1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most studied illnesses in medical science in the last century. Even so, many of its mysteries remain unknown, such as the real causes that trigger the neurodegenerative process [

1]. It is known that many factors are associated with the biological processes that lead to cellular apoptosis in dementia. Among these, genetic characteristics and cardiovascular diseases stand out [

2,

3].

Other mental disorders, such as depression, have been linked to the onset of dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease [

4]. One significant aspect associated with severe depression is suicidal behavior [

5]. However, suicidality in Alzheimer’s disease remains a largely under-researched topic. A meta-analysis of 12 studies examining suicidal behavior in dementia found that individuals with Vascular Dementia were significantly more likely to experience suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] = 2.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06; 3.8) and attempt suicide (OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.28; 2.94) compared to those with Alzheimer’s disease, though there was no significant difference in mortality by suicide (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.69; 1.59). Additionally, individuals with Dementia with Lewy Bodies were significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.09; 2.23) than those with Alzheimer’s disease, but not more likely to attempt suicide (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.83; 1.50). Furthermore, people with Frontotemporal Dementia were significantly more likely to attempt suicide (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.02; 5.72) compared to individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, although they did not report significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 0.34; 8.33). Finally, those with Mixed Dementia were substantially more likely to attempt suicide (OR = 2.83, 95% CI = 1.52; 5.27) than those with Alzheimer’s disease but did not report significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 0.5; 5.46) [

6].

In an effort to delve deeper into the connections between Alzheimer’s disease and suicide, a thorough systematic review revealed a number of significant links between the two conditions. Key factors that emerged from the analysis were the role of depression, which often accompanies cognitive decline, and the presence of the e4 allele of apolipoprotein E, a genetic variant that has been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. These findings highlight the complex interplay between neurodegeneration and mental health, underscoring the importance of addressing both issues in clinical settings [

7].

Currently, there is a notable absence of research focusing on the historical context of suicidal behavior among individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The primary objective of this study is to delve into and analyze the patterns of suicidal behavior experienced by these patients, as well as to assess their overall quality of life. By exploring these critical aspects, the study seeks to contribute valuable insights to the understanding of the psychological and emotional challenges faced by those living with Alzheimer’s disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Source Population

The participants in this study were selected from a pool of 11,739 patients treated at the psychogeriatrics outpatient clinic in São Paulo, Brazil. Of these patients, 568 were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease between 2016 to 2024.

This study is a preliminary result of case-control research, with a total sample of 150 participants. It included the first third of the cases and controls (η = 50).

2.2. Sample Size

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly has been measured at 1.6% [

8]. If we consider a sampling error of 2% with a 95% confidence level, we will have a

η of 150.

- Formula for calculating sample size:

Where η is the sample size, Z2/2 is the critical value for the desired degree of confidence (1.96), p (0.016) is the proportion of favorable results of the variable in the population, q (0.984) is the proportion of unfavorable results in the population (q = 1-p), and E (0.02) is the standard error.

2.3. Diagnostic Criteria

Cases were defined as elderly individuals (people over 65 years of age) with Alzheimer’s disease. Controls were elderly individuals (people over 65 years of age) without a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis was made by the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS-ADRDA] [

9]. All participants underwent a diagnostic battery, including the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [RAVLT], Cambridge Cognitive Examination-Revised [CAMCOG-R], and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale cognitive [ADAS-cog] [

10,

11,

12]. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was certified by the DSM-V TR criteria [

13]. Brain

magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or

computerized tomography [CT] was performed to confirm hippocampal atrophy. Blood tests were performed to rule out other causes of cognitive disorders, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency. The severity of Alzheimer’s Disease was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR]

into minimal, intermediate, mild, moderate, and severe [

14]

. Individuals recruited with severe dementia classification were excluded. Remote memory was measured by recognizing photos of 5 famous Brazilian people in recent decades. Those who did not recognize at least three were excluded.

2.4. Instruments

Interpersonal variables were measured using Flanagan’s Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) and the Suicidal Behavior-Associated Facts Questionnaire (SAF-quest). All two instruments are validated in Portuguese [

15,

16]. The feasibility of both questionnaires was measured in a pilot study with health controls [

17].

