1. Introduction

The foundation of human civilization is fundamentally linked to water management. Early settlements strategically formed around rivers, lakes, and natural springs, with sophisticated channeling systems which directed water to agricultural fields and urban centers. The quantity and accessibility of water resources have directly influenced architectural development, determined construction methods and established water as a central element in built environments.

In the middle eastern architecture, water's significance transcends mere utility, it is shaped by both geographic constraints and cultural traditions. The persistent scarcity of water throughout middle east plateau necessitated innovative approaches to water management, which resulted in sophisticated systems for water extraction, conservation, and distribution. These environmental challenges brought about remarkable engineering achievements such as underground aqueducts (Qanats), storage facilities, water reservoir (Ab-Anbar), and precision irrigation techniques in Persian gardens.

This practical necessity further influenced on cultural and religious practices which enhanced water beyond a resource to a sacred element deserving reverence. Iranian cultural traditions and religious practices as a suitable case for middle east studies, institutionalized water conservation, placing it within spiritual and religious buildings such as temples, and mosques. The dual influence—environmental necessity, and cultural significance—created a distinctive approach to water management characterized by disciplined conservation and minimal wastage, which ultimately produced a civilization whose lifestyle and architectural identity were fundamentally adapted to thriving within conditions of water scarcity.

Basically, water has played a crucial role in shaping middle east and specially the Iranian architecture throughout history, influencing settlement patterns, construction techniques, and cultural traditions.

Table 1 outlines the evolution of water-related architecture in Iran, from prehistoric irrigation methods and qanats of the Achaemenid Empire to the sophisticated water reservoirs and Persian gardens of the Safavid era. The introduction of modern infrastructure, such as dams and pipelines in the 20th century, marked a shift away from traditional sustainable water management. Today, Iran faces significant water scarcity challenges, prompting a renewed interest in integrating historical water conservation techniques into contemporary architectural solutions.

In the contemporary era, industrialization and modernization fundamentally transformed humanity's relationship with nature, which perceived natural resources as commodities for extraction. This paradigm shift, along with global consumption patterns, climate change, and inefficient resource management, has precipitated numerous environmental challenges—with water scarcity emerging as particularly critical. The emergence of industrialization and modernization fundamentally changed humanity's relationship with natural resources. For example, traditional Iranian culture once revered water as both a sacred element and a precious resource requiring careful stewardship while the industrial paradigm reframed natural elements primarily as extractable commodities for energy and production. This transformation—from reverence to utilization—has profoundly impacted water management approaches, and architectural practices.

The consequences of this shift have also converged with global climate change and inefficient resource governance to create a severe water crisis throughout Iran. This environmental impact is multidimensional and increasingly critical. For example, agricultural plains suffer from aquifer depletion and consequent land subsidence; demographic patterns reveal accelerating migration toward water-rich provinces; persistent dust storms have become commonplace across diverse regions; and critical ecological systems—including historical lakes and wetlands that once inspired architectural traditions—face progressive depletion. This environmental deterioration necessitates a fundamental reassessment of water's role in contemporary Iranian architecture. The traditional architectural wisdom that once harmonized built environments with water scarcity through innovative systems like qanats, water reservoirs, and symbolic water features has been largely supplanted by standardized modern approaches that often neglect local, and environmental constraints.

Addressing the current crisis requires not only merely technical solutions but a cultural recalibration—reconnecting contemporary architectural practices with the traditional understanding of water as both functional necessity and spiritual element. By examining this architectural-environmental relationship, we can better understand how design interventions might contribute to sustainable water management while honoring the deep cultural significance water has historically held in Iranian culture.

2. Materials and Methods

This research employs a historical-analytical methodology to examine the evolving relationship between water and Iranian architecture across multiple temporal periods. This methodological framework enables systematic investigation of water's functional, symbolic, and conceptual dimensions within built environments while documenting transitions from pre-Islamic through contemporary architectural practices.

In the first step, primary and secondary historical texts describing water systems in traditional Iranian architecture were systematically reviewed, including historical manuscripts, architectural articles, and technical documents dating from pre-Islamic through contemporary periods. The particular emphasis was placed on resources which better introduce. Iran's rich water heritage, revealing its functional, and conceptual dimensions.

In the second step, water's role in the modern era was analyzed through a theoretical framework examining paradigm shifts and industrial transformations. This involved an examination of philosophical texts addressing changing human-nature relationships during industrialization, with particular focus on Heidegger's technological critiques and Illich's water historiography. In addition, the functional and conceptual transformations of water was analyzed in contemporary Iranian architecture through field observation, and comparative case studies.

3. Results

Water holds a unique position in Iran's geography and architecture. The number of water resources in the Iranian plateau is limited, and most of its rivers are seasonal, flowing only during winter and periods of rainfall. The absence of large, permanent rivers, low precipitation levels, and insufficient freshwater sources are the constituent features of the Iranian plateau. As a result, gaining access to fresh water has posed many challenges for Iranians throughout their history, prompting them to devise thoughtful solutions for utilizing, storing, and managing water efficiently, allowing their civilization to expand beyond river environments.

In addition to the environmental challenges, cultural and religious teachings have also influenced the Iranian water usage. In pre-Islamic Iran, water was regarded as a sacred, life-giving element, and various ceremonies were held to honor it, and temples were built to sanctify it. After the advent of Islam, Islamic teachings, along with its culture of frugality, promoted the responsible use of water. This interplay of environmental and cultural factors has significantly shaped water's appearance in Iranian architecture. The impact of water shortage is evident in the design and construction of Iranian buildings. Due to the scarcity of water, Iranians have consistently used water in a way to preserve it and make the most out of its limited resources.

3.1. Functional Considerations

Human usage of natural resources was primarily aimed at fulfilling functional needs. In Iranian architecture, water was used for functional purposes such as irrigation, basic everyday chores, and evaporative cooling. Agriculture was not possible without synthetic irrigation methods. Therefore, Iranians needed to develop synthetic irrigation systems and base their agricultural practices accordingly. In regions of Iran that faced low rainfall and drought, an innovative solution called the 'Qanat' was developed for extracting groundwater.

