1. Introduction

The Coromandel Coast represents the southeastern coastal area of the Indian subcontinent, functioning as a vital corridor for maritime activities (Mishra et al., 2022). These activities encompass naval operations, environmental protection, maritime surveillance, fishing, and more (Fera & Spandonidis, 2024) (Jayasinghe et al., 2024). To ensure both safety and sustainability, there is a pressing need for an advanced maritime communication and monitoring system (Majidi Nezhad et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the intricate underwater environment presents significant challenges for monitoring maritime conditions (Vasilijevic et al., 2024). To assess the risks present beneath the surface, Digital Twins—a virtual representation—facilitate an information exchange process that supports effective decision-making (Golovan et al., 2024) (Madusanka et al., 2023). By merging the underwater sensor network with Digital Twins (Dai et al., 2022), real-time environmental changes can be accurately detected (Werbińska-Wojciechowska et al., 2024), and timely risk alerts can be issued, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas such as the Coromandel Coast.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) significantly enhances the functionality of Digital Twins (Mohsan et al., 2022). Deep Learning models effectively identify and analyze patterns within sensor data (Ahuja et al., 2023). Furthermore, AI facilitates improved maritime communication by transmitting acoustic signals to the Maritime Alert Command Centre (MACC) (Barbie et al., 2021).

The popularity of artificial intelligence and digital twins has surged in recent years, leading to their application across a variety of domains for numerous scenarios.

Epiphaniou et al. (2023) assessed the enhancement of cyber resilience in Internet of Things (IoT) applications through the implementation of Digital Twins within underwater ecosystems. The underwater parameters were optimized using a Genetic Algorithm (GA). Subsequently, anomalies in the sensor data were predicted by employing a Support Vector Machine (SVM). This approach resulted in improved cyber security resilience for underwater coastal monitoring; however, the subpar quality of the data resulted in an ineffective resilience strategy.

Bi et al. (2024) focused on the development of Digital Twins for the purpose of monitoring intricate coastal terrains. In this study, IoT sensor data collected from underwater environments were integrated into the Digital Twin framework. The monitoring and early warning systems were established by transmitting this data to a neural network algorithm. This facilitated timely interventions based on the alerts generated. Nonetheless, the integration of multiple sensors introduced complexities to the model.

Zhou et al. (2024) implemented a tsunami monitoring system in coastal areas utilizing Digital Twins. This system was designed to detect variations in the underwater marine ecosystem. The Wavelet Transform technique was employed to identify waveforms specific to tsunamis. Anomalies in the sensor data were subsequently detected using a threshold-based method. This buoy-based system enabled a quicker response; however, the prevalence of false positives increased due to background marine noise, leading to inaccurate alerts.

Wang et al. (2024) introduced a model for safety management and decision support in port operations and logistics, utilizing a digital twin framework. This model integrates a hybrid approach combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) networks to facilitate decision-making within the digital twin paradigm. The framework enhances safety measures, thereby decreasing the probability of accidents. Nonetheless, it faced limitations in managing large datasets.

Zhou et al. (2024 a) proposed a digital twin-based smart maritime logistics maintenance system aligned with Industry 5.0. The initial phase involved the deployment of sensors to collect real-time data. Subsequently, features were extracted from this data and input into neural networks. The deep learning models generated optimal decisions aimed at enhancing the reliability of the digital twin systems. However, this approach exhibited significant computational complexity.

Charpentier et al. (2024) focused on creating a safer and more efficient maritime industry through the implementation of 5G and advanced edge computing systems. Their research utilized edge network softwarization and intelligence to develop applications that improve the safety and efficiency of maritime operations. This model streamlined the creation of intricate 5G and beyond vertical services and encouraged collaboration among industry stakeholders, network specialists, and EdgeApp developers. However, deploying this model in challenging maritime environments, characterized by saltwater and high humidity, proved to be difficult.

Adityawan et al. (2023) investigated a tsunami early warning system along the coast that utilizes maritime wireless communication. This system integrated communication between vessels at sea and coastal radio stations. The ships involved in this framework were outfitted with Very High Frequency (VHF) radio communication technology. The model was effective in transmitting warning messages promptly and did not necessitate ongoing maintenance or monitoring. However, the study identified a restricted communication range, especially in isolated or challenging coastal areas, which resulted in connectivity challenges.

Current research on environmental monitoring in maritime settings has largely neglected data security, impacting coastal area monitoring efficacy. To enhance cybersecurity, data encryption from sensors is vital. Furthermore, existing studies inadequately address the dynamic environmental conditions necessary for risk prediction in coastal systems. Noteworthy shortcomings include the lack of inquiry into coastal ecosystem monitoring in light of variable conditions influenced by Digital Twins, vulnerability of underwater sensor networks to cyber threats, insufficient analysis of unusual data spikes and unauthorized requests that impede monitoring, bandwidth limitations in underwater communication affecting data processing, and excessive energy use by traditional communication protocols.

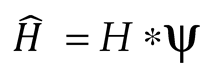

Consequently, a framework is proposed to enhance the Underwater Digital Twins Sensor Network (UDTSN), thereby supporting the sustainable management and protection of coastal ecosystems. The proposed framework offers several significant contributions.

- -

It facilitates the monitoring of the Coromandel Coast through a Digital Twins-based decision-making process that employs the AI-driven EHC-ANFIS technique.

- -

It safeguards the underwater sensor data within the maritime ecosystem by implementing the TKCC method.

- -

It enables the analysis of anomalous patterns during data transmission through the Anomaly Detection System (ADS) model, utilizing the CosLU-VS-LSTM deep learning classifier.

- -

To ensure efficient data transmission within a static bandwidth, data compression using the SHC model.

- -

Lastly, it identifies the optimal path for data transmission to enhance communication efficiency by employing the AP-ACO technique.

The remaining paper is arranged as: section 2 analyzes the existing works, section 3 explains the proposed coastal monitoring system, section 4 describes the performance of proposed model, and section 5 concludes the research paper with future recommendation.

2. Materials and Methods: Maritime Communication and Monitoring Methodology

In this paper, the security of underwater sensor data is addressed, and maritime communication and monitoring are conducted in relation to the dynamic environmental conditions of the Coromandel Coast. The block diagram representing the proposed work is depicted in

Figure 1.

2.1. UAV Initialization and Registration

The maritime communication and monitoring of the Coromandel Coast start with the initialization of the AUV (

B), and is given by:

where, (

s) is the number of AUV. Next, AUVs are registered into the UDTSN with the AUV identity number, and initial Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates. After registration, by utilizing the Digital Twins, the replica of the AUV is created, which helps in navigation of AUV underwater without collision.

2.2. Data Sensing

The underwater sensor data (

H), which includes parameters such as tide level, current speed, wind speed, water temperature, and salinity—collectively referred to as Internet of Things (IoT) data—are acquired by the Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) (

B). This is represented as follows:

where, (

j) is the number of data that are sensed using the AUV.

2.3. Optimal Path Selection for Communication

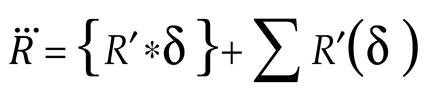

To enhance the communication of the Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) via the Underwater Delay Tolerant Sensor Network (UDTSN) to the Maritime Alert Command Centre (MACC), the optimal transmission path for (H) is determined using Adaptive Pheromone Ant Colony Optimization (AP-ACO). This method leverages Ant Colony Optimization, which is adept at adjusting to dynamic environments for real-time pathfinding. However, it is noted that ACO exhibits slow convergence in extensive spaces. Consequently, an Adaptive Pheromone (AP) distribution function is employed during the exploration phase. The AP-ACO process is elaborated as follows.

The initial position (

R) of the communication paths (ant) in UDSTN is initialized as:

where, (

ubR !

lbR) are the upper bound and lower bound values of (

R), and (α) is the random number. Next, the fitness function (ℑ) that determines the best path is evaluated regarding the minimum response time (

I ) as:

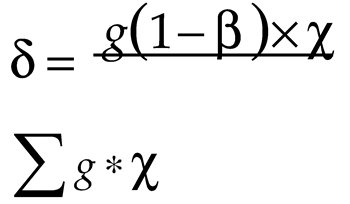

Now, the position of the ants regarding the search of food using the exploration and exploitation is updated. During the exploration phase, the ants release pheromones, which influence the selection of their paths. In this context, the parameter AP (δ), which determines a more effective starting point and enhances convergence, is defined as follows:

where, (

g) is the pheromone level, (β) is the pheromone evaporation rate, and (χ) is the heuristic value. Now, the new position (

R′) of ants regarding (δ) is updated as:

Next, during the local update (exploitation phase), the ants encourage other ants to choose (δ), thus the updated position (

), is equated by:

Finally, the optimal path for the efficient transmission of maritime sensor data via the UDTSN has been determined based on the fitness (ℑ). The path selected is denoted as (Rbest ).

2.4. Sensor Data Shrinkage

In this stage, the transmission of sensor data (H) with a fixed bandwidth is optimized through the application of shrinkage techniques utilizing SHC. In this context, Huffman Coding (HC) is employed to compress the data, allowing for its reconstruction into the original format without any loss of information.

