Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study investigates the presence of undeclared meat species in beef sausages and analyzes the impact of poultry meat addition on the fatty acid composition. A total of 68 beef sausage samples were analyzed, comprising 43 industrial and 25 traditional (homemade) sausages. Using the LCD Array Analysis System, Meat 5.0, we detected that 52.94% of the samples contained meat from other species, with poultry being the most frequently added (45.55%), followed by mutton (4.41%) and turkey (2.9%). Notably, 46.42% of industrial sausages with added meat and 100% of homemade sausages with mixed meat were undeclared, highlighting significant mislabeling concerns. Fatty acid analysis with GC-FID revealed that sausages with poultry meat exhibited lower levels of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and higher polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly linoleic (C18:2) and alfa-linolenic (C18:3) acids. The inclusion of poultry meat significantly reduced the proportion of palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) acids while increasing unsaturated fatty acids. As the percentage of poultry meat increased, SFAs decreased from 54.08% (at 10% poultry) to 29.55% (at 90%), while PUFAs rose from 4.09% to 26.64%. These findings indicate that poultry addition enhances the nutritional profile of sausages by improving the fatty acid balance. This study highlights the need for stricter labeling regulations to ensure consumer transparency. Future research should explore these modified products' sensory and quality attributes to assess their market acceptance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Sampling

