1.Introduction

This paper addresses the discrepancy between the observed orbital velocities of stars in galaxies and those predicted by Newtonian mechanics. The flat rotation curves observed at large galactic radii imply the existence of missing mass, typically attributed to dark matter or solved by modifications to gravitational theory [

1,

2,

3]. While the dark matter hypothesis remains incomplete, with multiple proposed particle candidates, it continues to serve as the primary framework for explaining the anomalies in galactic rotation curves [

4].

Given that direct detection of dark matter particles has not yet been achieved, despite extensive experimental efforts [

5], it has become necessary to explore alternative theoretical frameworks. This paper posits that our current understanding of general relativistic gravity may be incomplete and suggests that the observed data could be interpreted through different physical mechanisms.

The prevailing interpretation of gravity is that it arises from the curvature of spacetime [

6]. In this framework, the presence of massive objects distorts the geometry of spacetime, and this curvature is perceived as gravitational attraction [

7,

8]. The approach proposed in this paper lays in and alternative interpretation of general relativistic gravity, conceptualizing it as a spatial flow [

9]. In this framework, space flows inward toward massive objects, thereby entraining the surrounding matter [

10,

11]. This concept provides solutions, such as the Painlevé-Gullstrand (PG) coordinates, to describe the structure of black holes, which eliminate the coordinate singularity at the event horizon present in Schwarzschild coordinates [

12,

13]. A theoretical framework will be discussed in future works; this paper focuses on assessing the feasibility of applying this approach to interpret the discrepancy in orbital velocities.

The special flow interpretation introduces an additional effect. When observing a distant galaxy from Earth, assuming space is flowing toward the center of the observed galaxy, this assumption leads to a distortion where the galaxy appears compressed. This implies that the actual spatial extent of the galaxy is larger than our perception suggests. This effect, which we will refer to as “Mezzi,” has a significant consequence: the observed rotational velocities of stars within a distant galaxy may be underestimated, as the stars actually traverse larger distances than our measurements suggest. Additionally, this effect reduces the apparent angular sizes of objects, leading to an underestimation of their true luminosities, and consequently, their inferred masses.

The SPARC dataset (Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves) provides rotation curves for 175 nearby galaxies, compiled from several relatively homogeneous studies. These curves were analyzed for large-scale features that correlate with the galaxies’ surface brightness profiles. The analysis included procedures to remove contaminants like foreground stars and background galaxies, as well as to minimize errors, such as those caused by beam-smearing effects [

14].

This study employ inverse problem analyzes of the rotation curves using an iterative search algorithm to minimize the discrepancy between Newtonian predictions, based solely on baryonic mass, and the observed velocities. The Mezzi effect is calculated though scaling the Newtonian rotation curves by two parameters: a constant mass coefficient and a radially dependent Mezzi scale factor. This approach will allow us to test the validity of the “Mezzi” effect as an explanation for the observed discrepancies in rotational velocities.

2. Mezzi effect

The Painlevé–Gullstrand coordinates reformulate the Schwarzschild geometry as a flowing spatial metric [

15,

16]. In these coordinates, the Schwarzschild spacetime takes the form:

represents the proper time measured by observers free-falling from infinity. In this analogy, the velocity of space in the Painlevé–Gullstrand coordinates is given by:

is the local infall velocity of space itself, drawing objects toward the massive object. It is equivalent to the Newtonian escape velocity, and it describes a velocity field that is consistent with the gravitational potential energy [

10]. For a static observer, the proper time

is dilated relative to the coordinate time

analogously to relative motion in special relativity. In the case of an observer moving with velocity v, the relation is given by:

In contrast, for an observer in free fall, gravitational time dilation can be understood by expressing this effect in terms of the observer’s instantaneous velocity relative to a stationary, asymptotic frame. This velocity-based interpretation is fully consistent with the predictions of general relativity. The PG coordinates are used in current research for visualizing stationary black hole physics [

17,

18].

In addition to time dilation, the existing space flow models reproduce key relativistic phenomena, such as gravitational lensing, gravitational redshift, and orbital precession [

13,

19,

20]. In this paper, we treat space flow as a physical phenomenon, where the flowing nature of space itself define the gravitational effects. Building on this assumption, we introduce the concept of the Mezzi effect.

The Mezzi effect is a result of the space flow framework applied to distant galaxies. In this framework, space flows toward a galaxy’s center, making its structure appear compressed to a distant observer. As a result, the distances within the galaxy appear shorter than they actually are.

The apparent compression of the galaxy causes the observed orbital radius of a star to appear smaller than its actual orbital radius. Since rotational velocities are calculated based on this reduced radius, the inferred velocities are lower than the true velocities

The compression effect also results in an underestimation of luminosity. The underestimation of distances, along with reduced angular sizes, leads to an underestimation of the induced masses.

The distortion in perceived spatial scale is quantified by the “

Mezzi scale” factor , which relates the actual length

at radius r to its observed length

at the same radius:

The Mezzi scale factor

starts at 1 related to the observer scale, suggesting that the observed velocity is equal to the true velocity. The value of

is anticipated to reach its maximum at the galactic center, where the Mezzi effect induces the most significant distortion. The velocity of a star at its true radius

, should correspond to the scaled observed velocity

:

This is the only consideration to represent the idea that the discrepancies observed in galactic rotation curves may be due to an underestimation caused by the flow of space, rather than the presence of unseen matter or modifications to gravitational laws. The space flow model is consistent with the established principles of General Relativity and does not require alterations to either General Relativity or Newton’s laws of motion.

3. Approach

To interprets observed rotation curves through the Mezzi effect. This work assumes baryonic matter constitutes the total mass. And the galactic rotation adheres to Newtonian dynamics, thus here .

The discrepancies between observed velocities and Newtonian predictions are reconciled via space scale corrections quantified by the Mezzi scale factor. The analysis calculates this factor through iterative optimization process, that minimize of the deviations between scaled Newtonian velocities and observed velocities. The Newtonian velocity

is calculated based on baryonic mass

The total baryonic mass of each galaxy is derived from its luminous components, disk and bulge, assuming exponential and Hernquist profiles respectively [

21,

22]. These profiles are used to compute the enclosed mass at observed radii. The disk mass is modeled using an exponential surface density profile. The enclosed mass at radius r is given by [

23]:

The Mezzi effect introduces two principal modifications to reconcile observed galactic rotation velocities with Newtonian predictions. First, a uniform “Mezzi mass” coefficient is applied to the enclosed baryonic mass to correct the systematic underestimation of the luminous mass. This adjustment is consistent with the assumption of an underlying exponential mass distribution. Second, a radial scaling factor adjusts the observed velocities at different radii.

These parameters are simultaneously optimized via a YUKI algorithm, which iteratively minimizes the Euclidean norm of the discrepancy between the scaled Newtonian velocities

and the observed velocities

, where

is the number of considered radii for each galaxy. Consequently, the values of

and

, corresponding to the fitted velocity, are computed.

