Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

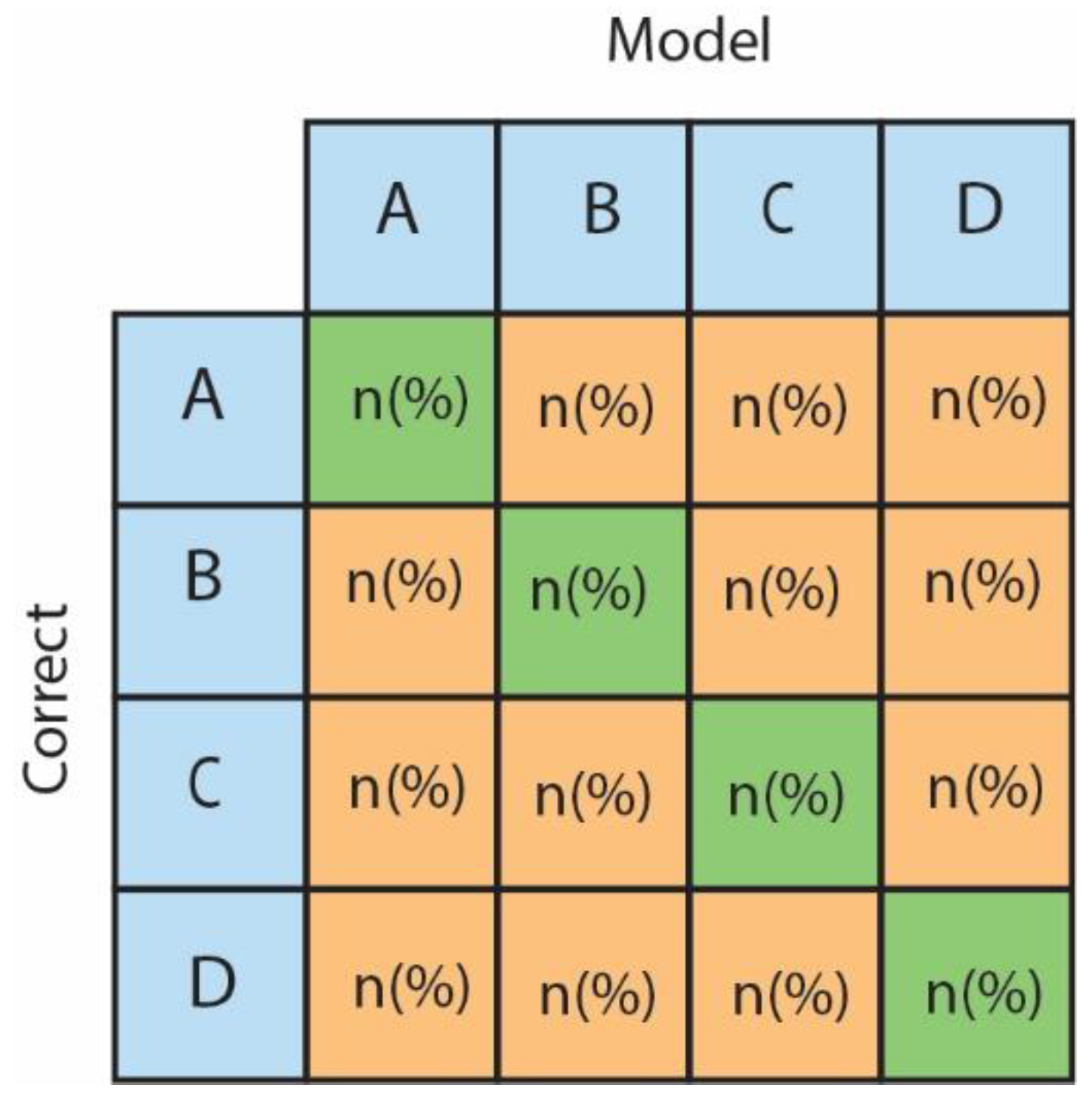

Large language models (LLMs) have increasingly been recognized for their potential to revolutionize various aspects of healthcare, including diagnosis and treatment planning. However, the complexity of evaluating these models, particularly in the medical domain, has led to a lack of standardization in assessment methodologies. This study, conducted by the Farzan Clinical Research Institute, aims to establish a standardized evaluation framework for medical LLMs by proposing specific checklists for multiple-choice questions (MCQs), question-answering tasks, and case scenarios. The study demonstrates that MCQs provide a straightforward means to assess model accuracy, while the proposed confusion matrix helps identify potential biases in model choice. For question-answering tasks, the study emphasizes the importance of evaluating dimensions like relevancy, similarity, coherence, fluency, and factuality, ensuring that LLM responses meet clinical expectations. In case scenarios, the dual focus on accuracy and reasoning allows for a nuanced understanding of LLMs' diagnostic processes. The study also highlights the importance of model coverage, reproducibility, and the need for tailored evaluation methods to match study characteristics. The proposed checklists and methodologies aim to facilitate consistent and reliable assessments of LLM performance in medical tasks, paving the way for their integration into clinical practice. Future research should refine these methods and explore their application in real-world settings to enhance the utility of LLMs in medicine.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Linguistic Analysis

2.1. Passage Ranking

2.2. Semantic Textual Similarity

2.2.1. Word Embeddings

2.2.2. Contextualized Embeddings

2.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

- 2 .Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient [16,18]: Assesses the monotonic relationship between the predicted scores and the ground truth scores, comparing the rank orders rather than the raw values.

2.3. Cosine Similarity

2.4. Rouge Score

- 1 .ROUGE-N: ROUGE-N measures the overlap of n-grams between the candidate text and the reference text. Common values are ROUGE-1 (unigrams), ROUGE-2 (bigrams), and ROUGE-3 (trigrams).

- Example: If the reference text contains ”the cat sat on the mat” and the generated text contains ”the cat is on the mat”, the ROUGE-1 score would be calculated based on the overlap of unigrams like ”the”, ”cat”, ”on”, and ”mat”.

- 2 .ROUGE-L: ROUGE-L measures the longest common subsequence (LCS) between the candidate and reference summaries. It takes into account sentence-level structure similarity.

- Example: For the reference summary ”the cat sat on the mat” and the candidate summary ”the cat is on the mat”, the LCS would be ”the cat on the mat”.

- 3 .ROUGE-W: ROUGE-W is a weighted version of ROUGE-L that gives more importance to consecutive matches than to non-consecutive matches.

- Example: If the reference summary is ”the cat sat on the mat” and the candidate summary is ”the cat sat quickly on the mat”, ROUGE-W will score the consecutive ”the cat sat on the mat” higher than non-consecutive matches.

