1. Introduction

Alarmed by the high rates of suicide among people with Alzheimer's disease, the revision of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) brought a paragraph to inform mental health professionals of the importance of observing suicidal behavior in this audience.[

1] The DSM-5-TR reports on Danish hospital studies, which found a 3- to 8-fold increase in suicidal behavior compared to elderly people without dementia.

In a study of elderly individuals in Brazil, it was found that 11.3% reported having suicidal thoughts, while 6.9% had attempted suicide at some point in their lives.[

2] From 2010 to 2022, there was a 100.37% increase in suicides among the elderly in the state of São Paulo, which is the most populous in Brazil.[

3]

In this context of increasing rates of suicide and Alzheimer's disease, a review was conducted in search of common factors between both diseases. This study listed interpersonal, genetic, and neurochemical factors, with depression and the presence of the E4 allele of apolipoprotein-E being the most important.[

4] More than providing answers, we observed a vast field of investigation that needs to be better explored.

Pursuing the goal of fulfilling the role of science, our group began to outline a line of research in search of associations between Alzheimer's disease and suicide. First, it was conducted a feasibility study of two instruments to investigate interpersonal factors that may be interconnected with Alzheimer's disease and suicide. The healthy elderly demonstrated excellent understanding on time, which gave us peace of mind to proceed with our investigations.[

5] Subsequently, this study aims to test the same two instruments in Alzheimer's patients to assess their adequacy and acceptability to investigate the history of behaviors and factors associated with suicidal behavior across the lifespan in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Source Population

The participants in this study were selected from a pool of 9796 patients treated at the psychogeriatrics outpatient clinic at Unimed Bauru. Bauru is in the geographic center of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, with a population of approximately 400,000 residents, and it serves a region of roughly 1 million people.

This study is a preliminary result of case-control research, with a total sample of 150 participants. It included the first third of the cases of Alzheimer's disease (n = 25).

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria

The Alzheimer's disease diagnosis was made by the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA).[

6] All participants underwent a diagnostic battery, including the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), Cambridge Cognitive Examination-Revised (CAMCOG-R), and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale cognitive (ADAS-cog).[

7,

8,

9] The diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease was certified by the DSM-V TR criteria.[

10] Brain

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or

computerized tomography (CT) was performed to confirm hippocampal atrophy. Blood tests were performed to rule out other causes of cognitive disorders, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency. The severity of Alzheimer’s Disease was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)

into minimal, intermediate, mild, moderate, and severe.[

11]

Individuals recruited with severe dementia classification were excluded. Remote memory was measured by recognizing photos of 5 famous Brazilian people in recent decades. Those who did not recognize at least three were excluded.

2.3. Instruments

Interpersonal variables were measured using Flanagan’s Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) and the Suicidal Behavior-Associated Facts Questionnaire (SAF-quest). All two instruments are validated in Portuguese.[

12,

13] The feasibility of both questionnaires was measured in a pilot study with health controls.[

5]

2.4. Sample Size

To measure adequacy and acceptability, it was proposed to have 10% of a total study sample or 30 participants in large samples. The total sample of cases of the Alzheimer’s group will be 75 participants, so 10% corresponds to 7 or 8. Samples with fewer than 15 participants demonstrated inadequacy. So, for this study, a strategy was used to select the first third of participants, 25 patients.

2.5. Data Analysis

Adequacy was measured by comprehension of the questionnaires. Acceptability was measured by understanding the study object, which asked participants to describe their quality of life and the will to live in the questions of both questionnaires. The facial expressions, speaking intonations, and descriptive ideations were considered to observe acceptability.

Qualitative data were described in tables. Continuous variables were summarized as means and SDs; categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and proportions. Data from these participants were represented in tables to verify their characteristics. All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 29.

3. Results:

It recruited 99 65-year-old individuals treated at the psychogeriatrics outpatient clinic at Unimed Bauru. Of these, 67 were not included because they did not meet the diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Severe criteria in CDR excluded six; another five were excluded due to great hearing difficulties; one was excluded because of the lack of recognition of at least three famous Brazilian people.

The average age of the sample was 83.88 (±6.99) years old, and 52% were women.

All included participants understood the questionnaires. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 8%, and 4% had attempted suicide at some point in their lives.

