Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Role of Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) in Chronic Diseases

2.1. Involvement of UPS in Neurodegenerative Diseases (NDs)

2.2. Involvement of UPS in Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)

2.3. Involvement of UPS in Cancer

3.1. UPS Modulators

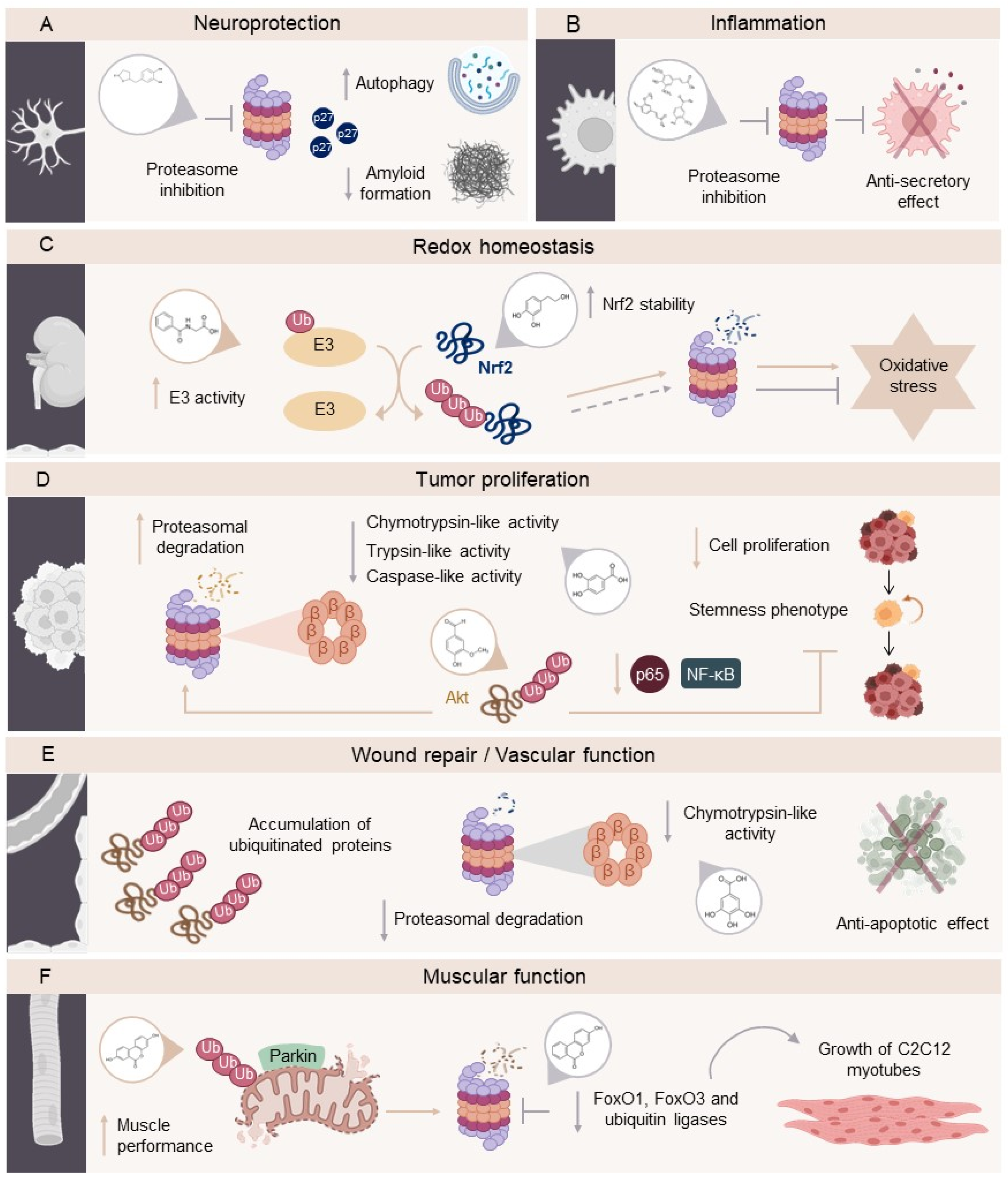

3.2. The Role of (Poly)phenols in Modulating the UPS

3.3. Metabolism and Bioavailability of Dietary (Poly)phenols

3.4. Phenolic Metabolites as Potential UPS Modulators in Chronic Diseases

| Model |

Dose/ Duration |

Mechanism of action | Main outcomes | Reference |

| Valerolactone derivatives | ||||

| 5-(4ʹ-hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone | ||||

| In silico | - | Binding with β1, β2, and β5 subunits of human constitutive 20S proteasome (pdb ID: 6rgq). Binding with β1i, β2i, and β5i subunits of human immunoproteasome (pdb ID: 6e5b). |

