Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

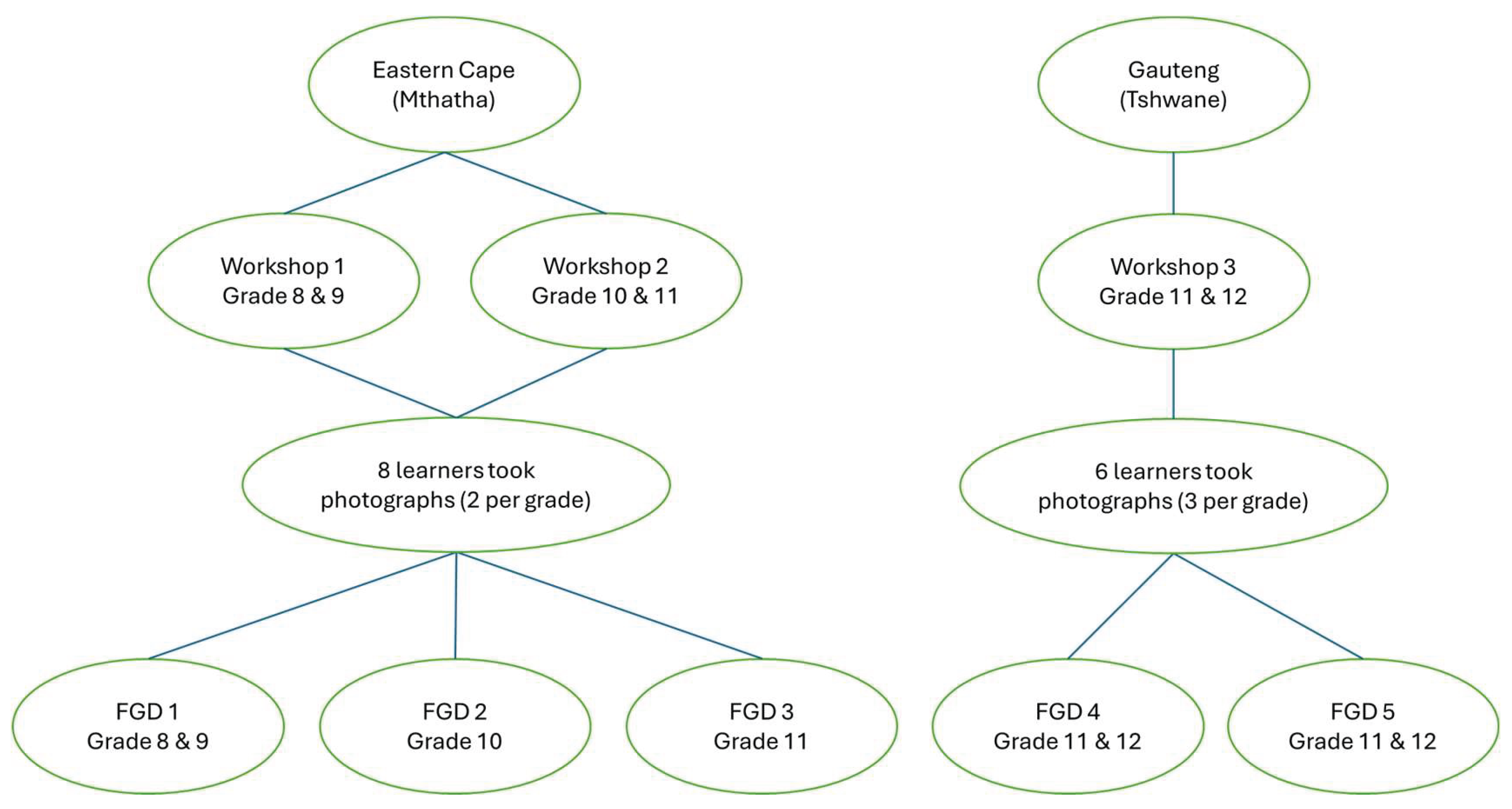

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Site

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Data Collection

3. Workshops

3.1. Photo Gathering

3.2. Focus Group Discussions

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Identifying Foods, Their Perceived Healthfulness and Frequency of Consumption

