1. Introduction

The usage of biofuels made from biomass can partly replace fossil fuels and contribute towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Extensive research has delved into utilizing biomass such as wood, land-based, agricultural, and algae sources for bioenergy and biofuel applications. Early identified biomass, also referred to as first-generation biomass originated from consumable sources such as sugarcane, potatoes, soybeans, and palm oil [

6,

7,

8]. The initial iteration of biomass faced sustainability challenges primarily due to its competition with food and feed crops, potentially causing an escalation in food prices. Non-edible biomass, like lignocellulosic feedstock derived from agricultural and forest residue, emerged as a more promising alternative. Notably, lignocellulosic feedstock boasts higher yields compared to first-generation biomass. Nevertheless, its use for biofuel production presents significant drawbacks, including ecological concerns and the substantial land requirements to meet global biofuel demands [

9,

10].

Microalgae have garnered significant interest lately compared to other biomass sources since they do not compete directly with food or feed production. Compared to biomass derived from land, algae have a higher photosynthetic efficiency leading to faster growth rates and effective CO

2 removal. Cultivating algae on an extensive scale proves challenging considering the high production costs. This is one of the main challenges correlated with utilizing algae to produce an alternative energy source. On the other hand, the environmental conditions of its habitat, including salinity, light, temperature, pH, availability of nutrients, and water contamination, influence its growth rate and productivity [

11,

12,

13]. A substantial quantity of fertilizer and micronutrients are needed to cultivate algae. As a result, the water is enriched with an array of metals including iron, magnesium, zinc, silica, calcium, potassium, sodium, phosphorus, and other trace elements [

14,

15]. The presence of these metals in harvested algae makes it a challenge for direct combustion and gasification [

16]. The algae absorb these metals as they mature, thus increasing their ash content. Many research studies report that ash negatively impacts machinery and equipment in converting algae into biofuels, chemicals, and other bioproducts [

17,

18,

19]. The ash can deactivate the catalysts that cover the active sites or chemically interact with the catalyst material. The ash deposits can also insulate heat transfer surfaces, leading to uneven heating and inefficient thermal conversion of biomass. In addition, at high temperatures, the inorganic components in the ash can melt and form a sticky, molten slag. This slag can adhere to the walls and internal surfaces of the reactor, obstructing the flow of feedstock and gases. Besides, ash can contain corrosive elements like alkali metals (i.e., sodium, potassium, etc.) and chlorine, which can chemically react and corrode metal surfaces and other reactor materials. Thus, high temperatures accelerate ash generation during thermochemical reactions such as pyrolysis or gasification and lower the efficiency of the bioproducts that can be manufactured from algae amid conversion procedures [

20,

21].

Numerous treatments have been explored to eliminate physiological ash (containing essential minerals for growth) and non-physiological ash (containing non-essential minerals/contaminants). Jenkins et al. [

24] investigated the removal of inorganic components from the rice straw and wheat straw using water. Washing biomass with deionized water has proven effective for reducing ash, particularly non-physiological ash (soil). The non-physiological ash is easier to remove compared to the physiological ash because they are directly attached to the structure of the algae [

23]. Turn et al. [

24], explored using distilled water to remove approximately 40% ash from switchgrass. Key factors considered for effective ash removal included the biomass-to-water ratio, the temperature of the water, and the contact time of the biomass to the water [

25]. Conversely, other research groups have examined the integration of weak and strong acids, and the results effectively removed the ash content from the biomass. The following authors, Stylianos et al. [

26], Yoo et al. [

27], and Liu and Bi [

28], revealed that applying nitric acid can significantly reduce the ash percentage in biomass. Despite reports that acid is effective in removing inorganic materials, its application has adverse effects on biomass including the breakdown of certain organic components of the biomass and the generation of a waste stream that may require neutralization and safe handling of effluents [

29].

An alternative approach involves the application of chelating agents which have recently garnered significant attention due to their active interaction with metal ions, altering their solubility within algae. Chelating agents typically extract inorganic metals from biomass because they coordinate with two or more electron-donating atoms, allowing them to form complex bonds with a single metal atom. The most frequently utilized chelating agents include ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), citric acid, and nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA). Edmunds et al. [

30], examined the application of EDTA for producing a low-ash bioenergy feedstock. A significant concern highlighted was the environmental impact of repeated EDTA usage since it is a non-biodegradable chelating agent. Wang et al. [

31], NTA acts as a chelating agent to bind and remove metal ions from algal biomass contributing to ash content. According to Biller and Ross [

32], NTA treatment can improve biofuel yield from algal biomass by reducing ash content.

This study focuses on developing an ash removal process using NTA from three distinct algae species containing low, medium, and very high ash contents. Two benthic algal polyculture species that grow in planktonic form (Solid-State Algal Turf Scrubber and Green Algal Turf Scrubber) and the Scenedesmus sample were chosen for different treatment conditions. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of NTA and deionized water treatments and to understand the role of temperature in deashing algae biomass. One of the paramount focuses was to learn about the impact of these treatments on the algal biomass composition, which is important for converting it to biofuels. Several analytical techniques including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, high-pressure liquid chromatography, total organic carbon (TOC) and nitrogen (TN), ultimate analysis, and Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) were used in this study to understand the % ash removal, metals extraction, and changes in algae biomass composition before and after NTA treatment. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no published data on the effectiveness of NTA on three different types of algae which represent a wide range (low, medium, and high) of ash contents. The findings are aimed at bringing out new knowledge on the applicability of a biodegradable chelating agent in ash removal from algae and their regeneration for developing a close-loop environmentally benign ash removal system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Nitrilotriacetic acid (C6H9NO6, 99 %), sodium sulfide (Na2S, 98 %), calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2, 95 %), Hydrosulfuric acid (H2SO4, 99 %), reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Solutions, American Elements, ThermoFisher Scientific, and Fisher Scientific, respectively. Sandia National Laboratories provided three algal samples: two benthic algae polyculture species that grow in planktonic form (Solid-State Algal Turf Scrubber (ATS) and Green ATS), along with Scenedesmus sample. Six algae samples were collected, consisting of three duplicate pairs. These samples were left at room temperature overnight.

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The infrared spectra (400-4000 cm-1) were utilized to examine the functional groups of algae samples. Before analysis, the samples were finely ground and then dried at 60 °C for 24 hours. For each sample, approximately 0.05-0.07 g of the dried material was placed on the diamond surface of the instrument (Agilent Technologies Cary 630 FTIR) and pressed against the zinc crystal using a rod. Spectral data were collected using the 300 background scans coupled with the attenuated total reflection (ATR) method to obtain rapid molecular information while preserving the integrity of the samples, which remained intact after analysis.

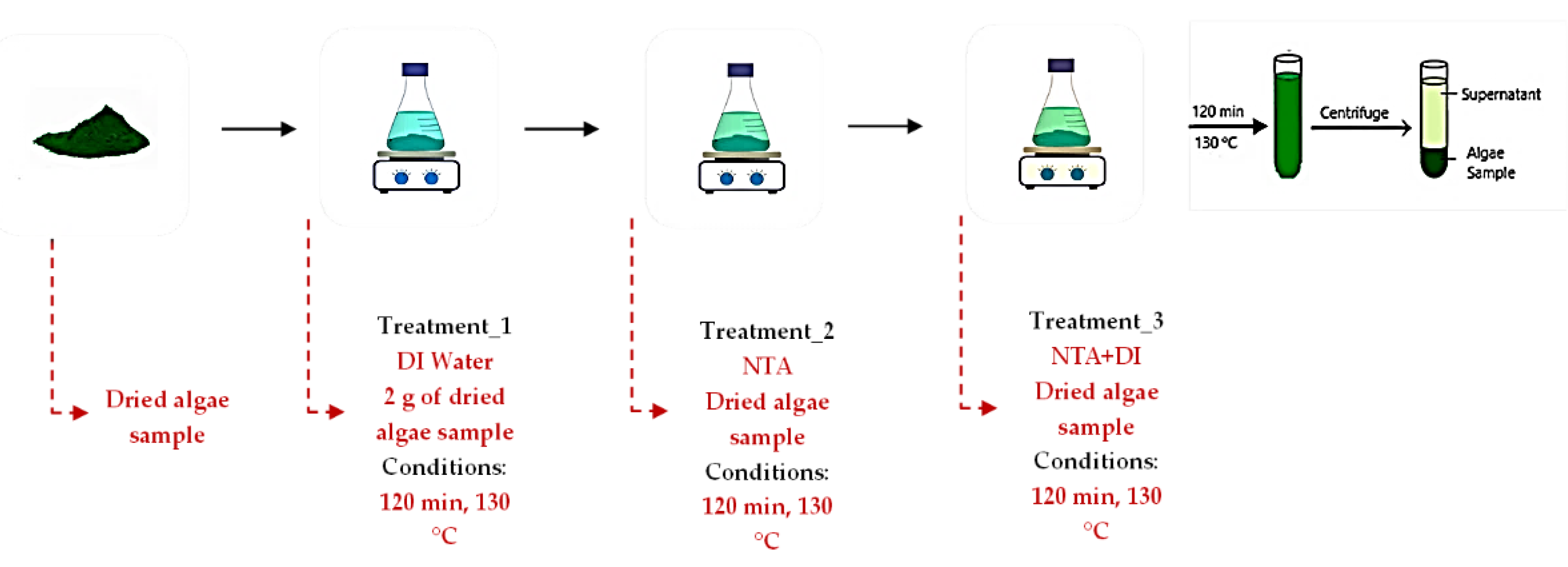

2.3. Ash Treatment

2 g of each algae sample was weighed and placed in an oven at a temperature of 60 °C. Upon cooling, the dried samples were added to 100 mL of deionized water and stirred on a metal plate for 2 hours to eliminate non-structural ash/inorganics not bound to the algae structure before introduction to the chelating acid solution (0.05M NTA). Each test tube was vortexed to enhance solid extraction. After centrifugation at 4000 x

g for 10 min, the supernatant was stored for instrumental evaluation whereas the solid extract was placed in an oven at 60 °C for further treatment as shown in

Figure 1.