The YUKI algorithm employs a dynamic search space reduction strategy by defining a local search region around the best identified solutions. Exploitation focuses on refining promising solutions by gradually adjusting candidates within the local search region. Meanwhile, exploration introduces diversity by search outside the local search region, which help avoid the convergence to local optima. By these two strategies, this algorithm effectively tackles large scale global problems across various domains [

24].

The calibration of the scaling factors and algorithm parameters is performed systematically. The Mezzi scale factor , is defined such that it is equals 1 in regions to describe regions where the space scale distortion is negligible. And has no upper limit, allowing exploration of all possible values to determine the extent to which this distortion can affect observations, thus we considered constrained between 0 and 1. The minimum mass coefficient is set 1 and the maximum value is set to an exaggerated value of 100.

The algorithm parameters are defined as follows: the number of iterations is set to 50000, the population size for the search is 20, and EXP, the parameter that determines the percentage of solutions allocated for exploration, is set to 0.99.

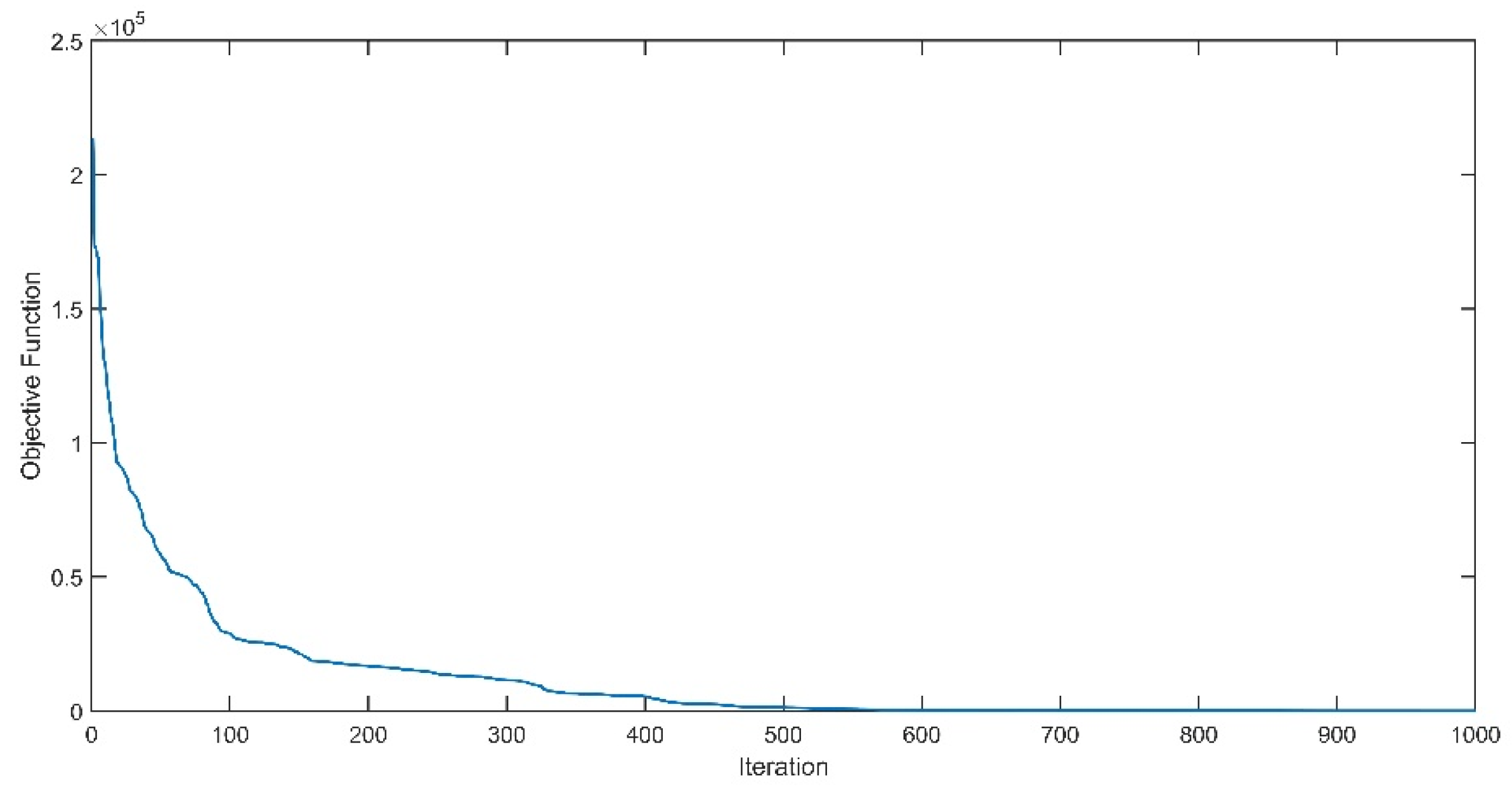

Figure 1 illustrates the convergence of the objective function for the galaxy NGC7793, highlighting the reduction in the error between the scaled Newtonian rotation curve and the observed rotation curve as the algorithm progresses.

