Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composition of the EO Mix

2.2. Bacterial Strains

2.3. MIC by the Dilution Tube Method

2.4. MIC by the Automated Turbidimeter Measurements

2.5. Statistical Processing

3. Results

3.1. Composition of the EO Mix

3.2. Comparison of the Macrodilution vs Microdilution Methods for the Determination of EO Mix MIC

3.3. Growth Parameters of the Microdilution Method

3.3.1. µmax

3.3.2. lagT

3.3.3. ODmax

3.4. Technical and Statistical Comparison of the Two MIC Methods

3.4.1. Microdilution Method

3.4.2. Macrodilution Method

3.4.3. Comparison of the Macrodilution Method vs Microdilution Method

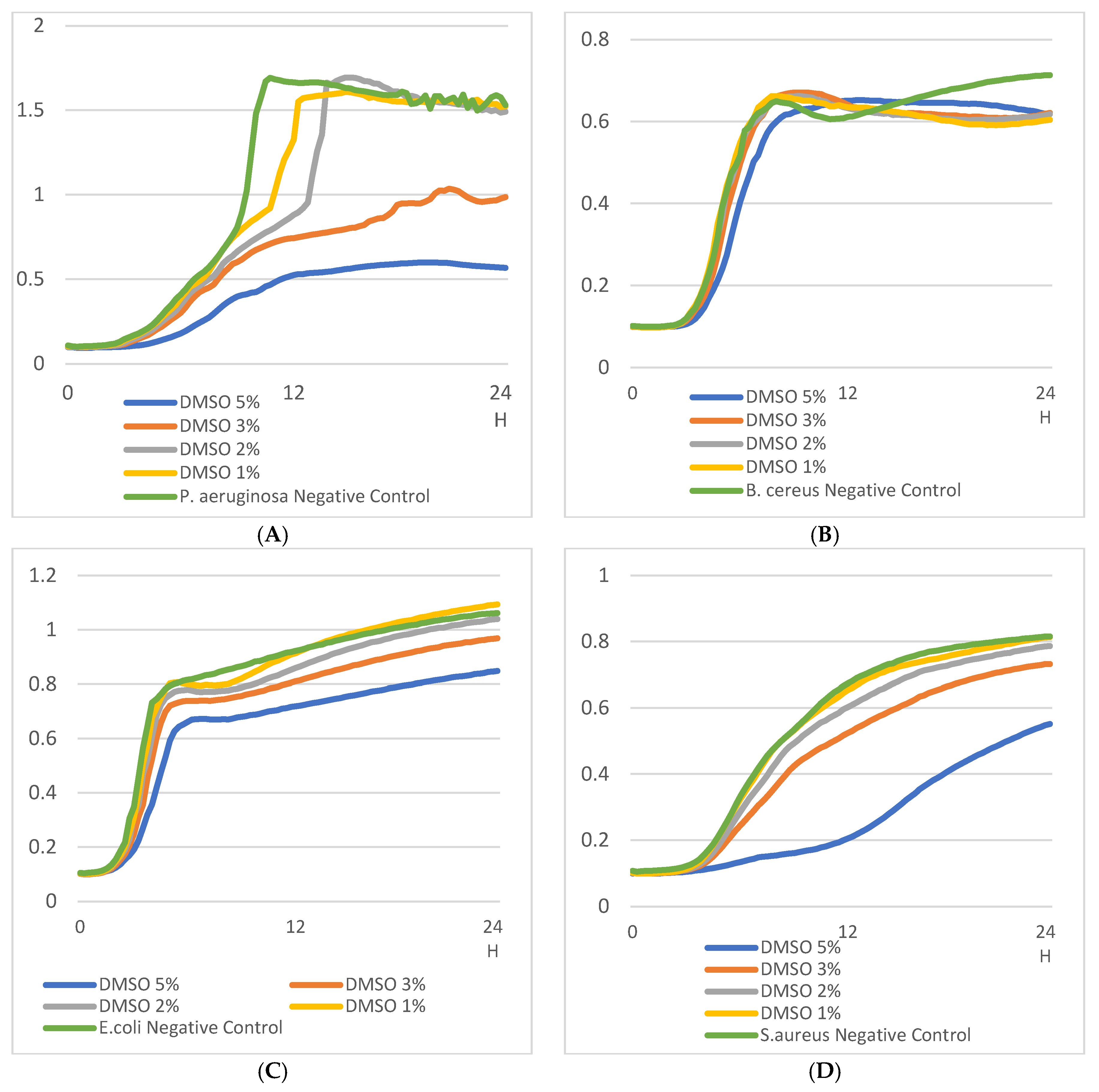

3.5. Evaluation of the Effect of DMSO on Bacterial Growth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Performing three technical and three biological replicates using an automated system for accuracy

