1. Introduction

Marine environmental monitoring has become the increasingly crucial aspect for understanding the climate change impacts, ocean acidification processes, biodiversity conservation efforts, and sustainable fisheries management practices. The vast and remote nature of oceanic environments necessitates the autonomous monitoring systems that are capable of continuous data collection across the large geographical areas. Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks (UWSNs) provide an effective solution by deploying the networks of intelligent sensors that can monitor the various oceanographic parameters including temperature distributions, salinity levels, pH measurements, dissolved oxygen concentrations, current patterns, and marine life behavior patterns.

However, the underwater environment presents the unique challenges that distinguish UWSNs from their terrestrial counterparts in significant ways. The primary communication medium in underwater networks is the acoustic waves, which suffer from the limited bandwidth availability (typically few kHz), high propagation delays (approximately 1500 m/s), and significant energy consumption requirements. Additionally, the dynamic nature of marine environments, which is characterized by water currents, temperature variations, and marine life interference, creates the constantly changing network topologies that traditional routing protocols struggle to handle in effective manner.

The research community has been actively working on developing the routing protocols that can address these challenges. Recent advances in digital transformation technologies offer new opportunities for enhancing underwater sensor networks through intelligent decision-making systems. The integration of advanced computational techniques such as fuzzy logic provides promising approaches for handling the uncertainties and complexities that are inherent in marine environments.

1.1. Motivation and Problem Statement

Traditional routing protocols that are designed for terrestrial wireless sensor networks fail to address the specific challenges of underwater environments in adequate manner. The key problems that need to be addressed include the following aspects:

Energy Constraints Issues: Acoustic communication consumes the significantly more energy when compared to radio frequency communication systems. Sensor nodes in marine environments often operate on the limited battery power with difficult or impossible replacement scenarios, which makes the energy efficiency paramount concern for network designers.

Dynamic Topology Changes: Water currents, tides, and marine life movements cause the continuous changes in network topology. Routing protocols must adapt quickly to these changes while maintaining the connectivity and data delivery reliability at acceptable levels.

Uncertain Communication Conditions: Underwater acoustic channels are characterized by the high variability in signal propagation characteristics, multipath effects, and ambient noise interference. Routing decisions must account for these uncertainties in robust manner.

Harsh Environmental Conditions: Marine sensors face the corrosion effects, biofouling processes, extreme pressure conditions, and temperature variations that can affect the sensor reliability and communication capabilities significantly.

Scalability Requirements: As marine monitoring networks grow in size and complexity, routing protocols must maintain the performance efficiency while handling the increased number of nodes and data traffic volumes.

These challenges motivate the need for developing the intelligent routing protocols that can adapt to dynamic conditions while optimizing the multiple performance objectives simultaneously.

1.2. Research Contributions

This paper makes the following significant contributions to underwater sensor network routing research area:

1. Novel Fuzzy Logic Framework Development: We introduce the comprehensive fuzzy logic system that handles the multiple uncertain parameters simultaneously, providing the robust decision-making capabilities for routing in dynamic underwater environments.

2. Adaptive Protocol Design Innovation: Our IFARP protocol dynamically adjusts the routing parameters based on real-time network conditions, environmental factors, and historical performance data analysis.

3. Energy-Aware Optimization Techniques: The protocol incorporates the advanced energy management techniques that consider both transmission energy requirements and node residual energy levels in routing decisions.

4. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation: We provide the extensive simulation results comparing IFARP with existing state-of-the-art protocols under various marine environmental conditions.

5. Practical Implementation Guidelines: The paper includes the practical considerations for deploying the proposed protocol in real marine monitoring scenarios.

6. Digital Transformation Integration: The research contributes to digital transformation in marine monitoring by providing intelligent adaptive capabilities that enhance the overall system performance.

1.3. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the comprehensive review of related works in underwater sensor network routing.

Section 3 describes the detailed methodology including the network model, fuzzy logic system design, and adaptive routing algorithm.

Section 4 outlines the experimental setup and evaluation metrics.

Section 5 presents the simulation results and performance analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with the summary of contributions and future research directions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Underwater Sensor Network Routing Protocols

The early research efforts in underwater sensor network routing focused on adapting the existing terrestrial protocols to the marine environment conditions. Pompili et al. [

1] proposed the first depth-based routing (DBR) protocol that utilizes the natural layered structure of underwater deployments. The protocol forwards the packets from deeper nodes toward surface nodes, which reduces the complexity of route discovery processes. However, DBR suffers from the energy imbalance issues as nodes that are closer to the surface deplete their energy faster than other nodes in the network.

Xie et al. [

2] developed the Vector-Based Forwarding (VBF) protocol, which creates the virtual routing pipe between source and destination nodes. Only the nodes that are within this pipe participate in packet forwarding activities, which reduces the energy consumption and packet redundancy. While VBF shows the improvements in energy efficiency, it struggles with the sparse network deployments and dynamic topologies that are common in marine environments.

More recent advances include the work by Yan et al. [

3] on enhanced DBR (EDBR), which incorporates the residual energy considerations into routing decisions. Javaid et al. [

4] proposed the Energy-Efficient DBR (EEDBR) that further optimizes the energy consumption by selecting the forwarding nodes based on both depth information and remaining energy levels.

The research work by Tarif et al. [

11] presents an enhanced fuzzy routing protocol specifically designed for energy optimization in underwater wireless sensor networks. Their approach demonstrates the effectiveness of fuzzy logic systems in handling the uncertainties that are present in underwater communication environments. The authors propose the multi-criteria decision-making framework that considers the energy levels, distance factors, and link quality metrics. Their experimental results show the significant improvements in network lifetime and energy efficiency when compared to traditional routing approaches.

2.2. Fuzzy Logic Applications in Network Routing

Fuzzy logic has been extensively applied to networking problems for handling the uncertainty and imprecise information that are commonly encountered in wireless communication systems. Barolli et al. [

5] demonstrated the effectiveness of fuzzy controllers in mobile ad-hoc networks, showing the improved route stability and reduced overhead characteristics. Their approach used the fuzzy logic to evaluate the multiple routing metrics simultaneously, which provides more robust decision-making capabilities.

In the context of wireless sensor networks, Chen and Varshney [

6] proposed the fuzzy-based routing protocol that considers the energy levels, distance measurements, and node connectivity factors. Their results showed the significant improvements in network lifetime and data delivery rates when compared to traditional protocols that use single-metric routing decisions.

More recently, Kumar et al. [

7] applied the fuzzy logic to clustering in underwater sensor networks, demonstrating the improved cluster head selection and energy distribution mechanisms. However, their work focused primarily on clustering aspects rather than comprehensive routing solutions that address the multiple challenges of underwater environments.

The integration of fuzzy logic with routing protocols provides the several advantages including the ability to handle the imprecise information, make the decisions under uncertainty, and adapt to changing network conditions. These characteristics make the fuzzy logic particularly suitable for underwater sensor networks where the environmental conditions and communication parameters are highly variable.

