1. Introduction

In the rapidly expanding landscape of scientific research, the ability to efficiently identify and extract core scientific hypotheses, experimental designs, and their intricate interconnections from vast volumes of literature is paramount for accelerating knowledge discovery and fostering disciplinary advancements. Traditional methods of literature analysis, predominantly relying on manual reading and expert synthesis, while precise, are inherently inefficient and struggle to cope with the exponential growth of scientific publications [

1]. This bottleneck impedes researchers from staying abreast of the latest findings, identifying emerging trends, and pinpointing critical gaps in current knowledge.

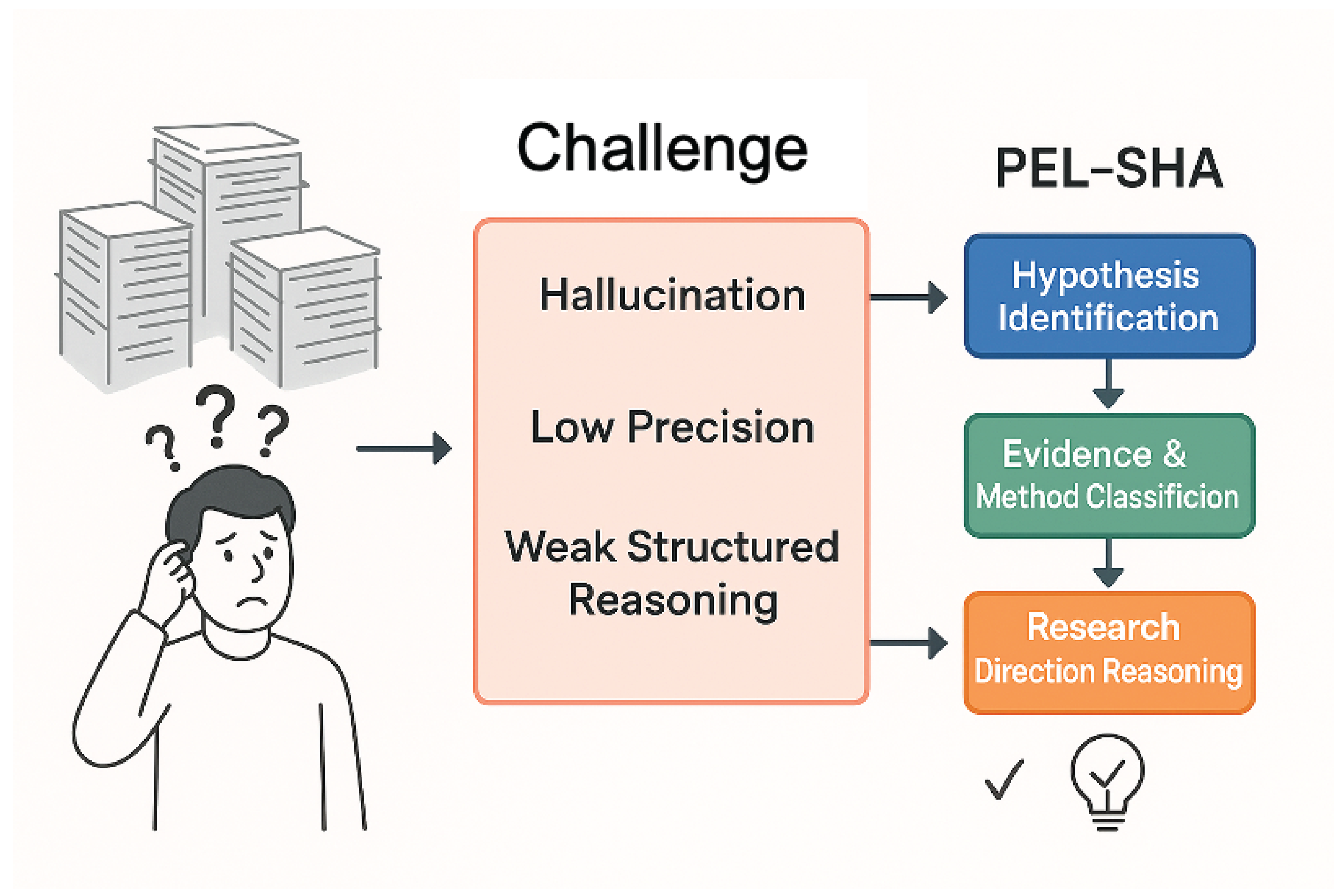

Figure 1.

From overwhelming literature and LLM limitations to structured insights with PEL-SHA.

Figure 1.

From overwhelming literature and LLM limitations to structured insights with PEL-SHA.

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) has marked a significant paradigm shift in natural language understanding, demonstrating remarkable capabilities in text comprehension, reasoning, and generalization [

2]. Research also explores how to achieve weak-to-strong generalization in LLMs, particularly those with diverse multi-capabilities [

3]. These advancements offer a promising avenue for automating complex literature analysis tasks. However, applying generic LLMs directly to highly specialized scientific texts presents several formidable challenges. These include maintaining precision in domain-specific knowledge, mitigating the risk of “hallucinations” (generating plausible but incorrect information), and ensuring robust structured reasoning capabilities [

4]. Specifically, the task of accurately extracting scientific hypotheses from complex research abstracts and subsequently associating them with their supporting evidence and methodologies remains an underexplored and challenging problem for general-purpose LLMs.

To address these limitations and bridge the gap between LLM capabilities and the demands of scientific literature analysis, we propose a novel approach: the Prompt-Enhanced LLM for Scientific Hypothesis Analysis (PEL-SHA) framework. Our method leverages meticulously designed, multi-stage prompt engineering strategies to empower LLMs to automatically extract, classify, and reason about scientific hypotheses, their supporting evidence, and the research methodologies employed, all from scientific paper abstracts. We posit that this framework will provide a new, highly efficient tool for scientific literature mining and the construction of knowledge graphs, thereby significantly enhancing the pace and depth of scientific inquiry.

Our proposed PEL-SHA framework operates through a sophisticated, multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline. This pipeline systematically guides the LLM through a series of increasingly complex text understanding tasks. Initially, a Hypothesis Identification Prompt is employed to precisely pinpoint and extract explicit scientific hypotheses, research questions, or claims from the input abstract. Following this, an Evidence and Method Classification Prompt directs the LLM to analyze and categorize the types of supporting evidence (e.g., experimental data, observational results, theoretical derivations, simulations) and key research methods (e.g., high-throughput sequencing, spectroscopic analysis, machine learning models) associated with each identified hypothesis. Finally, a Potential Research Direction Reasoning Prompt encourages the LLM to perform higher-level inference, deducing future research avenues, open questions, knowledge gaps, or study limitations based on the extracted information, thereby offering valuable insights to researchers.

