Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

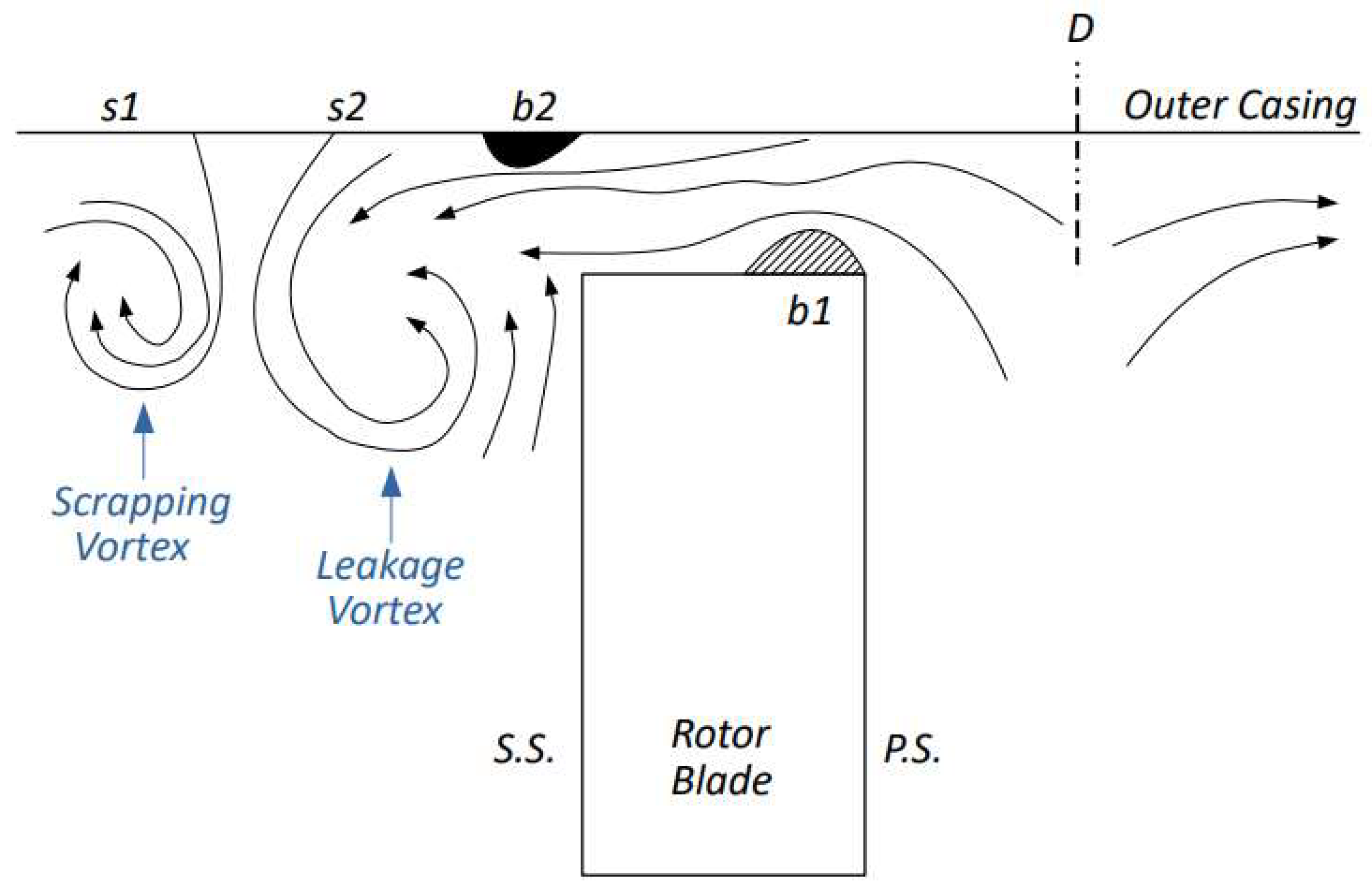

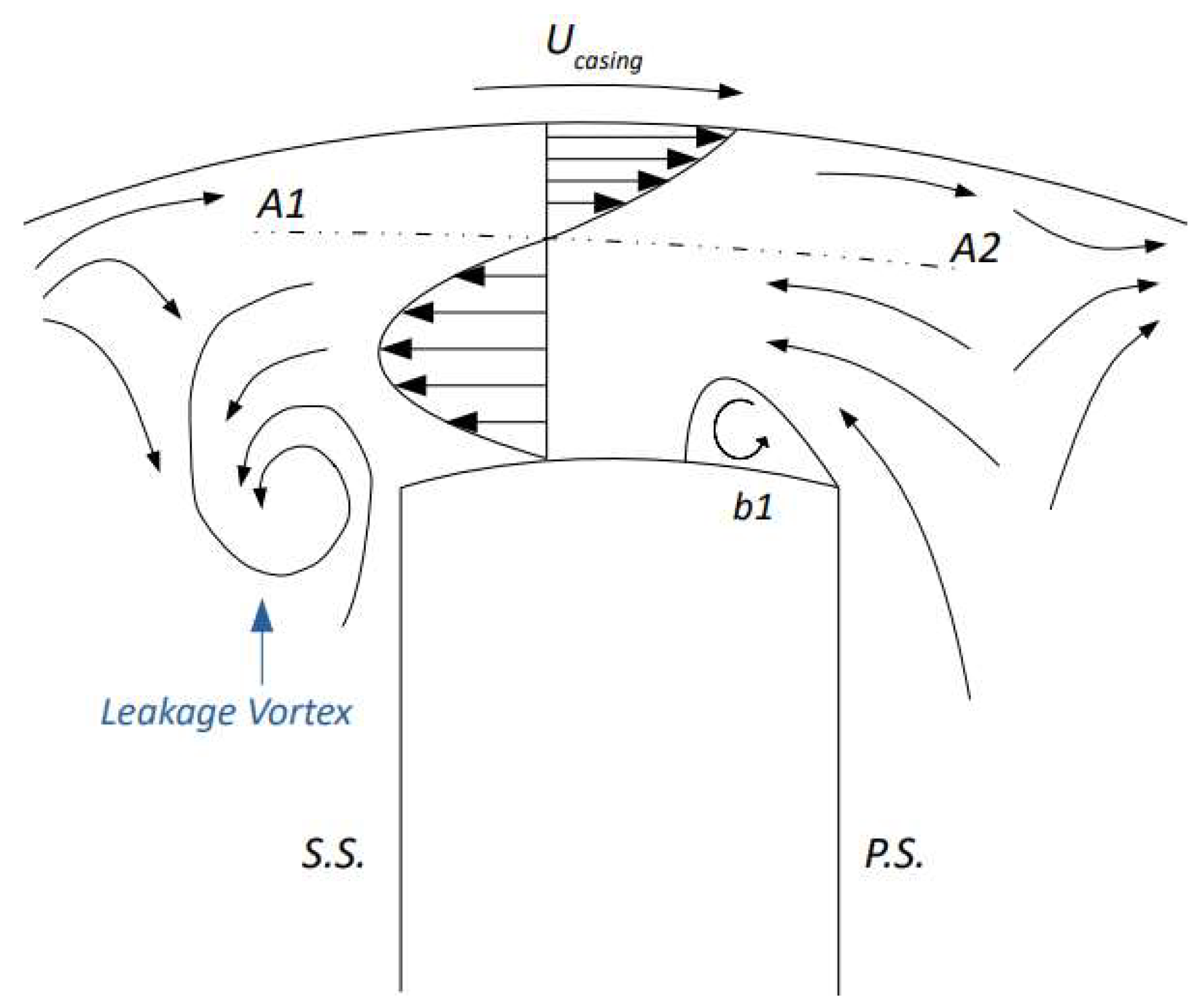

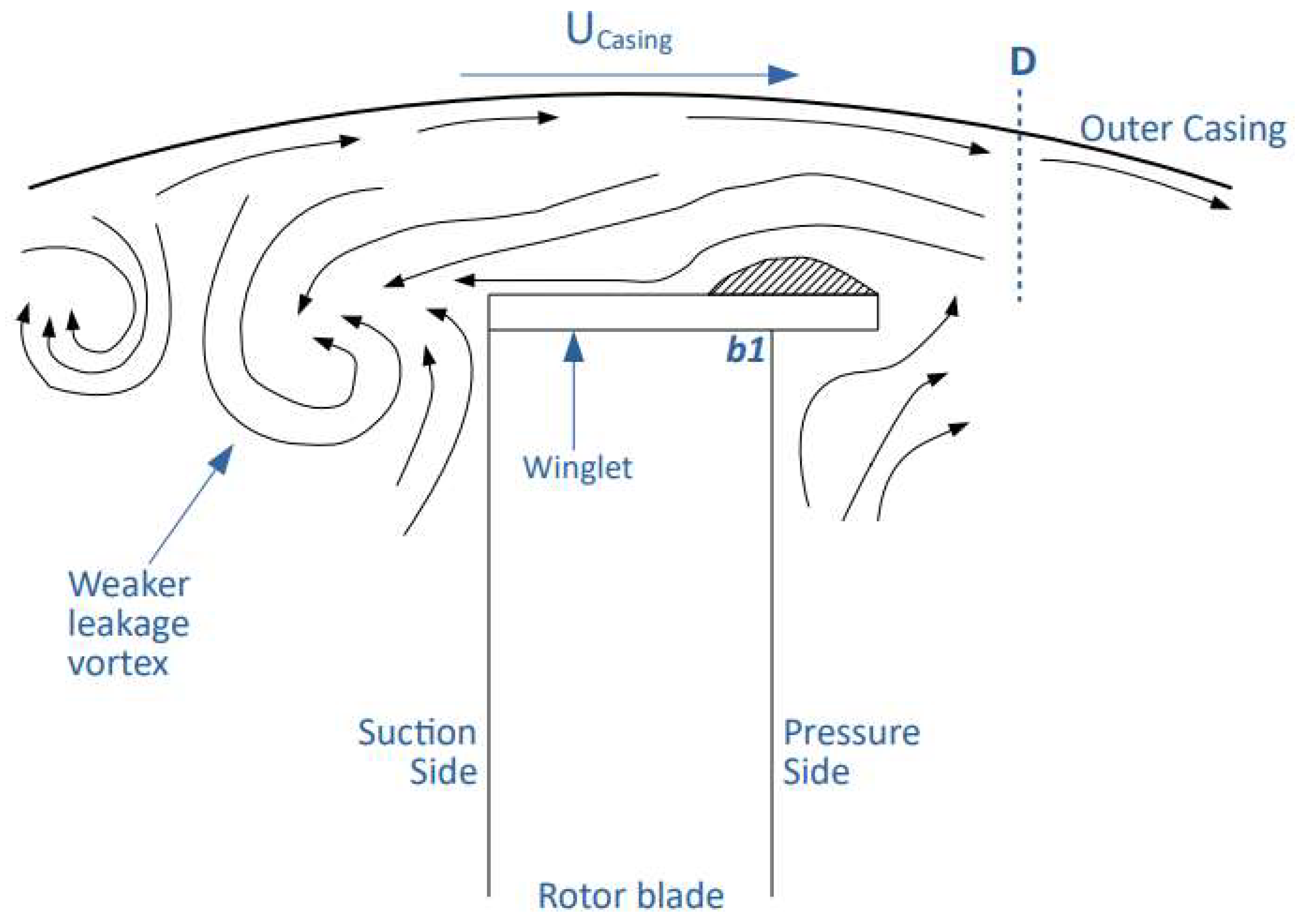

2. Tip Leakage Effects

2.1. Leakage Behavior

2.2. Cavitation

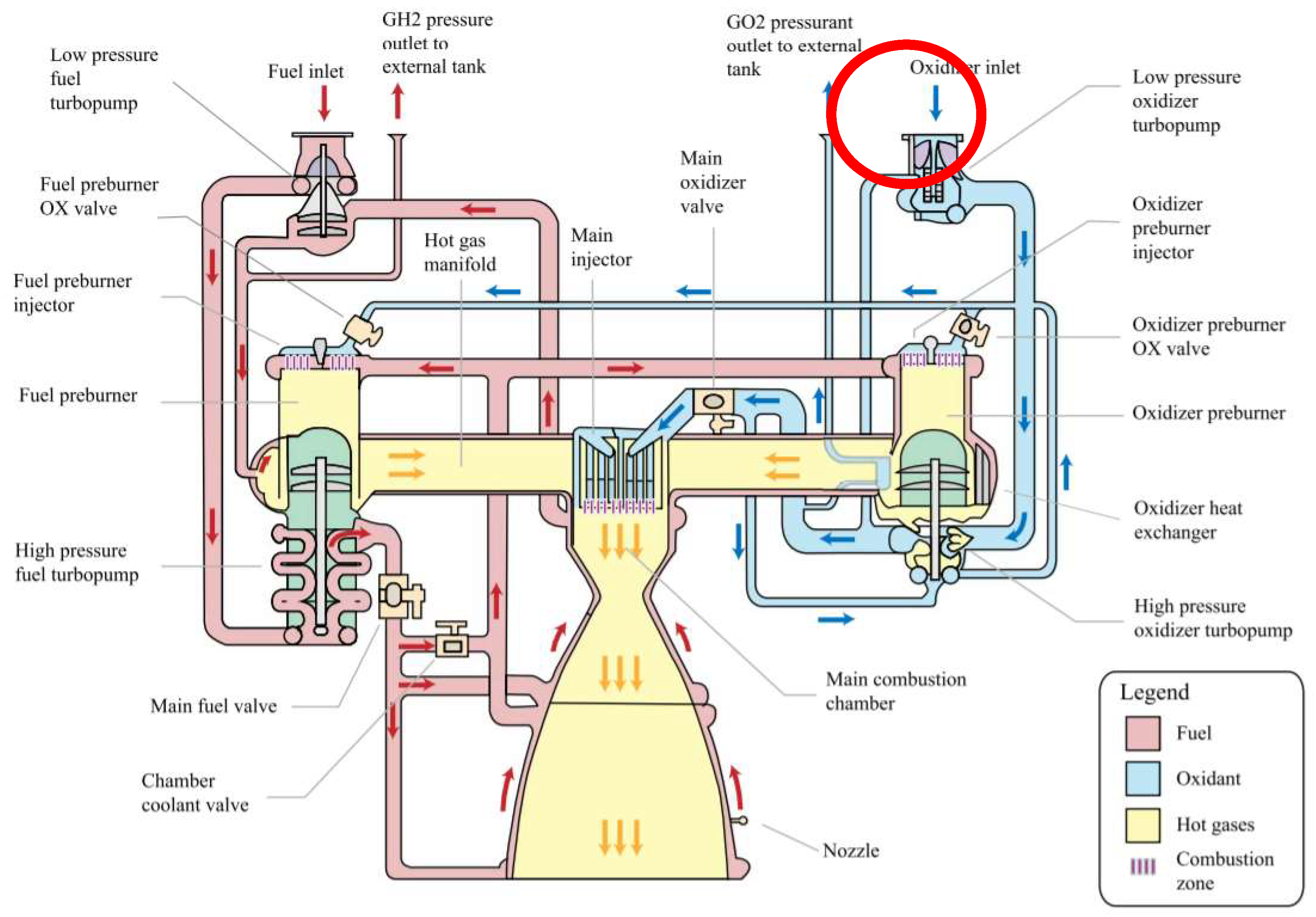

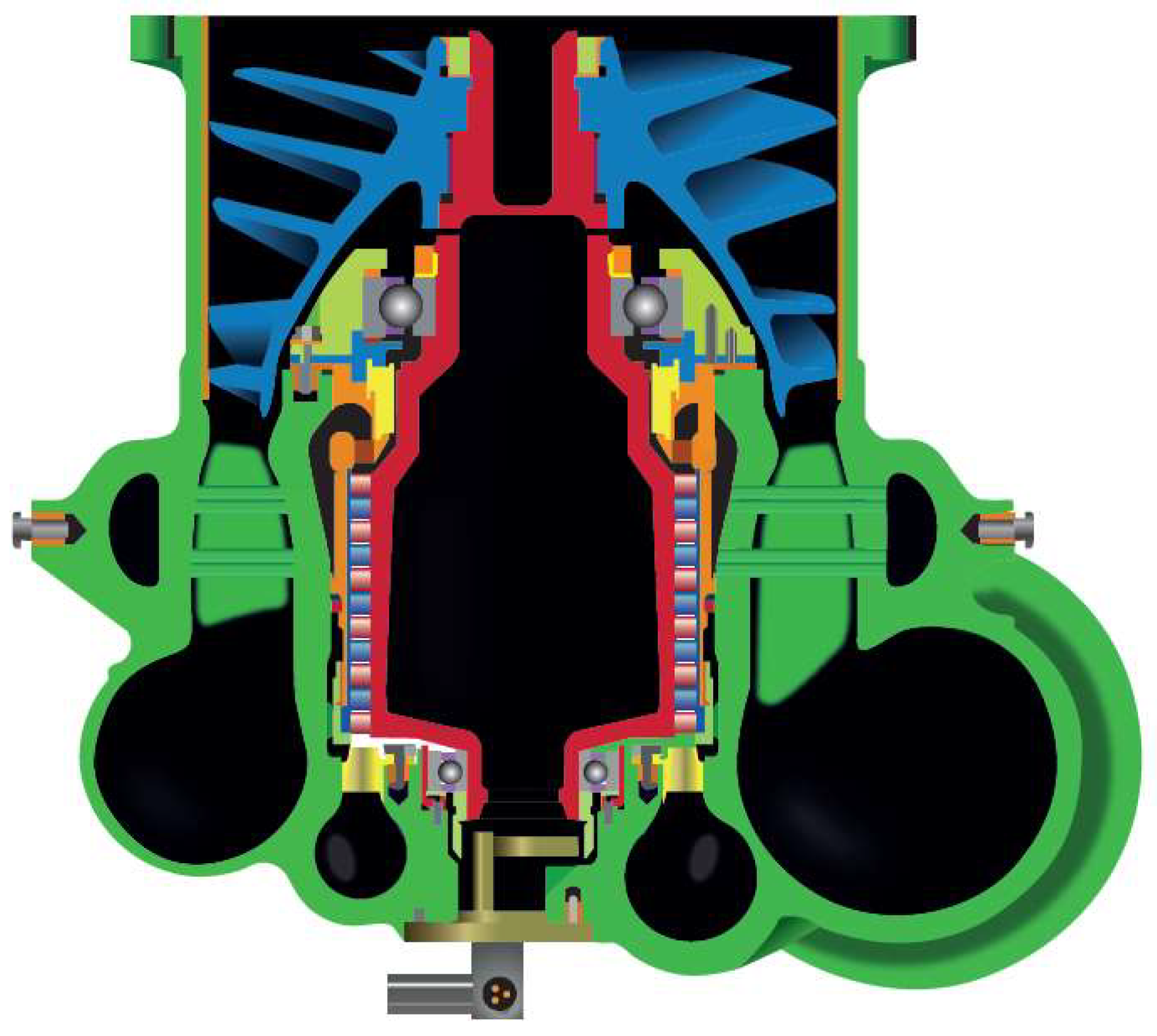

3. SSME LOX Booster Turbopump

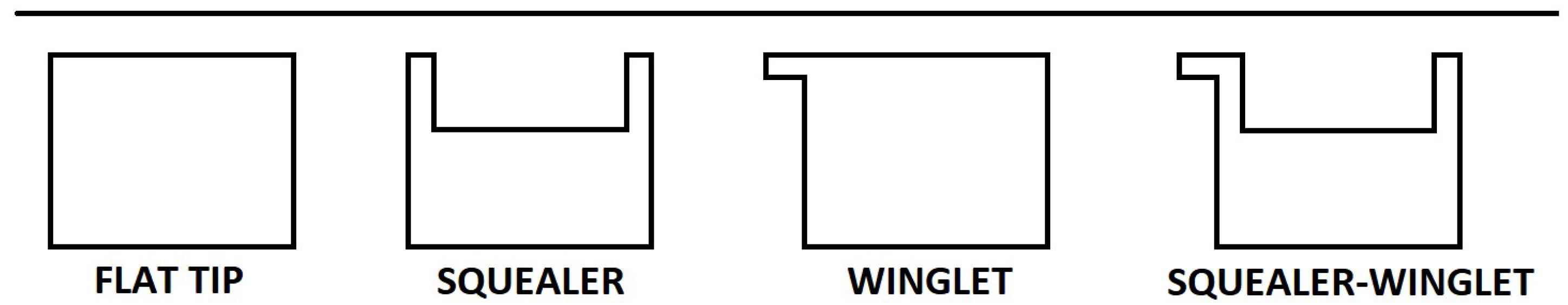

