1. Introduction

Posture control is required to ensure the body’s balance and safety in challenging conditions as is the case while wearing high heels. Specifically, increased heel height has been shown to negatively affect postural stability, mainly by inducing lumbar flattening and posterior pelvic tilt [

1,

2]. In addition, a decrease in pelvic, knee and ankle range of motion [

3,

4] is associated with manifestations of significantly increased magnitude and velocity of postural sway in both the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Further, the potential threat to the body’s postural balance while standing in high heeled shoes is accompanied by increased lower limb stiffness [

10,

11] as evidenced by a significant rise in the electromyographic activity of the triceps surae muscles along with increased co-contraction of the tibialis anterior and peroneus longus muscles [

12,

13].

On the other hand, postural control would provide a flexible and mechanically stable substrate to enable and facilitate the execution of concurrent cognitive tasks [

14,

15,

16]. Within this context, the underlying theoretical assumption is that available resources are limited and they have to be shared between the motor and cognitive tasks or performance will be compromised [

17,

18]. Balance control engages cognitive resources [

19,

20] that are required for the continuous utilization and reweighing by the brain of the integrated sensorimotor information provided by the proprioceptive, vestibular and visual channels in order to determine the magnitude of postural sway to efficiently preserve balance and safety [

21,

22,

23]. In healthy individuals, the cognitive resources devoted to postural balance control are largely automatically [

24,

25] while requiring varying degrees of attention depending on the difficulty of the task [

26,

27]. The continuous interaction between postural and perception-action tasks, defined as dual-tasking posture-cognition interference, is quiet complex with previous findings of dual task postural studies being inconsistent [

28,

29]. Specifically, there have been reported impairments in postural performance resulting from the diversion of the available attentional resources to the secondary cognitive task [

30,

31,

32,

33], whereas, decrements in cognitive task performance have been found due to the prioritization of balance safety, referred to as the “posture-first strategy” [

34,

35,

36]. The adoption of the ‘posture-first strategy’ depends on several factors such as the nature of the cognitive tasks, the instruction set, the choice of baseline conditions and, most importantly, the perceived level of postural threat [

14,

37,

38]. For example, a ‘posture-first strategy’ has been found during demanding locomotor activities at the expense of cognitive performance [

34,

35,

36], but not during less demanding conditions such as standing [

39,

40,

41]. Therefore, the issue of dual task cognitive-postural interference still remains perplexing. To the best of our knowledge there is no study where the effect of dual tasking has been considered in a challenging postural configuration like standing in high heels.

The goal of the study was to investigate the influence of concurrent demanding cognitive tasks on postural balance performance while wearing shoes with different heel heights in women. We hypothesized that heel height would impair postural balance performance and that the interferences of the concurrent cognitive demands on balance performance would be more pronounced in shoes with increased heel height. We used two challenging cognitive tasks on the recruited participants, as they require different types of brain processing and cognitive resources to perform. The first task required the repetition of a series of digits and is considered a mental tracking and working memory task [

42,

43], where the individual has to remember the exact order of appearance of a 10-digit string. The second cognitive task required the generation of a 4-word sentence under pre-specified search conditions and is classified as a verbal fluency task involving executive function and semantic memory processes [

42].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 21 healthy women aged 21 to 54 years old volunteered to participate. Inclusion criteria to the study were defined as follows: a) participants had to be non-wearers of high-heels, as determined by the frequency of wearing high-heeled shoes <2 days per week during the previous year [

8], and b) participants had to have not been systematically engaged in ball-room dancing activities (e.g., latin, flamengo) for the past 5 years, in order to eliminate the previously observed effect of habitual high-heel experience on postural balance [

7,

12]. Participants were asked about their medical history and were excluded if they reported a history of neuromuscular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular or severe systemic diseases, severe arthritis, or if they had been taking any medication for the above diseases, or any other medication with side-effects for postural balance in the last 6 months. Further, they were asked to complete the short self-answered International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [

44] in order to assess their physical activity level. The study’s experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport Science of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (approval number: 1542/09-10-2023), and all participants gave their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Experimental Protocol