The pre-treated algae sample was then added to 100 mL of 0.05M NTA solution and stirred for 120 minutes. The suspension was centrifuged, and the recovered algae was dried at 50 °C for 24 hours. The final step of the chelation extraction involves thoroughly washing the samples with 100 mL of deionized water, centrifuged, and dried at 60 °C for 24 hours. In this study, five reaction temperatures (90, 100, 110, 120, and 130 °C) were tested to ensure the effective removal of inorganic components from algae without exceeding the degradation temperature of 170 °C for the chelating acid. After each treatment, the algae samples underwent ash analysis using the dry oxidation method 575±25 °C, following the ‘Determination of Total Solids and Ash in Algal Biomass’ Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP) developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [

33].

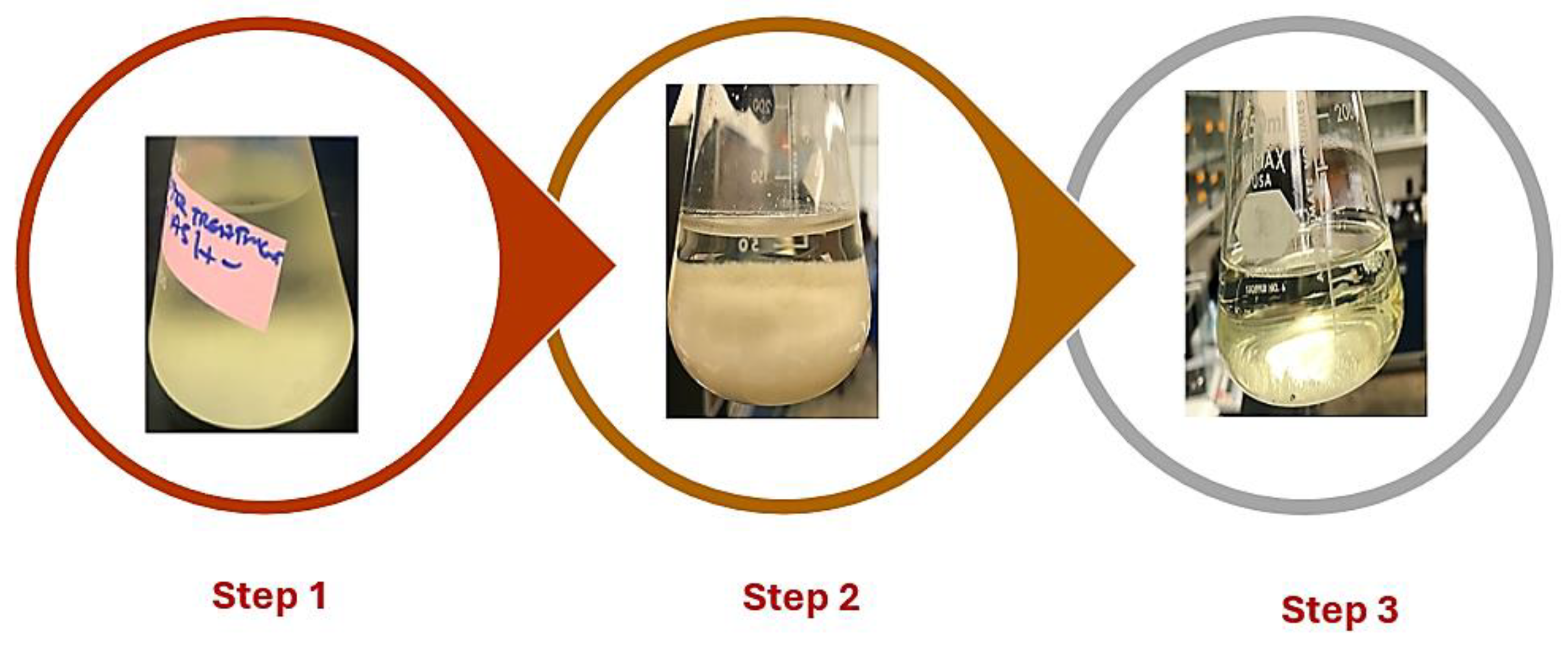

2.4. Stages for Nitrilotriacetic Acid Recycling

Recycling NTA for ash removal from algae was carefully designed to optimize ash reduction while allowing the reuse of the NTA solution. Initially, 2 g of deionized-treated algae biomass was introduced into 100 mL of NTA solution within a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. This mixture was stirred at a constant speed of 200 rpm using a magnetic stirrer for 2 hours at 130 °C. The high temperature and stirring conditions were intended to enhance the interaction between the algae and NTA, promoting ash dissolution and metal chelation (Step 1).

The mixture was centrifuged after this treatment to separate the algae from the NTA solution. The supernatant, rich in dissolved trace metals, was carefully transferred to a clean flask for further processing. The algae pellet was reserved for drying and subsequent analysis. To remove trace metals from the recovered NTA solution, 0.05 M Na2S was gradually introduced while continuously stirring. The addition of Na2S caused the precipitation of trace metals as sulfides, an essential step in regenerating the NTA solution for reuse. 5 mL of 0.1 M Ca(OH)2 was added to the mixture to further improve the precipitation process. This adjustment enhanced the efficiency of trace metal removal by facilitating the aggregation of metal sulfide particles. The mixture was left undisturbed under a fume hood overnight to ensure complete precipitation (Step 2).

Finally, the supernatant containing the regenerated NTA was carefully extracted with a syringe and transferred to a separate flask for reuse. To restore the solution to optimal conditions for algae treatment, its pH was adjusted from 10.5 to 4.5 by gradually adding 10% HNO3. This pH adjustment ensured the NTA solution was ready for subsequent cycles of algae treatment (Step 3).

The effectiveness of the process was evaluated through total ash analysis, which was conducted following the laboratory analytical procedure developed by the NREL

33. The summary of the NTA recycling process is presented in

Figure 2 while the ash content in the algae for each treatment was computed using Equation 1.

where: measured weight of the treated sample (

), measured weight of the recovered sample (

), initial ash content/100 (

), final ash content after treatment/100 (

).

2.5. Ultimate Analysis

The chemical composition of the algae samples was analyzed using standardized methods. These analyses included: the quantification of total organic carbon, total nitrogen, moisture content, oven dry weight (ODW), and protein content. Thus, the algae samples were treated with DI water followed by NTA and DI water at 130 °C for 2 hours. Ash analyses were conducted on both the raw and treated algae samples. The NTA solution saturated with ash was regenerated using Na2S with Ca(OH)2. The regenerated solution was recycled for subsequent ash removal cycles.

The elemental composition of the algae samples was determined at various stages of treatment, including the untreated state, using a Flash 2000 Organic Elemental Analyzer with the CHNS module. This analysis directly quantified the carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), and sulfur (S) content. In contrast, the oxygen content was computed by subtracting the sum of these elements from the total sample mass.

To ensure reliability and statistical significance, all samples were thoroughly dried by placing them in an oven at 60 °C for 24 hours before analysis and each analysis was performed in triplicate. This drying step was crucial for obtaining measurements on a dry basis, eliminating any potential interference from moisture content. This analytical technique provided a comprehensive profile of the elemental changes occurring throughout the treatment process, offering valuable insight into the effectiveness of each stage and the overall transformation of the algae biomass.

2.6. Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

The inorganic elemental composition of the algae samples at various treatment stages was analyzed using AA-7000 Shimadzu Flame AAS. The procedure involved adding 250 µL of 72% (w/w) H2SO4 to 0.025 g of dried algae in a glass tube. The mixture was then incubated in a 30 °C water bath for an hour and vortexed every 10 minutes to ensure proper mixing. Subsequently, 7 mL of ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ) was introduced to dilute the sulfuric acid concentration to 4% (w/w). The prepared samples were placed in an autoclave-compatible rack and subjected to a 121 °C sterilization cycle. After an hour of cooling, the samples were filtered through a 0.22 µm filter with a disposable syringe. The filtered samples were then stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for more than 24 hours before undergoing inorganic elemental analysis.

