Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Standards

2.2. Formulation of RP-25

2.3. UHPLC-HRMS/MS Analysis of RP-25 Formulation

2.4. Coenzyme Q10 Analysis

2.5. Cell Culture

2.6. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Exposure of Cells to RP-25

2.7. Sample Extraction

2.8. NMR Spectra Acquisition

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

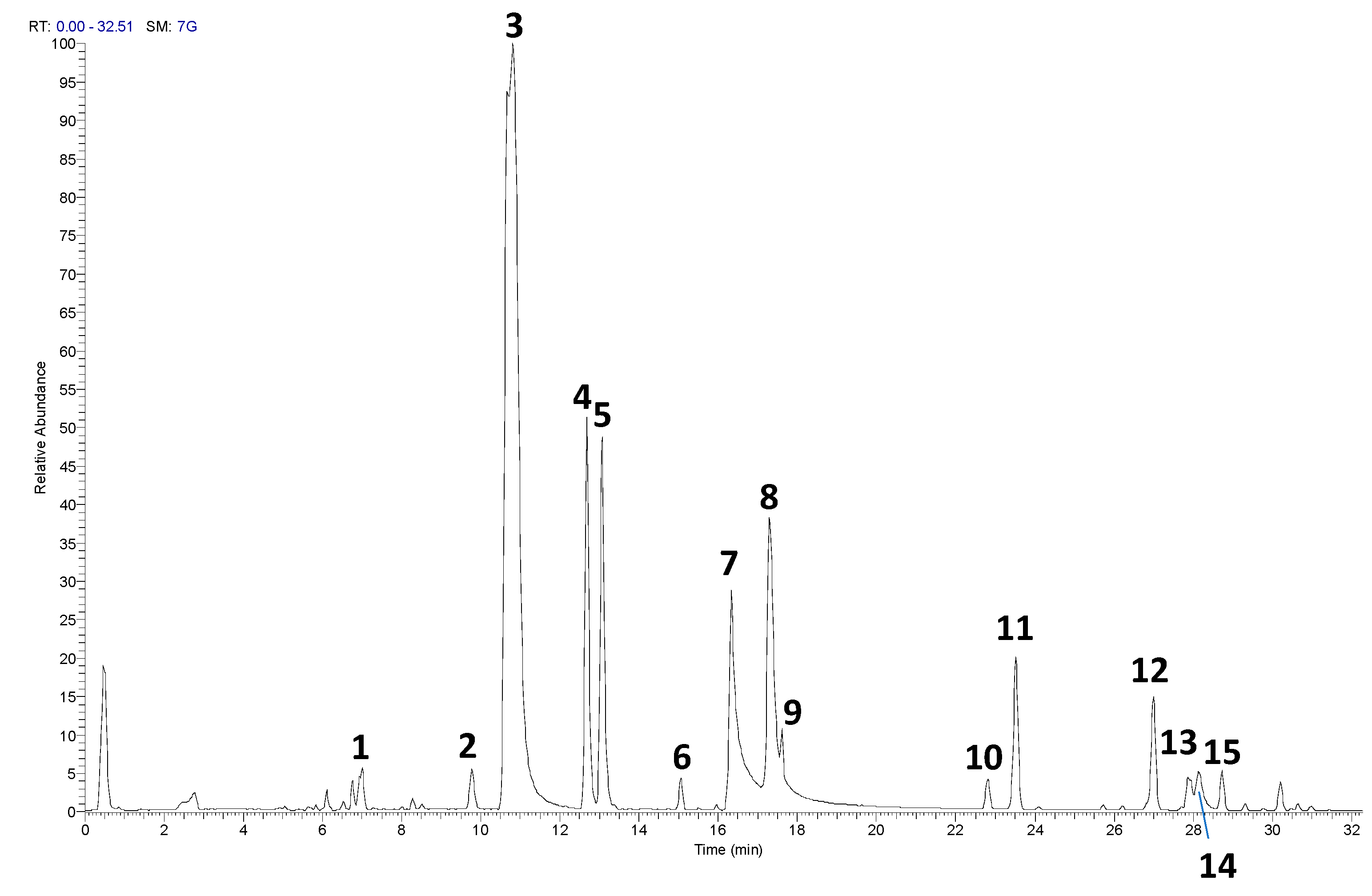

3.1. UHPLC−HRMS/MS Analysis

| N.a | RT [min]. | m/z | Formula | ppm | MS/MS | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.0 | 443.0696 | C32 H11 O3 | 1.424 | 221, 125, 80 | unknown |

| 2 | 9.7 | 741.188 | C32 H37 O20 | 1.053 | 300/301 | Quercetin pentose-rutinoside |

