Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attitudes Towards Tourism

2.2. Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Tourism Activity

2.3. Resilience or Survival Instincts?

3. Description of the Study Area and Methodology

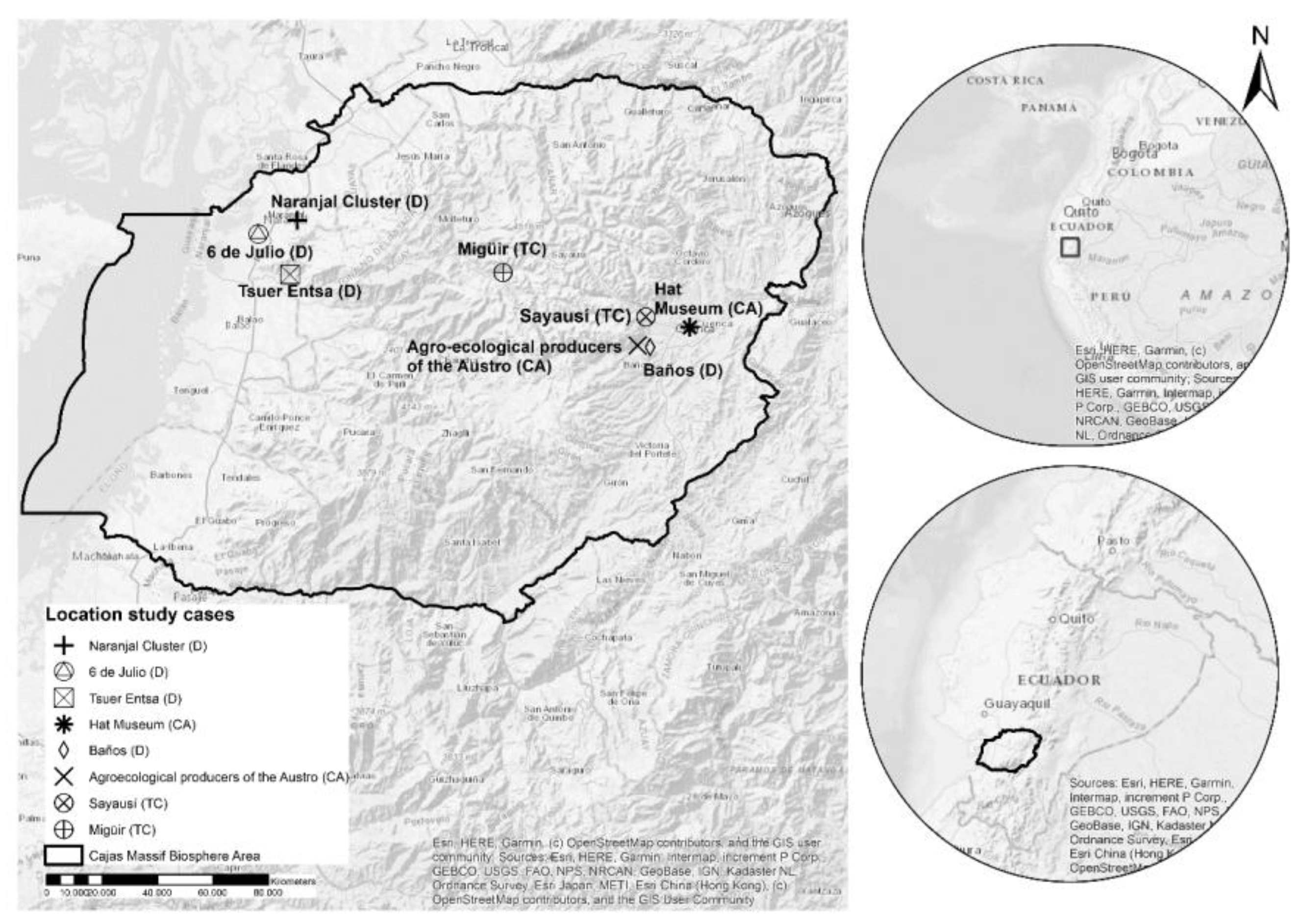

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Data Collection Instrument

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Statements Assessed: Some Figures