4. Tip Desensitization Methods

4.1. General Considerations

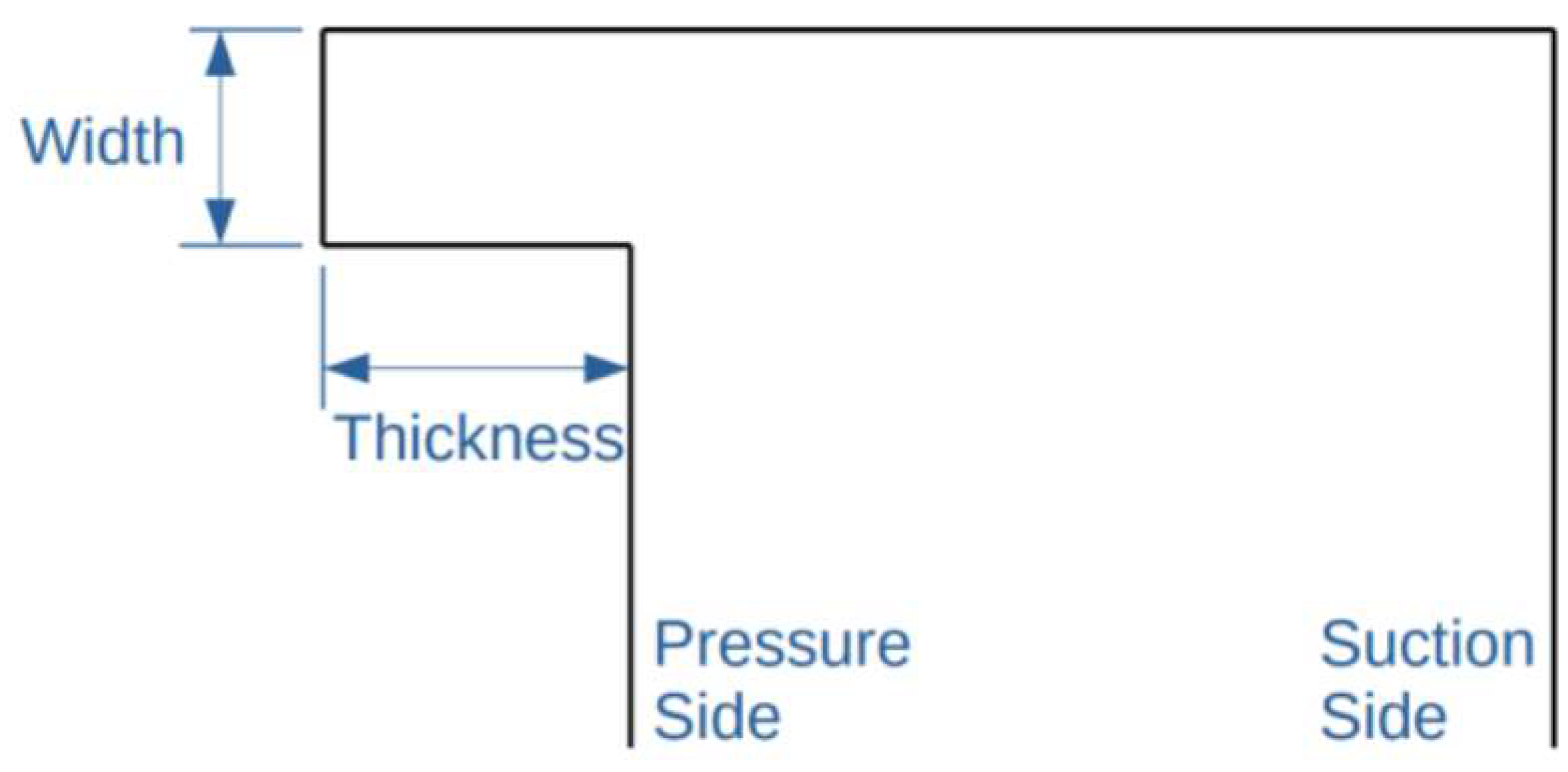

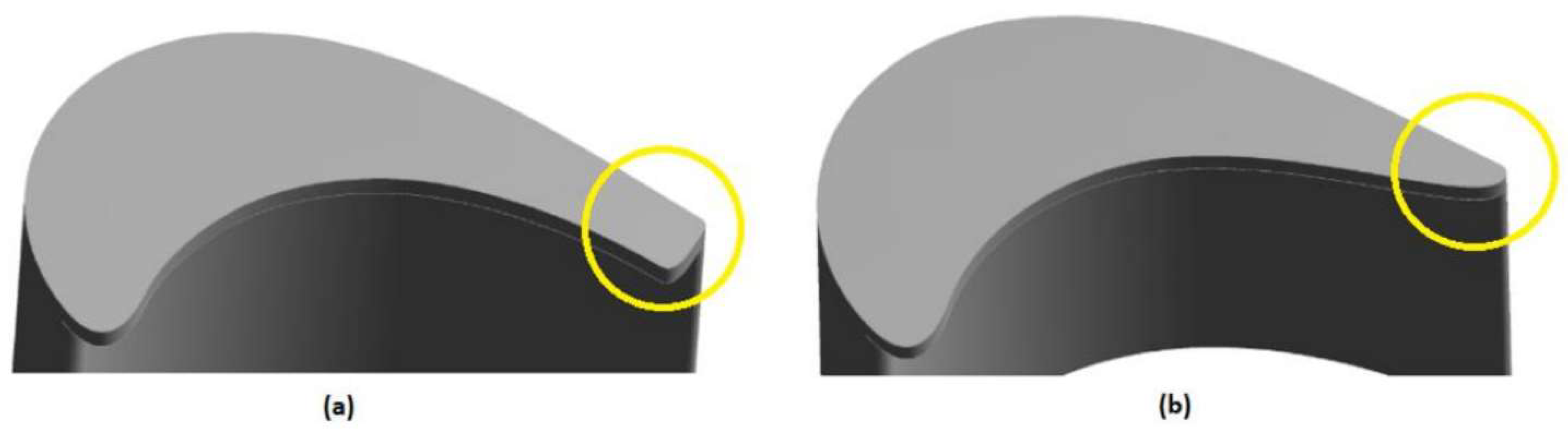

4.2. Winglet

5. Computational Mesh, Boundary Conditions, and Numerical Issues

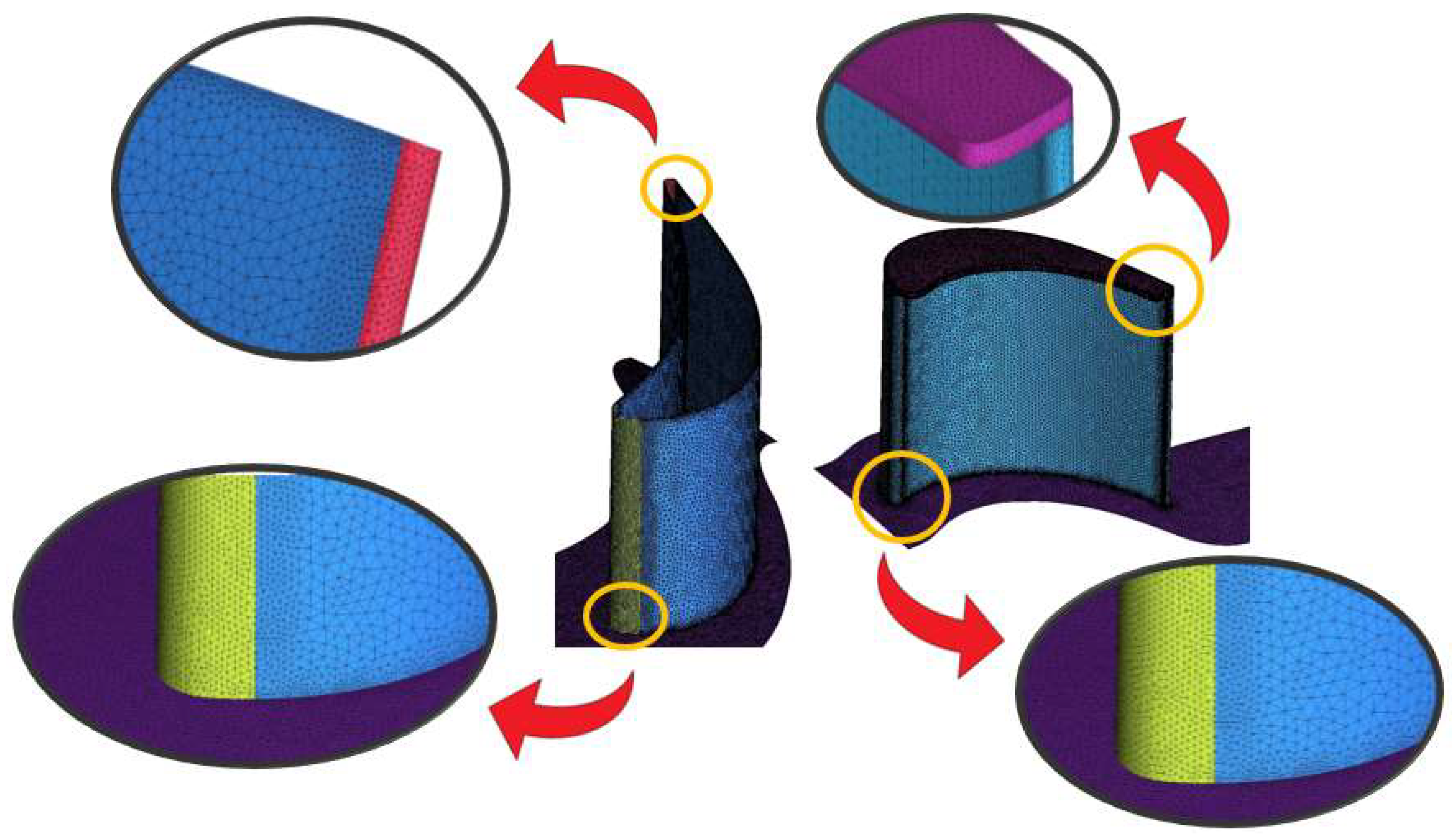

5.1. Computational Mesh Characteristics

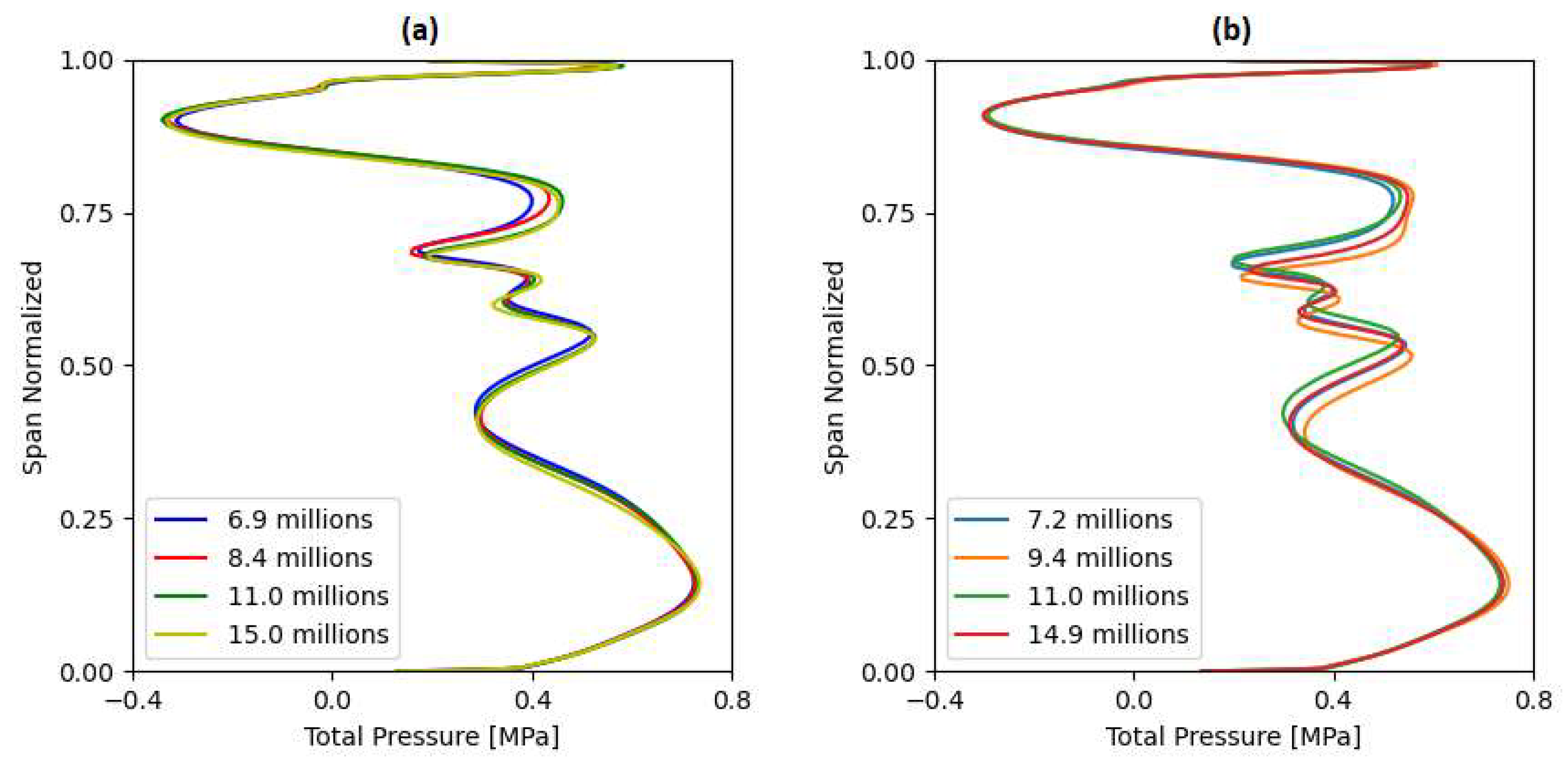

5.2. Mesh Independence Study

5.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

- Stage inlet: inflow velocity vector angles (axial direction), total temperature (294K), mass flow and turbulent intensity (5%).

- Stage Outlet: average static pressure at blade hub location and it is variation until the casing, using the radial equilibrium equation.

- Stator-Rotor interface: mixing-plane.

- Wall surfaces: non-slip condition.

- Blade-to-blade surfaces: periodicity.