3.1.1. Qanats

Qanats embody successful ecological and cultural adaptation that have kept water flowing through desert settlements on the Persian plateau (Gleick, 1998). They are the backbone of permanent settlements, and life stability in Iran. It is also significantly contributed to the evolution of Persian gardens (see

Figure 1). In addition, the birth of these gardens is closely linked to the history of qanats, with the first gardens emerging along the qanat's water outflows. The qanat water, which is guided by a frugality-based plan, transformed dry lands into green spaces. The water flowed continuously through the garden, and any excess water was directed to other uses outside the garden. The gardens were always adjusted in size based on the available water, ensuring they could still be irrigated during periods of water shortage (Pourmand & Keshtkar, 2011).

Qanats are mainly about Qanats operate on a gravity-fed system that requires no pumps or electricity which makes them an economical solution for water transportation. Unlike surface canals, the qanat system allows for low evaporation rates since the water is transported underground. This is particularly important in arid climates where evaporation can significantly reduce available water resources. By tapping into the water table rather than surface water, it also reduces environmental disruption.

3.1.2. Water Reservoirs

The practice of building underground which prevented water loss continued in the making of water reservoirs in Iran. A water reservoir is a covered and sealed tank which is built below ground level where it is cooler and has less temperature fluctuations. The domed structure of the reservoirs played a role in keeping the water cool and preventing evaporation because the sunlight hits only a portion of the dome, and the rest of the surface received sunlight indirectly. In order to prevent air from becoming trapped and the water from heating up, some ventilation openings and windcatchers were also installed to allow airflow. This ensured continuous air circulation within the reservoir, not only ventilating the space but also contributing to the coolness and freshness of the water (Mohammadpour et al., 2016). The culture of building water reservoirs can be seen as an example of a social project, where each individual, without any expectation of material reward, contributed for the sake of God and the forgiveness of their sins. The offerings that were spent for the construction turned the water reservoirs into problem-solving buildings in popular beliefs. There are some decorations on the head of water reservoirs which holds a particular religious significance; these inscriptions depict Imam Hussain's thirst and reference the Karbala plains and the Day of Ashura.

Figure 3.

A Section of a Water Reservoir.

Figure 3.

A Section of a Water Reservoir.

Figure 4.

(a) and (b) Different views of a Water Reservoir Interior, Fars Province, Iran.

Figure 4.

(a) and (b) Different views of a Water Reservoir Interior, Fars Province, Iran.

3.1.3. Pool (Howz).

Pool is one of the most important water elements in traditional Iranian architecture, which is specifically used in hot and dry areas. People gradually stored water in big pools, and used its water for the irrigation and other purposes. Evaporation of the water in the pool helps the ventilation in the garden by developing desirable cool weather. This function was considered in its best forms in the design of pools, in a way that a part of water of the pool and its fountain was evaporated and the air stream containing the water entered the building through the ground floor windows and flew out through the small openings in the dome-shaped ceiling above the pool-house or other windows of the pool-house which caused a cooled air in effect (Soltanzadeh. H & Soltanzadeh. A, 2017).

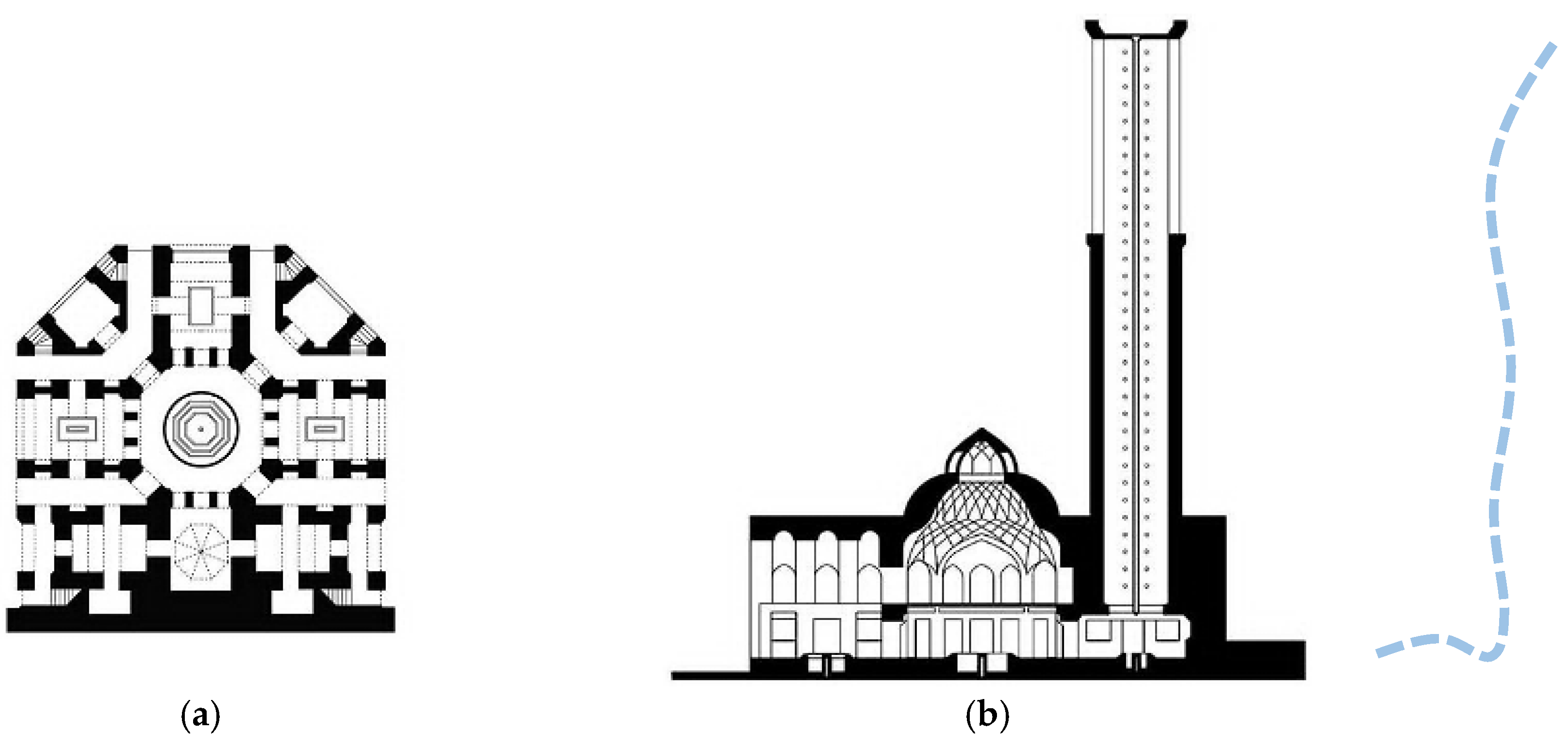

Windcatchers are important structures in this regard: these structures capture the favorable breeze and direct it over the water's surface into the main rooms of the building, water reservoirs, or basements. As the wind passes, its dust is reduced, and provides ventilation and cooling for the spaces (see

Figure 5).

