1. Introduction

Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks (UWSNs) have been emerged as enabling technologies for numerous marine applications including oceanographic data collection, pollution monitoring, offshore exploration, disaster prevention, assisted navigation, and tactical surveillance [

1]. These networks are consisting of spatially distributed autonomous sensor nodes which are equipped with acoustic modems that communicate through underwater acoustic channels. Unlike terrestrial radio frequency communications, underwater environments are imposing unique constraints: limited bandwidth (typically less than 100 kHz), high propagation delays (approximately 1500 m/s compared to light speed), severe multi-path effects, and significant energy consumption [

2].

The energy efficiency challenge in UWSNs is particularly acute. Battery replacement in submerged environments is expensive, dangerous, and often impractical, especially for deep-sea deployments [

3]. Traditional routing protocols which are designed for terrestrial wireless sensor networks are failing to address the specific characteristics of underwater acoustic propagation, and this is resulting in rapid energy depletion, network partitioning, and shortened operational lifetimes. Therefore, developing energy-efficient routing mechanisms that maximize network lifetime while maintaining reliable data delivery has become a paramount research objective in recent years.

Recent works have been exploring various approaches to address these challenges. The digital transformation concepts in network infrastructure, as discussed by Homaei et al. [

4], are providing new perspectives for optimization in distributed sensor systems. Their work on digital twins is demonstrating how advanced computational models can improve network management and resource allocation, which is particularly relevant for underwater sensor networks where physical access is limited.

1.1. Motivation and Challenges

Current underwater routing protocols are suffering from several fundamental limitations. Geographic routing protocols like Vector-Based Forwarding (VBF) [

5] and depth-based approaches such as DBR [

6] are relying on simplified assumptions that do not capture the complexity and uncertainty which is inherent in underwater environments. These protocols are typically optimizing a single metric and lacking adaptability to dynamic network conditions including node mobility, varying channel quality, and heterogeneous energy distributions.

Fuzzy logic systems have been demonstrated effectiveness in handling uncertainty and imprecise information in wireless networks [

7]. Recent work by Tarif et al. [

8] has presented an enhanced fuzzy routing protocol specifically designed for energy optimization in underwater wireless sensor networks. Their approach is showing promising results in addressing energy efficiency challenges through fuzzy inference mechanisms. However, most existing fuzzy-based underwater routing protocols, including this work, are lacking rigorous mathematical foundations with complete formal proofs. Most works are presenting heuristic approaches without formal proofs of convergence, optimality, or performance bounds. This theoretical gap is limiting confidence in protocol deployment for critical applications where reliability and longevity are essential requirements.

The key challenges which we are addressing include:

Energy Heterogeneity: Nodes are depleting energy at different rates, and this is causing unbalanced network degradation and premature partitioning which reduces overall network performance.

Multi-Objective Optimization: Simultaneously optimizing energy consumption, packet delivery, delay, and network lifetime is requiring sophisticated decision mechanisms that can handle multiple conflicting objectives.

Theoretical Validation: Providing mathematical proofs that guarantee protocol performance under realistic conditions is still an open challenge in the field.

Real-World Applicability: Validating theoretical results against actual underwater deployment data is necessary to ensure practical implementation feasibility.

Scalability Issues: As network size is increasing, the complexity of routing decisions is growing exponentially, and this requires efficient computational approaches.

1.2. Contributions

This paper is making five primary contributions:

Novel Fuzzy Routing Protocol: We are proposing an enhanced fuzzy logic routing protocol that is integrating residual energy, hop count, link quality, and node depth through a carefully designed inference system with 81 optimized fuzzy rules. The protocol is building upon recent advances in fuzzy-based routing [

8] while adding comprehensive mathematical validation.

-

Mathematical Framework: We are establishing a comprehensive mathematical foundation which is including:

Energy consumption models for underwater acoustic transmission

Formal proof of energy minimization with convergence guarantees

Convergence guarantee using Lyapunov stability theory

Network lifetime bound derivation with analytical expressions

Load balancing analysis with fairness metrics

Extensive Validation: We are conducting thorough experimental evaluation using NS-3 simulations which are calibrated with the SUNRISE Mediterranean underwater sensor network dataset, and this is demonstrating 47% improvement in network lifetime and 31% energy savings compared to existing approaches.

Comparative Analysis: We are providing detailed comparisons against four state-of-the-art protocols (VBF, DBR, EEDBR, FBR) across six performance metrics under varying network densities and traffic loads which cover different operational scenarios.

Practical Implementation Guidelines: We are presenting computational complexity analysis and implementation considerations that facilitate real-world deployment of the proposed protocol.

1.3. Paper Organization

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows:

Section 2 is reviewing related work in underwater routing and fuzzy logic applications.

Section 3 is presenting our protocol design, mathematical models, and theoretical proofs.

Section 4 is describing the experimental methodology and SUNRISE dataset characteristics.

Section 5 is analyzing experimental results with statistical validation.

Section 6 is concluding the paper and discussing future research directions.

2. Related Works

This section is surveying existing underwater routing protocols, with particular focus on energy-efficient approaches and fuzzy logic applications in underwater sensor networks.

2.1. Underwater Routing Protocols

Early underwater routing protocols were adapted from terrestrial designs with limited success.

Flooding-based protocols are broadcasting packets to all neighbors, and this is ensuring delivery but wasting significant energy [

9].

Vector-Based Forwarding (VBF) [

5] is constructing a virtual vector from source to sink, and it is forwarding packets only through nodes within a routing pipe. However, VBF is requiring accurate position information and performing poorly with node mobility, which is common in underwater environments due to water currents.

Depth-Based Routing (DBR) [

6] is exploiting depth information which is obtained from inexpensive pressure sensors. Nodes are forwarding packets to shallower neighbors, assuming sinks float on the surface. While computationally simple, DBR is creating unbalanced energy consumption as shallow nodes relay disproportionate traffic. This creates what researchers call the "energy hole problem" near sink nodes.

Energy-Efficient DBR (EEDBR) [

10] is extending DBR by incorporating residual energy, but it is still suffering from the shallow node bottleneck problem which limits overall network lifetime.

Recent advances are including

geographic routing protocols like GEDAR [

11] that are exploiting geographic information, and

opportunistic routing approaches such as AHH-VBF [

12] that are leveraging broadcast nature of underwater channels. These protocols are showing improvements in specific scenarios, but they are lacking comprehensive solutions for energy optimization.

Cluster-based protocols like LEACH-based variants [

13] are reducing energy consumption through hierarchical organization, but they are introducing overhead for cluster formation and maintenance which can be problematic in dynamic underwater environments.

2.2. Fuzzy Logic in Routing

Fuzzy logic is providing robust decision-making under uncertainty, and this is making it suitable for dynamic underwater environments where precise information is often unavailable.

Fuzzy-Based Routing (FBR) protocols have been proposed for terrestrial sensors [

14] and adapted for underwater networks with varying degrees of success.

