Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

2.2. Subjects and Criteria for Participation in the Study

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. The Questionnaire

2.5.1. MedDietScore Tool

2.5.2. NLS-GR Tool

2.5.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

| Sample characteristics | Participants (n=149) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 6 (4.0) |

| Female | 143 (96.0) |

| Age in years, n (%) | |

| 22-32 | 26 (17.4) |

| 33-43 | 57 (38.3) |

| 44-55 | 65 (43.6) |

| >56 | 1 (0.7) |

| Weight in Kg, Median value | 62 (55.0-71.5) |

| Height in m, Mean value (SD) | 1.64 (0.08) |

| BMI Kg/m2, Median | 23.34 (20.82-25.74) |

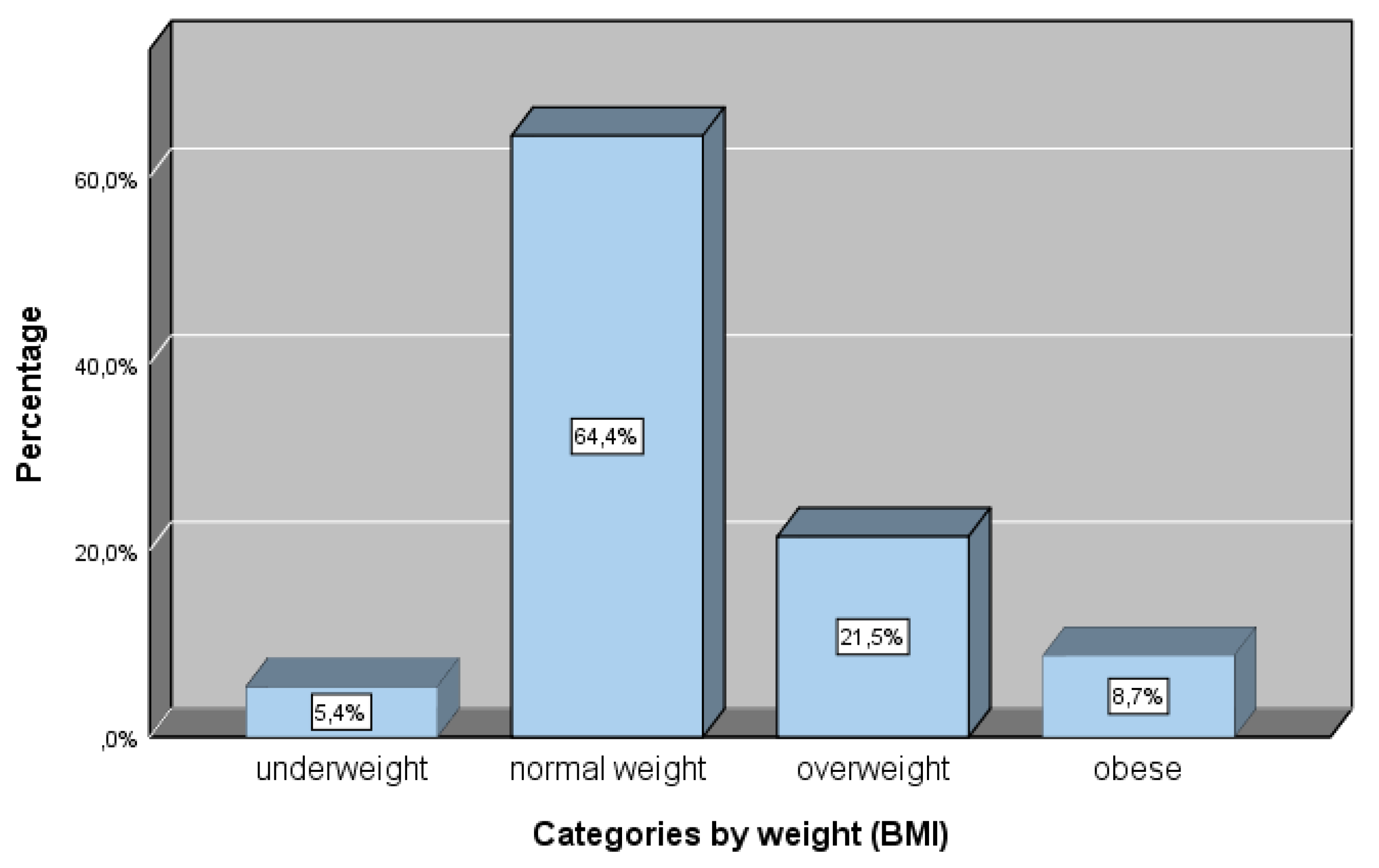

| Body weight, n (%) | |

| Underweight | 8 (5.4) |

| Normal weight | 96 (64.4) |

| Overweight | 32 (21.5) |

| Obese | 13 (8.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| B.Sc. Degree | 69 (46.3) |

| M.Sc. Student | 17 (11.4) |

| M.Sc. Degree | 57 (38.3) |

| PhDc | 4 (2.7) |

| PhD | 2 (1.3) |

| Years of teaching experience, n (%) | |

| ≤1 | 12 (8.1) |

| 1-10 | 44 (29.5) |

| 11-15 | 32 (21.5) |

| 16-20 | 29 (19.5) |

| >20 | 32 (21.5) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 31 (20.8) |