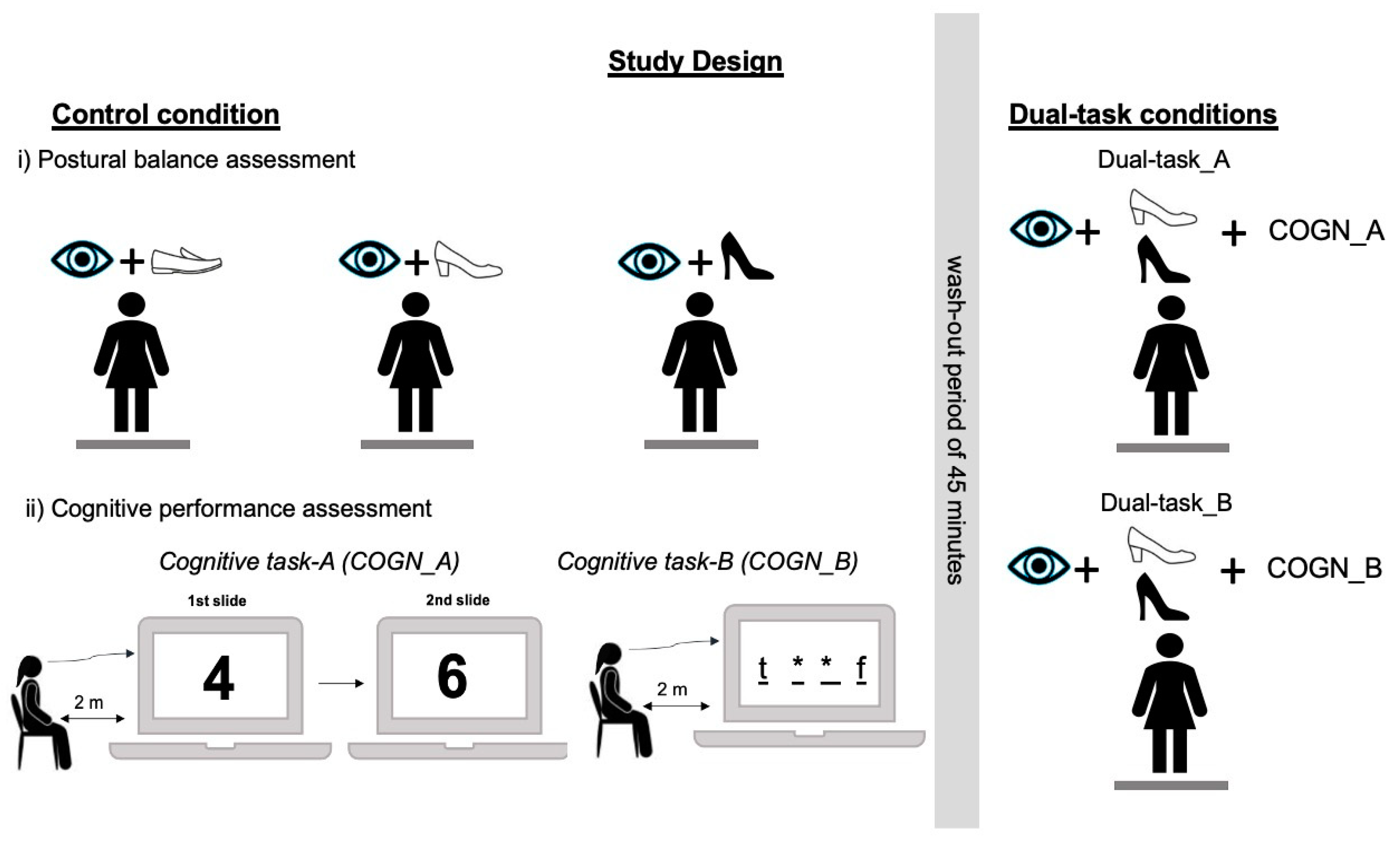

Participants’ postural balance was assessed in a quiet stance (a) without any further cognitive load (control condition) and (b) separately with two different concurrent cognitive tasks (dual-task condition) (

Figure 1). To complete those assessments, participants were required to participate in a 90 minutes single session, which took place in a quiet indoors space with appropriate light and temperature conditions in the university’s facilities. A wash-out period of 45-min duration between the control and dual-task conditions was used to limit any possible learning effect. Participants were instructed to abstain from any strenuous cognitive or physical activity 24 hours prior to the experimental session. All procedures were safe and conducted under supervision.

2.2.1. Postural Balance Assessment

Assessment of postural balance in the control condition included open-eyes quiet stance trials while wearing shoes of different heel heights, namely i) a low-heel (1-2 cm), ii) a medium-heel (7 cm), and iii) a high-heel (10.1 cm) (

Figure 2). In the dual-task conditions, postural balance assessment was carried out with the same quiet stance trials with the medium- and high-heel height shoes. Participants stood on a force plate (Wii, A/D converter, 24-bit resolution, 1.000 Hz, Biovision, Wehrheim, Germany) while maintaining a straight body posture with their arms hanging relaxed on the sides and their feet at hip-width distance. They had their gaze fixed on an imaginary point on the wall 2–3 m in front of them, while their heads were kept parallel to ground level. The order of shoe wearing was randomized in both the control and the dual-task condition. In each shoe wearing condition, three trials of 30 sec duration were recorded with a 1-min rest between shoe. For hygiene reasons, participants wore light stockings that were disposed afterwards. For the low-heel height, 3-4 different pairs of moccasin style leather shoes with rubber sole and wooden heel were used (

Figure 2A), whereas the medium- and high-heeled shoes were purchased by the same manufacturer in order to ensure the same type of shoe style (i.e., dress shoes with pump heels) and sole materials (

Figure 2B-C). Heel base dimensions were 1 cm in width and 1 cm in length for both the medium- and high-heel heights respectively. Prior to starting the experimental protocol, a brief shoe-fitting session was performed to ensure that all shoes were in appropriate ranges of size and fitted the participants comfortably.

Valid trials were considered those in which participants had been effective in maintaining their balance throughout the trial’s duration (i.e., 30 s). During the analysis, the recorded center of pressure (CoP) data from the force plate (Wii, A/D converter, 24-bit resolution, 1.000 Hz, Biovision, Wehrheim, Germany) were filtered using a 2nd bi-directional order digital low-pass Butterworth filter with a 15 Hz cut-off frequency and analyzed with MATLAB custom-made scripts (R2012a, 64 Bit; Mathworks, Natick, MA, United States) from the 2nd to the 27th second (Δt = 25 sec) of each 30 sec trial time. The assessment of postural balance performance is typically based on the CoP displacement, which derived values represent the geometrical location of the reaction force vector on the platform during quiet standing [

45]. Postural balance performance was determined by the following parameters: (a) CoP path length, defined as the sum of Euclidean distances between adjacent measurement points, and (b) CoP sway range, defined as the range (i.e., from minimum to maximum) of the CoP values in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions. To assess performance in the two-legged quiet stance trials, the average values of the two trials were used.

