Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

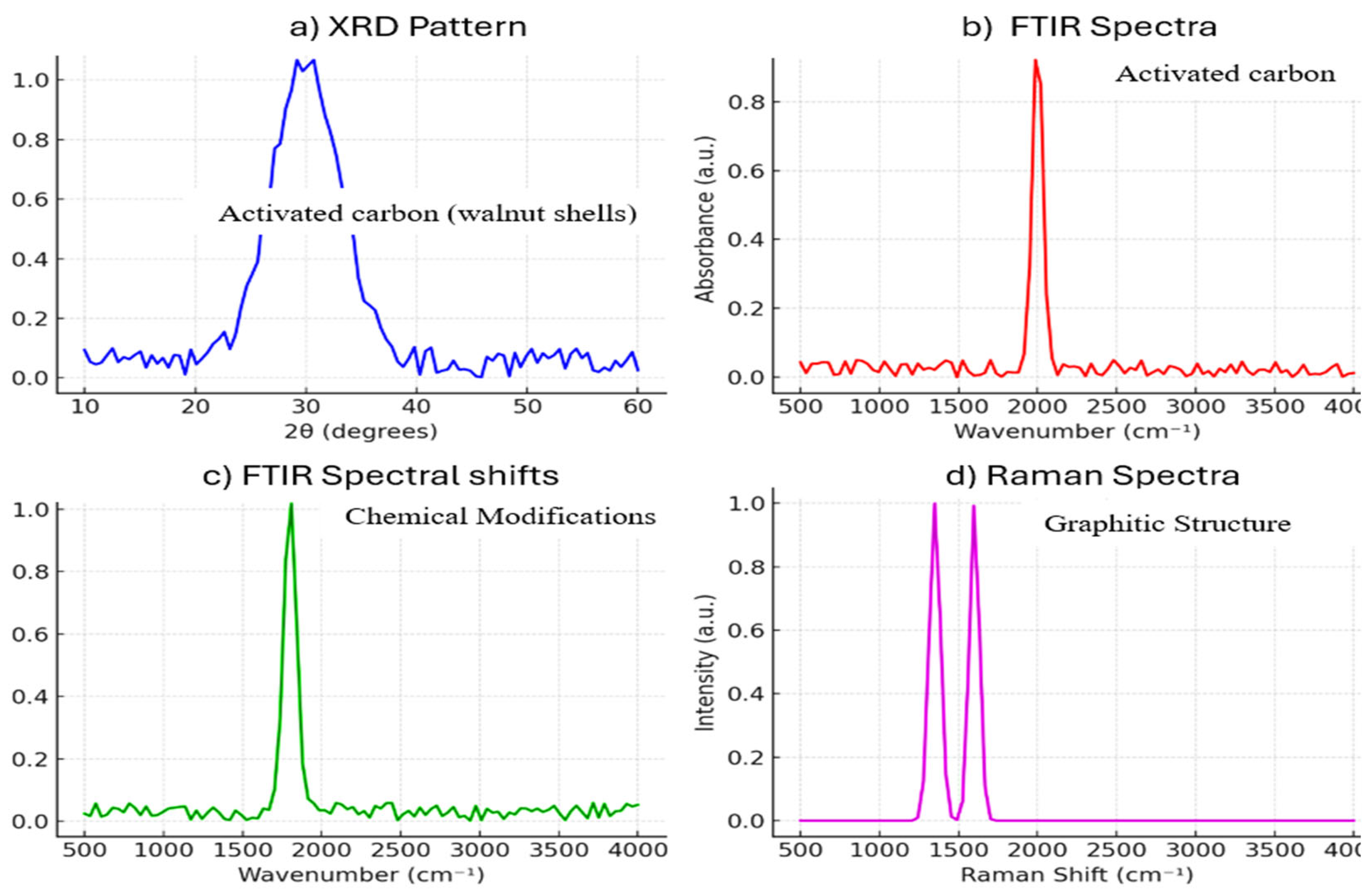

3.1. Characterization of Walnut Shell-Derived Activated Carbon

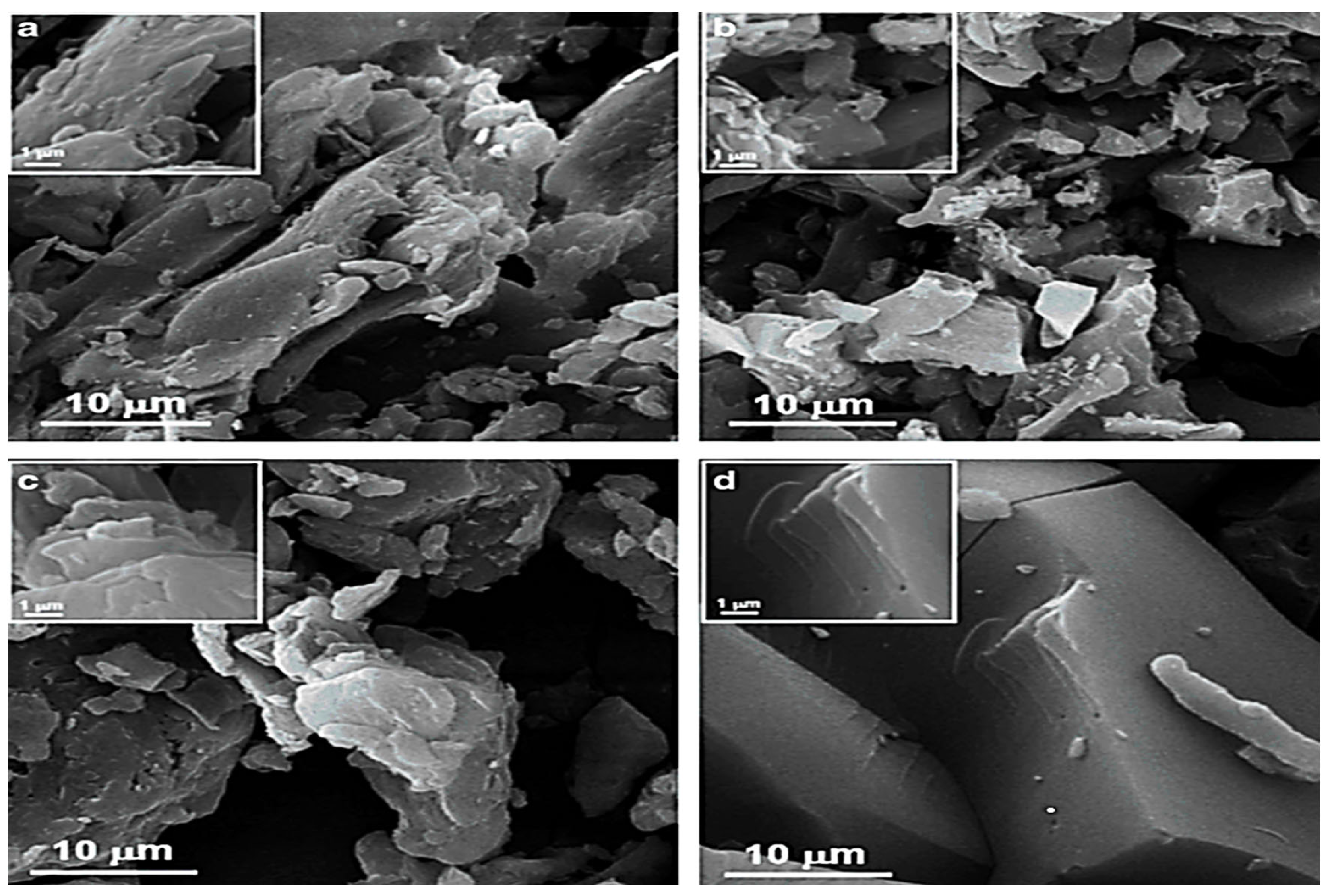

3.1.1. Surface Morphology (SEM Analysis)

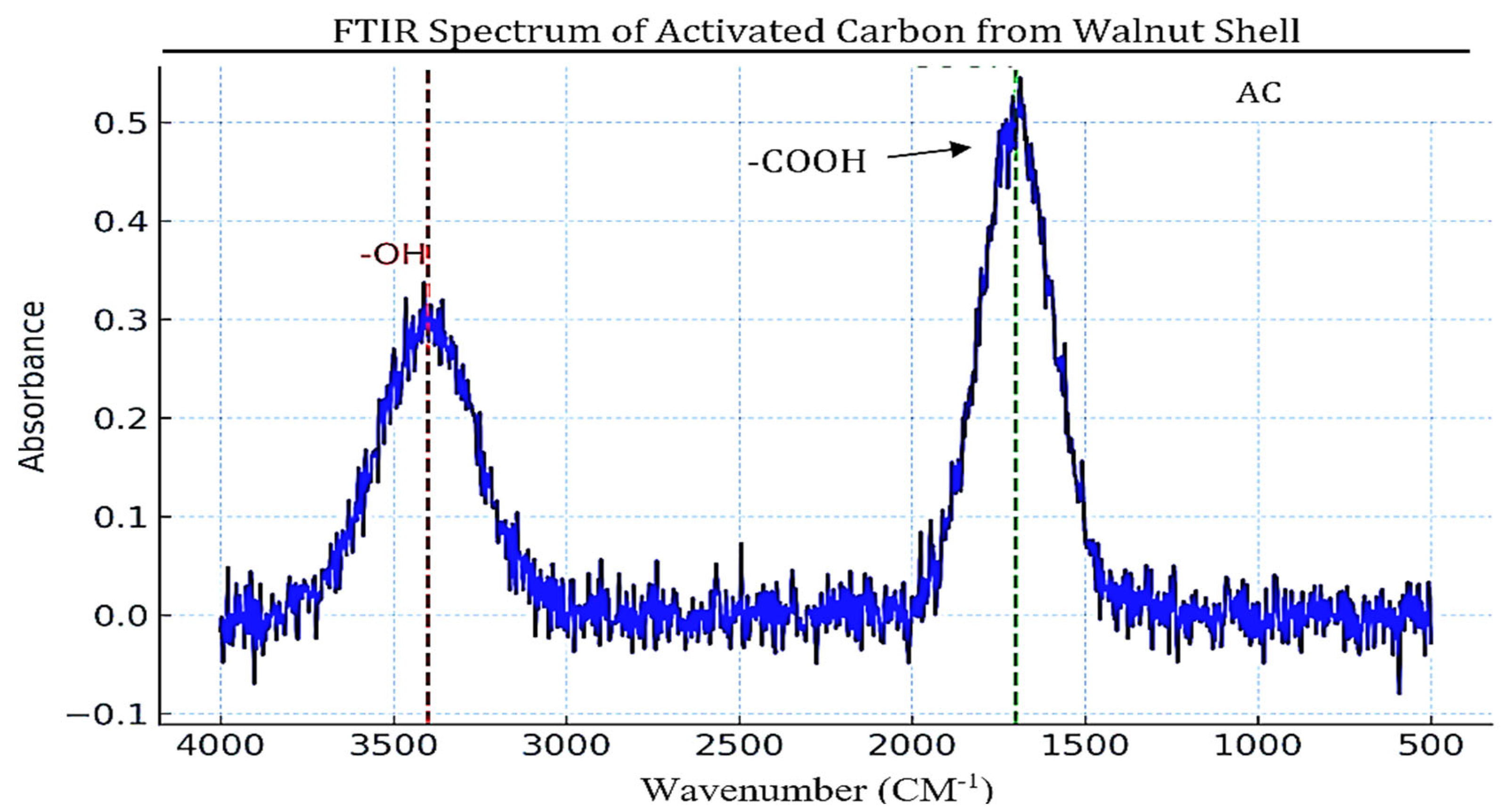

3.1.2. Chemical Structure (FTIR Analysis)

- 3,400 cm⁻¹: O-H stretching waves involving the existence of hydroxyl (-OH) functional groups responsible for hydrogen bonding and the hydrophilicity of activated carbon [101].

- 1,700 cm⁻¹: C=O stretching waves associated with carbonyl (C=O) functional groups which include carboxyl, ketones, and aldehydes and are involved in acid-base interaction during adsorption [75].

- 1,200 cm⁻¹: C-O stretching waves ascribed to carboxyl (-COO) and ether (-C-O-C) groups which enhance surface reactivity and adsorption affinity [8].

