Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data and Study Area

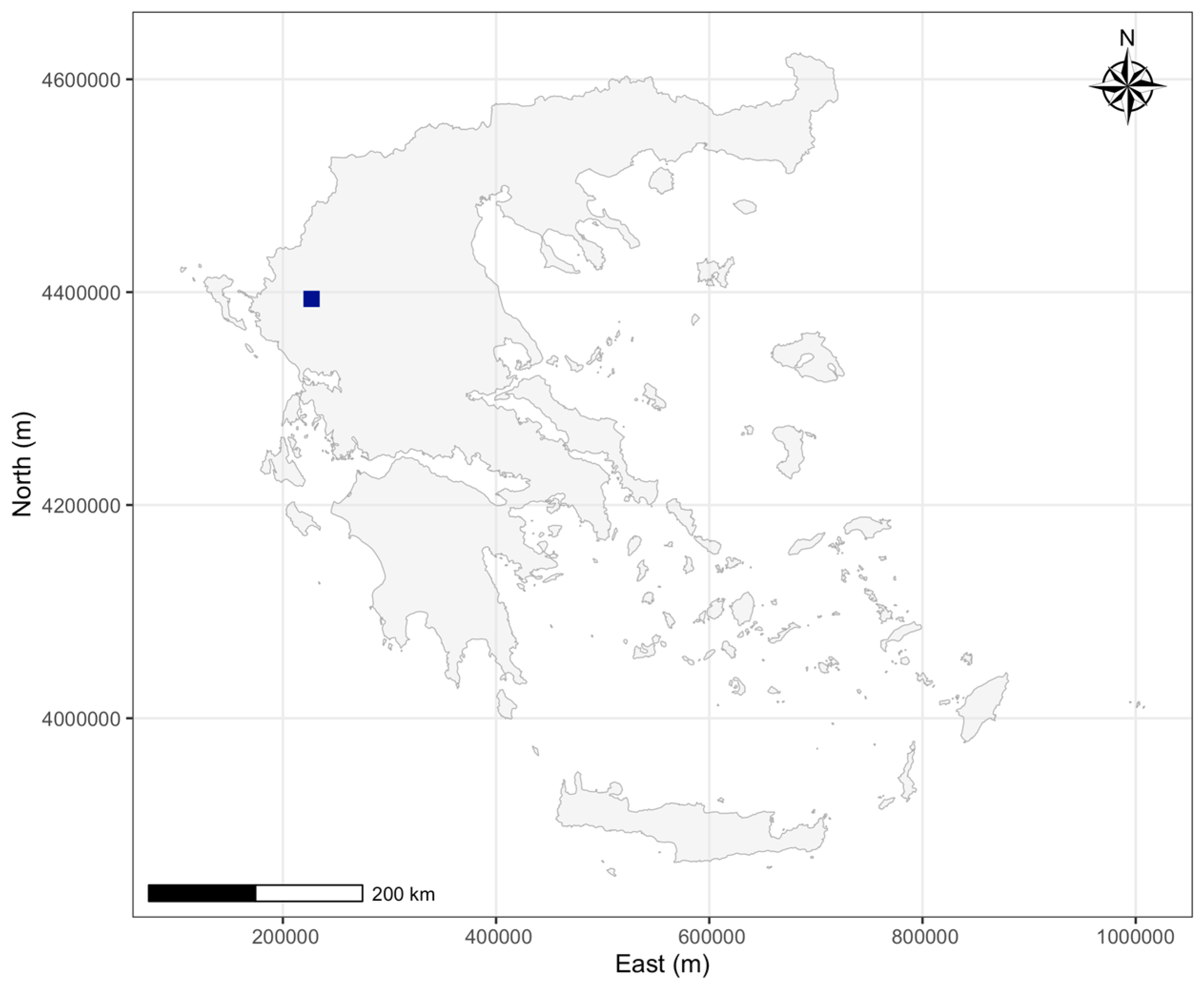

2.2. Data Sources

- Land Survey Study Data: Higher-accuracy data were obtained from the digital land surveying study that was conducted by the Municipality of Ioannina in 2001 at a scale of 1:500. The survey was referenced to the Greek western zone of the Transverse Mercator (TM3 western zone) [39]. The purpose of this survey was to be the base map for the Implementing Act.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Clustering Algorithms

