1. Introduction

The problem of optimizing Water Distribution Network Design (WDND) has been extensively studied by researchers worldwide. This challenging task involves a variety of optimization techniques, frameworks, and constraints. The goal is to ensure that water distribution systems operate efficiently while minimizing costs, all within the limits of hydraulic and operational constraints.

One of the earliest notable contributions to this field was by Alperovits and Shamir in 1977. They tackled both the component sizing and operational decisions in water distribution networks using a linear objective function. Their approach was based on the Linear Programming Gradient (LPG) method, which divides the optimization process into two levels: first, an equation for the optimal cost of the network is derived based on a feasible water flow; second, the water flow is adjusted to minimize costs.

Building on this foundation, several other models emerged. Quindry et al. (1981) extended the linear programming method by including path interaction terms that had been previously neglected. Kessler and Shamir (1989) also improved the LPG method, and Fujiwara and Khang (1990) expanded it further to handle nonlinear models through a two-phase decomposition technique.

Complete Enumeration (CEn) was another method applied to WDN optimization. This approach, demonstrated by Simpson et al. (1994), evaluates all possible solutions to guarantee a global optimum, but it is computationally expensive, especially for large networks. To address this issue, Gessler (1985) and Loubser and Gessler (1990) introduced Selective Enumeration (SEn), which limits the search space to speed up the process. Loubser and Gessler (1990) proposed three guidelines for pruning: grouping pipes, storing the lowest-cost feasible solution, and eliminating combinations that violate constraints.

In the 1990s, metaheuristic algorithms became increasingly popular for solving WDND problems. These heuristic methods do not guarantee a global optimum but are highly flexible and can provide near-optimal solutions for complex problems. Metaheuristics can be categorized into three main types: local search, population-based, and constructive approaches.

Simulated Annealing (SA), a local search technique inspired by the physical annealing of crystals, was successfully applied to WDND by Loganathan et al. (1995) and others. Tabu Search (TS), another local search method introduced by Glover (1986), was used by Cunha and Ribeiro (2004) in water network optimization.

Population-based algorithms, such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), gained traction after Holland (1975) pioneered their use. Murphy and Simpson (1992) were the first to apply GAs to WDND. Later improvements by Dandy et al. (1996) and Savic and Walters (1997) included techniques like Gray coding to avoid issues like the Hamming cliff effect, and Gupta et al. (1999) used real coding for greater accuracy.

Other population-based approaches, such as Differential Evolution (DE) (Storn and Price, 1997), Memetic Algorithms (MAs) (Baños et al., 2007), and the Cross-Entropy Method (CE) (Perelman and Ostfeld, 2007), further advanced WDND optimization.

Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), inspired by ant behavior and introduced by Dorigo et al. (1996), was applied to WDND by Maier et al. (2003) and others, while Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), was used by Montalvo et al. (2008). These methods were praised for their efficiency and adaptability to large, complex networks.

Recent research has extended the focus from single-objective optimization, typically minimizing costs, to multi-objective approaches. For example, Keedwell and Khu (2006) introduced methods to balance cost minimization with pressure constraint violations, while Montalvo et al. (2010) added reliability as a third objective, considering the costs of system failures and repairs.

Harmony Search (HS), developed by Geem et al. (2006), is another metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the improvisation of musicians. It generates new solutions based on a memory of existing ones, and has been successfully applied to water distribution network design. Geem et al. (2011) even combined HS with PSO to create a hybrid method, Particle Swarm Harmony Search (PSHS) (Moosivan et al. 2019; Sirsant et al. 2022).

In this study, the Harmony Search (HS) algorithm was selected for its robustness, efficiency, and versatility (De Paola et al., 2016, 2017). HS was fully integrated within the AutoCAD Civil 3D (C3D) environment, improving its application in hydraulic infrastructure design. By using Dynamo, the system automatically generates an .inp file that is compatible with EPANET 2.2, a widely used tool for simulating water distribution networks. This file can then be processed by the HS routine to optimize the network design, ensuring compliance with constraints like minimum allowable pressure and cost-effectiveness.