On the contrary, the frequent alteration of input could not be updated in the Huffman tree, as the codes are fixed in the tree. Consequently, the Sliding Window technique is employed in Huffman Coding to incorporate the data into the tree.

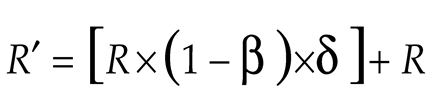

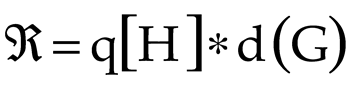

To create Huffman tree (ℜ) based on new sensor data, the Sliding window (

q), which discards the old data and includes the new data as segments, is included into (ℜ). It is expressed as:

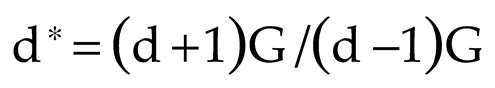

where, (

d) is the frequency of the symbols (

G) . Here, for frequent symbols, shorter codes are assigned and longer codes are allotted to less-frequent symbols. The frequency (

d) is updated for each symbol, which helps in compression of the data. The updated frequency (

d ∗) is equated by:

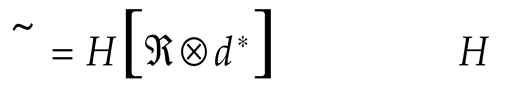

The Huffman tree is rebalanced based on (

d ∗ )to give the compressed sensor data (

) as Follows:

Thus, the compressed sensor data is transmitted effectively through the selected path (Rbest ) of the Underwater Digital Twins Sensor Network.

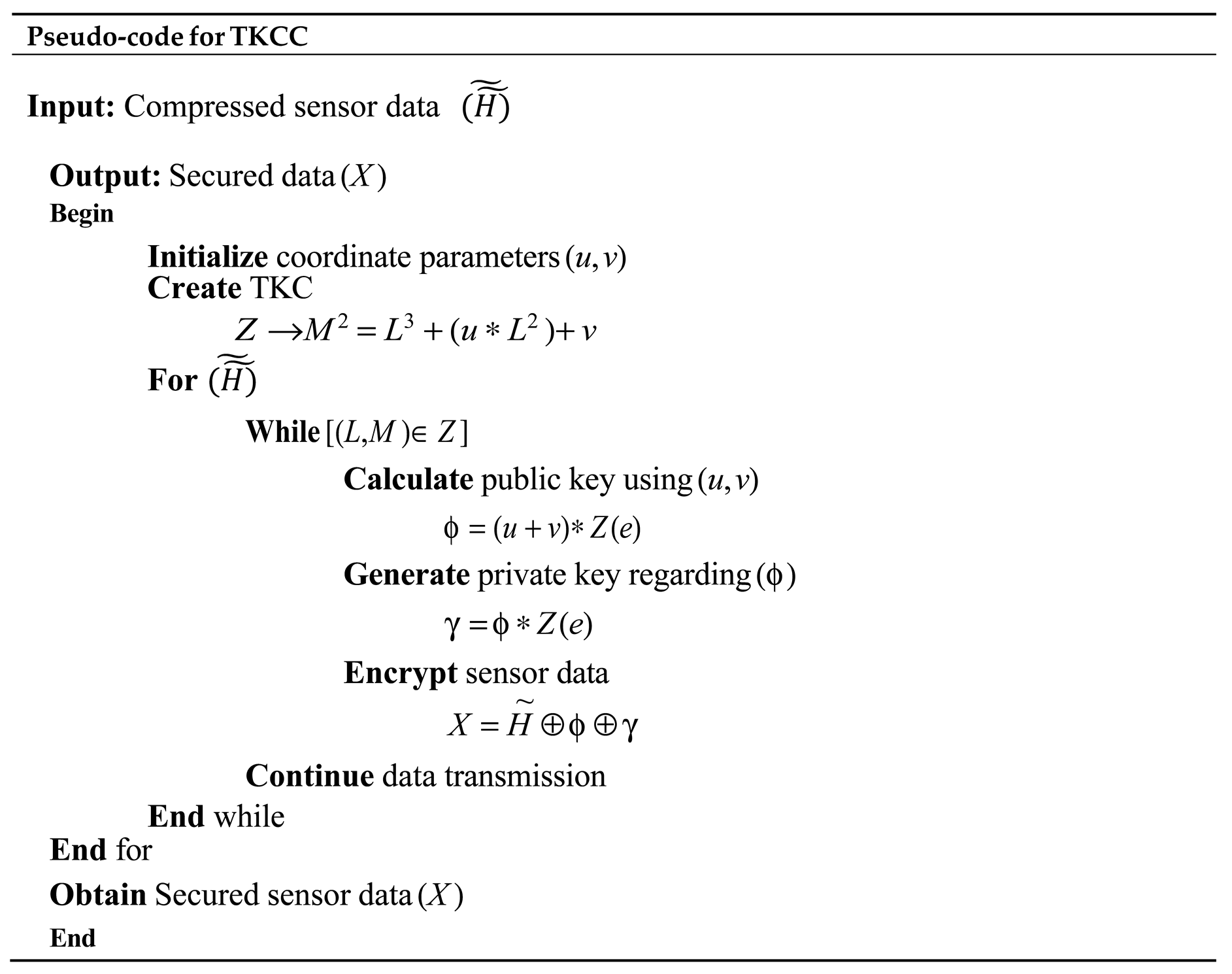

2.5. Data Security

Here, to ensure that the data received in the MACC matches the data that is transmitted, the compressed data is protected using TKCC.

The method employed for securing the data is Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), which offers a high level of security with a reduced key size. Nevertheless, the drawbacks associated with the Elliptic Curve lead to increased computational complexity. To address this challenge, the Twisted Koblitz Curve (TKC) is utilized as an alternative to the Elliptic Curve in ECC. The data security process is illustrated below.

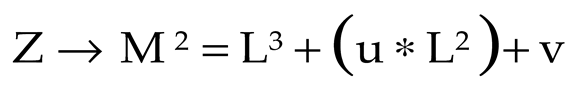

The TKC (

Z), responsible for managing the coordinates within the finite field and providing a non-zero variable, is expressed as follows:

where, (

L,

M)are the horizontal and vertical axes of (

Z), and (

u,

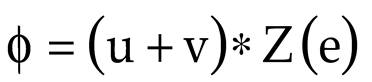

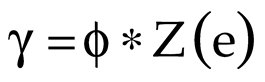

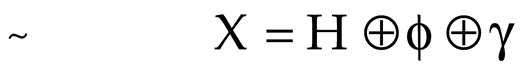

v) are the coordinate values. Now, the public key (ϕ) and the private key (γ) of the TKCC are calculated for securing the input data:

where (

e) is the randomly generated coordinate of the TKC. Finally,

is secured using (ϕ), and (γ) to make sure that the data security persists during data transmission in the complex acoustic environment of the Coromandel Coast. The secured data (

X) is equated as:

The pseudo-code of TKCC is explained below.

Thus, the sensitive sensor data is encrypted and it is sent for further processing.

2.6. Anomaly Detection System Model

In this stage, the Anomaly Detection System (ADS) model is trained to safeguard the integrity of sensitive maritime data while it is transmitted via the Underwater Digital Twins Sensor Network. The details of the ADS model training are outlined below.

2.6.1. Dataset

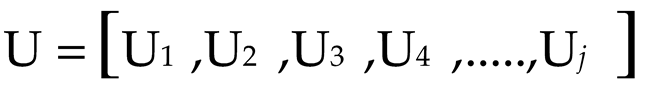

Initially, to train the ADS model regarding the anomaly detection during sensor data transmission, the NSL-KDD dataset is collected. The data (

U ) present in the NSL-KDD dataset is given by:

where, (

ƒ) represents the number of (

U )

2.6.2. Pre-Processing

Next, to structure the data for effective anomaly detection, the pre-processing steps, such as Missing Value Imputation (MVI), numeralization, and normalization are implemented.

- ✓

Missing Value Imputation

Here, the missing values in (

U )is added based on the median of the neighbouring data. The imputation of the values is evaluated as:

where, (

U ′′′) represents the imputed data for the missing value of (

ƒ ).

Following MVI, the string data in (

U ′′′) is transformed in numerical values, facilitating the processing of the Artificial Intelligence (AI). The numeralization of (

U ′′′) is given below.

where

is the numeralized data, and (

k) is the binary vector.

Finally,

is normalized using the min-max technique. Here, the data is scaled to fall in the range of (0

to1). Consequently, all data points that exist on varying scales undergo scalar transformation. The normalization process is represented as follows:

where, (

) is the normalized data, which is the final pre-processed output, and

are the minimum and maximum values of

.

2.6.3. Feature Extraction

Here, from (

), various features are extracted, including duration, protocol_type, service, flag, src_bytes, dst_bytes, wrong_fragment, urgent, dst_host_srv_count, count, num_compromised, num_access_files, serror_rate, dst_host_count, dst_host_srv_rerror_rate, and are represented as follows:

where, (

T ) is the feature extracted, and (

y)is the number of (

T ).

2.6.4. Intuitive Visualization

To analyze the differences and similarities in (

T), the Radial Chart is employed, as it effectively captures patterns in the input, particularly when examining the features over time. It is expressed as,

where, (

F )is the intuitive visualization of (

T ), (λ )is the axes of the Radial Chart, and (

c) is the circular format of the chart.