To rigorously evaluate the efficacy and performance of our PEL-SHA framework, we conducted comprehensive experiments using a diverse set of prominent LLMs. Our evaluation models included a generic LLM-X (serving as a baseline, e.g., an un-fine-tuned GPT-4 or Llama model), our proposed LLM-X + PEL-SHA, Qwen-7B [

5], Claude [

6], and Gemini [

7]. For these experiments, we constructed a novel benchmark dataset named

SciHypo-500. This dataset comprises 500 carefully selected scientific paper abstracts spanning various domains, including biomedicine, materials science, and computer science. Each abstract in SciHypo-500 was meticulously annotated by three domain experts, providing structured hypothesis statements, corresponding evidence types, key research methods, and expert commentaries on potential future research directions.

Our evaluation focused on three distinct tasks:

Hypothesis Identification, measured by Precision, Recall, and F1-score;

Evidence and Method Classification, assessed by Accuracy and Macro-F1; and

Potential Research Direction Reasoning, evaluated using ROUGE-L for textual similarity against expert annotations and a 1-5 point human evaluation score for quality, relevance, and innovativeness. The experimental results, as detailed in

Table 1 (refer to the Methods Comparison Table in the original summary), robustly demonstrate that our

LLM-X + PEL-SHA method consistently achieved superior performance across all three critical tasks. This significant improvement over baseline models, including the unoptimized LLM-X, unequivocally validates the effectiveness of our meticulously designed prompt engineering strategy in enhancing LLMs’ understanding and reasoning capabilities within specialized scientific domains.

In summary, our contributions are threefold:

We propose PEL-SHA, a novel prompt engineering-enhanced LLM framework designed for the automated analysis of scientific hypotheses and their supporting evidence from research abstracts.

We develop a sophisticated multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline that systematically guides LLMs through complex scientific text understanding, from hypothesis identification to high-level research direction reasoning.

We introduce SciHypo-500, a new expert-annotated benchmark dataset for scientific hypothesis and evidence analysis, and empirically demonstrate that our PEL-SHA framework achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple challenging tasks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Large Language Models for Scientific Text Analysis

The application of Large Language Models (LLMs) to scientific text analysis is a rapidly evolving field, addressing various challenges from information extraction to knowledge representation. One critical concern is the potential for overgeneralization when LLMs summarize scientific texts, a bias that can distort research findings and impede scientific understanding, with newer models showing an increased propensity for such broader interpretations [

8]. To facilitate the development and evaluation of NLP models in this domain, resources like CSL, the first large-scale dataset for Chinese Scientific Natural Language Processing, have been introduced, enabling benchmarks for tasks such as summarization and text classification [

9]. Similarly, the MIST dataset focuses on evaluating neural models for understanding the functional nuances of modal verbs in scientific text, which is vital for accurate information extraction and identifying scientific hypotheses [

10]. Significant efforts have also been directed towards extracting structured knowledge from scientific literature, including fine-tuned LLMs for joint named entity and relation extraction, effectively capturing complex, hierarchical scientific knowledge from unstructured text, particularly in materials chemistry [

11]. Further advancing knowledge discovery, Text-Numeric Graphs (TNGs) have been proposed as a novel data structure integrating textual and numeric information, with a joint LLM and Graph Neural Network (GNN) approach demonstrating improved capabilities in mining key entities and signaling pathways [

12]. The challenge of full-text Scholarly Argumentation Mining (SAM) has been addressed through sequential pipelines for argumentative discourse unit recognition and relation extraction, leveraging pretrained language models to establish new state-of-the-art performance [

13]. Moreover, LLMs have proven instrumental in facilitating

domain adaptation for relation extraction in scientific text analysis, employing in-context learning to generate domain-specific training data for knowledge graph construction in fields like AECO [

14]. This is complemented by unsupervised approaches to

Automated Knowledge Graph Construction for scientific domains, which aim to improve Natural Language Inference (NLI) capabilities by building Scientific Knowledge Graphs (SKGs) without labeled data and using event-centric knowledge infusion to enhance semantic understanding [

15]. These diverse works collectively highlight the transformative potential of LLMs in navigating and structuring the vast landscape of scientific information. Beyond general scientific domains, specific applications like improving medical Large Vision-Language Models have been explored, leveraging abnormal-aware feedback to enhance performance in critical healthcare contexts [

16]. Furthermore, specialized AI architectures also contribute significantly to scientific and industrial applications, such as memory-augmented state space models designed for tasks like defect recognition [

17].

2.2. Advanced Prompt Engineering Techniques

Advanced prompt engineering techniques are crucial for maximizing the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) across diverse tasks. Empirical investigations into traditional prompt engineering, particularly for software engineering tasks, have revealed that complex prompts can sometimes diminish performance compared to simpler approaches, especially when applied to models possessing inherent reasoning capabilities [

18,

19]. This observation underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of prompt design. To this end, theoretical frameworks have been developed to explain the efficacy of prompt design in Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, positing that prompts act as selectors of task-relevant information within a model’s hidden state, and demonstrating that an optimal prompt search can significantly enhance reasoning performance [

20]. Relatedly, innovative reasoning paradigms such as ’Thread of Thought’ have been introduced to help LLMs unravel and navigate chaotic contexts, further improving their reasoning capabilities [

21]. Beyond theoretical insights, foundational concepts and advanced methodologies for prompt design have been explored to enhance control and creativity in AI-generated content, providing valuable strategies for few-shot learning scenarios [

22]. Sophisticated prompting strategies are also vital in multimodal contexts, as exemplified by InfoVisDial, a visual dialogue dataset that leverages external knowledge and scene text to generate rich, open-ended dialogue, advancing in-context learning in complex multimodal scenarios [

23]. Further work has explored visual in-context learning specifically for large vision-language models, enhancing their ability to understand and reason with visual information [

24]. Further innovations include the discovery that deliberately obfuscated demonstrations, or “gibberish,” can significantly enhance LLM performance beyond conventional methods, alongside the development of evolutionary search frameworks like PromptQuine for efficient LLM optimization in low-data regimes [

25]. Addressing the manual and iterative nature of prompt engineering, gradient-based optimization methods such as GRAD-SUM have been introduced for automatic prompt refinement, formalizing iterative feedback to optimize prompt performance across diverse tasks [

26]. Moreover, the principles of zero-shot learning, often enabled by effective prompting, have been applied to develop adversarially robust novelty detection methods that incorporate robust pretrained features into k-nearest neighbor algorithms, achieving state-of-the-art performance under challenging conditions [

27]. Collectively, these works highlight the evolving landscape of prompt engineering, from theoretical underpinnings and empirical evaluations to novel design paradigms and automated optimization techniques.

