Submitted:

16 May 2024

Posted:

17 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials And Methods

2.1. Source Population

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

- Understanding the questions of research instruments;

- Total response time of fewer than 30 minutes, as taking longer than this for each application of the questionnaires may make data collection for a large sample unfeasible or require many professionals with an exaggerated expenditure of human and financial resources;

- Data tends to be homogeneous, which is suitable for forming a control group.

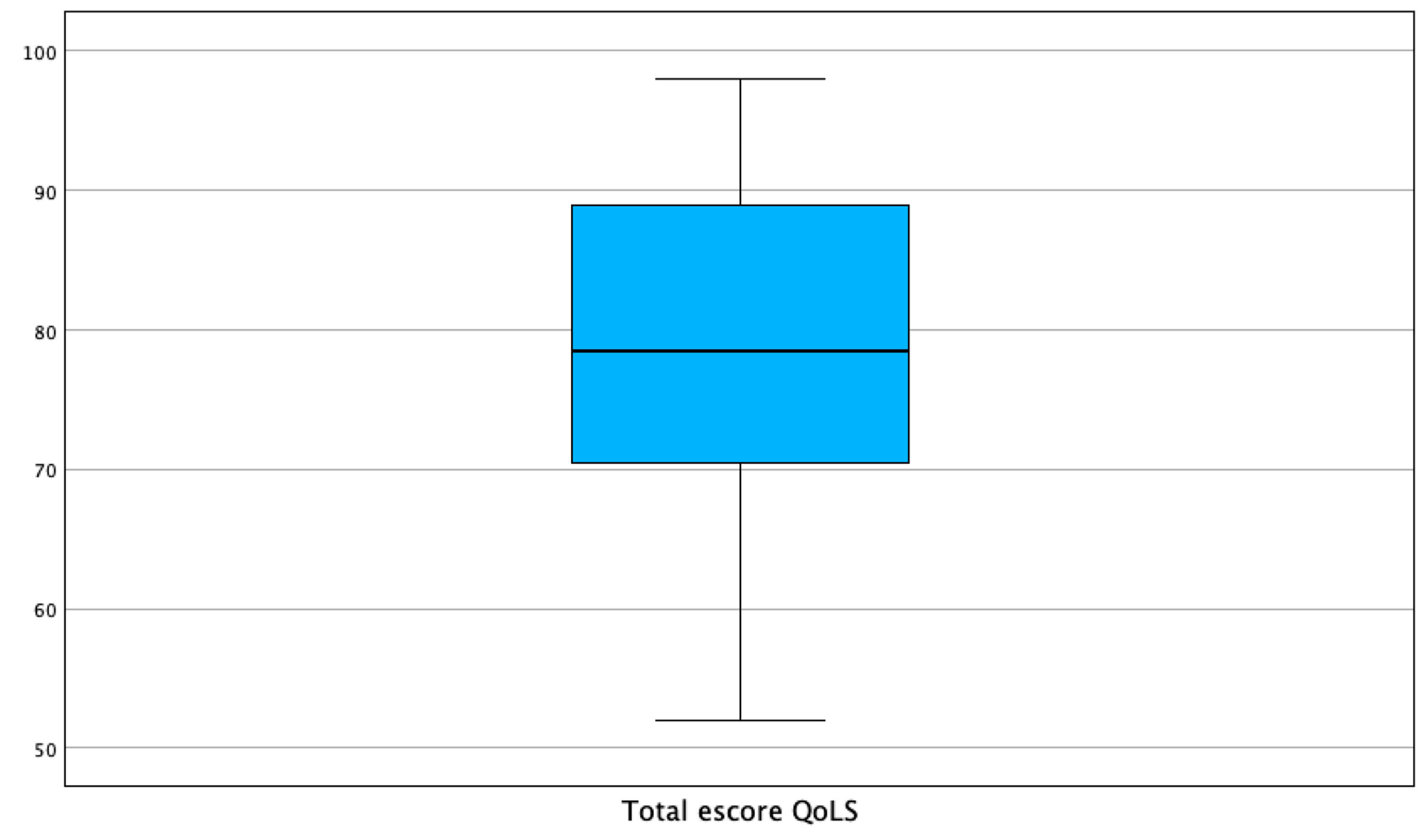

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

List of Abbreviations

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropin hormone |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ASA Theory | Alzheimer’s Disease and Suicide Associated Theory |

| BPSD | behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia |

| CRH | corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| CDK5 | cyclin-dependent kinase 5 |

| GAS | General Adaptation Syndrome |

| GCs | glucocorticoids |

| GSK-3 | glycogen synthase kinase 3 |

| GSK-3β | glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| HPA axis | hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| QoSL | Flanagan quality-of-life scale |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermeulen, R.J.; Roudijk, B.; Govers, T.M.; Rovers, M.M.; Rikkert, M.G.M.; Wijnen, B.F.M. Prognostic Information on Progression to Dementia: Quantification of the Impacton Quality of Life. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2024, 97, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, H.E.; Czippel, A.; Heydari, S.; Gawryluk, J.R.; Mazerolle, E.L. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Intrinsic functional connectivity strength of SuperAgers in the default mode and salience networks: Insights from ADNI. Aging Brain 2024, 5, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perneczky, R.; Dom, G.; Chan, A.; Falkai, P.; Bassetti, C. Anti-amyloi antibody treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-H.; Yao, X.-Y.; Tao, S.; Sun, X.; Li, P.-p.; Li, X.-x.; Liu, Z.-L.; Ren, C. Serotonin 2 Receptors, Agomelatine, and Behavioral and.

- Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Behav Neurol 2021, 5533827.

- Calsolaro, V.; Femminella, G.D.; Rogani, S.; Esposito, S.; Franchi, R.; Okoye, C.; Rengo, G.; Monzani, F. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD).

- and the Use of Antipsychotics. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, L.X.; Ong, S.C.; Tay, L.J.; Ng, T.; Parumasivam, T. Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Value Health Reg Issues 2024, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, M.F.; Mukai, Y.; Voss, T.; Kost, J.; Stone, J.; Furtek, C.; Mahoney, E.; Cummings, J.L.; Tariot, P.N.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. Further analyses of the safety of verubecestar in the phase 3 EPOCH trial of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, S.; Priefer, R. Alzheimer’s disease failed clinical trials. Life Sci 2022, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Bellomo, A.; Imbimbo, B.P. Do anti-amyloid- β drugs affect neuropsychiatric status in Alzheimer’s disease patients? Ageing Research Reviews 2019, 55, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

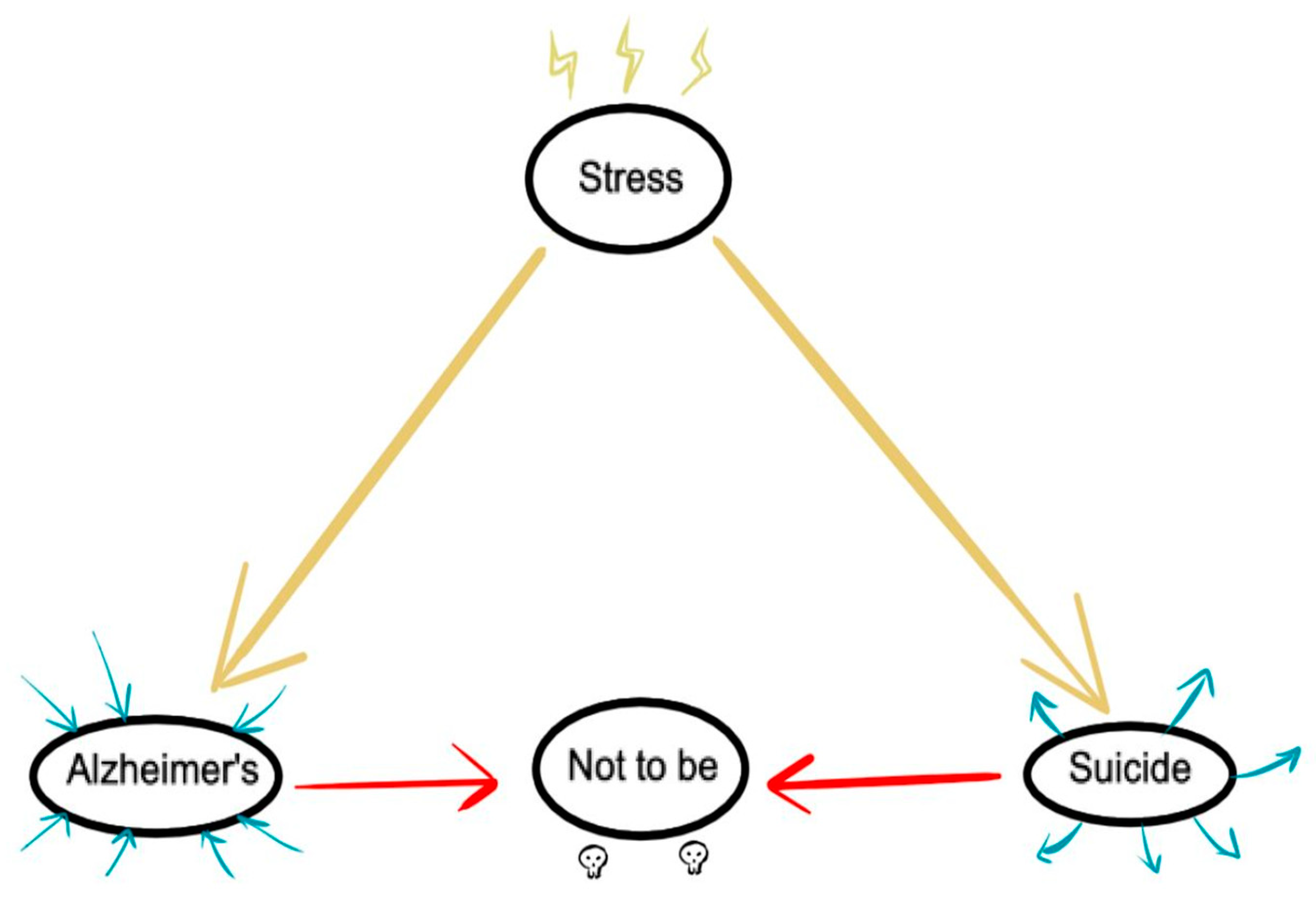

- Rodrigues, J.F.R.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Araújo Filho, G.M. Alzheimer’s Disease and Suicide: An Integrative Literature Review. Current Alzheimer Research 2023, 20, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! (11-13).

