1. Introduction

Saudi Arabia faces unprecedented urbanization pressures, with 85% of its population residing in cities, contributing to 70% of the nation’s carbon emissions [

1]. This urban expansion presents significant environmental and infrastructural challenges, including high energy consumption, carbon emissions, and resource depletion [

2]. In response, the Saudi government has placed sustainable urban development at the core of Vision 2030, aiming to transform its cities into global hubs of economic, social, and environmental sustainability [

3]. The government has embarked on several national initiatives and strategies for sustainable urban development, such as the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI), which aims to reduce carbon emissions by 278 million tons annually and plant 10 billion trees [

4]; the National Renewable Energy Program (NREP), targeting 50% of renewable energy in the power mix by 2030 [

5]; and the initiatives for smart and sustainable cities, focusing on carbon neutrality, smart mobility, and energy-efficient urban systems [

6]. Despite these ambitious plans, financing remains a major challenge for large-scale green urban projects. Traditional funding sources, such as government budgets and private investments, are often insufficient to meet sustainability targets. Additionally, local governments heavily depend on allocations from the central government, which has, in turn, created pressure on the central government’s financial system. Within the last ten years, the central government’s funds to municipalities exceeded SAR 35 billion (about USD 9.28 billion), while municipal-owned revenues nearly exceeded SAR 7 billion (about USD 1.89 billion) [

7,

8]. This continued reliance on the government budget has resulted in an obligation from the central government for Saudi municipalities to generate about 40% of their own revenues over the next five years [

3]. Hence, green municipal bonds could serve as a crucial financing instrument to bridge these financial gaps.

Green financing mechanisms, particularly green municipal bonds (GMBs), have emerged as a key tool for funding sustainable infrastructure projects globally [

9]. These bonds enable local governments to raise capital for environmentally friendly projects such as renewable energy, public transport, green buildings, and climate resilience initiatives [

10]. GMBs are debt securities issued by local governments to finance projects with positive environmental benefits [

11]. They have gained traction worldwide, with major cities such as New York, Paris, and Singapore successfully using them to fund climate-resilient infrastructure [

12].

Given Saudi Arabia’s commitment to sustainable urbanism through several national initiatives such as NEOM, The Line, and Riyadh Green, integrating GMBs into the country’s financial system could accelerate the transition toward green cities while attracting domestic and foreign investment. The adoption of GMBs could mobilize climate finance, support infrastructure resilience, and diversify funding sources for sustainable urbanization. However, several barriers such as regulatory constraints, investor confidence, and market readiness must be addressed to establish a robust green bond ecosystem. This paper explores the feasibility of green municipal bonds in advancing Saudi Arabia’s urban sustainability agenda. Specifically, it aims to assess the potential benefits and challenges of GMBs in the Saudi context; examine global best practices and their applicability to Saudi municipalities; and develop a conceptual framework integrating financial, environmental, and governance dimensions for GMBs in sustainable urbanism.

2. Global Literature Review: Concepts and Practices

Green municipal bonds (GMBs) are debt instruments issued by local or regional governments to finance environmentally sustainable projects [

9]. These projects typically include renewable energy, clean transportation, water conservation, energy-efficient buildings, and climate resilience initiatives [

10,

13,

14]. Unlike traditional municipal bonds, GMBs require issuers to report on the environmental impact of funded projects, ensuring transparency and alignment with sustainability objectives [

15]. The four key features of GMBs include (1) the use of proceeds, (2) certification and standards, (3) transparency and reporting, and (4) investor appeal. These key features are critical for any GMBs to be successful [

15,

16].

Table 1 presents these GMB features with some illustrated examples.

As of 2023, the global green bond market exceeded USD 2 trillion in cumulative issuances, with municipal bonds playing an increasing role in financing climate-friendly urban infrastructure [

17,

18]. Many cities and local governments worldwide have successfully used GMBs to fund sustainable urban projects. The city of Gothenburg, Sweden, for example, stands out as a pioneering city in the issuance of GMBs, setting a benchmark for sustainable urban financing worldwide. In 2013, Gothenburg became the world’s first city to issue a municipal green bond, aiming to transition to an environmentally sustainable city by 2030 [

19]. As of December 2023, the city had raised a total of USD 2.32 billion through green bonds, funding various eco-friendly projects such as renewable energy, green public transport, energy-efficient housing, and water management systems [

20]. Gothenburg’s innovative approach has not only advanced its sustainability goals but also inspired other municipalities worldwide to explore green bonds as a viable financing mechanism for environmental projects [

19,

20].