4.2. Themes of Learners’ Perceptions of the Reasons Influencing Their Food Choices

4.3. Individual Level Drivers of Adolescent Learners’ Food Choices

4.3.1. Sensory Appeal, Comfort Food and Hunger

4.3.2. Nutrition and Food Processing Knowledge

4.4. Convenience and Time Constraints

5. Socio-Cultural Drivers of Adolescent Learners’ Food Choices

5.1. Parental Influence and Familiarity with Foods

5.2. Social Status, Aspirational Food and Setting

6. Physical and Economic Environment Drivers of Adolescent Learners’ Food Choices

6.1. Physical Access

6.2. Economic Access

6.3. Hygiene and Food Safety

6.4. Proposed Solutions to make Healthier Choices

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

9. Strengths and limitations

Financial support

Authorship

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J.; et al. A Future for the World’s Children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.E.; Mason, T.B. Psychiatric Comorbidity Associated with Weight Status in 9 to 10 Year Old Children. Pediatr Obes 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Su, Q.; Li, R.; Elgar, F.J.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, D. The Association between Chronic Bullying Victimization with Weight Status and Body Self-Image: A Cross-National Study in 39 Countries. PeerJ 2018, 2018, e4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Larson, K.; Slusser, W. Associations Between Obesity and Comorbid Mental Health, Developmental, and Physical Health Conditions in a Nationally Representative Sample of US Children Aged 10 to 17. Acad Pediatr 2013, 13, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.M.; Shin, S.; Tarnopolsky, M.; Taylor, V.H. Association of Depression & Health Related Quality of Life with Body Composition in Children and Youth with Obesity. J Affect Disord 2015, 172, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.; Smith, TG.; Jewell, J.; Wardle, J.; Hammond, R.A.; Friel, S.; Thow, A.M.; Kain, J. Smart Food Policies for Obesity Prevention. The Lancet 2015, 385, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, L.M.; Andrade, E.B.; Ballonoff Suleiman, A.; Barker, M.; Beal, T.; Blum, L.S.; Demmler, K.M.; Dogra, S.; Hardy-Johnson, P.; Lahiri, A.; et al. Food Choice in Transition: Adolescent Autonomy, Agency, and the Food Environment. The Lancet 2022, 399, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjohi, M.N.; Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Asiki, G.; Holdsworth, M.; Pradeilles, R.; Langat, N.; Amugsi, D.A.; Wilunda, C.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Adolescents’ Dietary Patterns, Their Drivers and Association with Double Burden of Malnutrition in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kenya’s Urban Slums. J Health Popul Nutr 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The Nutrition Transition to a Stage of High Obesity and Noncommunicable Disease Prevalence Dominated by Ultra-Processed Foods Is Not Inevitable. Obesity Reviews 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, M.; Puppo, F.; Del Bo’, C.; Vinelli, V.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Martini, D. A Systematic Review of Worldwide Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods: Findings and Criticisms. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobstein, T.; Brinsden, H. Global Atlas on Childhood Obesity, 2019.