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Gónzalez-Maciel, A.; Rreynoso-Robles, R.; Delgado-Chávez, R.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Kulesza, R.J.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Ávila-Ramírez, J.; Villarreal-Ríos, R. Hallmarks of Alzheimer disease are evolving relentlessly in Metropolitan Mexico City infants, children and young adults. APOE4 carries have higher suicide risk and higher odds of reaching NFT stage V at ≤ 40 years of age. Environmental Research 2018, 164, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; González-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Kuleska, R.J.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Rönkkö, T.; Doty, R.L. Alzheimer’s disease and alpha-synuclein pathology in the olfactory bulbs of infants, children, teens and adults ≤ 40 years in Metropolitan Mexico City. APOE4 carriers at higher risk of suicide accelerate their olfactory bulb pathology. Enviromental Resesearch 2018, 166, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracha, H.S.; Kleinman, J.E. Postmortem Studies in Psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1984, 7, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, T.J.; Cross, A.J.; Cooper, S.J.; Deakin, J.F.W.; Ferrier, I.N.; Johnson, J.A.; Joseph, M.H.; Owen, F.; Poulter, M.; Lofthouse, R.; et al. Neurotransmitter receptors and monoamine metabolites in the brains of patients with Alzheimer-type Dementia and Depression, and Suicides. Neuropharmacology 1984, 23, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlson, G.D.; Ross, C.A.; Lohr, W.D.; Rovner, B.W.; Chase, G.A.; Folstein, M.F. Association Between Family History of Affective Disorder and the Depressive Syndrome of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990, 147, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferris, S.H.; Hofeldt, G.T.; Carbone, G.; Masciandaro, P.; Troetel, W.M.; Imbimbo, B.P. Suicide in Two Patients with a Diagnosis of Probable Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999, 13, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, U.; Kishikawa, Y.; Ricanati, E.; Friedland, R.P. Suicide and Alzheimer Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002, 10, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, Y.; Aizenberg, D. Suicide amongst Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A 10-Year Survey. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002, 14, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagé, V. Cognitive deficits in a suicidal depressed alzheimer’s patient: a specific vulnerability? Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 2014, 29, 326–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer, D.C. Comorbidity between neurological illness and psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectrums 2016, 21, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Calcagno, P.; Lester, D.; Girardi, P.; Amore, M.; Pompili, M. Suicide Risk in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Current Alzheimer Research 2016, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, M.A.T.; Santos, R.L.; Kimura, N.; Lacerda, I.B.; Dourado, M.C.N. Disease awareness may increase risk of suicide in young onset dementia. Dement Nerupsychol 2017, 11, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gvion, Y.; Levi-Belz, Y.; Hadlaczky, G.; Apter, A. On the role of impulsivity and decision-making in suicidal behavior. World J Psychiatry 2015, 5, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J.; Currie, D. Biological predictors of suicidal behaviour in mood disorders. In Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention, 1 ed ed.; Oxford Universty Press: Oxford, 2009; pp. 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Robbins, T.W. The role of prefontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudic, S.; D, B.G.; Thibaudet, M.C.; Smagghe, A.; Remy, P.; Traykov, L. Executive function deficits in early Alzheimer’s disease and their relations with episodic memory. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2006, 21, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahioui, H.; Blecha, L.; Bottai, T.; Depuy, C.; Jacquesy, L.; Kochman, F.; Meynard, J.A.; Papeta, D.; Rammouz, I.; Ghachem, R. La thérapie interpersonnelle de la recherche à la pratique [Interpersonal psychotherapy from research to practice]. Encephale 2015, 41, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siette, J.; Dodds, L.; Surian, D.; Prgomet, M.; Dunn, A.; Westbrook, J. Social interactions and quality of life of residents in aged care facilities: A multi-methods study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brivio, P.; Sbrini, G.; Tarantini, L.; Parravicini, C.; Gruca, P.; et al. Stress Modifies the Expression of Glucocorticoid-Responsive Genes by Acting at Epigenetic Levels in the Rat Prefrontal Cortex: Modulatory Activity of Lurasidone. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janthakhin, Y.; Kingtong, S.; Juntapremjit, S. Inhibition of glucocorticoid synthesis alleviates cognitive impairment in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