New York city is another successful global model for using green bonds to simultaneously tackle climate change, fiscal responsibility, and social equity in large cities. The city issued its first municipal green bond in October 2021, raising USD 1.25 billion to fund climate-focused infrastructure projects aligned with its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 [

21]. The bond adheres to global standards such as the Green Bond Principles (GBP) and Climate Bonds Standard (CBS), ensuring funds are allocated to projects such as clean water upgrades, climate resilience, energy efficiency retrofits, and sustainable transport. To ensure accountability, NYC publishes annual transparency reports detailing fund allocation and environmental impacts, such as reduced energy use (30% in retrofitted buildings) and CO₂ savings. The bond’s strong ESG appeal attracted overwhelming demand, with orders totaling USD 5 billion (5x oversubscribed), enabling the city to secure lower borrowing costs and save taxpayer funds. A portion of proceeds directly target low-income communities, funding projects such as flood protection in vulnerable areas to address equity gaps. Building on this success, NYC launched a second green bond in 2022 (USD 1.1 billion) to expand initiatives such as offshore wind energy readiness [

22]. By legally linking MGB proceeds to climate targets, NYC has become a global model for using green bonds to simultaneously tackle climate change, fiscal responsibility, and social equity in large cities.

As for emerging markets, Cape Town’s Green Bond Initiative showed how cities can leverage green bonds for urgent climate action [

23]. Cape Town became the first African city to issue a green bond, raising ZAR 1 billion (~USD 67 million) to fund urgent climate adoption projects. The bond, certified by the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), allocated 40% of its proceeds to water security, including desalination plants, groundwater extraction, and pipe leak repairs, which helped reduce water demand by 50% and avert the crisis. Another 40% funded renewable energy, such as solar installations on public buildings and LED streetlight retrofits, while 20% supported sustainable transport, including electric vehicle charging stations and bike lanes [

24,

25]. Annual impact reports revealed 6.5 billion liters of water saved annually and 3.2 GWh of solar energy generated, with projects prioritizing marginalized communities (e.g., solar-powered clinics in low-income areas). Despite challenges such as balancing speed and long-term planning, the bond attracted local and international ESG investors and inspired other African cities to adopt green finance. Cape Town’s success rooted in crisis-driven innovation showcased how cities can leverage green bonds for urgent climate action, leading to plans for a second bond in 2023 to expand renewable energy and affordable housing, solidifying its role as a pioneer in sustainable urban resilience [

26].

These three examples and several other worldwide successful examples demonstrate how cities, in both developed and emerging markets, leverage GMBs to decarbonize urban infrastructure, attract sustainable investments, and enhance climate resilience [

15]. A comparison of key benefits and obstacles associated with the adoption of MGBs can be summarized in

Table 2.

