Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Srv2 Compressor with Volute

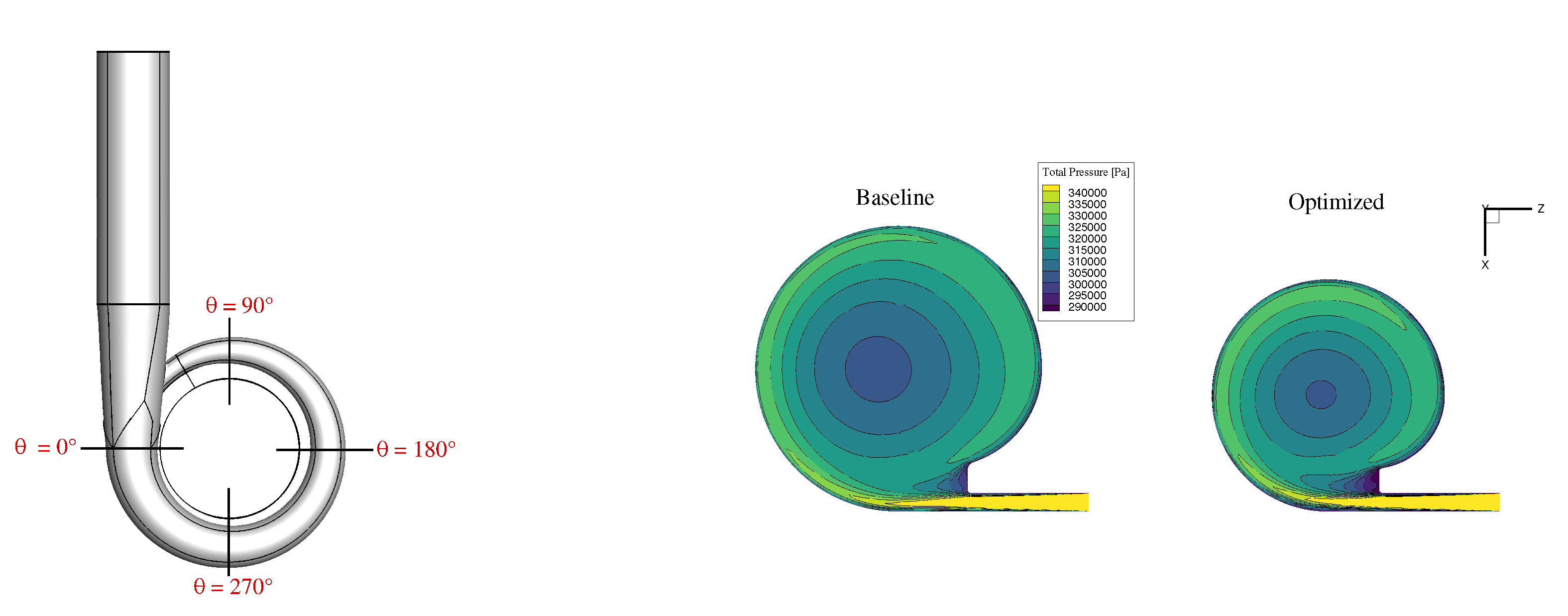

2.1. Geometry Definition

2.2. Numerical Framework

2.3. Preliminary Setup for the Optimization

| Inlet flow angle | [] | 50 | |

| Inlet total pressure | [Pa] | 343000 | |

| Inlet total temperature | [K] | 453 | |

| Outlet static pressure | [Pa] | 310000 |

VOLUTE OPTIMIZATION

2.4. Objective Definition

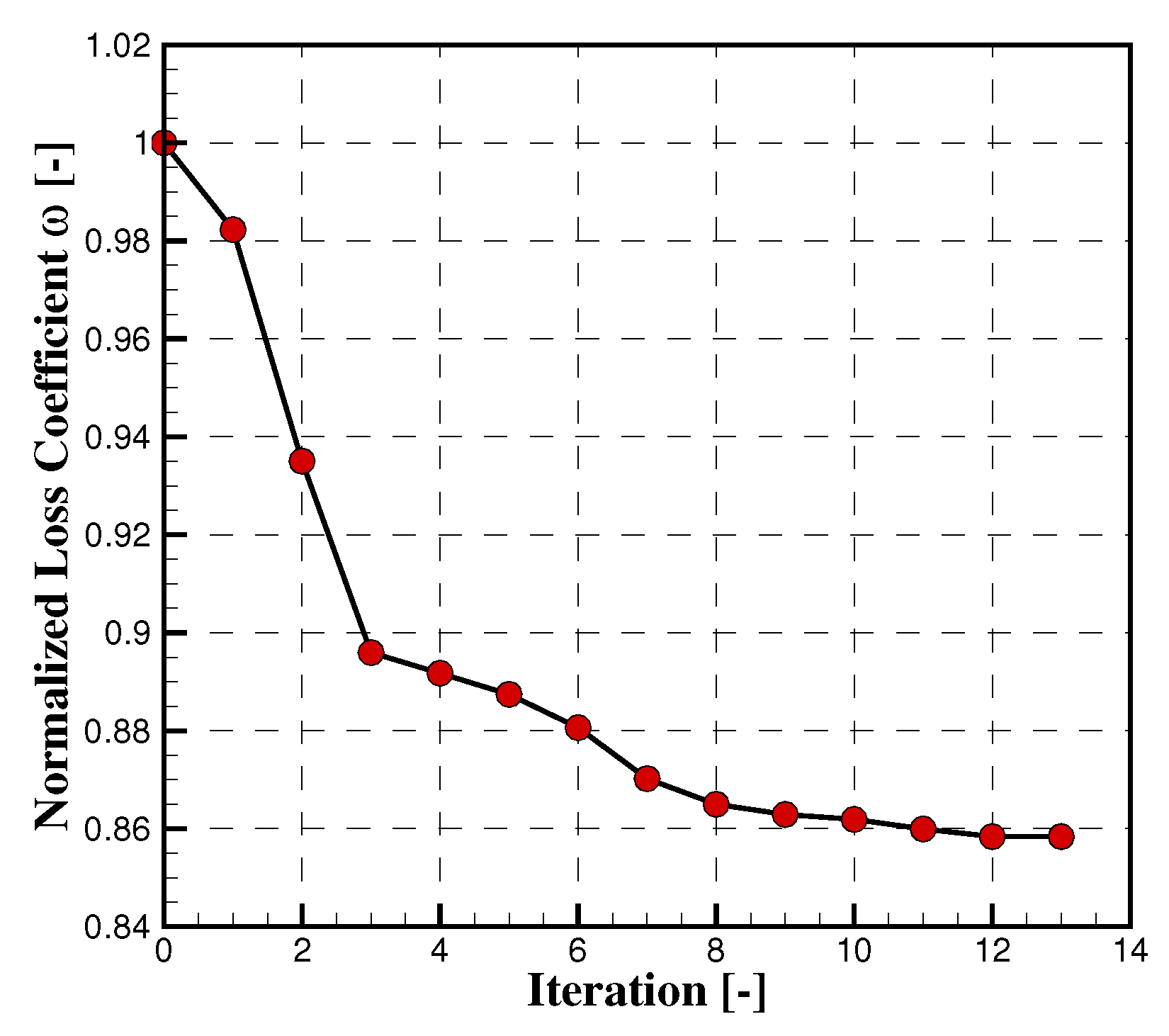

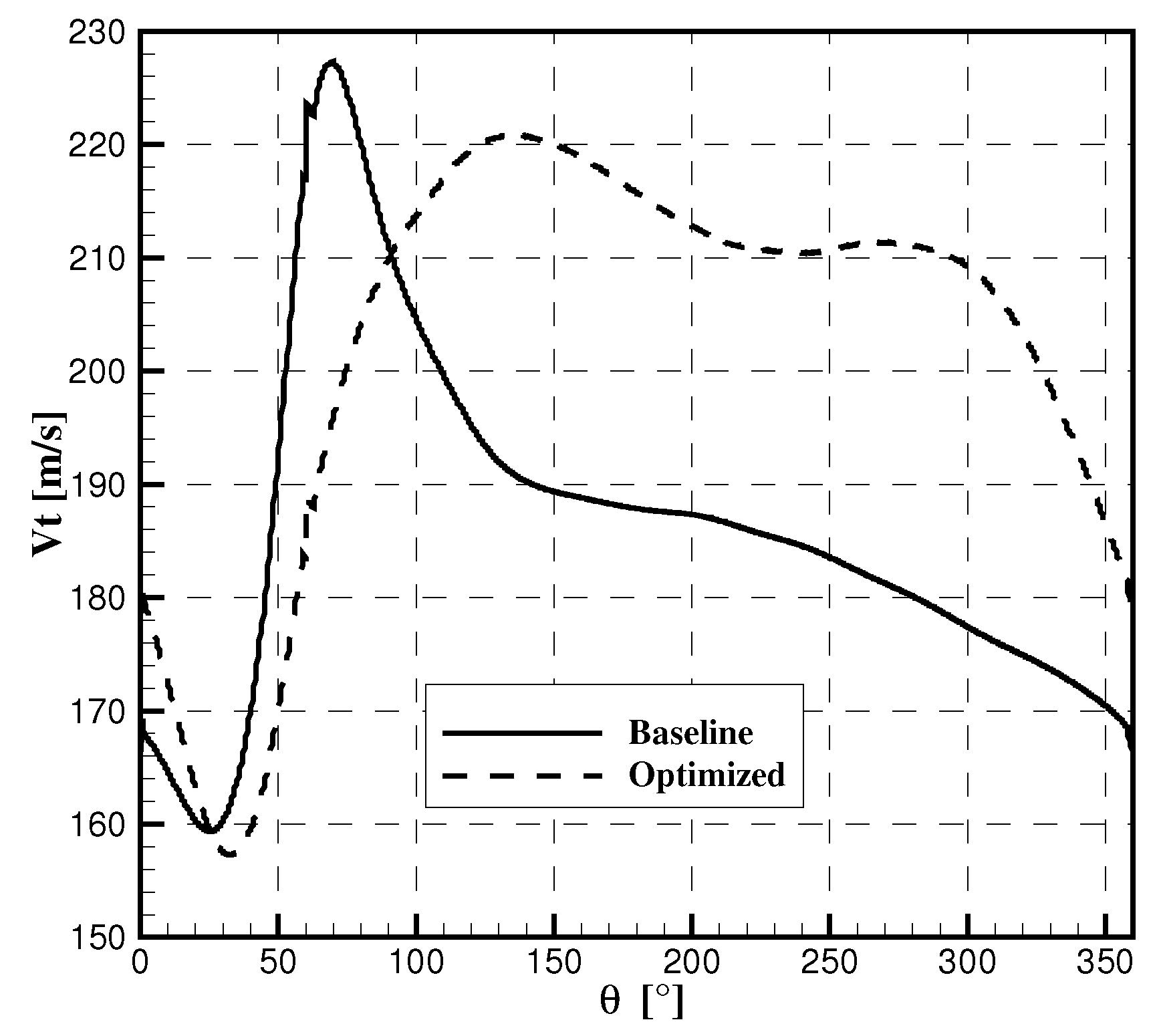

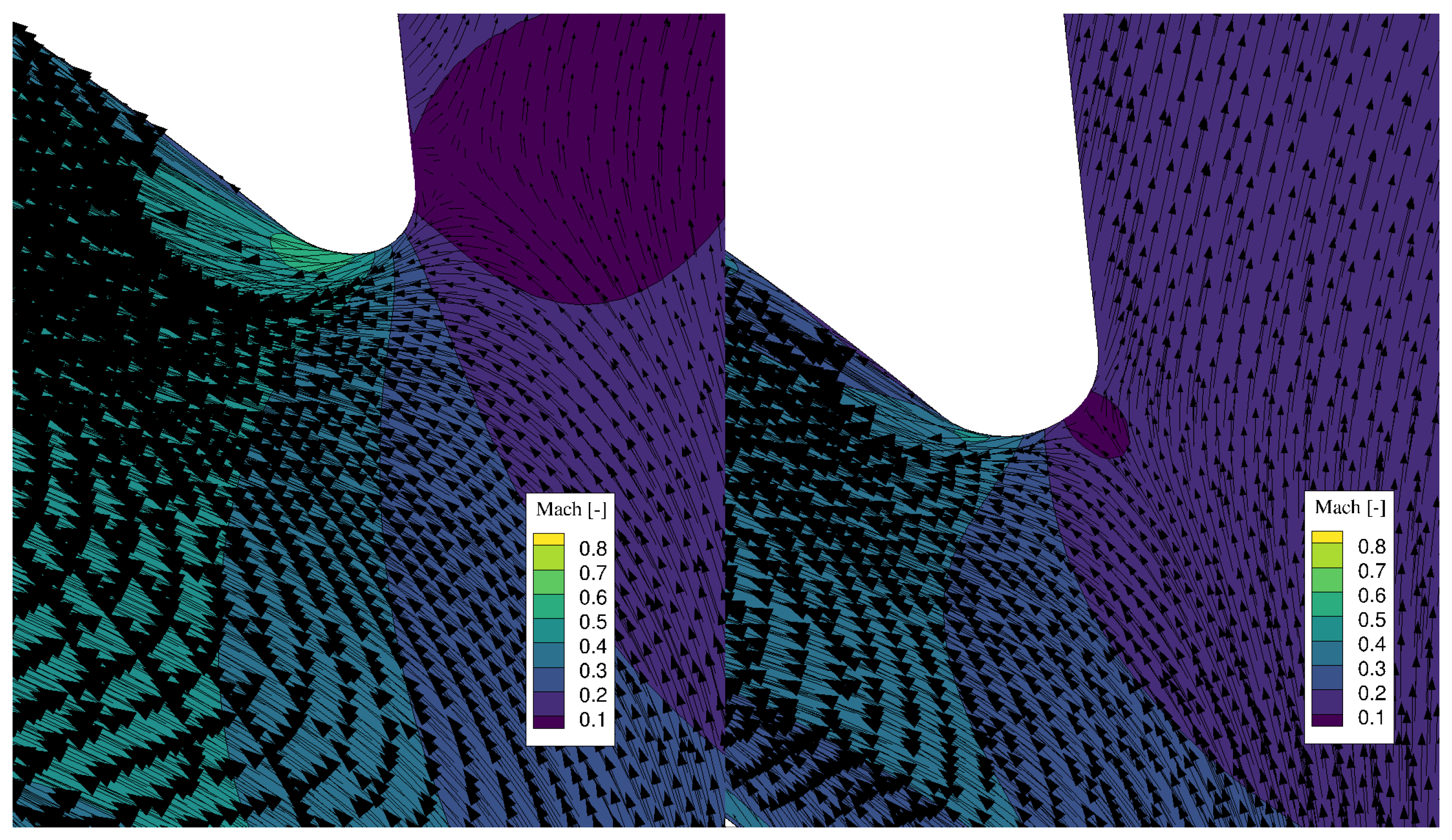

2.5. Optimization Results