2.5. Study Design

The case-control study was meticulously designed to evaluate the history of suicidal behavior and the overall quality of life among patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), while drawing comparative insights from a cohort of healthy control subjects. The investigation encompassed a total of 150 participants and was executed in two distinct phases, each integral to the study’s objectives. In the initial phase, participants underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation paired with advanced neuroimaging analyses. This thorough assessment was crucial to establish a clinical diagnosis based solely on observable symptoms and behavioral indicators associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Notably, at this stage, no biomarker testing was conducted, as the focus was primarily on clinical observations and imaging results to characterize the disease’s presentations. The second phase of the study introduced an examination of blood biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s Disease in all participant samples. This phase aimed to substantiate the clinical diagnoses made in patients who exhibited symptoms consistent with the Alzheimer’s Disease criteria. The diagnostic confirmation hinged upon the ATN classification system to categorize the presence of key pathological features: ’A’ signifies the presence of beta-amyloid plaques, ’T’ represents the detection of tau protein tangles, and ’N’ indicates evidence of neurodegeneration. This two-phased approach allowed researchers to holistically evaluate both the psychological and physiological aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease, providing a comprehensive understanding of its impact on individuals’ lives. [

18]. This phase of the study investigated the presence of significant differences in suicidal behavior among asymptomatic individuals who tested positive for biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). By exploring these aspects, the research enhances our comprehension of the relationship between AD and suicidal tendencies.

2.6. Data Analysis

Qualitative data were described in tables. Continuous variables were summarized as means and SDs; categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and proportions. Data from these participants were represented in tables to verify their characteristics. All analyses were carried out using IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

3. Results

It recruited 147 65-year-old individuals treated at the psychogeriatrics outpatient clinic at Unimed Bauru. Of these, 25 were included in the case group because they did meet the diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease; 25 were included in controls; 20 were included in the Pilot study [

17], and 25 were included in the adequacy study [

19]. Severe criteria in CDR excluded eight; another five were excluded due to great hearing difficulties; two were excluded because of the lack of recognition of at least three

famous Brazilian people. Other 37 did not agree to participate. All included participants understood the questionnaires.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in

Table 1. The Alzheimer’s group was significantly older than the control group (82.6 ± 8.0 years vs. 76.6 ± 6.0 years, p = 0.003). 64% were women; the age mean was 79.58 (±7.61); 52% were married. As expected, the prevalence of chronic illnesses was significantly higher in the Alzheimer’s group (84% vs. 12%, p < 0.001). Other demographic factors, such as sex distribution, marital status, living situation, education level, employment status, financial difficulties, alcohol/drug use, heroic behavior, and having children were similar between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