2.7. Total Carbon (TC) and Total Nitrogen (TN) Determination

The determination of Total Carbon (TC) and Total Nitrogen (TN) in the supernatant was conducted using a Shimadzu Total Organic Carbon Analyzer (TOC-VCSN) coupled with a Shimadzu Total Nitrogen Measuring Unit (TNM-1). Before the analysis, the TC analyzer and TN measuring unit were calibrated using standard solutions prepared according to manufacturer specifications. The liquid sample was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane to remove particulates and placed into autosampler vials for automated injection. The Shimadzu TOC-VCSN analyzer uses a high-temperature combustion catalytic oxidation method to break down organic compounds in the sample into carbon dioxide (CO2). The generated CO2 was detected using a non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) detector providing the TC in the sample.

For TN analysis, the TNM-1 module facilitated the measurement of nitrogen content by utilizing catalytic oxidation followed by chemiluminescence detection. During this process, nitrogen-containing compounds in the sample were oxidized to nitrogen monoxide (NO) at high temperatures in the presence of a catalyst. The generated NO was detected using chemiluminescence, and the TN concentration was quantified. Quality control measures, such as periodic analysis of blank samples and certified materials, were employed to validate the accuracy and precision of the results.

2.8. Protein and Sugar Concentration Determination

Determining protein content in the supernatant was conducted using the nitrogen-to-protein conversion approach, which incorporates specific nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors (N-factor) developed by NREL ‘Determination of Protein Content’ [

34]. The N-factor accounts for variations in nitrogen composition within the biomass, including the proportion of non-protein compounds such as nucleic acids and other nitrogenous metabolites.

The TN content (%N) was determined using a Shimadzu Total Nitrogen Measuring Unit (TNM-1) attached to a Shimadzu Total Organic Carbon Analyzer (TOC-VCSN) as described in the preceding subsection. After determining the %N, the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor specific to the algae species was selected. Thus, the protein content was computed using Equation 2.

where: %N represents the percentage of nitrogen in the sample, and N-factor represents the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor specific to the biomass type.

For sugar determination, ‘Determination of Total Carbohydrates in Algal Biomass’

LAP-NREL procedure was followed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a refractive index detector [

35]. Individual sugars, such as glucose, mannose, arabinose, and galactose, were separated in the HPLC column based on their retention times and quantified by comparison with standard sugar solution.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR Analysis of Raw and Treated Algae

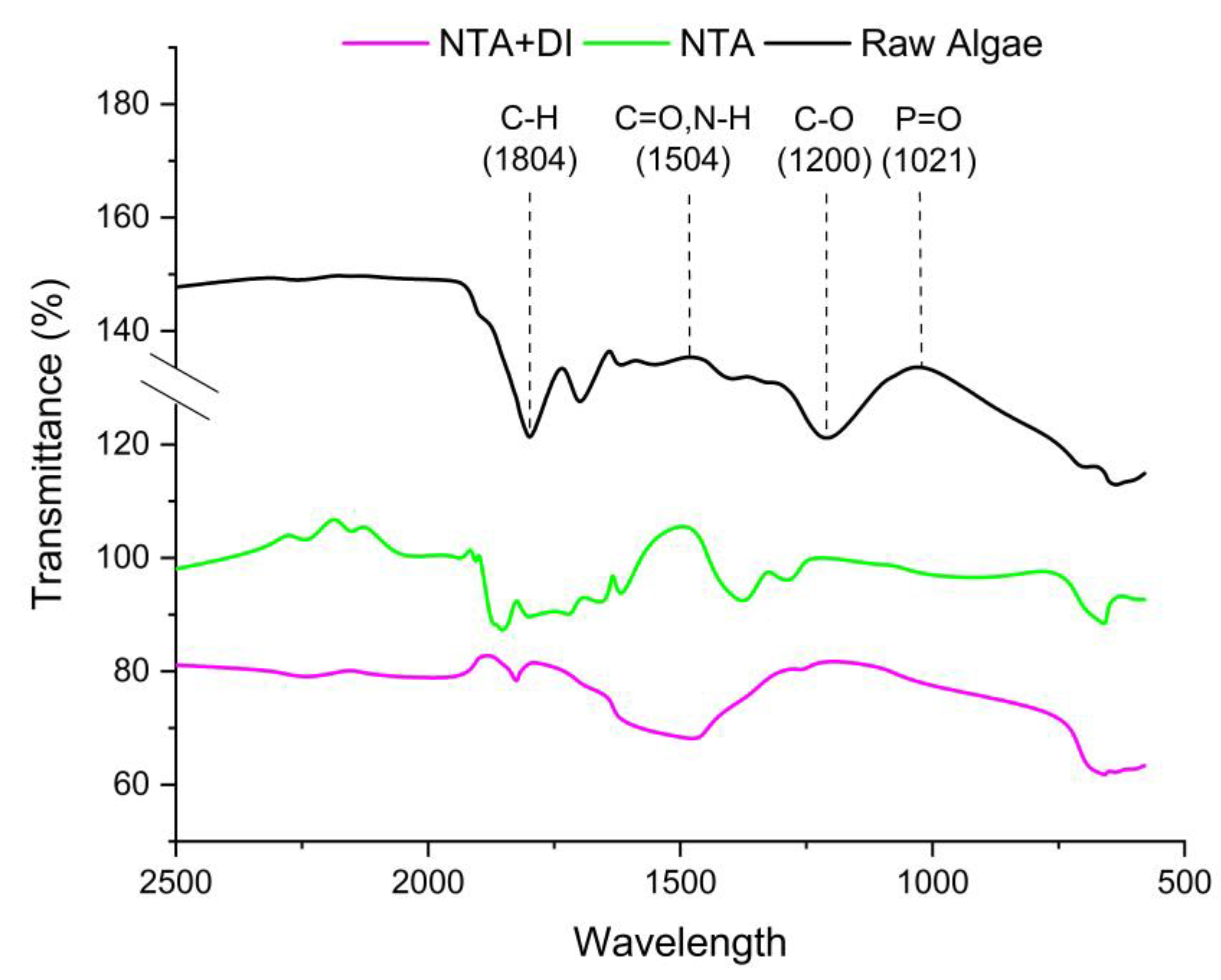

The FTIR spectra in

Figure 3 display the transmittance of raw and treated

Scenedesmus algae samples with NTA and NTA+DI. The results revealed the C-H stretching (1804 cm

-1) peaks indicate the presence of aliphatic chains, likely from lipids, and fatty acids in the algal biomass. However, a slight reduction in intensity could indicate degradation or modification of lipid structures during treatment. Further reduction suggests a continued breakdown or removal of lipid-like substances during the combined treatment.

The strong peak in the raw sample at 1504 cm-1 is characteristic of carbonyl groups (C=O) in proteins (amide I band), lipids, and carbohydrates. Notwithstanding, this peak could be associated with the N-H bending vibrations of proteins (amide II band). The shift or reduction in peak intensity suggests chelation or interaction of NTA with carbonyl groups, possibly altering protein structure or binding to carboxylates. The NTA+DI treatment enhances this effect, as further removal of cell-wall-bound minerals and organic components occurs, aligning with the significant reduction in ash content in the raw algae sample.

The peaks at 1200 cm-1 (C-O stretching) and 1021 cm-1 (P=O stretching) are associated with polysaccharides and phosphates, respectively, and exhibit a notable reduction in intensity after each treatment stage. In raw algae, these peaks are strong due to structural polysaccharides and phosphate-containing compounds. Post-NTA treatment causes a decrease in intensity, signifying the chelation of metal-phosphate complexes and partial removal of polysaccharides. The NTA+DI treatment further reduces these peaks, highlighting the combined efficiency in breaking down the cell wall and removing phosphate minerals, which are key ash-forming components

3.2. Ash Content and Removal Efficiency Analysis

Removing ash from algae is critical in enhancing its potential for bioenergy or biochemical production. In this study, NTA was used as a chelating agent to selectively remove ash from three (3) different algae samples: high ash (SS ATS), medium ash (Green ATS), and low ash (Scenedesmus). The use of NTA for ash removal in the algae samples yielded varying degrees of success as shown in

Table 1.

The NTA treatment resulted in only a modest reduction in ash content for SS ATS (≈ 2.8%). This limited effectiveness suggests that SS ATS may have a high concentration of non-metallic or refractory ash components (e.g., silicates, oxides, or sulfates) that NTA, primarily chelates metal ions, could not effectively target. In addition, the ash in SS ATS could consist of more stable metal oxides (e.g., aluminum oxides or iron oxides) that are difficult to chelate under normal NTA conditions, reducing the efficiency of ash removal. [

36]. The dense structure of SS ATS may have hindered the penetration of NTA into the biomass matrix, limiting its ability to access and chelate metals bound within the structure [

37].

