Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Fermion-Boson Duality as a Key Connecting Symmetry, Duality, Gauge Theory, and Gravity Theory

1.3. Purpose and Structure of this Paper

- 1.

- To present an overview of the fermion-boson duality theory and its theoretical foundations (extended gamma matrices, transition functions, maintenance of gauge invariance, etc.).

- 2.

- 3.

1.4. Comparison with Existing Theories and Novelty of this Research

2. Conventional Quantum Field Theory and Unresolved Issues

2.1. Distinction Between Fermions and Bosons and Difficulties in Unified Treatment

2.2. Complexity of Gauge Fixing and Ghost Introduction and Opacity of Physical Interpretation

2.3. Ultraviolet Divergence Problem in High-Energy Regions and Lack of Consistency with Gravity

2.4. Challenges for High-Precision Measurements such as Anomalous Magnetic Moments and Vacuum Polarization

3. Separation of Spin-Statistics in Dual Description

3.1. Conventional Spin-Statistics Relation and New Perspective

- 1.

- Fermionic electron: Has spin and follows fermionic statistics

- 2.

- Fermionic photon: Has spin and follows fermionic statistics

- 3.

- Bosonic photon: Has spin 1 and follows bosonic statistics

- 4.

- Bosonic electron: Has spin 1 and follows bosonic statistics

3.2. Realization Examples in Condensed Matter Physics

3.2.1. Bosonic Electrons in Superconducting States

3.2.2. Massive Photons and Fermionic Photons

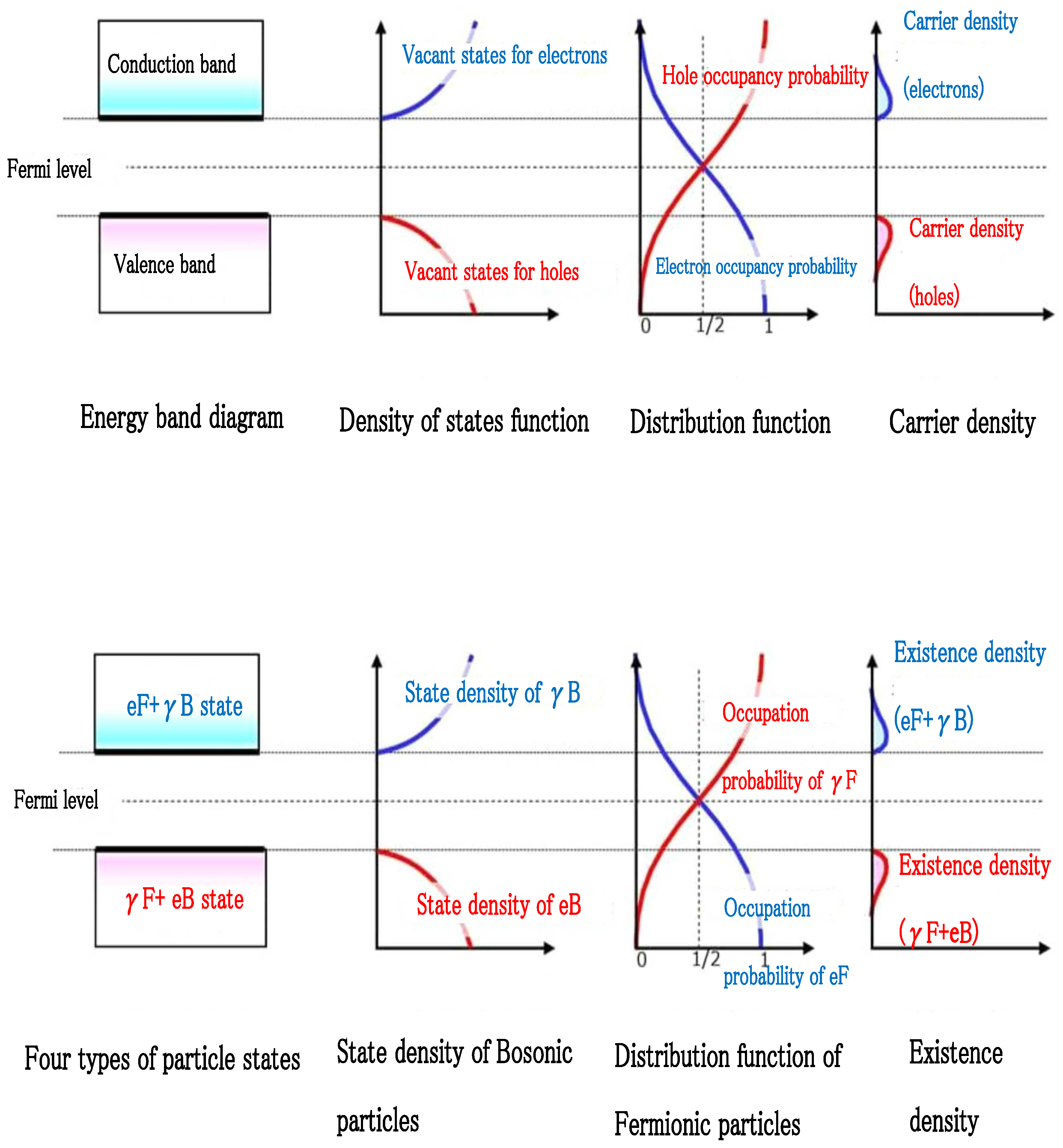

3.3. Correspondence with Semiconductor Physics

- Fermionic electron → Electron occupancy probability (n-type semiconductor)

- Fermionic photon → Hole occupancy probability (p-type semiconductor)

- Bosonic photon → Electron density of states function

- Bosonic electron → Hole density of states function

3.4. Statistical Transition Reactions and Spin Conservation

- Fermionic electron: Spin

- Bosonic photon: Spin 1

- Fermionic photon: Spin

- Bosonic electron: Spin 1

3.5. Mathematical Structure of Fermion-Boson Duality

- : Fermionic electron state,

- : Bosonic electron state,

- : Fermionic photon state,

- : Bosonic photon state.

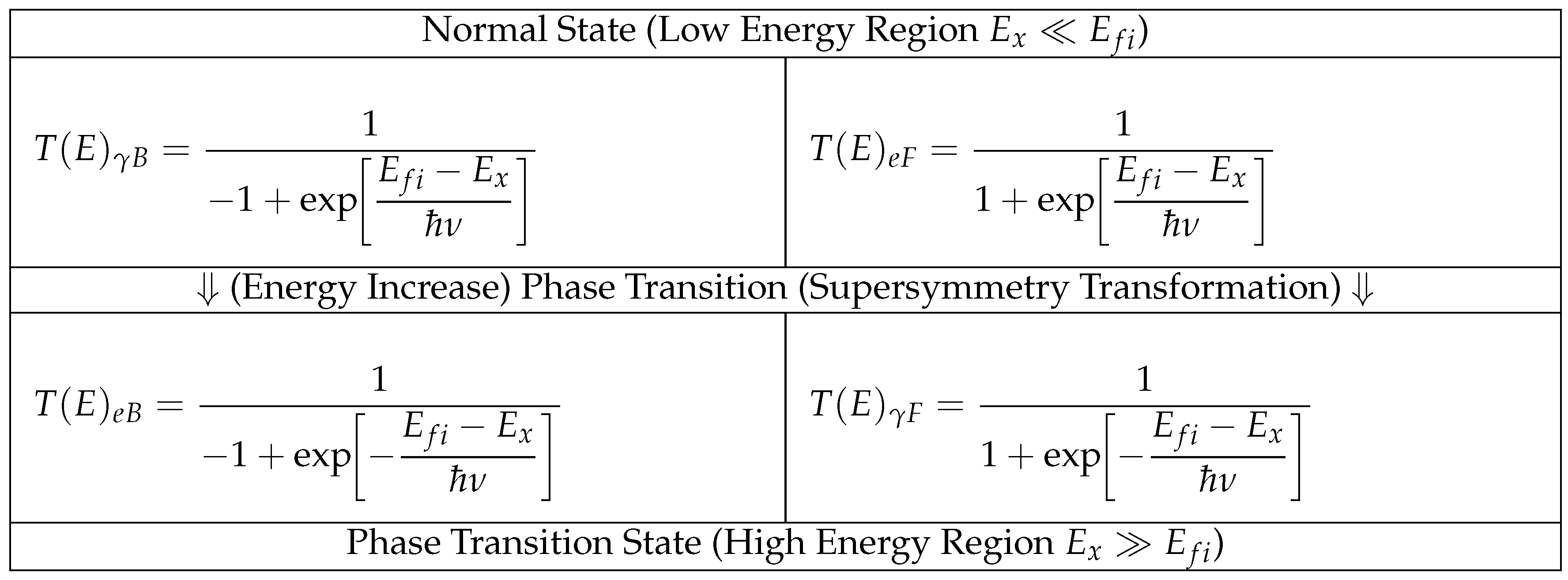

3.6. Introduction and Definition of Transition Functions

- is the characteristic energy at which statistical transition occurs,

- is the system’s energy (or a function of momentum),

- is a parameter characterizing the sharpness of the transition.

