Submitted:

08 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

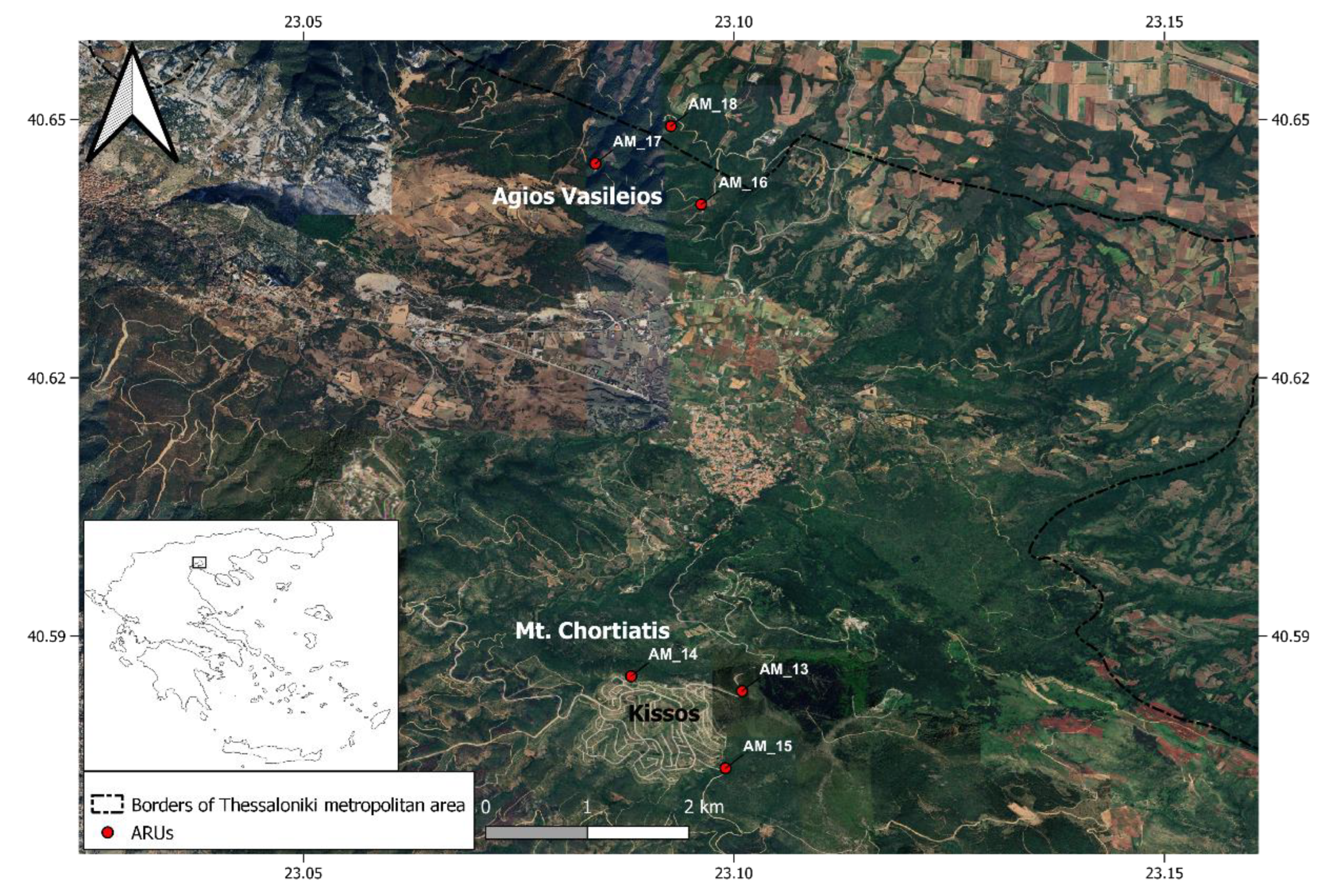

2.1. Study Sites and Fieldwork

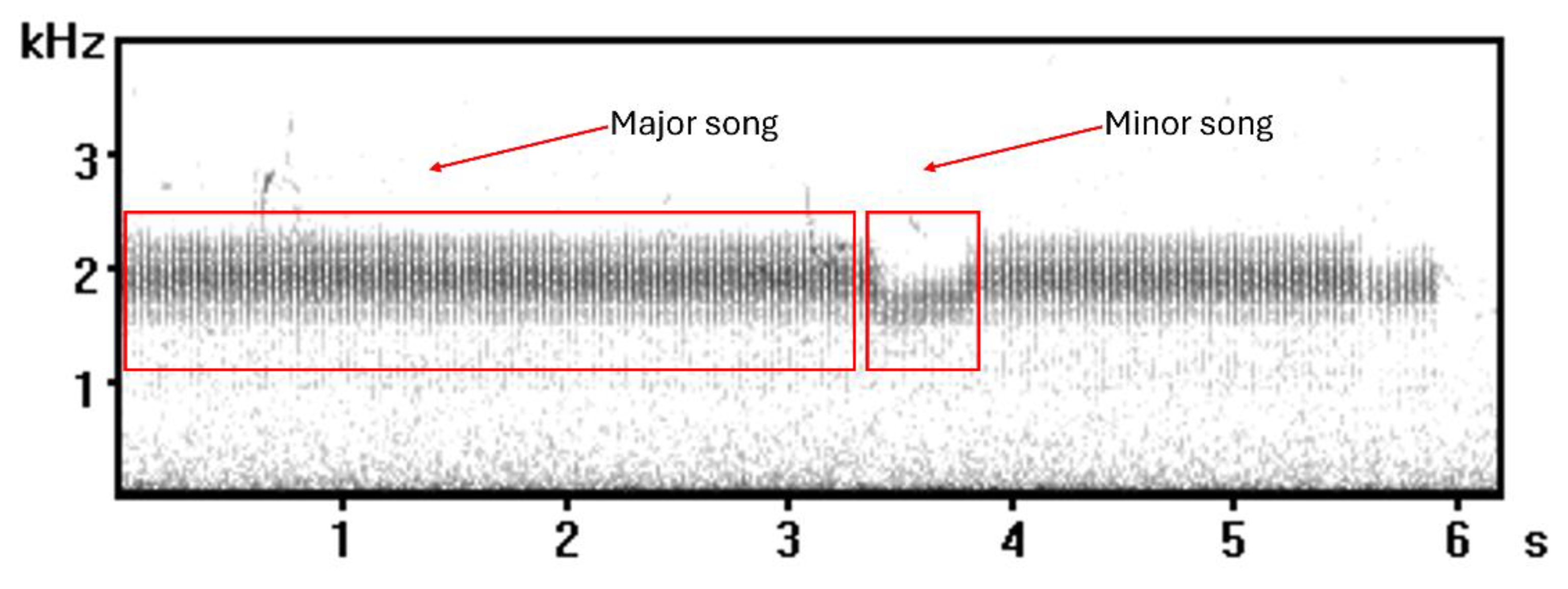

2.2. Acoustic Analysis

2.2. Statistical Analyses

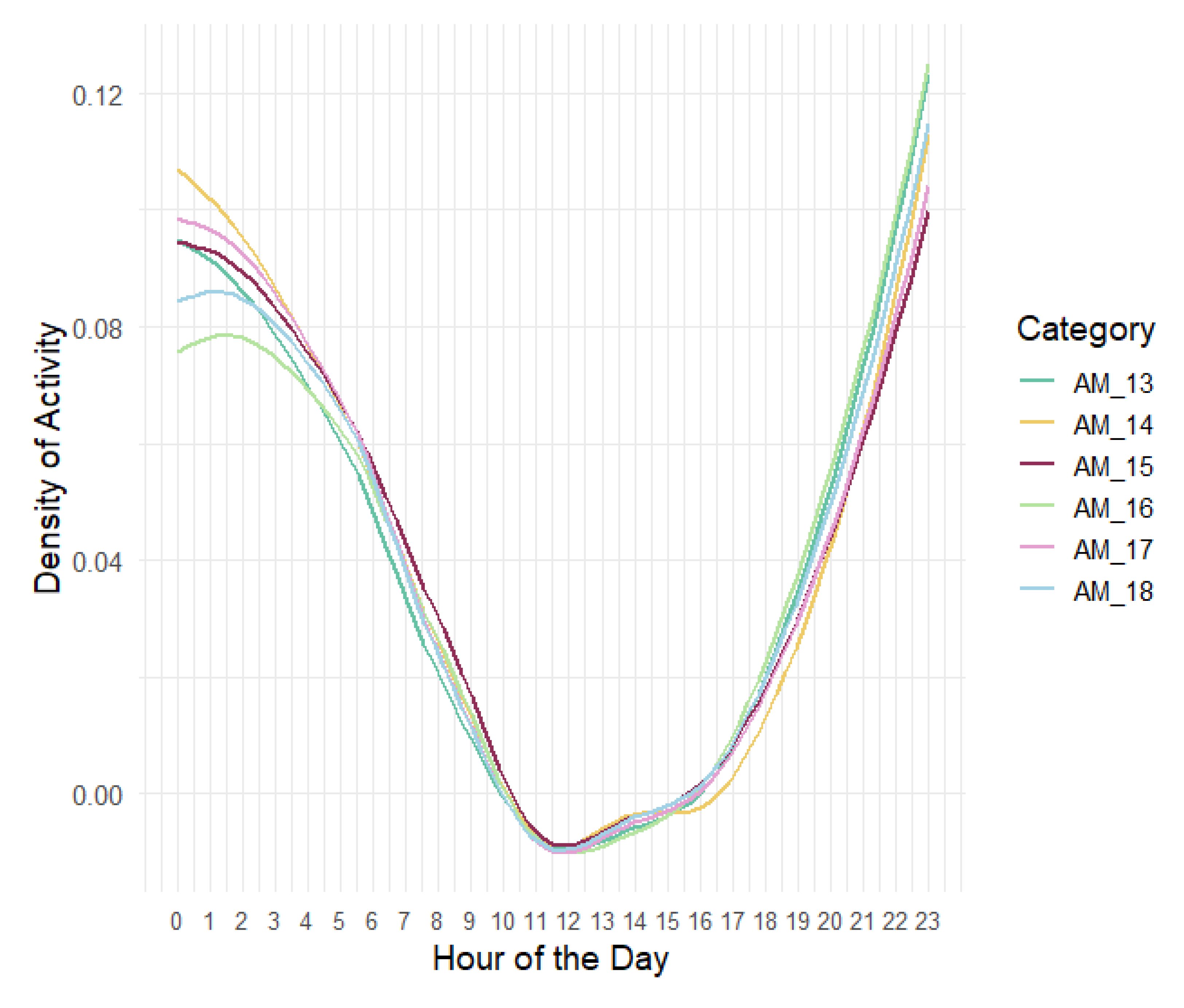

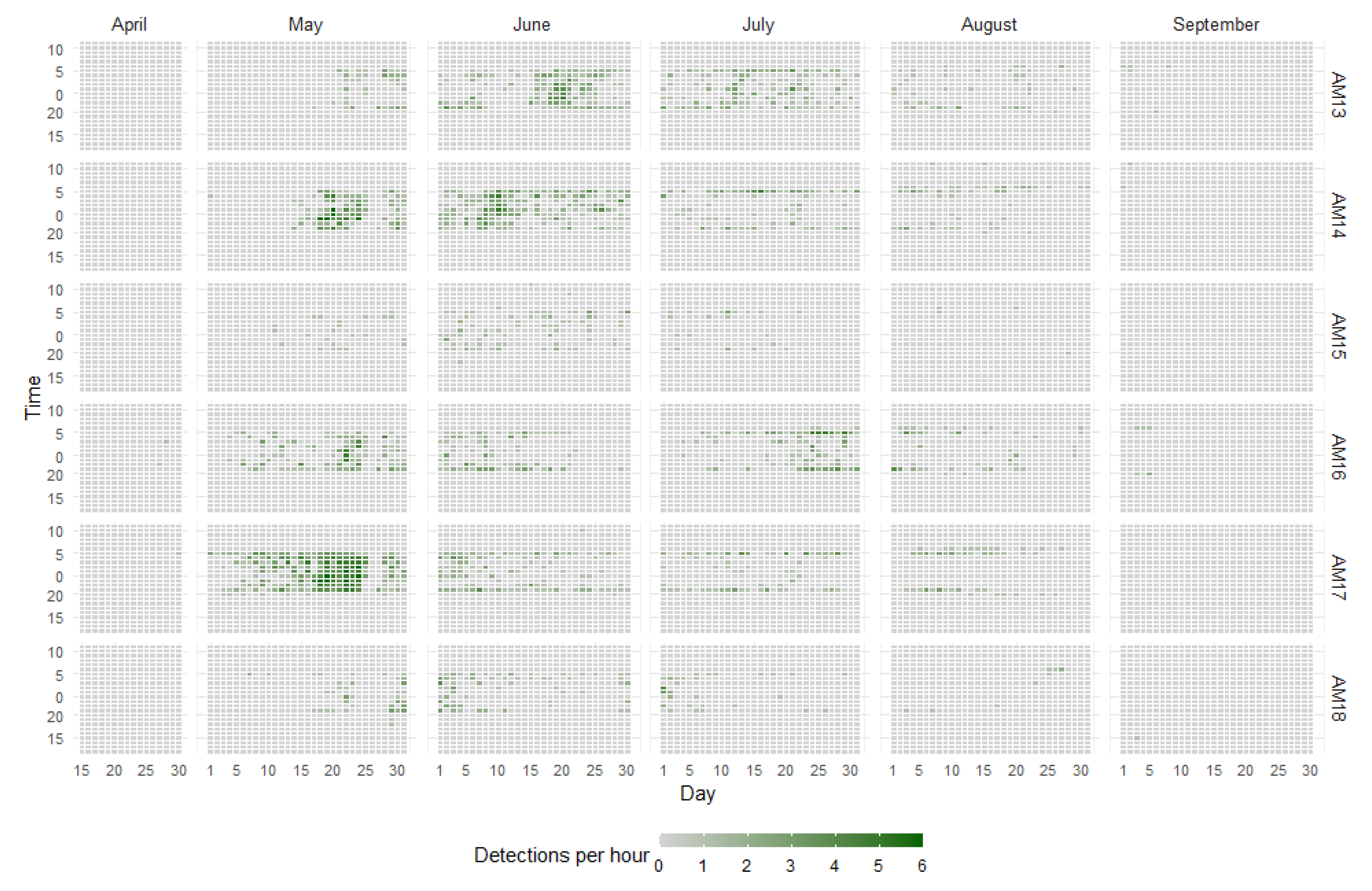

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | AIC score | ΔAIC score |

|---|---|---|

| Humidity | - 1635.716 | 0 |

| Temperature Min | - 1622.213 | 13.503 |

| Temperature Mean | - 1620.230 | 15.486 |

| Wind gust | - 1616.328 | 19.388 |

| Moon Phase | - 1614.372 | 21.345 |