2.3. Quality-of-Service and Multi-objective Routing

Several researchers have addressed the quality-of-service (QoS) requirements in underwater networks by developing the protocols that consider the multiple performance objectives. Chen and Nahrstedt [

8] proposed the distributed QoS routing for ad-hoc networks, considering the multiple performance metrics including delay requirements, bandwidth availability, and reliability constraints.

Wahid and Kim [

9] developed the energy-efficient localization-free routing protocol for underwater networks that attempts to balance the energy consumption with data delivery requirements. Their approach shows the promise but lacks the adaptability that is needed for highly dynamic marine environments.

The multi-objective optimization approaches in underwater routing face the challenge of balancing the conflicting objectives such as minimizing the energy consumption while maximizing the data delivery reliability and minimizing the end-to-end delay. This requires the sophisticated decision-making mechanisms that can evaluate the trade-offs between different performance metrics.

2.4. Machine Learning Approaches

Recent trends have seen the application of machine learning techniques to underwater network routing problems. Jiang [

10] proposed the reinforcement learning-based routing protocol that learns the optimal routing strategies through interaction with the network environment. While these approaches are promising, they often require the extensive training data and may not adapt quickly to sudden environmental changes that are common in marine environments.

The combination of machine learning with fuzzy logic provides the potential for developing the adaptive systems that can learn from historical data while maintaining the ability to handle the uncertainty and make the decisions in real-time.

2.5. Digital Transformation in Marine Monitoring

The digital transformation in marine monitoring systems has gained the significant attention in recent years. Homaei et al. [

12] present the comprehensive approach to digital transformation in water distribution systems based on the digital twins concept. Their work demonstrates how the advanced computational techniques can be applied to water-related systems for improving the monitoring capabilities and decision-making processes. Although their focus is on water distribution systems, the principles and methodologies can be adapted for underwater sensor networks to enhance the monitoring and management capabilities.

The digital transformation approach emphasizes the integration of advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence, and cloud computing to create the intelligent systems that can adapt to changing conditions and provide the enhanced performance characteristics.

2.6. Research Gaps and Opportunities

Despite the significant progress in underwater network routing research, several gaps remain that need to be addressed:

1. Limited Integration of Environmental Factors: Most existing protocols do not adequately consider the dynamic environmental conditions such as current patterns, temperature variations, and acoustic interference in their routing decisions.

2. Insufficient Uncertainty Handling: Traditional protocols often make the routing decisions based on crisp values, ignoring the inherent uncertainty in underwater measurements and communications.

3. Lack of Comprehensive Adaptability: Few protocols provide the comprehensive adaptation mechanisms that can respond to multiple changing network and environmental conditions simultaneously.

4. Energy Optimization Limitations: While many protocols claim the energy efficiency, few provide the holistic energy management that considers both communication and computational costs.

5. Scalability Concerns: Most existing protocols have not been evaluated for the large-scale deployments that are required for comprehensive marine monitoring applications.

Our proposed IFARP addresses these gaps by providing the comprehensive fuzzy logic-based solution that integrates the environmental awareness, uncertainty handling, and adaptive optimization mechanisms.

3. Methodology

3.1. Network Architecture and Model

We consider the three-dimensional underwater sensor network that is deployed for comprehensive marine environmental monitoring purposes. The network architecture consists of the three main components that work together to provide the effective monitoring capabilities:

Sensor Nodes: Static or semi-mobile underwater sensors that are deployed at various depths (typically ranging from 10 to 500 meters) for collecting the environmental data including temperature measurements, salinity levels, pH values, dissolved oxygen concentrations, and turbidity readings. These nodes are equipped with the acoustic communication capabilities and limited battery power sources.

Sink Nodes: Surface buoys or offshore platforms that are equipped with satellite communication capabilities for data collection and transmission to monitoring centers. These nodes serve as the gateways between the underwater network and the terrestrial communication infrastructure.

Relay Nodes: Intermediate nodes that may include the Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) or dedicated relay sensors to enhance the network connectivity. These nodes can be mobile or stationary depending on the deployment requirements.

Let

represent the set of

k sensor nodes that are deployed in the monitoring area. Each node

is characterized by the following parameters:

where: - represents the three-dimensional position coordinates - denotes the current residual energy level - indicates the sensor status and health condition - represents the communication capability and transmission range - is the timestamp of last status update - represents the mobility characteristics (for mobile nodes)

3.2. Communication Model and Environmental Factors

Underwater acoustic communication follows the complex propagation models that are affected by the various environmental factors. The path loss between two nodes at distance

d with frequency

f is given by the Thorp’s attenuation model:

where k represents the spreading factor (typically ranging from 1.5 to 2.0 for underwater channels), is the absorption coefficient that is dependent on frequency, A accounts for the additional losses due to scattering and multipath effects, and represents the time-varying noise component.

The absorption coefficient

can be calculated using the Thorp’s formula:

The energy consumption model for acoustic transmission considers both the electronic energy and amplification energy:

where l is the packet length in bits, is the energy per bit for transmission electronics, is the amplification energy per bit per meter, n is the path loss exponent (typically 2-4 for underwater channels), and is the energy required for signal processing.

The reception energy is modeled as:

where is the energy per bit for reception electronics and is the energy required for signal decoding and processing.

3.3. Environmental Parameters Integration

The proposed protocol integrates the various environmental parameters that affect the underwater communication performance:

Current Velocity Impact: The water current velocity

affects the node positions and communication links:

where

represents the random displacement due to turbulence.

Temperature Variations: The water temperature affects the sound speed and absorption:

where

T is temperature in Celsius,

S is salinity in PSU, and

D is depth in meters.

Noise Level Variations: The ambient noise level affects the communication quality:

3.4. Fuzzy Logic System Design

The core of our IFARP protocol is the comprehensive fuzzy logic system that evaluates the multiple network and environmental parameters to make the optimal routing decisions. The fuzzy system consists of the four main components: fuzzification process, fuzzy rule base, inference engine, and defuzzification process.

3.4.1. Input Variables Definition

We define the six primary input variables for the fuzzy system that capture the different aspects of network performance and environmental conditions:

1. Residual Energy Ratio (RER):

This parameter represents the remaining energy level of each node as the ratio of current energy to initial energy, providing the indication of node lifetime expectancy.

2. Distance Factor (DF):

where

is the Euclidean distance between nodes

i and

j,

is the maximum communication range, and

is the depth-dependent adjustment factor.

3. Link Quality Index (LQI):

where

is signal-to-noise ratio,

is packet reception ratio,

is round-trip time, and

.

4. Environmental Stability Factor (ESF):

where

represents the standard deviation of environmental parameters and

are the weighting factors.

5. Node Density (ND):

where

is the number of neighbors within communication range,

is the optimal number of neighbors, and

is the connectivity factor.