3.1.3. Study of Surface Areas and Porosity (BET Analysis)

3.1.4. Crystalline Structure (XRD Analysis)

3.2. Adsorption Performance

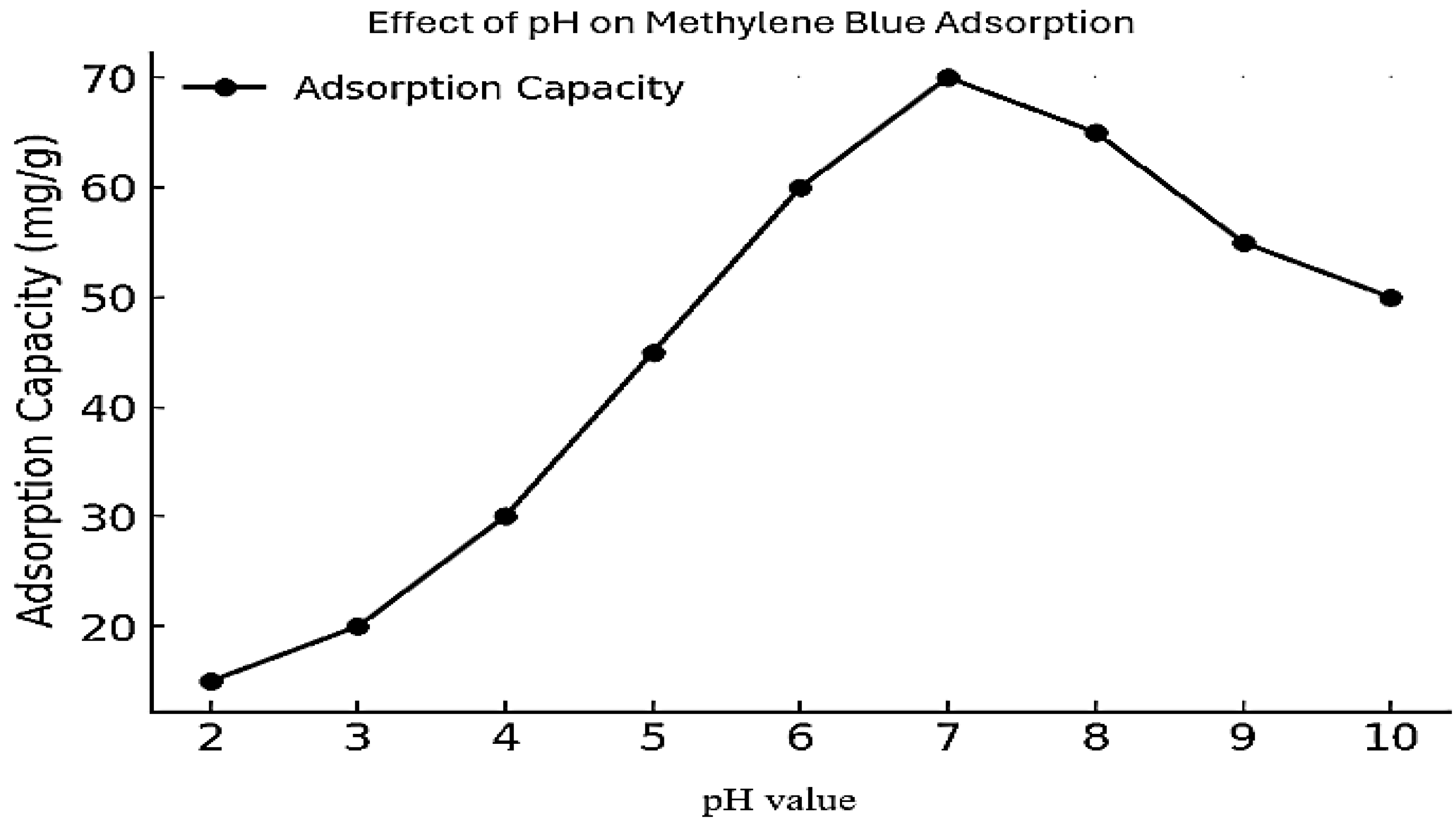

3.2.1. The Impact of pH and Adsorption

3.2.2. Effect of Contact Time

3.2.3. Concentration Affect

3.2.4. Isotherm Studies

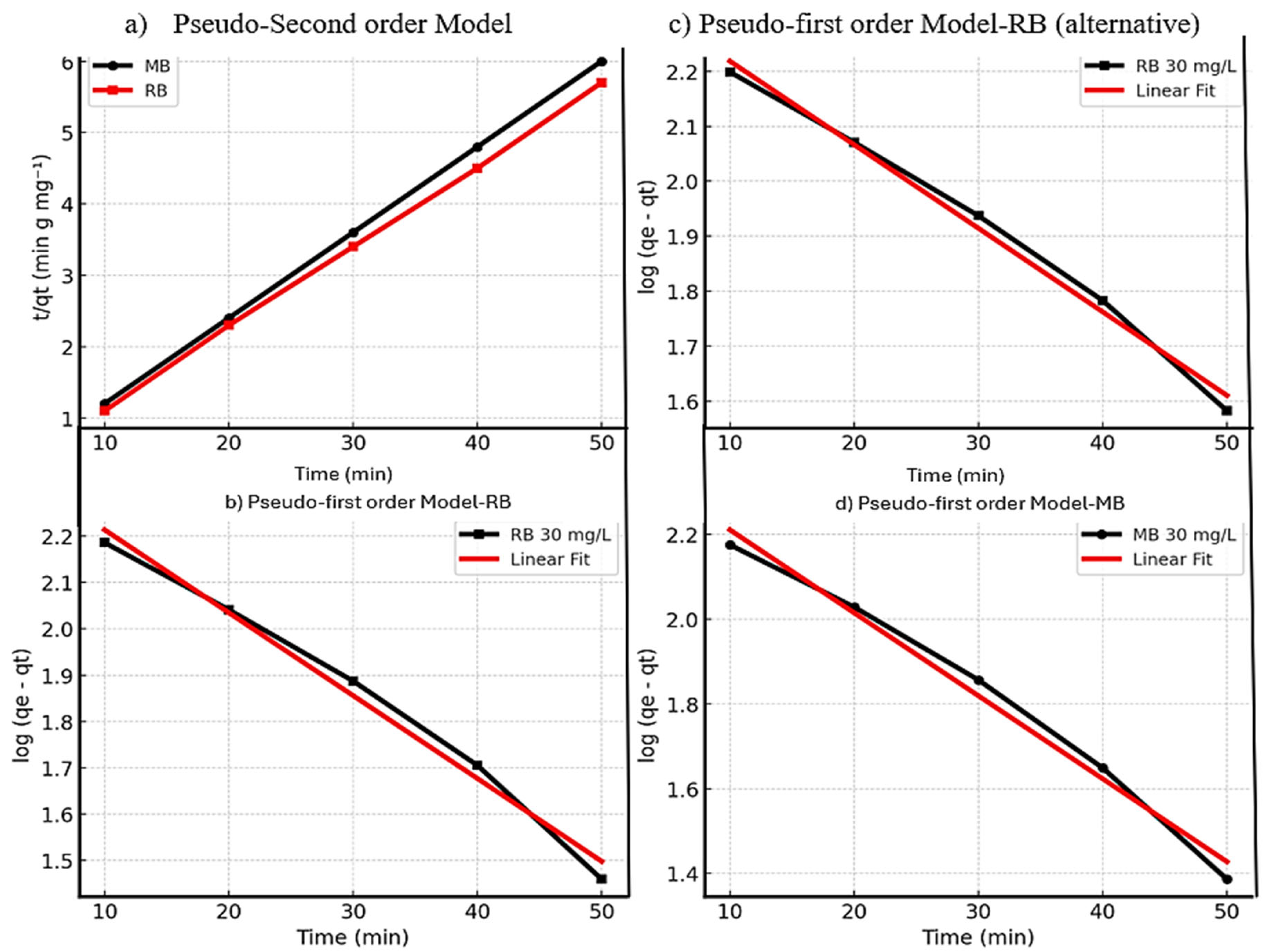

3.2.5. Kinetic Studies.

3.3. Comparison with Other Adsorbents

| Adsorbent Source | Surface Area (m²/g) | Total Pore Volume (cm³/g) | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walnut Shell | 1,250 | 0.85 | 350 | High surface area, bimodal pore structure, and efficient adsorption for small and large molecules [31]. |

| Coconut Shell | 1,000 | 0.70 | 280 | Moderate surface area with predominance of micropores [70]. |

| Rice Husk | 850 | 0.55 | 220 | Limited micropores that are fit for small molecules [119]. |

| Peanut Shell | 900 | 0.60 | 240 | Possesses mesopores and low adsorption, preferentially for larger-sized molecules [39]. |