This integration of C3D, Dynamo, and EPANET accelerates and improves the accuracy of water distribution network design, providing engineers with efficient, reliable, and optimized solutions.

2. Results and Discussion

Digital models of water distribution networks play a crucial role in both the optimal design and management of infrastructure systems. By leveraging Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology, it becomes possible to develop new flow charts that enhance the design of hydraulic infrastructures. BIM's ability to facilitate interoperability between various tools and workflows is leading to more effective solutions tailored to specific case studies. Among the available tools, AutoCAD Civil 3D (C3D) stands out as a powerful BIM integration platform. It offers highly flexible solutions that allow for better integration and management of the infrastructure being designed or analyzed.

Historically, repeating operations in AutoCAD has been straightforward using scripts or macros, and new functions can be created with Lisp language. However, both methods have limitations, primarily due to their static nature. AutoCAD scripts often struggle with Civil 3D data, and Lisp requires users to learn a programming language to develop new functionalities. Dynamo effectively addresses these challenges by enabling dynamic, repeatable operations between AutoCAD and Civil 3D. Dynamo offers a user-friendly visual programming environment, allowing Civil 3D users to create and manage workflows without needing to write code. While users must think like programmers in terms of logic, the actual coding aspect is not necessary. As an open-source graphical programming interface, Dynamo facilitates Building Information Modeling (BIM) by providing a data and logic framework through a graphical algorithm editor. With Dynamo, users can construct custom workflows for data creation, positioning, and visualization, enhancing their ability to iterate quickly and produce superior designs in less time. This flexibility allows for more efficient design processes and fosters innovation, making it an invaluable tool for professionals working with AutoCAD and Civil 3D.

In this context, the authors introduce a new tool, DyEHS, which integrates seamlessly within the C3D environment. DyEHS combines the capabilities of Dynamo, EPANET 2.2, and the Harmony Search algorithm to optimize the design of water distribution networks. This tool not only allows for the design optimization but also provides the ability to return the results in a fully integrated 3D BIM model within C3D. A key feature of this model is the automatic recognition of fittings and appurtenances, significantly simplifying the design process.

Furthermore, DyEHS allows for efficient management of both the horizontal and vertical layouts of the water distribution system. The horizontal layout pertains to the geographical arrangement of the pipes and components, while the vertical layout, or profiles, represents the system's elevation changes. The ability to handle these layouts with ease contributes to more precise and efficient water distribution network designs, reducing the margin for error and improving overall project outcomes.

This integration of DyEHS with C3D and the application of tools like Dynamo and EPANET 2.2 provides an advanced platform for engineers to optimize water distribution network designs. The inclusion of the Harmony Search algorithm further enhances this process by identifying optimal solutions for complex hydraulic problems. As a result, engineers can achieve designs that are both cost-effective and efficient in terms of water distribution performance (

Figure 1).

In summary, the adoption of BIM technologies, particularly through tools like AutoCAD Civil 3D, has revolutionized the way water distribution networks are designed and managed. With the development of new tools like DyEHS, engineers can now take advantage of seamless integration between different software platforms to create more efficient, accurate, and adaptable water distribution models. This not only enhances the design process but also streamlines management tasks, allowing for better control over both horizontal and vertical infrastructure layouts. Ultimately, this leads to improved outcomes for water distribution projects, ensuring they are optimized for both performance and cost-efficiency.

To show the capability of the tool in the water distribution network design optimization a real case study is showed. This case study is based on an Italian Municipality called Bagnoli Irpino situated in the south of Italy and is based on the design of a new two loops network that must provide a flow rate of approximately 10 l/s.

Figure 2 depict an aerial image of the WDN under consideration with the position of reservoir (yellow polygon) with head equal to 735 masl. Once the 3d polyline has been drawn, by means of a Dynamo script is possible to retrieve two files nodes.txt and pipes.txt.