- Combining three growth parameters (OD max, lag phase, and growth rate) to assess the impact of an EO mix, particularly at sub-MIC levels.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Helmy, Y.A.; Taha-Abdelaziz, K.; Hawwas, H.A.E.-H.; Ghosh, S.; AlKafaas, S.S.; Moawad, M.M.M.; Saied, E.M.; Kassem, I.I.; Mawad, A.M.M. Antimicrobial Resistance and Recent Alternatives to Antibiotics for the Control of Bacterial Pathogens with an Emphasis on Foodborne Pathogens. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleiro, M.L. The Mode of Antibacterial Action of Essential Oils; 2011; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, S. Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods—a Review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehme, R.; Andrés, S.; Pereira, R.B.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Bouhallab, S.; Ceciliani, F.; López, S.; Rahali, F.Z.; Ksouri, R.; Pereira, D.M.; et al. Essential Oils in Livestock: From Health to Food Quality. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, R.P.; Rana, A.; Jaitak, V. Essential Oils: An Impending Substitute of Synthetic Antimicrobial Agents to Overcome Antimicrobial Resistance. CDT 2019, 20, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yiap, B.C.; Ping, H.C.; Lim, S.H.E. Essential Oils, A New Horizon in Combating Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance. TOMICROJ 2014, 8, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, C.; Baser, K.; Windisch, W. Essential Oils and Aromatic Plants in Animal Feeding – a European Perspective. A Review. Flavour & Fragrance J 2010, 25, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Bai, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Clove Essential Oil against Foodborne Pathogens. LWT 2023, 173, 114249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Singh, P. Citrus Aurantifolia Essential Oil Composition, Bioactivity, and Antibacterial Mode of Action on Salmonella Enterica, a Foodborne Pathogen. Food Science and Engineering 2023, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milagres De Almeida, J.; Crippa, B.L.; Martins Alencar De Souza, V.V.; Perez Alonso, V.P.; Da Motta Santos Júnior, E.; Siqueira Franco Picone, C.; Prata, A.S.; Cirone Silva, N.C. Antimicrobial Action of Oregano, Thyme, Clove, Cinnamon and Black Pepper Essential Oils Free and Encapsulated against Foodborne Pathogens. Food Control 2023, 144, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, W.A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infection of Avian Origin: Zoonosis and One Health Implications. Vet World 2021, 2155–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.A.; To, E.; Fakhry, S.; Baccigalupi, L.; Ricca, E.; Cutting, S.M. Defining the Natural Habitat of Bacillus Spore-Formers. Research in Microbiology 2009, 160, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtylla Kika, T.; Cocoli, S.; Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Puvača, N.; Lika, E.; Pelić, M. Colibacillosis in Modern Poultry Production. J Agron Technol Eng Manag 2023, 6, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Tang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Tan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhou, C.; Xu, S.; Lyu, M.; Bai, Y.; et al. Staphylococcus Aureus and Biofilms: Transmission, Threats, and Promising Strategies in Animal Husbandry. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 2024, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niranjan, D.; Sridhar, N.B.; Chandra, U.S.; Manjunatha, S.S.; Borthakur, A.; Vinuta, M.H.; Mohan, B.R. Recent Perspectives of Growth Promoters in Livestock: An Overview. JLivestSci 2023, 14, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, C.; Fayolle, K.; Kerros, S.; Leriche, F. Flow Cytometric Assessment of the Antimicrobial Properties of an Essential Oil Mixture against Escherichia Coli. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences 2019, 28, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.; Missotten, J.; Dierick, N.; Fremaut, D.; Maene, P.; De Smet, S. In Vitro Degradation and in Vivo Passage Kinetics of Carvacrol, Thymol, Eugenol and Trans -cinnamaldehyde along the Gastrointestinal Tract of Piglets. J Sci Food Agric 2008, 88, 2371–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically: Approved Standard 23; USA, 2003.