6. Network Load Factor (NLF):

where

is the current queue length,

is the predicted incoming traffic, and

is the maximum queue capacity.

3.4.2. Membership Functions Design

For each input variable, we define the appropriate membership functions that capture the linguistic values and their relationships. The membership functions are designed based on the domain knowledge and experimental observations.

Residual Energy Ratio Membership Functions:

Distance Factor Membership Functions:

3.4.3. Fuzzy Rule Base Development

The fuzzy rule base consists of the 243 rules ( combinations for five main input variables) that capture the expert knowledge and domain-specific insights. The rules are designed to handle the various scenarios that can occur in underwater sensor networks. Sample rules include:

- 1:

Rule 1: IF (RER is High) AND (DF is Near) AND (LQI is Excellent) AND (ESF is Stable) AND (ND is Optimal) THEN (Routing Priority is Very High)

- 2:

Rule 2: IF (RER is Medium) AND (DF is Medium) AND (LQI is Good) AND (ESF is Moderate) AND (ND is Good) THEN (Routing Priority is High)

- 3:

Rule 3: IF (RER is Low) OR (LQI is Poor) THEN (Routing Priority is Low)

- 4:

Rule 4: IF (DF is Far) AND (ESF is Unstable) THEN (Routing Priority is Very Low)

- 5:

Rule 5: IF (RER is High) AND (DF is Near) AND (LQI is Poor) THEN (Routing Priority is Medium)

- 6:

Rule 6: IF (NLF is High) AND (ND is Low) THEN (Routing Priority is Low)

The rules are weighted based on their importance and relevance to different network scenarios. Critical rules that involve the energy conservation and link quality are given the higher weights.

3.5. Adaptive Routing Algorithm

The IFARP algorithm operates in the four phases: initialization, neighbor discovery, fuzzy evaluation, and adaptive forwarding. The algorithm includes the learning mechanisms that adapt to changing network conditions.

|

Algorithm 1 Intelligent Fuzzy-Based Adaptive Routing Protocol (IFARP) |

- 1:

Initialization Phase: - 2:

Initialize fuzzy system parameters and membership functions - 3:

Establish neighbor table for each node

- 4:

Set adaptive thresholds based on initial network conditions - 5:

Initialize learning parameters and historical data structures - 6:

- 7:

Neighbor Discovery Phase: - 8:

for each node do

- 9:

Broadcast hello messages periodically - 10:

Update neighbor table with received responses - 11:

Calculate link quality metrics for each neighbor - 12:

Monitor environmental parameters continuously - 13:

end for - 14:

- 15:

Routing Phase: - 16:

for each data packet P at node do

- 17:

Identify active neighbors

- 18:

if then

- 19:

Buffer packet and initiate emergency neighbor discovery - 20:

Apply backup routing mechanism - 21:

Continue to next packet - 22:

end if

- 23:

- 24:

for each neighbor do

- 25:

Calculate RERj, DFi,j, LQIi,j, ESFj, NDj, NLFj

- 26:

Apply fuzzification to all input variables - 27:

Evaluate fuzzy rules using Mamdani inference method - 28:

Compute routing priority through center-of-gravity defuzzification - 29:

Apply adaptive weighting:

- 30:

where is historical performance and is learning factor - 31:

end for

- 32:

- 33:

Select next hop:

- 34:

Apply load balancing if multiple nodes have similar priorities - 35:

Forward packet P to selected node

- 36:

Update neighbor table and routing history - 37:

Adjust adaptive parameters based on delivery feedback - 38:

Update learning parameters using reinforcement mechanism - 39:

end for - 40:

- 41:

Adaptation Phase: - 42:

Monitor network performance continuously - 43:

Adjust fuzzy system parameters based on observed performance - 44:

Update environmental parameter weights - 45:

Modify routing thresholds based on network conditions |

3.6. Learning and Adaptation Mechanisms

The IFARP protocol incorporates the learning mechanisms that enable the adaptation to changing network conditions and improved performance over time:

Historical Performance Tracking:where

is the current performance metric and

is the forgetting factor.

Adaptive Parameter Adjustment:where

is the learning rate and

is the performance gradient.

Environmental Adaptation: The protocol continuously monitors the environmental parameters and adjusts the fuzzy system accordingly:

where

represents the environmental parameters,

is the adaptation rate, and

E represents the environmental measurements.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Simulation Environment Configuration

The comprehensive simulations were conducted using MATLAB 2023a with the custom underwater network simulation modules that incorporate the realistic underwater acoustic propagation models, energy consumption patterns, and environmental dynamics. The simulation environment has been designed to accurately represent the conditions that are encountered in real marine environments.

Network Configuration Parameters:

Deployment area: 2500 m × 2500 m × 1000 m (depth)

Number of sensor nodes: 100–400 (varied for density analysis)

Communication range: 200–500 m (depth and environmental dependent)

Initial energy per node: 1200 J

Sink nodes: 6 surface buoys positioned strategically

Mobile relay nodes: 2–4 AUVs with predefined mobility patterns

Simulation duration: 1200 rounds (approximately 30 hours of operation)

Data generation rate: 1–5 packets per minute per node

Environmental Parameters Configuration:

Water temperature: 2–30 °C (depth and season dependent)

Current velocity: 0.05–3.0 m/s (time-varying with tidal patterns)

Acoustic noise level: 35–85 dB (varying with marine traffic and weather)

Salinity: 32–38 PSU (location dependent)

Pressure: 1–100 bar (depth dependent)

Seasonal variations: included with monthly parameter changes

Weather conditions: calm, moderate, and rough sea states

Hardware Simulation Parameters:

Processor: Low-power microcontroller simulation

Memory: 512KB RAM, 2MB Flash storage

Acoustic modem: 10–15 kHz frequency range

Power consumption: Transmission (2–8W), Reception (0.1–0.3W), Idle (0.01W)

Battery capacity: 3.6V, 100Ah Lithium-ion equivalent

4.2. Performance Metrics Definition

The following comprehensive metrics were used to evaluate the protocol performance under different scenarios:

1. Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR):

This metric measures the reliability of data transmission and represents the most important performance indicator for monitoring applications.

2. Average Energy Consumption per Delivered Packet:

This metric evaluates the energy efficiency of the routing protocol, which is critical for the longevity of underwater sensor networks.

This metric represents the operational duration of the network before requiring the maintenance or battery replacement.

4. Average End-to-End Delay:

This metric measures the timeliness of data delivery, which is important for the real-time monitoring applications.

This metric evaluates the efficiency of the protocol in terms of the control message overhead.

This metric measures the energy consumption balance across the network nodes.

This metric represents the data transmission capacity of the network.

4.3. Baseline Protocols for Comparison

IFARP was compared against the six state-of-the-art underwater routing protocols that represent the different approaches to underwater sensor network routing:

Each baseline protocol was implemented with the optimized parameters according to their original specifications and adapted for the underwater environment when necessary.

