Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the factors influencing dietary diversity of 24-hour meals among primary school adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.Design: A cross-sectional study was conducted.Setting: Public primary schools in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.Participants: A total of 293 students were selected through simple random sampling, ensuring a representative sample of the adolescent population.Outcome Measure (s): Dietary diversity was assessed using the Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) 12 food group categories. The Individual Dietary Diversity Score (IDDS) was calculated to quantify dietary diversity.Analysis: Bivariable and multivariable analyses were performed to identify associations between dietary diversity and potential influencing factors. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, with significance set at P < 0.05.Results: The average Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) for school meals was 3.45 (±1.16), while for outside-school meals, it was 3.59 (±1.13). The proportion of students with adequate dietary diversity was 52.24% for within-school meals and 56.68% for outside-school meals. Significant factors influencing dietary diversity included higher family income (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.574-4.877), higher education level of parents (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI = 1.358-13.44), smaller family size (AOR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.02-6.702), and medium-sized family (AOR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.199-4.88).Conclusions and implications: Promoting dietary diversity among adolescents is crucial for fostering healthier eating habits and improving nutritional outcomes. Key factors influencing dietary diversity include family income, parental education, and family size. Interventions should focus on enhancing food access, addressing income disparities, providing educational resources on nutrition, and collaborating with local food suppliers. Prioritizing dietary diversity in school feeding programs can significantly improve health outcomes and establish lifelong healthy eating habits. Comprehensive strategies involving schools, families, community stakeholders, and policymakers are essential for effective implementation. Future research should evaluate the long-term impacts of these interventions on dietary diversity and overall health outcomes among adolescents.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Setting, Design and Period