- 4 .ROUGE-S: ROUGE-S, or ROUGE-Skip-Bigram, considers skip-bigram matches between the candidate and reference summaries. Skip-bigrams are any pair of words in their order of appearance, allowing for gaps.

- Example: For the reference summary ”the cat sat on the mat” and the candidate summary ”the cat on mat”, the skip-bigrams like ”the on”, ”cat mat” will be considered.

2.4.1. Calculation of ROUGE Scores

- - Recall:

- - Precision:

- F1-Score:

- ROUGE-1 (unigram): Count overlaps like ”the”, ”cat”, ”on”, and ”mat”.

- ROUGE-2 (bigram): Count overlaps like ”the cat”, ”on the”, and ”the mat”.

- ROUGE-L: Identify the longest common subsequence ”the cat on the mat”.

- ROUGE-S: Consider skip-bigrams like ”the on”, ”cat mat”.

3. Human Evaluation

3.1. Multiple Choice Questions

3.2. Question-Answers

- Relevancy: Defined as models' ability to properly understand the question and provide relevant response regardless of answers correctness

- Similarity: by similarity we aim to compare model's response to ground truth or expected answer. This test could also be used in case models is fine-tuned on question-and-answer dataset and the aim is to compare model's response to the response available in fine tuning dataset.

- Coherence: this domain aims to check whether response follows a logical flow with an introduction, body and conclusion.

- Fluency: assesses whether answers are linguistically fluent and easy to understand.

- Factuality: at this domain the aim is to compare model's response to reliable scientific resources.

3.3. Case Scenarios

4. Discussion and Conclusion

References

- Gargari, O.K. et al., Enhancing title and abstract screening for systematic reviews with GPT-3.5 turbo. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2024, 29, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, D. et al., Accuracy of ChatGPT generated diagnosis from patient's medical history and imaging findings in neuroradiology cases. Neuroradiology 2024, 66, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, K. , Rouge 2.0: Updated and improved measures for evaluation of summarization tasks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01937. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z. et al., Evaluating large language models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.19736. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. et al., Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S. et al., TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. Bmj 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D. et al., What disease does this patient have? a large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q., et al. PubMedQA: A Dataset for Biomedical Research Question Answering. 2019. Hong Kong, China: Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Pal, A., L.K. Umapathi, and M. Sankarasubbu, MedMCQA: A Large-scale Multi-Subject Multi-Choice Dataset for Medical domain Question Answering, in Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, F. Gerardo, et al., Editors. 2022, PMLR: Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 248–260.

