Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Proposal

2.1. Key Definitions

2.2. Conceptual Rationale

2.3. Scope and Requirements

2.4. Prerequisites

- Population: Adults aged 18–75 with primary hypertension,

- Intervention: Daily oral administration of Drug A,

- Comparison: Placebo,

- Outcome: Mean change in systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks.

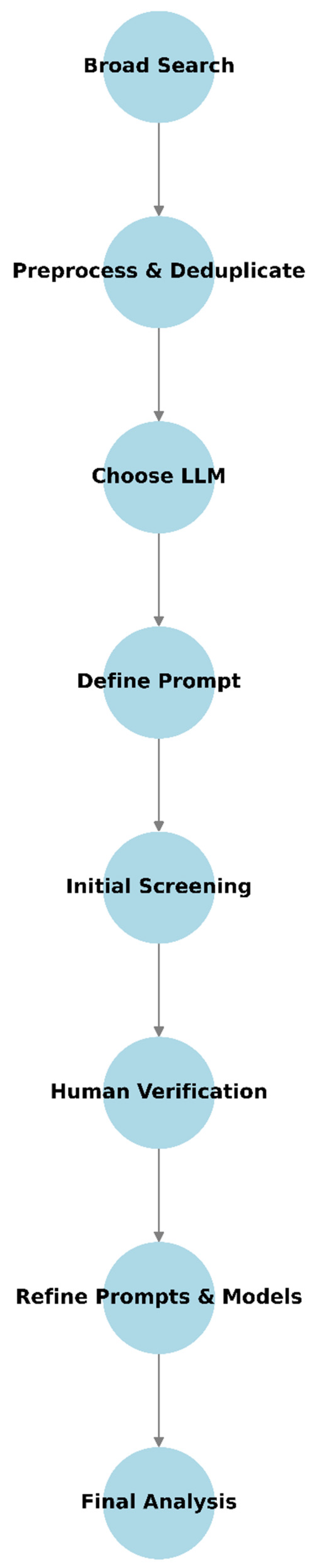

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

3.1. Conduct a Broad Database Search

3.2. Preprocess and Deduplicate Records

3.3. Choose the Right LLM(s) and Prompt

3.4. Understanding Prompt Fundamentals and Challenges

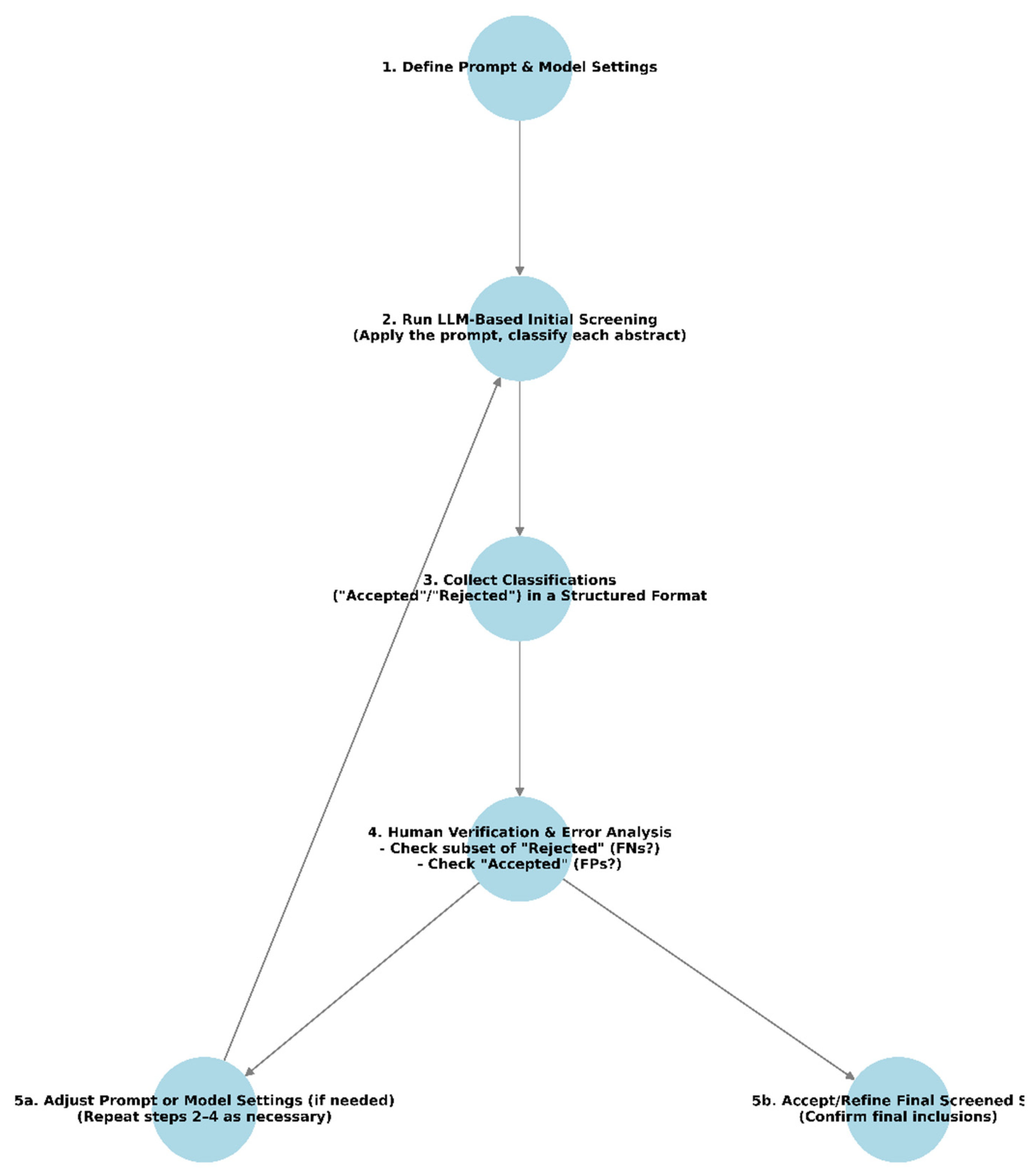

3.5. Perform Initial Screening

3.6. Human Verification and Error Analysis

3.7. Best Practices and Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulrow, C.D. Systematic Reviews: Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994, 309, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Med Sci Monit 2021, 27, e934475-1. [Google Scholar]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Espinós, E.; Hernández, V.; Domínguez-Escrig, J.; et al. Methodology of a systematic review PALABRAS CLAVE. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dickersin, K.; Scherer, R.; Lefebvre, C. Systematic reviews: identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. Bmj 1994, 309, 1286–1291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waffenschmidt, S.; Knelangen, M.; Sieben, W.; et al. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: a methodological systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Booth, A.; Varley-Campbell, J.; et al. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, J.C.; Singh, J.; Hsieh, J.; Fehlings, M.G. Reviews Methodology of Systematic Reviews and Recommendations.

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 2019, ED000142. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.; Lecky, F. The NICE guidelines in the real world: a practical perspective. Emerg Med J 2004, 21, 404. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dinter, R.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Catal, C. Automation of systematic literature reviews: A systematic literature review. Inf Softw Technol 2021, 136, 106589. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Nayfeh, T.; Tetzlaff, J.; et al. Error rates of human reviewers during abstract screening in systematic reviews. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.E.K.; Lines, R.L.J.; Gucciardi, D.F.; Ng, L. Research Screener: a machine learning tool to semi-automate abstract screening for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Ameen, D.; Zarnegar, A. Tools to support the automation of systematic reviews: a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol 2022, 144, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allot, A.; Lee, K.; Chen, Q.; et al. LitSuggest: a web-based system for literature recommendation and curation using machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W352–W358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, I.J.; Kuiper, J.; Wallace, B.C. RobotReviewer: evaluation of a system for automatically assessing bias in clinical trials. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2016, 23, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiritchenko, S.; De Bruijn, B.; Carini, S.; et al. ExaCT: automatic extraction of clinical trial characteristics from journal publications. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhu, B.; Prathamesh, R.P.; Sameera, M.B.; KumaraSwamy, S. The evolution of large language model: Models, applications and challenges. 2024 International Conference on Current Trends in Advanced Computing (ICCTAC); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Sang, J.; Arora, R.; et al. Prompting is all you need: LLMs for systematic review screening. medRxiv 2024, 2024–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Scherbakov, D.; Hubig, N.; Jansari, V.; et al. The emergence of Large Language Models (LLM) as a tool in literature reviews: an LLM automated systematic review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240904600. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.-Y.; Shen, C.; Ji, Y.-L.; et al. Accuracy of Large Language Models for Literature Screening in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dennstädt, F.; Zink, J.; Putora, P.M.; et al. Title and abstract screening for literature reviews using large language models: an exploratory study in the biomedical domain. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisha, Q.; Put, S.; Kappenberg, J.; et al. Can large language models replace humans in systematic reviews? Evaluating GPT -4’s efficacy in screening and extracting data from peer-reviewed and grey literature in multiple languages. Res Synth Methods 2024, 15, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, T.; Gonen, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Prompting Language Models for Linguistic Structure. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Chaves, F.M.; Jennings, M.J.; Atalaia, A.; et al. Transforming literature screening: The emerging role of large language models in systematic reviews. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberum, J.-L.; Töws, M.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; et al. (2025) Large language models for conducting systematic reviews: on the rise, but not yet ready for use—a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol 11 1746. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:230318223. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, A. Prompt engineering for large language models. Available at SSRN 4504303. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, H.; Mecke, L.; Lehmann, F.; et al. How to prompt? Opportunities and challenges of zero-and few-shot learning for human-AI interaction in creative applications of generative models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:220901390. [Google Scholar]