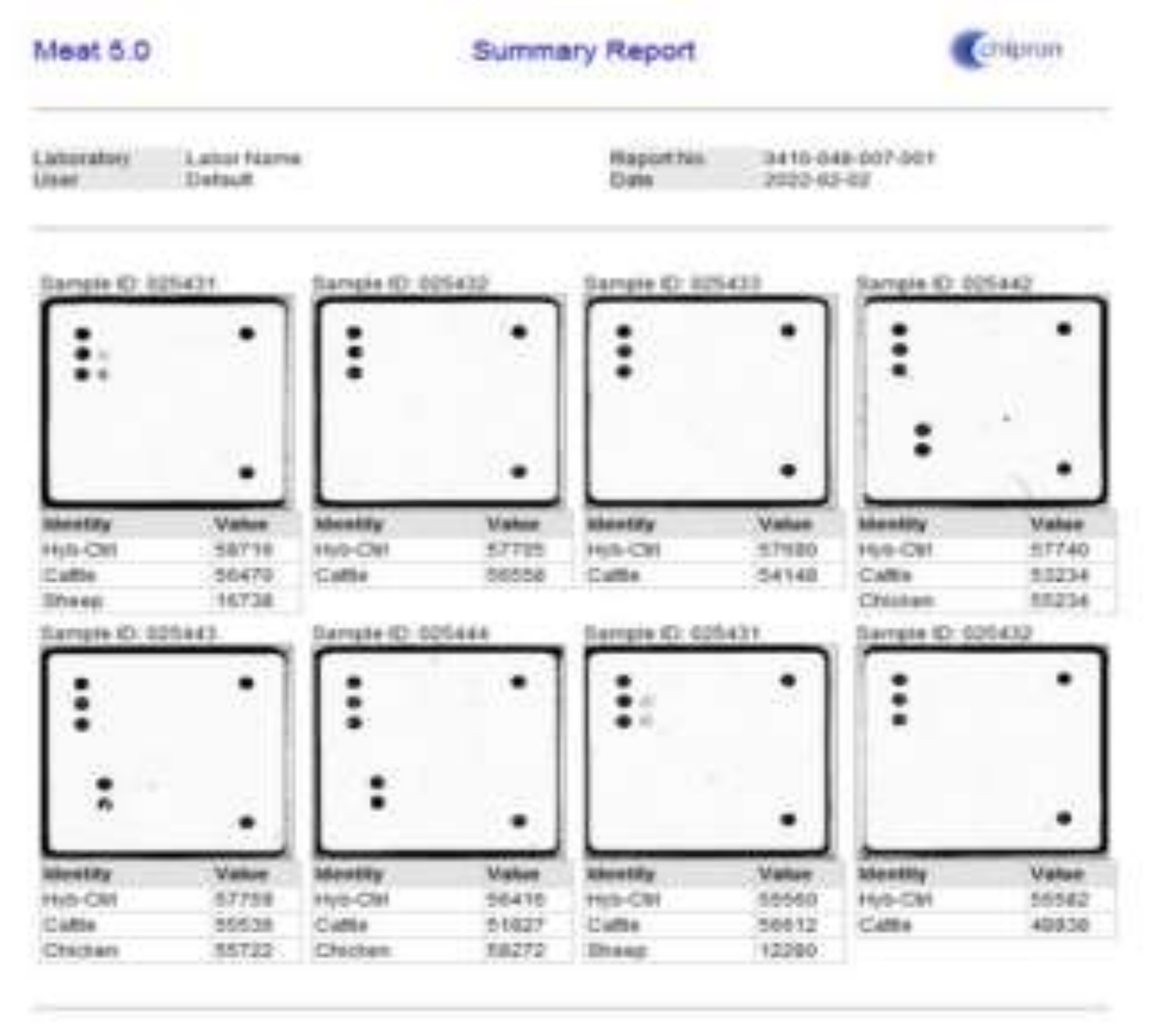

2.2. Chipron LCD Array Analysis System, Meat 5.0 – a DNA-Based Identification of 24 Animal Species in Meat Products

2.2.1. Extraction of Sample

2.2.2. LCD -Array

2.3. Gas Chromatography–Flame Ionization Detector (GC/FID).

Extraction Procedure and Derivatization of Fatty Acids

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Detection of DNA of species in beef sausages