Moderate binding affinity for proteasome catalytic subunits. | [105] |

| Cell-free | 0 ̶ 10 µM for 90 min | Inhibits catalytic subunits of proteasome at 10 µM: - Chymotrypsin-like (ChT-L) and branched chain amino acids preferring (BrAAP) (associated with the β5 subunit). - Trypsin-like (T-L) (β2 subunit). - Peptidyl glutamyl-peptide hydrolyzing (PGPH) (β1 subunit). |

Proteasome inhibition promoting autophagy activation. | [105] |

| Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 1 ̶ 5µM for 24h | Strongly affects the functionality of enzymatic complex, mainly catalytic subunit ChT-L of both 20S and 26S proteasome. Increases the levels of Ub-conjugates and p27. |

Affect the functionality of proteosomal enzymatic complex. Decrease in amyloid formation. |

[105] |

| 5-(3ʹ,4ʹ-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone | ||||

| In silico | - | Binding with β1, β2, and β5 subunits of human constitutive 20S proteasome (pdb ID: 6rgq) Binding with β1i, β2i, and β5i subunits of human immunoproteasome (pdb ID: 6e5b). |

Moderate binding affinity for proteasome catalytic subunits. | [105] |

| Cell-free | 0 ̶ 10 µM for 90 min | Inhibits catalytic subunits of proteasome at 10 µM: - ChT-L and BrAAP (associated with the β5 subunit). - T-L (β2 subunit). - PGPH (β1 subunit). |

Proteasome inhibition promotes autophagy activation. |

[105] |

| Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 1 ̶ 5µM for 24h | Low affectation in the enzymatic complex (ChT-L of both 20S and 26S proteasome). | Proteasome inhibition promotes autophagy activation. Decrease in amyloid formation. | [105] |

| 5-(3ʹ-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone-4ʹ-sulfate | ||||

| In silico | - | Binding with β1, β2, and β5 subunits of human constitutive 20S proteasome (pdb ID: 6rgq). Binding with β1i, β2i, and β5i subunits of human immunoproteasome (pdb ID: 6e5b). |

Moderate binding affinity for proteasome catalytic subunits. | [105] |

| Cell-free | 0 ̶ 10 µM for 90 min | Inhibits catalytic subunits of proteasome at 10 µM: - ChT-L and BrAAP (associated with the β5 subunit). - T-L (β2 subunit). - PGPH (β1 subunit). |

Proteasome inhibition. Promotes autophagy activation. |

[105] |

| Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 1 ̶ 5µM for 24h | Strongly affects the functionality of enzymatic complex, mainly ChT-L of both 20S and 26S proteasome. | Affectation the functionality of proteosomal enzymatic complex. Decrease in amyloid formation. |

[105] |

| Benzoic acid derivatives | ||||

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | ||||

| In silico | - | Binding with pro-cathepsin B (PDBid: 2PBH) and pro-cathepsin L (PDBid: 1CS8). | Binders of both procathepsin B and L, and thus suggest a likely direct effect on cathepsins activity, which enhances the activity of UPS system. | [114] |

| Human foreskin fibroblast cells | 5 μM for 24h | Proteasome proteolytic activities on ChT-L (β5 subunit) and caspase-like (C-L) (β1 subunit). | ↑Activity of the two main cell protein degradation systems, namely ALP and UPS and especially the activity of cathepsins B and L. | [114] |

| 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (Protocatechuic acid) | ||||

| Balb/c mice with tumors induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate | 16 μM in 0.2 mL of acetone topical application | Reduction of 20S proteasome trypsin-like (T-L) activity. | Suppression of proteasome 20S activities in mouse epidermis. Affect several key events of initiation and the promotion stage of carcinogenesis |

[111] |

| 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid (Gallic acid) | ||||

| EA.hy926 human cardiovascular endothelial cell and HBEC-5i human cerebrovascular endothelial cells | Pretreatment (before cell death induced by homocysteine, adenosine and TNFα) 1 ̶ 100 μM for 4h | Accumulation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates and ↓ in ChT-L (β5 subunit) proteasome activities. | ↓Cytotoxicity . Reversed DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) depletions at the protein level. Anti-apoptotic effects. ↓Microparticle formation and proteasome activity inhibition. |

[116] |

| 4-methoxybenzoic acid | ||||

| In silico | - | Binding with pro-cathepsin B (PDBid: 2PBH) and pro-cathepsin L (PDBid: 1CS8). | Binders of both procathepsin B and L, and thus suggest a likely direct effect on cathepsins activity, which enhances the activity of UPS system. | [114] |

| Human foreskin fibroblast cells | 5 μM for 24h | Proteasome proteolytic activities on ChT-L (β5 subunit) and caspase-like (C-L) (β1 subunit). | ↑Activity of the two main cell protein degradation systems, namely ALP and UPS and especially the activity of cathepsins B and L. | [114] |

| 2,4,5-Trimethoxybenzoic acid (Asaronic acid) | ||||

| J774A.1 murine macrophage cells | 1 ̶ 20 μM up to 24h | ↑UPS degradation of non-native proteins dislocated to the cytosol. | ↓Oxysterol-induced expression of EDEM1, OS9, Sel1L-Hrd1 and p97/VCP1 Activation of the ER stress sensors of ATF6, IRE1 and PERK stimulated by 7β-hydroxycholesterol. |