- Cottam, J.A.; Heller, N.C.; Ebsch, C.L.; et al. Evaluation of Alignment: Precision, Recall, Weighting and Limitations. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); IEEE, 2513; pp. 2513–2519. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Yao, Z.; et al. A solution-based LLM API-using methodology for academic information seeking. arXiv 2024. (accessed on day month year). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.V.P.; Ahmed, M.D.S. Beyond Clouds: Locally Runnable LLMs as a Secure Solution for AI Applications. Digital Society 2024, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisong, E. Google Colaboratory. In: Bisong E (ed) Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners. Apress, Berkeley, CA, pp 59–64. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mckinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In: van der Walt S, Millman J (eds) Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. pp 51–56. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorov, D. Harnessing Python 3.11 and Python Libraries for LLM Development. In: Introduction to Python and Large Language Models: A Guide to Language Models. Springer, pp 303–368. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, A.K.; Gorenstein, L.; Lentner, G. Demystifying Python Package Installation with conda-env-mod. In: 2020 IEEE/ACM International Workshop on HPC User Support Tools (HUST) and Workshop on Programming and Performance Visualization Tools (ProTools). IEEE, pp 27–37. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar, S.; Dubey, T.; Mukherjee, K.; et al. Towards optimizing the costs of llm usage. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240201742. [Google Scholar]

- Irugalbandara, C.; Mahendra, A.; Daynauth, R.; et al. Scaling down to scale up: A cost-benefit analysis of replacing OpenAI’s LLM with open source SLMs in production. In: 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS). IEEE, pp 280–291. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Mallick, A.; Wang, C.; et al. Hybrid llm: Cost-efficient and quality-aware query routing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240414618. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zaharia, M.; Zou, J. Frugalgpt: How to use large language models while reducing cost and improving performance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:230505176. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Li, K.; Xu, M.; et al. On protecting the data privacy of large language models (llms): A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240305156. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Duan, J.; Xu, K.; et al. A survey on large language model (llm) security and privacy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. High-Confidence Computing 100211. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Yu, S.; Li, J.; et al. Firewallm: A portable data protection and recovery framework for llm services. In: International Conference on Data Mining and Big Data. Springer, pp 16–30. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feretzakis, G.; Verykios, V.S. Trustworthy AI: Securing sensitive data in large language models. AI 2024, 5, 2773–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO. Qual Health Res 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Bruun Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J Clin Epidemiol 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D. A Review of the PubMed PICO Tool: Using Evidence-Based Practice in Health Education. Health Promot Pract 2020, 21, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scells, H.; Zuccon, G.; Koopman, B.; et al. Integrating the Framing of Clinical Questions via PICO into the Retrieval of Medical Literature for Systematic Reviews. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp 2291–2294. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chigbu, U.E.; Atiku, S.O.; Du Plessis, C.C. The Science of Literature Reviews: Searching, Identifying, Selecting, and Synthesising. Publications 2023, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, L.J.; Munro, S. The literature review: demystifying the literature search. Diabetes Educ 2004, 30, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, M.; Hval, G.; Tornes, R.A.; et al. Optimizing the literature search: coverage of included references in systematic reviews in Medline and Embase. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2023, 111, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature. Database 2011, 2011, baq036–baq036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D. Systematic Literature Searching and the Bibliographic Database Haystack.