| Married | 112 (75.2) |

| Divorced | 6 (4.0) |

| Net Annual family income, n (%) | |

| <10.000 € | 29 (20.0) |

| 10.001-20.000 € | 76 (52.4) |

| 20.001-30.000 € | 27 (18.6) |

| >30.000 € | 13 (9.0) |

3.1. NLS-Gr

3.2. NLS-Gr and Association with Education, Professional Experience, Weight Classification and Family Income

3.3. NLS-Gr and Association with Food Practices and Food Waste

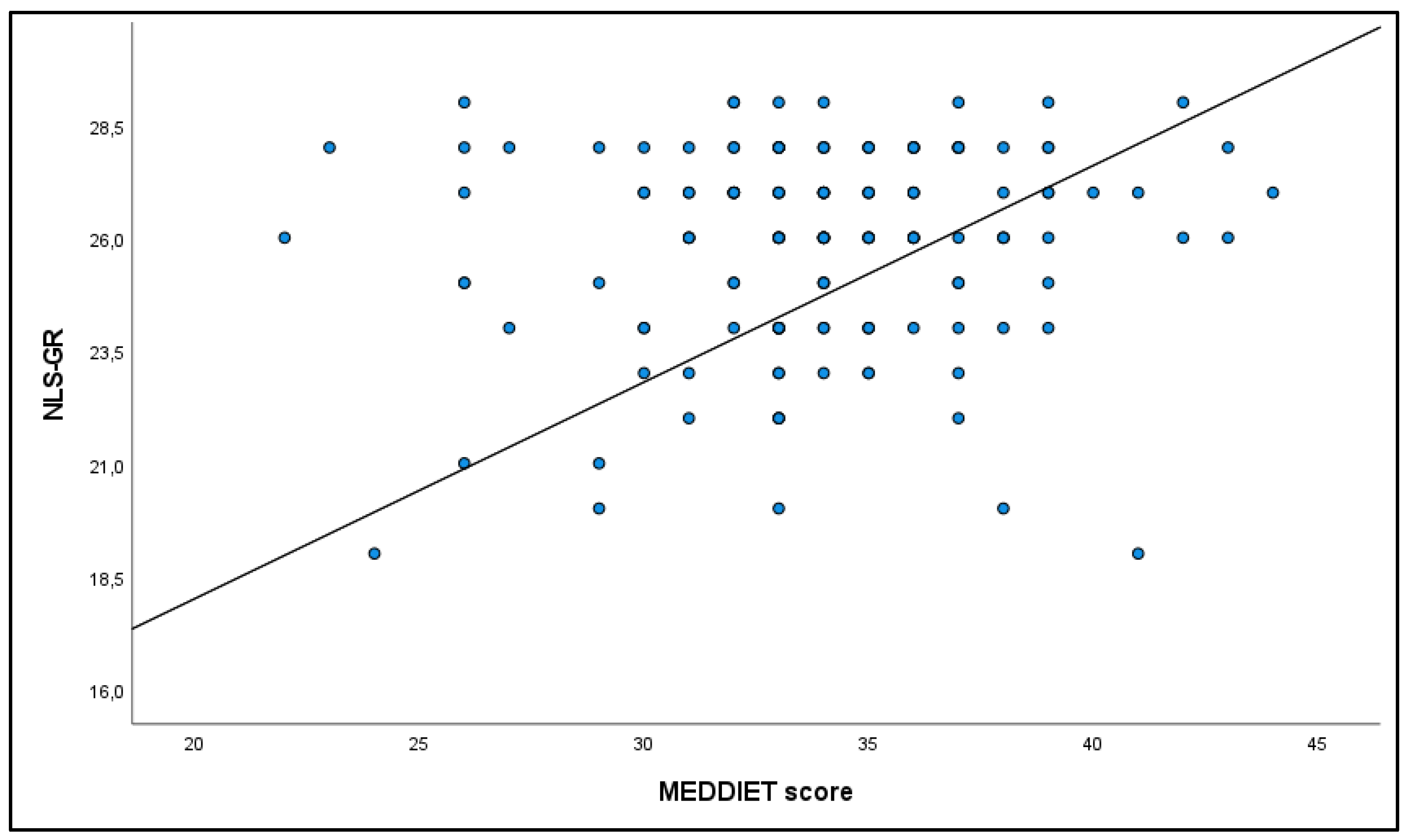

3.4. NLS-Gr and Association with Meddiet Score

3.5. NLS-Gr and Correlation with BMI

3.6. Adherence to Meddiet and Weight Categories

3.7. Correlation of Adherence to Meddiet and Physical Activity

3.8. Food Disposal Practices

| Food Disposal | ||||

|

Food Categories (n) |

Spoilage Before Consumption | Expired Date Passed | During Cooking | As Leftovers |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Milk-Yogurts (n=48) | 30 (62.5) | 27 (56.3) | 1 (2.1) | 15 (31.3) |

| Cheese(n =12) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 6 (50.0) |

| Fruits(n =43) | 29 (67.4) | 11 (25.6) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (53.5) |

| Vegetables(n =55) | 38 (69.1) | 16 (29.1) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (54.5) |

| Bread (n =41) | 17 (41.5) | 8 (19.5) | 1 (2.4) | 25 (61.0) |

| Fats-Oils (n =17) | 7 (41.2) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.8) | 13 (76.5) |

| Soft Drinks (n=13) | 10 (76.9) | 8 (61.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (53.8) |

| Desserts (n=17) | 9 (52.9) | 9 (52.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (47.1) |

| Meat (n=14) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (14.3) | 11 (78.6) |

| Chicken (n=6) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| Fish (n=2) | 2 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Eggs (n=10) | 6 (60.0) | 5 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (50.0) |

| Legumes (n=13) | 7 (53.8) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) |

| Rice-Pasta (n=23) | 7 (30.4) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 20 (87.0) |

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stewart, D.; Kennedy, A.; Pavel, A. Beyond Nutrition and Agriculture Policy: Collaborating for a Food Policy. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112 Suppl 2, S65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Trends in Underweight and Obesity from 1990 to 2022: A Pooled Analysis of 3663 Population-Representative Studies with 222 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [CrossRef]

- Change (IPCC), I.P. on C. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Cambridge University Press, 2022; pp. 1–36.

- Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association Health Literacy: Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA 1999, 281, 552–557. [CrossRef]

- Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; Washington (DC); Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A.M., Kindig, D.A., Eds.; 2004; ISBN 0-309-52926-3. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, K.J.; Sherry, J.; Winn, B.; Keesecker, N.; Horodynski, M.A.; Sayir, A. Increasing Nutrition Literacy: Testing the Effectiveness of Print, Web Site, and Game Modalities. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2008, 40, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, J.; You, W.; Connell, C.; Smith-Ray, R.L.; Allen, K.; Tucker, K.L.; Davy, B.M.; Estabrooks, P. Health Literacy Is Associated with Healthy Eating Index Scores and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake: Findings from the Rural Lower Mississippi Delta. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.K.; Sullivan, D.K.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Gajewski, B.J.; Gibbs, H.D. Nutrition Literacy Predicts Adherence to Healthy/Unhealthy Diet Patterns in Adults with a Nutrition-Related Chronic Condition. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scazzocchio, B.; Varì, R.; d’Amore, A.; Chiarotti, F.; Del Papa, S.; Silenzi, A.; Gimigliano, A.; Giovannini, C.; Masella, R. Promoting Health and Food Literacy through Nutrition Education at Schools: The Italian Experience with MaestraNatura Program. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.T.; Zoellner, J.M. Nutrition and Health Literacy: A Systematic Review to Inform Nutrition Research and Practice. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttersrud, O.; Dalane, J.Ø.; Pettersen, S. Improving Measurement in Nutrition Literacy Research Using Rasch Modelling: Examining Construct Validity of Stage-Specific “critical Nutrition Literacy” Scales. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naigaga, D.A.; Pettersen, K.S.; Henjum, S.; Guttersrud, Ø. Relating Aspects of Adolescents’ Critical Nutrition Literacy at the Personal Level. Nutrire 2021, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, D.; Rao, Y.; Reis, C.; Sharma, M.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) among Kindergarten Teachers in Chongqing, China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamos, S.; Okan, O.; Sentell, T.; Rootman, I. Making a Case for “Education for Health Literacy”: An International Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health Education and Health Promotion Revisited. Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamos, S.; Rootman, I. Health Literacy as a Lens for Understanding Non-Communicable Diseases and Health Promotion. In Global Handbook on Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion. In Global Handbook on Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion; McQueen, D.V., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-7594-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsen, H.; Sacre, Y.; Hanna-Wakim, L.; Hoteit, M. Nutrition and Food Literacy in the MENA Region: A Review to Inform Nutrition Research and Policy Makers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzinikola, C.; Papavasileiou, V. Health Literacy, Nutrition Literacy, and Food Literacy in the Context of the Social and Cultural Dimension of Sustainability. In Biodiversity, social and cultural diversity; Athens, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mourouti, N.; Michou, M.; Lionis, C.; Kalagia, P.; Ioannidis, A.G.; Kaloidas, M.; Costarelli, V. An Educational Intervention to Improve Health and Nutrition Literacy in Hypertensive Patients in Greece. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C.; Costarelli, V. Health and Nutrition Literacy in Adults: Links with Lifestyle Factors and Obesity. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 13, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costarelli, V.; Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C. Parental Health Literacy and Nutrition Literacy Affect Child Feeding Practices: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutr. Health 2022, 28, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Breda, J. School Food Research: Building the Evidence Base for Policy. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.; Watts, E.; Belson, S.I.; Snelling, A. Design and Implementation of a 5-Year School-Based Nutrition Education Intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, J.; Herd, C.; Adab, P.; Pallan, M. Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions to Prevent Obesity among Children Aged 4 to 12 Years Old in Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manios, Y.; Moschandreas, J.; Hatzis, C.; Kafatos, A. Evaluation of a Health and Nutrition Education Program in Primary School Children of Crete over a Three-Year Period. Prev. Med. 1999, 28, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzinikola, C.; Papavasileiou, V. Educational Policy of Nutrition in Preschool Age: Comparative Analysis of Greece, USA and Sweden.; Patra, November 1 2019.