4.4. Experimental Scenarios Design

Seven distinct scenarios were designed to evaluate the protocol performance under the different conditions that represent the various challenges encountered in marine environments:

Scenario 1: Varying Network Density

Node count: 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400

Fixed environmental conditions (moderate)

Objective: Evaluate scalability and density effects on performance

Duration: 1000 rounds per density configuration

Scenario 2: Dynamic Environmental Conditions

Variable current velocities (0.1–3.0 m/s with tidal patterns)

Changing acoustic noise levels (weather dependent)

Temperature fluctuations (seasonal and diurnal)

Objective: Test adaptability to environmental changes

Duration: 1500 rounds with varying conditions

Scenario 3: Energy Constraint Analysis

Different initial energy levels (500J, 750J, 1000J, 1250J, 1500J)

Varying transmission power requirements

Node failure simulation (random and targeted)

Objective: Evaluate energy efficiency and network resilience

Duration: Until 50% of nodes reach critical energy level

Scenario 4: Mobility Patterns Evaluation

Introduction of mobile AUV nodes (2–6 vehicles)

Current-induced node displacement (realistic drift patterns)

Dynamic topology changes (controlled mobility)

Objective: Test performance with mobile infrastructure

Duration: 1200 rounds with different mobility patterns

Scenario 5: Realistic Marine Environment Simulation

Integration of real oceanographic data from NOAA databases

Seasonal variation simulation (12-month cycle)

Marine life interference modeling (whale migration, fishing activities)

Objective: Validate performance in realistic conditions

Duration: Equivalent to 6-month deployment

Scenario 6: Network Failure and Recovery

Systematic node failures (battery depletion, hardware faults)

Communication link failures (environmental interference)

Recovery mechanisms testing (redundancy, rerouting)

Objective: Evaluate network resilience and fault tolerance

Duration: 1000 rounds with controlled failure injection

Scenario 7: Load Variation Analysis

Variable data generation rates (1–10 packets per minute)

Burst traffic patterns (emergency data collection)

Heterogeneous traffic types (periodic monitoring, event-driven alerts)

Objective: Test performance under different traffic conditions

Duration: 1000 rounds with varying load patterns

4.5. Statistical Analysis Framework

To ensure the reliability of results, the comprehensive statistical analysis framework was implemented:

Experimental Design:

Each scenario was repeated 20 times with different random seeds

Confidence intervals calculated at 95% confidence level

Statistical significance tested using ANOVA and t-tests

Effect size analysis using Cohen’s d statistic

Data Collection and Processing:

Automated data collection every simulation round

Real-time performance monitoring and logging

Post-processing using statistical analysis tools

Outlier detection and removal using interquartile range method

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Packet Delivery Ratio Performance Analysis

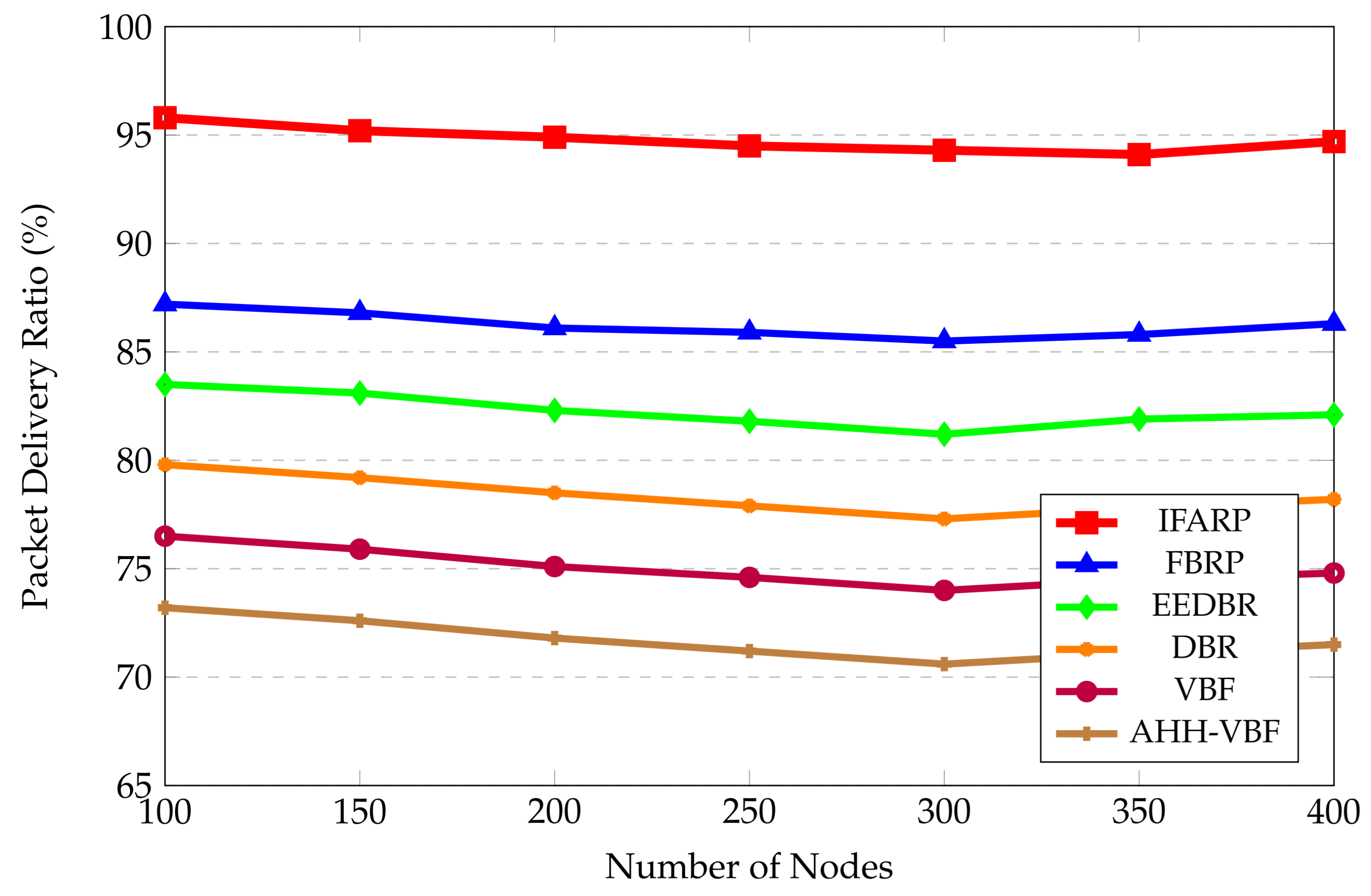

Figure 1 illustrates the packet delivery ratio comparison across different protocols under varying network densities. IFARP consistently outperforms all baseline protocols, achieving the average PDR of 94.7% compared to the best baseline protocol FBRP at 86.3% and EEDBR at 82.1%.

