Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

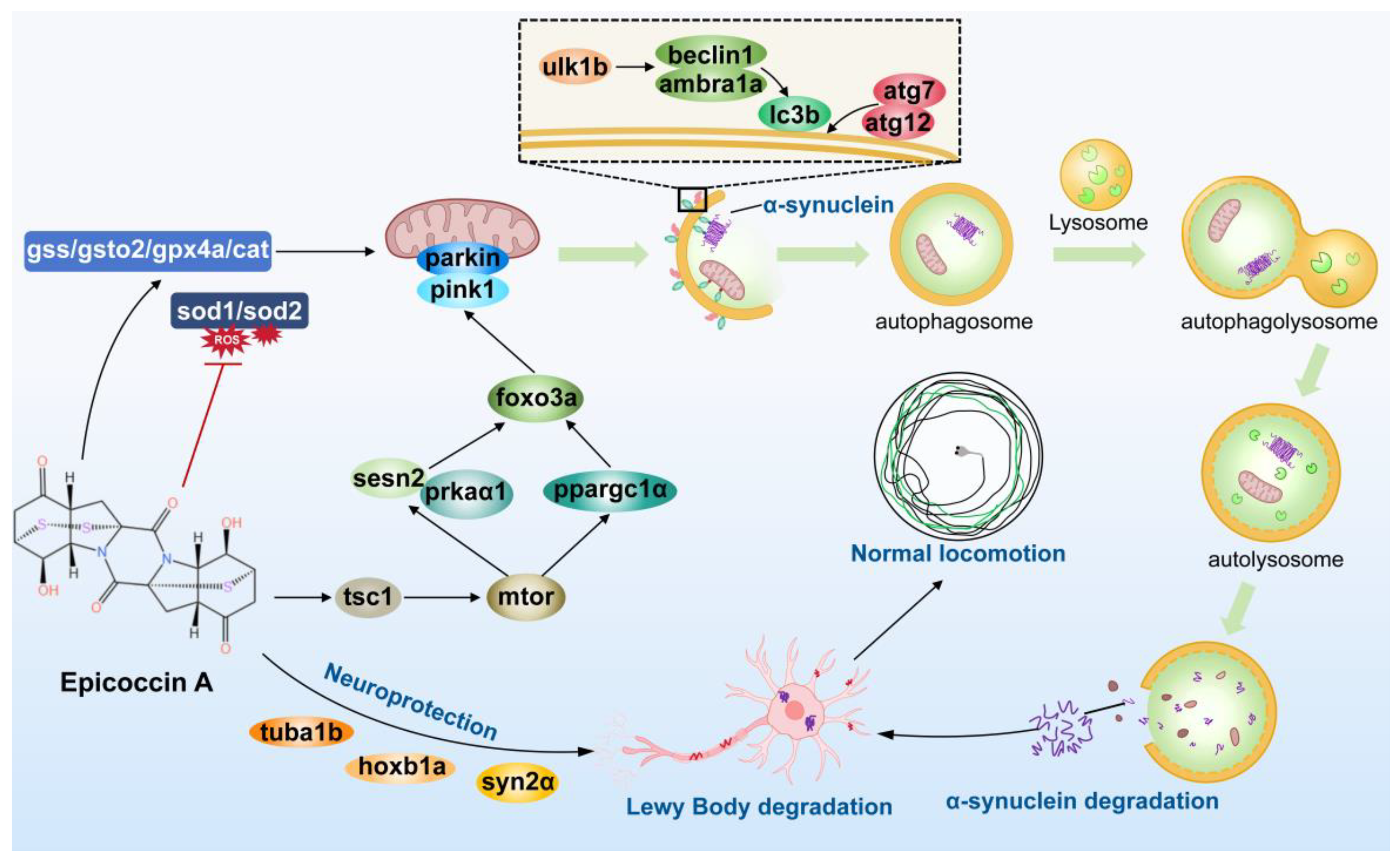

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Epicoccin A on the Loss of DA Neurons in PD

