Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Case Management

2.1.1. Business Artifacts

2.2. CMMN

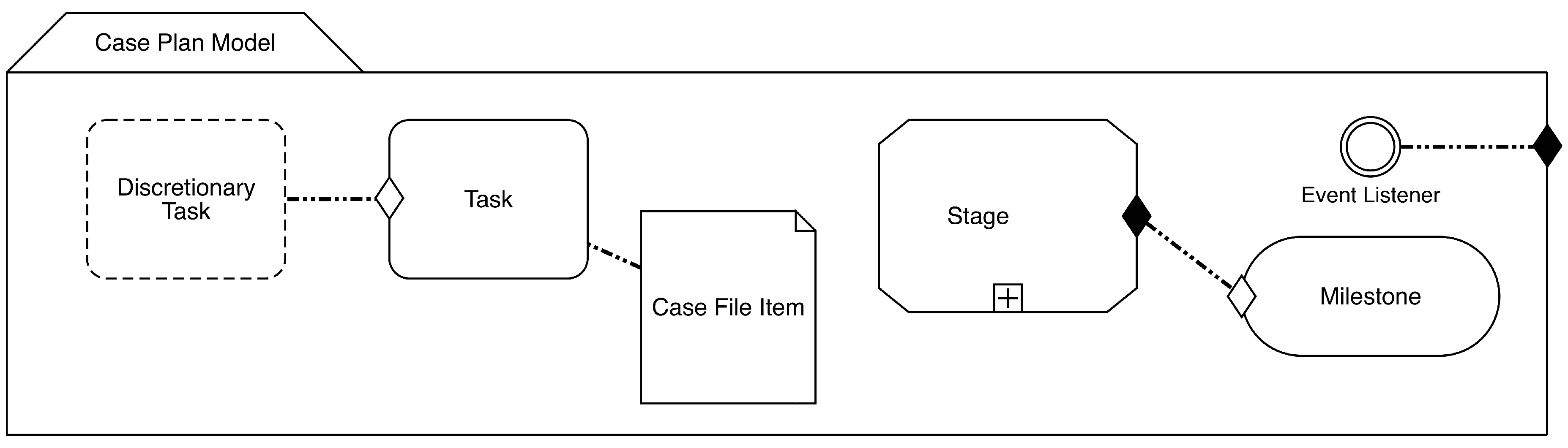

- Case Plan Model is the outermost element, within which the whole case is presented and defined.

- Task is a central element that defines a single action, a unit of work, that needs to be performed. There are different types of task: Non-Blocking Human Task (i.e. Manual Task), Blocking Human Task (i.e. User Task), Case Task, Process Task and Decision Task.

- Case File Item is an element that defines data (e.g. document, file) required for case processing.

- Stage may be considered as an "episode" or a "phase" of one case. Elements, like Tasks with Connectors, can be united within one Stage element.

- Milestone represents an achievable target, defined to enable evaluation of progress of the case.

- Event Listeners is an element that waits for an event in a case, to trigger other elements, like Tasks or Stages. There are two different types of Event Listeners: Timer Event Listener and User Event Listener.

- Sentry (Sentries) is a combination of an "event and/or condition". It is not a stand-alone element, it requires to be part of Case Plan Model, Stage, Task or Milestone. It is graphically represented with rhombus: Entry Criterion (for entry condition) with white rhombus and Exit Criterion (for exit condition) with black rhombus (Figure 1).

- Connectors can be used to visualise dependencies between elements but do not have associated execution semantics.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Questions

- 1.

- (RQ 1) What are the reported advantages and disadvantages of CMMN?

- 2.

- (RQ 2) What extensions, upgrades or improvements for the CMMN exist?

- 3.

- (RQ 3) Is CMMN used in practice?