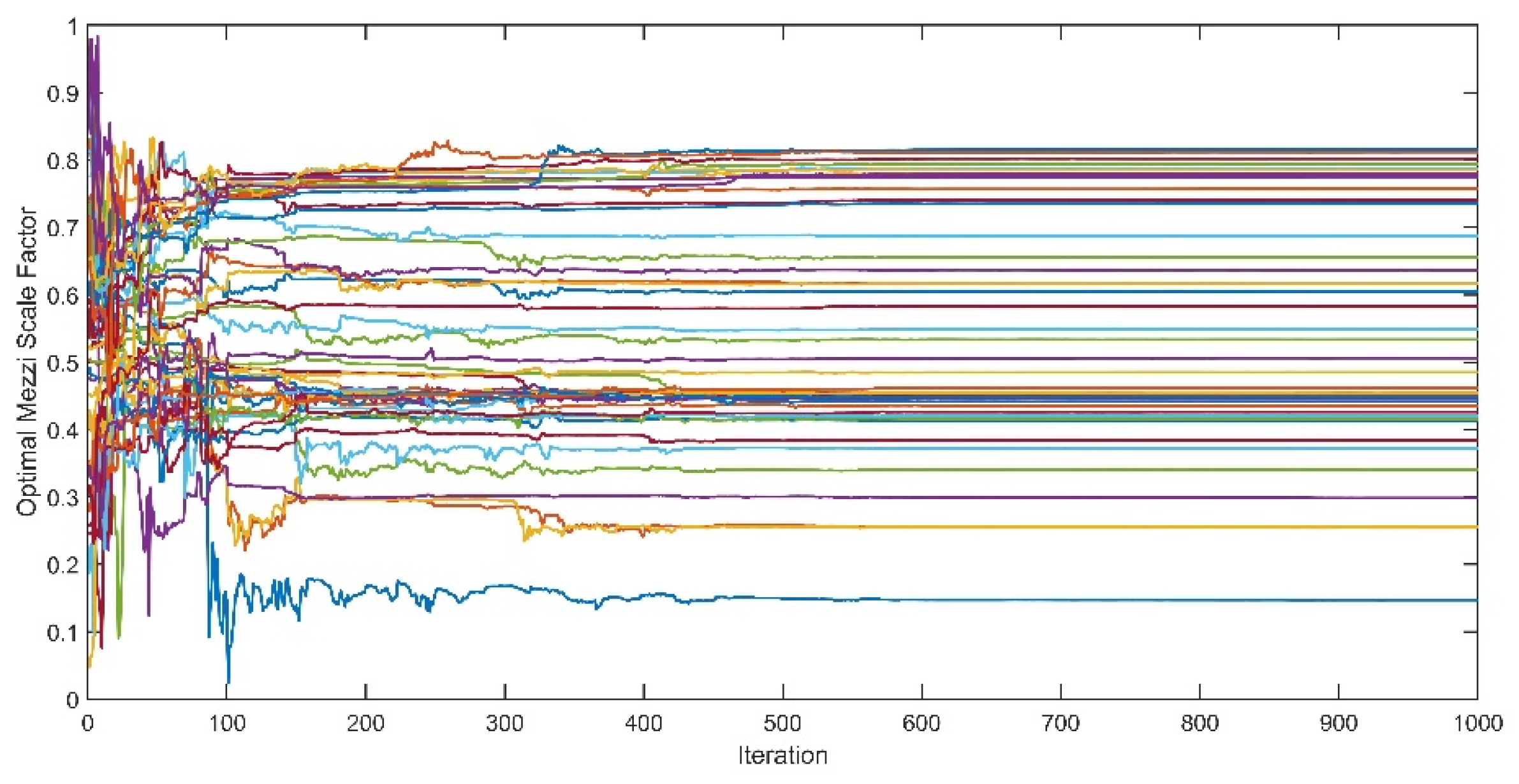

Figure 2 shows the convergence of the Mezzi scale factor at each radius

.

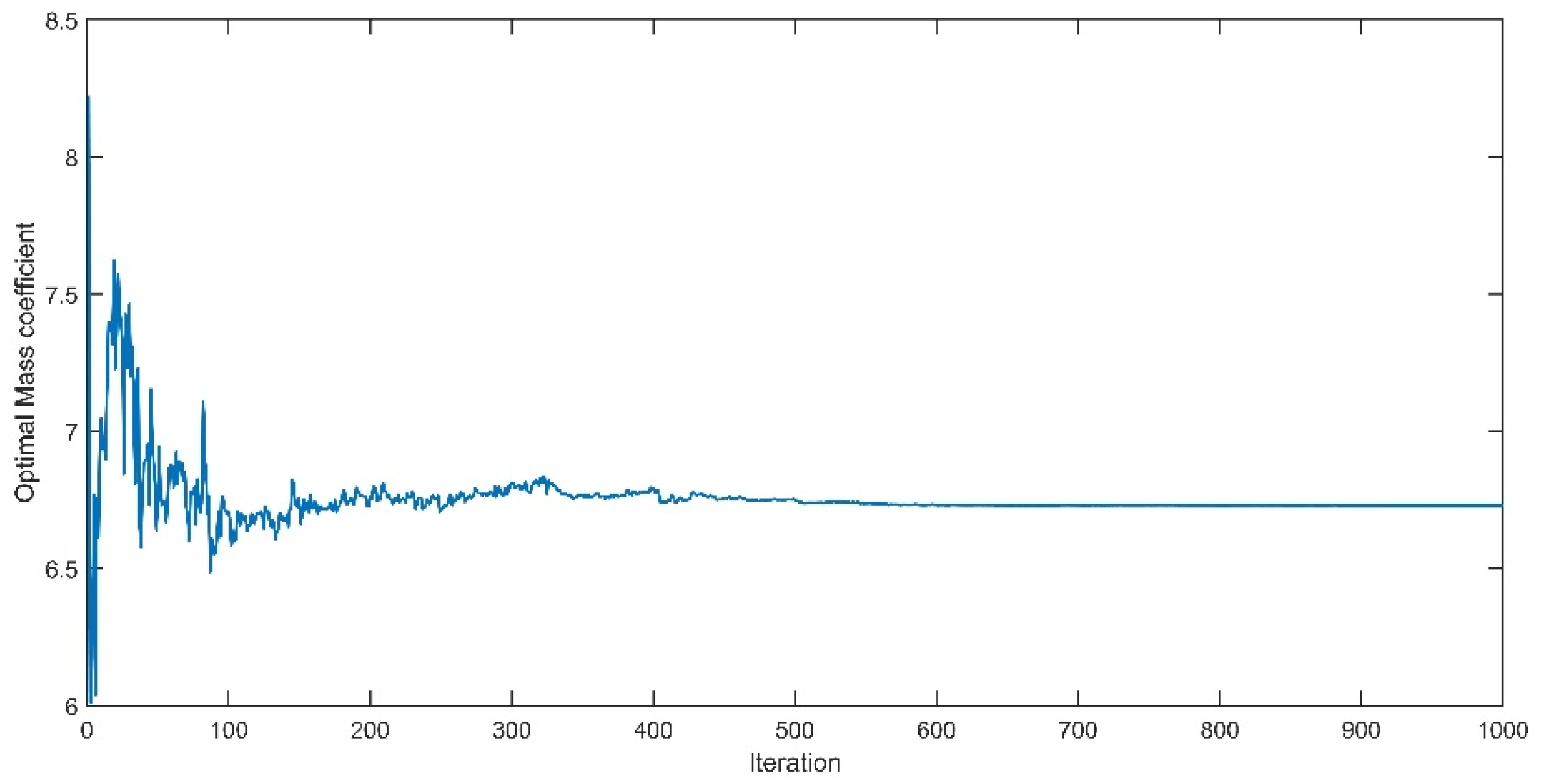

Figure 3 presents the convergence of the mass coefficient

.

4. Mezzi Scale Factor

To evaluate the results, the spatial underestimation quantified by the Mezzi effect should reflect the intrinsic curvature of the underlying spacetime curvature. The intrinsic Mezzi effect curvature can be expressed by the Gaussian curvature K [

25]. With

is the predicted Mezzi scale factor at the observed radius

.