- Hawkins, M.; Watts, E.; Belson, S.I.; Snelling, A. Design and Implementation of a 5-Year School-Based Nutrition Education Intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelling, A.; Ernst, J.; irvine belson, S. Teachers as Role Models in Solving Childhood Obesity. J. Pediatr. Biochem. 2016, 03, 055–060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelling, A.; Hawkins, M.; McClave, R.; Irvine Belson, S. The Role of Teachers in Addressing Childhood Obesity: A School-Based Approach. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfil, M.; Negida, A. Sampling Methods in Clinical Research; an Educational Review. Emerg. Tehran Iran 2017, 5, e52. [Google Scholar]

- Sudershan, A.; Mahajan, K.; Panjaliya, R.K.; Dhar, M.K.; Kumar, P. Algorithm for Sample Availability Prediction in a Hospital-Based Epidemiological Study Spreadsheet-Based Sample Availability Calculator. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Taljaard, M.; Moerbeek, M.; Forbes, A. Contamination: How Much Can an Individually Randomized Trial Tolerate? Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 3329–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killip, S.; Mahfoud, Z.; Pearce, K. What Is an Intracluster Correlation Coefficient? Crucial Concepts for Primary Care Researchers. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordzij, M.; Tripepi, G.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C.; Tanck, M.W.; Jager, K.J. Sample Size Calculations: Basic Principles and Common Pitfalls. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2010, 25, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutterford, C.; Copas, A.; Eldridge, S. Methods for Sample Size Determination in Cluster Randomized Trials. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Stefanadis, C. Dietary Patterns: A Mediterranean Diet Score and Its Relation to Clinical and Biological Markers of Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. NMCD 2006, 16, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magriplis, E.; Panagiotakos, D.; Mitsopoulou, A.-V.; Karageorgou, D.; Bakogianni, I.; Dimakopoulos, I.; Micha, R.; Michas, G.; Chourdakis, M.; Chrousos, G.P.; et al. Prevalence of Hyperlipidaemia in Adults and Its Relation to the Mediterranean Diet: The Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos, D.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Pitsavos, C.; Roussinou, G.; Palliou, K.; Chrysohoou, C.; Stefanadis, C. Validation of the MedDietScore via the Determination of Plasma Fatty Acids. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60 Suppl 5, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Arvaniti, F.; Stefanadis, C. Adherence to the Mediterranean Food Pattern Predicts the Prevalence of Hypertension, Hypercholesterolemia, Diabetes and Obesity, among Healthy Adults; the Accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza-Martí, A.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.; Hurtado-Sánchez, J.; Laguna-Pérez, A.; Ferrer-Cascales, R. Evaluation of Mediterranean Diet Adherence Scores: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.J. Development of a Reliable and Construct Valid Measure of Nutritional Literacy in Adults. Nutr. J. 2007, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Mamalaki, E.; Yannakoulia, M.; Costarelli, V. Development and Validation of the Greek Version of the Comprehensive Parental Feeding Questionnaire. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 12, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, H.; Ferreira Carioca, A.A.; Sabry, S.D.; Sabry, M.O.D.; Pinto, F.; Ellery, T. Assessment of Nutrition Literacy by Two Diagnostic Methods in a Brazilian Sample. Nutr. Clin. Diet. Hosp. 2014, 34, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, M.; Costarelli, D.; Panagiotakos, D. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Relation to Health and Nutrition Literacy in Greece. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. (in press). 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.; Lionis, C.; Petelos, E.; Costarelli, V. Health & Nutrition Literacy Levels in Greek Adults with Chronic Disease. WHO Reg. Publ. Eur. Ser. Public Health Panorama, in press. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aureli, V.; Rossi, L. Nutrition Knowledge as a Driver of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Italy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 804865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpini, B.; Vaccaro, G.; Vettori, V.; Lorini, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. What Is the Impact of Nutrition Literacy Interventions on Children’s Food Habits and Nutrition Security? A Scoping Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, D.; Rao, Y.; Reis, C.; Sharma, M.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) among Kindergarten Teachers in Chongqing, China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsagoni, C.N.; Apostolou, A.; Georgoulis, M.; Psarra, G.; Bathrellou, E.; Filippou, C.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Sidossis, L.S. Schoolteachers’ Nutrition Knowledge, Beliefs, and Attitudes Before and After an E-Learning Program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullerton, K.; Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. A Review of Food Literacy Interventions Targeting Disadvantaged Young People.; 2012.