- Brin, D. et al., Comparing ChatGPT and GPT-4 performance in USMLE soft skill assessments. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 16492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barile, J. et al., Diagnostic Accuracy of a Large Language Model in Pediatric Case Studies. JAMA Pediatr 2024, 178, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duey, A.H. et al., Thromboembolic prophylaxis in spine surgery: an analysis of ChatGPT recommendations. Spine J 2023, 23, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taira, K., T. Itaya, and A. Hanada, Performance of the Large Language Model ChatGPT on the National Nurse Examinations in Japan: Evaluation Study. JMIR Nurs 2023, 6, e47305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, T.H. et al., Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M. et al., Evaluating the Feasibility of ChatGPT in Healthcare: An Analysis of Multiple Clinical and Research Scenarios. J Med Syst 2023, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, Y.H. et al., Assessing the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023, 29, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, C.E. et al., Let's chat about cervical cancer: Assessing the accuracy of ChatGPT responses to cervical cancer questions. Gynecol Oncol 2023, 179, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Description | Reference |

| MedQA | collected from the professional medical board exams. It covers three languages: English, simplified Chinese, and traditional Chinese, and contains 12,723, 34,251, and 14,123 questions for the three languages | [7] |

| PubmedQA | Collected from PubMed abstracts. The task of PubMedQA is to answer research questions with yes/no/maybe. PubMedQA has 1k expert-annotated, 61.2k unlabeled and 211.3k artificially generated QA instances | [8] |

| MedMCQA | MedMCQA has More than 194k high-quality AIIMS & NEET PG entrance exam MCQs covering 2.4k healthcare topics and 21 medical subjects are collected with an average token length of 12.77 and high topical diversity. | [9] |

| N | Question |

| 1 | The number of questions in which the correct option is selected and reasoning is in line with model's choice |

| 2 | The number of questions in which the correct option is mentioned in the description, but no option is not selected |

| 3 | The number of questions in which the correct option is mentioned in the description, but the chosen option is different. |

| 4 | The number of questions in which the correct option is selected but description does not provide robust reasoning. |

| 5 | Incorrect choice and reasoning |

| Relevancy | |

|---|---|

| 1 | In how many questions was the answer related to the question regardless of the correctness? |

| Similarity | |

| 1 | The points in the ground truth have been mentioned and also some correct additional items have been added to it. |

| 2 | The points in the ground truth have been mentioned |

| 3 | The key points are incompletely mentioned |

| 4 | The key points are not mentioned |

| Coherence | |

| 1 | In how many questions does the model address additional and irrelevant details? |

| 2 | In how many questions does the tone remain constant during the answer? |

| 3 | In how many questions are ironies and non-scientific literature used during the answer? |

| 4 | In some questions, the structure of the answer is logical (introduction, body and clear conclusion). |

| Fluency | |

| 1 | How many answers were understood in one reading? |

| 2 | How many answers do you think were fluent? |

| 3 | How many answers included repeating items? |

| 4 | In how many questions are punctuation marks used correctly? |

| 5 | In how many questions are words from other languages used inappropriately? |

| 6 | In how many questions is the length of sentences and paragraphs appropriate? |

| Factuality | |

| 1 | The number of questions that have incorrect scientific information. (compared with reliable sources) |

| Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | Question | Mark |

| 1 | Correct diagnosis | 3 Points |

| 2 | Correct diagnosis of the disease without mentioning details | 2 Points |

| 3 | Correct diagnosis of the general category of the disease | 1 Point |

| 4 | Incorrect diagnosis | 0 Point |

| Reasoning | ||

| 1 | The reasoning includes all the important and diagnostic signs and symptoms of the case and points to the correct signs outside the case. | 4 Points |

| 2 | The reasoning includes all the important and diagnostic signs and symptoms of the case | 3 Points |

| 3 | The reasoning considers most of the symptoms of the case | 2 Points |

| 4 | The reasoning does not consider most of the symptoms of the case | 1 Point |

| 5 | Incorrect reasoning | 0 Point |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).