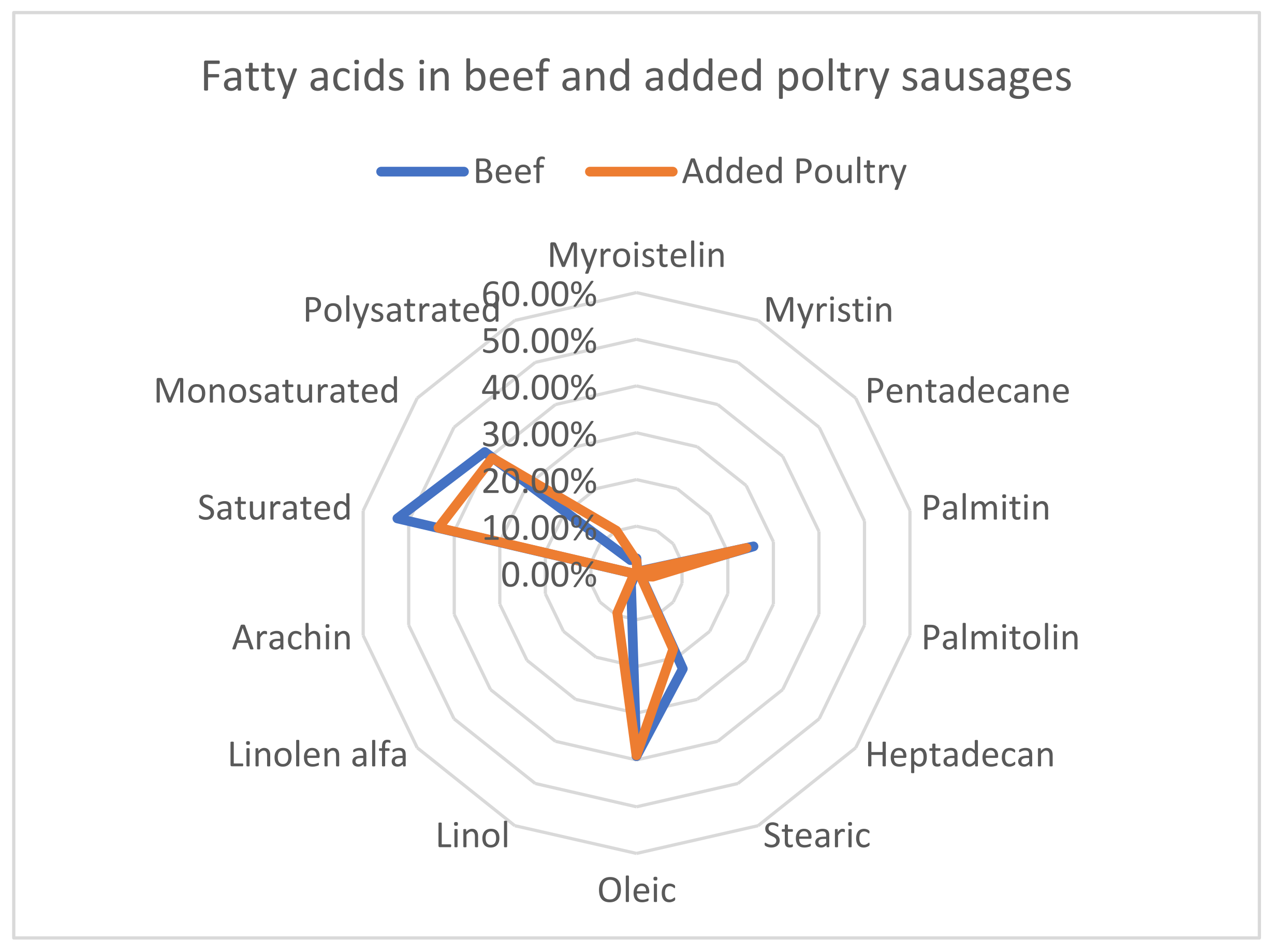

3.2. Prevalence of the Fatty Acid In Sausages Made With 100 % Beef And Added Poultry Meat

3.3. The fatty Acid Profile Depends on the % of Chicken Meat Addition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geiker, N.R.W.; Bertram, H.C.; Mejborn, H.; Dragsted, L.O.; Kristensen, L.; Carrascal, J.R.; Bügel, S.; Astrup, A. Meat and Human Health—Current Knowledge and Research Gaps. Foods 2021, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajomiwe, N.; Boland, M.; Phongthai, S.; Bagiyal, M.; Singh, J.; Kaur, L. Protein Nutrition: Understanding Structure, Digestibility, and Bioavailability for Optimal Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo, J. Sausages Nutrition, Safety, Processing and Quality Improvement. Foods 2021, 10, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpan, P. Trends in Sausage Production. Afr. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, J.J.; E Paine, K.; Garrett, S.D.; Brown, H.M. Detection of meat species using TaqMan real-time PCR assays. Meat Sci. 2004, 68, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Özlü, H.; Çevik, B.; Atasever, M.; Sarıalioğlu, M.F.; Polat, B.A. Investigation of meat species adulteration in beef-based meat products via real-time PCR in Türkiye. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods 2023, 15, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, J.S.; Soares, S.; Mafra, I.; Oliveira, B. Assessing the variability of the fatty acid profile and cholesterol content of meat sausages. La Rivista Italiana dee sostanze grasse - L. XC - B/CMB. 2014.

- Berisha, K.; Gashi, A.; Mednyánszky, Z.; Bytyqi, H.; Sarkadi, S. (2023): Nutritional characterization of homemade beef sausage based on amino acid, biogenic amines, and fatty acid composition. Acta Alimentaria. 2023, Volume 52: Issue 3.

- de Almeida, J.C.; Perassolo, M.S.; Camargo, J.L.; Bragagnolo, N.; Gross, J.L. Fatty acid composition and cholesterol content of beef and chicken meat in Southern Brazil. Rev. Bras. de Ci?ncias Farm. 2006, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Belichovska, D.; Pejkovski, Z.; Silovska-Nikolova, A.; Belichovski, K. Chemical and fatty acid composition of poultry meat and pork fatback as a raw material for the production of frankfurters. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 10, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun, A.; Måge, I.; Schmidt, W.F.; Temiz, H.T.; Li, L.; Kim, H.-Y.; Nilsen, H.; Biancolillo, A.; Aït-Kaddour, A.; Sikorski, M.; et al. Fraud in Animal Origin Food Products: Advances in Emerging Spectroscopic Detection Methods over the Past Five Years. Foods 2020, 9, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, M.; Bubli, S.Y.; Khan, M.S. Mechanisms and Health Aspects of Food Adulteration: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatin, G.; Théolier, J.; Dominguez, S.; Godefroy, S.B. Quantification of beef in products sold in Canada declaring multiple meat species – Regulatory and consumer implications related to accurate labeling. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100375. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Food Safety Regulations and Consumer Confidence. Int. J. Livest. Policy 2024, 2, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin, E.; Wilson, A.; Coveney, J.; Webb, T. Trust in and through labelling – a systematic review and critique. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 318–338. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation no. 09/2013 on labelling, presentation and advertising and food products. Ministry of Trade and Industry, Government, Republic of Kosovo. 2013.