4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4.2.1. Dimension 1: Economic Mutualism

4.2.2. Dimension 2: Socioeconomic Participation in Tourism

4.2.3. Dimension 3: Deferral of Tourism’s Social and Environmental Costs

4.2.4. Dimension 4: Awareness of Tourism Development

4.2.5. Dimension 5: COVID-19 and Tourism—Lessons Learned, Learning Forgotten

4.3. Cluster Analysis Based on PCA Dimensions

| Dimensions | Cluster 1: Economic Pragmatists |

Cluster 2: Critical Realists |

Cluster 3: Survivalist Idealists |

Cluster 4: Moderate Sceptics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: Economic mutualism | 0.2440628 | -1.7635238 | 0.5002467 | 0.1128738 |

| Dimension 2: Socioeconomic participation in tourism | -0.0606547 | -0.5193065 | -0.7212485 | 1.0205093 |

| Dimension 3: Deferring the social and environmental costs of tourism | 0.1979907 | 0.06393041 | -0.29030774 | 0.12094741 |

| Dimension 4: Awareness about tourism development | -0.28838378 | 0.20900584 | -0.05076376 | 0.17046617 |

| Dimension 5: Covid-19 and tourism: Lessons, yes; learning, no | -1.2674468 | 0.1078453 | 0.5175333 | 0.3617315 |

