1. Introduction

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is a key neuromodulator involved in the regulation of mood, cognition, and various physiological functions. Among its receptor subtypes, the 5-HT4 receptor (5-HT4R) plays crucial roles in mood regulation, memory, and food intake [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Due to its distinct cerebral distribution and physiological properties, 5-HT4R has emerged as a promising target for brain disorders, such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease, eating disorders, and Parkinson’s disease [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Preclinical studies show that 5-HT4R activation produces rapid antidepressant-like effects and enhances cognitive performance in rodent models [

1,

5,

6,

9,

10,

11,

12], yet the underlying neural mechanisms remain unclear.

5-HT4Rs are coupled to G-proteins that stimulate cAMP production, promoting neuronal excitability. This receptor subtype rapidly modulates synaptic transmission and facilitates synaptic plasticity, including learning-induced dendritic spine growth in the hippocampus (HPC) [

13,

14] - processes that are essential for learning and memory. In both humans and rodents, 5-HT4Rs are predominantly expressed in the basal ganglia, with lower levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, where they localize to pyramidal neurons, interneurons, and presynaptic terminals [

15]. In the human frontal cortex, receptor binding exhibits a distinct laminar pattern, with higher expression in superficial layers [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

We investigated the cellular mechanisms underlying the pro-cognitive effects of 5-HT4R activation within hippocampal-prefrontal pathways, a key circuit for learning and memory. Both regions receive dense serotonergic innervation from the median and dorsal raphe nuclei, respectively, and express multiple serotonin receptor subtypes, including 5-HT4Rs [

21,

22,

23]. In mouse models of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, hippocampal-prefrontal neural dynamics are disrupted alongside cognitive deficits that can be restored by pharmacological and non-pharmacological cognitive-enhancing interventions [

24,

25,

26]. Notably, hippocampal-prefrontal circuits exhibit intrinsic synchronization within the theta (8–12 Hz) and gamma (30–100 Hz) frequency ranges, which are critical for cognitive function. Our recent findings demonstrate that both the coordination and directionality of information flow at these frequencies strongly correlate with memory performance and are modulated by serotonin receptors 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A, as well as by atypical antipsychotic drugs targeting these receptors [

27,

28].

In this study, we examined the distribution of 5-HT4Rs across key hippocampal regions (CA1, CA3, DG) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) subregions (cingulate, prelimbic, and infralimbic cortices). We also quantified their co-expression in parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (SST) interneurons, two inhibitory neuron subtypes essential for theta and gamma synchronization [

29,

30,

31]. Additionally, we investigated how the 5-HT4R agonist RS-67333—recognized for its memory-enhancing properties [

1,

5,

9,

10,

12]—modulates circuit dynamics between the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) and the prelimbic (PL) mPFC in both healthy mice and a schizophrenia-related cognitive impairment model induced by sub-chronic phencyclidine (PCP) treatment [

32,

33]. By integrating neurophysiological and anatomical data from mice with intact and impaired memory function, this study provides novel insights into the role of 5-HT4Rs in mood and cognition, offering a foundation for future therapeutic strategies targeting these receptors in brain disorders.

3. Discussion

We investigated the neural substrates underlying the pro-cognitive effects of 5-HT4R activation in hippocampal-prefrontal pathways at both anatomical and functional levels. We report that 5-HT4Rs are not only expressed by pyramidal neurons in the HPC and mPFC, but also by 30 to 60% of PV interneurons and 15% of hippocampal SST interneurons. Behaviorally, the 5-HT4R partial agonist RS-67333 rescued long-term recognition memory deficits in the sPCP mouse model of schizophrenia but had no impact on healthy mice. At the neurophysiological level, RS-67333 attenuated sPCP-induced increases in delta oscillations and associated cross-frequency coupling in both the CA1 area of the HPC and the PL mPFC without affecting the circuit’s connectivity.

Our findings expand the expression map of the 5-HT4R protein in the mouse brain [

34]. The immunohistochemical protocol was refined to detect 5-HT4R staining in brain regions with low expression. Not only did we detect high expression levels in the caudate-putamen and mossy fibers, as previously described [

10,

16,

34], but we were able to track individual 5-HT4R+, PV+ and SST+ fibers with high signal-to-noise ratio. We report that, in addition to pyramidal neurons, 30% to 60% of PV+ interneurons co-express 5-HT4Rs in hippocampal CA1, CA3, and DG regions, whereas in prefrontal ACC, PL, and IL regions it was between 30% and 40%. Co-labeling in SST+ interneurons was much lower, around 15% in the HPC and less than 10% in the mPFC. We note that 5-HT4R staining in individual SST+ cells of the mPFC was at the limit of our detection levels. Therefore, it is plausible that expression of 5-HT4Rs in SST+ neurons has been underestimated in both the HPC and the mPFC. Furthermore, considering the extensive arborization of individual SST+ cells in these areas, with broad staining in layer 1, a role for 5-HT4Rs in this population may not be negligible. Future studies should clarify how low levels of receptor expression impact signaling in individual neurons and how this affects neural network activities. We also confirmed a distinct receptor lamination in the mouse cingulate and prelimbic cortices, with denser expression in layers 2/3, as reported in the human frontal cortex [

17]. Our findings are in contrast with results from the rat brain, where 5-HT4R mRNA expression was reported in hippocampal and cortical glutamatergic neurons, but not in GABAergic interneurons [

15,

18,

34].