3.6.1. Physical Meaning and Boundary Conditions

3.6.2. Energy Scale Dependence

3.7. Extended Gamma Matrices and Dual Representation

3.8. Preservation of Gauge Invariance: A New Approach

3.8.1. Extended Lagrangian Structure

- represents the fermionic gamma matrices

- represents the bosonic gamma matrices

- is the conventional electromagnetic field tensor

- is the fermionic photon field tensor

3.8.2. Proof of Invariance Under Gauge Transformations

3.8.3. Automatic Restriction of Degrees of Freedom

3.8.4. Satisfaction of Ward-Takahashi Identity

4. Natural Regularization of Vacuum Polarization Effects

4.1. Finite Representation of Vacuum Polarization Using Transition Functions

General Form of the Vacuum Polarization Tensor

4.2. Natural Convergence of Loop Integrals

- is the electron propagator,

- are the transition functions indicating to what extent the "electron (fermionic component)" and "photon (fermionic component)" appear at momentum .

- In the high-momentum region, decays, reducing the integrand of the integral to approximately . This works as a natural cutoff, preventing ultraviolet divergences.

Form After Feynman Parameterization

- 1.

- : etc., resulting in small contributions

- 2.

- : The product of transition functions is maximized

- 3.

- : giving

4.3. Effective Charge and Running Coupling

Calculation Results Including Transition Functions

4.4. Comparison with Conventional Regularization Methods

- 1.

- Physical Interpretation of the Cutoff In conventional regularization, artificial cutoffs like need to be removed through renormalization. In this theory, serves as a statistical transition scale, representing a physically constrainable quantity rather than a "redundant parameter."

- 2.

- Agreement in Final Finite Results After actual renormalization, the same finite parts of the vacuum polarization function as those obtained through Pauli-Villars or dimensional regularization are reproduced. That is, the theory is compatible with precision tests in low-energy phenomena (such as electron g-2 and Lamb shift).

- 3.

- Theoretical Consistency The same transition functions can be applied not only to vacuum polarization but also to other QED processes, muon g-2 calculations, atomic structure, etc., eliminating the need to switch between different regularization schemes for each case. appears as a common scale, potentially explaining diverse experimental data across different experiments.

- 4.

- Verifiability of Additional Predictions If the energy region where statistical transition occurs is sufficiently low, the "fermionization/bosonization" of electrons and photons may be detected in future high-energy experiments. This opens the possibility for experimental verification as a prediction of new physical phenomena beyond mere regularization.

5. Applications: Precision Measurements and Predictions

5.1. Calculation of Electron Anomalous Magnetic Moment (g-2)

5.1.1. One-Loop Calculation Using Transition Functions

Modifications Under FB Duality Theory

5.1.2. Higher-Order Corrections and Comparison with Experiment

Example of Energy Dependence

Comparison with Experiment

- In summary, FB duality theory can reproduce one-loop and multi-loop corrections without disrupting the rigor of standard QED, while introducing a mechanism to transform the statistical nature of electrons and photons in high-energy extensions. Therefore, "consistent with known precision experiments, yet containing new physical phenomena" is an expected compatibility.

5.2. Application to Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment (g-2)μ

5.2.1. The Mystery of Muon g-2

5.2.2. One-Loop Calculation Using Transition Functions

5.2.3. Two-Loop Extension and Hadronic Contributions

Relationship with Hadronic Contributions

5.2.4. Determination of Characteristic Energy

Constraints from Other Physical Processes

there would be almost no impact on electron g-2, and for muons, since , it would take the form of "the low-energy limit QED result + a slight addition." It is suggested that this could produce a correction amount of the order observed in the experiment .

Example of Energy-Dependent Correction

- In conclusion, within the framework of this theory, there is a prospect of providing a consistent explanation for as well, particularly through multi-loop calculations including hadronic contributions, suggesting a new interpretation for the difference between the standard model and experimental values. As more precise experiments and theoretical analyses progress in the future, numerical constraints on the transition scale will become more stringent, potentially leading to the discovery of new physics.