[107] |

| 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid (vanillic acid) | ||||

| Raw 264.7 macrophage cells | 10 ̶ 100 μM for 60 min | Blocking the proteasome through inhibition of ChT-L activity. | Inhibition of proteasome activity. | [106] |

| 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid (syringic acid) | ||||

| In silico | - | Eukaryotic yeast 20S proteasome crystal structure (PDB code: 2 F16). | Good affinity of syringic acid and different proposed derivatives. | [112] |

| Benzaldehyde derivatives | ||||

| 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (vanillin) | ||||

| Human non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H460 | 0 ̶ 50 μM for 1 or 3 days | Akt degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. | Downregulation of different cancer stem cells markers (CD133, ALDH1A1) and transcription factors (Oct4 and Nanog). Akt-proteasomal degradation. |

[109] |

| Six-week-old BALB/c mice with colitis-associated colon cancer | 10, 50, and 100 mg/kg in distilled water for 13 weeks | ↓ Proteasome expression in colon tissues (Proteasome β5 subunit) and ↓ Psma1, Psma4, Psmb2, Psmb5, Psmb9, Psmb10, Psmc4, Psmd3, Psmd8 gene expression. | ↓ Tumor number and growth. Affects gene expression profiles of six biological pathways involved in protein folding and degradation (proteasome and ER-associated degradation), transcription (spliceosome), immune system (Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis), cell motility (regulation of actin cytoskeleton), and glycan metabolism (N-glycan biosynthesis) |

[110] |

| Human colorectal cancer HCT-116 cells | 0.01 ̶ 10000 µM for 2h | ↓ Proteasome β5 activity. | Inhibition of proteasome activity. | [110] |

| 3′,4′-dihydroxycinnamic acid (caffeic acid) | ||||

| Cerebellar granule neurons isolated from Sprague-Dawley rats | 50 µM for 24h | Blocking of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341, which causes cell death | ↓Oxidative and nitrosative stress and excitotoxicity. Protection against intrinsic apoptosis and proteasome inhibition. |

[113] |

| 4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid (ferulic acid) | ||||

| Raw 264.7 macrophage cells | 10 ̶ 100 μM for 60 min | No affectation of proteasome activity via ChT-L. | ↓ NO production. No inhibition of proteasome activity. |

[106] |

| Cerebellar granule neurons isolated from Sprague-Dawley rats | 50 µM for 24h | No effects on blocking the proteasome inhibitor PS-341, which causes cell death. | Significantly protected neurons from excitotoxicity and glutamate-induced cell death, independent of proteasome inhibition. | [113] |

| 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxycinnamic acid (sinapic acid) | ||||

| Raw 264.7 macrophage cells | 10 ̶ 100 μM/ 60 minutes | No affectation of proteasome activity via ChT-L. | ↓ NO production. No inhibition of proteasome activity. |

[106] |

| Phenylacetic acid derivatives | ||||

| 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) | ||||

| Untreated rabbit reticulocyte lysate | 0.19 mM for 30, 60 and 180 min | Protective role for NQO1 in protecting against dopamine-induced proteasomal inhibition. | Inhibition of proteasome activity. | [115] |

| Hippuric acid derivatives | ||||

| Hippuric acid | ||||

| Human renal proximal tubule HK-2 cells | 0 ̶ 1000 µM for 24h | ↑E3 ubiquitin activity ligase by strengthening the NRF2–KEAP1–CUL3 interactions. ↑NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation by 26S proteosome. |

Disruption of redox homeostasis by NRF2 antioxidant activity. | [108] |

| Urolithin derivatives | ||||

| Urolithin A | ||||

| Vastus lateralis skeletal muscle from overweight adults (n=88) | 500 mg oral daily dose for 4 months | Increases the levels of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and proteasomal components, which are required for Parkin-mediated degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria and damaged proteins. | Improvement of muscle performance. | [118] |

| C2C12 murine skeletal muscle myoblasts | 15 μM for 24h |

Prevents the activation of NF-kB signalling and ubiquitin proteasome pathway. | No affectation on differentiation of C2C12 myotubes. | [117] |

| Urolithin B | ||||

| C2C12 murine skeletal muscle myoblasts | 15 μM for 24h |

Represses UPS through downregulation of transcription factors (FoxO1 and FoxO3) and ubiquitin ligases (MAFbx and MuRF1). | Enhances the growth and differentiation of C2C12 myotubes. Potential for treatment of muscle mass loss. Decreases protein degradation rate. |