- Official Journal of the European Union - Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. 2021.

- El Sheikha, A.F.; Mokhtar, N.F.K.; Amie, C.; Lamasudin, D.U.; Isa, N.M.; Mustafa, S. Authentication technologies using DNA-based approaches for meats and halal meats determination. Food Biotechnol. 2017, 31, 281–315. [Google Scholar]

- Adenuga, B.M.; Montowska, M. A systematic review of DNA-based methods in authentication of game and less common meat species. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2112–2160. [Google Scholar]

- Haifeng.; Suli, Zh. Determination of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) in Milk Matrix Using an Agilent 5977E GC/MS 2014.

- Guidance for Industry, Q2B Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), November 1996 ICH.

- Szyłak, A.; Kostrzewa, W.; Bania, J.; Tabiś, A. Do You Know What You Eat? Kebab Adulteration in Poland. Foods 2023, 12, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, L.-O.; Bin He, X.; Effarizah, M.E.; Syahariza, Z.A.; Shamila-Syuhada, A.K.; Rusul, G. Mislabelling of beef and poultry products sold in Malaysia. Food Control. 2016, 62, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tembe, D.; Mukaratirwa, S.; Zishiri, O. Undeclared Meat Species in Processed Meat Products from Retail Franchises in the Durban Metropole, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, Using Species-specific DNA Primers. Food Protection Trends. 2018, Vol 38, No. 6, p. 440–449.

- Keyvan, E.; Çil, G.I.; Kul, B.Ç.; Bilgen, N.; Şireli, U.Ş. Identification of meat species in different types of meat products by PCR. Ankara Üniv Vet Fak Derg. 2017, 64, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan, S.; Viljoen, C.D. Determining the presence of undeclared animal species using Real-time PCR in canned and ready-to-eat meat products in South Africa. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2020, 58(2):1-6.

- Beltramo, C.; Riina, M.V.; Colussi, S.; Campia, V.; Maniaci, M.G.; Biolatti, C.; Trisorio, S.; Modesto, P.; Peletto, S.; Acutis, P.L. Validation of a DNA biochip for species identification in food forensic science. Food Control. 2017, 78, 366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Golian, J.; Drdolová, Z.; Benešová, L. (2022). Molecular diagnostic test systems for meat identification: A comparison study of the MEAT 5.0 LCD-Array and innuDETECT Assay detection methods. ACTA VET. BRNO 2020, 89: 89–96.

- Simsek, Y.O.; Isıklı, M. Fatty acid composition and quality characteristics of low-fat cooked sausages made with beef and chicken meat, tomato juice, and sunflower oil. Meat Science. 2002, 62 253–258.

- Pereira, N.R.; Tarley, C.R.; Matsushita, M.; de Souza, N.E. Proximate Composition and Fatty Acid Profile in Brazilian Poultry Sausages. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 915–920. [Google Scholar]

- Valsta, L.; Tapanainen, H.; Männistö, S. Meat fats in nutrition. Meat Sci. 2005, 70, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guntarti, A.; Ahda, M.; Kusbandari, A. Determining fatty acids and halal authentication of sausage. Food Res. 2019, 4, 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Barrera, J.E.; Gonzalez-Alcorta, M.J.; Castillo-Dominguez, R.M.; Prado-Rebolledo, O.F.; Hernandez-Velasco, X.; Anita Menconi, A.; Tellez, G.; Hargis, B.M.; Carrillo-Dominguez, S. Fatty Acid Deposition on Broiler Meat in Chickens Supplemented with Tuna Oil. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcarrondo, C.A.; F. Padilla, F.C.; Martín, E. Fatty acid composition of beef, pork, and poultry fresh cuts, and some of their processed products. Agricultural and Food Sciences. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 1998, 48(4):354-8.