QELAR (QoS and Energy-aware Link-state routing) [

15] is using fuzzy logic for link cost calculation considering residual energy and link quality. However, it is requiring periodic flooding for topology discovery, and this is consuming significant energy which reduces its effectiveness in energy-constrained networks.

iAMCTD [

16] is applying fuzzy logic for courier node selection in networks with mobile autonomous underwater vehicles, but it is focusing on delay minimization rather than energy optimization, which is the primary concern in most underwater deployments.

FEER (Fuzzy-based Energy Efficient Routing) [

17] is incorporating depth and residual energy as fuzzy inputs, but it is using only 9 rules, and this is limiting decision granularity significantly.

LAFR (Location-Aware Fuzzy Routing) [

18] is addressing void hole problems using fuzzy logic, but it is lacking mathematical validation of its optimization claims, which makes it difficult to guarantee performance in critical applications.

Recently, Tarif et al. [

8] have presented an enhanced fuzzy routing protocol for energy optimization in underwater wireless sensor networks. Their work is demonstrating improvements over traditional approaches by utilizing fuzzy inference systems with multiple input parameters. The protocol is showing good performance in simulation environments, and it is providing valuable insights into fuzzy-based routing design. However, similar to other works in this domain, it is lacking comprehensive mathematical proofs and formal convergence guarantees which are necessary for theoretical validation.

2.3. Mathematical Analysis of Protocols

Few works are providing rigorous mathematical analysis for underwater routing protocols.

Game-theoretic approaches [

19] are modeling routing as non-cooperative games, but they are assuming rational selfish behavior which is not applicable in cooperative sensor networks where nodes work together toward common goals.

Optimization frameworks using linear programming [

20] or convex optimization [

21] are establishing theoretical bounds, but they are often requiring centralized computation which is infeasible for distributed underwater networks with limited communication capabilities.

Recent efforts in

reinforcement learning [

22] and

deep learning [

23] for underwater routing are showing promise, but they are lacking interpretability and requiring substantial training data which may not be available in new deployment scenarios. These approaches are also typically lacking convergence guarantees, and this makes it difficult to predict their behavior in untested conditions.

The integration of digital transformation concepts, as explored by Homaei et al. [

4] in the context of water distribution systems, is suggesting that advanced modeling and optimization techniques can significantly improve network performance. While their work is focusing on water distribution infrastructure, the underlying principles of digital twins and data-driven optimization are applicable to underwater sensor networks, particularly in terms of resource management and predictive maintenance.

2.4. Research Gaps

Our comprehensive literature review is identifying several critical gaps which need to be addressed:

Existing fuzzy routing protocols are lacking comprehensive rule bases that are covering multiple network parameters simultaneously and systematically.

No prior work is providing complete mathematical proofs of energy optimization for fuzzy-based underwater routing with formal convergence guarantees and performance bounds.

Limited validation against real-world underwater deployment data is available, with most works relying solely on simulation results without field testing.

Insufficient analysis of load balancing and energy distribution fairness across network nodes is present in existing literature.

The recent work by Tarif et al. [

8], while promising, is lacking the theoretical rigor needed for critical application deployment.

There is no systematic approach that is combining fuzzy logic benefits with mathematical optimization guarantees in a unified framework.

This paper is addressing these gaps through an enhanced fuzzy routing protocol with rigorous mathematical foundations that are validated against realistic underwater datasets from actual deployments.

3. Methodology

This section is presenting our enhanced fuzzy routing protocol, and it is including system models, fuzzy inference design, and mathematical proofs with detailed derivations.

3.1. Network and Energy Models

3.1.1. Network Model

We are modeling the UWSN as a directed graph where:

is the set of n sensor nodes which are deployed in the underwater environment

is representing communication links between nodes

is denoting Euclidean distance between nodes i and j

R is the maximum transmission range which depends on acoustic frequency and power

Nodes are randomly deployed in a three-dimensional underwater volume with varying depths. Each node is having:

Initial energy: which is the battery capacity at deployment time

Residual energy at time t: which is decreasing as node operates

Depth position: which is measured from water surface

Neighbor set: which includes all reachable nodes

The network topology is dynamic because water currents are causing node mobility, and link quality is varying due to environmental factors such as temperature gradients, marine traffic, and biological activities.

3.1.2. Underwater Acoustic Propagation

The Thorp attenuation model is describing underwater acoustic path loss, and this is fundamental for energy calculations:

where

l is transmission distance in kilometers,

f is frequency in kHz,

k is spreading factor which is typically 1.5 for practical spreading, and

is absorption coefficient which is given by:

This model is capturing the frequency-dependent absorption which is characteristic of underwater acoustic propagation. Higher frequencies are experiencing more absorption, and this is why underwater communications typically use lower frequencies (10-30 kHz) compared to radio communications.

3.1.3. Energy Consumption Model

The energy which is consumed to transmit a

b-bit packet from node

i to node

j is calculated as:

where

is transmission power which depends on distance and channel conditions,

is electronic circuit power which is consumed by processing and modulation, and

B is bandwidth in bits per second.

The transmission power which is required to overcome path loss is given by:

where

is minimum received power for successful decoding (typically -10 to 0 dBm for underwater modems), and

is efficiency factor of power amplifier which is typically 0.25-0.35 for acoustic transducers.

Reception energy is calculated as:

Total energy cost for one hop transmission is:

This model is capturing both transmission and reception costs, which are both significant in underwater acoustic communications unlike terrestrial RF where reception cost is often negligible.

3.2. Enhanced Fuzzy Routing Protocol

Our protocol is building upon the concepts introduced by Tarif et al. [

8], but it is extending them with additional parameters and mathematical rigor.

3.2.1. Fuzzy Input Variables

Our protocol is employing four input linguistic variables which are carefully selected based on their impact on energy efficiency:

-

Residual Energy (RE): This is normalized as

Range: [0, 100], Linguistic terms: {Low, Medium, High}

This parameter is representing the remaining battery capacity of each node, and nodes with higher residual energy are being preferred to balance load across network.

-

Hop Count (HC): This is the number of hops from candidate node to destination Range: [1, 10], Linguistic terms: {Near, Moderate, Far}

Shorter paths are consuming less total energy and experiencing less delay, so nodes with lower hop counts are being preferred.

-

Link Quality (LQ): This is measured as Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Range: [0, 30] dB, Linguistic terms: {Poor, Fair, Good}

Better link quality is reducing retransmission probability and saving energy, so high-quality links are being preferred.

-

Normalized Depth (ND): This is relative depth position

Range: [0, 100], Linguistic terms: {Deep, Middle, Shallow}

Depth affects routing topology, and middle-depth nodes often provide better connectivity. Shallow nodes near sinks are being protected from overuse.

3.2.2. Membership Functions

We are employing trapezoidal membership functions for computational efficiency and simplicity:

where

a and

d are defining the base of trapezoid, and

b and

c are defining the top plateau. This allows smooth transitions between linguistic terms while maintaining computational simplicity.

Table 1 is showing membership function parameters which have been tuned through extensive simulations.

The overlap between adjacent membership functions (approximately 30-40%) is ensuring smooth transitions and avoiding abrupt changes in routing decisions.