[117] |

| Twelve-week-old C57/Bl6 J | 10 μg/day (subcutaneous) for 28 days | ↑p-mTOR. | ↑Muscle hypertrophy and ↓muscle atrophy after the sciatic nerve section. | [117] |

4. Conclusions and Existing Gaps to Address in the Future

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet 2014;384:45–52. [CrossRef]

- Helgeson VS, Zajdel M. Adjusting to Chronic Health Conditions. Annu Rev Psychol 2017;68:545–71. [CrossRef]

- Shelton RC, Philbin MM, Ramanadhan S. Qualitative Research Methods in Chronic Disease: Introduction and Opportunities to Promote Health Equity. Annu Rev Public Health 2022;43:37–57. [CrossRef]

- Kassis A, Fichot M-C, Horcajada M-N, Horstman AMH, Duncan P, Bergonzelli G, et al. Nutritional and lifestyle management of the aging journey: A narrative review. Front Nutr 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt M, Finley D. Regulation of proteasome activity in health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2014;1843:13–25. [CrossRef]

- Dunker AK, Silman I, Uversky VN, Sussman JL. Function and structure of inherently disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2008;18:756–64. [CrossRef]

- Balchin D, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science (1979) 2016;353. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj GG, Hipp MS, Hartl FU. Functional Modules of the Proteostasis Network. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2020;12:a033951. [CrossRef]

- Höhn A, Tramutola A, Cascella R. Proteostasis Failure in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020;2020:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Dikic I. Proteasomal and Autophagic Degradation Systems. Annu Rev Biochem 2017;86:193–224. [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M. Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:1006–15. [CrossRef]

- Chiavaroli L, Nishi SK, Khan TA, Braunstein CR, Glenn AJ, Mejia SB, et al. Portfolio Dietary Pattern and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2018;61:43–53. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen NB, Lambert MNT, Jeppesen PB. The Effect of Plant Derived Bioactive Compounds on Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020;64. [CrossRef]

- Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Third Expert Report on Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: Impact and Future Directions. J Nutr 2020;150:663–71. [CrossRef]

- Amiot MJ, Riva C, Vinet A. Effects of dietary polyphenols on metabolic syndrome features in humans: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews 2016;17:573–86. [CrossRef]

- Tresserra-Rimbau A, Rimm EB, Medina-Remón A, Martínez-González MA, de la Torre R, Corella D, et al. Inverse association between habitual polyphenol intake and incidence of cardiovascular events in the PREDIMED study. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2014;24:639–47. [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ros R, Knaze V, Rothwell JA, Hémon B, Moskal A, Overvad K, et al. Dietary polyphenol intake in Europe: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Eur J Nutr 2016;55:1359–75. [CrossRef]

- Rienks J, Barbaresko J, Nöthlings U. Association of polyphenol biomarkers with cardiovascular disease and mortality risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2017;9:415.

- Kishimoto Y, Tani M, Kondo K. Pleiotropic preventive effects of dietary polyphenols in cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013;67:532–5. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Guo MS, Zhang Y, Yu L, Wu JM, Tang Y, et al. Dietary Plant Polyphenols as the Potential Drugs in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Evidence, Advances, and Opportunities. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022;2022. [CrossRef]

- Manasanch EE, Orlowski RZ. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:417–33. [CrossRef]

- Collins GA, Goldberg AL. The Logic of the 26S Proteasome. Cell 2017;169:792–806. [CrossRef]

- Andersson V, Hanzén S, Liu B, Molin M, Nyström T. Enhancing protein disaggregation restores proteasome activity in aged cells. Aging 2013;5:802–12. [CrossRef]

- Tsakiri EN, Trougakos IP. Chapter Five - The Amazing Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Structural Components and Implication in Aging. In: Jeon KW, editor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol, vol. 314, Academic Press; 2015, p. 171–237. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan S, Guo JL, Changolkar L, Stieber A, McBride JD, Silva L V., et al. Pathological Tau Strains from Human Brains Recapitulate the Diversity of Tauopathies in Nontransgenic Mouse Brain. The Journal of Neuroscience 2017;37:11406–23. [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner G, Eisele YS, Langer F, Kaeser SA, Novotny R, Nagarathinam A, et al. Seeded strain-like transmission of β-amyloid morphotypes in APP transgenic mice. EMBO Rep 2013;14:1017–22. [CrossRef]

- Smith DM. Could a Common Mechanism of Protein Degradation Impairment Underlie Many Neurodegenerative Diseases? J Exp Neurosci 2018;12. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P. Role of Oxidative Stress, ER Stress and Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Neurodegeneration. MOJ Cell Science & Report 2014;1. [CrossRef]

- Nedelsky NB, Todd PK, Taylor JP. Autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: Collaborators in neuroprotection. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2008;1782:691–9. [CrossRef]

- Cheng B, Martinez AA, Morado J, Scofield V, Roberts JL, Maffi SK. Retinoic acid protects against proteasome inhibition associated cell death in SH-SY5Y cells via the AKT pathway. Neurochem Int 2013;62:31–42. [CrossRef]

- Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The Roles of PINK1, Parkin, and Mitochondrial Fidelity in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 2015;85:257–73. [CrossRef]

- Itier J-M, Ibanez P, Mena MA, Abbas N, Cohen-Salmon C, Bohme GA, et al. Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:2277–91.