2.2.2. Concurrent Cognitive Tasks

Two cognitive tasks were used in the dual-task condition, hereafter defined as Cognitive Task-A (COGN_A) and Cognitive Task-B (COGN_B), to assess interference effects on postural balance performance. COGN_A referred to the assessment of short-term memory capacity elicited by a visual stimulus and processed by an phonological response [

43]. A series of strings based on 10 digit-task stimuli using Microsoft PowerPoint© were presented on a 15.6 inch, FHD (1.920 x 1.080 pixels) HP Pavillion Laptop, positioned at eye level in front of participants and at 2 meters distance. By using the “rand” function in Microsoft Excel©, random-number strings were generated, spanning from 0 to 9 and with repeated digits within a string being allowed. Due to participants’ age and educational level (i.e., all participants had a university degree) and after some pilot trials, we decided to use a 10-digit span for all participants, being set as the maximum number of digits in a string that a participant could correctly recall. After a familiarization trial, during which the participant was given instructions about the test procedure and a digit string to try, each participant, while being comfortably seated in front of the HP Pavillion Laptop, was presented with a new series of 10 slides at an automated velocity of slide transition of 1 sec duration. As already being described, each slide displayed a different digit using a 239-point Calibri font. During the slides transition (

Figure 1, lower left (A)), participants were instructed to mentally rehearse the 10-digit string that was eventually formed until the last slide disappeared and a black screen appeared. They were then asked to verbally recall the exact order of appearance of the digit string. The cognitive task performance was assessed based on the recorded number of errors, for example a score of 6 meant that the participant had correctly recalled the order of appearance of the first 4 digits in that trial [

43].

The second cognitive task (COGN_B) was the Sentence Completion task, which is a visual and verbal formation task of a 4-word sentence [

34]. This language-processing task is a valid task for the assessment of dual task interference effect because it is considered that one’s attentional and/or focusing resources would be more interferred by a motor task due to the visual processing and verbal coding required in the Sentence Completion task as compared to an attentional task of auditory modality [

46]. Four word sentences with four blanks were generated, two of which had a letter preceding the blank and two others had an asterisk. When a letter preceded the blank, the word must start with that letter, whereas any word could be used in the blanks with asterisks (

Figure 1). The order of letters and asterisks was random in the sentence and no names or locations were allowed to be used. After being provided with the necessary explanations and instructions as well as with 1-2 familiarization trials, participants were presented with a series of slides displaying 4-word sentences for a duration of 30 seconds, during which period they were instructed to verbally complete as many sentences as possible. COGN_B’s conditions were similar as in COGN_A (i.e., participant’s position with regards to laptop, Microsoft PowerPoint© specifications (e.g., type and font size)) except for the fact that one researcher (A.D.) manually changed the slides at the time instant the participant had completed forming the 4-word sentence being at display. Cognitive performance on each trial of the Sentence Completion task was based on the criteria of correctly using cued starting letters and creating a grammatically correct sentence. Therefore, for any sentence that was completed, the range of assigned points was between 0 to 6, with 1 point being assigned for each word meeting the criteria and 2 points being assigned for the sentence being grammatically correct [

34]. For example, the sentence “teacher asked students exam” would receive 4 points due to grammar errors of 2 points. All sentences from every participant were being recorded by a mobile phone (iPhone11) to be assessed afterwards and performance was determined by the total score of the completed sentences divided by the sum of those sentences. For example, in the case of a trial during which 10 sentences of 6 points each were completed, final score was 10 * 6 = 60/10 = 6. As a reference, the cognitive performance on both dual tasks was measured as the average of two trials while seated.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For the statistical analysis, we first checked for the normal distribution of the CoP parameters using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction. Testing of normality failed for the mediolateral CoP sway range in the control (p=0.017) and dual-task_A (p<0.001) and _B condition (p=0.024) for the medium-heel height shoe. Similarly, the normality check failed for that same parameter in the dual-task_A (p=0.019) and dual-task_B condition (p<0.001) for the high-heeled shoe. However, following visual inspection with quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots, the mediolateral CoP data in the above situations were normal with slight deviations. One-way ANOVA was used to test the effect of heel height (low, medium, high) on postural balance performance. In the event of a significant heel height effect, post hoc comparisons were performed. A 3 x 2 ANOVA with cognitive load (control, dual-task_A, dual-task_B) as a within-subjects factor and heel height (medium, high) as a between-subjects factor was performed on the two-legged CoP parameters. In case a significant main or interaction effect (cognitive load by heel height) was found, a Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparisons analysis was conducted. Finally, a one-way ANOVA was used to check for possible interferences of heel height (medium, high) on cognitive performance between the reference and the dual tasks. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS IBM v.21 and the significance level was set at a = 0.05. For the graphical representation of the outcomes, we used boxplots depicting the median and the 5th to 95th percentile as whiskers.

3. Results

The anthropometric characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. Based on the results from the IPAQ questionnaire, participants were classified as having a high physical activity level amounting to a weekly average of 3350 ± 2521 metabolic equivalents (METs) per minute.

