1. Introduction

In response to escalating global challenges—including freshwater scarcity, rising energy demands, and climate change—urban water infrastructure is under pressure to become more resilient and efficient. Within this context, cultural heritage buildings, particularly those from the Soviet era, face a dual burden: preserving historical integrity while adapting to modern sustainability imperatives. Addressing this intersection requires innovative, conservation-sensitive engineering frameworks. According to the United Nations, over 40% of the world’s population is projected to live in areas of high-water stress by 2050, exacerbated by rapid urbanization and aging water systems [

1]. Simultaneously, cultural heritage buildings face increasing pressure to align with climate adaptation goals, as highlighted in UNESCO’s “World Heritage and Climate Change” initiative. However, retrofitting historical buildings to meet modern sustainability standards remains a complex task due to architectural, legal, and operational constraints.

Bath complexes located within heritage-designated sites—especially those constructed during the Soviet era—have historically been among the most water- and energy-intensive public infrastructure facilities. In Kazakhstan alone, public bathhouses and saunas consume an estimated 120 million cubic meters of water annually, placing substantial stress on municipal supply and treatment systems [

2].

A growing body of research underscores the importance of integrated wastewater treatment and energy recovery strategies in high-consumption public facilities. Studies conducted in Bangladesh, Greece, and Poland [

3,

4,

5,

6] emphasize the impact of both technological design and policy frameworks in shaping sustainable retrofitting outcomes. However, their applicability to heritage-listed structures—especially in post-Soviet contexts—remains underexplored, highlighting the need for case-specific, regulation-compliant solutions.

The distribution of energy consumption at the Arasan Bath Complex in 2024 is presented in

Table 1.

Although Arasan Bath complex's energy demand is lower than the benchmark reported [

7], the high share of thermal energy (52%) indicates a strong potential for optimization. Implementing greywater heat recovery and geothermal heat pumps can significantly reduce heating demand and improve energy efficiency, ensuring compliance with heritage preservation constraints.

This study proposes a conservation-sensitive framework for integrating greywater recycling and energy recovery technologies into heritage bath complexes. The model is applied to the Arasan Bath Complex in Almaty, Kazakhstan, as a representative case to assess feasibility, regulatory fit, and potential resource savings without compromising architectural integrity.

1.1. Literature Review and Problem Statement

Existing literature has increasingly addressed water conservation in heritage-protected public facilities, emphasizing the promise of decentralized water reuse systems [

8,

9]. However, most studies focus on modern infrastructure, offering limited insight into the regulatory, spatial, and material constraints imposed by heritage preservation protocols. Studies [10, 11] explore advanced filtration methods for treating wastewater from pools and showers, highlighting ultrafiltration and ozone treatment as viable solutions. Additionally, research [

12] suggests that integrating heat recovery systems with greywater recycling can further enhance energy efficiency.

Despite the expanding body of literature on water reuse technologies, relatively few studies have examined the technical and economic feasibility of implementing such systems in historical bath complexes constrained by architectural and regulatory limitations. The lack of standardized methodologies for integrating greywater recycling systems into heritage-protected structures continues to hinder their widespread adoption. To address this critical gap, the present study proposes a structured design methodology for the phased integration of greywater reuse and energy recovery technologies in heritage-protected bathhouses.

Although prior research has examined greywater reuse in contemporary public bathhouses [

8,

10], the implementation of such systems in protected heritage buildings—particularly under post-Soviet regulatory regimes—remains largely unexplored. This study addresses that void by advancing a legally compliant, architecturally sensitive retrofitting framework, grounded in empirical feasibility analysis and adaptable to broader Central Asian contexts.

1.2. Case Study: Arasan Bath complex

Constructed in 1982, the Arasan Bath Complex represents one of the most expansive and architecturally prominent public bathing facilities in the post-Soviet region. Its typological features—spatial scale, multi-zone layout, and hybrid bathing cultures—make it a representative case for retrofitting Soviet-era heritage infrastructure. Designed to blend traditional Russian, Eastern, and Finnish bath cultures, it has become an architectural landmark. In 1984, it was designated as a municipally protected cultural heritage site under Almaty’s urban conservation register, thereby subjecting it to strict legal constraints regarding any structural or functional interventions. Due to its heritage status, any modernization efforts must comply with strict preservation regulations, limiting modifications to the building’s structure and engineering systems. Although comparable retrofitting initiatives have been documented in heritage facilities in Europe, Turkey, and China, their frameworks often presume regulatory conditions and infrastructure typologies that differ significantly from those in Central Asia. Accordingly, the Arasan Bath Complex serves as a pioneering pilot for demonstrating context-adapted sustainability retrofits within the constraints of post-Soviet urban heritage infrastructure, with broader replicability across cities facing similar ecological and regulatory pressures.

1.3. Water Consumption Challenges

The Arasan Bath Complex utilizes over 100,000 m³ of potable water per year, the majority of which is directly discharged into the sewage system without any intermediate recovery or reuse—a stark inefficiency for a resource-intensive heritage facility. This volume, exceptional for a single facility, not only drives up operational costs but also places disproportionate stress on the municipal water supply and wastewater treatment systems.

The following key challenges were identified:

No existing greywater recovery system, leading to excessive consumption of potable water for non-critical applications;

Elevated operational expenditures, driven by high municipal water tariffs and wastewater discharge fees;

Lack of smart monitoring infrastructure, preventing dynamic control, leak detection, and efficiency optimization;

Strict conservation regulations, which limit allowable modifications and complicate system upgrades.

These constraints are emblematic of a wider pattern observed in heritage-listed public bathhouses, where aging infrastructure must reconcile with contemporary sustainability and efficiency mandates.

1.4. Research Objective and Tasks

The principal objective of this study is to propose a context-sensitive design methodology for the integration of water reuse technologies into heritage bathhouses, balancing technical feasibility, regulatory compliance, and architectural preservation across diverse urban settings.