- Setsuie R, Wang Y-L, Mochizuki H, Osaka H, Hayakawa H, Ichihara N, et al. Dopaminergic neuronal loss in transgenic mice expressing the Parkinson’s disease-associated UCH-L1 I93M mutant. Neurochem Int 2007;50:119–29. [CrossRef]

- Marshall RS, Vierstra RD. Dynamic Regulation of the 26S Proteasome: From Synthesis to Degradation. Front Mol Biosci 2019;6. [CrossRef]

- LAN D, WANG W, ZHUANG J, ZHAO Z. Proteasome inhibitor-induced autophagy in PC12 cells overexpressing A53T mutant α-synuclein. Mol Med Rep 2015;11:1655–60. [CrossRef]

- Ghavami S, Shojaei S, Yeganeh B, Ande SR, Jangamreddy JR, Mehrpour M, et al. Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Neurobiol 2014;112:24–49. [CrossRef]

- Dantuma NP, Bott LC. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: precipitating factor, yet part of the solution. Front Mol Neurosci 2014;7. [CrossRef]

- Press M, Jung T, König J, Grune T, Höhn A. Protein aggregates and proteostasis in aging: Amylin and β-cell function. Mech Ageing Dev 2019;177:46–54. [CrossRef]

- Lee B-H, Lee MJ, Park S, Oh D-C, Elsasser S, Chen P-C, et al. Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature 2010;467:179–84. [CrossRef]

- Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WHD, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to Destroy. Circ Res 2010;106:463–78. [CrossRef]

- Iso T, Hamamori Y, Kedes L. Notch Signaling in Vascular Development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:543–53. [CrossRef]

- de Moissac D, Mustapha S, Greenberg AH, Kirshenbaum LA. Bcl-2 Activates the Transcription Factor NFκB through the Degradation of the Cytoplasmic Inhibitor IκBα. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998;273:23946–51. [CrossRef]

- FOLCO JE, KOREN G. Degradation of the inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Biochemical Journal 1997;328:37–43. [CrossRef]

- Eble DM, Spragia ML, Ferguson AG, Samarel AM. Sarcomeric myosin heavy chain is degraded by the proteasome. Cell Tissue Res 1999;296:541. [CrossRef]

- Taylor RG, Tassy C, Briand M, Robert N, Briand Y, Ouali A. Proteolytic activity of proteasome on myofibrillar structures. Mol Biol Rep 1995;21:71–3. [CrossRef]

- Gong Q, Keeney DR, Molinari M, Zhou Z. Degradation of Trafficking-defective Long QT Syndrome Type II Mutant Channels by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005;280:19419–25. [CrossRef]

- Waxman AJ, Clasen S, Hwang W-T, Garfall A, Vogl DT, Carver J, et al. Carfilzomib-Associated Cardiovascular Adverse Events. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e174519. [CrossRef]

- Laine A, Ronai Z. Ubiquitin Chains in the Ladder of MAPK Signaling. Science’s STKE 2005;2005. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi J, Furukawa Y, Kubo N, Tokura A, Hayashi N, Nakamura M, et al. Induction of Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme by Aggregated Low Density Lipoprotein in Human Macrophages and Its Implications for Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:128–34. [CrossRef]

- VIEIRA O, ESCARGUEIL-BLANC I, JÜRGENS G, BORNER C, ALMEIDA L, SALVAYRE R, et al. Oxidized LDLs alter the activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: potential role in oxidized LDL-induced apoptosis. The FASEB Journal 2000;14:532–42. [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger KJ. Differential effects of low density lipoproteins on IGF-1 and IGF-1R expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000. [CrossRef]

- Higashi Y, Sukhanov S, Parthasarathy S, Delafontaine P. The ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 mediates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced downregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2008;295:H1684–9. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi N, Vogel SN, Van Way C, Papasian CJ, Qureshi AA, Morrison DC. The Proteasome: A Central Regulator of Inflammation and Macrophage Function. Immunol Res 2005;31:243–60. [CrossRef]

- Marfella R, D’Amico M, Di Filippo C, Baldi A, Siniscalchi M, Sasso FC, et al. Increased Activity of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Patients With Symptomatic Carotid Disease Is Associated With Enhanced Inflammation and May Destabilize the Atherosclerotic Plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2444–55. [CrossRef]