| 3 | 10.8 | 609.1457 | C27 H29 O16 | 1.213 | 300/301 | Rutinb |

| 4 | 12.6 | 593.1509 | C27 H29 O15 | 1.422 | 284/285, 255, 227 | Kaempferol rutinoside |

| 5 | 13.0 | 623.1613 | C28 H31 O16 | 1.057 | 315, 299, 271 | Isorhamnetin rutinoside |

| 6 | 15.0 | 253.0506 | C15 H9 O4 | 4.563 | Dadzeinb | |

| 7 | 16.3 | 301.0353 | C15 H9 O7 | 3.425 | 179, 151 | Quercetinb |

| 8 | 17.3 | 205.0362 | C8 H13 O2 S2 | 5.084 | 171, 127 | lipoic acid |

| 9 | 17.6 | 269.0456 | C15 H9 O5 | 4.349 | Apigeninb | |

| 10 | 22.8 | 227.1289 | C12 H19 O4 | 5.127 | 209,183,165 | Dodecenedioic acid isomer |

| 11 | 23.5 | 227.1288 | C12 H19 O4 | 4.686 | 209,183,165 | Dodecenedioic acid isomer |

| 12 | 26.9 | 941.5097 | C48 H77 O18 | 0.713 | 439 | lanostane-type saponin |

| 13 | 27.8 | 795.4530 | C42 H67 O14 | 0.587 | 439 | lanostane-type saponin |

| 14 | 27.9 | 911.5001 | C47 H75 O17 | 0.332 | 439, 421 | lanostane-type saponin |