- MIC Testing Supplemental Tables: Approved Standard M100; USA.

- National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard M7-A6; USA, 2003.

- Kwieciński, J.; Eick, S.; Wójcik, K. Effects of Tea Tree (Melaleuca Alternifolia) Oil on Staphylococcus Aureus in Biofilms and Stationary Growth Phase. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2009, 33, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, J.; McClure, P.J.; Sutherland, J.P.; Roberts, T.A. Modeling Bacterial Growth Responses. Journal of Industrial Microbiology 1993, 12, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayouni, E.A.; Bouix, M.; Abedrabba, M.; Leveau, J.-Y.; Hamdi, M. Mechanism of Action of Melaleuca Armillaris (Sol. Ex Gaertu) Sm. Essential Oil on Six LAB Strains as Assessed by Multiparametric Flow Cytometry and Automated Microtiter-Based Assay. Food Chemistry 2008, 111, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, N.S.; Afolayan, A.J.; Okoh, A.I. Assessment Techniques of Antimicrobial Properties of Natural Compounds of Plant Origin: Current Methods and Future Trends. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Wei, H.; Sun, H.; Ao, J.; Long, G.; Jiang, S.; Peng, J. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Oregano Essential Oil to Sows on Oxidative Stress Status, Lactation Feed Intake of Sows, and Piglet Performance. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.R.; Wilkinson, J.M.; Cavanagh, H.M.A. Evaluation of Common Antibacterial Screening Methods Utilized in Essential Oil Research. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2003, 15, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; You, N.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, P. Effect of Cellulose Nanocrystals-Loaded Ginger Essential Oil Emulsions on the Physicochemical Properties of Mung Bean Starch Composite Film. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 191, 116003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgoda, J.R.; Porter, J.R. A Convenient Microdilution Method for Screening Natural Products Against Bacteria and Fungi. Pharmaceutical Biology 2001, 39, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, D.; Abril-Novillo, A.; Khachatryan, A.; Jerves-Andrade, L.; Peñaherrera, E.; Cuzco, N.; Wilches, I.; Calle, J.; León-Tamariz, F. Validation of a Method of Broth Microdilution for the Determination of Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils. BMC Res Notes 2021, 14, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadu, M.G.; Peralta-Ruiz, Y.; Usai, D.; Maggio, F.; Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Rizzo, D.; Bussu, F.; Rubino, S.; Zanetti, S.; Paparella, A.; et al. Colombian Essential Oil of Ruta Graveolens against Nosocomial Antifungal Resistant Candida Strains. JoF 2021, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; He, Z.; Han, C.; Liu, S.; Li, Y. Influence of Surfactant and Oil Composition on the Stability and Antibacterial Activity of Eugenol Nanoemulsions. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2015, 62, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, V.; Saranya, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Cinnamon Oil Nanoemulsion Formulation by Ultrasonic Emulsification: Investigation of Its Bactericidal Activity. j. nanosci. nanotech. 2013, 13, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golus, J.; Sawicki, R.; Widelski, J.; Ginalska, G. The Agar Microdilution Method - a New Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for Essential Oils and Plant Extracts. J Appl Microbiol 2016, 121, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemba, D.; Kunicka, A. Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Essential Oils. CMC 2003, 10, 813–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.J.W.; Skandamis, P.N.; Coote, P.J.; Nychas, G.-J.E. A Study of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration and Mode of Action of Oregano Essential Oil, Thymol and Carvacrol. J Appl Microbiol 2001, 91, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, A.; Santacroce, L.; Iacob, R.; Mare, A.; Man, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Six Essential Oils Against a Group of Human Pathogens: A Comparative Study. Pathogens 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Jurado, F.; Franco-Vega, A.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Essential Oils: Antimicrobial Activities, Extraction Methods, and Their Modeling. Food Eng Rev 2015, 7, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulankova, R. The Influence of Liquid Medium Choice in Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Essential Oils against Pathogenic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in Vitro Evaluating Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K.P.; Sofos, J.N. Effect of Inoculum Size on the Combined Temperature, pH and Aw Limits for Growth of Listeria Monocytogenes. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2005, 104, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillier, L.; Nazer, A.I.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Growth Response of Salmonella Typhimurium in the Presence of Natural and Synthetic Antimicrobials: Estimation of MICs from Three Different Models. Journal of Food Protection 2007, 70, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, C.; Robinson, T.P.; Ocio, M.J.; Aboaba, O.O.; Mackey, B.M. The Effect of Inoculum Size and Sublethal Injury on the Ability of Listeria Monocytogenes to Initiate Growth under Suboptimal Conditions. Lett Appl Microbiol 2001, 33, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostro, A.; Roccaro, A.S.; Bisignano, G.; Marino, A.; Cannatelli, M.A.; Pizzimenti, F.C.; Cioni, P.L.; Procopio, F.; Blanco, A.R. Effects of Oregano, Carvacrol and Thymol on Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis Biofilms. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2007, 56, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccimiglio, J.; Alipour, M.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Gottardo, C.; Suntres, Z. Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxic Activities of the Ethanolic Origanum Vulgare Extract and Its Major Constituents. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, A.; Martínez-López, N.; Vázquez, J.A.; García, M.R. Modelling the Antimicrobial Effect of Food Preservatives in Bacteria: Application to Escherichia Coli and Bacillus Cereus Inhibition with Carvacrol. Journal of Food Engineering 2024, 361, 111734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Rodriguez, M.R.; Hernandez-Mendoza, A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Martinez-Tellez, M.A.; Martins, C.M.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F. Carvacrol as Potential Quorum Sensing Inhibitor of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Biofilm Production on Stainless Steel Surfaces. Food Control 2017, 75, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El, A.S.; Ibnsouda, K.S.; Latrache, H.; Zineb, G.; Mouradi, H.; Remmal, A. Carvacrol and Thymol Components Inhibiting Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Adherence and Biofilm Formation. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 3229–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, V.; Pesavento, G.; Maida, I.; Nostro, A.L.; Calonico, C.; Sassoli, C.; Perrin, E.; Fondi, M.; Mengoni, A.; Chiellini, C.; et al. Exploring the Effect of the Composition of Three Different Oregano Essential Oils on the Growth of Multidrug-Resistant Cystic Fibrosis Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains. Natural Product Communications 2017, 12, 1934578X1701201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adukwu, E.C.; Bowles, M.; Edwards-Jones, V.; Bone, H. Antimicrobial Activity, Cytotoxicity and Chemical Analysis of Lemongrass Essential Oil (Cymbopogon Flexuosus) and Pure Citral. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 9619–9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagawany, M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Elnesr, S.S.; Farahat, M.; Attia, G.; Madkour, M.; Reda, F.M. Use of Lemongrass Essential Oil as a Feed Additive in Quail’s Nutrition: Its Effect on Growth, Carcass, Blood Biochemistry, Antioxidant and Immunological Indices, Digestive Enzymes and Intestinal Microbiota. Poultry Science 2021, 100, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Habib, S.; Sahu, D.; Gupta, J. Chemical Properties and Therapeutic Potential of Citral, a Monoterpene Isolated from Lemongrass. MC 2020, 17, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiemsaard, J.; Aiumlamai, S.; Aromdee, C.; Taweechaisupapong, S.; Khunkitti, W. The Effect of Lemongrass Oil and Its Major Components on Clinical Isolate Mastitis Pathogens and Their Mechanisms of Action on Staphylococcus Aureus DMST 4745. Research in Veterinary Science 2011, 91, e31–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfa, Z.; Chia, C.T.; Rukayadi, Y. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Cymbopogon Citratus (Lemongrass) Extracts against Selected Foodborne Pathogens. International Food Research Journal 2016, 23, 1262. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, M.I.; Fomda, B.A.; Jaykumar, E.; Bhat, J.A. Antibacterial Activity of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon Citratus) Oil against Some Selected Pathogenic Bacterias. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 2010, 3, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murbach Teles Andrade, B.F.; Nunes Barbosa, L.; Da Silva Probst, I.; Fernandes Júnior, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2014, 26, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.D.; Markham, J.L. Susceptibility and Intrinsic Tolerance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa to Selected Plant Volatile Compounds. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2007, 103, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Kang, J.; Liu, L. Thymol as a Critical Component of Thymus Vulgaris L. Essential Oil Combats Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Intercalating DNA and Inactivating Biofilm. LWT 2021, 136, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Ghods, S.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lifestyle: A Paradigm for Adaptation, Survival, and Persistence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, L.N.; Alves, F.C.B.; Andrade, B.F.M.T.; Albano, M.; Rall, V.L.M.; Fernandes, A.A.H.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Leite, A.D.L.; De Pontes, L.G.; Dos Santos, L.D.; et al. Proteomic Analysis and Antibacterial Resistance Mechanisms of Salmonella Enteritidis Submitted to the Inhibitory Effect of Origanum Vulgare Essential Oil, Thymol and Carvacrol. Journal of Proteomics 2020, 214, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of Essential Oils on Pathogenic Bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Guo, W.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Gong, G. Antibacterial Mechanism of Thymol against Enterobacter Sakazakii. Food Control 2021, 123, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, H.; Song, Z.; Guo, H.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils against Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia and the Effect of Citral on Cell Membrane. LWT 2020, 117, 108667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Zhao, P.; He, Y.; Kang, S.; Shen, C.; Wang, S.; Guo, M.; Wang, L.; Shi, C. Antibacterial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil against Vibrio Vulnificus and Its Mechanism. Foods 2022, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gong, L.; Xie, N.; Mo, C.-H. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effectiveness of Plant Essential Oil and Its Application in Seafood Preservation: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Shankar, S.; Fernandez, J.; Juillet, E.; Salmieri, S.; Lacroix, M. A Rapid Way of Formulation Development Revealing Potential Synergic Effects on Numerous Antimicrobial Combinations against Foodborne Pathogens. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021, 158, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R. Synergism in the Essential Oil World. International Journal of Aromatherapy 2002, 12, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.R.; Singh, V.; Singh, R.K.; Ebibeni, N. Antimicrobial Activity of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon Citratus) Oil against Microbes of Environmental, Clinical and Food Origin.

