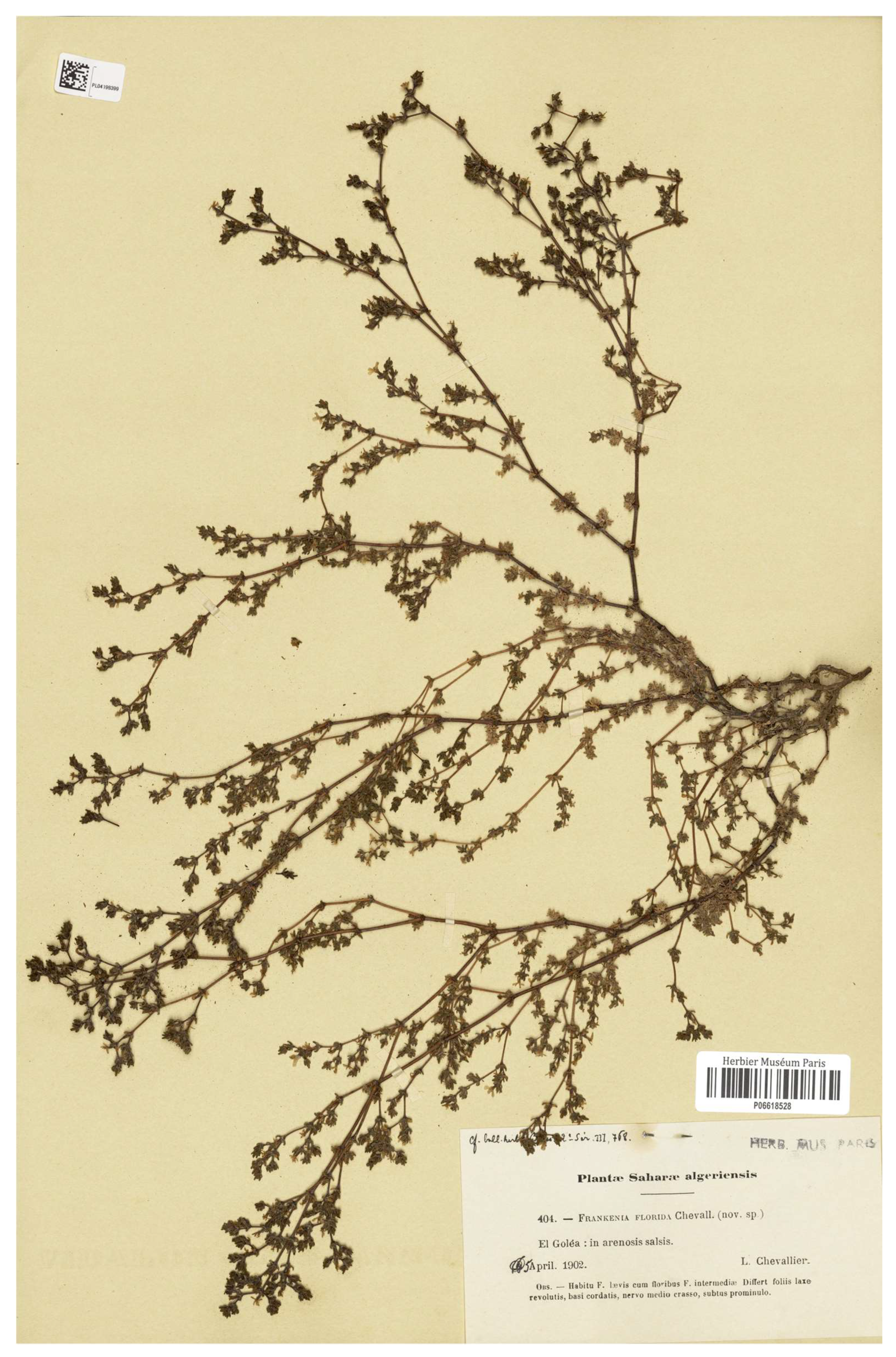

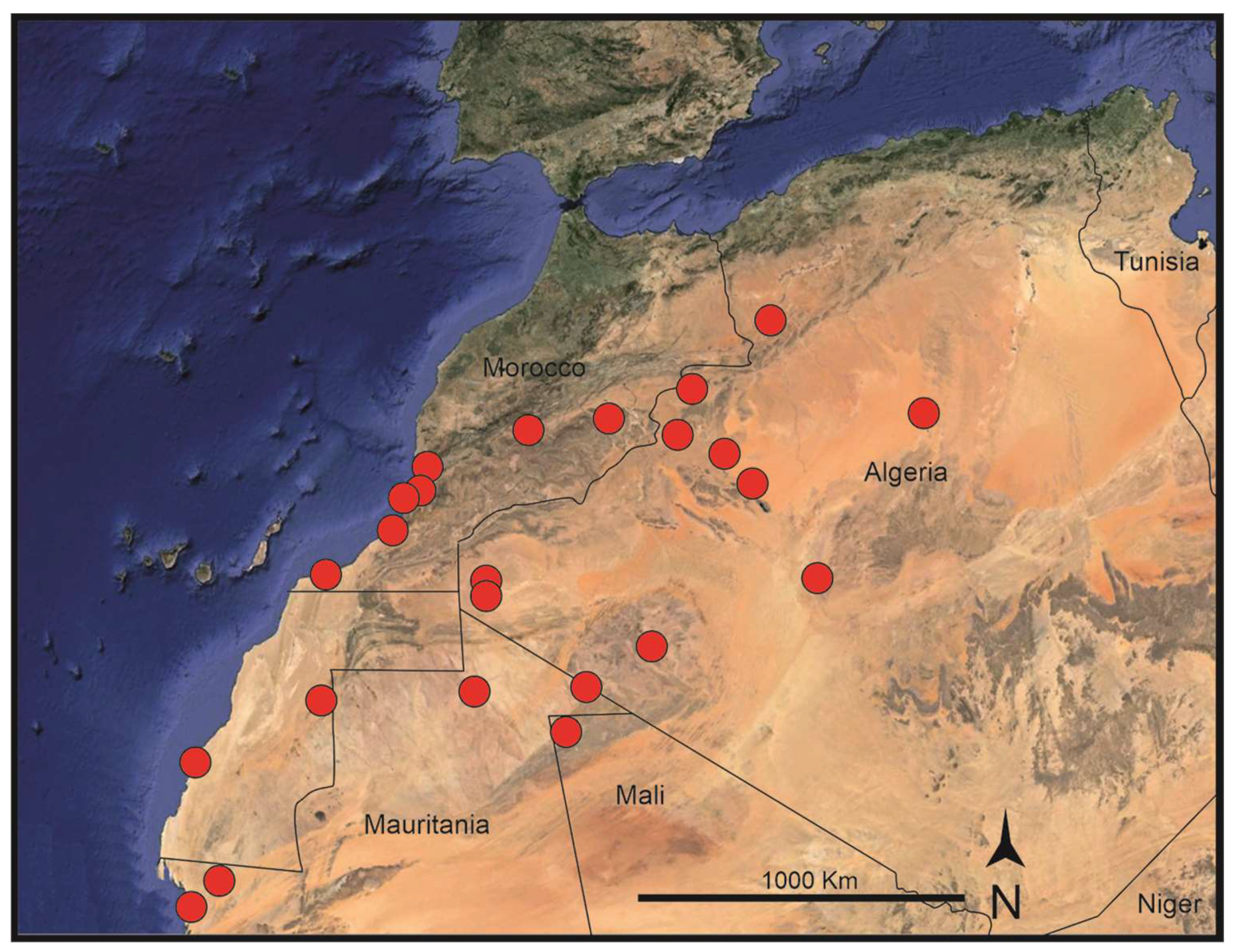

3.1.1. Frankenia sahariensis M.Á.Alonso, M.B.Crespo, Abad-Brotons, Mart.-Azorín & J.L.Villar, nom. nov.

- ≡

- Frankenia florida L.Chevall. in Bull. Herb. Boissier ser. 2, 3(9): 768. 1903 [replaced synonym], nom. illeg. [non Phil. in Anales Univ. Chile 41: 676. 1872] ≡ F. pulverulenta var. florida Maire in Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Afrique N. 27: 210. 1936 ≡ F. pulverulenta subsp. florida (Maire) Maire, Cat. Pl. Maroc 4: 1071. 1941. Type: Algeria. [El Menia Province:] El Goléa [currently, El Menia], in arenosis salsis. April 1902, L. Chevallier 404 (lectotype, designated here: P-06618528!, Figure 1; isolectotypes: P-05145114!, P-06618529!, P-06618525!, MPU-007119!, MPU-007120!, US-00679979 [digital image!], GZU-000269792 [digital image!], JE-00003246, JE-00003247 [digital image!], LY-0084391 [digital image!], WAG-0249595 [digital image!], MO-357730 [digital image!]).

- =

- F. intermedia var. annua Caball. in Trab. Mus. Ci. Nat., Ser. Bot. 30: 30. 1935. Type: Morocco. [Western Sahara]: In collibus arenosis insolatis prope Sidi-Ifni, 13 June 1934, A. Caballero (lectotype, designated here: MA-78660!; isolectotype: MPU-300233!).