2.2. Effect of Epicoccin A on Nervous System Injury in PD

2.3. Effect of Epicoccin A on Neural Vasculature Loss in PD

2.4. Effect of Epicoccin A on Generation of ROS in Zebrafish PD Model

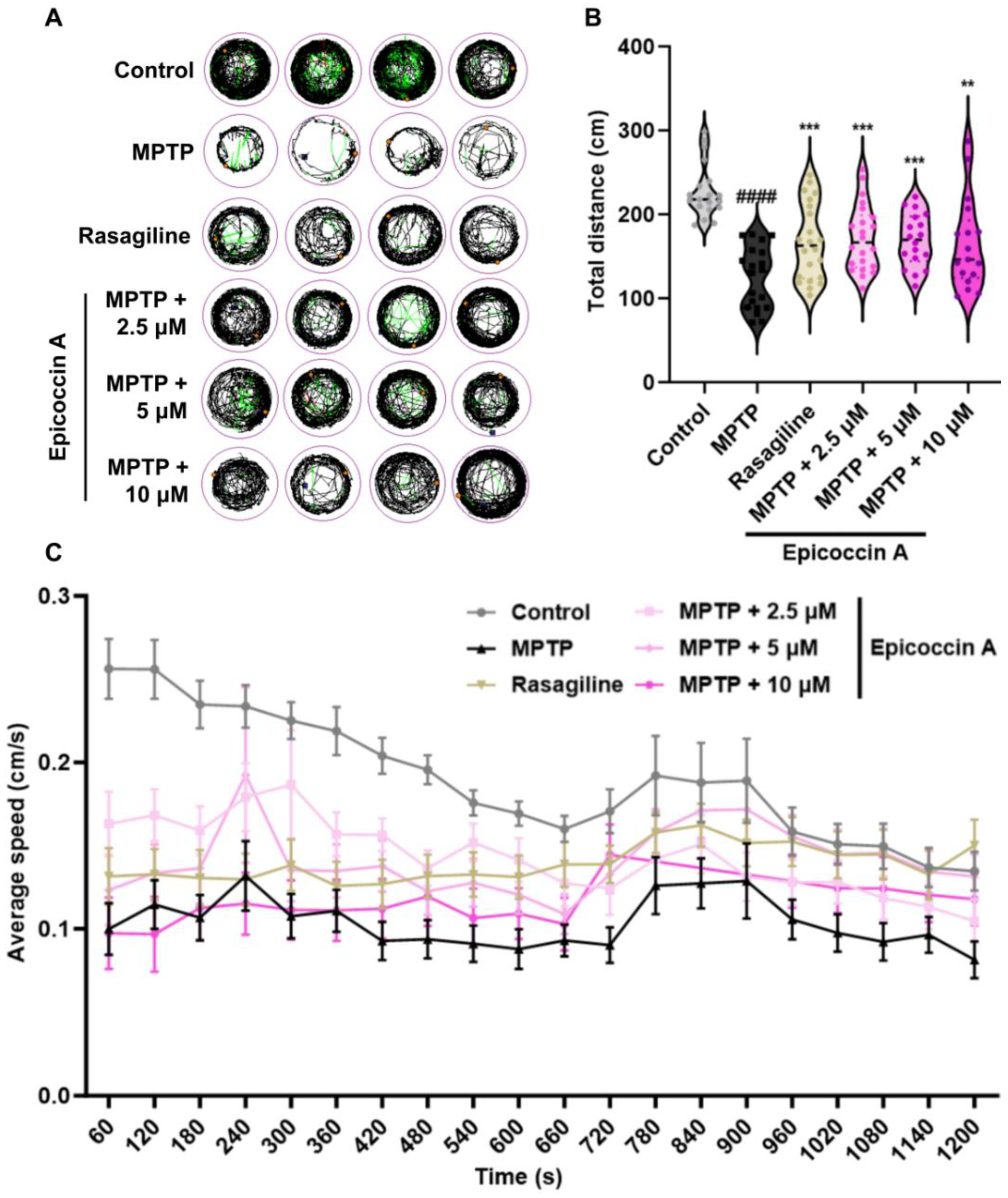

2.5. Effect of Epicoccin A on Locomotor Impairment in PD

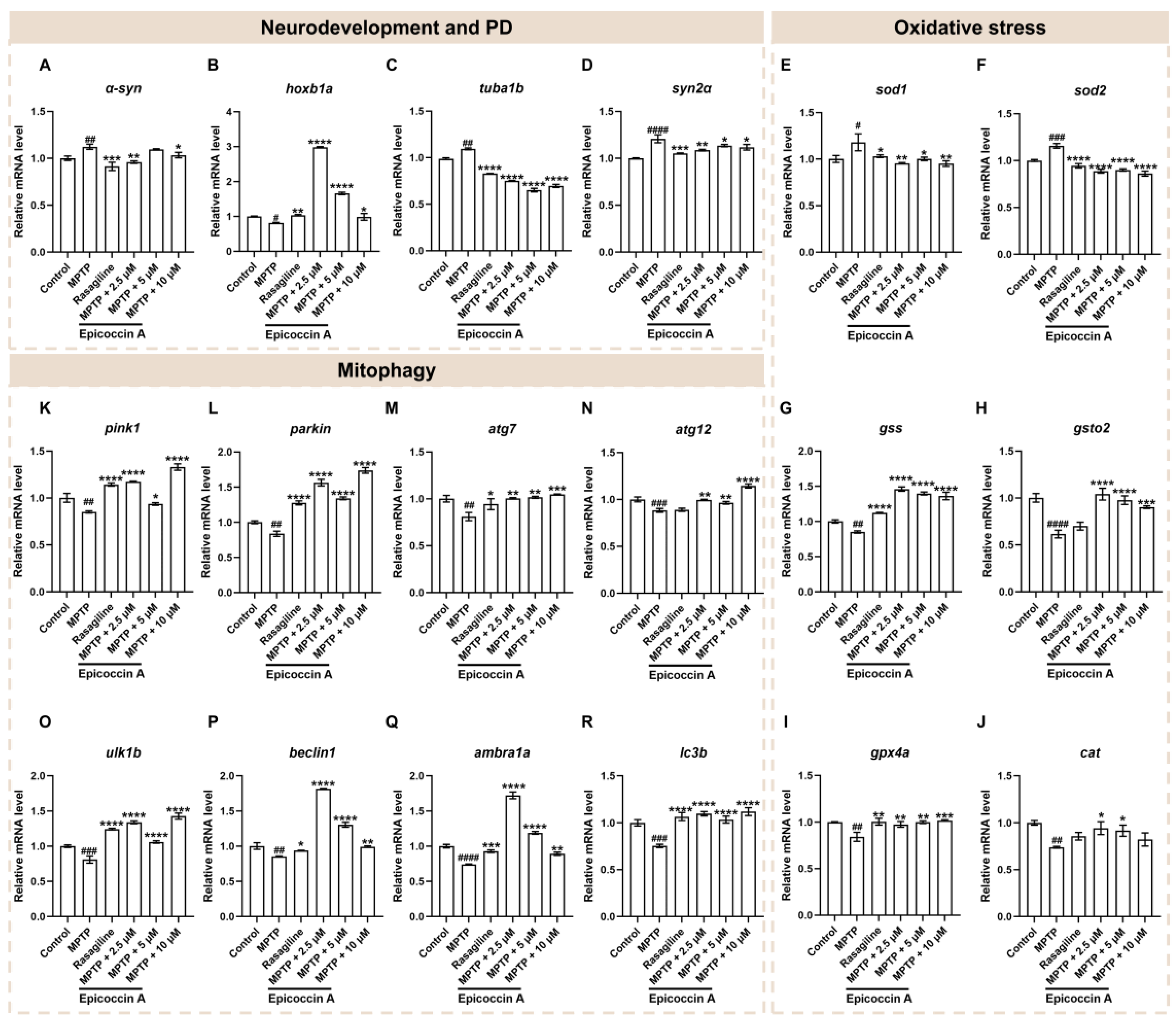

2.6. Effects of Epicoccin A on the Abnormal Expressions of Genes Related to Neurodevelopment and PD

2.7. Effect of Epicoccin A on the Dysregulated Expressions of Genes Related to Oxidative Stress