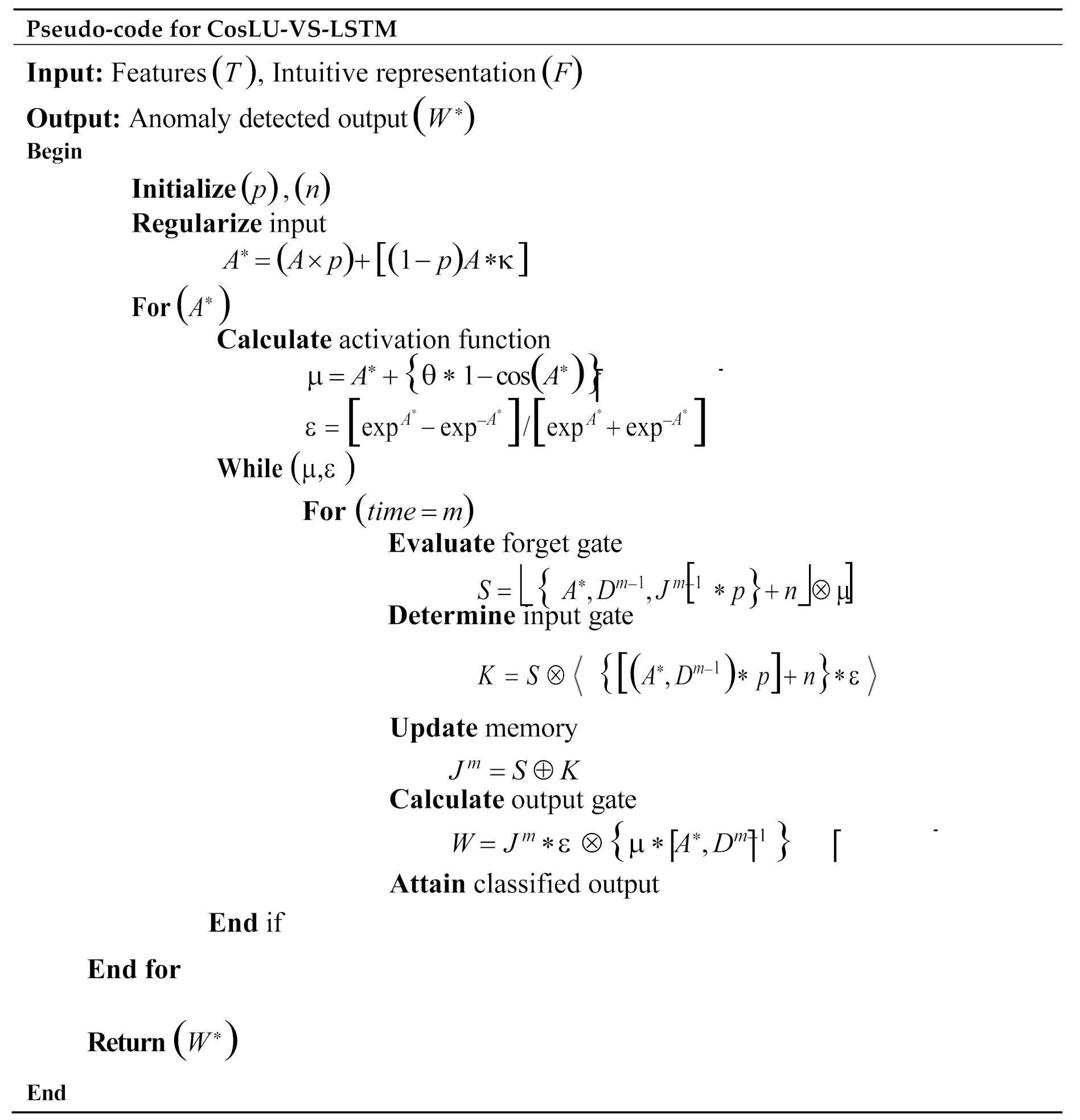

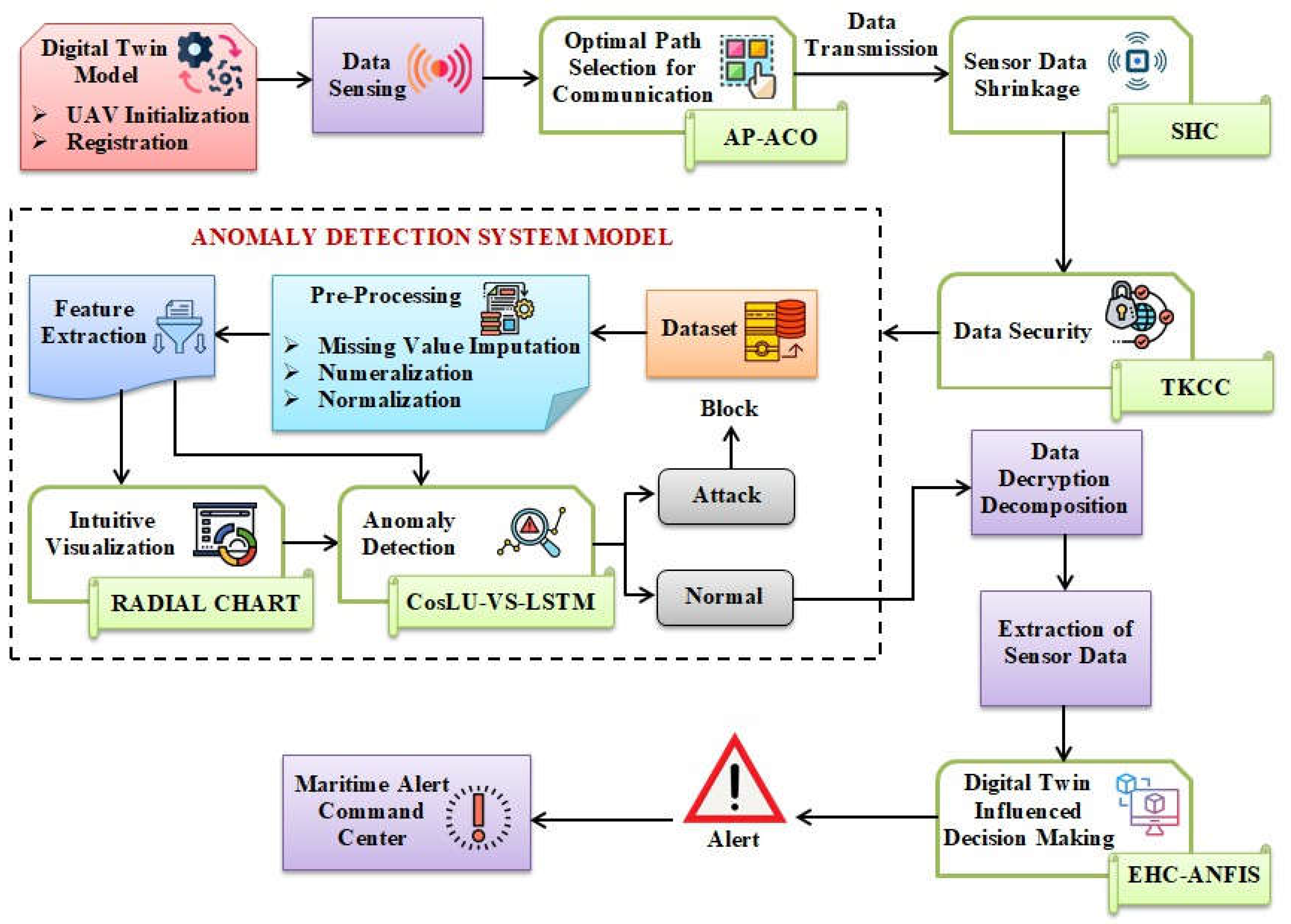

2.6.5. Anomaly Detection

In this stage, the identification of anomalies within the data packets is conducted through the application of the CosLU-VS-LSTM Artificial Intelligence methodology. This approach employs Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which address the vanishing gradient issue and facilitate more efficient training on extensive sequences of IoT sensor data for the purpose of anomaly detection. However, LSTM networks are susceptible to overfitting, and the utilization of the sigmoid activation function can hinder the classification speed. To mitigate the overfitting concern, Variational Shake-drop (VS) regularization is implemented, while the Cosinu-sigmoidal Linear Unit (CosLU) function is adopted in place of the sigmoid activation function to enhance the speed of the anomaly detection process. The architecture of the proposed classifier is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The method of CosLU-VS-LSTM, which incorporates elements such as forget date, input gate, output gate, cell state, and memory, is detailed in the folowing sections.

↱ Regularization

The input of the proposed classifier denoted as (T), and (F) are represented together as (A).

To address the issue of overfitting, the VS regularization technique is employed, which facilitates the learning of a robust representation within the data and appropriately scales the data. This technique is indicated by:

where, (

A∗)is the regularized data, (

p) is the weight value, and (κ)is the skip connection factor.

↱ Activation Function

Next, the CosLU function (μ), which combines linear and cosine components to capture complex patterns, and the hyperbolic tangent (tanh) activation function (ε ) that maps the patterns effectively are calculated as follows:

where, (θ) is the scaling hyperparameter, and (exp) is the exponential factor.

