Submitted:

18 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. CliZod

1.2. Relevancy Ranking

1.2.1. Problem Definition

1.2.2. Background

1.3. Research Questions

- RQ1

- How does an LLM based assessor utilising a QA framework compared to baseline models utilising review title and selection criteria?

- RQ2

- Does the label granularity effect the ranking performance of an LLM based assessor utilising a QA framework for climate sensitive zoonotic disease?

- RQ3

- Does the ranking performance of an LLM based assessor generalise across climate sensitive zoonotic disease datasets with varying relevance rate?

- RQ4

- Does CoT rationale provided by an LLM assist a human reviewer’s ability to detect misclassifications in SLR?

1.4. Contribution

- Proposing a system to extract, store and share disease model parameters for climate sensitive zoonotic diseases modelling.

- Introducing and validating the use of an LLM-based assessor for ranking primary studies by utilising a QA framework.

- Evaluate the impact of label granularity on ranking performance to improve early stage recall quality

- Demonstrate that the proposed LLM-based assessor can manage highly skewed datasets and generalise across diverse climate sensitive zoonotic disease literature.

- Validate the utility of CoT generated reasoning text for human reviewers to enhance transparency and trust.

2. Methodology

2.1. Dataset

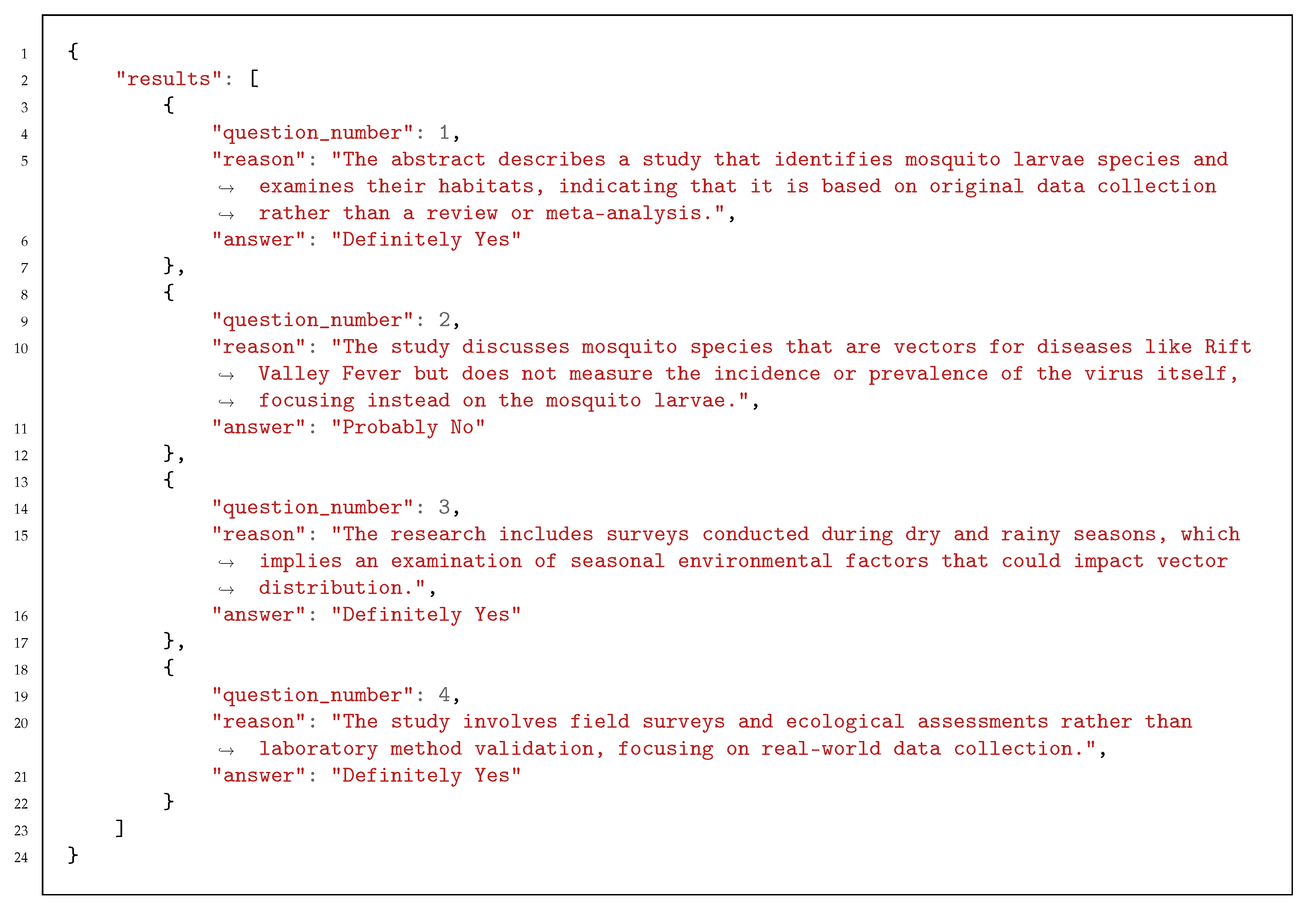

2.2. QA Framework

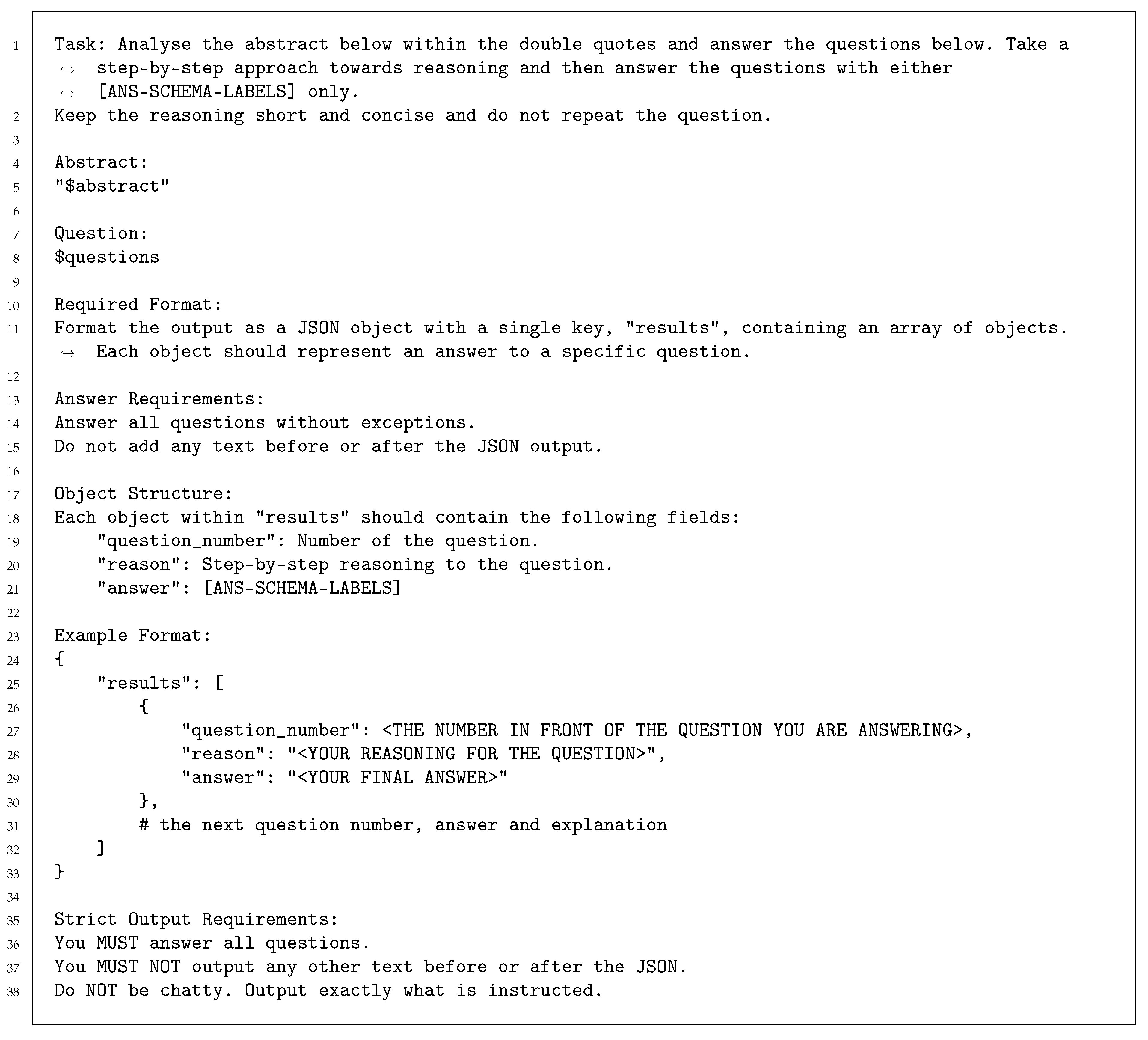

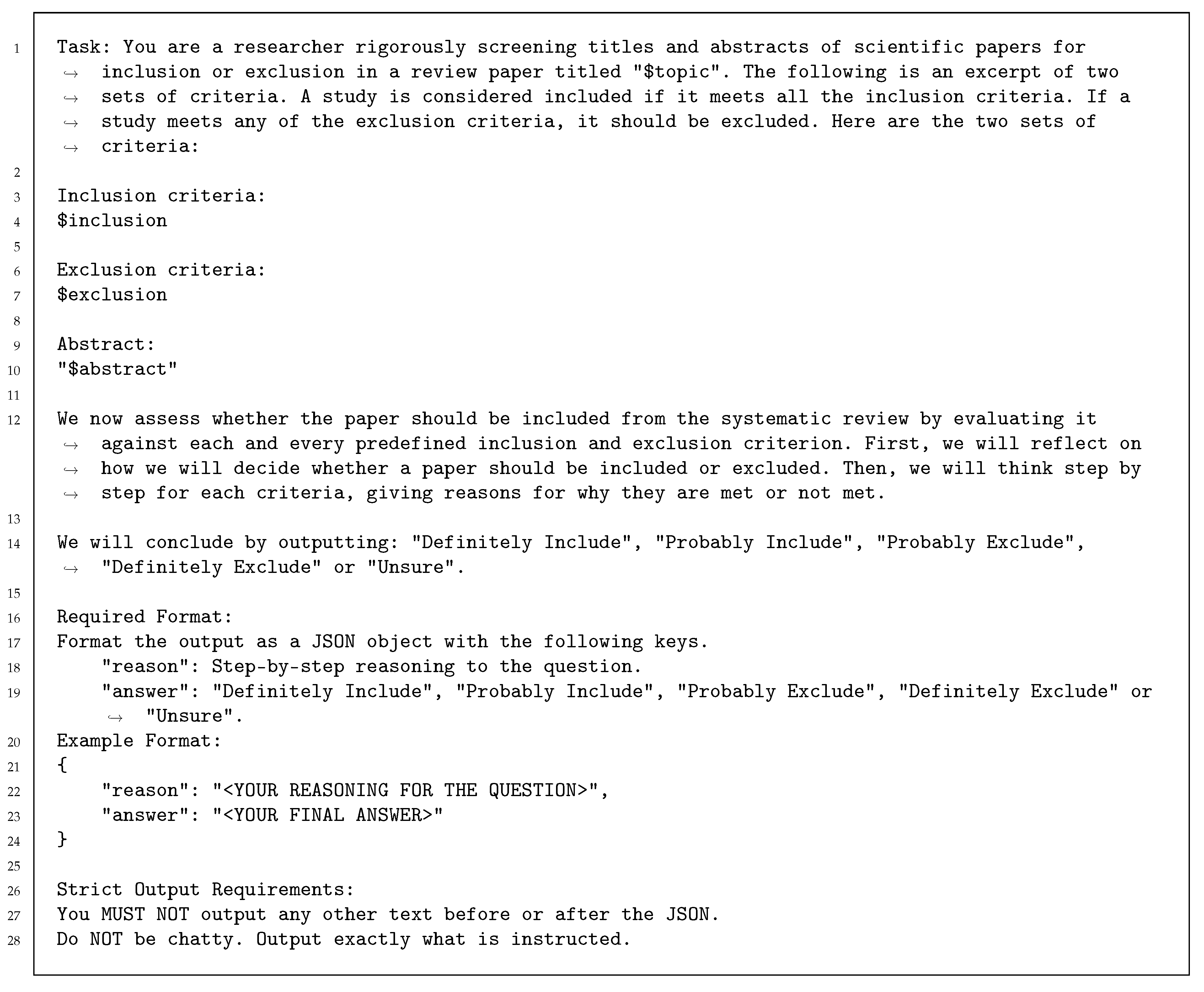

2.3. Prompts

2.4. Answer Labels

2.5. Relevancy ranking

- be the eligibility questions derived from the selection criteria.