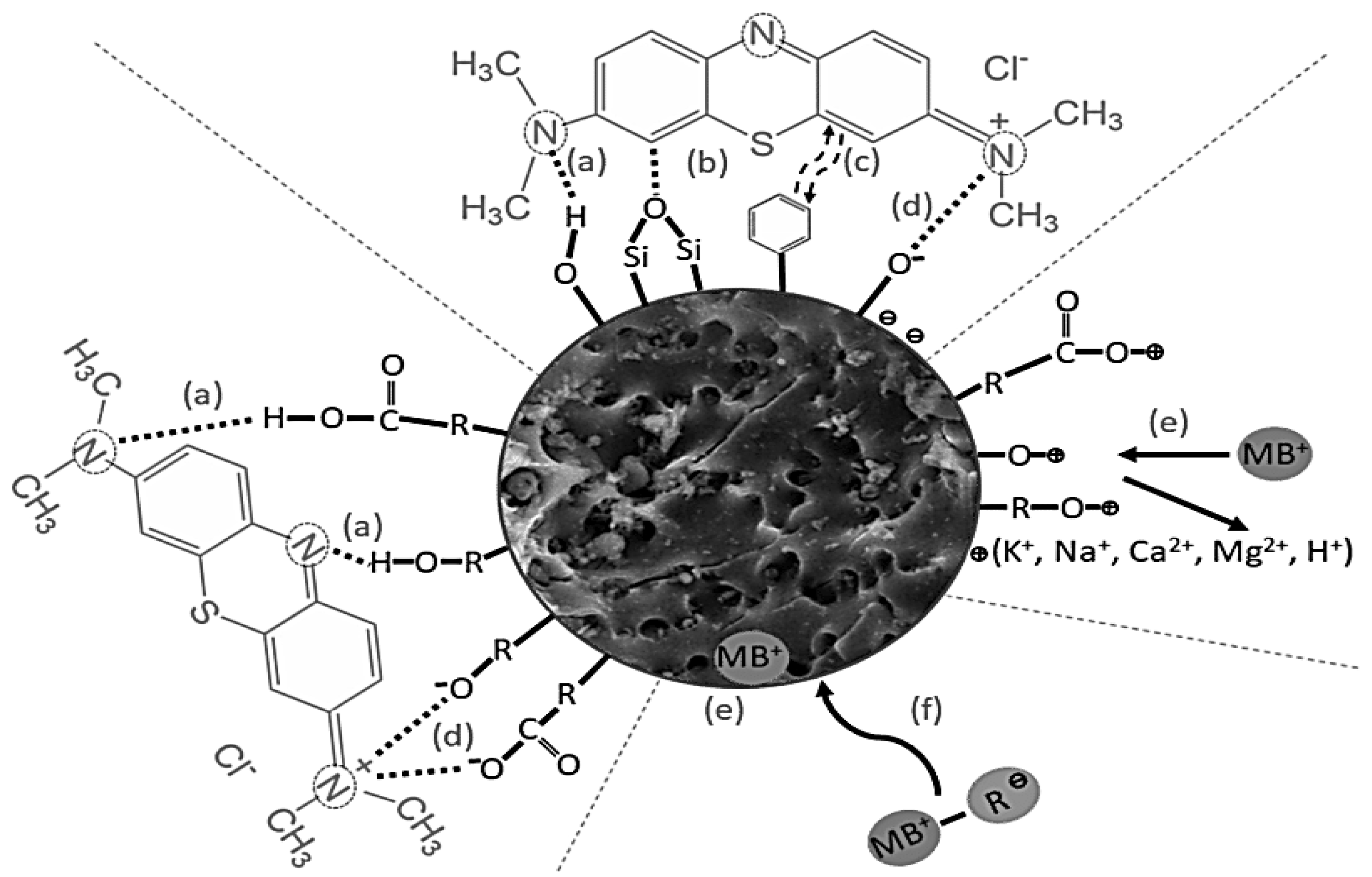

3.4. Mechanism of Adsorption

3.5. Regeneration and Reusability of Walnut Shell-Derived Activated Carbon

4.1.1. Removal of Contaminants Using Walnut Shell-Activated Carbon

4.1.2. Removal of Dyes

- Methylene Blue (MB): As demonstrated in this study, walnut shell-derived AC has a high adsorption capacity for methylene blue, a common dye used in the textile industry [71]. The adsorption process is driven by electrostatic interactions and π-π stacking between the dye molecules and the AC surface [115].

4.2. Air Purification

4.3. Soil Remediation

4.4. Industrial Applications

4.5. Economic and Environmental Benefits

| Pollutant | Adsorbent Type | Efficiency | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue | Walnut Shell-Derived AC | 450 mg/g | Superior adsorption capacity compared to commercial AC and other adsorbents [64]. |

| Commercial AC | 400 mg/g | Moderate adsorption capacity. | |

| Other Adsorbents | 300 mg/g | Lower adsorption capacity [33]. | |

| Lead (Pb) | Walnut Shell-Derived AC | 95% removal | Highest removal efficiency for heavy metals. |

| Commercial AC | 90% removal | Slightly lower efficiency than walnut shell-derived AC. | |

| Other Adsorbents | 85% removal | Least efficient among the three. | |

| Benzene | Walnut Shell-Derived AC | 90% removal | Excellent performance in VOC removal. |

| Commercial AC | 88% removal | Comparable but slightly lower efficiency [90]. | |

| Other Adsorbents | 80% removal | Least effective for benzene removal |

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abid, L. H.; Mussa, Z. H.; Deyab, I. F.; Al-Ameer, L. R.; Al-Saedi, H. F. S.; Al-Qaim, F. F.; ... & Yaseen, Z. M. Walnut Shell as a bio-activated carbon for elimination of malachite green from its aqueous solution: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Results in Chemistry, 2025, 102124. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Banat, F.; Alsafar, H. & Hasan, S. W. Algae biotechnology for industrial wastewater treatment, bioenergy production, and high value bioproducts. Science of The Total Environment, 2022, 806, 150585. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S. A. R.; Kalaee, M. R.; Moradi, O.; Nosratinia, F. & Abdouss, M. Core–shell activated carbon-ZIF-8 nanomaterials for the removal of tetracycline from polluted aqueous solution. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials, 2021, 4, 1384-1397. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42114-021-00357-3.

- Ahmed, T.; Noman, M.; Manzoor, N.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ijaz, M.;... & Li, B. Recent advances in nanoparticles associated ecological harms and their biodegradation: global environmental safety from nano-invaders. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(5), 106093. [CrossRef]

- Alabdullah, S. S.; Ismail, H. K.; Ryder, K. S. & Abbott, A. P. Evidence supporting an emulsion polymerisation mechanism for the formation of polyaniline. Electrochimica Acta, 2020, 354, 136737. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Dib, S. S. Utilization of nano-olive stones in environmental remediation of methylene blue from water. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, 2020, 18, 63-77. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40201-019-00438-y.