2.8. Effect of Epicoccin A on the Aberrant mRNA Levels of Genes Related to Mitophagy

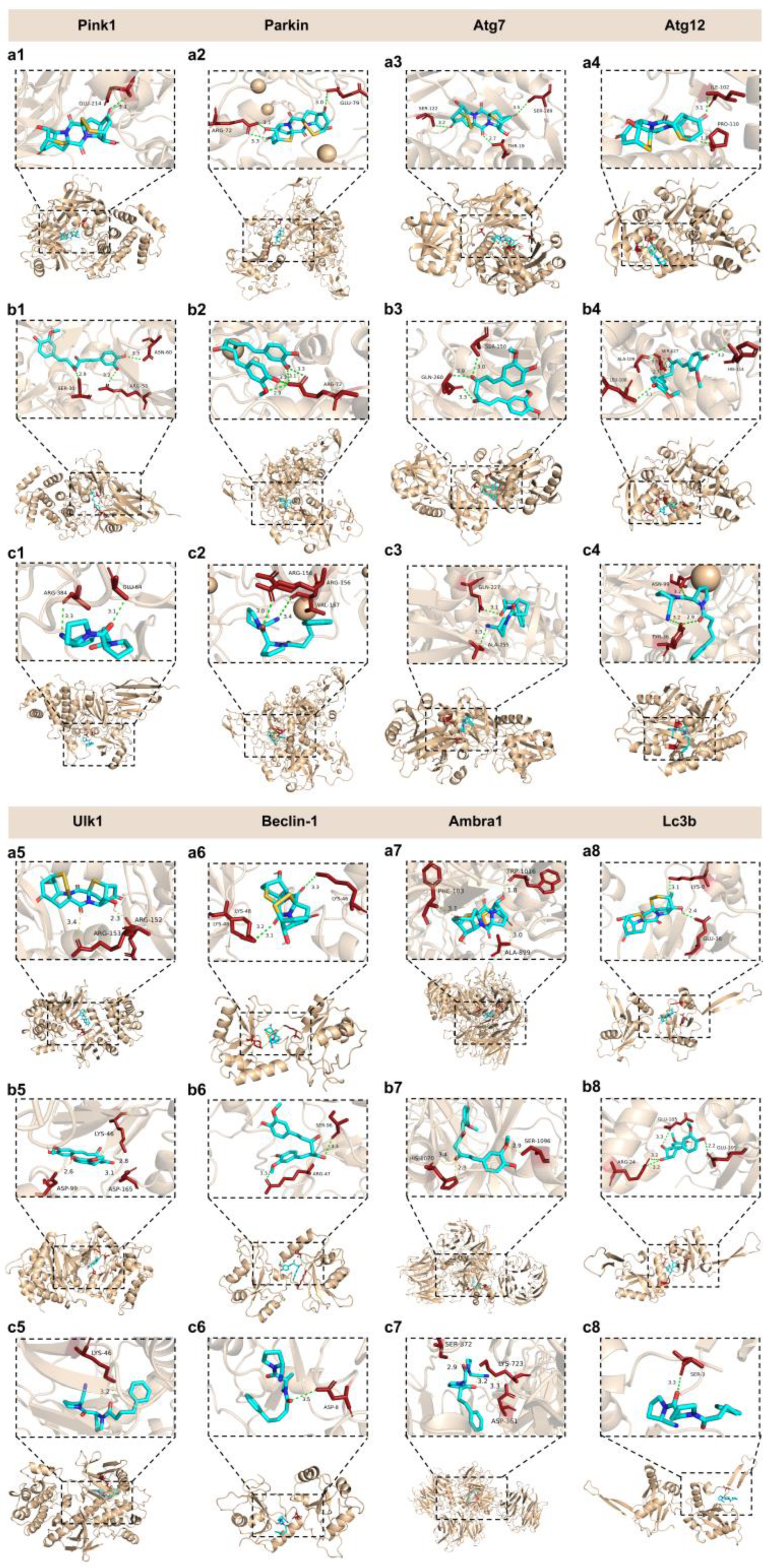

2.9. Interaction Between Epicoccin A and Mitophagy Regulators

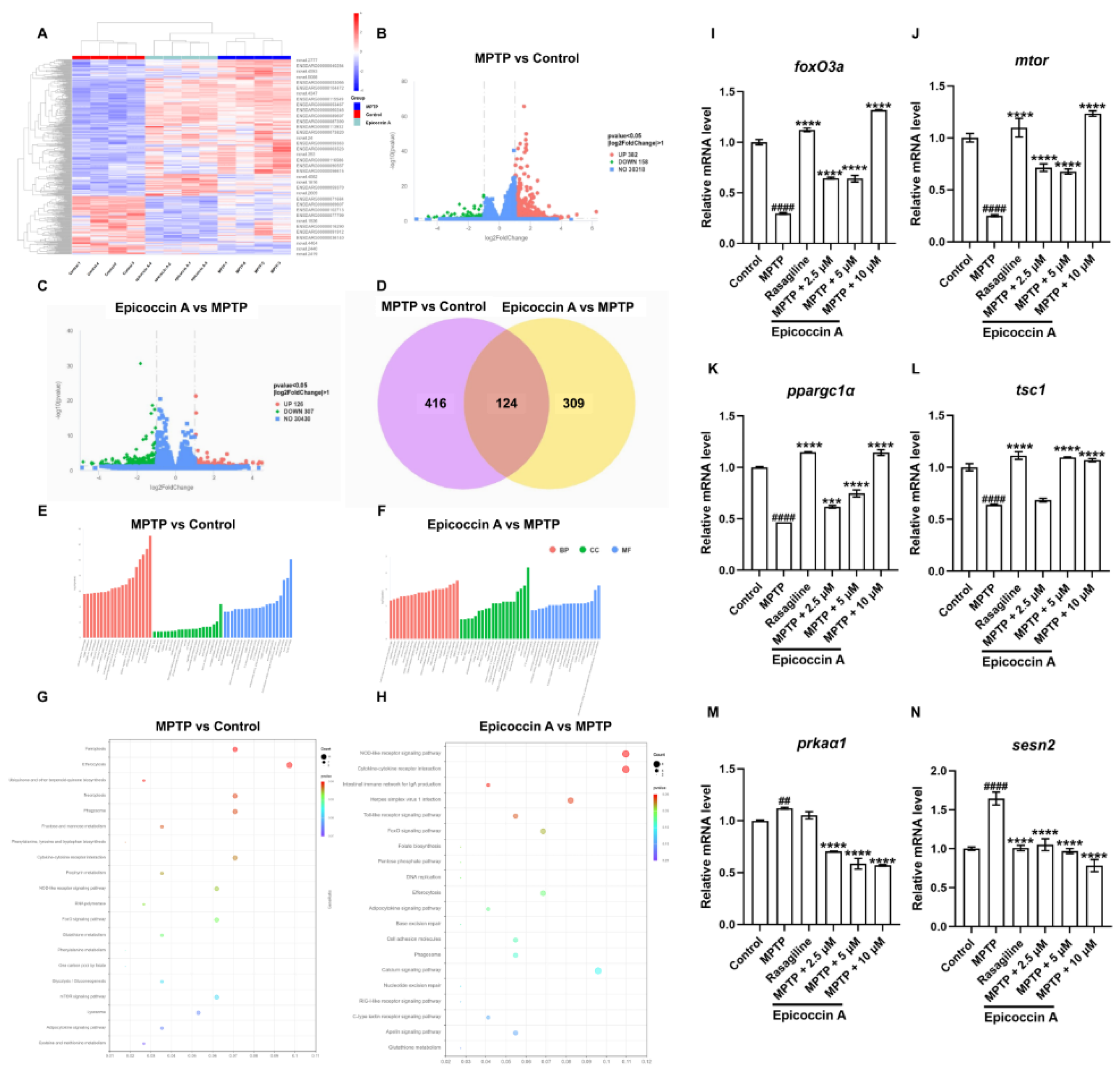

2.10. Functional Classification and Transcriptome Annotation and Verification

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation of Epicoccin A

4.3. Animals

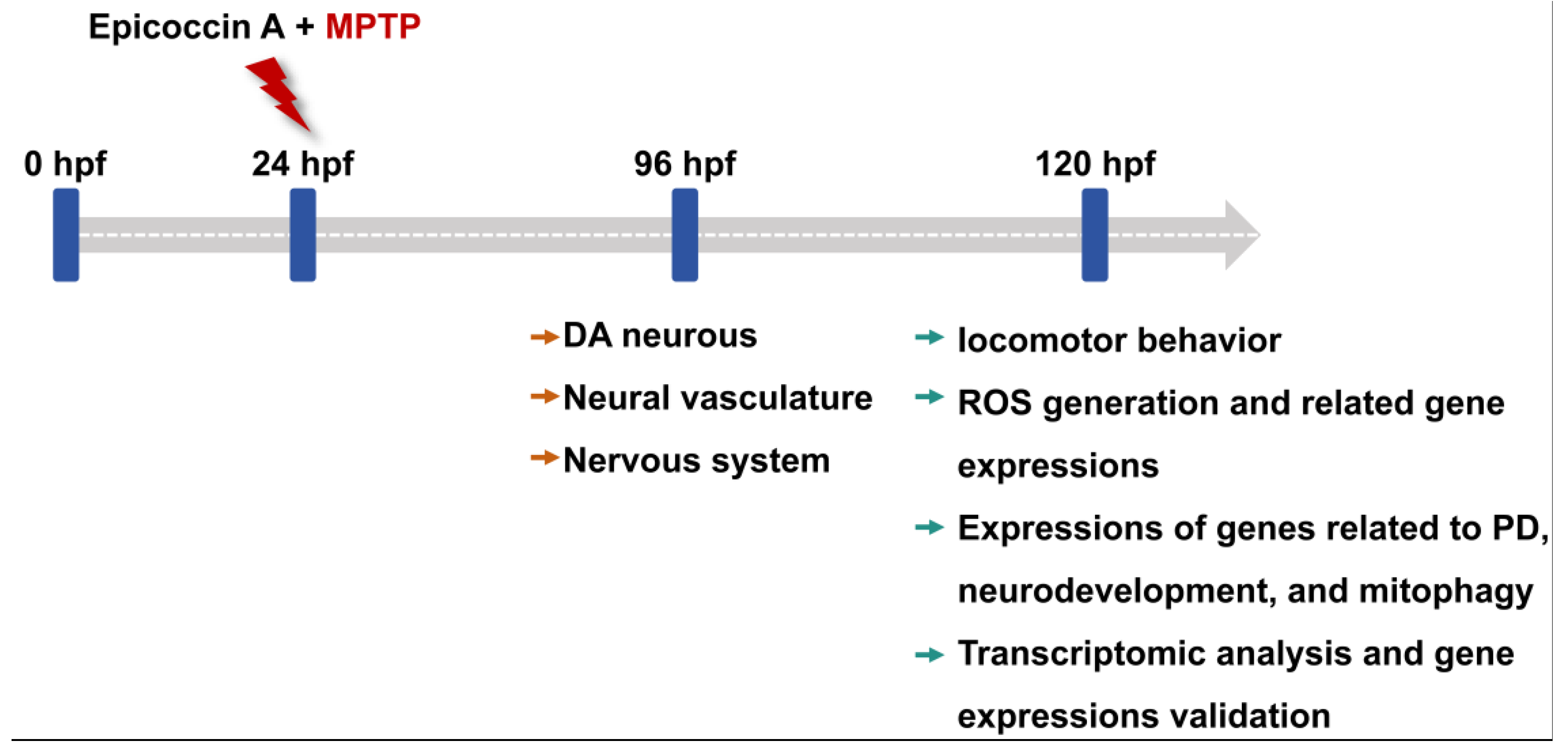

4.4. MPTP and Epicoccin A Treatments

4.5. Detection of Length of DA Neurons and Fluorescent Intensity of Nervous System

4.6. Assessment of Cerebral Vascular Development

4.7. Detection of ROS Generation in Zebrafish Larvae

4.8. Behavioral Testing

4.9. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.10. Molecular Docking

4.11. Transcriptome Analysis

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| LBs | Lewy bodies |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| hpf | hours post fertilization |