5.3. Calculation of Lamb Shift and Agreement with Experimental Values

5.3.1. Lamb Shift Phenomenon

5.3.2. Calculation Framework Using Transition Functions

- is the fine structure constant,

- is the electron mass,

- c is the speed of light,

- is the value of the wave function at the origin for the hydrogen atom state.

Modification Terms in FB Duality Theory

5.3.3. Numerical Results and Comparison with Experiment

| (MeV) | Calculated Value (MHz) | Experimental Value (MHz) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1046 | |

| 500 | 1052 | |

| 1000 | 1056 | |

| 10000 | 1058 |

5.3.4. Physical Significance of GeV

- 1.

-

Large Separation from Electron MassIt is over 4 orders of magnitude larger than , suggesting that statistical transition (electrons becoming bosonized / photons becoming fermionized) is expected to manifest at much higher energies.

- 2.

-

Proximity to Electroweak Scale10–100 GeV is of the same order as the electroweak interaction energy scale, potentially suggesting a connection with electroweak symmetry breaking or other new physics.

- 3.

-

Consistency Across Different ExperimentsIn this theory, the same is expected to bring consistency across multiple precision physical quantities, spanning electron g-2, muon g-2, Lamb shift, etc. In other words, this suggests that is not a "mathematical cutoff" but a truly physical transition scale.

5.4. Isotope Effects and Predictions

Extension to Heavier Lepton Atoms such as Muonic Hydrogen

- In conclusion, consistency with high-precision experimental values in Lamb shifts and isotope effects suggests that the FB duality theory not only functions as a "natural regularization mechanism requiring no cutoffs" but can also maintain the same precision as existing QED in the realm of atomic physics fine structure and hyperfine structure. This is an important result supporting the validity and versatility of this theory.

6. New Perspectives on Symmetry and Statistics

6.1. Relation to Anyonic Phase Factors

- : , , therefore (fermionic behavior)

- : , , therefore (bosonic behavior)

- : , therefore (intermediate statistics)