- Kawasaki, Y.; Akamatsu, R. Appreciation for Food, an Important Concept in Mindful Eating: Association with Home and School Education, Attitude, Behavior, and Health Status in Japanese Elementary School Children. Glob. Health Promot. 2020, 27, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorca-Camara, V.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Bach-Faig, A. Environmental and Health Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. Bethesda Md 2024, 15, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEP NEW SCHOOL (21st Century School) – New Curriculum Subproject 1, Development of Compulsory Education Curricula", Scientific Field: Early School Age, Kindergarten Curriculum: Athens 2014.

- Snelling, A.; Hawkins, M.; McClave, R.; Irvine Belson, S. The Role of Teachers in Addressing Childhood Obesity: A School-Based Approach. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Scientific Supervisor: Athina Linou National Dietary Guide for Infants, Children, and Adolescents; Prolepsis – Institute of Preventive, Environmental and Occupational Medicine, 2014.

- Ministerial Decision F.31/94185/D1, 29-7-2021, Skill Labs in Primary Education, in Government Gazette, 3791/Β/13-8-2021.

- Amahmid, O.; Guamri, Y.; Rakibi, Y.; Mohamed, Y.; Bouchra, R.; Rassou, K.; Boukaoui, S.; Izerg, O.; Belghyti, D. Nutrition Education in School Curriculum: Impact on Adolescents’ Attitudes and Dietary Behaviours. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, G.C.B.S. de; Azevedo, K.P.M. de; Garcia, D.; Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Mata, Á.N. de S.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; Santos, R.P.D.; Trindade, D.D.B. de B.; Moreno, I.M.; Guillén Martínez, D.; et al. Effect of School-Based Food and Nutrition Education Interventions on the Food Consumption of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a Subtle Difference? Findings from a Systematic Review on Definitions of Nutrition Literacy and Food Literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining Food Literacy and Its Components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a Subtle Difference? Findings from a Systematic Review on Definitions of Nutrition Literacy and Food Literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Costarelli, V.; Chroni, C. The Implications of Food Waste Generation on Climate Change: The Case of Greece. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer Behaviour and Household Food Waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Food Waste Index Report 2021; Nairobi, 2021.

- Aloysius, N.; Ananda, J.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Why People Are Bad at Leftover Food Management? A Systematic Literature Review and a Framework to Analyze Household Leftover Food Waste Generation Behavior. Appetite 2023, 186, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.T.; Papanikolaou, P.-A.; Katimertzoglou, P.; Ntalla, A.C.; A.C., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Xenos Konstantinos, I. Household Food Waste in Greece: A Questionnaire Survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liz Martins, M.; Rodrigues, S.S.P.; Cunha, L.M.; Rocha, A. Factors Influencing Food Waste during Lunch of Fourth-Grade School Children. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Food Waste Index Report 2021. 2021.

- Buzby, J.; Wells, H.; Hyman, J. The Estimated Amount, Value, and Calories of Postharvest Food Losses at the Retail and Consumer Levels in the United States. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, N.; Ananda, J.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Why People Are Bad at Leftover Food Management? A Systematic Literature Review and a Framework to Analyze Household Leftover Food Waste Generation Behavior. Appetite 2023, 186, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Quantifying Household Waste of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables in the EU. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Figueroa-Torres, G.; Azapagic, A. The Extent of Food Waste Generation in the UK and Its Environmental Impacts. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, F.; Capone, R.; Yannakoulia, M.; Dernini, S.; Hwalla, N.; Kalaitzidis, C. The Mediterranean Diet: A Sustainable Consumption Pattern. In Zero waste in the Mediterranean Natural Resources, Food and Knowledge; Paris, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity; Baku, 2013.