↱ Forget Gate

Here, the data that are not necessary for detecting anomaly are removed. The previous hidden layer (

Dm−1) with time (

m), previous memory (

J m−1), and the input (

A∗) is added and activated using (μ). This is expressed as follows:

where, (

S) is the output of the forget gate, and (

n) the bias value.

↱ Input Gate

Here, the information is added to the present memory (

J m). Here, the inputs are activated using (μ) and (ε) simultaneously as follows:

where, (

K )is the output of the input gate.

↱ Memory

The output of the forget gate (

S ) and the input gate (

K) are added to update the present memory (

J m )as:

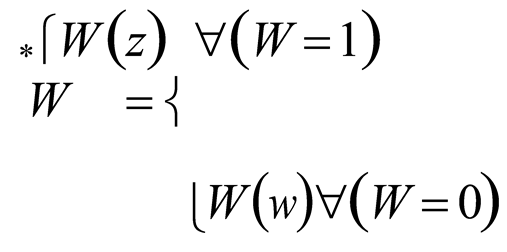

↱ Output gate

Finally, depending on (

J m ), and (

A∗ ), the output gate value (

W ), which extracts the most important information and helps in identifying the anomaly is calculated as:

where, (

W ∗) is the overall anomaly detected output,

W (

z) shows the presence of anomaly when (

W = 1), and

W (

z) is the normal class when (

W = 0). The pseudo-code for CosLU

-VS- LSTM is explained below.

Upon completion of the ADS model training, any detected anomalies during the real-time transmission of data. (X) will result in the blocking of that transmission, while data transmission for the normal class will proceed uninterrupted within the UDTSN.

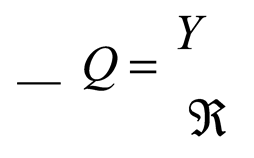

2.7. Data Decryption and Decomposition

For

W (

z), the data (

X ) is transmitted along the Underwater Digital Twins Sensor Network. To further process the data for the monitoring purpose of the Coromandel Coast, the decryption is done using the keys (ϕ), and (γ) generated by TKCC method as explained in the following sections.

where, (

Y ) is the decrypted data. Next, (

Y ) is decomposed using (ℜ) to obtain the exact file, and is given by:

where, (

Q) is the decomposed data.

2.8. Extraction of Sensor Data

Here, the original sensor data (H) passing through the UDTSN is extracted from (Q). This data is further used for monitoring the Coromandel Coast regarding varying complex environmental changes and conditions.

2.9. Digital Twins Influenced Decision-Making

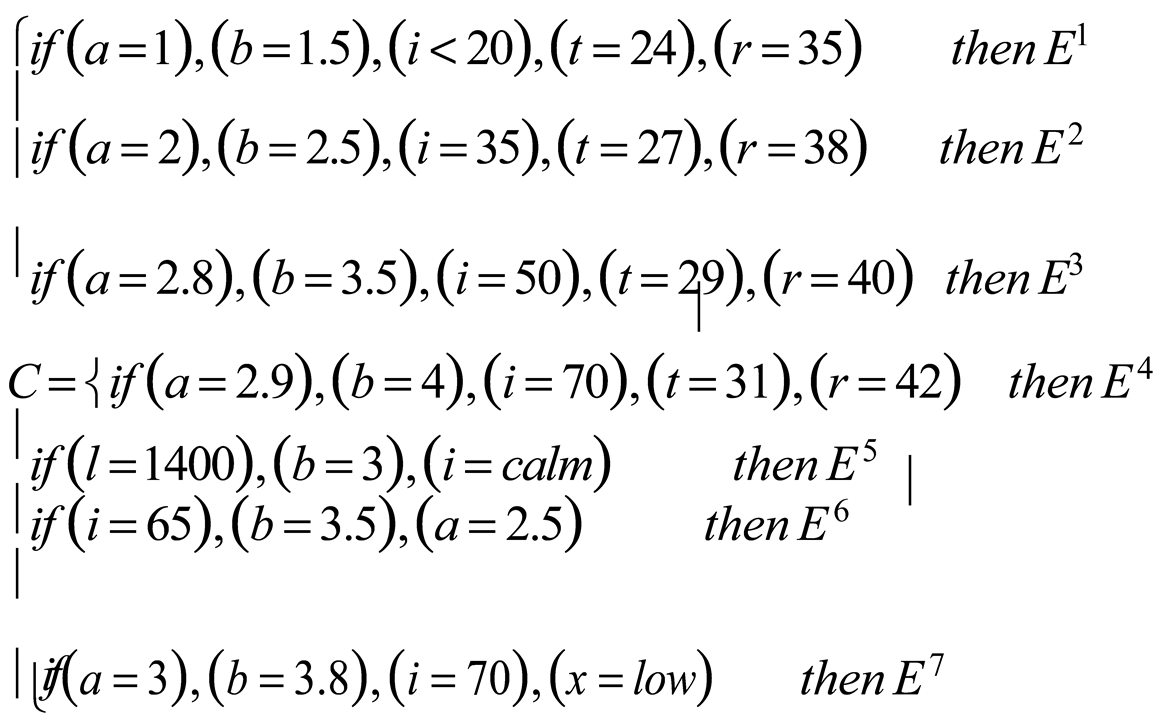

The final decision-making process concerning the monitoring level of the Coromandel Coast is conducted through the EHC-ANFIS (AI-IoT) hybrid approach. The data (H), collected via the Underwater Digital Twins Sensor Network, serves as the input for the EHC-ANFIS system. This system employs the Adaptive Network-based Fuzzy Inference System, which evaluates the IoT sensor data obtained from Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and modifies parameters in response to updated climatic information, thereby facilitating decisions related to the monitoring of the Coromandel Coast. It is important to note that the ANFIS framework necessitates specialized knowledge and expertise to accurately define fuzzy sets, membership functions, and rule bases. To improve the decision-making process, the Exponential Hyperbolic Crisp (EHC) membership function is implemented. The subsequent steps involved in the decision-making process are outlined below.

Initially, the fuzzy rule (

C) based on if-then condition is set for making adequate decisions to monitor the coastal ecosystem. It is equated as:

where, the tide level (

a) is recorded in meter, the current speed (

b) is expressed in meter per second, the wind speed (

i) is indicated in kilometer per hour, the water temperature (

t) is measured in degree Celsius, salinity (

r) is quantified using Practical Salinity Unit (PSU). Additionally, (

l) denotes the sound velocity, which influences the acoustic sensor performance, while (

x) represents the sensor battery level. In this context, the decision-making (

E) related to the monitoring of the coast is categorized as follows: (

E1) signifies a green alert indicating low risk, (

E 2 )denotes a yellow alert representing moderate risk, (

E3) indicates a red alert for high risk, (

E 4) refers to a red alert for critical hazards , (

E5) is a special alert for disruption in acoustic propagation, (

E 6) represents the yellow alert with pre-emptive early warning for incoming storms, and (

E 7) is a multi-factor red alert that combines risks from environmental factors and system failures.

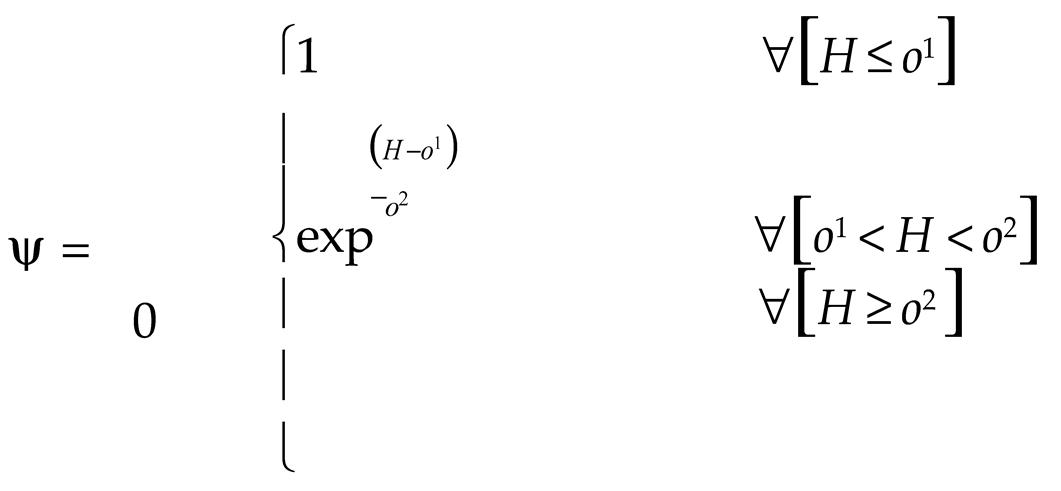

Now, the EHC membership function (ψ ) that identifies the parameters effectively, is used. It is equated as,

where, (

o1,

o2 )are the scaling parameters of the input (

H).

Here, the input (H) is converted into fuzzy data () so that the AI method can learn the input data precisely. It is given by:

The input is multiplied by the membership function to assess the extent of the relationship between the data.

The fuzzy data (

) is derived using the rule (

C) and subsequently defuzzified to obtain the final output as shown below.