References

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Shaikh, M.F.; Othman, I. Emerging neuroprotective effect of metformin in Parkinson’s disease: A molecular crosstalk. Pharmacol Res. 2020, 152, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Paudel, Y.N.; Piperi, C. Emerging role of S100B protein implication in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijaz, B.A.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.A. Initiation and propagation of α-synuclein aggregation in the nervous system. Mol Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, M.X.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease and related α-synucleinopathies. Neurosci Lett. 2019, 709, 134316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.G. Motivation in Parkinson’s disease: apathetic before you know it. Brain. 2024, 147, 3266–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbazdar, Y.; Poyraz, Y.K.; Ozalp, O.; Nazli, D.; Ipekgil, D.; Cucun, G.; Ozhan, G. High-fat diet feeding triggers a regenerative response in the adult zebrafish brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 2486–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortone, A.; Vergani, A.A.; Ahmadipour, M.; Mannella, R.; Mazzoni, A. Dopamine depletion leads to pathological synchronization of distinct basal ganglia loops in the beta band. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023, 19, e1010645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, F.C. Treatment options for motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.P.; Youle, R.J. The role of PINK1-Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Nat Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, M.A.; Fallahi, A.; Soumbasis, A.; Bayne, A.N.; Trempe, J.F.; Fon, E.A. Mitochondrial import stress and PINK1-mediated mitophagy: the role of the PINK1-TOMM-TIMM23 supercomplex. Autophagy. 2024, 20, 1903–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.N.; Chaturvedi, V.K.; Singh, P.; Singh, B.K.; Singh, M.P. Mucuna pruriens in Parkinson’s and in some other diseases: recent advancement and future prospective. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulaamane, Y.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Britel, M.R.; Maurady, A. In silico studies of natural product-like caffeine derivatives as potential MAO-B inhibitors/AA2AR antagonists for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Integr Bioinform. 2022, 19, 20210027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirerol-Piquer, M.S.; Perez-Villalba, A.; Duart-Abadia, P.; Belenguer, G.; Gómez-Pinedo, U.; Blasco-Chamarro, L.; Carrillo-Barberà, P.; Pérez-Cañamás, A.; Navarro-Garrido, V.; Dehay, B.; Vila, M.; Vitorica, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, F.; Fariñas, I. Age-dependent progression from clearance to vulnerability in the early response of periventricular microglia to α-synuclein toxic species. Mol Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilbaud, E.; Sarosiek, K.A.; Galluzzi, L. Inflammation and mitophagy are mitochondrial checkpoints to aging. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.J.; Tsukruk, V.V. Trainable bilingual synaptic functions in bio-enabled synaptic transistors. ACS Nano. 2023, 17, 18883–18892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, G.; Paciotti, S.; Gatticchi, L.; Parnetti, L. The vicious cycle between α-synuclein aggregation and autophagic-lysosomal dysfunction. Mov Disord. 2020, 35, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shejul, P.P.; Raheja, R.K.; Doshi, G.M. An update on potential antidepressants derived from marine natural products. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2023, 23, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Syeda, A.; Topgyal, T.; Gaur, N.; Islam, A. Parkinson’s disease: A current perspectives on Parkinson’s disease and key bioactive natural compounds as future potential drug candidates. Curr Drug Targets. 2022, 23, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, L.T.; Martins, R.D.; Lima, L.M.; Ghizelini, A.M.; Ferreira-Pereira, A.; Cotinguiba, F. Secondary metabolites diversity of Aspergillus unguis and their bioactivities: A potential target to be explored. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.P.; Su, R.; Chen, M.T.; Li, J.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, F.F.; Liu, J.; Xu, C.J.; Li, W.S.; Rao, Y.; Huang, L. Ent-eudesmane sesquiterpenoids with anti-neuroinflammatory activity from the marine-derived fungus Eutypella sp. F0219. Phytochemistry. 2024, 223, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.P.; Li, X.M.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Wang, B.G. Cytotoxic thiodiketopiperazine derivatives from the deep sea-derived fungus Epicoccum nigrum SD-388. Mar Drugs. 2020, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Che, Y.; Liu, X. Epicoccins A-D, epipolythiodioxopiperazines from a Cordyceps-colonizing isolate of Epicoccum nigrum. J Nat Prod. 2007, 70, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T.; Che, Q.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Amphiepicoccins A-J: epipolythiodioxopiperazines from the fish-gill-derived fungus Epicoccum nigrum HDN17-88. J Nat Prod. 2020, 83, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Rubalcava, P.A.; Tejeda-Martínez, A.R.; González-Reynoso, O.; Nápoles-Medina, A.Y.; Chaparro-Huerta, V.; Flores-Soto, ME. β-Caryophyllene decreases neuroinflammation and exerts neuroprotection of dopaminergic neurons in a model of hemiparkinsonism through inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023, 117, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savchenko, V. ; Kalinin, S, Boullerne, A.I.; Kowal, K.; Lin, S.X.; Feinstein, D.L. Effects of the CRMP2 activator lanthionine ketimine ethyl ester on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. J Neuroimmunol, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Xia, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Sik, A.; Jin, M. Anti-Parkinson’s disease activity of phenolic acids from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver leaf extracts and their autophagy activation mechanism. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1425–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, R.; Hua, K.; Kalyn, M.; Cusson, V.M.; Anisman, H.; Ekker, M. Dopaminergic neurons regenerate following chemogenetic ablation in the olfactory bulb of adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresse, E.; Marturia-Navarro, J.; Sew, W.Q.; Cisquella-Serra, M.; Jaberi, E.; Riera-Ponsati, L.; Fauerby, N.; Hu, E.; Kretz, O.; Aznar, S.; Issazadeh-Navikas, S. Mitochondrial DNA damage triggers spread of Parkinson’s disease-like pathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2023, 4902–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyn, M.; Hua, K.; Mohd Noor, S.; Wong, C.E.; Ekker, M. Comprehensive analysis of neurotoxin-induced ablation of dopaminergic neurons in zebrafish larvae. Biomedicines. 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Ye H.; Jiang P.; Liu J.; Wang B.; Zhang S.; Sik A.; Li N.; Liu K.; Jin M. The alleviative effect of Calendula officinalis L. extract against Parkinson’s disease-like pathology in zebrafish via the involvement of autophagy activation. Front Neurosci, 5388. [CrossRef]