On the other hand, the Ricci scalar curvature

is calculated from the enclosed mass gradient [

26]:

The findings are classified into three categories based on the Mezzi scale factor:

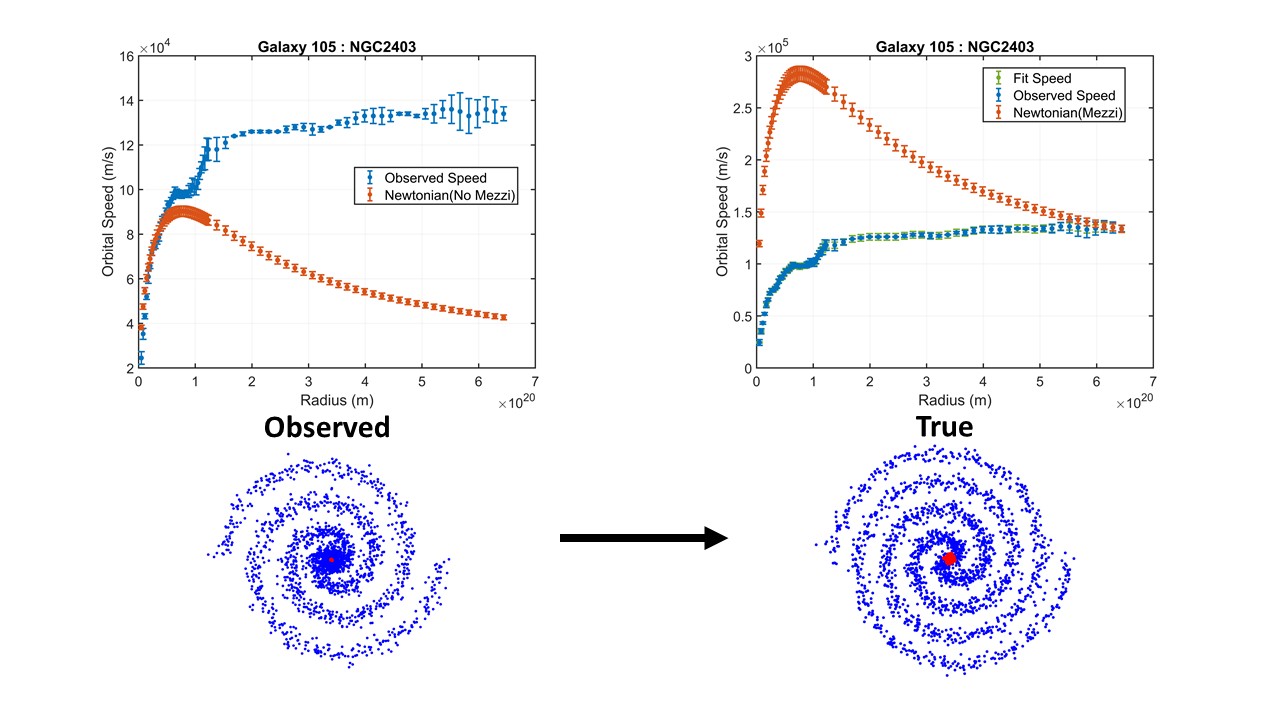

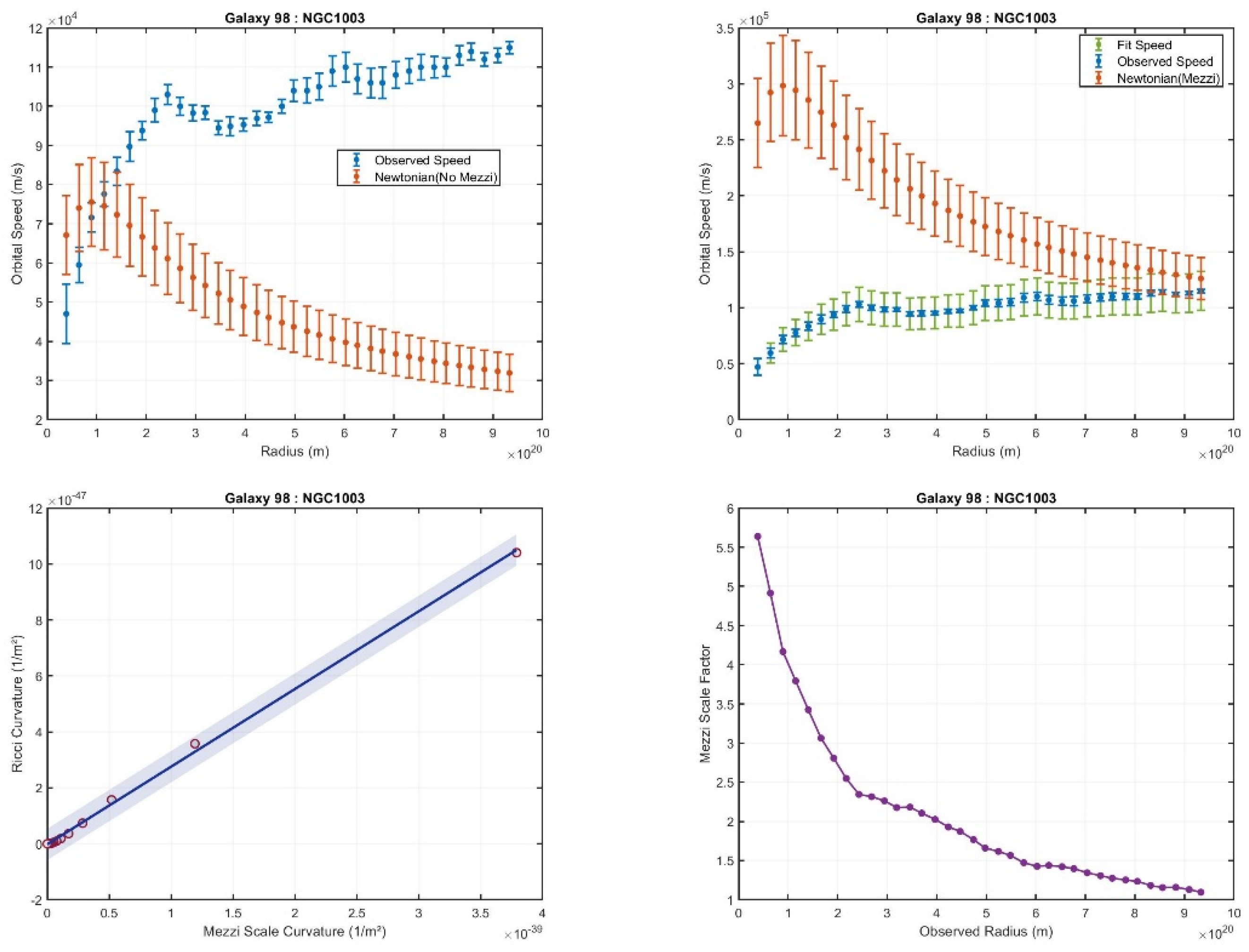