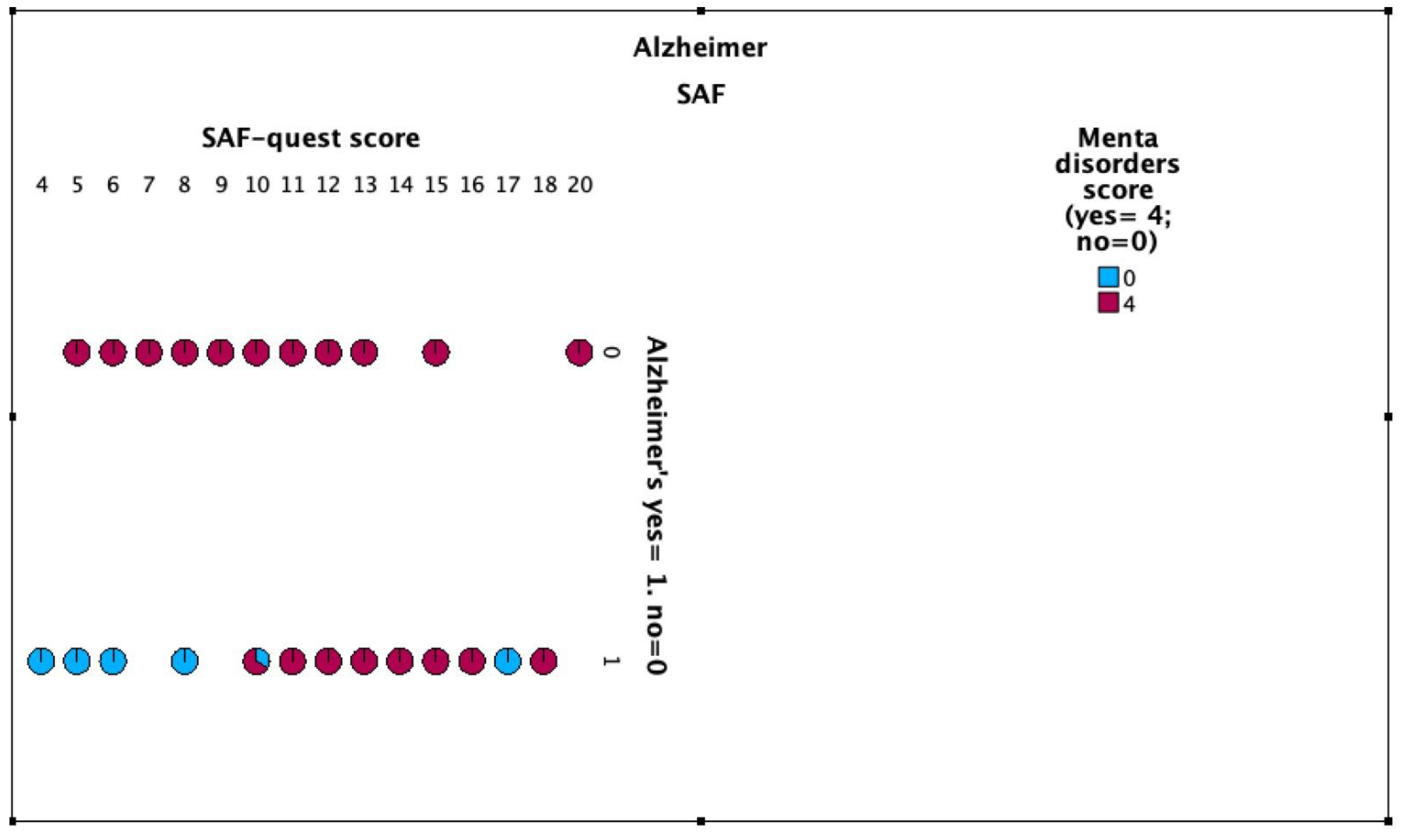

3.1. Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

12,5% of cases participants had suicidal ideation throughout life and 25% of the control group (OR for suicidal ideation = 0.432 [95% CI: 0.095-1.966]). 4% of cases participants attempted suicide throughout life and 8% of the control group (OR for suicide attempts = 0.479 [95% CI: 0.41-5.652]).

Figure 1 and

Figure 2,

Table 2.

While these findings suggest a trend towards lower rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in the Alzheimer’s group, the differences were not statistically significant, likely due to the small sample size. Interestingly, when asked if they would consider suicide in a hypothetical difficult situation, 16% of the Alzheimer’s group and 8% of controls answered affirmatively.

3.2. Psychiatric Diagnoses

The prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses is shown in

Table 3. Depression was more common in the Alzheimer’s group (24% vs. 4%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (OR: 7.67, 95% CI: 0.84-70.36). Other psychiatric diagnoses, including generalized anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, and vascular dementia, were rare in both groups, each with a prevalence of 4% or less in the Alzheimer’s group and 0% in the control group.

3.3. Quality of Life

Quality of life scores, as measured by the Flanagan’s Quality of Life Scale (QoLS), are presented in

Table 4. The Alzheimer’s group had significantly lower scores across multiple domains compared to the control group. These domains included material comfort (p = 0.006), health (p < 0.001), relationship with relatives (p = 0.022), intimate relationships (p = 0.031), close friends (p = 0.049), helping others (p = 0.044), public participation (p = 0.022), learning (p = 0.003), self-knowledge (p = 0.011), work (p < 0.001), creative communication (p = 0.003), active recreation (p < 0.001), entertainment (p = 0.016), and socialization (p = 0.010). The total QoLS score was also significantly lower in the Alzheimer’s group (68.1 ± 11.7 vs. 84.4 ± 9.4, p < 0.001).

3.4. Other Relevant Factors

Table 5 summarizes other factors that could be associated with suicidal behavior. No significant differences were found between the groups in terms of religiosity (88% in Alzheimer’s vs. 92% in controls, p = 1.000), belief in the afterlife (84% vs. 92%, p = 0.602), or having talked about suicide with someone (12% vs. 16%, p = 1.000). Childhood trauma was reported more frequently in the Alzheimer’s group (28% vs. 16%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.478). A history of a parent dying by suicide was present in 4% of the Alzheimer’s group and none in the control group (p = 1.000), while 8% of the Alzheimer’s group and none of the control group had a sibling who attempted suicide (p = 0.490).

Persons with Alzheimer’s disease demonstrate a worse quality of life and tend to have less suicidality

Both cases and controls did not demonstrate high patterns of suicidality. All patients in the control group had some other mental disorder, while some of the cases had only Alzheimer’s disease as a neuropsychiatric disorder.