4.3.1. Cluster 1: Economic Pragmatists

4.3.2. Cluster 2: Critical Realists

4.3.3. Cluster 3: Survivalist Idealists

4.3.4. Cluster 4: Moderate Sceptics

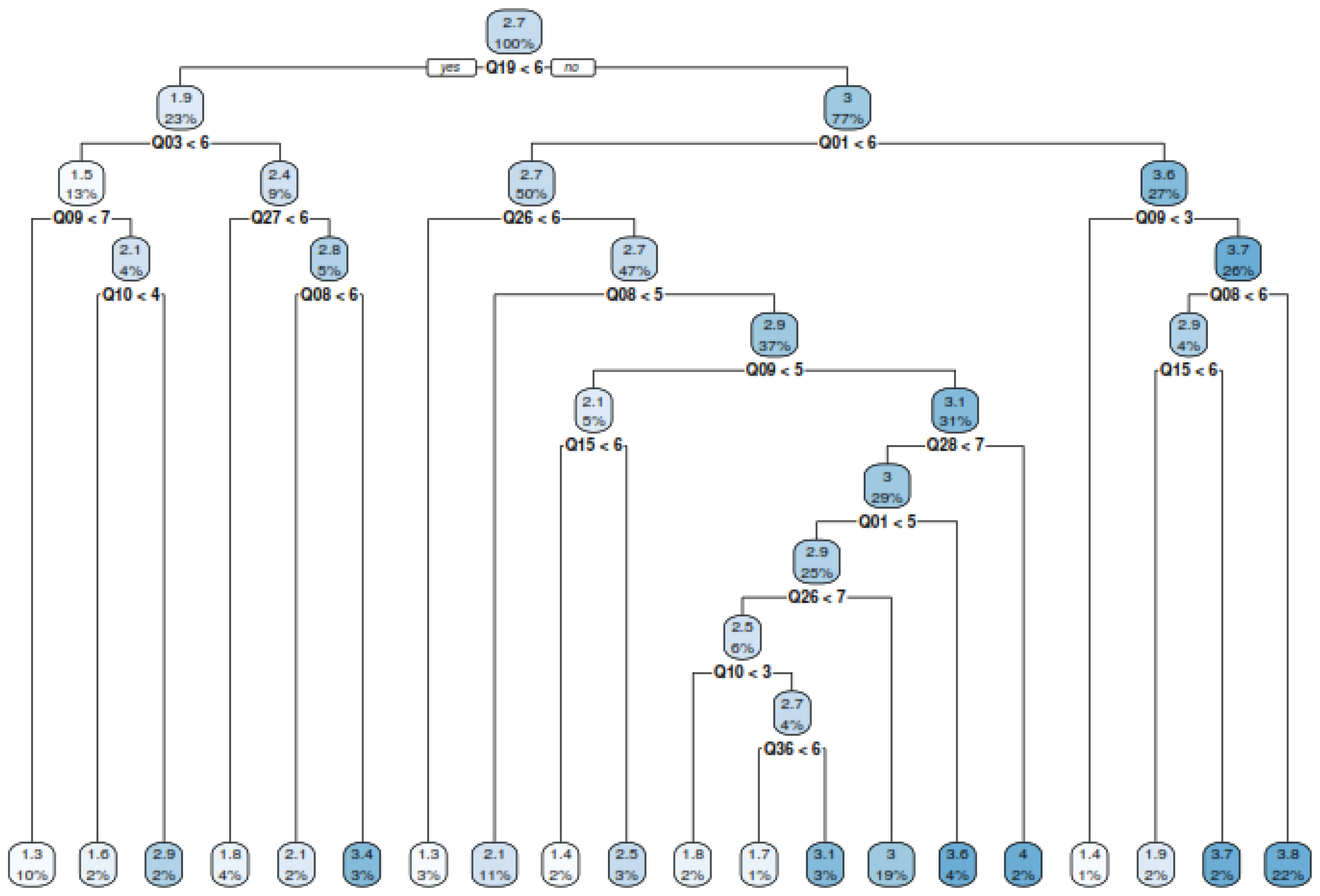

4.4. Decision Tree Analysis

4.4.1. Simple Cross-Validation

4.5. Contextual Insights from a Qualitative Perspective

“We came together with the hope that tourism would bring us better economic opportunities, but this unity was temporary. After the pandemic, individual economic interests prevailed.”(LC01)

“We united because there was no other option, but as soon as things returned to normal, we went back to business as usual.”(BS03)

4.5.1. Ephemeral Solidarity vs. Genuine Learning

“We came together with the hope that tourism would bring us better economic opportunities, but this unity was temporary. After the pandemic, individual economic interests prevailed.”(LC01)

4.5.2. Economic Dependence and Community Tensions

“Tourism provides us with jobs and helps us move forward, but we depend on visitors coming. If that fails, we have no other option.”(LC02)

“During the pandemic, there was no tourism, and that was our main activity […] so we focused on the small fields we had around here. We had crops planted on our plots up the verde (hill—greens), yuquitas (cassava) here and there. We also hunted wild animals we found nearby, and that’s how we got through the pandemic.”(LC16)

4.5.3. Underestimation of Social and Environmental Costs: A Stronger Critique in the Qualitative Discourse

“The leaders lack self-management and focus solely on carrying out projects with the money they receive from tourism, but they have no vision for investment—only spending. There is no leadership in the community, which causes conflicts among association members. The board arbitrarily determines the salaries to be received. […] There is widespread corruption among the leaders, who expect to gain personal benefits from tourism. There is no transparency in management. They simply aim to receive a salary for two years (the duration of their term).”(LC13)

4.5.4. The Role of the Public Sector and “Promotion Without Planning”

“Within the public sector, we only have (...) a political figure (...) just promotion, promotion, promotion, and never any planning.”(BS03)

“Promotion was never set aside. Now, the issue of promotions is very sensitive because promotion requires resources—creating more campaigns and figuring out how to proceed when the central government provided no funding and, therefore, no budget allocation for promotion. This meant there were no resources to ensure that international tourists would not forget about this wonderful destination waiting for them. While it is true that tourism was not possible during the pandemic [...].”(PS01)

4.5.5. Inconsistencies in the “Visibility” of Economic Diversification

“That was one of the main topics we discussed because it had already been decided that we would go into lockdown. So, I came up with the idea of launching an awareness campaign, which we managed to carry out in time: ’We are here, don’t cancel your trip. We are still a destination. We will take this pause to prepare, but we remain a place you can visit.’”(PS02)