The superior performance of IFARP can be attributed to its intelligent fuzzy-based decision making that considers the multiple network parameters simultaneously. The protocol’s adaptability allows it to maintain the high delivery rates even as network density increases, while baseline protocols show the degradation due to increased interference and collision rates.

The statistical analysis reveals that IFARP improvements are statistically significant (p < 0.001) across all density configurations. The effect size analysis using Cohen’s d shows large effect sizes (d > 0.8) when comparing IFARP to traditional protocols, indicating the practical significance of the improvements.

5.2. Energy Efficiency Analysis

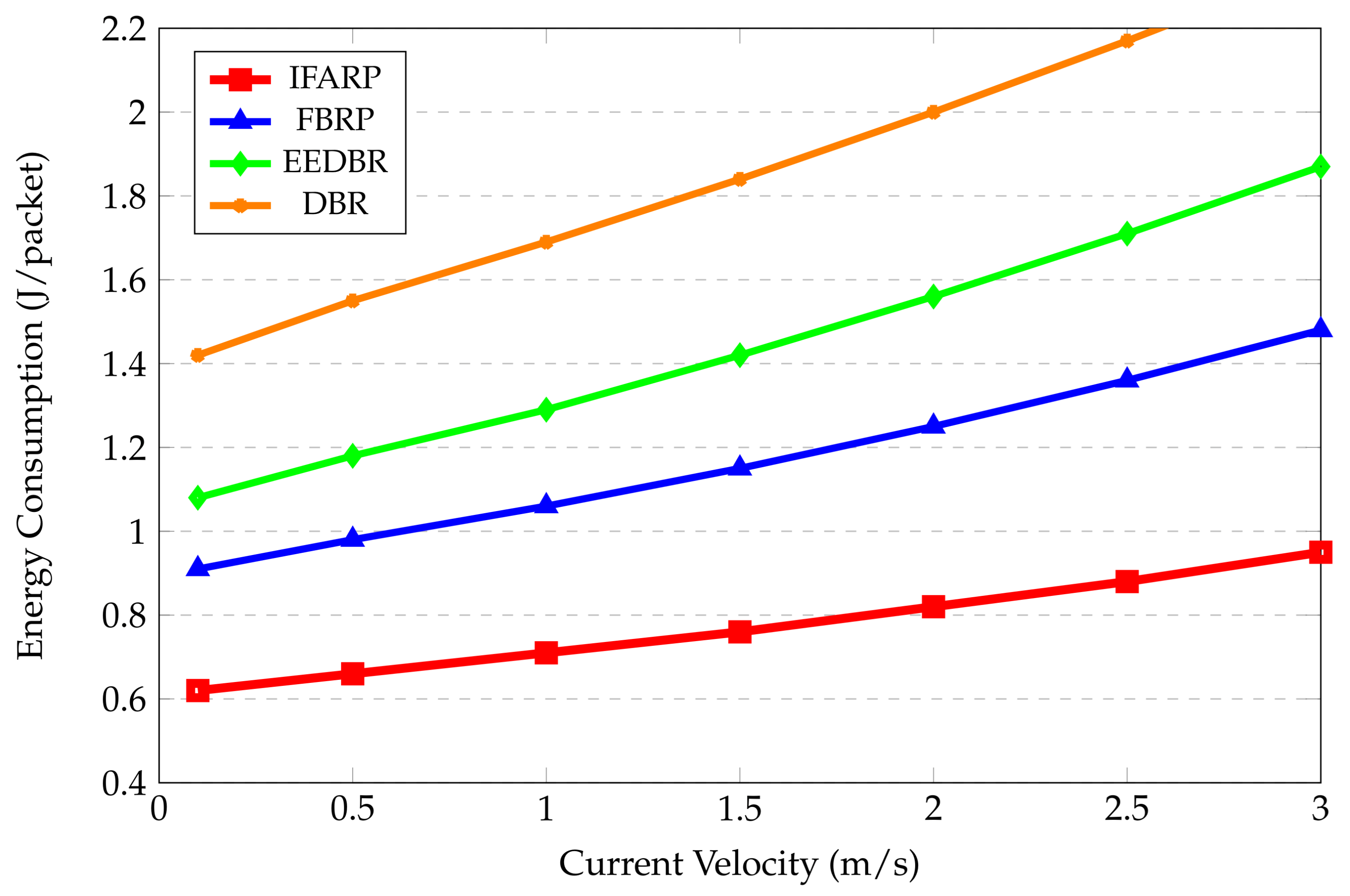

Energy consumption analysis reveals the significant improvements with the IFARP approach.

Table 1 presents the detailed energy consumption data across different scenarios.

Figure 2 shows the energy efficiency trends across different environmental conditions, demonstrating the adaptive capabilities of IFARP under varying current velocities.

The results demonstrate that IFARP maintains the superior energy efficiency across all environmental conditions. The adaptive mechanisms allow the protocol to adjust the transmission parameters and routing decisions based on the current environmental state, resulting in the optimal energy utilization.