2.4.1. Fuzzy c-Means

2.4.2. Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise

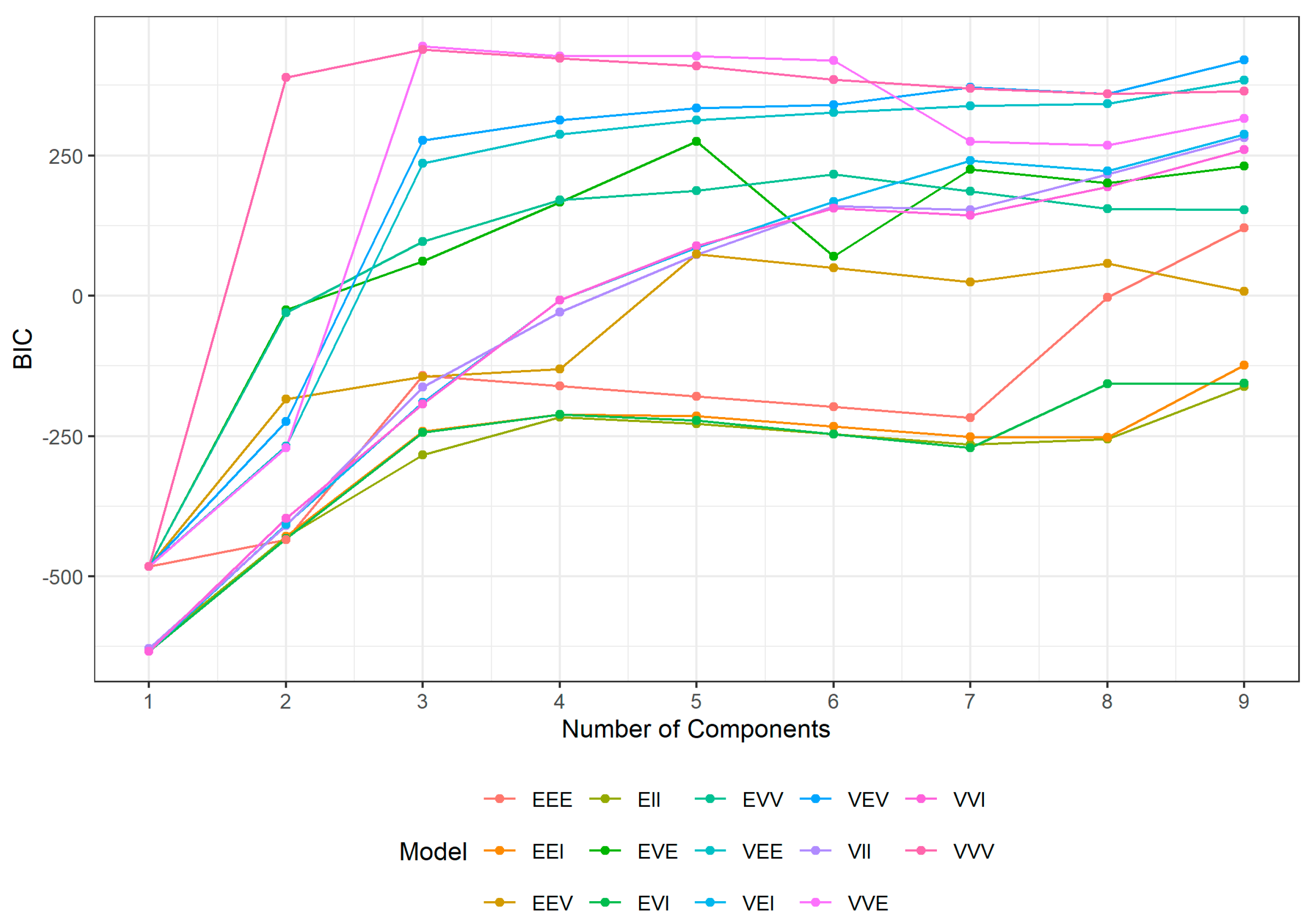

2.4.3. Gaussian Mixture Models

- Expectation (E-step): Calculates the posterior probability of each component for each data point, given the current parameter estimates. This represents the probability that a data point belongs to a particular Gaussian component;

- Maximization (M-step): Updates the parameters

2.3.5. Selection of the Algorithms

2.3.6. Evaluation and Clustering Validity

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Analysis

- Mean Error: The mean is close to zero (0.03 m), while the mean Δ is considerably larger and negative (-0.50 m). This indicates a systematic shift in the Northing direction between the 2025 and the 2001 data;

- Symmetry: The near-zero skewness values for both and Δ suggest that the error distributions are approximately symmetric, although Δ has a slight positive skew;

- Tails: The negative kurtosis for ΔE indicates a platykurtic distribution that has lighter tails and a flatter peak compared to a normal distribution, whereas the positive value for ΔN is a leptokurtic distribution with heavier tails and sharper peak;

- Variability: The CV for (10.67) is substantially larger than that for ΔNorth (0.66), indicating greater relative variability in the Easting errors compared to the Northing errors;

- Skewness: Near-zero values suggest approximately symmetric distributions;

- Kurtosis: Low values indicate light tails, consistent with normal-like distributions;

