Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Rationale

- Population (P): Adult periodontitis patients (≥18 years old) with at least one intrabony or furcation defect.

- Intervention (I): Periodontal regenerative surgical procedures using EMD combined with bone grafts (EMD+BG).

- Comparison (C): Periodontal regenerative surgical procedures using bone grafts alone (BG).

- Outcomes (O): CAL gain, PD reduction (primary); secondary outcomes included pocket closure, wound healing, gingival recession (REC), tooth loss, PROMs, and adverse events.

- Study Design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), parallel or split-mouth, with ≥10 patients per arm.

- Follow-up: Minimum 6 months after the surgical procedure.

- Population: Adult periodontitis patients (≥18 years) with intrabony or furcation defects.

- Intervention: EMD + BG (i.e., Emdogain combined with any bone graft material).

- Comparison: BG alone.

- Outcomes: At least CAL gain and PD reduction.

- Studies focusing exclusively on children (<18 years).

- Studies without a clear mention of EMD or bone grafts.

- Follow-up period <6 months or uncertain.

- Non-randomized studies or fewer than 10 patients per arm.

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.3. Data Pre-Processing

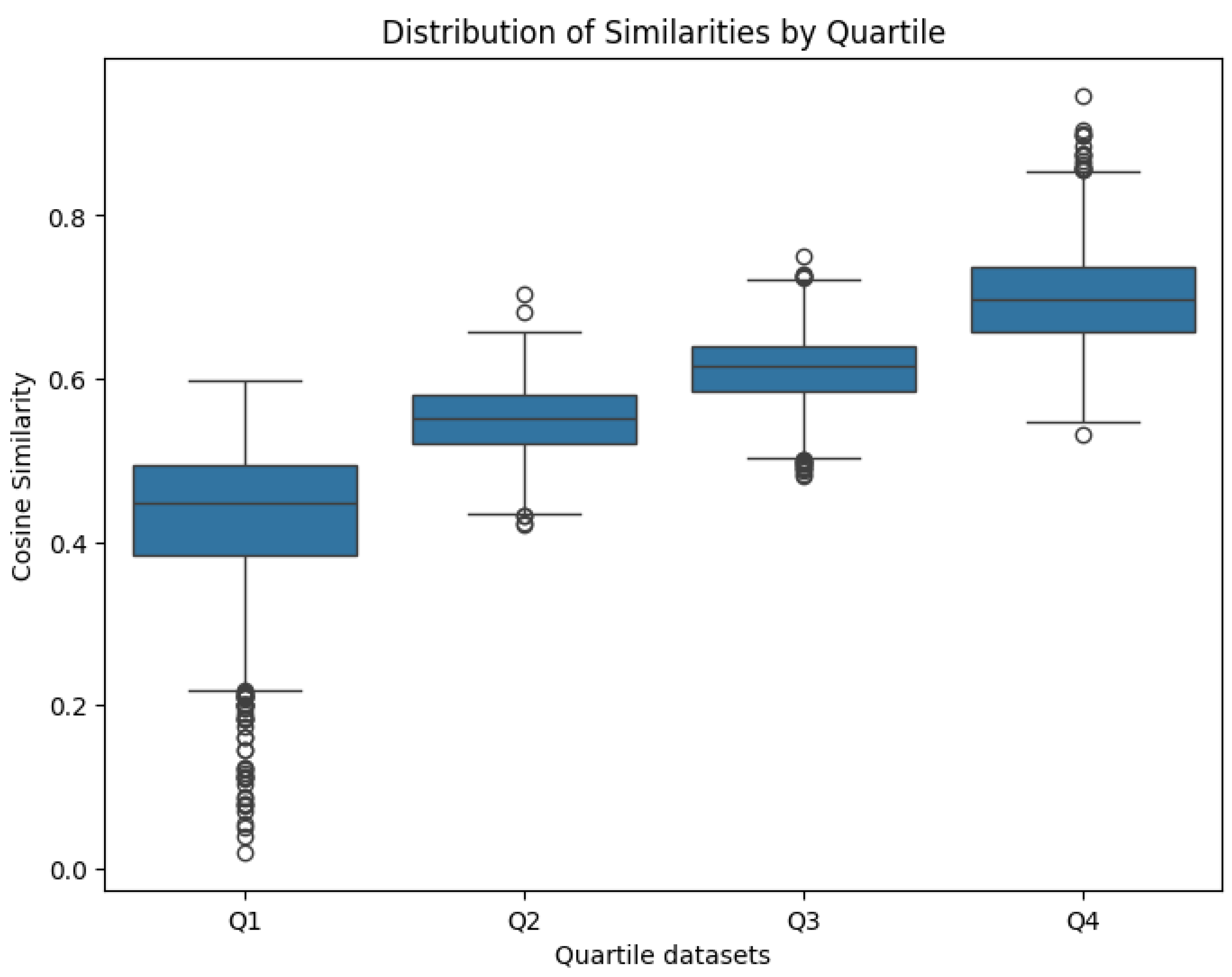

- Q1: Lowest similarity, with mean = 0.47

- Q2: Lower-mid similarity, with mean = 0.60

- Q3: Higher-mid similarity, with mean = 0.66

- Q4: Highest similarity, with mean = 0.76

- Q1: Mean similarity = 0.43 (range= 0.02-0.60)

- Q2: Mean similarity = 0.55 (range=0.42-0.70)

- Q3: Mean similarity = 0.61 (range=0.48-0.75)

- Q4: Mean similarity = 0.76 (range=0.53-0.94)

2.4. LLM-Based Classification