- Aliyu, A.; Lee, J. G. M. & Harvey, A. P. Microalgae for biofuels via thermochemical conversion processes: A review of cultivation, harvesting and drying processes, and the associated opportunities for integrated production. Bioresource Technology Reports, 2021, 14, 100676. [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.; Lee, J. G. M. & Harvey, A. P. Microalgae for biofuels via thermochemical conversion processes: A review of cultivation, harvesting and drying processes, and the associated opportunities for integrated production. Bioresource Technology Reports, 2021, 14, 100676. [CrossRef]

- Al-Othman, Z. A.; Habila, M. A.; Ali, R. & EL-DIN HASSOUNA, M. S. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies for Methylene Blue Adsorption using Activated Carbon Prepared from Agricultural and Municipal Solid Wastes. Asian Journal of Chemistry, 2013, 25(15). [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, K. & Altarawneh, M. Bromination mechanisms of aromatic pollutants: formation of Br 2 and bromine transfer from metallic oxybromides. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022, 1-8. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-021-17650-9.

- Asadollah, S. B. H. S.; Sharafati, A.; Motta, D. & Yaseen, Z. M. River water quality index prediction and uncertainty analysis: A comparative study of machine learning models. Journal of environmental chemical engineering, 2021, 9(1), 104599. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M. K.; Raveendran, S.; Ravindran, B. & Yan, B. (Eds.). Biofuels Production from Lignocellulosic Materials, 2024, Elsevier. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-97-5544-8_10.

- Blanchard, R. & Mekonnen, T. H. Synchronous pyrolysis and activation of poly (ethylene terephthalate) for the generation of activated carbon for dye contaminated wastewater treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2022, 10(6), 108810. [CrossRef]

- Bougheriou, F. & Ghoualem, H. Synthesis and characterization of activated carbons from walnut shells to remove diclofenac. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. Review Article, 2023, 42(9). https://www.ijcce.ac.ir/article_704312_7249a09d75f2646366c3c0574e556f88.pdf.

- Chaudhari, S. D.; Deshpande, A.; Kularkar, A.; Tandulkar, D.; Hippargi, G.; Rayalu, S. S. & Nagababu, P. Engineering of heterojunction TiO2/CaIn2S4@ rGO novel nanocomposite for rapid photodegradation of toxic contaminants. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2022, 114, 305-316. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, J.; Bai, P. & Guo, X. Boron removal and reclamation by magnetic magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticle: An adsorption and isotopic separation study. Separation and Purification Technology, 2020, 231, 115930. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L. & Wang, X. Low-temperature plasma induced phosphate groups onto coffee residue-derived porous carbon for efficient U (VI) extraction. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2022, 122, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, G.; Li, Q.; Liu, C. & Cheng, Y. Spatial variation and driving mechanism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) emissions from vehicles in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022, 336, 130210. [CrossRef]

- Devi, M. S.; Thangadurai, T. D.; Shanmugaraju, S.; Selvan, C. P. & Lee, Y. I. Biomass waste from walnut shell for pollutants removal and energy storage: a review on waste to wealth transformation. Adsorption, 2024, 30(6), 891-913. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10450-024-00458-7.

- Devi, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Bulla, M.; Jatrana, A.; Rani, R.; ... & Singh, P. Recent advancement in biomass-derived activated carbon for waste water treatment, energy storage, and gas purification: a review. Journal of Materials Science, 2023, 58(30), 12119-12142. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10853-023-08773-0.

- DhanaRamalakshmi, R.; Murugan, M. & Jeyabal, V. Arsenic removal using Prosopis spicigera L. wood (PsLw) carbon–iron oxide composite. Applied Water Science, 2020, 10(9), 1-10. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13201-020-01298-w.

- Doszhanov Y.O., Mansurov Z.A., Ongarbaev Y.K., Tileuberdi Y., Zhubanova A.A. The study of biodegradation of diesel fuels by different strains of Pseudomonas // Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2014, 467, 12-15. https://www.scientific.net/AMM.467.12.

- Doszhanov, Y. O., Ongarbaev, Y. K., Hofrichter, M., Zhubanova, A. A., & Mansurov, Z. A. (2009). The using of pseudomonas cells for bioremediation of oil contaminating soils. Eurasian Chemico-Technological Journal, 11(1), 69-75. https://ect-journal.kz/index.php/ectj/article/view/681/621.

- Doszhanov, Y., Atamanov, M., Jandosov, J., Saurykova, K., Bassygarayev, Z., Orazbayev, A., ... & Sabitov, A. (2024). Preparation of Granular Organic Iodine and Selenium Complex Fertilizer Based on Biochar for Biofortification of Parsley. Scientifica, 2024(1), 6601899. [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov, Y., Sabitov, A., Mansurov, Z., & Kaiyrmanova, G. (2024). Bioremediation of Oil-Contaminated Soils of the Zhanazhol Deposit from West Kazakhstan by Pseudomonas mendocina H-3. Applied and Environmental Soil Science, 2024(1), 8510911. [CrossRef]

- Doszhanova, Y. O., Ongarbaev, Y. K., Mansurov, Z. A., Zhubanova, A. A., & Hofrichter, M. (2010). Bioremedation of oil and oil products bacterial species of the genus Pseudomonas. Eurasian Chemico-Technological Journal, 12(2), 157-164. https://ect-journal.kz/index.php/ectj/article/view/494/453.

- Fan, L.; Tu, Z. & Chan, S. H. Energy Reports, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Farghali, R. A.; Sobhi, M.; Gaber, S. E.; Ibrahim, H. & Elshehy, E. A. Adsorption of organochlorine pesticides on modified porous Al30/bentonite: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 13(8), 6730-6740. [CrossRef]

- Farghali, R. A.; Sobhi, M.; Gaber, S. E.; Ibrahim, H. & Elshehy, E. A. Adsorption of organochlorine pesticides on modified porous Al30/bentonite: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 13(8). [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, M.; Wahyuningsih, S.; Rahmawati, F. & Kusumaningsih, T. Freundlich adsorption isotherm in the perspective of chemical kinetics (III): Isolation method approach. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2020, 858, No. 1, 012010. [CrossRef]

- Fordos, S.; Abid, N.; Gulzar, M.; Pasha, I.; Oz, F.; Shahid, A.; ... & Aadil, R. M. Recent development in the application of walnut processing by-products (walnut shell and walnut husk). Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2023, 13(16), 14389-14411. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-023-04778-6.

- Fordos, S.; Abid, N.; Gulzar, M.; Pasha, I.; Oz, F.; Shahid, A.; ... & Aadil, R. M. Recent development in the application of walnut processing by-products (walnut shell and walnut husk). Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2023, 13(16), 14389-14411. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-023-04778-6.

- Fordos, S.; Abid, N.; Gulzar, M.; Pasha, I.; Oz, F.; Shahid, A.; ... & Aadil, R. M. Recent development in the application of walnut processing by-products (walnut shell and walnut husk). Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2023, 13(16), 14389-14411. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-023-04778-6.

- Gan, Y. X. Activated carbon from biomass sustainable sources, 2021, C, 7(2), 39.https://www.mdpi.com/2311-5629/7/2/39.