Figure 2.

Two Loops WDN of Bagnoli Irpino, Campania Region (South of Italy).

Figure 2.

Two Loops WDN of Bagnoli Irpino, Campania Region (South of Italy).

Figure 3.

polyinfo.dyn script implemented in Dynamo Environment.

Figure 3.

polyinfo.dyn script implemented in Dynamo Environment.

Therefore, from txt files with the aim of a LISP tool, implemented in visual basic environment) is possible to get an .inp file (WRITE_INP) and open the file pipe.inp directly from C3D environment in Epanet 2.2 (

Figure 4).

With the Epanet

.inp file it is possible to launch from C3D environment directly the HS Network Optimizer and get the optimum solution constrained to a minimum pressure to all over the network of 25 m (

Figure 5). To run the optimizer, it is necessary to prepare three files (*.inp, *.dat, and *. para):

*.inp is normal EPANET input file.

*.dat is pipe cost data file which consists of number of data, unit of pipe diameter (inch or millimeter), and combination of diameter & corresponding cost.

*. para is parameter value file for Harmony Search algorithm.

Suggested parameter can be fixed as:

HMS: Size of Harmony Memory. It is normally 30 (20 for < 10 node numbers, 50 for > 100 node numbers).

HMCR: Rate of Harmony Memory Consideration. It is normally 0.95 (0.9 for < 10 node numbers, 0.97 ~ 0.99 for > 100 node numbers).

PAR: Rate of pitch adjustment. It is normally 0.05.

Flag_Skip & ECR: Parameters for ensemble consideration (generally assumed respectively 1.0 and 0.0).

App_Cost: Approximate design cost found by normal design.

MaxIter: Maximum number of Iterations (= Hydraulic Analyses).

MinHead: Minimum allowable head at each node.