6.2. Continuous Interpolation of Statistical Properties and Physical Interpretation

6.3. Prediction of New Phenomena in High-Energy Regions

6.4. Temperature Effects and Statistical Mechanical Correspondence

7. Implications for Quantum Gravity

7.1. Mechanism of Gravitational Field Generation

7.2. Unified Understanding of Gauge Theory and Gravity

7.3. Metric Tensor and Extended Gamma Matrices

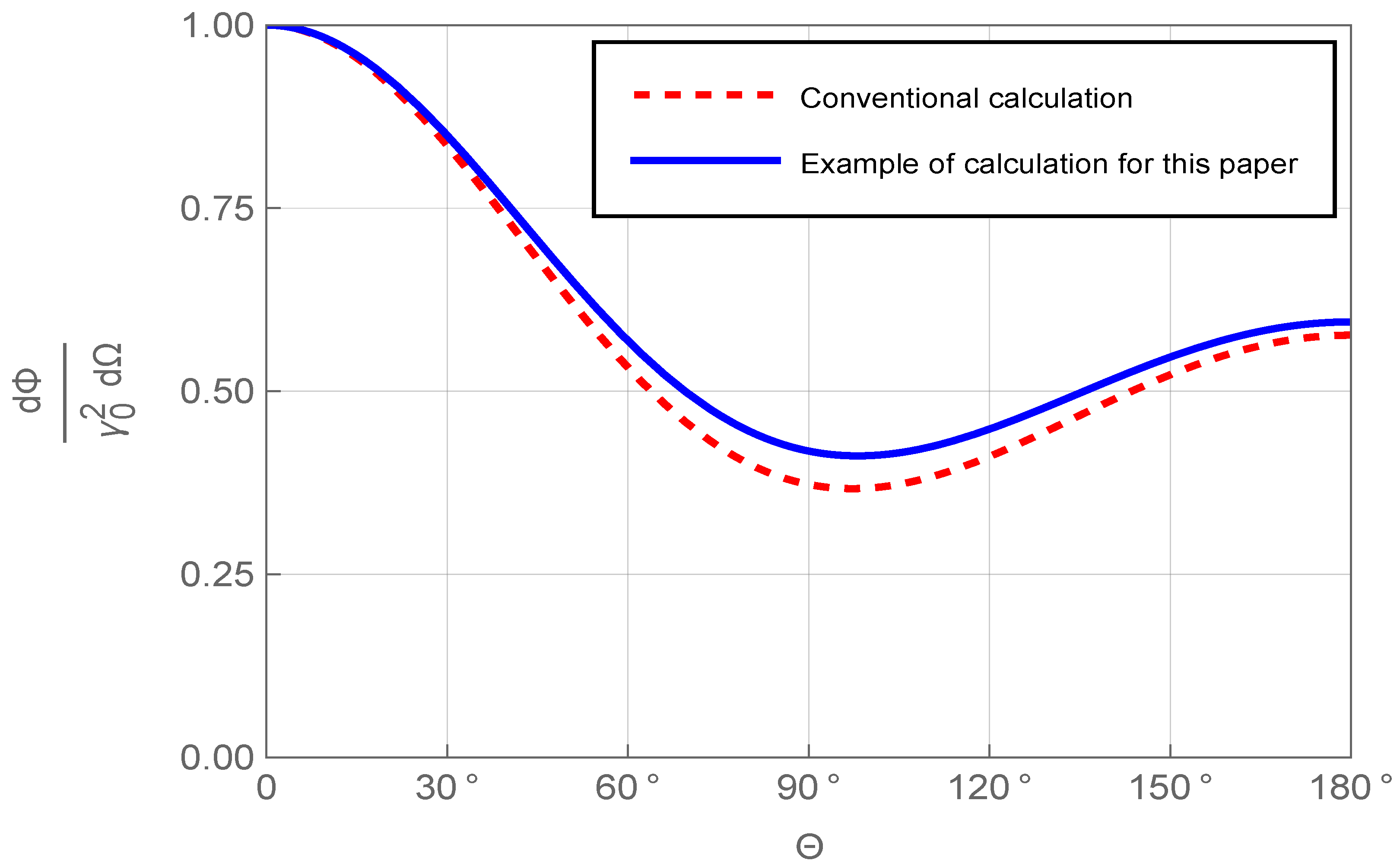

7.3.1. Application of Extended Gamma Matrices to Compton Scattering Calculations

7.3.2. Specific Impact of the Metric Tensor on Compton Scattering

7.3.3. Specific Steps for Compton Scattering Calculation

7.3.4. Comparison of Calculation Results in Minkowski Spacetime and Curved Spacetime

7.3.5. Physical Interpretation and Experimental Significance

8. Conclusions and Prospects

8.1. Experimental Verifiability of the Theory

8.2. Applications to Physics Beyond the Standard Model

8.3. Theoretical Developments and Future Challenges

8.4. Final Considerations

About Obtaining Mathematica Calculation Codes

8.5. Code Structure

-

QED Processes

- –

- Compton Scattering

- –

- Bhabha Scattering

- –

- Møller Scattering

- –

- Muon Pair Production

-

Theoretical Foundations

- –

- Properties of Gamma Matrices

- –

- Definition and Verification of 4-dimensional and 256-dimensional Gamma Matrices

-

Detailed Scattering Process Calculations

- –

- Setting up Kinematic Variables

- –

- Calculation of Scattering Amplitudes

- –

- Derivation of Cross Sections

- –

- Comparison with Klein-Nishina Formula

- –

- Behavior in High Energy Limit

-

Other Interactions

- –

- Muon Decay Processes

Funding

Data Availability Statement

- Zenodo Archive: https://zenodo.org/records/14671381 (accessed on March 10, 2025)

- GitHub Repository: https://github.com/HM-Physics/FermionBosonDuality_QFT (accessed on March 10, 2025).

Acknowledgments

References

- Mathematical Detective Club. Strange Equations in Particle Physics: Fermion-Boson Duality in Quantum Electrodynamics. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B086SCJL3T, 2020. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B086SCJL3T (accessed on 10 March 2025) (in Japanese).

- Mathematical Detective Club. Strange Equations in Particle Physics: Fermion-Boson Duality in Quantum Chromodynamics. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B08NT3KCNC, 2020. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B08NT3KCNC (accessed on 10 March 2025) (in Japanese).

- Mathematical Detective Club. Strange Equations in Particle Physics: General Relativistic Dirac Equation and Scattering Cross Section Calculations. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B086ST51M3, 2020. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B086ST51M3 (accessed on 10 March 2025) (in Japanese).