- Vale, L.; De Paula, L.G.F.; Vieira, M.S.; Alves, S.D.G.A.; Junior, N.R.D.M.; Gomes, M.D.F.; Teixeira, W.F.P.; Rizzo, P.V.; Freitas, F.M.C.; Ferreira, L.L.; et al. Binary Combinations of Thymol, Carvacrol and Eugenol for Amblyomma Sculptum Control: Evaluation of in Vitro Synergism and Effectiveness under Semi-Field Conditions. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 2021, 12, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.K.; Vikraman, A.; Nithya, C.; Hari Prasath, N.; Pandian, S.K. Synergistic Antimicrobial Combination of Carvacrol and Thymol Impairs Single and Mixed-Species Biofilms of Candida Albicans and Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Biofouling 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassolé, I.H.N.; Juliani, H.R. Essential Oils in Combination and Their Antimicrobial Properties. Molecules 2012, 17, 3989–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, R.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B.; Xu, J. Evaluation of Combined Antibacterial Effects of Eugenol, Cinnamaldehyde, Thymol, and Carvacrol against E. Coli with an Improved Method. Journal of Food Science 2009, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultee, A.; Slump, R.A.; Steging, G.; Smid, E.J. Antimicrobial Activity of Carvacrol toward Bacillus Cereus on Rice. Journal of Food Protection 2000, 63, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayari, S.; Shankar, S.; Follett, P.; Hossain, F.; Lacroix, M. Potential Synergistic Antimicrobial Efficiency of Binary Combinations of Essential Oils against Bacillus Cereus and Paenibacillus Amylolyticus-Part A. Microbial Pathogenesis 2020, 141, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Strain | Macrodilution Method EO Mix MIC (µL/mL) | Microdilution Method EO Mix MIC (µL/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| B. cereus | 6.08x102 ± 2.06x102a | 2.17x102 ± 6.53x101b |

| P. aeruginosa | N.D. | N.D. |

| S. aureus | 3.92x102 ± 2.41x102a | 3.69x102 ± 6.53x101a |

| E. coli | 1.39x103 ± 7.59x102a | 5.21x102 ± 1.95x102a |

| Bacterial Strains Growth Conditions (with or Without EO Mix) | EO Mix MIC/2 (µL/mL) | Lag Phase (h) | Growth Rate (h-1) | OD Max (uOD) | R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mt* | mb** | mt | mb | mt | mb | mt | mb | mt | mb | |