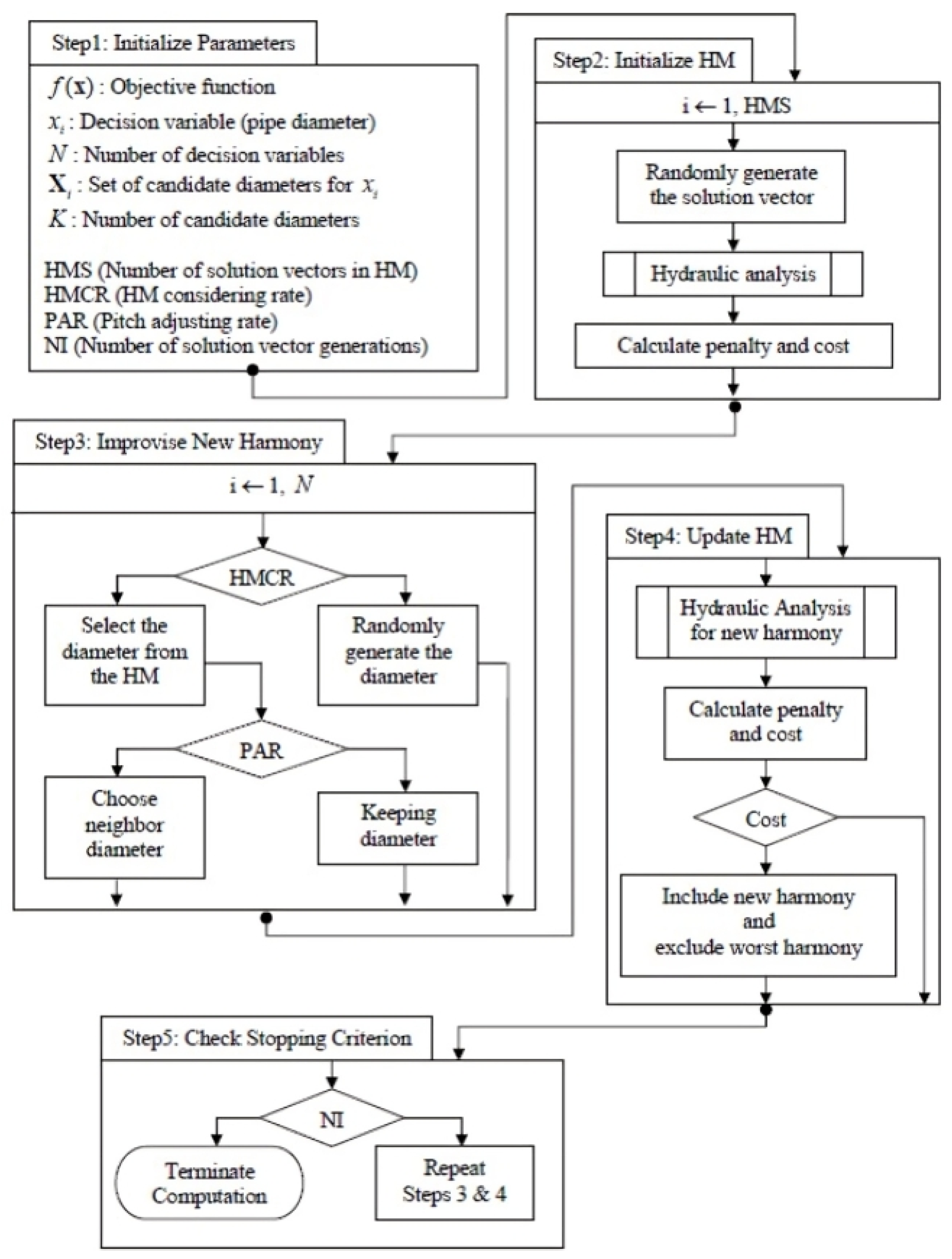

In greater detail the optimization procedure is showed Flow chart of

Figure 6.

The step-by-step outline (

Figure 6) of Harmony Search used for this specific problem is composed by the following steps.

- 1.

Define the Decision Variables: In WDN design, the decision variables are the diameters of the pipes in the network. These diameters are typically selected from a discrete set of commercially available sizes. Each pipe section in the network is a decision variable, and the length of the decision vector equals the number of pipe sections in the network.

- 2.

-

Formulate the Objective Function: The objective is to minimize the total cost of the WDN, which consists of two main components:

Capital cost: A function of the pipe diameters and lengths.

Operational cost: Primarily related to the energy required for pumping, which depends on the head loss in the pipes, flow rates, and the network layout.

Mathematically, this can be represented as:

where C is the total cost, c

i is the unit cost of the

i-th pipe based on its diameter, L

i is the length of the

i-th pipe and Energy

j is the pumping cost at the

j-th pump (N total number of pipes and M total number of pumps).

- 3.

-

Impose Hydraulic Constraints: The design must satisfy hydraulic constraints, such as:

Continuity of flow: The sum of flows into and out of each node must balance.

Pressure constraints: The pressure at each demand node must be within specified limits to ensure adequate service.

Head loss: Governed by empirical laws like the Hazen-Williams equation or Darcy-Weisbach equation, head loss is a function of pipe length, diameter, and flow rate.

- 4.

Initialize Harmony Memory: An initial set of solutions (pipe diameters) is randomly generated, ensuring that all hydraulic constraints are satisfied. This initial population serves as the Harmony Memory, with each solution representing a possible network design.

- 5.

Improvise New Harmony: A new set of pipe diameters is generated by considering existing solutions in the Harmony Memory, applying the Harmony Memory Considering Rate (HMCR), Pitch Adjustment Rate (PAR), or through random selection. The new design is then evaluated based on the objective function (cost) and checked for constraint satisfaction.

- 6.

Update Harmony Memory: If the new design is better than the worst solution in the Harmony Memory, it replaces the worst solution. This ensures that the memory is continuously improved with better designs.

- 7.