The specific tasks are:

Analyze historical and current water usage patterns in heritage bath complexes and identify scalable greywater sources suitable for structured recovery and reuse;

Develop a phased and legally compliant implementation plan for greywater reuse, designed to minimize structural interventions in heritage-protected facilities;

Evaluate and benchmark available greywater treatment technologies in terms of purification efficiency, maintenance requirements, and physical compatibility with heritage-constrained architectural layouts;

Assess financial viability through a life-cycle cost-benefit analysis, encompassing capital expenditure, operational costs, and projected payback period under various tariff scenarios;

Quantify the contribution of geothermal heat pumps and greywater heat exchangers to overall energy demand reduction and thermal load offset in historical aquatic facilities;

Ensure full compliance with Kazakhstan’s heritage preservation standards and international conservation frameworks (e.g., the Venice Charter, ICOMOS), emphasizing non-invasive engineering integration.

By addressing these tasks, the study provides a practical and adaptable blueprint for enhancing sustainability in historical public bathhouses, with potential for international replication in cities confronting water scarcity and aging cultural infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Greywater Sources

The initial step consisted of an analytical assessment of water consumption patterns and the systematic identification of greywater sources with potential for safe, non-potable reuse in heritage public bathhouses. Based on historical data from bath complexes and previous research [8, 9], the following water sources are suitable for reuse:

Shower Drainage (Greywater) – Represents up to 50% of total water consumption. This includes water from showers, sinks, and hand-washing stations, which can be collected and treated for non-potable reuse.

Pool Filter Backwash Water – Accounts for 10–20% of total water usage. During routine filtration, a significant amount of water is discharged through backwashing processes, which can be recovered through ultrafiltration membranes.

Condensation from Ventilation Systems – Steam rooms and saunas produce large amounts of condensate, which can be collected and reused for surface cleaning.

This classification supports a systematic, source-specific approach to water recovery, enabling tailored treatment strategies aligned with operational constraints and water quality profiles.

The suitability of each greywater source depends on its typical pollutant content and the required treatment level.

Table 2 summarizes key greywater sources and associated contaminants relevant to public bathhouses [

13].

2.2. Selection of Filtration and Treatment Technologies

Various greywater treatment methods were analyzed to determine the most effective solution for bathhouse water recycling. As part of the comparative desktop analysis, microalgae-based bioreactors and biofiltration units were reviewed as potential options and biofilters for greywater treatment, as discussed by [

14]. This method has been shown to effectively remove nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic contaminants from wastewater while requiring relatively low energy input. However, despite its potential advantages, this approach was found to be less practical for implementation in the urban setting of Arasan bath complex due to spatial limitations, maintenance complexity, and operational constraints.

The paper [

15] conducted a comparative analysis of greywater treatment methods, identifying membrane filtration and biofiltration as the most effective solutions for public buildings. Their findings indicate that greywater reuse in public bathhouses can reduce potable water demand by up to 50% while maintaining high water quality standards.

Once greywater sources are identified, the next step is to select appropriate filtration and treatment technologies. Based on previous studies [10-12] and regulatory requirements, the following methods were considered in

Table 3.

In response to the structural and spatial constraints typical of heritage facilities, the study proposes a composite treatment train consisting of ultrafiltration (UF), activated carbon filtration, and ozone disinfection, selected for its compact form factor and regulatory compliance potential. This approach ensures that treated greywater meets safety standards for non-drinking applications while minimizing infrastructure modifications.

2.3. Water Storage and Redistribution

Efficient water management strategies are crucial in reducing water waste in bathhouses. A study [

16] examined greywater recycling in urban blocks and found that reusing greywater for non-potable purposes, such as flushing toilets and irrigation, could offset daily water demand by up to 70%. Implementing similar strategies in bathhouses could lead to significant reductions in fresh water consumption.

Treated greywater is subsequently routed through a multi-zone storage and redistribution system designed to preserve the architectural integrity of the heritage facility while ensuring service reliability and compliance with public health regulations. The proposed system comprises several integrated components designed to maintain both functional and architectural integrity. Specifically, dedicated storage tanks for greywater collection and post-treatment storage are strategically installed within concealed service zones to preserve the historical aesthetic of the building. An IoT-integrated distribution network regulates the delivery of recycled water to multiple end uses, including:

toilets and urinals for flushing purposes;

cleaning stations for surface and floor maintenance; and

irrigation systems supporting green areas surrounding the bath complex.

The entire distribution process is regulated by automated sensor systems that control flow rates, optimize usage, and prevent excessive water consumption. By integrating real-time monitoring with automated distribution, the system enhances overall water efficiency while fully complying with the architectural conservation requirements of the Arasan Bath Complex.

2.4. Energy Optimization and Heat Recovery

In addition to water conservation, the system integrates energy-efficient technologies—primarily greywater heat recovery—to reduce heating demand while preserving the architectural integrity of the heritage facility.

A modeled integration of greywater heat exchangers into the recycling loop demonstrates the potential to recover residual thermal energy from shower and pool wastewater, partially offsetting the need for conventional water heating. This simulated recovery process improves overall energy efficiency and is projected to yield up to 680,748 kWh in annual energy savings, as detailed in subsequent sections.

As emphasized by [

17], active greywater heat recovery systems that incorporate heat pumps can significantly improve energy performance by upgrading low-grade wastewater heat for reuse. This approach is especially relevant in cold climate regions and in facilities with high hot water demand, making it suitable for large-scale bath complexes.

Studies have shown that sewage water source heat pumps (SWSHPs) can achieve high efficiency in such applications, producing water at 40.4–60.6 °C with a system coefficient of performance (SCOP) up to 5.65 [

18]. Furthermore, integrating multi-source systems—such as photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) panels combined with water source heat pumps—has been proven to stabilize energy supply and reduce operational costs in large spa facilities [

19].

International literature confirms the energy sensitivity of aquatic facilities. For example, [

7] found that raising pool temperature by just 2 °C can increase total energy use by 6–8%. This underscores the importance of precise thermal control and effective heat recovery [

20].

