Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

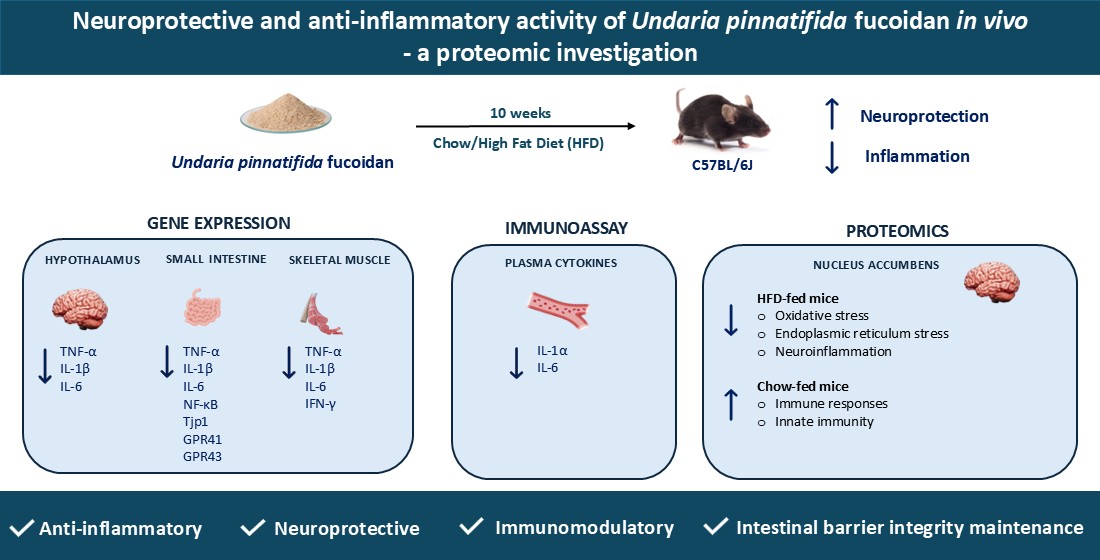

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

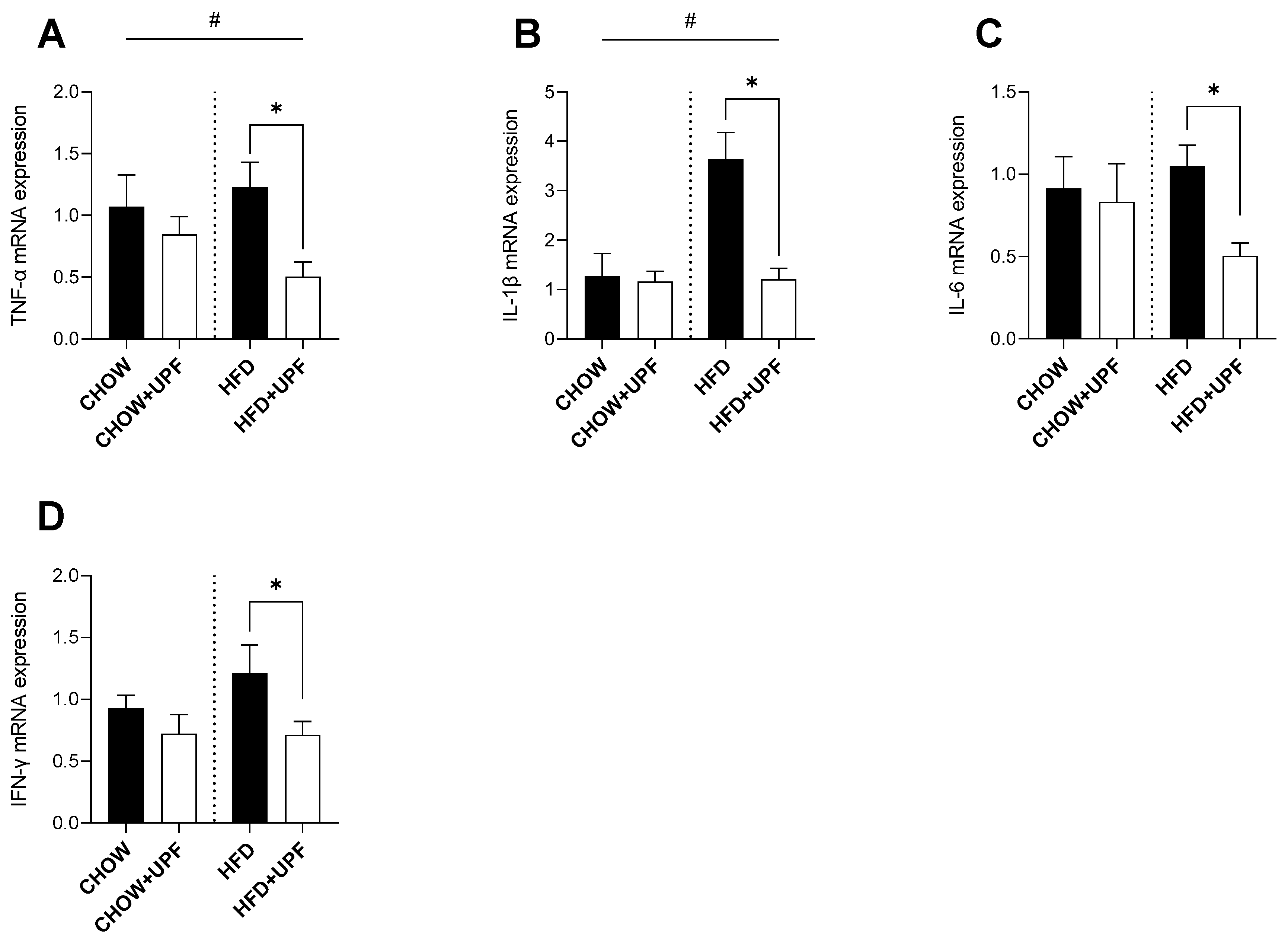

2.1. Effects of HFD and UPF on Skeletal Muscle Gene Expression

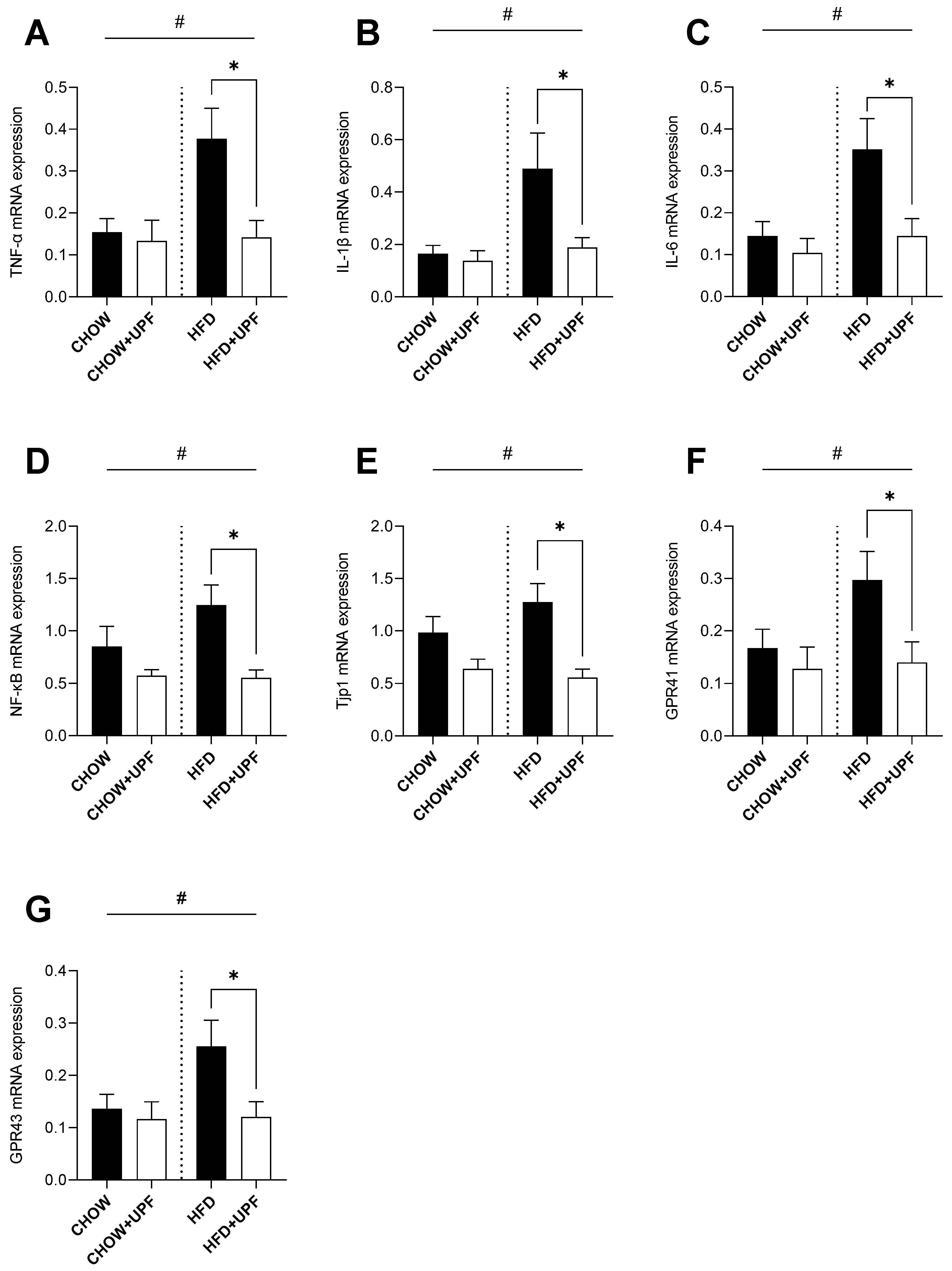

2.2. Effects of HFD and UPF on Small Intestine Gene Expression

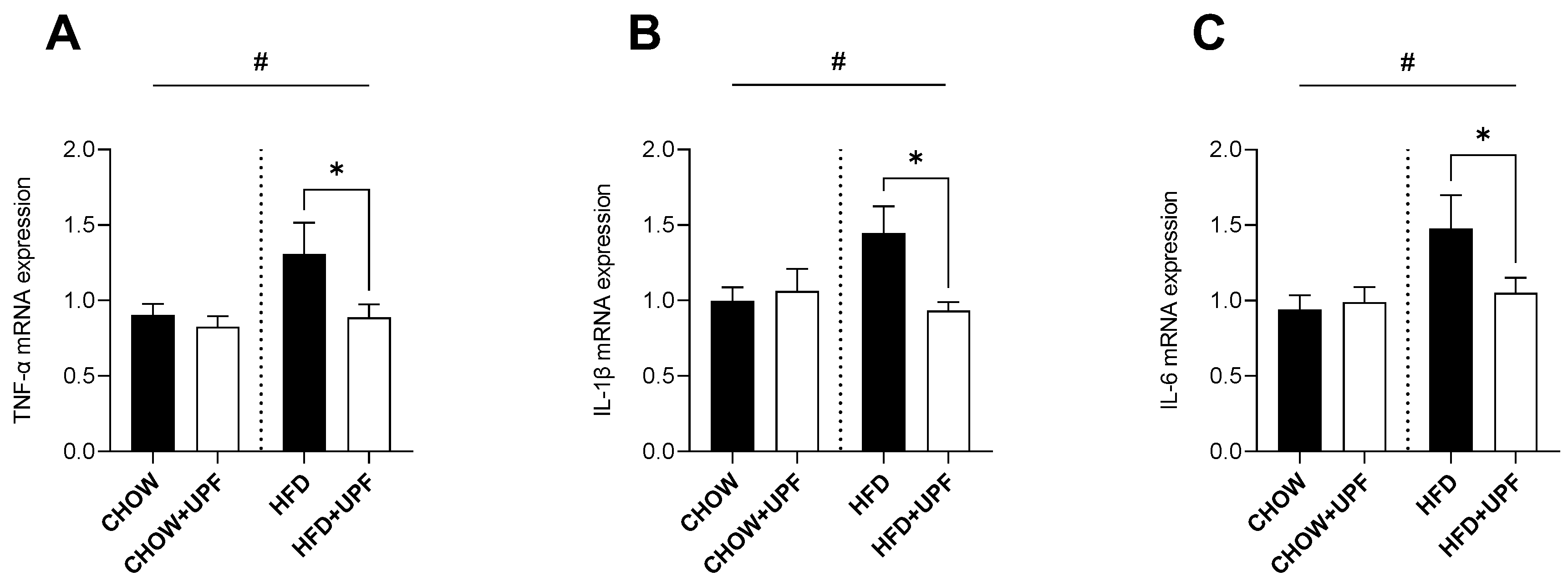

2.3. Effects of HFD and UPF on Hypothalamic Gene Expression

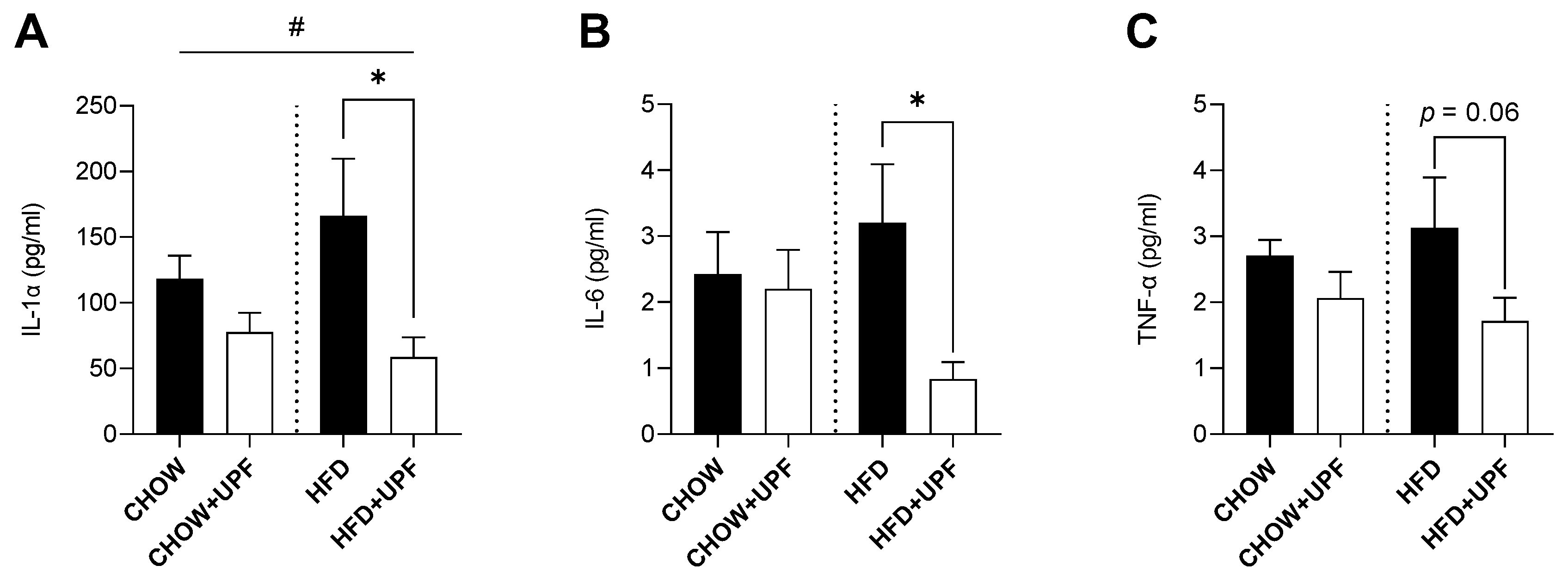

2.4. Effects of HFD and UPF on Pro-Inflammatory Plasma Cytokine Levels

2.5. Effects of UPF on NAc Protein Abundance

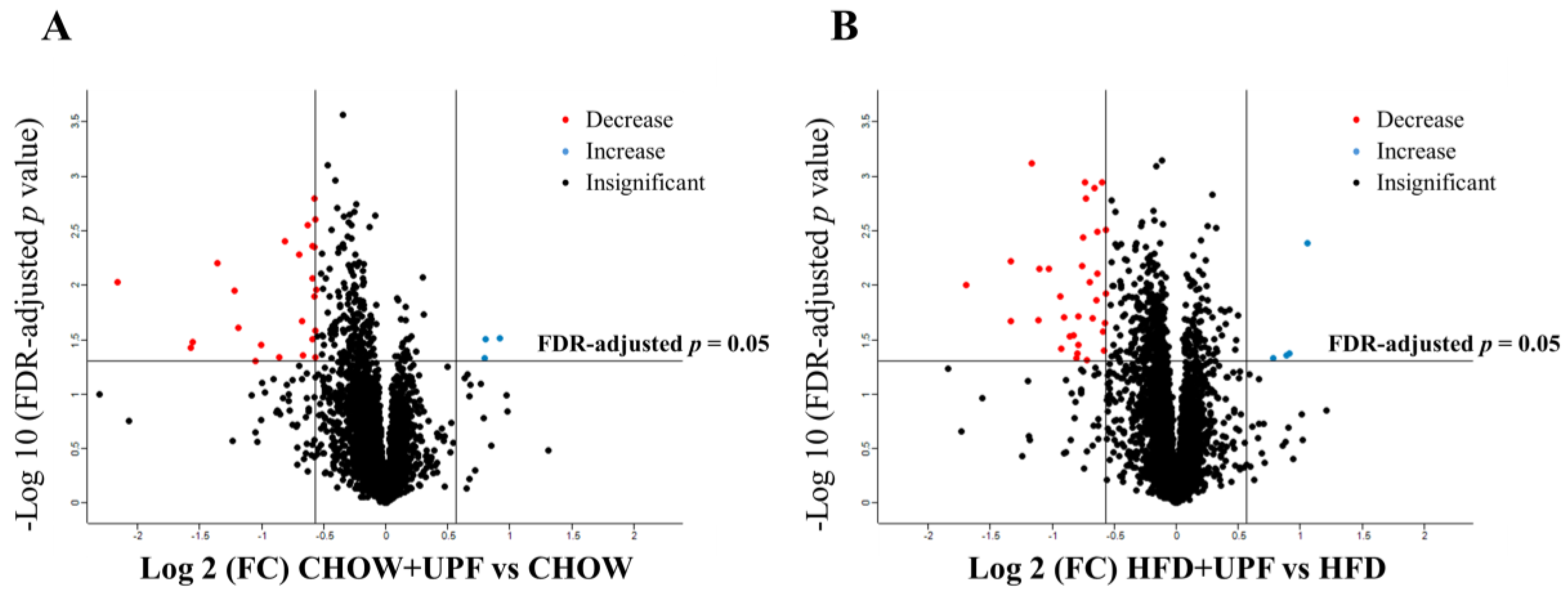

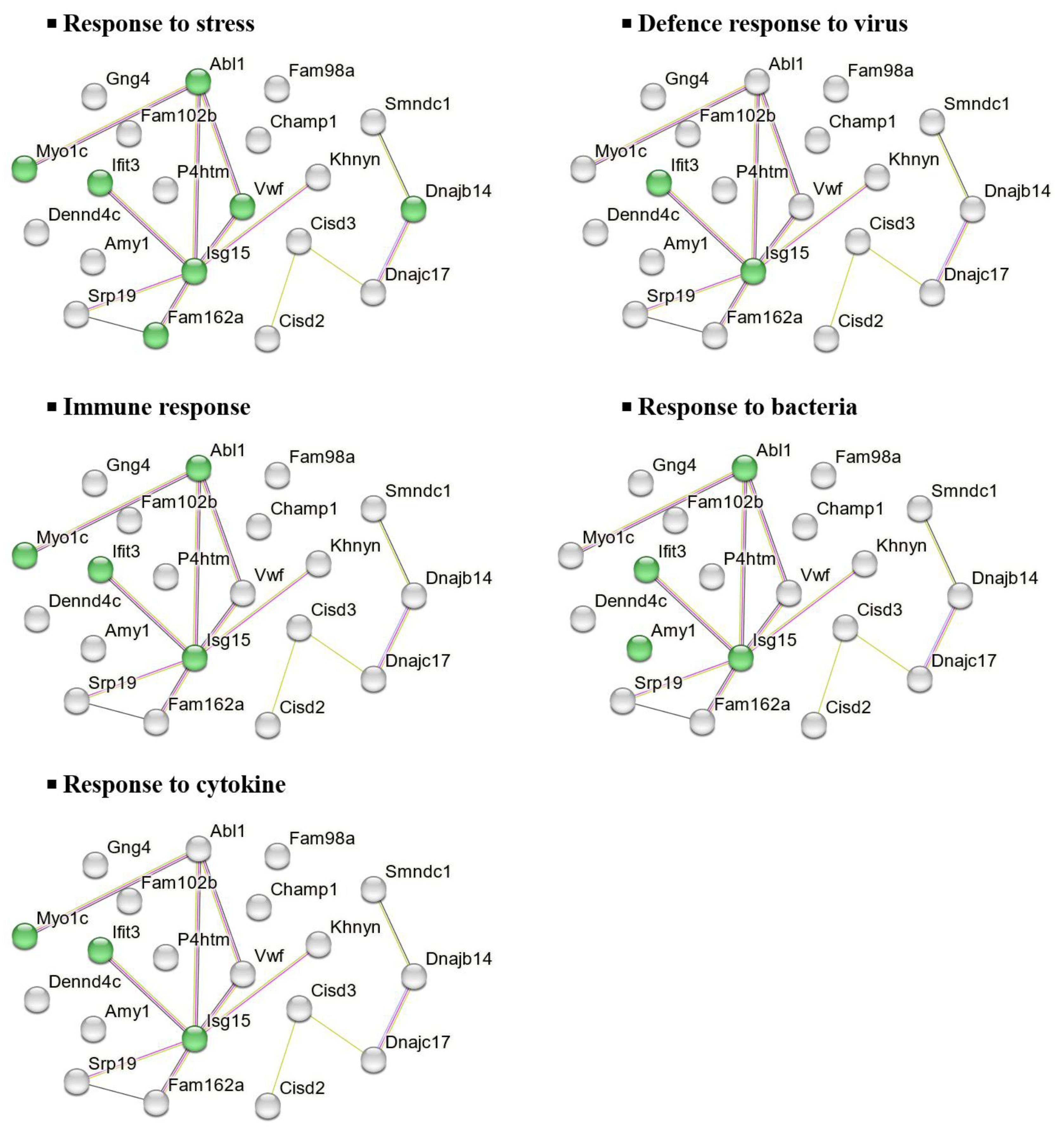

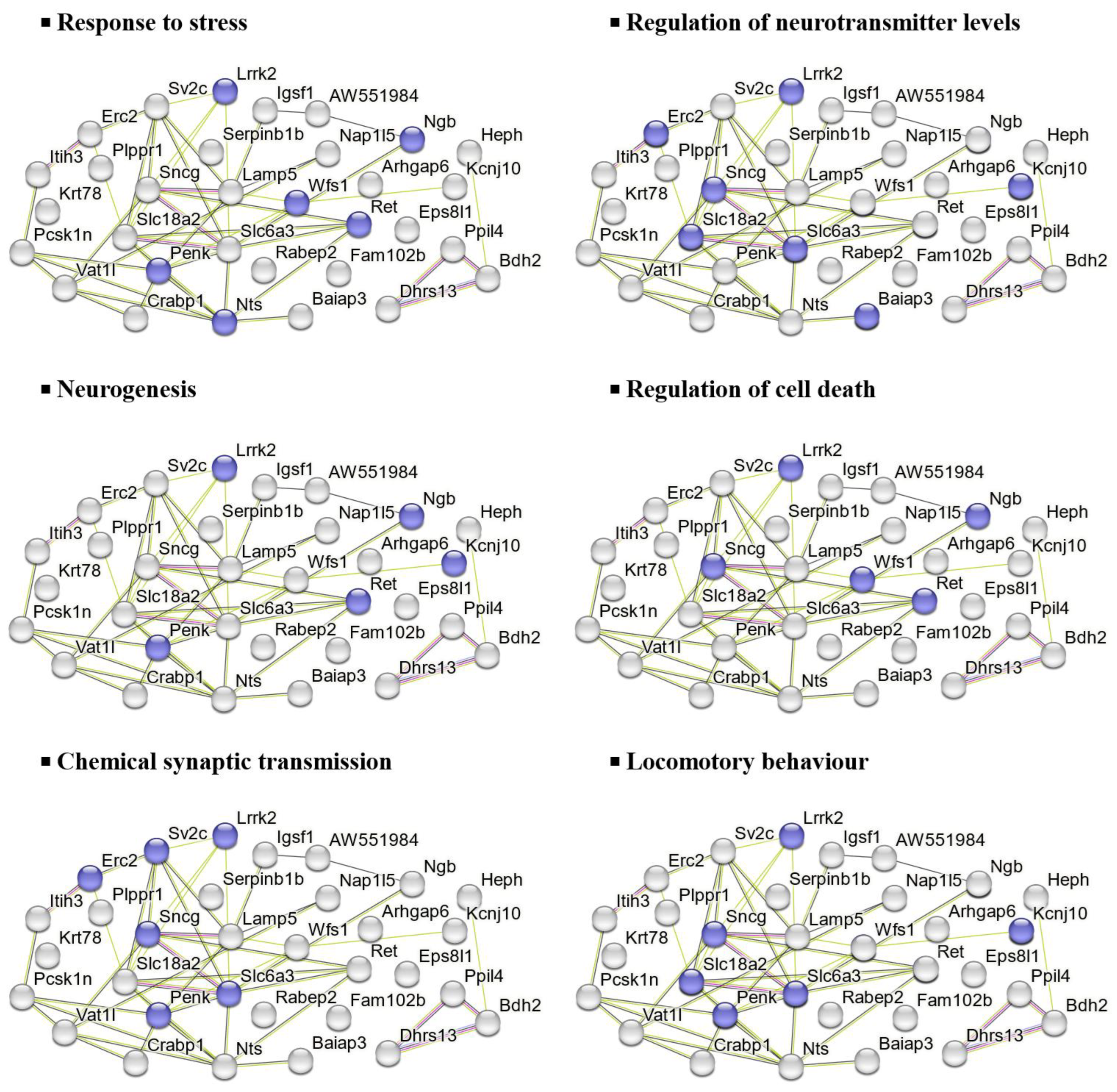

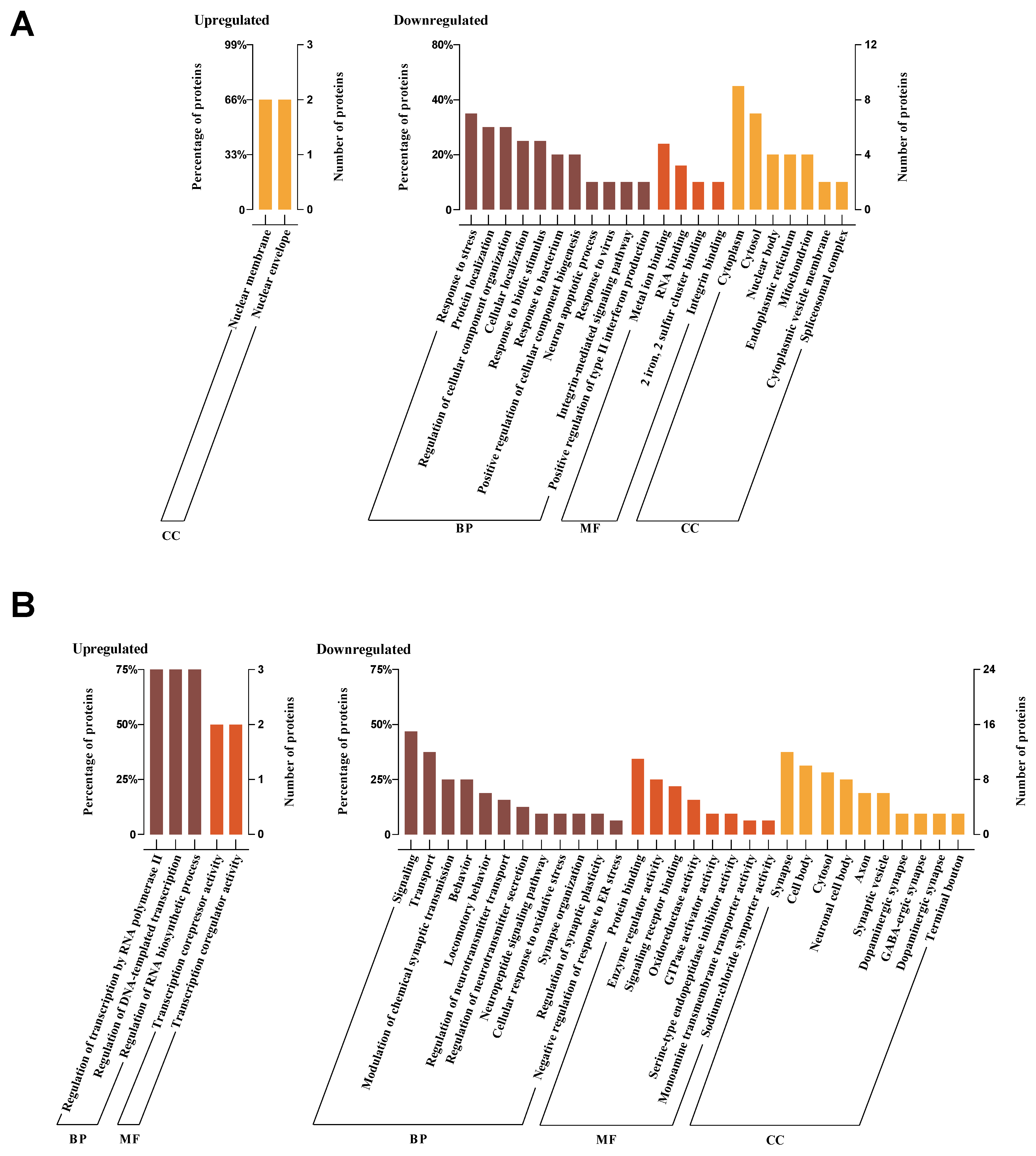

2.5.1. Expression Profiles of Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs) in the NAc

2.5.2. Molecular Functions and Biological Implications of DEPs in the NAc

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

4.2. Animals and Diet

4.3. Fucoidan Administration and Experimental Groups

4.4. Sample Collection

4.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Assay

4.6. Proteomic Analysis

4.7. Proteomics Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, S.; Yu, Y.; White, W.L.; Yang, S.; Yang, F.; Lu, J. Fucoidan Extracted from Undaria pinnatifida: Source for Nutraceuticals/Functional Foods. Marine Drugs 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, E.; Lukova, P.; Baldzhieva, A.; Katsarov, P.; Nikolova, M.; Iliev, I.; Peychev, L.; Trica, B.; Oancea, F.; Delattre, C.; et al. Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Fucoidan: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Teng, H.; Hou, L.; Yin, Y.; Zou, X. Protective Effects of Fucoidan on Aβ25-35 and d-Gal-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells and d-Gal-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction in Mice. Marine Drugs 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, H.J.; Stringer, D.S.; Park, A.Y.; Karpiniec, S.N. Therapies from Fucoidan: New Developments. Mar Drugs 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, J.H.; Stringer, D.N.; Karpiniec, S.S. Therapies from Fucoidan: An Update. Marine Drugs 2015, 13, 5920–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, J.H.; Dell'Acqua, G.; Gardiner, V.-A.; Karpiniec, S.S.; Stringer, D.N.; Davis, E. Topical Benefits of Two Fucoidan-Rich Extracts from Marine Macroalgae. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.Y.; Bourtembourg, M.; Chrétien, A.; Hubaux, R.; Lancelot, C.; Salmon, M.; Fitton, J.H. Modulation of Gene Expression in a Sterile Atopic Dermatitis Model and Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus Adhesion by Fucoidan. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2021, 8, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.P.; O'Connor, J.; Fitton, J.H.; Brooks, L.; Rolfe, M.; Connellan, P.; Wohlmuth, H.; Cheras, P.A.; Morris, C. A Combined Phase I and II Open Label Study on the Effects of A Seaweed Extract Nutrient Complex on Osteoarthritis. Biologics 2010, 4, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.C.S.; Sousa, R.B.; Franco, Á.X.; Costa, J.V.G.; Neves, L.M.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Sutton, R.; Criddle, D.N.; Soares, P.M.G.; de Souza, M.H.L.P. Protective Effects of Fucoidan, a P- and L-Selectin Inhibitor, in Murine Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas 2014, 43, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.D.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, T.; Jang, S.A.; Kang, S.C.; Koo, H.J.; Sohn, E.; Bak, J.P.; Namkoong, S.; Kim, H.K.; et al. Fucoidan from Fucus vesiculosus Protects Against Alcohol-Induced Liver Damage by Modulating Inflammatory Mediators in Mice and HepG2 Cells. Marine Drugs 2015, 13, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Eapen, M.S.; Ishaq, M.; Park, A.Y.; Karpiniec, S.S.; Stringer, D.N.; Sohal, S.S.; Fitton, J.H.; Guven, N.; Caruso, V.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Fucoidan Extracts In Vitro. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.; Dragar, C.; Elliot, K.; Fitton, J.H.; Godwin, J.; Thompson, K. GFS, A Preparation of Tasmanian Undaria pinnatifida Is Associated with Healing and Inhibition of Reactivation of Herpes. BMC Complement Altern Med 2002, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phull, A.-R.; Majid, M.; Haq, I.-u.; Khan, M.R.; Kim, S.J. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Anti-arthritic, Antioxidant Efficacy of Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 97, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, K.H.I.N.