Convergence: The process is repeated until a stopping criterion is met. Typically, this could be a fixed number of iterations or until there is no significant improvement in the solution over successive iterations.

Since the procedure is coupled to Epanet 2.2 all the hydraulic constraints where verified by Epanet itself.

Once the procedure is completed in the C3D (Civil 3D) environment, it is possible to create an optimized BIM (Building Information Modeling) model of the water distribution network. This process integrates the design with all relevant cartographic data necessary for the finalization of the network’s layout (such as sections, profiles and excavation trench with all related costs).

The optimized BIM model serves as a detailed digital representation of the water distribution system, including the pipes, valves, pumps, and other essential components. By utilizing Civil 3D, designers can leverage its powerful features for 3D modeling, which enables the accurate placement and alignment of network elements according to terrain and spatial constraints. This allows for the refinement of the network design to meet hydraulic performance requirements and ensure that the system operates efficiently.

Additionally, Civil 3D supports the generation of comprehensive cartographic outputs, such as plan views, profiles, and cross-sections. These maps can be integrated with GIS data to provide precise geographical context and ensure the network’s design is aligned with real-world conditions. The combination of BIM and cartographic data streamlines collaboration between engineers, architects, and contractors, facilitating better decision-making and reducing errors during construction.

Therefore, once the network design process is completed in the C3D environment, it becomes straightforward to generate an optimized BIM model along with all necessary cartographic documentation. This combination ensures a highly accurate and efficient design, ready for implementation, while providing clear visualizations and data to guide the construction and management of the water distribution network (

Figure 7).

3. Conclusion

Digital models of water distribution networks are crucial for optimizing the design and management of infrastructure systems. Leveraging Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology enables the development of efficient flow charts for hydraulic infrastructure design. The interoperability of BIM tools facilitates the integration of diverse workflows, allowing for customized solutions tailored to specific case studies. AutoCAD Civil 3D (C3D), one of the most versatile BIM platforms, offers robust solutions for integrating and managing infrastructure projects.

This paper introduces DyEHS, an innovative tool that integrates seamlessly into the C3D environment. DyEHS combines the power of Dynamo, EPANET 2.2, and the Harmony Search (HS) algorithm to optimize water distribution network design. The tool generates a comprehensive 3D BIM model, automatically recognizing fittings and appurtenances within the C3D environment. DyEHS also simplifies the management of both horizontal layouts and vertical profiles, making it a highly efficient and adaptable solution for water distribution projects. This integration streamlines the design process, providing improved precision and management capabilities for hydraulic infrastructure.

This study presents, therefore, a novel BIM-integrated optimization tool for water distribution networks. By combining Civil 3D, Dynamo, EPANET 2.2, and Harmony Search, DyEHS significantly improves design efficiency, computational performance, and cost-effectiveness. Future research will focus on real-time monitoring and AI-driven optimizations to further enhance performance.

Author Contributions

F. De Paola: Conceptualization; F. De Paola: Methodology; G. Ascione & G. Speranza: Writing - Review & Editing; F. De Paola: Software; N. Marrone: Validation.

References

- Alperovits, A., Shamir, U., 1997. Design of optimal water distribution systems. Water Resources Research 13 (6), 885–900. [CrossRef]

- Baños, R., Gil, C., Agulleiro, J., Reca, J., 2007. A memetic algorithm for water distribution network design. Soft Computing in Industrial Applications, 279– 289.