3.2. Conceptual Implications

In the case of conceptual manner, water in Iran's history plays a major role in defining space identity and creating a sense of place. The ways water appeared in traditional Iranian architecture have implicit connotations. These implications have deep roots in Iranian culture, and geography. There are usually two major forms in which water could appear in traditional Iranian architecture. One is the central water features in central courtyards, and another is its axial appearance in urban areas and gardens.

3.2.1. Water Manifestations

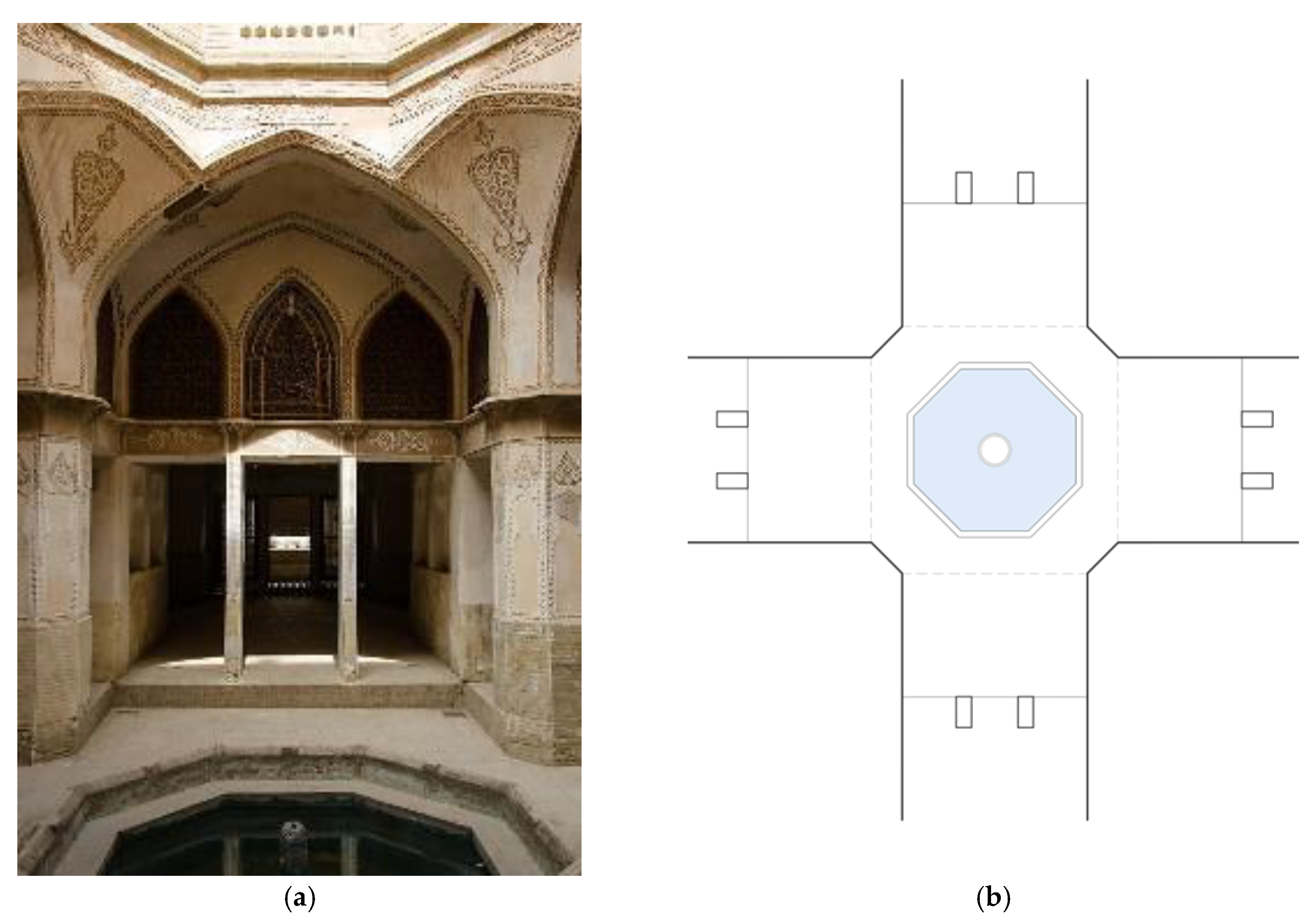

Given the climatic conditions of Iran, water plays a vital role in attracting forms of life and people around it, thereby becoming like a magnet which polarizes space. The dependent spaces within a courtyard usually focus on central pools, which their full, brimming, emerald-green surfaces reflect the divine mercy (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1973). In the traditional Iranian design of the pools, a great emphasis was placed on their central placement because the center of each space is dedicated to God in Islam (see

Figure 6).

Water features, regarded as God's creation, are located in the center of courtyards and restrict human presence in the center of the space because it is considered inappropriate. Locating the pool in the access roads to important spaces impeded the direct relocation of the individuals' right into the building as they should go around the pool along a non-direct pathway and return to their route to reach the desired space or building (Soltanzadeh. H & Soltanzadeh. A, 2017). The central presence of water also creates centrality and unity which are one of the main principles in Iranian architecture. It has the potential to establish visual continuity and cohesion within the architectural spaces, consequently making water a revered element in the center of each space.