| 15 | 28.7 | 925.5159 | C48 H77 O17 | 0.435 | 423 | lanostane-type saponin |

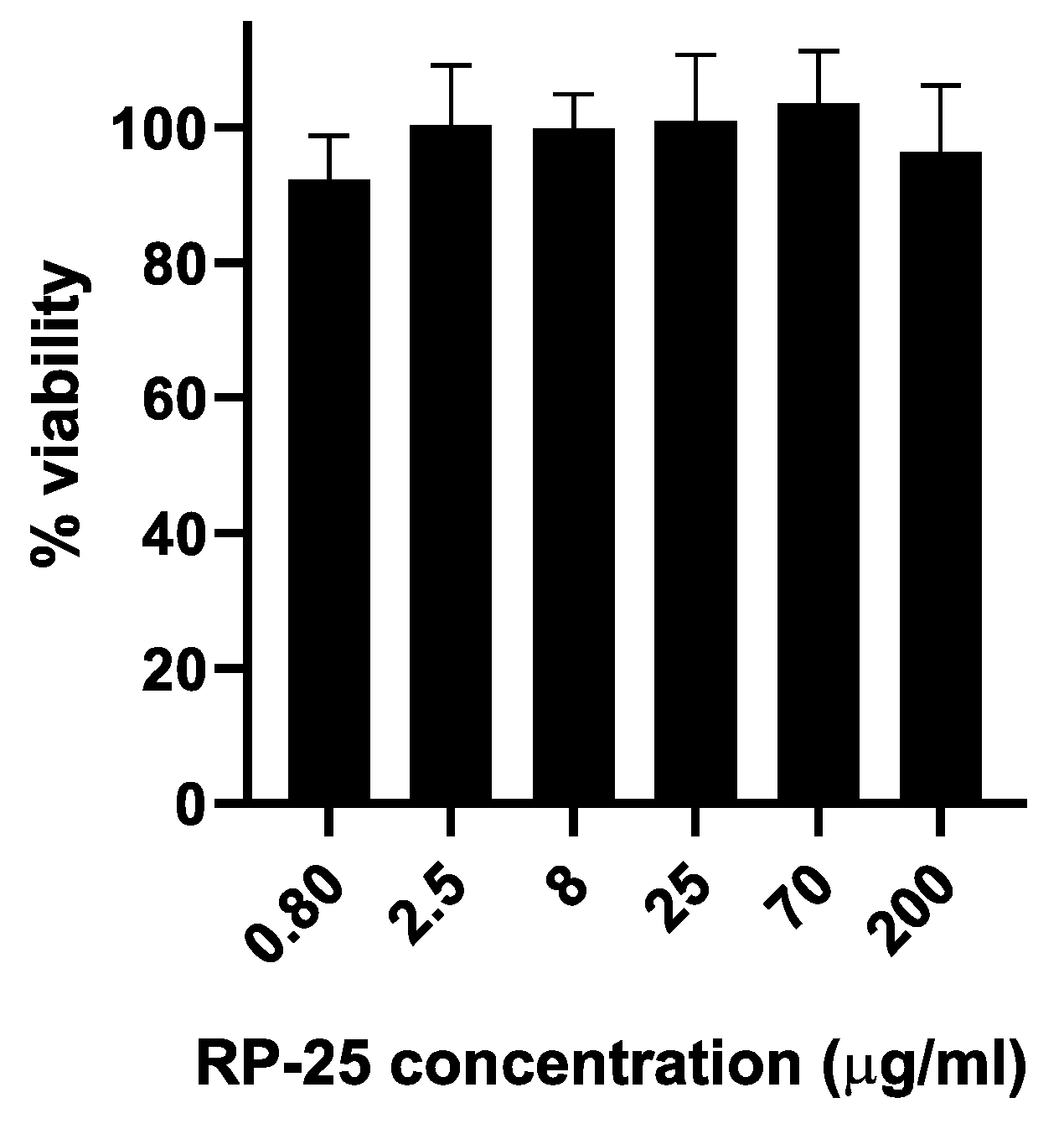

3.2. Cell Viability

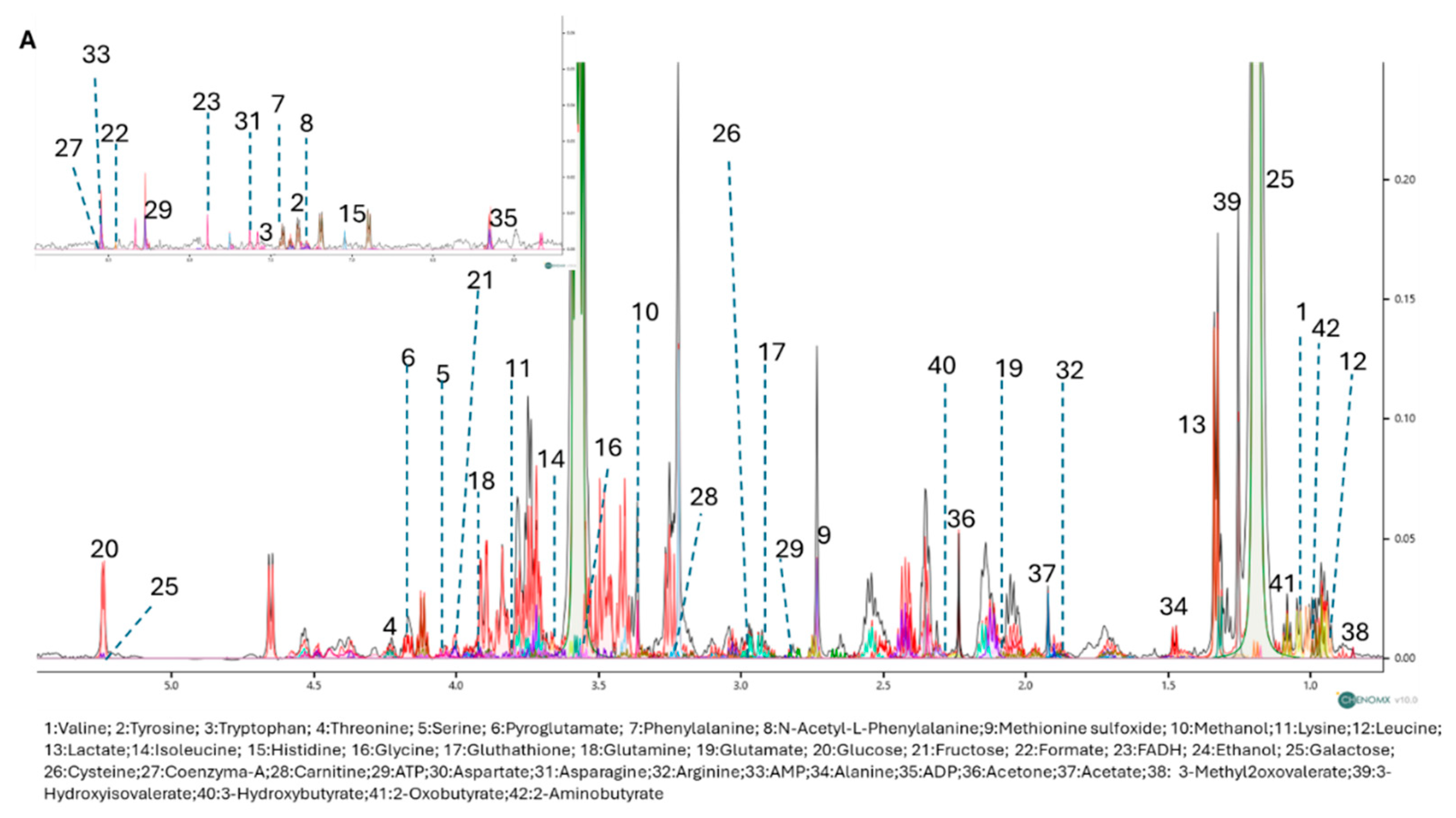

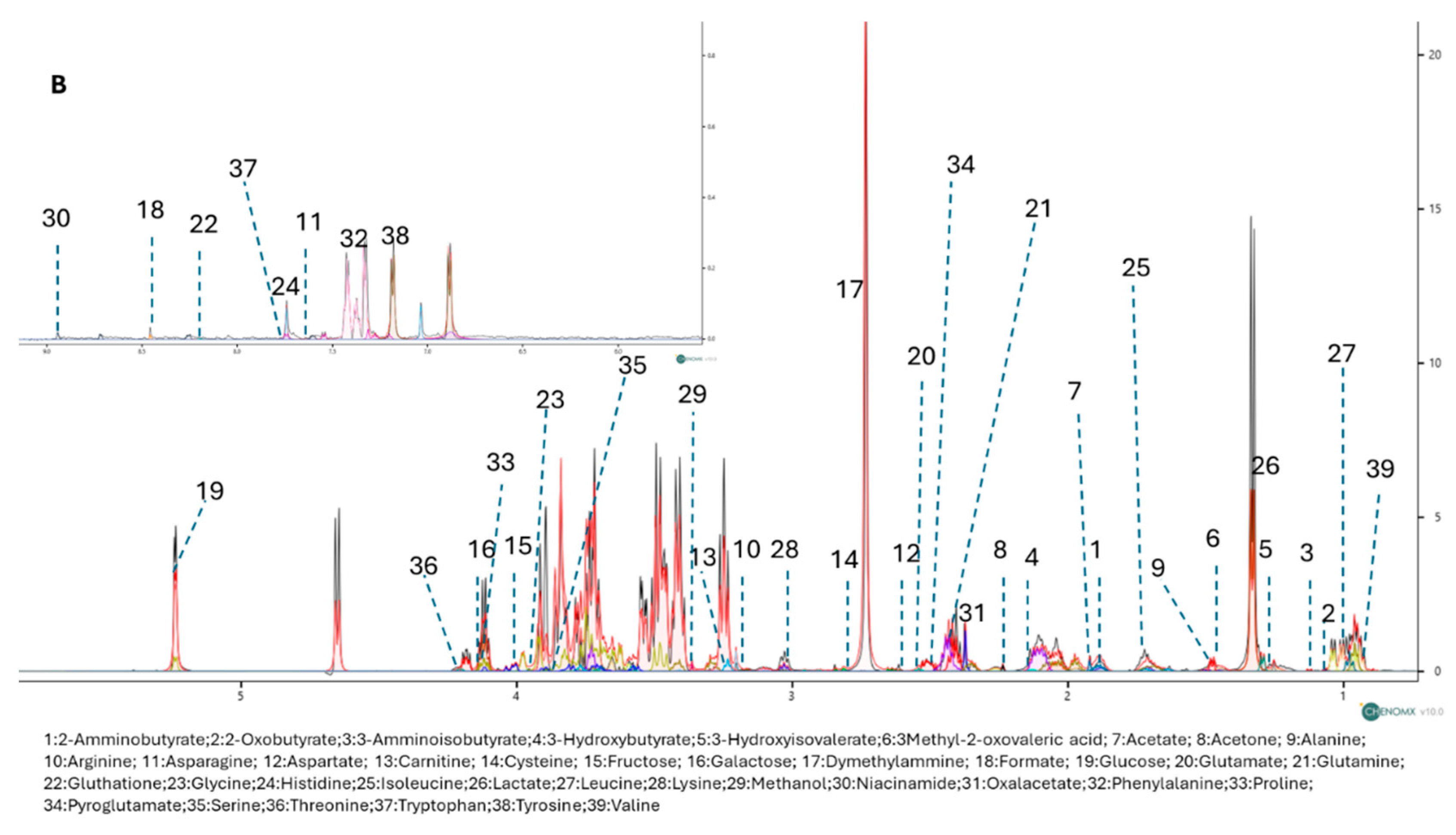

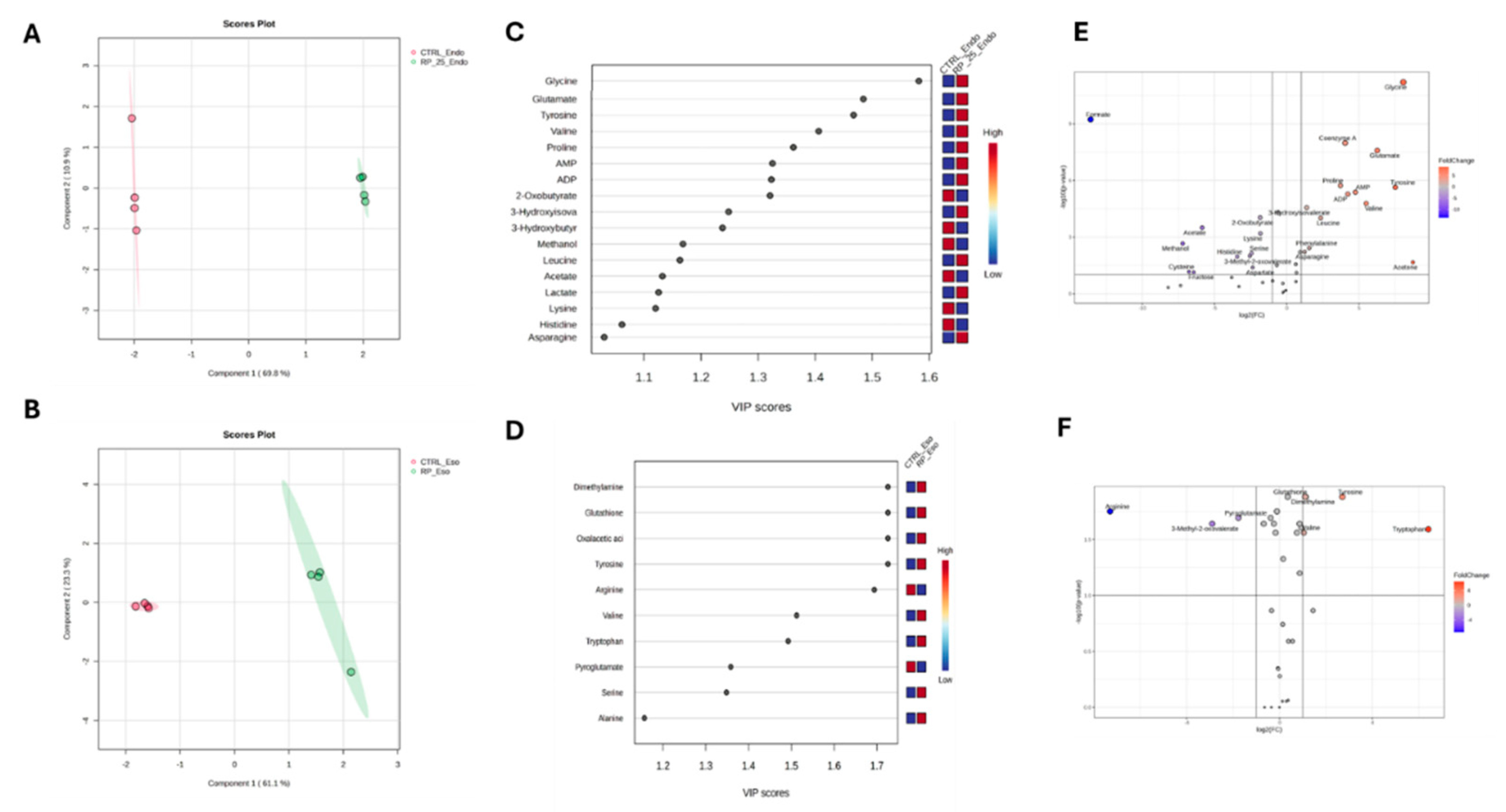

3.3. Untargeted 1H-NMR Metabolomics Analysis

3.4. Enrichment Pathway Analysis

| Hits | p.value | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 4 | 9,56E-05 | 3,82E-03 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 6 | 4,60E-02 | 9,20E-01 |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 3 | 4,63E-01 | 0.00046293 |

| Lipoic acid metabolism | 3 | 0.00052912 | 0.0035275 |

| Histidine metabolism | 3 | 0.0015907 | 0.0079534 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 5 | 0.0018923 | 0.0084101 |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 2 | 0.0028912 | 0.0096374 |