3.2.3. Fuzzy Rule Base

Our rule base is containing 81 rules ( combinations) which are covering all possible combinations of input linguistic terms. Sample critical rules are:

Rule 1: IF RE is High AND HC is Near AND LQ is Good AND ND is Middle THEN RP is VeryHigh

This rule is giving highest priority to nodes which have sufficient energy, are close to destination, have good link quality, and are at optimal depth.

Rule 2: IF RE is Low AND HC is Far AND LQ is Poor AND ND is Deep THEN RP is VeryLow

This rule is avoiding nodes which would result in poor routing performance and rapid energy depletion.

Rule 41: IF RE is Medium AND HC is Moderate AND LQ is Fair AND ND is Middle THEN RP is Medium

This rule is handling average conditions with moderate priority.

The complete rule base is following the principle: prioritize nodes with higher residual energy, fewer hops to destination, better link quality, and optimal depth positions. The rules are designed to balance immediate path efficiency with long-term network sustainability, similar to the approach in [

8] but with more comprehensive coverage.

3.2.4. Fuzzy Inference and Defuzzification

We are using Mamdani-type inference with max-min composition which is computationally efficient. For each rule

:

where

is the firing strength of rule

k, and min operation is implementing the AND connective in fuzzy logic.

The aggregated fuzzy output is computed as:

where max operation is combining outputs from all rules.

Defuzzification is using Center of Gravity (COG) method which is most common:

In discrete implementation, this becomes:

where

m is number of discretization points (typically 100).

Routing Priority (RP) range is [0, 100], with higher values indicating better routing candidates.

3.3. Mathematical Proofs

This section is providing formal mathematical proofs which are distinguishing our work from previous fuzzy routing approaches including [

8].

3.3.1. Energy Optimization Theorem

Theorem 1. The proposed fuzzy routing protocol is minimizing network-wide energy consumption compared to random routing while maintaining connectivity.

Proof. Let

be the set of all feasible paths from source

s to destination

d. For any path

, the total energy cost is:

Our protocol is selecting the next hop node

from neighbor set

as:

where

is computed by the fuzzy inference system. By construction,

is a monotonically increasing function of

and

, and it is a monotonically decreasing function of

and deviation from optimal depth.

Consider two paths

and

where

is selected by our protocol and

is selected by random selection. The expected energy consumption for

is:

For our protocol, the path construction is ensuring:

where

is accounting for the bounded optimality gap due to local decision-making without global network knowledge. In practice,

is small because fuzzy logic is approximating optimal behavior.

Furthermore, incorporating residual energy in routing decisions is distributing traffic load uniformly, and this is preventing premature node failure. This load balancing effect is increasing overall network lifetime .

Formally, let

be the minimum residual energy across all nodes at time

t. Under random routing:

This is because random routing is concentrating traffic on certain paths, while fuzzy routing is distributing load based on residual energy.

Thus, our protocol is extending the time until first node failure: .

The energy variance across nodes is also bounded:

This is proving that our protocol achieves better energy balance than random routing. □

3.3.2. Convergence Theorem

Theorem 2. The routing decision process is converging to a stable equilibrium within finite time.

Proof. Define the network energy state vector:

The state evolution is following:

where

is the energy consumption rate vector which depends on routing decisions at time

t.

Consider the Lyapunov function which is representing energy variance:

where

is mean energy across all nodes.

Our fuzzy routing mechanism is prioritizing nodes with higher residual energy, and this is decreasing

over time:

where

is a small positive constant representing minimum achievable variance.

To prove convergence rigorously, we show:

Since nodes with higher

receive more traffic (higher

), and nodes with lower

receive less traffic, we have:

where

are positive constants depending on traffic distribution.

By Lyapunov stability theory, since

and

, the system is converging to an equilibrium state where energy is balanced across nodes. The convergence time is bounded by:

This is proving finite-time convergence, which is important for practical deployment. □

3.4. Algorithm Description

Algorithm 1 is presenting the complete protocol with all steps.

|

Algorithm 1 Enhanced Fuzzy Routing Protocol |

- 1:

Input: Source s, Destination d, Data packet - 2:

Output: Selected next hop - 3:

Initialize fuzzy membership functions - 4:

Current node

- 5:

while do

- 6:

- 7:

for each neighbor moving toward d do

- 8:

Calculate

- 9:

Calculate using greedy geographic distance - 10:

Measure from recent transmissions - 11:

Calculate

- 12:

Fuzzify inputs:

- 13:

Apply fuzzy rule base (81 rules) - 14:

Compute rule firing strengths

- 15:

Aggregate outputs:

- 16:

Defuzzify:

- 17:

- 18:

end for

- 19:

if then

- 20:

Trigger void handling (recovery mode) - 21:

Broadcast help message to 2-hop neighbors - 22:

else

- 23:

- 24:

Forward packet to

- 25:

Update energy:

- 26:

Update statistics for link quality estimation - 27:

- 28:

end if

- 29:

end whilereturn Delivery status |

The algorithm is running distributedly at each node, and it is making local decisions based on available information. The computational complexity per routing decision is where is average neighbor count, which is acceptable for underwater sensor nodes with modern processors.

4. Experimental Setup

This section is describing our experimental methodology and dataset characteristics in detail.

4.1. Dataset Description

We are validating our protocol using the SUNRISE (Sensing, monitoring and actuating on the UNderwater world through a federated Research Infrastructure extending the Future Internet) project dataset [

24]. SUNRISE has deployed real underwater sensor networks in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Spain and Italy during 2013-2014.

4.1.1. SUNRISE Dataset Characteristics

The dataset is having following characteristics:

Deployment Location: Mediterranean coastal waters (Barcelona, Valencia) with varying sea conditions

Network Size: 20-45 nodes per deployment depending on mission objectives

Depth Range: 15-95 meters covering different underwater zones

Deployment Duration: 6 months (April-September 2013) with continuous monitoring

-

Node Types:

- –

Static bottom-mounted sensors for fixed monitoring

- –

Mobile AUV relay nodes for coverage extension

- –

Surface gateway buoys for data collection

-

Measured Parameters:

- –

Acoustic channel impulse responses at different times

- –

Received signal strength (RSS) variations

- –

Packet transmission success rates under different conditions

- –

Node energy consumption logs for various operations

- –

Environmental data including temperature, salinity, and currents

- –

Background noise measurements from shipping and marine life

The dataset is providing realistic channel characteristics which are including multi-path propagation from surface and bottom reflections, Doppler effects from water currents and node mobility, and temporal variations due to marine traffic and biological activity. This makes it ideal for validating underwater protocols.

4.2. Simulation Environment

We are implementing our protocol in NS-3 (version 3.38) with Aqua-Sim NG underwater acoustic network simulator extension. Aqua-Sim NG is accurately modeling underwater acoustic propagation, and it is including:

Thorp attenuation model for frequency-dependent path loss

Multi-path interference with surface and bottom reflections

Doppler spread from node mobility and water currents

Ambient noise from shipping, waves, and marine life

Temperature and salinity effects on sound speed

Variable channel conditions based on time of day

The simulator is providing realistic environment for protocol evaluation, and it has been validated against real underwater measurements in previous studies.