In accordance with

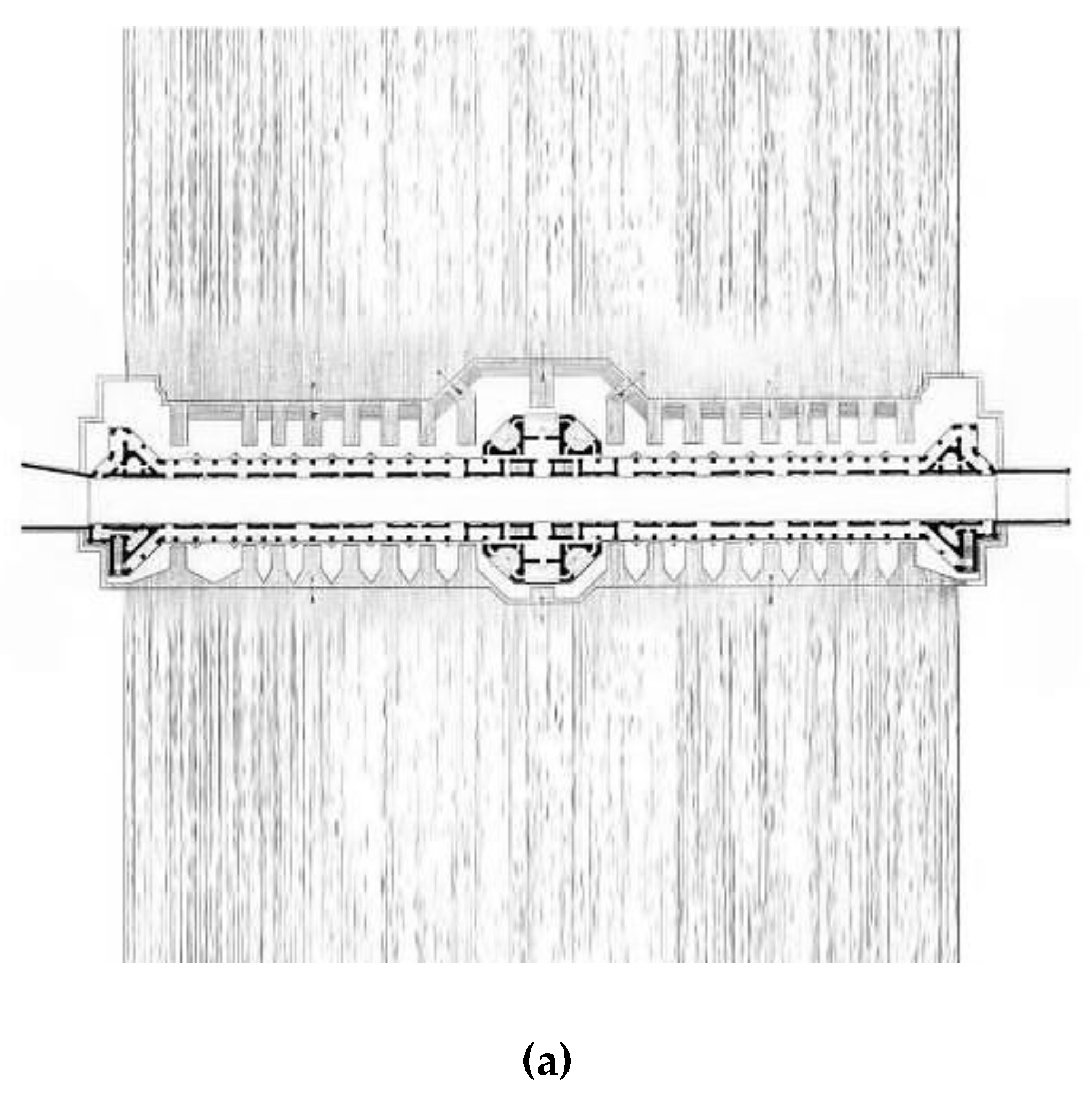

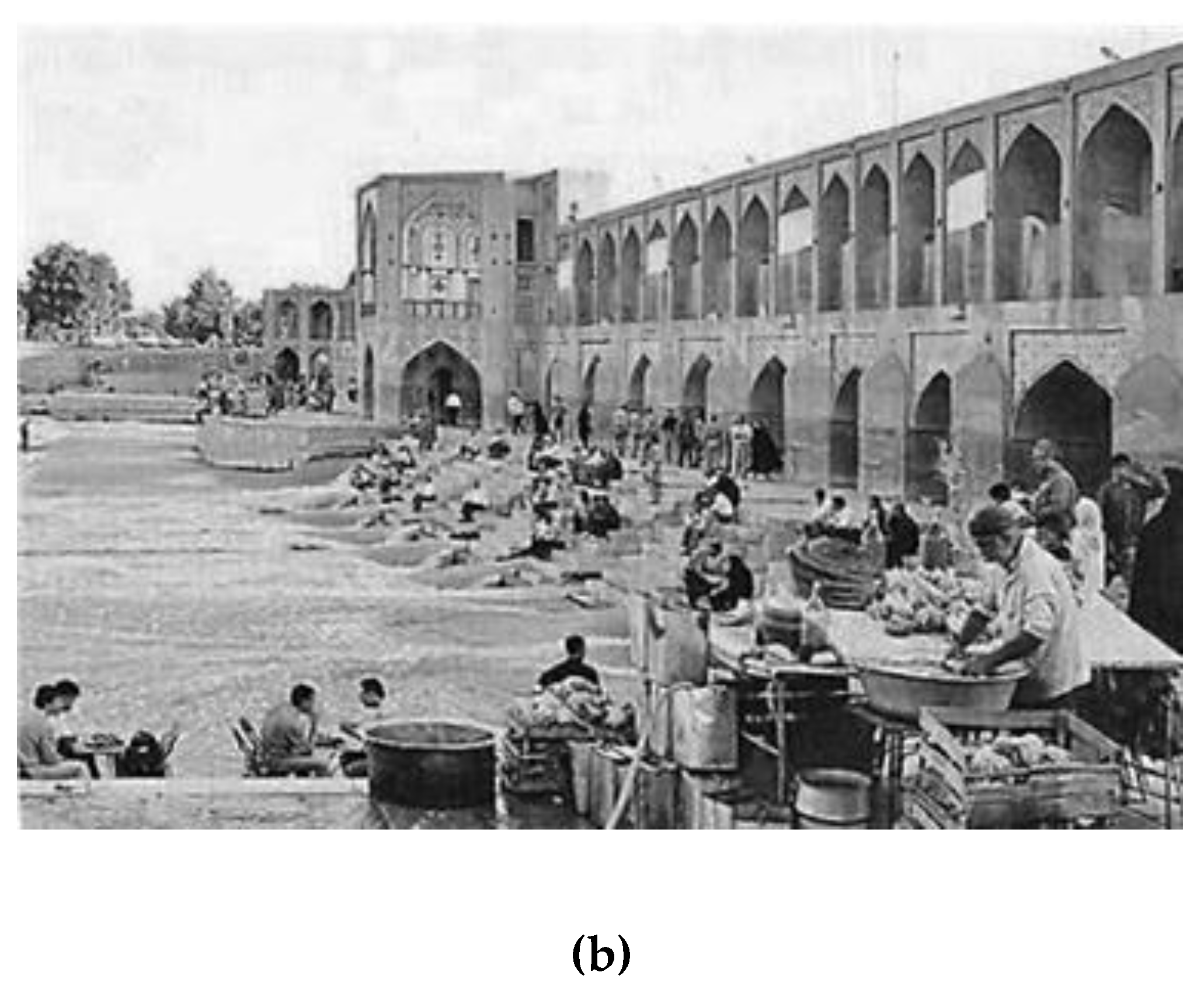

Figure 7, path of water usually defines linear order in the cities. This linear arrangement is perceptible with either surface or subsurface water channels. In the courtyard houses the water passage magnetizes the dwellings. Linear patterns of water help with spatial division, organization, and the creation of hierarchies in the space. The axial presence of water also emphasizes its dynamic characteristics that evokes a sense of transition and movement in Persian gardens, and it could act as an emphasis towards specific directions such as movement passage in the gardens or the direction of qibla in mosques. Rivers are an example of axial water presence. They form physical boundaries and, as they pass through cities, provide surrounding spaces for gatherings and social interactions (Razavi et al., 2007).

3.2.2. Cleansing and Purification

A unique aspect of water's nature is its capacity to both purify and cleanse. These two concepts differ from one another. Cleansing has a tangible identity, and in the process of performing it, dirt and the remnants of past activities are removed from the human body or physical surface. However, purification has a spiritual identity and refers to the cleansing of the inner self from impurities and sins. For cleansing, the use of water is a common and widespread method. In spiritual purification, water is not necessarily required, and in addition to water, it has been practiced through other methods as well. For example, the Chahar-shanbeh Souri festival in Iran includes activities like jumping over fire, which is considered a symbol of purification.

However, water has a unique ability to enable both cleansing and purification simultaneously. Therefore, using water for purification has been more common than other methods. Rituals such as baptism and the washing of the dead are examples of purification through water (Illich, 1985, 27).

For purification, performing some rituals with specific patterns becomes necessary. The act of ablution in Islam, due to its particular arrangements and order, enable purification, and by performing these rituals, Muslims symbolically return to their primordial state. With the widespread religious use of water, the significance of places like ablution areas and public bathhouses as spaces of purification became more prominent. According to the

Figure 8, the use of water in these places was not merely functional but also paid attention to its deeper spiritual meanings. Public bathhouses were primarily built near mosques to facilitate purification before prayer. And, in mosques and religious buildings, water was prominently featured in the courtyard to emphasize the importance of purification before prayer. This water was typically in the form of an extended rectangle, usually aligned with the length of the mosque's courtyard and serving to define the direction of the Qibla (Haghayegh & Mirshahzadeh, 2012).

3.2.3. Symbols of Water

Water is primarily regarded as a symbol of life, and its appearance in architecture is related to prosperity and fertility. Due to Iran's arid nature, water was considered as sacred and revered. people sanctified it as a life-giving element, and constructed ritual places with simple spaces for the veneration of the water wherever permanent springs of water were observed (Soltanzadeh. H & Soltanzadeh. A, 2017).