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, A.; Sook, C.E.; Lee, B.-Y.; Jee, Y. The Role of Fucoidans Isolated from the Sporophylls of Undaria pinnatifida against Particulate-Matter-Induced Allergic Airway Inflammation: Evidence of the Attenuation of Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Responses. Molecules 2020, 25, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugasundaram, D.; Dwan, C.; Wimmer, B.C.; Srivastava, S. Fucoidan Ameliorates Testosterone-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Rats. Res Rep Urol 2024, 16, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zheng, C.; Song, B.; Li, F.; Kong, X.; Xu, K. Inflammatory Links Between High Fat Diets and Diseases. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.R.; Shin, S.-K.; Yoo, J.-H.; Kim, S.; Young, H.A.; Kwon, E.-Y. Chronic inflammation in high-fat diet-fed mice: Unveiling the early pathogenic connection between liver and adipose tissue. Journal of Autoimmunity 2023, 139, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, T.; Wu, J.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; Powis, S.H.; Chen, Y.; Ruan, X.Z. Chronic inflammation exacerbates glucose metabolism disorders in C57BL/6J mice fed with high-fat diet. J Endocrinol 2013, 219, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Foundations of Immunometabolism and Implications for Metabolic Health and Disease. Immunity 2017, 47, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydemann, A. An Overview of Murine High Fat Diet as a Model for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Res 2016, 2016, 2902351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Dwan, C.; Wimmer, B.C.; Wilson, R.; Johnson, L.; Caruso, V. Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida Enhances Exercise Performance and Increases the Abundance of Beneficial Gut Bacteria in Mice. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Moon, I.S.; Goo, T.W.; Moon, S.S.; Seo, M. Algae Undaria pinnatifida Protects Hypothalamic Neurons against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress through Akt/mTOR Signaling. Molecules 2015, 20, 20998–21009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzini, E.; Peña-Corona, S.I.; Hernández-Parra, H.; Chandran, D.; Saleena, L.A.K.; Sawikr, Y.; Peluso, I.; Dhumal, S.; Kumar, M.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; et al. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in Alzheimer's disease: Targeting neuroinflammation strategies. Phytotherapy Research 2024, 38, 3169–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazwi, M.; Smid, S.; Karpiniec, S.; Zhang, W. Comparative study on neuroprotective activities of fucoidans from Fucus vesiculosus and Undaria pinnatifida. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 122, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueven, N.; Spring, K.J.; Holmes, S.; Ahuja, K.; Eri, R.; Park, A.Y.; Fitton, J.H. Micro RNA Expression after Ingestion of Fucoidan; A Clinical Study. Mar Drugs 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, B.A.; Vincenty, C.S.; Chandler, A.J.; Cintineo, H.P.; Lints, B.S.; Mastrofini, G.F.; Arent, S.M. Effects of fucoidan supplementation on inflammatory and immune response after high-intensity exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2023, 20, 2224751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.; Jiang, Y.; Signal, N.; O'Brien, D.; Chen, J.; Murphy, R.; Lu, J. Combining mussel with fucoidan as a supplement for joint pain and prediabetes: Study protocol for a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhou, K. The nucleus accumbens in reward and aversion processing: Insights and implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, K.A.; Dion-Albert, L.; Lebel, M.; LeClair, K.; Labrecque, S.; Tuck, E.; Ferrer Perez, C.; Golden, S.A.; Tamminga, C.; Turecki, G.; et al. Molecular adaptations of the blood-brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 3326–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, L.; Ferhat, M.; Salamé, E.; Robin, A.; Herbelin, A.; Gombert, J.-M.; Silvain, C.; Barbarin, A. Interleukin-1 Family Cytokines: Keystones in Liver Inflammatory Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleau, C.; Karelis, A.D.; St-Pierre, D.H.; Lamontagne, L. Crosstalk between intestinal microbiota, adipose tissue and skeletal muscle as an early event in systemic low-grade inflammation and the development of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2015, 31, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.; Kesper, M.S.; Marschner, J.A.; Konrad, L.; Ryu, M.; Kumar VR, S.