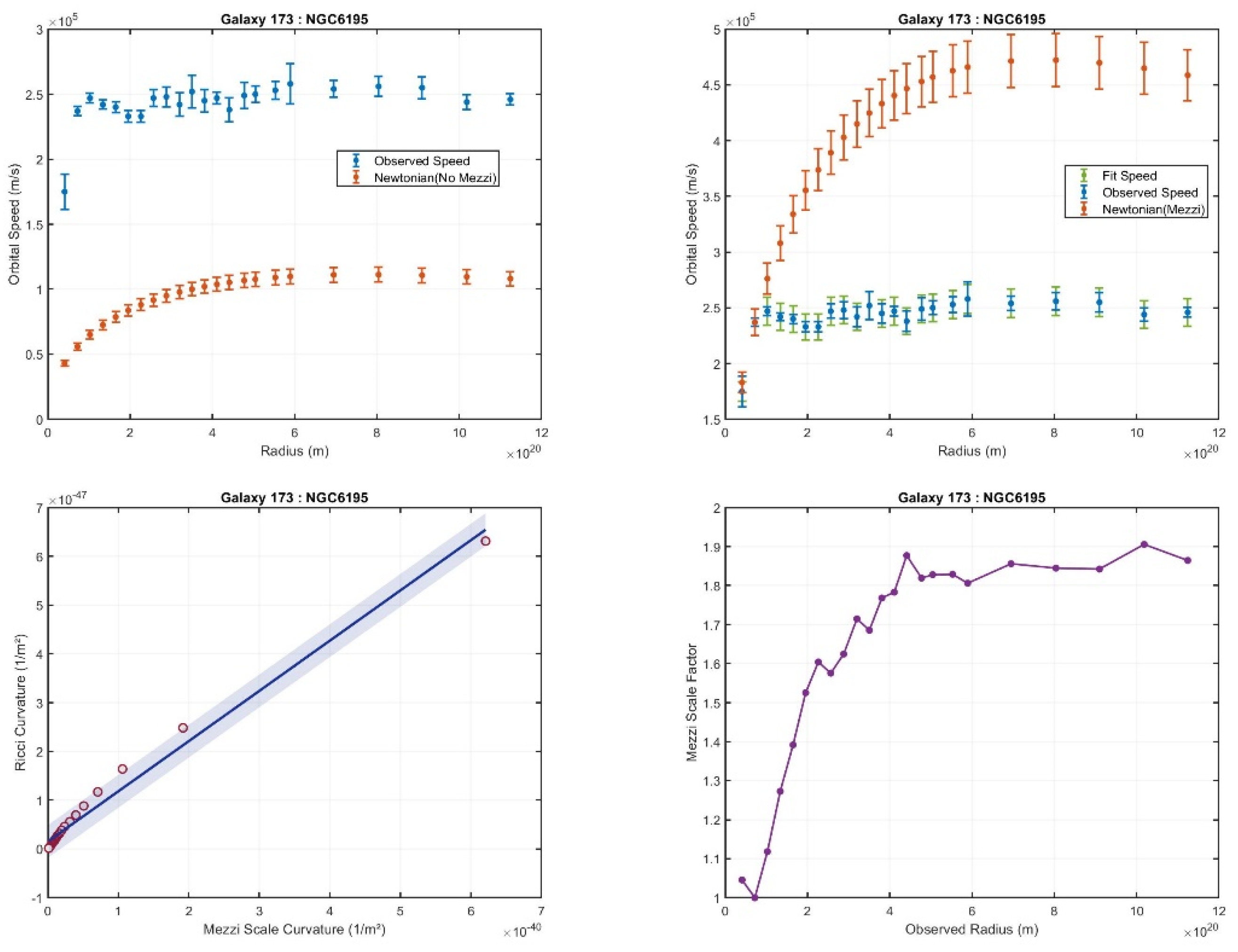

Expected Behavior: In 135 galaxies, the Mezzi scale factor exhibits the anticipated trend, reaching its maximum values near the galactic center and decreasing toward the outer edges. An example of this behavior is shown in

Figure 4.