- Gao, H.; Zhou, Y. & Wu, D. Sustainable production of activated carbon from walnut shells for the removal of methylene blue: Process optimization and adsorption mechanism. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2023, 35, e00456. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, L.; Wan, W.; Xu, Q. & Li, Z. Preparation of activated carbons from walnut shell by fast activation with H3PO4: influence of fluidization of particles. International journal of chemical reactor engineering, 2018, 16(2), 20170074. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C. & Wang, J. Preparation of activated carbon adsorption materials derived from coal gasification fine slag via low-temperature air activation. Gas Science and Engineering, 2023, 117, 205069. [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, V., Alfè, M., Raganati, F., Zhumagaliyeva, A., Doszhanov, Y., Ammendola, P., & Chirone, R. (2019). CO2 adsorption under dynamic conditions: An overview on rice husk-derived sorbents and other materials. Combustion Science and Technology. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/00102202.2018.1546697.

- Geczo, A.; Giannakoudakis, D. A.; Triantafyllidis, K.; Elshaer, M. R.; Rodríguez-Aguado, E. & Bashkova, S. Mechanistic insights into acetaminophen removal on cashew nut shell biomass-derived activated carbons. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021, 28, 58969-58982. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-019-07562-0.

- Gomes, J.; Roccamante, M.; Contreras, S.; Medina, F.; Oller, I. & Martins, R. C. Scale-up impact over solar photocatalytic ozonation with benchmark-P25 and N-TiO2 for insecticides abatement in water. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(1), 104915. [CrossRef]

- Habib, H.; Wani, I. S. & Husain, S. High performance nanostructured symmetric reduced graphene oxide/polyaniline supercapacitor electrode: effect of polyaniline morphology. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, 55, 105732. [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Jia, L.; Wang, H. & Qiang, Z. Degradation of micropollutants in flow-through UV/chlorine reactors: Kinetics, mechanism, energy requirement and toxicity evaluation. Chemosphere, 2022, 307, 135890. [CrossRef]

- Hasanpour, M. & Hatami, M. Photocatalytic performance of aerogels for organic dyes removal from wastewater: Review study. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 2020, 309, 113094. [CrossRef]

- Hingangavkar, G. M.; Kadam, S. A.; Ma, Y. R.; Bandgar, S. S.; Mulik, R. N. & Patil, V. B. MoS2-GO hybrid sensor: a discerning approach for detecting harmful H2S gas at room temperature. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023, 472, 144789. [CrossRef]

- Homero, R. F. Evaluation of different biomass-based materials for removal of sertraline from water (Doctoral dissertation), 2024. https://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/entities/publication/2b30655e-5487-40da-b4eb-e79f420bbcbe.

- Hossain, M. Z. & Chowdhury, M. B. I. Biobased Activated Carbon and Its Application, 2024. https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/1203358.

- Hossain, M. Z. & Chowdhury, M. B. I. Biobased Activated Carbon and Its Application, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bao, F.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. & Liu, J. Coal gasification fine slag derived porous carbon-silicon composite as an ultra-high capacity adsorbent for Rhodamine B removal. Separation and Purification Technology, 2025, 353, 128397. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Jalees, M. I.; Farooq, M. U.; Cevik, E. & Bozkurt, A. Superfast adsorption and high-performance tailored membrane filtration by engineered Fe-Ni-Co nanocomposite for simultaneous removal of surface water pollutants. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2022, 652, 129751. [CrossRef]

- Jian, L.; Yan, L.; Li, G.; Rao, P.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J. & He, L. Activation of persulfate by magnetic granular activated carbon for tetracycline removal: performance, mechanism insight, and applications. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2024, 14(17), 20611-20621. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-023-04186-w.

- Kambarova, G. B. & Sarymsakov, S. Preparation of activated charcoal from walnut shells. Solid Fuel Chemistry, 2008, 42(3), 183-186. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3103/s0361521908030129.

- Kang, D. J. & Kim, B. J. Butane working capacity of highly mesoporous polyimide-based activated carbon fibers. Carbon Letters, 2024, 34(3), 1007-1014. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42823-023-00645-6.

- Khadir, A.; Mollahosseini, A.; Tehrani, R. M. & Negarestani, M. A review on pharmaceutical removal from aquatic media by adsorption: understanding the influential parameters and novel adsorbents. Sustainable Green Chemical Processes and their Allied Applications, 2020, 207-265. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42284-4_8.

- Ko, K. J.; Jin, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, K. M.; Mofarahi, M. & Lee, C. H. Role of ultra-micropores in CO2 adsorption on highly durable resin-based activated carbon beads by potassium hydroxide activation. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2021, 60(40), 14547-14563. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.iecr.1c02430.

- Kowalik-Klimczak, A.; Woskowicz, E. & Kacprzyńska-Gołacka, J. The surface modification of polyamide membranes using graphene oxide. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2020, 587, 124281. [CrossRef]

- Kukowska, S.; Nowicki, P. & Szewczuk-Karpisz, K. New fruit waste-derived activated carbons of high adsorption performance towards metal, metalloid, and polymer species in multicomponent systems. Scientific Reports, 2025, 15(1), 1082. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-85409-0.

- Kurniawan, Y. S.; Imawan, A. C.; Stansyah, Y. M. & Wahyuningsih, T. D. Application of activated bentonite impregnated with PdO as green catalyst for acylation reaction of aromatic compounds. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(4), 105508. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, L. & Tao, J. Boosting Ion Storage and Desolvation Kinetics in Biomass-Derived Nanoporous Carbon for Advanced Supercapacitor Energy Storage, Available at SSRN 5081332. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5081332.

- Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Xue, N.; Meng, X.; Xie, L. & Zhao, G. Efficient production of activated carbon with well-developed pore structure based on fast pyrolysis-physical activation. Journal of the Energy Institute, 2024, 115, 101685. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiu, J.; Hu, Y.; Ren, X.; He, L.; Zhao, N. & Zhao, X. Characterization and comparison of walnut shells-based activated carbons and their adsorptive properties. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2020, 38(9-10), 450-463. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiu, J.; Hu, Y.; Ren, X.; He, L.; Zhao, N.; ... & Zhao, X. Characterization and comparison of walnut shells-based activated carbons and their adsorptive properties. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2020, 38(9-10), 450-463. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sheng, M.; Gong, S.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, X. & Qu, J. Flexible and multifunctional phase change composites featuring high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management for use in electronic devices. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2022, 430, 132928. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. X.; Wu, Z. F.; Sun, Q. H.; Zhang, M. & Duan, H. M. Preparation of carbon material derived from walnut shell and its gas-sensing properties. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2023, 52(5), 3092-3102. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11664-023-10218-y.

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Liu, X.; ... & Dai, Y. Metolachlor adsorption using walnut shell biochar modified by soil minerals. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 308, 119610. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Shi, X.; He, Q.; Liu, Y.; An, X.; Cui, S. & Du, D. Dynamic modeling and numerical investigation of novel pumped thermal electricity storage system during startup process. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, 55, 105409. [CrossRef]

- Mabu, D. Production of Polymeric Carbon Solids (PCS) and Their Application As Adsorbents for Potentially Toxic Elements in Water and Wastewater. University of Johannesburg (South Africa), 2020. https://www.proquest.com/openview/763b0834e283ac4abc58855a746be0d2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y.

- Mansurov, Z. A., Velasco, L. F., Lodewyckx, P., Doszhanov, E. O., & Azat, S. (2022). Modified Carbon Sorbents Based on Walnut Shell for Sorption of Toxic Gases. Journal of Engineering Physics and Thermophysics, 95(6), 1383-1392. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10891-022-02607-7.