RS-67333 was administered acutely before the familiarization phase of the NOR task to strengthen the acquisition of new memories, as previously reported for other pro-cognitive compounds in the sPCP model of schizophrenia [

33,

35]. This strategy was successful in rescuing memory performance of sPCP-treated mice, but had no effect in healthy conditions, suggesting a restorative rather than an enhancing role. However, chronic RS-67333 administration has been shown to improve recognition memory in mice [

9], indicating that prolonged 5-HT4R activation may enhance normal memory function. While the rescue of STM by RS-67333 was variable, LTM was consistently restored across treated animals. Notably, higher doses of RS-67333 (5.0 and 10.0 mg/kg) facilitate both STM and LTM in rats [

1], suggesting a dose-dependent effect on STM. We have previously shown impaired LTM for several weeks following sPCP treatment [

26,

28], thus RS-67333-mediated memory improvement cannot be merely explained by its testing a week after saline.

Importantly, 5-HT4R activation exerted calming effects during the epoch preceding the familiarization phase, suggesting that emotional mechanisms may have also contributed to the actions of RS-67333. However, the fact that RS-67333-mediated pro-cognitive effects were more consistently observed 24h after its administration indeed suggest an effect of 5-HT4Rs on the molecular mechanisms underlying memory acquisition and consolidation and not merely an anxiolytic effect. We conclude that a combination of emotional and cognitive mechanisms may contribute to 5-HT4R-mediated memory-rescuing actions. These findings align with preclinical studies showing that 5-HT4R activation can alleviate cognitive deficits and exert rapid anxiolytic effects in rodent models of major depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease [

10,

12,

14,

41,

42]. Together, these results highlight the therapeutic potential of 5-HT4R activation in mitigating both cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