- be the set of predicate answers for each question in document d, and

- be a predefined weight reflecting the importance of each question .

2.6. Models

2.6.1. Baseline Models

2.6.2. Large Language Models

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

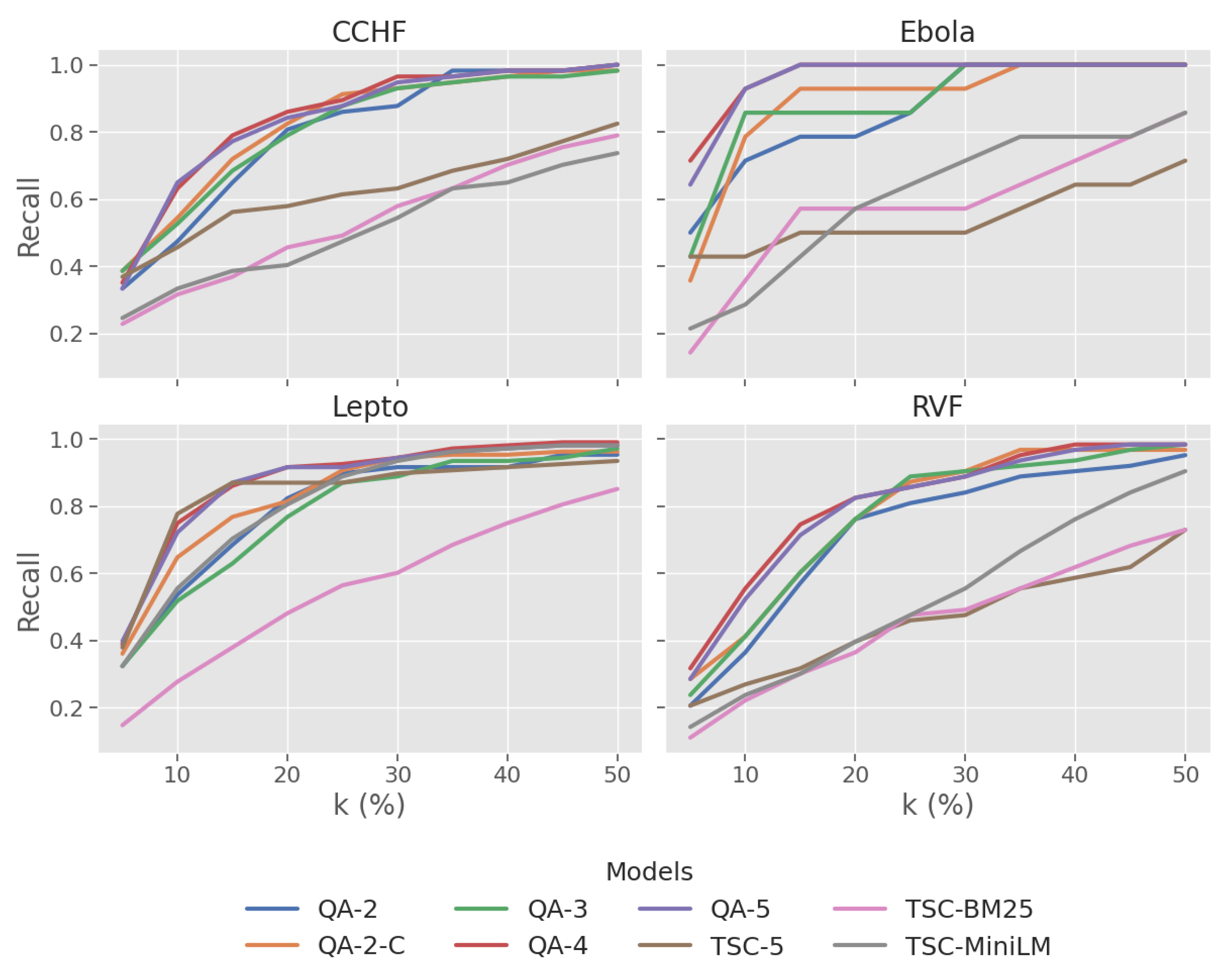

Recall @ k%

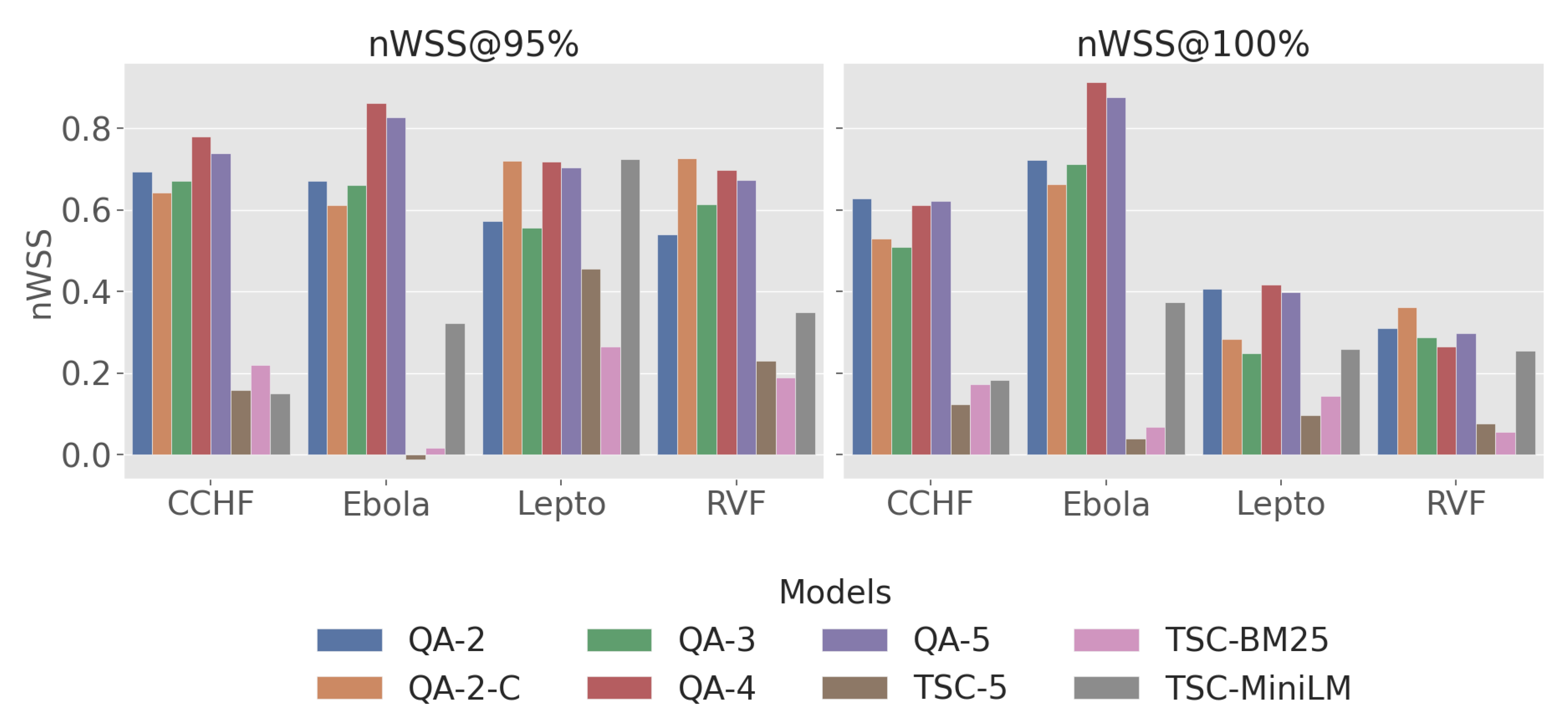

nWSS @ r%

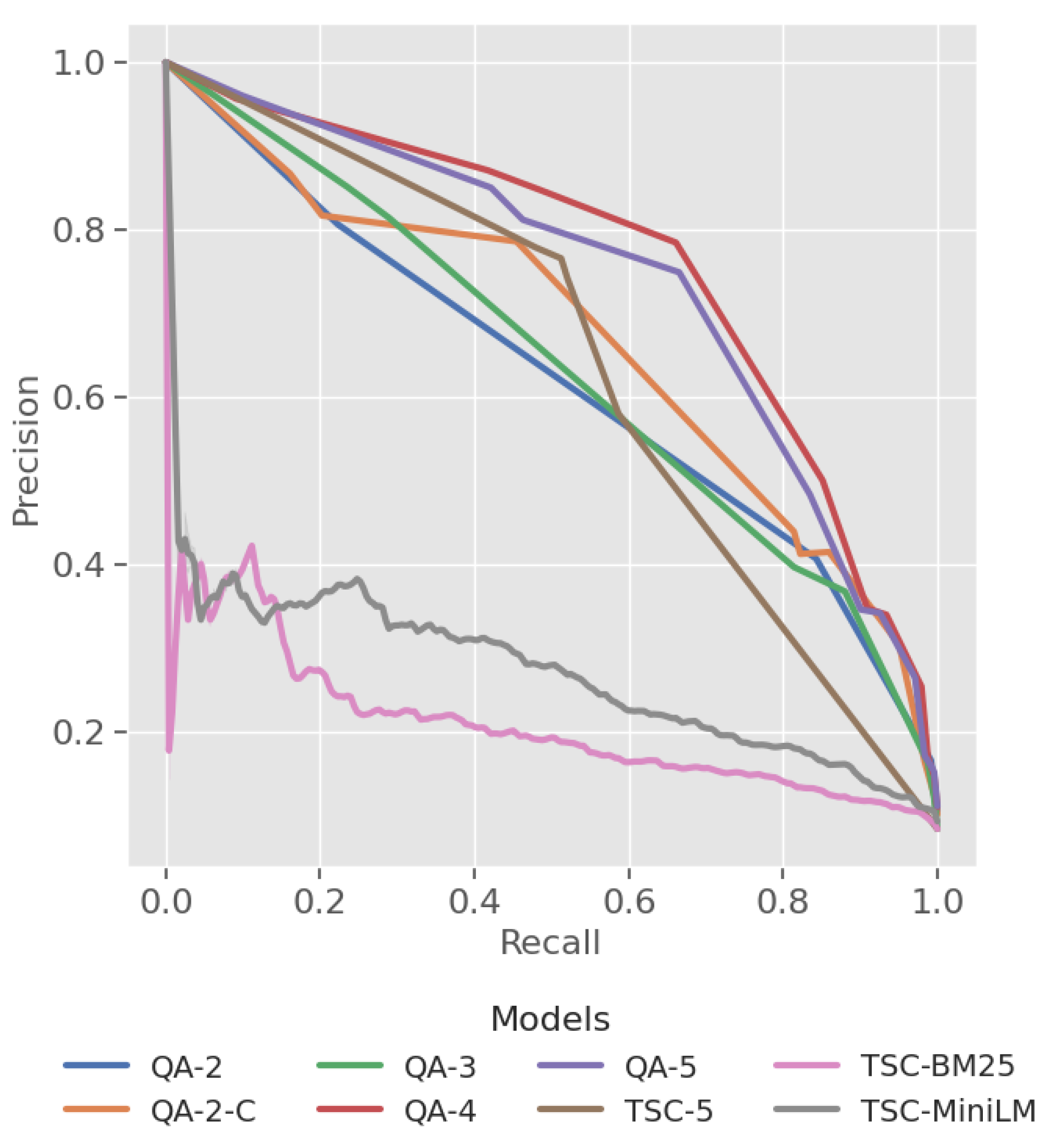

Average Precision (AP)