Sampling Procedure

Sample Size Determination

Source and Study Population

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

Dietary Assessment and Data Collection

Quality Assurance

Ethical Standards Disclosure

Data Analysis

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

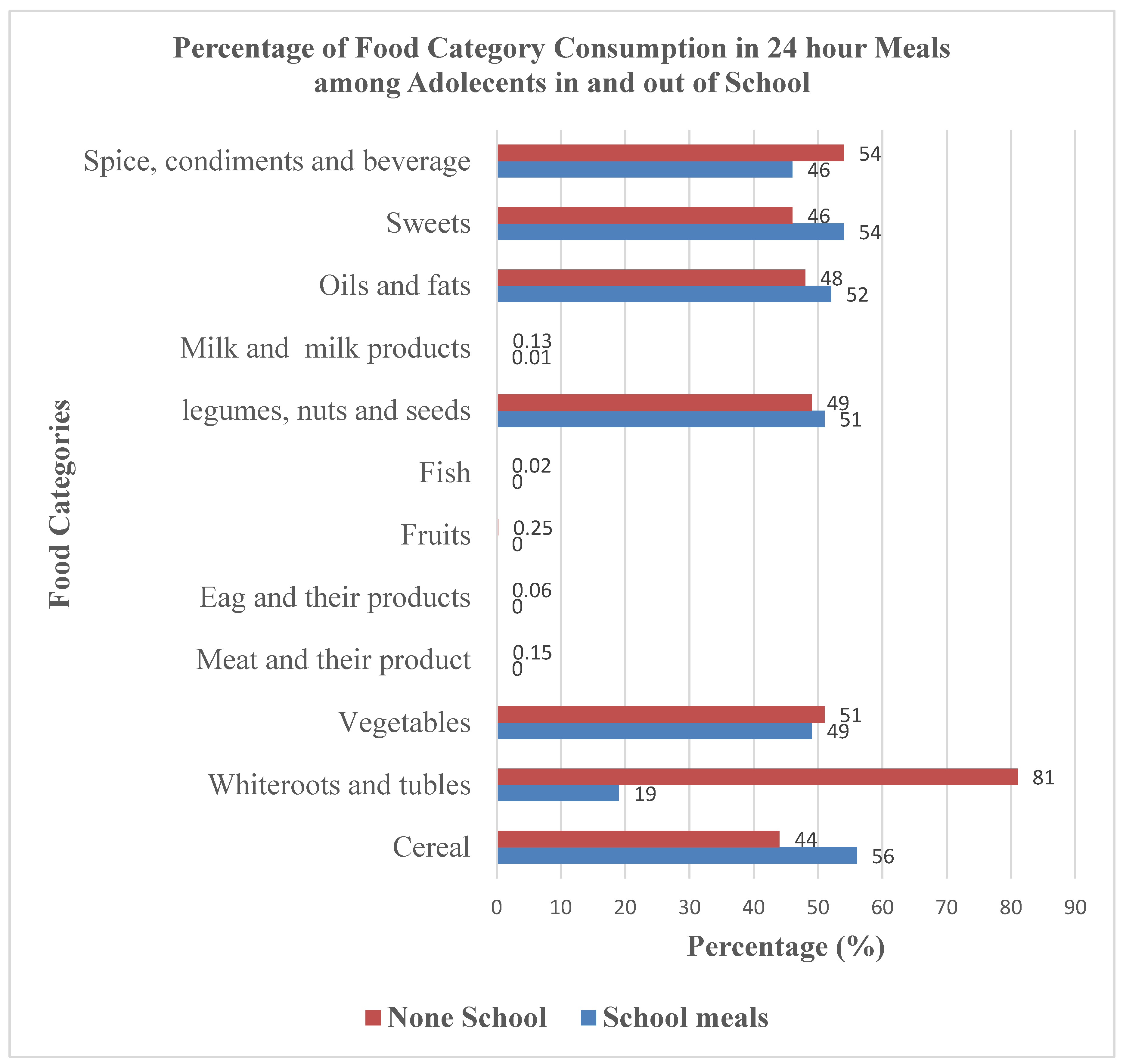

Comparing Food Category Consumption: School Meals Versus Meals Outside of School Among Adolescents