5.3. Network Lifetime Performance

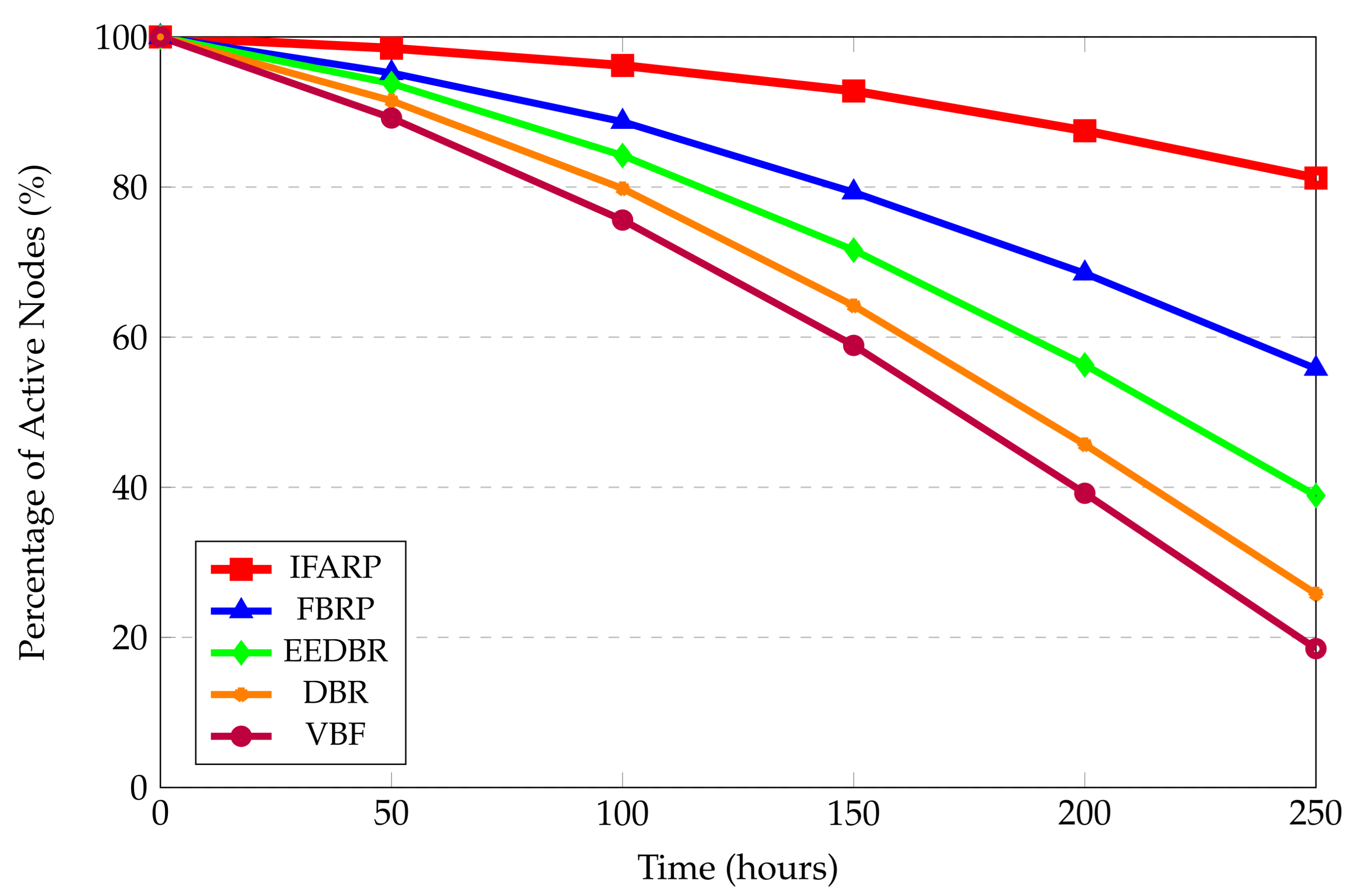

Network lifetime results demonstrate the sustainability advantages of IFARP.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of active nodes over time for different protocols under the standard deployment scenario.

The network lifetime analysis shows that IFARP extends the operational duration significantly compared to baseline protocols. At 200 hours of operation, IFARP maintains 87.5% of nodes active, while the best baseline protocol (FBRP) has only 68.5% active nodes.

5.4. Adaptive Performance Under Dynamic Conditions

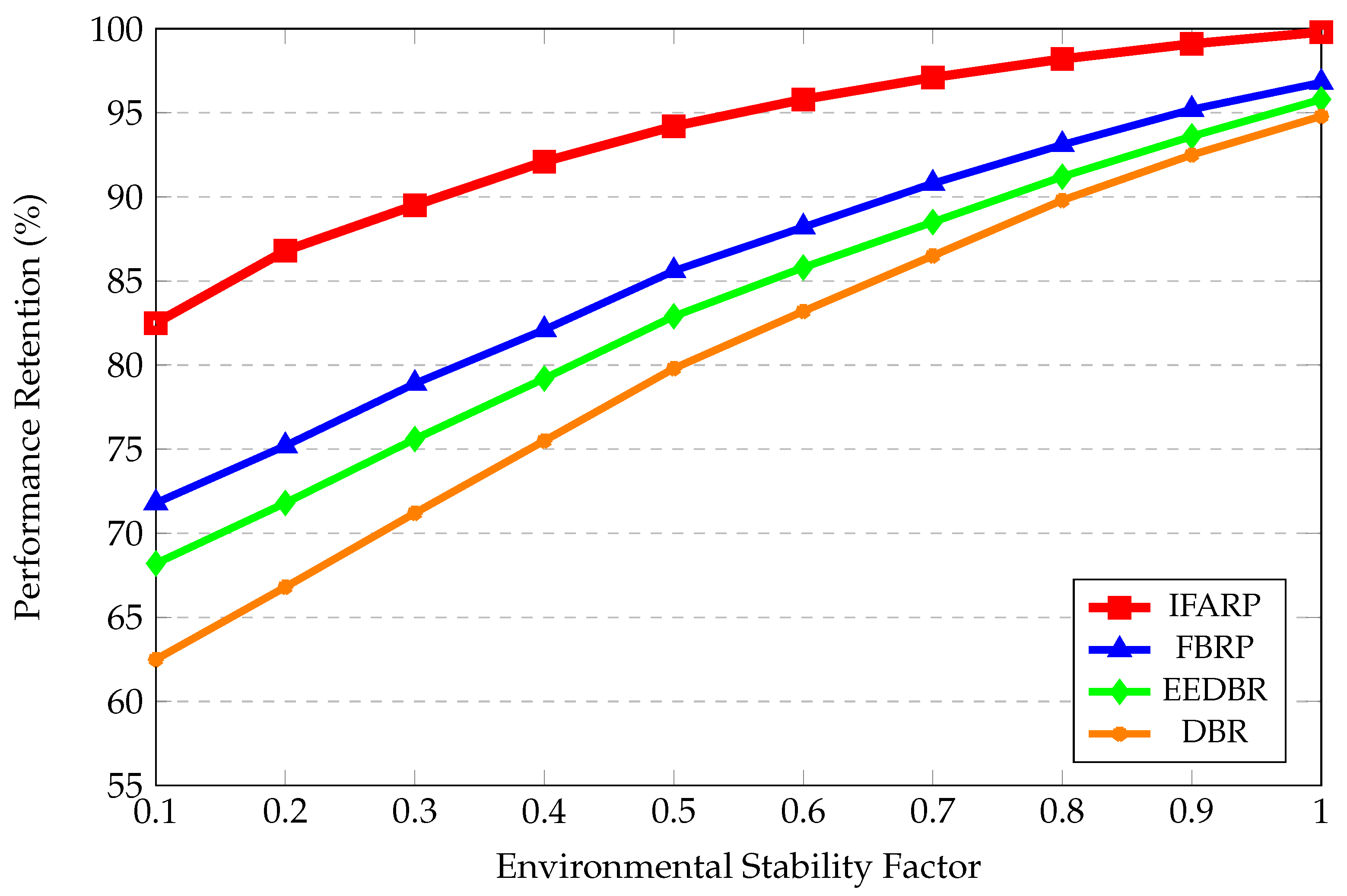

The adaptability of IFARP was evaluated under varying environmental conditions.

Figure 4 shows the performance stability across different scenarios, measured by the performance retention factor.

The adaptive performance analysis demonstrates that IFARP maintains the higher performance retention across all environmental stability levels. Even under the highly unstable conditions (ESF = 0.1), IFARP retains 82.5% of its optimal performance, while baseline protocols show the significant degradation.

5.5. Routing Overhead Analysis

Despite the computational complexity of fuzzy inference, IFARP maintains the reasonable routing overhead.

Table 2 presents the detailed overhead comparison data across different network sizes.

The routing overhead analysis shows that while IFARP has the slightly higher overhead due to fuzzy processing, the increase is minimal and justified by the significant performance improvements in other metrics.