Mean Average Precision (MAP)

2.8. Experimental Setup

3. Results

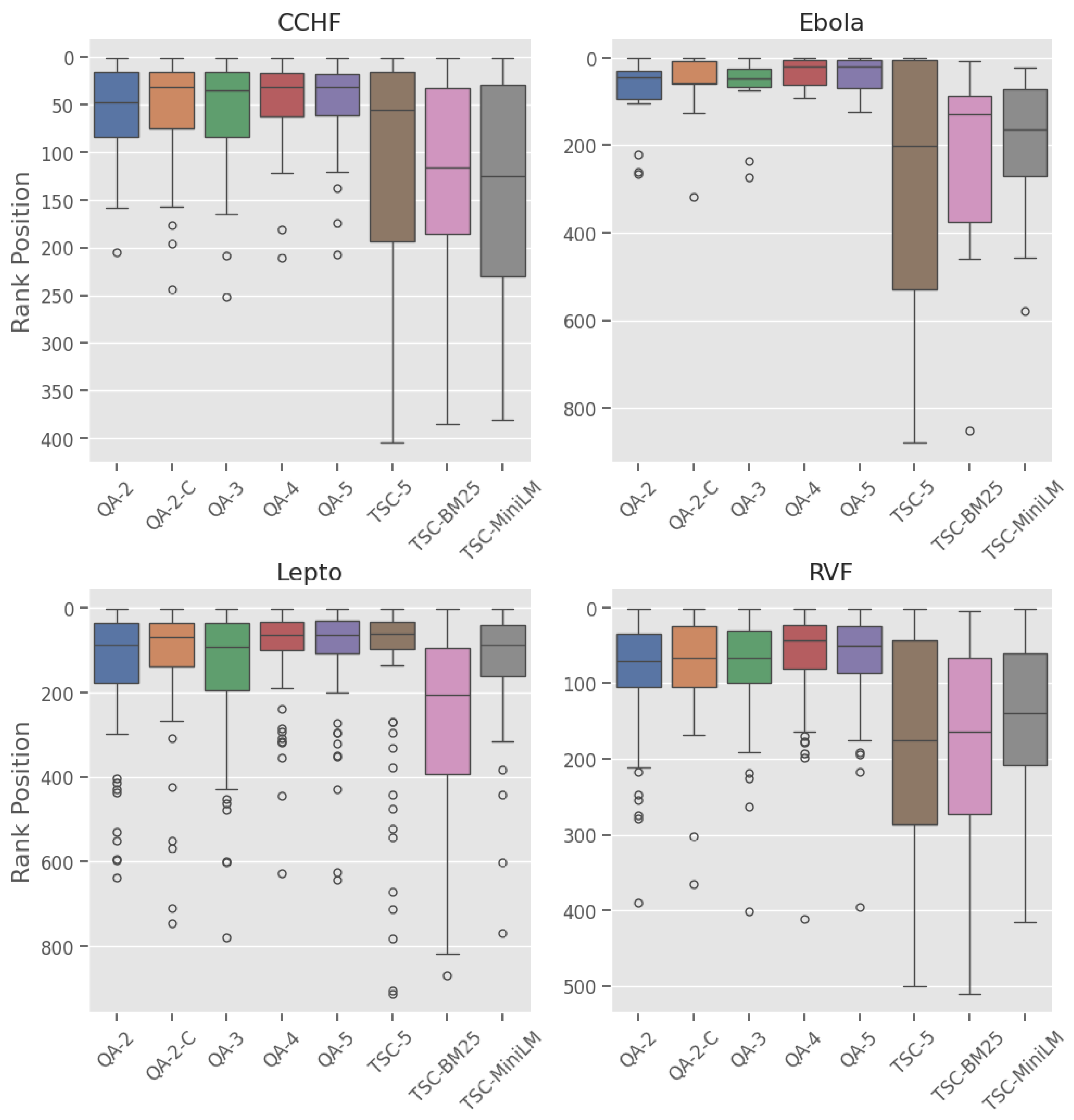

3.1. RQ1. LLM Based QA Assessor vs Baseline

3.2. RQ2. Effect of Label Granularity

3.3. RQ3. Performance Across Zoonotic Diseases

3.4. RQ4. Utility of Generated CoT Rationale

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| QA | Question and answer |

| CCHF | Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever |

| RVF | Rift valley fever |

Appendix A. Additional Prompts and Disease Information

| Disease |

|---|

| Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever |

| Ebolavirus |

| Henipah virus |

| Mammarenavirus |

| Marburg virus |

| MERS-CoV |

| Rift Valley Fever |

| SARS-CoV |

| Zika |

| Leptospirosis |

| Dengue |

References

- Ryan, S.J.; Lippi, C.A.; Caplan, T.; Diaz, A.; Dunbar, W.; Grover, S.; Johnson, S.; Knowles, R.; Lowe, R.; Mateen, B.A.; et al. The Current Landscape of Software Tools for the Climate-Sensitive Infectious Disease Modelling Community. The Lancet Planetary Health 2023, 7, e527–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.; Murray, K.A.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Morse, S.S.; Rondinini, C.; Di Marco, M.; Breit, N.; Olival, K.J.; Daszak, P. Global Hotspots and Correlates of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Mutua, F.K.; Ochungo, P.; Kruska, RL.; Jones, K.; Brierley, L.; Lapar, M.L.; Said, M.Y.; Herrero, M.T.; Phuc, PM.; et al. Mapping of Poverty and Likely Zoonoses Hotspots 2012.

- Gubbins, S.; Carpenter, S.; Mellor, P.; Baylis, M.; Wood, J. Assessing the Risk of Bluetongue to UK Livestock: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analyses of a Temperature-Dependent Model for the Basic Reproduction Number. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2008, 5, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guis, H.; Caminade, C.; Calvete, C.; Morse, A.P.; Tran, A.; Baylis, M. Modelling the Effects of Past and Future Climate on the Risk of Bluetongue Emergence in Europe. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2011, 9, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Higgins, J.P.T.; on evidence-based medicine) Li, T.W.; Page, M.J.; Thomas, J.P.o.S.R.a.P.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, second edition ed.; Cochrane Book Series, Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering 2007. 2.