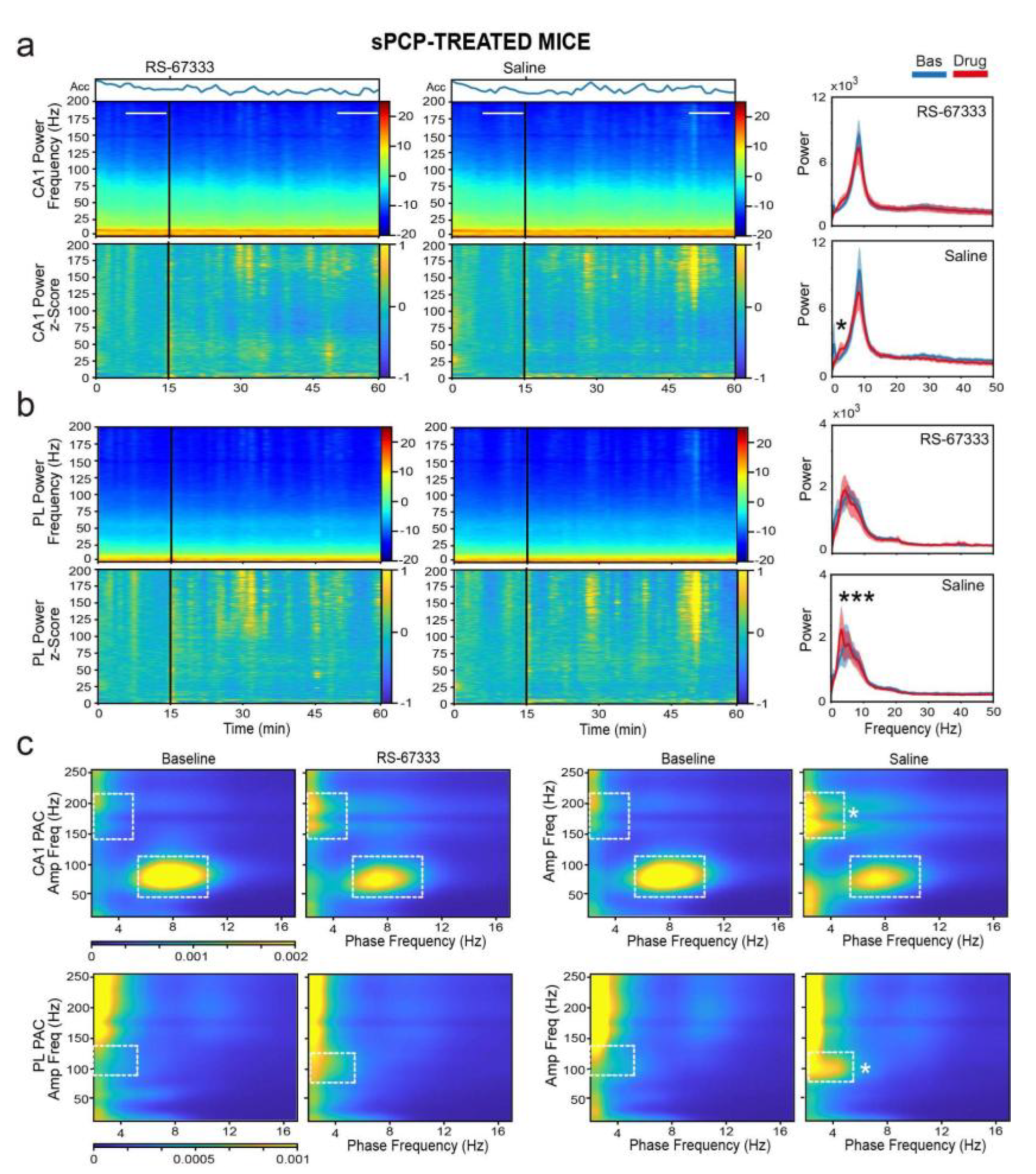

Consistent with its behavioral effects, 5-HT4R activation attenuated sPCP-induced disruptions in hippocampal-prefrontal neural dynamics without affecting healthy animals. Specifically, RS-67333 reduced abnormal delta oscillations in CA1 and PL and attenuated delta–high-frequency and delta–high-gamma coupling, respectively. These findings align with previous reports indicating that sPCP shifts hippocampal-prefrontal networks from intrinsic theta domains to pathological delta regimes [

26,

28,

39], supporting the hypothesis that large-scale delta connectivity contributes to cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia [

43,

44].

5-HT4Rs are well known to modulate functional synaptic plasticity essential for learning and memory in the HPC and PFC, including roles in long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), and excitatory-inhibitory balance regulation [

10,

41,

42,

45]. Thus, 5-HT4R activation was expected to robustly influence neural oscillations and circuit synchrony relevant to memory. However, its overall effects on local oscillations, cross-frequency coupling, and hippocampal-prefrontal circuit communication were modest—smaller than those reported for other serotonin receptors such as 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A [

27,

39]. This was unexpected given the consistent LTM improvements observed with RS-67333 in this study. Possible explanations include the relatively lower expression of 5-HT4Rs within this circuit and the low dose of the agonist used. Notably, 5-HT4R activation enhances acetylcholine release and increases cAMP and BDNF signaling [

10], all of which likely contributed to the observed memory improvements. It is also possible that 5-HT4R-mediated memory enhancement depends on rapid changes in neural dynamics that our current analytical methods could not detect. Future studies using alternative approaches will be needed to explore this further.

4. Materials and Methods:

Animals. Adult female and male C57Bl6/J mice (2–3 months old, 20–30 g) were obtained from Charles River. Mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions, including a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 60%, and a 12:12 light–dark cycle (lights off from 7:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m.). Food (standard pellet diet) and water were available ad libitum throughout the study, except during the brief behavioral and recording sessions, when the animals did not have access to food or water.

Immunohistochemistry. Mice were perfused with 4% PFA and the brains post-fixed in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4ºC. Then, brains were cryoprotected by immersing them in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4ºC until they sank. The brains were then frozen at -80º until they were processed. Brains were later sectioned at a thickness of 30 μm using a cryostat. Brain sections containing the HPC and the mPFC (at least three sections per area) were washed in PBS at RT (3 times for 10 minutes) and later incubated with blocking solution (5% Donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 100mM of glycine in PBS) [

46] overnight at RT. After blocking, the tissue sections were incubated in a solution containing the primary antibodies in blocking solution over-weekend at 4ºC and an extra hour at RT. The primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-5-HT4R (1:200, BIOSS BS2127R), sheep anti-PV (1:500, Invitrogen PA5-47693), and mouse anti-SST (1:500, GeneTex GTX71935). In the case of 5-HT4R and SST assays, the sections were incubated 60 minutes at RT with a solution of ReadyProbes™ Mouse on Mouse IgG Blocking Solution (30X) and PBS (Invitrogen R37621) and were washed in PBS at RT (3 times for 10 minutes) previous to the primary antibodies incubation to avoid nonspecific binding of antibodies to the tissue. Later, tissue sections were washed in PBS at RT (3 times for 10 minutes) and incubated with the secondary antibodies for 2 hours at RT in the dark. The secondary antibodies were: Goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor® 488 (1:1000, Abcam AB-150077), Donkey anti sheep Alexa Fluor™ 594 (1:1000, Invitrogen A-11016) and Goat anti mouse Alexa Fluor™ 594 (1:500, Invitrogen A-11005). Finally, the slices were cleaned in PBS (3 times for 10 minutes) and mounted with Fluoromount-G™ with DAPI (Invitrogen 00-4959-52) for nuclear staining, and covered with a coverslip. The sections were examined at 10x and 20x under a Dragonfly 200 confocal microscope system (Oxford Instruments Andor) using the Fusion software (version 2.4.0.14; Oxford Instruments) and at 63x with a Stellaris 8 DRIVE confocal microscope system (Leica Microsystems) using the Leica Application Suite X software (version 4.6.1.27508; Leica Microsystems). Negative control experiments with no primary antibodies were conducted to confirm specificity of the stainings. The images were visualized and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Surgical procedures. Mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. Anesthesia was maintained between 0.5–2% throughout the procedure. Small craniotomies were drilled above the hippocampus (HPC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Several micro-screws were inserted into the skull to stabilize the implant, with one positioned over the cerebellum serving as the general ground. Stereotrodes, composed of two twisted strands of 25 μm tungsten wire (Advent, UK) insulated with heat shrink tubing, were implanted unilaterally in the prelimbic (PL) region of the mPFC (AP: 1.5, 2.1 mm; ML: ± 0.6, 0.25 mm; DV: -1.7 mm from bregma) and the CA1 area of the dHPC (AP: -1.8 mm; ML: -1.3 mm; DV: -1.15 mm). Neural activity was monitored during electrode placement to confirm accurate targeting of the CA1 region. Additionally, three reference electrodes were implanted in the corpus callosum and lateral ventricles (AP: 1, 0.2, -1; ML: 1, 0.8, 1.7; DV: -1.25, -1.4, -1.5, respectively). At implantation, electrode impedances ranged from 100–400 kΩ. Electrodes were secured with dental cement and connected to an adaptor for integration with the recording system. Postoperatively, mice were given at least one week to recover, during which they were closely monitored and received analgesia and anti-inflammatory treatments. Before experiments commenced, animals were handled and habituated to the recording cable. Following the completion of experiments, electrode placements were histologically verified using Cresyl violet staining, and data from misplaced electrodes were excluded from analysis.