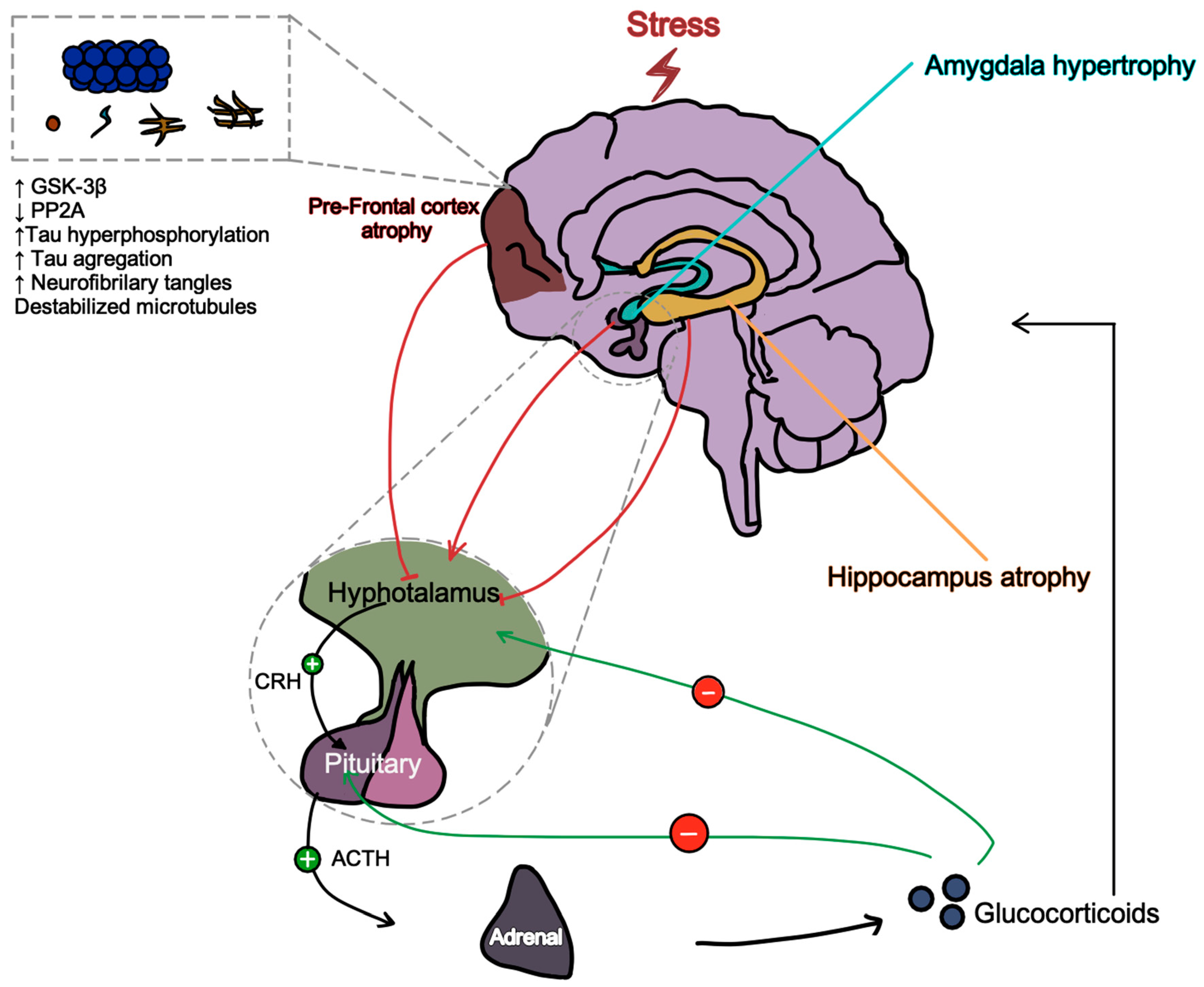

- Dioli, C.; Papadimitriou, G.; Megalokonomou, A.; Marques, C.; Sousa, N.; Sotiropoulos, I. Chronic Stress, Depreesion, and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Triangle of Oblivion. In GeNeDis, Vlamos, P., Ed. Springer: Switzerland, 2023; Vol. 1423, pp. 303-315.

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Lancet 2017, 387, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.F.R. O que é o suicídio: perfil epidemiológico de suicídio na cidade de Marília: proposições para prevenção; Dialética: São Paulo, 2022; Volume 1, p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’Connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiropoulos, I.; Silva, J.M.; Gomes, P.; Sousa, N.; Almeida, O.F.X. Stress and the Etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Depression. In Tau Biology, Takashima, A., et al., Eds. Springer: Singapore, 2019; Vol. 1184, pp. 241-257.

- Majd, S.; Koblar, S.; Power, J. Compound C enhances tau phosphorylation at Serine 396 via PI3K activation in an AMPK and rapamycin independent way in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett 2018, 670, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratuze, M.; Joly-Amado, A.; Buee, L.; Vieau, D.; Blum, D. Tau, Diabetes and Insulin. In Tau Biology, Takashima, A., Ed. Springer: Singapore, 2019; Vol. 1184, pp. 259-287.