| Phenylalanine tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 2 | 0.0028912 | 0.0096374 |

| Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 2 | 0.0060371 | 0.017249 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 2 | 0.0060371 | 0.017249 |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 2 | 0.015772 | 0.03943 |

| Alanine aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 4 | 0.020867 | 0.049098 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 3 | 0.026161 | 0.038135 |

4. Discussion

4.1. RP-25 Formulation

4.2. Impact on Mitochondrial Function and Energy Metabolism

4.3. Neurotransmission and Amino Acid Metabolism

4.4. Oxidative Stress and Redox Balance

4.5. Potential Therapeutic Implications for Mitochondrial Diseases and Fibromyalgia

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klemmensen, M.M.; Borrowman, S.H.; Pearce, C.; Pyles, B.; & Chandra, B.; Chandra, B. . Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotherapeutics, 2024, 21, e00292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somasundaram, I.; Jain, S.M.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Pathak, S.; Banerjee, A.; Rawat, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with age-related disorders. Frontiers in Physiology, 2024, 15, 1384966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Su, J. Attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction-derived reactive oxygen species and reducing inflammation: the potential of Daphnetin in the viral pneumonia crisis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2024, 15, 1477680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.N.; Mishra, V.K.; Munalisa, R.; Parveen, F.; Ali, S.F.; Akter, K.; Huang, C.Y. Mechanistic insight of mitochondrial dysfunctions in cardiovascular diseases with potential biomarkers. Molecular & Cellular Toxicology.