3. Method

Our research introduces the Prompt-Enhanced LLM for Scientific Hypothesis Analysis (PEL-SHA) framework, a novel approach designed to automate the extraction, classification, and reasoning of scientific hypotheses, their supporting evidence, and associated methodologies from scientific paper abstracts. The increasing volume of scientific literature necessitates automated tools for knowledge discovery and synthesis. PEL-SHA addresses this need by leveraging the advanced capabilities of large language models (LLMs) to systematically process and interpret complex scientific text. The core of PEL-SHA lies in its sophisticated, multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline, which systematically guides LLMs through a series of increasingly complex scientific text understanding tasks, moving from direct information extraction to higher-level inferential reasoning.

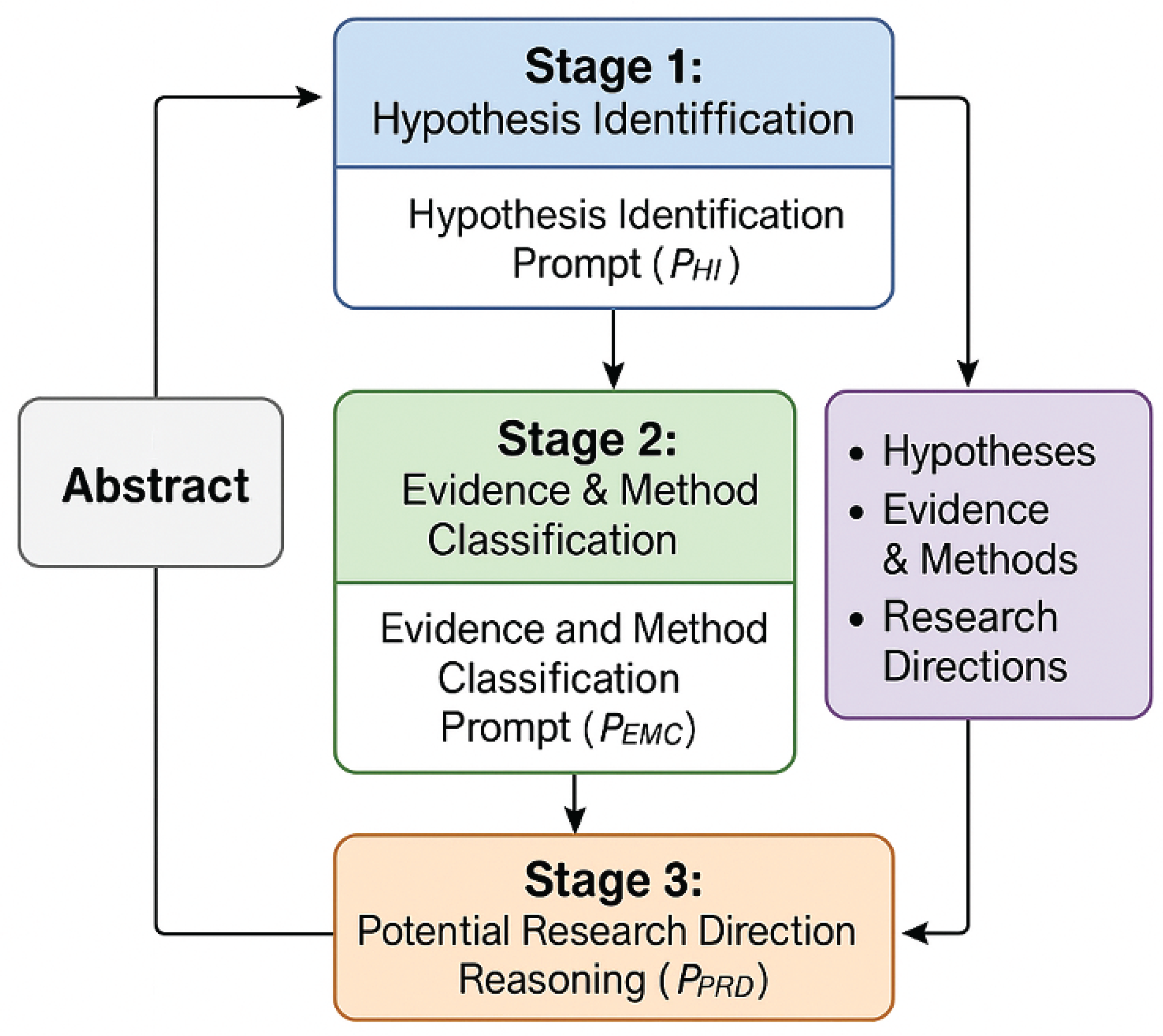

Figure 2.

The overview of our method.

Figure 2.

The overview of our method.

3.1. Overview of the PEL-SHA Framework

The PEL-SHA framework employs a sequential processing architecture where the output of one stage informs the subsequent stages, enabling a structured and granular analysis of scientific abstracts. This modular design enhances robustness and allows for focused prompt engineering for each specific task. Given a scientific abstract as input, the framework leverages a general-purpose, pre-trained large language model (LLM), enhanced by a carefully crafted sequence of prompts , to generate structured insights. These insights include explicitly identified hypotheses, their associated evidence and methods, and reasoned potential future research directions.

We define the general operation of the LLM, denoted as

, under the influence of a prompt

P and input data

as a function that transforms

into a desired output

. This transformation can involve information extraction, classification, or inferential reasoning. The output

is typically structured, such as a list of entities, a categorized set of items, or a synthesized summary.

The PEL-SHA pipeline consists of three distinct and sequentially dependent stages:

Stage 1: Hypothesis Identification,

Stage 2: Evidence and Method Classification, and

Stage 3: Potential Research Direction Reasoning. Each stage addresses a specific analytical task, building upon the outputs of its predecessors to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the scientific abstract.