- Marfella R, Di Filippo C, Portoghese M, Ferraraccio F, Crescenzi B, Siniscalchi M, et al. Proteasome Activity as a Target of Hormone Replacement Therapy–Dependent Plaque Stabilization in Postmenopausal Women. Hypertension 2008;51:1135–41. [CrossRef]

- Takami Y, Nakagami H, Morishita R, Katsuya T, Hayashi H, Mori M, et al. Potential Role of CYLD (Cylindromatosis) as a Deubiquitinating Enzyme in Vascular Cells. Am J Pathol 2008;172:818–29. [CrossRef]

- Stangl K, Stangl V. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and endothelial (dys)function. Cardiovasc Res 2010;85:281–90. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto H, Takaoka M, Ohkita M, Itoh M, Nishioka M, Matsumura Y. A proteasome inhibitor lessens the increased aortic endothelin-1 content in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1998;350:R11–2. [CrossRef]

- Meiners S, Ludwig A, Lorenz M, Dreger H, Baumann G, Stangl V, et al. Nontoxic proteasome inhibition activates a protective antioxidant defense response in endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2006;40:2232–41. [CrossRef]

- Stangl V, Lorenz M, Meiners S, Ludwig A, Bartsch C, Moobed M, et al. Long-term up-regulation of eNOS and improvement of endothelial function by inhibition of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. The FASEB Journal 2004;18:272–9. [CrossRef]

- Chade AR, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Krier JD, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Effects of Proteasome Inhibition on the Kidney in Experimental Hypercholesterolemia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2005;16:1005–12. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann J, Saguner AM, Versari D, Peterson TE, Chade A, Olson M, et al. Chronic Proteasome Inhibition Contributes to Coronary Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2007;101:865–74. [CrossRef]

- Reza MI, Syed AA, Kumariya S, Singh P, Husain A, Gayen JR. Pancreastatin induces islet amyloid peptide aggregation in the pancreas, liver, and skeletal muscle: An implication for type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Macromol 2021;182:760–71. [CrossRef]

- Despa S, Margulies KB, Chen L, Knowlton AA, Havel PJ, Taegtmeyer H, et al. Hyperamylinemia Contributes to Cardiac Dysfunction in Obesity and Diabetes. Circ Res 2012;110:598–608. [CrossRef]

- Marmentini C, Branco RCS, Boschero AC, Kurauti MA. Islet amyloid toxicity: From genesis to counteracting mechanisms. J Cell Physiol 2022;237:1119–42. [CrossRef]

- Diehl JA, Fuchs SY, Haines DS. Ubiquitin and Cancer: New Discussions for a New Journal. Genes Cancer 2010;1:679–80. [CrossRef]

- Németh ZH, Wong HR, Odoms K, Deitch EA, Szabó C, Vizi ES, et al. Proteasome Inhibitors Induce Inhibitory κB (IκB) Kinase Activation, IκBα Degradation, and Nuclear Factor κB Activation in HT-29 Cells. Mol Pharmacol 2004;65:342–9. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi N, Mishra DP. Therapeutic targeting of cancer cell cycle using proteasome inhibitors. Cell Div 2012;7:26. [CrossRef]

- Curtis NL, Bolanos-Garcia VM. The Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C): A Versatile E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, 2019, p. 539–623. [CrossRef]

- Mayah A, Arenas RB, Bastida A, Bolanos-Garcia VM. The Use of APC/C Antagonists to Promote Mitotic Catastrophe in Cancer Cells, 2025, p. 207–13. [CrossRef]

- Kapanidou M, Curtis NL, Diaz-Minguez SS, Agudo-Alvarez S, Rus Sanchez A, Mayah A, et al. Targeting APC/C Ubiquitin E3-Ligase Activation with Pyrimidinethylcarbamate Apcin Analogues for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Biomolecules 2024;14:1439. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Kulkarni AA, Xu B, Chu H, Kourelis T, Go RS, et al. Bortezomib-based consolidation or maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J 2020;10:33. [CrossRef]

- Spano D, Catara G. Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System and Recent Advances in Cancer Therapy. Cells 2023;13:29. [CrossRef]

- Goldring MB, Marcu KB. Epigenomic and microRNA-mediated regulation in cartilage development, homeostasis, and osteoarthritis. Trends Mol Med 2012;18:109–18. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Lin SL, Schachner M. A fragment of cell adhesion molecule L1 reduces amyloid-β plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis 2022;13:48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Yao M, Xia S, Zeng F, Liu Q. Systematic and comprehensive insights into HIF-1 stabilization under normoxic conditions: implications for cellular adaptation and therapeutic strategies in cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2025;30:2. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Liu M, Yang Z, Li J, Gao Y, Tan R. Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) in Cancer Therapy: Present and Future. Molecules 2022;27:8828. [CrossRef]