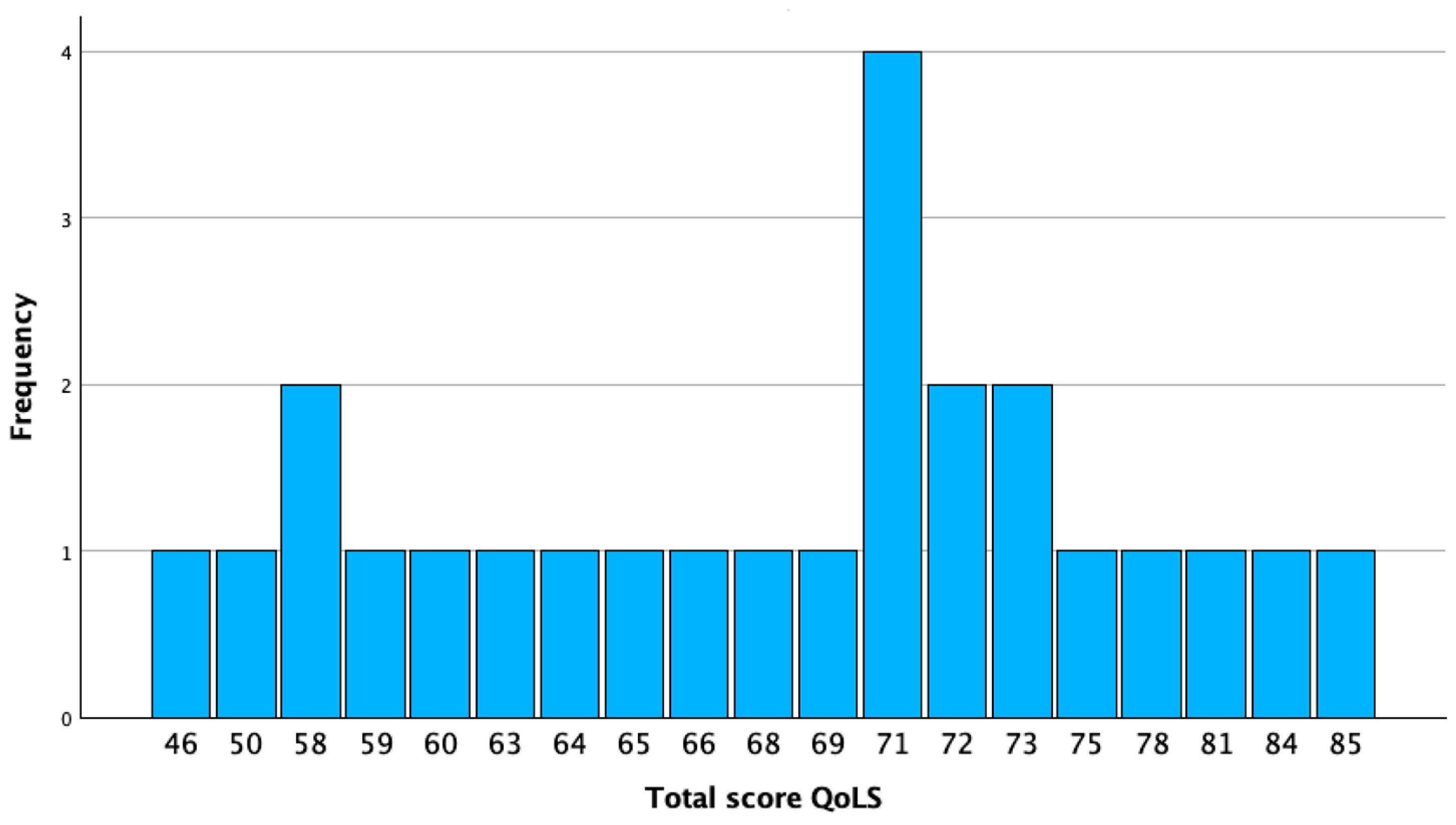

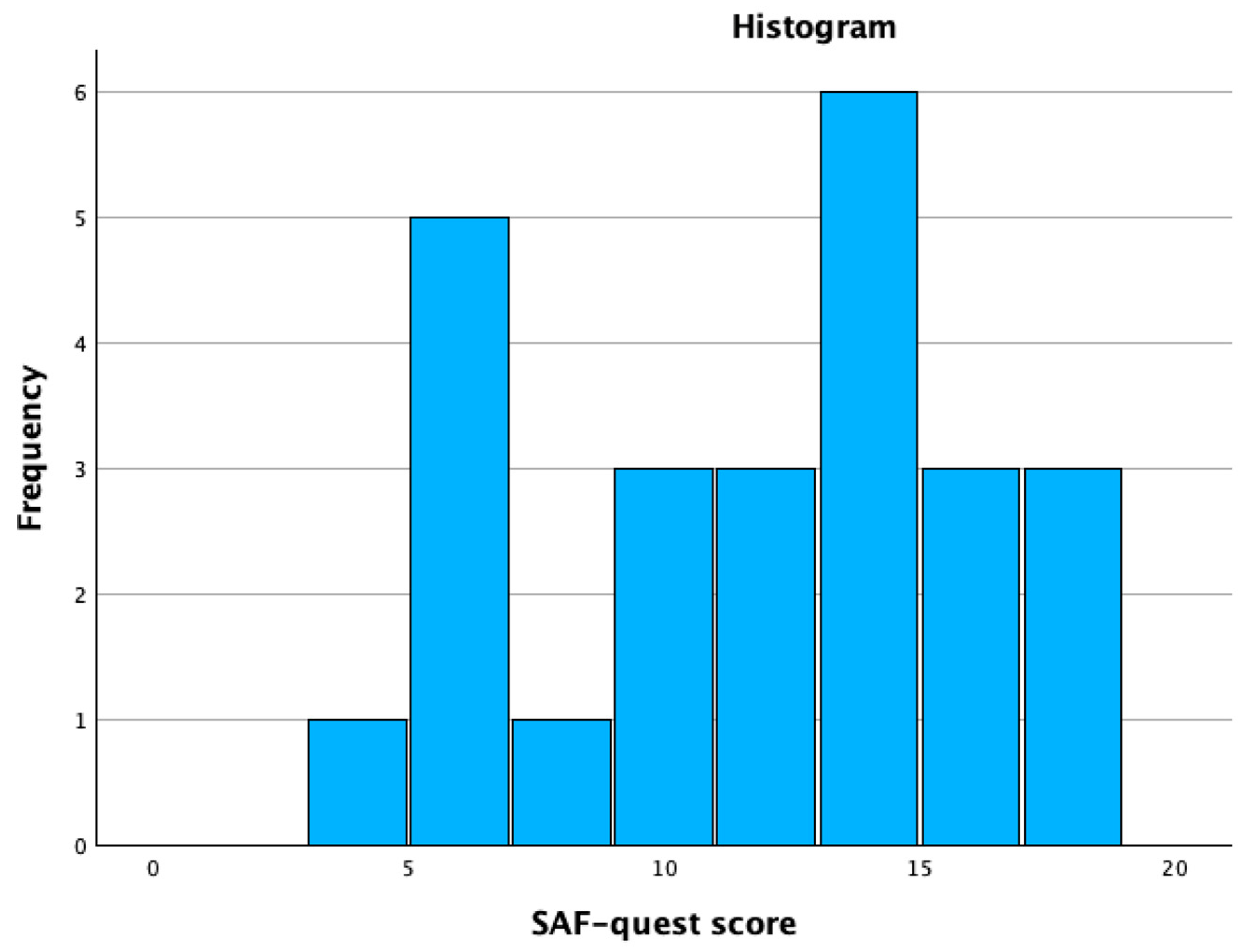

The total score of QoLS can range from 15 to 105. QLoS total score ranged from 46 to 85 in this sample, with a median of 71 (61.5 to 73). A score from 0 to 45 was considered low quality of life, 46 to 74 as moderate quality, and greater than or equal to 75 as high quality of life. (Graphic 1) The total score of the SAF-quest can range from 0 to 40, with a score lower than ten being considered minimal suicidal behavior, mild suicidal behavior from 11 to 20, moderate from 21 to 30, and severe from 31 to 40. SAF-quest scores range from four to 18, with a median of 12 (7 to 14.5). (Graphic 2)

Graphic 1.

QoLS total score.

Graphic 1.

QoLS total score.

Graphic 2.

SAF-quest total score.

Graphic 2.