In Chogha Zanbil, water was channeled through some clay pipes to the altar, and it was regarded as sacred. There are also bas-reliefs from the Elamite civilization depicting ceremonial rituals in honor of water. In these reliefs, worshippers approached the Elamite king and passed through the water to gain an audience with him (Haghayegh & Mirshahzadeh, 2012). The rituals of water sanctification in the Elamite civilization influenced the ceremonies of the Anahita temples, the goddess of water. In these temples water was carefully displayed and sanctified. One of the most famous of these temples is the Temple of Anahita in Bishapur, which was built to showcase and honor the sacred element of water (see

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

In the ancient city of Bishapur, a precise water distribution system was executed at the sanctuary, where water was brought from the Shapur River through a 50-meter qanat to the temple. A stone water distributor, carved with geometrically arranged holes, directed the water through a network of hidden channels to the central basin. The current, gentle slope, smooth channel bed, and cross-sectional area intensity were meticulously calculated throughout the water's flow, upon reaching the central basin. The temple walls were double-layered, and the worshipers would line up in the narrow corridors in between to reach the main space of the temple. The walls framed the sky above and its reflection below allowing sunlight to illuminate the water in a basin at the center. Water symbolized a mirror of the universe in this sacred space (Al Hashemi, 2009).

3.3. Forgotten Water in the Modern Era

With the progress in scientific discoveries, a new interpretation of matter emerged. In this interpretation, the characteristics of a substance are reduced to their physical identities. For example, with the discovery of the molecular structure of water, water and H2O are not considered to be two different identities. In other words, the science of chemistry has taught us that water and its molecular structure refer to a single entity (Karbasi Zadeh & Sheikh Rezaei, 2021).

However, Ivan Illich, a philosopher and social analyst, critiques this interpretation of matter. he focuses more on the spiritual aspects of water and sees water and H2O as two completely different things. He argues that throughout history, water has been recognized as a substance with spiritual qualities, and the modern scientific interpretation of water and its formulation as H2O has reduced water to a physical liquid, distancing it from its concepts, symbols, and archetypes (Illich, 1985).

The reduction of water into its molecular structure and the influences of industry and technology have altered society's perspective on it (see

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The water circulating through urban pipelines is no more the same as the water utilized in earlier times, and it has become a result of industrial processes and technical oversight (Illich, 1985). The technical understanding of water, defined as H

2O has disconnected this element from human life's spiritual and aspects. Martin Heidegger also questions this technical understanding of water in his famous essay 'The Question Concerning Technology'. He argues that nature is often seen as a source of energy in the industrial age, with human interventions considered as an aggression. He contends that this aggression unjustly expects nature to function solely as an energy provider, enabling the extraction and storage of energy from its core (Heidegger, 1977).