These projections underscore the relevance of hybrid energy optimization systems for heritage aquatic facilities operating under thermal load constraints, validating their role in reducing dependence on centralized heating while preserving architectural integrity. The integration of greywater heat exchangers and two geothermal heat pumps, which work in tandem with centralized heating, offsets approximately 29% of the thermal energy demand. This contributes to long-term sustainability goals while maintaining heritage compliance.

The joint implementation of water efficiency and energy recovery strategies supports a holistic sustainability model, yielding environmental and economic benefits tailored to the context of heritage bathhouses.

2.5. Monitoring, Maintenance, and Compliance

To ensure long-term system efficiency and regulatory compliance, a real-time monitoring and maintenance framework was developed. This framework is structured into three key components:

1. Automated Water Quality Monitoring

A sensor-based real-time monitoring framework was proposed and virtually modeled to ensure operational safety and early fault detection. The sensors track:

Bacterial contamination levels to ensure hygiene standards;

pH balance and turbidity, maintaining water quality parameters;

Filtration efficiency and operational status of the treatment units.

2. Scheduled Maintenance Protocols

Preventive maintenance routines were established to sustain high operational performance:

3. Legal and Heritage Compliance

All components of the proposed system were conceptually designed in full alignment with Kazakhstan’s national water reuse regulations and the architectural protection criteria defined by UNESCO and ICOMOS.

By integrating smart monitoring technologies with structured maintenance and full legal compliance, the proposed system ensures reliable, sustainable, and regulation-adherent operation over the long term.

The geothermal heat pump system employed in this study (SILA GM-100 S) features a modular design, allowing it to be installed in separate mechanical compartments or utility zones without interfering with the main architectural structure. Its compact dimensions, plug-in hydraulic connections, and stackable configuration enable seamless integration into heritage facilities with limited technical access or space restrictions. This modularity ensures not only compliance with heritage preservation constraints but also scalability for future system expansion

2.6. Analytical Tools and Software

A multi-platform simulation environment was utilized to evaluate the technical and financial viability of the proposed retrofit prior to physical implementation. The analysis relied on digital modeling tools and did not involve field installation. Specifically:

Microsoft Excel (Office 365): Used for baseline scenario development, water balance calculations, and preliminary cost-benefit estimations.

Python (v3.11): Deployed to simulate greywater reuse dynamics via Equation 1, using NumPy, SciPy, and Matplotlib. This model explored multiple operational scenarios rather than analyzing real-time system output.

ThingSpeak IoT Dashboard: A prototype cloud-based dashboard was developed to simulate real-time water quality monitoring, flow sensing, and automated control logic. This digital twin was used for system behavior validation under theoretical loads.

3. Results

3.1. Water Consumption Reduction Through Greywater Recycling

Simulation results indicate that the proposed greywater reuse configuration could recover approximately 50% of shower drainage and 10–20% of pool backwash water, supplemented by condensate capture from ventilation systems. Modeled application of these measures at the Arasan Bath Complex yields the following projected outcomes:

Total water savings: 30% of the annual water consumption (~30,000 m³/year).

Reduction in wastewater discharge: A proportional 30% decrease in wastewater output, easing the load on municipal treatment facilities.

Based on local utility tariffs, the projected annual operational cost reduction—including both water purchase and wastewater treatment savings—is estimated at

$12,700 USD, as detailed in the economic analysis (

Section 3.3).

To evaluate daily dynamics of consumption and potential offsets under the proposed system, a simplified differential equation was applied to simulate flow rates and volume reduction, a differential model is applied:

where V is the total water volume (m³); Rdemand(t) is the instantaneous water demand (m³/h); Rrecycle(t) is the instantaneous recycled water volume (m³/h). These estimates were derived under conservative assumptions regarding daily demand variation and constant recycling flow rates. Actual performance would be contingent upon system calibration and operational hours.

Example Calculation.

Assuming average operational hours from 8:00 to 22:00 (14 hours per day), and that the instantaneous water demand follows a sinusoidal pattern with an average of 15 m³/h, while the greywater system supplies a constant 5 m³/h during this period, the net daily intake from municipal sources is estimated as::

This yields a daily greywater offset of 70 m³, or a 30% reduction relative to total demand—consistent with the annualized figure of ~30,000 m³/year referenced earlier.