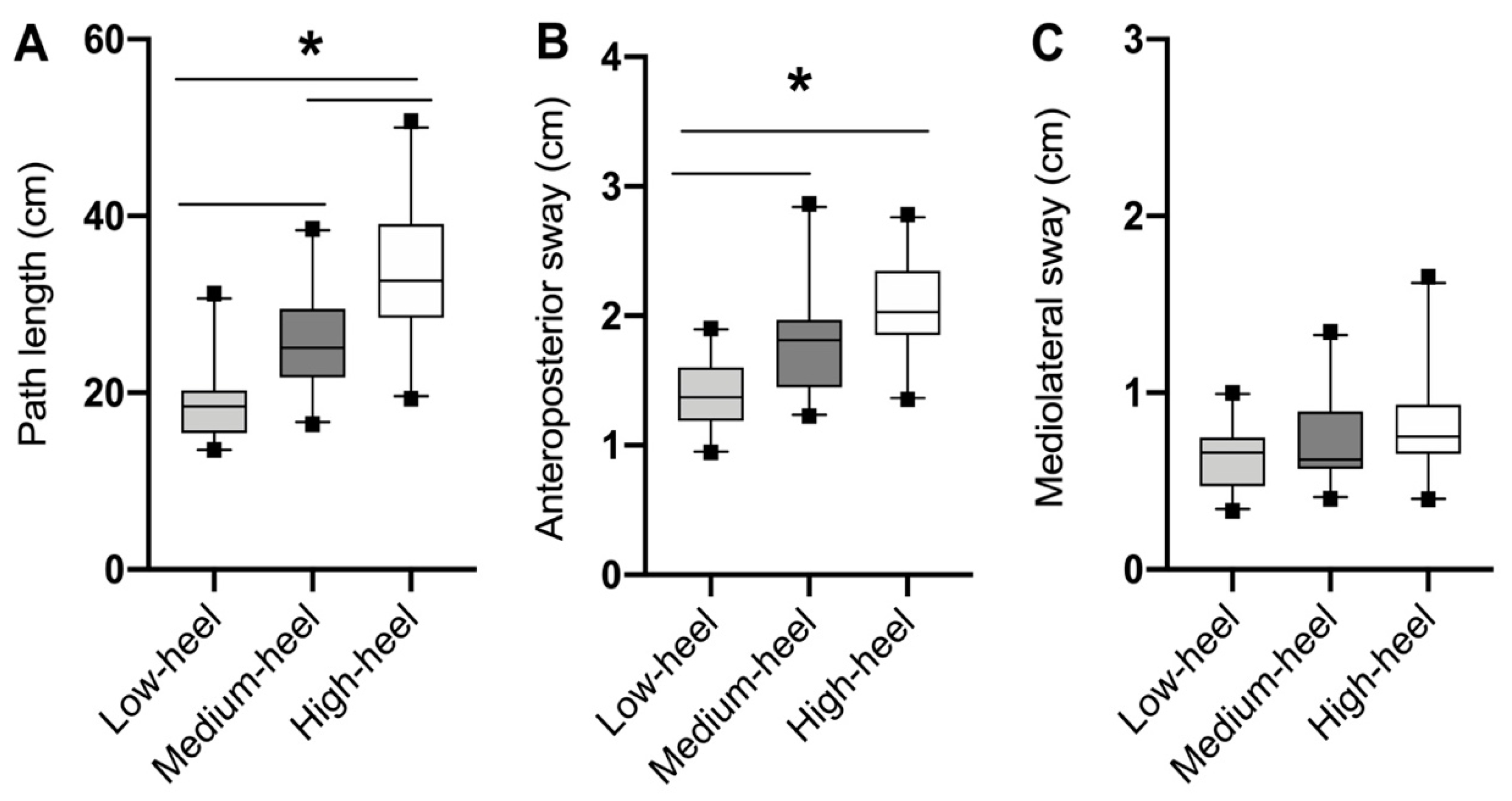

In the control condition, a significant main effect of heel height was found for the CoP parameters (

Figure 3). Specifically, path length was significantly increased (F

2,60 = 32.7, p<0.001) following the increase in heel height and post hoc comparisons showed significantly higher values between low- and medium-heel, low- and high-heel and medium- and high-heel height respectively (p<0.001 for all comparisons,

Figure 3A). Similarly, the increase of heel height significantly affected the anteroposterior CoP sway range (F

2,60 = 19.1, p<0.001) with the respective CoP values being significantly higher between the low- and medium-heel (p=0.001) as well as the low- and high-heel height (p<0.001) (

Figure 3B). Post hoc comparisons did not yield a statistically significant (p=0.068) difference between the medium and high heel height for the AP sway range. In the case of the CoP mediolateral sway range, there was not a significant effect of heel height (F

2,60 = 3.0, p>0.05) (

Figure 3C).