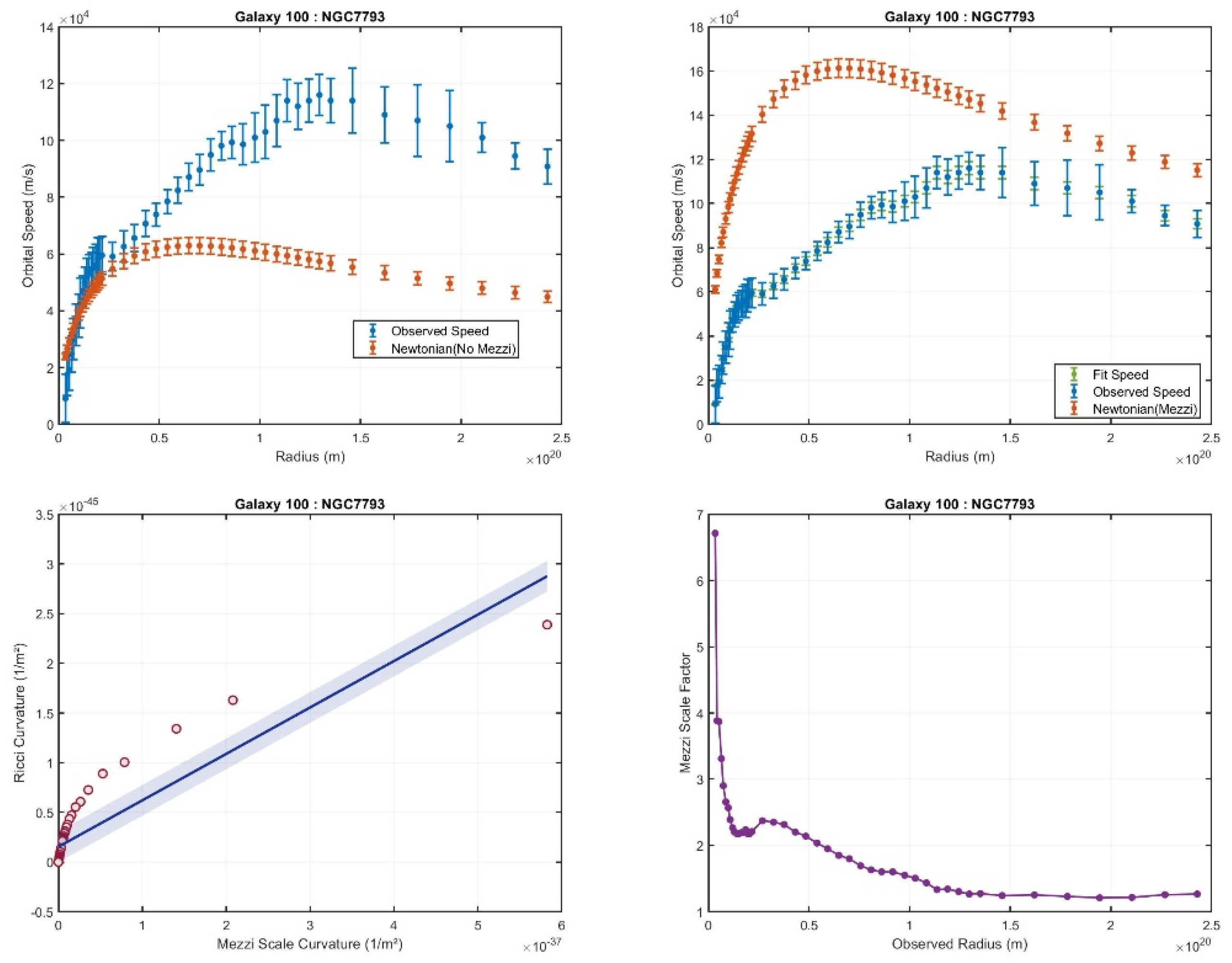

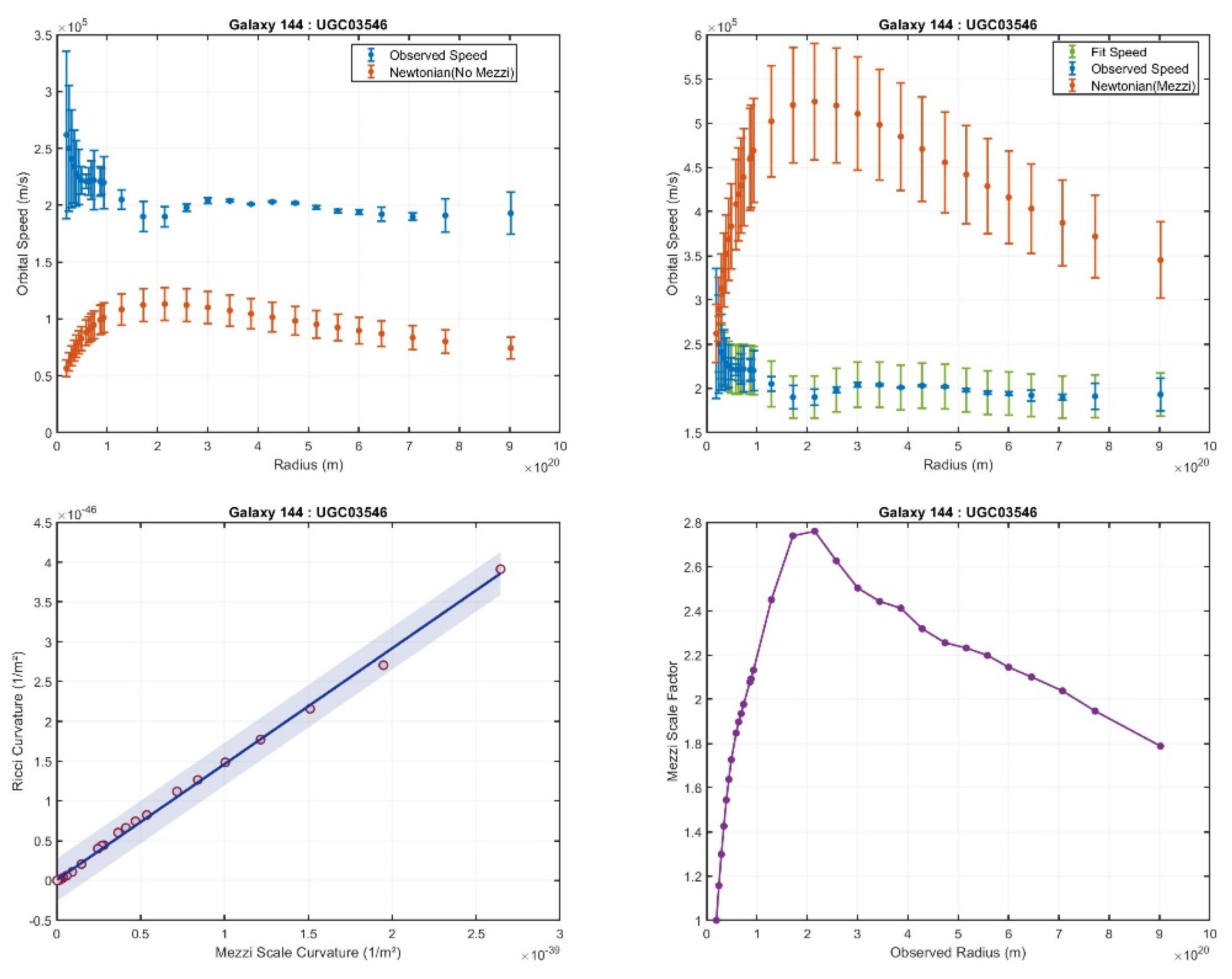

Deviations from the Expected Trend: In 37 galaxies, the expected trend is still observed, but with deviations beginning near the galactic center and extending to various radii. Among these, 16 galaxies show minor deviations, while 20 galaxies display significant deviations.

Figure 5 illustrates an example of a minor deviation, while

Figure 6 shows an example of a major deviation.

Reversed Behavior: In 3 galaxies, the Mezzi scale factor increases from the galactic center toward the outer edge, which contrasts with the expected trend. An example of this reversed behavior is shown in

Figure 7.

Top-left subfigure: Compares the observed rotation curve with the Newtonian prediction that does not account for the Mezzi effect, showing discrepancies between Newtonian and observed rotation curves.

Top-right subfigure: Displays the observed rotation curve alongside the Newtonian rotation curves that incorporate the Mezzi effect. This comparison illustrates the true velocities based on our assumptions in relation to the observed velocities.

Bottom-right subfigure: Depicts the Mezzi scale factor at various radii, highlighting its spatial variation across the galaxy.

Bottom-left subfigure: Displays a scaling relation plot, showing the intrinsic Mezzi effect curvature on the x-axis and the Ricci curvature on the y-axis. A linear fit is overlaid, with a confidence region indicating a correlation level of 0.98.

In cases where deviations from the expected Mezzi scale factor are observed, corresponding anomalies are seen in the orbital velocities. For slight deviations, discrepancies typically occur at points where the velocity trend is interrupted.

In cases of large deviations, the velocities near the galactic center are often higher than expected, leading to flat rotation curves in some galaxies. In other instances, the velocities near the center exceed those at the outer edges, which contrasts with the typical Newtonian behavior.

In galaxies displaying a reversed scaling trend, the discrepancies are similar to those found in large deviation cases, but with a much larger divergence between the observed velocities and the Newtonian velocities (excluding the Mezzi effect). This indicates a more pronounced departure from conventional Newtonian predictions.

Within the context of this study, these deviations indicate that observed velocities may be significantly affected by accumulated distance underestimation errors, which could introduce substantial distortions in the inferred orbital dynamics, this is backed by the following observation.