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Mulay, S.R.; Romoli, S.; Demleitner, J.; et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis, Barrier Dysfunction, and Bacterial Translocation Account for CKD–Related Systemic Inflammation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017, 28, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, C.L.; Kleckner, I.R.; Jatoi, A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Dunne, R.F. The Role of Systemic Inflammation in Cancer-Associated Muscle Wasting and Rationale for Exercise as a Therapeutic Intervention. JCSM Clin Rep 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burfeind, K.G.; Michaelis, K.A.; Marks, D.L. The central role of hypothalamic inflammation in the acute illness response and cachexia. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2016, 54, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H. The influence of systemic inflammation on inflammation in the brain: Implications for chronic neurodegenerative disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2004, 18, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, C.S.L.; Thang, L.A.N.; Maier, A.B. Markers of inflammation and their association with muscle strength and mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 2020, 64, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.; Hsu, W.L.; Hwang, P.A.; Chen, Y.L.; Chou, T.C. Combined administration of fucoidan ameliorates tumor and chemotherapy-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in bladder cancer-bearing mice. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 51608–51618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; You, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, J.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, D. Low molecular weight fucoidan ameliorates hindlimb ischemic injury in type 2 diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2018, 210, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraha, A.; Chinen, H.; Hokama, A.; Yonashiro, T.; Kinjo, T.; Kishimoto, K.; Nakamoto, M.; Hirata, T.; Kinjo, N.; Higa, F.; et al. Fucoidan enhances intestinal barrier function by upregulating the expression of claudin-1. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 5500–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, Q.Y.; Eri, R.D.; Fitton, J.H.; Patel, R.P.; Gueven, N. Fucoidan Extracts Ameliorate Acute Colitis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-i.; Raghavendran, H.R.B.; Sung, N.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Chun, B.S.; Ahn, D.H.; Choi, H.-S.; Kang, K.-W.; Lee, J.-W. Effect of fucoidan on aspirin-induced stomach ulceration in rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2010, 183, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.; Song, S.; Ai, C. Fucoidan Alleviates Colitis and Metabolic Disorder by Protecting the Intestinal Barrier, Suppressing the MAPK/NF-κB Pathways, and Regulating the Gut Microbiota. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2024, 2024, 7955190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.M.; Negm, W.A.; Hawwal, M.F.; Hussein, I.A.; Elekhnawy, E.; Ulber, R.; Zayed, A. Fucoidan mitigates gastric ulcer injury through managing inflammation, oxidative stress, and NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. International Immunopharmacology 2023, 120, 110335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Cathelicidin-WA Facilitated Intestinal Fatty Acid Absorption Through Enhancing PPAR-γ Dependent Barrier Function. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, J.; Ronde, E.; English, N.; Clark, S.K.; Hart, A.L.; Knight, S.C.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Al-Hassi, H.O. Tight junctions in inflammatory bowel diseases and inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Liang, H.; Xue, M.; Liu, Y.; Gong, A.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Yang, J.; Meng, D. Protective effect and mechanism of fucoidan on intestinal mucosal barrier function in NOD mice. Food and Agricultural Immunology 2020, 31, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kang, S.G.; Park, J.H.; Yanagisawa, M.; Kim, C.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Activate GPR41 and GPR43 on Intestinal Epithelial Cells to Promote Inflammatory Responses in Mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 396–406.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Z.; Ding, J.L. GPR41 and GPR43 in Obesity and Inflammation - Protective or Causative? Front Immunol 2016, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, K.