- −

- F. pulverulenta subsp. floribunda sensu Quézel & Santa, Nouv. Fl. Algérie: 685. 1963 [sphalm.]. Note: The subspecific epithet, “floribunda”, is most likely a mistaken desinence for “florida”, not a formally proposed name.

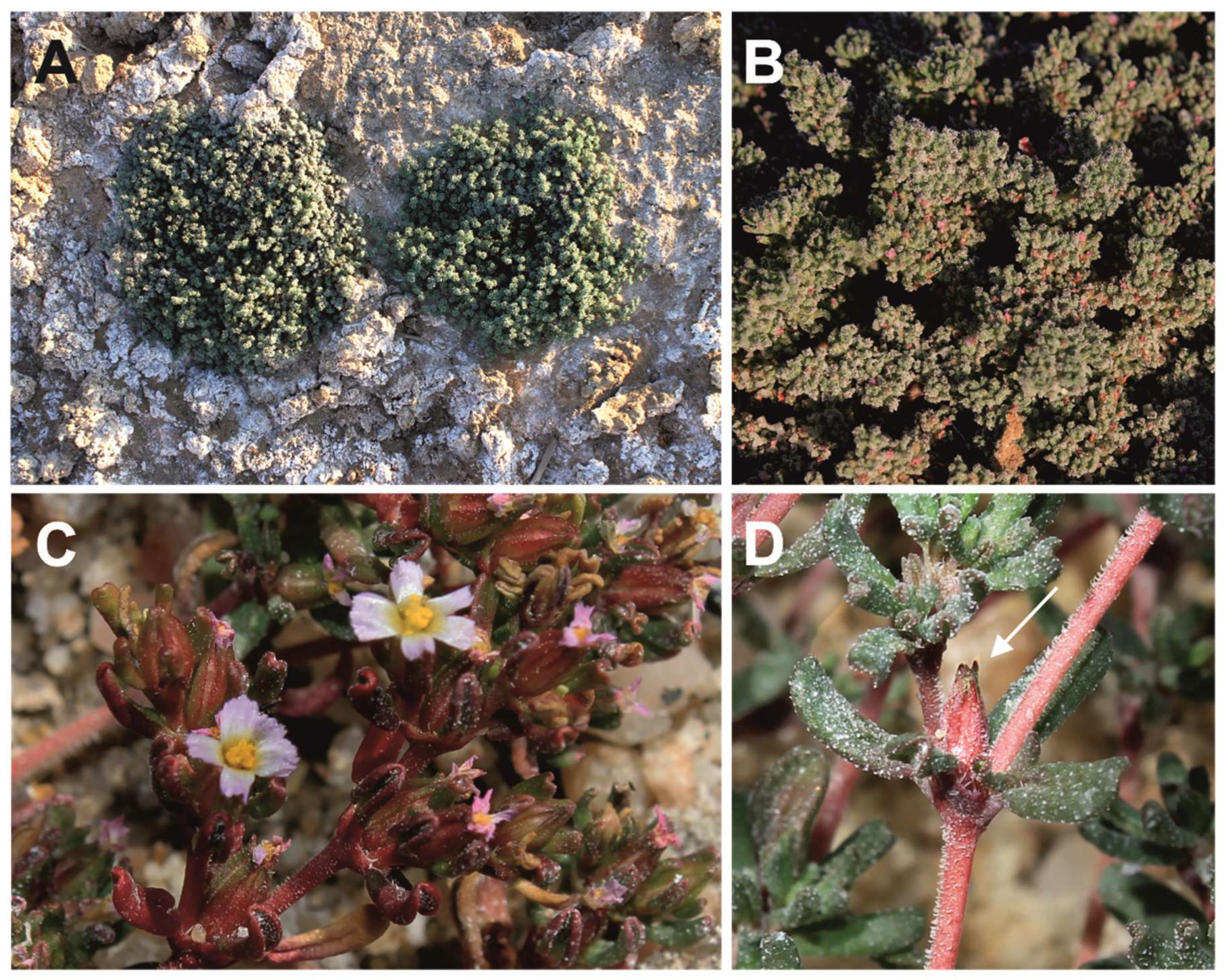

3.1.2. Frankenia dinteri M.Á.Alonso, M.B.Crespo, Abad-Brotons, Mart.-Azorín & J.L.Villar, nom. nov.

- ≡

- Frankenia densa Pohnert in Mitt. Bot. Staatssamml. München 1(9-10): 447. 1954. [replaced synonym], nom. illeg. [non Summerh. in J. Linn. Soc., Bot. 48: 373 (1930)]. Type (see Pohnert 1954: 448): Namibia. [Otjozondjupa Region:] Grootfontein-Süd, 22 November 1934, K. Dinter 8059 (holotype: M-0104483 [digital image!, available at https://plants.jstor.org/stable/viewer/10.5555/al.ap.specimen.m0104483]; isotypes: M-0104484 [digital image!], PRE-0293175-0 [digital image!], PRE-526699-0 [digital image!] HBG-516900 [digital image!], BOL-136934!, K!). Paratypes: Namibia. [Karas Region:] Bethanien [Bethany], 24 December 1934, K. Dinter 8270 (BOL-136934!, HBG-516901 [digital image!], K!). Figure 3.