- Mansurov, Z., Doszhanov, Y. O., Ongarbaev, Y. K., Akimbekov, N. S., & Zhubanova, A. A. (2013). The evaluation of process of bioremediation of oil-polluted soils by different strains of Pseudomonas. Advanced Materials Research, 647, 363-367. https://www.scientific.net/AMR.647.363.

- Mbachu, C. A.; Babayemi, A. K.; Egbosiuba, T. C.; Ike, J. I.; Ani, I. J. & Mustapha, S. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles by Taguchi design of experiment method for effective adsorption of methylene blue and methyl orange from textile wastewater. Results in Engineering, 2023, 19, 101198. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, S.; Houweling, D. & Dagnew, M. Establishing mainstream nitrite shunt process in membrane aerated biofilm reactors: impact of organic carbon and biofilm scouring intensity. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2020, 37, 101460. [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, S. S.; Aziz, F.; Nor, A. R. M.; Mohammed, A. M.; Mhamad, S. A.; Jaafar, J.; ... & Ismail, A. F. Photocatalytic degradation of humic acid using a novel visible-light active α-Fe2O3/NiS2 composite photocatalyst. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(4), 105682. [CrossRef]

- Moud, A. A. Advanced applications of cellulose nanocrystals: a mini review, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Odoom, J. K. Application of modified walnut shell adsorbents in oily wastewater treatment (Doctoral dissertation, University of Northern British Columbia), 2025. https://arcabc.ca/islandora/object/unbc%3A59602.

- Omarova, A.; Baizhan, A.; Baimatova, N.; Kenessov, B. & Kazemian, H. New in situ solvothermally synthesized metal-organic framework MOF-199 coating for solid-phase microextraction of volatile organic compounds from air samples. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2021, 328, 111493. [CrossRef]

- Omarova, A.; Baizhan, A.; Baimatova, N.; Kenessov, B. & Kazemian, H. New in situ solvothermally synthesized metal-organic framework MOF-199 coating for solid-phase microextraction of volatile organic compounds from air samples. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2021, 328, 111493. [CrossRef]

- Panbarasu, K.; Ranganath, V. R. & Prakash, R. V. An investigation on static failure behaviour of CFRP quasi isotropic laminates under in-plane and out-of-plane loads. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2021, 39, 1465-1471. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J. K.; Tauseef, S. M.; Manna, S.; Patel, R. K.; Singh, V. K. & Dasgotra, A. (Eds.). Application of Nanotechnology for Resource Recovery from Wastewater. CRC Press, 2024. https://scijournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jctb.6369.

- Pereira, S. K.; Kini, S.; Prabhu, B. & Jeppu, G. P. A simplified modeling procedure for adsorption at varying pH conditions using the modified Langmuir–Freundlich isotherm. Applied Water Science, 2023, 13(1), 29. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13201-022-01800-6.

- Phetrak, A.; Sangkarak, S.; Ampawong, S.; Ittisupornrat, S. & Phihusut, D. Kinetic adsorption of hazardous methylene blue from aqueous solution onto iron-impregnated powdered activated carbon. Environment and Natural Resources Journal, 2019, 17(4), 78-86. https://ph02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ennrj/article/view/201155.

- Phetrak, A.; Sangkarak, S.; Ampawong, S.; Ittisupornrat, S. & Phihusut, D. Kinetic adsorption of hazardous methylene blue from aqueous solution onto iron-impregnated powdered activated carbon. Environment and Natural Resources Journal, 2019, 17(4), 78-86. https://ph02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ennrj/article/view/201155.

- RATTANET, C.; KNIJNENBURG, J. T. & NGERNYEN, Y. Kinetics and isotherm studies of methylene blue adsorption on activated carbon derived from Chrysanthemum: solid waste of beverage industry. Journal of the Japan Institute of Energy, 2022, 101(7), 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Ray, S. Microwave-assisted conversion of coal and biomass to activated carbon. Radiation Technologies and Applications in Materials Science, 2022, 59-98. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003321910-3/microwave-assisted-conversion-coal-biomass-activated-carbon-sudip-ray.

- Rodrigues, A. D. O.; dos Santos Montanholi, A.; Shimabukuro, A. A.; Yonekawa, M. K. A.; Cassemiro, N. S.; Silva, D. B.; ... & Dos Santos, E. D. A. N-acetylation of toxic aromatic amines by fungi: Strain screening, cytotoxicity and genotoxicity evaluation, and application in bioremediation of 3, 4-dichloroaniline. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023, 441, 129887. [CrossRef]

- Sabitov, A., Atamanov, M., Doszhanov, O., Saurykova, K., Tazhu, K., Kerimkulova, A., ... & Doszhanov, Y. (2024). Surface characteristics of activated carbon sorbents obtained from biomass for cleaning oil-contaminated soils. Molecules, 29(16), 3786. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/29/16/3786.

- Sando, M. S.; Farhan, A. M. & Jawad, A. H. Schiff-base system of glutaraldehyde crosslinked chitosan-algae-montmorillonite Clay K10 biocomposite: adsorption mechanism and optimized removal for methyl Violet 2B Dye. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials, 2024, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Seitzhanova, M., Azat, S., Yeleuov, M., Taurbekov, A., Mansurov, Z., Doszhanov, E., & Berndtsson, R. (2024). Production of Graphene Membranes from Rice Husk Biomass Waste for Improved Desalination. Nanomaterials, 14(2), 224. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/14/2/224.

- Shao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; ... & Ji, X. Renewable N-doped microporous carbons from walnut shells for CO 2 capture and conversion. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 2021, 5(18), 4701-4709. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2021/xx/d1se01000j/unauth.

- Sharma, G.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Lai, C. W.; Naushad, M.; Shehnaz & Stadler, F. J. Activated carbon as superadsorbent and sustainable material for diverse applications. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2022, 4184809.128765. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Wang, J.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, W. & Zhu, X. A feasible biochar derived from biogas residue and its application in the efficient adsorption of tetracycline from an aqueous solution. Environmental Research, 2022, 207, 112175. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumara, N. V. & Arya, B. Experimental performance evaluation of thermoacoustic refrigerator made up of poly-vinyl-chloride for different parallel plate stacks using air as a working medium. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2020, 22, 2160-2171. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. & Kumar, P. Pre-treatment of petroleum refinery wastewater by coagulation and flocculation using mixed coagulant: Optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology (RSM). Journal of water process engineering, 2020, 36, 101317. [CrossRef]

- SP, S. P. & Swaminathan, G. Thermogravimetric study of textile lime sludge and cement raw meal for co-processing as alternative raw material for cement production using response surface methodology and neural networks. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 2022, 25, 102100. [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Xiong, J.; Li, Q.; Luo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, T.; ... & Xu, K. Gaseous formaldehyde adsorption by eco-friendly, porous bamboo carbon microfibers obtained by steam explosion, carbonization, and plasma activation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023, 455, 140686. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1385894722061666.