The Green ATS showed a moderate reduction in ash content (approximately 8.7%). The results suggest that NTA was more effective in chelating ash-forming metals from this sample than SS ATS, likely because a higher proportion of metal oxides or metal ions such as calcium, magnesium, or ions are more susceptible to removal by NTA. The structural properties of Green ATS, potentially offering better surface exposure to ash, may also have contributed to greater effectiveness. Notwithstanding, the reaction time or NTA concentration may not have been optimal for fully chelating the metal ions present in Green ATS, leading to only partial ash removal. Thus, prolonging the treatment or increasing NTA concentration could enhance the removal efficiency [

32,

40]. The organic compounds or other components in Green ATS could have interfered with the effectiveness of NTA, competing for the chelating sites and reducing its ability to target metal ions effectively.

Moreover,

Scenedesmus exhibited a dramatic reduction in ash content from 15.2% to 3.8%, indicating a removal efficiency of 75%. The effectiveness of NTA, in this case, could be attributed to the low initial ash content compared to the other two samples, which likely consisted of more readily chelatable metal ions (e.g., calcium, magnesium). NTA is highly effective in removing these ions leading to significant ash reduction [

39]. Since

Scenedesmus has a relatively low initial ash content, most of the ash is likely in the form of metal salts or oxides that are more reactive with NTA resulting in efficient chelation and removal [

42,

43]. Besides, the structure of

Scenedesmus may have allowed better penetration of NTA, increasing its effectiveness in targeting and removing ash-forming components.

Scenedesmus was selected for thorough evaluation in this study based on its significant ash reduction after NTA treatment. This is associated with relatively high ash removal efficiency, making it an ideal candidate for further analysis to optimize the ash removal process and understand the underlying mechanisms contributing to its effectiveness.

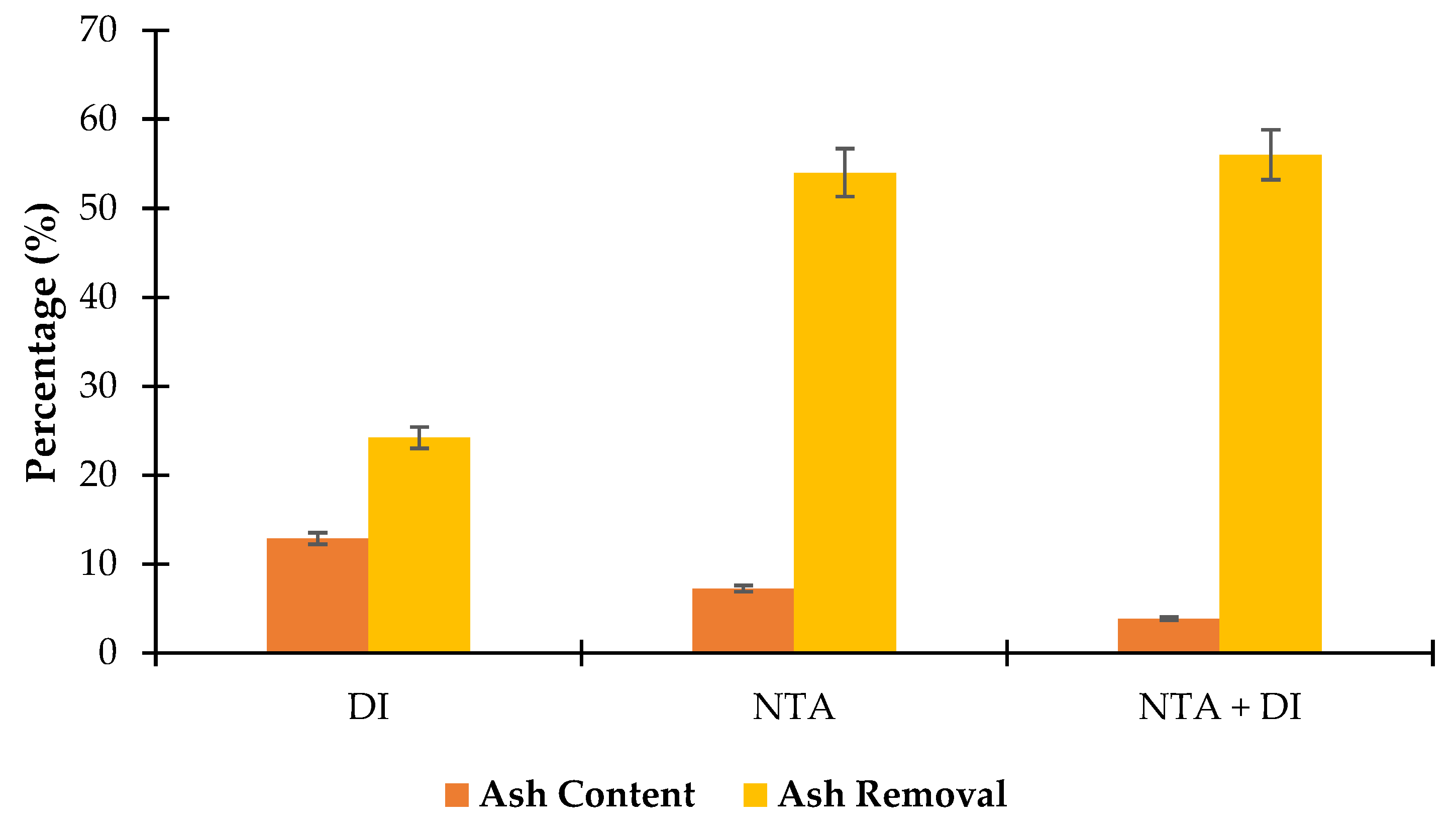

3.2.1. Ash Removal Efficiency for Each Treatment Stage

The study evaluated the effectiveness of three ash removal treatment stages for

Scenedesmus algae: stage 1 (Deionized water, DI), stage 2 (Nitrilotriacetic acid, NTA), and stage 3 (NTA followed by DI rinse, NTA + DI).

Figure 4 presents the results as ash content percentages and the corresponding ash removal efficiencies reveal the varying impacts of each treatment stage at 130 ℃.

The DI treatment effectively reduced ash content by approximately 24.2%. This initial reduction may result from the solubilization of easily removable inorganic compounds, particularly water-soluble salts (e.g., sodium, potassium) and loosely bound ash particles. However, the limited effectiveness suggests that a significant portion of the ash content may consist of metallic oxides or non-water-soluble components, which require stronger chelating agents for removal. This stage is preparatory, effectively removing surface-bound ash but not targeting deeply embedded or more chemically stable ash components.

The NTA treatment markedly increased ash removal, with an efficiency of 54%. NTA as a chelating agent, selectively binds to metal ions such as calcium, magnesium, and iron, forming soluble complexes that can be removed from the algae matrix. This significant decrease in ash content indicates that NTA effectively targets ash-forming metal ions that DI alone could not remove. The reduction also suggests that a large fraction of the algae ash is composed of metal oxides or carbonates, which are susceptible to chelation. This stage demonstrates the enhanced ash removal capability of NTA over DI, as it can access and bind metal ions within the cellular structure of the algae.

Following the NTA treatment with additional DI rinse resulted in final ash content of 3.83%, corresponding to an overall ash removal efficiency of 56%. This additional DI rinse removes residual ash components and loosely bound NTA-metal complexes that may remain within the algae. The marginal increase in ash removal (2% over the NTA treatment phase) suggests that DI rinsing may primarily aid in flushing out residual or weakly bound ash particles that the initial NTA chelation did not completely solubilize. This synergy approach maximizes ash removal, indicating that a post-chelation DI rinse can provide a finishing effect to remove residual ash effectively. This sequential approach can improve the quality of algae feedstocks for biofuel production by reducing inorganic impurities that can impact downstream process efficiency [

44,

45].