SAF-quest total score.

The adequacy was observed by qualitative descriptions on question 20 of the SAF-quest, demonstrating a good understanding of the proposed study objective. (

Table 1)

The facial expressions were classified as:

1 – Frown: Narrowed eyes and a furrowed forehead indicate that you don't have much positive expectation.

2 – Tie face: Visible facial irritation signifies concern and dissatisfaction.

3 – Absence: Not being able to focus your gaze and attention on the interlocutor shows nervousness, anxiety, and even shame.

4 – Sarcastic smile: Using sarcasm conveys the idea of arrogance.

5 – Sulk: Looking pale, with drooping cheeks, can indicate boredom.

6 – Staring: A fixed, studied look, filled with controlled emotion, is a sign of hopelessness.

7 – Happy: Shine in the eyes and smile on the lips.

The speaking intonations were classified as low, moderate, and high.

4. Discussion:

The research sample comprised individuals with an average age of approximately 84 years, thus offering a comprehensive portrayal of the elderly population in Brazil. Additionally, the nearly identical distribution across age groups further contributes to the favorable representation within this sample. The median of the QoLS demonstrated a moderate quality of life for the participants, and the median of the SAF-quest demonstrated mild suicidal behavior. These data indicate a good quality of life for the participants. The descriptive data in question 22 illustrate a state of resignation with their moment in life on the part of the participants.

As the population ages, the prevalence of cognitive disorders in the elderly increases. The search to understand the quality of life of people with Alzheimer's Disease today even considers virtual tools.[

14] As we enter a new era in the management of Alzheimer's disease, it has become increasingly important to evaluate the effectiveness of immunobiological treatments. These innovative therapies hold the potential not only to target the underlying mechanisms of the disease but also to enhance the overall quality of life for patients. Understanding their impact could serve as a crucial asset in optimizing care and support for those affected by this condition.[

15] Being able to certify a quality of life scale is an essential step for any study.

Many other interview studies and questionnaires on quality of life in Alzheimer's disease can be found.[

16] There are a few studies of suicidal behavior in people with Alzheimer's disease, many of them investigating suicide and people at risk for dementia.[

17,

18] However, research into suicidal behaviors in this population using scales is not well documented. This is the pioneering nature of this line of research. The SAF-quest demonstrated to be a powerful instrument to answer how the history of suicidality in Alzheimer’s disease.

This study did not conduct further statistical analyses because its primary goal was to determine if two questionnaires could be used with people who have Alzheimer's disease. However, it is notable that the participants had low rates of suicidal behavior in their life histories. Only 8% reported having suicidal thoughts, and 4% had attempted suicide at some point in their lives. These rates are lower than those informed for elderly individuals in Brazil, where 11.3% reported having suicidal thoughts and 6.9% had attempted suicide at some point in their lives.[

2]

Questions understood in this heterogeneous sample demonstrated the adequacy and acceptability of the instruments. This gives us the confidence to apply the questionnaires to a broad sample, where we can carry out more significant statistical measurements, which were not possible with this present study.

5. Conclusion:

The study showed that Alzheimer's disease patients generally had sufficient support, were receptive to treatment, and had a low incidence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors throughout their lives. With the certainty of the adequacy and acceptability of the instruments, it will be possible to work with a large number of people with Alzheimer's disease to understand their history of suicidal behavior better.

Funding

The authors' resources were used.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and was submitted and approved by the ethics and research committee of the Faculty of Medicine of São José do Rio Preto with CAAE: 65514822.2.0000.5415.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants signed a free and informed consent agreeing to the publication of the data without revealing their names or any other form of personal identification, such as address, etc.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the questionnaires used in this research are archived with the main researcher. To protect the identity of participants, they cannot be widely publicized. Scientists are available for consultation. Please feel free to send an email to julianofrr@terra.com.br and schedule a visit.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the volunteers who contributed to this study and Unimed for the availability of a location for the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the present study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.97808904257872022.