| Temperature Max | - 1614.227 | 21.489 |

| Precipitation | - 1609.066 | 26.650 |

| Illuminocity index | - 1608.762 | 26.954 |

| Cloud cover | - 1608.300 | 27.416 |

| Baseline model | - 1607.721 | 27.995 |

| Windspeed | - 1606.082 | 29.634 |

| Locality | - 1605.890 | 29.826 |

| Dew | - 1605.741 | 29.975 |

| Sensor | April | May | June | July | August | September | October |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kissos: | |||||||

| AM13 | 0 | 56 | 232 | 181 | 49 | 5 | 0 |

| AM14 | 0 | 215 | 314 | 105 | 64 | 2 | 0 |

| AM15 | 0 | 23 | 88 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Ag. Vasileios: | |||||||

| AM16 | 2 | 179 | 110 | 149 | 59 | 6 | 0 |

| AM17 | 1 | 552 | 152 | 90 | 62 | 0 | 0 |

| AM18 | 0 | 56 | 89 | 37 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

References

- Catchpole, C. K.; Slater, P. J. B. Bird Song: Biological Themes and Variations, 2nd ed; Cambridge university press: NY, USA, 2008; 93-158.

- Oñate-Casado, J.; Porteš, M.; Beran, V.; Petrusek, A.; Petrusková, T. Guess Who? Evaluating Individual Acoustic Monitoring for Males and Females of the Tawny Pipit, a Migratory Passerine Bird with a Simple Song. J Ornithol 2023, 164, 845-858. [CrossRef]

- Petrusková, T.; Pišvejcová, I.; Kinštová, A.; Brinke, T.; Petrusek, A. Repertoire-Based Individual Acoustic Monitoring of a Migratory Passerine Bird with Complex Song as an Efficient Tool for Tracking Territorial Dynamics and Annual Return Rates. Methods Ecol Evol 2016, 7, 274-284. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Abenza, M.; Kraft, F.-L.H.; Ma, L.; Rajan, S.; Wheatcroft, D. Responses in Adult Pied Flycatcher Males Depend on Playback Song Similarity to Local Population. Behavioral Ecology 2024, 36, arae090. [CrossRef]