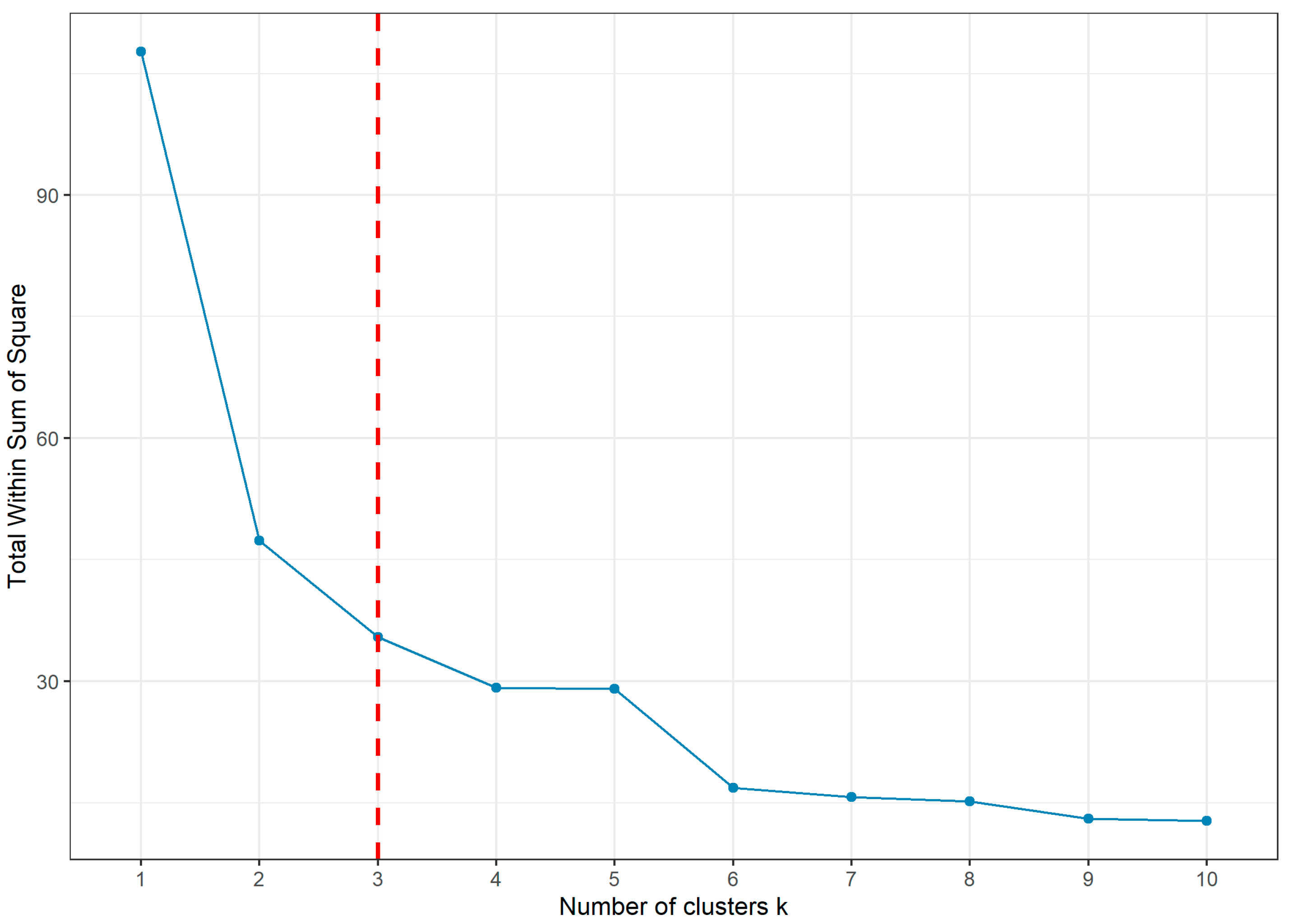

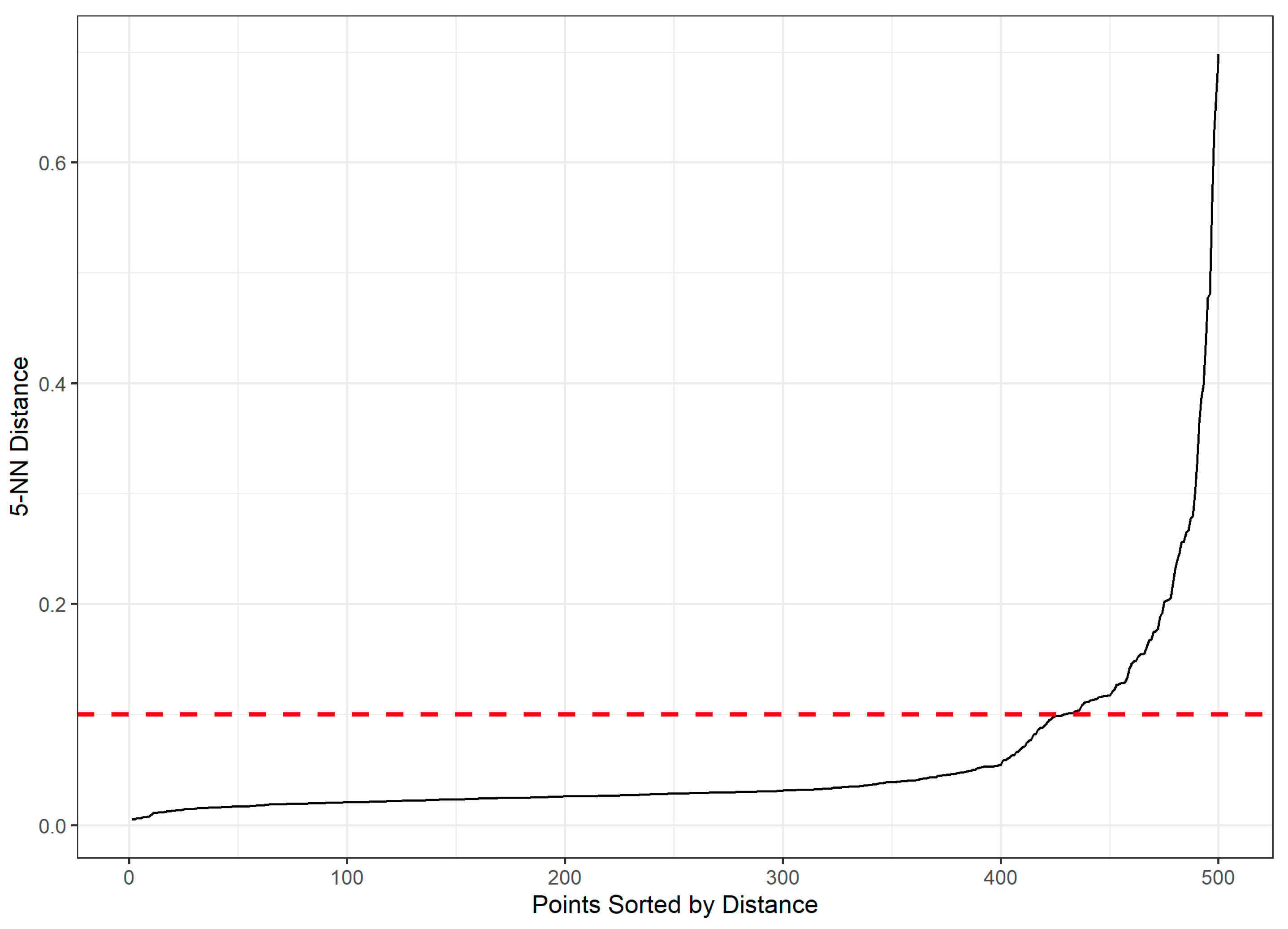

3.2. Optimal Number of Clusters

- FCM: The elbow method was used, examining the WSS value as a function of the number of clusters (Figure 4). A distinct ‘elbow’ is observed between 2 and 4 clusters, and the mean value of 3 was selected.