5.4. Numerical Scheme

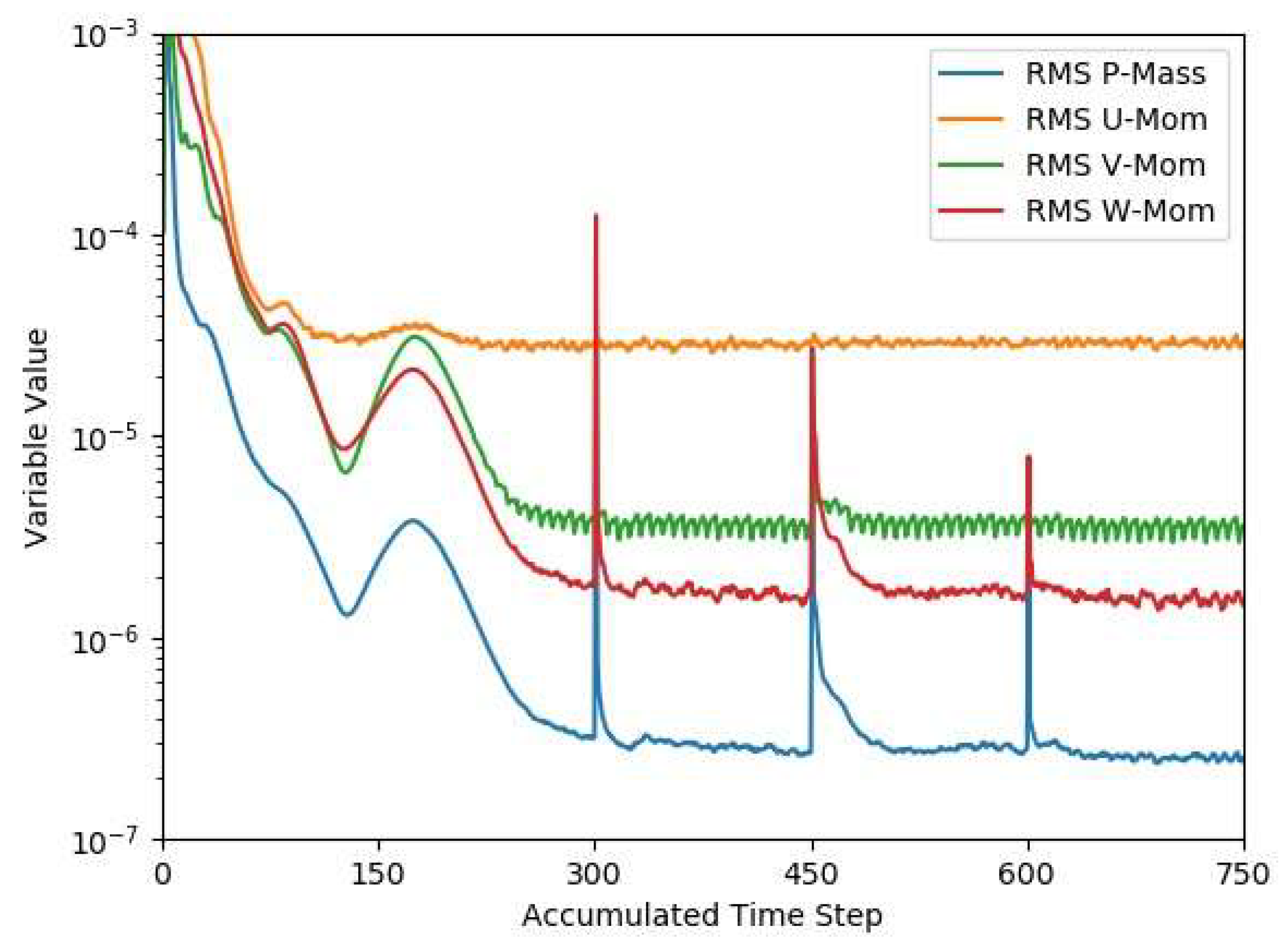

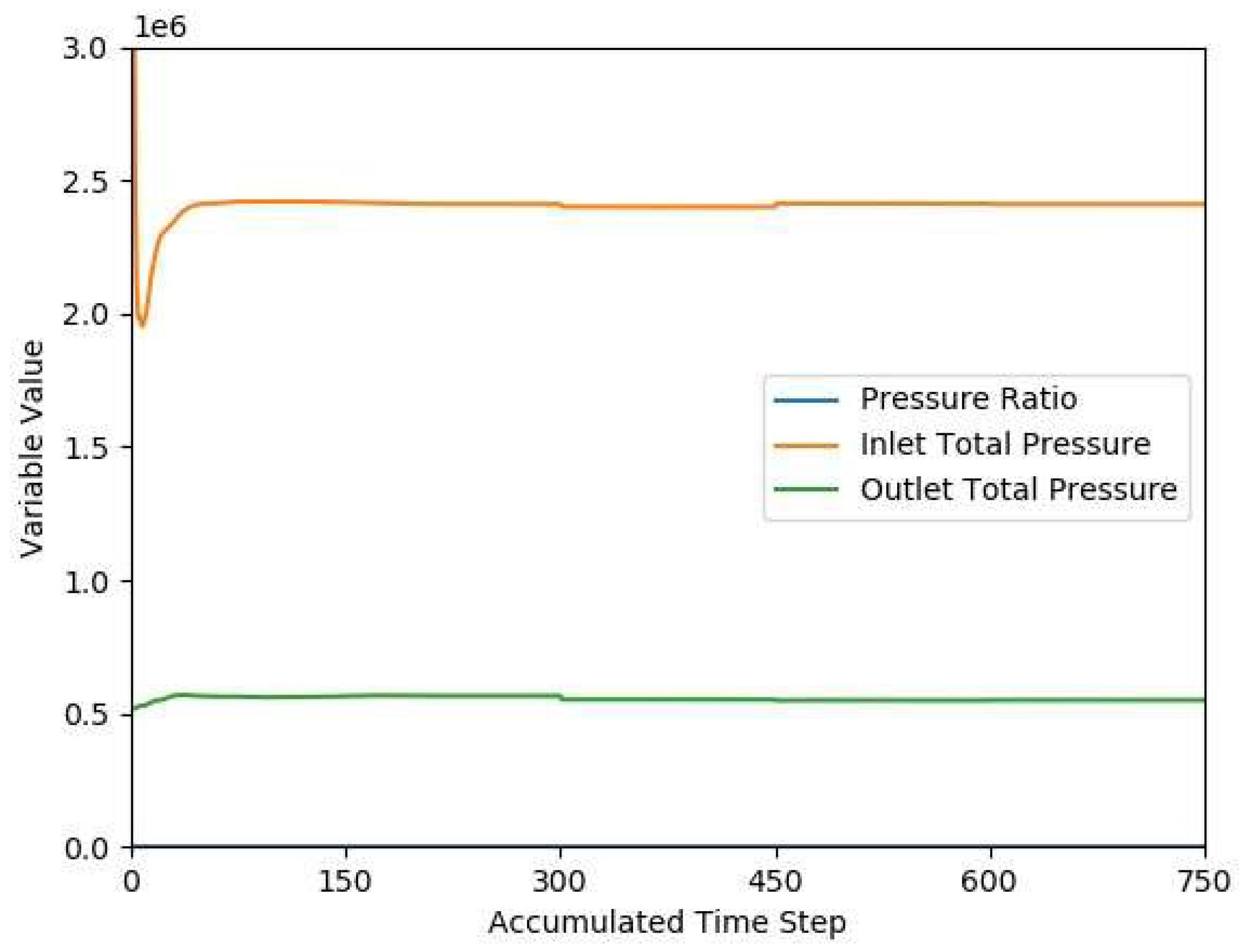

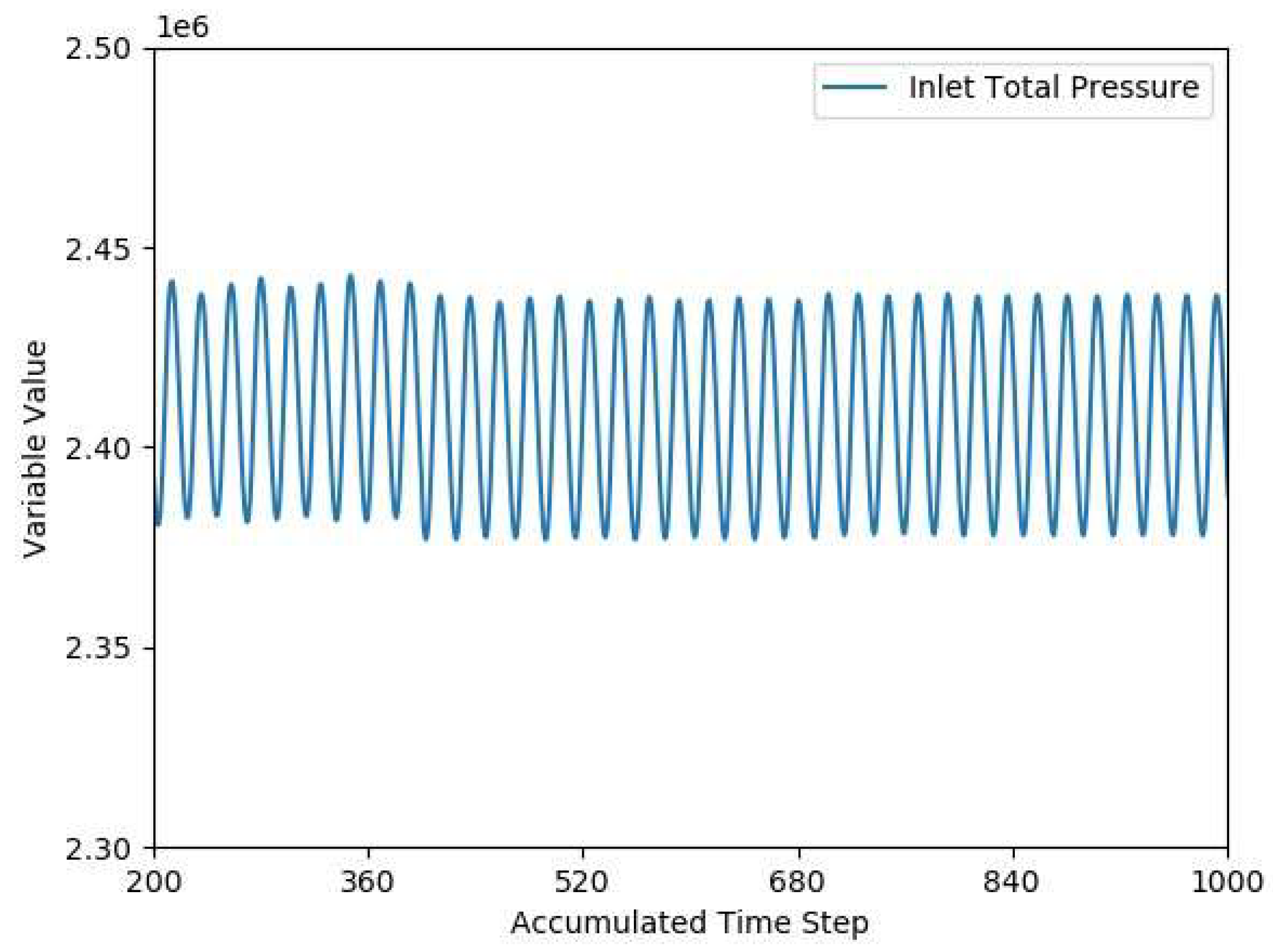

5.5. Residual Behavior

6. Results

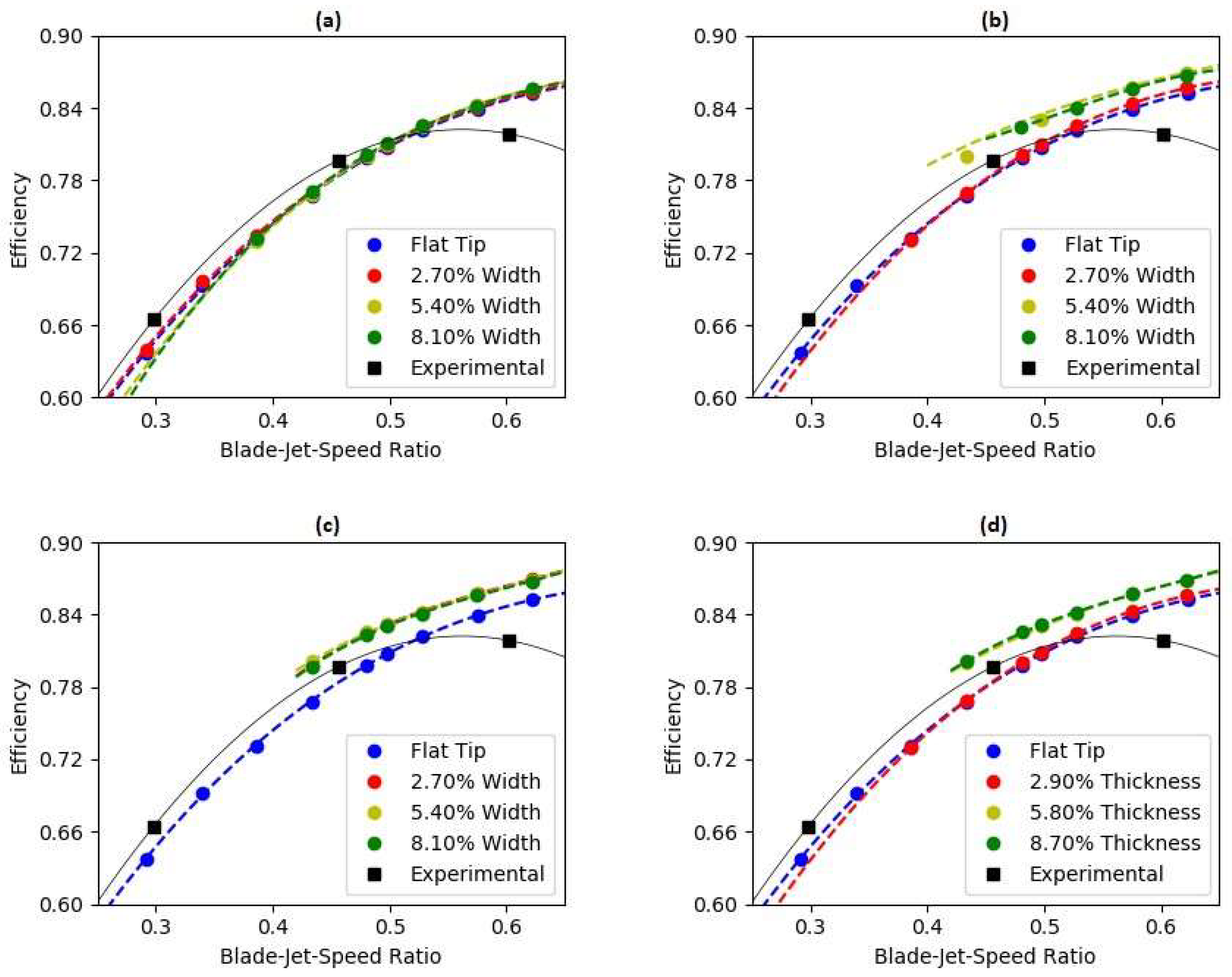

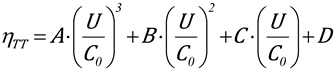

6.1. Effect of Winglet Geometries on Stage Efficiency

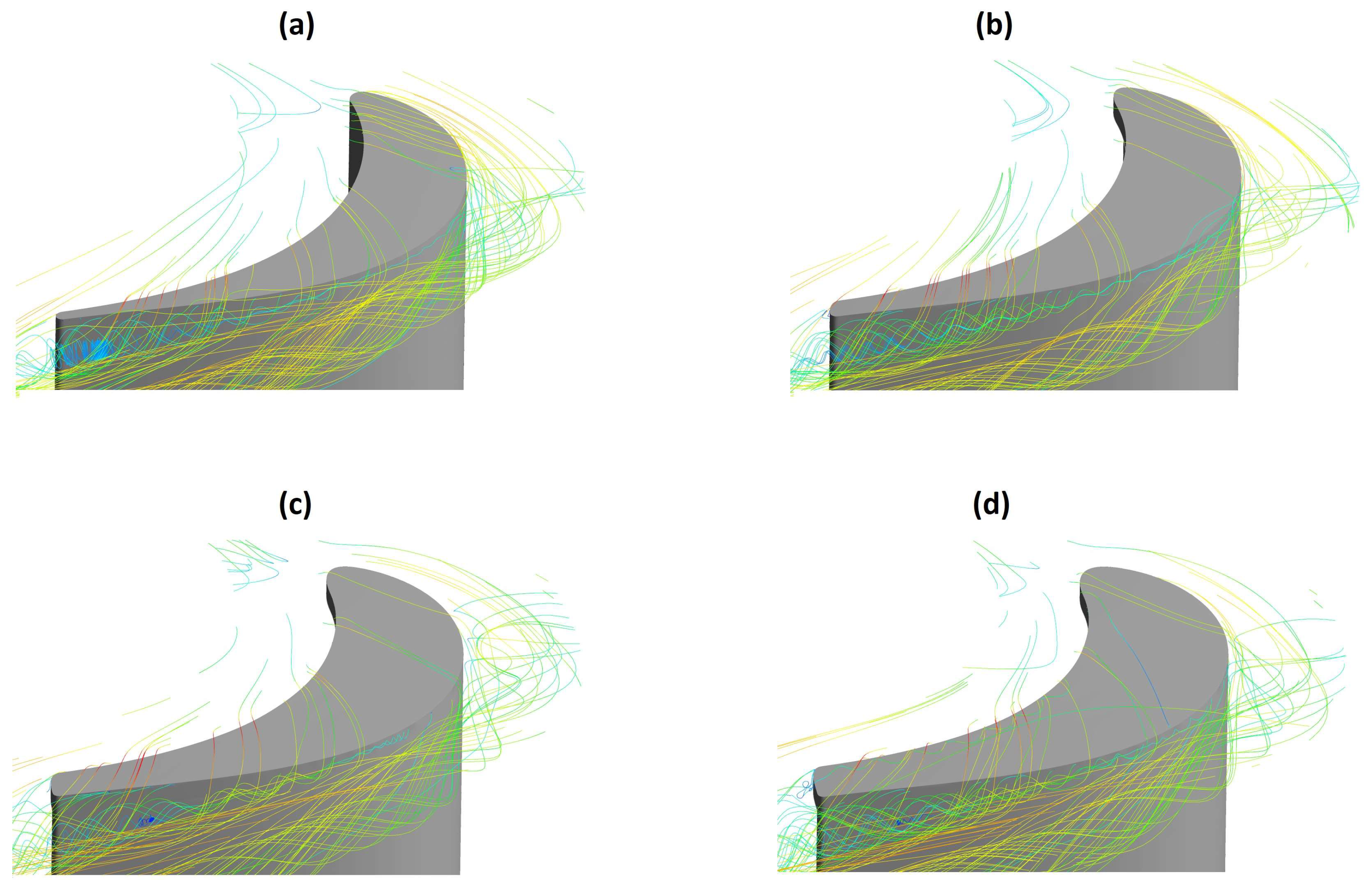