Dietary Diversity Score of School Meals and Out-of-School Meals

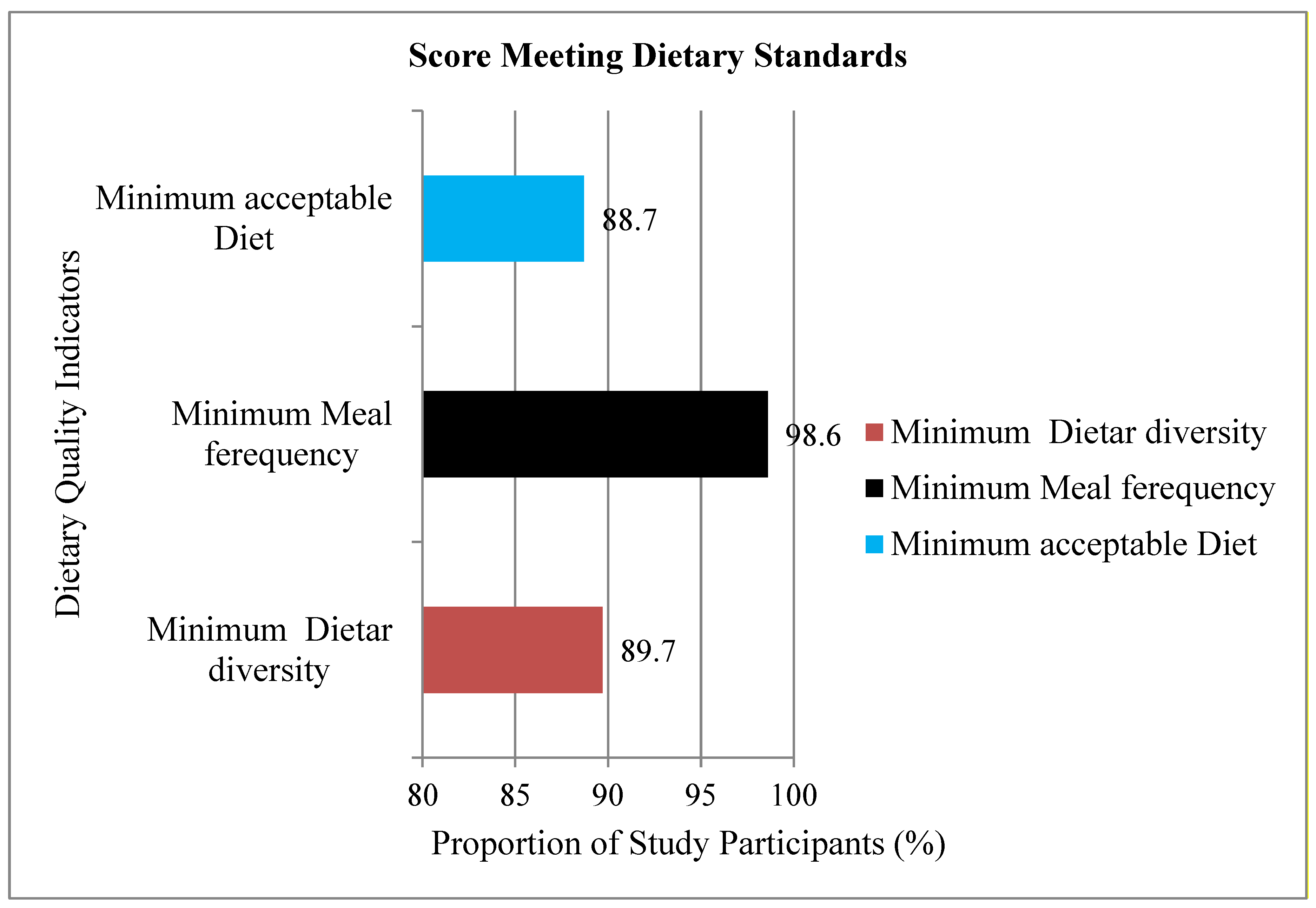

Compliance with Minimum Dietary Diversity, Minimum Meal Frequency, and Minimum Acceptable Diet

Regression Analysis of Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) for 24-Hour Meals

| Independent Variables | Factors Associated with Dietary Diversity Score of 24-Hour Meals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | (95% CI) | p-value | AOR | p-value | (95% CI) | |

| Sex of adolescence(Reference: Female) | 1 | |||||

| Male | 0.90 | 0.44,1.87 | 0.78 | 0.987 | 0.973 | -.681,0.87 |

| Gender of the household head (reference: female) | 1 | . | ||||

| Male | 1.05 | 0.51,2.15 | 0.547 | 1.041 | 0.936 | -1.07, 1.01 |

| Marital status of the household head (reference: widowed) | 1 | . | ||||

| Divorced | 2.321 | .512,10.5 | 0.275 | 2.154 | 0.338 | -.0.84, 2.5 |

| Married | 1.236 | .438,3.48 | 0.688 | 1.462 | 0.568 | -1.14, 1.6 |

| Unmarried | 1.964 | .205,18.77 | 0.558 | 1.886 | 0.598 | -2.2, 2.7 |

| Educational Status (reference: illiterates) | 1 | . | ||||

| Secondary | 0.955 | .179, 5.08 | 0.957 | 0.862 | 0.873 | -1.5, 2.45 |

| College and above | 0.611 | 0.126, 2.97 | 0.542 | 0.466 | 0.408 | -2.2, 1.7 |

| Occupation (reference: Unemployed) |

1 | . | ||||

| Employed | 0.989 | 0.44, 2.22 | 0.979 | 1.03 | 0.948 | -.599, 1.47 |

| Family income (Reference:2000-5000) | 1 | . | ||||

| <2000 | 1.2 | 0.46, 3.12 | 0.709 | 1.104 | 0.851 | -.854, 1.31 |

| >5000 | 2.495 | 1.11, 5.59 | 0.026** | 2.485 | 0.035** | 0.263, 2.1 |

| Family size Reference (>6) |

1 | |||||

| 1-3 | 0.406 | 0.12,1.4 | 0.154 | 2.146 | 0.744 | -2.4, 0.397 |

| 4-6 | 0.427 | 0.1,1.8 | 0.249 | 0.839 | 0.973 | -2.72, 0.49 |

Regression Analysis of Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) for out-of-School Meals

| Independent Variables | Factors Influencing the Dietary Diversity of Non-School Meals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | P-Value | [95% CI] | AOR | p-value | [95 % CI] | |

| Sex of Child: Female |

1 |

|||||

| Male | 0.904 | 0.674 | .566, 1.444 | .885 | .639 | 0.531-1.475 |

| Family head Gender Female | 1 | . | ||||

| Male | 0.99 | 0.995 | .623 , 1.60 | .628 | .179 | 0.318-1.238 |

| Marital status Widowed | 1 | |||||

| Divorced | 1.765 | .227 | .702, 4.44 | 1.207 | .713 | 0.443-3.283 |

| Married | 1.547 | .247 | .739 3.24 | 1.098 | .847 | 0.426-2.83 |

| unmarried | 1.68 | .447 | .441 6.39 | 1.292 | .731 | 0.3-5.565 |

| Education illiterate |

1 | 1 | . | |||

| Primary school | 2.559 | .053* | 0.98, 6.64 | 2.773 | .053* | 0.986-7.796 |

| Secondary school | 3.35 | .018** | 1.23, 9.12 | 3.312 | .037** | 1.077-10.19 |

| College and above | 4.94 | .002*** | 1.88 14.32 | 4.27 | .013** | 1.358-13.44 |