3.2. Phylogenetic relationships

4. Discussion

- i)

- blade of leaves triangular-ovate to oblong-ovate, with cordate to rounded base and a prominent thickened midrib on the underside of blade in F. sahariensis vs. broadly obovate blade with cuneate base and thin midrib not remarkably prominent in F. pulverulenta;

- ii)

- calyx indument heterogeneous, with flattened trichomes between ribs intermingled with small globose-claviform trichomes and minute papillae in F. sahariensis vs. calyx with homogeneous indument of small curled trichomes also present on the underside of leaves in F. pulverulenta;

- iii)

- petals much exceeding about half to two-thirds the calyx length (vs. petals exceeding only about one-third to half the calyx length in F. pulverulenta); and

- iv)

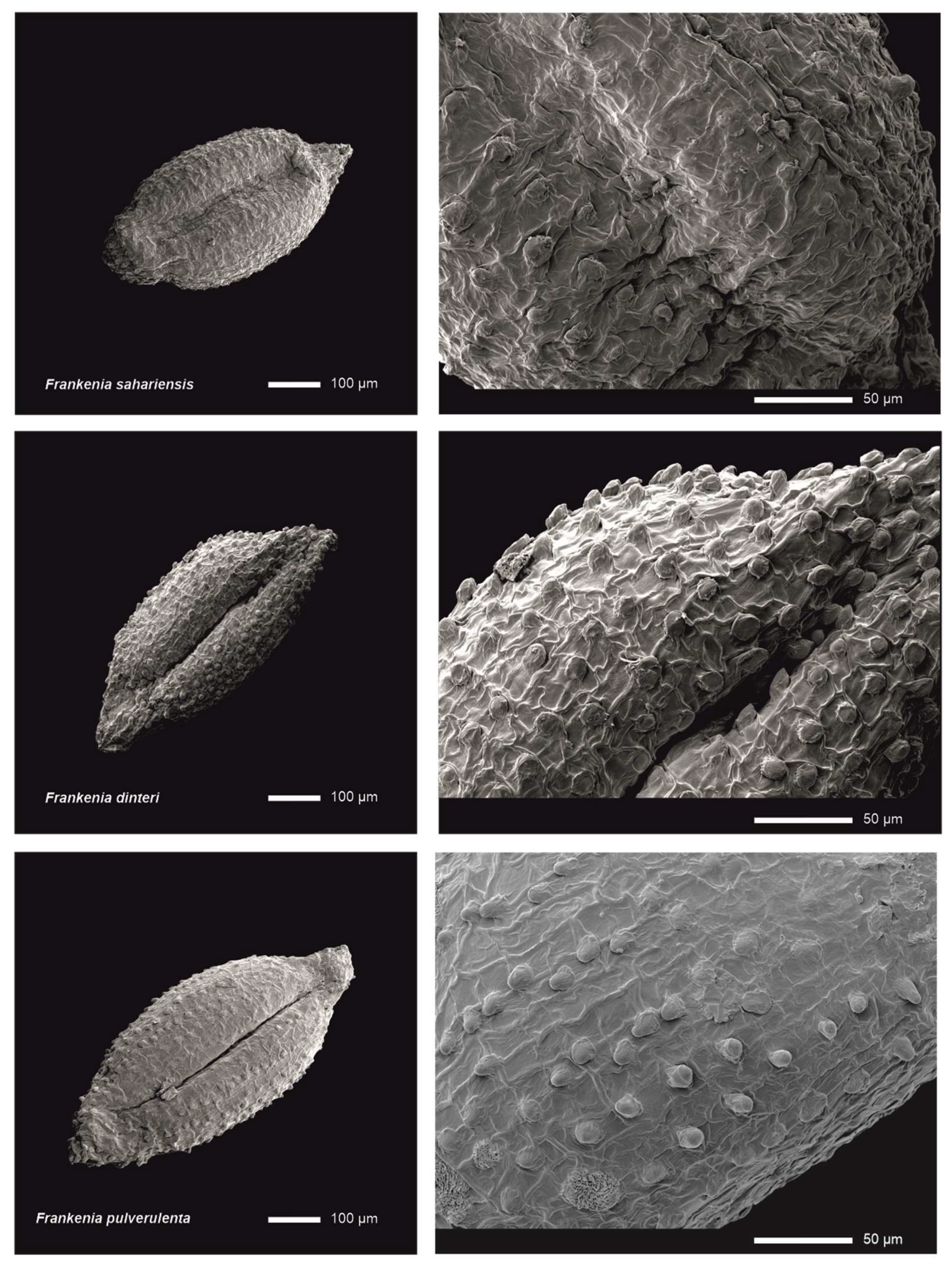

- seeds morphologically close in both species (Figure 7), though less abundant in F. sahariensis (24–30 per capsule) than in F. pulverulenta (up to 45 per capsule).

- i)

- flowers often densely crowded in many-flowered cymes in F. dinteri vs. axillary, solitary or in lax cymes in F. pulverulenta) (Figure 3A,B);

- ii)

- floral bracts about half to two-thirds the calyx length vs. equalling to slightly exceeding the calyx length in F. pulverulenta;

- iii)

- bracteoles 1–2 mm long vs. 2.5–4 mm in F. pulverulenta (Figure 3C,D);

- iv)

- calyx teeth mucro ca. 0.4 mm long vs. ca. 0.1 mm in F. pulverulenta (Figure 3D);

- v)

- anthers 0.6–0.8 mm long vs. 0.2–0.4 mm long;

- vi)

- capsule 3–4.5 mm long vs. 2–3 mm in F. pulverulenta (Table 3); and

- vii)

- seeds morphologically close in both species (Figure 7), though less abundant in F. dinteri (25–30 per capsule) than in F. pulverulenta (up to 45 per capsule).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuénoud, P.; Savolainen, V.; Chatrou, L.W.; Powell, M.; Grayer, R.J.; Chase, M.W. Molecular phylogenetics of Caryophyllales based on nuclear 18S rDNA and plastid rbcL, atpB, and matK DNA sequences. Amer. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.E.; Gaskin, J.F.; Ghahremani-Nejad, F. Stem anatomy is congruent with molecular phylogenies placing Hypericopsis persica in Frankenia (Frankeniaceae): comments on vasicentric tracheids. Taxon 2003, 52, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J.F.; Ghahremani-Nejad, F.; Zhang, D.-Y.; Londo, J.P. A systematic overview of Frankeniaceae and Tamaricaceae from nuclear rDNA and plastid sequence data. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 2004, 91, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online (continuously updated). Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Summerhayes, V.S. A revision of the Australian species of Frankenia. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1930, 48, 337–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H.; Brummitt, R.K.; Culham, A.; Seberg, O. Flowering plant families of the world; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2007; pp. 150–151. [Google Scholar]