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Kim, W.; Wilbur, W.J. Evaluation of query expansion using MeSH in PubMed. Inf Retr Boston 2009, 12, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stuart, D. Database search translation tools: MEDLINE transpose, ovid search translator, and SR-accelerator polyglot search translator. Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries 2023, 20, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Adomavicius, G.; Burtch, G.; Ren, Y. Mind the gap: Accounting for measurement error and misclassification in variables generated via data mining. Information Systems Research 2018, 29, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, C.; Colangelo, M.T.; Guizzardi, S.; et al. A Zero-Shot Comparison of Large Language Models for Efficient Screening in Periodontal Regeneration Research. Preprints (Basel) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, L.; Nasim, A. Comparison and Analysis of Large Language Models (LLMs). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Feng, X.; et al. Extending context window of large language models from a distributional perspective. arXiv 2024, arXiv:241001490. [Google Scholar]

- Beurer-Kellner, L.; Fischer, M.; Vechev, M. Prompting is programming: A query language for large language models. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 2023, 7, 1946–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo, M.T.; Guizzardi, S.; Meleti, M.; et al. How to Write Effective Prompts for Screening Biomedical Literature Using Large Language Models. Preprints (Basel) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. ACM Trans Inf Syst 2025, 43, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R. Strategies to mitigate hallucinations in large language models. Applied Marketing Analytics 2024, 10, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gosmar, D.; Dahl, D.A. Hallucination Mitigation using Agentic AI Natural Language-Based Frameworks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:250113946. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. Measuring the Impact of Hallucinations on Human Reliance in LLM Applications. Journal of Robotic Process Automation, AI Integration, and Workflow Optimization 2025, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, H.T.; Chu, C.X.; Paulheim, H. Do LLMs really adapt to domains? An ontology learning perspective. In: International Semantic Web Conference. Springer, pp 126–143. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Duenas, T.; Ruiz, D. The risks of human overreliance on large language models for critical thinking. Research Gate 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Sterne, J.A.C. Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 349–374. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goossen, K.; Tenckhoff, S.; Probst, P.; et al. Optimal literature search for systematic reviews in surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2018, 403, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ewald, H.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; et al. Searching two or more databases decreased the risk of missing relevant studies: a metaresearch study. J Clin Epidemiol 2022, 149, 154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Carter, P. Established search filters may miss studies when identifying randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2019, 112, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E. Comparative Analysis of Open Source and Proprietary Large Language Models: Performance and Accessibility. Advances in Computer Sciences 2024, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S. A Quick Review of Machine Learning Algorithms. In: 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COMITCon). IEEE, pp 35–39. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Jin, Q.; Zhu, K.; et al. Prioritizing safeguarding over autonomy: Risks of llm agents for science. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240204247. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Chua, M.; Rickard, M.; Lorenzo, A. ChatGPT and large language model (LLM) chatbots: The current state of acceptability and a proposal for guidelines on utilization in academic medicine. J Pediatr Urol 2023, 19, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Gupta, S.; Singh, S.N. A comprehensive survey of bias in llms: Current landscape and future directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240916430. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, E.; Parwani, A.; Baig, M.M.; Singh, R. Challenges and barriers of using large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT for diagnostic medicine with a focus on digital pathology–a recent scoping review. Diagn Pathol 2024, 19, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Barman, K.G.; Wood, N.; Pawlowski, P. Beyond transparency and explainability: on the need for adequate and contextualized user guidelines for LLM use. Ethics Inf Technol 2024, 26, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Barman, K.G.; Caron, S.; Claassen, T.; De Regt, H. Towards a benchmark for scientific understanding in humans and machines. Minds Mach (Dordr) 2024, 34, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.; Afroogh, S.; Xu, Y.; Phillips, C. Navigating llm ethics: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240618841. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, R.; Gudivada, V. A review of current trends, techniques, and challenges in large language models (llms). Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 2074. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).