| Occupation unemployed | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employed | 2.30 | 0.003*** | 1.32, 4.01 | 1.88 | .047** | 1.01-3.49 |

| Family income ~2000-5000 ETB | 1 | |||||

| <2000 ETB | 0.82 | 0.573 | 0.411, 1.64 | 1.15 | .714 | 0.543-2.441 |

| >5000 ETB | 2.196 | 0.000*** | 1.13, 4.26 | 2.77 | 0.000*** | 1.574-4.877 |

| Family size (>6) |

1 | 1 | ||||

| 1-3 | 1.779 | 0.158 | 0.79, 3.96 | 2.61 | .045** | 1.02-6.702 |

| 4-6 | 1.9 | 0.051* | 0.99, 3.62 | 2.42 | .014 | 1.199-4.88 |

Discussion

Implications for Research and Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Isabirye N, Bukenya JN, Nakafeero M, Ssekamatte T, Guwatudde D, Fawzi W. Dietary diversity and associated factors among adolescents in eastern Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):4-11. [CrossRef]

- Textbook N. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, Nineteenth Edition International Edition.

- School Meals and Food Systems: Rethinking the Consequences for Climate, Environment, Biodiversity and Food Sovereignty.; 2023.

- Chakraborty T, Jayaraman R. School feeding and learning achievement : Evidence from India ’ s midday meal program. J Dev Econ. 2019;139(April):249-265. [CrossRef]

- Langford, R., Bonell, C. P., Jones, H. E., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S. M., Waters, E., Komro, K. A., Gibbs L, F., Magnus, D., & Campbell R. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online 2014. [CrossRef]

- Effects of a school feeding intervention on school attendance rates among elementary schoolchildren in rural Kenya . Nutrition. 2011;27(2):2011. [CrossRef]

- Snilstveit B, Gallagher E, Phillips D; et al. Protocol Interventions for improving learning outcomes and access to education in low- and middle- income countries : A systematic review. (September 2017).

- Abahussain NA. O riginal Article Was there a change in the body mass index of Saudi adolescent girls in Al-Khobar between 1997 and 2007 ? 2011;18(2):15-19. [CrossRef]

- Ochola S, Masibo PK iny. Dietary intake of schoolchildren and adolescents in developing countries. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64:24-40. [CrossRef]

- Aemro M, Mesele M, Birhanu Z, Atenafu A. Dietary diversity and meal frequency practices among infant and young children aged 6-23 months in Ethiopia: A secondary analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2011. J Nutr Metab. 2013;2013. [CrossRef]

- Ali D, Saha KK, Nguyen PH; et al. Household food insecurity is associated with higher child undernutrition in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, but the effect is not mediated by child dietary diversity. J Nutr. 2013;143(12):2015-2021. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen PH, Avula R, Ruel MT; et al. Maternal and child dietary diversity are associated in bangladesh, vietnam, and ethiopia. J Nutr. 2013;143(7):1176-1183. [CrossRef]

- Beyene M, Worku AG, Wassie MM. Dietary diversity, meal frequency and associated factors among infant and young children in Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Wondafrash M, Huybregts L, Lachat C, Bouckaert KP, Kolsteren P. Dietary diversity predicts dietary quality regardless of season in 6-12-month-old infants in south-west Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(14):2485-2494. [CrossRef]

- Workicho A, Belachew T, Feyissa GT; et al. Household dietary diversity and Animal Source Food consumption in Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2011 Welfare Monitoring Survey. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):0-11. [CrossRef]

- Zerfu TA, Umeta M, Baye K. Dietary diversity during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of maternal anemia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in a prospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(6):1482-1488. [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia], ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Published online 2012:1-452.

- ICF CSAE and. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey.; 2016.

- Yisma E, Smithers LG, Lynch JW, Mol BW. Cesarean section in Ethiopia: Prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2019;32(7):1130-1135. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Nutrition in Adolescence Issues and Challenges for the Health Sector : Issues in adolescent health and development. Ganeva WHO Press. Published online 2005:1-115. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43342/9241593660_eng.pdf.

- MoE. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Education Statistics Annual Abstract (ESAA).; 2022. file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/ESAA 2014 EC (2021-22 G.C) Final.pdf%0Awebsite: www.moe.gov.et Email:.