- DBSCAN: The 5-nearest neighbor distance plot (Figure 5) was examined. A visible ‘knee’ is observed around a distance of 0.10. Therefore, an ε value of 0.10 was selected. Additionally, a value of 10 points was chosen, as it appeared suitable for capturing meaningful cluster structures within the dataset.

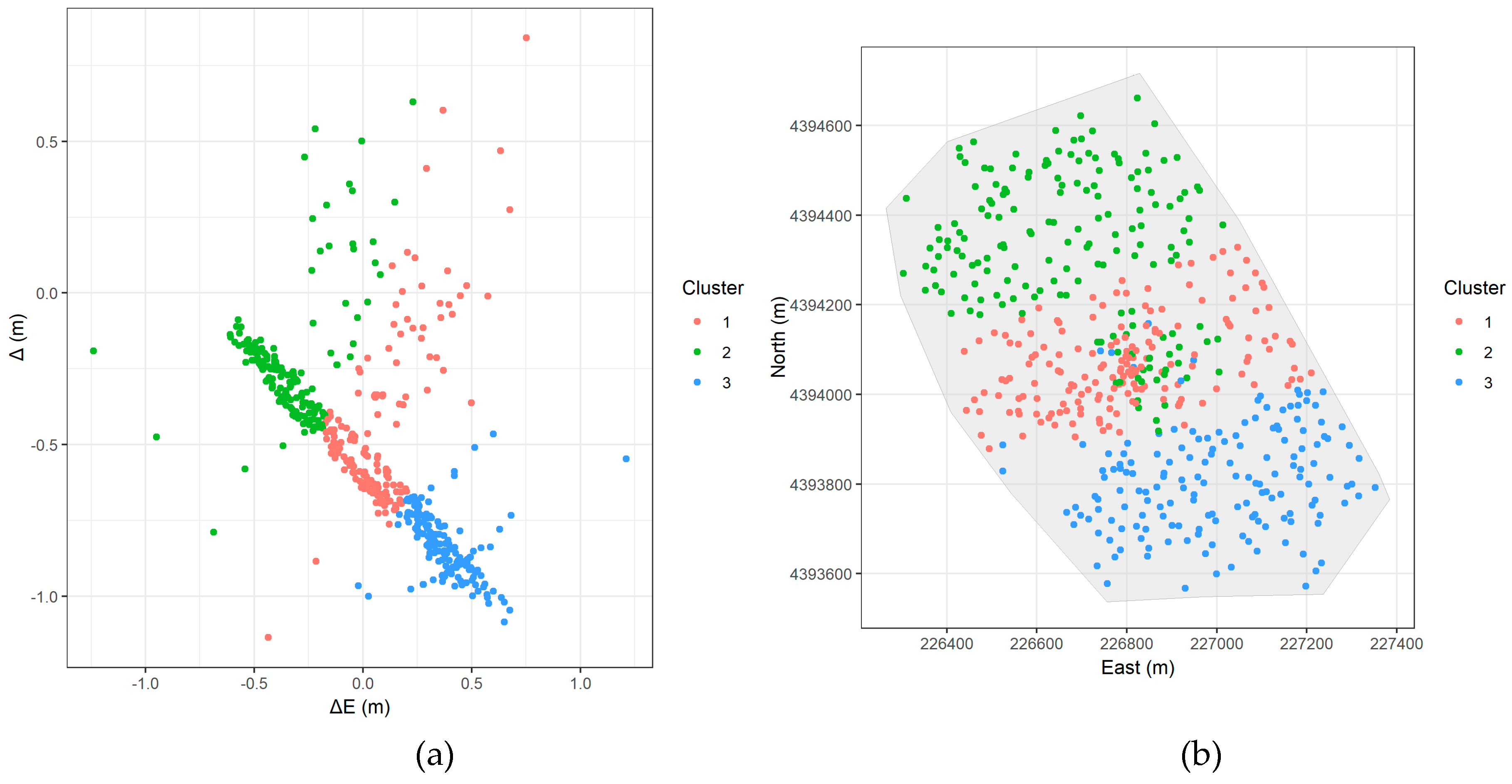

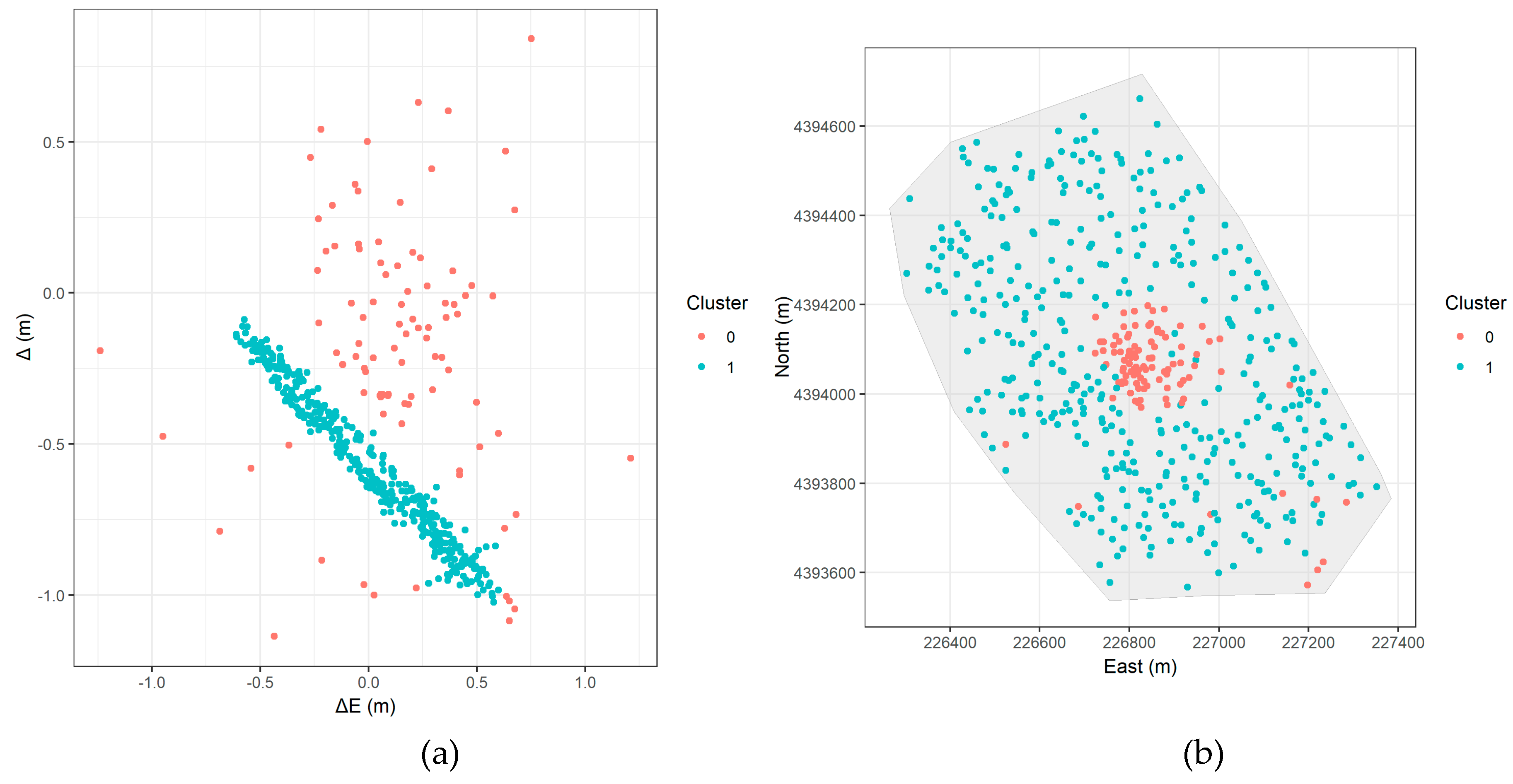

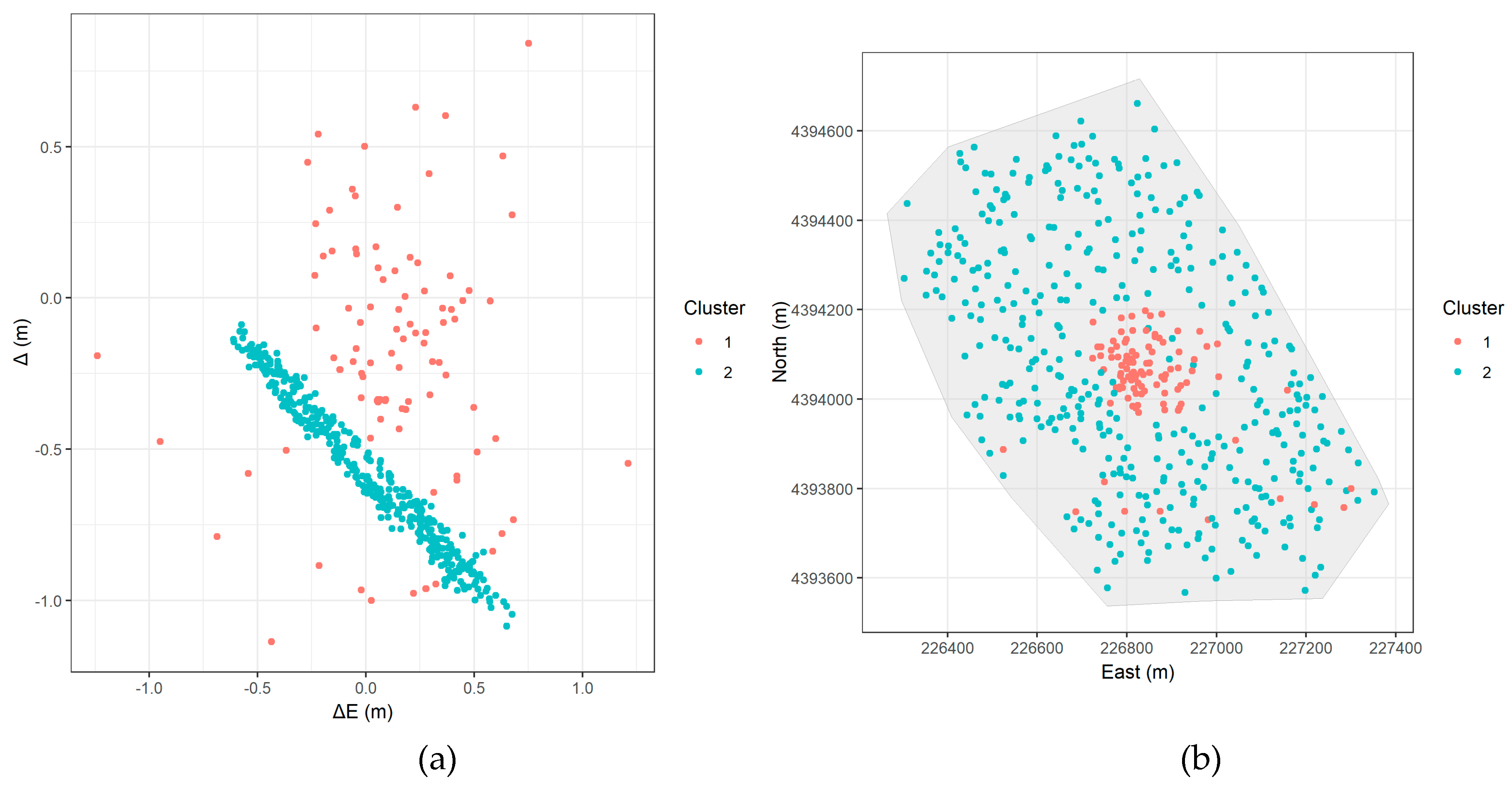

3.2. Clustering Results - Visualizations

- FCM (Figure 7a): Three relatively well-separated clusters are formed. However, they don’t capture the obvious linear pattern in the error space.