| S/SL inlet | 250 °C, split ration 50:1 |

| Liner | Split, ultra inert, glass wool, low-pressure drops (p/n 5190-295) |

| Oven ramp program | 50 °C (0.5 min) |

| 30 °C/min to 194 °C (3.5 min) | |

| 5 °C/min to 240 °C (3 min) | |

| Carrier gas | Nitrogen, 13 psi, constant pressure mode |

| Column | DB-Fast FAME 30 m × 0.250 mm × 0.25 um 40 °C to 250/260 °C |

| Detector-fid | 260 °C, |

| H2: 40 mL/min | |

| Air: 400 mL/min | |

| Makeup gas: 25 mL/min | |

| Injection volume | 1 uL |

| Chicken meat (%) | Beef Sausage (%) | C14:0Myristolein | C14:1Myristin | C15:0Pentadecane | C16:0 Palmitin | C16:1 Palmitolin | C17:0Heptadecan | C18:0Stearic | C18:1Oleic | C18:2Linol | C183Linolen alfa | C20:0Arachin | Saturated acids | Mono-saturated acids | Poly-saturated acids | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 18.28 | 3.44 | 0.13 | 6.57 | 29.18 | 37.59 | 4.28 | 0.05 | 25.17 | 32.95 | 41.87 | 99.99 |

| 0 | 100 | 3.58 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 29.05 | 2.98 | 1.88 | 24.84 | 33.34 | 2.76 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 60.04 | 36.76 | 3.11 | 99.91 |

| 99 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 19.4 | 3.37 | 0.17 | 8.31 | 29.37 | 35.33 | 3.29 | 0.06 | 28.48 | 32.9 | 38.62 | 100 |

| 90 | 10 | 0.66 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 20.2 | 3.32 | 0.29 | 9.84 | 16.5 | 32.18 | 3.14 | 0.07 | 31.17 | 19.99 | 35.32 | 86.48 |

| 80 | 20 | 1.23 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 22.23 | 3.02 | 0.58 | 14.18 | 31.26 | 24.64 | 2.29 | 0.08 | 38.49 | 34.55 | 26.93 | 99.97 |

| 70 | 30 | 1.57 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 23.91 | 2.96 | 0.85 | 15.46 | 31.85 | 20.72 | 2.04 | 0.04 | 42.09 | 35.13 | 22.76 | 99.98 |

| 60 | 40 | 2.05 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 25.3 | 3.03 | 0.95 | 17.5 | 32.12 | 16.66 | 1.59 | 0 | 46.11 | 35.58 | 18.25 | 99.94 |

| 50 | 50 | 2.12 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 25.73 | 2.93 | 1.09 | 19.39 | 32.46 | 14.03 | 1.33 | 0.1 | 48.75 | 35.81 | 15.36 | 99.92 |

| 40 | 60 | 2.28 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 26.43 | 3.06 | 1.11 | 18.37 | 32.76 | 13.84 | 1.37 | 0 | 48.53 | 36.25 | 15.21 | 99.99 |

| 30 | 70 | 2.84 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 28.35 | 2.85 | 1.41 | 21.65 | 33.24 | 7.77 | 0 | 0.07 | 54.76 | 36.64 | 7.77 | 99.17 |

| 20 | 80 | 2.77 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 28.85 | 2.79 | 1.6 | 22.78 | 34.25 | 5.5 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 56.51 | 37.41 | 6.06 | 99.98 |

| 10 | 90 | 3.22 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 28.64 | 2.81 | 1.58 | 24.24 | 34.27 | 3.53 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 58.29 | 37.69 | 3.9 | 99.88 |

| 7 | 93 | 3.04 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 29.55 | 2.68 | 1.59 | 23.85 | 34.9 | 3.11 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 58.6 | 37.85 | 3.43 | 99.88 |

| 2 | 98 | 3.57 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 31.06 | 2.9 | 1.87 | 23.7 | 33.15 | 2.05 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 60.87 | 36.71 | 2.32 | 99.9 |

| Fatty acids | Beef Sausage | Beef Sausage with Poultry DNA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myroistelin | 3.17 | 2.56 | 0.000893* |