- Ijomone, O.K.; Oria, R.S.; Ijomone, O.M.; Aschner, M.; Bornhorst, J. Dopaminergic perturbation in the aetiology of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 2420–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.S.; Gao, L.; Han, Z.; Eleuteri, S.; Shi, W.; Shen, Y.; Song, Z.Y.; Su, M.; Yang, Q.; Qu, Y.; Simon, D.K.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, B. Ferroptosis in Parkinson’s disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Ageing Res Rev. 2023, 91, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Zhou, M.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; Shi, D. Protection by rhynchophylline against MPTP/MPP+-induced neurotoxicity via regulating PI3K/Akt pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 268, 113568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Bian, Y.; Feng, Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, L.; Hoi, M.P.; Ma, D.; Zhao, C.; Lee, S.M. Neuroprotective effects of BHDPC, a novel neuroprotectant, on experimental stroke by modulating microglia polarization. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019, 10, 2434–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Ji, X.; Zhang, B.; Sheng, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, K. Synergistic effects of Pb and repeated heat pulse on developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019, 172, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, J.; Hicks, A.A.; König, I.R.; Delcambre, S.; Lüth, T.; Schaake, S.; Wasner, K.; Ghelfi, J.; Borsche, M.; Vilariño-Güell, C.; Hentati, F.; Germer, E.L.; Bauer, P.; Takanashi, M.; Kostić, V.; Lang, A.E.; Brüggemann, N.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Pichler, I.; Rajput, A.; Hattori, N.; Farrer, M.J.; Lohmann, K.; Weissensteiner, H.; May, P.; Klein, C.; Grünewald, A. Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy distinguishes disease manifestation in PINK1/PRKN-linked Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2023, 146, 2753–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, S.; Arakawa, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Torii, S.; Tajima Sakurai, H.; Tsujioka, M.; Murohashi, M.; Shimizu, S. Association between Atg5-independent alternative autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. J Mol Biol. 2020, 432, 2622–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Perera, G.; Bhadbhade, M.; Halliday, G.M.; Dzamko, N. Autophagy activation promotes clearance of α-synuclein inclusions in fibril-seeded human neural cells. J Biol Chem. 2019, 294, 14241–14256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpartida, A.B.; Williamson, M.; Narendra, D.P.; Wade-Martins, R.; Ryan, B.J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease: From mechanism to therapy. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021, 46, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, A.S.; Ferreira, S.A.; Romero-Ramos, M. Periphery and brain, innate and adaptive immunity in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Xue, G. The role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: current understanding and future therapeutic targets. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1347987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, W. Marine-derived natural compounds for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mar Drugs. 2019, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Tripathi, P.; Yadawa, A.K.; Singh, S. Promising polyphenols in Parkinson’s disease therapeutics. Neurochem Res. 2020, 45, 1731–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, C.K.; Uti, D.E.; Mukherjee, D.; Alqahtani, T.; Alqahtani, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Akash, S. Unveiling nature’s potential: promising natural compounds in Parkinson’s disease management. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023, 115, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, N.A.; Kumar, J.; Teoh, S.L. Parkinson’s disease model in zebrafish using intraperitoneal MPTP injection. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1236049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Xie, S.P.; Saw, W.T.; Ho, P.G.; Wang, H.; Lei, Z.; Yi, Z.; Tan, E.K. The therapeutic implications of tea polyphenols against dopamine (DA) neuron degeneration in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Cells. 2019, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eyk, C.L.; Corbett, M.A.; Frank, M.S.; Webber, D.L.; Newman, M.; Berry, J.G.; Harper, K.; Haines, B.P.; McMichael, G.; Woenig, J.A.; MacLennan, A.H.; Gecz, J. Targeted resequencing identifies genes with recurrent variation in cerebral palsy. NPJ Genom Med. 2019, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Pan, Z.J.; Qin, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, W.F.; Sun, Z.Y.; Shi, H.B. Evaluation of BDE-47-induced neurodevelopmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023, 30, 54022–54034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, S.; Gao, X.; Paudel, Y.N.; Zhang, P.; Wang, R.; Liu, K.; Jin, M. Neuroprotective effect of YIAEDAER peptide against Parkinson’s disease like pathology in zebrafish. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y. Unraveling the role of neuregulin-mediated astrocytes-OPCs axis in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration and Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.B.; Wankhede, N.L.; Bishoyi, A.K.; Ballal, S.; Kalia, R.; Arya, R.; Kumar, S.; Khalid, M.; Gulati, M.; Umare, M.; Taksande, B.G.; Upaganlawar, A.B.; Umekar, M.J.; Kopalli, S.R.; Fareed, M.; Koppula, S. Emerging biophysical techniques for probing synaptic transmission in neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroscience. 2025, 565, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brash-Arias, D.; García, L.I.; Pérez-Estudillo, C.A.; Rojas-Durán, F.; Aranda-Abreu, G.E.; Herrera-Covarrubias, D.; Chi-Castañeda, D. The role of astrocytes and alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: A review. NeuroSci. 2024, 5, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Kisler, K.; Montagne, A.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, D.J. Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Wei, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Gao, S.; Ren, K. Synaptic secretion and beyond: targeting synapse and neurotransmitters to treat neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 9176923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Song, J.; Chen, J.Y.