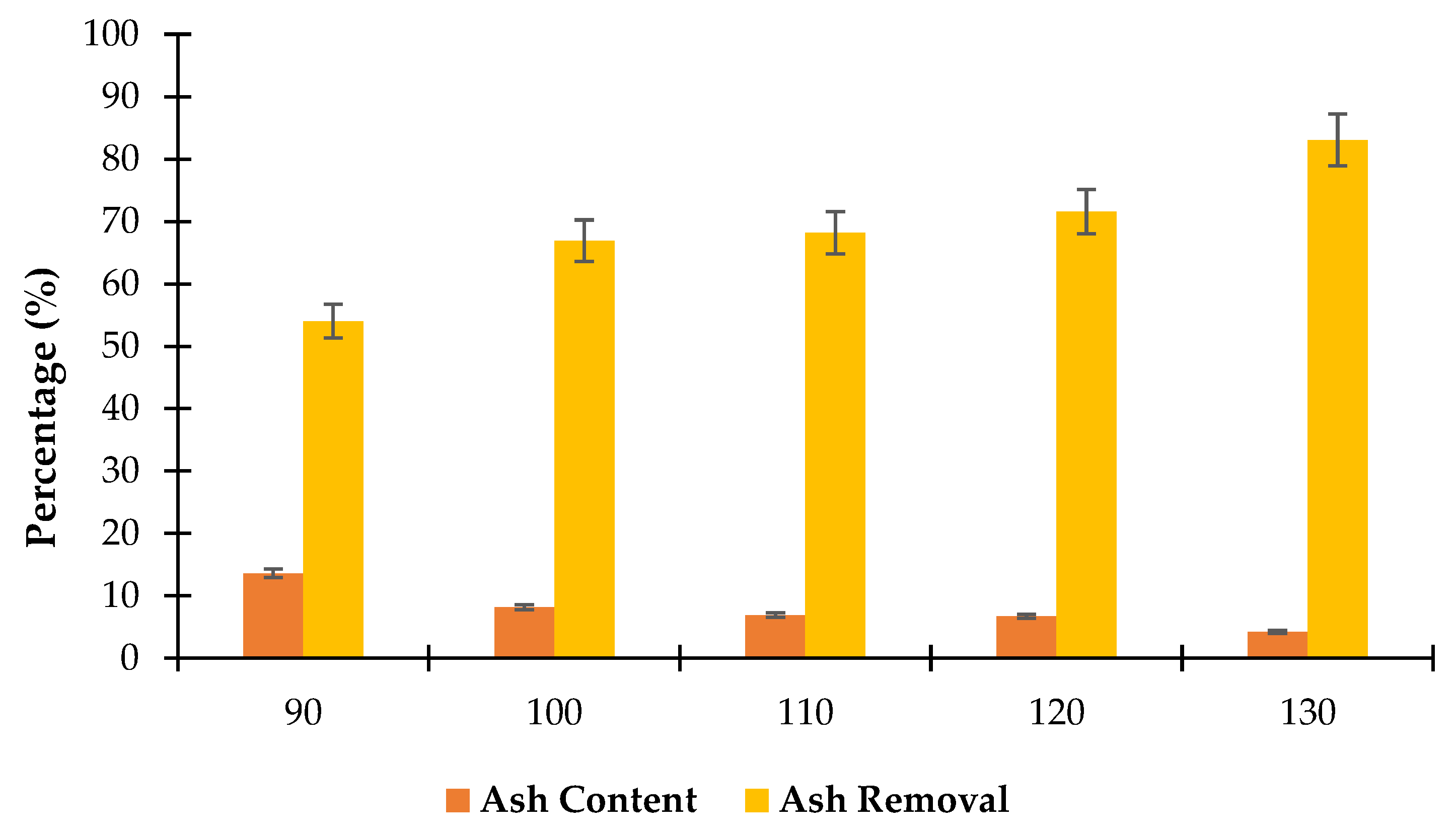

3.2.2. Impact of Temperature on Ash Removal Efficiency

Figure 5 shows the effectiveness of ash removal from

Scenedesmus algae at five different treatment temperatures with corresponding ash contents and removal percentages. The results indicate a clear trend where higher temperatures increase ash removal efficiency. At 90 °C, the ash content in the algae sample is 13.6% with an ash removal efficiency of 54%. This initial stage indicates that moderate temperatures enable some level of ash removal, but the efficiency remains relatively low compared to higher temperatures. This may be associated with limited solubilization of inorganic compounds at lower temperatures, leading to incomplete ash reduction. However, increasing the temperature to 100 °C significantly improves ash removal, with ash content reduced to 8.15% and removal efficiency reaching 66.89%. The enhanced removal at this temperature suggests that heating begins to break down or dissolve more complex ash-forming compounds allowing for more efficient removal of these materials from the algae matrix [

44].

At 110 °C, the ash content decreases slightly to 6.9% with an ash removal efficiency of 68.18%. The marginal increases in efficiency from 100 to 110 °C suggest that while the higher temperature continues to aid in ash removal, the effect is less pronounced than the improvement observed between 90 and 100 °C. This might indicate that a significant portion of easily removable ash compounds have already been eliminated, leaving resistant components. Moreover, the ash content was reduced to 6.7% with an ash removal efficiency of 71.56% at 120 °C. The higher temperature appears to facilitate further ash removal, potentially by increasing the solubility of remaining inorganic compounds. Besides, the efficiency increase remains moderate compared to earlier jumps, possibly due to diminishing returns as more resistant ash compounds remain. The ash removal efficiency reaches its peak, with ash content reduced to 4.2% and an impressive ash removal efficiency of 83.07% at 130 °C. This signifies that higher temperatures are necessary to remove the most resistant ash-forming compounds effectively. The high efficiency at this temperature may be attributed to the breakdown of refractory compounds that only dissolve or disperse at elevated temperatures [

45].

3.3. Successive Cycling

According to

Figure 6, the ash content in the first recycling was found to be 7.52%. This relatively low ash content indicates that the initial recycling process removes inorganic components. This first cycle establishes a baseline for ash removal efficiency and demonstrates that the recycling agent can reduce ash without significant residual accumulation. Notwithstanding, the ash content slightly increases to 8.10% after the second recycling. The marginal rise in ash content suggests a minor reduction in the efficiency of the ash removal process. This could be associated with the partial saturation of the chelating agent or other compounds used in recycling, leading to reduced binding or extraction of ash-forming components in the algae matrix [

46].

In the third recycling cycle, a significant increase in ash content is observed reaching 23.72%. This substantial rise indicates a considerable decline in ash removal efficiency, likely due to the exhaustion or reduced efficacy of the recycling agent. Over successive cycles, the chelating agent or other active compounds may lose their binding capacity, accumulating ash components rather than effective removal [

47]. Additionally, the recycling process may lead to impurities or residuals that are difficult to eliminate in subsequent cycles. For sustainable and efficient recycling, it may be necessary to either limit the number of cycles or regenerate the treatment medium after the cycle to prevent ash accumulation. Besides, developing a cost-effective regeneration protocol for NTA would allow its reuse without compromising efficiency, reducing chemical waste and operational costs.

3.4. Effects of DI and NTA Treatments on Algal Biomass Composition

3.4.1. CHN Elemental Analysis

The ultimate analysis of untreated and treated

Scendesmus algal biomass shows the changes in ash, hydrogen (H), carbon (C), and nitrogen (N) content after each stage of treatment: raw algae, after DI wash, after NTA treatment, and after NTA+DI wash.

Table 2 presents how each treatment stage affects the composition of the algae, potentially enhancing its suitability as a feedstock by reducing ash content and altering elemental composition. The raw algae have a high ash content of 15.2%, which is typical of algal biomass owing to the presence of inorganic compounds. The carbon content reflects the organic matter within the biomass, while the nitrogen content suggests the presence of proteins and other nitrogen-containing compounds. The hydrogen levels are consistent with typical algal composition.

Washing DI water leads to a modest reduction in ash content to 12.9% indicating the removal of water-soluble inorganic salts and surface-bound ash particles. The slight decrease in H and N content could suggest the loss of some loosely bound organic molecules within the biomass. NTA treatment significantly reduces ash content to 7.2%, demonstrating the effectiveness of NTA as a chelating agent that binds and removes metal ions and other ash-forming compounds. This stage marks a substantial improvement in the deashing of the algal biomass. However, the CHN composition remains relatively stable with H at 6.1%, C at 45.4%, and N at 7.2%.

Following the NTA treatment with an additional DI wash yields the lowest ash content at 3.8%. This dual-step process enhances the removal of residual inorganic components, resulting in highly purified algal biomass. Despite this remarkable reduction in ash content, the CHN composition shows only minor decreases, with H at 6.0%, C at 45.2%, and N at 7.1%. These negligible changes in CHN values suggest that the NTA and combined treatment (NTA+DI) efficiently remove ash while maintaining the organic framework of the biomass.

When evaluating the changes in CHN in terms of percentages, the results show minimal changes in the CHN composition of the biomass across all the treatment stages. The decreases in C, H, and N are marginal, reflecting the preservation of the organic structure of the algae. However, when analyzed in terms of absolute weight percentage, the results indicate a significant transformation. The substantial reduction in ash content leads to an increase in the relative proportion of organic material in the biomass.

3.4.2. Metal Ions Analysis

Table 3 presents the concentration of various metal ions (Ca, K, Cu, Zn, and Pb) in the

Scenedesmus algal biomass at the aforementioned stages. The raw algae contain various metal ions with calcium (Ca) and potassium (K) being the most abundant at 6.72 ppm and 4.43 ppm, respectively. Zinc (Zn) and lead (Pb) are also present revealing potential contamination with heavy metals. After the DI water wash, Ca reduces marginally to 6.52 ppm indicating that DI water alone is ineffective at removing Ca. This is likely due to its stable association with the biomass. K decreases significantly to 2.77 ppm, suggesting that K is more soluble and readily removed by DI water. In addition, Cu, Zn, and P decrease to 0.33, 3.30, and 0.14 ppm, respectively, showing partial removal of these metals with DI water.

After NTA treatment, Ca is reduced to below detectable level (BDL) indicating that NTA effectively chelates Ca, removing it from the biomass. K decreases further to 2.33 ppm; however, the reduction is less significant than after the DI wash. Cu (0.28 ppm), Zn (1.99 ppm), and Pb (0.12 ppm) decreased with NTA showing an enhanced ability to bind and remove these metals compared to DI water. Besides, the combined effect of NTA treatment followed by DI wash achieves the most comprehensive metal ion removal. Ca and K were below detectable levels, showing that the combination of treatments fully removes these ions. Likewise, Cu, Zn, and Pb were further reduced to 0.20, 0.57, and 0.03 ppm, respectively. This reduction in metal content not only lowers potential toxicity but also improves the purity of the biomass, making it more suitable for applications that require low levels of inorganic contaminants.