- Pipek, P.; Petrusková, T.; Petrusek, A.; Diblíková, L.; Eaton, M.A.; Pyšek, P. Dialects of an Invasive Songbird Are Preserved in Its Invaded but Not Native Source Range. Ecography 2018, 41, 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, S.; Nakadai, K.; Suzuki, R.; Ura, T.; Hasebe, M.; Okuno, H.G. Auditory Survey of Endangered Eurasian Bittern Using Microphone Arrays and Robot Audition. Front Robot AI 2022, 9, 854572. [CrossRef]

- Znidersic, E.; Watson, D.M.; Towsey, M.W. A New Method to Estimate Abundance of Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) from Acoustic Recordings. Avian Conserv Ecol 2024, 19, 16. [CrossRef]

- De Araújo, C.B.; Zurano, J.P.; Torres, I.M.D.; Simões, C.R.M.A.; Rosa, G.L.M.; Aguiar, A.G.; Nogueira, W.; Vilela, H.A.L.S.; Magnago, G.; Phalan, B.T.; et al. The Sound of Hope: Searching for Critically Endangered Species Using Acoustic Template Matching. Bioacoustics 2023, 32, 708-723. [CrossRef]

- Astaras, C.; Valeta, C.; Vasileiadis, I. Acoustic Ecology of Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) in the Greek Rhodope Mountains Using Passive Acoustic Monitoring Methods. Folia Oecologica 2022, 49, 110-116. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Mei, J.; Liu, F. Temporal Acoustic Patterns of the Oriental Turtle Dove in a Subtropical Forest in China. Diversity (Basel) 2022, 14, 1043. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C.; Schuchmann, K.L. Passive Acoustic Monitoring of Chaco Chachalaca (Ortalis canicollis) Over a Year: Vocal Activity Pattern and Monitoring Recommendations. Trop Conserv Sci 2021, 14, 19400829211058295. [CrossRef]

- Day, G.; Fox, G.; Hipperson, H; Maher, K. H.; Tucker, R.; Horsburgh, G. J.; Waters, D.; Durant, K. L.; Burke, T.; Slate, J.; Arnold, K. E. Revealing the Demographic History of the European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus). Ecol Evol 2024, 14, e70460. [CrossRef]

- Data Zone by BirdLife. Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/european-nightjar-caprimulgus-europaeus (accessed on 01/03/2025).

- Mitchell, L. J.; Kohler, T.; White, P. C. L.; Arnold K. E. High interindividual variability in habitat selection and functional habitat relationships in European nightjars over a period of habitat change. Ecol Evol 2020, 10, 5932-5945. [CrossRef]

- Sharps, K.; Henderson, I.; Conway, G.; Armour-Chelu, N.; Dolman, P.M. Home-Range Size and Habitat Use of European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus Nesting in a Complex Plantation-Forest Landscape. Ibis 2015, 157, 260-272. [CrossRef]

- Warman, S.R. Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, Volume V: Tyrant Flycatchers to Thrushes (Birds of the Western Palearctic). Trends Ecol Evol 1988, 3, 282-283. [CrossRef]

- Norevik, G.; Åkesson, S.; Hedenström, A. Migration Strategies and Annual Space-Use in an Afro-Palearctic Aerial Insectivore – the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. J Avian Biol 2017, 48, 738-747. [CrossRef]

- Cleere, N.; Christie, D.A.; Rasmussen, P.C. Eurasian Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), Version 1.1., Rasmussen, P.C., Ed.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cleere, N. Nightjars: A Guide to the Nightjars, Nighthawks, and Their Relatives, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 1998.

- Evens, R.; Beenaerts, N.; Witters, N.; Artois, T. Study on the Foraging Behaviour of the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus Reveals the Need for a Change in Conservation Strategy in Belgium. J Avian Biol 2017, 48, 1238-1245. [CrossRef]

- Evens, R.; Lathouwers, M.; Creemers, J.; Ulenaers, E.; Eens, M.; Kempenaers, B. A case of facultative polygyny in an enigmatic monogamous species, the European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus). Ecol evol 2024, 14, e70366. [CrossRef]

- Langston, R.H.W.; Liley, D.; Murison, G.; Woodfield, E.; Clarke, R.T. What Effects Do Walkers and Dogs Have on the Distribution and Productivity of Breeding European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus? Ibis 2007, 149, 27-36. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, L.B.; Jensen, N.O.; Willemoes, M.; Hansen, L.; Desholm, M.; Fox, A.D.; Tøttrup, A.P.; Thorup, K. Annual Spatiotemporal Migration Schedules in Three Larger Insectivorous Birds: European Nightjar, Common Swift and Common Cuckoo. Animal Biotelemetry 2017, 5, 4. [CrossRef]