| Index | Parameter Name | Baseline | Optimized | Units |

| 1 | Minimum volute radius | 0.023 | 0.017 | [m] |

| 2 | Wall height | 0.008 | 0.0074 | [m] |

| 3 | Wall fillet radius | 0.0025 | 0.001 | [m] |

| 4 | Wall radius | 0.195 | 0.195 | [m] |

| 5 | Inlet fillet radius | 0.001 | 0.0012 | [m] |

| 6 | Radius ratio point 2 | 1.4 | 1.22844 | [-] |

| 7 | Radius ratio point 3 | 1.6 | 1.45406 | [-] |

| 8 | Radius ratio point 4 | 1.7 | 1.72688 | [-] |

| 9 | Radius ratio point 5 | 1.75 | 2.06383 | [-] |

| 10 | Radius ratio point 6 | 1.9 | 2.22392 | [-] |

| 11 | Radius ratio point 7 | 2.1 | 2.26456 | [-] |

| 12 | Radius ratio point 8 | 2.3 | 2.35792 | [-] |

| 13 | Radius ratio point 9 | 2.5 | 3.08543 | [-] |

| 14 | Tongue radius | 0.005 | 0.0058 | [m] |

2.6. Updated Compressor Map

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| R | Radius |

| h | Height |

| x | Design variable |

| Y | Grid coordinates |

| U | Flow solution |

| Inlet flow angle | |

| p | Static pressure |

| T | Static temperature |

| Efficiency | |

| Pressure loss coefficient | |

| Static pressure recovery coefficient | |

| V | Absolute flow velocity |

| Pressure ratio | |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| RANS | Reynolds Averaged Navier-Stokes |

| SQP | Sequential Quadratic Programming |

| lb | Lower bound |

| ub | Upper bound |

| tot | Total |

| in | Inlet |

| out | Outlet |

| TT | Total-to-total |

| t | Tangential |

| r | Radial |

References

- Kim, J. H., Oh, K. T., Pyun, K. B., Kim, C. K., Choi, Y. S., and Yoon, J. Y., Design optimization of a centrifugal pump impeller and volute using computational fluid dynamics. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.2012,15032025. [CrossRef]