| Myristin | 0.39 | 0.3 | 0.156974 |

| Pentadecane | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.000555* |

| Palmitin | 25.66 | 24.14 | 0.000238 |

| Palmitolin | 3.17 | 3.55 | 0.066677 |

| Heptadecan | 1.34 | 1.09 | 0.003113* |

| Stearic | 22.76 | 18.11 | 0.000305* |

| Oleic | 39.18 | 39 | 0.828574 |

| Linol | 2.72 | 9.46 | 3.28E-06* |

| Linolen alfa | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.15E-05* |

| Arachin | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.250436 |

| Saturated | 52.5 | 43.48 | 0.002973* |

| Monosaturated | 41.52 | 39.46 | 0.425882 |

| Polyunsaturated | 3.03 | 10.04 | 7.64E-06* |

| Added meat poultry % | Samples (No) | C14:0Myristolein | C14:1Myristin | C15:0Pentadecane | C16:0 Palmitin | C16:1 Palmitolin | C17:0Heptadecan | C18:0Stearic | C18:1Oleic | C18:2Linol | C183Linolen alfa | C20:0Arachin | Saturated acids | Mono-saturated acids | Poly-saturated acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.95 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 23.77 | 1.94 | 1.24 | 28.63 | 36.73 | 3.29 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 57.49 | 38.88 | 3.63 | |

| 2 | 2.91 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 24.97 | 3.32 | 1.08 | 24 | 38.3 | 3.1 | 0.39 | 0.67 54.10 | 42.43 3.49 | |||

| 3 | 3.35 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 26.56 | 2.37 | 1.52 | 28.25 | 31.75 | 3.94 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 60.92 | 34.53 | 4.55 | |

| 10% | 4 | 3.08 | 0.24 | 0.59 | 26.14 | 3.3 | 1.26 | 21.65 | 39.29 | 3.47 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 53.23 | 42.83 | 3.95 |

| 5 | 3.96 | 0.23 | 0.7 | 27.68 | 3.46 | 1.41 | 21.21 | 37.42 | 3.13 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 55.39 | 41.11 | 3.48 | |

| 6 | 3.17 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 24.4 | 2.69 | 1.38 | 22.62 | 40 | 3.6 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 52.82 | 43.01 | 4.17 | |

| 7 | 3.02 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 24.19 | 2.95 | 1.24 | 22.65 | 40.01 | 3.73 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 52.32 | 43.24 | 4.44 | |

| 8 | 2.72 | 0.24 | 0.5 | 24.27 | 3.67 | 1.26 | 17.58 | 44.99 | 3.74 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 46.96 | 48.9 | 4.13 | |

| AV | 3.08 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 25.24 | 2.9 | 1.29 | 23.32 | 38.56 | 3.5 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 54.15 | 41.86 | 3.98 | |

| 1 | 3.24 | 1.19 | 0.56 | 24.32 | 5.05 | 1.24 | 15.33 | 43.73 | 3.61 | 0.5 | 1.23 | 45.92 | 49.97 | 4.11 | |

| 2 | 3.06 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 26.26 | 3.94 | 1.15 | 19.73 | 40.03 | 3.68 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 51.23 | 44.61 | 4.15 | |

| 3 | 2.72 | 0.4 | 0.43 | 27.06 | 2.7 | 1.39 | 24.25 | 37.76 | 2.6 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 56.18 | 40.86 | 2.97 | |

| 4 | 2.92 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 25.4 | 2.56 | 1.65 | 24.34 | 37.97 | 3.22 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 55.34 | 41 | 3.67 | |

| 20% | 5 | 3.04 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 25.5 | 3.73 | 1.28 | 19.81 | 38.59 | 5.78 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 50.87 | 42.67 | 6.46 |

| 6 | 2.88 | 0.22 | 0.6 | 23.99 | 2.97 | 1.31 | 23.72 | 38.12 | 4.79 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 53.36 | 41.31 | 5.34 | |

| 7 | 3.39 | 0.2 | 0.57 | 26.01 | 2.43 | 1.36 | 24.52 | 35.7 | 4.88 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 56.36 | 38.33 | 5.31 | |

| 8 | 4.09 | 0 | 0.48 | 24.07 | 4.22 | 1.29 | 15.29 | 43.4 | 5.9 | 0.53 | 0.7 | 45.92 | 47.62 | 6.43 | |

| 9 | 3.19 | 0.26 | 0.5 | 23.24 | 3.13 | 1.22 | 21.14 | 41.37 | 4.12 | 0.41 | 1.43 | 50.72 | 44.76 | 4.53 | |

| 10 | 3.02 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 25.52 | 3.87 | 1.56 | 17.13 | 43.62 | 3.82 | 0.4 | 0.45 | 48.18 | 47.61 | 4.22 | |