- Marino, Y.; Inferrera, F.; D'Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis in fibromyalgia syndrome: Molecular mechanism in central nervous system. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 1870. [Google Scholar]

- Inferrera, F.; Marino, Y.; D'Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R. Impaired mitochondrial quality control in fibromyalgia: Mechanisms involved in skeletal muscle alteration. Archives of Biochemistry and Bio physics, 2024, 758, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, C.; Giachi, A.; Fichtner, I.; Pedretti, S.; Puttini, P.S.; Mitro, N.; Gualtierotti, R. Mitochondrial function in patients affected with fibromyalgia syndrome is impaired and correlates with disease severity. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, G.; Marino, C.; Atteno, M.; D’Elia, M.; Pagano, I.; Grimaldi, M.; Rastrelli, L. Investigating the Effectiveness of a Carb-Free Oloproteic Diet in Fibromyalgia Treatment. Nutrients, 2024, 16, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Hargreaves, I.P.; Domingo, J.C.; & Castro-Marrero, J.; Castro-Marrero, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in post-viral fatigue syndrome: an overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaida, M.; Lysiuk, R.; Mykhailenko, O.; Hudz, N.; Abdulsalam, A.; Gontova, T.; Bjørklund, G. Alpha-lipoic acid: An antioxidant with anti-aging properties for disease therapy. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2025, 32, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibullo, D.; Li Volti, G.; Giallongo, C.; Grasso, S.; Tomassoni, D.; Anfuso, C.D.; Bramanti, V. Biochemical and clinical relevance of alpha lipoic acid: antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, molecular pathways and therapeutic potential. Inflammation Research 2017, 66, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ern, P.T. Y. , Quan, T.Y.; Yee, F.S.; & Yin, A.C. Y. Therapeutic properties of Inonotus obliquus (Chaga mushroom): a review. Mycology 2024, 15, 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia, M.; Marino, C.; Celano, R.; Napolitano, E.; D’Ursi, A.M.; Russo, M.; & Rastrelli, L.; Rastrelli, L. Impact of a Withania somnifera and Bacopa monnieri Formulation on SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cells Metabolism Through NMR Metabolomic. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckonert, O.; Keun, H.C.; Ebbels, T.M.; Bundy, J.; Holmes, E.; Lindon, J.C.; & Nicholson, J.K.; Nicholson, J. K. Metabolic profiling, metabolomic and metabonomic procedures for NMR spectroscopy of urine, plasma, serum and tissue extracts. Nat. protoc. 2007, 2, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, R.T. How the 1D-NOESY suppresses solvent signal in metabonomics NMR spectroscopy: An examination of the pulse sequence components and evolution. Concepts Magn. Reson. Part A 2011, 38A, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.; Deborde, C.; Lefebvre, M.; Maucourt, M.; Moing, A. NMRProcFlow: A graphical and interactive tool dedicated 460 to 1D spectra processing for NMR-based metabolomics. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wishart, D.S. Using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 for comprehensive metabolomics data analysis. Current protocols in, 2016; 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Hoque, M.A.; Sugimoto, M. Robust volcano plot: identification of differential metabolites in the presence of 464 outliers. BMC bioinformatics 2018, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for 466 metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Research.