- Allison, C.; Colby, S.; Opoku-Acheampong, A.; Kidd, T.; Kattelmann, K.; Olfert, M.D.; Zhou, W. Accuracy of Self-Reported BMI Using Objective Measurement in High School Students. J. Nutr. Sci. 2020, 9, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Correct answers of the Greek NLS by percentage | N (%) |

| Healthy eating is really supposed to help our hearts. | 146 (98.0) |

| However, no single food can supply all the nutrients we need. | 114 (76.5) |

| Eating a variety of foods ensures you get all the nutrients needed for good health. | 145 (97.3) |

| Grains, fruits, and vegetables are food groups that form the basis of a healthy diet. | 98 (65.8) |

| For a healthy diet, we are advised to eat five servings of fruits | 137 (91.9) |

| and vegetables each day. | 143 (96.0) |

| Foods like butter have a lot of saturated fat, which can increase cholesterol. | 145 (97.3) |

| We also know that cholesterol can be affected by foods high in trans fatty acids. | 125 (83.9) |

| Experts often say to avoid foods high in trans fatty acids | 147 (98.7) |

| because they are fattening. | 147 (98.7) |

| Obesity increases the risk of diseases such as diabetes. | 146 (98.0) |

| Fiber is the part of plant-based foods that your body does not digest and absorb. | 142 (95.3) |

| Whole grains provide more fiber than processed grains. | 133 (89.3) |

| A good diet should contain approximately 25–30 grams of fiber a day. | 131 (87.9) |

| Calcium is essential for bone health | 149 (100.0) |

| As you age, your bones may get thinner as minerals are lost. | 106 (71.1) |

| Even in older people, vitamin D is needed to keep bones healthy. | 148 (99.3) |

| Foods with added sugars are sometimes called foods with empty calories. | 97 (65.1) |

| To prevent illness from bacteria | 124 (83.2) |

| keep eggs in the refrigerator. | 147 (98.7) |

| Farmers who grow organic foods don’t use conventional methods. | 137 (91.9) |

| They control weeds by techniques such as crop rotation rather than pesticides. | 135 (90.6) |

| For this and other reasons, organic food costs more than conventional food. | 118 (79.2) |

| A 180-calorie serving with 10 grams of fat has 50% of its calories from fat. | 148 (99.3) |

| A 140-pound (64 kg) woman needs about 51 grams of protein daily. | 143 (96.0) |

| Using fat-free mayonnaise on a sandwich can reduce the grams of fat. | 107 (71.8) |

| My doctor told me that “fat-free” is not the same as calorie-free. | 138 (92.6) |

| She also told me to make the size of my portions smaller | 132 (88.6) |

| to help control my weight. | 127 (85.2) |

| Nutrition literacy /NLS-Gr | ||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | p-value | |

| Educational level | 0.925 | |

| University Degree (BSc) | 26 (24-28) | |

| Postgraduate Student | 26 (24-27) | |

| Postgraduate Degree Holder | 26 (24-27) | |

| PhD Candidate & Doctorate Holder | 26.5 (24.5-28) | |

| Years of Teaching Experience | ||

| ≤1 | 25.5 (24-27) | 0.192 |

| 1-10 | 26 (24-27) | |

| 11-15 | 27 (26-27) | |

| 16-20 | 27 (24.5-28) | |

| >20 | 26 (25.3-28) | |

| Classification Based on BMI, N (%) | ||

| Underweight | 24.5 (24-27) | 0.227 |

| Normal Weight | 26.0 (24.3-27) | |

| Overweight | 27 (25.3-28) | |

| Obese | 26 (24-27) | |

| Net Annual Family Income | ||

| <10.000 € | 25 (23.5-27) | 0.048* |

| 10.001-20.000 € | 27 (25-28) | |

| 20.001-30.000 € | 26 (24-28) | |

| >30.000 € | 26 (26-27.5) |

| Nutrition literacy/NLS-Gr | ||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | p-value | |