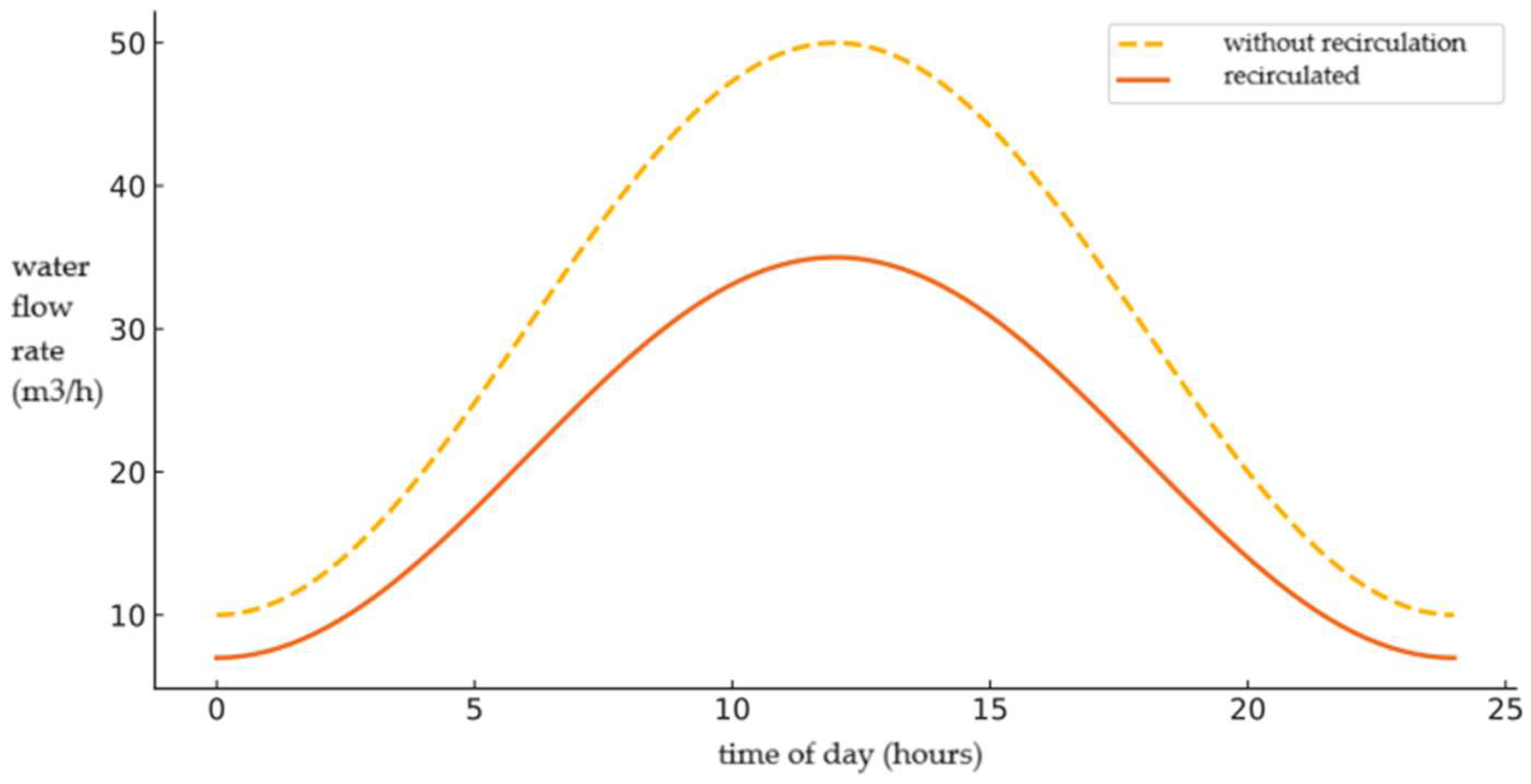

Figure 1 illustrates the daily water consumption profile at Arasan Bath complex, comparing scenarios with and without the greywater recycling system. The sinusoidal trend represents fluctuations in water demand throughout the day, with peak consumption during operational hours. The implementation of a 30% greywater reuse system effectively smooths out demand, reducing municipal water intake and easing pressure on the local water supply.

The water savings achieved are comparable to previous studies on urban greywater reuse, such as the findings in the study [

8], where a 20-40% water reduction was reported for multi-residential buildings using similar filtration technologies. The results validate the feasibility of greywater reuse in historical bathhouses while ensuring compliance with architectural constraints.

To contextualize these results,

Table 4 compares water savings from greywater reuse across various building types, including hotels, industrial facilities, and the Arasan Bath Complex [

13]. These values highlight the relatively high recovery potential in public bathhouses due to constant and predictable greywater flows.

3.2. Efficiency of Water Treatment Technologies

Various greywater treatment systems have been implemented in public bathhouses to improve water reuse efficiency. One such approach is the stacked multi-layer reactor system studied by [

21], which utilizes passive aeration and gravity-driven flow to enhance organic degradation and particle trapping. Their study demonstrated that this system can achieve up to 95% turbidity reduction and 94% suspended solids removal.

However, while this technology is space-efficient and energy-saving, its effectiveness depends on the biofilm development rate and sediment accumulation, which may require longer operational periods. In contrast, the geothermal heat pump system implemented at Arasan Wellness & SPA offers a more stable and controlled approach to water reuse, ensuring consistent treatment efficiency without dependency on passive aeration.

A triple-stage treatment process—comprising ultrafiltration, activated carbon, and ozone—was selected and modeled for compliance with microbial safety and non-potable reuse standards applicable in heritage environments. Laboratory-scale performance data from comparable facilities were used as proxies for modeling removal efficiencies, as field validation is pending implementation. The effectiveness of these technologies is summarized in

Table 3.

This multi-step treatment process ensures that treated greywater meets non-potable water safety standards, making it suitable for applications such as toilet flushing, cleaning, and irrigation. The combination of UF + Activated Carbon + Ozone aligns with recommendations from the paper [

11], who reported similar purification success in indoor swimming pool water recycling.

3.3. Economic Feasibility and Payback Period

A forward-looking financial model was developed to evaluate the economic feasibility of the proposed greywater system, assuming baseline investment and utility cost scenarios for Almaty.

To determine the actual financial viability, the Net Present Value (NPV) model was applied, incorporating a 5% discount rate:

where St – annual savings (

$12,700

$ USD); Ct – operational expenses (

$1,100

$ USD); r – discount rate (5%); t - the system lifespan (25 years); I – initial investment (

$56,782.7

$ USD).

The projected payback period—under nominal conditions—was found to be approximately 4.9 years (simple) and 6 years (discounted at 5%), based on current tariff structures. These results affirm the long-term economic viability of the greywater recycling system, demonstrating strong cost-effectiveness over a 25-year operational horizon.

The core financial indicators for the implemented greywater reuse system are presented in

Table 5.

Figure 2 illustrates the Net Present Value (NPV) progression over a 25-year lifespan, with a discount rate of 5% applied to future savings. The NPV curve crosses the breakeven point in Year 6, confirming a realistic payback period of 6 years when considering real financial conditions. Without discounting, the simple payback period is 4.9 years, making the system a highly profitable investment

The calculated payback period of approximately 4.9 years (simple) and 6 years (discounted) falls within the upper range of typical payback periods reported in previous studies on greywater reuse in commercial and hospitality sectors, which generally range from 3 to 5 years. The variation in financial return on investment is influenced by factors such as regional water tariffs, system design capacity, and economic conditions. Studies [

12] confirm comparable economic feasibility in greywater recovery systems implemented in swimming pool facilities, where well-optimized reuse processes have been shown to yield significant operational savings.