- Peng, H.; & Shahidi, F.; Shahidi, F. Qualitative analysis of secondary metabolites of chaga mushroom (Inonotus Obliquus): phenolics, fatty acids, and terpenoids. Journal of Food Bioactives 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Critch, A.L.; Manful, C.F.; Rajakaruna, A.; Vidal, N.P.; Pham, T.H.; Thomas, R. Effects of pH and temperature on water under pressurized conditions in the extraction of nutraceuticals from chaga (Inonotus obliquus) mushroom. Antioxidants, 2021, 10, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Alrosan, M.; Alu'datt, M.H.; & Tan, T.; Tan, T. C 10-hydroxy decanoic acid, trans-10-hydroxy-2-decanoic acid, and sebacic acid: Source, metabolism, and potential health functionalities and nutraceutical applications. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 3878–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Toyoshima, M.; & Yamada, T. ; & Yamada, T. New lanostane-type triterpenoids, inonotsutriols D, and E, from Inonotus obliquus. Phytochemistry Letters 2011, 4, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Rakuša, Ž. T. , Kristl, A.; & Roškar, R. Quantification of reduced and oxidized coenzyme Q10 in supplements and medicines by HPLC-UV. Analytical methods, 2020, 12, 2580–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Worley, B.; Halouska, S.; & Powers, R.; Powers, R. Utilities for quantifying separation in PCA/PLS-DA scores plots. Analytical biochemistry, 2013, 433, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhuis, J.A.; Hoefsloot, H.C.; Smit, S.; Vis, D.J.; Smilde, A.K.; van Velzen, E.J.; van Dorsten, F.A. Assessment of PLSDA cross validation. Metabolomics, 2008, 4, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarachantachote, N.; Chadcham, S.; & Saithanu, K.; Saithanu, K. Cutoff threshold of variable importance in projection for variable selection. Int J Pure Appl Math, 2014, 94, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Bjørklund, G.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Semenova, Y.; Piscopo, S.; & Peana, M.; Peana, M. Coenzyme Q10 in aging and disease. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2024, 64, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, R.H. (2019). Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging and diseases of aging. Biology.

- Hou, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liang, Y.; Dai, S.; Ji, Q.; Yang, Y. Efficacy and Optimal Dose of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Inflammation-Related Biomarkers: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2023, 67, 2200800. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, L.; & La Motta, C.; La Motta, C. The use of the Coenzyme Q10 as a food supplement in the management of fibromyalgia: a critical review. Antioxidants, 2022, 11, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podda, M.; Zollner, T.M.; Grundmann-Kollmann, M.; Thiele, J.J.; Packer, L.; & Kaufmann, R.; Kaufmann, R. Activity of alpha-lipoic acid in the protection against oxidative stress in skin. Oxidants and antioxidants in cutaneous biology, 2000, 29, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tülüce, Y.; Osmanoğlu, D.; Rağbetli, M.Ç.; & Altındağ, F.; Altındağ, F. Protective action of curcumin and alpha-lipoic acid, against experimental ultraviolet-A/B induced dermal-injury in rats. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superti, F.; & Russo, R. ; & Russo, R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar]

- Szychowski, K.A.; Rybczyńska-Tkaczyk, K.; Tobiasz, J.; Yelnytska-Stawasz, V.; Pomianek, T.; & Gmiński, J. ; & Gmiński, J. Biological and anticancer properties of Inonotus obliquus extracts. Process Biochemistry, 2018, 73, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, R.W.; Han, R.; Gao, Y.Q.; Li, D.; Yin, X.; & Gao, J.M.; Gao, J. M. Anti-neuroinflammatory polyoxygenated lanostanoids from Chaga mushroom Inonotus obliquus. Phytochemistry 2021, 184, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Bai, M.; Xue, X.B.; Zou, C.X.; Huang, X.X.; & Song, S.J.; Song, S. J. Isolation of chemical compositions as dietary antioxidant supplements and neuroprotectants from Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus). Food Bioscience 2022, 47, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Jang, Y.W.; Jung, J.Y.; & Yun, B.S.; Yun, B. S. New antioxidant polyphenols from the medicinal mushroom Inonotus obliquus. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2007, 17, 6678–6681. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.H.; Li, J.; Shen, Z.C.; Lin, X.F.; Chen, A.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, X.Y. Advances in health-promoting effects of natural polysaccharides: Regulation on Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2023, 10, 1102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, G.; Russo, S.; Carli, F.; Infelise, P.; Panunzi, S.; Bertuzzi, A.; Mingrone, G. Dodecanedioic acid prevents and reverses metabolic-associated liver disease and obesity and ameliorates liver fibrosis in a rodent model of diet-induced obesity. The FASEB Journal, 2024, 38, e70202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Kerem, Z.; Makkar, H.P.; & Becker, K.; Becker, K. The biological action of saponins in animal systems: a review. British journal of Nutrition, 2002, 88, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Rauf, A.; Fahad, F.I.; Emran, T.B.; Mitra, S.; Olatunde, A.; Mubarak, M.S. Superoxide dismutase: an updated review on its health benefits and industrial applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2022, 62, 7282–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; & Jeong, D.; Jeong, D. Bimodal actions of selenium essential for antioxidant and toxic pro-oxidant activities: the selenium paradox. Molecular medicine reports, 2012, 5, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, X.; Shan, H.; & Zhang, M.; Zhang, M. The role of copper homeostasis in brain disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 2022, 23, 13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadmanesh, J.; & Borgstahl, G.E.; Borgstahl, G. E. A review of the catalytic mechanism of human manganese superoxide dismutase. Antioxidants, 2018, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, G.; da Cruz, I.B. M. , & González-Gallego, J. Manganese superoxide dismutase and oxidative stress modulation. Advances in clinical chemistry, 2015, 68, 87–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pincemail, J.; & Meziane, S.; Meziane, S. On the potential role of the antioxidant couple vitamin E/selenium taken by the oral route in skin and hair health. Antioxidants, 2022, 11, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, Y.C. Mechanistic basis and clinical evidence for the applications of nicotinamide (niacinamide) to control skin aging and pigmentation. Antioxidants, 2021, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalykina, E.S.; Sergeeva, T.N.; Ananyan, M.A.; Cherenkov, I.A.; & Sergeev, V.G.; Sergeev, V. G. A Water-soluble Form of Dihydroquercetin Reduces LPS-induced Astrogliosis, Vascular Remodeling, and mRNA VEGF-A Levels in the Substantia Nigra of Aged Rats. Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Disorders, 2024, 8, 014–019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Qiu, D.; Yang, T.; Su, J.; Liu, C.; Su, X.; Zhang, S. Research progress of dihydroquercetin in the treatment of skin diseases. Molecules, 2023, 28, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, A.; Crane, J.D.; Ogborn, D.; Hettinga, B.; Akhtar, M.; Stokl, A.; Tarnopolsky, M. Supplementation with α-lipoic acid, CoQ10, and vitamin E augments running performance and mitochondrial function in female mice. PloS one, 6072. [Google Scholar]