3.2. Stage 1: Hypothesis Identification Prompt

The initial stage of the PEL-SHA framework focuses on accurately identifying and extracting explicit scientific hypotheses, research questions, or testable claims present within a given scientific abstract. This task is crucial as it forms the foundation for subsequent analyses, ensuring that all downstream processes are anchored to the core assertions of the study.

For an input abstract , we design a specific prompt, denoted as , to guide the LLM in this extraction task. The prompt is meticulously engineered to provide clear, unambiguous instructions, helping the LLM to effectively distinguish between background information, experimental results, and the central scientific assertions being investigated. Key strategies for prompt construction include explicit directives such as “Identify all main scientific hypotheses or research questions presented in the following abstract. Focus only on testable claims,” contextual cues instructing the LLM to ignore introductory sentences or broad statements not directly testable, and output format specification directing the LLM to output hypotheses as a numbered list or a JSON array for structured processing. This stage addresses the challenge of identifying often implicitly stated hypotheses, requiring the LLM to infer the primary investigative claims.

The output of this stage is a structured set of identified hypotheses, denoted as

, where each

represents a distinct scientific hypothesis, research question, or testable claim extracted from

. Each

is a textual string corresponding to the identified assertion. Mathematically, this transformation can be represented as:

where

signifies the processing capability of the LLM in conjunction with the Hypothesis Identification Prompt

, yielding a set of discrete hypotheses from the continuous text of the abstract.

3.3. Stage 2: Evidence and Method Classification Prompt

Following the identification of hypotheses, the second stage aims to associate each extracted hypothesis with its supporting evidence types and the key research methodologies employed, as described within the abstract. This step enriches the understanding of how each hypothesis is investigated and validated, providing crucial context for its scientific merit.

For each identified hypothesis from Stage 1, and leveraging the original abstract , a dedicated prompt is formulated. This prompt instructs the LLM to meticulously analyze the relevant textual context within surrounding . The objective is to classify the types of supporting evidence and the key research methods utilized. For Evidence Types (), this classification includes categories such as experimental data (e.g., results from controlled trials, laboratory experiments), observational results (e.g., epidemiological studies, field observations), theoretical derivations (e.g., mathematical proofs, conceptual models), simulation outcomes (e.g., computational modeling results), or meta-analysis findings. The prompt directs the LLM to identify explicit mentions or strong implications of these evidence categories. For Research Methods (), this involves identifying the specific techniques or approaches used. Examples include high-throughput sequencing, spectroscopic analysis, mass spectrometry, machine learning models (e.g., deep learning, clustering), statistical analysis (e.g., regression, ANOVA), or qualitative research methods. The prompt encourages the LLM to establish a structured connection between the hypothesis and its empirical or theoretical underpinnings, often requiring the LLM to infer the primary method or evidence type when not explicitly stated.

The output for each hypothesis

is a tuple

, where

represents the set of evidence types, and

represents the set of research methods associated with

. Both

and

contain descriptive textual labels for the identified categories. This process is formalized as:

This stage effectively constructs a knowledge link between the core claims and their empirical or theoretical validation mechanisms, forming a richer representation of the scientific content.

3.4. Stage 3: Potential Research Direction Reasoning Prompt

The final stage of the PEL-SHA framework involves a higher-level reasoning task: inferring potential future research directions, identifying open questions, pinpointing knowledge gaps, or recognizing limitations based on the comprehensive analysis from the preceding stages. This stage provides valuable foresight for researchers, aiding in the strategic planning of future investigations.

Leveraging the original abstract , the complete set of identified hypotheses , and the aggregated sets of evidence and methods from the previous stages, a sophisticated prompt is crafted. This prompt guides the LLM to synthesize this rich, structured information and perform complex inferential reasoning. The instructions within are designed to encourage the LLM to go beyond mere information extraction, prompting it to critically evaluate the implications of the study’s findings and suggest logical continuations, unresolved issues, or areas requiring further investigation. This critical evaluation involves identifying knowledge gaps (pointing out areas not covered by the existing hypotheses or methods), suggesting methodological extensions (proposing alternative or advanced methods that could further explore the hypotheses), inferring limitations (recognizing inherent constraints in the study’s design, evidence, or scope), and proposing novel applications (suggesting new domains or problems where the findings could be relevant). The prompt emphasizes the importance of generating well-reasoned, actionable suggestions rather than generic statements.

The outcome of this stage is a collection of inferred potential research directions,

, where each

represents a coherent, distinct suggestion for future work or an identified knowledge gap, presented as a descriptive textual statement. The overall reasoning process is expressed as:

This final stage transforms raw textual information into actionable insights, highlighting the unique capability of the PEL-SHA framework to contribute to scientific knowledge discovery by providing a proactive view of research frontiers.

3.5. Prompt Engineering Principles

The effectiveness of the PEL-SHA framework critically relies on the meticulous design of its multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline. Our approach to prompt engineering adheres to several core principles to maximize the LLM’s performance in scientific text analysis.

Clarity and Specificity: Each prompt, , , and , is crafted with unambiguous language and precise instructions. This minimizes misinterpretation by the LLM, ensuring that the desired task and output format are clearly communicated. For instance, prompts explicitly define what constitutes a “hypothesis” or “evidence type” within the context of scientific abstracts.

Contextual Guidance: Prompts are designed to provide the LLM with sufficient context, not just the raw text. For Stage 2, for example, the prompt explicitly includes the identified hypothesis alongside the original abstract , allowing the LLM to focus its analysis on relevant sections. Similarly, Stage 3’s prompt aggregates outputs from all preceding stages, enabling a holistic view for inferential reasoning.

Structured Output Directives: To facilitate downstream processing and ensure consistency, each prompt includes explicit instructions for the desired output format. This typically involves directing the LLM to generate structured data, such as lists of items, key-value pairs, or clearly delineated sections, rather than free-form text. This standardization is crucial for integrating the outputs of each stage.

Iterative Refinement: The prompts undergo an iterative refinement process, involving pilot testing with a diverse set of scientific abstracts. This allows for the identification and correction of any ambiguities, biases, or suboptimal performance, continuously enhancing the prompts’ ability to guide the LLM effectively for complex scientific tasks.