| B. cereus negative control | mt1 | - | 0.093 ± 0.011 | 0.087a ± 0.026 | 3.728 ± 0.335 | 3.457a ± 0.897 | 0.737 ± 0.001 | 0.730 ± 0.039 | 81.72% | 92.50% |

| mt2 | 0.110 ± 0.000 | 4.269 ± 0.020 | 0.684 ± 0.008 | 99.50% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.059 ± 0.022 | 2.373 ± 0.309 | 0.771 ± 0.008 | 96.31% | ||||||

| B. cereus with EO mix | mt1 | 108.39 ± 32.67 | 0.672 ± 0.515 | 0.630b ± 0.407 | 0.052 ± 0.037 | 0.394b ± 0.557 | 0.112 ± 0.002 | 0.300b ± 0.140 | 91.59% | 87.90% |

| mt2 | 0.250 ± 0.071 | 1.110 ± 0.293 | 0.388 ± 0.031 | 77.75% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.969 ± 0.000 | 0.022 ± 0.006 | 0.109 ± 0.001 | 93.49% | ||||||

| mt1 | - | 0.079 ± 0.001 | 0.068a ± 0.011 | 5.358 ± 0.256 | 4.657a ± 0.628 | 0.862 ± 0.008 | 0.864a ± 0.023 | 98.04% | 97.50% | |

| E. coli negative control | mt2 | 0.063 ± 0.004 | 4.420 ± 0.408 | 0.873 ± 0.018 | 96.46% | |||||

| mt3 | 0.061 ± 0.014 | 4.194 ± 0.467 | 0.857 ± 0.044 | 97.00% | ||||||

| E. coli with EO mix | mt1 | 260.50 ± 97.50 | 0.268 ± 0.248 | 0.546b ± 0.083 | 2.015 ± 3.306 | 0.660b ± 1.122 | 0.332 ± 0.270 | 0.179b ± 0.091 | 89.90% | 82.67% |

| mt2 | 0.969 ± 0.000 | (-)0.006 ± 0.035 | 0.102 ± 0.001 | 70.18% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.402 ± 0.000 | (-)0.029 ± 0.025 | 0.103 ± 0.002 | 87.93% | ||||||

| P. aeruginosa negative control | mt1 | - | 0.233 ± 0.016 | 0.029 ± 0.023 | 7.216 ± 0.557 | 7.513 ± 2.509 | 1.546 ± 0.008 | 1.618 ± 0.071 | 98.00% | 98.00% |

| mt2 | 0.242 ± 0.036 | 9.405 ± 4.265 | 1.629 ± 0.068 | 98.00% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.213 ± 0.011 | 5.918 ± 0.749 | 1.679 ± 0.052 | 98.00% | ||||||

| P. aeruginosa with EO mix | mt1 | ind | ind | ind | ind | ind | ind | ind | ind | ind |

| mt2 | ind | ind | ind | ind | ||||||

| mt3 | ind | ind | ind | ind | ||||||

| S. aureus negative control | mt1 | - | 0.165 ± 0.053 | 0.150a ± 0.027 | 2.368 ± 0.606 | 2.146a ± 0.322 | 0.893 ± 0.127 | 0.940a ± 0.068 | 99.53% | 99.20% |

| mt2 | 0.139 ± 0.006 | 2.035 ± 0.002 | 0.955 ± 0.007 | 99.02% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.144 ± 0.007 | 2.035 ± 0.049 | 0.971 ± 0.018 | 99.06% | ||||||

| S. aureus with EO mix | mt1 | 184.61 ± 32.67 | 0.184 ± 0.108 | 0.632b ± 0.405 | 1.507 ± 1.289 | 0.579b ± 0.975 | 0.500 ± 0.343 | 0.253b ± 0.257 | 99.22% | 57.44% |

| mt2 | 0.742 ± 0.393 | 0.233 ± 0.403 | 0.155 ± 0.087 | 41.63% | ||||||

| mt3 | 0.969 ± 0.000 | (-)0.004 ± 0.006 | 0.105 ± 0.002 | 31.48% | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).