- Tricco, A.C.; Brehaut, J.; Chen, M.H.; Moher, D. Following 411 Cochrane Protocols to Completion: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PloS One 2008, 3, e3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, M.; Reuter, K. The Significant Cost of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: A Call for Greater Involvement of Machine Learning to Assess the Promise of Clinical Trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 2019, 16, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Mutz, R. Growth Rates of Modern Science: A Latent Piecewise Growth Curve Approach to Model Publication Numbers from Established and New Literature Databases. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2021, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolo, P.D.B.; Pan, R.K.; Ghosh, R.; Huberman, B.A.; Kaski, K.; Fortunato, S. Attention Decay in Science 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Dunn, A.G. Time-to-Update of Systematic Reviews Relative to the Availability of New Evidence. Systematic Reviews 2018, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; McFarlane, C.; Cleo, G.; Ishikawa Ramos, C.; Marshall, S. The Impact of Systematic Review Automation Tools on Methodological Quality and Time Taken to Complete Systematic Review Tasks: Case Study. JMIR medical education 2021, 7, e24418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; McDonald, S.; Noel-Storr, A.; Shemilt, I.; Elliott, J.; Mavergames, C.; Marshall, I.J. Machine Learning Reduced Workload with Minimal Risk of Missing Studies: Development and Evaluation of a Randomized Controlled Trial Classifier for Cochrane Reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2021, 133, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafnat, G.; Glasziou, P.; Choong, M.K.; Dunn, A.; Galgani, F.; Coiera, E. Systematic Review Automation Technologies. Systematic Reviews 2014, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolanos, F.; Salatino, A.; Osborne, F.; Motta, E. Artificial Intelligence for Literature Reviews: Opportunities and Challenges 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Ameen, D.; Zarnegar, A. Tools to Support the Automation of Systematic Reviews: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2022, 144, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, Á.O.D.; Da Silva, E.S.; Couto, L.M.; Reis, G.V.L.; Belo, V.S. The Use of Artificial Intelligence for Automating or Semi-Automating Biomedical Literature Analyses: A Scoping Review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2023, 142, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, E.; Gupta, M.; Deng, J.; Park, Y.J.; Paget, M.; Naugler, C. Automated Paper Screening for Clinical Reviews Using Large Language Models: Data Analysis Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e48996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issaiy, M.; Ghanaati, H.; Kolahi, S.; Shakiba, M.; Jalali, A.; Zarei, D.; Kazemian, S.; Avanaki, M.; Firouznia, K. Methodological Insights into ChatGPT’s Screening Performance in Systematic Reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Sang, J.; Arora, R.; Kloosterman, R.; Cecere, M.; Gorla, J.; Saleh, R.; Chen, D.; Drennan, I.; Teja, B.; et al. Prompting Is All You Need: LLMs for Systematic Review Screening, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alshami, A.; Elsayed, M.; Ali, E.; Eltoukhy, A.E.E.; Zayed, T. Harnessing the Power of ChatGPT for Automating Systematic Review Process: Methodology, Case Study, Limitations, and Future Directions. Systems 2023, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Torres, J.P.; Mulligan, C.; Jorge, J.; Moreira, C. PROMPTHEUS: A Human-Centered Pipeline to Streamline Slrs with Llms. arXiv e-prints, 2410. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L.; Finnerty Mutlu, A.N.; Elmore, R.; Olorisade, B.K.; Thomas, J.; Higgins, J.P.T. Data Extraction Methods for Systematic Review (Semi)Automation: Update of a Living Systematic Review. F1000Research 2023, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak, M.P.; Morgan, D. Extracting Accurate Materials Data from Research Papers with Conversational Language Models and Prompt Engineering. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson Thomas, I.; Roche, P.; Grêt-Regamey, A. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Efficient Systematic Reviews: A Case Study in Ecosystem Condition Indicators. Ecological Informatics 2024, 83, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susnjak, T.; Hwang, P.; Reyes, N.H.; Barczak, A.L.C.; McIntosh, T.R.; Ranathunga, S. Automating Research Synthesis with Domain-Specific Large Language Model Fine-Tuning. 2024, [arXiv:cs/2404.08680]. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Yu, T.; Xu, Y.; Lee, N.; Ishii, E.; Fung, P. Towards Mitigating Hallucination in Large Language Models via Self-Reflection. 2023, [arXiv:cs/2310.06271]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, T.; Lehman, E.; Suzgun, M.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Celi, L.A.; Gichoya, J.; Jurafsky, D.; Szolovits, P.; Bates, D.W.; Abdulnour, R.E.E.; et al. Assessing the Potential of GPT-4 to Perpetuate Racial and Gender Biases in Health Care: A Model Evaluation Study. The Lancet Digital Health 2024, 6, e12–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Deng, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Du, M. Explainability for Large Language Models: A Survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 20:1–20:38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022; Vol. 35, pp. 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates,Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 9459–9474.

- Beller, E.; Clark, J.; Tsafnat, G.; Adams, C.; Diehl, H.; Lund, H.; Ouzzani, M.; Thayer, K.; Thomas, J.; Turner, T.; et al. Making Progress with the Automation of Systematic Reviews: Principles of the International Collaboration for the Automation of Systematic Reviews (ICASR). Systematic Reviews 2018, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.M.; Forbes, C.; Clark, J.; Carter, M.; Glasziou, P.; Munn, Z. Systematic Review Automation Tool Use by Systematic Reviewers, Health Technology Assessors and Clinical Guideline Developers: Tools Used, Abandoned, and Desired, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Polanin, J.R.; Pigott, T.D.; Espelage, D.L.; Grotpeter, J.K. Best Practice Guidelines for Abstract Screening Large-Evidence Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Research Synthesis Methods 2019, 10, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, M.; Tetzlaff, J.; Urquhart, C. Precision of Healthcare Systematic Review Searches in a Cross-sectional Sample. Research Synthesis Methods 2011, 2, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Scells, H.; Koopman, B.; Zuccon, G. Neural Rankers for Effective Screening Prioritisation in Medical Systematic Review Literature Search, 2022, [2212. 0 9017. [CrossRef]