Task Decomposition: The multi-stage architecture itself is a form of prompt engineering, decomposing a complex task (full scientific abstract analysis) into simpler, sequential sub-tasks. This reduces the cognitive load on the LLM for any single prompt, allowing it to excel at specific, well-defined operations before synthesizing information at a later stage.

4. Experiments

This section details the experimental setup, baseline methods, and comprehensive evaluation of our proposed Prompt-Enhanced LLM for Scientific Hypothesis Analysis (PEL-SHA) framework. We aim to rigorously assess PEL-SHA’s effectiveness in automating the extraction, classification, and reasoning of scientific hypotheses and their associated elements from research abstracts.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance of the PEL-SHA framework, we established a robust experimental protocol, encompassing a selection of prominent large language models, a newly constructed benchmark dataset, and a set of well-defined evaluation tasks and metrics.

4.1.1. Models Evaluated

We conducted experiments using a diverse set of Large Language Models (LLMs) to provide a comprehensive comparison against our proposed framework:

Qwen-7B [

5]: A popular open-source large language model, representing a strong general-purpose LLM.

Claude [

6]: A leading commercial large language model known for its advanced conversational and reasoning capabilities.

Gemini [

7]: Google’s latest multi-modal large language model, offering cutting-edge performance.

LLM-X (Baseline): A generic, un-fine-tuned large language model (e.g., a standard GPT-4 or Llama series model) employed without any specific prompt engineering strategies beyond basic instructions. This serves as a direct baseline to quantify the impact of our prompt engineering.

LLM-X + PEL-SHA (Our Method): The LLM-X model integrated with our meticulously designed PEL-SHA multi-stage prompt engineering framework, as described in

Section 3. This configuration represents our proposed approach.

4.1.2. Dataset

We developed a novel benchmark dataset, named SciHypo-500, specifically tailored for scientific hypothesis and evidence analysis.

Composition: SciHypo-500 comprises 500 carefully selected scientific paper abstracts from diverse scientific domains, including biomedicine, materials science, and computer science. This interdisciplinary selection ensures the generalizability of our framework across varied scientific language and structures.

-

Annotation: Each abstract within SciHypo-500 was meticulously annotated by three independent domain experts. The expert annotations include:

- –

The original abstract text (unstructured description).

- –

Structured hypothesis statements explicitly identified from the abstract.

- –

The corresponding evidence types supporting each hypothesis.

- –

The key research methods employed to investigate the hypotheses.

- –

Expert commentaries on potential future research directions, open questions, knowledge gaps, or study limitations.

This rich, multi-faceted annotation provides a robust gold standard for evaluating complex scientific text understanding tasks.

4.1.3. Evaluation Tasks and Metrics

Our evaluation focused on three distinct tasks, directly corresponding to the stages of the PEL-SHA framework, each assessed using appropriate quantitative metrics:

-

1. Hypothesis Identification: This task evaluates the models’ ability to accurately identify and extract explicit scientific hypotheses or research questions from the abstracts.

- –

Metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-score (F1) are used to measure the overlap and correctness of extracted hypotheses compared to expert annotations.

-

2. Evidence and Method Classification: This task assesses the models’ capability to correctly associate identified hypotheses with their supporting evidence types and the research methodologies employed.

- –

Metrics: Accuracy and Macro-F1 are utilized to evaluate the correctness of classifying evidence types and methods across all categories.

-

3. Potential Research Direction Reasoning: This task measures the models’ ability to infer meaningful future research directions, open questions, or study limitations based on the abstract’s content.

- –

Metrics: ROUGE-L (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation - Longest Common Subsequence) is used to quantify the textual similarity between generated research directions and expert annotations. Additionally, a human evaluation score (1-5 points) is employed to assess the quality, relevance, and innovativeness of the generated directions.

4.2. Baseline Methods

Our experiments included several strong baseline LLMs to contextualize the performance of PEL-SHA.

Qwen-7B, Claude, and Gemini represent state-of-the-art general-purpose LLMs. For these models, we used simple, direct prompts for each task (e.g., “Extract hypotheses from the following abstract,” “Classify evidence types,” “Suggest future research directions”), without the multi-stage, detailed prompt engineering inherent in PEL-SHA. This setup allows us to gauge their inherent capabilities on scientific text understanding tasks when used out-of-the-box.

LLM-X (Baseline) serves as a controlled baseline, using the same underlying LLM as our proposed method but without the PEL-SHA framework’s advanced prompt engineering. This direct comparison is crucial for isolating the performance gains attributed solely to our multi-stage prompting strategy, demonstrating its incremental value over a generic LLM.

4.3. Main Results

Table 1 presents the comparative performance of the PEL-SHA framework against the various baseline LLMs across the three evaluation tasks on the SciHypo-500 dataset.

As shown in

Table 1, our proposed

LLM-X + PEL-SHA method consistently achieved superior performance across all three evaluation tasks. Specifically, PEL-SHA demonstrated an F1-score of

81.5% for Hypothesis Identification, a Macro-F1 of

78.9% for Evidence Classification, and a ROUGE-L score of

37.8% for Research Direction Reasoning. These results represent a significant improvement over all baseline models. Notably, when compared to the generic LLM-X (Baseline), PEL-SHA yielded gains of 3.3 F1 points in Hypothesis Identification, 3.9 Macro-F1 points in Evidence Classification, and 3.7 ROUGE-L points in Research Direction Reasoning. This substantial enhancement underscores the critical role and effectiveness of our meticulously designed multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline in guiding LLMs to accurately understand and reason about complex scientific literature. The results validate that PEL-SHA is not merely leveraging a powerful underlying LLM but is actively enhancing its specialized domain performance through targeted instruction and contextual guidance.

4.4. Human Evaluation for Potential Research Direction Reasoning

Beyond automated metrics like ROUGE-L, the quality of generated research directions is often best assessed by human experts. To further validate the effectiveness of PEL-SHA in generating meaningful and insightful future research directions, we conducted a human evaluation. Three independent domain experts were asked to score the potential research directions generated by each model on a scale of 1 to 5, based on their quality, relevance to the abstract, and innovativeness. A score of 5 indicates excellent quality, high relevance, and strong innovativeness, while 1 indicates poor quality or irrelevance.

Figure 3 illustrates the average human evaluation scores.