4.5.6. Building Resilience: A Process Still Incomplete

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMBA | Cajas Massif Biosphere Area |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| TC | Tourist Corridors |

| TD | Tourist Destinations |

| CA | Complementary Attractions |

| EDA | Exploratory data analysis |

Appendix A

| COD | Macrovariable | Cod. | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ENGAGEMENT/AVERSION | Q1 | I participate in tourism activities in my community. |

| Q10 | I am aware of the tourism activities in my community. | ||

| Q19 | I am open to tourism activities promoted in my community. | ||

| Q28 | I work more in tourism than in other productive activities such as livestock, fishing, agriculture, handicrafts, etc. | ||

| 2 | WELLBEING/TENSIONS | Q2 | Tourism causes conflicts among the members of my community. |

| Q11 | I resent the fact that tourism activities are carried out by people/companies outside the community. | ||

| Q20 | My quality of life has improved with tourism | ||

| Q29 | Tourism has made my community more organised. | ||

| 3 | BENEFITS EQUALLY SPREAD | Q3 | I think that the income from tourism is not shared equally among community members. |

| Q12 | Thanks to tourism I have learned new things that I did not know before (customer service, tour guide, administration, etc.). | ||

| Q21 | Tourism in my community depends a lot on economic support from people/agents outside the community. | ||

| Q30 | Tourism is not interesting for me, because it is poorly paid. | ||

| 4 | ISSUES ABOUT TOURISM FROM ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE | Q4 | Tourism has generated employment/business opportunities in my community |

| Q13 | Tourism has increased my income | ||

| Q22 | Tourism has caused new taxes to be paid in my community | ||

| Q31 | In the future tourism could increase the cost of living in my community (food, housing and land prices) | ||

| 5 | RESPECT FOR NATURE | Q5 | Tourism has caused vehicular disorder (traffic and vehicular noise) in my community |

| Q14 | Tourists pollute my community’s water resources (rivers, lagoons, lakes, mangroves, etc.) | ||

| Q23 | Tourists leave rubbish in my community | ||

| Q32 | Tourism has helped to conserve species (vegetation and animals) in my community | ||

| 6 | RESPECT FOR CULTURE | Q6 | Tourism has helped to maintain local productive activities in my community (agriculture, fishing, crab gathering, livestock, handicrafts, etc.). |

| Q15 | Tourism has fostered friendships (encounters) between tourists and people from the community | ||

| Q24 | Tourism has strengthened our traditions (festivals, rituals and others). | ||

| Q33 | Tourism has encouraged my participation in cultural activities (festivals, rituals, etc.). | ||

| 7 | TOURISM AWARENESS | Q7 | Tourism has improved trust among members of my community. |

| Q16 | Local tourism laws take into account the needs of the people in my community. | ||

| Q25 | Tourism has led to prostitution, alcohol consumption and drug use in my community. | ||

| Q34 | Tourism has led to problems of insecurity in my community | ||

| 8 | FUTURE OF TOURISM | Q8 | Tourism has helped women to have jobs/businesses in my community. |

| Q17 | In the future, tourism will be the main activity in my community. | ||

| Q26 | It is not possible to live only from tourism, other activities such as agriculture, handicrafts, livestock, fishing, etc. are needed. | ||

| Q35 | The Cajas Massif Biosphere Area can attract more tourists in the future | ||

| 9 | IMPACT OF COVID-19 | Q9 | COVID-19 has shown that we cannot depend solely on tourism as a source of income in my community. |

| Q18 | My community has adapted its tourism activities to the scenario brought about by COVID-19. | ||

| Q27 | After COVID-19 tourism will be able to help the community by respecting nature, culture and social relations. | ||

| Q36 | COVID-19 proved that Ecuadorian tourists are more important than we thought. |

References

- Christin, R. Mundo En Venta. Crítica a La Sinrazón Turística; Éditions L.; París, 2018.