4. Discussion

This preliminary study explored the intriguing relationship between lifetime suicidal behavior and Alzheimer’s disease. Our findings, while limited by the small sample size, suggest potential differences in the historical patterns of suicidal ideation and attempts between individuals with Alzheimer’s and the control group. We also found significant differences in quality of life, as well as a higher prevalence of reported childhood trauma in the Alzheimer’s group.

Contrary to the initial hypothesis that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease might exhibit higher rates of suicidal behavior, our results indicated a trend towards lower rates of both suicidal ideation (12.5% vs. 25%) and attempts (4% vs. 8%) compared to the control group. However, these differences did not reach statistical significance. This aligns with some previous research suggesting that the cognitive impairments associated with Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in executive functioning and planning, may hinder an individual’s ability to formulate and execute a suicide plan [

20].

Interestingly, while historical suicidal behavior appeared less frequent, a higher proportion of individuals with Alzheimer’s (16% vs. 8%) indicated they might consider suicide in a hypothetical difficult life situation. This could be related to several factors. First, individuals in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, as were included in our sample, may retain insight into their declining cognitive abilities and the potential future burden on their families, leading to increased distress and contemplation of suicide as an escape [

21]. Second, the significantly lower quality of life scores in the Alzheimer’s group across multiple domains, including health, social relationships, and engagement in activities, may contribute to a sense of hopelessness and a greater willingness to consider suicide in the face of adversity.

The higher prevalence of reported childhood trauma in the Alzheimer’s group (28% vs. 16%), although not statistically significant, is noteworthy. Childhood trauma is a well-established risk factor for suicidal behavior across the lifespan [

22]. It is possible that early-life adversity may have a long-term impact on emotional regulation and coping mechanisms, potentially increasing vulnerability to suicidal ideation in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. However, further research with larger samples is needed to confirm this association and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Our findings add to the growing body of literature on suicide in dementia, which has yielded mixed results. Some studies have reported an increased risk of suicide in individuals with dementia, particularly in the early stages [

23], while others have found no significant difference or even a decreased risk compared to the general population [

24]. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in study populations, diagnostic criteria, assessment methods, and the stage of dementia being investigated.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, the small sample size (n=50) limits the statistical power to detect significant differences and increases the risk of Type II error (false negatives). Therefore, the observed trends, particularly the lower rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in the Alzheimer’s group, should be interpreted with caution. Second, the cross-sectional design prevents us from establishing temporal relationships or causality between Alzheimer’s disease and suicidal behavior. It is possible that pre-existing factors, such as personality traits or coping styles, may influence both the risk of developing Alzheimer’s and the likelihood of experiencing suicidal ideation. Third, our assessment of suicidal behavior relied on retrospective self-report, which may be subject to recall bias, particularly in individuals with cognitive impairment. However, we attempted to mitigate this by excluding individuals with severe dementia and using validated questionnaires. Fourth, our control group, while matched for some demographic characteristics, may not fully represent the general population, as they were also recruited from a psychogeriatric outpatient clinic.

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable preliminary data and highlights several important directions for future research. Larger, prospective studies are needed to confirm the observed trends and further explore the complex interplay between Alzheimer’s disease, suicidal behavior, and associated factors. Future research should also investigate the role of specific cognitive deficits, such as impaired decision-making or impulsivity, in influencing suicide risk in dementia. Additionally, studies examining the impact of interventions aimed at improving quality of life, managing depression, and providing social support in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may shed light on potential strategies for suicide prevention in this vulnerable population. It would also be beneficial to explore the ethical considerations surrounding end-of-life decisions and advance directives in individuals with neurodegenerative diseases, considering their capacity for decision-making and their expressed wishes.

5. Conclusion

This preliminary data suggests an inverse relationship between suicidal behavior and the prevalence of AD, such as patients with AD may experience lower rates of suicidal thoughts and actions. These intriguing findings highlight an urgent need for more detailed and expansive studies that involve larger sample sizes, which would bolster the reliability and validity of the results.

Expanding the research framework is essential to thoroughly investigate the potential differences in suicidal behavior history among those diagnosed with AD compared to the general population throughout their lives. Such comprehensive examinations will shed light on the intricate mental health challenges faced by these two distinct groups, allowing for a better understanding of their unique psychological landscapes.

Ultimately, gaining deeper insights into this issue can pave the way for the development of more effective intervention strategies tailored specifically to meet the diverse needs of individuals dealing with AD, as well as those within the broader community. By addressing these complex issues, we can better support both populations, fostering improved mental health outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors approved the final version of the article submitted for publication.