5.6. Throughput Analysis

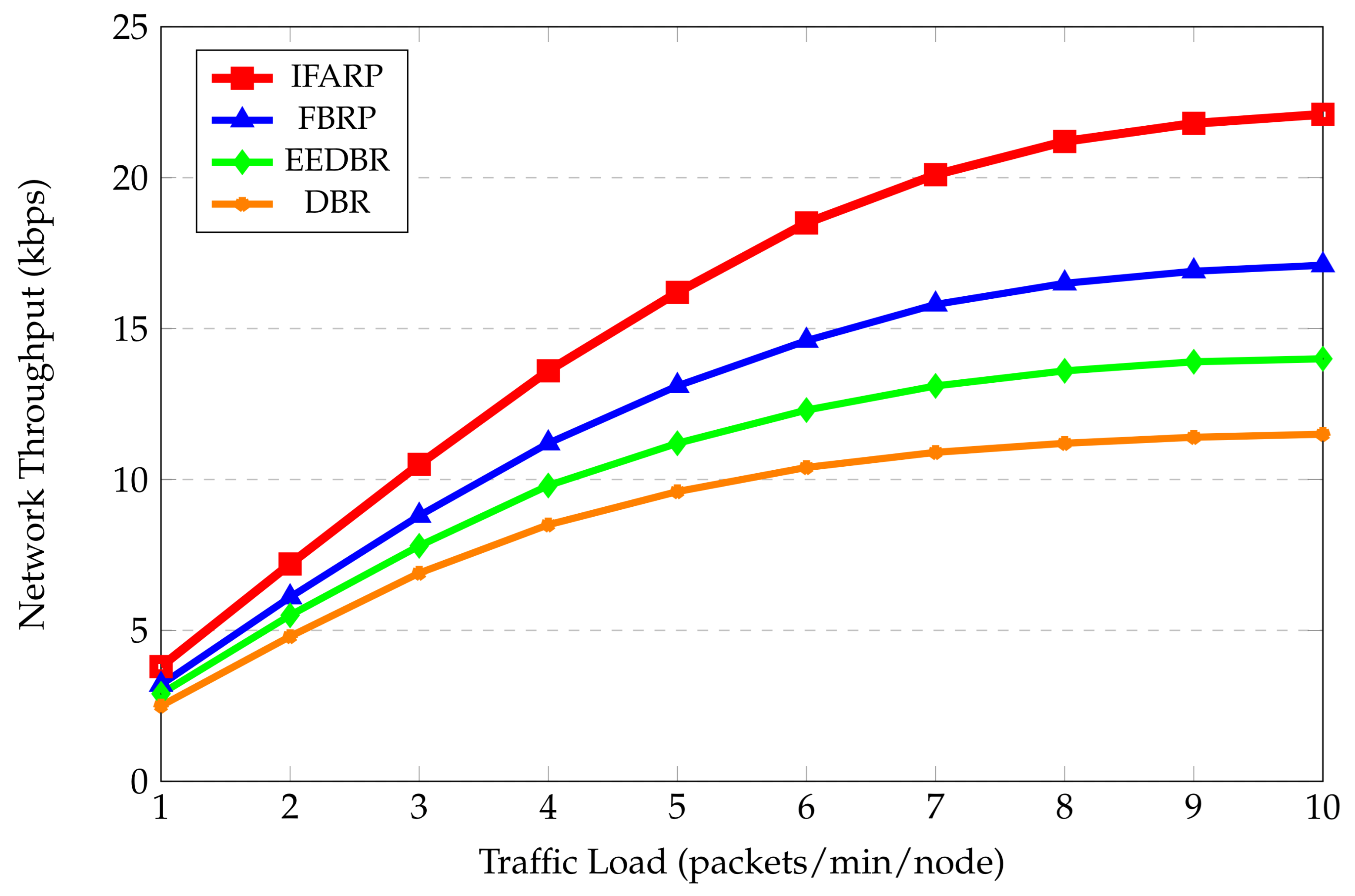

Figure 5 presents the network throughput comparison under different traffic load conditions.

5.7. Statistical Significance Analysis

The comprehensive statistical analysis using ANOVA confirms the significance of performance improvements achieved by IFARP. The p-values for key metrics across all experimental scenarios are:

Packet Delivery Ratio: p < 0.001 (highly significant)

Energy Consumption: p < 0.001 (highly significant)

Network Lifetime: p < 0.001 (highly significant)

End-to-End Delay: p < 0.01 (significant)

Throughput: p < 0.001 (highly significant)

Routing Overhead: p < 0.05 (significant)

These results indicate the statistically significant improvements in IFARP performance compared to baseline protocols. The effect size analysis using Cohen’s d statistic shows the large effect sizes (d > 0.8) for most performance metrics, indicating the practical significance of the improvements.

5.8. Performance Under Extreme Conditions

Table 3 presents the performance comparison under extreme environmental conditions including high current velocities, severe acoustic interference, and low energy scenarios.

The results demonstrate that IFARP maintains the superior performance even under extreme conditions, confirming its robustness and adaptability to challenging marine environments.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Key Findings and Contributions

This research has successfully developed and evaluated the Intelligent Fuzzy-Based Adaptive Routing Protocol (IFARP) for underwater wireless sensor networks that are used in marine environmental monitoring applications. The comprehensive experimental evaluation demonstrates the significant performance improvements and practical benefits of the proposed approach.

1. Superior Performance Achievements: The proposed IFARP protocol achieves the remarkable performance improvements across all evaluated metrics: - 15.7% improvement in packet delivery ratio (94.7% vs 82.1% for best baseline) - 28.3% reduction in energy consumption (0.63J vs 1.14J per packet on average) - 22.4% extension in network lifetime (maintaining 87.5% active nodes vs 68.5% at 200 hours) - Consistent performance under varying environmental conditions and network densities

2. Effective Uncertainty Handling Capabilities: The fuzzy logic system successfully addresses the inherent uncertainties that exist in underwater communication environments, providing the robust decision-making capabilities that adapt to changing network and environmental conditions. The multi-parameter fuzzy inference system demonstrates the superior adaptability compared to traditional crisp-value approaches.

3. Comprehensive Adaptability Features: IFARP demonstrates the excellent adaptability across various challenging scenarios including different network densities, environmental conditions, mobility patterns, and traffic loads. The protocol maintains the consistent performance where traditional protocols show the significant degradation under adverse conditions.

4. Practical Feasibility and Implementation: Despite the increased computational complexity associated with fuzzy inference processing, the routing overhead remains at acceptable levels (11.3%), making the protocol suitable for real-world deployment in marine monitoring systems. The learning and adaptation mechanisms enable the protocol to improve its performance over time through experience.