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Ng, A.; Kranich, J.; Sierro, F.; Di, Y.; Schilter, H.C.; Rolph, M.S.; Mackay, F.; Artis, D.; et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009, 461, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Chandra, R.A.; Ye, G.; Zhuang, S.; Zhu, W.; Shen, X. Microbial community shifts elicit inflammation in the caecal mucosa via the GPR41/43 signalling pathway during subacute ruminal acidosis. BMC Veterinary Research 2019, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Q.M.; Ni, W.W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, A.L.; Du, P.; Li, C.; Yu, S.S. Modulatory effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus KLDS 1.0738 on intestinal short-chain fatty acids metabolism and GPR41/43 expression in β-lactoglobulin-sensitized mice. Microbiol Immunol 2019, 63, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Suk, K.; Yu, R.; Kim, M.S. Cellular Contributors to Hypothalamic Inflammation in Obesity. Mol Cells 2020, 43, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaliere, G.; Viggiano, E.; Trinchese, G.; De Filippo, C.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Valenzano, A.; Cincione, R.I.; Zammit, C.; Cimmino, F.; et al. Long Feeding High-Fat Diet Induces Hypothalamic Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, and Prolonged Hypothalamic AMPK Activation in Rat Animal Model. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.; Tran, D.; Yang, C.; Ng, M.J.; Kackanattil, A.; Tata, K.; Deans, B.J.; Bleasel, M.; Vicenzi, S.; Randall, C.; et al. The Anti-Obesity Compound Asperuloside Reduces Inflammation in the Liver and Hypothalamus of High-Fat-Fed Mice. Endocrines 2022, 3, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jais, A.; Brüning, J.C. Hypothalamic inflammation in obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thuc, O.; Stobbe, K.; Cansell, C.; Nahon, J.-L.; Blondeau, N.; Rovère, C. Hypothalamic Inflammation and Energy Balance Disruptions: Spotlight on Chemokines. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, H.; Yang, Q.; Ben, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; et al. Fucoidan antagonizes diet-induced obesity and inflammation in mice. J Biomed Res 2020, 35, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Lv, H.; Yin, T.; Fan, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, H. Fucoidan Protects Against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Modulates Gut Microbiota in Institute of Cancer Research Mice. J Med Food 2021, 24, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroggi, F.; Ghazizadeh, A.; Nicola, S.M.; Fields, H.L. Roles of Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell in Incentive-Cue Responding and Behavioral Inhibition. The Journal of Neuroscience 2011, 31, 6820–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, Y.-C.; Lenschow, D.J. ISG15 in antiviral immunity and beyond. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przanowski, P.; Loska, S.; Cysewski, D.; Dabrowski, M.; Kaminska, B. ISG'ylation increases stability of numerous proteins including Stat1, which prevents premature termination of immune response in LPS-stimulated microglia. Neurochemistry International 2018, 112, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, M.; Bergmann, C.C. Alpha/Beta Interferon (IFN-α/β) Signaling in Astrocytes Mediates Protection against Viral Encephalomyelitis and Regulates IFN-γ-Dependent Responses. J Virol 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaim, C.D.; Scott, A.F.; Canadeo, L.A.; Huibregtse, J.M. Extracellular ISG15 Signals Cytokine Secretion through the LFA-1 Integrin Receptor. Mol Cell 2017, 68, 581–590.e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Shang, X. Downregulation of interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 relieves the inflammatory response and myocardial fibrosis of mice with myocardial infarction and improves their cardiac function. Exp Anim 2021, 70, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, H.V.; Sweeney, T.R. Better together: The role of IFIT protein–protein interactions in the antiviral response. Journal of General Virology 2018, 99, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Han, M.H.; Park, C.; Jin, C.-Y.; Kim, G.-Y.; Choi, I.-W.; Kim, N.D.; Nam, T.