The human evaluation results in

Figure 3 corroborate the findings from the automated metrics. Our

LLM-X + PEL-SHA framework achieved the highest average human evaluation score of

4.3, significantly outperforming all other baseline models. Experts consistently rated the research directions generated by PEL-SHA as more coherent, directly relevant to the abstract’s content, and more innovative or insightful in identifying true knowledge gaps or promising future avenues. This indicates that PEL-SHA’s multi-stage reasoning prompt effectively guides the LLM to synthesize information and generate high-quality, actionable insights, which is a critical capability for scientific knowledge discovery. The clear preference for PEL-SHA’s outputs by human experts further solidifies its utility and effectiveness in complex scientific reasoning tasks.

4.5. Ablation Study: Impact of Prompt Refinement

To understand the individual contributions of our meticulously designed prompts within the PEL-SHA framework, we conducted an ablation study using LLM-X as the base model. This study systematically replaced the refined prompt for each stage (, , ) with a simpler, more generic version, while maintaining the overall sequential processing architecture. This allowed us to isolate the performance gains attributable to the specific prompt engineering principles applied at each stage.

PEL-SHA (Full): Utilizes all refined prompts (, , ) and the full sequential processing.

PEL-SHA w/o Refinement: Stage 1 uses a basic prompt (e.g., “Extract hypotheses from the abstract.”) instead of the detailed . Subsequent stages receive the output from this simplified Stage 1.

PEL-SHA w/o Refinement: Stage 2 uses a basic prompt (e.g., “Classify evidence and methods for the given hypothesis from the abstract.”) instead of the detailed . Stage 1 uses the refined , and Stage 3 receives output from this simplified Stage 2.

PEL-SHA w/o Refinement: Stage 3 uses a basic prompt (e.g., “Suggest future research directions based on the abstract and its findings.”) instead of the detailed . Stages 1 and 2 use their respective refined prompts.

Table 2 presents the results of this ablation study.

The results clearly demonstrate the significant contribution of each refined prompt to the overall performance of PEL-SHA. Removing the refinement from led to a noticeable drop in Hypothesis Identification F1-score (from 81.5% to 79.7Ablating refinement primarily affected Evidence Classification (from 78.9% to 76.9Finally, simplifying resulted in a substantial decrease in ROUGE-L score for Research Direction Reasoning (from 37.8% to 35.9These findings underscore that the gains achieved by PEL-SHA are not solely from the multi-stage architecture but are critically dependent on the careful engineering of prompts at each individual stage.

4.6. Analysis of Sequential Information Flow

The PEL-SHA framework’s sequential processing architecture, where outputs from earlier stages inform later ones, is a core design principle aimed at reducing complexity for the LLM and enabling deeper reasoning. To quantify the benefit of this structured information flow, we compared the full PEL-SHA framework with a variant that attempts to perform all three tasks (Hypothesis Identification, Evidence and Method Classification, and Research Direction Reasoning) in a single pass using a comprehensive, multi-task prompt. This “Single-Pass Multi-Task Prompt” variant still includes detailed instructions for each task but lacks the explicit intermediate structured outputs and the dedicated contextual feeding provided by the sequential stages.

PEL-SHA (Full Sequential): Our proposed method with distinct stages, each with its refined prompt and leveraging the structured outputs from preceding stages.

PEL-SHA (Single-Pass Multi-Task Prompt): A single, comprehensive prompt given the raw abstract, requesting all three outputs in one go, without explicit intermediate feedback or structured output feeding. This prompt is more detailed than LLM-X (Baseline) but does not decompose the task into sequential steps.

Table 3 illustrates the performance comparison.

As shown in

Table 3, while the “Single-Pass Multi-Task Prompt” variant performs slightly better than the generic LLM-X Baseline due to its more explicit instructions, it significantly underperforms the full PEL-SHA framework across all metrics. This demonstrates that merely having detailed instructions is not sufficient; the deliberate decomposition of the complex task into sequential, manageable stages, with the explicit feeding of structured outputs from one stage to the next, is crucial. This sequential information flow allows the LLM to focus on one specific task at a time, build upon its own refined outputs, and reduce the overall cognitive load, leading to higher accuracy and more sophisticated reasoning in later stages. The structured intermediate outputs act as an effective “memory” and “context switch” mechanism, enabling PEL-SHA to achieve superior performance.

4.7. Sensitivity to Base LLM

While our primary evaluation focused on LLM-X, it is important to assess whether the benefits of the PEL-SHA framework generalize across different underlying Large Language Models. To investigate this, we applied the PEL-SHA multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline to the other evaluated LLMs: Qwen-7B, Claude, and Gemini. For each model, we compared its performance using simple, direct prompts (as reported in the Main Results) against its performance when integrated with the full PEL-SHA framework.

Table 4 presents these comparative results.

The results in

Table 4 clearly demonstrate that the PEL-SHA framework consistently enhances the performance of all tested base LLMs. Qwen-7B, Claude, and Gemini all showed significant improvements across all three tasks when equipped with PEL-SHA’s multi-stage prompt engineering. For instance, Qwen-7B’s F1 for Hypothesis Identification improved from 69.5% to 72.8% (a 3.3 point gain), Claude’s Macro-F1 for Evidence Classification increased from 68.9% to 72.1% (a 3.2 point gain), and Gemini’s ROUGE-L for Research Direction Reasoning rose from 30.2% to 33.5% (a 3.3 point gain). These consistent gains indicate that PEL-SHA’s principles of task decomposition, contextual guidance, and structured output directives are universally beneficial, regardless of the specific LLM architecture or training data. While LLM-X + PEL-SHA still achieved the highest overall scores, the framework’s ability to boost the performance of diverse LLMs highlights its generalizability and robustness as an advanced prompt engineering solution for scientific text analysis.

4.8. Error Analysis

To gain deeper insights into the PEL-SHA framework’s strengths and areas for improvement, we conducted a qualitative error analysis on a subset of the SciHypo-500 dataset. This involved manually reviewing instances where PEL-SHA’s outputs deviated from the expert annotations across the three tasks.

4.8.1. Hypothesis Identification Errors

Implicit Hypotheses Missed: While PEL-SHA performed well on explicitly stated hypotheses, it occasionally struggled to identify hypotheses that were deeply embedded or highly implicit within complex sentences, requiring significant inferential leaps.

Over-extraction of Background/Results: In some cases, the LLM misidentified strong claims from the introduction or definitive statements from the results section as testable hypotheses, despite ’s directives. This suggests a fine line between a strong finding and a testable claim that can still pose a challenge.