- DBSCAN (Figure 8a): The clear linear cluster (blue points) is identified as well as a large number of noise points (red points). The linear cluster matches the suspected systematic error.

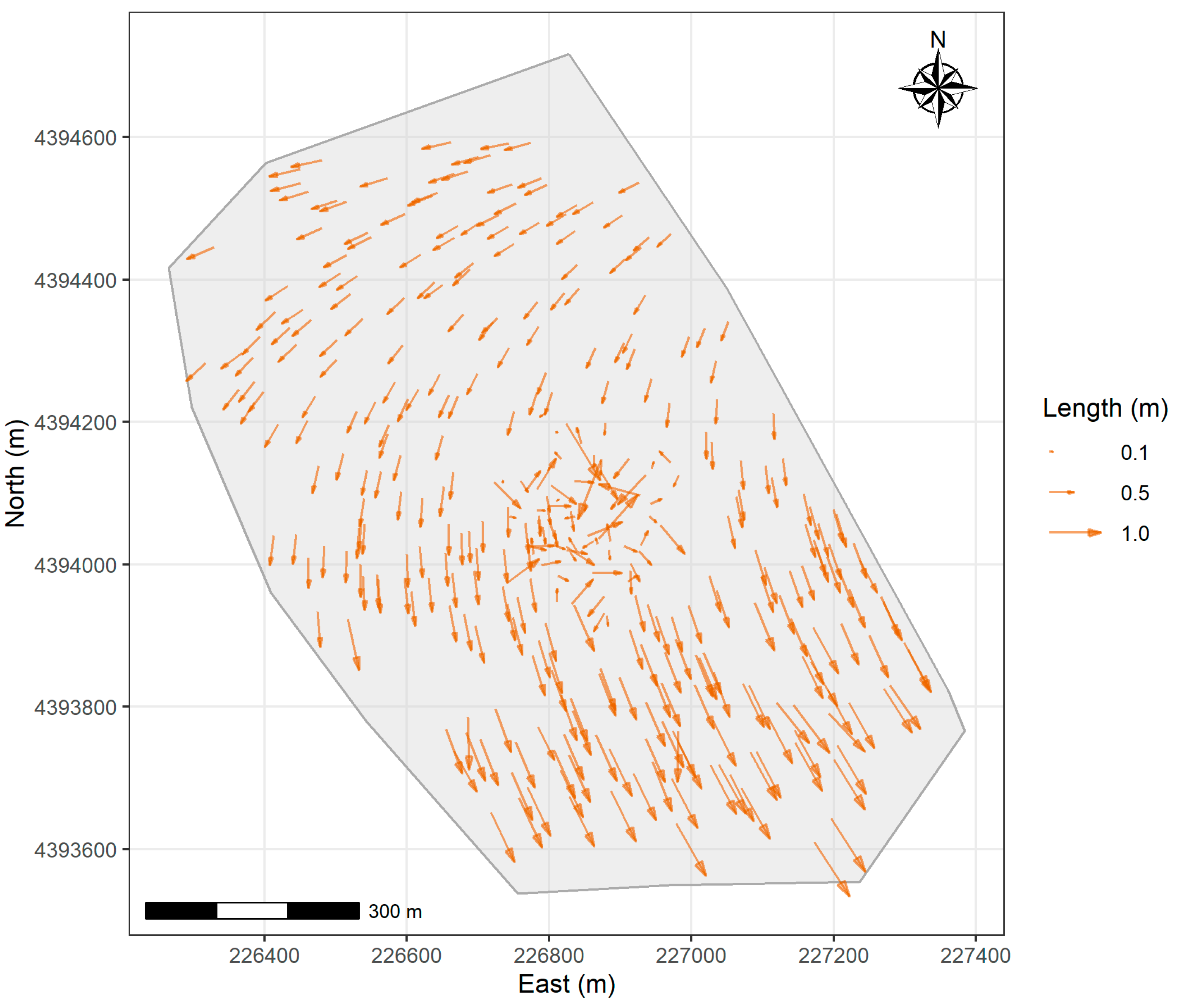

- Regarding the spatial distribution plots for each clustering algorithm:

- DBSCAN (Figure 8b): The blue points (the linear cluster) form a distinct, spatially contiguous region covering the majority of the study area, matching the area where we observed the ring-like, counter-clockwise rotational error pattern in Figure 3. The red noise points are concentrated in the central area.

- GMM (Figure 9b): The spatial distribution is very similar to DBSCAN, with the blue points forming a contiguous region corresponding to the rotational error. Most of the ‘noise’ points from DBSCAN now form the red cluster, making the distinction of signal to noise less clear.