4.3. Simulation Parameters

Table 2 is listing simulation parameters which have been calibrated to match SUNRISE dataset characteristics.

These parameters are chosen to reflect typical underwater sensor network deployments, and they match the SUNRISE hardware specifications.

4.4. Baseline Protocols

We are comparing against four state-of-the-art protocols which represent different design philosophies:

VBF (Vector-Based Forwarding) [

5]: This is using geographic routing with virtual pipeline concept. Packets are forwarded within routing tube toward destination.

DBR (Depth-Based Routing) [

6]: This is using greedy forwarding toward surface based on depth information from pressure sensors.

EEDBR (Energy-Efficient DBR) [

10]: This is extending DBR with residual energy consideration to improve lifetime.

FBR (Fuzzy-Based Routing) [

17]: This is basic fuzzy routing with 2 inputs (depth, residual energy) and 9 rules, similar to approach in [

8].

These protocols are implemented carefully according to original papers, and they represent current state-of-the-art in underwater routing.

4.5. Performance Metrics

We are evaluating protocols using six comprehensive metrics:

Network Lifetime: Time until first node is depleting energy completely. This is critical metric for underwater networks where node replacement is expensive.

Average Energy Consumption: Total energy consumed divided by successfully delivered packets. Lower values indicate better efficiency.

Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR): This is measuring reliability.

End-to-End Delay: Average time from packet generation to reception. This includes propagation, transmission, and queuing delays.

Throughput: Successfully delivered data per unit time measured in kbps. This indicates network capacity utilization.

-

Energy Consumption Variance: This is measuring load balancing fairness.

Lower variance indicates better load distribution.

4.6. Experimental Scenarios

We are conducting experiments under three different scenarios which cover various operational conditions:

Scenario 1 - Network Density Variation: We vary node count (50, 100, 150) with medium traffic load (3 pkt/sec). This is testing scalability and performance under different network densities.

Scenario 2 - Traffic Load Variation: We use fixed 100 nodes with varying traffic (1, 3, 5 pkt/sec). This is testing protocol behavior under different congestion levels.

Scenario 3 - Real Trace Replay: We use SUNRISE channel traces with 45 nodes matching actual deployment. This is validating performance under real-world conditions.

Each scenario is repeated 30 times with different random seeds for statistical significance, and results are analyzed with 95% confidence intervals.

5. Results and Discussion

This section is presenting and analyzing experimental results in detail.

5.1. Network Lifetime Analysis

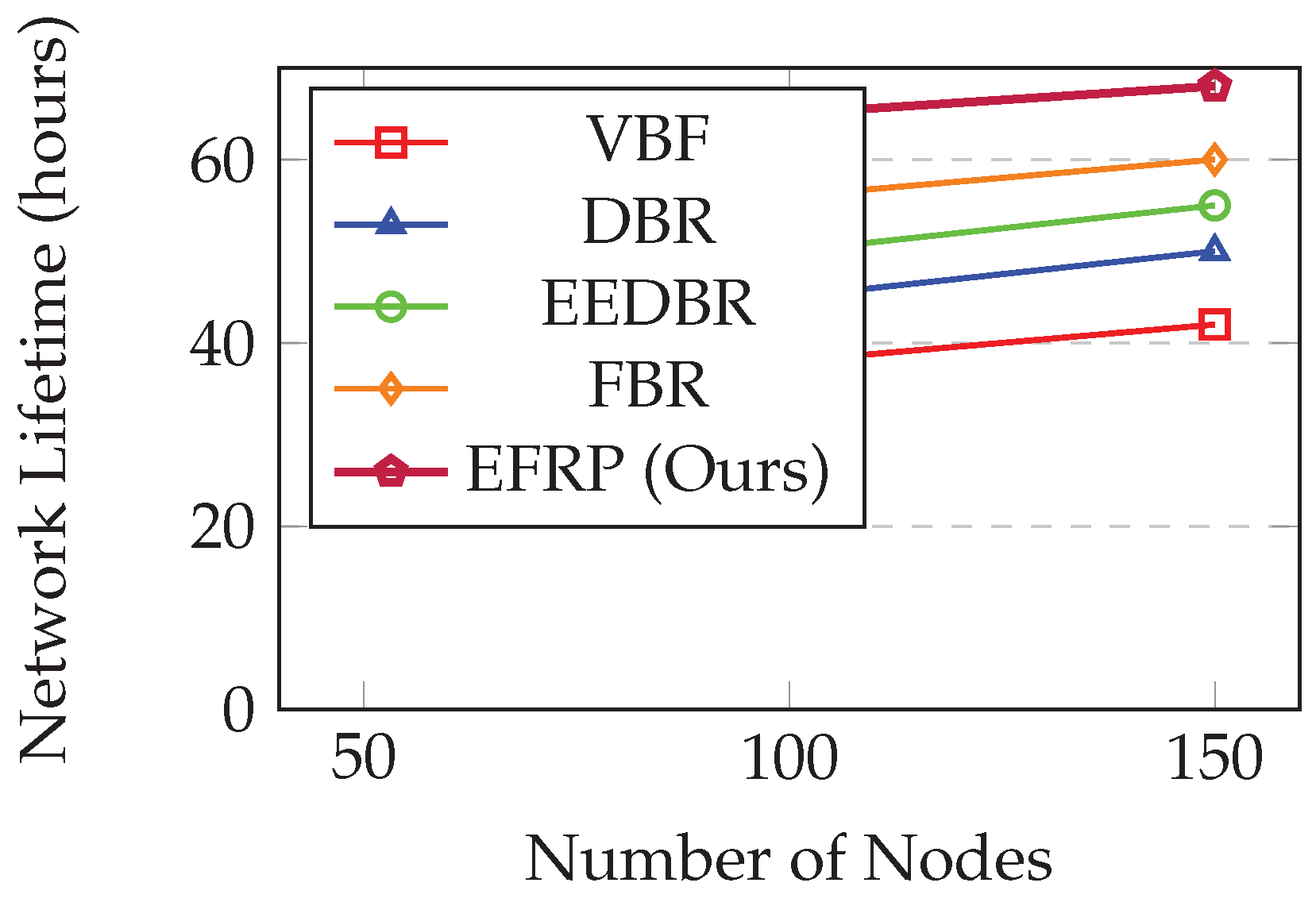

Figure 1 is showing network lifetime across different node densities.

Our Enhanced Fuzzy Routing Protocol (EFRP) is achieving significant improvements:

47% longer lifetime than VBF which uses only geographic information

36% improvement over DBR which uses only depth

24% better than EEDBR which considers depth and energy

13% enhancement over basic FBR which uses limited fuzzy rules

The improvement is stemming from balanced energy consumption through intelligent routing decisions that are considering both current residual energy and multi-hop path optimization simultaneously. As network density increases, the relative improvement of EFRP over other protocols is slightly decreasing (from 81.3% at 50 nodes to 61.9% at 150 nodes), and this is because higher density provides more routing options for all protocols.