Thus, (E) represents the decision-making in monitoring the Coromandel Coast.

2.10. Alert to Maritime Alert Command Centre

According to the obtained (E), an alert is sent to the MACC. Consequently, the maritime communication and surveillance of the Coromandel Coast are enhanced through the implementation of the proposed framework. The effectiveness of the proposed initiative is detailed as follows.

3. Results and Discussions

This section presents the performance evaluation and comparative analysis of the proposed model alongside existing techniques to demonstrate the reliability of the proposed model. Additionally, the implementation of the proposed model is carried out on the PYTHON working platform.

3.1. Dataset Description

The framework presented utilizes the “NSL-KDD” dataset to evaluate the proposed model. This dataset has been sourced from publicly accessible materials, with the corresponding link provided in the reference section. It comprises a total of 125,973 data entries. Of this total, 80%, equating to 100,778 entries, is allocated for training, while the remaining 20%, amounting to 25,195 entries, is designated for testing purposes.

3.2. Performance Assessment

The evaluation of the proposed method alongside existing techniques is conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed model.

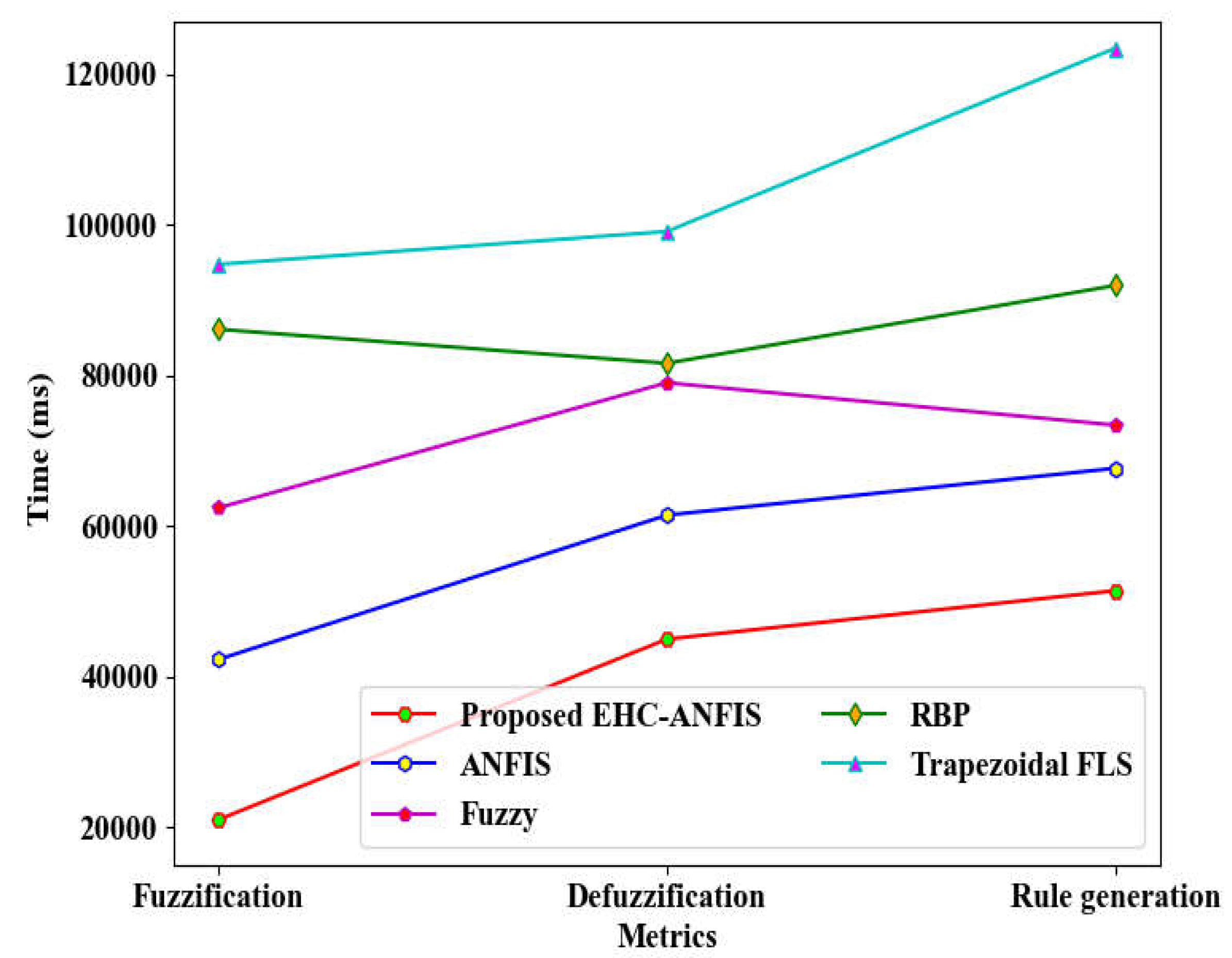

Figure 3 illustrates the graphical comparison between the proposed EHC-ANFIS and existing methodologies in terms of fuzzification, defuzzification, and rule generation times. The EHC-ANFIS model exhibited significantly lower times of 21045 ms for fuzzification, 45012 ms for defuzzification, and 51452 ms for rule generation, attributed to the implementation of the Exponential Hyperbolic Crisp Membership Function. In contrast, the conventional techniques, including ANFIS, Fuzzy, Rule-Based Prediction (RBP), and Trapezoidal Fuzzy Logic System (Trapezoidal FLS), recorded higher average times of 71422.25 ms, 80329.5 ms, and 89144.75 ms for fuzzification, defuzzification, and rule generation, respectively. This clearly highlights the superior performance of the proposed model.

The performance validation of the proposed CosLU-VS-LSTM model, along with existing techniques such as LSTM, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN), is illustrated in

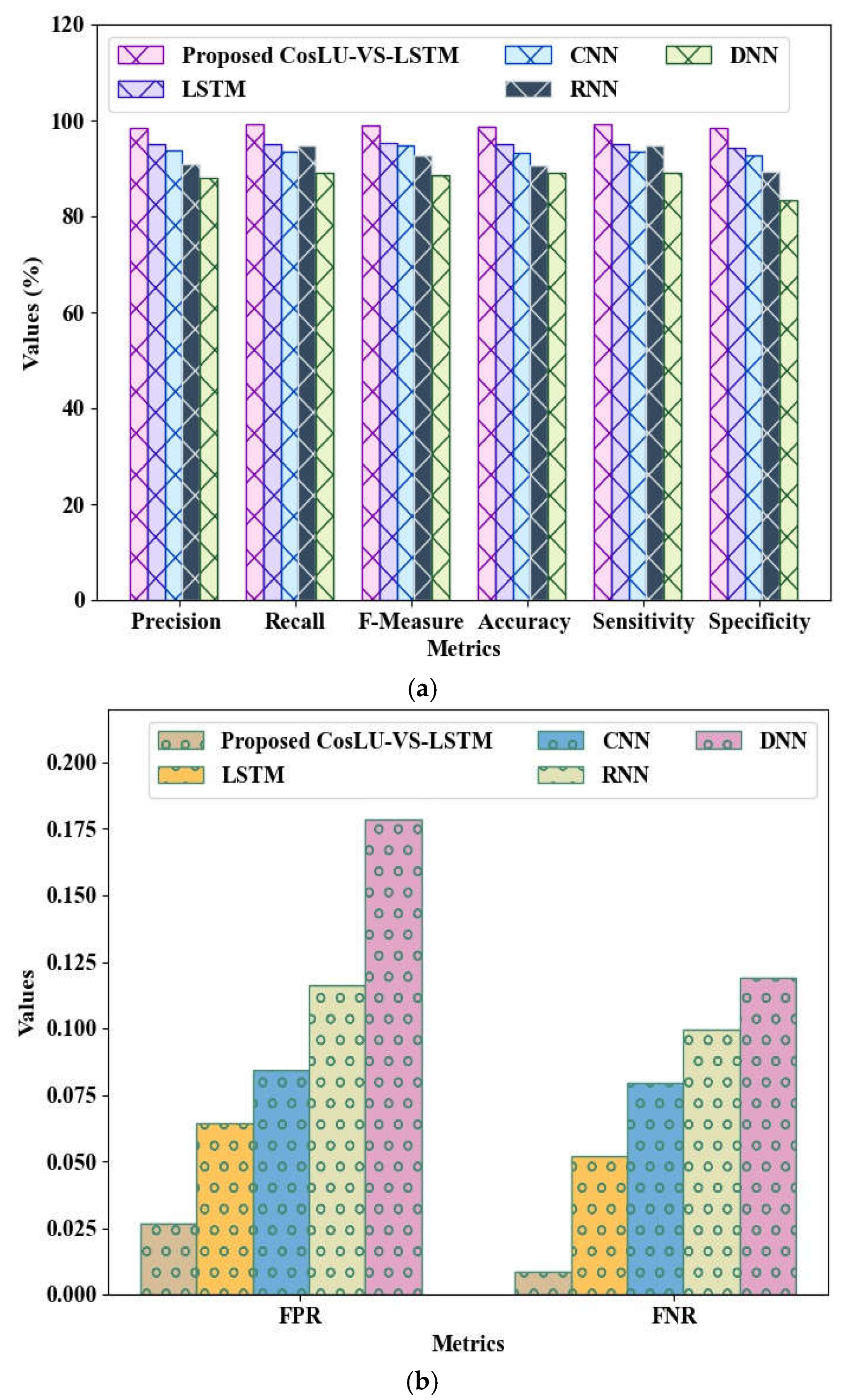

Figure 4a,b. The proposed CosLU-VS-LSTM demonstrated impressive metrics, achieving precision, recall, F-Measure, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity values of 98.35%, 99.15%, 99.00%, 98.62%, 99.15%, and 98.31%, respectively. Additionally, it recorded a low False Positive Rate (FPR) of 0.0268776 and a False Negative Rate (FNR) of 0.008653. In contrast, the existing models—LSTM, CNN, RNN, and DNN—exhibited lower precision rates of 95.13%, 93.75%, 90.87%, and 88.15%, respectively. These established techniques also showed diminished accuracy, recall, F-measure, sensitivity, and specificity. Notably, the existing DNN model had a significantly high FPR of 0.1786746 and an FNR of 0.119243. To address the overfitting problem, the Variational Shake Drop Regularization technique was adapted within the CosLU-VS-LSTM framework. Consequently, the results indicate that the proposed model outperformed the existing methodologies.