The Saqqa-Khaneh is a place where a water source is created, with a small bowl placed there to make water accessible for thirsty visitors. This act of providing water was considered a good deed in Islam. Water is a revered element in this place, and it has spiritual functions.

The modern hydroelectric power station located next to the Rhine River is indeed a remarkable example of the Heidegger. It is interpreted as an example of the shift in human attitudes towards nature. He describes the decline of the Rhine and adds: 'This power station reduces the river to an energy supplier. Unlike the old wooden bridge over the river, which allowed it to be just a river and not just an energy source.' (Heidegger, 1977). This problem is known as objectification of water in the modern times when water is utilized solely as a resource for human exploitation and energy consumption. For example, employing water for extensive irrigation, electricity production, and industrial applications instead of its customary uses, such as bathing and fulfilling societal and cultural needs, is viewed as a manifestation of the objectification of water.

In the past, nature was not considered a tool for fulfilling human needs. Nature was regarded as a manifestation of existence, and humans had a direct and unmediated relationship with it. However, when nature was reduced to a tool or an instrument, consumption became the only way in which humans could relate to it. The changes in consumption patterns could influence the role of water in contemporary architecture particularly in arid countries like Iran. In addition, there is also a knowledge gap about how contemporary Iranian architecture can adapt to the challenges of water scarcity?

The developments in urbanization and rapid increases in population density made access to water resources an essential necessity. This led to the development of more advanced systems for water storage, purification, and distribution. Also, modern architectural spaces are usually designed with functional and economic considerations in mind, which limits the appearance of certain traditional forms of water features, such as large reflective pools.

4. Discussion

After the examination of water's role in traditional architecture, changes in its consumption, and re-evaluations of contemporary theories, it can be concluded that industrialization and new methods of water usage have led to the perception of water as a resource: one that can be controlled and exploited rather than an element to be respected and preserved. From a conceptual perspective, water in the contemporary era has been reduced to a purely industrial and technical substance, and its cultural and spiritual aspects is being forgotten. This series of changes, along with transformations in modern architecture, has had widespread impacts on the function and concept of water in architecture. These issues raise the question: What is the current role of the element of water in contemporary Iranian architecture, and to what extent are the frugal practices, which were prevalent in traditional architecture, being considered today?

4.1. Forgetting the Lifestyle Compatible with Water Scarcity

In many drought-prone regions such as Iran, local communities have developed experiential knowledge aligned with tough conditions over time. These experiences include qanats, water-saving methods, and efficient irrigation techniques that helped communities cope with water scarcity. Traditionally, expertise in water management was transmitted through generations, becoming an integral part of local culture.

For example, water management was a local issue in Iran, and each qanat was the result of the cooperation of all owners and beneficiaries. However, with changes in lifestyle, water-efficient practices were gradually forgotten, and modern methods have replaced them. Today, many of these methods conflict with traditional techniques. Furthermore, the appearance of water in traditional architecture was related to its scarcity. Water was usually presented at the center of each space with small fountains that pumped water gradually, and it was carefully managed and respected. However, in contemporary Iranian architecture, the water presence also has changed. Its presence is an imitation of western fountains which pumped water with pressure, and doesn’t have any relation to Iranian tradition and environment (see

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

4.2. Forgetting the Social Significance of Water

In contemporary Iranian architecture, the societal importance of water has faded for various reasons. Throughout the history of Iranian architecture, particularly in ancient Iran, water has held significant roles in communal spaces and ceremonial rituals, with features like central fountains, reflective pools, and water axes serving as focal points for communal gatherings. These spaces facilitated people to socialize and celebrate.

Due to urbanization, spatial limitations and changes in lifestyle the social role of water in architecture has been reduced. Furthermore, growing concerns about environmental issues like water scarcity and economic considerations have prompted architects to opt for more cost-effective solutions, resulting in the design of smaller-scale, easier-to-maintain water features. Consequently, the previous manifestations of water appearance like large pools that strengthened social interactions are less likely to be observed in today's architectural spaces.

One example of this reduction in the social role of water is the advent of modern plumbing in urban and residential areas, which resulted in the closure of traditional baths. Traditional baths were once pivotal for social gatherings but lost their significance with their closure. Consequently, traditional public baths were set aside in favor of indoor private baths. These baths were closely tied to particular customs, traditions, and cultural rituals, and their closure declined the preservation and passing on of these cultural practices. Also, the overall bathing space became smaller and more private. However, there are some water features in urban spaces which promote people to come together and socialize (see

Figure 15).

4.3. From a Sacred Symbol to a Functional Element

The role of water in Iranian architecture was not only to meet physical needs but also to address spiritual needs. The symbolic qualities of water evoked its spiritual aspects. Water was revered as a symbol of life and purity, and these characteristics were evident in places such as water fountains in religious places. Fortunately, Divine religions in modern times could preserve the symbolic nature of water alive through their religious rituals, such as ablution and specific bathing practices. However, with the changing needs of society and technical consideration of water, these aspects are gradually being forgotten in everyday life and Iranian architecture. Therefore, water has reduced from a sacred symbol reflecting the cultural beliefs to a mere functional element, and its use in contemporary Iranian architecture became limited to hygiene and technical aspects.

For example, according to

Figure 16, in traditional mosques, water was used as a revered and prominent element which was situated at center of the building, and helped the space to be polarized while in contemporary mosques water is reduced to a mere functional element. It is not visible and is piped through plumbing systems. People use it only for everyday washing. Currently, while the functional aspects of water are more prominent, its symbolic importance is possible to preserve. Water can still be perceived as a symbol of life and purity in Iranian culture, and contemporary architects can gain a deeper understanding of its implicit meanings and use the symbolic aspects of water to connect the past with the present (see

Table 2).

5. Conclusions

The main goal of this article is to recognize the role of water in the middle eastern architecture focusing on Iran country, understanding its importance better, and analyzing its functional and conceptual evolution. As mentioned in the text, creative solutions for utilization, storage, and appropriate water consumption were used in traditional Iranian architecture to cope with water scarcity. Functional uses were always compatible with water scarcity and created a culture of frugality. Water played a prominent role in communal spaces and ceremonial rituals. Its appearance in Iranian architecture symbolized life, purity, and abundance and fulfilled people's spiritual needs.