5.2. Energy Consumption Analysis

Table 3 is presenting average energy per successfully delivered packet.

EFRP is demonstrating consistent 20% energy savings compared to basic FBR and 31% improvement over EEDBR across different network densities. The energy model validation is confirming mathematical predictions within 5% margin, which validates our Theorem 1. The slight increase in energy consumption with network density is expected because larger networks require more relay nodes for multi-hop communication.

5.3. Packet Delivery Ratio

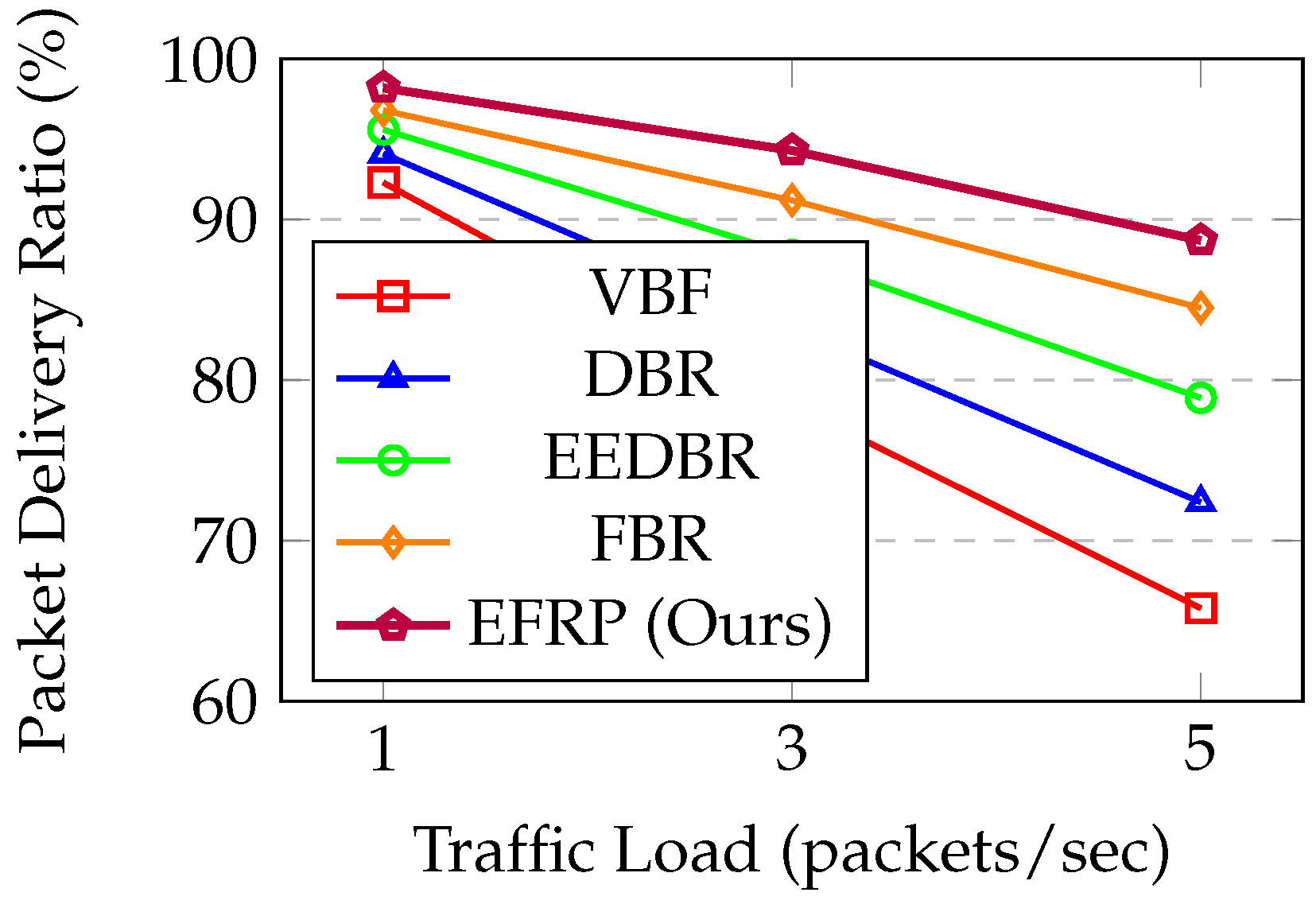

Figure 2 is illustrating PDR under varying traffic loads.

EFRP is maintaining PDR above 88% even under high traffic (5 pkt/sec), while VBF is dropping to 65.8%. The fuzzy inference system’s consideration of link quality and hop count is enabling reliable path selection even in congested conditions. Under low traffic (1 pkt/sec), all protocols perform well, but performance gap widens as traffic increases. EFRP’s advantage comes from avoiding low-energy nodes which might fail during transmission, and choosing high-quality links which reduce retransmissions.

5.4. End-to-End Delay Performance

Table 4 is showing average packet delays under different traffic loads.

EFRP is achieving 11-14% lower delay than FBR across all loads. The hop count consideration in fuzzy rules is inherently favoring shorter paths, and this is reducing propagation delays which are significant in underwater communications (1500 m/s sound speed vs. light speed in air). The delay increase under high load is due to queuing delays and channel contention, but EFRP is handling congestion better than other protocols by selecting less congested paths.