Novel object recognition test (NOR). Recognition memory was assessed using a custom-designed T-maze, as previously reported [

24,

26,

28]. The maze was constructed from aluminum with wider and higher arms than standard mazes (8 cm wide × 30 cm long × 20 cm high) and was shielded and grounded to accommodate electrophysiological recordings. It was positioned on an aluminum platform to minimize noise interference. Novel-familiar object pairs were validated as described in [

47], and the arm in which the novel object was placed was randomized across trials. The task consisted of a habituation phase, familiarization phase, short-term memory test (STM), and long-term memory test (LTM), each lasting ten minutes (

Figure 4b). During habituation, mice explored the maze without objects. After a one-hour interval, when electrophysiological recordings were conducted in an open field, they underwent the familiarization phase, where two identical objects were placed at the end of the lateral arms. STM and LTM tests were conducted 3 minutes and 24 hours later, respectively, with one familiar object and one novel object placed in the maze. Exploratory events were timestamped using TTL pulses sent to the acquisition system, allowing precise quantification of visit number and duration. Typically, initial visits and interactions with novel objects were longer compared to later visits and interactions with familiar objects [

26].

Pharmacology. RS-67333, a potent and highly selective 5-HT4R partial agonist, was obtained from Tocris Bioscience© and dissolved in saline solution (0,9% NaCl). It was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Phencyclidine (PCP), a non-competitive NMDAR (N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor) antagonist, was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck. It was administered subcutaneously (s.c.) at a dose of 10 mg/kg for 10 days (Monday to Friday over two consecutive weeks), as previously described [

26].

Neurophysiological recordings and data analyses. Electrophysiological recordings were conducted between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., during the light cycle of housing, in freely-moving mice exploring their home cages (369 x 165 x 132 mm). Animals did not have access to food or water during the recording sessions but had food and water available just before and after each experiment. All the recordings were carried out with the Open Ephys system at 0.1-6000 Hz and a sampling rate of 30 kHz with Intan RHD2132 amplifiers equipped with an accelerometer. The home cage was moved from the housing room to the experimental room within the animal facility where recordings were implemented. One or two animals were recorded simultaneously in separate cages and electrophysiological setups in the same room.

Recorded signals from each electrode were detrended, notch-filtered to remove power line artifacts (50, 100, 150 and 200 Hz) and decimated to 1kHz offline to obtain local field potentials (LFPs). Noisy electrodes detected by visual inspection from individual channel spectrograms were not used. Power spectral density results were calculated using the multi-taper method from the spectral_connectivity package in Python (time-half-bandwidth product = 5, 9 tapers, 60s sliding time window without overlap). Spectrograms were constructed using consecutive Fourier transforms (scipy.signal.spectrogram function, 60s time window, no overlap, no detrend). A 1/f normalization was applied to power spectral density results, and power spectrograms were scaled to decibels for visualization purposes. The frequency bands considered for the band-specific analyses included: delta (2-5 Hz), theta (8-12 Hz), beta (18-25 Hz), low gamma (30-48 Hz), high gamma (52-100 Hz), and high frequencies (100-200 Hz, 100-150 Hz, and 150-200 Hz).

Phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) was measured with a Python implementation of the method described in Tort et al. (phase frequencies = [0, 15] with 1 Hz step and 4 Hz bandwidth, amplitude frequencies = [10, 250] with 5 Hz step and 10 Hz bandwidth) [

48]. The length of the sliding window was 300s for the overview plots and 60s for the quantifications, without overlap. PAC quantification results were obtained by averaging the values of selected areas of interest in the comodulograms. These areas were: theta-high gamma comodulation in CA1 (phase: 5-10 Hz, amplitude: 50-100 Hz), delta-high gamma in PL (phase: 2-6 Hz, amplitude: 75-100 Hz), and theta-high frequency also in PL (phase: 4-10 Hz, amplitude: 150-200 Hz).