| Meal Planning | 0.017* | |

| No | 25.5 (24-27) | |

| Yes | 27 (25-28) | |

| Shopping List | 0.976 | |

| No | 26.5 (24.0-27.8) | |

| Yes | 26 (24-28) | |

| Storage of fruits and vegetables in the refrigerator | 0.438 | |

| No | 25.5 (24.0-27.3) | |

| Yes | 26 (24-28) | |

| Food disposal | 0.167 | |

| never or almost never | 27 (25-28) | |

| rarely (a few times a year) | 26 (24-27) | |

| sometimes (a few times a month) | 27 (24-28) | |

| often (a few times a week) | 26 (23.3-27.0) | |

| always (daily) - | - | |

| Organic food consumption | 0.525 | |

| No | 26 (24.0-27.5) | |

| Yes | 26.5 (24-28) | |

| Composting food waste | 0.359 | |

| No | 26 (24-28) | |

| Yes | 26 (23.5-27.0) |

| rs | p-value* | |

| Spearman’s correlation coefficient | 0.1 (-0.1, 0.3) | 0.202 |

| Spearman | rs (95% CI) | p-value |

| BMI – NLS-Gr | 0.03 (-0.1, 0.2) | 0.764 |

|

NLS-Gr, median (Q1-Q3) |

Underweight | Normal | Overweight | Obese | p-value* |

| 24.5 (24-27) | 26 (24.3-27.0) | 27 (25.3-28) | 26 (24-27) | 0.227 |

| Physical activity & Sedentary lifestyle | |||

|

MedDiet score, Frequency of consumption/week rs (95% CI) p-value |

Sedentary lifestyle (hours, weekdays) | Sedentary lifestyle (hours weekends) | Average exercise /per day |

| whole grains | 0.9 (0.8,0.9) <0.001 |

0.0 (-0.1,0.2) 0.639 |

0.2 (0.1,0.4) 0.009 |

|

potatoes |

0.0 (-0.1,0.2) 0.780 |

0.0 (-0.2,0.2) 0.798 |

0 (-0.2,0.2) 0.933 |

|

fruits |

0.3 (0.1,0.4) 0.002 |

-0.1 (-0.3,0.1) 0.171 |

0.2 (0.1,0.4) 0.009 |

|

vegetables |

0.3 (0.2,0.5) <0.001 |

-0.1 (-0.3,0.1) 0.313 |

0.1 (0.0,0.3) 0.087 |

|

legumes |

0.1 (0.0,0.3) 0.093 |

0.0 (-0.2,0.2) 0.861 |

0.1 (0.0,0.3) 0.105 |

|

fish and seafood |

0.1 (-0.1,0.3) 0.181 |

-0.1 (-0.3,0.0) 0.083 |

0.2 (0.0,0.3) 0.067 |

|

red meat and meat products |

0.2 (0.0,0.3) 0.064 |

-0.1 (-0.2,0.1) 0.502 |

0.2 (0.0,0.3) 0.055 |

|

poultry |

0.0 (-0.1,0.2) 0.655 |

0.0 (-0.1,0.2) 0.597 |

-0.1 (-0.3,0.1) 0.210 |

|

diary full fat |

-0.2 (-0.3,0.0) 0.026 |

-0.2 (-0.3,0.0) 0.068 |

-0.2 (-0.3,0.0) 0.078 |

|

olive oil |

-0.2 (-0.3, -0.02) 0.025 |

0.1 (-0.1,0.2) 0.307 |

0.0 (-0.2,0.2) 0.868 |

|

alcohol |

-0.1(-0.3,0.1) 0.291 |

0.0 (-0.2,0.1) 0.679 |

-0.2 (-0.3,0.0) 0.057 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).