With the significant transformations after industrialization and modernization, a technical perception of natural elements emerged, understanding nature as a source for extracting energy. This perspective changed the water consumption patterns, resulting in consequences such as overexploitation and commodification, ultimately leading to water crisis in drier regions. These changes have extensively affected the function and concept of water in modern architecture. In other words, water has been transformed into a material that can be controlled and utilized rather than being respected and protected.

The consumer culture has led to the neglect of a lifestyle compatible with water scarcity. With the expansion of urbanization and limited space, previous forms of water presence that strengthened social connections have become less possible to emerge and manifest in contemporary architecture and urban planning. Additionally, with the changing needs of society and lifestyle, the symbolic and meaningful aspects of water in daily life and Iranian architecture is forgotten. Therefore, water has transitioned from a symbolic element reflecting cultural beliefs to a mere functional element, and its use in contemporary Iranian architecture has been limited to health and hygiene.

To address the challenges which is created by this shift, a return to traditional values and sustainable water management practices is essential. Reintegrating the symbolic and spiritual significance of water into contemporary Iranian architecture could help revive its cultural importance and emphasize more responsible usage. Modern architects and urban planners have the opportunity to draw from the rich heritage of Iranian architectural wisdom to create spaces that not only meet functional needs but also reconnect people with nature. By embracing water as both a life-giving element and a communal symbol, contemporary designs can foster a deeper respect for this vital resource and encourage a more harmonious relationship between people and their environment.

Author Contributions

A.E. and S.I.; methodology, validation, AE: formal analysis, A.E. and F.G; writing—review and editing, S.I.; visualization, S.I.; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will available after direct request to corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Hashemi, A., 2009. Temple of Water: The Anahita Temple, the emergence of architectural space in the evolution of the concept of water. Manzar Magazine, (1), pp.58-61.

- Ardalan, N. & Bakhtiar, L. (1973) The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bathaei, Bahareh. (2018). Achieving Sustainable City by the Concept of Persian Garden.

- Gleick, P.H. (1998) 'Water in Crisis: Paths to Sustainable Water Use', Ecological Applications, 8(3), pp. 571–579. [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh, M. and Mirshahzadeh, S., 2012. An Introduction to Understand Semantic, Aesthetic and Functional Characteristics of Water in Iranian Architecture. Journal of Architecture and Urban Planning, 5(9), pp.145-161.

- Heidegger, M. (1977) The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by W. Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row.

- Illich, I., 1985. H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness. Dallas, Texas: The Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture.

- Karbasi Zadeh, A. and Sheikh Rezaei, H., 2021. Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind. Tehran: Hermes Publication.

- Khakzand, Mehdi & Tabatabaee, RS. (2013). Investment Methods in Sustainable Water Resource Management using SAW Method. Journal of Armanshahr. 10.

- Lambton, A.K.S. (1992) 'The Qanāts of Yazd', Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2(1), pp. 21–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25182446.

- Mohammadpour, P., Sanieipour, H. and Sadeghi, N., 2016. Aspects of the presence of water in the architecture of traditional water reservoirs in Iran. 4th International Congress on Civil Engineering, Architecture and Urban Development, Tehran, Iran.

- Pourmand, H.A. and Keshtkar Ghalati, A., 2011. The Analysis of Essence Causes in Persian Garden. Journal of Fine Arts: Architecture & Urban Planning, 3(47), pp.51-62.

- Razavi, N., Dabiri, M., Baharlou, M. and Pakzad, P., 2007. A Song of Water, a Design of Humanity: The Role of Water in Urban Landscape Design. Collection of Articles from the Third National Conference on Green Space and Urban Landscape, (24), pp.360-370.

- Razi, H. (2006) Water Festivals. Tehran: Bahjat Publication.

- Reza, E., Kouros, G., Imam Shushtari, M. & Entezami, A. (1971) Water and Irrigation Techniques in Ancient Iran.

- Sibley, M. (2006) 'The Historic Hammāms of Damascus and Fez: lessons of sustainability and future developments', The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Soltanzadeh, H. and Soltanzadeh, A. 2017. Importance of Water and Its Elements in Persian Gardens. Manzar: The Scientific Journal of Landscape, No.38, pp. 6-17.

- Torabzade, A., 2018. Traditional irrigation system of Sulaymaniyah spring in Fin of Kashan. Kashan Shenasi, 10(2), pp.158-171.

- Zomorshidy, H. (1995). The Mosque in Architecture of Iran. Tehran: Keyhan Publishing.

Figure 1.

(a) A scheme and (b) a typical image Qanat or Kārīz, A system for transporting water from an aquifer to the surface, through an underground aqueduct. Originated approximately 3,000 years ago in Iran. With permission from: Khakzand, Mehdi & Tabatabaee, RS. (2013). Investment Methods in Sustainable Water Resource Management using SAW Method. Journal of Arma-Shahr, 11-25.

Figure 1.

(a) A scheme and (b) a typical image Qanat or Kārīz, A system for transporting water from an aquifer to the surface, through an underground aqueduct. Originated approximately 3,000 years ago in Iran. With permission from: Khakzand, Mehdi & Tabatabaee, RS. (2013). Investment Methods in Sustainable Water Resource Management using SAW Method. Journal of Arma-Shahr, 11-25.

Figure 2.

A Qanat's Outflow, Soleymaniyeh Fountain, Fin Garden, Kashan, Iran. With permission from: Torabzade, A. (2018). Traditional irrigation system of Sulaymaniyah spring in Fin of Kashan. Kashan Shenasi, 10(2), 158-171.

Figure 2.

A Qanat's Outflow, Soleymaniyeh Fountain, Fin Garden, Kashan, Iran. With permission from: Torabzade, A. (2018). Traditional irrigation system of Sulaymaniyah spring in Fin of Kashan. Kashan Shenasi, 10(2), 158-171.

Figure 5.

(a) Plan and (b) Section of a windcatcher (badgir), Dowlatabad Garden, Yazd, Iran. The wind (dashed line) passes over the water's surface, and Its dust and temperature are reduced.

Figure 5.

(a) Plan and (b) Section of a windcatcher (badgir), Dowlatabad Garden, Yazd, Iran. The wind (dashed line) passes over the water's surface, and Its dust and temperature are reduced.

Figure 6.

(a) An image and (b) a drawing of the central presence of water, located in Abbasian House, Kashan, Iran.

Figure 6.

(a) An image and (b) a drawing of the central presence of water, located in Abbasian House, Kashan, Iran.