- Niedenzu, F. Frankeniaceae. In Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2nd ed.; Engler, H.G., Prantl, K.A., Eds.; W. Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1925; Volume 21, pp. 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K. Frankeniaceae. In The families and genera of vascular plants 5. Malvales, Capparales and non-betalain Caryophyllales; Kubitzki, K., Bayer, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mucina, L.; Bültmann, H.; Dierßen, K.; Theurillat, J.-P.; Raus, T.; et al. Vegetation of Europe: hierarchical floristic classification system of vascular plant, bryophyte, lichen, and algal communities. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2016, 19 (Suppl. 1), 3–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, E.J. Die Verbreitung von Frankenia in der Mongolei, in Westeurasien und im Weltmaβstab. Flora (Jena) 1992, 186, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.C.; Helme, N.A. Frankenia fruticosa (Frankeniaceae), a new dwarf shrub from the Knersvlakte, Western Cape. S. African J. Bot. 2014, 91, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.B.; Alonso, M.Á.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Villar, J.L.; Mucina, L. What is wrong with Frankenia nodiflora Lam. (Frankeniaceae)? New insights into the South African sea-heaths. Plants 2023, 12, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. Frankenia. In Flora Iberica, 3. Plumbaginaceae (Partim)-Capparaceae; Castroviejo, S., Aedo, C., Cirujano, S., Laínz, M., Montserrat, P., Morales, R., Muñoz Garmendia, F., Navarro, C., Paiva, J., Soriano, I., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico-CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1993; Volume 3, pp. 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen, M.A. Frankeniaceae. In Flora of North America north of Mexico, 6. Magnoliophyta: Cucurbitaceae to Droseraceae; Flora of North America Editorial Committee, Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2015; Volume 6, pp. 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Grigore, M.N.; Toma, C. Salt Secretion. In Anatomical Adaptations of Halophytes: A Review of Classic Literature and Recent Findings; Grigore, M.N., Toma, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 147–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Cuadra, V.; Verolo, M.; Cambi, V. Morphological and anatomical traits of halophytes. Adaptive versus phylogenetic value. In Handbook of Halophytes. From Molecules to Ecosystems towards biosaline agriculture; Grigore, M.N., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, M.A. Systematics of Frankenia (Frankeniaceae) in North and South America. Syst. Bot. Monogr. 1987, 17, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkova, S.G. Frankenia L. In Flora of the USSR; Shishkin, B.K., Ed.; Komarov Botanical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Moscow-Leningrad, Russia, 1949; Volume 15, pp. 271–275. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chater, A.O. Frankenia L. In Flora europaea; Tutin, T.G., Heywood, V.H., Burges, N.A., Moore, D.M., Valentine, D.H., Walters, S.M., Webb, D.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968; Volume 2, pp. 294–295. [Google Scholar]