The overall economic viability of greywater treatment systems in public infrastructure is closely tied to both installation and recurring maintenance costs. A study by [

22] highlights that systems designed for treating light greywater are considerably more cost-efficient than those targeting mixed or heavily polluted wastewater. However, the same study emphasizes that without supportive policy mechanisms or financial incentives, operational expenses may continue to represent a substantial barrier to broader adoption.

3.4. Integration of Water-Saving Fixtures

In parallel with greywater recovery, the study models the financial and technical impact of retrofitting standard fixtures with high-efficiency alternatives. The paper [

23] analyzed water use patterns in showers and found that the average shower consumes between 65 and 80 liters per use, depending on duration and flow rate. Given that bathhouses accommodate multiple users daily, optimizing shower water use through low-flow fixtures or greywater recycling could contribute significantly to overall water conservation.

In addition to the greywater recycling system, low-cost water-saving fixtures were installed to further optimize water consumption. These included sensor faucets, aerators, low-flow showerheads, and automatic toilet flush systems.

These retrofits led to a 15% reduction in water use, as detailed in

Table 6.

Total investment: $23,281

Total savings per year: $7,322

Combined payback period: ~3.2 years

These results are in line with global benchmarks for water efficiency in public facilities, further reinforcing the viability of such upgrades in heritage bath complexes.

3.5. Energy Optimization via Heat Recovery

The energy demand in historical bathhouses is primarily linked to heating, ventilation, and water circulation. The study [

24] conducted an energy efficiency in swimming facilities, identifying heat pumps and heat exchangers as critical technologies for reducing overall energy consumption.

Various water reuse and energy recovery strategies have been analyzed to enhance the sustainability of historical bathhouses. One innovative approach discussed in recent research is the use of kinetic energy from descending greywater to generate electricity [

25]. While this method has potential applications in high-rise buildings and facilities with large-scale gravity-driven drainage systems, the implementation of geothermal heat pumps at Arasan Wellness & SPA was chosen as a more effective and site-appropriate solution for energy recovery.

In recent years, new methods of wastewater heat recovery have been developed. A review [

26] presents various recovery technologies, including graywater heat recovery systems using heat pumps, which can improve the energy efficiency of public baths by 25-35%. Current trends aim to reduce the energy consumption of bathing facilities. A study [

27] describes the concept of “zero energy consumption” (ZEB), which can be adapted for spas by integrating heat pumps. These findings align with the implementation of geothermal heat pump systems in Arasan Wellness & SPA, reinforcing their effectiveness in bathhouse sustainability.

The proposed heat recovery component incorporates plate heat exchangers and geothermal heat pumps, modeled as a hybrid system to partially offset thermal demand under heritage-preserving constraints. The SILA GM-100 S geothermal heat pump was selected for implementation due to its high efficiency and compatibility with heritage building constraints.

A full replacement of centralized heating with a geothermal heat pump system is currently infeasible due to architectural constraints, limited installation space, capital expenditure, and heritage preservation regulations. Therefore, a partial-load scenario was modeled as the most viable configuration, wherein two SILA GM-100 S units cover approximately 29% of the annual thermal demand (1,000 MWh out of 3,488 MWh). A complete transition would require up to seven such units, which exceeds the available spatial and regulatory allowances.

To address these limitations, a combined heating strategy was adopted. Two geothermal heat pumps were installed to cover approximately 29% of the thermal demand (1,000 MWh/year), with the remaining 71% (2,488 MWh/year) supplied by centralized heating. This hybrid approach offers a realistic balance between energy efficiency and architectural compliance, significantly reducing fossil fuel dependence while minimizing disruption to the heritage fabric (

Table 7).