3.3. Quantitative Evaluation—Silhouette Scores

3.3. Cluster Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| EM | Expectation Maximization |

| FCM | Fuzzy c-means |

| FFPLA | Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration |

| FIG | International Federation of Surveyors |

| GCN | Greek National Cadastre |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| HGRS87 | Hellenic Geodetic Reference System 1987 |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbor |

| LAS | Land Administration Systems |

| Probability Density Function | |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TKMP | Turkish Land Registry and Cadastre Modernization Project |

| TM | Transverse Mercator |

| WSS | Within-cluster Sum of Squares |

References

- Movahhed Moghaddam, S.; Azadi, H.; Sklenička, P.; Janečková, K. Impacts of Land Tenure Security on the Conversion of Agricultural Land to Urban Use. Land Degradation & Development 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bydłosz, J. The Application of the Land Administration Domain Model in Building a Country Profile for the Polish Cadastre. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uşak, B.; Çağdaş, V.; Kara, A. Current Cadastral Trends—A Literature Review of the Last Decade. Land 2024, 13, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzarova, L.A.; Aguzarova, F.S. On the Issue of Cadastral Value and Its Impact on Property Taxation in the Russian Federation. In Business 4.0 as a Subject of the Digital Economy; Popkova, E.G., Ed.; Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-90323-7. [Google Scholar]

- El Ayachi, M.; Semlali, E.H. Digital Cadastral Map, a Multipurpose Tool for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the International conference on spatial information for sustainable development, Nairobi; 2001; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jahani Chehrehbargh, F.; Rajabifard, A.; Atazadeh, B.; Steudler, D. Current Challenges and Strategic Directions for Land Administration System Modernisation in Indonesia. Journal of Spatial Science 2024, 69, 1097–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.M.; Omar, A.H.; Ramli, S.N.M.; Omar, K.M.; Din, N. Cadastral Database Positional Accuracy Improvement. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-4/W5, 91–96. [CrossRef]

- Ercan, O. Evolution of the Cadastre Renewal Understanding in Türkiye: A Fit-for-Purpose Renewal Model Proposal. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysel’, P.; Hudecová, L. Testing of a New Way of Cadastral Maps Renewal in Slovakia. 2022.

- Lauhkonen, H. Cadastral Renewal in Finland-The Challenges of Implementing LIS. GIM international 2007, 21, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Roić, M.; Križanović, J.; Pivac, D. An Approach to Resolve Inconsistencies of Data in the Cadastre. Land 2021, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.J. A Model for the Creation and Progressive Improvement of a Digital Cadastral Data Base. Land use policy 2015, 49, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.M.; Unger, E.-M.; Lemmen, C.; Dijkstra, P. Land Administration Maintenance: A Review of the Persistent Problem and Emerging Fit-for-Purpose Solutions. Land 2021, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, D.; Prell, K.M.; Riemer, H.G. Digitisation and Geometrical Improvement of Inhomogeneous Cadastral Maps. Survey Review 1989, 30, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamim, N.S. A Methodology to Create a Digital Cadastral Overlay through Upgrading Digitized Cadastral Data, The Ohio State University: Ohio, USA, 1992.

- Tuno, N.; Mulahusić, A.; Kogoj, D. Improving the Positional Accuracy of Digital Cadastral Maps through Optimal Geometric Transformation. Journal of surveying engineering 2017, 143, 05017002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeh, M.; Gielsdorf, F.; Trobec, B.; Krivic, M.; Lisec, A. Improving the Positional Accuracy of Traditional Cadastral Index Maps with Membrane Adjustment in Slovenia. ISPRS international journal of geo-information 2019, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, J.; Florijn, W.; Hoekstra, M.; Hagemans, E. Rebuilding the Cadastral Map of The Netherlands, the Artificial Intelligence Solution. In Proceedings of the FIG working week; Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petitpierre, R.; Guhennec, P. Effective Annotation for the Automatic Vectorization of Cadastral Maps. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 2023, 38, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Friedman, J.; Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer Series in Statistics; Second Edition. Springer New York: New York, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4899-0519-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Chahal, P. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Algorithms. In Challenges and applications for implementing machine learning in computer vision; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2020; pp. 188–219.

- Hartigan, J.A. Clustering Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons Inc: NY, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-471-35645-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Duin, R.P.W.; Mao, J. Statistical Pattern Recognition: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2000, 22, 4–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, G.J.; Thopil, G.A. Data Clustering: Application and Trends. Artif Intell Rev 2023, 56, 6439–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Tong, H. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques; Morgan kaufmann, 2022.

- Grubesic, T.H.; Wei, R.; Murray, A.T. Spatial Clustering Overview and Comparison: Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Computational Expense. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 2014, 104, 1134–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, C.; Wang, J.; Gao, P. A Raster-Based Spatial Clustering Method with Robustness to Spatial Outliers. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 4103. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Shekhar, S.; Li, Y. Statistically-Robust Clustering Techniques for Mapping Spatial Hotspots: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantas, K.; Sidiropoulos, E.; Loukas, A. Robustness Spatiotemporal Clustering and Trend Detection of Rainfall Erosivity Density in Greece. Water 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. An Examination of Procedures for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Data Set. Psychometrika 1985, 50, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust: An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. Journal of statistical software 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantas, K.; Sidiropoulos, E. Intra-Storm Pattern Recognition through Fuzzy Clustering. Hydrology 2021, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsiou, C.; Volakakis, M.; Doublidis, P. Hellenic Cadastre: State of the Art Experience, Proposals and Future Strategies. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2001, 25, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, A. Cadastre 2020; Editions Ziti: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2014; ISBN 978-960-456-423-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vantas, K. Improving the positional accuracy of cadastral maps via Machine Learning methods, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022.

- Cadastre: The First Public Agency to Integrate Artificial Intelligence (in Greek) Available online:. Available online: https://www.ktimatologio.gr/grafeio-tipou/deltia-tipou/1493 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Greek National Cadastre - Open Data Portal Available online:. Available online: https://data.ktimatologio.gr/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Veis, G. Reference systems and the realization of the Hellenic Geodetic Reference System 1987; Technika Chronika; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou, A.; Livieratos, E. Geometric geodesy and networks; Editions Ziti: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2000; ISBN 960-431-612-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Mapping and Cadastral Organization Tables of coefficients for coordinates transformation of the Hellenic area; HEMCO: Athens, Greece, 1995.

- R Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Foundation for statistical computing Vienna, Austria 2025.