- Chrtek, J. Frankeniaceae. In Flora iranica; Rechinger, K.H., Ed.; Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt: Graz, Austria, 1972; Fascicle 99; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lomonosova, M.N. A new species of the genus Frankenia (Frankeniaceae) from Tuva ASSR. Bot. Zhurn. (Moscow & Leningrad) 1984, 99, 548–549. [Google Scholar]

- Nègre, R. Les Frankenia du Maroc. Trav. Inst. Sci. Chérifien, Sér. Bot. 1957, 12, 5–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jahandiez, E.; Maire, R. Catalogue des Plantes du Maroc (Spermatophytes et Ptéridophytes); Imprimerie Minerva: Alger, Algeria, 1932; Volume 2, 557p. [Google Scholar]

- Emberger, L.; Maire, R. Catalogue des Plantes du Maroc (Spermatophytes et Ptéridophytes), Supplément aux volumes I, II et III; Imprimerie Minerva: Alger, Algeria, 1941; Volume 4, 1181p. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.-H.; Li, D.-Z.; Marhold, K.; May, T.W.; McNeill, J.; Monro, A.M.; Prado, J.; Price, M.J.; Smith G.F., Eds.; International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017. − Koeltz Scientific Books: Königstein, Germany, 2018; [Regnum Veg. 159]. [CrossRef]

- EURO+MED. Euro+Med PlantBase – The information resource for Euro-Mediterranean plant diversity (continuously updated). Available online: http://www.europlusmed.org (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: a global directory of public herbaria and associated staff (continuously updated). Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Rasband, W.S. ImageJ. U.S. National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Available online: https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- IPNI. The International Plant Names Index (continuously updated). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries, and Australian National Herbarium. Available online: http://www.ipni.org (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Leistner, O.A.; Morris, J.W. Southern African place names. Ann. Cape Prov. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1976, 12, 1–565. [Google Scholar]

- National Geospatial Information. SA Mapsheet Referencing. Available online: http://www.ngi.gov.za/indexphp/what-we-do/maps-and-geospatial-information/41-sa-mapsheet-referencing (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Mucina, L.; Rutherford, M.C., Eds. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. [Strelitzia 19].

- Quézel, P. Analysis of the flora of Mediterranean and Saharan Africa. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1978, 65, 479–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhtajan, A. Floristic regions of the world; University of California Press: London, UK, 1986; 522p. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C.S.; Ayres, K.L.; Toomey, N.; Hayder, N.; et al. Selection of candidate coding DNA barcoding regions for use on land plants. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2009, 159, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbour-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1874, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Method. 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G + C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992, 9, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Hohna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.L.; Alonso, M.Á.; Juan, A.; Gaskin, J.; Crespo, M.B. Out of the Middle East: new phylogenetic insights in the genus Tamarix (Tamaricaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2019, 57, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meimberg, M.; Dittrich, P.; Bringmann, G.; Schlauer, J.; Heubl, G. Molecular phylogeny of Caryophyllidae s.l. based on matK sequences with special emphasis on carnivorous taxa. Plant Biol. (Stuttgart) 2000, 2, 218–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Meng, H.-H.; Zhang, H.-X.; Vyacheslav, B.V.; Sanderson, S.C. Himalayan origin and evolution of Myricaria (Tamaricaeae) in the Neogene. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.D.; Yang, T.; Lin, L.; Lu, L.M.; et al. Tree of life for the genera of Chinese vascular plants. J. Syst. Evol. 2016, 4, 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Hao, X.-L.; Sanderson, S.C.; Vyacheslav, B.V.; Sukhorukov, A.P.; Zhang, H.-X. Spatiotemporal evolution of Reaumuria (Tamaricaceae) in Central Asia: insights from molecular biogeography. Phytotaxa 2014, 167, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Li, T.; Yan, H.F.; Feng, Y.; Jin, L.; Burgess, K.S.; Ge, X.J. Plant DNA barcode library for native flowering plants in the arid region of northwestern China. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2023, 23, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozenda, P. Flora of the Sahara, 2nd ed.; CNRS: Paris, France, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier, L. Deuxième note sur la Flore du Sahara (suite et fin). Bull. Herb. Boissier, sér. 2 1903, 3, 757–779. [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, R.A. Descripción de las plantas nuevas incorporadas últimamente en el herbario chileno. Anales Univ. Chile 1872, 41, 663–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maire, R. Contribution à l’étude de la Flore de l’Afrique du Nord, Fascicule 24. Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Afrique Nord 1936, 27, 203–238. [Google Scholar]