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Fernandez, M. Territorial Tourism Resilience in the COVID-19 Summer. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2022, 3, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F. Superando La Adversidad: ¿resiliencia Del Turismo En La Ruralidad Durante La COVID-19? Comunidades En El Sur de Ecuador Como Marco de Estudio. Investigaciones Turísticas 2024, 103–126. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, D.; Hall, C.M.; Stoeckl, N. The Resilience of Formal and Informal Tourism Enterprises to Disasters: Reef Tourism in Phuket, Thailand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2012, 20, 645–665. [CrossRef]

- Almeida García, F.; Balbuena Vázquez, A.; Cortés Macías, R. Resident’s Attitudes towards the Impacts of Tourism. Tour Manag Perspect 2015, 13, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M. Towards a Universal Measure of “Support for Tourism.” Ann Tour Res 2016, 61, 238–241. [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Xu, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.K.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ Perceived Risk, Emotional Solidarity, and Support for Tourism amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2021, 19, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Reid, J. Una Vida En Resiliencia. El Arte de Vivir En Peligro; Fondo de C.; Ciudad de México, 2016;

- Hadinejad, A.; D. Moyle, B.; Scott, N.; Kralj, A.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism: A Review. Tourism Review 2019, 74, 157–172. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.J.; Haywantee, R. Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism: A Longitudinal Study of 140 Articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2013, 21, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host Perceptions of Tourism: A Review of the Research. Tour Manag 2014, 42, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Uslu, A.; Cinar, K.; Woosnam, K.M. Using a Value-Attitude-Behaviour Model to Test Residents’ pro-Tourism Behaviour and Involvement in Tourism amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism 2023, 26, 3111–3124. [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Sangpikul, A. Resident Perceptions towards COVID-19 Public Policies for Tourism Reactivation: The Case of Thailand. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 2022, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J.; Baker, C.; Fyall, A. COVID-19 and Tourism: Analyzing the Effects of COVID-19 Statistics and Media Coverage on Attitudes toward Tourism. Forecasting 2021, 3, 870–883. [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H. Tourist Destination Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourism during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism 2021, 25, 134–149. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Boley, B.B.; Yang, F.X. Resident Empowerment and Support for Gaming Tourism: Comparisons of Resident Attitudes Pre- and Amid-Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2022, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourism Resilience in the ‘New Normal’: Beyond Jingle and Jangle Fallacies? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 54, 513–520. [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A.; Tileagă, C.; Popșa, R.E. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12541. [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Russell, Z.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Denley, T.J.; Rojas, C.; Hadjidakis, E.; Barr, J.; Mower, J. Residents’ pro-Tourism Behaviour in a Time of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2021, 30, 1858–1877. [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Mai, L.Q.; Schuckert, M. Social Representations and Resident Attitudes: A Multiple-Mixed-Method Approach. Ann Tour Res 2019, 78, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism Development: A Literature Review with Implications for Tourism Planning. J Plan Lit 2004, 18, 251–266. [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Stojanović, V.; Kovačić, S.; Jovanovic, T.; Pantelić, M.; Vujičić, M. Assessment of Residents’ Attitudes toward Sustainable Tourism Development - A Case Study of Bačko Podunavlje Biosphere Reserve, Serbia. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2021, 35, 100384. [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. Locals’ Attitudes toward Mass and Alternative Tourism: The Case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. J Travel Res 2010, 49, 381–394. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, J.L.; Li, G.; Goh, C. Tourism and Regional Income Inequality: Evidence from China. Ann Tour Res 2016, 58, 81–99. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Munanura, I.E.; Kooistra, C.; Needham, M.D.; Ghahramani, L. Understanding Effects of Tourism on Residents: A Contingent Subjective Well-Being Approach. J Travel Res 2022, 61, 346–361. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C. Syncretism and Indigenous Cultural Tourism in Taiwan. Ann Tour Res 2020, 82, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Weyland, F.; Colacci, P.; Cardoni, A.; Estavillo, C. Can Rural Tourism Stimulate Biodiversity Conservation and Influence Farmer’s Management Decisions? J Nat Conserv 2021, 64, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Dai, M.; Ou, Y.; Ma, X. Residents’ Happiness of Life in Rural Tourism Development. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2021, 20, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pernecky, T. Critical Tourism Scholars: Brokers of Hope. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 657–666. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.A.; Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Ash, K.; Yang, E. Tourism and Economic Resilience. Ann Tour Res 2021, 87, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can Community-Based Tourism Contribute to Sustainable Development? Evidence from Residents’ Perceptions of the Sustainability. Tour Manag 2019, 70, 368–380. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.C.; Tong, Y. Community Citizenship Behavior in Rural Tourism Destinations: Scale Development and Validation. Tour Manag 2022, 89, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; González-Portillo, A. Limiting Rural Tourism: Local Agency and Community-Based Tourism in Andalusia (Spain). Tour Manag 2024, 104, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Toward a More Comprehensive Use of Social Exchange Theory to Study Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance 2016, 39, 588–596. [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Del Chiappa, G.; Sheehan, L. Residents’ Engagement and Local Tourism Governance in Maturing Beach Destinations. Evidence from an Italian Case Study. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2013, 2, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Tsai, B.-K.; Chen, H.-S. Residents’ Attitude toward Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Development: An Integration of Two Theories. Sustainability 2017, 9, 903–913. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Giron, S.; Vanneste, D. Social Capital at the Tourist Destination Level: Determining the Dimensions to Assess and Improve Collective Action in Tourism. Tour Stud 2019, 19, 23–42. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Gendered Theory of Planned Behaviour and Residents’ Support for Tourism. Current Issues in Tourism 2010, 13, 525–540. [CrossRef]