Prefrontal-hippocampal phase coherence was estimated via the weighted phase-lag index (wPLI, Butterworth filter of order 3), a measure of phase synchronization between areas aimed at removing the contribution of common source zero-lag effects that allowed us to estimate the synchronization between the PFC and the HPC mitigating source signals affecting multiple regions simultaneously [

27,

49,

50,

51]. PLI spectra were built applying the previous function multiple times with a 1 Hz sliding frequency window (using Butterworth bandpass filters of order 3), and PLI spectrograms were generated applying the PLI spectra function over a 60s sliding window (without overlap). In addition, we calculated the flow of information between areas with the phase slope index (PSI) with a Python translation of MATLAB’s data2psi.m (epleng = 60s, segleng = 1s) from [

40]. PSI spectrograms and spectra were constructed with the same strategy as PLI plots but using a 2 Hz sliding frequency window. All the results (LFP power, local and circuit PAC and PFC-HPC wPLI) are provided as z-scores with respect to baseline statistics (i.e., data is demeaned by the baseline mean and then normalized by the baseline standard deviation).

We used the accelerometer’s signals to evaluate the effects of the drugs on general mobility of mice. We found that the variance of the acceleration module (Acc), which quantifies the variation of movement across the three spatial dimensions, was largest during exploration and decreased as the animals were in quiet alertness or sedation. More specifically, we calculated the instantaneous module of raw x, y and z signals from which we measured the variance of 1-minute bins [

24]. The Acc results were presented as a ratio to the highest value in the baseline condition of the respective experiment.

Statistical analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using JASP open-source software. To assess memory performance under healthy conditions, we used Student’s T-tests to compare discrimination indices (DIs) between saline and RS-67333 treatments. For evaluating changes in DIs before and after subchronic phencyclidine treatment, we conducted repeated-measures ANOVAs, with treatment (saline vs. RS-67333) as the independent factor and health status (healthy vs. sPCP-treated) as the repeated factor. For accelerometer measures (Acc) and electrophysiological biomarkers (power, phase-amplitude coupling [PAC], weighted phase-lag index [wPLI], phase slope index [PSI]), we applied repeated-measures ANOVAs, using baseline vs. drug (same recording session) as the repeated factor and treatment (saline vs. RS-67333, different sessions) as the between-subject factor. Data were quantified in 10-minute epochs (minutes 5–15 and 50–60 of the hour prior to the familiarization phase). The Bonferroni method was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Raw data were used for all statistical analyses, with statistical significance set at p ± 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.P.; Methodology, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N., C.L-C.; Software, T.G.; Formal Analysis, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N., C.L-C.; Investigation, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N., C.L-C.; Data Curation, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.V.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N.; Visualization, M.V.P., T.G., S.H-N.; Supervision, M.V.P. and T.G.; Project Administration, M.V.P.; Funding Acquisition, M.V.P.

Figure 1.

Strong expression of 5-HT4Rs in caudate-putamen and mossy fibers, and lower levels in HPC and mPFC. (a) High levels of 5-HT4Rs were detected in patches within the caudate-putamen and in individual mossy fibers within the hippocampal formation. Images were taken at 63x. Scale bar = 25 µm. (b) In the HPC, the strongest expression was found in the granule cell layer of CA1. In CA3 and DG, the most evident staining pertained to mossy fibers (white arrows), whereas pyramidal cells of the granule layer expressed very low levels of 5-HT4Rs. Top: Mosaic images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 500 µm. Bottom: Images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 200 µm. (c) In the mPFC, a clear 5-HT4R-expressing layer 2-3 could be detected in the ACC and PL cortices (white arrows). Expression in the IL cortex was very low. Top: Mosaic images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 500 µm. Bottom: Images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Figure 1.

Strong expression of 5-HT4Rs in caudate-putamen and mossy fibers, and lower levels in HPC and mPFC. (a) High levels of 5-HT4Rs were detected in patches within the caudate-putamen and in individual mossy fibers within the hippocampal formation. Images were taken at 63x. Scale bar = 25 µm. (b) In the HPC, the strongest expression was found in the granule cell layer of CA1. In CA3 and DG, the most evident staining pertained to mossy fibers (white arrows), whereas pyramidal cells of the granule layer expressed very low levels of 5-HT4Rs. Top: Mosaic images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 500 µm. Bottom: Images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 200 µm. (c) In the mPFC, a clear 5-HT4R-expressing layer 2-3 could be detected in the ACC and PL cortices (white arrows). Expression in the IL cortex was very low. Top: Mosaic images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 500 µm. Bottom: Images taken at 20x. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Figure 2.

5-HT4R immunoreactivity in PV+ interneurons of the HPC and mPFC. Representative images of PV cells (red) expressing 5-HT4R (green) and DAPI counterstaining (blue) in the distinct subregions of the HPC (a) and the mPFC (b). Note mossy fiber staining in CA3 and low 5-HT4R immunofluorescence in the mPFC. Images were obtained at x63. Scale bar = 25 µm. (c) Quantification of 5-HT4R and PV immunofluorescence co-stainings in the distinct subregions of the HPC and mPFC. See

Table 1 for complementary information.

Figure 2.