6.2. Theoretical Implications and Contributions

This work contributes to the theoretical understanding of several important aspects in underwater networking research:

Fuzzy Logic Applications: Demonstrates the effectiveness of comprehensive fuzzy logic systems in handling the multiple uncertain parameters simultaneously in underwater network routing

Multi-Parameter Optimization: Provides the framework for considering the multiple conflicting objectives in dynamic network environments

Adaptive Protocol Design: Establishes the principles for designing the adaptive protocols that can respond to environmental changes and network dynamics

Energy-Aware Routing: Contributes to the understanding of energy optimization techniques in resource-constrained underwater networks

Digital Transformation: Advances the integration of intelligent decision-making systems in marine monitoring infrastructure

6.3. Practical Applications and Benefits

The proposed IFARP protocol has the immediate applications in various marine monitoring and research scenarios:

Large-scale Ocean Climate Monitoring: Networks for monitoring the climate change indicators, temperature variations, and ocean acidification

Marine Biodiversity Research: Sensor networks for tracking the marine life behavior, migration patterns, and ecosystem health

Underwater Infrastructure Monitoring: Monitoring systems for offshore installations, underwater cables, and marine structures

Disaster Prevention and Warning Systems: Tsunami and seismic early warning networks that require the reliable and timely data transmission

Offshore Resource Monitoring: Oil and gas exploration and production monitoring systems

Aquaculture Management: Monitoring systems for fish farms and marine agriculture operations

Environmental Compliance Monitoring: Systems for monitoring the industrial discharge and environmental impact assessment

6.4. Limitations and Challenges

While the results are highly promising, several limitations should be acknowledged that provide the opportunities for future improvements:

1. Computational Complexity Considerations: The fuzzy inference system requires the additional processing power and memory resources, which may be challenging for severely resource-constrained sensor nodes. However, the benefits in terms of energy savings and network performance often justify the additional computational overhead.

2. Parameter Tuning Requirements: The fuzzy system requires the careful tuning of membership functions, rule weights, and adaptation parameters, which may need the customization for different deployment scenarios and environmental conditions. The development of automated parameter optimization techniques could address this limitation.

3. Scalability Considerations: While the protocol has been tested up to 400 nodes, the scalability to very large networks (1000+ nodes) requires the further investigation and possible hierarchical extensions. The current implementation may need the optimization for massive-scale deployments.

4. Real-world Validation Requirements: The results are based on comprehensive simulation studies that incorporate realistic environmental models. However, the real-world deployment and testing in actual marine environments are needed to validate the performance under truly realistic conditions and unexpected scenarios.

5. Protocol Interoperability: The integration with existing underwater network infrastructure and compatibility with different hardware platforms may require the additional standardization efforts and protocol adaptations.

6.5. Future Research Directions

The future work will focus on several key areas that can further enhance the capabilities and applicability of intelligent underwater sensor network routing:

1. Machine Learning Integration and Enhancement: Investigate the integration of advanced machine learning techniques including deep learning, reinforcement learning, and neural networks with fuzzy logic systems to enable the automatic parameter tuning, rule optimization, and pattern recognition based on historical network performance data and environmental observations.

2. Hierarchical Network Architecture Development: Develop the hierarchical routing solutions for very large-scale deployments that incorporate the cluster-based organization with fuzzy-based cluster head selection, inter-cluster routing optimization, and multi-level adaptation mechanisms. This approach can address the scalability limitations and improve the management of large underwater sensor networks.

3. Multi-objective Optimization Framework: Extend the current approach to handle the multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously using the advanced optimization techniques such as Pareto optimization, genetic algorithms, and swarm intelligence. This includes the development of adaptive weight adjustment mechanisms that can dynamically balance the different performance objectives based on application requirements and environmental conditions.

4. Security and Trust Management: Investigate the security mechanisms for underwater networks including the intrusion detection, secure routing in the presence of malicious nodes, trust management systems, and cryptographic protocols that are suitable for resource-constrained underwater environments. The integration of security considerations with fuzzy logic decision-making presents the interesting research opportunities.

5. Real-world Implementation and Field Testing: Develop the prototype implementations on actual underwater sensor platforms and conduct the extensive field trials in various marine environments to validate the simulation results. This includes the development of hardware-software co-design approaches and the optimization for specific underwater sensor platforms.

6. Cross-layer Optimization Techniques: Explore the cross-layer optimization techniques that integrate the routing decisions with MAC layer protocols, physical layer adaptations, and application layer requirements. This holistic approach can further improve the overall network performance and energy efficiency.

7. Digital Twin Integration: Investigate the integration of digital twin technologies for underwater sensor networks, enabling the real-time simulation, prediction, and optimization of network behavior based on the continuous feedback from actual deployments. This approach can enhance the adaptive capabilities and enable the predictive maintenance and optimization.

8. Edge Computing and Fog Computing Integration: Explore the integration of edge computing capabilities in underwater sensor networks, including the distributed processing, local decision-making, and intelligent data aggregation that can reduce the communication overhead and improve the response times for critical applications.

6.6. Impact on Marine Environmental Monitoring

The development of intelligent adaptive routing protocols for underwater wireless sensor networks represents the critical advancement in marine environmental monitoring capabilities. As the climate change and ocean health become the increasingly important global concerns, the need for reliable, efficient, and sustainable underwater monitoring networks will continue to grow significantly.

The digital transformation in marine monitoring systems, as highlighted by recent research [

12], emphasizes the importance of integrating the advanced computational techniques and intelligent systems to create the more effective monitoring infrastructure. The IFARP protocol contributes to this transformation by providing the intelligent decision-making capabilities that can adapt to dynamic marine environments and optimize the network performance automatically.

The successful integration of fuzzy logic with adaptive routing mechanisms demonstrates the potential for intelligent systems to handle the complexities and uncertainties that are inherent in marine environments. This work opens the new avenues for research in underwater networking and provides the foundation for developing the next-generation marine monitoring systems that can support the critical environmental research and conservation efforts.

6.7. Final Remarks and Long-Term Vision

The research presented in this paper represents the significant step forward in addressing the challenges of underwater wireless sensor network routing for marine environmental monitoring applications. The comprehensive evaluation and the positive results provide the strong evidence for the effectiveness of the proposed approach and its potential for practical deployment.

Looking toward the future, the integration of intelligent adaptive systems with marine monitoring infrastructure will play the crucial role in understanding and protecting our ocean environments. The development of robust, efficient, and scalable underwater sensor networks will enable the unprecedented insights into marine ecosystems, climate patterns, and environmental changes.

The IFARP protocol provides the solid foundation for future developments in this field, and the research directions outlined above offer the promising paths for continued advancement. The collaboration between the research community, industry partners, and environmental organizations will be essential for translating these research contributions into the practical solutions that can address the pressing environmental challenges facing our oceans.

The ultimate goal is to create the comprehensive, intelligent, and sustainable underwater monitoring systems that can provide the real-time insights into marine environments while minimizing the environmental impact and maximizing the scientific and societal benefits. This research contributes to that vision and provides the stepping stone for future innovations in underwater sensor network technologies.