- Thyne, M.; Woosnam, K.M.; Watkins, L.; Ribeiro, M.A. Social Distance between Residents and Tourists Explained by Residents’ Attitudes Concerning Tourism. J Travel Res 2022, 61, 150–169. [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Draper, J.; Jiang, J. (Kelly); Aleshinloye, K.D.; Erul, E. Applying Self-Perception Theory to Explain Residents’ Attitudes about Tourism Development through Travel Histories. Tour Manag 2018, 64, 357–368. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Porras-Bueno, N.; Plaza-Mejía, M. de los Á. Explaining Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism. Ann Tour Res 2011, 38, 460–480. [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. An Examination of Locals’ Attitudes. Ann Tour Res 2009, 36, 723–726. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mubeen, R.; Iorember, P.T.; Raza, S.; Mamirkulova, G. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism: Transformational Potential and Implications for a Sustainable Recovery of the Travel and Leisure Industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 2, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident Attitudes toward Sustainable Community Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2010, 18, 575–594. [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.W.T.; Tung, V.W.S. Understanding Residents’ Attitudes Towards Tourists Through Implicit Stereotypes. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2023, 49, 99–116. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; López Palomeque, F.; Ivars-Baidal, J.; Vera-Rebollo, F. Thoughts on Spanish Urban Tourism in a Post-Pandemic Reality: Challenges and Guidelines for a More Balanced Future. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2023, 9, 849–860. [CrossRef]

- Akhter Shareef, M.; Shakaib Akram, M.; Tegwen Malik, F.; Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Giannakis, M. An Attitude-Behavioral Model to Understand People’s Behavior towards Tourism during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Bus Res 2023, 161, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Lu, X.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, D. Understanding the Post-Pandemic Travel Intentions Among Chinese Residents: Impact of Sociodemographic Factors, <scp>COVID</Scp> Experiences, Travel Planned Behaviours, Health Beliefs, and Resilience. International Journal of Tourism Research 2024, 26, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Blackie, I.R.; Tsholetso, T.; Keetile, M. Residents’ Attitudes, Perceptions and the Development of Positive Tourism Behaviours amid COVID -19. Cogent Soc Sci 2023, 9, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour Manag Perspect 2021, 37, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, D.; Steenberghen, T.; Neuts, B. Covid-19 and Tourism Opportunities in Rural Flanders (Belgium). In Over-tourism and “tourism over”: Recovery from COVID-19 tourism crisis in Regions with over- and under-tourism; Trono, A., Duda, A.T., Schmude, J., Eds.; World Scientific Publisher, 2022.