- Gezahegn et al. City Profile: Addis Ababa.; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Oakland GB. Determining Sample Size. Univ Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611. 1953;85(3):108-113. [CrossRef]

- Destaw Z, Wencheko E, Kidane S; et al. School feeding contributed valuable dietary energy and nutrients despite suboptimal supply to school-age children and adolescents at primary schools in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nutrition. 2022;102. [CrossRef]

- Gina Kennedy, Terri Ballard and M-CD. Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity. European Union, through the EC-FAO; 2013. www.foodsec.org.

- Horsey B, Swanepoel L, Underhill S, Aliakbari J, Burkhart S. Dietary Diversity of an Adult Solomon Islands Population. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Mbwana HA, Kinabo J, Lambert C, Biesalski HK. Determinants of household dietary practices in rural Tanzania: Implications for nutrition interventions. Cogent Food Agric. 2016;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Khamis AG, Ntwenya JE, Senkoro M; et al. Association between dietary diversity with overweight and obesity: A cross-sectional study conducted among pastoralists in Monduli District in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1 January):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Gibson R. An Interactive 24-Hour Recall of Assessing the Adequacy of Iron and Zinc Intakes in Developing Countries. Vol 10.; 1989.

- Wassie MM, Gete AA, Yesuf ME, Alene GD, Belay A, Moges T. Predictors of nutritional status of Ethiopian adolescent girls: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2015;1(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Endalifer ML, Andargie G, Mohammed B, Endalifer BL. Factors associated with dietary diversity among adolescents in Woldia, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2021;7(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Belachew T, Lindstrom D, Gebremariam A; et al. Food Insecurity, Food Based Coping Strategies and Suboptimal Dietary Practices of Adolescents in Jimma Zone Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Vakili M, Abedi P, Sharifi M, Hosseini M. Dietary diversity and its related factors among adolescents: A survey in Ahvaz-Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(2):181-186. [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta A, Tessema M, Kiday H, Seid O. Examining Means of Reaching Adolescent Girls for Iron Supplementation in Tigray , Northern Ethiopia. Published online 2015:9033-9045. [CrossRef]

- M NI, Akther F, Ss SS, Nahar Q. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences Assessment of Micro Nutritional Malnutrition in an Urban Area of Bangladesh among the Adult Population on the Basis of Individual Dietary Diversity Score ( IDDS ). 2015;5(3). [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dietary diversity score in adolescents - A good indicator of the nutritional adequacy of diets: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(1):56-60.

- Korkalo L. Hidden Hunger in Adolescent Mozambican Girls : Dietary Assessment , Micronutrient Status , and Associations between Dietary Diversity and Selected Biomarkers Hidden Hunger in Adolescent Mozambican Girls : Dietary Assessment , Micronutrient Status , and As.; 2016.

- Nti CA, Brown A, Danquah A. Adolescents ’ Knowledge of Diet-Related Chronic Diseases and Dietary Practices in Ghana. 2012;2012(November):1527-1532.

- Grobler WCJ. Socio Economic Determinants of Household Dietary Diversity in a Low Income Neighbourhood in South Africa Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference. 2015;(April).

| Variable | n | % |

| Sex of adolescence | ||

| Female | 120 | 40.96 |

| Male | 173 | 59.04 |

| Gender of the household head | ||

| Female | 115 | 39.25 |

| Male | 178 | 60.75 |

| Marital status of the household head | ||

| Married | 206 | 70.31 |

| Divorced | 42 | 14.33 |

| Died | 33 | 11.26 |

| Unmarried | 12 | 4.10 |

| Educational status of the household head | ||

| Illiterate | 24 | 8.19 |

| Primary school | 115 | 39.25 |

| Secondary school | 69 | 23.55 |

| College and above | 85 | 29.01 |

| Household head occupation | ||

| Employed | 77 | 26.3 |

| Unemployed | 216 | 73.7 |

| Family monthly income (ETB) | ||

| <2000 | 48 | 16.38 |

| 2000-5000 | 100 | 34.13 |

| >5000 | 145 | 49.49 |

| Dietary Diversity Score | Meals provided within a school setting | Meals consumed outside of school | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| 1 | 6 | 2.1 | 14 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 80 | 27.3 | 76 | 26.1 |

| 3 | 54 | 18.4 | 36 | 12.4 |

| 4 | 130 | 44.4 | 116 | 39.9 |

| 5 | 21 | 7.2 | 44 | 15.1 |

| 6 | 2 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).