5-HT4R immunoreactivity in PV+ interneurons of the HPC and mPFC. Representative images of PV cells (red) expressing 5-HT4R (green) and DAPI counterstaining (blue) in the distinct subregions of the HPC (a) and the mPFC (b). Note mossy fiber staining in CA3 and low 5-HT4R immunofluorescence in the mPFC. Images were obtained at x63. Scale bar = 25 µm. (c) Quantification of 5-HT4R and PV immunofluorescence co-stainings in the distinct subregions of the HPC and mPFC. See

Table 1 for complementary information.

Figure 3.

5-HT4R immunoreactivity in SST+ interneurons of the HPC and mPFC. (a) Representative images of SST cells (red) expressing 5-HT4R (green) and DAPI counterstaining (blue) in the distinct subregions of the HPC. (b) Representative examples of SST cells negative for 5-HT4Rs. Co-expression of SST and 5-HT4Rs in the mPFC was rare. Images were obtained at x63. Scale bar = 25 µm. (c) Quantification of 5-HT4R and SST immunofluorescence co-stainings in the distinct subregions of the HPC and mPFC. See

Table 1 for complementary information.

Figure 3.

5-HT4R immunoreactivity in SST+ interneurons of the HPC and mPFC. (a) Representative images of SST cells (red) expressing 5-HT4R (green) and DAPI counterstaining (blue) in the distinct subregions of the HPC. (b) Representative examples of SST cells negative for 5-HT4Rs. Co-expression of SST and 5-HT4Rs in the mPFC was rare. Images were obtained at x63. Scale bar = 25 µm. (c) Quantification of 5-HT4R and SST immunofluorescence co-stainings in the distinct subregions of the HPC and mPFC. See

Table 1 for complementary information.

Figure 4.

5-HT4R activation reduced sPCP-induced memory impairments in the sPCP model of schizophrenia. (a) Experimental protocol. Mice were implanted with recording electrodes in the CA1 and PL. During the first post-recovery week, mice were handled and became familiar with the recording cable. RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline were injected before the familiarization phase of the NOR task in two consecutive weeks before and after subchronic treatment with PCP (10 mg/kg, s.c., 5+5 injections). (b) The four phases of the NOR task. Electrophysiological recordings were performed for 1 hour prior to the familiarization phase. RS-67333 and saline were injected after a 15-minute baseline, 45 minutes before familiarization. (c) Effects of RS-67333 and saline on STM. 5-HT4R activation rescued (DI ⪬ 0.15) STM in four of 9 animals. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (RS-67333, health vs. sPCP, *p = 0.01; saline, health vs. sPCP, *** p < 0.001). (d) Effects of RS-67333 and saline on LTM. 5-HT4R activation rescued LTM in all animals (RS-67333, health vs. sPCP, p = 1; saline, health vs. sPCP, *** p < 0.001). Data are mean ± S.E.M.

Figure 4.

5-HT4R activation reduced sPCP-induced memory impairments in the sPCP model of schizophrenia. (a) Experimental protocol. Mice were implanted with recording electrodes in the CA1 and PL. During the first post-recovery week, mice were handled and became familiar with the recording cable. RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline were injected before the familiarization phase of the NOR task in two consecutive weeks before and after subchronic treatment with PCP (10 mg/kg, s.c., 5+5 injections). (b) The four phases of the NOR task. Electrophysiological recordings were performed for 1 hour prior to the familiarization phase. RS-67333 and saline were injected after a 15-minute baseline, 45 minutes before familiarization. (c) Effects of RS-67333 and saline on STM. 5-HT4R activation rescued (DI ⪬ 0.15) STM in four of 9 animals. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (RS-67333, health vs. sPCP, *p = 0.01; saline, health vs. sPCP, *** p < 0.001). (d) Effects of RS-67333 and saline on LTM. 5-HT4R activation rescued LTM in all animals (RS-67333, health vs. sPCP, p = 1; saline, health vs. sPCP, *** p < 0.001). Data are mean ± S.E.M.