-J.; Kwon, T.K.; Choi, Y.H. Anti-inflammatory effects of fucoidan through inhibition of NF-κB, MAPK and Akt activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV2 microglia cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Han, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Guan, F.; Ma, S. Fucoidan: A promising agent for brain injury and neurodegenerative disease intervention. Food & Function 2021, 12, 3820–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.A.; Chandía-Cristi, A.; Yáñez, M.J.; Zanlungo, S.; Álvarez, A.R. c-Abl kinase at the crossroads of healthy synaptic remodeling and synaptic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 2023, 18, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebron, M.L.; Lonskaya, I.; Olopade, P.; Selby, S.T.; Pagan, F.; Moussa, C.E. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition Regulates Early Systemic Immune Changes and Modulates the Neuroimmune Response in α-Synucleinopathy. J Clin Cell Immunol 2014, 5, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. The capable ABL: What is its biological function? Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmachari, S.; Ge, P.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, D.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Kumar, M.; Mao, X.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Pletnikova, O.; et al. Activation of tyrosine kinase c-Abl contributes to α-synuclein–induced neurodegeneration. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2016, 126, 2970–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, B.; Broermann, A.; Li, H.; Khandoga, A.G.; Zarbock, A.; Krombach, F.; Goerge, T.; Schneider, S.W.; Jones, C.; Nieswandt, B.; et al. von Willebrand factor promotes leukocyte extravasation. Blood 2010, 116, 4712–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gragnano, F.; Sperlongano, S.; Golia, E.; Natale, F.; Bianchi, R.; Crisci, M.; Fimiani, F.; Pariggiano, I.; Diana, V.; Carbone, A.; et al. The Role of von Willebrand Factor in Vascular Inflammation: From Pathogenesis to Targeted Therapy. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 2017, 5620314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mansi, S.; Mitchell, T.P.; Mobayen, G.; McKinnon, T.A.J.; Miklavc, P.; Frick, M.; Nightingale, T.D. Myosin-1C augments endothelial secretion of von Willebrand factor by linking contractile actomyosin machinery to the plasma membrane. Blood Advances 2024, 8, 4714–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suidan, G.L.; Brill, A.; De Meyer, S.F.; Voorhees, J.R.; Cifuni, S.M.; Cabral, J.E.; Wagner, D.D. Endothelial Von Willebrand factor promotes blood-brain barrier flexibility and provides protection from hypoxia and seizures in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013, 33, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, T.N.; de Maat, M.P.M.; van Goor, M.-L.P.J.; Bhagwanbali, V.; van Vliet, H.H.D.M.; Gómez García, E.B.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Leebeek, F.W.G. High von Willebrand Factor Levels Increase the Risk of First Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2006, 37, 2672–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Wei, L.; Cai, P.; Xu, H.; Luo, H.; Bai, X.; Lu, L.; Liu, J.-R.; Fan, W.; et al. von Willebrand factor contributes to poor outcome in a mouse model of intracerebral haemorrhage. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 35901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravillas-Montero, J.L.; Gillespie, P.G.; Patiño-López, G.; Shaw, S.; Santos-Argumedo, L. Myosin 1c Participates in B Cell Cytoskeleton Rearrangements, Is Recruited to the Immunologic Synapse, and Contributes to Antigen Presentation. The Journal of Immunology 2011, 187, 3053–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, D.; Xuan, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, K. COP9 signalosome complex is a prognostic biomarker and corresponds with immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 5264–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Sugiyama, A.; Uzawa, K.; Fujisawa, N.; Tashiro, Y.; Tashiro, F. Implication of Trip15/CSN2 in early stage of neuronal differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Developmental Brain Research 2003, 140, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ni, P.; Mou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhao, T.; Loh, Y.-H.; Chen, L. Cops2 promotes pluripotency maintenance by Stabilizing Nanog Protein and Repressing Transcription. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 26804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykke-Andersen, K.; Schaefer, L.; Menon, S.; Deng, X.W.; Miller, J.B.; Wei, N. Disruption of the COP9 signalosome Csn2 subunit in mice causes deficient cell proliferation, accumulation of p53 and cyclin E, and early embryonic death. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 6790–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Angelo, M.A.; Gomez-Cavazos, J.S.; Mei, A.; Lackner, D.H.; Hetzer, M.W. A change in nuclear pore complex composition regulates cell differentiation. Dev Cell 2012, 22, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Sepehrimanesh, M. Nucleocytoplasmic Transport: Regulatory Mechanisms and the Implications in Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehle, M.S.; Webber, P.J.; Tse, T.; Sukar, N.; Standaert, D.G.; DeSilva, T.M.; Cowell, R.M.; West, A.B. LRRK2 Inhibition Attenuates Microglial Inflammatory Responses. The Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendivil-Perez, M.; Velez-Pardo, C.; Jimenez-Del-Rio, M. Neuroprotective Effect of the LRRK2 Kinase Inhibitor PF-06447475 in Human Nerve-Like Differentiated Cells Exposed to Oxidative Stress Stimuli: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochemical Research 2016, 41, 2675–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Pajarillo, E.; Rizor, A.; Son, D.S.; Lee, J.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. LRRK2 kinase plays a critical role in manganese-induced inflammation and apoptosis in microglia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallings, R.L.; Tansey, M.G. LRRK2 regulation of immune-pathways and inflammatory disease. Biochem Soc Trans 2019, 47, 1581–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Inoue, H.; Tanizawa, Y.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Oba, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Shinoda, K.; Oka, Y. WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome 1) gene product: Predominant subcellular localization to endoplasmic reticulum in cultured cells and neuronal expression in rat brain. Human Molecular Genetics 2001, 10, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.G.; Fukuma, M.; Lipson, K.L.; Nguyen, L.X.; Allen, J.R.; Oka, Y.; Urano, F. WFS1 Is a Novel Component of the Unfolded Protein Response and Maintains Homeostasis of the Endoplasmic Reticulum in Pancreatic β-Cells*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 39609–39615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoli, L.; Bramanti, P.; Di Bella, C.; De Luca, F. Genetic and clinical aspects of Wolfram syndrome 1, a severe neurodegenerative disease. Pediatric Research 2018, 83, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Inflammatory Basis of Metabolic Disease. Cell 2010, 140, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.C.; Morris, M.W.; Lee, S.K.; Pouranfar, F.; Wang, Y.; Gozal, D. Neuroglobin protects PC12 cells against oxidative stress. Brain Research 2008, 1190, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchetti, M.; Fernandez, V.S.; Montalesi, E.; Marino, M. Neuroglobin: A Novel Player in the Oxidative Stress Response of Cancer Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 6315034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Takahashi, N.; Uchida, H.; Wakasugi, K. Human Neuroglobin Functions as an Oxidative Stress-responsive Sensor for Neuroprotection*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 30128–30138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yu, Z.; Cho, K.-S.; Chen, H.; Malik, M.T.A.; Chen, X.; Lo, E.H.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.F. Neuroglobin Is an Endogenous Neuroprotectant for Retinal Ganglion Cells against Glaucomatous Damage. The American Journal of Pathology 2011, 179, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Z.; Guo, S.; Lee, S.R.; Xing, C.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Nicholls, D.G.; Lo, E.H.; Wang, X. Effects of neuroglobin overexpression on mitochondrial function and oxidative stress following hypoxia/reoxygenation in cultured neurons. J Neurosci Res 2009, 87, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrafiah, A. Thymoquinone Protects Neurons in the Cerebellum of Rats through Mitigating Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Following High-Fat Diet Supplementation. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.S.A.; Lu, J.; Zhou, W. Structure characterization and antioxidant activity of fucoidan isolated from Undaria pinnatifida grown in New Zealand. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 212, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokudome, K.; Okumura, T.; Shimizu, S.; Mashimo, T.; Takizawa, A.; Serikawa, T.; Terada, R.; Ishihara, S.; Kunisawa, N.; Sasa, M.; et al. Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) regulates kindling epileptogenesis via GABAergic neurotransmission. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 27420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.S.; Andersen, J.; Jørgensen, T.N.; Sørensen, L.; Eriksen, J.; Loland, C.J.; Strømgaard, K.; Gether, U.; Simonsen, U. SLC6 Neurotransmitter Transporters: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Pharmacological Reviews 2011, 63, 585–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, N.; Glatt, C.E.; Isacson, O. High regulatability favors genetic selection in SLC18A2, a vesicular monoamine transporter essential for life. Faseb j 2010, 24, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikoshkov, A.; Drakenberg, K.; Wang, X.; Horvath, M.C.; Keller, E.; Hurd, Y.L. Opioid neuropeptide genotypes in relation to heroin abuse: Dopamine tone contributes to reversed mesolimbic proenkephalin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B.A.; Lambeng, N.; Nocka, K.; Kensel-Hammes, P.; Bajjalieh, S.M.; Matagne, A.; Fuks, B. The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 9861–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.L.; Xiong, N.; Yu, J.; Zai, C.C.; Pouget, J.G.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Qing, H.; Wang, T.; Martin, E.; et al. Increased Nigral SLC6A3 Activity in Schizophrenia Patients: Findings From the Toronto-McLean Cohorts. Schizophr Bull 2016, 42, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Luo, C.; Huang, H.; Chen, J.; Gong, C.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Fucoidan exerts antidepressant-like effects in mice via regulating the stability of surface AMPARs. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2020, 521, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, M.; Møller, S.; Hansen, T.; Moens, U.; Van Ghelue, M. The multifunctional roles of the four-and-a-half-LIM only protein FHL2. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006, 63, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixler, V. The role of FHL2 in wound healing and inflammation. The FASEB Journal 2019, 33, 7799–7809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixler, V.; Cromme, C.; Retser, E.; Meyer, L.-H.; Smyth, N.; Mühlenberg, K.; Korb-Pap, A.; Koers-Wunrau, C.; Sotsios, Y.; Bassel-Duby, R.; et al. FHL2 regulates the resolution of tissue damage in chronic inflammatory arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2015, 74, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Völkl, S.; Ludwig, S.; Schneider, H.; Wixler, V.; Park, J. Deficiency of Fhl2 leads to delayed neuronal cell migration and premature astrocyte differentiation. Journal of Cell Science 2019, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pol, V.; Vos, M.; DeRuiter, M.C.; Goumans, M.J.; de Vries, C.J.M.; Kurakula, K. LIM-only protein FHL2 attenuates inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells through inhibition of the NFκB pathway. Vascular Pharmacology 2020, 125–126, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajar, A.; Nordhoff, C.; Schied, T.; Chiquet-Ehrismann, R.; Loser, K.; Vogl, T.; Ludwig, S.; Wixler, V. The LIM-only protein FHL2 attenuates lung inflammation during bleomycin-induced fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verset, L.; Feys, L.; Trépant, A.L.; De Wever, O.; Demetter, P. FHL2: A scaffold protein of carcinogenesis, tumour-stroma interactions and treatment response. Histol Histopathol 2016, 31, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, R.; Kudoh, F.; Ito, S.; Tani, I.; Janairo, J.I.B.; Omichinski, J.G.; Sakaguchi, K. Metal-dependent Ser/Thr protein phosphatase PPM family: Evolution, structures, diseases and inhibitors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020, 215, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, F.; Wang, W.; Cui, M.; Wu, M.; Jiang, S.; Dai, J.; Lian, H.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. PPM1F in hippocampal dentate gyrus regulates the depression-related behaviors by modulating neuronal excitability. Experimental Neurology 2021, 340, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, H.; Katoh, T.; Nakagawa, R.; Ishihara, Y.; Sueyoshi, N.; Kameshita, I.; Taniguchi, T.; Hirano, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Ishida, A. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase phosphatase (CaMKP/PPM1F) interacts with neurofilament L and inhibits its filament association. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 477, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitman, Z.J. Smaller Protein, Larger Therapeutic Potential: PPM1D as a New Therapeutic Target in Brainstem Glioma. Pharmacogenomics 2014, 15, 1639–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, N.; Council, M.R. Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes; Australian Government Publishing Service: 1997.