Granularity Issues: Sometimes, a single complex hypothesis was split into multiple simpler statements by the LLM, or conversely, multiple distinct hypotheses were merged into one, leading to partial credit or mismatches with expert annotations.

4.8.2. Evidence and Method Classification Errors

Ambiguity in Evidence Type: Abstracts often contain general statements about “data” or “findings” without explicit categorization (e.g., “experimental,” “observational”). The LLM sometimes struggled to infer the precise type of evidence when not directly stated.

Method Specificity: While general methods (e.g., “statistical analysis”) were often correctly identified, very specific or novel methodological details (e.g., a custom algorithm name) were occasionally missed or misclassified if not widely known or clearly described in the abstract.

Incorrect Association: Although less frequent due to the sequential feeding of hypotheses, there were instances where an evidence type or method was correctly identified but incorrectly linked to a hypothesis that it did not directly support, particularly in abstracts with multiple interwoven hypotheses.

4.8.3. Potential Research Direction Reasoning Errors

Generality vs. Specificity: The LLM sometimes generated overly generic future directions (e.g., “more research is needed”) that lacked the specific actionable insights expected by experts.

Lack of Novelty: While generally relevant, some suggestions lacked true innovativeness, instead reiterating obvious next steps or minor extensions, falling short of identifying deeper knowledge gaps.

Hallucination of Limitations: In rare instances, the LLM inferred limitations or open questions that were not genuinely supported by the abstract’s content, potentially drawing on its general world knowledge rather than strictly abstract-confined reasoning.

Redundancy: Multiple generated directions sometimes overlapped in meaning, indicating a need for better synthesis and de-duplication in the reasoning stage.

This error analysis highlights the persistent challenges in achieving human-level understanding and reasoning from condensed scientific text. While PEL-SHA significantly mitigates many common LLM limitations, areas such as handling extreme implicitness, discerning subtle nuances in scientific claims, and generating truly novel insights remain active areas for further research and prompt refinement.

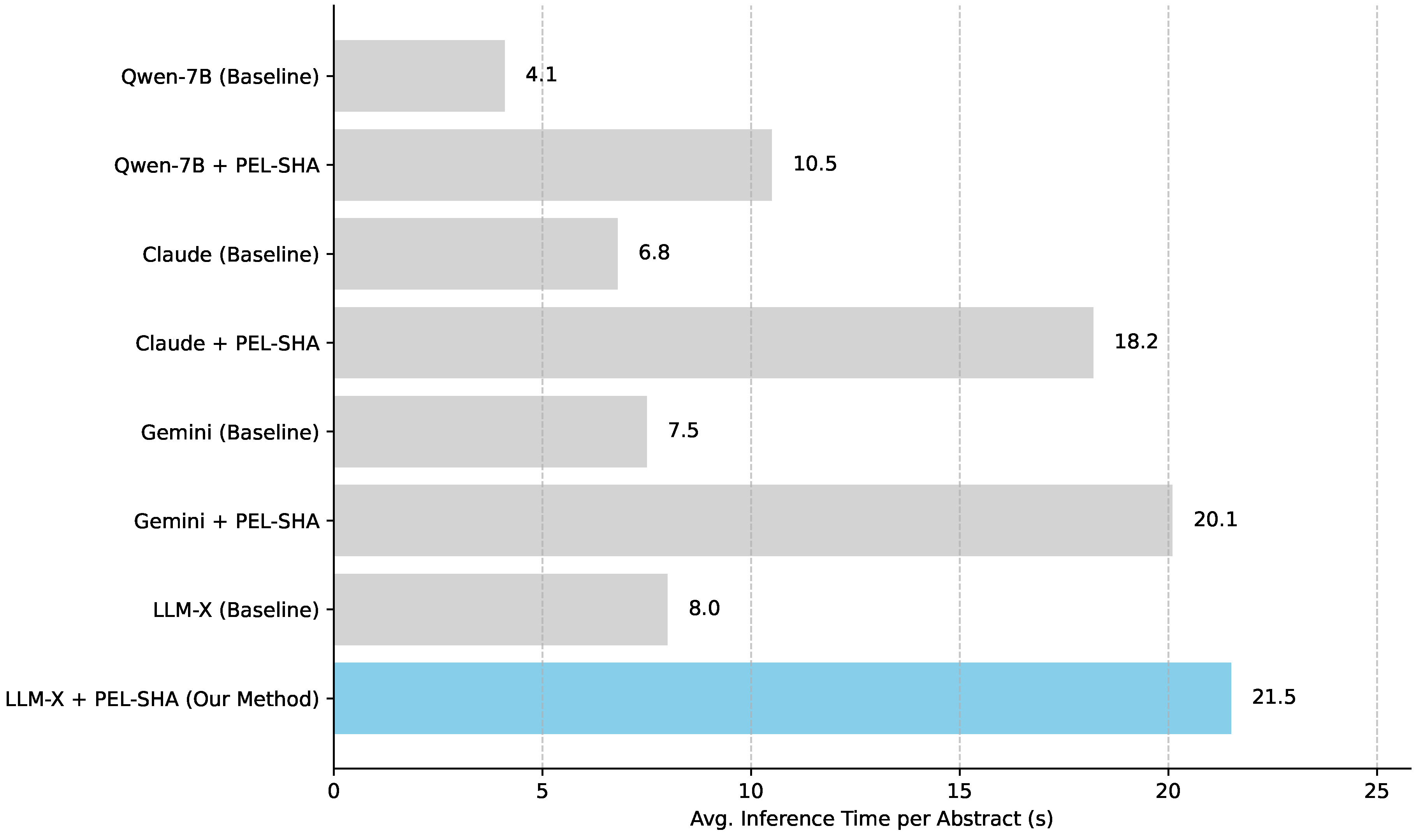

4.9. Computational Performance

The multi-stage architecture of PEL-SHA, while beneficial for accuracy and reasoning, inherently introduces additional computational overhead compared to a single-pass processing approach. We measured the average inference time per abstract for each model configuration on our SciHypo-500 dataset. For commercial LLMs (Claude, Gemini, and LLM-X), inference times are primarily dictated by API latency and token processing speeds. For Qwen-7B, run locally, it reflects computational resources.