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, L.; Xie, L.M.; Liao, Q.; Ye, R.D.; Chen, X.; Yan, Y.; Tan, J.; Heng, T.; Li, M.; Lu, J.H. Corynoxine B targets at HMGB1/2 to enhance autophagy for α-synuclein clearance in fly and rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023, 13, 2701–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Andromidas, F.; Mackinnon, B.E.; Myers, A.J.; Shaffer, M.M.; Brahimi, A.; Atashpanjeh, S.; Vazquez, T.L.; Le, T.; Jellison, E.Rv.; Staurovsky, S.; Koob, A.O. Astrocytes initiate autophagic flux and maintain cell viability after internalizing non-active native extracellular α-synuclein. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2024, 131, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzi, L.; Leri, M.; Cesaro, S.; Stefani, M.; Bucciantini, M.; Polverino, D. Insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the inhibition of α-synuclein aggregation by hydroxytyrosol. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020, 173, 113722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xin, C.; Tu, R.; Yan, H. Oxidative stress of mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2025, 764, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buneeva, O.; Fedchenko, V.; Kopylov, A.; Medvedev, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Focus on mitochondrial DNA. Biomedicines. 2020, 8, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Leem, E.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, S.R. Control of reactive oxygen species for the prevention of Parkinson’s disease: The possible application of flavonoids. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, P.R. Sources and triggers of oxidative damage in neurodegeneration. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021, 173, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, H.C.; Lin, K.J.; Kung, C.T.; Lin, T.K. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroprotection of polyphenols with respect to resveratrol in Parkinson’s disease. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Lu, B. Mechanisms and roles of mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019, 25, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonong, K.; Sobhon, P.; Sroyraya, M.; Chaithirayanon, K. Neuroprotective and neurorestorative effects of Holothuria scabra extract in the MPTP/MPP+-induced mouse and cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020, 14, 575459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Niu, B. NLRP3 Inflammasome deficiency alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress by promoting PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in allergic rhinitis mice and nasal epithelial cells. J Asthma Allergy. 2024, 17, 717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Barazzuol, L.; Giamogante, F.; Brini, M.; Calì, T. PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy, Ca2+ signalling, and ER-mitochondria contacts in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 1772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.W.; Lin, C.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Yang, H.B.; Hung, S.Y. Celastrol inhibits dopaminergic neuronal death of Parkinson’s disease through activating mitophagy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalma, B.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Rodriguez-Polanco, F.C.; Bhavsar, C.T.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Cararo-Lopes, E.; Farooq, S.A.; Levy, J.L.; Wek, R.C.; White, E.; Anthony, T.G. Autophagy-related 7 (ATG7) regulates food intake and liver health during asparaginase exposure. J Biol Chem. 2025, 301, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yi, H.; Liao, S.; He, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lei, Y. LC3B: A microtubule-associated protein influences disease progression and prognosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Song, J.X.; Sreenivasmurthy, S.G.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Chu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Song, J.; Zhuang, R.; Huang, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, M.; Wen, L.; Zhang, Y.W.; Liu, G. A Self-assembled α-synuclein nanoscavenger for Parkinson’s disease. ACS Nano. 2020, 14, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jia, Y.; Meng, S.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Pan, Z. Mechanisms of and potential medications for oxidative stress in ovarian granulosa cells: A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zheng, H. Role of FoxO transcription factors in aging and age-related metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, R.; Hardy, A.; Zur Nieden, N.I. The FOXO signaling axis displays conjoined functions in redox homeostasis and stemness. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021, 169, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, R.; Gao, C.; Tian, Y.N.; Hu, R.G.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Li, Y. Unraveling the function of TSC1-TSC2 complex: implications for stem cell fate. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, W.; Bao, X. Sestrin2: multifaceted functions, molecular basis, and its implications in liver diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Lin, M.; Gu, W.; Su, Z.; Duan, Y.; Song, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F. The rules and regulatory mechanisms of FOXO3 on inflammation, metabolism, cell death and aging in hosts. Life Sci. 2023, 328, 121877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Xiong, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Peng, D. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of FOXO3 enhances mitophagy and drives hormone resistance in endometrial cancer. Mol Med. 2024, 30, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wang, C. Marine-derived fungus Exserohilum sp. M1-6 from the Guangxi Beibu Gulf. Key Laboratory of Chemistry and Engineering of Forest Products, State Ethnic Affairs Commission & Guangxi Key Laboratory of Chemistry and Engineering of Forest Products/Guangxi Collaborative Innovation Center for Chemistry and Engineering of Forest Products, Guangxi Minzu University, Nanning, Guangxi, China, 2025 (manuscript in preparation; to be submitted).