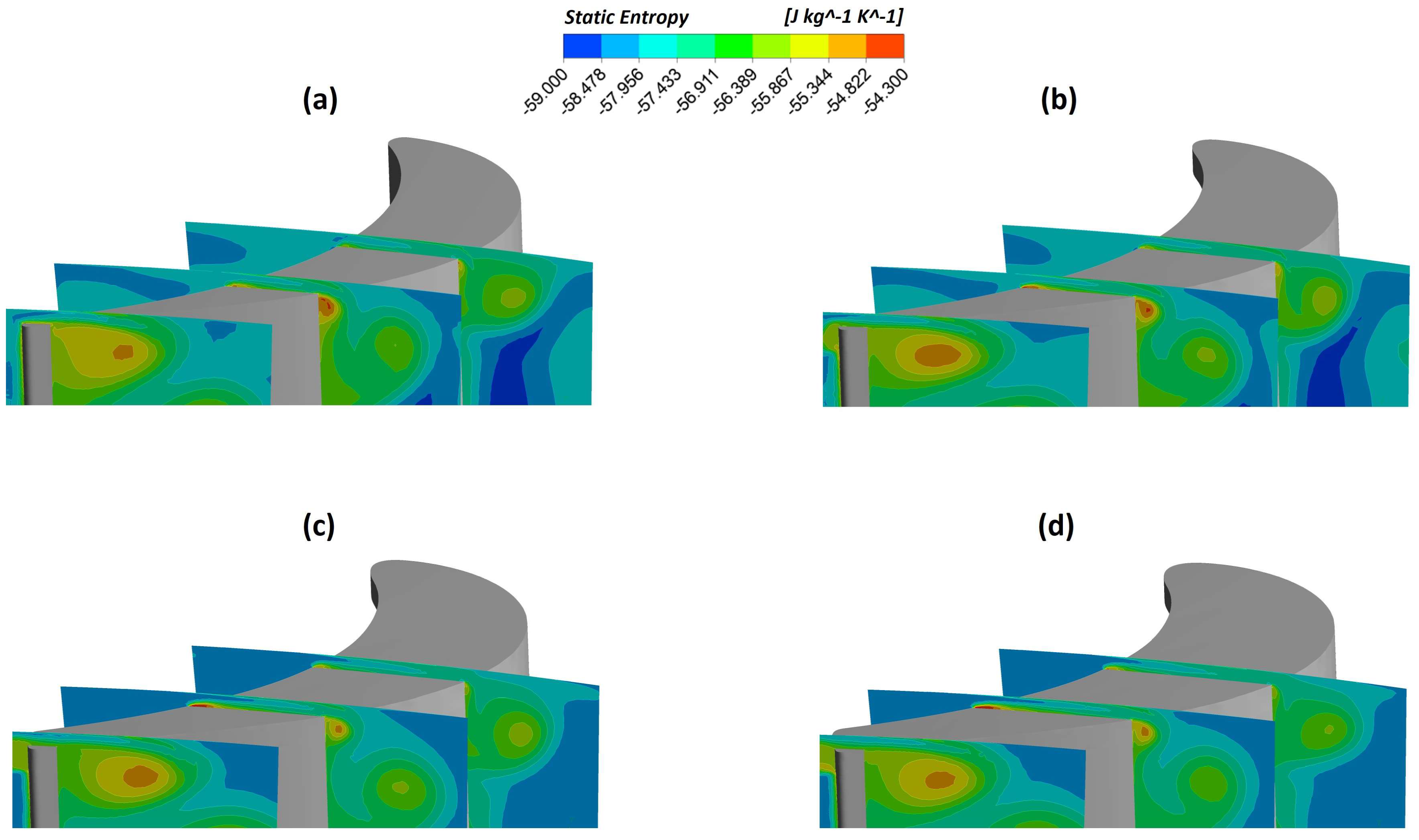

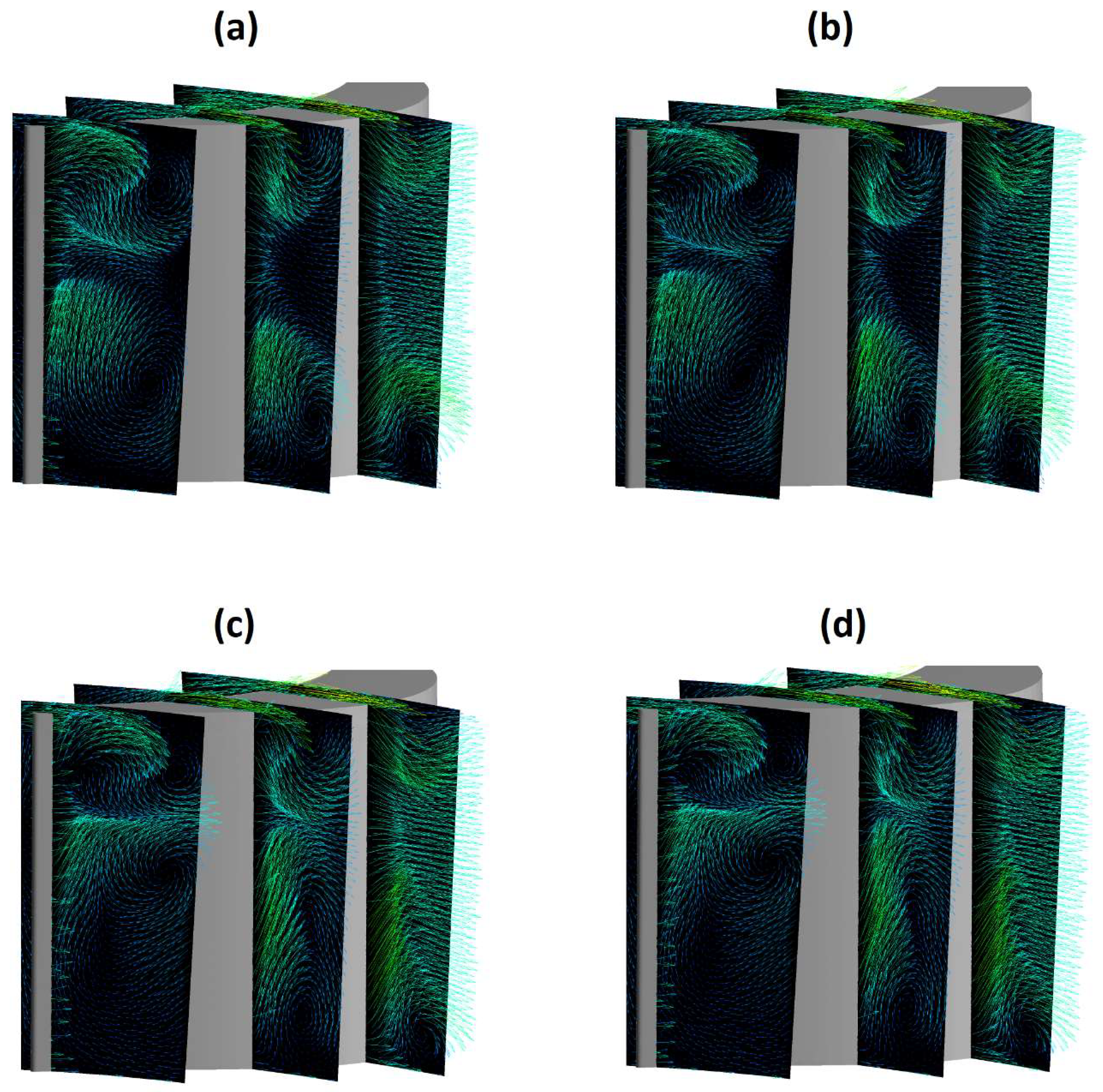

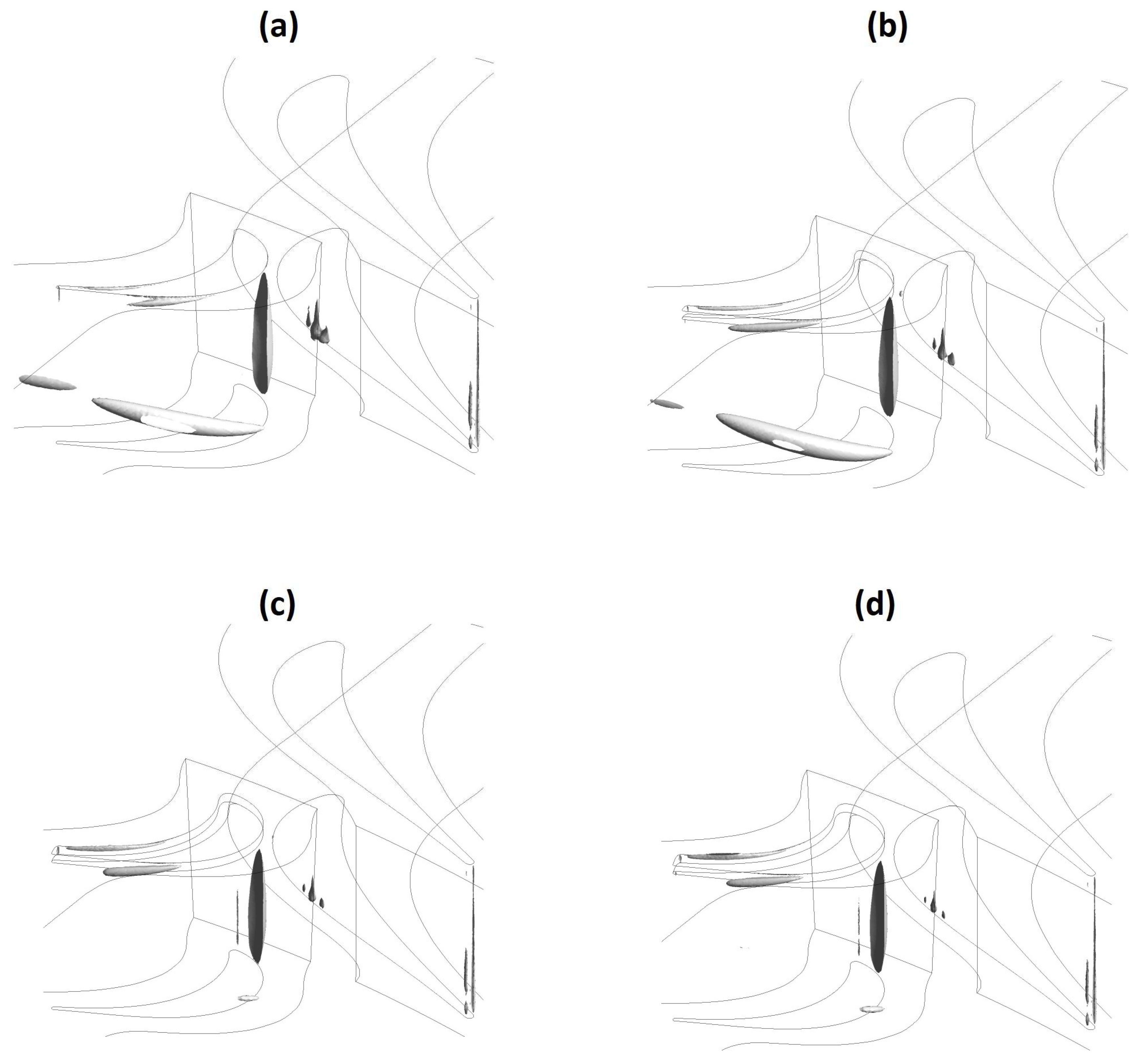

6.2. Effect of Squealer Geometries in the Axial Turbine Flowfield Characteristics

7. Conclusions

- The winglet parametric analysis was performed considering 2.90%, 5.80% and 8.70% thickness, and 2.70%, 8.40%, and 8.10% width. These percentages are all in relation to the blade height. The nine proposed geometries results shown that the winglet thickness increase supply a positive impact on the turbine total efficiency – the greater the thickness, the greater the stage efficiency. There must be a maximum value of this parameter from which the efficiency remains constant.