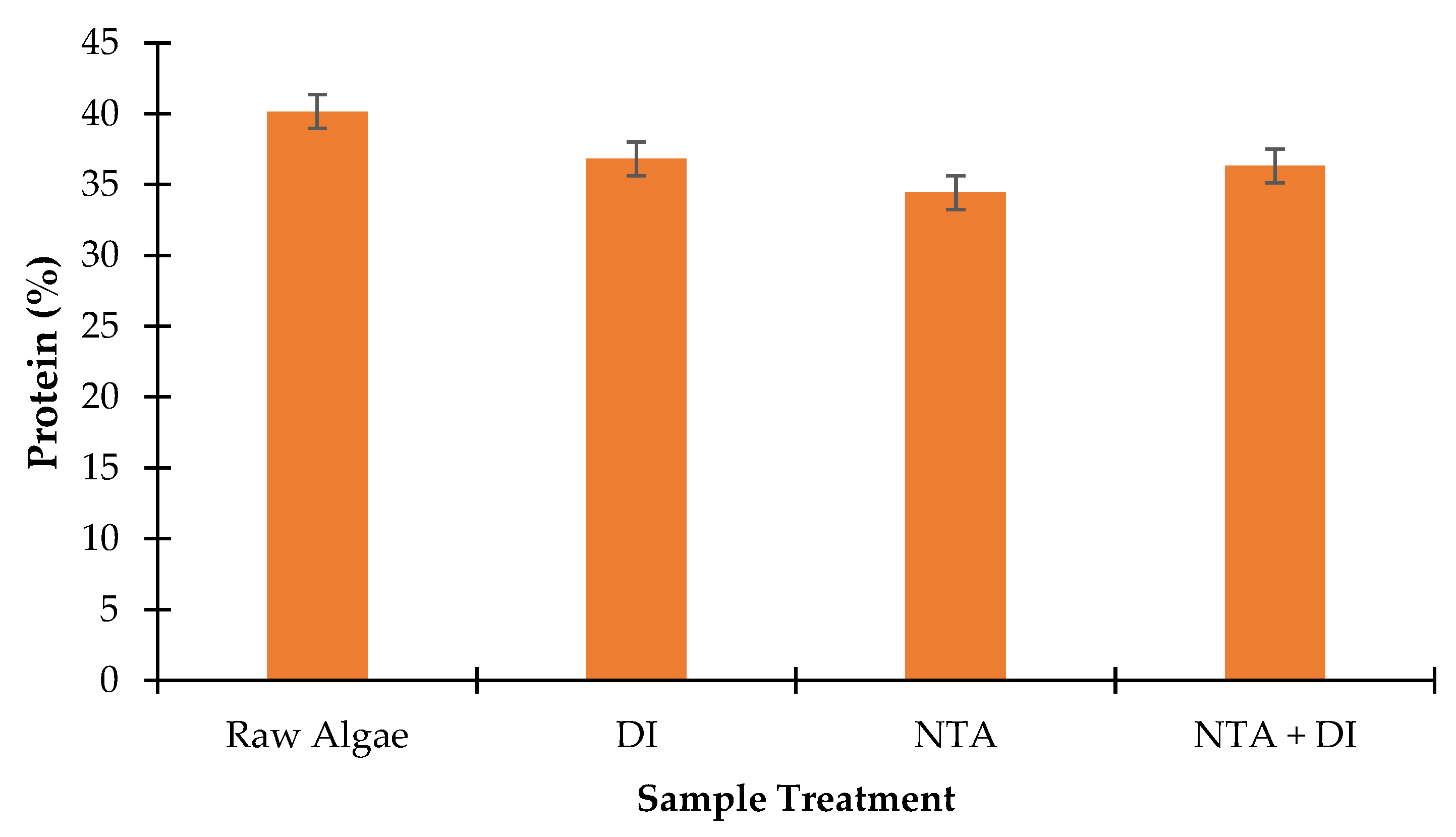

3.4.3. Protein Determination Analysis

The evaluation of protein content in the supernatant during sequential algal treatments with DI water, NTA, and NTA+DI highlights the impact of the deashing process on the biochemical composition. The N% (i.e.,

Table 2) values derived from the CHN elemental analysis were converted to protein content using Equation 2 and a conversion factor of 4.78 recommended by NREL.

Figure 7 provides insights into the impact of each treatment on the nutritional value and possible structural or compositional alterations of the biomass. The untreated raw algae sample has a high protein content of 40.15%, typical of

Scenedesmus and other microalgae, reflecting its potential as a high-protein biomass for nutritional and industrial applications. After washing with DI water, the protein content slightly decreases to 36.81%. This decrease could be due to the loss of water-soluble protein fragments or the removal of loosely bound protein-associated compounds from the algal surface. The moderate decrease suggests that DI water alone has a minimal effect on the protein structure within the biomass.

Following NTA treatment, the protein content further decreases to 34.42%. NTA, as a chelating agent, may cause partial disruption of the protein structure by binding to metal ions that stabilize certain protein complexes [

48]. This reduction suggests that NTA treatment could potentially lead to the release or breakdown of protein components structurally or functionally associated with metal ions leading to a more noticeable protein loss. Conversely, after the combined NTA and DI wash, the protein content slightly recovers to 36.32%. This recovery might indicate that the final DI wash removes residual NTA or other compounds that could interfere with protein quantification or structural stability. In addition, the combined treatment may also have removed specific protein fragments or contaminants, leading to a relative concentration of remaining proteins [

49].

Given the promising results of NTA+DI, further optimization of this combined treatment is recommended to minimize the loss of organic nitrogen treatment while maintaining high levels of ash removal. One potential approach could involve varying the concentration of NTA or adjusting the duration of the DI wash to achieve a balance between metal removal, ash reduction, and nitrogen retention. Alternatively, less aggressive chelation agents could be tested with NTA to reduce the impact on nitrogen and protein content. To further enhance the nutritional value of treated algae, it would be critical to investigate treatments that specifically preserve protein content. Protein levels showed a minimal decrease under the NTA treatment. Thus, alternative methods such as enzyme-based treatments or optimized chemical agents could be explored for maintaining protein integrity while achieving effective purification.