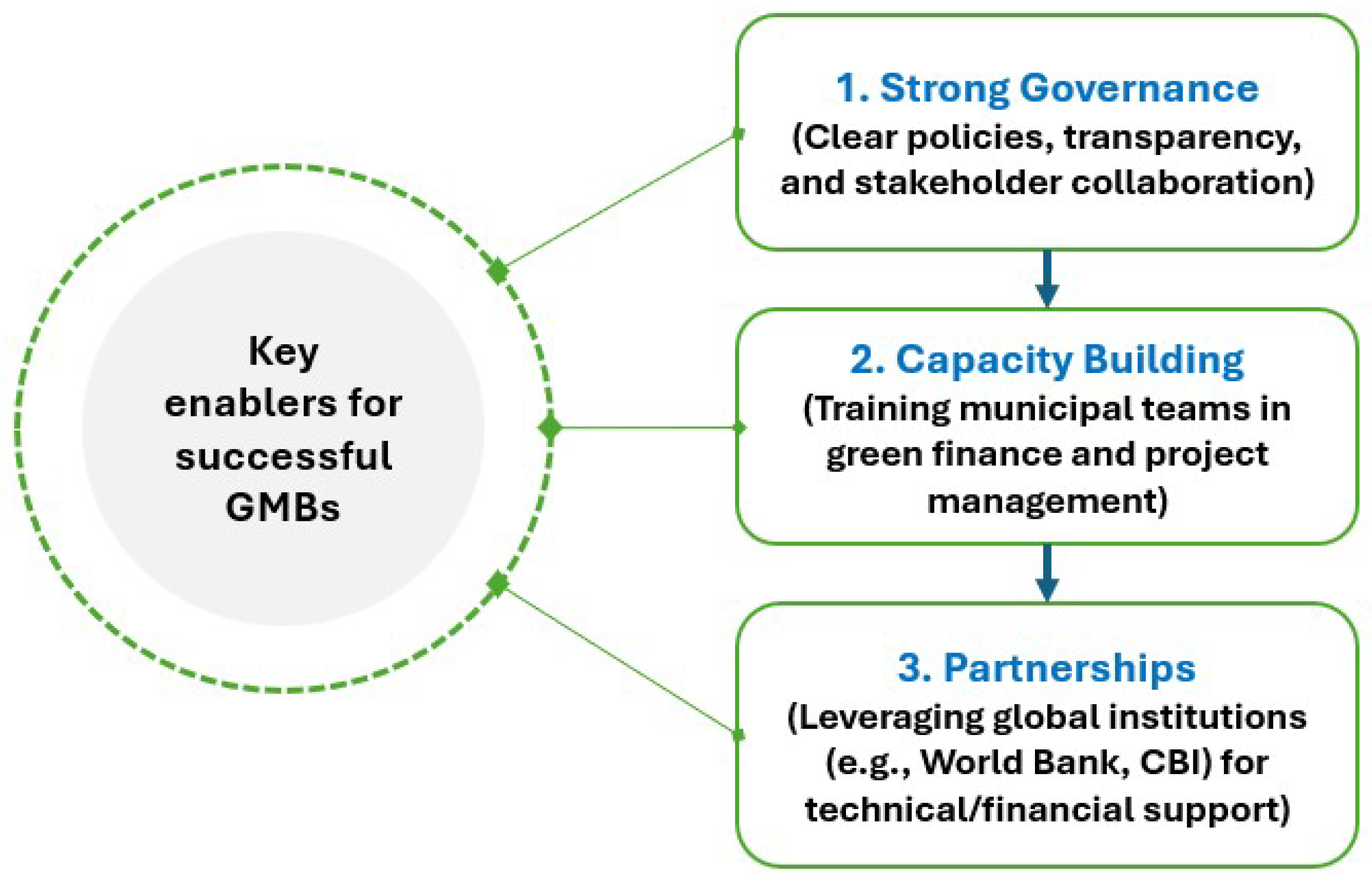

While GMBs offer transformative potential for sustainable urban development, their success depends on three interrelated pillars, as shown in

Figure 1.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative research approach based on a literature review, government policy documents, and global case studies to develop a conceptual framework for Green Municipal Bonds (GMBs) in Saudi Arabia. The methodology focused on analyzing existing knowledge, regulatory frameworks, and best international practices to assess the feasibility and implementation strategies for GMBs in the Kingdom. The qualitative method allowed for an in-depth examination of factors such as regulatory readiness, policy coherence, financial mechanisms, and sustainability integration, which are critical for feasibility assessment and strategic planning [

28]. Given that GMBs are a relatively new concept in the Kingdom, this study required an exploratory and interpretive approach rather than a numerical or statistical one [

29]. While quantitative research methods could be valuable for assessing the financial performance or impact of GMBs at a later stage, they are not suitable for this foundational phase of the research [

30]. Additionally, the qualitative approach enables the integration of stakeholder perspectives, policy implications, and comparative insights from different jurisdictions, which are essential for crafting an adaptable and practical framework for Saudi Arabia. By analyzing case studies from other cities and countries, this study can extract key lessons and best practices to ensure that GMBs in Saudi Arabia are designed to align with both domestic sustainability goals and international green finance standards [

31].