Table 1 illustrates the evaluation of the True Positive Rate (TPR) and True Negative Rate (TNR) for the proposed CosLU-VS-LSTM model in comparison to existing methodologies. The CosLU-VS-LSTM model utilizes the Variational Shake Drop Regularization technique along with the CosLU function to effectively identify anomalies. This model achieved impressive TPR and TNR values of 98.72% and 98.31%, respectively. In contrast, traditional techniques such as LSTM, CNN, RNN, and DNN demonstrated lower average TPR and TNR, recorded at 93.11% and 89.93%, respectively. Therefore, the reliability of the proposed model is substantiated.

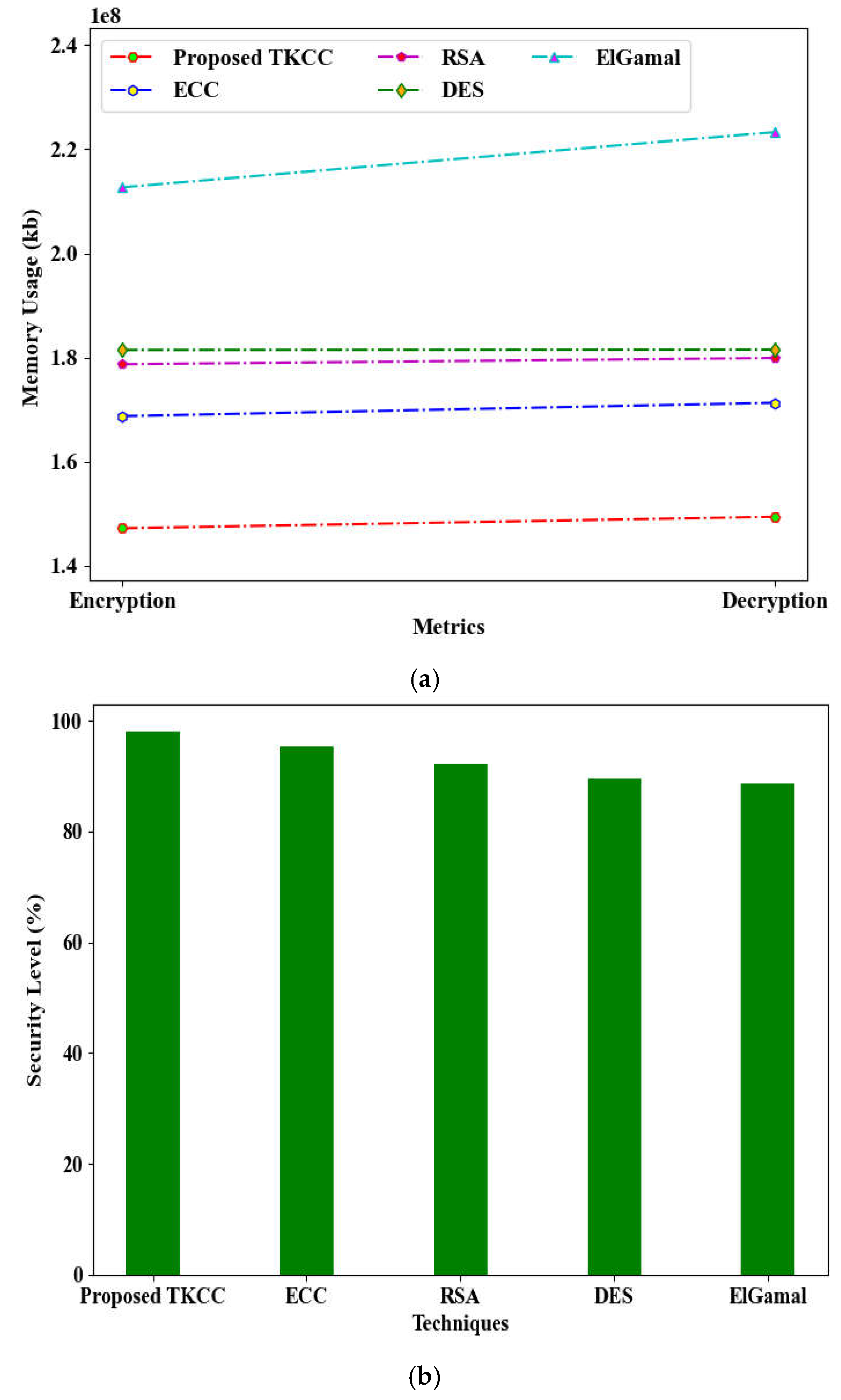

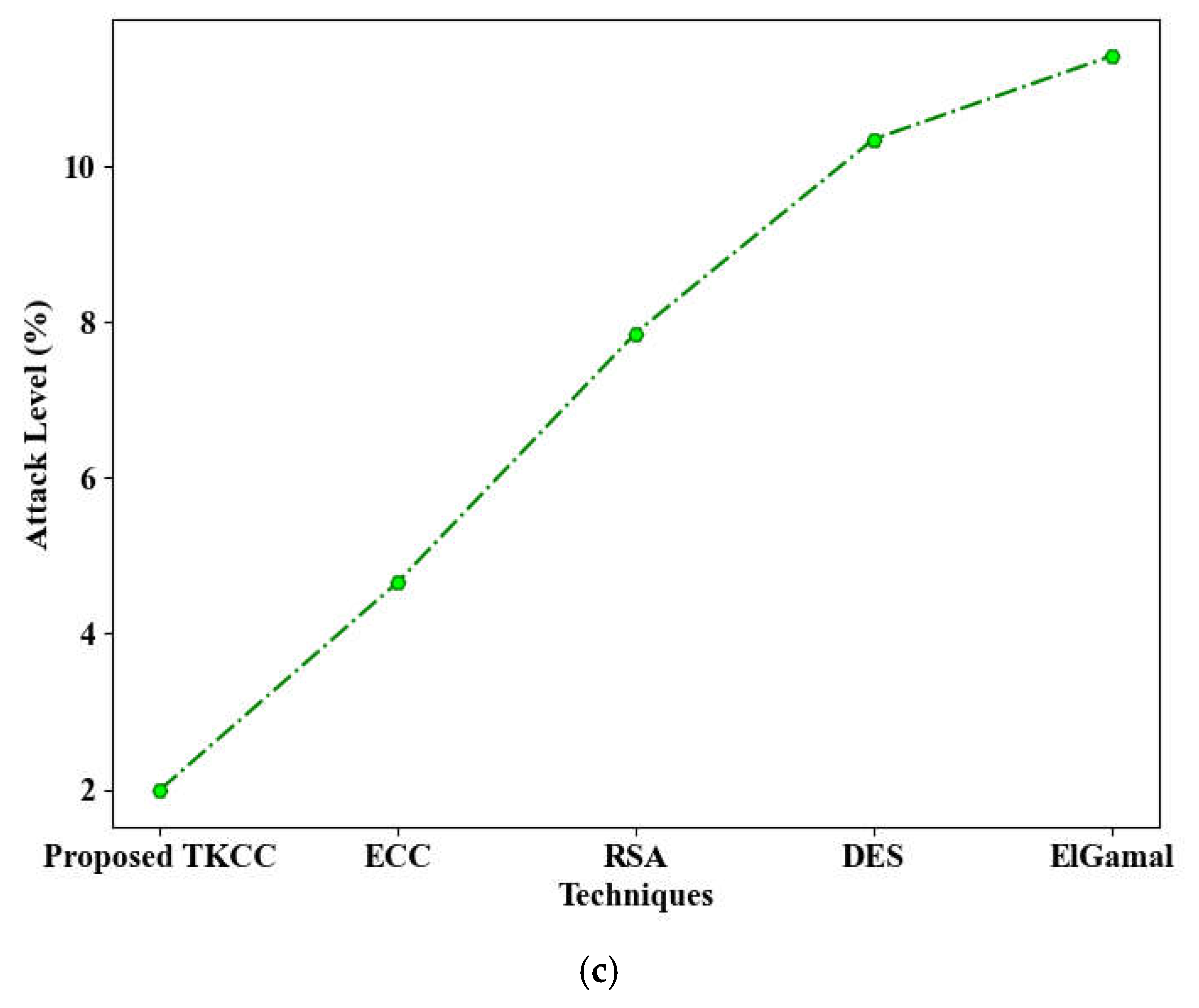

Figure 5 (a), (b), and (c) illustrates the comparative graphical analysis of the proposed model against traditional methods regarding memory consumption during encryption and decryption processes, as well as their respective security and attack levels. The proposed Twisted Koblitz Curve Cryptography (TKCC) utilized 147,245,452 KB of memory for encryption and 149,456,981 KB for decryption. In addition, the TKCC demonstrated a commendable security level of 98.01% and a minimal attack level of 1.99%, outperforming conventional methods. In contrast, traditional techniques such as Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA), Data Encryption Standard (DES), and ElGamal required significantly more memory for both encryption and decryption. Furthermore, these existing methods exhibited inferior security and attack levels. The implementation of the Twisted Koblitz Curve serves to enhance data security.