- OpenHermes: OpenHermes is an instruction-tuned language model based on the Mistral 7B architecture (7 billion parameters), designed for effective natural language understanding and generation across a wide range of tasks [37]. For this study, we employed the quantized version of OpenHermes-2.5-Mistral-7B-GGUF (openhermes-2.5-mistral-7b.Q4_K_M.gguf), freely available on Huggingface.com. Quantization reduced the model’s 32-bit parameters to 4-bit values, significantly improving computational efficiency while maintaining high performance.

- Flan T5: Flan-T5 is an instruction-tuned language model developed by Google, designed for general-purpose natural language understanding and generation tasks [38]. Flan-T5 was fine-tuned on a wide array of instruction-following datasets, and optimized for handling tasks such as classification, summarization, and question answering with high accuracy and contextual awareness.

- GPT-2: GPT-2, developed by OpenAI, lacks the instruction-tuning and domain-specific optimization of more advanced models, but it remains a valuable baseline for understanding the capabilities of earlier-generation language models [39].

- GPT-3.5 Turbo: GPT-3.5 Turbo, also developed by OpenAI, is an optimized and cost-efficient version of the GPT-3.5 model, providing robust natural language understanding and generation capabilities [40]. With significantly improved contextual reasoning and instruction-following compared to GPT-2, GPT-3.5 Turbo performs better in structured classification tasks. In this study, GPT-3.5 Turbo was utilized via OpenAI’s API.

- GPT-4o: GPT-4o is the optimized version of GPT-4, and it combines enhanced instruction-following capabilities with improved contextual understanding [41]. GPT-4o performs better in complex decision-making and classification scenarios than its predecessors. GPT-4o was accessed via OpenAI’s API too.

2.5. Performance Evaluation

- True Positives (TP): Correctly accepted relevant articles.

- False Negatives (FN): Relevant articles the model rejected.

- False Positives (FP): Irrelevant articles the model accepted.

- True Negatives (TN): Correctly rejected irrelevant articles.