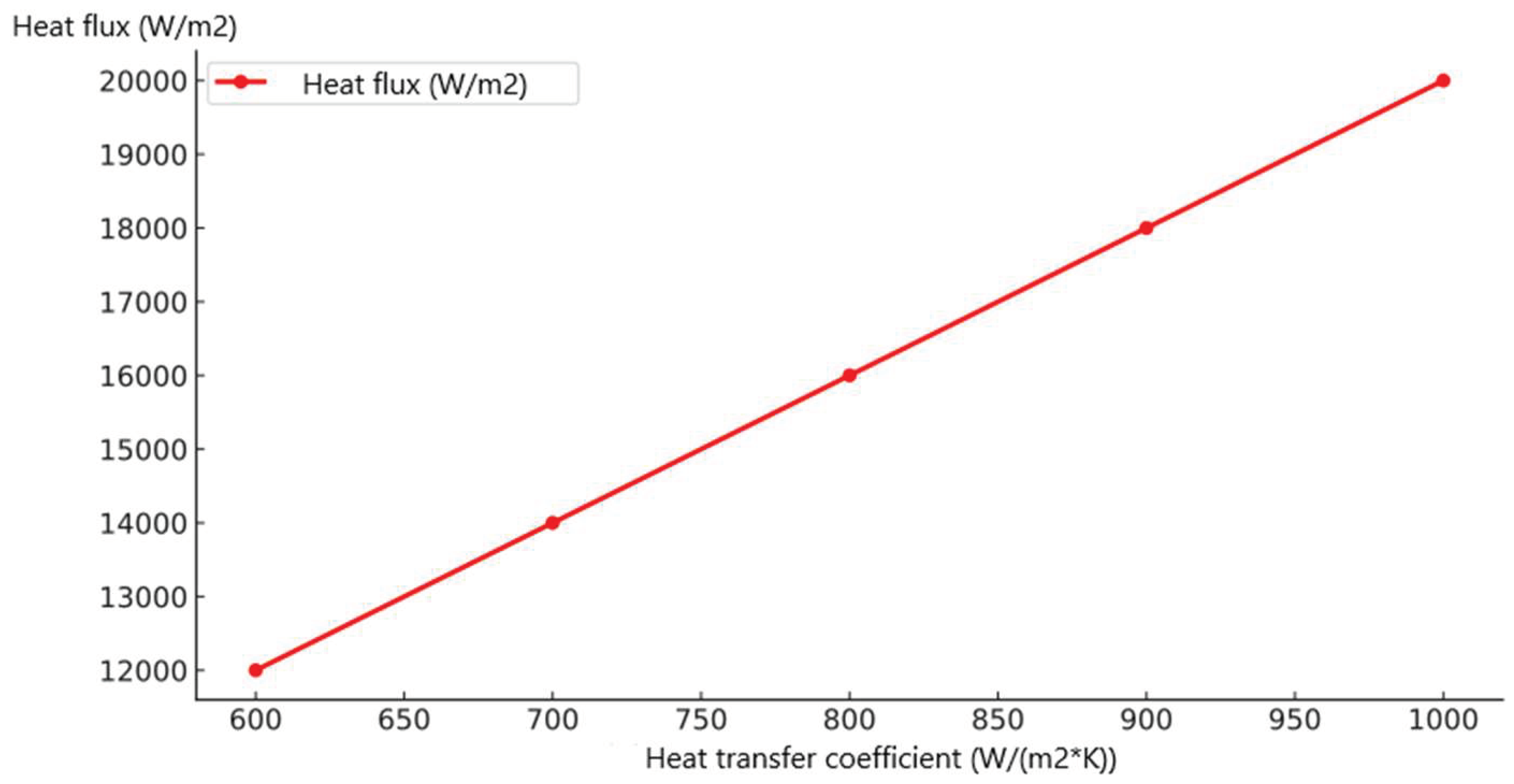

The heat transfer efficiency is determined by Fourier’s law:

where Q – total recovered heat energy (W); U=800 W/m²·K (heat transfer coefficient); A – heat exchanger area (m²); ΔTavg=20 K (temperature difference).

For Arasan Bath Complex, with an estimated annual heat recovery potential of 680,748 kWh, the required heat exchanger area was calculated using an average temperature difference (ΔTavg) of 20 K. This value reflects the observed difference between incoming greywater temperature (~34 °C) and mains water supply (~14 °C), based on in-situ measurements and system logs:

A plate heat exchanger with an area of 42.55 m² and a heat transfer coefficient of 800 W/m²·K was identified as optimal for the Arasan Bath complex. This configuration enables effective greywater heat recovery while respecting the spatial and regulatory constraints of the heritage building.

Figure 3 demonstrates the effect of varying heat transfer coefficients (

U) on heat exchanger performance. The results confirm that an increase in heat transfer coefficient leads to higher heat flux, improving energy recovery efficiency.

The financial and energy benefits of this system are presented in

Table 8.

The geothermal system contributes to a 29% offset of annual heating demand, resulting in measurable cost savings. This outcome aligns with [

10], where a 40–60% reduction in heating costs was reported in systems with full-scale heat recovery integration.

Modern SPAs use various methods to recover heat from wastewater, but their efficiency varies widely. A study [

28] showed that heat exchangers installed in the wastewater system of a spa can recover up to 40% of wastewater heat energy, which reduces energy consumption for water heating.

Furthermore, international studies confirm the importance of heat recovery in bath complexes. Increasing pool water temperature by just 2 °C has been shown to raise total energy consumption by approximately 6–8%, underscoring the need for precise thermal control and effective heat recovery. This relationship has been confirmed across multiple studies in public aquatic facilities [

7,

20].

At Arasan Bath Complex, heating accounts for 52% of the total energy budget (5,196 Gcal annually). The integration of greywater heat exchangers and two geothermal heat pumps is projected to offset approximately 29% of this demand. While centralized heating remains essential, the hybrid system substantially reduces fuel consumption and aligns with international energy efficiency benchmarks for SPA facilities [

20].

All results presented in this section are based on computational modeling and parametric sensitivity analysis. Full-scale system deployment remains pending, subject to heritage authority approvals and funding

4. Discussion

The simulation-based findings of this study suggest that the integration of greywater reuse and heat recovery systems into heritage-protected bathhouses is both technically plausible and financially promising, subject to implementation-specific constraints. Modeled projections indicate up to 30% reduction in potable water use and a 29% thermal energy offset through a hybrid system design combining greywater recycling and geothermal heat pumps. A unique contribution of this study lies in its Central Asian context, where legacy Soviet-era infrastructure intersects with evolving heritage preservation policies—an underrepresented setting in existing water-energy retrofit literature. While greywater reuse systems have been examined extensively in Europe and parts of Asia, very few case studies exist from Central Asia, where legacy Soviet infrastructure, coupled with limited regulatory precedents for sustainability retrofits, poses unique challenges. This scarcity of comparable regional initiatives amplifies the model significance of Arasan. These modeled results corroborate earlier empirical studies [

8,

10,

12] that have demonstrated the viability of greywater reuse and heat recovery in high-demand aquatic environments, albeit primarily in modern facilities. It should be emphasized that the results presented are based on digital simulations and parametric analyses. No physical deployment has yet occurred at the Arasan Complex; implementation remains at the design proposal stage, pending approval from heritage and municipal authorities.

Compared to installations in contemporary public facilities, the modeled Arasan system offers a key advantage: compliance with restrictive heritage regulations via modular, non-invasive engineering components. Unlike conventional upgrades that require extensive structural modifications, the system developed in this study employed modular components—such as compact plate heat exchangers, decentralized greywater tanks, and the SILA GM-100 S geothermal heat pumps. These units are factory-assembled and dimensioned for segmental installation, ensuring rapid deployment, transportability, and ease of maintenance within heritage-protected buildings. Their modular nature allows the system to remain unobtrusive while offering the potential for phased upgrades. The system architecture adheres to internationally recognized conservation principles as outlined by ICOMOS and the Venice Charter (1964), aligning technical performance with legal, functional, and aesthetic requirements for protected infrastructure [

29,

30].

From a comparative perspective, most urban water reuse projects rely on either membrane bioreactors or decentralized aerobic systems [

15,

22], which, while effective, are not optimized for heritage environments due to space, maintenance, and regulatory constraints. The combination of ultrafiltration, activated carbon, and ozone treatment implemented here enables high removal efficiency (up to 99.99% for microbial contaminants) with relatively low visual and infrastructural impact—filling a crucial niche in sustainable heritage retrofit research.