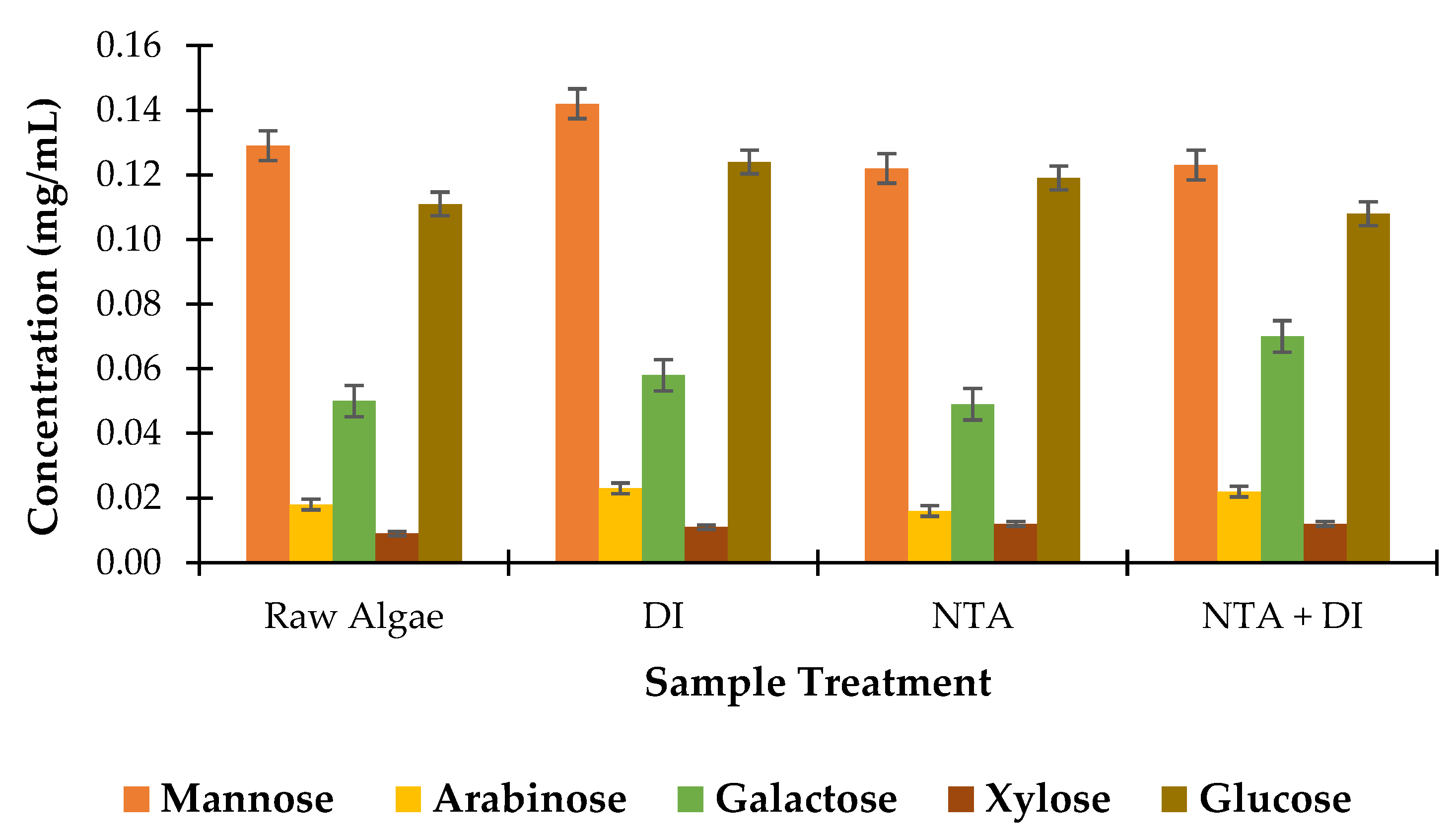

3.4.4. Sugar Concentration Analysis

Figure 8 presents the concentration of various monomeric sugars in the biomass. The raw algae sample has baseline concentrations of the sugars with mannose (0.129 mg/mL) and glucose (0.111 mg/mL) being the most abundant. This baseline serves as a reference to assess the sugar loss or retention after various treatments. After the DI wash, there is a minimal increase in most sugar concentrations: mannose increases from 0.129 to 0.142 mg/mL, and glucose rises from 0.111 to 0.124 mg/mL. This increase could be due to the release of cell wall-bound sugars or the solubilization of polysaccharides in DI water; arabinose and galactose also exhibited slight increase which could be attributed to similar solubilization effects, indicating that DI water facilitates mild sugar release without significantly degrading the biomass [

50].

After the NTA treatment, mannose and glucose concentrations slightly decrease to 0.122 mg/mL and 0.119 mg/mL, respectively. This reduction might indicate some structural alteration or removal of carbohydrate-associated complexes due to the chelating effect of NTA. Arabinose also slightly decreases to 0.016 mg/mL, suggesting that NTA may affect certain sugar components, possibly weakly bound or associated with the ash or mineral content. Additionally, xylose demonstrated a minor increase, which may reflect minor structural rearrangements that liberate certain bound sugars, though the overall impact on xylose is minimal.

The combined NTA+DI wash results in minor changes to the sugar profile: galactose increases to 0.070 mg/mL, a notable rise compared to previous treatments, which might suggest further breakdown or solubilization of complex carbohydrates into simpler sugars under sequential treatment. Mannose and glucose concentrations stabilize at 0.123 mg/mL and 0.108 mg/mL, respectively, indicating that these sugars are relatively stable under combined treatment. Moreover, arabinose recovers slightly to 0.0022 mg/mL which could be due to additional solubilization during the DI wash after NTA treatment.

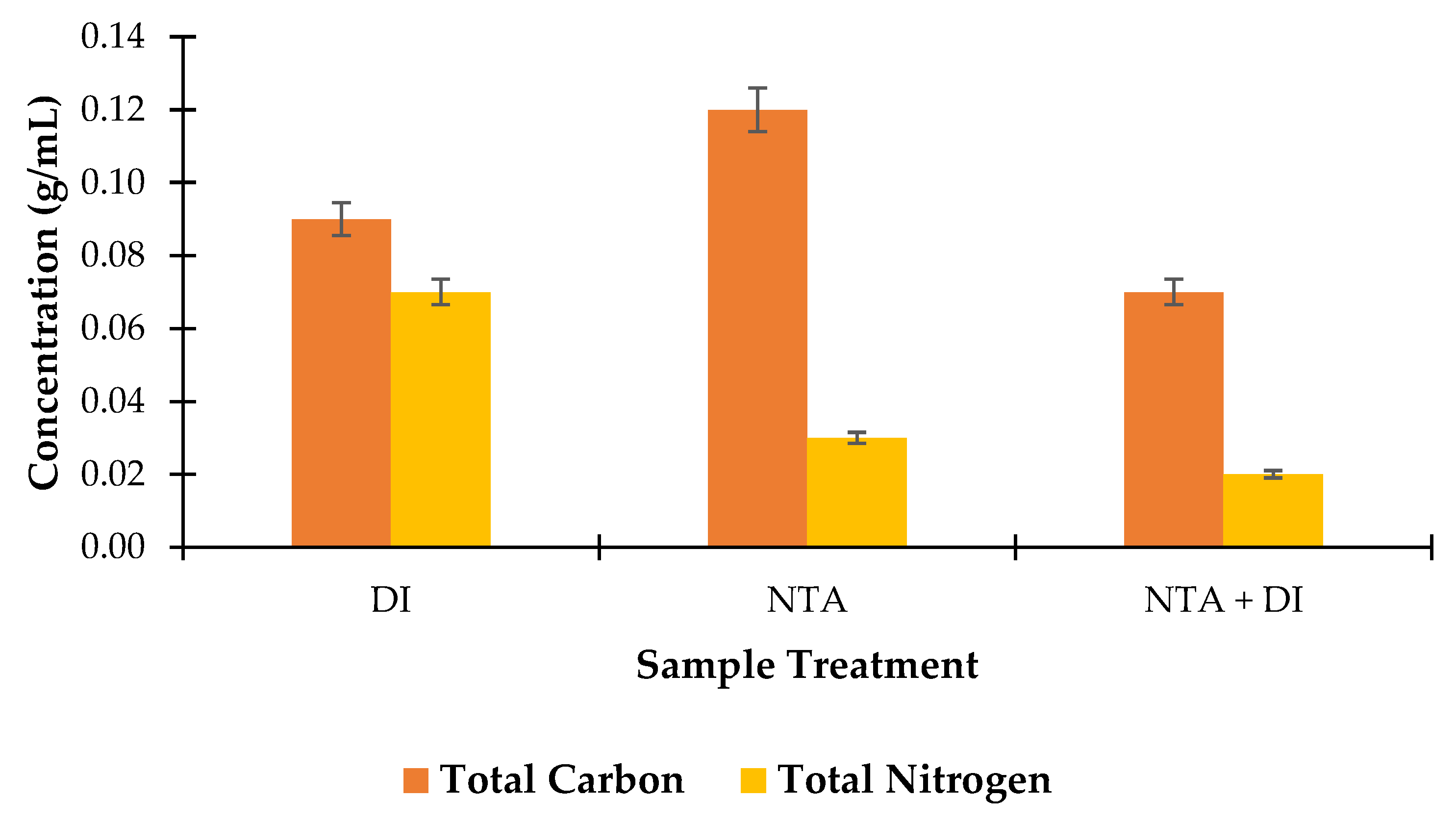

3.4.5. Total Carbon and Nitrogen Content Analysis

Figure 9 provides insight into how each treatment impacts the elemental composition of the biomass, particularly in terms of TC and TN levels. After the DI wash, the TC level averages 0.09 g/mL, serving as a baseline for the untreated biomass. The DI wash has a mild effect, mostly removing surface impurities without significantly impacting the internal carbon content of the algae. The TN content after DI wash is relatively high at 0.07 g/mL, indicating that nitrogen-containing compounds like proteins and amino acids are largely retained. This suggests that DI washing, a gentle process, maintains much of the nitrogenous material in the biomass.

Following NTA treatment, TC increases to 0.12 g/mL. This increase may reflect the removal of inorganic ash components, concentrating the organic matter relatively. The chelating action of NTA might selectively reduce certain nitrogenous impurities while retaining more carbon-rich material. However, the TN content declined significantly to 0.03 g/mL after NTA treatment. This decrease is likely due to the ability of NTA to chelate and remove nitrogen-rich impurities or ash-related nitrogen compounds, resulting in an overall reduction in nitrogen content.

The TC content decreases to 0.07 g/mL following the combined treatment, indicating a slight reduction in organic material compared to NTA treatment alone. This could result from the DI wash removing additional residual organic substances or altering carbon-containing structures after NTA treatment. The TN content further declines to 0.02 g/mL after the combined treatment, the lowest among all stages. The sequential NTA and DI wash appears to be the most effective in reducing nitrogen content, likely due to the cumulative removal of nitrogen-rich ash and other nitrogenous residues.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the effectiveness of various treatments, including DI, NTA, and their combination (NTA+DI), in reducing ash content and heavy metals from Scendesmus algal biomass, with temperature significantly enhancing treatment efficiency. The following observations were made:

(1) The ash removal was most efficient with the combined NTA+DI treatment, which reduced ash content from 15.2% in algae to 3.8%, surpassing the results achieved with DI or NTA alone. The DI treatment primarily leached surface-bound impurities, while the chelation properties of NTA selectively removed ash-forming elements by forming stable complexes. The synergistic action of NTA+DI facilitated the deeper removal of ash-associated compounds.