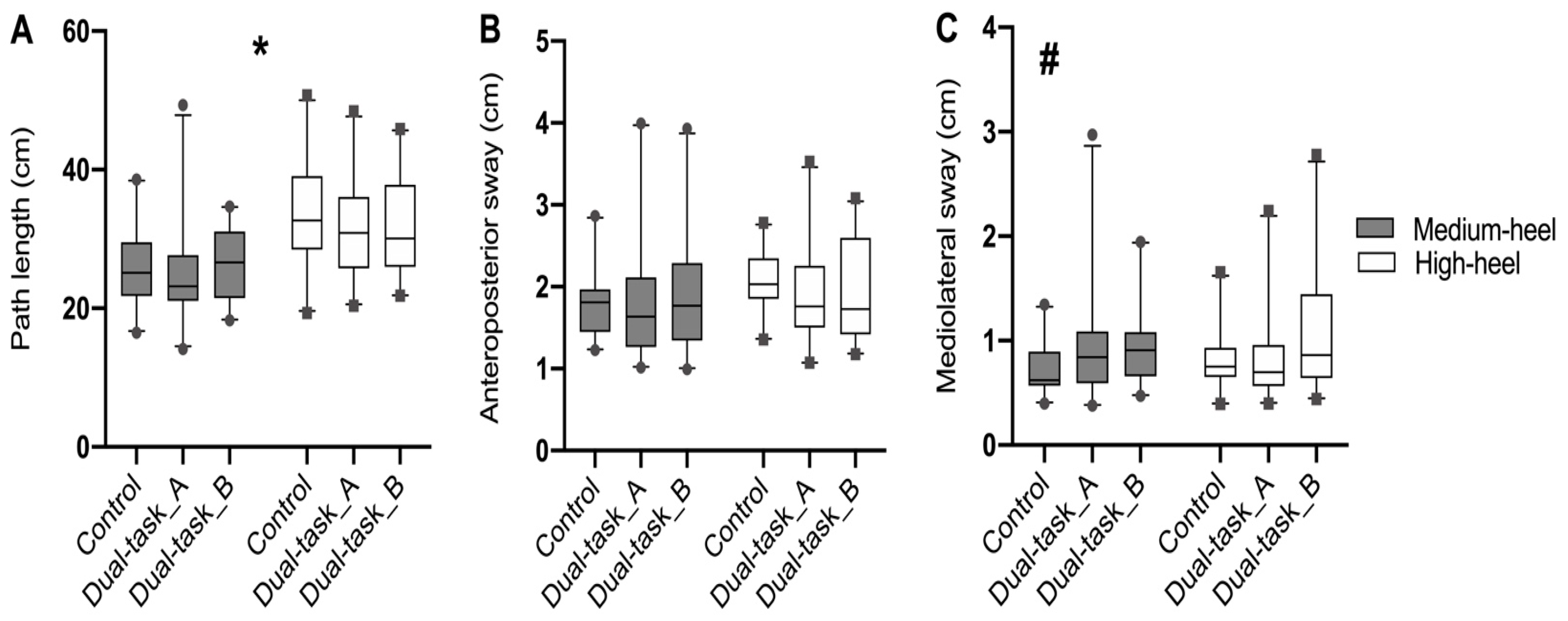

The two-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant main effect of cognitive load (F

2,75 = 1.642, p=0.202) and a non-significant interaction effect of cognitive load by heel height (F

2,80 = 0.994, p=0.375,

Figure 4A). There was a significant main effect of heel height (F

1,40 = 12.2, p=0.001) and post-hoc comparisons showed that path length values were significantly greater with the high compared to the medium-heels in all conditions (control: p=0.002, dual-task_A: p=0.022, dual-task_B: p=0.032) (

Figure 4A). In the anteroposterior range of CoP sway, there was no significant main effect of cognitive load (F

2,78 = 0.056, p=0.943) or heel height (F

1,40 = 0.218, p=0.643) and no significant interaction of cognitive load by heel height (F

2,80 = 1.288, p=0.281,

Figure 4B). In the mediolateral direction, a significant main effect of cognitive load was found (F

2,77 = 4.464, p=0.016), but post-hoc comparisons showed a significantly greater range of CoP sway (p<0.04) only for the medium-heeled shoe in the dual-task_B condition compared to the control condition (

Figure 4C). No statistically significant effect of heel height (F

1,40 = 0.082, p=0.776) and cognitive load by heel height interaction (F

2,80 = 1.237, p=0.296) was found in the mediolateral sway range (

Figure 4C).