- The winglet width dimension almost does not impact the stage efficiency.

- In general, the results found in this work show that the winglet geometries analyzed are able to provide a higher increase in the stage performance than the squealer techniques evaluated in a previous research [17].

- Winglet geometry of 8.70% thickness and 5.40% width, provide the highest stage efficiency average increase (2.23%), over the entire turbine operational range, in comparison with the rotor flat tip configuration. For reference, the highest average increase of this parameter for the squealer geometries, available in [17], was of 1.43%.

- Regarding the vortexes in the tip region, the same behavior shown in previous works for the flat tip and the squealer geometries were maintained for the winglet modifications: they have a different rotation direction, reducing the losses on the region. However, for the winglet geometries that provide the better performance results, it is noted that the scrapping vortex is displaced in relation to the flat tip case, due to the leakage and passage vortexes effects.

- The cavitation results obtained with the application of winglet geometries show that would be possible to reduce the occurrence of this phenomenon at the blade suction side for some configurations. However, for these same configurations, there is an increase of the cavitation on the tip region. The effects of these combined changes on the turbine life cycle must be carefully analyzed thought structural simulations and tests.

- All proposed and evaluated geometries in this work are pressure side winglet geometries; it would be interesting to develop analyzes also for suction side and both sides variations of this desensitization technique.

- In order to validate the results obtained by the numerical simulations, the development experimental tests are necessary.

Acknowledgments

Nomenclature

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| ITA | Aeronautics Institute of Technology |

| LH2 | Liquid Hydrogen |

| LPOTP | Low Pressure Oxidizer Turbopump |

| LOX | Liquid Oxygen |

| LPREs | Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equations |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport |

| SSME | Space Shuttle Main Engine |

| TP | Turbopump |

| N | Rotational Frequency |

| ṁ | Mass Flow |

| p | Pressure |

| i | Inlet Condition |

| o | Outlet Condition |

| T | Total Condition |

| W | Turbine Shaft Power |

| τ | Turbine Torque |

| η | Turbine Efficiency |

| ρ | Density |

| UCasing | Peripheral Velocity |

| U/C0 | Blade-Jet-Speed Ratio |

| R | Turbine Rotor Blade Tip Radius |

References

- De Oliveira Silva, G.P.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C.; Whitacker, L.H.L.; Da Silva Tonon, D. Interactive Learning Platform for the Preliminary Design of Axial Turbines and Its Use for Graduate Courses. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2022; Vol. 5.

- Oliveira, I.; Silva, G.P.; Tonon, D.; Bringhenti, C.; Tomita, J.T. Interactive Learning Platform for Turbine Design Using Reduced Order Methods. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; Virtual, Online, 2020; Vol. 6.

- da Silva, L.M.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C. Numerical Investigation of a HPT with Different Rotor Tip Configurations in Terms of Pressure Ratio and Efficiency. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 63, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Silva, J.T. Tomita, J.R. Barbosa. A Study of the Influence of the Tip-Clearance on the Tip-Leakage Flow Using CFD Techniques. In: Brazilian Congress of Mechanical Engineering – COBEM, 2011.

- Schabowski, Z.; Hodson, H.; Giacche, D.; Power, B.; Stokes, M.R. Aeromechanical Optimization of a Winglet-Squealer Tip for an Axial Turbine. J. Turbomach. 2014, 136, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xuan, Y. A Novel Approach for Suppressing Leakage Flow through Turbine Blade Tip Gaps. Propuls. Power Res. 2022, 11, 431–443. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, L. Experimental Testing for the Influences of Rotation and Tip Clearance on the Labyrinth Seal in a Compressor Stator Well. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 71, 556–567. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y. A Flow Model for Tip Leakage Flow in Turbomachinery Using a Square Duct with a Longitudinal Slit. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 95, 105460. [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.C.; Dodge, P.R.; Hepworth, H.K. Rotor-Tip Leakage: Part I Basic Methodology. J. Eng. Power 1982, 104, 154–161.

- Krishnababu, S.K.; Newton, P.J.; Dawes, W.N.; Lock, G.D.; Hodson, H.P.; Hannis, J.; Whitney, C. Aerothermal Investigations of Tip Leakage Flow in Axial Flow Turbines-Part i: Effect of Tip Geometry and Tip Clearance Gap. J. Turbomach. 2009, 131, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bringhenti, C.; Barbosa, J.R. Effects of Turbine Tip Clearance on Gas Turbine Performance. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: Berlin, 2008.

- Moustapha, H.; Zelesky, M.F.; Baines, N.C.; Japikse, D. Axial and Radial Turbines; Concepts NREC: Vermont, 2003.

- Kim, J.; Song, S.J. Visualization of Rotating Cavitation Oscillation Mechanism in a Turbopump Inducer. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 2019, 141, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Sung, H.J.; Choi, C.H.; Kim, J.S. Cavitation Instabilities of an Inducer in a Cryogenic Pump. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 132, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Lindquist Whitacker, L.H.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C. An Evaluation of the Tip Clearance Effects on Turbine Efficiency for Space Propulsion Applications Considering Liquid Rocket Engine Using Turbopumps. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 70, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Whitacker, L.H.L.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C. Turbopump Booster Turbine Performance: Comparison Between Monophase and Multiphase Flows Using CFD.; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: Oslo, 2018; pp. 1–9.

- Tonon, D. da S.; Tomita, J.T.; Garcia, E.C.; Bringhenti, C.; Almeida, L.E.N. A Parametric Study of Squealer Tip Geometries Applied in a Hydraulic Axial Turbine Used in a Rocket Engine Turbopump. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 107426. [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K.; Acharya, S.; Bunker, R.; Prakash, C. Blade Tip Leakage Flow and Heat Transfer with Pressure-Side Winglet. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2006, 2006, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zamiri, A.; Choi, M.; Chung, J.T. Effect of Blade Squealer Tips on Aerodynamic Performance and Stall Margin in a Transonic Centrifugal Compressor with Vaned Diffuser. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107504. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Jiang, D.; Li, Y.; Du, Z.; Wang, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigations for Turbine Aerodynamic Performance with Different Pressure Side Squealers and Incidence Angles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 108234. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zou, Z.; Yao, L.; Fu, C. Refined Flow Organization in Squealer Tip Gap and Its Impact on Turbine Aerodynamic Performance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 108331. [CrossRef]

- Tonon, D. da S.; Tomita, J.T.; Garcia, E.C.; Bringhenti, C.; Díaz, R.B.; Whitacker, L.H.L. Comparative Study Between Structured and Unstructured Meshes Applied in Turbopump’s Hydraulic Turbine.; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: Online, 2020; pp. 1–13.

- Tonon, D. da S.; Tomita, J.T.; Garcia, E.C.; Bringhenti, C.; Almeida, L.E.N. Effects of a Squealer-Winglet Geometry on the Aerodynamic Performance of a Hydraulic Axial Turbine Used in Turbopumps.; ISABE, Ed.; 25th International Symposium on Air Breathing Engines: Ottawa, Canada, 2022.

- Barbosa, D.F.C.; Tonon, D. da S.; Luiz Henrique, L.W.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C. Evaluation of Different Turbulence Models Applied in Turbopump’s Hydraulic Turbine. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; Virtual, Online, 2021; Vol. 2C-2021.

- Boynton, J.L.; Rohlik, H.E. Effect of Tip Clearance on Performance of Small Axial Hydraulic Turbine; Cleveland, Ohio, 1976.

- Sieverding, C.H. Recent Progress in the Understanding of Basic Aspects of Secondary Flows in Turbine Blade Passages. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1985, 107, 248–257. [CrossRef]

- Langston, L.S. Secondary Flows in Axial Turbines - A Review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 934, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Ainley, D.G.; Mathieson, C.R. A Method of Performance Estimation for Axial-Flow Turbines. Aeronaut. Res. Counc. reports Memo. N. 2974 1951, 2974.

- Dunham, J.; Came, P.M. Improvements to the Ainley-Mathieson Method of Turbine Performance Prediction. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1970, 92, 252–256. [CrossRef]

- Kacker, S.C.; Okapuu, U. A Mean Line Prediction Method for Axial Flow Turbine Efficiency. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1982, 104, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Moustapha, H.; Kacker, S.C.; Traemblay, B. An Improved Incidence Losses Prediction Method for Turbine Airfoils. J. Turbomach. 1990, 112, 267–276.

- da Silva, L.M. Cálculo Do Escoamento Em Uma Turbina Axial de Alta Pressão Com Diferentes Configurações Na Geometria Do Topo Do Rotor Utilizando Técnicas de CFD, Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica, 2012.

- Lee, S.W.; Jeong, J.S.; Hong, I.H. Chord-Wise Repeated Thermal Load Change on Flat Tip of a Turbine Blade. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 138, 1154–1165. [CrossRef]

- Bunker, R.S.; Bailey, J.C.; Ameri, A.A. Heat Transfer and Flow on the First Stage Blade Tip of a Power Generation Gas Turbine Part 1: Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; ASME/NASA, Ed.; 44th Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress: Indianapolis, IN, 1999; Vol. 3.

- Han, J.C.; Dutta, S.; Ekkad, S. Gas Turbine Heat Transfer and Cooling Technology; 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2013; ISBN 0791835332.

- Dey, D.; Camci, C. Aerodynamic Tip Desensitization of an Axial Turbine Rotor Using Tip Platform Extensions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: New Orleans, LA, 2001.

- Langston, L.S.; Nice, M.L.; Hooper, R.M. Three-Dimensional Flow Within a Turbine Cascade Passage. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1976, 21–28.

- Yamamoto, A. Interaction Mechanisms between Tip Leakage Flow and the Passage Vortex in a Linear Turbine Rotor Cascade. J. Turbomach. 1988, 110, 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Si, H.; Wang, J.; Li, P. Effects of Leakage Vortex on Aerodynamic Performance and Loss Mechanism of Steam Turbine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2019, 233, 866–876. [CrossRef]

- Passmann, M.; Aus Der Wiesche, S.; Joos, F. An Experimental and Numerical Study of Tip-Leakage Flows in an Idealized Turbine Tip Gap at High Mach Numbers. Proc. ASME Turbo Expo 2018, 2B-2018, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Arakeri, V.H. Contributions to Some Cavitation Problems in Turbomachinery. Sadhana - Acad. Proc. Eng. Sci. 1999, 24, 453–483. [CrossRef]

- Whitacker, L.H.L. Determinação Da Influência Da Folga de Topo Na Eficiência de Uma Turbina Axial Multiestágio Utilizada Em Booster de Motor Foguete Para Operação Com LOX, Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica, 2017.