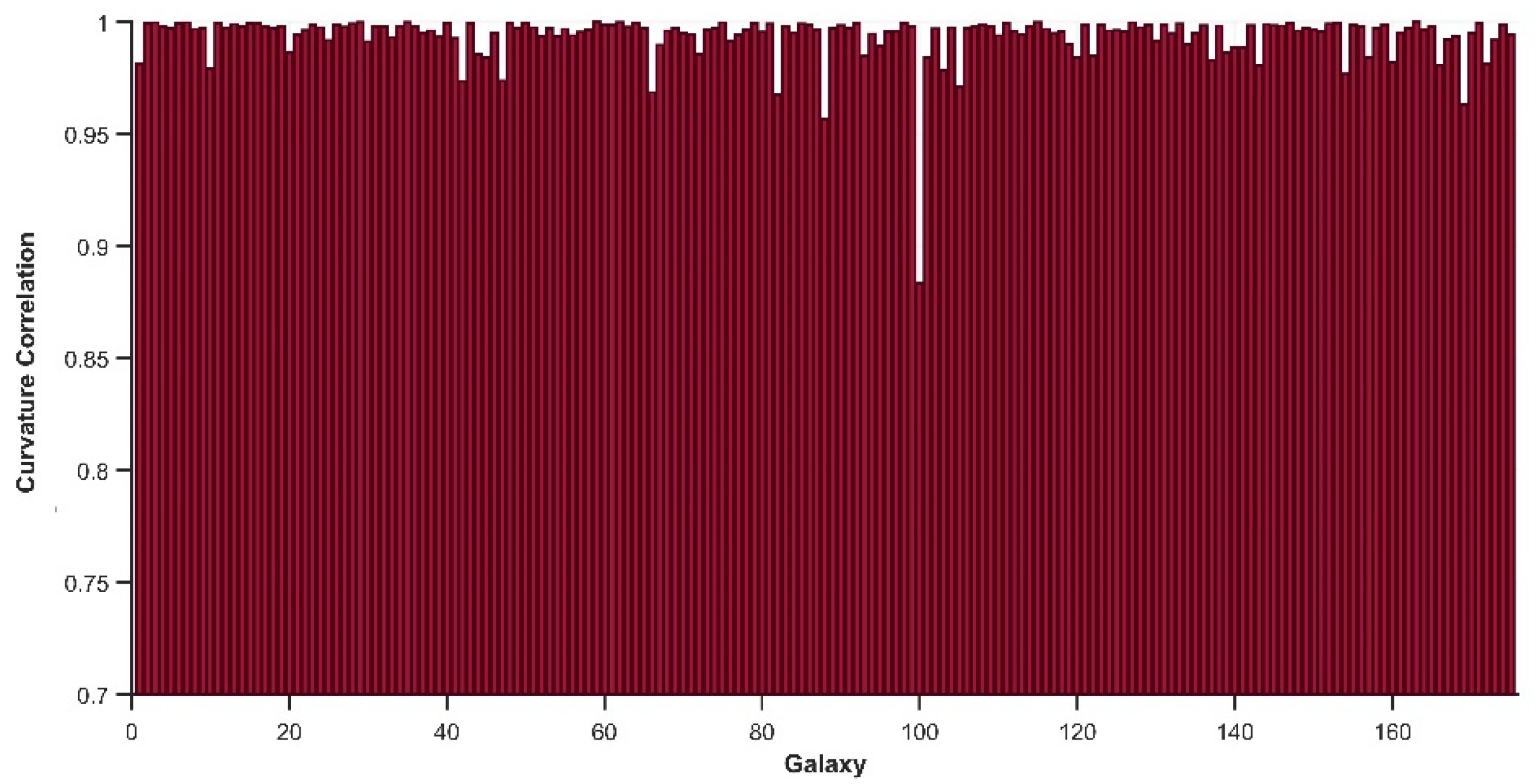

Although there exist galaxies that do not perfectly conform to the expected Mezzi scale factor trend, all galaxies exhibit a high correlation between the intrinsic Mezzi effect curvature and Ricci curvature calculated from the observed masses and radii. The lowest correlation is observed in galaxy NGC7793, shown in

Figure 5, where the correlation falls below 0.9 (See

Figure 8). Suggesting that the Mezzi effect curvature and Ricci curvature are associated in how they reflect the observation.

These high correlations imply that the same geometric behavior responsible for Ricci scalar results is also dictating the observational underestimation in spatial scale. This indicate that the observational underestimation of orbital velocities is not merely artifacts, but are genuinely linked to the gravitational geometry, and support the idea that the infall of space, and the associated Mezzi effect, is a direct manifestation of the local curvature induced by the baryonic mass.