- Maechler, M.; original), P.R. (Fortran; original), A.S. (S; original), M.H. (S; Hornik [trl, K.; maintenance(1999-2000)), ctb] (port to R.; Studer, M.; Roudier, P.; Gonzalez, J.; Kozlowski, K.; et al. Cluster: “Finding Groups in Data”: Cluster Analysis Extended Rousseeuw et Al. 2024.

- Hahsler, M.; Piekenbrock, M.; Arya, S.; Mount, D.; Malzer, C. Dbscan: Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) and Related Algorithms 2025.

- Fraley, C.; Raftery, A.E.; Scrucca, L.; Murphy, T.B.; Fop, M. Mclust: Gaussian Mixture Modelling for Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation 2024.

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses 2020.

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; Brand, T. van den; et al. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics 2024.

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R.; Racine, E.; Sumner, M.; Cook, I.; Keitt, T.; Lovelace, R.; Wickham, H.; Ooms, J.; Müller, K.; et al. Sf: Simple Features for R 2024.

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006; Vol. 4.

- Sarle, W.S. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis 1991.

- Dunn, J.C. A Fuzzy Relative of the ISODATA Process and Its Use in Detecting Compact Well-Separated Clusters. Journal of Cybernetics 1973, 3, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C. Pattern Recognition with Fuzzy Objective Function Algorithms; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Nayak, J.; Naik, B.; Behera, H.S. Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) Clustering Algorithm: A Decade Review from 2000 to 2014. In Proceedings of the Computational Intelligence in Data Mining - Volume 2; Jain, L.C., Behera, H.S., Mandal, J.K., Mohapatra, D.P., Eds.; Springer India: New Delhi, 2015; pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Xia, Z.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Q. The Range of the Value for the Fuzzifier of the Fuzzy C-Means Algorithm. Pattern Recognition Letters 2012, 33, 2280–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Syakur, M.A.; Khotimah, B.K.; Rochman, E.M.S.; Satoto, B.D. Integration K-Means Clustering Method and Elbow Method for Identification of the Best Customer Profile Cluster. In Proceedings of the IOP conference series: materials science and engineering; IOP Publishing, 2018; Vol. 336; p. 012017. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. knowledge discovery and data mining; 1996; Vol. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegel, H.; Kröger, P.; Sander, J.; Zimek, A. Density-based Clustering. WIREs Data Min & Knowl 2011, 1, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahsler, M.; Piekenbrock, M.; Doran, D. Dbscan: Fast Density-Based Clustering with R. Journal of Statistical Software 2019, 91, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D.A. Gaussian Mixture Models. Encyclopedia of biometrics 2009, 741, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Scrucca, L.; Fraley, C.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation Using Mclust in R; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023; ISBN 978-1-032-23495-3.

- Scrucca, L.; Fop, M.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. Mclust 5: Clustering, Classification and Density Estimation Using Gaussian Finite Mixture Models. The R journal 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley, C.; Raftery, A.E. Model-Based Clustering, Discriminant Analysis, and Density Estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2002, 97, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-S.; Lai, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y. A Robust EM Clustering Algorithm for Gaussian Mixture Models. Pattern Recognition 2012, 45, 3950–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahapure, K.R.; Nicholas, C. Cluster Quality Analysis Using Silhouette Score. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th international conference on data science and advanced analytics (DSAA); IEEE; 2020; pp. 747–748. [Google Scholar]

- Arbelaitz, O.; Gurrutxaga, I.; Muguerza, J.; Pérez, J.M.; Perona, I. An Extensive Comparative Study of Cluster Validity Indices. Pattern recognition 2013, 46, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Republic Approval of technical specifications and the regulation of estimated fees for cadastral survey studies for the creation of the National Cadastre in the remaining areas of the country; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2016; p. 228.

- Sisman, Y. Coordinate Transformation of Cadastral Maps Using Different Adjustment Methods. Journal of the Chinese Institute of Engineers 2014, 37, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Liang, D.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S. Positional Accuracy Improvement: A Comparative Study in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2011, 25, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Agugliaro, F.; Montoya, F.G.; San-Antonio-Gómez, C.; López-Márquez, S.; Aguilera, M.J.; Gil, C. The Assessment of Evolutionary Algorithms for Analyzing the Positional Accuracy and Uncertainty of Maps. Expert Systems with Applications 2014, 41, 6346–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.A. Computing Helmert Transformations. Journal of computational and applied mathematics 2006, 197, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Min | Mean | Median | Max | SD | Skew | Kurtosis | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | -0.95 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 1.21 | 0.33 | -0.06 | -0.65 | 10.67 |

| ΔN | -1.13 | -0.50 | -0.53 | 0.84 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.66 |

| L | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 1.33 | 0.25 | 0.28 | -0.47 | 0.39 |

| Algorithm | Mean Silhouette Score |

|---|---|

| FCM | 0.43 |

| DBSCAN | 0.33 |

| GMM | 0.27 |

| Algorithm | Cluster | Number of Points | Mean ΔE (m) | Mean ΔN (m) | SD ΔE (m) | SD ΔN (m) | Mean Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCM | 1 | 178 | -0.336 | -0.224 | 0.184 | 0.215 | 0.471 |

| 2 | 158 | 0.385 | -0.831 | 0.139 | 0.11 | 0.923 | |

| 3 | 164 | 0.068 | -0.462 | 0.169 | 0.262 | 0.537 | |

| DBSCAN | 0 (noise) | 102 | 0.088 | -0.172 | 0.366 | 0.387 | 0.47 |

| 1 | 398 | 0.008 | -0.576 | 0.332 | 0.246 | 0.678 | |

| GMM | 1 | 103 | 0.077 | -0.166 | 0.352 | 0.37 | 0.458 |

| 2 | 397 | 0.01 | -0.579 | 0.336 | 0.249 | 0.682 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).