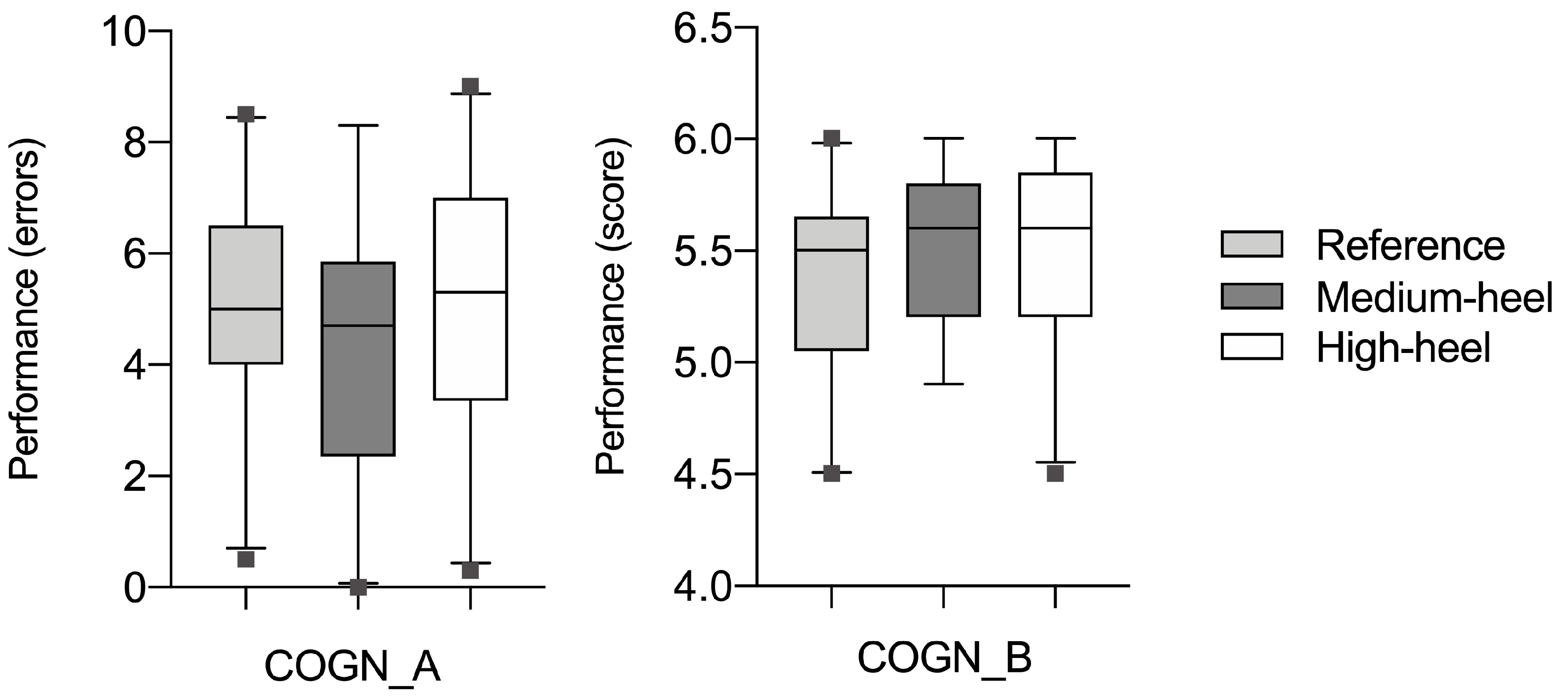

There was no difference in cognitive performance between the medium-heeled and high-heeled conditions compared to the reference sitting condition for both dual tasks (COGN_A: F

2,35 = 0.676, p=0.494; COGN_B: F

2,38 = 1.509, p=0.234,

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of shoe heel height and concurrent cognitive demands on postural balance performance in women. First, it was hypothesized that postural balance performance would be impaired due to heel height. The results on the CoP sway magnitude showed that balance performance decreased as heel height increased, thus confirming our first hypothesis. It was further hypothesized that the interference of concurrent cognitive demands on postural balance performance would be more pronounced during quiet standing in shoes with an increased heel height. The results did not show a significant systematic effect of cognitive load on balance performance, nor an interaction between cognitive load and balance performance at different heel heights, rejecting our second hypothesis.

It has been shown that an increase in heel height increases postural instability and induces a number of kinematic changes that place significant neuromuscular demands on the system. The main kinematic changes in the lower limbs when standing in high heels (i.e., typically over 4 cm) include lumbar flattening, posterior pelvic tilt and a significant decrease in the range of motion of the pelvis, knee and ankle joints [

1,

2,

3]. Heel elevation induces an increase in electromyographic activity of the lower limb muscles, particularly the calf muscles, which may increase lower limb stiffness to cope with the possible threat to postural stability [

10,

11], indicating a greater neuromuscular effort to balance control [

12]. Furthermore, the magnitude and velocity of CoP oscillation either in anteroposterior or mediolateral direction increased with increasing heel height, indicating a significant compromise in postural balance [

5,

7,

8]. We found a significantly greater CoP path length, up to 1.05 times greater in the medium and high heel shoes compared to the low heel shoes. The increased CoP path length was associated with greater anteroposterior sway magnitude, up to 75%, while mediolateral CoP sway was unaffected by heel height. In agreement with our results, Gerber et al. and Mika et al. [

5,

6] also reported that the increase in heel height mainly affected the CoP range in the anteroposterior direction, with no changes in the mediolateral direction. Taking these results together, we can argue that the greater neuromuscular demand of balance control with increased heel height is regulated with anteroposterior adjustments of the CoP. From a biomechanical point of view, the increased heel in shoes mainly reduces the mediolateral base of support and thus limits the possibility of mediolateral adjustments.

Everyday life is abundant with situations where cognitive and motor tasks occur simultaneously, and because cognitive resources are required for postural and motor control [

15,

47], there is an interaction between cognitive and motor tasks. This interaction between the two tasks referred to as dual-tasking interference has been shown to result in the diversion of attentional resources to the secondary cognitive tasks [

14,

32], thus rendering locomotor performance vulnerable. It has been reported that balance safety is prioritized at the expense of cognitive task performance [

34,

35], referred to as the “posture-first strategy” [

34]. Both cognitive tasks were considered as perceptually challenging. The participants performed the first task by recalling the exact order of the 10-digit string with an average of 5 ± 2 errors, while in the sentence completion task, their performance was ~92% successful (mean score 5.5 out of the maximum score of 6 per sentence). These scores show that both cognitive tasks demanded close to maximum performance from the participants, and we can argue that important cognitive resources were used. In cases where a concurrent cognitive task demands cognitive resources to perform the balance task, people prioritize postural safety [

34,

35,

36], so in our experiment a decrease in cognitive performance due to increased heel height would indicate a prioritization of postural balance. However, we did not find any differences in cognitive performance with increasing heel height in either of the cognitive tasks used, indicating that the cognitive load did not limit the cognitive resources needed for postural balance during the quiet stance.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the results did not show any systematic effect of dual-tasking interference on postural performance, thereby suggesting that the cognitive resources required for the execution of the cognitive tasks did not compete with the attentional resources involved with preserving balance while wearing shoes of elevated heel height. In agreement with our findings, Bustillo-Casero et al. [

48], Linder et al. [

39] and Siu and Woollacott [

40] did not find any change in postural sway during barefoot quiet stance in young adult participants while simultaneously executing complex cognitive tasks. Similarly, and closer to the age range of our middle-aged subjects, Bourlon et al. [

41] reported no dual-task interference on postural sway during the concurrent execution of cognitive reaction time tasks. Standing is a very common activity in daily life. It has been reported that approximately 41% of the time spent in activities or postures in daily life is spent standing [

49]. Experience-based anticipatory tonic muscle activation contributes to postural balance [

50] and may minimize the involvement of higher control centres. Nevertheless, we found a significant deterioration in postural balance with increasing heel height. The deterioration of postural balance with increasing heel height during standing, but without interference of cognitive load, may have important implications for daily life. Despite the availability of cognitive resources, the increase in balance challenge during standing due to increased heel height cannot be fully compensated for, and balance safety is more affected by mechanical demands.