- Zhang, L. Method for Voluntary Oral Administration of Drugs in Mice. STAR Protoc 2021, 2, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A New Mathematical Model for Relative Quantification in Real-Time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.S.; Moggridge, S.; Müller, T.; Sorensen, P.H.; Morin, G.B.; Krijgsveld, J. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nature Protocols 2019, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chear, S.; Perry, S.; Wilson, R.; Bindoff, A.; Talbot, J.; Ware, T.L.; Grubman, A.; Vickers, J.C.; Pébay, A.; Ruddle, J.B.; et al. Lysosomal alterations and decreased electrophysiological activity in CLN3 disease patient-derived cortical neurons. Dis Model Mech 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang da, W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Morris, J.H.; Cook, H.; Kuhn, M.; Wyder, S.; Simonovic, M.; Santos, A.; Doncheva, N.T.; Roth, A.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D362–D368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | UniProt Accession | Gene Name | FDR | FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP9 signalosome complex subunit 2 | A2AQE4 | Cops2 | 0.030 | 1.9 |

| Nuclear pore membrane glycoprotein 210 | Q9QY81 | Nup210 | 0.031 | 1.8 |

| Centromere protein V | Q9CXS4 | Cenpv | 0.047 | 1.7 |

| Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | Q64345 | Ifit3 | 0.004 | 0.7 |

| DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 17 | Q91WT4 | Dnajc17 | 0.002 | 0.7 |

| Signal recognition particle 19 kDa protein | Q9D104 | Srp19 | 0.013 | 0.7 |

| DENN domain-containing protein 4C | A6H8H2 | Dennd4c | 0.032 | 0.7 |

| Survival of motor neuron-related-splicing factor 30 | Q8BGT7 | Smndc1 | 0.009 | 0.7 |

| CDGSH iron-sulfur domain-containing protein 2 | Q9CQB5 | Cisd2 | 0.004 | 0.7 |

| Protein FAM102B | Q8BQS4 | Fam102b | 0.003 | 0.6 |

| CDGSH iron-sulfur domain-containing protein 3, mitochondrial | B1AR13 | Cisd3 | 0.044 | 0.6 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(O) subunit gamma-4 | P50153 | Gng4 | 0.021 | 0.6 |

| Protein KHNYN | Q80U38 | Khnyn | 0.005 | 0.6 |

| Alpha-amylase 1 | P00687 | Amy1 | 0.046 | 0.6 |

| Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 | Q64339 | Isg15 | 0.036 | 0.5 |

| DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 14 | Q149L6 | Dnajb14 | 0.050 | 0.5 |

| Chromosome alignment-maintaining phosphoprotein 1 | Q8K327 | Champ1 | 0.025 | 0.4 |

| Protein FAM162A | Q9D6U8 | Fam162a | 0.011 | 0.4 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 | P00520 | Abl1 | 0.006 | 0.4 |

| Transmembrane prolyl 4-hydroxylase | Q8BG58 | P4htm | 0.034 | 0.3 |

| Unconventional myosin-Ic | Q9WTI7 | Myo1c | 0.037 | 0.3 |

| von Willebrand factor | Q8CIZ8 | Vwf | 0.009 | 0.2 |

| Protein FAM98A | Q3TJZ6 | Fam98a | 0.015 | 0.2 |

| Protein | UniProt Accession | Gene Name | FDR | FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein phosphatase 1J | Q149T7 | Ppm1j | 0.004 | 2.1 |

| Four and a half LIM domains protein 2 | O70433 | Fhl2 | 0.043 | 1.9 |

| YjeF N-terminal domain-containing protein 3 | F6W8I0 | Yjefn3 | 0.044 | 1.9 |

| Muscular LMNA-interacting protein | V9GWW6 | Mlip | 0.047 | 1.7 |

| Rho GTPase activating protein 6, isoform CRA_b | G3UZI7 | Arhgap6 | 0.012 | 0.7 |

| Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2C | Q69ZS6 | Sv2c | 0.022 | 0.7 |

| Sodium-dependent dopamine transporter | Q61327 | Slc6a3 | 0.040 | 0.7 |

| Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 13 | Q5SS80 | Dhrs13 | 0.026 | 0.7 |

| Gamma-synuclein | Q9Z0F7 | Sncg | 0.001 | 0.7 |

| Hephaestin | Q9Z0Z4 | Heph | 0.003 | 0.6 |

| Wolframin | Q3UN10 | Wfs1 | 0.008 | 0.6 |

| ATP-sensitive inward rectifier potassium channel 10 | Q9JM63 | Kcnj10 | 0.014 | 0.6 |

| Lipid phosphate phosphatase-related protein type 1 | Q8BFZ2 | Lppr1 | 0.001 | 0.6 |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor kinase substrate 8-like protein 1 | Q8R5F8 | Eps8l1 | 0.020 | 0.6 |

| Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 5 | Q9D387 | Lamp5 | 0.009 | 0.6 |

| Synaptic vesicular amine transporter | Q8BRU6 | Slc18a2 | 0.049 | 0.6 |

| Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | Q61704 | Itih3 | 0.002 | 0.6 |

| Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 5 | Q9JJF0 | Nap1l5 | 0.001 | 0.6 |

| ProSAAS | Q9QXV0 | Pcsk1n | 0.004 | 0.6 |

| Synaptic vesicle membrane protein VAT-1 homolog-like | Q80TB8 | Vat1l | 0.007 | 0.6 |

| Leucine-rich repeat serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | Q5S006 | Lrrk2 | 0.036 | 0.6 |

| Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase receptor Ret | P35546 | Ret | 0.019 | 0.6 |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase-like 4 | Q9CXG3 | Ppil4 | 0.042 | 0.6 |

| ERC protein 2 | Q6PH08 | Erc2 | 0.029 | 0.6 |

| Proenkephalin-A | P22005 | Penk | 0.029 | 0.6 |

| Cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 1 | P62965 | Crabp1 | 0.020 | 0.5 |

| Protein FAM102B | Q8BQS4 | Fam102b | 0.038 | 0.5 |

| Protein AW551984 | Q8BGF0 | AW551984 | 0.013 | 0.5 |

| 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase type 2 | Q8JZV9 | Bdh2 | 0.007 | 0.5 |

| Leukocyte elastase inhibitor B | Q8VHP7 | Serpinb1b | 0.007 | 0.5 |

| BAI1-associated protein 3 | S4R1E7 | Baiap3 | 0.021 | 0.5 |

| Neuroglobin | Q9ER97 | Ngb | 0.001 | 0.4 |

| Protein Krt78 | E9Q0F0 | Krt78 | 0.021 | 0.4 |

| Neurotensin/neuromedin N | Q9D3P9 | Nts | 0.006 | 0.4 |

| Immunoglobulin superfamily member 1 | Q7TQA1 | Igsf1 | 0.010 | 0.3 |

| Rab GTPase-binding effector protein 2 | Q91WG2 | Rabep2 | 0.028 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).