3.2. Search String and Searched Space

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Search Process and Evaluation

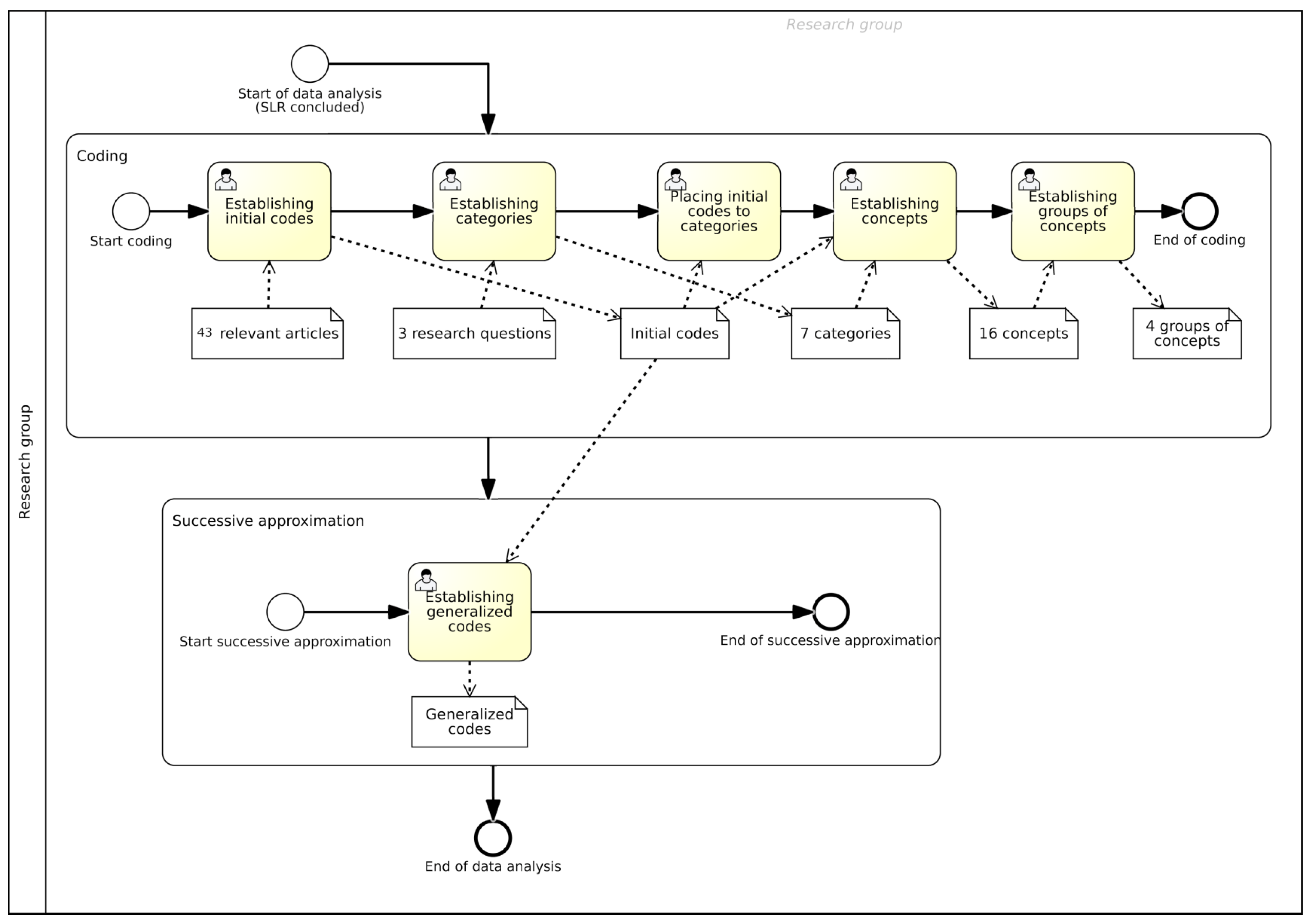

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Outcomes and Interpretation

4.1. Analysis of All Initial Articles

4.2. Analysis and Synthesis of Relevant Articles

4.3. Answers of Research Questions

4.3.1. RQ 1: What Are the Reported Advantages and Disadvantages of CMMN?

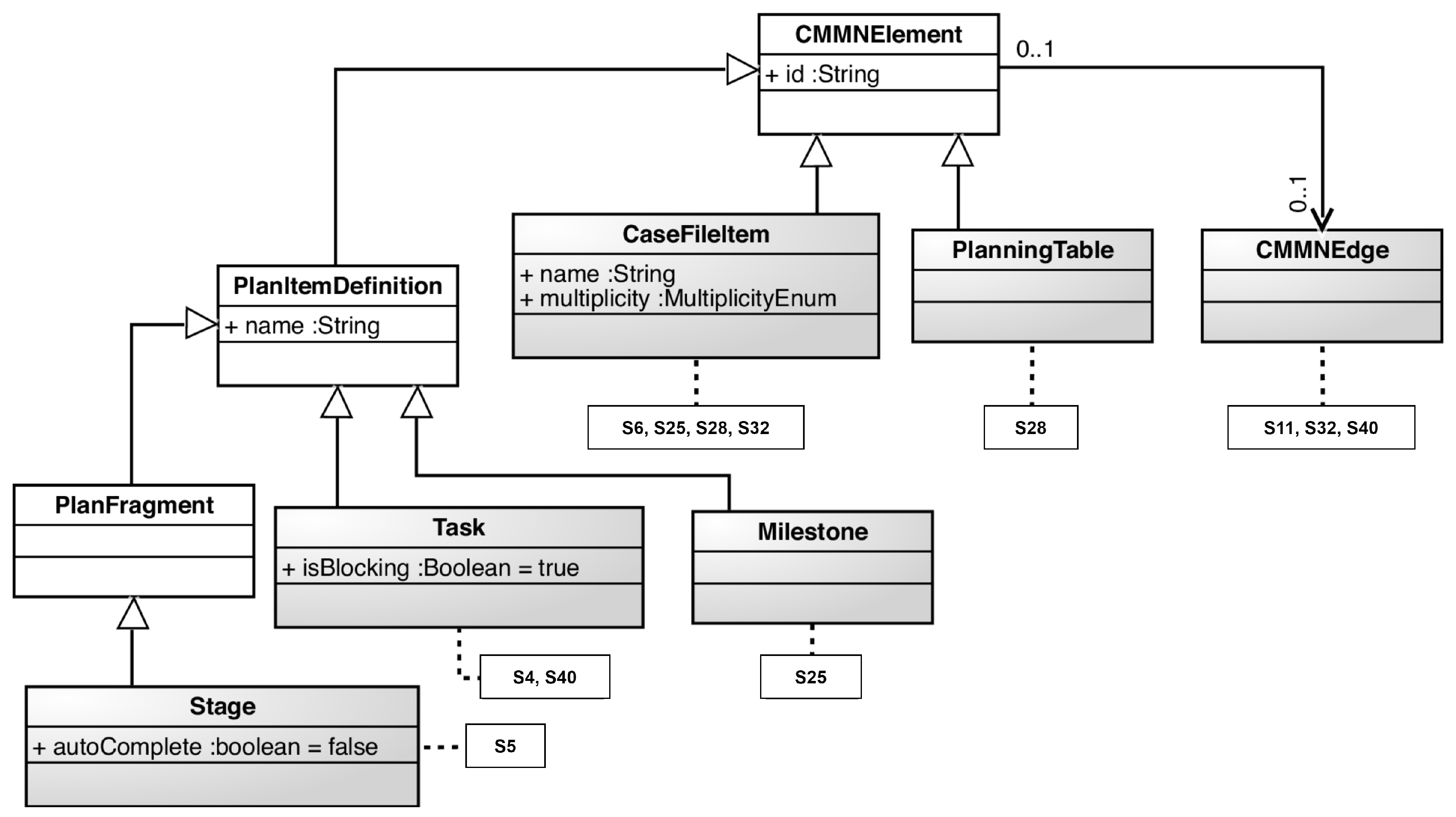

4.3.2. RQ 2: What Extensions, Upgrades or Improvements for the CMMN Exist?

4.3.3. RQ 3: Is CMMN Used in Practice?

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Future Work

References

- Dumas, M.; La Rosa, M.; Mendling, J.; Reijers, H.A. Fundamentals of Business Process Management, 2 ed; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, C.M. Fifth Generation Management: Co-creating Through Virtual Enterprising, Dynamic Teaming, and Knowledge Networking, 2 ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, D.; Hinterholzer, S.; Kubovy, J.; Küng, J. Business Process Management for Knowledge Work: Considerations on Current Needs, Basic Concepts and Models. In Proceedings of the ERP Future 2013 Conference, Vienna, Austria; 2014; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T. Thinking for A Living: How to Get Better Performance and Results from Knowledge Workers; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, J.; Rücker, B. Real-Life BPMN: With introductions to CMMN and DMN, 3 ed.; Createspace Independent Publishing Platform: Charleston, SC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van der Aalst, W.; Weske, M.; Grünbauer, D. Case Handling: A New Paradigm For Business Process Support. Data Knowl. Eng. 2005, 53, 129–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocbek, M.; Jošt, G.; Heričko, M.; Polančič, G. Business Process Model and Notation: The Current State of Affairs. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2015, 12, 509–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.A.; Lotriet, H.; Van Der Poll, J.A. Measuring Method Complexity of the Case Management Modeling and Notation (CMMN). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Southern African Institute for Computer Scientist and Information Technologists Annual Conference 2014 on SAICSIT 2014 Empowered by Technology; 2014; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Zensen, A.; Küster, J.M. A Comparison of Flexible BPMN and CMMN in Practice: A Case Study on Component Release Processes. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC), Stockholm, Sweden; 2018; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemuth, M.; Junger, D.; Leitritz, M.; Neumann, J.; Neumuth, T.; Burgert, O. Application fields for the new Object Management Group (OMG) Standards Case Management Model and Notation (CMMN) and Decision Management Notation (DMN) in the perioperative field. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2017, 12, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMG (Object Management Group). Case Management Model and Notation 1.1 Specification. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Routis, I.; Nikolaidou, M.; Anagnostopoulos, D. Modeling Collaborative Processes with CMMN: Success or Failure? In An Experience Report. In Proceedings of the Enterprise, Business-Process and Information Systems Modeling, Tallinn, Estonia; 2018; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Allah Bukhsh, Z.; van Sinderen, M.; Sikkel, K.; Quartel, D. How to Manage and Model Unstructured Business Processes: A Proposed List of Representational Requirements. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference E-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE), Madrid, Spain; 2019; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz, M.; Schmidt, W.; Fleischmann, A.; Lederer, M. Leveraging CMMN for ACM: Examining the Applicability of a New OMG Standard for Adaptive Case Management. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Subject-Oriented Business Process Management, Kiel, Germany; 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Google Trends. Available online: https://trends.google.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Marin, M.A.; Hull, R.; Vaculín, R. Data Centric BPM and the Emerging Case Management Standard: A Short Survey. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management Workshops (BPM), Tallinn, Estonia; 2013; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson, K.D. Mastering the Unpredictable: How Adaptive Case Management Will Revolutionize the Way that Knowledge Workers Get Things Done; Meghan-Kiffer Press: Tampa, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, A.; Caswell, N. Business artifacts: An approach to operational specification. IBM Syst. J. 2003, 42, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, S.; Nandi, P.; Heath, T.; Bhaskaran, K.; Das, R. ADoc-oriented programming. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Applications and the Internet (SAINT), Orlando, FL, USA; 2003; pp. 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.; Damaggio, E.; Fournier, F.; Gupta, M.; Heath, F.T.; Hobson, S.; Linehan, M.; Maradugu, S.; Nigam, A.; Sukaviriya, P.; et al. Business artifacts with guard-stage-milestone lifecycles: managing artifact interactions with conditions and events. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on Distributed Event-based system (DEBS), New York, NY, USA; 2011; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.; Damaggio, E.; De Masellis, R.; Fournier, F.; Gupta, M.; Heath, F.T.; Hobson, S.; Linehan, M.; Maradugu, S.; Nigam, A.; et al. Introducing the Guard-Stage-Milestone Approach for Specifying Business Entity Lifecycles. In Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop Web Services and Formal Methods (WS-FM), Hoboken, NJ, USA; 2011; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kocbek Bule, M.; Polančič, G.; Huber, J.; Jošt, G. Semiotic clarity of Case Management Model and Notation (CMMN). Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2019, 66, 103354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Aalst, W.; Pesic, M.; Schonenberg, H. Declarative workflows: Balancing between flexibility and support. Comp. Sci. Res. Dev. 2009, 23, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.A.; Charters, S. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report EBSE 2007-001; School of Computer Science and Mathematics, Keele University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MIT License. Parsifal. Available online: https://parsif.al (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- ACM. ACM Digital Library. Available online: https://dl.acm.org (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- IEEE. IEEE Xplore Digital Library. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Clarivate. Web of Science. Available online: https://apps.webofknowledge.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Elsevier. ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Elsevier. Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Springer Nature. SpringerLink. Available online: https://link.springer.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Benzarti, I.; Mili, H.; de Carvalho, R. Modeling and Personalising the Customer Journey: The Case for Case Management. In Proceedings of the 25th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC), Gold Coast, Australia; 2021; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, G. Tasks and assignments in case management models. Procedia CS 2016, 100, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, G. Extending CMMN with entity life cycles. Procedia CS 2017, 121, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bule, M.; Polančič, G. Extending CMMN for Effective Management of Data in Knowledge-Intensive Processes. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management: Blockchain, Robotic Process Automation, Central and Eastern European, Educators and Industry Forum (BPM), Krakow, Poland; 2024; pp. 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, Renata Medeiros; Mili, H.; Gonzalez-Huerta, J.; Boubaker, A.; Leshob, A. Comparing ConDec to CMMN - Towards a Common Language for Flexible Processes. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development (MODELSWARD), Rome, Italy; 2016; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, Renata Medeiros.; Boubaker, A.; Gonzalez-Huerta, J.; Mili, H.; Ringuette, S.; Charif, Y. On the Analysis of CMMN Expressiveness: Revisiting Workflow Patterns. In Proceedings of the 20th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop (EDOCW), Vienna, Austria; 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, F.; Navascues, N.; Calegari, D.; Delgado, A. CMMN-Based Modeling and Customization of Declarative Business Process Families. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management Forum (BPM), Krakow, Poland; 2024; pp. 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, F.A. Next-Generation Business Process Management (BPM). In Building the Agile Enterprise, 2 ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; chapter 4; pp. 115–154. [Google Scholar]