- WFO. World Flora Online (continuously updated). Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Pohnert, H. Neuen Arten aus Südwest-Afrika. Frankenia densa Pohnert. Mitt. Bot. Staatssamml. München 1954, 9–10, 447–448. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/15187743.

- Rivas Martínez, S.; Díaz, T.E.; Fernández González, F.; Izco, J.; Loidi, J.; Lousã, M.; Penas, Á. Vascular plant communities of Spain and Portugal: Addenda to the syntaxonomical checklist of 2001. Part II. Itinera Geobot. 2002, 15, 433–922. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer, A.A. Frankeniaceae. Flora of southern Africa; Ross, J.H, Ed.; Botanical Research Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 1976; Volume 22, pp. 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, A. Datos botánicos del territorio de Ifni (2.ª parte). Trab. Mus. Nac. Ci. Nat., Ser. Bot. 1935, 30, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Candolle, A.P. de. Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis. Treuttel et Würtz: Paris, France, 1824; Volume 1, pp. 349–350. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/153953.

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J.C. Cape Plants: A conspectus of the Cape Flora of South Africa. [Strelitzia 9]; National Botanical Institute: Cape Town, South Africa; Missouri Botanical Garden: St Louis, MO, USA, 2000; 743p. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo, D.; von Staden, L.; Foden, W.; Victor, J.E.; Helme, N.A.; Turner, R.C.; Kamundi, D.A.; Manyama, P.A. (Eds.) Red List of South African Plants. [Strelitzia 25]; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, R.T. Novitiae Florae Maderensis: or Notes and Gleanings of Maderan Botany. Trans. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 1838, 6, 523–551. [Google Scholar]

| Taxon | Locality | Herbarium voucher |

| F. sahariensis | Mauritania: Iouik | P-05038748 |

| F. dinteri | South Africa: Klipfontein | ABH-76891 |

| F. pulverulenta | Spain: Alicante, Orxeta | ABH-7952 |

| F. saharienis | F. dinteri | F. pulverulenta | |

| General habit | Annual or perennial herbaceous and weakly lignified at base | Annual or perennial herbaceous and weakly lignified at base | Annual or rarely short-lived perennial |

| Stem features | Prostrate to decumbent, non-rooting | Erect to ascendant, non-rooting | Prostrate to ascending, non-rooting |

| Branchlet indumentum | ± densely puberulous on one side and near nodes | ± densely pubescent on one side | ± densely pubescent on one side |

| Branch trichomes: types and length (mm) | minute, ca. 0.1–0.2, curled or hooked | minute, ca. 0.1–0.2, curled or hooked | minute, ca. 0.1–0.2, curled |

| Petiole length × width (mm) | 0.5−0.8 × 0.2−0.3, | 0.8−1.2 × 0.5−0.6 | 0.5–1.5× 0.2–0.3 |

| Petiole sheath | (2−)4−5 pairs of cilia | 4−6 pairs of cilia | 2–6 pairs of cilia |

| Sheath cilia length (mm) and colour | 0.2−0.5 mm, unequal, whitish | 0.4−0.5 mm, unequal, whitish | 0.3–0.6, unequal, whitish |

| Leaf blade length × width (mm) | (1.8−)2.5−4 × 0.5−0.7 | (2.5−)3−4.5 (6) × 0.5−2 | 2–5 × 1.5–3 |

| Leaf blade outline and colour | Triangular-ovate to oblong-ovate, ± concolorous, midrib notably thickened | Elliptic to oblong, ± concolorous, midrib narrow, not thickened | Obovate-cuneate, ± concolorous, midrib narrow, not thickened |

| Leaf blade shape and margins | Obtuse apex and cordate to rounded base; often strongly revolute on margins or flattened in the lower third | Obtuse apex and rounded base; often strongly revolute on margins or flattened in the lower third | Rounded, slightly emarginate apex and cuneate base; flattened or slightly revolute on margins |