(2) The temperature was a crucial factor in ash removal efficiency as treatment temperatures increased from 90°C to 130°C. The ash removal process became significantly more effective, peaking at an impressive 83.07% efficiency at 130°C. This performance enhancement at elevated temperatures is due to improved solubility of ash-forming compounds and reaction kinetics, which facilitate the release and chelation of Ca, K, and Mg.

(3) Successive recycling of the NTA treatment revealed a decline in efficiency due to the saturation of the chelating agent by the third cycle. This trend indicates the gradual saturation of the chelating agent, underlining the need for regeneration or replenishment in practical applications.

(4) The sequential treatment of algal biomass with deionized water and NTA shows a highly effective method for ash removal. However, the CHN composition with H at 6.0%, C at 45.2%, and N at 7.1% revealed comparatively smaller percentage changes in the elemental distribution of the ultimate analysis. This indicates the process effectively balances ash removal with the retention of valuable organic components, presenting a promising method for deashing algal biomass. Similarly, the protein content showed minimal changes except for the sugar composition which exhibited more variability due to partial degradation of the cell wall polysaccharides.

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.D., S.K.; Software, A.A. and S.K.; Investigation, G.D. and A.A.; Writing – original draft, A.A., G.D., R.W.D., and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sandia National Laboratories, Livermore, California with support from the U.S. Dept. of Energy BioEnergy Technologies Offices (BETO), Renewable Carbon Resources program through agreement 1.3.5.002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-mission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ullah, K.; et al. Assessing the potential of algal biomass opportunities for bioenergy industry: a review. Fuel 2015, 143, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matayeva, A.; Basile, F.; Cavani, F.; Bianchi, D.; Chiaberge, S. Development of upgraded bio-oil via liquefaction and pyrolysis. in Studies in surface science and catalysis vol. 178 231–256 (Elsevier, 2019).

- Kargbo, H.; Harris, J.S.; Phan, A.N. “Drop-in” fuel production from biomass: Critical review on techno-economic feasibility and sustainability. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 135, 110168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, M.; et al. A review on the pyrolysis of algal biomass for biochar and bio-oil–Bottlenecks and scope. Fuel 2021, 283, 119190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, Z.; Anand, A.; Gautam, S. An overview on thermochemical conversion and potential evaluation of biofuels derived from agricultural wastes. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klass, D.L. Biomass for Renewable Energy, Fuels, and Chemicals. (Elsevier, 1998).

- Ashraf, M.; et al. Photoreforming of waste polymers for sustainable hydrogen fuel and chemicals feedstock: waste to energy. Chem Rev 2023, 123, 4443–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Dai, G.; Yang, H.; Luo, Z. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis mechanism: A state-of-the-art review. Prog Energy Combust Sci 2017, 62, 33–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nigam, P.S.; Murphy, J.D. Renewable fuels from algae: an answer to debatable land based fuels. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Ong, H.C.; Gan, Y.Y.; Chen, W.-H.; Mahlia, T.M.I. State of art review on conventional and advanced pyrolysis of macroalgae and microalgae for biochar, bio-oil and bio-syngas production. Energy Convers Manag 2020, 210, 112707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Banat, F.; AlBlooshi, H. Algal Biotechnology: Integrated Algal Engineering for Bioenergy, Bioremediation, and Biomedical Applications. (Elsevier, 2022).

- Satpati, G.G.; et al. Recent development in microalgal cultivation and biomass harvesting methods. in Algal Biorefineries and the Circular Bioeconomy 61–91 (CRC Press, 2022).

- Özçimen, D.; Gülyurt, M.Ö.; İnan, B. Algal biorefinery for biodiesel production. Biodiesel-feedstocks, production and applications 25–57 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G. Composition, properties and challenges of algae biomass for biofuel application: An overview. Fuel 2016, 181, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; et al. Role of microalgae in achieving sustainable development goals and circular economy. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 854, 158689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froment, K.; Seiler, J.-M.; Defoort, F.; Ravel, S. Inorganic species behaviour in thermochemical processes for energy biomass valorisation. Oil Gas Science and Technology–Revue d’IFP Energies nouvelles 2013, 68, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushkov, D.; Nyashina, G.; Shvets, A.; Pereira, A.; Ramanathan, A. Current status of the pyrolysis and gasification mechanism of biomass. Energies 2021, 14, 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, D.; et al. Ash transformation chemistry during combustion of biomass. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston, J.E.; Wahlen, B.D.; Davis, R.W.; Siccardi, A.J.; Wendt, L.M. Application of aqueous alkaline extraction to remove ash from algae harvested from an algal turf scrubber. Algal Res 2018, 35, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; et al. Techno-economic analysis of ash removal in biomass harvested from algal turf scrubbers. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 123, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, R.B.; et al. Characterization and thermal decomposition of demineralized wastewater algae biomass. Algal Res 2019, 38, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, B.M.; Bakker, R.R.; Wei, J.B. On the properties of washed straw. Biomass Bioenergy 1996, 10, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ganesh, A.; Wangikar, P. Influence of pretreatment for deashing of sugarcane bagasse on pyrolysis products. Biomass Bioenergy 2004, 27, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turn, S.Q.; Kinoshita, C.M.; Ishimura, D.M. Removal of inorganic constituents of biomass feedstocks by mechanical dewatering and leaching. Biomass Bioenergy 1997, 12, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Tan, H. Ash-related issues during biomass combustion: Alkali-induced slagging, silicate melt-induced slagging (ash fusion), agglomeration, corrosion, ash utilization, and related countermeasures. Prog Energy Combust Sci 2016, 52, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, S.D.; et al. Optimization of bio-oil yields by demineralization of low quality biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 83, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.-M.; et al. Enhancement of gasification performance for palm oil byproduct by removal of alkali and alkaline earth metallic compounds and ash. Energy fuels 2019, 33, 5263–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bi, X.T. Removal of inorganic constituents from pine barks and switchgrass. Fuel processing technology 2011, 92, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitria; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Roles of mineral matter in biomass processing to biofuels. Biofuels Bioproducts and Biorefining 2023, 17, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, C.W.; Hamilton, C.; Kim, K.; Chmely, S.C.; Labbé, N. Using a chelating agent to generate low ash bioenergy feedstock. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 96, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yabar, H.; Higano, Y. Perspective assessment of algae-based biofuel production using recycled nutrient sources: The case of Japan. Bioresour Technol 2013, 128, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, P.; Ross, A.B. Potential yields and properties of oil from the hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae with different biochemical content. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Esterly, S. Renewable Electricity Standards: Good Practices and Design Considerations. A Clean Energy Regulators Initiative Report. (2016).

- Hames, B.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, A. Determination of Protein Content in Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); Issue Date 05/23/2008. www.nrel.gov (2008).

- Van Wychen, S.; Laurens, L.M.L. Determination of Total Carbohydrates in Algal Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP). www.nrel.gov/publications. (2023).

- Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; et al. Impact of flue gas compounds on microalgae and mechanisms for carbon assimilation and utilization. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C. Environmental implications and applications of. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2015, 10, 329–355. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.; Golińska, P. Microbial Nanotechnology. (CRC press, 2020).

- Edmunds, C.W.; Hamilton, C.; Kim, K.; Chmely, S.C.; Labbé, N. Using a chelating agent to generate low ash bioenergy feedstock. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 96, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Characterization of ash in algae and other materials by determination of wet acid indigestible ash and microscopic examination. Algal Res 2017, 25, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.A.S.; Saldanha-Corrêa, F.M.P.; Gallego, A.G.; Neto, A.M.P. Semi-quantitative determination of ash element content for freeze-dried, defatted, sulfated and pyrolysed biomass of Scenedesmus sp. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusup, S.; Rashidi, N.A. Value-Chain of Biofuels: Fundamentals, Technology, and Standardization. (Elsevier, 2021).

- Gholami, A.; Pourfayaz, F. A Review on Biodiesel Production: Recent Advances in Feedstocks, Catalysts, and Conversion Technologies. Biofuels 2024, 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-T.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gai, C.; Qian, W. Physical pretreatments of wastewater algae to reduce ash content and improve thermal decomposition characteristics. Bioresour Technol 2014, 169, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhong, Z.; Jin, B.; Zheng, A. Selection of temperature for bio-oil production from pyrolysis of algae from lake blooms. Energy fuels 2012, 26, 2996–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the composition and application of biomass ash.: Part 2. Potential utilisation, technological and ecological advantages and challenges. Fuel 2013, 105, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacco, A.; et al. Review of fly ash inertisation treatments and recycling. Environ Chem Lett 2014, 12, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, J.A.; Falke, J.J. [16] Purification of proteins using polyhistidine affinity tags. in Methods in enzymology vol. 326 245–254 (Elsevier, 2000).

- Casonato Melo, C.; et al. Recovering What Matters: High Protein Recovery after Endotoxin Removal from LPS-Contaminated Formulations Using Novel Anti-Lipid A Antibody Microparticle Conjugates. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.; Ingle, A.P.; da Silva, S.S.; Rai, M. Immobilized nanoparticles-mediated enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose for clean sugar production: a novel approach. Curr Nanosci 2019, 15, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).