- Ross Stewart, K.M.; Walker, S.L.; Baker, A.H.; Riley, P.R.; Brittan, M. Hooked on heart regeneration: the zebrafish guide to recovery. Cardiovasc Res. 2022, 118, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Shamoto-Nagai, M. Rasagiline and selegiline modulate mitochondrial homeostasis, intervene apoptosis system and mitigate α-synuclein cytotoxicity in disease-modifying therapy for Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020, 127, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Pol, A.; Kalaria, D.; Date, A.A.; Kalia, Y.; Patravale, V. Microemulsion-based gel for the transdermal delivery of rasagiline mesylate: In vitro and in vivo assessment for Parkinson’s therapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2021, 165, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Kang, J.; Qiu, J.; Yang, W.; Wu, J.; Ji, D.; Yu, Y.; Ke, W.; Shi, X.; Wei, Y. Developmental exposure to BDE-99 hinders cerebrovascular growth and disturbs vascular barrier formation in zebrafish larvae. Aquat Toxicol. 2019, 214, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzi, L.; Rastelli, G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Receptor | Ligand | Binding Score (kcal/mol) | Binding Site (X, Y, Z) |

Docking Region Size (X, Y, Z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pink1 | epicoccin A | -8.8 | 60.658, 7.027, 18.506 | 94.85 Å, 72.26 Å, 73.77 Å |

| curcumin | -8.4 | |||

| KYP-2047 | -8.0 | |||

| Parkin | epicoccin A | -9.9 | -20.445, 3.618, 25.773 | 111.65 Å, 101.01 Å, 111.65 Å |

| curcumin | -8.0 | |||

| KYP-2047 | -8.4 | |||

| epicoccin A | -8.3 | |||

| Atg7 | curcumin | -7.3 | 18.923, -50.614, 19.942 | 94.15 Å, 70.23 Å, 94.15 Å |

| KYP-2047 | -7.0 | |||

| epicoccin A | -8.7 | |||

| Atg12 | curcumin | -7.1 | 155.126, 4.886, 19.741 | 82.25 Å, 82.25 Å, 82.25 Å |

| KYP-2047 | -7.3 | |||

| Ulk1 | epicoccin A | -8.2 | 0.217, 35.817, 40.043 | 85.75 Å, 74.86 Å, 54.44 Å |

| curcumin | -8.3 | |||

| KYP-2047 | -9.0 | |||

| Beclin-1 | epicoccin A | -8.6 | -4.976, 0.256, -17.797 | 50.40 Å, 66.15 Å, 48.30 Å |

| curcumin | -7.1 | |||

| KYP-2047 | -7.2 | |||

| epicoccin A | -8.4 | |||

| Ambra1 | curcumin | -8.3 | 126.784, 129.570, 130.763 | 90.21 Å, 90.21 Å, 123.55 Å |

| KYP-2047 | -8.6 | |||

| Lc3b | epicoccin A | -7.2 | 132.28, 94.936, 136.924 | 37.66 Å, 118.65 Å, 65.91 Å |

| curcumin | -7.7 | |||

| KYP-2047 | -7.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).