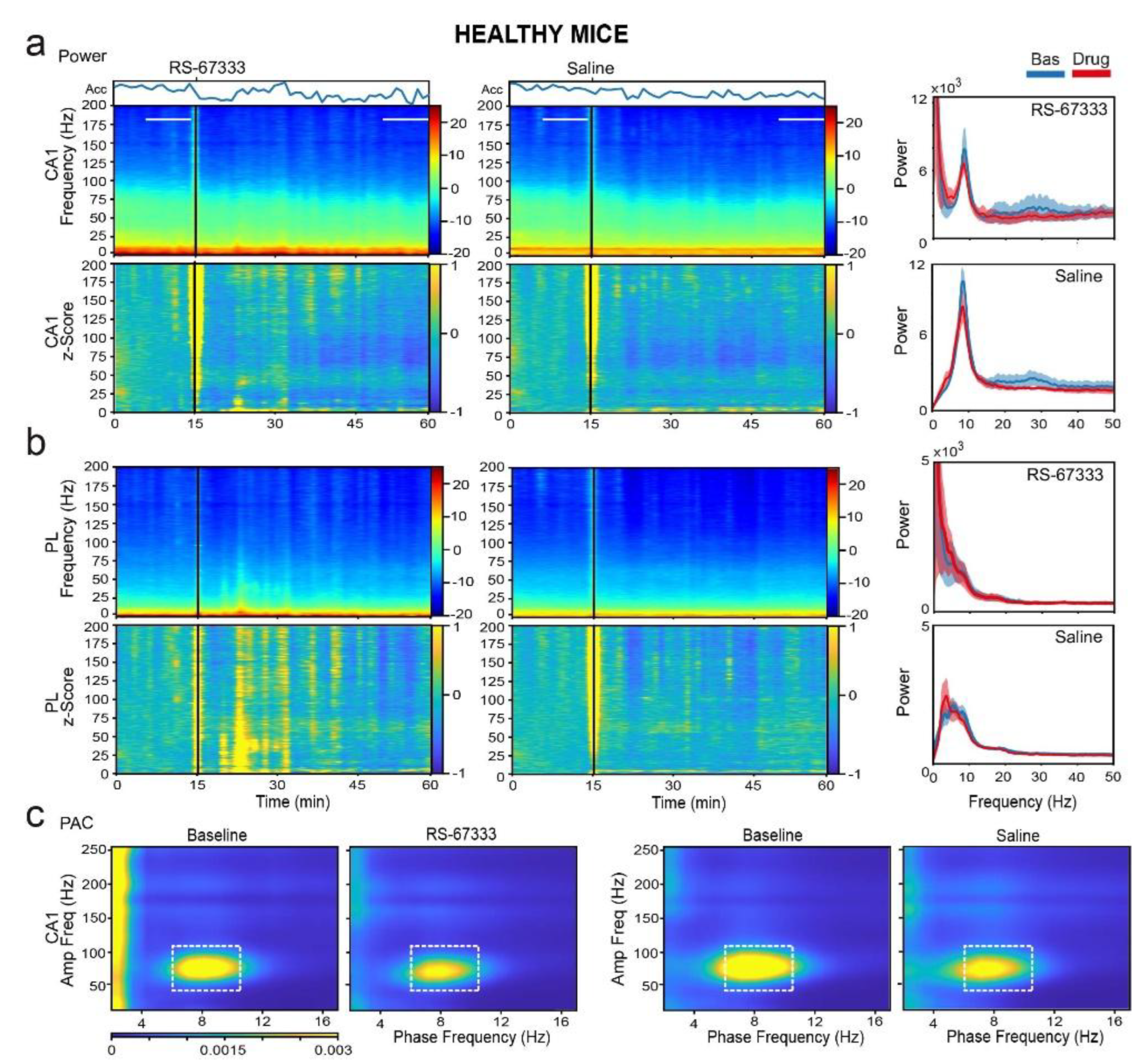

Figure 5.

RS-67333 does not alter local synchronization in CA1 and PL in healthy mice. (a) Power spectrograms (power per minute) and corresponding z-scores (lower panels) of signals in the CA1 after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. Quantification of the animals’ mobility (variance of the accelerometer, Acc) per minute is also shown. Power spectra of signals during the last 10 min of baseline are depicted in blue and signals from min 35 to 45 after RS-67333 administration (50-60 min since the start of the recordings) are illustrated in red. (b) Same analyses from PL signals. Power at middle frequencies (theta, beta, low and high gamma) decreased equivalently in both regions following RS-67333 and saline administrations. (c) Comodulation maps quantifying local cross-frequency coupling in CA1 for the 10-minute epochs selected above. Dashed squares mark theta-high gamma coupling. CA1 theta-gamma coupling decreased equivalently following RS-67333 and saline administrations. No coupling was observed in the mPFC (data not shown).

Figure 5.

RS-67333 does not alter local synchronization in CA1 and PL in healthy mice. (a) Power spectrograms (power per minute) and corresponding z-scores (lower panels) of signals in the CA1 after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. Quantification of the animals’ mobility (variance of the accelerometer, Acc) per minute is also shown. Power spectra of signals during the last 10 min of baseline are depicted in blue and signals from min 35 to 45 after RS-67333 administration (50-60 min since the start of the recordings) are illustrated in red. (b) Same analyses from PL signals. Power at middle frequencies (theta, beta, low and high gamma) decreased equivalently in both regions following RS-67333 and saline administrations. (c) Comodulation maps quantifying local cross-frequency coupling in CA1 for the 10-minute epochs selected above. Dashed squares mark theta-high gamma coupling. CA1 theta-gamma coupling decreased equivalently following RS-67333 and saline administrations. No coupling was observed in the mPFC (data not shown).

Figure 6.

RS-67333 mitigates sPCP-induced aberrant delta synchronization in CA1 and PL. (a) Power spectrograms (power per minute) and corresponding z-scores (lower panels) of signals in the CA1 after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. Lines depict the epochs selected for signal quantification. The animals’ mobility (Acc per minute) is also shown. Right panels: Power spectra of signals during the last 10 min of baseline are depicted in blue and signals from min 35 to 45 after RS-67333 administration (50-60 min since the start of the recordings) are illustrated in red. Delta power increased in CA1 more after saline than RS-67333. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (RS-67333 vs. saline, *p = 0.03). (b) Same analyses from PL signals. Delta power increased in PL after the injection of saline, but not RS-67333 (RS-67333 vs. saline, ***p < 0.001). (c) Comodulation maps quantifying local cross-frequency coupling in CA1 and PL for the 10-minute epochs selected above. Dashed squares mark intrinsic theta-gamma coupling in CA1 and sPCP-associated delta-high frequency coupling in CA1 and delta-high gamma coupling in PL (RS-67333 vs. saline, delta-high frequency and delta-high gamma coupling, *p = 0.02 and 0.045, respectively).