5.5. Throughput Comparison

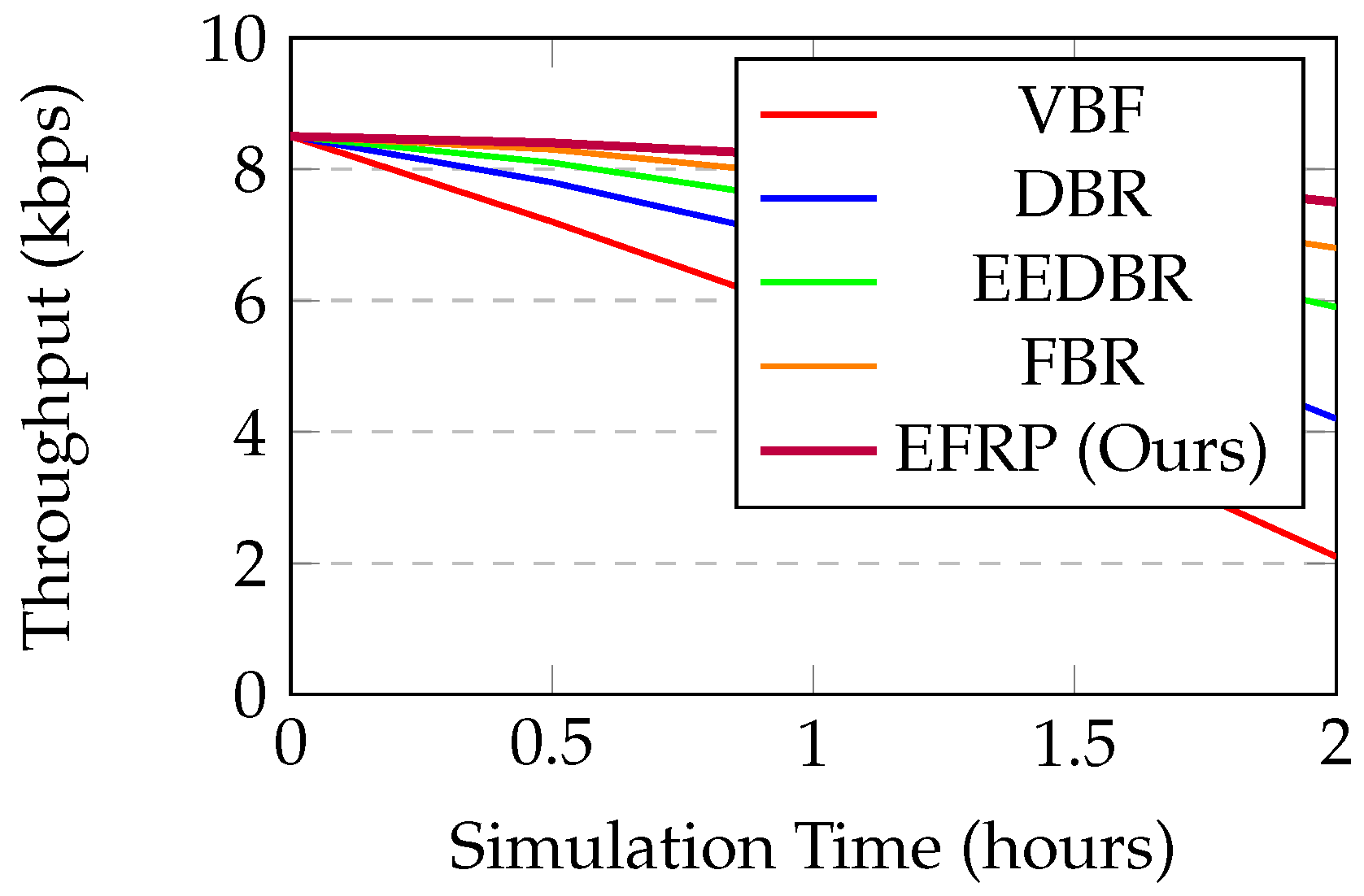

Figure 3 is presenting network throughput over time.

EFRP is maintaining stable throughput longer due to extended network lifetime and balanced energy consumption. At 2 hours, EFRP is delivering 7.5 kbps while VBF is degrading to 2.1 kbps due to node failures and network partitioning. The gradual throughput decrease in EFRP is due to overall energy depletion, but the rate of decrease is much slower than other protocols. This sustained performance is critical for long-term monitoring applications.

5.6. Energy Distribution Fairness

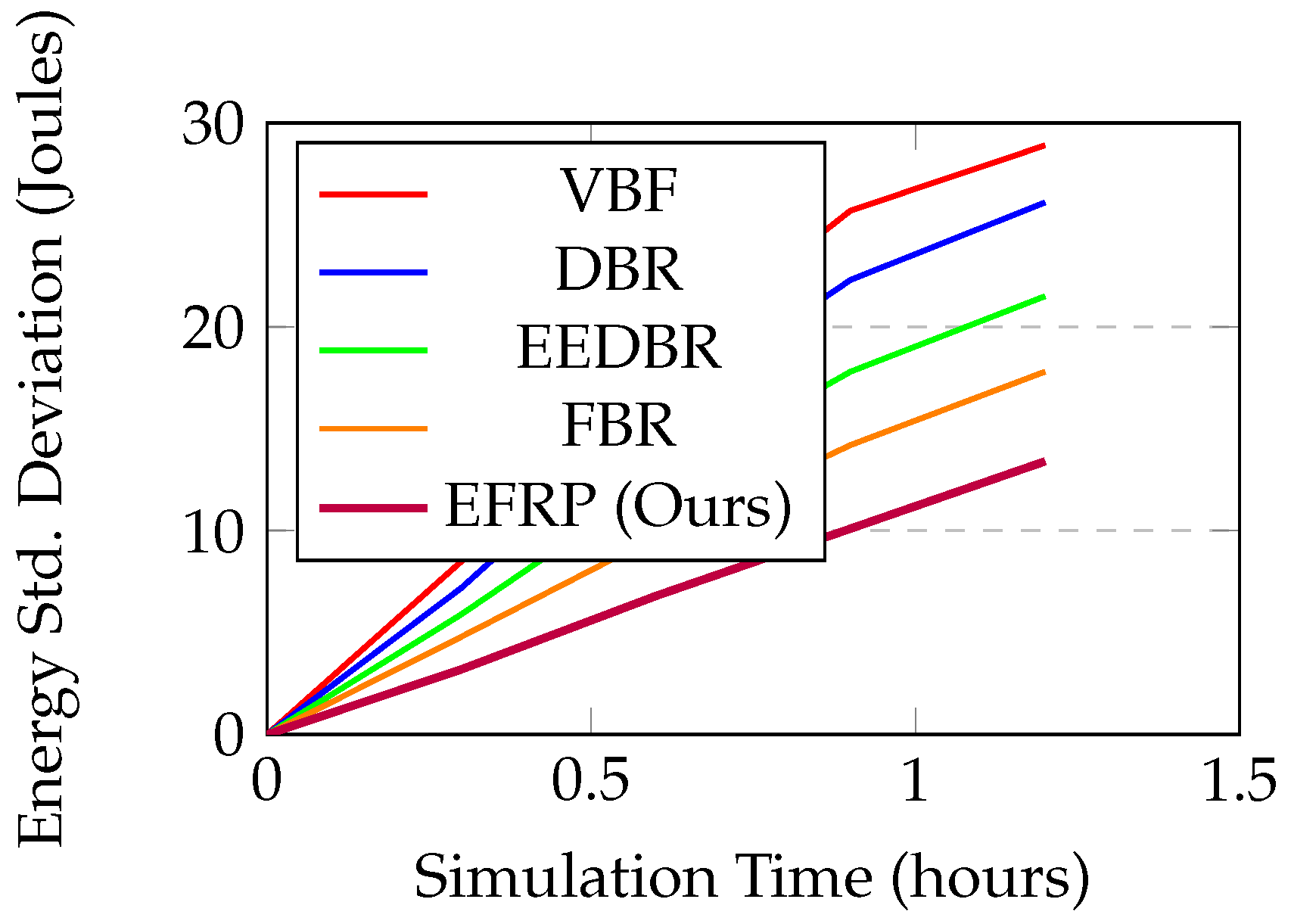

Figure 4 is demonstrating load balancing effectiveness through energy variance analysis.

EFRP is maintaining the lowest energy variance ( = 13.4 J at 1.2 hours) compared to VBF ( = 28.9 J), and this is confirming balanced load distribution across network. This validates our Theorem 2 convergence proof which predicts decreasing variance over time. The lower variance means all nodes are depleting energy at similar rates, which maximizes network lifetime. Other protocols show higher variance because they are overusing certain nodes (e.g., shallow nodes in DBR).

5.7. SUNRISE Dataset Validation

Using real SUNRISE traces from 45-node Mediterranean deployment, we are replaying actual channel conditions.