- Czepa, C.; Tran, H.; Zdun, U.; Tran, T.; Weiss, E.; Ruhsam, C. Lightweight Approach for Seamless Modeling of Process Flows in Case Management Models. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC), Marrakech, Morocco; 2017; pp. 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, T.; Gonçalves, D.; Vieira, R.; Proença, D.; Borbinha, J. A Case Management Approach to Risk Management. In Proceedings of the Business Modeling and Software Design, Lisbon, Portugal; 2019; pp. 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- van Gaal, S.; Alimohammadi, A.; Karim, M.; Zhang, W.; Sutherland, J. Investigation of treatment delay in a complex healthcare process using physician insurance claims data: an application to symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. BMC Health. Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lopez, F.; Pufahl, L. A Landscape for Case Models. In Proceedings of the Enterprise, Business-Process and Information Systems Modeling, Rome, Italy; 2019; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, N.; Kirchner, K.; Weske, M. Modeling and Monitoring Variability in Hospital Treatments: A Scenario Using CMMN. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management Workshops (BPM), Eindhoven, The Netherlands; 2015; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, J.; Pufahl, L.; Weber, I. A Systematic Comparison of Case Management Languages. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management Workshops (BPM), Münster, Germany; 2022; pp. 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali, A. Evaluating Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use of CMMN and DCR. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference Business Process Modeling, Development and Support (BPMDS), Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 2021; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali, A. Evaluating user acceptance of knowledge-intensive business process modeling languages. Softw. Syst. Model. 2023, 22, 1803–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Junger, D.; Just, E.; Brandenburg, J.M.; Wagner, M.; Schaumann, K.; Klenzner, T.; Burgert, O. Toward an interoperable, intraoperative situation recognition system via process modeling, execution, and control using the standards BPMN and CMMN. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2024, 19, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lantow, B. Adaptive Case Management - A Review of Method Support. In Proceedings of the The Practice of Enterprise Modeling, Vienna, Austria; 2018; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, M.A.; Lotriet, H.; Van Der Poll, J.A. Metrics for the Case Management Modeling and Notation (CMMN) Specification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Research Conference on South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marrella, A.; Mecella, M.; Pernici, B.; Plebani, P. A design-time data-centric maturity model for assessing resilience in multi-party business processes. Inf. Syst. 2019, 86, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, J.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Xie, G. Embracing case management for computerization of care pathways. Stud. Health. Technol. Inform. 2014, 205, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milani, F.; García-Bañuelos, L.; Filipova, S.; Markovska, M. Modelling blockchain-based business processes: a comparative analysis of BPMN vs CMMN. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2021, 27, 638–657. [Google Scholar]