- Tahraoui, H.; Amrane, A.; Belhadj, A. E. & Zhang, J. Modeling the organic matter of water using the decision tree coupled with bootstrap aggregated and least-squares boosting. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 2022, 27, 102419. [CrossRef]

- Tao, W. W.; Li, Q. T.; Zhou, T. Y. & Zhuang, D. D. The influence of ultrasonic assistance on microstructure and properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy prepared by laser cladding. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2024, 29, 5161-5165. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A. M. & Eltabey, R. M. Fractional kinetic strategy toward the adsorption of organic dyes: finding a way out of the dilemma relating to pseudo-first-and pseudo-second-order rate laws. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 2024, 128(6), 1063-1073. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.jpca.3c07615.

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J. & Sing, K. S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and applied chemistry, 2015, 87(9-10), 1051-1069. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, Y. & Chen, Z. An improved single particle model for lithium-ion batteries based on main stress factor compensation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 278, 123456. [CrossRef]

- Tileuberdi, Y., Ongarbayev, Y. K., Mansurov, Z. A., Kudaibergenov, K. K., & Doszhanov, Y. O. (2014). Ways of using rubber crumb from worn tires. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 446, 1512-1515. https://www.scientific.net/AMM.446-447.1512.

- Tunay, S.; Koklu, R. & Imamoglu, M. Highly Efficient and Environmentally Friendly Walnut Shell Carbon for the Removal of Ciprofloxacin, Diclofenac, and Sulfamethoxazole from Aqueous Solutions and Real Wastewater. Processes, 2024, 12(12), 2766. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R. & Zhang, Z. NIR laser-activated polydopamine-coated Fe3O4 nanoplatform used as a recyclable precise photothermal insecticide. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2022, 33, e00456. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, D.; Fang, K.; Zhu, W.; Peng, Q. & Xie, Z. Enhanced nitrate removal by physical activation and Mg/Al layered double hydroxide modified biochar derived from wood waste: Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(4), 105184. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chai, X.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, B.; Li, X. & Fu, L. Green synthesis of biomass-derived porous carbon with hierarchical pores and enhanced surface area for superior VOCs adsorption. Materials Today Communications, 2024, 39, 108906. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Si, B.; Watson, J, & Zhang, Y. Accelerating anaerobic digestion for methane production: Potential role of direct interspecies electron transfer. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2021, 145, 111069. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, X.; Xue, R.; ... & Wu, S. Adsorption of methylene blue on activated carbons prepared from penicillin mycelial residues via torrefaction and hydrothermal pretreatment. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2024, 14(22), 28933-28945. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-023-03998-0.

- Xi, H.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Wang, X.; ... & Ruan, S. Highly effective removal of phosphate from complex water environment with porous Zr-bentonite alginate hydrogel beads: Facile synthesis and adsorption behavior study. Applied Clay Science, 2021, 201, 105919. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zeng, Q.; Li, H.; Zhong, Y.; Tong, L.; Ruan, R. & Liu, H. Contribution of glycerol addition and algal–bacterial cooperation to nutrients recovery: a study on the mechanisms of microalgae-based wastewater remediation. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2020, 95(6), 1717-1728. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Xiong, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wu, H.; Yan, S. & Zhang, Z. Functional biochar fabricated from red mud and walnut shell for phosphorus wastewater treatment: Role of minerals. Environmental Research, 2023, 232, 116348. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yungang, W.; Tao, L.; Li, Z.; Yanyuan, B. & Haoran, X. High-performance sorbents from ionic liquid activated walnut shell carbon: An investigation of adsorption and regeneration. RSC advances, 2023, 13(33), 22744-22757. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/ra/d3ra03555g.

- Zanli, B. L. G. L.; Tang, W. & Chen, J. N-doped and activated porous biochar derived from cocoa shell for removing norfloxacin from aqueous solution: Performance assessment and mechanism insight. Environmental Research, 2022, 214, 113951. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Li, R.; Song, X. & Chen, B. Life cycle assessment of optimized cassava ethanol production process based on operating data from Guangxi factory in China. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2024, 14(21), 26535-26552. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-022-03442-9.

- Zhang, G.; Lei, B.; Chen, S.; Xie, H. & Zhou, G. Activated carbon adsorbents with micro-mesoporous structure derived from waste biomass by stepwise activation for toluene removal from air. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021, 9(4), 105387. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Ji, Z.; Cui, J. & Pei, Y. Solidification/stabilization of organic matter and ammonium in high-salinity landfill leachate concentrate using one-part fly ash-based geopolymers. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2023, 11(2), 109379. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, T.; Wei, W.; Zhang, W., ... & Tao, H. Magnetic biochar derived from dairy manure for peroxymonosulfate activation towards bisphenol A degradation: kinetics, electron transfer mechanism, and environmental toxicity. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2022, 50, 103314. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. ... & Zhao, J. Adsorption of Congo red and methylene blue onto nanopore-structured ashitaba waste and walnut shell-based activated carbons: Statistical thermodynamic investigations, pore size and site energy distribution studies. Nanomaterials, 2022, 12(21), 3831. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/12/21/3831.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ding, L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Kong, Y. & Ma, J. Novel sodium bicarbonate activation of cassava ethanol sludge derived biochar for removing tetracycline from aqueous solution: Performance assessment and mechanism insight. Bioresource Technology, 2021, 330, 124949. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, Q.; Li, M. & Sun, S. Preparation and water vapor adsorption of “green” walnut-shell activated carbon by CO2 physical activation. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2020, 38(1-2), 60-76. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0263617419900849.

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, H.; Xu, J.; Shi, J.; Yan, R.; Yan, N. & Guo, H. Synthesis of biomimetic N-doped porous carbons from gelatin using salt template coupled with chemical activation strategy for CO2 capture. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2025, 505, 159241. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, X. & Liu, Y. 2, 4-Dichlorophenol removal from water by walnut shells-based biochar. Desalination and Water Treatment, 2022, 252, 276-286. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Jin, Y. & Ge, M. Simple and green method for preparing copper nanoparticles supported on carbonized cotton as a heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2022, 647, 128978. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Zhong, L.; ... & Ngo, H. H. Optimized performance and mechanistic analysis of tetracycline hydrochloride removal using biochar-based alginate composite magnetic beads for peroxymonosulfate activation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2025, 115742. [CrossRef]

| PARAMETER | VALUE | SIGNIFICANCE/IMPLICATION |

|---|---|---|

| SURFACE AREA (BET) | 1,250 m²/g | Very high surface area, indicative of well-established porosity [11]. |

| TOTAL PORE VOLUME | 0.85 cm³/g | Indicates high adsorption capacity [18]. |

| PORE SIZE DISTRIBUTION | Micropores (<2 nm) | Predominance of micropores enhances adsorption selectivity for small molecules [17]. |

| Mesopores (2–50 nm) | Facilitates the diffusion and adsorption of larger contaminants, [17]. | |

| PORE STRUCTURE | Bimodal | Maximizes surface accessibility and diffusion paths, enhancing adsorption efficiency [5]. |

| ACTIVATION PROCEDURE | Hierarchical pores | Volatile fractions eliminated, creating a regulated porosity with high surface area [65]. |

| APPLICATIONS | Environmental/Industrial | Suitable for dynamic applications due to their high adsorption kinetics and capacity [62]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).