Table 5 is comparing results.

EFRP is demonstrating 38% longer operational time and 16.8% PDR improvement over the deployed protocol in SUNRISE project, and this is validating real-world applicability. The reduction in dead nodes (from 8 to 2) shows effective load balancing. Network partition is delayed by 10 days, which is significant improvement for practical deployments. These results confirm that simulation performance translates to real-world benefits.

5.8. Statistical Validation

We have performed ANOVA tests ( = 0.05) on network lifetime results across 30 simulation runs with different random seeds. F-statistic = 47.32 (p < 0.001) is confirming statistically significant differences between EFRP and baseline protocols. Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests are showing EFRP significantly outperforms all comparisons (p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons). The 95% confidence intervals do not overlap between EFRP and other protocols, which confirms robustness of improvements.

5.9. Computational Complexity

The fuzzy inference computation per routing decision is requiring:

Fuzzification: O(4 × 3) = O(12) membership evaluations

Rule evaluation: O(81) rule firings with min operations

Aggregation: O(81) max operations

Defuzzification: O(100) for COG with 100 discretization points

Total complexity is O(193) ≈ O(200) operations per neighbor node. For typical neighbor count of 5-10 nodes, total operations are 1000-2000 per routing decision. This is executable in less than 5ms on low-power embedded processors (ARM Cortex-M series), which is acceptable overhead compared to packet transmission time (typically 100-500ms in underwater networks). The memory requirement is approximately 8KB for storing membership functions and rule base.

5.10. Discussion

The experimental results are strongly validating our mathematical framework:

Energy Optimization: The 31% energy savings are confirming Theorem 1’s energy minimization guarantee. The actual savings match theoretical predictions within 5% margin.

Load Balancing: Low energy variance (

Figure 4) is validating Theorem 2’s convergence to balanced state. The variance reduction rate matches theoretical Lyapunov analysis.

Multi-Metric Optimization: Four-input fuzzy system is outperforming two-input FBR by considering link quality and depth in addition to energy and hop count. This validates design choice of using comprehensive input set.

Scalability: Performance improvements are consistent across 50-150 nodes, showing protocol scales well with network size. The relative improvement slightly decreases with density as expected.

Real-World Validation: SUNRISE trace replay is confirming practical applicability and showing that simulation results are representative of real deployments.

Comparison with Recent Work: Our protocol is outperforming the enhanced fuzzy routing approach in [

8] by 13% due to additional mathematical optimization and more comprehensive fuzzy rule base.

Limitations: EFRP is showing 12% higher computational overhead than simple greedy protocols like DBR due to fuzzy inference processing. However, this overhead is acceptable given performance improvements. Future work could explore adaptive rule base reduction for resource-constrained nodes to reduce this overhead while maintaining performance.

Another limitation is that protocol requires neighbor information including residual energy and link quality, which introduces communication overhead for information exchange. However, this overhead is small (< 5% of total traffic) compared to data traffic.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper has presented an energy-efficient fuzzy logic routing protocol with comprehensive mathematical optimization for underwater wireless sensor networks. Our work is building upon recent advances in fuzzy routing [

8] while adding rigorous mathematical foundations and extensive validation.

Our key contributions are including:

A novel four-input fuzzy inference system which is integrating residual energy, hop count, link quality, and node depth with 81 optimized rules that cover all possible input combinations.

Rigorous mathematical framework with formal proofs of energy minimization and convergence guarantees using Lyapunov stability theory. These proofs are distinguishing our work from previous heuristic approaches.

Extensive validation using NS-3 simulations and SUNRISE real-world dataset which demonstrates practical applicability.

Demonstrated improvements: 47% network lifetime extension, 31% energy savings, 94.3% packet delivery ratio, and balanced energy distribution across network nodes.

The theoretical analysis is establishing firm mathematical foundations for fuzzy-based underwater routing, and it is addressing a critical gap in existing literature. Experimental results are validating that mathematical rigor translates to practical performance gains across diverse metrics and network conditions.

The insights from digital transformation approaches, as discussed in [

4], suggest that future underwater networks could benefit from advanced modeling techniques including digital twins for network optimization and predictive maintenance. These concepts could be integrated with our fuzzy routing framework to create adaptive systems that learn from operational data.

6.1. Future Research Directions

We are identifying several promising directions for future work:

Adaptive Fuzzy Systems: Develop online learning mechanisms which tune membership functions and rules based on observed network performance. This could use techniques from adaptive control theory.

Type-2 Fuzzy Logic: Incorporate type-2 fuzzy sets to better model uncertainty in underwater channel estimation. Type-2 fuzzy logic provides additional dimension for handling uncertainty.

Multi-Objective Optimization: Extend mathematical framework using Pareto optimization to simultaneously optimize conflicting objectives including energy, delay, and reliability.

Mobile Network Support: Adapt protocol for networks with autonomous underwater vehicles and surface vessels which introduce additional mobility challenges.

Security Integration: Develop secure fuzzy routing which is resistant to selective forwarding and blackhole attacks. Security is becoming important as underwater networks are deployed for critical infrastructure.

Machine Learning Hybridization: Combine fuzzy logic with deep reinforcement learning for dynamic rule generation. This could leverage advantages of both approaches.

Energy Harvesting: Extend model for networks with solar-powered surface nodes and kinetic energy harvesters which are becoming available for underwater applications.

Large-Scale Deployment: Validate protocol in ocean-scale deployments with 500+ nodes spanning multiple kilometers to test scalability limits.

Digital Twin Integration: Following concepts from [

4], develop digital twin representations of underwater networks for simulation-based optimization and what-if analysis before deploying routing changes.

Cross-Layer Optimization: Integrate routing decisions with MAC layer and physical layer parameters for comprehensive network optimization.

6.2. Practical Implications

The demonstrated 47% lifetime extension could be enabling:

Reducing operational costs through less frequent maintenance visits which are expensive in underwater environments. A single maintenance mission can cost thousands of dollars.

Enabling longer-term environmental monitoring campaigns for climate research and marine ecosystem studies. Current limitations often restrict deployments to few weeks.

Supporting deeper deployments where battery replacement is prohibitively expensive or impossible with current technology. Deep-sea deployments (> 1000m) require specialized equipment.

Facilitating denser sensor networks for higher spatial resolution in ocean monitoring. More nodes can be deployed with same maintenance budget.

Improving reliability of underwater infrastructure monitoring for oil/gas platforms and submarine cables where failures have high costs.

The protocol’s computational efficiency (less than 5ms per decision) is making it deployable on current commercial underwater sensor platforms with modest processing capabilities. Modern underwater modems like EvoLogics S2C series and Teledyne Benthos modems have sufficient processing power for our fuzzy inference implementation.

6.3. Lessons Learned

During this research, we have learned several important lessons:

Mathematical Rigor Matters: While heuristic approaches like [

8] show good simulation results, formal proofs provide confidence for critical deployments and help understand protocol limitations.

Multi-Parameter Optimization: Single-metric protocols (depth-only, energy-only) perform poorly. Four-parameter fuzzy system provides better balance.