- Cunha, M., Ribeiro, L., 2004. Tabu search algorithms for water network optimization. European Journal of Operational Research 157 (3), 746–758. [CrossRef]

- Dandy, G.C., Simpson, A.R., Murphy, L.J., 1996. An improved genetic algorithm for pipe network optimisation. Water Resources Research 32 (2), 449–458. [CrossRef]

- De Paola, F., Giugni, M., Pugliese, F., 2016. A harmony-based calibration tool for urban drainage systems. Proc Inst Civ Eng Water Manage 171(1):30–41. [CrossRef]

- De Paola, F., Galdiero, E., Giugni, M. 2017. Location and setting of valves in water distribution networks using a harmony search approach. J Water Resour Plan Manag 143(6):04017015. [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M., Maniezzo, V., Colorni, A., 1996. Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics 26, 29–41. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, O., Khang, D.B., 1990. A two-phase decomposition method for optimal design of looped water distribution networks. Water Resources Research 26 (4), 539–549. [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W., 2006. Optimal cost design of water distribution networks using harmony search. Engineering Optimization 38 (3), 259–280. [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W., Kim, J.H., et al., 2011. A new heuristic optimization algorithm: harmony search. Simulation 76 (2), 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Gessler, J., 1985. Pipe network optimization by enumeration. Computer Applications in Water Resources, 572–581.

- Glover, F., 1989. Tabu search – Part I. ORSA Journal on Computing 1, 190–206. Goldberg, D.E., 1989.

- Gupta, I., Gupta, A., Khanna, P., 1999. Genetic algorithm for optimization of water distribution systems. Environmental Modelling & Software 14 (5), 437–446. [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H., 1975. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems. Michigan Press.

- Keedwell, E., Khu, S.-T., 2006. A novel evolutionary metaheuristic for the multi-objective optimization of real-world water distribution networks. Engineering Optimization 38 (3), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A., Shamir, U., 1989. Analysis of the linear programming gradient method for optimal design of water supply networks. Water Resources Research 25 (7), 1469–1480. [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, G.V., Greene, J.J., Ahn, T.J., 1995. Design heuristic for globally minimum cost water distribution systems. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 121 (2), 182–192.

- Loubser, B.F., Gessler, J., 1990. Computer-aided optimization of water distribution networks. The Civil Engineer of South Africa 32, 413–422.

- Maier, H.R., Simpson, A.R., Zecchin, A.C., Foong, W.K., Phang, K.Y., Seah, H.Y., Tan, C.L., 2003. Ant colony optimization for design of water distribution systems. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 129 (3), 200–209. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, I., Izquierdo, J., Pérez, R., Tung, M.M., 2008. Particle swarm optimization applied to the design of water supply systems. Computer & Mathematics with Applications 56, 769–776. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, I., Izquierdo, J., Schwarze, S., Pérez-Garcı´a, R., 2010. Multi-objective particle swarm optimization applied to water distribution systems design: an approach with human interaction. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 52, 1219–1227.

- Moosavian, N.; Lence, B.J. 2019. Fittest Individual Referenced Differential Evolution Algorithms for Optimization of Water Distribution Networks. J. Comput. Civ. Eng., 33. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.J., Simpson, A.R., 1992. Genetic Algorithms in Pipe Network Optimisation. Research Report R93, University of Adelaide.

- Perelman, L., Ostfeld, A., 2007. An adaptive heuristic cross-entropy algorithm for optimal design of water distribution systems. Engineering Optimization 39 (4), 413–428. [CrossRef]

- Quindry, G.E., Liebman, J.C., Brill, E.D., 1981. Optimization of looped water distribution systems. Journal of the Environmental Engineering Division 107 (4), 665–679.

- Reca, J., Martı´nez, J., 2006. Genetic Algorithms for the Design of Looped Irrigation Water Distribution Networks. Water Resources Research 42.

- Savic, D., Walters, G., 1997. Genetic algorithms for least-cost design of water distribution networks. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 123 (2), 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.R., Dandy, G.C., Murphy, L.J., 1994. Genetic algorithms compared to other techniques for pipe optimization. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 120 (4), 423–443. [CrossRef]

- Sirsant, S.; Reddy, M.J. 2022. Improved MOSADE Algorithm Incorporating Sobol Sequences for Multi-Objective Design of Water Distribution Networks. Appl. Soft Comput., 120, 108682. [CrossRef]

- Storn, R., Price, K., 1997. Differential evolution – a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of Global Optimization 11, 341–359. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).