- Mitrov, G.; Stanoev, B.; Gievska, S.; Mirceva, G.; Zdravevski, E. Combining Semantic Matching, Word Embeddings, Transformers, and LLMs for Enhanced Document Ranking: Application in Systematic Reviews. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, W.; E. Mendoza, O.; Samwald, M.; Knoth, P.; Hanbury, A. CSMeD: Bridging the Dataset Gap in Automated Citation Screening for Systematic Literature Reviews. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 23468–23484. [Google Scholar]

- Kohandel Gargari, O.; Mahmoudi, M.H.; Hajisafarali, M.; Samiee, R. Enhancing Title and Abstract Screening for Systematic Reviews with GPT-3.5 Turbo. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2024, 29, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Utsumi, T.; Aoki, Y.; Maruki, T.; Takeshima, M.; Takaesu, Y. Human-Comparable Sensitivity of Large Language Models in Identifying Eligible Studies Through Title and Abstract Screening: 3-Layer Strategy Using GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 for Systematic Reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e52758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanghera, R.; Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Khoury, M.E.; O’Logbon, J.; Chen, Y.; Watt, A.; Mahmood, M.; Butt, H.; Nishimura, G.; Soltan, A. High-Performance Automated Abstract Screening with Large Language Model Ensembles, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Scells, H.; Koopman, B.; Potthast, M.; Zuccon, G. Generating Natural Language Queries for More Effective Systematic Review Screening Prioritisation. In Proceedings of the SIGIR-AP 2023 - Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval in the Asia Pacific Region; 2023; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, R.; McAuley, J.; Zhao, W.X. Large Language Models Are Zero-Shot Rankers for Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the Advances in Information Retrieval; Goharian, N.; Tonellotto, N.; He, Y.; Lipani, A.; McDonald, G.; Macdonald, C.; Ounis, I., Eds., Cham; 2024; pp. 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Qin, Z.; Hui, K.; Wu, J.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Bendersky, M. Beyond Yes and No: Improving Zero-Shot LLM Rankers via Scoring Fine-Grained Relevance Labels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 2: Short Papers); Duh, K.; Gomez, H.; Bethard, S., Eds., Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 358–370. [CrossRef]

- Faggioli, G.; Dietz, L.; Clarke, C.L.A.; Demartini, G.; Hagen, M.; Hauff, C.; Kando, N.; Kanoulas, E.; Potthast, M.; Stein, B.; et al. Perspectives on Large Language Models for Relevance Judgment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGIR International Conference on Theory of Information Retrieval, New York, NY, USA, 2023; ICTIR’23,pp.39–50. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, H.; Shen, T.; Qin, C.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Q.; et al. A Survey on Large Language Models for Recommendation. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Spielman, S.; Craswell, N.; Mitra, B. Large Language Models Can Accurately Predict Searcher Preferences. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, New York, NY, USA, 2024; SIGIR’24, pp. 1930–1940. [CrossRef]

- Syriani, E.; David, I.; Kumar, G. Screening Articles for Systematic Reviews with ChatGPT. Journal of Computer Languages 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners, 2020, [2005.14165]. 1 4165. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Singh, A.K.; Saha, S.; Jain, V.; Mondal, S.; Chadha, A. A Systematic Survey of Prompt Engineering in Large Language Models: Techniques and Applications 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Tinn, R.; Cheng, H.; Lucas, M.; Usuyama, N.; Liu, X.; Naumann, T.; Gao, J.; Poon, H. Domain-Specific Language Model Pretraining for Biomedical Natural Language Processing. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthcare 2021, 3, 2:1–2:23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotala, A.; Kuutila, M.; Ralph, P.; Mäntylä, M. The Promise and Challenges of Using LLMs to Accelerate the Screening Process of Systematic Reviews. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large Language Models Are Zero-Shot Reasoners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024.

- Tseng, Y.M.; Huang, Y.C.; Hsiao, T.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Huang, C.W.; Meng, Y.; Chen, Y.N. Two Tales of Persona in LLMs: A Survey of Role-Playing and Personalization. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA; 2024; pp. 16612–16631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Nassereldine, A.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Kumar, U.; Lee, C.; Qin, R.; Shi, Y.; et al. Large Language Models Have Intrinsic Self-Correction Ability. 2024, [arXiv:cs/2406.15673]. [CrossRef]

- Spillias, S.; Tuohy, P.; Andreotta, M.; Annand-Jones, R.; Boschetti, F.; Cvitanovic, C.; Duggan, J.; Fulton, E.; Karcher, D.; Paris, C.; et al. Human-AI Collaboration to Identify Literature for Evidence Synthesis, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Zaragoza, H. The Probabilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Dong, L.; Bao, H.; Yang, N.; Zhou, M. MINILM: Deep Self-Attention Distillation for Task-Agnostic Compression of Pre-Trained Transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020, Vol. 2020-December.

- SentenceTransformers Documentation — Sentence Transformers Documentation. https://www.sbert.net/.

- OpenAI Platform. https://platform.openai.com.

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, England, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kusa, W.; Lipani, A.; Knoth, P.; Hanbury, A. An Analysis of Work Saved over Sampling in the Evaluation of Automated Citation Screening in Systematic Literature Reviews. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2023/05/01/May 2023///, 18. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Huang, T.; Sun, F.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H. Automated Medical Literature Screening Using Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2022, 29, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoulas, E.; Li, D.; Azzopardi, L.; Spijker, R. CLEF 2017 Technologically Assisted Reviews in Empirical Medicine Overview. In Proceedings of the Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akinseloyin, O.; Jiang, X.; Palade, V. A Question-Answering Framework for Automated Abstract Screening Using Large Language Models. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, p. ocae166. [CrossRef]