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be Careful What You Wish For. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 577–598. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in Rural Tourism: Do Lifestyle Motivations Contribute to Management Practices That Enhance Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2020, 44, 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Laws, E. Tourism Crises and Disasters: Enhancing Understanding of System Effects. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2006, 19, 149–158. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.R.; Park, J.; Li, S.N.; Song, H. Social Costs of Tourism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Tour Res 2020, 84, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chou Wong, J.W.; Wai Lai, I.K. The Mechanism Influencing the Residents’ Support of the Government Policy for Accelerating Tourism Recovery under COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2022, 52, 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and Implications for Advancing and Resetting Industry and Research. J Bus Res 2020, 117, 312–321. [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism, Sustainable Development and the Theoretical Divide: 20 Years On. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2020, 28, 1932–1946. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G.; Amore, A. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives; Channel View Publications, 2018;

- Lamhour, O.; Safaa, L.; Perkumienė, D. What Does the Concept of Resilience in Tourism Mean in the Time of COVID-19? Results of a Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1–23.

- Vale, L.J. The Politics of Resilient Cities: Whose Resilience and Whose City? Building Research & Information 2014, 42, 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Resilience in Tourism : Development, Theory, and Application. In Tourism, Resilience and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change; Cheer, J.M., Lew, A.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2018; pp. 18–33 ISBN 9781315464053.

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. On the Suitability of Assessment Tools for Guiding Communities towards Disaster Resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2016, 18, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M. Human Flourishing, Tourism Transformation and COVID-19: A Conceptual Touchstone. Tourism Geographies 2020, 514–524. [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Kim, J.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Ash, K. Does Tourism Matter in Measuring Community Resilience? Ann Tour Res 2021, 89, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Avoiding Panic during Pandemics: COVID-19 and Tourism-Related Businesses. Tour Manag 2021, 86, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Seyfi, S.; Shahi, T. Tourism SMEs’ Resilience Strategies amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: The Story of Survival. Tourism Recreation Research 2023, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Romão, J. Tourism, Smart Specialisation, Growth, and Resilience. Ann Tour Res 2020, 84, 102995. [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Karamustafa, K. Impact of an Economic Crisis. Evidence from Turkey. Ann Tour Res 2005, 32, 942–961. [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.E.; Moser, S.C.; Ratick, S.J.; Dow, K.; Meyer, W.B.; Emani, S.; Jin, W.; Kasperson, J.X.; Kasperson, R.E.; Schwarz, H.E. Assessing the Vulnerability of Coastal Communities to Extreme Storms: The Case of Revere, MA., USA. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 1998, 3, 59–82. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Resilience Theory and Tourism. In Resilient Destinations and Tourism; Saarinen, J., Gill, M.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2018; pp. 1–14 ISBN 9781315162157.

- Frey, B.S.; Savage, D.A.; Torglerb, B. Interaction of Natural Survival Instincts and Internalized Social Norms Exploring the Titanic and Lusitania Disasters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 4862–4865. [CrossRef]

- El Korchi, A. Survivability, Resilience and Sustainability of Supply Chains: The COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clean Prod 2022, 377, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wakil, M.A.; Sun, Y.; Chan, E.H.W. Co-Flourishing: Intertwining Community Resilience and Tourism Development in Destination Communities. Tour Manag Perspect 2021, 38, 100803. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H. (Joan); Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of Rural Revitalization on Rural Tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 47, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; 5th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2018; ISBN 9781506386706.

| Study Case | Population (Except Children) | Sample Size | Sample to Population Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baños (D) | 9266 | 101 | 12% |

| Sayausí (TC) | 4475 | 105 | 31% |

| Migüir (TC) | 160 | 100 | 98% |

| Agro-ecological producers of the Austro (CA) | 4071 | 100 | 28% |

| Tsuer Entsa (D) | 150 | 100 | 91% |

| Naranjal Cluster (D) | 560 | 110 | 60% |

| 6 de Julio (D) | 949 | 109 | 73% |

| Hat Museum (CA) | 4863 | 100 | 91% |

| Total | 24494 | 825 |

| Demographic Attribute | Category | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 43 |