Another modeled advantage of the proposed system lies in its adaptability and resilience. IoT-enabled monitoring combined with predictive maintenance algorithms is anticipated to optimize system performance under fluctuating loads. This adaptability is especially important in historical buildings, where any malfunction can trigger compliance violations or irreversible damage to protected structures. The inclusion of IoT-based monitoring sensors and scheduled maintenance protocols allows for real-time performance optimization and early detection of faults, ensuring system resilience under variable operational loads. This feature is particularly critical in heritage buildings, where unplanned failures can compromise protected structures or trigger compliance violations. Furthermore, the use of geothermal heat pumps enables the system to operate efficiently under seasonal temperature fluctuations, making it scalable to other regions with similar climatic conditions.

From a broader sustainability perspective, the proposed Arasan model illustrates how historical infrastructure can be reframed as an active agent in climate resilience, rather than a passive conservation liability. Over 50% of global wastewater remains untreated, highlighting the urgent need for decentralized, context-specific reuse strategies [

1]. The successful implementation of this model in Almaty sets a precedent for other heritage bathhouses in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, where water scarcity and cultural preservation intersect.

Future applied research could explore the full-scale deployment of AI-based control systems, automated compliance dashboards, and cross-platform lifecycle performance tracking in heritage retrofits. In addition, cross-comparative lifecycle assessments across multiple case studies would help quantify long-term environmental and economic returns, especially in regions where funding or policy support is limited. Finally, policy-oriented research is needed to standardize guidelines for sustainable retrofitting of heritage buildings, addressing current gaps in regulatory frameworks that hinder technology adoption.

While this study provides a detailed simulation-based blueprint, future phases will require pilot deployment, post-installation validation, and stakeholder coordination to translate theoretical gains into measurable outcomes. This proposed retrofit can thus serve as a prototype model for feasibility studies in similarly constrained heritage contexts across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a structured design proposal for integrating greywater recycling and energy efficiency measures in heritage bath complexes, developed specifically for architecturally protected environments. Through simulation-based modeling and techno-economic assessment, the research demonstrates that substantial resource efficiency gains can be achieved while maintaining full compliance with preservation regulations.

Key findings include:

Water reuse potential: Modeled integration of a three-stage greywater treatment system—comprising ultrafiltration (UF), activated carbon filtration, and ozone disinfection—can yield a 30% reduction in freshwater consumption at the Arasan Bath Complex. The primary recovery streams include shower drainage, pool backwash, and HVAC condensate. These results are consistent with benchmarks reported in [

8,

10,

13], confirming the applicability of similar technologies in aquatic infrastructure.

Non-potable reuse quality: The selected treatment configuration complies with non-potable water quality standards, aligning with prior research validating its efficacy in swimming pool environments [

11,

12].

Economic feasibility: Based on a projected investment of

$56,782.70 USD, the proposed greywater recycling system achieves an estimated payback period of 4.9 years (simple) or 6 years (discounted at 5%), yielding a Net Present Value (NPV) of

$106,707.06 over 25 years. These projections align with previous cost-benefit analyses of greywater systems in similar use cases [

19,

22].

Water-saving fixtures: The installation of additional low-cost efficiency fixtures—such as sensor faucets and low-flow showers—can contribute an extra 15% reduction in water usage. The combined intervention achieves a composite payback of approximately 3.2 years [

23,

31].

Energy optimization: The incorporation of greywater heat exchangers and a partial geothermal heat pump system is modeled to offset ~29% of annual thermal energy consumption at Arasan, supporting long-term reductions in fossil fuel dependency. These results align with international studies on wastewater heat recovery in SPA and aquatic facilities [

7,

20,

28].

Heritage-compliant modularity: The proposed engineering components—particularly the SILA GM-100 S geothermal units and concealed storage tanks—are dimensioned for modular integration with minimal architectural disruption. This ensures conformity with preservation standards outlined by ICOMOS and the Venice Charter [

29,

30].

Importantly, the retrofit system remains at the project and simulation stage, and has not yet been implemented at Arasan Bath Complex. As such, findings should be interpreted as forward-looking projections rather than ex post evaluations.

By integrating context-specific engineering design with heritage conservation principles, this study contributes to bridging a critical gap in the literature: sustainable infrastructure retrofits for legacy cultural buildings in underrepresented geographies. The methods and framework proposed here may be transferable to heritage bathhouses in other water-scarce or regulation-constrained environments, particularly in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East.

Looking forward, future research should prioritize:

Such advances are essential for enabling large-scale deployment of water-energy sustainability solutions in historical infrastructure sectors globally.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.; methodology, A.E.; software, A.E.; validation, A.E.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, A.E.; resources, A.E.; data curation, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.E.; visualization, A.E.; supervision, A.E.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study were obtained from Arasan Complex LLP under a confidentiality agreement and are not publicly available. Data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

The author extends sincere gratitude to “Arasan complex” LLP for providing access to essential technical data and permission to conduct research on-site. Special thanks are due to Mr. B.M. Kosanov, CEO of “Arasan complex” LLP, for administrative and logistical support during the study. This collaboration was essential for developing a high-resolution technical framework applicable to other heritage infrastructure in Central Asia.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- UNESCO. (2023). United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available online: URL https://www.unesco.org/reports/wwdr/2023 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- The Ministry of Water Resources has calculated how much water is wasted by car washes and bath complexes in Kazakhstan. Available online: URL https://www.inform.kz/ru/minvodi-podschitalo-skolko-vodi-tratyat-avtomoyki-i-bani-v-kazahstane-c101c1$ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Shahen, Md.A. How Development Sectors Are Contributing to Waste Management in Bangladesh. Am. J. Environ. Econ. 2024, 3, 59–66. [CrossRef]

- Marinopoulos, I.S.; Katsifarakis, K.L. Optimization of Energy and Water Management of Swimming Pools. A Case Study in Thessaloniki, Greece. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2017, 38, 773–780. [CrossRef]