| Leaf blade indumentum | Glabrous on the upper side, glabrous to loosely hairy beneath with scattered short straight trichomes 0.1–0.2 mm long | Glabrous on the upper side, and glabrous to loosely hairy beneath with scattered short straight trichomes 0.1–0.2 mm long | Glabrous on the upper side, ± densely pubescent beneath with scattered short straight trichomes 0.1–0.2 mm long |

| Inflorescence | Flowers often in axillary or terminal dichasial groups, usually condensed and glomerular | Flowers in dense axillary or terminal dichasial groups, usually densely condensed and glomerular | Flowers solitary and scattered along branch dichotomies in loose groups |

| Bracteole length × width (mm) | 0.5–1.5 × 0.4–0.6, about half the calyx length | 1–2 × 0.4–1 mm, about half the calyx length | 2.5–4, as long as or longer than calyx |

| Calyx length × width (mm), shape and torsion | 2–4 × 0.6–1, fusiform-tubular to fusiform, often twisted | 3–4.7 × 0.6−1, fusiform-tubular to fusiform, non-twisted | 2.5–4(–5) × 0.8–1.5, fusiform-tubular to fusiform, non-twisted |

| Calyx indument (appearance and length) | Entirely glabrous or densely papillate between the glabrous ribs, with heterogeneous trichomes (flattened papillae 0.2–0.3 mm, globose-claviform papillae ca. 0.1 mm, and minute globose vesicles) | Entirely glabrous or puberulous between the glabrous ribs, with homogeneous papillae ca. 0.1 mm long | Entirely glabrous or puberulous between the glabrous ribs, with homogeneous papillae up to 0.2 mm |

| Calyx teeth length (mm) and shape | 0.5–1, acute, mucronate (mucro ca. 0.1–0.2 mm), cucullate | ca. 0.5, acute, long mucronate (mucro ca. 0.4 mm), cucullate. | 0.4–0.8, acute to mucronate (mucro ca. 0.1 mm), cucullate |

| Petal size (mm) and balde colour | 5–6 × 1–1.5, pinkish-mauve but whitish below | 4–4.5 × 0.5–0.8 pinkish-mauve but whitish below | 3.5–5 × 0.6–0.9, whitish-pink to pinkish-mauve, whitish below |

| Petal blade size (mm), and shape | 2.3–3.5 × 1–1.5, obovate-cuneate, rounded and erose-denticulate at apex | 2–2.5 × 0.5–0.8, obovate, rounded to truncate and irregularly erose-denticulate at apex | 2–2.5 × 0.5–0.8, narrowly cuneate to obovate, truncate and erose-denticulate at apex |

| Petal claw (mm) | 2–2.5 × 0.3–0.4, narrowly cuneate | 2–2.5 × 0.3–0.4, narrowly cuneate | 2–2.5 × 0.3–0.5, cuneate |

| Petal ligule (mm) | 2–2.5 × 0.3–0.4 mm,free apex ca. 0.2–0.4 × 0.2–0.3 mm, ovate- ovate-oblong, obtuse to subacute, entire | 2–2.5 × 0.4–0.5, free apex ca. 1 × 0.5 mm, ovate-oblong, obtuse to subacute, entire | 1–2 × 0.2–0.3, free apex ca. 0.4 mm, triangular, acute, entire |

| Stamen filament length (mm) and morphology | 3.5–5.5, expanded ca. 0.5 mm in the lower part, but tapering and filiform in the distal part | 2.3–2.5, expanded ca. 0.5 mm in the lower half, but tapering and filiform in the distal part | 4–6, expanded ca. 0.2 mm in the lower half, but tapering and filiform in the distal part |

| Anther length (mm), shape and colour | 0.6–0.8, ellipsoid, yellowish | 0.6−0.8, ellipsoid, yellowish | 0.2–0.4, oblong–ellipsoid, yellowish |

| Ovules per placenta | 9–12 | 10–12 | 12–20 |

| Capsule size (mm) | 1.4–2 × 0.8–1 | 3–4.5 × 1.4–2 | 2–3 × 0.5–1 |

| Seed number and size (mm) | 24–30, 0.4–0.5 × 0.2–0.25 |

25–30, 0.5−0.6 × 0.2–0.3 |

up to 45, 0.5–0.7 × 0.2–0.3 |

| Testa papillae length (µm) | 10–14 | 7–12 | 4–17 |

| Papillae morphology and distribution | Homogeneous, globose to conical-obtuse, denser on distal part | Homogeneous, conical-obtuse, denser on distal part | Homogeneous, conical-obtuse, denser on distal part |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).