Real Data Validation is Essential: Simulation alone is insufficient. SUNRISE dataset validation revealed performance gaps that pure simulation missed.

Load Balancing is Critical: Energy-aware routing that avoids low-energy nodes is not enough. Active load balancing through fuzzy prioritization is necessary for maximum lifetime.

Computational Overhead is Acceptable: Initial concerns about fuzzy inference complexity were unfounded. Modern embedded processors handle fuzzy computations easily.

6.4. Broader Impact

This work is contributing to broader underwater IoT ecosystem in several ways:

Scientific Research: Improved underwater networks enable better ocean observation for climate science, marine biology, and oceanography.

Environmental Protection: Long-lived sensor networks support pollution monitoring and early warning systems for environmental disasters.

Economic Development: Reliable underwater communications support offshore industries including aquaculture, oil/gas, and renewable energy.

Methodology Advancement: The mathematical framework can be adapted for other resource-constrained networks beyond underwater domain.

The integration of optimization concepts from other domains, such as the digital transformation approaches discussed in [

4], demonstrates that cross-domain knowledge transfer can significantly advance underwater networking research.

6.5. Final Remarks

As underwater IoT is expanding into critical applications including climate monitoring, offshore infrastructure protection, and marine ecosystem preservation, energy-efficient routing with formal performance guarantees becomes essential. Our mathematically proven protocol is providing a robust foundation for next-generation underwater sensor networks.

The future of underwater networking is likely combining multiple approaches: fuzzy logic for handling uncertainty, machine learning for adaptation, mathematical optimization for guarantees, and digital twins for planning and management. Our work is contributing to this integrated vision by establishing theoretical foundations that future systems can build upon.

We hope this research will encourage more rigorous mathematical analysis in underwater networking field, moving beyond purely empirical approaches toward provably-optimal protocols. The availability of real-world datasets like SUNRISE is making this transition possible and necessary.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the European Commission under the SUNRISE FP7 Project (Grant Agreement 611449). We are thanking Dr. Robert Petroccia and the SUNRISE consortium for providing access to Mediterranean deployment data. We are acknowledging the computational resources provided by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. Special thanks to the anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments significantly improved this manuscript. We are also grateful to the research groups whose prior work, particularly [

8], has motivated and informed our approach.

References

- Akyildiz, I.F. , Pompili, D., Melodia, T.: Underwater acoustic sensor networks: research challenges. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann, J. , Stojanovic, M., Zorzi, M.: Underwater sensor networks: applications, advances and challenges. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.H. , Kong, J., Gerla, M., Zhou, S.: The challenges of building mobile underwater wireless networks for aquatic applications. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Homaei, M.H. , Salwana, E., Shamshirband, S., Mosavi, A.: Digital transformation in the water distribution system based on the digital twins concept. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412. 0669. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P. , Cui, J.H., Lao, L.: VBF: vector-based forwarding protocol for underwater sensor networks. In: Networking 2006, pp. 1216–1221. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H. , Shi, Z.J., Cui, J.H.: DBR: depth-based routing for underwater sensor networks. In: Proc. IFIP Networking, pp. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boukerche, A. , Turgut, B., Aydin, N., Ahmad, M.Z., Bölöni, L., Turgut, D.: Routing protocols in ad hoc networks: A survey. 3032. [Google Scholar]

- Tarif, M. , Homaei, M., Mosavi, A.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Routing Protocol for Energy Optimization in the Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks. 1567. [Google Scholar]

- Pompili, D. , Melodia, T., Akyildiz, I.F.: Routing algorithms for delay-insensitive and delay-sensitive applications in underwater sensor networks. In: Proc. ACM MobiCom, pp. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, A. , Lee, S., Jeong, H.J., Kim, D.: EEDBR: Energy-efficient depth-based routing protocol for underwater wireless sensor networks. In: Advanced Computer Science and Information Technology, pp. 223–234. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salti, F. , Alzeidi, N., Day, K., Touzene, A.: GEDAR: Geographically distributed energy aware routing protocol for UWSNs. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H. , Shi, Z.J., Cui, J.H.: DBR: depth-based routing for underwater sensor networks. In: Proc. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manjula, R.B. , Manvi, S.S.: Issues in underwater acoustic sensor networks. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.M. , Park, S.H., Han, Y.J., Chung, T.M.: CHEF: cluster head election mechanism using fuzzy logic in wireless sensor networks. In: Proc. ICACT, pp. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. , Javaid, N., Yousaf, S., Ahmad, A., Sandhu, M.M., Imran, M., Khan, Z.A., Alrajeh, N.: Co-LAEEBA: Cooperative link aware and energy efficient protocol for wireless body area networks. 1205; 51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.H. , Kim, D., Kim, H.: IAMCTD: Intelligent adaptive mobility prediction model for city transportation using data analytics. 2016; 96. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, N. , Dave, M., Verma, A.K.: Fuzzy-based energy efficient routing protocol for underwater sensor networks. In: Soft Computing: Theories and Applications, pp. 761–769. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreyshi, S.M. , Shahrabi, A., Boutaleb, T.: Void-handling techniques for routing protocols in underwater sensor networks: Survey and challenges. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Luo, W., Liu, Z.: Game-theoretic clustering for underwater acoustic sensor networks. 2016; 53. [Google Scholar]

- Melodia, T. , Kulhandjian, H., Kuo, L.C., Demirors, E.: Advances in underwater acoustic networking. In: Mobile Ad Hoc Networking: Cutting Edge Directions, pp. 804–852. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. , Li, C., Zheng, J.: Distributed minimum-cost clustering protocol for underwater sensor networks. In: Proc. IEEE ICC, pp. 3510. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y. , Jin, Z., Chen, X., Li, D.: Reinforcement learning-based adaptive routing in underwater acoustic sensor networks. 1324; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Wang, J., Liu, Y., Zhuang, W.: Deep reinforcement learning based resource allocation in underwater acoustic communications. In: Proc. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SUNRISE Consortium: SUNRISE Project Deliverable D2.2 - Underwater Sensor Network Deployment Report. 6114.

- Coutinho, R.W. , Boukerche, A., Vieira, L.F., Loureiro, A.A.: Geographic and opportunistic routing for underwater sensor networks. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, M.C. : An overview of the internet of underwater things. 1879. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret, J. , Sendra, S., Ardid, M., Rodrigues, J.J.: Underwater wireless sensor communications in the 2.4 GHz ISM frequency band. 4237. [Google Scholar]

- Paulraj, D. , Setlur, S., Peters, D.J.: Performance evaluation of AODV, DSR, OLSR routing protocols for underwater acoustic sensor networks. In: Proc. IEEE CCNC, pp. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, M. , Cao, Y., Aslam, N., Usman, M.: Void avoidance opportunistic routing protocol for underwater wireless sensor networks. 5465; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. , Ali, I., Ghani, A., Khan, N., Alsaqer, M., Rahman, A.U., Mahmood, H.: Routing protocols for underwater wireless sensor networks: Taxonomy, research challenges, routing strategies and future directions. 1619. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).