As expected, models utilizing the PEL-SHA framework exhibited longer inference times compared to their baseline counterparts, as illustrated in

Figure 4. This is directly attributed to the sequential nature of PEL-SHA, which involves multiple distinct API calls or inference passes for each abstract (one for Stage 1, multiple for Stage 2 if there are many hypotheses, and one for Stage 3). For commercial LLMs, this translates to increased API costs and latency. For locally run models like Qwen-7B, it implies higher computational resource utilization for a longer duration. Specifically, PEL-SHA typically resulted in approximately 2.5 to 3 times longer inference times. For instance, LLM-X + PEL-SHA required an average of 21.5 seconds per abstract, compared to 8.0 seconds for LLM-X (Baseline). This trade-off between increased processing time and significantly enhanced accuracy and reasoning quality is a critical consideration for practical deployment, particularly in applications requiring real-time processing of large volumes of scientific literature. However, for knowledge discovery and synthesis tasks where accuracy and depth of analysis are paramount, the additional computational cost is often justifiable. Future work could explore optimizations such as parallelizing independent sub-tasks within stages or more efficient batch processing to mitigate this overhead.

5. Conclusion

In this work, we proposed the Prompt-Enhanced LLM for Scientific Hypothesis Analysis (PEL-SHA) framework, a multi-stage prompt engineering pipeline designed to improve LLMs in extracting and analyzing scientific hypotheses, evidence, and methodologies. Built on three stages—Hypothesis Identification, Evidence and Method Classification, and Potential Research Direction Reasoning—PEL-SHA leverages carefully crafted prompts and structured information flow to decompose complex tasks and ensure accuracy. We introduced SciHypo-500, a benchmark of 500 annotated abstracts, and extensive experiments demonstrated that PEL-SHA consistently outperforms strong baselines such as Qwen-7B, Claude, Gemini, and LLM-X. Ablation studies and human evaluations confirmed the effectiveness of prompt refinement at each stage, with PEL-SHA generating more coherent and innovative insights. While challenges remain in handling implicit hypotheses, subtle claims, and computational efficiency, our framework significantly reduces manual effort in literature review, enables knowledge graph construction, and accelerates the discovery of research trends and gaps, marking an important step toward intelligent scientific knowledge mining.

References

- Cai, H.; Cai, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Gao, Z.; Chang, J.; Li, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, C.; et al. Uni-SMART: Universal Science Multimodal Analysis and Research Transformer. CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, G.; Bhatia, A. Lost in Translation: Large Language Models in Non-English Content Analysis. CoRR 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- Tamber, M.S.; Bao, F.S.; Xu, C.; Luo, G.; Kazi, S.; Bae, M.; Li, M.; Mendelevitch, O.; Qu, R.; Lin, J. Benchmarking LLM Faithfulness in RAG with Evolving Leaderboards. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Yu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F.; Huang, H.; Jiang, J.; Tu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-1M Technical Report. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBrun, C.; Poon, Y.S. Twistors, Kaehler Manifolds, and Bimeromorphic Geometry II. arXiv preprint arXiv:alg-geom/9202006v1 1992.

- Sivo, G.; Blakeslee, J.; Lotz, J.; Roe, H.; Andersen, M.; Scharwachter, J.; Palmer, D.; Kleinman, S.; Adamson, A.; Hirst, P.; et al. Entering into the Wide Field Adaptive Optics Era on Maunakea. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.08169v3 2019.

- Peters, U.; Chin-Yee, B. Generalization Bias in Large Language Model Summarization of Scientific Research. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, L.; Liu, W.; Mao, W.; Zhang, H. CSL: A Large-scale Chinese Scientific Literature Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, COLING 2022, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, October 12-17, 2022. International Committee on Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 3917–3923.

- Henning, S.; Macher, N.; Grünewald, S.; Friedrich, A. MiST: a Large-Scale Annotated Resource and Neural Models for Functions of Modal Verbs in English Scientific Text. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 7-11, 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1305–1324. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.; Dagdelen, J.; Walker, N.; Lee, S.; Rosen, A.S.; Ceder, G.; Persson, K.A.; Jain, A. Structured information extraction from complex scientific text with fine-tuned large language models. CoRR 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Feng, J.; Li, G.; Province, M.A.; Payne, P.R.O.; Chen, Y.; Li, F. Large Language Models Meet Graph Neural Networks for Text-Numeric Graph Reasoning. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.; Verma, B.; Hennig, L. Full-Text Argumentation Mining on Scientific Publications. CoRR 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarella, V.; Gamero-Salinas, J.C.; Consoli, S. A Few-Shot Approach for Relation Extraction Domain Adaptation using Large Language Models. CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Long, G.; Wang, X.; Xu, X. Unsupervised Knowledge Graph Construction and Event-centric Knowledge Infusion for Scientific NLI. CoRR 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, L.; Shen, J. Improving Medical Large Vision-Language Models with Abnormal-Aware Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01377 2025.

- Wang, Q.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y. Memorymamba: Memory-augmented state space model for defect recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.03673 2024.

- Wang, G.; Sun, Z.; Gong, Z.; Ye, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Q.; Hao, D. Do Advanced Language Models Eliminate the Need for Prompt Engineering in Software Engineering? CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Tang, C.; Mohati, T.; Nayebi, M.; Wang, S.; Hemmati, H. Prompt Engineering or Fine-Tuning: An Empirical Assessment of LLMs for Code. In Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, MSR@ICSE 2025, Ottawa, ON, Canada, April 28-29, 2025. IEEE, 2025, pp. 490–502. [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Qing, P.; Yang, D.; Wang, N.; Lei, Y.; Lu, H.; Lin, X.; Li, D. Prompt Space Optimizing Few-shot Reasoning Success with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, Mexico City, Mexico, June 16-21, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 1836–1862. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08734 2023.

- Amatriain, X. Prompt Design and Engineering: Introduction and Advanced Methods. CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Bing, L. Evolving Prompts In-Context: An Open-ended, Self-replicating Perspective. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Li, Y. A Practical Survey on Zero-Shot Prompt Design for In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, RANLP 2023, Varna, Bulgaria, 4-6 September 2023. INCOMA Ltd., Shoumen, Bulgaria, 2023, pp. 641–647.

- Austin, D.; Chartock, E. GRAD-SUM: Leveraging Gradient Summarization for Optimal Prompt Engineering. CoRR 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Jafari, M.; Dehbashi, H.R.; Taghavi, Z.S.; Sabokrou, M.; Rohban, M.H. Killing it with Zero-Shot: Adversarially Robust Novelty Detection. CoRR 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).