- Wrottesley, S.V.; Pedro, T.M.; Fall, C.H.; Norris, S.A. A Review of Adolescent Nutrition in South Africa: Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition Initiative. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020, 33, 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbach, S.; Oskorouchi, H.R.; Rogan, M.; Qaim, M. Using Google Data to Measure the Role of Big Food and Fast Food in South Africa’s Obesity Epidemic. World Dev 2021, 140, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, G.; Savona, N.; Aguiar, A.; Alaba, O.; Booley, S.; Malczyk, S.; Nwosu, E.; Knai, C.; Rutter, H.; Klepp, K.-I.; et al. Adolescents’ Perspectives on the Drivers of Obesity Using a Group Model Building Approach: A South African Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz, J.; Rosch, J.T.; Ramirez, E.; Brill, J.; Ohlhausen, M. A Review of Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents Follow-up Report. Federal Trade Commission. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, E.L.; Carpenter, C.F. Food and Beverage Marketing to Children and Youth: Trends and Issues. Media Psychol 2006, 8, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation Food Marketing Exposure and Power and Their Associations with Food-Related Attitudes, Beliefs and Behaviours: A Narrative Review. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041783 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Hermans, R.C.J.; Smit, K.; van den Broek, N.; Evenhuis, I.J.; Veldhuis, L. Adolescents’ Food Purchasing Patterns in the School Food Environment: Examining the Role of Perceived Relationship Support and Maternal Monitoring. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Aggarwal, A.; Walls, H.; Herforth, A.; Drewnowski, A.; Coates, J.; Kalamatianou, S.; Kadiyala, S. Concepts and Critical Perspectives for Food Environment Research: A Global Framework with Implications for Action in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Glob Food Sec 2018, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education and Behavior 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L. Thinking Critically about Photovoice: Achieving Empowerment and Social Change. Int J Qual Methods 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjohi, M.N.; Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Holdsworth, M.; Pradeilles, R.; Wilunda, C.; Asiki, G.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Drivers and Solutions to Unhealthy Food Consumption by Adolescents in Urban Slums in Kenya: A Qualitative Participatory Study. Public Health Nutr 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzse, A.; Goldstein, S.; Tugendhaft, A.; Norris, S.A.; Barker, M.; Hofman, K.J. The Roles of Men and Women in Maternal and Child Nutrition in Urban South Africa: A Qualitative Secondary Analysis. Matern Child Nutr 2021, 17, e13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belew, A.K.; Sisay, M.; Baffa, L.D.; Gasahw, M.; Mengistu, B.; Kassie, B.A.; Agimas, M.C.; Abriham, Z.Y.; Angaw, D.A.; Muhammad, E.A. Dietary Diversity and Its Associated Factors among Adolescent Girls in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januraga, P.P.; Izwardi, D.; Crosita, Y.; Indrayathi, P.A.; Kurniasari, E.; Sutrisna, A.; Tumilowicz, A. Qualitative Evaluation of a Social Media Campaign to Improve Healthy Food Habits among Urban Adolescent Females in Indonesia. Public Health Nutr 2020, 24, s98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandpur, N.; Neri, D.A.; Monteiro, C.; Mazur, A.; Frelut, M.L.; Boyland, E.; Weghuber, D.; Thivel, D. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption among the Paediatric Population: An Overview and Call to Action from the European Childhood Obesity Group. Ann Nutr Metab 2020, 76, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, N.; Torheim, L.E.; Castro-Díaz, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. On-Campus Food Environment, Purchase Behaviours, Preferences and Opinions in a Norwegian University Community. Public Health Nutr 2022, 25, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colozza, D. A Qualitative Exploration of Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption and Eating out Behaviours in an Indonesian Urban Food Environment. Nutr Health 2024, 30, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Laar, A.; Zotor, F.; Pradeilles, R.; Aryeetey, R.; Green, M.; Griffiths, P.; Akparibo, R.; Wanjohi, M.N.; Rousham, E.; et al. The African Urban Food Environment Framework for Creating Healthy Nutrition Policy and Interventions in Urban Africa. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, T.; Thow, A.M.; Ng, S.W.; Ostrowski, J.; Bopape, M.; Swart, E.C. A Fit-for-Purpose Nutrient Profiling Model to Underpin Food and Nutrition Policies in South Africa. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Solís, C.I.; Monterrubio-Flores, E.A.; Cediel, G.; Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Barquera, S. Trend of Ultraprocessed Product Intake Is Associated with the Double Burden of Malnutrition in Mexican Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, L.; Machado, P.; Zinöcker, M.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 1955 2020, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Davis, J.A.; Beattie, S.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Loughman, A.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.; Berk, M.; Page, R.; Marx, W.; et al. Ultraprocessed Food and Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 43 Observational Studies. Obesity Reviews 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseko, I.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Tesfay, S.; Araya, H.T.; Fezzehazion, M.; Du Plooy, C.P. African Leafy Vegetables: A Review of Status, Production and Utilization in South Africa. Sustainability 2018, Vol. 10, Page 16 2017, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.M.; Burgermaster, M.; Mamykina, L. The Use of Social Media in Nutrition Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults—A Systematic Review. Int J Med Inform 2018, 120, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Brien, A.; Omari, L.; Culpin, A.; Smith, M.; Egli, V. Bus Stops near Schools Advertising Junk Food and Sugary Drinks. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, V.; Vandevijvere, S. Changes in Retail Food Environments around Schools over 12 Years and Associations with Overweight and Obesity among Children and Adolescents in Flanders, Belgium. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, C.E.; Black, J.L.; Kent, M.P. Food and Beverage Marketing in Schools: A Review of the Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, I.; Jordan, I.; Borelli, T. Enhancing Nutrition and Cost Efficiency in Kenyan School Meals Using Neglected and Underutilized Species and Linear Programming: A Case Study from an Informal Settlement. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2025, 17, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Laurie, S.; Maduna, M.; Magudulela, T.; Muehlhoff, E. Is the School Food Environment Conducive to Healthy Eating in Poorly Resourced South African Schools? Public Health Nutr 2014, 17, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukanu, M.M.; Thow, A.M.; Delobelle, P.; McHiza, Z.J.R. School Food Environment in Urban Zambia: A Qualitative Analysis of Drivers of Adolescent Food Choices and Their Policy Implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igumbor, E.U.; Sanders, D.; Puoane, T.R.; Tsolekile, L.; Schwarz, C.; Purdy, C.; Swart, R.; Durão, S.; Hawkes, C. “Big Food,” the Consumer Food Environment, Health, and the Policy Response in South Africa. PLoS Med 2012, 9, e1001253–e1001253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, S.; Bahl, D.; Arora, M.; Tullu, F.T.; Dudeja, S.; Gupta, R. Food Environment in and around Schools and Colleges of Delhi and National Capital Region (NCR) in India. BMC Public Health 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South Africa Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act 54 of 1972) - No. R. 146 Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs; 2010; pp. 3–51;