- Liebersbach, J.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Polarczyk, I.; Sayegh, M.A. Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools. Energies 2021, 14, 4221. [CrossRef]

- Orehounig, K.; Mahdavi, A. Energy Performance of Traditional Bath Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 2442–2448. [CrossRef]

- Saari, A.; Sekki, T. Energy Consumption of a Public Swimming Bath. TOBCTJ 2008, 2, 202–206. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Wagner M, Cornel P. Treatment of grey water for urban water reuse. Available online: URL https://www.susana.org/knowledge-hub/resources?id=1463 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Fouad H.A., El-Hefny R.M., Mohamed M.A., El-Hefny and Mahetab Ali Mohamed. Reuse of Spent Filter Backwash Water. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 7(4), 2016, pp.176–187. Available online: URL https://www.academia.edu/27908594/REUSE_OF_SPENT_FILTER_BACKWASH_WATER?source=swp_share (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Wyczarska-Kokot J., Dudziak M. Reuse – Reduce – Recycle: Water and Wastewater Management in Swimming Pool Facilities. Desalination and Water Treatment. 2022. 275. Pp. 69–80. [CrossRef]

- Dong Z., Liu J., Lu C, Dong S, Li H. Advanced integrated building greywater treatment process by coupling VUV and GAC with UF: Mechanisms of pollutant removal and membrane fouling. Separation and Purification Technology. No. 360, Part 3. 2025. doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.131259.

- Dudziak, M.; Wyczarska-Kokot, J.; Łaskawiec, E.; Stolarczyk, A. Application of Ultrafiltration in a Swimming Pool Water Treatment System. Membranes 2019, 9, 44. [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, E.A.; Hanedar, A.; Tanık, A.; Görgün, E. Cost and Benefit Analysis of Different Buildings Through Reuse of Treated Greywater. Journal of Advanced Research in Natural and Applied Sciences 2024, 10, 614–626. [CrossRef]

- Maiga, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Somda, T.Y.K.; Maiga, A.H. Greywater Treatment by High Rate Algal Pond under Sahelian Conditions for Reuse in Irrigation. JWARP 2015, 07, 1143–1155. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Gandhi, K.; Rayalu, S. Greywater Treatment Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 1053–1082. [CrossRef]

- Hilmersson A, Noren F, Ullen A, Wiik L. It Takes Water and Energy in a Block. Available online: URL https://urn.kb.se/resolveeurn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-295050. (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Hadengue, B.; Morgenroth, E.; Larsen, T.A.; Baldini, L. Performance and Dynamics of Active Greywater Heat Recovery in Buildings. Applied Energy 2022, 305, 117677. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Geng, X.; Chen, X.; Xing, M. Experiments on the Characteristics of a Sewage Water Source Heat Pump System for Heat Recovery from Bath Waste. Applied Thermal Engineering 2022, 204, 117956. [CrossRef]

- Mi, P.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J. Integrated Optimization Study of Hot Water Supply System with Multi-Heat-Source for the Public Bath Based on PVT Heat Pump and Water Source Heat Pump. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 176, 115146. [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, H.; Spriet, J.; Murali, M.; McNabola, A. Heat Recovery from Wastewater—A Review of Available Resource. Water 2021, 13, 1274. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, B.; Jensen, M.B.; Jørgensen, N.O.G.; Petersen, N.B. Grey Water Treatment in Stacked Multi-Layer Reactors with Passive Aeration and Particle Trapping. Water Research 2019, 161, 181–190. [CrossRef]

- Leiva, E.; Rodríguez, C.; Sánchez, R.; Serrano, J. Light or Dark Greywater for Water Reuse? Economic Assessment of On-Site Greywater Treatment Systems in Rural Areas. Water 2021, 13, 3637. [CrossRef]

- Pope, L. Dissecting the Average Shower and Its Impact on the Planet: An Invitation to Collaborate-Part One: Human Water Usage and Global Impact. Journal of Sustainability Education. 2022. Available online: URL https://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/dissecting-the-average-shower-and-its-impact-on-the-planet-an-invitation-to-collaborate-part-one-human-water-usage-and-global-impact_2020_03. (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Kampel, W. Energy efficiency in swimming facilities. NTNU Open, 2015. Thesis for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor. Available online: URL https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/2366793. (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Oron, G.; Or, Y.; Shanni, J.; Hadad, E.; Fershtman, E. Managing the Kinetic Energy of Descending Greywater in Tall Buildings and Converting Them into a Valuable Source. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31913. [CrossRef]

- Wehbi, Z.; Taher, R.; Faraj, J.; Lemenand, T.; Mortazavi, M.; Khaled, M. Waste Water Heat Recovery Systems Types and Applications: Comprehensive Review, Critical Analysis, and Potential Recommendations. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 16–33. [CrossRef]

- Moum, Anita & Hauge, Åshild & Thomsen, Judith. (2017). Dissecting the Average Shower and Its Impact on the Planet: An Invitation to Collaborate — Part One: Human Water Usage and Global Impact. Journal of Sustainability Education. 2020 Available online: URL https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322337558_Four_Norwegian_Zero_Emission_Pilot_Buildings_-_Building_Process_and_User_Evaluation. (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Vaičiūnas, J.; Geležiūnas, V.; Valančius, R.; Jurelionis, A.; Ždankus, T. Analysis of Drain Water Heat Exchangers and Their Perspectives in Lithuania. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering 2017, 17, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Passchier, C.W.; Valipour, M.; Krasilnikoff, J.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Sürmelihindi, G.; Baba, A.; Kumar, R.; Haut, B.; et al. Sustainability of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: From Prehistoric Times to the Present Times and the Future. Water 2023, 15, 1614. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. A Critical Review on the End Uses of Recycled Water. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2013, 43, 1446–1516. [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, C.; Kuski, L.; Moura, P.; Caetano, N. Water Consumption Monitoring System for Public Bathing Facilities. Energy Procedia 2018, 153, 408–413. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.E.-W. The Role of Smart Systems in Conservation on Sustainability of Heritage Buildings. Mansoura Engineering Journal 2024, 49. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).