Funding

The authors’ resources were used.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and submitted and approved by the ethics and research committee of the Faculty of Medicine of São José do Rio Preto, CAAE 65514822.2.0000.5415.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants signed a free and informed consent agreeing to the publication of the data without revealing their names or any other form of personal identification, such as address, etc.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the questionnaires used in this research are archived with the main researcher. To protect the identity of participants, they cannot be widely publicized. Scientists are available for consultation. Please feel free to send an email to julianofrr@terra.com.br and schedule a visit.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the volunteers who contributed to this study and Unimed for the availability of a location for the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the present study.

References

- Uzuner, D.; İlgün, A.; Düz, E.; Bozkurt, F.B.; Çakır, T. Multilayer Analysis of RNA Sequencing Data in Alzheimer’s Disease to Unravel Molecular Mysteries. Adv Neurobiol. 2024, 41, 219–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Sulaiman GM, Mohammed HA, Mohammed SG, Al-Gareeb AI, Albuhadily AK, et al. Amyloid-β and heart failure in Alzheimer’s disease: the new vistas. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025, 12, 1494101.

- Ren, Z.; Guan, Z.; Guan, Q.; Guan, H.; Guan, H. Association between apolipoprotein E ε4 status and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Neurosci. 2025, 26, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Su, W.; Cai, L. A bibliometric analysis of research on dementia comorbid with depression from 2005 to 2024. Front Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1508662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le GH, Wong S, Au H, Badulescu S, Gill H, Vasudeva S, et al. Association between rumination, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in persons with depressive and other mood disorders and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2025, 368, 513–27.

- Nuzum E, Medeisyte R, Desai R, Tsipa A, Fearn C, Eshetu A, et al. Dementia subtypes and suicidality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024, 169, 105995.

- Rodrigues, J.F.R.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Araújo Filho, G.M. Alzheimer’s Disease and Suicide: An Integrative Literature Review. Current Alzheimer Research. 2023, 20, 758–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥ 65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 17–24.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJ, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 263–9.

- Schultz, R.R.; Siviero, M.O.; Bertolucci, P.H.F. The cognitive subscale of the “Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale” in a Brazilian sample. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001, 34, 1295–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paradela, E.M.P.; Lopes, C.d.S.; Lourenço, R.A.

- public geriatric outpatient clinic. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009, 25, 2562–70.

- Cotta M, Malloy-Diniz L, Nicolato R, Moares ENd, Rocha F, Paula JJd.

- diagnosis of normal and pathological aging. Contextos Clínicos. 2012, 5, 10–25.

- Association, AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). [CrossRef]

- Montaño, M.B.M.M.; Ramos, L.R. Validaty of the Portuguese version of Clinical Dementia Rating. Rev Saúde Pública. 2005, 39, 912–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, J.F.R.; Araújo Filho, G.M.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Rubatino, F.V.M.; Fischer, H.; Payão, S.L.M. Development and validation of a questionnarie to measure association factors with suicide: An instrument for a populational survey. Health Science Reports. 2023, 62023, e1396. [Google Scholar]

- Guewehr, K. Teoria da resposta ao item na avaliação de qualidade de vida de idosos: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2007.

- Rodrigues JFR, Rodrigues LP, Atalaia da Silva KC, Rubatino FVM, Fischer H, Rodrigues FCP, et al. A Pilot Study to Research Associations between Alzheimer’s Disease and Suicide: The Questionnaire Feasibility. PrePrint. 2024, 2024051144.

- Jack Jr CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016, 87, 539–47.

- Rodrigues JFR, Rodrigues LP, Atalaia da Silva KC, Serna Rodriguez MF, Rubatino FVM, Fischer H, et al. Suicide History Scarcity in Alzheimer’s Disease: Adequacy and Acceptability Study. Preprint. 2024, 2024102149.

- Bredemeier, K.; Miller, I.W. Executive function and suicidality: A systematic qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015, 40, 170–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langa, K.M. Cognitive Aging, Dementia, and the Future of an Aging Population.. 2018. In: Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513075/.

- Barbosa LP, Quevedo L, da Silva Gdel G, Jansen K, Pinheiro RT, Branco J, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide risk in a sample of young individuals aged 14-35 years in southern Brazil. Child Abuse Negl. 2024, 38, 1191–6.

- Sinclair LI, Mohr A, Morisaki M, Edmondson M, Chan S, Bone-Connaughton A, et al. Is later-life depression a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease or a prodromal symptom: a study using post-mortem human brain tissue? Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023, 15, 153.

- Mohamad, M.A.; Leong Bin Abdullah, M.F.I.; Shari, N.I. Similarities and differences in the prevalence and risk factors of suicidal behavior between caregivers and people with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).