| Food item | Healthfulness of food item as indicated by learners | Recognition and identification of the food item by learners | Frequency of consumption of food items as indicated by learners | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Unhealthy | Combination of healthy and unhealthy | Correctly identified | Incorrectly identified/ confusion identifying | Eaten often | Not eaten often | |

| Bananas | x | x | x | ||||

| Spinach | x | x | x | ||||

| Avocados | x | x | x | ||||

| Granola bar | x | x | x | ||||

| Morogo | x | x | x | ||||

| Apples | x | x | x | ||||

| Cherries | x | x | x | ||||

| Kota | x | x | x | ||||

| Pie | x | x | x | ||||

| Amagwinya (Vetkoek) | x | x | x | ||||

| Pizza | x | x | x | ||||

| Ice cream | x | x | x | ||||

| Chips/ crisps | x | x | x | ||||

| Fruit juice | x | x | x | ||||

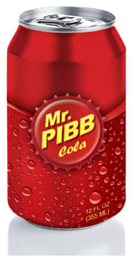

| Cool drink/ soda | x | x | x | ||||

| Marie biscuit | x | x | x | ||||

| Breakfast cereal | x | x | x | ||||

| Muesli | x | x | x | ||||

| Flavoured yoghurt | x | x | x | ||||

| Number | Foods pictures displayed to learners | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Bananas |

“My brother eats bananas every day. I think he’s addicted to bananas. My mom buys it.”(Gauteng Grade 12 learner) “I bring fruit … two fruits every day, an apple and a banana.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “…it’s healthy, but I think you should also view how much of it you take. Especially with bananas, they are very high in potassium, and sometimes that’s not very good for your body. So it is healthy because it is a fruit, but don’t [eat] excessively.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “When it comes to whether I would eat it and how often I would eat it, I live in a school hostel, so I don’t necessarily get a choice of what I eat, because it’s usually about what they give. And at the hostel, they usually give us fruit once a week, and then that’s sometimes. Sometimes they don’t give us fruit at all.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) |

| 2 |

Spinach |

“Every single way I’ve tried to eat spinach, guys, is just not appetizing.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) ‘No, it’s different taste buds. Honestly. Like we can cook it the same way. You like it, I won’t. It’s just the way it is.’ (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) It’s one of my favourite green vegetables. I only eat it when I’m at home. Since I live in the hostel, they don’t usually serve it.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “I just eat it because I have to and I was once sick because I had a lack of iron.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “If you touch someone and you feel electric static, they say if you eat spinach it stops that.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) |