A limitation of the current study is that the interaction between cognition and postural balance control was examined here in quiet standing, whereas a complementary inclusion of dynamic conditions, such as walking with high-heeled shoes, might have provided additional insight into the allocation of resources during dual-tasking. The included participants were very physically active which might have facilitated them in reaching the close to maximum performance in the cognitive tasks as compared to the same situation executed by healthy albeit not so physically active participants. Although we found a decrease in balance with increasing shoe heel height in our healthy participants, impaired participants may show interference in balance performance due to concurrent cognitive load during stance [

51].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the increased demand for balance control with increased heel height is mainly regulated by anteroposterior adjustments of the CoP, most likely because the increased heel in shoes reduces the mediolateral base of support, limiting mediolateral adjustments. Despite the cognitive demands of the cognitive tasks used, both cognitive and balance performance did not deteriorate in the dual task conditions, suggesting that cognitive load did not limit postural balance during quiet stance. Finally, the same deterioration in balance performance found with increasing shoe heel height in the single and dual task conditions suggests that balance in quiet stance is more affected by the increased mechanical demand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-E.N. and A.A.; methodology, M.-E.N. and A.D.; software, A.S.; validation, M.-E.N. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.D. and M.-E.N.; investigation, M.-E.N. and A.D.; resources, A.S. and A.A.; data curation, M.-E.N. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-E.N.; writing—review and editing, M.-E.N. and A.A.; visualization, M.-E.N. and A.A.; supervision, M.-E.N.; project administration, M.-E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Science, School of Physical Education and Sport Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (approval number: 1542, date of approval: 09-10-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the women who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COGN_A |