- Nešković, S.; Kirchner, K. Using Context Information and CMMN to Model Knowledge-Intensive Business Processes. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Society and Technology (ICIST), Kopaonik, Serbia; 2016; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidou, M.; Koukoumtzis, S.; Routis, I.; Bardaki, C. Evaluating CMMN execution capabilities: An empirical assessment based on a Smart Farming case study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD), Marrakech, Morocco; 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nova Arévalo, N.; González, R. A Sociomaterial Design Process Modelling Technique for Knowledge Management Systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk Yurt, Z.; Eshuis, R.; Wilbik, A.; Vanderfeesten, I. Guidance for goal achievement in knowledge-intensive processes using intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 260, 125417. [Google Scholar]

- Plebani, P.; Marrella, A.; Mecella, M.; Mizmizi, M.; Pernici, B. Multi-party Business Process Resilience By-Design: A Data-Centric Perspective. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference Advanced Information Systems Engineering (CAiSE), Essen, Germany; 2017; pp. 110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Routis, I.; Nikolaidou, M.; Anagnostopoulos, D. Empirical evaluation of CMMN models: a collaborative process case study. Softw. Syst. Model. 2020, 19, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Routis, I.; Bardaki, C.; Dede, G.; Nikolaidou, M.; Kamalakis, T.; Anagnostopoulos, D. CMMN evaluation: the modelers’ perceptions of the main notation elements. Softw. Syst. Model. 2021, 20, 2089–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Routis, I.; Bardaki, C.; Nikolaidou, M.; Dede, G.; Anagnostopoulos, D. Exploring CMMN applicability to knowledge-intensive process modeling: An empirical evaluation by modelers. Knowl. Process Manag. 2023, 30, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Herrera, M.P.; Sánchez Díaz, J. Improving Emergency Response through Business Process, Case Management, and Decision Models. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), Valencia, Spain; 2019; pp. 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrah, A.; Al-Mashari, M. Modelling emergency response process using case management model and notation. IET Softw. 2017, 11, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Slaats, T. Declarative and Hybrid Process Discovery: Recent Advances and Open Challenges. J. Data Semant. 2020, 9, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sprovieri, D.; Vogler, S. Run-Time Composition of Partly Structured Business Processes using Heuristic Planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Enterprise Systems (ES), Basel, Switzerland; 2015; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sprovieri, D.; Diaz, D.; Mazo, R.; Hinkelmann, K. Run-time Planning of Case-based Business Processes. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), Grenoble, France; 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7 ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, Essex, UK,, 2014; pp. 393–490. [Google Scholar]

- Zarour, K.; Benmerzoug, D.; Guermouche, N.; Drira, K. A systematic literature review on BPMN extensions. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2020, 26, 1473–1503. [Google Scholar]

- De Giacomo, G.; Dumas, M.; Maggi, F.; Montali, M. Declarative Process Modeling in BPMN. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference Advanced Information Systems Engineering (CAiSE) 2015, Stockholm, Sweden; 2015; pp. 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Schützenmeier, N.; Käppel, M.; Ackermann, L.; Jablonski, S.; Petter, S. Automaton-based comparison of Declare process models. Softw. Syst. Model. 2023, 22, 667–685. [Google Scholar]

- ProM. Process Mining Workbench. Available online: https://promtools.org (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Pesic, M.; Schonenberg, H.; van der Aalst, W. DECLARE: Full Support for Loosely-Structured Processes. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC), Annapolis, MD, USA; 2007; pp. 287–287. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, T.; Mukkamala, R. Declarative event-based workflow as distributed dynamic condition response graphs. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Programming Language Approaches to Concurrency and Communication-cEntric Software (PLACES), Pathos, Cyprus; 2011; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- DCR Solutions. DCR Solutions. Available online: https://dcrsolutions.net (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- KMD. Going from a DCR Graph to a business process in WorkZone. Available online: https://www.kmd.net/en/insights/going-from-a-dcr-graph-to-a-business-process-in-workzone (accessed on 14 February 2025).