The analysis of compression times for the proposed SHC and existing techniques is presented in

Table 2. The proposed SHC achieved a notably low compression time of 140758ms, in contrast to the conventional methods: Huffman Coding (HC) at 198563ms, Lempel-Ziv (LZ) at 253564ms, Run-Length Encoding (RLE) at 314748ms, and Arithmetic Coding (AC) at 398756ms. Consequently, the proposed SHC demonstrates superior efficiency in the compression of sensor data.

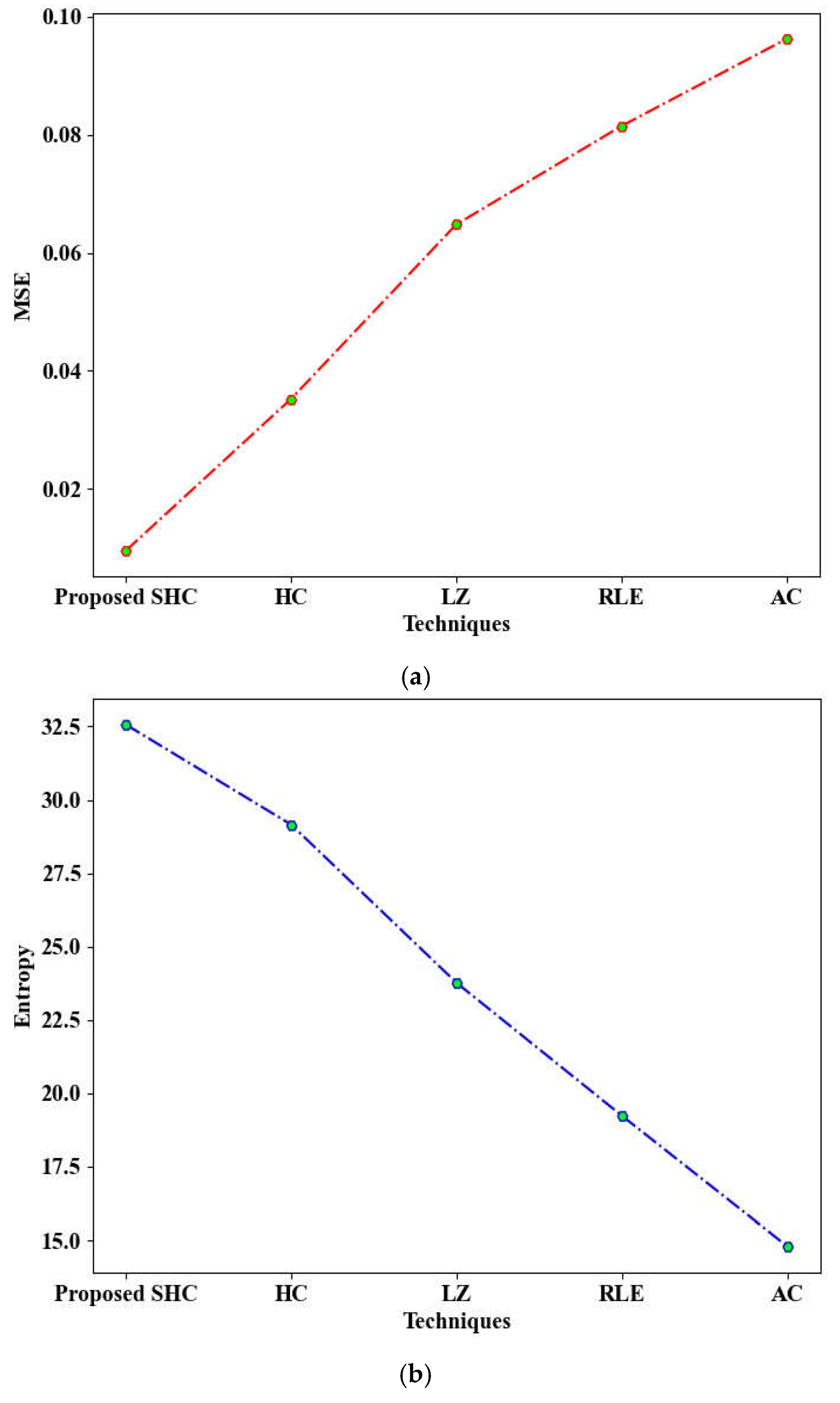

Figure 6 illustrates the comparative evaluation of the proposed SHC against established methods, including HC, LZ, RLE, and AC. In this analysis, the sliding window has been enhanced with SHC to mitigate inefficiencies. The proposed SHC demonstrated a low Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 0.00954 and a high entropy value of 32.56. In contrast, the existing techniques such as HC, LZ, RLE, and AC recorded a higher average MSE of 0.06942 and a lower average entropy of 21.73. Therefore, the proposed model outperforms the current techniques.

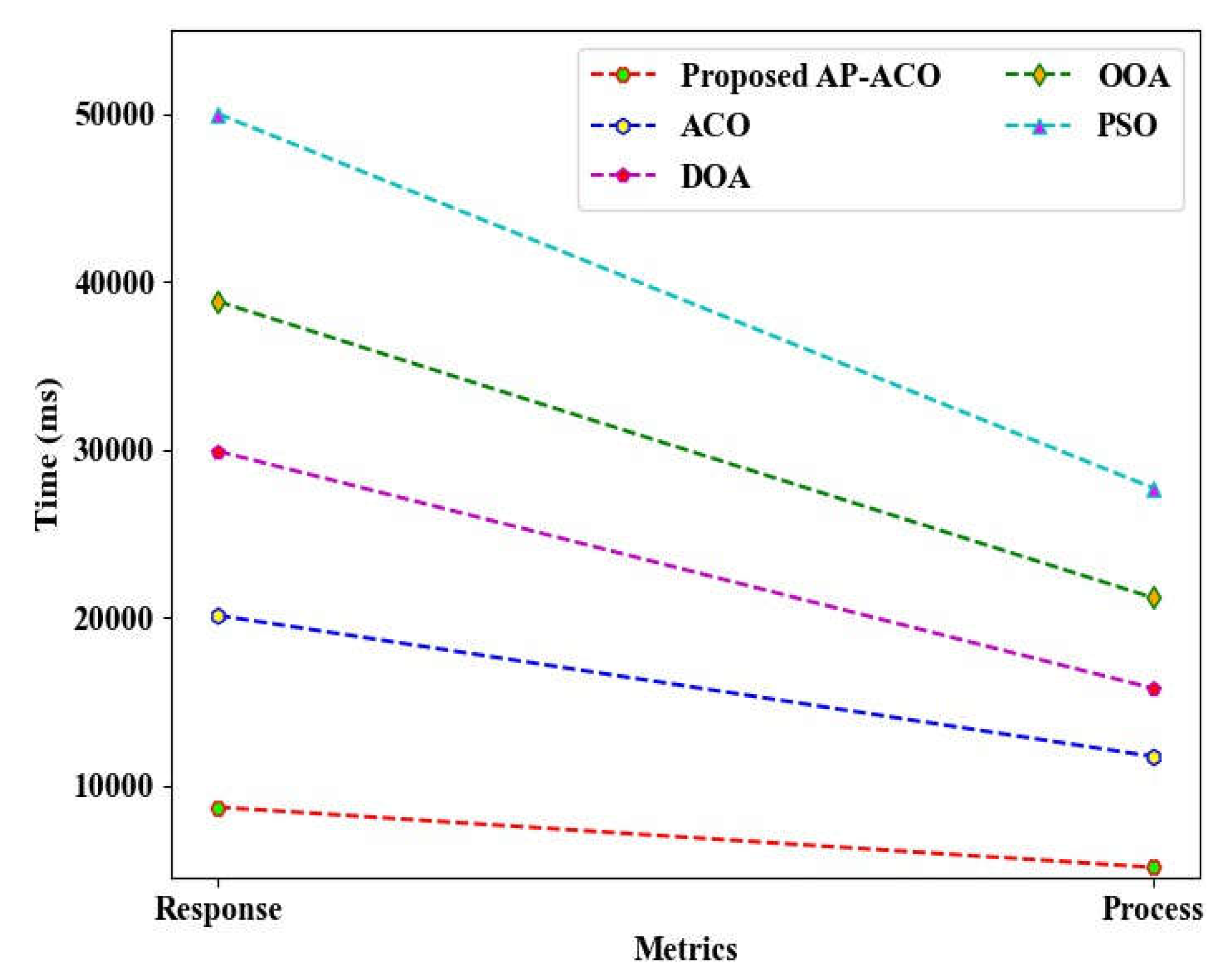

The performance validation of the proposed AP-ACO in comparison to existing techniques concerning response time and process time is illustrated in

Figure 7. The proposed AP-ACO demonstrated a significantly reduced response time of 8701 ms and a process time of 5117 ms, attributed to its ability to identify optimal solutions adaptively. In contrast, the existing algorithms, including ACO, Dingo Optimization Algorithm (DOA), Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), exhibited higher response and process times. Consequently, the findings confirm that the proposed model exhibits lower time complexities.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

The comparative analysis of the proposed model in relation to existing works is conducted here.