| AV | 3.15 | 0.38 | 0.524 | 25.13 | 3.46 | 1.34 | 20.52 | 40.02 | 4.24 | 0.479 | 0.72 | 51.4 | 43.87 | 4.71 | |

| 1 | 3.34 | 1.03 | 0.53 | 25.53 | 4.69 | 1.02 | 13.27 | 41.18 | 7.66 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 44.46 | 46.9 | 8.61 | |

| 2 | 2.62 | 0.28 | 0.5 | 23.9 | 3.92 | 1.16 | 16.35 | 40.84 | 8.61 | 1.1 | 0.71 | 45.24 | 45.04 | 9.71 | |

| 30% | 3 | 2.36 | 0.2 | 0.46 | 24.43 | 2.72 | 1.24 | 22.7 | 34.81 | 9.67 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 51.62 | 37.33 | 10.65 |

| 4 | 2.77 | 0.37 | 0.59 | 25.19 | 2.66 | 1.61 | 23.03 | 35.65 | 7.07 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 53.74 | 38.68 | 7.59 | |

| 5 | 2.57 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 22.38 | 3.71 | 1.34 | 14.77 | 44.24 | 8.68 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 42.26 | 48.17 | 9.57 | |

| AV | 2.73 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 24.28 | 3.54 | 1.27 | 18.02 | 39.34 | 8.33 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 47.46 | 43.22 | 9.22 | |

| 50% | 1 | 2.42 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 22.57 | 3.43 | 0.71 | 15.16 | 37.87 | 15.86 | 1.35 | 0.26 | 41.33 | 41.46 | 17.21 |

| 1 | 1.52 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 21.03 | 3.78 | 0.63 | 11.4 | 40.83 | 17.99 | 1.58 | 0.51 | 35.35 | 45.08 | 19.57 | |

| 60% | 2 | 1.51 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 23.09 | 4.13 | 0.57 | 14.84 | 38.85 | 15.28 | 1.2 | 0.18 | 40.42 | 43.09 | 16.48 |

| AV | 1.51 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 22.06 | 3.99 | 0.6 | 13.1 | 39.84 | 16.63 | 1.39 | 0.34 | 37.88 | 44.08 | 18.02 | |

| 1 | 1.37 | 0 | 0 | 23.32 | 4.13 | 1.41 | 10.16 | 38.52 | 19.74 | 1.35 | 0 | 36.26 | 42.65 | 21.09 | |

| 70% | 2 | 1.68 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 23.2 | 3.26 | 0.81 | 13.43 | 36.62 | 19.07 | 1.18 | 0.3 | 39.73 | 40.02 | 20.25 |

| AV | 1.52 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 23.26 | 3.69 | 1.11 | 11.79 | 37.57 | 19.4 | 1.265 | 0.3 | 37.99 | 41.33 | 20.62 | |

| 1 | 1.16 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 20.93 | 4.24 | 0.42 | 13.35 | 36.64 | 21.81 | 0.99 | 0.14 | 36.18 | 41.03 | 22.8 | |

| 80% | 2 | 1.93 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 22.39 | 4.77 | 0.4 | 11.16 | 36.95 | 20.51 | 1.57 | 0.11 | 36.16 | 41.76 | 22.08 |

| AV | 1.54 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 21.66 | 4.5 | 0.41 | 12.25 | 36.79 | 21.16 | 1.29 | 0.12 | 36.1 | 41.39 | 22.44 | |

| 1 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 22.04 | 4.53 | 0.26 | 7.77 | 37.12 | 24.49 | 1.6 | 0.16 | 31.11 | 41.8 | 26.09 | |

| 90% | 2 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 20.46 | 4.61 | 0.16 | 7.25 | 39.01 | 26.45 | 1.02 | 0.1 | 28.57 | 4.63 | 27.47 |

| 3 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 21.54 | 5.22 | 0.13 | 6.57 | 39.26 | 24.19 | 2.19 | 0.12 | 28.98 | 44.64 | 26.38 | |

| AV | 0.57 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 21.54 | 4.78 | 0.18 | 7.19 | 38.46 | 25.04 | 1.6 | 0.12 | 29.55 | 30.36 | 26.64 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).