2.6. Software and Hardware

3. Results

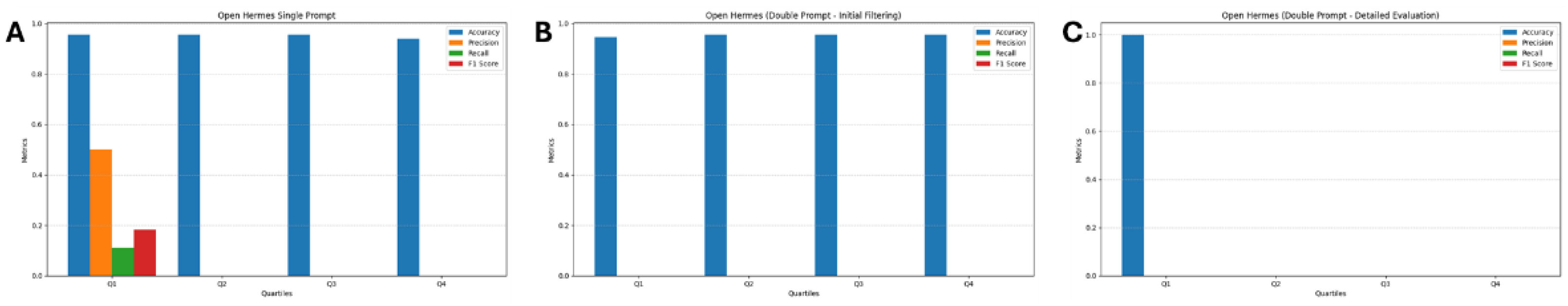

3.1. Open Hermes

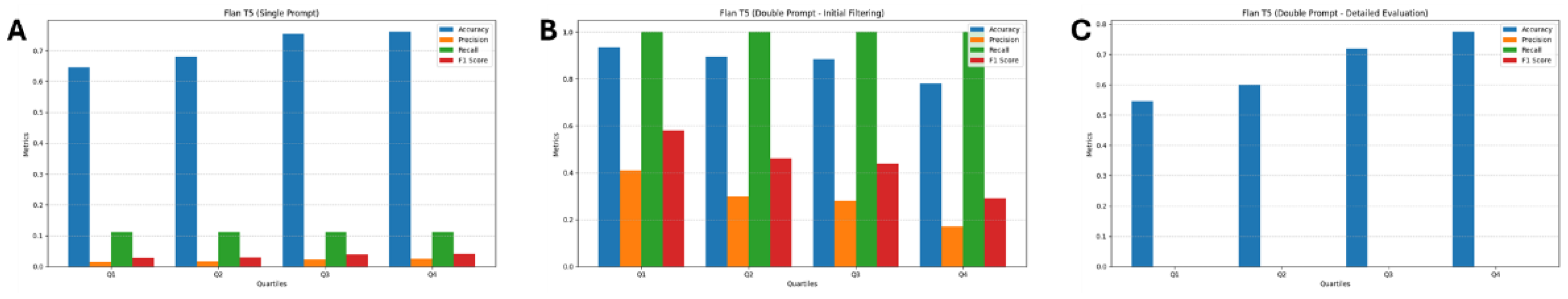

3.2. Flan T5

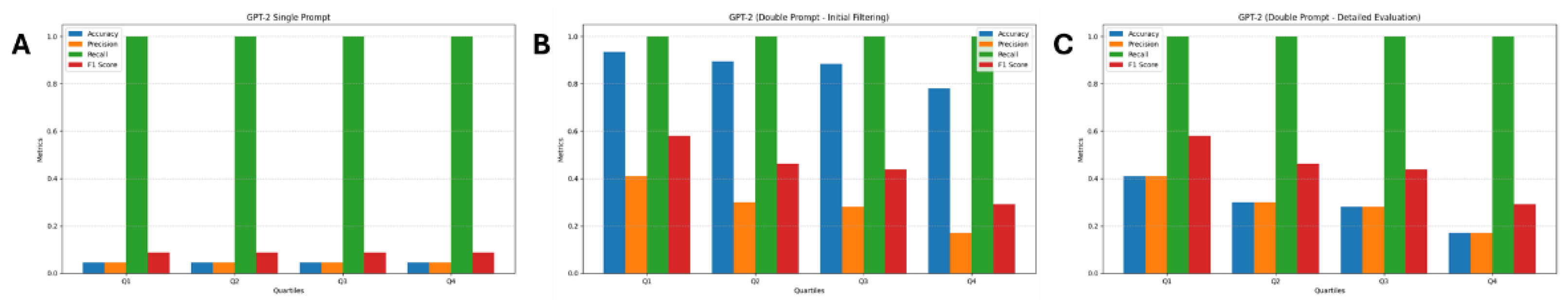

3.3. GPT-2

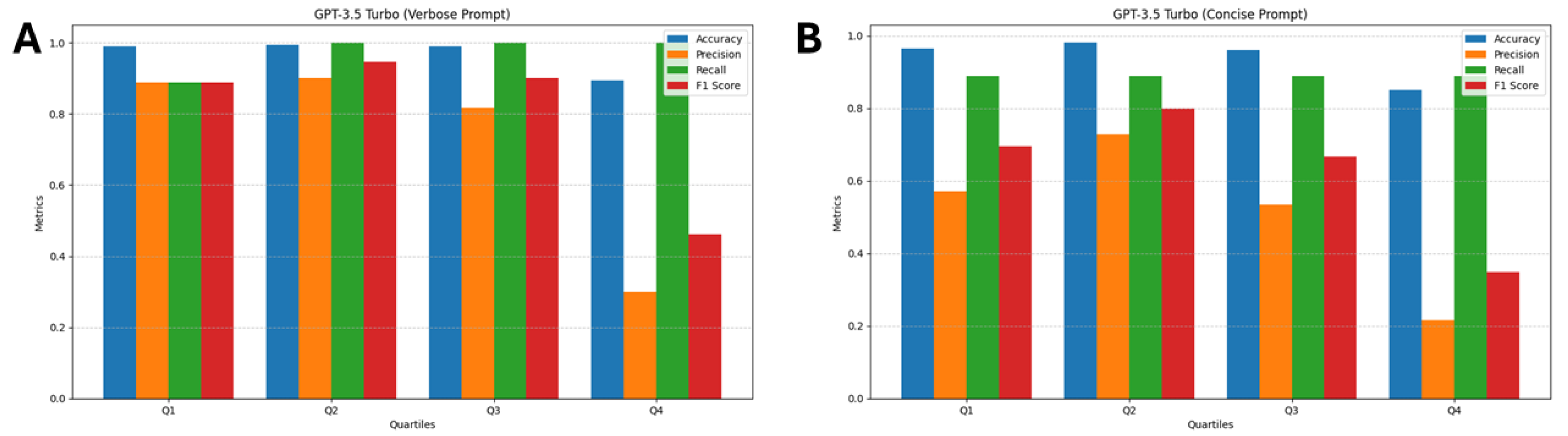

3.4. GPT-3.5 turbo

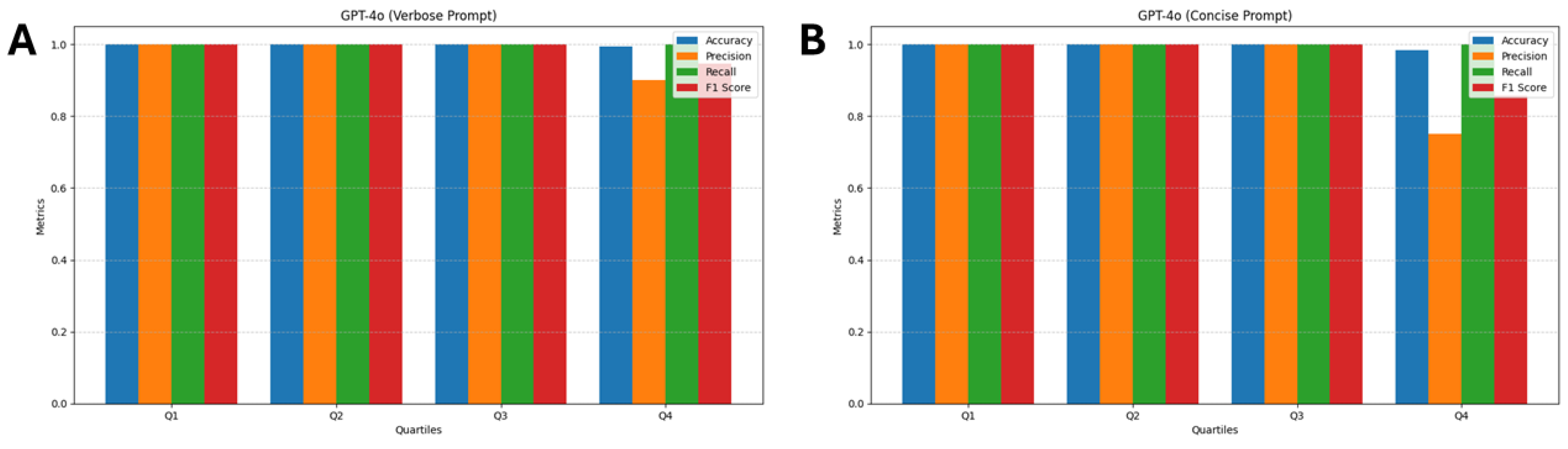

3.4. GPT-4o

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulrow, C.D. Systematic Reviews: Rationale for Systematic Reviews. BMJ 1994, 309, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betrán, A.P.; Say, L.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Allen, T.; Hampson, L. Effectiveness of Different Databases in Identifying Studies for Systematic Reviews: Experience from the WHO Systematic Review of Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivell, L. Mining the Bibliome: Searching for a Needle in a Haystack? EMBO Rep 2002, 3, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landhuis, E. Scientific Literature: Information Overload. Nature 2016, 535, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 5.Scells, H.; Zuccon, G.; Koopman, B.; Deacon, A.; Azzopardi, L.; Geva, S. Integrating the Framing of Clinical Questions via PICO into the Retrieval of Medical Literature for Systematic Reviews. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; ACM: New York, NY, USA, November 6 2017; pp. 2291–2294.

- Anderson, N.K.; Jayaratne, Y.S.N. Methodological Challenges When Performing a Systematic Review. The European Journal of Orthodontics 2015, 37, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennstädt, F.; Zink, J.; Putora, P.M.; Hastings, J.; Cihoric, N. Title and Abstract Screening for Literature Reviews Using Large Language Models: An Exploratory Study in the Biomedical Domain. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisha, Q.; Put, S.; Kappenberg, J.; Warraitch, A.; Hadfield, K. Can Large Language Models Replace Humans in Systematic Reviews? Evaluating <scp>GPT</Scp> -4’s Efficacy in Screening and Extracting Data from Peer-reviewed and Grey Literature in Multiple Languages. Res Synth Methods 2024, 15, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.-Y.; Shen, C.; Ji, Y.-L.; Li, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.-Q. Accuracy of Large Language Models for Literature Screening in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2024.

- Delgado-Chaves, F.M.; Jennings, M.J.; Atalaia, A.; Wolff, J.; Horvath, R.; Mamdouh, Z.M.; Baumbach, J.; Baumbach, L. Transforming Literature Screening: The Emerging Role of Large Language Models in Systematic Reviews. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakov, D.; Hubig, N.; Jansari, V.; Bakumenko, A.; Lenert, L.A. The Emergence of Large Language Models (LLM) as a Tool in Literature Reviews: An LLM Automated Systematic Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.04600. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.H.; Synnot, A.; Turner, T.; Simmonds, M.; Akl, E.A.; McDonald, S.; Salanti, G.; Meerpohl, J.; MacLehose, H.; Hilton, J.; et al. Living Systematic Review: 1. Introduction—the Why, What, When, and How. J Clin Epidemiol 2017, 91, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Fok, M.R.; Zhang, Y.; Han, B.; Lin, Y. The Role of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as Adjuncts to Periodontal Treatment and in Periodontal Regeneration. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mijiritsky, E.; Assaf, H.D.; Peleg, O.; Shacham, M.; Cerroni, L.; Mangani, L. Use of PRP, PRF and CGF in Periodontal Regeneration and Facial Rejuvenation—A Narrative Review. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, R.J.; Moraschini, V.; Estrin, N.E.; Shibli, J.A.; Cosgarea, R.; Jepsen, K.; Jervøe-Storm, P.; Sculean, A.; Jepsen, S. Periodontal Regeneration Using Platelet-rich Fibrin. Furcation Defects: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Periodontol 2000 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, H.N.; Cho, Y.J.; Tarafder, S.; Lee, C.H. The Recent Advances in Scaffolds for Integrated Periodontal Regeneration. Bioact Mater 2021, 6, 3328–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidan, I.; Labreuche, J.; Huck, O.; Agossa, K. Combination of Enamel Matrix Derivatives with Bone Graft vs Bone Graft Alone in the Treatment of Periodontal Intrabony and Furcation Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Health Prev Dent 2024, 22, 655–664. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-Bert: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese Bert-Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. [Google Scholar]

- Stankevičius, L.; Lukoševičius, M. Extracting Sentence Embeddings from Pretrained Transformer Models. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, L. Distance Weighted Cosine Similarity Measure for Text Classification. In; 2013; pp. 611–618.