| Criteria | Answers |

| Population | Business analysts, researchers |

| Intervention | CMMN |

| Comparison | Where applicable, compared to BPMN |

| Outcomes | Insight into advantages, disadvantages, extensions, upgrades or improvements and practical use of CMMN |

| Context | All available, existing scientific articles |

| Attribute | Possible values |

| Basic information | |

| Title | - |

| Authors | - |

| Source | journal title, conference name, book title |

| Type of source | journal, conference, book chapter, thesis |

| Year of publication | 2014 - 2024 |

| Researchers | academics, business people, both |

| Domain | general article OR article about extensions OR articles about use OR articles about several notations, including CMMN |

| Analysis of content | |

| Purpose | - |

| Problem description | - |

| Proposed solution | - |

| Interpretations of results | |

| Discussions | - |

| Further work | - |

| Other | |

| Notes | - |

| Subjective assessment | excellent, very good, good, poor, very bad |

| Input | Pre | First | Second | Third | |

| ACM | 151 | 31 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| IEEE | 199 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| WoS | 91 | 52 | 21 | 18 | 9 |

| SD | 14 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Sc | 125 | 61 | 34 | 27 | 19 |

| SL | 362 | 50 | 15 | 12 | 9 |

| Total | 942 | 226 | 82 | 68 | 43 |

| # | Ref. | Author(s) |

| S1 | [13] | Allah Bukhsh et al. |

| S2 | [3] | Auer et al. |

| S3 | [32] | Benzarti et al. |

| S4 | [33] | Bruno |

| S5 | [34] | Bruno |

| S6 | [35] | Bule and Polančič |

| S7 | [36] | Carvalho et al. |

| S8 | [37] | Carvalho et al. |

| S9 | [38] | Castellanos et al. |

| S10 | [39] | Fred A. Cummins |

| S11 | [40] | Czepa et al. |

| S12 | [41] | Ferreira et al. |

| S13 | [42] | van Gaal et al. |

| S14 | [43] | Gonzalez-Lopez and Pufahl |

| S15 | [44] | Herzberg et al. |

| S16 | [45] | Holz et al. |

| S17 | [46] | Jalali |

| S18 | [47] | Jalali |

| S19 | [48] | Junger et al. |

| S20 | [22] | Kocbek Bule et al. |

| S21 | [14] | Kurz et al. |

| S22 | [49] | Lantow |

| S23 | [8] | Marin et al. |

| S24 | [50] | Marin et al. |

| S25 | [51] | Marrella et al. |

| S26 | [52] | Mei et al. |

| S27 | [53] | Milani et al. |

| S28 | [54] | Nešković et al. |

| S29 | [55] | Nikolaidou et al. |

| S30 | [56] | Nova Arévalo and González |

| S31 | [57] | Ozturk Yurt et al. |

| S32 | [58] | Plebani et al. |

| S33 | [12] | Routis et al. |

| S34 | [59] | Routis et al. |

| S35 | [60] | Routis et al. |

| S36 | [61] | Routis et al. |

| S37 | [62] | Ruiz Herrera and Sánchez Díaz |

| S38 | [63] | Shahrah and Al-Mashari |

| S39 | [64] | Slaats |

| S40 | [65] | Sprovieri and Vogler |

| S41 | [66] | Sprovieri et al. |

| S42 | [10] | Wiemuth et al. |

| S43 | [9] | Zensen and Küster |

| Groups of concepts | Concepts |

| Syntax | Elements, Control-flow, Data, Execution, Progress in process, Roles, Metamodel |

| Quality characteristics | Applicability, Complexity, Expressibility, Simplicity, Understandability |

| Declarative aspect | Knowledge workers, Non-routine work |

| Experiences in use | Companions, Vendors |

| RQ 1.1 | RQ 1.2 | RQ 2 | RQ 3 | ||||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | ||

| S1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| S2 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S3 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| S6 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S7 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S8 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S10 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | ||

| S11 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S12 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S13 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S14 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S15 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S17 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| S19 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S20 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S21 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S22 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| S24 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S26 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S27 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S28 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S29 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S30 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S31 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S32 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| S33 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S34 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S35 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| S36 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S37 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S38 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| S39 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S40 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S41 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| S42 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| S43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).