- Stepanoff, A. J.; Centrifugal and Axial Flow Pumps: Theory, Design, and Application; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, USA, 1993.

- Han, X., Kang, Y., Sheng, J., Hu, Y., & Zhao, W. Centrifugal pump impeller and volute shape optimization via combined NUMECA, genetic algorithm, and back propagation neural network.Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2020, 61(1), 381-409. [CrossRef]

- Ji, C., Wang, Y., and Yao, L., Numerical Analysis and Optimization of the Volute in a Centrifugal Compressor. In Challenges of Power Engineering and Environment; K. Cen, Y. Chi, F. Wang (Eds.); Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2007, pp. 1352–1356. [CrossRef]

- Huang J., Xu S., Liu H., and Wang X., Robust performance optimization of centrifugal compressor volute with a rectangular cross-section. In Proceedings of ASME Turbo Expo 2015: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Montreal, Canada, No. GT2015-42979, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Heinrich M., Schwarze R., Genetic Algorithm Optimization of the Volute Shape of a Centrifugal Compressor. International Journal of Rotating Machinery 2016, 13. [CrossRef]

- Eisenlohr, G., Krain, H., Investigation of the flow through a high pressure ratio centrifugal impeller. In Proceedings of ASMETurbo Expo 2002: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, No. GT2002-30394, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Chatel A., Verstraete T., Aerodynamic optimization of the SRV2 radial compressor using an adjoint-based optimization method. In Proceedings of ASME Turbo Expo 2022, Rotterdam, Netherlands, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vladimir D. Liseikin; Grid Generation Methods, 3rd ed.; Springer Cham: New-York City, USA, 2017.

- Thompson, J. F., Warsi, Z. U. A., and Mastin, C. W.; Numerical Grid Generation: Foundations and Applications; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985.

- Muller, L., Adjoint-Based Optimization of Turbomachinery With Applications to Axial and Radial Turbines. PhD Thesis, Universite libre de Bruxelles, Ecole polytechnique de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., An Improved Mixing-Plane Method for Analyzing Steady Flow Through Multiple-Blade-Row Turbomachine. Journal of Turbomachinery.2014,136(8). [CrossRef]

- Giles, Michael B., Non-Reflecting Boundary Conditions for the Euler Equations.AIAA Journal 1990,28, 2050–2058.

- Martins, J. R. R. A., Sturdza, P., and Alonso, J. J., The Complex-Step Derivative Approximation.ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2003, 29(3), 245–262. [CrossRef]

- Hottois R., Chatel A., Coussement G., Debruyn T., Verstraete T., Comparing gradient-free and gradient-based multi-objective optimization methodologies on the VKI-LS89 turbine vane test case. Journal of Turbomachinery. 2022, 145. [CrossRef]

- Rosemeier, J., Numerical Analysis of a Centrifugal Compressor Including a Vaneless Diffuser and a Volute. 2017.

- Van den Braembussche R.; Design and Analysis of Centrifugal Compressors; ASME Press, Wiley, 2019.

- Sun, Z., Zheng, X., Linghu, Z., Kawakubo, T., Tamaki, H., and Wang, B., Influence of volute design on flow field distortion and flow stability of turbocharger centrifugal compressors. In Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 233(3), 2019; 484-494. [CrossRef]

- Japikse D., Advanced diffusion levels in turbocharger compressors and component matching. In Proceedings of First Int. Conf. on Turbocharging and Turbochargers, London, United Kingdom, pp. 143-155, 1982.

- Hamed Alemi et al., Effect of the volute tongue profile on the performance of a low specific speed centrifugal pump. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy 2014, 229, 210-220. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).