First cognitive short-term memory task |

| COGN_B |

Second cognitive verbal fluency task |

| CoP |

Centre of pressure |

References

- Opila, K.A.; Wagner, S.S.; Schiowitz, S.; Chen, J. Postural alignment in barefoot and high-heeled stance. Spine 1988, 13, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, R.E.; Williams, K.R. High heeled shoes: their effect on center of mass position, posture, three-dimensional kinematics, rearfoot motion, and ground reaction forces. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994, 75, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.X.; Wang, L. Influences of heel height on human postural stability and functional mobility between inexperienced and experienced high heel shoe wearers. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkunat, T.; Buck, F.M.; Jentzsch, T.; Simmen, H.P.; Werner, C.M.; Osterhoff, G. Influence of high-heeled shoes on the sagittal balance of the spine and the whole body. Eur Spine J 2016, 25, 3658–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, S.B.; Costa, R.V.; Grecco, L.A.; Pasini, H.; Marconi, N.F.; Oliveira, C.S. Interference of high-heeled shoes in static balance among young women. Hum Mov Sci 2012, 31, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, A.; Oleksy, Ł.; Kielnar, R.; Świerczek, M. The influence of high- and low-heeled shoes on balance in young women. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2016, 18, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wan, F.K.W.; Yick, K.L.; Yu, W.W.M. Effects of heel height and high-heel experience on foot stability during quiet standing. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada-Yanagawa, A.; Sasagawa, S.; Nakazawa, K.; Ishii, N. Effects of Occasional and Habitual Wearing of High-Heeled Shoes on Static Balance in Young Women. Front Sports Act Living 2022, 4, 760991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truszczyńska, A.; Trzaskoma, Z.; Stypinska, Z.; Drzal-Grabiec, J.; Tarnowski, A. Is static balance affected by using shoes of different height? Biomed Hum Kinet 2016, 8, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, I.M.; Ghédira, M.; Gracies, J.M.; Hutin, É. Postural stability in young healthy subjects - Impact of reduced base of support, visual deprivation, dual tasking. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2017, 33, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dault, M.C.; Geurts, A.C.; Mulder, T.W.; Duysens, J. Postural control and cognitive task performance in healthy participants while balancing on different support-surface configurations. Gait Posture 2001, 14, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapsari, V.D.; Xiong, S. Effects of high heeled shoes wearing experience and heel height on human standing balance and functional mobility. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A.; Megido-Ravid, M.; Itzchak, Y.; Arcan, M. Analysis of muscular fatigue and foot stability during high-heeled gait. Gait Posture 2002, 15, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraizer, E.V.; Mitra, S. Methodological and interpretive issues in posture-cognition dual-tasking in upright stance. Gait Posture 2008, 27, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.V.; Horak, F.B. Cortical control of postural responses. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2007, 114, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, G.E.; Stoffregen, T.A. Affordances as constraints on the control of stance. Hum Mov Sci 1988, 7, 265–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D. Processing resources and attention. In Multiple-Task Performance, 1st ed.; Damos, D., Ed.; Taylor-Francis: London, England, 1991; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, S. The ecological approach to cognitive-motor dual-tasking: findings on the effects of expertise and age. Front Psychol 2014, 5, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, Y.; Okada, H.; Yoshikawa, E.; Nobezawa, S.; Futatsubashi, M. Brain activation during maintenance of standing postures in humans. Brain 1999, 122, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, Y.; Okada, H.; Yoshikawa, E.; Futatsubashi, M.; Nobezawa, S. Absolute changes in regional cerebral blood flow in association with upright posture in humans: an orthostatic PET study. J Nuclear Med 2001, 42, 707–712. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, F.B. Postural orientation and equilibrium: what do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing 2001, 35, ii7–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R.J.; Loughlin, P.J. Dynamic regulation of sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J Neurophysiol 2004, 91, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.D.M. Understanding balance: the mechanics of posture and locomotion; Chapman & Hall: London, England, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lacour, M.; Bernard-Demanze, L.; Dumitrescu, M. Posture control, aging, and attention resources: models and posture-analysis methods. Neurophysiol Clin 2008, 38, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuillerme, N.; Nafati, G. How attentional focus on body sway affects postural control during quiet standing. Psychol Res 2007, 71, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, M.S.; Jennings, J.R.; Martin, C.; Furman, J.M. Attention influences sensory integration for postural control in older adults. Gait Posture 2001, 14, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M. Attentional demands and postural control: the effect of sensory context. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000, 55, M10–M16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihu, A.T.; Hill, K.D.; Jaberzadeh, S. Effect of cognitive task complexity on dual task postural stability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Brain Res 2022, 240, 703–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I.; Effenberg, A.O. Effects of dual tasks and dual-task training on postural stability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging 2017, 12, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, J.; Bray, A.; Sahni, V.; Golding, J.F.; Gresty, M.A. Increasing cognitive load with increasing balance challenge: recipe for catastrophe. Exp Brain Res 2006, 174, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dault, M.C.; Yardley, L.; Frank, J.S. Does articulation contribute to modifications of postural control during dual-task paradigms? Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 2003, 16, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.; Condon, S.M.; McDonald, L.A. Cognitive spatial processing and the regulation of posture. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1985, 11, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujdeci, B.; Turkyilmaz, D.; Yagcioglu, S.; Aksoy, S. The effects of concurrent cognitive tasks on postural sway in healthy subjects. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2016, 82, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M.; Kerns, K.A.; Baldwin, M. The Effects of Two Types of Cognitive Tasks on Postural Stability in Older Adults With and Without a History of Falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1997, 52A, M232–M240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersmann, F.; Bohm, S.; Bierbaum, S.; Dietrich, R.; Arampatzis, A. Young and old adults prioritize dynamic stability control following gait perturbations when performing a concurrent cognitive task. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, G.H.; Neptune, R.R. Task-prioritization and balance recovery strategies used by young healthy adults during dual-task walking. Gait Posture 2022, 95, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffieux, J.; Keller, M.; Lauber, B.; Taube, W. Changes in Standing and Walking Performance Under Dual-Task Conditions Across the Lifespan. Sports Med 2015, 45, 1739–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogev-Seligmann, G.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Giladi, N. Do we always prioritize balance when walking? Towards an integrated model of task prioritization. Mov Disord 2012, 27, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, S.M.; Koop, M.M.; Ozinga, S.; Goldfarb, Z.; Alberts, J.L. A Mobile Device Dual-Task Paradigm for the Assessment of mTBI. Mil Med 2019, 184, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, K.C.; Woollacott, M.H. Attentional demands of postural control: the ability to selectively allocate information-processing resources. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlon, C.; Lehenaff, L.; Batifoulier, C.; Bordier, A.; Chatenet, A.; Desailly, E.; Fouchard, C.; Marsal, M.; Martinez, M.; Rastelli, F.; Thierry, A.; Bartolomeo, P.; Duret, C. Dual-tasking postural control in patients with right brain damage. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, E.; Dawes, H.; Smith, L.; Dennis, A.; Howells, K.; Cockburn, J. Cognitive motor interference while walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.A.; Baker, A.A.; Schmit, J.M.; Weaver, E. Effects of visual and auditory short-term memory tasks on the spatiotemporal dynamics and variability of postural sway. J Mot Behav 2005, 37, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papathanasiou, G.; Georgoudis, G.; Papandreou, M.; Spyropoulos, P.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Kalfakakou, V.; Evangelou, A. Reliability measures of the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in Greek young adults. Hellenic J Cardiol 2009, 50, 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, T.E.; Myklebust, J.B.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Lovett, E.G.; Myklebust, B.M. Measures of postural steadiness: Differences between healthy young and elderly adults. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1996, 43, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D. Multiple resources and performance prediction. Theoretical Issues Ergonom Sci 2002, 3, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisgontier, M.P.; Beets, I.A.; Duysens, J.; Nieuwboer, A.; Krampe, R.T.; Swinnen, S.P. Age-related differences in attentional cost associated with postural dual tasks: increased recruitment of generic cognitive resources in older adults. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013, 37, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustillo-Casero, P.; Villarrasa-Sapiña, I.; García-Massó, X. Effects of dual task difficulty in motor and cognitive performance: Differences between adults and adolescents. Hum Mov Sci 2017, 55, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, F.; Troosters, T.; Spruit, M.A.; Probst, V.S.; Decramer, M.; Gosselink, R. Characteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, K.L.; Martino, G.; Beck, O.N.; Sawicki, G.S.; Ting, L.H. Center of mass states render multijoint torques throughout standing balance recovery. J Neurophysiol 2025, 133, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, A.; Wollesen, B.; Asamoah, J.; Delbaere, K.; Li, K. The impact of cognitive-motor interference on balance and gait in hearing-impaired older adults: a systematic review. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2024, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).