- Ciulla L, Nogueira EL, Silva Filho IGd, Tres GL, Engroff P, Ciulla V, et al. Suicide risk in the elderly: Data from Brazilian public health care program. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;152-154(1):513-6. [CrossRef]

- Rubatino Rodrigues JF, Rodrigues LP, Araújo Filho GM. Increase in suicide rates in the elderly population of the state of São Paulo, Brazil: Could Alzheimer's disease be a risk factor? Public Health. 2024;236:204-6. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues JFR, Rodrigues LP, Araújo Filho GM. Alzheimer's Disease and Suicide: An Integrative Literature Review. Current Alzheimer Research. 2023;20(11):758-68. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues JFR, Rodrigues LP, Atalaia da Silva KC, Rubatino FVM, Fischer H, Rodrigues FCP, et al. A Pilot Study to Research Associations between Alzheimer’s Disease and Suicide: The Questionnaire Feasibility. PrePrint. 2024:2024051144. [CrossRef]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJ, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-9. [CrossRef]

- Schultz RR, Siviero MO, Bertolucci PHF. The cognitive subscale of the "Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale" in a Brazilian sample. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34(10):1295-302. [CrossRef]

- Paradela EMP, Lopes CdS, Lourenço RA. Portuguese adaptation of the Cambridge Cognitive Examination-Revised in a public geriatric outpatient clinic. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25(12):2562-70. [CrossRef]

- Cotta M, Malloy-Diniz L, Nicolato R, Moares ENd, Rocha F, Paula JJd. The Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) on the differential diagnosis of normal and pathological aging. Contextos Clínicos. 2012;5(1):10-25. [CrossRef]

- Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.97808904257872022.

- Montaño MBMM, Ramos LR. Validaty of the Portuguese version of Clinical Dementia Rating. Rev Saúde Pública. 2005;39(6):912-7. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues JFR, Araújo Filho GM, Rodrigues LP, Rubatino FVM, Fischer H, Payão SLM. Development and validation of a questionnarie to measure association factors with suicide: An instrument for a populational survey. Health Science Reports. 2023;62023;6:e:e1396. [CrossRef]

- Guewehr K. Teoria da resposta ao item na avaliação de qualidade de vida de idosos: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2007.

- Fabara-Rodríguez AC, García-Bravo C, García-Bravo S, Quirosa-Galán I, Rodríguez-Pérez MP, Pérez-Corrales J, et al. Quality-of-Life- and Cognitive-Oriented Rehabilitation Program through NeuronUP in Older People with Alzheimer's Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Med. 2024;8(19):5982. [CrossRef]

- Parks AL, Thacker A, Dohan D, Gomez LAR, Ritchie CS, Paladino J, et al. "I'm worth saving"- A Qualitative Study of People with Alzheimer's Disease Considering Lecanemab Treatment. medRxiv [Preprint] [Internet]. 2024:[24313315 p.]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.17.24313315v1.

- Xing B, Li H, Hua H, Jiang R. Economic burden and quality of life of patients with dementia in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24(1):789. [CrossRef]

- Ng KP, Richard-Devantoy S, Bertrand J-A, Jiang L, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, et al. Suicidal ideation is common in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's desease at-risk persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(1):60-8. [CrossRef]

- Barak Y, Aizenberg D. Suicide amongst Alzheimer's Disease Patients: A 10-Year Survey. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:101-3. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

The answers to question 20 of the SAF-quest.

Table 1.

The answers to question 20 of the SAF-quest.

| |

Facial

expressions |

Speaking intonations |

Descriptive ideations |

| 1 |

Staring |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 2 |

Happy |

Moderate |

See their children and grandchildren well |

| 3 |

Absence |

Low |

Nothing |

| 4 |

Staring |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 5 |

Absence |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 6 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 7 |

Frown |

High |

Travel |

| 8 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Go to the beach |

| 9 |

Sulk |

Low |

Nothing |

| 10 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Travel |

| 11 |

Frown |

Low |

Walking without a cane |

| 12 |

Sarcastic smile |

Low |

Nothing |

| 13 |

Sulk |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 14 |

Tie face |

High |

Nothing |

| 15 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 16 |

Frown |

Moderate |

Have more money |

| 17 |

Sulk |

Low |

Nothing |

| 18 |

Sarcastic smile |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 19 |

Staring |

Low |

Nothing |

| 20 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 21 |

Absence |

Low |

Remarry |

| 22 |

Frown |

High |

Nothing |

| 23 |

Happy |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 24 |

Staring |

Moderate |

Nothing |

| 25 |

Tie face |

High |

Nothing |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).