- Saeedi, M.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Association between chronic stress and Alzheimer’s disease: Therapeutic effects of Saffron. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 133, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalin, N.H. Adverstity, Trauma, Suicide, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Psychiatry 2021, 178, 985–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portacolone, E.; Byers, A.L.; Halpern, J.; Barnes, D.E. Addressing Suicide Risk in Patients Living With Dementia During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. The Gerontologist 2022, 62, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orden, K.A.V.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol Rev 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyle, H. Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome. British Medical Journal 1950, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Z.A.; Schattner, P.; Mazza, D. Doing a pilot study: why is it essential? Malaysian Family Physician 2006, 1, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, G.A.; Dodd, S.; Williamson, P.R. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practise. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practise 2004, 10, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.C.; Davis, L.L.; Kraemer, H.C. The Role and Interpretation of Pilot Studies in Clinical Research. J Psychiatr Res 2011, 45, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, Y.; Jimba, M.; Yanai, H.; Fujii, S.; Inoguchi, T. Interpersonal Trust and Quality-of-Life: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. PLoS ONE 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.F.R.; Araújo Filho, G.M.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Rubatino, F.V.M.; Fischer, H.; Payão, S.L.M. Development and validation of a questionnarie to measure association factors with suicide: An instrument for a populational survey. Health Science Reports 2023, 62023;6:e, e1396. [Google Scholar]

- Guewehr, K. Teoria da resposta ao item na avaliação de qualidade de vida de idosos. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2007.

- In, J. Introduction of a pilot study. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 2017, 70, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney, L.G.; Watkins, M.P. Foundations of Clinical Research: applications to pratice, 3rd ed.; Hall, P.P., Ed. Pearson Prentice Hall: New Jersey (NJ), 2009; p. 892. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, J.C. A Research Approach to Improving Our Quality of Life. American Psychologist 1978, 33, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Anderson, K.L.; Archenholtz, B.; Hägg, O. The Flanagan Quality of Life Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, H.; Guedes, S.L.; Pereira, V.C. O ostomizado e a qualidade de vida: abordagem fundamentada nas dimensões da qualidade de vida: abordagem fundamentada nas dimensões da qualidade de vida proposta por Flanagan. Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1996.

- Galisteu, K.J.; Facundim, S.D.; Ribeiro, R.d.C.H.M.; Soler, Z.A.S.G. The Quality of Life of the Elderly in a senior friendly community: measurements with Flanagan’s scale. Arq Ciênc Saúde 2006, 13, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Cai, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. The role of peer social relationships in psychological distress and quality of life among adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmer, B.; Lee, S.; Duong, T.V.H.; Saadabadi, A. Suicidal Ideation. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024; p https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565877/.

- Browning, C.J.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, T.; Thomas, S.A. Food, Eating, and Happy Aging: The Perceptions of Older Chinese People. Front Public Health 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, P. Modeling the effects of physical activity, education, health, and subjective wealth on happiness based on Indonesian national survey data. BMC Public Health 2022, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Brasfield, M.B.; Bui, C.; Patihis, L.; Crowther, M.R.; Allen, R.S.; McDonough, I.M. Self-Reported Chronic Stress Is Unique Across Lifetime Periods: A Test of Competing Structural Equation Models. Gerontologist 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, S.A.; Helms, S.W.; Rudolph, K.D.; Hastings, P.D.; Nock, M.K.; Prinstein, M.J. Interpersonal Stress Severity Longitudinally Predicts Adolescent Girls’ Depressive Symptoms: the Moderating Role of Subjective and HPA Axis Stress Responses. J Abnorm Child Psycho 2019, 47, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R, S. Coping with stress: a physician’s guide to mental health in aging. Geriatrics 1996, 51, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stickley, A.; Shirama, A.; Sumiyoshi, T. Psychotic experiences, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from Japan. Schizophrenia Research 2023, 260, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SC, S. Pathology in Relationships. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2021, 17, 577–601. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Wan, G.; Cheng, S.; Wen, P.; Yan, X.; Li, J.; Tian, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Disruptions of Gut Microbiota are Associated with Cognitive Deficit or Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. Current Alzheimer Research 2023, 20, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.G.; Coleman, T.; Buciuc, M.; Singh, N.A.; Pham, N.T.T.; Machulda, M.M.; Graff-Radford, J.; Whitwell, J.L.; Josephs, K.A. Behavioral and neuropsychiatric differences across two atypical Alzheimer’s disease variants: Logopenic Aphasia and Posterior Cortical Atrophy. J Alzheimer Dis 2024, 97, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, A.; Mishra, T.K.; Saraf, S.; Tripathy, B.; Reddy, S.S. A Review on the Use of Modern Computational Methods in Alzheimer’s Disease-Detection and Prediction. Current Alzheimer Research 2023, 20, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermer, M.H.N. Preclinical Disease or Risk Factor? Alzheimer’s Disease as a Case Study of Changing Conceptualizations of Disease. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine 2023, 48, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, L.F.; Nunes, P.V.; Yassuda, M.S.; Aprahamian, I.; Santos, F.S.; Santos, G.D.; Brum, P.S.; Borges, S.M.; Oliveira, A.M.; Chaves, G.F.; et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary cognitive rehabilitation program for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011, 66, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.L.; McConnell, M.; Schuchardt, A.; Peffer, M.E. Challenges facing interdisciplinary researchers: Findings from a professional development workshop. PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Suicide mortality and reports of self-harm in Brazil. Saúde, S.d.V.e., Ed. Ministério da Saúde Brasilia (DF), 2021; Vol. 52.