Figure 7.

(a) Linear order and (b) Gathering space and social interaction across Khajou Bridge, Isfahan, Iran.

Figure 7.

(a) Linear order and (b) Gathering space and social interaction across Khajou Bridge, Isfahan, Iran.

Figure 8.

Ganjali Khan Bath, Kerman, Iran, Water under the Sun: A Symbol of Purification.

Figure 8.

Ganjali Khan Bath, Kerman, Iran, Water under the Sun: A Symbol of Purification.

Figure 9.

Corridors leading to the central basin, Anahita Temple, Ancient City of Bishapur, Fars Province, Iran.

Figure 9.

Corridors leading to the central basin, Anahita Temple, Ancient City of Bishapur, Fars Province, Iran.

Figure 10.

Anahita Temple, Ancient City of Bishapur, Fars Province, Iran.

Figure 10.

Anahita Temple, Ancient City of Bishapur, Fars Province, Iran.

Figure 11.

Esmaeil Tala Saqqa-Khaneh, Imam Reza Holy Shrine, Mashhad, Iran.

Figure 11.

Esmaeil Tala Saqqa-Khaneh, Imam Reza Holy Shrine, Mashhad, Iran.

Figure 13.

Detail of a Fountain, Fin Garden, Kashan, Iran. Because of water scarcity fountains are low-height and pump water gradually and with respect. With permission from: Source: Ardalan, N. & Bakhtiar, L. (1973) The Sense of Unity.

Figure 13.

Detail of a Fountain, Fin Garden, Kashan, Iran. Because of water scarcity fountains are low-height and pump water gradually and with respect. With permission from: Source: Ardalan, N. & Bakhtiar, L. (1973) The Sense of Unity.

Figure 15.

A modern forgotten Moqadam Bathhouse, Tehran, Iran.

Figure 15.

A modern forgotten Moqadam Bathhouse, Tehran, Iran.

Figure 16.

Two Manifestations of Water in Iranian Mosques: (a) Central Presence of Water in a Traditional Mosque, Shah Mosque, Isfahan, Iran. Water has appeared under the sunlight, and all of its true characteristics are emerged. With permission from:

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-imam-former-shah-mosque-1612-1630-isfahan-iran-37931745.html and (b) Ablution Place in a Contemporary Mosque, Tehran, Iran: Water is channeled through the pipes; it is not visible, and it is reduced to merely a functional element. With permission from: Zomorshidy, H. (1995). The Mosque in Architecture of Iran.

Figure 16.

Two Manifestations of Water in Iranian Mosques: (a) Central Presence of Water in a Traditional Mosque, Shah Mosque, Isfahan, Iran. Water has appeared under the sunlight, and all of its true characteristics are emerged. With permission from:

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-imam-former-shah-mosque-1612-1630-isfahan-iran-37931745.html and (b) Ablution Place in a Contemporary Mosque, Tehran, Iran: Water is channeled through the pipes; it is not visible, and it is reduced to merely a functional element. With permission from: Zomorshidy, H. (1995). The Mosque in Architecture of Iran.

Table 1.

Historical evolution of water-related architecture in the middle east (Iran): From ancient irrigation systems to modern challenges.

Table 1.

Historical evolution of water-related architecture in the middle east (Iran): From ancient irrigation systems to modern challenges.

| Time Period |

Water Sources & Management |

Architectural Elements |

| Prehistoric Settlements (Before 3000 BCE) |

Natural rivers, lakes, springs |

Basic irrigation, early canal systems |

| Elamite Civilization (3000–550 BCE) |

River-based irrigation (Karun, Dez) |

Mud-brick temples, simple water channels |

| Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE) |

Qanats, reservoirs, stepwells |

Persian gardens, palaces with water features (Pasargadae) |

| Parthian & Sassanid Empires (247 BCE–651 CE) |

Qanats, large-scale irrigation |

Bridges, baths, and water mills |

| Early Islamic Period (7th–10th Century CE) |

Expanded qanats, public wells |

Mosques with ablution fountains, caravanserais |

| Seljuk & Ilkhanid Periods (11th–14th Century CE) |

Water reservoirs, complex irrigation |

Dome-covered cisterns, madrasas with courtyards |

| Timurid & Safavid Periods (15th–18th Century CE) |

Large-scale qanats, fountains |

Persian gardens (e.g., Fin Garden), urban pools |

| Qajar Period (19th Century CE) |

First modern water distribution |

European-influenced palaces with decorative pools |

| Pahlavi Era (20th Century CE) |

Dams, modern pipelines |

Industrial water infrastructure, reduced traditional use |

| Contemporary Era (21st Century CE) |

Groundwater extraction, desalination |

Urban water scarcity challenges, sustainable architecture |

Table 2.

A Comparative Analysis of Water's Role in Iranian Architecture, Highlighting the Shift from Sacred Symbolism to Functional Application.

Table 2.

A Comparative Analysis of Water's Role in Iranian Architecture, Highlighting the Shift from Sacred Symbolism to Functional Application.

| Aspect |

Traditional Architecture |

Contemporary Architecture |

Key Drivers of Change &Potential for Reintegration |

| Function |

Spiritual cleansing,religious rituals |

Everyday washing,hygiene, practical needs |

Reduced emphasis on religious rituals; focus on efficiency. Potential: Preserve religious rituals; Rehabilitation of water-related heritages such as public baths, and cisterns to revitalize forgotten traditions, and to problematize water scarcity

|

| Placement |

Central, prominent,visible, under the sun |

Hidden, piped through plumbing systems;often unseen |

Shift from spiritual emphasis to technical considerations. Potential: Reintroduce more visible water features in meaningful ways considering its true placement in Iranian architecture.

|

| Cultural |

Reflects and reinforces cultural and social customs; fosters community gatherings |

Primarily meets physical needs; potential disconnect from the perception of water as a revered substance |

Loss of connection to the past; diminished cultural and social impact. Potential: Education, awareness, and cultural events that promote community gatherings around water features like Tirgan festival.

|

| Semantic |

Sacred symbol of life,purity, reverence; integral to spiritual experience |

Primarily a functional element for industry and hygiene; reduced symbolic importance |

Changing societal needs; Technological advancements; Secularization; Forgetting of traditions. Potential: Architects' understanding and conscious design choices to revive its symbolic meaning

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).