| 3 |

Avocados |

“As one person who eats a lot of avocados, I can say it is very unhealthy. Because of the fat. The amount of fat that’s in it. So, maybe, no, actually no, let me say it is healthy because it is a vegetable but then again we go back to the excessiveness of eating whatever (fat).” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Because I know that avocados are high in fat, but then some people say that they’re high in the good fats, and then some people say that good fats don’t exist at all. So then I’m not sure.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Oh, she doesn’t like saying that [that Avocados are healthy] because she doesn’t like avocados.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 4 |

Granola bar |

“I don’t necessarily know why, but then people usually say that it’s healthy. And then when they’re advertising, they’ll show things like fitness and just keeping healthy and stuff.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “It’s also because the way they make the granola bars, they are processed. They have things added into them to make it more appealing. So when you taste it, you want more.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “I say unhealthy madam because, yes, nuts, raisins, all that tastes good, but the whole reason they taste nice in that form is because of the amount of sugar it has. They even put chocolate at the bottom to make it taste better, so it’s only the sugar.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) |

| 5 |

Morogo |

“It’s very healthy shame, but it’s not nice.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “No. I don’t like it. It’s in the village. It’s mostly made there.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Twice a week. In the week it’s prepared at home, and my granny only loves it” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Maybe twice a year [consumption], madam” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 6 |

Apples |

“Very nice. Especially the greener the better.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Apples are juicy.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) I don’t eat them often because they are not available [in hostel].” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 7 |

Cherries |

“I never tasted a cherry in my life.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “It [cherries] is affordable, but it depends on what our parents know.” Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “It’s freshly sourced, they’re not processed.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “The natural ones are sour. And then maraschino cherries that like they put like maybe in black forest, it’s like covered in syrup or something.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Cherries are more expensive than apples, so when you have the option which is more available for you, you rather choose the one which will cost you less.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Cherries are relatively smaller than apples, so I guess there’ll be more healthy benefits in an apple than a cherry.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) |

| 8 |

Kota (hollowed out quarter loaf of bread often filled with fries and a sauce) |

“I also think presentation-wise, it looks very appetizing compared to other healthy foods. You see nuts, who would go for nuts when you have a whole kota?” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Yes, and it’s cheaper than the healthier foods that are offered.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) There’s only one option, it’s the kota, the chips and the coke. (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “It’s the closest thing there, so why not … why go somewhere further away to get something healthy if it’s right there?” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “I don’t buy kota. I don’t. I do eat it, but I don’t buy it. Because, I don’t know, first of all, it’s not so close, and I’m always rushing somewhere, or I’m really lazy to walk.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 9 |

Pie |

“It melts my heart.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “It depends [healthfulness]. Yeah, there’s veggies [inside the pie].” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Yeah, I get those veggie pies, those are healthy.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “I want to argue. That’s healthy. Because the pastry, yeah, it’s flour and then eggs. Okay like, they can also be unhealthy but there’s also, okay, maybe it is unhealthy, but compared to other things that we’ve seen, it’s healthy.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “The vegetables. Yeah, there’s veggies [inside the pie]. And then there’s just one maybe like sausage …” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “And the meat, okay, like if steak and kidney, chicken and mushroom, there’s veggies and then there’s also a bit of meat.” |

| 10 |

Amagwinya (Vetkoek) (deep fried dough bread/ vetkoek) |

“That’s my love.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “It’s at the gate.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Hashtag hungry and broke. Because it catches you after school.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “The amount of oil it needs to cook [makes it unhealthy].” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “They sell it at the tuck shop, it’s easy to get, and on top of that, the size, the portion, it’s like, you look at it and you’re like, okay, that’s going to fill me, let me get it, and on top of that, it tastes good, so I usually get that.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “When we look at take-out, we look at it as, okay, mom’s not cooking, so we’re going to go to McD’s and then buy supper. So, we have McD’s for supper. That’s how we look at take-outs. So, it’s [Amagwinya and Kota] just available comfort food.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 11 |