- Rigitano, M.H.C.; Barbassa, A.P. Participation in Bauru master plans.

- Brazil. In Environnement Urbain / Urban Environment, 2010; Vol. 4.

- Kirby, T. Brazil facing ageing population challenges. Lancet 2023, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M. Dynamics of Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Communication in the Era of Multiculturalism and Cosmopolitism in Brazil. International Journal of Sociology 2024, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

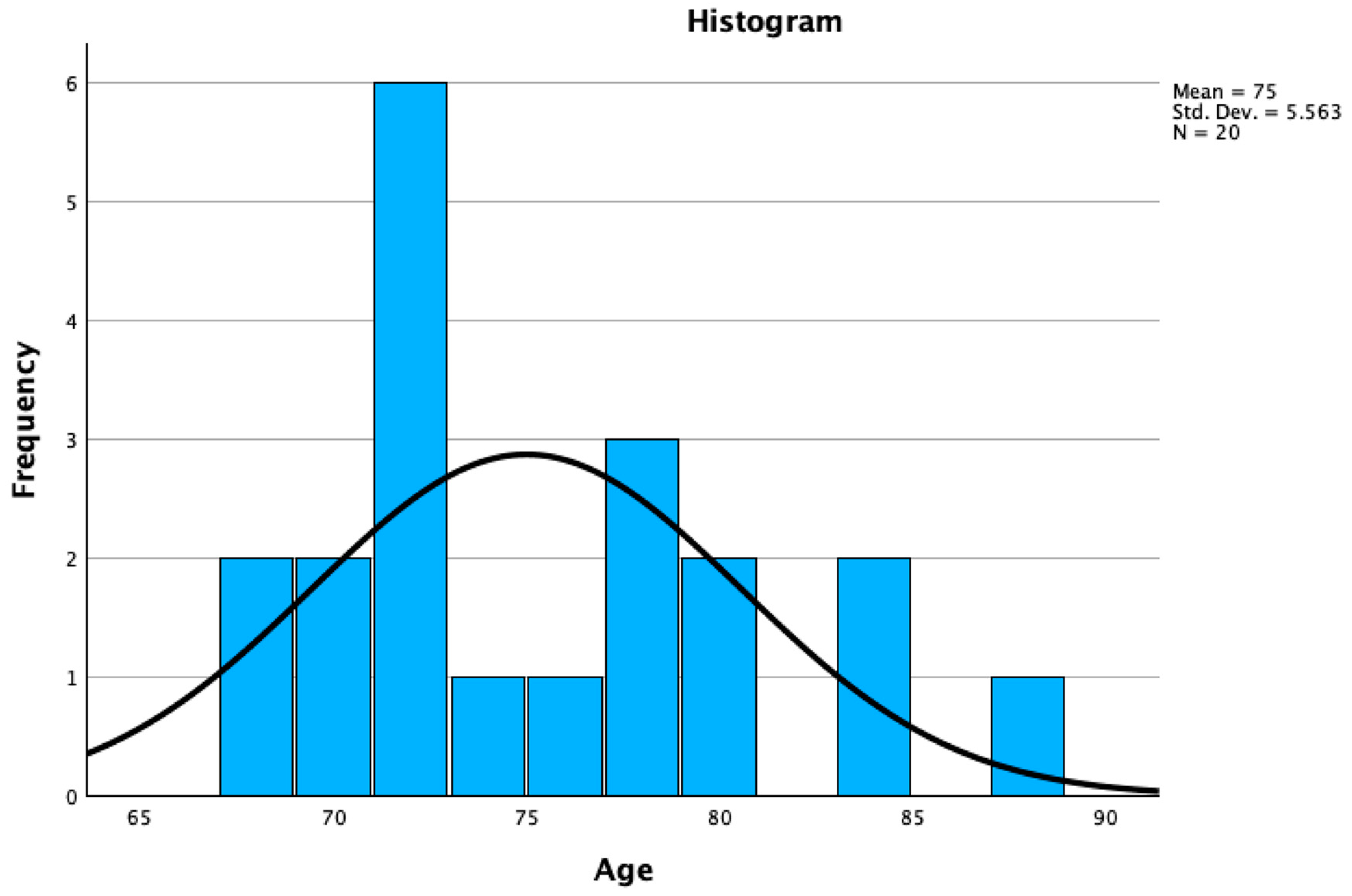

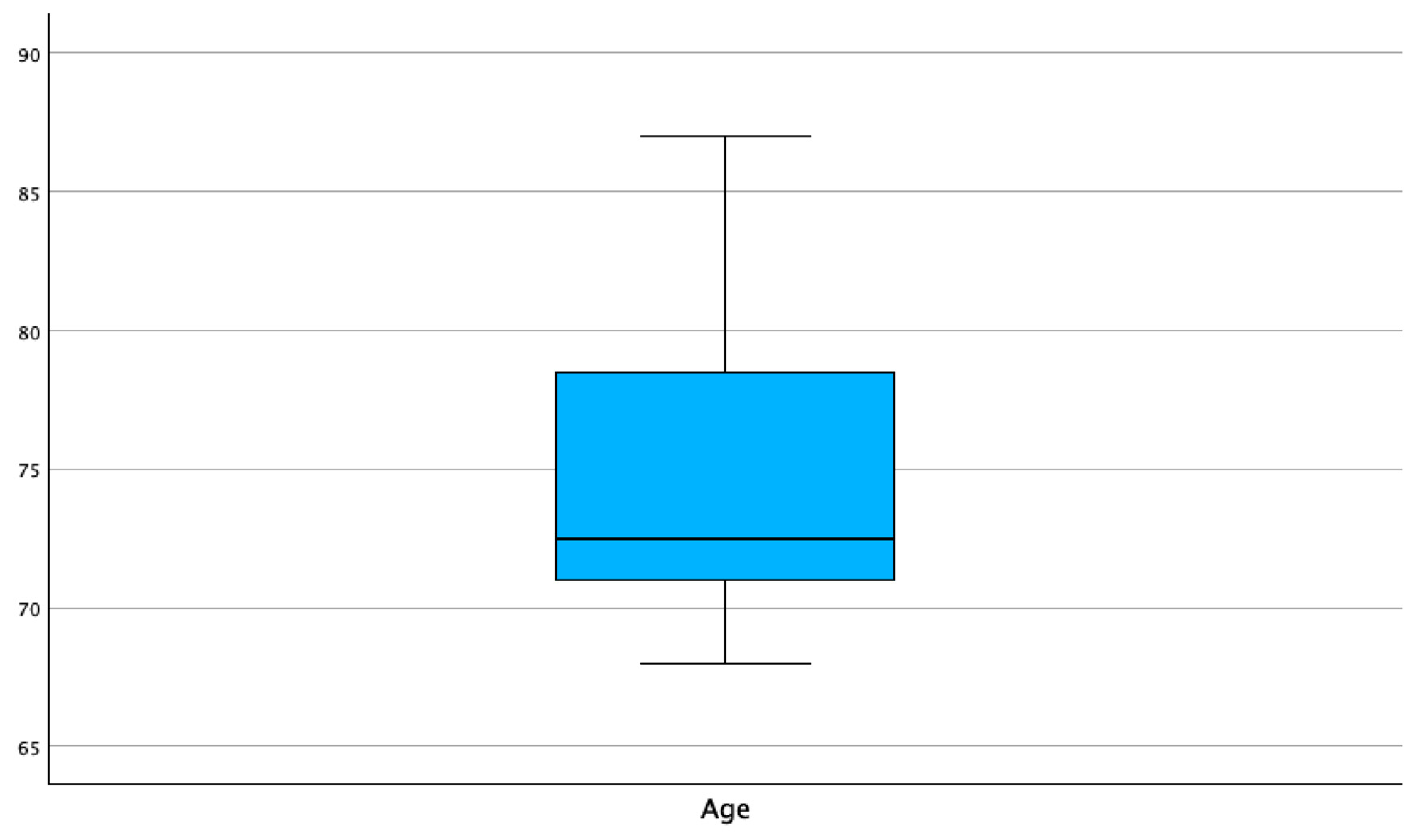

| Age in years | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| 68 | 2 | .3 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| 69 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| 70 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 20.0 |