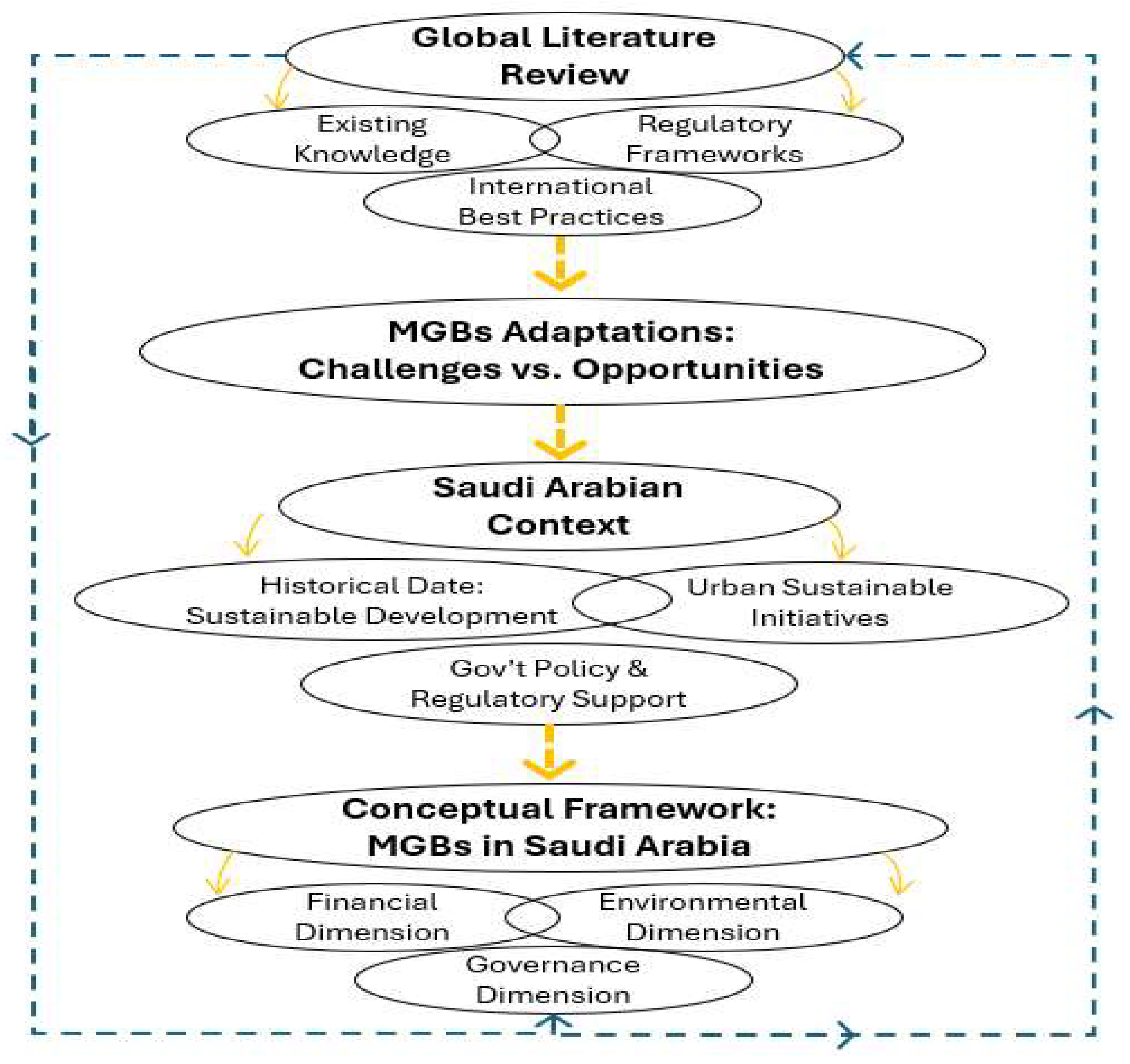

The data employed for this study were gathered from multiple academic databases and public sector portals, guaranteeing their precision and pertinence to the subject matter. These resources supplied detailed and reputable datasets, facilitating a thorough examination of the complexities and prospects linked to urban development and MGB adjustments within the Saudi context. By drawing upon trusted sources, this study establishes a solid evidentiary basis for its conclusions and proposals, which are in harmony with the objectives of Vision 2030 that aim to foster the progression of eco-friendly city planning practices. The methodology followed to achieve the objectives is shown in

Figure 2.

Building on the research insights, a customized strategy for adopting MGBs in Saudi Arabia was formulated, incorporating fiscal, ecological, and regulatory considerations to enhance the role of GMBs in sustainable city development. This analytical model not only underscores the capacity of MGBs to mitigate urban issues but also delivers an actionable roadmap for decision-makers, city planners, and involved parties. It promotes the creation of intelligent and equitable urban systems and diversified revenue streams for eco-conscious urbanization, coordinated with the nation’s comprehensive sustainability goals under Vision 2030.

4. Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabia: Principles, Initiatives, and Policies

Sustainable urbanism integrates environmental, social, and economic strategies to create resilient and livable cities. In Saudi Arabia, this approach aligns with the nation’s Vision 2030, aiming to diversify the economy and reduce dependence on oil [

3]. This section explores the key principles of sustainable urbanism, examines major urban sustainability initiatives in Saudi Arabia, and discusses the policy and regulatory frameworks supporting green urban development.

Sustainable urbanism encompasses several core principles designed to foster environmentally friendly and efficient urban spaces [

32,

33]. Clean energy transition is one of the key fundamental principles to sustainable urbanism. Transitioning from fossil fuels to renewables is central to the Saudi sustainability goals [

4]. Utilizing solar, wind, and hydroelectric power reduces reliance on fossil fuels and decreases greenhouse gas emissions [

34]. The National Renewable Energy Program (NREP) aims to achieve 50% of renewable energy by 2030, with solar projects such as the Sakaka PV Plant and Sudair Solar Park leading the charge [

35]. NEOM’s hydrogen plant further underscores ambitions to become a global green energy exporter [

36]. To encourage the transition to renewable energy, the government offers incentives such as subsidies and tax benefits for individuals and businesses investing in renewable energy solutions. These incentives are designed to make renewable energy more accessible and affordable, accelerating the country’s shift toward a sustainable energy landscape.

Smart cities are another key principle to sustainable urbanism in the country. Smart cities leverage technology to optimize resource efficiency, infrastructure, and citizen engagement, exemplified in Saudi Arabia through the integration of IoT sensors, data analytics, and AI into urban planning to reduce energy and water consumption and enhance governance. For instance, NEOM’s AI-driven utilities and autonomous transportation systems aim to create a hyper-connected, zero-carbon city [

36], while smart infrastructure—such as sensor-monitored water and energy networks—optimizes resource use, minimizes waste, and improves service delivery for residents. Complementing this, Saudi Arabia prioritizes sustainable mobility through projects such as Riyadh’s (USD 22.5 billion) metro and The Line’s car-free, walkable design [

37], reducing emissions and congestion. Additionally, innovative water solutions, including renewable-powered desalination and wastewater recycling, align with the National Water Strategy 2030, targeting a 43% reduction in per capita consumption and 95% reuse of treated wastewater [

5]. Together, these technologies form a holistic framework for resilient, efficient, and livable urban ecosystems.

Green building practices along with urban green spaces are another core principle of sustainable urbanism. Saudi Arabia’s sustainability efforts merge innovative green building practices and expansive urban greening initiatives to combat environmental challenges and align with the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) and Vision 2030. The Kingdom prioritizes energy-efficient, climate-responsive architecture through high-performance building envelopes, solar-optimized shading, and smart systems that reduce reliance on cooling in its harsh arid climate. Projects such as Riyadh’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), certified by King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), exemplify this approach with solar panels, graywater recycling, and energy-efficient lighting, while locally sourced, low-carbon materials align with the Saudi Building Code’s energy mandates [

38,

39]. Water scarcity is addressed via smart irrigation, wastewater reuse, and drought-resistant landscaping, complemented by urban greening strategies such as green roofs, vertical gardens, and shaded courtyards to mitigate heat islands. Large-scale programs such as Riyadh Green (a USD 23 billion project), aiming to plant 7.5 million trees and develop 3300 parks by 2030 [

37], and transformative projects such as King Salman Park and Jeddah’s Corniche integrate native species, smart water management, and recreational spaces to enhance biodiversity, air quality, and livability. These efforts are amplified by the SGI’s goals to cut carbon emissions by 30%, protect 30% of natural areas by 2030 [

4,

40], and promote circular economy principles. By blending traditional design elements, such as wind towers, with AI-driven resource management and technologies, Saudi Arabia is fostering resilient, resource-efficient cities where green infrastructure supports ecological balance, climate adaptation, and community well-being in arid environments.

Finally, Saudi Arabia’s approach to sustainable urbanism, guided by Vision 2030, integrates key principles such as renewable energy integration, smart cities, green building practices, and the development of urban green spaces. Through ambitious initiatives such as NEOM, The Line, and the Green Riyadh Project, supported by a comprehensive policy and regulatory framework, the nation is making significant strides toward creating sustainable and livable urban environments. These efforts not only aim to enhance the quality of life for residents but also position Saudi Arabia as a leader in sustainable urban development on the global stage.