- Mathematical Detective Club. On Quantum Gravity with Broken Spontaneous Symmetry: Strange Mathematical Formulas in Elementary Particle Theory. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B0CPCJYJWD, 2023. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B0CPCJYJWD (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Mathematical Detective Club. On Fermion/Boson Dual Quantum Electrodynamics: Strange Equations in Particle Theory. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B0CXN36G66, 2024. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B0CXN36G66 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Mathematical Detective Club. Quantum Chromodynamics with Fermion-Boson Duality: Strange Equations in Particle Theory. Kindle Edition; ASIN: B0DRD939DM, 2024. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B0DRD939DM (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Maruyama, H. Fermion-Boson Duality and Quantum Field Theory Using an Extended Dirac Equation. Zenodo, Preprint (not peer-reviewed), 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14649388 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175–1204.

- Schrieffer, J.R. Schrieffer: Theory of Superconductivity; Maruzen Planet: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; ISBN 4863450621 (in Japanese).

- ’t Hooft, G.; Veltman, M. Regularization and Renormalization of Gauge Fields. Nucl. Phys. B 1972, 44, 189–213. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics; Shokabo: Tokyo, Japan, 2012; ISBN 4785325100 (in Japanese).

- Faddeev, L.D.; Popov, V.N. Feynman Diagrams for the Yang–Mills Field. Phys. Lett. B 1967, 25, 29–30. [CrossRef]

- Christ, N.H.; Lee, T.D. Operator Ordering and Feynman Rules in Gauge Theories. Phys. Rev. D 1980, 22, 939–958. [CrossRef]

- Hanneke, D.; Fogwell, S.; Gabrielse, G. New Measurement of the Electron Magnetic Moment and the Fine-Structure Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 120801. [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.H.; Yu, C.; Zhong, W.; Estey, B.; Müller, H. Measurement of the Fine-Structure Constant as a Test of the Standard Model. Science 2018, 360, 191–195. [CrossRef]

- Kusch, P.; Foley, H.M. The Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Phys. Rev. 1948, 74, 250–263.

- Abi, B.; et al. [Muon g-2 Collaboration]. Measurement of the Positive Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment to 0.46 ppm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 141801. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.W.; et al. [Muon g-2 Collaboration]. Final Report of the E821 Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment Measurement at BNL. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 73, 072003. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Nio, M. Theory of the Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Electron and the Muon. Atoms 2019, 7, 28.

- Eides, M.I.; Grotch, H.; Shelyuto, V.A. Theory of Light Hydrogenic Bound States. Phys. Rep. 2001, 342, 63–261.

- Karshenboim, S.G. Precision Study of Positronium: Testing Bound State QED Theory. Phys. Rep. 2005, 422, 1–63. [CrossRef]

- Jentschura, U.D.; Evers, J. Physically Measurable Effects of Projected Transformations: A Proposal for Lamb Shift Experiments in Hydrogenlike High-Z Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 253601.

- Mohr, P.J.; Taylor, B.N.; Newell, D.B. CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 633–730. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.P. A Supersymmetry Primer. In Perspectives on Supersymmetry II; Kane, G.L., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018; arXiv:hep-ph/9709356v7 (updated 2016).

- Wess, J.; Bagger, J. Supersymmetry and Supergravity; Maruzen Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; ISBN 4621084461 (in Japanese).

- Wess, J.; Zumino, B. Supergauge Transformations in Four Dimensions. Nucl. Phys. B 1974, 70, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Nekrasov, N.A. Noncommutative Field Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 977–1029.

- Szabo, R.J. Quantum Field Theory on Noncommutative Spaces. Phys. Rep. 2003, 378, 207–299. [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H.; Glashow, S.L. Unity of All Elementary Particle Forces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1974, 32, 438–441. [CrossRef]

- Pati, J.C.; Salam, A. Lepton Number as the Fourth Color. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 10, 275–289. [CrossRef]

- Slansky, R. Group Theory for Unified Model Building. Phys. Rep. 1981, 79, 1–128. [CrossRef]

- Sueyasu, T. Introduction to Optical Devices: pn Junction Diodes and Optical Devices; Corona Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; ISBN 4339009105 (in Japanese).

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed.; Maruzen: Tokyo, Japan, 2005; ISBN 4621076531 (in Japanese).

- Maruyama, H. Application of the Hill–Wheeler Formula in Statistical Models of Nuclear Fission: A Statistical–Mechanical Approach Based on Similarities with Semiconductor Physics. Entropy 2025, 27(3), 227. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.C. An Identity in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1950, 78, 182.