| 71 | 2 | .3 | 10.0 | 30.0 |

| 72 | 4 | .6 | 20.0 | 50.0 |

| 73 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 55.0 |

| 75 | 1 | .3 | 5.0 | 60.0 |

| 78 | 3 | .5 | 15.0 | 75.0 |

| 79 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 80.0 |

| 80 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 85.0 |

| 83 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 90.0 |

| 84 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 95.0 |

| 87 | 1 | .2 | 5.0 | 100.0 |

| Total | 20 | 3.2 | 100.0 |

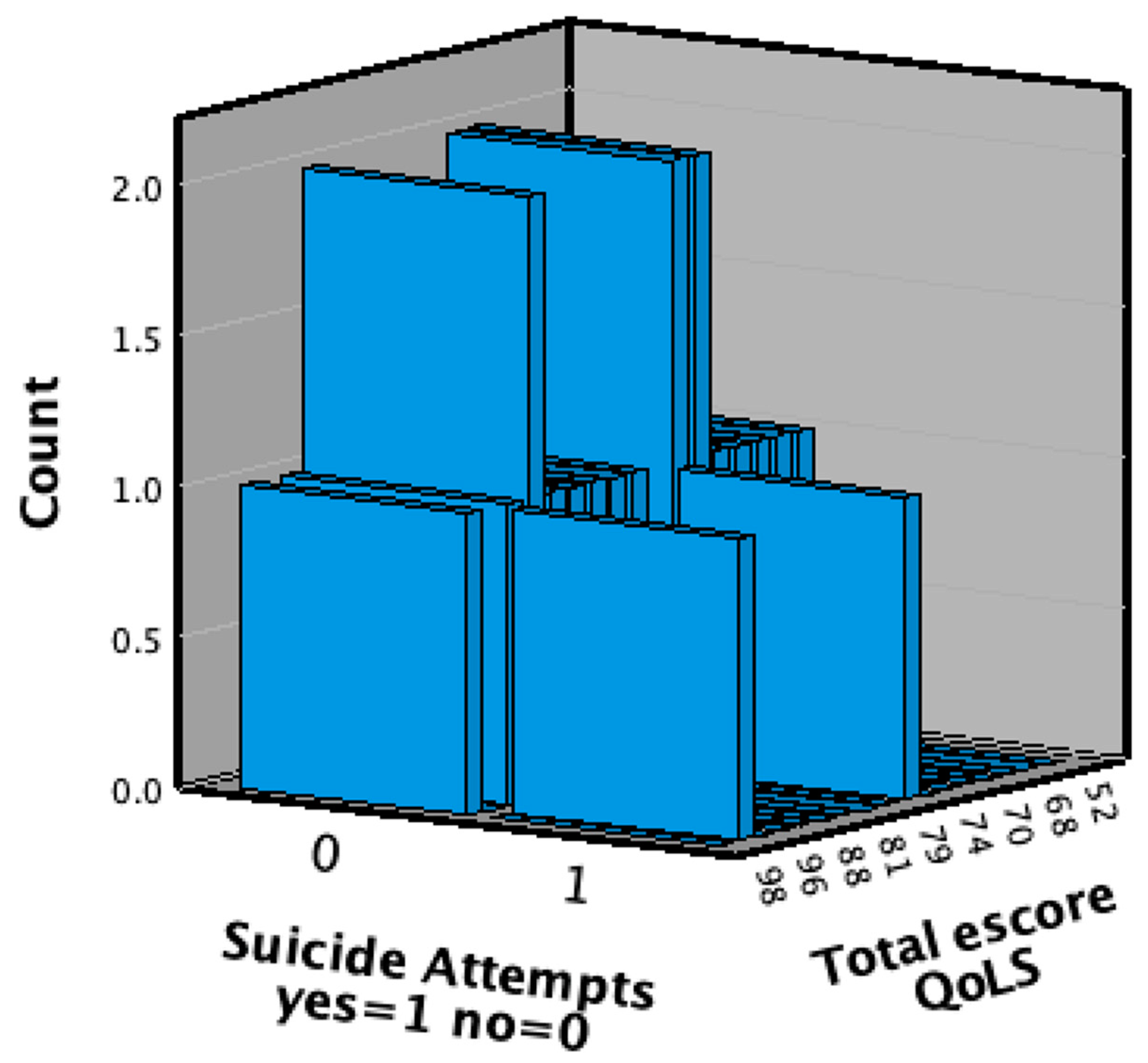

| Suicide attempts yes=1 no=0 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 0 | 18 | 2.9 | 90.0 | 90.0 |

| 1 | 2 | .3 | 10.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 20 | 3.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Variable | N | Mode | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Percentil 25 |

Percentil 75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 7 | 6.50 | 1 | 7 | 6.00 | 7.00 |

| 2 | 20 | 6 | 5.50 | 1 | 7 | 4.25 | 6.00 |

| 3 | 20 | 7 | 6.00 | 3 | 7 | 5.25 | 7.00 |

| 4 | 20 | 7 | 7.00 | 2 | 7 | 6.00 | 7.00 |

| 5 | 20 | 4 | 5.00 | 2 | 7 | 4.00 | 6.75 |

| 6 | 20 | 6 | 6.00 | 2 | 7 | 5.25 | 7.00 |

| 7 | 20 | 6 | 6.00 | 2 | 7 | 4.00 | 6.75 |

| 8 | 20 | 6 | 5.50 | 3 | 6 | 4.00 | 6.00 |

| 9 | 20 | 4 | 4.00 | 2 | 7 | 4.00 | 6.00 |

| 10 | 20 | 4 | 4.50 | 2 | 7 | 4.00 | 6.00 |

| 11 | 20 | 6 | 6.00 | 2 | 7 | 4.00 | 6.75 |

| 12 | 20 | 4 | 4.00 | 2 | 7 | 3.25 | 6.00 |

| 13 | 20 | 6 | 4.00 | 1 | 6 | 3.25 | 6.00 |

| 14 | 20 | 6 | 6.00 | 4 | 7 | 5.25 | 7.00 |

| 15 | 20 | 6 | 6.00 | 2 | 7 | 3.25 | 6.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).