- Cháirez-Ramírez MH, de la Cruz-López KG, García-Carrancá A. Polyphenols as Antitumor Agents Targeting Key Players in Cancer-Driving Signaling Pathways. Front Pharmacol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Floris A, Mazarei M, Yang X, Robinson A, Zhou J, Barberis A, et al. SUMOylation Protects FASN Against Proteasomal Degradation in Breast Cancer Cells Treated with Grape Leaf Extract. Biomolecules 2020;10:529. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau A, Bertolotti A. Regulation of proteasome assembly and activity in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018;19:697–712. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, Joshua D, Pour L, Hájek R, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:27–38. [CrossRef]

- Papanagnou E, Gumeni S, Sklirou AD, Rafeletou A, Terpos E, Keklikoglou K, et al. Autophagy activation can partially rescue proteasome dysfunction-mediated cardiac toxicity. Aging Cell 2022;21. [CrossRef]

- An S, Fu L. Small-molecule PROTACs: An emerging and promising approach for the development of targeted therapy drugs. EBioMedicine 2018;36:553–62. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yang J, Wang T, Luo M, Chen Y, Chen C, et al. Expanding PROTACtable genome universe of E3 ligases. Nat Commun 2023;14:6509. [CrossRef]

- Golonko A, Pienkowski T, Swislocka R, Lazny R, Roszko M, Lewandowski W. Another look at phenolic compounds in cancer therapy the effect of polyphenols on ubiquitin-proteasome system. Eur J Med Chem 2019;167:291–311. [CrossRef]

- Gu W, Wu G, Chen G, Meng X, Xie Z, Cai S. Polyphenols alleviate metabolic disorders: the role of ubiquitin-proteasome system. Front Nutr 2024;11. [CrossRef]

- Chen D, Daniel KG, Chen MS, Kuhn DJ, Landis-Piwowar KR, Dou QP. Dietary flavonoids as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2005;69:1421–32. [CrossRef]

- MEADOR BM, MIRZA KA, TIAN M, SKELDING MB, REAVES LA, EDENS NK, et al. THE GREEN TEA POLYPHENOL EPIGALLOCATECHIN-3-GALLATE (EGCG) ATTENUATES SKELETAL MUSCLE ATROPHY IN A RAT MODEL OF SARCOPENIA. Journal of Frailty & Aging 2015:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Zou L-X, Lin Q-Y, Yan X, Bi H-L, Xie X, et al. Resveratrol as a new inhibitor of immunoproteasome prevents PTEN degradation and attenuates cardiac hypertrophy after pressure overload. Redox Biol 2019;20:390–401. [CrossRef]

- Dosenko VE, Nagibin VS, Tumanovskaya L V., Zagorii VYu, Moibenko AA. Effect of quercetin on the activity of purified 20S and 26S proteasomes and proteasomal activity in isolated cardiomyocytes. Biochem Mosc Suppl B Biomed Chem 2007;1:40–4. [CrossRef]

- Bonfili L, Cecarini V, Amici M, Cuccioloni M, Angeletti M, Keller JN, et al. Natural polyphenols as proteasome modulators and their role as anti-cancer compounds. FEBS J 2008;275:5512–26. [CrossRef]

- Zrelli H, Kusunoki M, Miyazaki H. Role of Hydroxytyrosol-dependent Regulation of HO-1 Expression in Promoting Wound Healing of Vascular Endothelial Cells via Nrf2 De Novo Synthesis and Stabilization. Phytotherapy Research 2015;29:1011–8. [CrossRef]

- Raimundo AF, Félix F, Andrade R, García-Conesa M-T, González-Sarrías A, Gilsa-Lopes J, et al. Combined effect of interventions with pure or enriched mixtures of (poly)phenols and anti-diabetic medication in type 2 diabetes management: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled human trials. Eur J Nutr 2020;59:1329–43. [CrossRef]

- Zhou ZD, Xie SP, Saw WT, Ho PGH, Wang HY, Zhou L, et al. The Therapeutic Implications of Tea Polyphenols against Dopamine (DA) Neuron Degeneration in Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Cells 2019;8:911. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y-M, Abas F, Park Y-S, Park Y-K, Ham K-S, Kang S-G, et al. Bioactivities of Phenolic Compounds from Kiwifruit and Persimmon. Molecules 2021;26:4405. [CrossRef]

- Pierzynowska K, Gaffke L, Jankowska E, Rintz E, Witkowska J, Wieczerzak E, et al. Proteasome Composition and Activity Changes in Cultured Fibroblasts Derived From Mucopolysaccharidoses Patients and Their Modulation by Genistein. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- Cardaci TD, Machek SB, Wilburn DT, Hwang PS, Willoughby DS. Ubiquitin Proteasome System Activity is Suppressed by Curcumin following Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage in Human Skeletal Muscle. J Am Coll Nutr 2021;40:401–11. [CrossRef]

- González-Sarrías A, Espín JC, Tomás-Barberán FA. Non-extractable polyphenols produce gut microbiota metabolites that persist in circulation and show anti-inflammatory and free radical-scavenging effects. Trends Food Sci Technol 2017;69:281–8. [CrossRef]

- Carregosa D, Pinto C, Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, Bastos P, Berry D, Santos CN. A look beyond dietary (poly)phenols: The low molecular weight phenolic metabolites and their concentrations in human circulation. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2022;21:3931–62. [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC. Effect of food structure and processing on (Poly) phenol–gut microbiota interactions and the effects on human health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 2019;10:221–38.