- Cichosz, P. Assessing the Quality of Classification Models: Performance Measures and Evaluation Procedures. Open Engineering 2011, 1, 132–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, J.A.; Heller, N.C.; Ebsch, C.L.; Deshmukh, R.; Mackey, P.; Chin, G. Evaluation of Alignment: Precision, Recall, Weighting and Limitations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); IEEE, December 10 2020; pp. 2513–2519.

- Abbade, L.P.F.; Wang, M.; Sriganesh, K.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Thabane, L. Framing of Research Question Using the PICOT Format in Randomised Controlled Trials of Venous Ulcer Disease: A Protocol for a Systematic Survey of the Literature. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyer, E.T.; Velasquez-Plata, D.; Brunsvold, M.A.; Lasho, D.J.; Mellonig, J.T. A Clinical Comparison of a Bovine-Derived Xenograft Used Alone and in Combination with Enamel Matrix Derivative for the Treatment of Periodontal Osseous Defects in Humans. J Periodontol 2002, 73, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculean, A.; Chiantella, G.C.; Windisch, P.; Gera, I.; Reich, E. Clinical Evaluation of an Enamel Matrix Protein Derivative (Emdogain) Combined with a Bovine-Derived Xenograft (Bio-Oss) for the Treatment of Intrabony Periodontal Defects in Humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2002, 22, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sculean, A.; Barbé, G.; Chiantella, G.C.; Arweiler, N.B.; Berakdar, M.; Brecx, M. Clinical Evaluation of an Enamel Matrix Protein Derivative Combined with a Bioactive Glass for the Treatment of Intrabony Periodontal Defects in Humans. J Periodontol 2002, 73, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoidal, M.J.; Grimard, B.A.; Mills, M.P.; Schoolfield, J.D.; Mellonig, J.T.; Mealey, B.L. Clinical Evaluation of Demineralized Freeze-Dried Bone Allograft with and without Enamel Matrix Derivative for the Treatment of Periodontal Osseous Defects in Humans. J Periodontol 2008, 79, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspriello, S.D.; Ferrante, L.; Rubini, C.; Piemontese, M. Comparative Study of DFDBA in Combination with Enamel Matrix Derivative versus DFDBA Alone for Treatment of Periodontal Intrabony Defects at 12 Months Post-Surgery. Clin Oral Investig 2011, 15, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Deo, V. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Enamel Matrix Derivative, Bone Grafts, and Membrane in the Treatment of Mandibular Class II Furcation Defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2013, 33, e58–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.F.S.; Ribeiro, E.D.P.; Casarin, R.C. V; Ruiz, K.G.S.; Junior, F.H.N.; Sallum, E.A.; Casati, M.Z. Hydroxyapatite/β-Tricalcium Phosphate and Enamel Matrix Derivative for Treatment of Proximal Class II Furcation Defects: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Periodontol 2013, 40, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.A.; Santamaria, M.P.; Casati, M.Z.; Ruiz, K.S.; Nociti, F.; Sallum, A.W.; Sallum, E.A. Enamel Matrix Protein Derivative and/or Synthetic Bone Substitute for the Treatment of Mandibular Class II Buccal Furcation Defects. A 12-Month Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Oral Investig 2016, 20, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Jeong, S.-N. Adjunctive Use of Enamel Matrix Derivatives to Porcine-Derived Xenograft for the Treatment of One-Wall Intrabony Defects: Two-Year Longitudinal Results of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Periodontol 2020, 91, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. PubMed 2.0. Med Ref Serv Q 2020, 39, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, B.; Chang, J. Biopython: Python Tools for Computational Biology. ACM Sigbio Newsletter 2000, 20, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference; van der Walt, S., Millman, J., Eds.; 2010; pp. 51–56.