- Linzbach, S.; Tressel, T.; Kallmeyer, L.; Dietze, S.; Jabeen, H. Decoding Prompt Syntax: Analysing Its Impact on Knowledge Retrieval in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, New York, NY, USA, 2023; WWW’23 Companion, pp. 1145–1149. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Disease | Climate Variable | Relevant | Irrelevant | Total | % Relevant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCHF | Rainfall | 57 | 398 | 454 | 12.6% |

| Ebola | Rainfall | 14 | 902 | 915 | 1.5% |

| Lepto | Rainfall | 108 | 890 | 999 | 10.8% |

| RVF | Rainfall | 63 | 474 | 537 | 11.7% |

| Disease | Topic and Eligibility Questions |

|---|---|

| CCHF |

Topic: Impact of Climate Change on CCHF: A Focus on Rainfall Eligibility Questions: Q1. Does the study report on primary research or a meta-analysis rather than a review, opinion, or book? Q2. Does the study measure the incidence or prevalence or virulence or survival or transmission of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever or a relevant vector (such as ticks) without specifically measuring the incidence of the pathogens? Q3. Does the research examine environmental factors such as rainfall, seasonality (e.g., wet vs. dry season) or regional comparisons impacting disease prevalence or vector distribution? Q4. Is the study focused on field-based or epidemiological research rather than laboratory method validation? |

| Ebola |

Topic: Impact of Climate Change on Ebola: A Focus on Rainfall Eligibility Questions: Q1. Does the study report on primary research or a meta-analysis rather than a review, opinion, or book? Q2. Does the study measure the incidence or prevalence or virulence or survival or transmission of Ebola or Marburg, a relevant vector, or reservoir hosts abundance or distribution (such as bats or primates) without specifically measuring the incidence of the pathogens? Q3. Does the research examine environmental factors such as rainfall, seasonality (e.g., wet vs. dry season) or regional comparisons impacting disease prevalence or vector distribution? Q4. Is the study focused on field-based or epidemiological research rather than laboratory method validation? |

| Lepto |

Topic: Impact of Climate Change on Leptospirosis: A Focus on Rainfall Eligibility Questions: Q1. Does the study report on primary research or a meta-analysis rather than a review, opinion, or book? Q2. Does the study measure the incidence or prevalence or virulence or survival or transmission of Leptospirosis, a relevant arthropod vector, or reservoir hosts (such as rodents) without specifically measuring the incidence of the pathogens? Q3. Does the research examine environmental factors such as rainfall, seasonality (e.g., wet vs. dry season) or regional comparisons impacting disease prevalence or vector distribution? Q4. Is the study focused on field-based or epidemiological research rather than laboratory method validation? |

| RVF |

Topic: Impact of Climate Change on Rift Valley Fever Virus: A Focus on Rainfall Eligibility Questions: Q1. Does the study report on primary research or a meta-analysis rather than a review, opinion, or book? Q2. Does the study measure the incidence or prevalence or virulence or survival or transmission of Rift Valley fever or other vector-borne diseases (such as malaria) that share similar vectors (e.g., mosquitoes) without specifically measuring the incidence of the pathogen? Q3. Does the research examine environmental factors such as rainfall, seasonality (e.g., wet vs. dry season) or regional comparisons impacting disease prevalence or vector distribution? Q4. Is the study focused on field-based or epidemiological research rather than laboratory method validation? |

| Answer Schema | Answer Labels | Answer Score |

|---|---|---|

| QA-2 | Yes | 1.0 |

| No | 0.0 | |

| QA-3 | Yes | 1.00 |

| Unsure | 0.50 | |

| No | 0.00 | |

| QA-4 | Definitely Yes | 0.95 |

| Probably Yes | 0.75 | |

| Probably No | 0.25 | |

| Definitely No | 0.05 | |

| QA-5 | Definitely Yes | 1.00 |

| Probably Yes | 0.75 | |

| Unsure | 0.50 | |

| Probably No | 0.25 | |

| Definitely No | 0.00 | |

| TSC-5 | Definitely Include | 1.00 |

| Probably Include | 0.75 | |

| Unsure | 0.50 | |

| Probably Exclude | 0.25 | |

| Definitely Exclude | 0.00 |

| Answer Schema | Answer Labels | Confidence Labels | Confidence Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| QA-2-C | Yes | High | 1.00 |

| Medium | 0.75 | ||

| Low | 0.50 | ||

| No | High | 0.00 | |

| Medium | 0.25 | ||

| Low | 0.50 |

| Model | MAP | PR-AUC |

|---|---|---|

| QA-2 | 0.476 | 0.621 |

| QA-2-C | 0.579 | 0.669 |

| QA-3 | 0.519 | 0.636 |

| QA-4 | 0.691 | 0.761 |

| QA-5 | 0.670 | 0.740 |

| TSC-5 | 0.489 | 0.639 |

| TSC-BM25 | 0.229 | 0.206 |

| TSC-MiniLM | 0.325 | 0.271 |

| Disease | Revised to include | Revised to exclude | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCHF | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Ebola | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Lepto | 13 | 3 | 16 |

| RVF | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Disease | Model | Recall@k% | nWSS@r% | AP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 95 | 100 | |||

| CCHF | QA-2 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.70 |

| QA-2-C | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.77 | |

| QA-3 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.76 | |

| QA-4 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.80 | |

| QA-5 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.78 | |

| TSC-5 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.55 | |

| TSC-BM25 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.40 | |

| TSC-MiniLM | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.38 | |

| Ebola | QA-2 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.18 |

| QA-2-C | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.33 | |

| QA-3 | 0.43 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.23 | |

| QA-4 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.51 | |

| QA-5 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.50 | |

| TSC-5 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.71 | -0.01 | 0.04 | 0.37 | |

| TSC-BM25 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |

| TSC-MiniLM | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.04 | |

| Lepto | QA-2 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| QA-2-C | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.69 | |

| QA-3 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.57 | |

| QA-4 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.42 | 0.80 | |

| QA-5 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.78 | |

| TSC-5 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.75 | |

| TSC-BM25 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.26 | |

| TSC-MiniLM | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.62 | |

| RVF | QA-2 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.44 |

| QA-2-C | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.36 | 0.53 | |

| QA-3 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.51 | |

| QA-4 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.66 | |

| QA-5 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.61 | |

| TSC-5 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.28 | |

| TSC-BM25 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.21 | |

| TSC-MiniLM | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).