- Espín JC, González-Sarrías A, Tomás-Barberán FA. The gut microbiota: A key factor in the therapeutic effects of (poly)phenols. Biochem Pharmacol 2017;139:82–93. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo C, Colombo F, Biella S, Stockley C, Restani P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients 2021;13:273. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Martín A, Selma MV, Tomás-Barberán FA, González-Sarrías A, Espín JC. Where to Look into the Puzzle of Polyphenols and Health? The Postbiotics and Gut Microbiota Associated with Human Metabotypes. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020;64. [CrossRef]

- Koppel N, Maini Rekdal V, Balskus EP. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science (1979) 2017;356. [CrossRef]

- Cecarini V, Cuccioloni M, Zheng Y, Bonfili L, Gong C, Angeletti M, et al. Flavan-3-ol Microbial Metabolites Modulate Proteolysis in Neuronal Cells Reducing Amyloid-beta (1-42) Levels. Mol Nutr Food Res 2021;65. [CrossRef]

- Johansson E, Lange S, Oshalim M, Lönnroth I. Anti-Inflammatory Substances in Wheat Malt Inducing Antisecretory Factor. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2019;74:489–94. [CrossRef]

- Oh H, Kang M-K, Park S-H, Kim DY, Kim S-I, Oh SY, et al. Asaronic acid inhibits ER stress sensors and boosts functionality of ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation in 7β-hydroxycholesterol-loaded macrophages. Phytomedicine 2021;92:153763. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Wang X, Liu X, Wang L, Ren F, Wang X, et al. Hippuric Acid Promotes Renal Fibrosis by Disrupting Redox Homeostasis via Facilitation of NRF2–KEAP1–CUL3 Interactions in Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants 2020;9:783. [CrossRef]

- Srinual S, Chanvorachote P, Pongrakhananon V. Suppression of cancer stem-like phenotypes in NCI-H460 lung cancer cells by vanillin through an Akt-dependent pathway. Int J Oncol 2017;50:1341–51. [CrossRef]

- Li J-M, Lee Y-C, Li C-C, Lo H-Y, Chen F-Y, Chen Y-S, et al. Vanillin-Ameliorated Development of Azoxymethane/Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Murine Colorectal Cancer: The Involvement of Proteasome/Nuclear Factor-κB/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways. J Agric Food Chem 2018;66:5563–73. [CrossRef]

- Cichocki M, Blumczyńska J, Baer-Dubowska W. Naturally occurring phenolic acids inhibit 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate induced NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2 activation in mouse epidermis. Toxicology 2010;268:118–24. [CrossRef]

- Orabi KY, Abaza MS, Sayed KA El, Elnagar AY, Al-Attiyah R, Guleri RP. Selective growth inhibition of human malignant melanoma cells by syringic acid-derived proteasome inhibitors. Cancer Cell Int 2013;13:82. [CrossRef]

- Taram F, Winter AN, Linseman DA. Neuroprotection comparison of chlorogenic acid and its metabolites against mechanistically distinct cell death-inducing agents in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Brain Res 2016;1648:69–80. [CrossRef]

- Georgousaki K, Tsafantakis N, Gumeni S, Lambrinidis G, González-Menéndez V, Tormo JR, et al. Biological Evaluation and In Silico Study of Benzoic Acid Derivatives from Bjerkandera adusta Targeting Proteostasis Network Modules. Molecules 2020;25:666. [CrossRef]

- Zafar KS, Siegel D, Ross D. A Potential Role for Cyclized Quinones Derived from Dopamine, DOPA, and 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic Acid in Proteasomal Inhibition. Mol Pharmacol 2006;70:1079–86. [CrossRef]

- Kam A, Li KM, Razmovski-Naumovski V, Nammi S, Chan K, Li GQ. Gallic acid protects against endothelial injury by restoring the depletion of DNA methyltransferase 1 and inhibiting proteasome activities. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:231–42. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez J, Caille O, Ferreira D, Francaux M. Pomegranate extract prevents skeletal muscle of mice against wasting induced by acute TNF-α injection. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017;61. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, D’Amico D, Andreux PA, Fouassier AM, Blanco-Bose W, Evans M, et al. Urolithin A improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults. Cell Rep Med 2022;3:100633. [CrossRef]

- Andreux PA, Blanco-Bose W, Ryu D, Burdet F, Ibberson M, Aebischer P, et al. The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nat Metab 2019;1:595–603. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).