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed model against existing studies, highlighting its objectives, benefits, and drawbacks.

The proposed model demonstrated remarkable efficiency in maritime communication and monitoring of the Coromandel Coast, yielding superior results. In contrast, the existing model by Ramírez-Herrera et al. (2022) exhibited a high false alarm rate, while the approach by Pribadi et al. (2021) was burdened with significant initial setup costs. Additionally, the traditional method outlined by Suppasri et al. (2021) proved to be less effective due to its complex system. Furthermore, the models presented by Epiphaniou et al. (2023) and Zhou et al. (2024) achieved only limited performance. Therefore, the proposed framework surpasses the current adopted techniques.

4. Conclusions

This study introduced a robust underwater digital twin sensor network designed for maritime communication and monitoring along the Coromandel Coast, utilizing EHC-ANFIS. The evaluation of the proposed model was conducted using the “NSL-KDD” dataset. The CosLU-VS-LSTM model demonstrated exceptional capability in anomaly detection, achieving impressive accuracy and recall rates of 98.62% and 99.15%, respectively, thereby underscoring the model’s effectiveness. Furthermore, the EHC-ANFIS model excelled in facilitating decision-making influenced by digital twins, achieving a minimal rule generation time of 51452ms, which indicates the model’s low time complexity. In addition, the TKCC model effectively secured data, attaining a high security level of 98.01% and a low attack level of 1.99%, thereby affirming the model’s reliability. The AP-ACO model also successfully identified the optimal communication path, achieving a response time of 8701ms. Consequently, the proposed framework demonstrated efficient maritime communication and monitoring capabilities for the Coromandel Coast. While the current research effectively applied digital twin-based decision-making for disaster management in this region, it did not account for various coastal ecosystems, such as coral reefs, salt marshes, mangrove forests, and kelp forests, which are vital for disaster management. Future work will focus on incorporating these coastal ecosystems to further enhance the framework’s performance.

Dataset Link

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hassan06/nslkdd.

References

- Adityawan, M. B., Nurendyastuti. Development of a tsunami early warning system on the coast of Palu based on maritime wireless communication. Progress in Disaster Science 2023, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, N. J., Kumar, A., Thapliyal, M., Dutt, S., Kumar, T., Aarhus, D. A. D. J. P., Konstantinou, C., & Choo, K.-K. R. (2023). Blockchain for unmanned underwater drones: Research issues, challenges, trends and future directions. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 215, 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2023.103649.

- Ashraf, I., Park, Y., Hur, S., Kim, S. W., Alroobaea, R., Zikria, Y. Bin, & Nosheen, S. (2023). A Survey on Cyber Security Threats in IoT-Enabled Maritime Industry. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 24(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3164678.

- Barbie, A., Pech, N., Hasselbring, W., Flogel, S., Wenzhofer, F., Walter, M., Shchekinova, E., Busse, M., Turk, M., Hofbauer, M., & Sommer, S. (2021). Developing an Underwater Network of Ocean Observation Systems With Digital Twin Prototypes - A Field Report From the Baltic Sea. IEEE Internet Computing, 26(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2021.3065245.

- Bi, J., Wang, P., Zhang, W., Bao, K., & Qin, L. (2024). Research on the Construction of a Digital Twin System for the Long-Term Service Monitoring of Port Terminals. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12071215.

- Charpentier, V., Slamnik-Kriještorac, N., Landi, G., Caenepeel, M., Vasseur, O., & Marquez- Barja, J. M. (2024). Paving the way towards safer and more efficient maritime industry with 5G and Beyond edge computing systems. Computer Networks, 250, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110499.

- Dai, M., Li, Y., Li, P., Wu, Y., Qian, L., Lin, B., & Su, Z. (2022). A Survey on Integrated Sensing, Communication, and Computing Networks for Smart Oceans. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks, 11(4), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan11040070.

- Epiphaniou, G., Hammoudeh, M., Yuan, H., Maple, C., & Ani, U. (2023). Digital twins in cyber effects modelling of IoT/CPS points of low resilience. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory, 125, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2023.102744.

- Fera, F., & Spandonidis, C. (2024). A Fault Diagnosis Approach Utilizing Artificial Intelligence for Maritime Power Systems within an Integrated Digital Twin Framework. Applied Sciences, 14(18), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14188107.

- Golovan, A., Mateichyk, V., Gritsuk, I., Lavrov, A., Smieszek, M., Honcharuk, I., & Volska, O. (2024). Enhancing Information Exchange in Ship Maintenance through Digital Twins and IoT : A Comprehensive Framework. Computers, 13, 2024.

- Jayasinghe, S. C., Mahmoodian, M., Sidiq, A., Nanayakkara, T. M., Alavi, A., Mazaheri, S., Shahrivar, F., Sun, Z., & Setunge, S. (2024). Innovative digital twin with artificial neural networks for real-time monitoring of structural response: A port structure case study. Ocean Engineering, 312, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.119187.

- Kutzke, D. T., Carter, J. B., & Hartman, B. T. (2021). Subsystem selection for digital twin development: A case study on an unmanned underwater vehicle. Ocean Engineering, 223, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.108629.

- Madusanka, N. S., Fan, Y., Yang, S., & Xiang, X. (2023). Digital Twin in the Maritime Domain: A Review and Emerging Trends. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 11(5), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse11051021.

- Majidi Nezhad, M., Neshat, M., Sylaios, G., & Astiaso Garcia, D. (2024). Marine energy digitalization digital twin’s approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 191, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114065.

- Mishra, A., Kumar, R., & Pradesh, U. (2022). Deployment of Biosensors in Aquatic Bio- Optical Communication System & its Applications in Gulf of Mannar. NeuroQuantology, 12(13), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.48047/nq.2022.20.13.NQ88533.

- Mohsan, S. A. H., Mazinani, A., Othman, N. Q. H., & Amjad, H. (2022). Towards the internet of underwater things: a comprehensive survey. Earth Science Informatics, 15(2), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-021-00762-8.

- Pribadi, K. S., Abduh, M., Wirahadikusumah, R. D., Hanifa, N. R., Irsyam, M., Kusumaningrum, P., & Puri, E. (2021). Learning from past earthquake disasters: The need for knowledge management system to enhance infrastructure resilience in Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 64, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102424.

- Ramírez-Herrera, M. T., Coca, O., & Vargas-Espinosa, V. (2022). Tsunami Effects on the Coast of Mexico by the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai Volcano Eruption, Tonga. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 179(4), 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-022-03017-9.

- Suppasri, A., Maly, E., Kitamura, M., Syamsidik, Pescaroli, G., Alexander, D.F., & Imamura, F. (2021). Cascading disasters triggered by tsunami hazards: A perspective for critical infrastructure resilience and disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 66, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102597.

- Vasilijevic, A., Brönner, U., Dunn, M., García-Valle, G., Fabrini, J., Stevenson-Jones, R., Bye, B. L., Mayer, I., Berre, A., Ludvigsen, M., & Nepstad, R. (2024). A Digital Twin of the Trondheim Fjord for Environmental Monitoring—A Pilot Case. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(9), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12091530.

- Wang, K., Xu, H., Wang, H., Qiu, R., Hu, Q., & Liu, X. (2024). Digital twin-driven safety management and decision support approach for port operations and logistics. Frontiers in Marine Science, 11, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1455522.

- Wang, P., Ma, X., Fei, L., Zhang, H., Zhao, D., & Zhao, J. (2023). When the digital twin meets the preventive conservation of movable wooden artifacts. Heritage Science, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00894-8.

- Werbińska-Wojciechowska, S., Giel, R., & Winiarska, K. (2024). Digital Twin approach for operation and maintenance of transportation system – systematic review. Sensors 2024, 24, 1–62.

- Zhou, B., Zhang, X., Wan, X., Liu, T., Liu, Y., Huang, H., & Chen, J. (2024). Development and Application of a Novel Tsunami Monitoring System Based on Submerged Mooring. Sensors, 24(18), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24186048.

- Zhou, F., Yu, K., Xie, W., Lyu, J., Zheng, Z., & Zhou, S. (2024 a). Digital Twin-Enabled Smart Maritime Logistics Management in the Context of Industry 5.0. IEEE Access, 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3354838.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).