- Takahashi, Y. On the Generalized Ward Identity. Il Nuovo Cimento 1957, 6, 371–375.

- Sakamoto, M. Quantum Field Theory (II); Shokabo: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; ISBN 4785325127 (in Japanese).

- Schwinger, J. On Quantum-Electrodynamics and the Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 416–417. [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Low, F.E. Quantum Electrodynamics at Small Distances. Phys. Rev. 1954, 95, 1300–1312. [CrossRef]

- Stückelberg, E.C.G.; Petermann, A. La Normalisation des Constantes dans la Théorie des Quanta. Helv. Phys. Acta 1953, 26, 499–520.

- Burkhardt, H.; Pietrzyk, B. Low Energy Hadronic Contribution to the QED Vacuum Polarisation. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 013008. [CrossRef]

- Pauli, W.; Villars, F. On the Invariant Regularization in Quantum Field Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1949, 21, 434–444.

- ’t Hooft, G.; Veltman, M. Diagrammar; CERN Report No. 73-9, 1973.

- Feynman, R.P. Relativistic Cut-Off for Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1948, 74, 1430–1438. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.J. The S Matrix in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1949, 75, 1736–1755.

- Kinoshita, T., Ed. Quantum Electrodynamics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1990.

- Davier, M.; et al. Reevaluation of the hadronic vacuum polarisation contributions to the Standard Model predictions of the muon g − 2 and . Eur. Phys. J. C 2011, 71, 1515.

- Jegerlehner, F. The Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Muon; Springer Tracts in Modern Physics, 274; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017.

- Moroi, T. The Muon Anomalous Magnetic Dipole Moment in the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 53, 6565–6575.

- Stockinger, D. The Muon Magnetic Moment and Supersymmetry. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 2007, 34, R45–R92. [CrossRef]

- Athron, P.; et al. (GAMBIT collaboration). Global analyses of Higgs portal singlet dark matter models using GAMBIT. Eur. Phys. J. C 2019, 79, 38. [CrossRef]

- Capdevilla, R.; Delgado, A.; Martin, A.; Raj, N. Bounds on New Physics from the 2021 Muon g-2 Measurement. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 095005; arXiv:2105.06855 [hep-ph]. [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.A. The Electromagnetic Shift of Energy Levels. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 339–341.

- Lamb, W.E.; Retherford, R.C. Fine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom by a Microwave Method. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 241–243. [CrossRef]

- Lundeen, S.R.; Pipkin, F.M. Measurement of the Lamb Shift in Hydrogen: n=2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 46, 232–235. [CrossRef]

- Hagley, E.W.; Pipkin, F.M. Experimental Determination of the Lamb Shift in Hydrogen, n=2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 72, 1172–1175.

- Weitz, M.; Huber, A.; Schmidt-Kaler, F.; Hänsch, T.W. Precision Measurement of the Hydrogen 2S Lamb Shift. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 72, 328–331.

- Huber, A.; Weitz, M.; Udem, T.; Hänsch, T.W. Ultrahigh-resolution Spectroscopy of the 1S–2S Transition in Atomic Hydrogen and Deuterium. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 607–611; 1999, 59, 1844–1851.

- Burrows, C.R.; Ewart, P.; Stacey, D.N. Isotope Shift in the Lamb Shift of Hydrogen and Deuterium. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Phys. 1978, 11, 1451–1459.

- Lundeen, S.R.; Pipkin, F.M. Measurement of the Lamb Shift in Hydrogen (n=2) and Deuterium (n=2). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975, 34, 1368–1371; Phys. Rev. A 1981, 23, 701–706. [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Quantum Mechanics of Fractional-Spin Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 957–959. [CrossRef]

- Leinaas, J.M.; Myrheim, J. On the Theory of Identical Particles. Il Nuovo Cimento B 1977, 37, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Sato, H. Group and Physics; Maruzen Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; ISBN 4621300849 (in Japanese).

- Klein, O.; Nishina, Y. Über die Streuung von Strahlung durch freie Elektronen nach der neuen relativistischen Quantendynamik von Dirac. Z. Phys. 1929, 52, 853–868. [CrossRef]

| Isotope | Calculated Value (MHz) | Experimental Value (MHz) |

|---|---|---|

| 1H | 1058.0 | |

| 2H | 1059.2 | |

| 3H | 1059.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).