- A. J. Acosta, An Experimental Study of Cavitating Inducers " . 2 Nd Symposium on Naval Hydrodynamics, Hydrodynamic Noise, Cavity Flow, Pp.25-29, 1958.

- Whitacker, L.H.L.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C. Effect of Tip Clearance on Cavitating Flow of a Hydraulic Axial Turbine Applied in Turbopump. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 213, 106855. [CrossRef]

- Lindau, R.F.; Kunz, J.W.; Venkateswaran, S.; Boger, D. a Application of Preconditioned , Multiple-Species , Navier-Stokes Models To Cavitating Flows. Cav2001 2001, 1–14.

- Pinho, J.; Peveroni, L.; Vetrano, M.R.; Buchlin, J.M.; Steelant, J.; Strengnart, M. Experimental and Numerical Study of a Cryogenic Valve Using Liquid Nitrogen and Water. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 105331. [CrossRef]

- Piscaglia, F.; Giussani, F.; Hèlie, J.; Lamarque, N.; Aithal, S.M. Vortex Flow and Cavitation in Liquid Injection: A Comparison between High-Fidelity CFD Simulations and Experimental Visualizations on Transparent Nozzle Replicas. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2021, 138. [CrossRef]

- Balz, R.; Nagy, I.G.; Weisser, G.; Sedarsky, D. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Cavitation in Marine Diesel Injectors. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 169, 120933. [CrossRef]

- Pouffary, B.; Patella, R.F.; Reboud, J.L.; Lambert, P.A. Numerical Simulation of 3D Cavitating Flows: Analysis of Cavitation Head Drop in Turbomachinery. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 2008, 130, 0–10. [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, A.; Pavesi, G.; Ardizzon, G.; Santolin, A. Numerical Analyses of Cavitating Flow in a Pelton Turbine. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 2014, 136, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Numerical Simulation of Cavitating Turbulent Flow in a High Head Francis Turbine at Part Load Operation with OpenFOAM. Procedia Eng. 2012, 31, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Guo, P.; Luo, X. Numerical Investigation of Inter-Blade Cavitation Vortex for a Francis Turbine at Part Load Conditions. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2021, 15, 1163–1177. [CrossRef]

- Ghenaiet, A.; Bakour, M. Hydrodynamic Characterization of Small-Size Kaplan Turbine. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2021, 147, 06020019. [CrossRef]

- Sivolella, D. The Space Shuttle Program; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 9783319549446.

- United States. Main Propulsion System. Shuttle Press Kit.Com, Boeing, NASA & United Space Alliance, 1998.

- United States. Space Transportation System Training Data, Space Shuttle Main Engine Orientation. Boeing, June 1998.

- You, Y.; Ding, L. Numerical Investigation of Unsteady Film Cooling on Turbine Blade Squealer Tip with Pressure Side Coolant. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 143, 106720. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Investigations on the Aerothermal Performance of the Turbine Blade Winglet Squealer Tip within an Uncertainty Framework. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107506. [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Mao, J.; Chen, P.; Han, F.; Wang, L. Effect of Multiple Cavities and Tip Injection on the Aerothermal Characteristics of the Squealer Tip in Turbine Stage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 220, 119631. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Chung, J.T. Numerical Analysis of the Aerodynamic Performance & Heat Transfer of a Transonic Turbine with a Partial Squealer Tip. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 152, 878–889. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.W.; Newman, D.A.; Haselbach, F.; Willer, L. An Investigation Into a Novel Turbina Rotor Winglet Part 1: Design and Model Rig Test Results.; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: Barcelona, 2006.

- Lee, S.W.; Choi, M.Y. Tip Gap Height Effects on the Aerodynamic Performance of a Cavity Squealer Tip in a Turbine Cascade in Comparison with Plane Tip Results: Part 2-Aerodynamic Losses. Exp. Fluids 2010, 49, 713–723. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Tonon, D.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C.; Barbosa, D.F.C.; Whitacker, L.H.L.; Almeida, L.E.N. Effects of Two Winglet Tip Geometries on the Flow and Aerodynamic Performance of a Hydraulic Axial Turbine. 33rd Congr. Int. Counc. Aeronaut. Sci. ICAS 2022 2022, 4, 2402–2418.

- Camci, C.; Dey, D.; Kavurmacioglu, L. Tip Leakage Flows Near Partial Squealer Rims in an Axial Flow Turbine Stage.; ASME, Ed.; ASME Turbo Expo: Atlanta, GE, 2003.

- Zhou, C.; Hodson, H.; Tibbott, I.; Stokes, M. Effects of Winglet Geometry on the Aerodynamic Performance of Tip Leakage Flow in a Turbine Cascade. J. Turbomach. 2013, 135, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.C.; Lee, S.W. Tip Gap Flow and Aerodynamic Loss Generation in a Turbine Cascade Equipped with Suction-Side Winglets. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 703–712. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.S.; Bong, S.W.; Lee, S.W. An Efficient Winglet Coverage for Aeroengine Turbine Blade Flat Tip and Its Loss Map. Energy 2022, 260, 125153. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, W. Effects of Combined Sweeping Jet Actuator and Winglet Tip on Aerodynamic Performance in a Turbine Cascade. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 131, 107956. [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, D.O.; Zhang, Q.; He, L.; Oldfield, M.L.G.; Ligrani, P.M.; Cheong, B.C.Y.; Tibbott, I. Aerothermal Performance of a Winglet at Engine Representative Mach and Reynolds Numbers. J. Turbomach. 2011, 133, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.H.; Lee, S.W. Winglet Geometry Effects on Tip Leakage Loss over the Plane Tip in a Turbine Cascade. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 1633–1642. [CrossRef]

- Coull, J.D.; Atkins, N.R.; Hodson, H.P. Winglets for Improved Aerothermal Performance of High Pressure Turbines. J. Turbomach. 2014, 136, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Rhie, C.M.; Allison, D.D.; Asme, A.; Thermoph, J.; Louis, S. A Numerical Study of the Turbulent Flow Past an Isolated Airfoil With Trailing Edge Separation Fluids , Plasma and Heat Trans Er Conference A NUMERICAL STUDY OF THE TURBULENT FLOW PAST AN ISOLATED. 1982.

- da Silva, L.M.; Tomita, J.T.; Bringhenti, C.; Whitacker, L.H.L.; Almeida, L.E.N.; Cavalca, D.F. A Small Jet Engine Preliminary Design and Its Performance Calculations.; ISABE, Ed.; 24th International Symposium on Air Breathing Engines: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

| Thickness (%) | Width (%) | Mesh 1 | Mesh 2 | Mesh 3 | Mesh 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.90 | 2.70 | 7.2 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 14.9 |

| 2.90 | 5.40 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 15.8 |

| 2.90 | 8.10 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 15.1 |

| 5.80 | 2.70 | 6.6 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 15.7 |

| 5.80 | 5.40 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 15.2 |

| 5.80 | 8.10 | 8.6 | 11.0 | 13.1 | 18.3 |

| 8.70 | 2.70 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 11.6 | 15.5 |

| 8.70 | 5.40 | 6.9 | 8.4 | 11.0 | 15 |

| 8.70 | 8.10 | 8.7 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 17.7 |

|

|||||

| Thickness [%] | Width [%] | A | B | C | D |

| 2.90 | 2.70 | 1.0339 | -2.8360 | 2.5599 | 0.1098 |

| 2.90 | 5.40 | 1.1505 | -3.1993 | 2.8677 | 0.0330 |

| 2.90 | 8.10 | 2.3079 | -4.9466 | 3.7219 | -0.1012 |

| 5.80 | 2.70 | 0.9700 | -2.9132 | 2.7195 | 0.05874 |

| 5.80 | 5.40 | 1.1260 | -2.5565 | 2.1145 | 0.2718 |

| 5.80 | 8.10 | -4.0937 | 6.2653 | -2.8493 | 1.2008 |

| 8.70 | 2.70 | 4.3434 | -7.9066 | 5.0558 | -0.2616 |

| 8.70 | 5.40 | 3.2998 | -6.0235 | 3.9295 | -0.0389 |

| 8.70 | 8.10 | 4.2550 | -7.7215 | 4.9318 | -0.2362 |

| Percentage differences relative to flat tip [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | U/C0 | 2.70% width | 5.40% width | 8.10% width |

| Average | - | 0.1624 | 0.1760 | 0.2403 |

| DP | 0.4706 | 0.1708 | 0.1483 | 0.2909 |

| Experimental | 0.2983 | 0.2898 | - | - |

| 0.4559 | 0.1803 | 0.0899 | 0.2610 | |

| 0.6017 | 0.1315 | 0.3600 | 0.2898 | |

| 0.3860 | 0.2307 | -0.3068 | -0.1352 | |

| 0.4193 | 0.2060 | -0.0921 | 0.1143 | |

| 0.4526 | 0.1825 | 0.0757 | 0.2522 | |

| 0.4859 | 0.1617 | 0.2006 | 0.3084 | |

| 0.5192 | 0.1450 | 0.2868 | 0.3125 | |

| 0.5525 | 0.1340 | 0.3384 | 0.2943 | |

| 0.5858 | 0.1303 | 0.3595 | 0.2836 | |

| Percentage differences relative to flat tip [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | U/C0 | 2.70% width | 5.40% width | 8.10% width |

| Average | - | 0.3504 | 2.0292 | 2.0485 |

| DP | 0.4706 | 0.2025 | 2.5643 | 2.8442 |

| Experimental | 0.2983 | - | - | - |

| 0.4559 | 0.1431 | 2.7607 | 3.2627 | |

| 0.6017 | 0.4431 | 1.6614 | 1.5760 | |

| 0.4500 | 0.1174 | 2.8446 | 3.4556 | |

| 0.4726 | 0.2100 | 2.5390 | 2.7937 | |

| 0.4953 | 0.2875 | 2.2759 | 2.3189 | |

| 0.5179 | 0.3491 | 2.0586 | 2.0000 | |

| 0.5405 | 0.3953 | 1.8871 | 1.7997 | |

| 0.5632 | 0.4262 | 1.7621 | 1.6824 | |

| 0.5858 | 0.4415 | 1.6857 | 1.6140 | |

| Percentage differences relative to flat tip [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | U/C0 | 2.70% width | 5.40% width | 8.10% width |

| Average | - | 2.2178 | 2.2336 | 2.0803 |

| DP | 0.4706 | 2.6896 | 2.7865 | 2.5686 |

| Experimental | 0.2983 | - | - | - |

| 0.4559 | 2.8038 | 2.9793 | 2.6967 | |

| 0.6017 | 1.6917 | 1.6386 | 1.5419 | |

| 0.4300 | 2.9451 | 3.3082 | 2.8694 | |

| 0.4560 | 2.8031 | 2.9780 | 2.6959 | |

| 0.4819 | 2.5902 | 2.6389 | 2.4604 | |

| 0.5079 | 2.3405 | 2.3129 | 2.1955 | |

| 0.5339 | 2.0901 | 2.0258 | 1.9368 | |

| 0.5598 | 1.8755 | 1.8031 | 1.7197 | |

| 0.5858 | 1.7304 | 1.6676 | 1.5771 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).