- Thakkar, H.; Manimaran, A. Comprehensive Examination of Instruction-Based Language Models: A Comparative Analysis of Mistral-7B and Llama-2-7B. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Emerging Research in Computational Science (ICERCS); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–6.

- Oza, J.; Yadav, H. Enhancing Question Prediction with Flan T5-A Context-Aware Language Model Approach. Authorea Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan, I.; Gandhi, S.; Khare, O.; Joshi, A.; Sawant, S. A Comparative Analysis of Distributed Training Strategies for GPT-2. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.15628. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.Y.K.; Miao, B.Y.; Butte, A.J. Evaluating the Use of GPT-3.5-Turbo to Provide Clinical Recommendations in the Emergency Department. medRxiv 2023, 2010–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Moushi, O.M. Gpt-4o: The Cutting-Edge Advancement in Multimodal Llm. Authorea Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Sang, J.; Arora, R.; Kloosterman, R.; Cecere, M.; Gorla, J.; Saleh, R.; Chen, D.; Drennan, I.; Teja, B. Prompting Is All You Need: LLMs for Systematic Review Screening. medRxiv 2024, 2024–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Bisong, E. Google Colaboratory. In Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners; Bisong, E., Ed.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, 2019; pp. 59–64 ISBN 978-1-4842-4470-8.

- Sentence-Transformers/All-Mpnet-Base-V2. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. 2011. Available online: scikit-learn. org (accessed on 20 December 2021) 2019.

| PMID | Title | Journal | Year | Reference |

| 11990444 | A clinical comparison of a bovine-derived xenograft used alone and in combination with enamel matrix derivative for the treatment of periodontal osseous defects in humans. | Journal of periodontology | 2002 | [24] |

| 12186348 | Clinical evaluation of an enamel matrix protein derivative (Emdogain) combined with a bovine-derived xenograft (Bio-Oss) for the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects in humans. | The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry | 2002 | [25] |

| 11990441 | Clinical evaluation of an enamel matrix protein derivative combined with a bioactive glass for the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects in humans. | Journal of periodontology | 2002 | [26] |

| 19053917 | Clinical evaluation of demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft with and without enamel matrix derivative for the treatment of periodontal osseous defects in humans. | Journal of periodontology | 2008 | [27] |

| 20054593 | Comparative study of DFDBA in combination with enamel matrix derivative versus DFDBA alone for treatment of periodontal intrabony defects at 12 months post-surgery. | Clinical oral investigations | 2011 | [28] |

| 23484181 | Evaluation of the effectiveness of enamel matrix derivative, bone grafts, and membrane in the treatment of mandibular Class II furcation defects. | The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry | 2013 | [29] |

| 23379539 | Hydroxyapatite/beta-tricalcium phosphate and enamel matrix derivative for treatment of proximal class II furcation defects: a randomized clinical trial. | Journal of clinical periodontology | 2013 | [30] |

| 26556577 | Enamel matrix protein derivative and/or synthetic bone substitute for the treatment of mandibular class II buccal furcation defects. A 12-month randomized clinical trial. | Clinical oral investigations | 2016 | [31] |

| 31811645 | Adjunctive use of enamel matrix derivatives to porcine-derived xenograft for the treatment of one-wall intrabony defects: Two-year longitudinal results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. | Journal of periodontology | 2020 | [32] |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 190 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Q2 | 191 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Q3 | 191 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Q4 | 188 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 178 | 13 | 0 | 9 |

| Q2 | 170 | 21 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 168 | 23 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 147 | 44 | 0 | 9 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 12 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| Q2 | 18 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

| Q3 | 23 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Q4 | 41 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 178 | 13 | 0 | 9 |

| Q2 | 170 | 21 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 168 | 23 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 147 | 44 | 0 | 9 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 9 |

| Q2 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 0 | 44 | 0 | 9 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 190 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Q2 | 190 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 189 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 170 | 21 | 0 | 9 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 185 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| Q2 | 188 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| Q3 | 184 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Q4 | 162 | 29 | 1 | 8 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q2 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 190 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Quartile | TN | FP | FN | TP |

| Q1 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q2 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q3 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Q4 | 188 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).