Pizza |

“Since like Debonairs pizza is like a very well established brand, the name itself also promise you to give you quality.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Because my mom likes it. And my brother. And so, we buy it.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “I think it’s like the brand which Debonairs has built up from like since it was created. Since people know Debonairs pizza as, yeah, the good pizza. Unlike when you compare to let’s say, Roman’s pizza or Panarotti’s.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) It’s delicious. Not only, you know, madam, it’s Debonairs pizza.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Some of us prefer to eat veggie pizza. [Alluding to its healthy property]” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) |

| 12 |

McFlurry icecream |

“I eat ice cream every day. [Not necessarily McFlurry]” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “For me when it comes to McFlurry, I feel like the only reason why I would necessarily choose that ice cream in particular over other ice creams, is because of the name.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “I’d say ice cream is seen as like a comfort food, or any sweet treats are seen as a comfort food.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) |

| 13 |

Packaged chips/ crisps |

“Lays to be specific” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Because it’s cheap. Some of us are not financially stable, so we just buy it.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Yeah. Boredom [reason to consume it].” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Cravings [reason to consume it].” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 14 |

Packaged fruit juice |

“I’d say it’s kind of in between, I guess it kind of depends on the brand, because there are some brands which kind of offer a little bit of pureness, but then there’s others that offer like 100% artificial drinks.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “Some are sweetened juice.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Honestly, I don’t know, but I know I drink a lot of water. I try to finish a bottle of 4.5 litres of water a day.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Do we actually like water or do we not afford the juice?” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 15 |

Cooldrink/ Soda |

“There is too much acid and sugar.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Everyday [consumed]” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “The only reason the drink itself tastes good is because of the high amount of sugar the drink itself contains.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) “The acid, the taste, the aroma. Just that it’s satisfying.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) |

| 16 |

Packaged biscuits |

“[Unhealthy] because it has a lot of sugar.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Okay, like at least like four times a week [consumption].” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “These biscuits are made so that they last longer and also made with ingredients so that they are much more cheaper and quicker to get and make. So they don’t really care about how healthy it is, as when you yourself are making them from scratch at home.” (Eastern Cape Grade 8/9 learner) |

| 17 |

Breakfast cereal |

“Yeah, with plain yogurt and fruit. And then there are those people that eat it with sugar, and especially with like Coco Pops or something, there are people that add the additional sugar.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) I’m not sure, but I think it’s because it is processed. It’s not directly, I don’t know whether they used natural products to make it or not. (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “Yeah, with plain yogurt and fruit. And then there are those people that eat it with sugar, and especially with like Coco Pops or something, there are people that add the additional sugar.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Every day [consumption].” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 18 |

Muesli |

“Doesn’t that have like sugar in it.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “Because the muesli that I eat has actually got sugar in it. I actually read the box because I always ask myself, why does it taste so sweet regardless of what you add to it? Because I’ve done a comparison where I used pure oats and I added yogurt to it, and then I added yogurt to muesli, and I tasted the difference. It tastes less plain but it’s more filling, it makes you more full. And then the other one tastes sweeter regardless of what you add to it.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) |

| 19 |

Flavoured yoghurt |

“I prefer plain yoghurt. It’s [flavoured yoghurt] less healthy because it has more additives and flavourings and colourants and all that.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “My mother say they’re healthy because most of the yogurt contains a lot of minerals that are healthy for your body and your brain too.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “I like reading packages, especially of these things. Most yogurts that have flavours like strawberry, mango, they are sweetened. It’s not only the fruit that goes in, but like additional sugar also goes in to make it sweeter and some oils.” (Eastern Cape Grade 11 learner) “I’m saying it depends because they are ... I don’t know if I should say they are healthy, the ones that are dairy free and fat free and whatever, but then it is, I don’t know if it’s stats or what, but they are like plain yogurt that is considered to be healthy than the actual flavoured ones.” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) “It’s less healthy because it has more additives and flavourings and colourants and all that.” .” (Gauteng Grade 11/12 learner) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).