- Norevik, G.; Åkesson, S.; Andersson, A.; Bäckman, J.; Hedenström, A. Flight Altitude Dynamics of Migrating European Nightjars across Regions and Seasons. Jour Exper Biology 2021, 224, jeb242836. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, B.; Edwards, D. Geolocators Reveal Wintering Areas of European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus). Bird Study 2013, 60, 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Norevik, G.; Åkesson, S.; Andersson, A.; Bäckman, J.; Hedenström, A. The Lunar Cycle Drives Migration of a Nocturnal Bird. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000456. [CrossRef]

- Jenks, P.; Green, M.; Cross, T. Foraging Activity and Habitat Use by European Nightjars in South Wales. British Birds 2014, 107.

- Mitchell, L. The influence of environmental variation on individual foraging and habitat selection behaviour of the European nightjar. Doctoral dissertation, University of York, Heslington, York, UK, 2019.

- Rebbeck, M.; Corrick, R.; Eaglestone, B.; Stainton, C. Recognition of Individual European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus from Their Song. Ibis 2001, 143, 468-475. [CrossRef]

- Docker, S.; Lowe, A.; Abrahams, C. Identification of Different Song Types in the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. Bird Study 2020, 67, 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Reino, L.; Porto, M.; Santana, J.; Osiejuk, T.S. Influence of Moonlight on Nightjars’ Vocal Activity: A Guideline for Nightjar Surveys in Europe. Biologia (Poland) 2015, 70, 968-973. [CrossRef]

- Evens, R.; Kowalczyk, C.; Norevik, G.; Ulenaers, E.; Davaasuren, B.; Bayargur, S.; Artois, T.; Åkesson, S.; Hedenström, A.; Liechti, F.; et al. Lunar Synchronization of Daily Activity Patterns in a Crepuscular Avian Insectivore. Ecol Evol 2020, 10, 7106-7116. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C.; Schuchmann, K.L.; Marques, M.I. Addicted to the Moon: Vocal Output and Diel Pattern of Vocal Activity in Two Neotropical Nightjars Is Related to Moon Phase. Ethol Ecol Evol 2022, 34, 66-81. [CrossRef]

- Gordo, O. Why Are Bird Migration Dates Shifting? A Review of Weather and Climate Effects on Avian Migratory Phenology. Clim Res 2007, 35, 37-58. [CrossRef]

- Cuchot, P.; Bonnet, T.; Dehorter, O.; Henry, P.Y.; Teplitsky, C. How Interacting Anthropogenic Pressures Alter the Plasticity of Breeding Time in Two Common Songbirds. Jour Animal Ecol 2024, 93, 918–931. [CrossRef]

- Prosser, D.J.; Teitelbaum, C.S.; Yin, S.; Hill, N.J.; Xiao, X. Climate Change Impacts on Bird Migration and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. Nat Microbiol 2023, 8, 2223-2225. [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Malanotte-Rizzoli, P.; Boscolo, R.; Alpert, P.; Artale, V.; Li, L.; Luterbacher, J.; May, W.; Trigo, R.; Tsimplis, M.; et al. The Mediterranean Climate: An Overview of the Main Characteristics and Issues. Develop Earth Envi Sci 2006, 4, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S.; Wood, C.M.; Eibl, M.; Klinck, H. BirdNET: A Deep Learning Solution for Avian Diversity Monitoring. Ecol Info 2021, 61, 101236. [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.C.; Hannah, K.C.; Foley, G.J.; Scott, C.D.; Brigham, R.M.; Bayne, E. Recommendations for acoustic recognizer performance assessment with application to five common automated signal recognition programs. Avian Conserv Ecol 2017, 12, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P.B., & Christensen, R.H.B. (2024). GlmmTMB: Generalized Linear Mixed Models Using Template Model Builder. R Package Version 1.1.2. https://CRAN.R-Project.Org/Package=glmmTMB.

- Astaras, C.; Linder, J.M.; Wrege, P.; Orume, R.; Johnson, P.J.; MacDonald, D.W. Boots on the Ground: The Role of Passive Acoustic Monitoring in Evaluating Anti-Poaching Patrols. Environ Conserv 2020, 47, 213-216. [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Statistical Theory and Numerical Results. In Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed; Springer: NY, USA, 2002; pp. 352–436. ISBN 978-0-387-22456-5.

- Bartoń, Kamil. (2024). MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R Package Version 1.48.4. https://CRAN.R-Project.Org/Package=MuMIn1.