5. Discussion: GMB Adoption in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 underscores the need for innovative financing mechanisms to support its ambitious urban sustainability projects. Municipal green bonds, which are debt instruments issued by local governments to fund environmentally friendly infrastructure, offer a promising avenue for accelerating green urban development. These bonds could help finance large-scale projects such as NEOM, The Line, and Riyadh Green by attracting global ESG investors. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s commitment to sustainability through Vision 2030 and initiatives such as the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) strengthens the credibility of green bonds, ensuring alignment with international standards such as the Green Bond Principles and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Additionally, leveraging public–private partnerships (PPPs) and building on the success of the country’s first sovereign green bond issuance in 2022 could further support the adoption of municipal green bonds [

41,

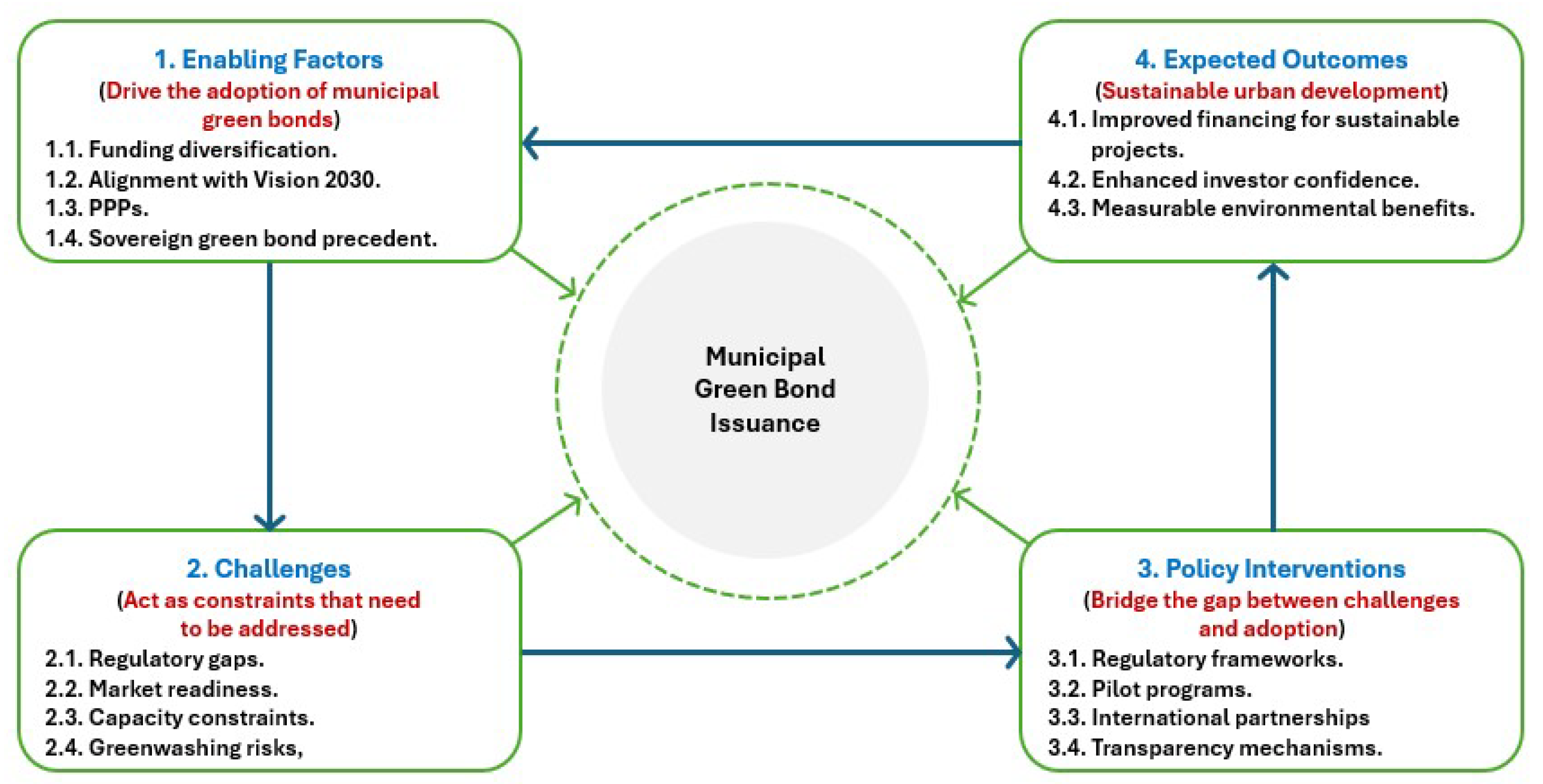

42]. Despite the potential benefits, several challenges must be addressed to facilitate municipal green bond adoption in Saudi Arabia. Regulatory and institutional gaps pose significant hurdles, including the lack of standardized criteria for defining “green” projects, weak reporting mechanisms, and limited experience in assessing municipal creditworthiness. Market readiness is another challenge, as domestic investors may be less familiar with ESG frameworks and the country’s bond market remains relatively shallow. Additionally, municipalities often lack the technical expertise needed to structure and market green bonds effectively. Concerns over greenwashing—where bond proceeds may be misallocated to projects with minimal environmental benefits—also highlight the need for rigorous certification and transparency to ensure credibility and investor confidence.

To overcome these challenges, Saudi Arabia should establish a comprehensive national green bond framework through collaboration between the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the Capital Market Authority (CMA). This framework should include clear guidelines on eligible projects, third-party verification requirements, and potential tax incentives for green bond investors. Piloting municipal issuers in key cities such as Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam for targeted projects—such as metro expansion or solar-powered schools—would help build market confidence. Furthermore, international partnerships with institutions such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and HSBC’s Green Bond Initiative could provide technical assistance and attract foreign investment. Lastly, enhancing transparency through public dashboards that track bond proceeds and project outcomes would strengthen accountability and long-term success.

As a result, a conceptual framework for the adoption of MGBs in Saudi Arabia has been developed. The proposed conceptual framework is structured around four key elements that influence the adoption of municipal green bonds in Saudi Arabia: enablers, challenges, interventions, and expected outcomes (as illustrated in

Figure 3). These elements are informed by a comprehensive literature review, global best practices, and relevant government initiatives and policy documents.

6. Conclusions