| Female | 56.9 | |

| Not specified | 0.1 | |

| Work place | Inside the community | 80 |

| Outside the community | 20 | |

| Income dependence | Public sector | 24.1 |

| Private sector | 5 | |

| Own business/entrepreneurship | 58.2 | |

| No income | 12.1 | |

| No reply | 0.6 | |

| Link to tourism | Direct | 31.3 |

| Indirect | 68.7 | |

| Qualification | Primary school | 41.3 |

| Secondary school | 42.7 | |

| University | 10.1 | |

| Postgraduate | 0.8 | |

| No studies | 50.1 | |

| Gender | Min | 18 |

| Average | 38.7 | |

| Max | 83 |

| Sector | Code | Interviewed | Gender | Age | Format | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public sector | PS01 | Local government | Female | 39 | Virtual | 0:41:24 |

| PS02 | National government | Female | 58 | Virtual | 0:44:45 | |

| PS03 | Local government | Male | 51 | Virtual | 0:47:01 | |

| PS04 | Local government | Male | 35 | Virtual | 0:31:24 | |

| PS05 | Local government | Female | 46 | Virtual | 1:07:26 | |

| Private sector | BS01 | Businessman | Male | 54 | Face to face | 0:33:20 |

| BS02 | Businessman | Male | 48 | Face to face | 0:31:06 | |

| BS03 | Businessman | Female | 26 | Virtual | 0:36:09 | |

| BS04 | Businessman | Male | 32 | Virtual | 0:41:16 | |

| Local communities | LC01 | Local | Female | 31 | Face to face | 0:26:16 |

| LC02 | Local | Female | 24 | Face to face | 0:58:51 | |

| LC03 | Local | Female | 50 | Face to face | 1:14:49 | |

| LC04 | Local | Male | 38 | Face to face | 0:28:15 | |

| LC05 | Local | Male | 41 | Face to face | 0:27:46 | |

| LC06 | Local | Female | 34 | Face to face | 0:21:44 | |

| LC07 | Local | Male | 34 | Face to face | 0:20:12 | |

| LC08 | Local | Male | 71 | Face to face | 0:21:35 | |

| LC09 | Local | Male | 44 | Face to face | 0:26:55 | |

| LC10 | Local | Male | 45 | Face to face | 0:20:59 | |

| LC11 | Local | Female | 44 | Face to face | 0:25:29 | |

| LC12 | Local | Female | 31 | Face to face | 0:21:40 | |

| LC13 | Local | Male | 35 | Face to face | 0:45:41 | |

| LC14 | Local | Female | 30 | Face to face | 0:38:47 | |

| LC15 | Local | Male | 72 | Face to face | 0:25:32 | |

| LC16 | Local | Male | 61 | Face to face | 0:19:54 |

| Variable | Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 | Dimension 4 | Dimension 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improve trust (Q7) | 0.68 | ||||

| Help women (Q8) | 0.68 | ||||

| Help local prod. activities (Q6) | 0.67 | ||||

| Conflicts from tourism (Q2) | -0.54 | ||||

| Organised community (Q29) | 0.54 | ||||

| Employment/business tourism (Q4) | 0.51 | ||||

| Work in tourism (Q28) | 0.75 | ||||

| Active participation in tourism (Q1) | 0.73 | ||||

| Income from tourism (Q13) | 0.63 | ||||

| Quality of life (Q20) | 0.62 | ||||

| Insecurity (Q34) | 0.76 | ||||

| Trash (Q23) | 0.71 | ||||

| Water pollution (Q14) | 0.69 | ||||

| Prostitution/Alcohol/Drugs (Q25) | 0.63 | ||||

| Vehicular disorder (Q5) | 0.61 | ||||

| Cost of living increase (Q31) | 0.63 | ||||

| Tourism as a main activity (Q17) | 0.55 | ||||

| Cannot depend on tourism (Q9) | 0.59 | ||||

| Eigenvalues | 3.88 | 3.22 | 3.09 | 1.82 | 1.69 |

| VAR | 20.6% | 8.1% | 5.2% | 3.9% | 3.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).