- Wickham, M.H. Package “ggplot2” Type Package Title An Implementation of the Grammar of Graphics; 2014;

- Ashdown, R.A.M.; McKechnie, A.E. Environmental Correlates of Freckled Nightjar (Caprimulgus Tristigma) Activity in a Seasonal, Subtropical Habitat. J Ornithol 2008, 149, 615-619. [CrossRef]

- De Felipe, M.; Sáez-Gómez, P.; Camacho, C. Environmental Factors Influencing Road Use in a Nocturnal Insectivorous Bird. Eur J Wildl Res 2019, 65, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.C.; Abril-Colón, I.; Ucero, A.; Palacín, C. Precipitation and Female Experience Are Major Determinants of the Breeding Performance of Canarian Houbara Bustards. Wildlife Biol 2024, e01345. [CrossRef]

- Motegi, T.; Mizutani, K.; Wakatsuki, N. Simultaneous Measurement of Air Temperature and Humidity Based on Sound Velocity and Attenuation Using Ultrasonic Probe. Jpn J Appl Phys 2013, 52, 07HC05. [CrossRef]

- Digby, A.; Towsey, M.; Bell, B.D.; Teal, P.D. Temporal and Environmental Influences on the Vocal Behaviour of a Nocturnal Bird. J Avian Biol 2014, 45, 591-599. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, O.; Abrahams, C.; Ashington, B.; Baker, E.; Bradfer-Lawrence, T.; Browning, E.; Carruthers-Jones, J.; Darby, J.; Dick, J.; Eldridge, A.; Elliott, D.; Heath, B.; Howden-Leach, P.; Johnston, A.; Lees, A.; Meyer, C.; Ruiz Arana, U.; Smyth, S. Good Practice Guidelines for Long-Term Ecoacoustic Monitoring in the UK. The UK Acoustics Network 2023.

- Zwart, M.C.; Baker, A.; McGowan, P.J.K.; Whittingham, M.J. The Use of Automated Bioacoustic Recorders to Replace Human Wildlife Surveys: An Example Using Nightjars. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102770. [CrossRef]

- Eisenring, E.; Eens, M.; Pradervand, J. N.; Jacot, A.; Baert, J.; Ulenaers, E.; Evens, R. Quantifying Song Behavior in a Free-Living, Light-Weight, Mobile Bird Using Accelerometers. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12(1), e8446. [CrossRef]

- Roe, P.; Eichinski, P.; Fuller, R.A.; McDonald, P.G.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Towsey, M.; Truskinger, A.; Tucker, D.; Watson, D.M. The Australian Acoustic Observatory. Methods Ecol Evol 2021, 12, 1802-1808. [CrossRef]

| Site | Sensor | Algorithm detections | 1-min files with nightjar calls | Days with calls | Mean number 1-min files with calls per day (excl. inactive days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kissos | AΜ13 | 6,527 | 523 | 95 | 5.50 |

| AΜ14 | 3,939 | 700 | 104 | 6.73 | |

| AΜ15 | 2,888 | 137 | 58 | 2.36 | |

| Ag. Vasileios | AΜ16 | 6,064 | 505 | 98 | 5.15 |

| AΜ17 | 15,173 | 857 | 112 | 7.65 | |

| AΜ18 | 4,782 | 192 | 61 | 3.14 |

| Sensor | Date | Learning Detector | visual browsing | Recall Rate % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AΜ13 | 1 - 5/7/2024 | 17 | 19 | 89.5 |

| AΜ14 | 12 - 16/6/2024 | 46 | 62 | 74.2 |

| AΜ15 | 3 - 7/6/2024 | 21 | 23 | 91.3 |

| AΜ16 | 20 - 24/5/2024 | 76 | 107 | 71.0 |

| AΜ17 | 7 - 11/5/2024 | 69 | 77 | 89.6 |

| AΜ18 | 29/6- 3/7/2024 | 29 | 38 | 76.3 |

| Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | Adjusted SE | Z-value | Lower 95 % CI | Lower 95 % CI | Pr(>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 10.293 | 0.782 | 0.783 | 13.141 | 8.760 | 11.825 | < 0.001 *** |