The introduction of green municipal bonds (GMBs) in Saudi Arabia represents a transformative opportunity to finance sustainable urban development while aligning with Vision 2030, the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI), and global ESG investment trends. By mobilizing long-term capital, GMBs can support critical projects such as renewable energy, green transportation, and climate resilience initiatives. The integration of these bonds within Saudi Arabia’s financial ecosystem, particularly through Shariah-compliant Green Sukuk, can further enhance the country’s position as a global leader in Islamic sustainable finance. However, realizing the full potential of GMBs requires a well-defined regulatory framework, adherence to international standards, and strategic policies that encourage investor participation and financial market development.

To successfully implement GMBs, Saudi Arabia must address key challenges, including regulatory and institutional gaps, high issuance costs, liquidity constraints, and limited investor awareness. Establishing a dedicated green bond framework in alignment with the ICMA Green Bond Principles and Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) standards will be critical in ensuring credibility and investor confidence. Additionally, integrating financial incentives such as tax benefits and risk guarantees, alongside leveraging digital innovations such as blockchain for impact tracking, can enhance transparency and efficiency in the green bond market. The strategic use of public–private partnerships (PPPs) and cross-border collaborations with GCC, European, and Asian green finance markets can also accelerate adoption and scalability.

By implementing regulatory reforms, financial incentives, and institutional capacity-building measures, Saudi Arabia can establish a robust GMB market that supports both sustainable urban development and economic diversification. This financing mechanism has the potential to accelerate the country’s transition to low-carbon cities, enhance municipal financial autonomy, and attract global ESG investments. Furthermore, projects such as NEOM, the Red Sea Development, and Riyadh’s metro expansion could serve as global case studies, demonstrating the role of green bonds in climate-resilient urban transformation. With the right policies, investor transparency, and adherence to global best practices, Saudi Arabia is well positioned to become a regional and international leader in green finance, setting a precedent for other nations in the Middle East and beyond.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs and Housing (MOMRA). National Urban Development Strategy; Saudi Government Publication; 2022.

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Mughal, M.A. Urban Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020018. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Vision 2030. National Transformation Program: Sustainable Development Goals; Official Vision 2030 Document; 2021.

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). Annual Sustainability Report; Saudi Government Publication; 2023.

- Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (MEWA). National Renewable Energy Program Overview; Saudi Government Publication; 2022.

- Fakhruddin, B.; et al. Smart and Sustainable Cities in Saudi Arabia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104558. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Finance (MOF). Annual Budget Statements (2013–2023); Saudi Government Publication; 2023.

- Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs and Housing (MOMRA). Municipal Finance Reports (2023); Saudi Government Publication; 2023.

- Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). Global Green Bond Standards; CBI Official Report; 2023.

- OECD. Financing Climate-Resilient Cities: The Role of Green Bonds; OECD Urban Policy Review; 2022.

- World Bank. Green Bonds for Sustainable Cities; World Bank Climate Finance Report; 2023.

- Climate Bonds Initiative. The Role of Green Bonds in Financing Climate Resilient Cities; CBI Annual Report; 2022.

- OECD. Green Finance and Investment: Mobilizing Capital for Climate-Resilient Infrastructure; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Financing Sustainable Cities; OECD Urban Policy Review; 2022.

- ICMA. Green Bond Principles; International Capital Market Association Report; 2023.

- BlackRock. Sustainable Investing: Reshaping the Financial Landscape; BlackRock Global Report; 2021.

- World Bank. Green Bond Market Trends and Innovations; World Bank Sustainable Finance Report; 2023.

- UN-Habitat. Green Finance for Sustainable Urbanization; United Nations Report; 2022.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Gothenburg Green Bonds—Financing for Climate-Friendly Investment. Available online: https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/financing-for-climate-friendly/gothenburg-green-bonds (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- City of Gothenburg. Green Bonds in Gothenburg. Available online: https://goteborg.se/wps/portal?uri=gbglnk%3A2019923102711631 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- New York City Office of the Mayor. Recovery for All of Us: Mayor de Blasio, Comptroller Stringer, and Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Announce Successful Green Bond Issuance. 2021. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/694-21/recovery-all-us-mayor-de-blasio-comptroller-stringer-hudson-yards (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Office of the New York City Comptroller. The City of New York Announces Successful Sale of $1.1 Billion of General Obligation Bonds. 2024. Available online: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/nyc-bonds/the-city-of-new-york-announces-successful-sale-of-1-1-billion-of-general-obligation-bonds-2 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- City of Cape Town. City of Cape Town Green Bond Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Cape%20Town%20Green%20Bond%20Framework.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- REGlobal. Green Bond Market in South Africa. 2022. Available online: https://reglobal.org/green-bond-market-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Blue Horizon Energy. The Emergence of Municipal Green Bonds in South Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.bluehorizon.energy/financing-climate-change-adaptation-the-emergence-of-municipal-green-bonds-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Afripoli. Easing Africa’s Climate Crisis: Can Green Bonds Help Close the Climate Finance Gap? 2024. Available online: https://afripoli.org/easing-africas-climate-crisis-can-green-bonds-help-close-the-climate-finance-gap (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Green Bonds in Latin America; IDB Financial Insights Report; IDB: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson Institute. Sustainable Urban Planning Principles. 2017. Available online: https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sustainable-Urban-Planning_EN_vF.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Lehmann, S. The Principles of Green Urbanism: Transforming the City for Sustainability; Earthscan Publications: Oxford, MS, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Columbia | SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy. Saudi Arabia’s Renewable Energy Initiatives and Their Geopolitical Implications. 2023. Available online: https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/saudi-arabias-renewable-energy-initiatives-and-their-geopolitical-implications/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ministry of Energy, Industry, and Mineral Resources (MEIM). Saudi Arabia’s National Renewable Energy Program: Achieving 50% Renewable Energy by 2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.mei.gov.sa/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- NEOM. NEOM Sustainability Framework; NEOM Official Report; 2023.

- Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (RCRC). Annual Report: Climate Change and Humanitarian Action. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/annual-report-2020 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Saudi Building Code. Green Building Regulations; Government of Saudi Arabia: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). Green Building Trends: USGBC Annual Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/resources/usgbc-annual-report-2021 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). Saudi Green Initiative: Roadmap for Sustainability and Climate Action. 2021. Available online: https://www.sgi.gov.sa/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Public Investment Fund (PIF). Saudi Arabia’s Inaugural Sovereign Green Bond Issuance: $3 Billion for Sustainable Projects. 2022. Available online: https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/news-and-insights/press-releases/2022/usd-3-billion-inaugural-bond (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Public Investment Fund (PIF). PIF Green Bond Impact Assessment 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.pif.gov.sa/-/media/project/pif-corporate/pif-corporate-site/our-financials/capital-markets-program/pdf/pif-green-bond-impact-assessment-2024.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).