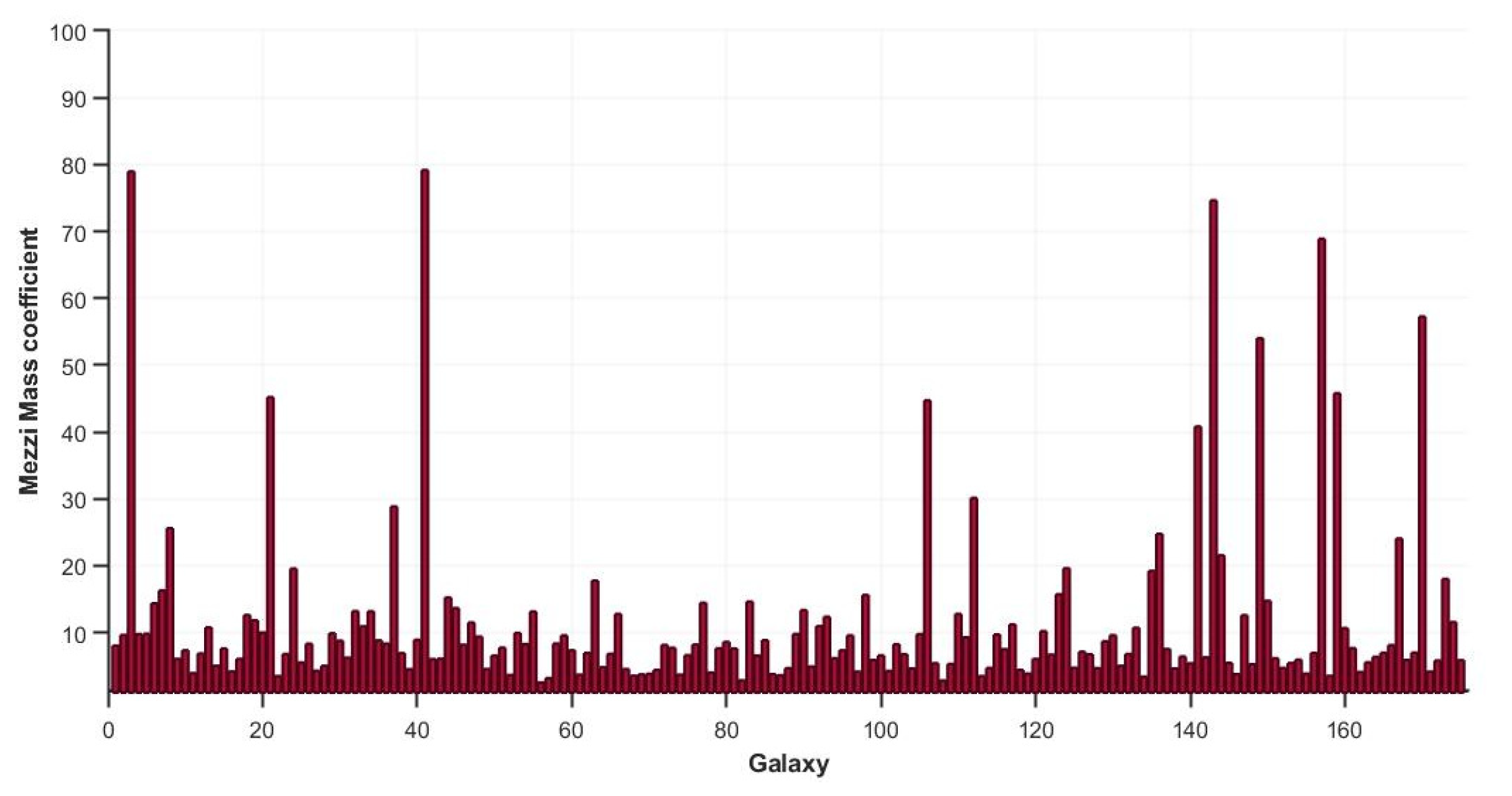

Figure 9 illustrates the Mezzi mass coefficients for each galaxy, ranging from 2.5 for galaxy UGC06667 to 79.17 for galaxy NGC2915. The average mass coefficient is 11.35, which implies that the overall unaccounted baryonic mass could be an order of magnitude greater than what our observations currently suggest.

5. Discussion

This study presents the Mezzi effect as a novel framework to address the discrepancies in galactic rotation curves without relying on dark matter or modifications to gravitational laws. By conceptualizing gravity through a spatial flow framework, the analysis of 175 galaxies, from the SPARC dataset, demonstrates that the Mezzi effect reconciles observed rotation curves with Newtonian predictions.

The strong correlation between the Mezzi scale factor curvature and the Ricci scalar curvature further supports the alignment of this approach with the principles of general relativity. Importantly, this framework preserves the validity of both Newtonian dynamics and general relativity, offering an alternative to the dark matter hypotheses.

Based on this dataset, the results of this work suggest that the amount of unaccounted mass in the universe is possibly twice that predicted by current dark matter models. While implying that the baryonic mass constitutes the entirety of the mass, and that no additional dark matter exists.

Moreover, the flow gravity interpretation provides new insights into cosmic expansion, suggesting a potential explanation for cosmological redshift, typically attributed to dark energy. In this context, the observed redshift may result from the elongation of electromagnetic waves as they propagate along the direction of space flow. Additionally, it suggests that such redshift could be relative to the observer, providing a potential nuanced understanding of this cosmological phenomena.

References

- Khelashvili, M., A. Rudakovskyi, and S. Hossenfelder, Dark matter profiles of SPARC galaxies: a challenge to fuzzy dark matter. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2023. 523(3): p. 3393-3405.

- Wang, L. and D.-M. Chen, Comparison of Modeling SPARC spiral galaxies’ rotation curves: halo models vs. MOND. Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2021. 21(11): p. 271.

- Li, P., et al., A comprehensive catalog of dark matter halo models for SPARC galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2020. 247(1): p. 31.

- Feng, J.L., Dark matter candidates from particle physics and methods of detection. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2010. 48(1): p. 495-545.

- Misiaszek, M. and N. Rossi, Direct detection of dark matter: A critical review. Symmetry, 2024. 16(2): p. 201.

- Einstein, A., The general theory of relativity, in The meaning of relativity. 1922, Springer. p. 54-75.

- Einstein, A., Die feldgleichungen der gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1915: p. 844-847.

- Einstein, A., Explanation of the perihelion motion of Mercury by means of the general theory of relativity, in A Source Book in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 1900–1975. 1979, Harvard University Press. p. 820-825.

- Braeck, S. and Ø. Grøn, A river model of space. The European Physical Journal Plus, 2013. 128: p. 1-18.

- Hamilton, A.J. and J.P. Lisle, The river model of black holes. American Journal of Physics, 2008. 76(6): p. 519-532.

- Cahill, R.T., Quantum foam, gravity and gravitational waves. arXiv preprint physics/0312082, 2003.

- Kanai, Y., M. Siino, and A. Hosoya, Gravitational collapse in Painlevé-Gullstrand coordinates. Progress of theoretical physics, 2011. 125(5): p. 1053-1065.

- Martel, K. and E. Poisson, Regular coordinate systems for Schwarzschild and other spherical spacetimes. American Journal of Physics, 2001. 69(4): p. 476-480.

- Lelli, F., S.S. McGaugh, and J.M. Schombert, SPARC: Mass models for 175 disk galaxies with Spitzer photometry and accurate rotation curves. The Astronomical Journal, 2016. 152(6): p. 157.

- Gullstrand, A., Allgemeine lösung des statischen einkörperproblems in der Einsteinschen gravitationstheorie. 1922: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Painlevé, P., La mécanique classique et la théorie de la relativité. Comptes Rendus Academie des Sciences (serie non specifiee), 1921. 173: p. 677-680.

- Dey, R., et al., Black hole quantum atmosphere for freely falling observers. Physics Letters B, 2019. 797: p. 134828.

- Ziprick, J. and G. Kunstatter, Spherically Symmetric Black Hole Formation in Painlev\’e-Gullstrand Coordinates. arXiv preprint arXiv:0812.0993, 2008.

- Volovik, G., Painlevé–Gullstrand coordinates for Schwarzschild–de Sitter spacetime. Annals of Physics, 2023. 449: p. 169219.

- Martin, T., General Relativity and Spatial Flows: I. Absolute Relativistic Dynamics. arXiv preprint gr-qc/0006029, 2000.

- Freeman, K.C., On the disks of spiral and S0 galaxies. Astrophysical Journal, vol. 160, p. 811, 1970. 160: p. 811.

- Hernquist, L., An analytical model for spherical galaxies and bulges. Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 (ISSN 0004-637X), vol. 356, June 20, 1990, p. 359-364., 1990. 356: p. 359-364.

- Binney, J. and S. Tremaine, Galactic dynamics. 2011: Princeton university press.

- Benaissa, B., et al., A novel exploration strategy for the YUKI algorithm for topology optimization with metaheuristic structural binary distribution. Engineering Optimization, 2024: p. 1-21.

- Modes, C.D., K. Bhattacharya, and M. Warner, Gaussian curvature from flat elastica sheets. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 2011. 467(2128): p. 1121-1140.

- Stephani, H., et al., Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations. 2009: Cambridge university press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).