- Muoio, D.M. Metabolic inflexibility: when mitochondrial indecision leads to metabolic gridlock. Cell, 2014, 159, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, Y.; Inferrera, F.; D'Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis in fibromyalgia syndrome: Molecular mechanism in central nervous system. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 1870. [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo, G.; Marino, C.; D’Elia, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Napolitano, E.; D’Ursi, A.M.; & Rastrelli, L.; Rastrelli, L. The Effectiveness of the Low-Glycemic and Insulinemic (LOGI) Regimen in Maintaining the Benefits of the VLCKD in Fibromyalgia Patients. Nutrients, 2024, 16, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, L.I.; Maksimovich, N.Y.; & Burak, I.N. ; & Burak, I.N. Amino Acids that Play an Important Role in the Functioning of the Nervous System Review. Clinical Trails and Clinical Research.

- Schmitt, H.P. Neuro-modulation, aminergic neuro-disinhibition and neuro-degeneration: Draft of a comprehensive theory for Alzheimer disease. Medical hypotheses, 2005, 65, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Nasreen, A.; Menzel, A.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Pivina, L.; Noor, S.; Bjørklund, G. Neurotransmitters regulation and food intake: The role of dietary sources in neurotransmission. Molecules, 2022, 28, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; & Wu, G. ; & Wu, G. Metabolism of amino acids in the brain and their roles in regulating food intake. Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health: Amino acids in systems function and health.

- Orsucci, D.; Mancuso, M.; Ienco, E.C.; LoGerfo, A.; & Siciliano, G.; Siciliano, G. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration by means of coenzyme Q10 and its analogues. Current medicinal chemistry, 2011, 18, 4053–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Markiewicz, L.; Kabzinski, J.; Odrobina, D.; & Majsterek, I.; Majsterek, I. Potential of redox therapies in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Biosci, 2017, 9, 214–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Ahuja, A.; & Pathak, S.; Pathak, S. Potential Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 2024, 27, 2043–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, E.R.; Winter, M.G.; Duerkop, B.A.; Spiga, L.; de Carvalho, T.F.; Zhu, W.; Winter, S.E. Microbial respiration and formate oxidation as metabolic signatures of inflammation-associated dysbiosis. Cell host & microbe, 2017, 21, 208–219. [Google Scholar]

- Phang, J.M. Proline metabolism in cell regulation and cancer biology: recent advances and hypotheses. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2019, 30, 635–649. [Google Scholar]

- Pietzke, M.; Meiser, J.; & Vazquez, A.; Vazquez, A. Formate metabolism in health and disease. Molecular metabolism, 2020, 33, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szrok-Jurga, S.; Turyn, J.; Hebanowska, A.; Swierczynski, J.; Czumaj, A.; Sledzinski, T.; & Stelmanska, E.; Stelmanska, E. The role of Acyl-CoA β-oxidation in brain metabolism and neurodegenerative diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24, 13977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Natarajan, S.K.; & Becker, D.F.; Becker, D. F. Proline mechanisms of stress survival. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2013, 19, 998–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak, V.I. Glutathione homeostasis and functions: potential targets for medical interventions. Journal of amino acids, 7368. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.M.; Wilson-Delfosse, A.L.; & Mieyal, J.; Mieyal, J. JDysregulation of glutathione homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients, 2012, 4, 1399–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).