Figure 6.

RS-67333 mitigates sPCP-induced aberrant delta synchronization in CA1 and PL. (a) Power spectrograms (power per minute) and corresponding z-scores (lower panels) of signals in the CA1 after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. Lines depict the epochs selected for signal quantification. The animals’ mobility (Acc per minute) is also shown. Right panels: Power spectra of signals during the last 10 min of baseline are depicted in blue and signals from min 35 to 45 after RS-67333 administration (50-60 min since the start of the recordings) are illustrated in red. Delta power increased in CA1 more after saline than RS-67333. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (RS-67333 vs. saline, *p = 0.03). (b) Same analyses from PL signals. Delta power increased in PL after the injection of saline, but not RS-67333 (RS-67333 vs. saline, ***p < 0.001). (c) Comodulation maps quantifying local cross-frequency coupling in CA1 and PL for the 10-minute epochs selected above. Dashed squares mark intrinsic theta-gamma coupling in CA1 and sPCP-associated delta-high frequency coupling in CA1 and delta-high gamma coupling in PL (RS-67333 vs. saline, delta-high frequency and delta-high gamma coupling, *p = 0.02 and 0.045, respectively).

Figure 7.

RS-67333 does not affect hippocampal-prefrontal communication in sPCP-treated mice. (a) Time course of changes in wPLI (phase coherence) after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. dHPC-mPFC theta (8-12 Hz) and low gamma (20-40 Hz) coherence bands can be observed as red (high coherence) and light blue (moderate coherence) signals, respectively. Phase coherence was equivalent after the injection of RS-67333 and saline. (b) Time course of changes in PSI (circuit directionality). The intrinsic dHPC→mPFC theta and beta bands can be observed as dark and light red signals, respectively. Signal directionality was equivalent after the injection of RS-67333 and saline. c) Quantification of wPLI for the two experimental groups for the 10-minute epochs selected above. d) Corresponding quantification of PSI. Similar results were obtained during healthy conditions (data not shown).

Figure 7.

RS-67333 does not affect hippocampal-prefrontal communication in sPCP-treated mice. (a) Time course of changes in wPLI (phase coherence) after the administration of RS-67333 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and saline. dHPC-mPFC theta (8-12 Hz) and low gamma (20-40 Hz) coherence bands can be observed as red (high coherence) and light blue (moderate coherence) signals, respectively. Phase coherence was equivalent after the injection of RS-67333 and saline. (b) Time course of changes in PSI (circuit directionality). The intrinsic dHPC→mPFC theta and beta bands can be observed as dark and light red signals, respectively. Signal directionality was equivalent after the injection of RS-67333 and saline. c) Quantification of wPLI for the two experimental groups for the 10-minute epochs selected above. d) Corresponding quantification of PSI. Similar results were obtained during healthy conditions (data not shown).

Table 1.

Co-expression of 5-HT4Rs in PV+ and SST+ interneurons in HPC and mPFC subregions.

Table 1.

Co-expression of 5-HT4Rs in PV+ and SST+ interneurons in HPC and mPFC subregions.

Sub-

area |

Sex |

N PV |

PV+

Count |

% Co-

expression |

N SST |

SST+ Count |

% Co-

expression |

| CA1 |

Female |

5 |

28±3 |

53±10 |

2 |

14±6 |

25±14 |

| Male |

4 |

23±4 |

50±6 |

3 |

16±3 |

10±7 |

| All |

9 |

26±3 |

52±6 |

5 |

15±3 |

16±7 |

| CA3 |

Female |

5 |

19±2 |

45±8 |

2 |

14±9 |

21±15 |

| Male |

4 |

22±3 |

40±5 |

3 |

7±2 |

16±11 |

| All |

9 |

20±2 |

43±5 |

5 |

10±4 |

18±9 |

| DG |

Female |

5 |

4±1 |

70±14 |

2 |

14±9 |

8±9 |

| Male |

4 |

8±1 |

65±10 |

3 |

4±1 |

4±6 |

| All |

9 |

6±1 |

68±9 |

5 |

8±4 |

6±5 |

| ACC |

Female |

4 |

65±22 |

43±9 |

3 |

37±9 |

7±5 |

| Male |

2 |

51±17 |

43±9 |

3 |

29±6 |

4±3 |

| All |

6 |

60±14 |

43±7 |

6 |

33±5 |

6±3 |

| PL |

Female |

4 |

43±14 |

34±10 |

3 |

18±5 |

10±7 |

| Male |

2 |

37±9 |

29±4 |

3 |

17±6 |

4±4 |

| All |

6 |

41±8 |

32±6 |

6 |

18±4 |

7±4 |

| IL |

Female |

4 |

37±11 |

43±14 |

3 |

18±7 |

18±10 |

| Male |

2 |

46±12 |

42±8 |

3 |

17±3 |

6±3 |

| All |

6 |

40±8 |

43±8 |

6 |

17±4 |

12±6 |