| Humidity | 3.133 | 0.511 | 0.512 | 6.122 | 2.131 | 4.134 | < 0.001 *** |

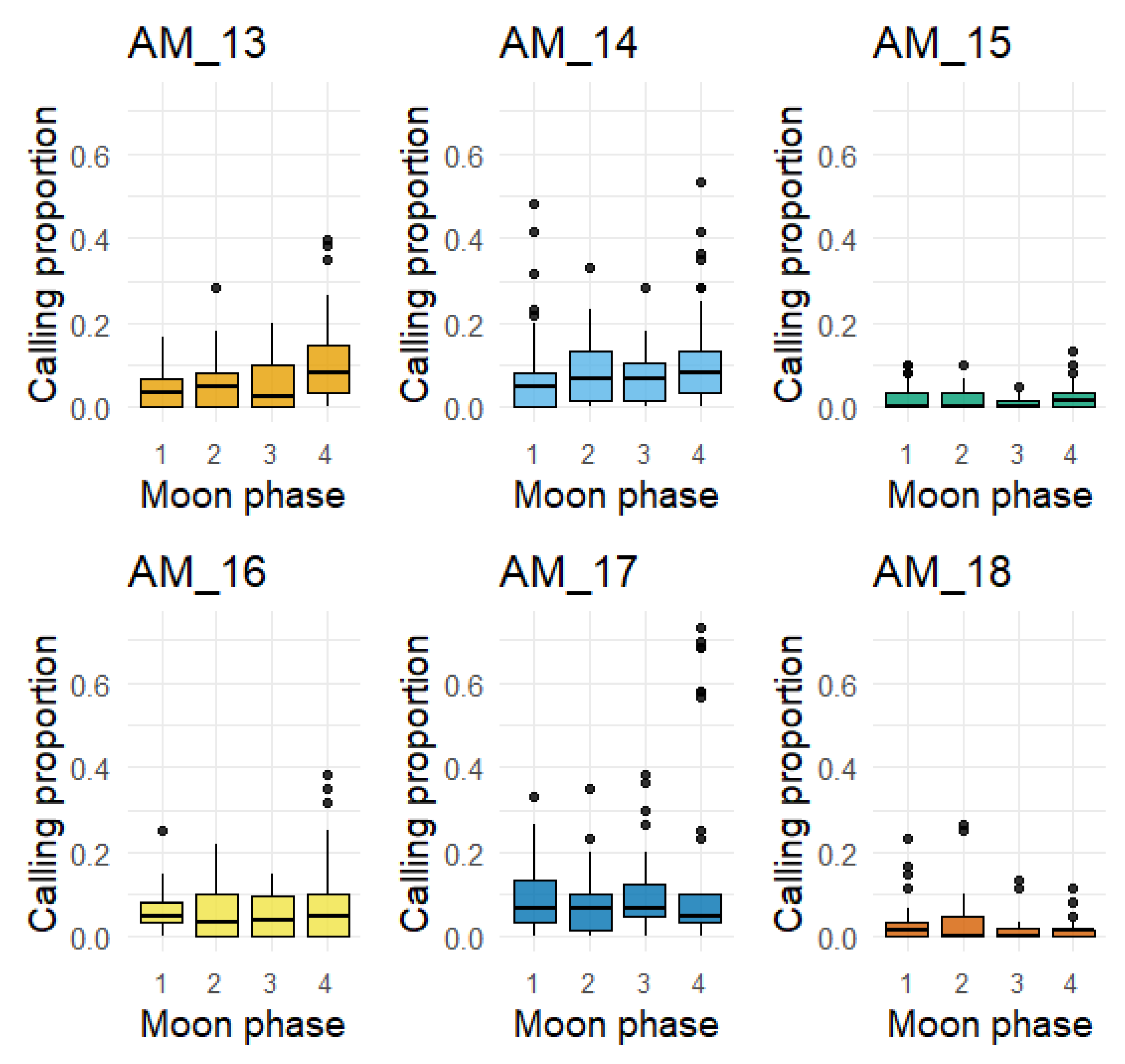

| Moon Phase | 0.265 | 0.107 | 0.107 | 2.474 | 0.055 | 0.474 | 0.013 * |

| Precipitation | - 1.761 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 4.401 | - 2.545 | - 0.977 | < 0.001 *** |

| Wind gust | - 0.342 | 0.312 | 0.313 | 1.095 | - 0.953 | 0.270 | 0.274 |

| Night duration | - 40.935 | 1.837 | 1.839 | 22.254 | - 44.535 | - 37.334 | < 0.001 *** |

| Temperature (Min) | - 0.021 | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.185 | - 0.244 | 0.202 | 0.853 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).